1. Introduction

Language teaching is regarded as a highly emotional work due to teachers’ constant emotional experiences and regulation during teaching (Ghanizadeh and Royaei [

1]). Previous studies exert much attention to teachers’ negative emotions, such as anxiety (Tüfekçi-Can [

2]) and burnout (Engin and Treleaven [

3]). Recently, some research has indicated that teachers’ positive psychology plays an important role in prompting teachers’ professional development and students’ performance and emotions (Frenzel, Daniels and Burić [

4]). Based on the Broaden and Build Theory of Positive Emotions (Fredrickson [

5]), teachers’ positive emotions can promote mental resilience, enhancing openness and acceptance of stress. Flow, as a key concept of positive psychology, has been found when teachers guide students to engage in the teaching process (Csikszentmihalyi [

6]). Moreover, flow is seen as a crucial individual resource to support teachers solving the instructional challenges (Dai and Wang [

7]).

Previous research has identified the antecedents and feelings of in-service EFL teachers’ flow (Csikszentmihalyi [

8]; Sobhanmanesh [

9]). Moreover, some findings indicated that flow has a positive influence on teachers’ professional growth (Tardy and Snyder [

10]). Recently, Barthelmäs and Keller [

11] proposed the three-dimensional flow theory, involving the antecedents, experiential features, and consequences of flow. Some scholars highlighted the fragility of flow among in-service EFL teachers (Nakamura, Tse and Shankland [

12]; Khajavi and Abdolrezapour [

13]; Dewaele and MacIntyre [

14]). However, there was no exploration on the re-engagement of EFL teachers’ flow after disruptions, which is a key aspect of flow dynamics (Nakamura, Tse and Shankland [

12]). Moreover, existing research targeted in-service EFL teachers, overlooking pre-service teachers who are at the crucial stage of career development (Bal-Gezegin, Balikçi and Gümüsok [

15]).

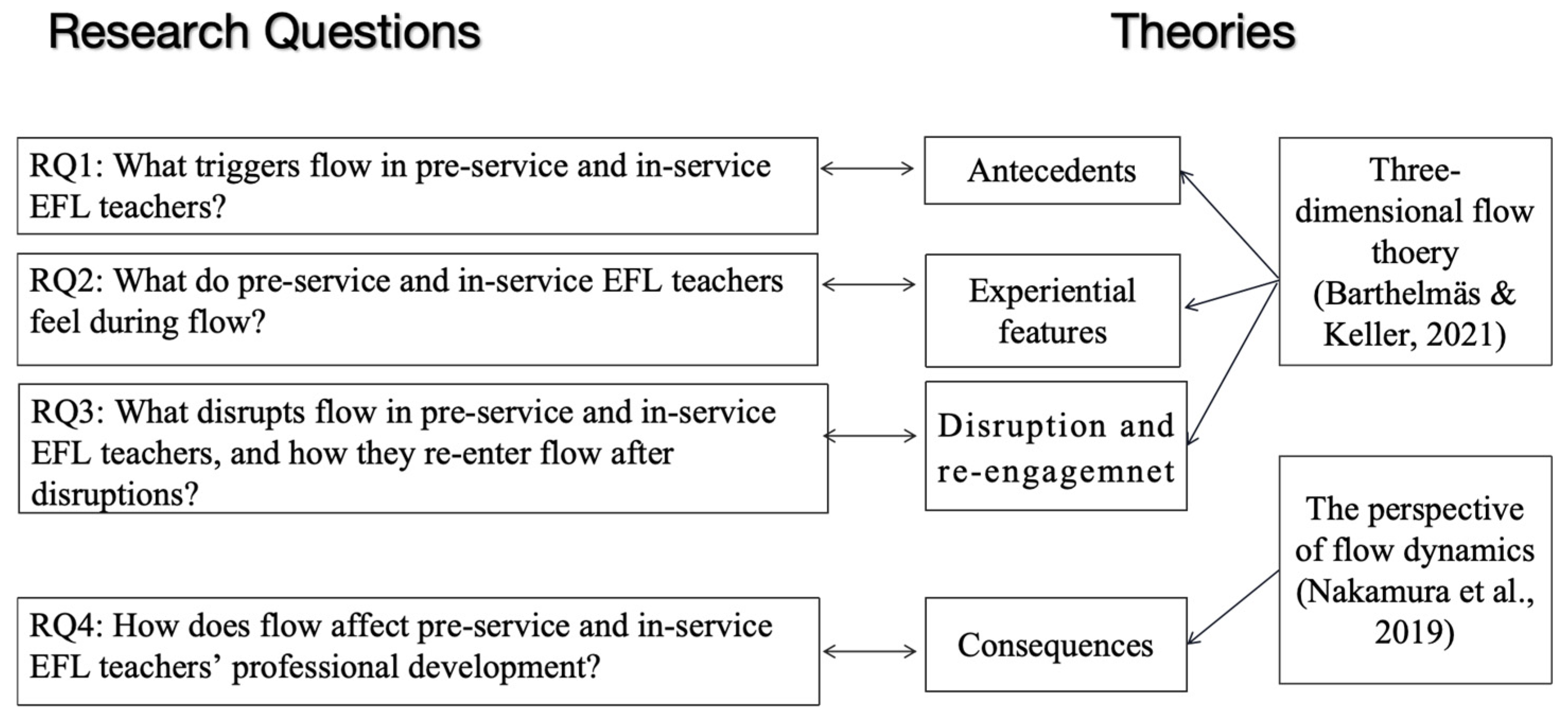

To fill these gaps, this research adopted a thematic narrative approach to explore the flow dynamics in pre-service and in-service EFL teachers during teaching. The research questions are: (1) What triggers flow in pre-service and in-service EFL teachers? (2) What do pre-service and in-service EFL teachers feel during flow? (3) What disrupts flow in pre-service and in-service EFL teachers, and how they re-enter flow after disruptions? (4) How does flow affect pre-service and in-service EFL teachers’ professional development? The mapping between theories and research questions (see

Figure 1) was presented. This research suggests that school administrators should create a teaching-focused environment and make teaching technologies more reliable to promote in-service teachers’ flow. Moreover, teacher education programs should raise pre-service teachers’ awareness of flow and inform them how to experience and re-enter flow during teaching, so that they can adapt to their future teaching in the workplaces.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Language Teachers’ Emotions: From Negative to Positive

Language teaching is a highly emotional profession as teachers constantly experience and regulate various emotions in the classroom (Ghanizadeh and Royaei [

1]). Previous studies have mainly focused on teachers’ negative emotions, such as anxiety (Tüfekçi-Can [

2]) and burnout (Engin and Treleaven [

3]). Some scholars have found that teachers’ positive psychology positively influences their professional well-being, as well as students’ performance (Day and Kington [

16]; Frenzel, Daniels and Burić [

4]). According to the Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions (Fredrickson [

5]), teachers’ positive emotions can broaden their mental resources and foster their greater openness and tolerance toward stress and pressure. Moreover, flow is found to be experienced by teachers when they motivate students to pursue and engage in their instructional goals (Csikszentmihalyi [

6]). Furthermore, flow plays an important role in helping teachers cope with instructional challenges (Dai and Wang [

7]).

