1. Introduction

Soil and water are the most important agriculture resources, serving as the foundation for food production and environmental sustainability [

1]. However, global transformations have caused climate change, population expansion, deforestation, urbanization, intensified agricultural practices, and the migration of subsistence farming to less fertile lands. These challenges underscore an urgent need to preserve these resources [

2] along with a need for robust soil and water conservation (SWC) efforts within the larger framework of ensuring food security. The United Nations' 2023 World Water Development Report [

3] highlights a concerning trajectory: the number of urban populations affected by water shortage is projected to rise from 933 million in 2016 to between 1.7 and 2.4 billion people by 2050 [

3]. This projected escalation in water stress necessitates both rigorous scientific research and the implementation of adaptive, evidence-based management practices. The urgency is particularly concerning for small-scale farmers in Africa, who are disproportionately affected by the multifaceted impacts of climate change and land degradation [

4].

Understanding the biophysical roles of soil and water is essential for formulating effective conservation strategies. Soil provides a medium for plant growth, carbon sequestration, nutrient cycling, water retention and root growth, making its quality a critical determinant of crop productivity [

5,

6]. On the other hand, water acts as a vital carrier of nutrients and a key driver of metabolic processes crucial for plant growth [

7]. The intricate relationship between soil and water management is central to optimizing agricultural productivity and ensuring food security [

8]. The degradation of these two pillars—through erosion, nutrient depletion, salinization, and erratic rainfall—threatens food systems and livelihoods, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa.

Sub-Saharan Africa exemplifies the urgency of this challenge, as land degradation continues to undermine agricultural systems and environmental sustainability [

8]. The African Union Commission estimates that 65% of African arable land is affected by degradation, contributing to declining soil fertility and agricultural productivity [

9]. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) reports that desertification affects around 45% of Africa’s land area, with 55% of this area at high or very high risk of further degradation [

10]. A study by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) highlights that soil erosion alone impacts roughly 43% of agricultural land across the continent [

11]. These statistics reveal the crises and reinforce the need for comprehensive strategies to combat land degradation, enhance climate resilience, and ensure long-term food security for the region’s growing populations.

Land degradation, soil-water scarcity, and climate change are intricately interconnected, collectively posing serious threats to agricultural sustainability and food security [

12,

13]. As climate change intensifies, shifting precipitation patterns and rising temperatures heighten the risk of land degradation. Intensive agricultural practices exacerbate this issue by contributing to soil erosion and nutrient depletion, accelerating degradation [

14]. Simultaneously, land degradation reduces the soil's water retention capacity, exacerbating soil-water scarcity [

15]. These interconnected challenges form a negative feedback loop, where degraded land becomes increasingly incapable of withstanding climate impacts, leading to a downward spiral of declining agricultural productivity. Breaking this cycle requires widespread adoption of sustainable land-management (SLM) practices. Through measures such as erosion control, water conservation, afforestation, conservation tillage, and watershed management, farmers can maintain soil health and improve water retention. Maintaining soil organic matter, coupled with installing SWC structures enhances overall ecosystem resilience. Education and extension services further ensure the widespread adoption of sustainable practices. By addressing the interconnected challenges of soil erosion, water scarcity, and climate change, these management strategies create a foundation for sustainable agriculture, fostering resilience, enhancing biodiversity, and securing long-term ecosystem viability [

16].

Senegal, situated in West Africa, experiences a predominantly arid to semi-arid climate, posing significant challenges to agriculture. The population has grown steadily, with a current estimate of over 18 million people in 2023 with a density of 92 people per km

2 [

17]. Agriculture is mostly rainfed, where less than 5% of cultivated land is irrigated [

18]. The agricultural economy is dominated by smallholder farmers cultivating maize, millet, rice, and sorghum for subsistence purposes [

19]. Recurrent droughts, periodic flooding, and land degradation driven by climate change are major factors contributing to stagnating farm productivity [

20]. Adoption of land and water management technologies among small-scale farmers in Senegal remains low [

21] compared to other African countries [

35], especially the neighboring countries of Burkina Faso and Niger. This is mainly due to weak institutional and policy frameworks, inadequate land tenure incentives, and fragmented, project-based implementation approaches [

22]. Many farmers still rely on harmful practices like bush burning, which degrades the soil, depletes organic matter, and increases erosion risks [

23]. Despite these impacts, traditional methods persist due to limited awareness of sustainable alternatives [

24]. Effective awareness campaigns, training, and supportive policies are essential for driving this transition [

25].