2.2. Flow Theories: Three-Dimensional Framework and Dynamics

Flow, first conceptualized by Csikszentmihalyi (Csikszentmihalyi [

17]), refers to an enjoyable state of effortless absorption in an activity, mainly characterized by the sense of control, time distortion, deep absorption, and loss of self-consciousness (Barthelmäs and Keller [

11]). Time distortion refers to the perception that time passing feeling faster than usual. Deep absorption described a state of complete immersion in the activity. A sense of control means that individuals have no worries about the ongoing task. Loss of self-consciousness occurs when individuals stop focusing on themselves. Moreover, three key antecedents have been identified: clear goals, immediate feedback and a challenge-skill balance (Barthelmäs and Keller [

11]). This means flow often occur when individuals are familiar with the tasks, receive feedback on their performance, and perceive a balance between task challenges and their skills. Some scholars suggested that flow occurs when individuals perceived the challenge slightly exceed their skills (Jackson and Marsh [

18]). However, Nakamura, Tse and Shankland [

12] emphasized that the connection between a challenge-skill balance and flow is affected by individual traits. Therefore, it is necessary to take individual characteristics into account when exploring the flow experiences. Based on prior findings, Barthelmäs and Keller [

11] proposed the three-dimensional flow theory, which consists of the antecedents, experiential feelings, and consequences of flow. Moreover, flow experiences are susceptible to various factors, therefore the re-engagement after flow disruptions should be considered to explore the dynamics of flow (Nakamura, Tse and Shankland [

12]).

2.3. Empirical Studies on EFL Teachers’ Flow

In recent years, extensive empirical studies on in-service EFL teachers’ flow have emerged, focusing on the antecedents, disruptions, and consequences of flow. First, previous research has indicated that teachers’ personal cognitive and emotional traits are main contributors to flow experiences. Tardy and Snyder [

10] revealed that ten in-service EFL teachers experienced flow during moments of high interest, and when unplanned situations happened during teaching. Cohen and Bodner [

19] discovered that teachers with different levels of teaching experience differed in their flow, with experienced teachers entering flow more easily. Chen et al. [

20] found that teachers’ flow experience changed as their teaching experience accumulated. Sobhanmanesh [

9] highlighted the role of personal curiosity in flow as it enables teachers to tolerate greater challenges during teaching. Moreover, some scholars emphasized that contextual factors in the workplace facilitate teachers’ flow. Basom and Frase [

21] pointed out that teachers consider the principal’s visits as a sign of care for their teaching, which can motivate professional recognition and involvement, thereby supporting their flow. In addition, students’ immediate responses (Tardy and Snyder [

10]), and peer interaction (Khajavi and Abdolrezapour [

13]) are also found to facilitate in-service EFL teachers’ flow. Second, performance anxiety has been found to cause disruptions in flow (Fullagar, Knight and Sovern [

22]). Similarly, Dewaele and MacIntyre [

22] argued that language anxiety and threats to one’s sense of self and identity can interrupt language teachers’ flow. Furthermore, Khajavi and Abdolrezapour [

13] found that students’ behaviors and thought patterns, and technical obstacles can impede EFL teachers’ flow. However, despite much research on flow disruptions, little attention has been paid to how EFL teachers re-enter to flow during teaching. Third, some research revealed that EFL teachers’ flow experiences played a crucial role in their motivation, professional growth, and well-being. Landhäußer and Keller [

23]asserted that the enjoyment during flow motivated teachers to improve their professional skills, thereby enhancing professional well-being and meaning in life. They also suggested that flow can force teachers to engage in self-exploration and search for ways to improve themselves. Dai and Wang [

7] claimed that flow can stimulate teachers’ work engagement, and change teachers’ career motivation. Tardy and Snyder [

10] also found that EFL teachers’ flow shapes their teaching practices. Landhäußer and Keller [

23]summarized three aspects of positive influences of flow, including affective, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions.

2.4. Research Gap and Rationale

Despite the solid theoretical foundation for this research, several gaps remain to be addressed. First, although some scholars have examined flow disruptions, little attention has been paid to the re-engagement of flow after disruptions. This is a key aspect to understand the dynamic nature of flow. Secondly, existing studies focused on in-service teachers, overlooking pre-service teachers who are in the crucial stage of professional development (Bal-Gezegin, Balikçi and Gümüsok [

15]). To fill these gaps, this research adopted the thematic narrative method to examine pre-service and in-service EFL teachers’ flow experiences, involving the antecedents, feelings, disruptions and coping strategies, as well as consequences of participants’ flow.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Setting

The pre-service teachers participated in an English teaching program affiliated with the Department of Foreign Language of a Normal University in Henan Province, China. This program served as an in-school practicum platform for English education majors, rather than a formal school setting. It was established in December 2023 to enrich English education majors’ teaching experience. Approximately twenty children participated in the classes, all of whom were English beginners aged six to nine. One lesson was held each weekend, and each teaching session lasted for sixty minutes. The teaching materials were taken from People’s Education Press (PEP) Grade 3 English textbook (2012), as formal English classes officially started in Grade 3 (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China [

24]).