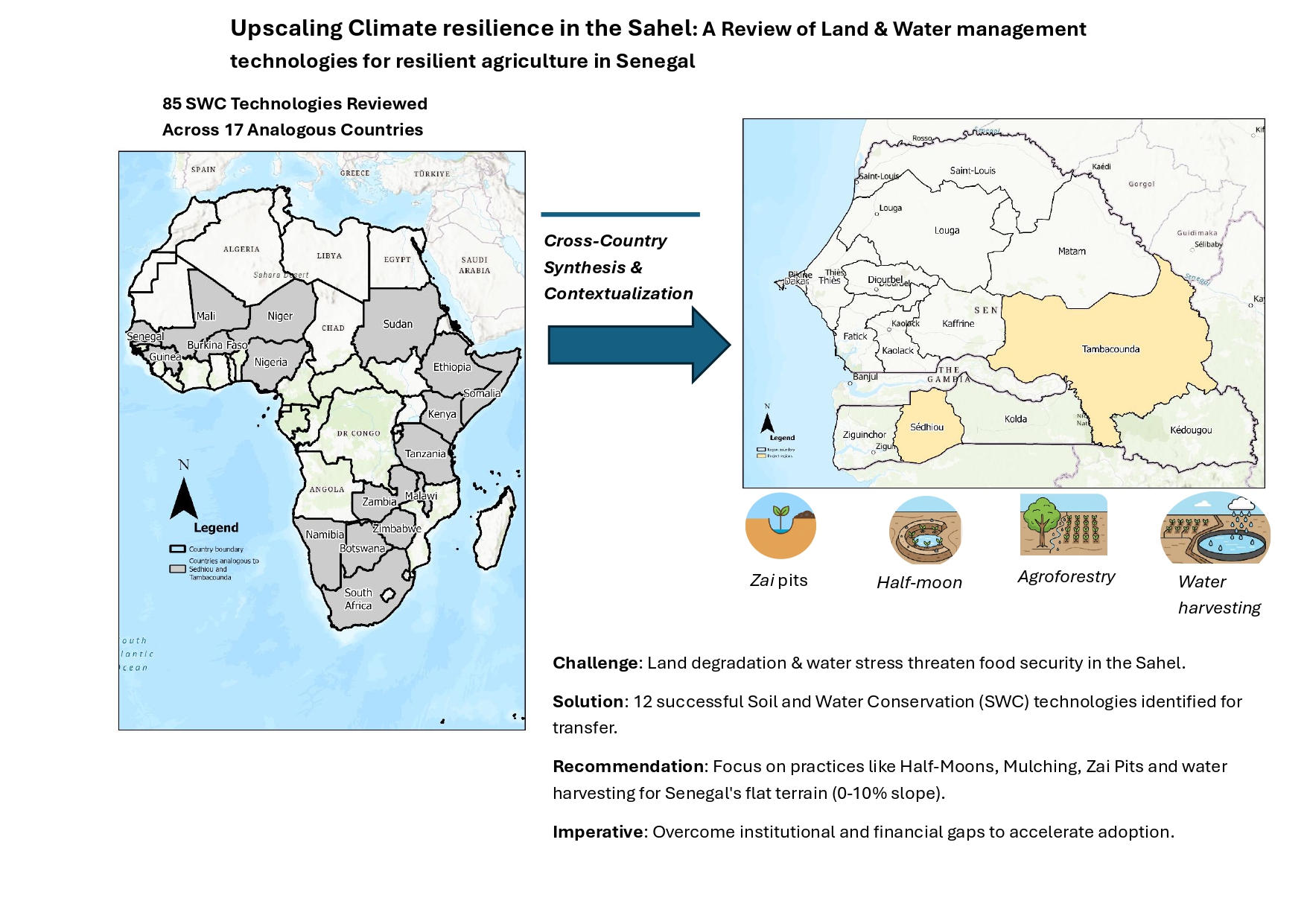

This review examines existing literature to identify effective soil and water management practices adopted across 17 selected sub-Saharan African countries, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions with climatic and agricultural conditions similar to those in Senegal and the broader Sahel. The objective is to highlight successful technologies that have been effectively implemented in these climate-analogous regions but remain underutilized in Senegal. The documented practices will be recorded and those that fit the Senegalese landscape and climate of Sédhiou and Tambacounda regions will be selected and recommended for adoption. By synthesizing regionally tested practices and aligning them with local