Additionally, three in-service teachers worked in public primary schools in China. Each of their classes comprised nearly forty students. Both Deli and Ella taught the same school in Zhengzhou, the capital city of Henan province. However, Francia worked in a remote town in Shaanxi Province. These regional differences resulted in two main distinctions. The first was teaching tools: Deli and Ella’s classrooms were well-equipped with advanced teaching facilities, which enabled teachers to integrate various technologies during teaching. In contrast, Francia mainly relied on technologies to present PPT slides. Another difference concerned students’ exposure to English. Deli and Ella’s students were exposed to English earlier than Francia’s students, who learned English in formal classes. Moreover, Deli and Francia taught Grade 3 English lessons with the 2024 edition of the PEP textbook, whereas Ella taught Grade 6 English classes with the 2012 edition of PEP English textbook. According to the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China [

25], a new round of English textbook reform was implemented to Grade 3 English textbooks but was not extended to Grade 6.

3.2. Participants

Purposeful sampling was employed to explore EFL teachers’ flow experiences, as this method enables researchers to collect the data that are relevant to the research purpose (Creswell [

26]). Six EFL teachers were selected as participants because the chosen cases were information-rich and themes stabilized by the sixth interview. Three pre-service teachers were English education majors participating in the teaching program. Before participating the program, pre-service teachers completed core courses on English teaching methods and lesson design. After entering this event, they served as teaching assistants, helping the teachers with instruction and observing how the classes were delivered. Three weeks later, pre-service teachers began preparing for their first classes. All pre-service teachers reported experiencing teaching anxiety, though they slightly differed. Anna described herself as a creative teacher. Beth identified herself as sensitive and prone to self-doubt. Cathy appeared open-minded.

Three in-service teachers worked in public elementary schools. Both Ella and Francia had five years of teaching experience, whereas Deli had two years of teaching experience. In Deli’s and Ella’s classes, various technologies were used in their classes to create an engaging classroom atmosphere. However, Francia mainly used PPT sides or simply on textbooks to deliver her lessons. A notable feature of Francia’s teaching was her dual-language teacher identity. She was asked to teach both English and Chinese because her school lacked sufficient English teachers. This phenomenon, in which young teachers were asked to teach subjects outside their major, was common in remote rural schools in China (Chang and Wang [

27]).

Table 1.

Demographic Information of Participants.

Table 1.

Demographic Information of Participants.

| Participants |

Role |

Years of experience |

School context |

Grade level |

Location |

English major |

| Anna |

pre-service |

0 |

on-campus internship |

3 |

urban |

yes |

| Beth |

pre-service |

0 |

on-campus internship |

3 |

urban |

yes |

| Candy |

pre-service |

0 |

on-campus internship |

3 |

urban |

yes |

| Deli |

In-service |

2 |

public primary school |

3 |

urban |

yes |

| Ella |

In-service |

5 |

public primary school |

6 |

urban |

yes |

| Francia |

In-service |

5 |

public primary school |

3 |

rural |

no |

3.3. Data Collection

Data collection for this research lasted for one year, from September 2024 to August 2025. Prior to the formal collection, the researcher contacted all participants separately to introduce the research topic and obtain their informed consent. Semi-structured interviews were conducted twice with each participant online due to geographical constraints. Each interview lasted for about 90 minutes. The first interview aimed to explore the participants’ flow experiences. During interviews, participants were asked the following prepared questions: (1) Did you experience flow during teaching? (2) Could you describe how you were feeling during flow? (3) Could you describe what contributed to the occurrence of your flow? (4) Could you describe what disrupted your flow and how you coped with the situations? (5) How did you perceive the significance of flow for your professional growth? To aid recalling of specific events, the researcher played participants’ teaching videos during interviews. In the second interview, the researcher asked each participant the questions (see

Appendix A) that had not been included in the first interview but were mentioned by other participants. For instance, “Did you feel that the new textbook was so challenging that it triggered disruptions in your flow?” This interview helped to gain a deeper insight into EFL teachers’ flow and find shared patterns and differences. Furthermore, participants’ teaching documents and videos were also collected to have a better understanding of their classes and the smooth and disruptive moments during teaching.

3.4. Data Analysis

This research employed a thematic narrative approach to examine interview data, which allowed the researcher to identify shared patterns across narratives while preserving the integrity of individual stories (Riessman [

28]). This study aimed to identify the recurring patterns in participants’ flow experiences and captured individual differences through illustrative narratives. The analysis was guided by the three-dimensional flow theory (Barthelmäs and Keller [

11]), involving antecedents, experiential features, and consequences. Moreover, the perspective of flow dynamics proposed by Nakamura, Tse and Shankland [

12]was incorporated to emphasize the flow disruptions and re-engagement.

Before the formal analysis, the researcher first familiarized herself with the data by reviewing interview transcripts. During the coding process, a hybrid deductive and inductive coding approach was employed. Initially, four theoretical dimensions served as the analytical framework including: (1) Antecedents of flow, (2) Feelings during flow, (3) Flow disruptions and coping strategies, and (4) Consequences of flow. For example, when participants stated, “I felt that time went faster than usual,” which was identified as the pattern time distortion corresponding to the theme feelings during flow. However, certain aspects of the data were not fully captured by the theories, such as specific dimensions of flow antecedents, disruptions and coping strategies, and consequences. To address this, data-driven inductive coding was conducted to identify common patterns emerging from participants’ quotes. For instance, when participants expressed, “students’ indifference embarrassed me,” “students’ cries made me nervous,” and “students’ distorted values annoyed me,” which were all grouped into the pattern student-related factor, which were associated with the theme flow disruptions.

Additionally, narrative analysis was employed to describe the whole story of three teachers’ flow experiences, considering the dynamics and situational characteristics of flow (Nakamura, Tse and Shankland [

12]). Three teachers’ flow experiences were selected as representative cases due to Beth’s flow disruptions caused by strong self-consciousness, Ella’s curiosity for teaching as an antecedent of flow, and Francia’s flow disruptions due to her identity as a non-English major English teacher and school limitations. The overall narratives of three representative cases helped to develop a better grasp of the dynamics of EFL teachers’ flow experiences.

3.5. Ethical Considerations and Trustworthiness

This research followed the key ethical principles of respect for persons, concern for welfare, and justice (Creswell [

26]). Before data collection, the researcher obtained permission from the program organizer in the university’s English department. Informed consent was obtained from all six participants. Participants were introduced to the research purpose, procedures, and their rights. Besides, pseudonymous was used to protect their privacy. Moreover, the researcher expressed thanks for participants’ cooperation by offering small gifts or a modest financial compensation.

To enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of the research, member checking, peer debriefing and data triangulation were employed. First, the preliminary results were returned to participants for confirmation and feedback. Second, a qualitative researcher was invited to review the coding framework and thematic interpretations. Third, data triangulation was achieved through multiple data sources, with interview transcripts as main data and participants’ teaching videos and materials as supplementary sources. Prior to interviews, teaching materials and videos were reviewed to identify salient episodes (e.g., technological breakdowns, pauses, etc.). Moreover, the videos were replayed during interviews to prompt participants’ recall of specific flow episodes.

The researcher held a master’s degree in English education from the same university as the three pre-service teachers, which provided an insight of pre-service teachers’ backgrounds. What’s more, there was no assessment authority over them or conflict of interest because the researcher had graduated when all pre-service teachers attended the program. Furthermore, the researcher had part-time English teaching experience, which fostered her empathy with participants. To minimize researcher influence, interviews prioritized open-ended prompts and minimal the researcher intervention, followed by probes questions targeting inconsistencies and alternative interpretations.

4. Findings

This section presents a cross-case analysis of six participants’ flow experiences, including three pre-service (Anna, Beth and Cathy) and three in-service EFL teachers (Deli, Ella and Francia). Their flow experiences are shown through the following four themes: (1) Antecedents of flow, (2) Feelings during flow, (3) Flow Disruptions and coping strategies, and (4) Consequences of flow. Under the four themes, “x/y” was used to showcase how many participants clearly mentioned the patterns in their interviews (e.g., 5/6 means 5 out of 6 mentioned it. Then, three representable cases are narrated.

4.1. Antecedents of Flow

One notable theme concerns the antecedents of flow. All EFL teachers (6/6) indicated that students’ immediate feedback, clear teaching goals, and a challenge-skill balance facilitated their flow. As Anna mentioned, “They all raised hands, which gave me a sense of control (A_1_2024/9/21).” Students’ positive responses increased teachers’ sense of control, thereby facilitating entry into flow. Clear teaching goals helped teachers enter their flow. As Deli said, “Clear teaching goals made me at easy during teaching (D_1_2025/6/7).” This suggests clear goals directed their teaching and relax themselves, thus helping their flow. Furthermore, the English-major teachers (5/6) mentioned tasks that slightly exceeded their skills yet remained manageable. Beth stated, “The challenging but manageable tasks made me attentive (B_1_2024/10/19).” This suggests that challenging but manageable tasks sustained teachers’ attention, facilitating their flow. By contrast, the non-English-major teacher (1/6) said she entered flow if teaching content was easy for her. Francia reported, “The easiness of teaching content built up my confidence (F_1_2025/6/14).” These findings show that teachers with different background perceived a challenge-skill balance differently.

Additionally, all three in-service teachers (3/6) highlighted the importance of teaching experience, technology support, the principal’s philosophy of teaching-focused and the curiosity for teaching. The teachers reported that their flow was facilitated by prior teaching experience. As Ella claimed, “Familiarity with students’ individual differences and teaching process allowed me to be calm and flexible in class (E_1_2025/7/12).” Teaching experience enabled the teacher to be more adaptive during teaching. Moreover, the urban in-service teachers (2/6) spoke of technology support. Deli sated, “FlexClip 3D animation feature kept everyone immersed (D_1_2025/6/7).” Technologies not only helped teachers create an engaging atmosphere but also enhanced their immersion during teaching, thereby facilitating their flow. Besides, the principal’s teaching-focused philosophy was also emphasized. As Ella mentioned, “Principal’s focus on teaching informs me that I’m doing something meaningful, so I was more focused on teaching (E_1_2025/7/12).” This indicates that the principal’s teaching-focus philosophy enhanced teachers’ career recognition and maintained their concentration on teaching. Finally, one in-service teacher (1/6) highlighted her curiosity for teaching. Ella said, “I saw teaching as experiments where I kept thinking and adjusting, which drives me to explore more during teaching (E_1_2025/7/12).” This reflects that teachers’ teaching curiosity sustained attention, thereby helping her enter flow states.

Table 2.

Thematic Analysis of Antecedents of Flow in Participants.

Table 2.

Thematic Analysis of Antecedents of Flow in Participants.

| Theme |

Patterns |

Frequency |

Quotes |

Research Question |

| Antecedents of Flow |

Students’ immediate feedback |

6/6 |

They all raised hands, which gave me a sense of control (A_1_2024/9/21). |

What triggers flow in pre-service and in-service EFL teachers? |

| Clear goals |

6/6 |

Clear teaching goals made me at easy during teaching (D_1_2025/6/7). |

| Challenge-skill balance |

6/6 |

The challenging but manageable tasks made me attentive (B_1_2024/10/19).

The easiness of teaching content built up my confidence (F_1_2025/6/14). |

| Teaching experiences |

3/6 |

Familiarity with students’ individual differences and teaching process allowed me to be calm and flexible in class (E_1_2025/7/12). |

| Technology support |

2/6 |

FlexClip 3D animation feature kept everyone immersed (D_1_2025/6/7). |

Principal’s teaching-focused

philosophy |

2/6 |

Principal’s focus on teaching informs me that I’m doing something meaningful, so I was more focused on the teaching (E_1_2025/7/12). |

| Teaching curiosity |

1/6 |

I saw teaching as experiments where I kept thinking and adjusting, which drives me to explore more during teaching (E_1_2025/7/12). |

4.2. Feelings During Flow

Another salient theme concerns EFL teachers’ feelings during flow. The analysis revealed that all EFL teachers (6/6) felt time passed faster than usual during flow. As Anna said, “When I see the watch, oh~, 20 minutes passed (A_1_2024/9/21).” Moreover, all participants (6/6) reported experiencing a sense of control and deep absorption during flow. As Candy mentioned, “I felt that the class was under my control (C_1_2024/10/26).” Moreover, Deli claimed, “I was fully absorbed during teaching (D_1_2025/6/7).” Notably, two in-service teachers (2/6) with five-year teaching experience mentioned the loss of self-consciousness during flow, which wasn’t observed among the pre-service teachers and one in-service teacher with two-year teaching experience. As Ella explained, “With five-year experience, I have adapted to the (teaching) process so I can devote myself to it (E_1_2025/7/12).” However, Deli noted, “I was often distracted by the time allocated for each segment of the class (D_1_2025/6/7).”

Table 3.

Thematic Analysis of Feelings during Flow in Participants.

Table 3.

Thematic Analysis of Feelings during Flow in Participants.

| Theme |

Patterns |

Frequency |

Quotes |

Research Question |

| Feelings during Flow |

Time distortion |

6/6 |

When I see the watch, oh~, 20 minutes passed (A_1_2024/9/21). |

What do pre-service and in-service EFL teachers feel during flow?

|

| A sense of control for class |

6/6 |

I felt that the class was under my control (C_1_2024/10/26). |

| Deep absorption |

6/6 |

I was fully absorbed during teaching (D_1_2025/6/7). |

| Loss of self-consciousness |

2/6 |

I didn’t notice the outside and hear the bell, and I lost self-awareness (F_1_2025/6/14). |

4.3. Flow Disruptions and Coping Strategies

The data indicate that participants’ flow was disrupted by multiple factors. First, all EFL teachers (6/6) reported that their flow was impeded by student-related factors, like students’ indifference, talking back to teachers, inappropriate actions, distorted values, disagreement with teachers, and cries. As Anna said, “Students’ indifference embarrassed me (A_1_2025/6/7).” Students’ indifference distracted Anna’s attention and reduced her sense of control, thereby impeding her flow. Second, 6/6 teachers said that their flow was stopped by the technological breakdowns. Ella stated, “The breakdown of technological equipment raised my concern about the completing the class (E_1_2025/7/12).” This shows that technological breakdowns raised teachers’ concerns about the completion of lessons and interrupted their flow. Third, 4/6 teachers identified strong self-consciousness as flow disruptions. Two teachers (2/6) conveyed concerns about potential evaluations from surroundings on their teaching. Anna noted, “My imagination of student parents’ evaluation distracted my attention (A_1_2024/9/21).” Another two teachers (2/6) spoke of their internal conflict during teaching. Beth stated, “My internal conflict about praising student led to my shame (B_1_2024/10/19).” The results indicate that teachers’ self-consciousness interrupted their attention during teaching, thereby disrupting their flow.

Interestingly, all in-service teachers (3/6) claimed that their flow was also influenced by some institutional and situational factors. First, all in-service teachers (3/6) mentioned non-instructional duties. As Deli complained, “The non-instructional duties made me tired and distracted my attention in class (D_2_2025/8/24).” This suggests that teachers’ physical and mental states declined due to overload non-instructional tasks, thereby interrupting their flow. Second, two in-service teachers (2/6) noted the challenging new textbook. As Francia said, “The increased difficulty of new textbook induced my teaching anxiety (F_2_2025/8/19).” This illustrates that the higher difficulties of the new textbook triggered their anxiety during teaching and thus disrupted their flow. Lastly, two in-service teachers (2/6) emphasized principal’s sporadic visits. As Ella complained, “Principal’s sporadic visits distracted my attention (E_2_2025/8/23).” This indicates that principal’s visits interrupted teachers’ attention during teaching since teachers worried if they performed well.

Table 4.

Thematic Analysis of Flow Disruptions and Coping Strategies in Participants.

Table 4.

Thematic Analysis of Flow Disruptions and Coping Strategies in Participants.

| Theme |

Patterns |

Frequency |

Quotes |

Research Question |

Flow

Disruptions |

Student-related factors |

6/6 |

Students’ indifference embarrassed me (A_1_2025/6/7). |

What disrupts flow in pre-service and in-service EFL teachers, and how they re-enter flow after disruption?

|

| Technological breakdowns |

5/6 |

The breakdown of technological equipment raised my concern about completing the class (E_1_2025/7/12). |

| Strong self-consciousness (P125) |

4/6 |

My imagination of student parents’ evaluation distracted my attention (A_1_2024/9/21).

My internal conflict about praising student led to shame (B_1_2024/10/19). |

| Non-instructional duties |

3/6 |

The non-instructional duties made me tired and distracted in class (D_2_2025/8/24). |

| Curriculum reform |

2/6 |

The increased difficulty of new textbook triggered my teaching anxiety (F_2_2025/8/19). |

| Principals’ visit |

2/6 |

Principal’s sporadic visits distracted my attention (E_2_2025/8/23). |

| Coping Strategies |

Focusing on problem-solving |

6/6 |

Devoting myself to solving the technological problem calmed me down and reduce panic (E_2_2025/8/23). |

| Ignoring students’ misbehaviors |

5/6 |

Ignoring their misbehaviors can reduce my nervousness (C_1_2024/10/26). |

| Adopting a long-term teaching belief |

3/6 |

Knowing about poorly learned knowledge could be reviewed and practiced in later classes alleviated my worries (D_1_2025/6/7). |

| Lowering the teaching goals |

3/6 |

Focusing on the main teaching content reduced my mental stress and sense of guilt (F_2_2025/8/19). |

| Avoiding eye contact with students |

1/6 |

I avoided eye contact with students, which helped me alleviate my internal conflict (B_1_2024/10/19). |

The analysis shows that participants adopted various strategies to cope with flow disruptions. First, all EFL teachers (6/6) mentioned focusing on problem-solving. As Ella said, “Devoting myself to solving the technological problem calmed me down and reduce panic (E_2_2025/8/23).” It helped them forget the uncomfortable emotions (e.g., panic, nervousness, etc.), thereby enabling them to re-enter their flow. Second, pre-service teachers (3/6) preferred avoidance strategies to alleviate their negative emotions, thus helping them re-enter their flow. As Beth said, “I avoided eye contact with students, which helped me alleviate my internal conflict (B_1_2024/10/19).” Moreover, two pre-service teachers (2/6) chose to ignore students’ misbehaviors as they couldn’t find effective ways. As Candy expressed, “Ignoring their misbehaviors can reduce my nervousness (C_1_2024/10/26).”

However, in-service EFL teachers tended to use more flexible ways to address flow disruptions. All in-service teachers (3/6) noted a long-term teaching belief. As Della stated, “Knowing about poorly learned knowledge could be reviewed and practiced in later classes alleviated my worries (D_1_2025/6/7).” This shows that teachers’ worries were relieved when they knew review and practice could be conducted to consolidate students’ learning. Moreover, two in-service teachers (2/6) mentioned lowering teaching goals. As Francia claimed, “Focusing on the main teaching content reduced my mental stress and sense of guilt (F_2_2025/8/19).” This indicates that lowering goals reduced the challenge-skill mismatch, allowing teachers to reenter flow.