needs, this review contributes to a deeper understanding of sustainable water resource management and their potential to transform agriculture in the region. Ultimately, it supports the development of resilient agricultural systems and a more secure future for communities in water-stressed environments. It informs technology transfer and adoption in the Sahel, with a focus on Senegal.

2. Materials and Methods

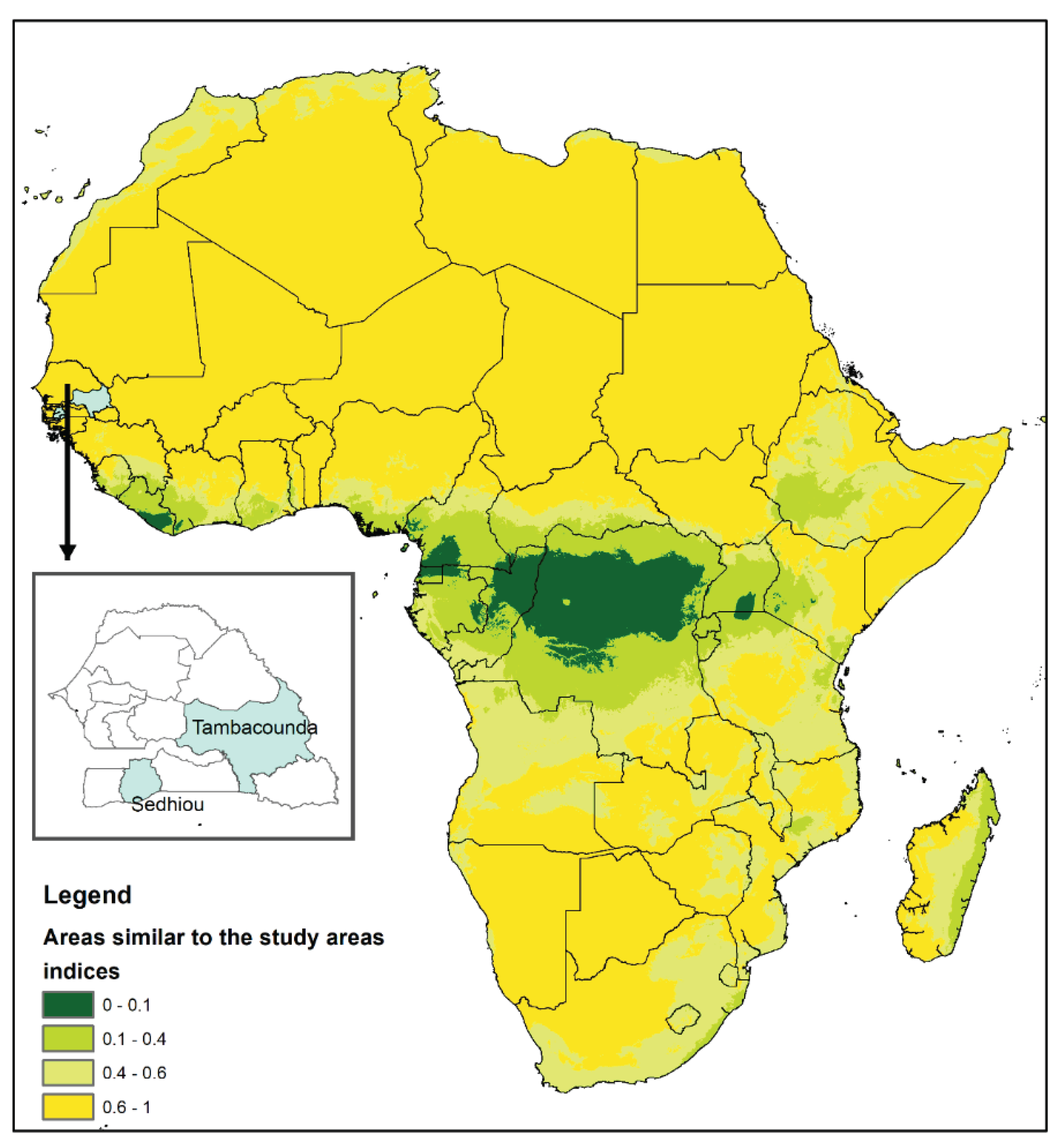

The review process followed a structured and replicable methodology which first employed K-means clustering to identify regions across Africa that exhibit similar climatic conditions to the Sahel areas of Sédhiou and Tambacounda. This analysis utilized bioclimatic variables obtained from WorldClim historical data [

26] to categorize regions based on climate similarity.

Following Rockström et al. [

27], the identified water-management technologies were classified into three categories of systems that: (i) Prolong the duration of soil-moisture availability in the soil, for example mulching practices; (ii) Promote infiltration of rainwater into the soil. These techniques include pitting, ridging/furrowing and terracing, or (iii) Store surface and sub-surface runoff water for later use, for example, rainwater harvesting systems with storage for supplementary irrigation [

28].

2.1. Clustering Approach and Justification

The study applied the widely used

K-means clustering algorithm to categorize regions across Africa exhibiting climatic conditions akin to the targeted Sahel areas and specifically Sédhiou and Tambacounda, due to its efficiency in handling large datasets and its ability to identify distinct groups based on proximity to cluster centroids [

29]. This method was deemed appropriate for:

The algorithm works by iteratively assigning data points to clusters based on their proximity to cluster centers and updating these centers [

31]. In this context, it helped identify areas in other countries that share similar climatic characteristics with the study areas, forming clusters of analogous conditions. To determine the

optimal number of clusters (k), the

Elbow Method was applied, evaluating within-cluster variance across different values of

k. The final model adopted a 60%

climate similarity threshold, determined via Geometric Interval classification, to account for non-normal distributions in bioclimatic variables, thus ensuring that only significantly comparable regions were selected.

K-means clustering facilitated a preliminary systematic exploration of sustainable land and water management practices, providing valuable insights into strategies for on-farm or off-farm rainwater harvesting and storage, which is particularly crucial during periods of drought and intense, short-duration rainfall that are associated with climate change.

2.2. Bioclimatic Variables

Table 1 presents the statistics of

bioclimatic variables used in clustering. These variables capture temperature and precipitation patterns, which are critical for assessing climatic similarity and rainwater management potential. The selection of bioclimatic variables (such as temperature seasonality (BIO4) and precipitation of the driest month (BIO14)) was guided by their relevance to water management in semi-arid regions. These variables capture critical aspects of climate variability that influence soil-moisture availability and rainwater-harvesting potential.

2.3. Regional Selection and Literature Review

This approach enabled researchers to pinpoint regions with analogous conditions, subsequently facilitating a comprehensive literature review on water-management technologies. The goal was to explore strategies for rainwater storage in the soil and rainwater harvesting that support crop growth through to maturity, particularly during droughts and intense, short-duration rainfall associated with climate change. By pinpointing regions with analogous climatic conditions, this study contributes to international research on climate adaptation and water-resource management. The findings offer a transferable framework for identifying areas where successful water-management strategies could be replicated, making them valuable for development organizations, farmers, policymakers, and researchers.

The clustering process identified

35 African countries with comparable climatic conditions (

Figure 1). However, only

17 countries (bolded in the list below), were included in the literature review due to lack of adequate literature (as shown in Table 2, at the end of the results section). The countries encompassed,

Botswana, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Angola, Benin, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Eritrea, Egypt, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea Bissau, Libya, Mauritania, Mozambique, Morocco, South Sudan, Togo, and Tunisia.