4.4. Consequences of Flow

The final theme concerns the consequences of flow. First, all teachers (6/6) reported that students’ positive responses during flow built their teaching confidence. As Beth noted, “The smooth process increased my confidence by reducing my anxiety during teaching (B_1_2024/10/19).” This shows that teachers’ anxiety during teaching was alleviated and confidence could be enhanced through the perception of teaching success in flow. Second, most EFL teachers (5/6) claimed that their ability to make adaptive decisions was enhanced. As Anna said, “The immersion state is conducive to my creative ideas during teaching (A_2_2024/11/11).” This indicates that teachers demonstrated greater adaptability when they felt immersed during teaching during flow. Third, some EFL teachers (4/6) stated their intrinsic drive for professional growth was strengthened by the sense of meaning in life during flow. Francia claimed, “The sense of meaning in life enhanced my intrinsic drive for my professional growth (F_2_2025/8/19).” Fourth, four teachers (4/6) said that enjoyable experiences motivated them to reflect on their teaching so that they could experience flow frequently. As Ella mentioned, “The enjoyable experience motivated me to summarize what made the lesson successful (E_2_2025/8/23).” Fifth, all in-service teachers (3/6) said that their professional well-being was increased because of students’ active engagement during flow. Della stated, “The active atmosphere reinforced my belief that teacher is fulfilling profession (D_2_2025/8/24).” Finally, two pre-service teachers (2/6) said that the enjoyment experienced during flow shifted their career motivation from external recognition to internal satisfaction. As Candy said, “The enjoyment in flow shifted my career motivation from external recognition to internal satisfaction (C_2_2024/11/11).

Table 5.

Thematic Analysis of Consequences of Flow in Participants.

Table 5.

Thematic Analysis of Consequences of Flow in Participants.

| Theme |

Patterns |

Frequency |

Quotes |

Research Question |

Consequences

of flow |

Teaching confidence |

6/6 |

The smooth process increased my confidence by reducing my anxiety during teaching (B_1_2024/10/19). |

How does flow affect pre-service and in-service EFL teachers’ professional development?

|

| Making adaptive decisions in class |

5/6 |

The immersion state is conducive to my creative ideas during teaching (A_2_2024/11/11).” |

| Professional development drive |

4/6 |

The sense of meaning in life enhanced my intrinsic drive for my professional growth (F_2_2025/8/19). |

| Post-lesson reflection |

4/6 |

The enjoyable experience motivated me to summarize what made the lesson successful (E_2_2025/8/23). |

| Professional well-being |

3/6 |

The active atmosphere reinforced my belief that teacher is a fulfilling profession (D_2_2025/8/24). |

| Career-motivation shift |

2 |

The enjoyment in flow shifted my career motivation from external recognition to internal satisfaction (C_2_2024/11/11). |

4.5. Three Representable Cases’ Flow Experiences

4.5.1. Beth’s Flow Experience

Beth reported her flow experiences during teaching, despite feeling a little nervous at the beginning of the class. Before conducting the teaching, she made full preparation, which made her familiar with the teaching content and process. Moreover, Beth added that students’ positive responses in class brought her much teaching confidence, thereby helping her enter flow. Then, Beth recalled she had the sense of control, deep absorption, time flying faster than normal during flow. However, Beth didn’t experience loss of self-consciousness for not being adapted for teaching. Furthermore, Beth encountered flow disruptions due to strong self-consciousness. As she said, “When I praised students with thumb-ups and exaggerated facial expressions, I felt unease (B_1_2024/10/19).” This is because these actions or words are not a part of her communication in real life (e.g., thumb-up, ‘wow, you’re so great). Hence, the unfamiliar expressions triggered internal conflict, thereby stopping her flow. To address it, she tried to avoid eye contact with students to find inner peace and reenter the teaching process. Finally, Beth summarized that the enjoyment during flow informed her that there was no need to be nervous in future classes and motivated her to search for more effective teaching materials. Moreover, she reported that her career motivation shift from external respect to internal pleasure during teaching.

4.5.2. Ella’s Flow Experience

Ella often adopted technologies to set up an engaging learning environment during instruction. For instance, Ella transformed students’ paintings into 3D animation on the Flexclip, which motivated students’ participation in class and kept her attention to teaching, helping her flow experiences. Besides, Ella stated that she always devoted herself to improving her teaching due to her strong teaching curiosity. This constant thinking process enabled her immersed during teaching. As she said, “I saw teaching as experiments where I kept thinking and adjusting, which drives me to explore more during teaching (E_1_2025/7/12).” Moreover, Ella also reported her principal’s teaching-focused philosophy kept her attention through enhancing her professional recognition. As Ella said, “Principal’s focus on teaching informs me that I’m doing something meaningful, so I was more focused on teaching (E_1_2025/7/12).”

In addition, Ella noted her feeling of loss of self-consciousness during flow, other than enjoyment, deep absorption, sense of control, and distortion of time track. However, Ella’s flow was impeded when technologies went wrong or students misbehaved. To address the situations, Ella focused on the technical issues, temporarily ignored the problems, lowered teaching goals, or adopted the long-term teaching belief to sustain the teaching smoothly and re-enter their flow. Finally, Ella reflected that the enjoyment during flow enhanced her professional well-being and motivated her post-class reflection. In practice, Ella often experimented with strategies to reach flow across different groups of students. For example, she found her students in a low-level class, showed more interest in materials related to familiar lives. Thus, she collected some photos of students’ pets to attract their attention and engage them in class.

4.5.3. Francia’s Flow Experience

Francia, a non-English-major English teacher, noted that her lack of confidence influenced the antecedents of her flow. Unlike the other five English education major teachers more attentive when tasks slightly exceeded skills, Francia expressed that the easy teaching content brought her much relaxation during teaching, helping her enter flow. As she mentioned, “The easiness of teaching content built up my confidence (F_1_2025/6/14).” Moreover, Francia mentioned the sense of loss of self-consciousness other than the common feelings. Francia explained that she had much autonomy during teaching at school, if students positively responded to her, then she would enjoy the teaching and sometimes couldn’t even notice the class bell. Furthermore, Francia’s dual-language teacher identity led to inner conflict when giving a class about Christmas, because her appreciation for Chinese culture clashed with the content about Western festivals. Moreover, Francia noted the increased difficulty of the new textbook induced her teaching anxiety due to her non-major English teacher identity when seeing many unfamiliar words during teaching. Furthermore, students’ distorted values, such as laughing at the photos of kids with black skin annoyed her, which disrupted her flow. To re-enter flow, Francia attempted to teach them correct values, which helped her regulate her emotions and re-enter her flow. Finally, Francia highlighted the immersion and pleasure during flow brought her a sense of meaning in life and strengthened her motivation to increase English teaching skills.