2.4. Review Methodology

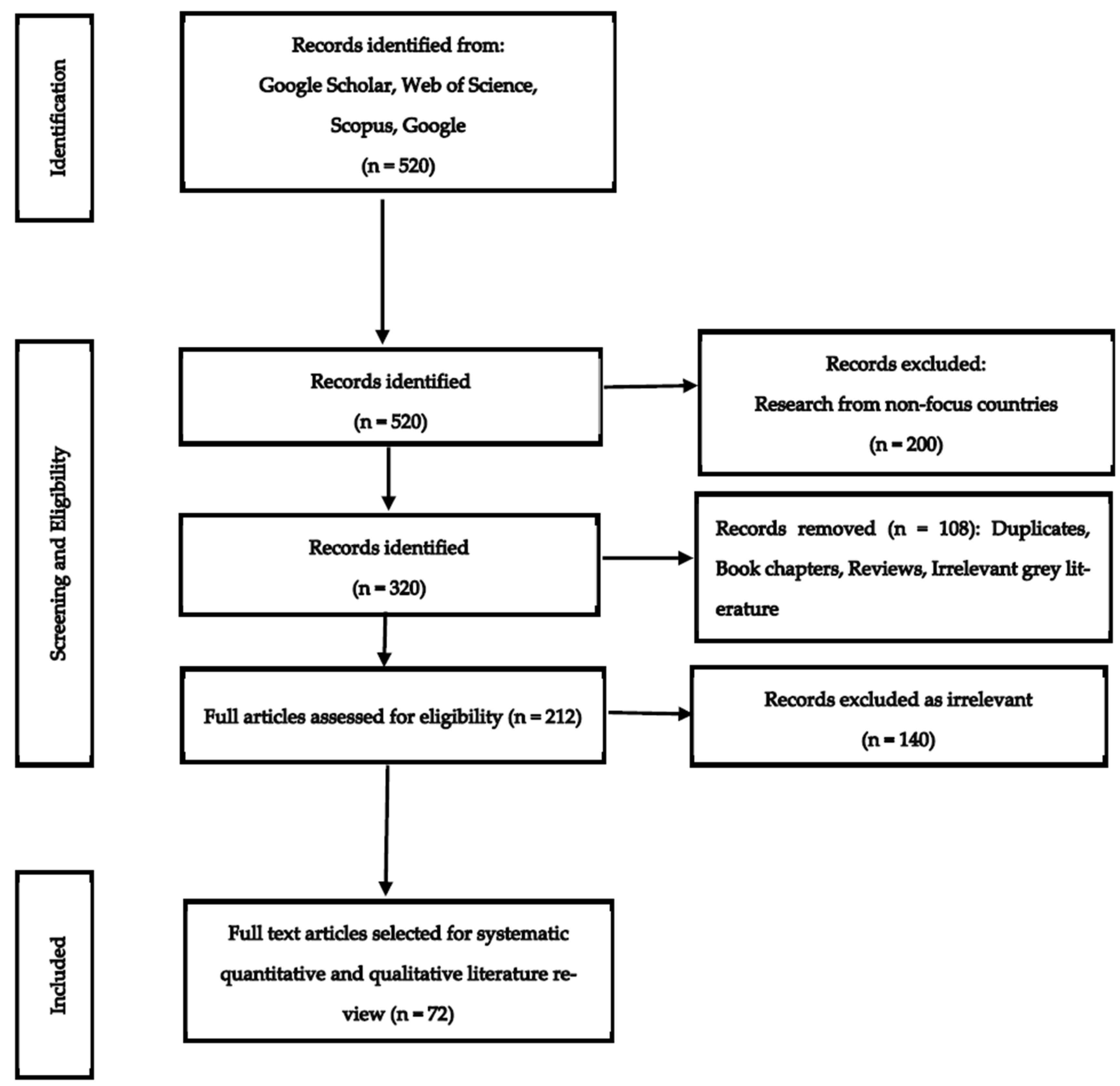

To achieve the research objective, we conducted a systematic analysis of peer-reviewed and published articles, technical reports, and working papers. The review followed the

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol as outlined by Moher et al. [

32]and Page et al. [

33] (Fig. 2). A comprehensive search was carried out across multiple platforms, including

Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google, using search strings that combined terms such as

“water management,” “soil and water management,” “sustainable land management,” “rainwater harvesting” with additional keywords like

“technologies,” “practices,” “arid regions,” “semi-arid Africa,” and country-specific identifiers (e.g.,

“Ethiopia,” “Kenya,” “Sahel”).

From an initial pool of approximately

520 documents,

200 documents were excluded because they contained research from countries that had not been selected from the pool of 17 after the country clustering process. From the remaining 320 documents, duplicates, book chapters, reviews, and irrelevant grey literature were removed (n = 108). The remaining

212 documents were screened based on title and abstract for relevance to water management technology adoption in semi-arid regions. At this stage,

140 studies were excluded as irrelevant. A final set of

72 articles were selected for detailed assessment (

Figure 2), and a total of 136 articles are cited in this paper.