5. Discussion

The analysis revealed three new insights into EFL teachers’ flow experiences. First, experienced EFL teachers reported a loss of self-consciousness during flow whereas less experienced teachers dis not. Second, in-service EFL teachers encountered more complex, institution-level disruptions during flow. Finally, teachers employed different strategies to re-enter their flow, depending who they were and what disrupted them.

This research found that experienced teachers (with five years of teaching experience) experienced a loss of self-consciousness during flow. This finding is consistent with the core experiential features of flow proposed by Csikszentmihalyi [

8]. Moreover, it also confirmed Cohen and Bodner [

19] conclusion that individuals’ experience could enhance their immersion in activities and facilitated their flow entry. However, pre-service and less experienced teachers’ attention was likely to be distracted during teaching (Simpson, Vondrová and Žalská [

29]). Therefore, they haven’t experienced the loss of self-consciousness as they were unable to completely immerse themselves in classes.

Unlike previous findings on EFL teachers’ flow disruptions (Tardy and Snyder [

10]; Khajavi and Abdolrezapour [

13]; Dewaele and MacIntyre [

14]), the present findings revealed that in-service teachers’ flow was also disrupted by institutional factors. It was discovered that non-instructional tasks, increased textbook difficulty due to curriculum reform, and principal’s sporadic visits could interrupt in-service teachers’ flow. This new finding responded to the perspective of high emotionality of language teachers (Strom and Viesca [

30]). Teachers would experience mental stress or distraction during teaching when unbearable situations occurred because they were often beyond teachers’ control. Thus, it is necessary to consider more situational and institutional factors in exploring EFL teachers’ flow experiences.

Another new finding concerns the coping strategies of participants’ flow disruptions in response to the appeal by Nakamura, Tse and Shankland [

12]for the re-engagement of flow. The data indicated that pre-service teachers tended to use avoidance strategies, like avoiding eye contact with students and ignoring students’ disruptive behaviors, to regulate their nervousness and embarrassment. This could be understood from the perspectives that pre-service teachers lacked of teaching confidence and classroom management experience (O’Neill and Stephenson [

31]). When they faced challenges during teaching, they preferred to adopt avoidance strategies to find their inner peace (Ay and Gökdemir [

32]; Huang and Zhou [

33]). Conversely, in-service teachers preferred more flexible strategies, like focusing on problem-solving, lowering teaching goals, and using the long-term teaching belief to alleviate stress and anxiety. The difference highlights the crucial role of classroom management skills and accumulated teaching experience in shaping their coping strategies for flow disruptions (Korkut [

34]).

This research has several limitations. Firstly, this study investigated pre-service and in-service EFL teachers’ flow experiences in the specific context of teaching. However, individuals’ flow may differ in different situations (Csikszentmihalyi [

17]). Future research could complement these findings by considering the difference between the two groups of EFL teachers’ flow in other situations, like leisure time. Secondly, this study explored participants’ flow experience at the specific stage of professional development. According to Chen et al. [

20], teachers’ flow may change as their teaching experience increased. Thus, future researchers can conduct longitudinal studies examining the trajectory of flow experiences among EFL teachers across different stages of career development. Finally, the participants in this research were from a limited region in China. Future research is encouraged to be conducted in more different countries and districts to provide a more comprehensive understanding of EFL teachers’ flow experiences.

6. Conclusions and Implication

The purpose of this research was to investigate the dynamics of pre-service and in-service EFL teachers’ flow experiences, focusing on the antecedents, feelings, disruptions and coping strategies, and consequences of flow. First, all participants reported three common antecedents of flow: clear teaching goals, students’ immediate feedback, and a challenge-skill balance. Moreover, variations were observed in the perception of a challenge-skill balance and flow dynamics across participants’ professional backgrounds. Second, this study also identified the common feelings during flow including deep absorption, a sense of control, and time distortion. Third, the data indicated participants’ flow is impeded by student-related factors and their own strong self-consciousness. Finally, this study found that teachers’ flow had a positive influence on their professional development. Flow facilitated EFL teachers’ teaching anxiety reduction, confidence improvement and pre-service teachers’ career shift from external recognition and internal pleasure. For in-service teachers, flow facilitated their professional well-being, post-reflection and professional development.

Additionally, several new findings emerged in this research. First, the loss of self-consciousness was identified as an uncommon feature during flow, and it often occurred among experienced teachers. For the teachers who had not adapted to their work might have failed to reach the state of losing self-consciousness. Second, the disruptive factors affecting in-service teachers’ flow were complicated. They reported some institutional factors (e.g., non-instructional duties, curriculum reform, principal’s visits) interrupted their flow. Finally, this research displays how EFL teachers re-enter their flow after disruptions, which has been largely ignored in previous studies. It was found that pre-service teachers preferred avoidance strategies due to low teaching confidence, while in-service teachers often utilized more flexible strategies, like focusing on problem-solving, lowering their teaching goals, and using the long-term teaching belief to alleviate their mental stress and concerns during instruction.

These findings have some implications for school administrators and teacher educators. School administrators are encouraged create a teaching-focused environment to promote in-service teachers’ flow experiences. Moreover, teacher educators are suggested to raise teacher candidates’ awareness of flow and equip them with strategies for experiencing and re-enter flow during teaching, thereby helping their adaptation to future teaching contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and J.K.; methodology, J.L. and J.K.; investigation, J.L. and J.K.; data analysis, J.L. and J.K.; composing of draft, J.L. and J.K.; review and editing of the draft, J.L. and J.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study met the exemption criteria under Regulation 104-2 and was granted an exempt determination 05, September 2024 for research involving normal educational issues within an educational environment (Protocol CNU-EC-2024-EX-019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this research are available on request from the first and corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Examples of Semi-Structure Interview Questions

Appendix A.1. The First Interview

Did you experience flow during teaching?

Could you describe how you were feeling during flow?

Could you describe what contributed to the occurrence of your flow?

Could you describe what disrupted your flow and how you coped with the situations?

How did you perceive the significance of flow for your professional growth?

Appendix A.2. The Second Interview

Did you feel that the task slightly higher than your skills helped to enter flow?

Did you feel that the principal’s sporadic visits interrupted your flow? And why?

Did you feel that the new textbook was so challenging difficult that triggered disruptions in your flow? And why?

Did you re-turn your flow though lowering teaching goals? Could you give some specific examples?

Did you re-turn your flow though ignore students’ behaviors? Could you give some specific examples?

Did you feel that flow changed your career motivation from external recognition to internal pleasure? And why?

Did you feel that flow experiences motivated you put more effort in professional growth? And why?

Did you feel that flow experiences improved your professional well-being? And why?

Did you feel that flow experiences supported your decision-making during teaching? Could you give some specific examples?

Did you feel that flow experiences motivated you to reflect your post-lesson reflection? Could you give some specific examples?

References

- Ghanizadeh, A.; Royaei, N. Emotional facet of language teaching: Emotion regulation and emotional labor strategies as predictors of teacher burnout. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning. 2015, 10, 139-150. [CrossRef]

- Tüfekçi-Can, D. Foreign language teaching anxiety among pre-service teachers during teaching practicum. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching. 2018, 5, 579-595. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1258444.

- Engin, Z.; Treleaven, P. Algorithmic government: Automating public services and supporting civil servants in using data science technologies. The Computer Journal. 2019, 62, 448-460. [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, A.C.; Daniels, L.; Burić, I. Teacher emotions in the classroom and their implications for students. Educational psychologist. 2021, 56, 250-264. [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American psychologist. 2001, 56, 218. [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. The flow experience and its significance for human psychology. In Optimal Experience: Psychological Studies of Flow in Consciousness, Csikszentmihalyi, M.C., Isabella S., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988; pp. 15-35.

- Dai, K.; Wang, Y.L. Investigating the interplay of Chinese EFL teachers’ proactive personality, flow, and work engagement. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 2025, 46, 209-223. [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Beyond boredom and anxiety; Jossey-bass: 2000.

- Sobhanmanesh, A. English as a foreign language teacher flow: How do personality and emotional intelligence factor in? Frontiers in Psychology. 2022, 13, 793955. [CrossRef]

- Tardy, C.M.; Snyder, B. ‘That's why I do it’: flow and EFL teachers’ practices. ELT journal. 2004, 58, 118-128. [CrossRef]

- Barthelmäs, M.; Keller, J. Antecedents, boundary conditions and consequences of flow. In Advances in Flow Research, Faull, S.W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 71-107.

- Nakamura, J.; Tse, D.C.K.; Shankland, S. Flow: The experience of intrinsic motivation. In The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation, Ryan, R.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 439–454.

- Khajavi, Y.; Abdolrezapour, P. Exploring English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers' experience of flow during online classes. Open Praxis. 2022, 14, 202-213. [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J.M.; MacIntyre, P. “You can’t start a fire without a spark”. Enjoyment, anxiety, and the emergence of flow in foreign language classrooms. Applied Linguistics Review. 2024, 15, 403-426. [CrossRef]

- Bal-Gezegin, B.; Balikçi, G.; Gümüsok, F. Professional Development of Pre-Service Teachers in an English Language Teacher Education Program. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching. 2019, 6, 624-642. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1246607.

- Day, C.; Kington, A. Identity, well-being and effectiveness: The emotional contexts of teaching. Pedagogy, culture & society. 2008, 16, 7-23. [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play; Jossey-bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000.

- Jackson, S.A.; Marsh, H.W. Development and validation of a scale to measure optimal experience: The Flow State Scale. Journal of sport and exercise psychology. 1996, 18, 17-35. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Bodner, E. The relationship between flow and music performance anxiety amongst professional classical orchestral musicians. Psychology of Music. 2019, 47, 420-435. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, L.; Jia, L.; AlGerafi, M.A. Flow experience and innovative behavior of university teachers: Model development and empirical testing. Behavioral Sciences. 2025, 15, 363. [CrossRef]

- Basom, M.R.; Frase, L. Creating optimal work environments: Exploring teacher flow experiences. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning. 2004, 12, 241-258. [CrossRef]

- Fullagar, C.J.; Knight, P.A.; Sovern, H.S. Challenge/skill balance, flow, and performance anxiety. Applied Psychology. 2013, 62, 236-259. [CrossRef]

- Landhäußer, A.; Keller, J. Flow and its affective, cognitive, and performance-related consequences. In Advances in Flow Research, Engeser, S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 65-85.

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Compulsory Education Curriculum Plan and Standards; Beijing, China, 2022-4-20 2022.

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Notice of the General Office of the Ministry of Education on Issuing the 2024 Catalogue of Nationally Approved Textbooks for Compulsory Education (Document No. 7, 2024). Available online: http://hudong.moe.gov.cn (accessed on 2024-8-2).

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002.

- Chang, X.; Wang, Z. Assessing the development of primary English education based on CIPP model—a case study from primary schools in China. Frontiers in Psychology. 2024, 15, 1273860. [CrossRef]

- Riessman, C.K. Narrative methods for the human sciences; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008.

- Simpson, A.; Vondrová, N.; Žalská, J. Sources of shifts in pre-service teachers’ patterns of attention: The roles of teaching experience and of observational experience. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education. 2018, 21, 607-630. [CrossRef]

- Strom, K.J.; Viesca, K.M. Towards a complex framework of teacher learning-practice. In Non-Linear Perspectives on Teacher Development, Kathryn J. Strom, T.M., Linda Abrams, Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 13-28.

- O’Neill, S.; Stephenson, J. Does classroom management coursework influence pre-service teachers’ perceived preparedness or confidence? Teaching and teacher education. 2012, 28, 1131-1143. [CrossRef]

- Ay, T.S.; Gökdemir, A. Perception of Peace among Pre-Service Teachers. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education. 2020, 9, 427-438. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Z.; Zhou, L.L. Self-care strategies for preservice teachers: a scoping review. Teachers and Teaching. 2025, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Korkut, P. Classroom Management in Pre-Service Teachers' Teaching Practice Demo Lessons: A Comparison to Actual Lessons by In-Service English Teachers. Journal of Education and Training Studies. 2017, 5, 1-17. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).