Each study was analyzed to document the type of technology (e.g., in-situ/ex-situ water harvesting, soil-moisture conservation, efficient irrigation), its agroecological suitability (e.g., slope, rainfall, temperature), and the context and challenges of implementation. The review covered the period 2005–2023, ensuring that findings reflect current climatic realities and technological advances.

While this review focuses on the Sahel regions of Sédhiou and Tambacounda, the methodology is designed to be replicable in other semi-arid regions globally. For instance, the bioclimatic variables used in this analysis are universally applicable, and the clustering approach can be adapted to identify regions with similar climatic challenges in other parts of the world as any area of study. The water management strategies identified, such as rainwater harvesting and mulching, have been successfully implemented in semi-arid regions of Africa and could be adapted to other regions facing similar climatic pressures.

This methodology provides broader applicability beyond Sédhiou and Tambacounda by:

Identifying transferable water management strategies applicable to regions with similar climate profiles.

Enhancing climate adaptation frameworks by linking findings to global agricultural resilience policies (FAO, UNDP).

Providing a replicable model for future studies assessing climate-adaptation-based agricultural interventions in semi-arid regions worldwide.

This study contributes to advancing the field by addressing the critical gap in the adoption of land and water management technologies in Senegal. By leveraging K-means clustering to identify comparable climatic regions and conducting a systematic literature review, this study introduces a data-driven approach to technology transfer. The findings provide a scientifically grounded framework for farmers, policymakers and development practitioners to adopt proven water management strategies, ensuring that innovations are tailored to the specific needs of Senegalese farmers. In doing so, this study aligns with international research efforts on climate adaptation, land management, and sustainable agriculture, reinforcing the global discourse on improving agricultural resilience in semi-arid regions.

Compiling Water Management and Conservation Technologies Across the Selected Countries

A comprehensive collection of water conservation and management technologies as implemented in various African countries, was compiled and organized on a country-by-country basis into tables after sorting them into, in-situ and ex-situ water harvesting, soil-moisture management and efficient irrigation techniques (

Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3,

Table A4 and

Table A5, fully listed in the supplementary material in the Appendix).

The technologies were further analyzed in the context of Senegal’s land gradient (Table 3). This assessment was crucial to prioritizing feasible technologies, by identifying the best-suited technologies for Senegal’s topography and to ensure that the technologies align with local farming practices and socio-economic conditions, increasing their practicality and acceptance by farmers. Slope suitability is a critical factor for successfully implementing most soil and water conservation measures. Each technology has specific slope thresholds, influencing its effectiveness and minimizing risks like erosion or inefficiency.

4. Discussion

The adoption of land- and water-management technologies across sub-Saharan Africa is uneven, with notable regional differences driven by agroecological suitability, institutional support, and socio-economic conditions [

113].

The results show that West African countries like Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have made considerable strides in the uptake of practices such as half-moons, stone bunds, and

Zai pits. This success can be attributed to decades of implementation by NGOs, and participatory projects that have aligned technologies with traditional farming systems [

114].

Zai is a traditional rehabilitation technique that was developed in the early 1960s by farmers in northern Burkina Faso to restore their damaged land, deal with drought, and retain soil-moisture [

115] while half-moons originated from the Sahel in the 1980s, in West Africa. Therefore, the two technologies are common in the Sahel, and hence their great uptake in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. In contrast, despite its similar climatic conditions Senegal has demonstrated relatively lower uptake of these technologies [

116]. This lag may be due to institutional weaknesses, limited funding, and a lack of integrated policy strategies tailored to dryland agriculture particularly among farmers who have not been exposed to government, development and NGO programs [

117]. In East Africa, countries like Ethiopia and Kenya lead in adopting agroforestry, terracing, and water harvesting, due to strong government programs and land-restoration incentives. This is coupled with collaborations between government agencies and NGOs [

118]. Southern Africa has shown preference for conservation agriculture and cover crops, with support from national research institutions and regional policy harmonization [

119]. This cross-country synthesis shows that successful technology adoption is not just a function of environmental necessity, but of institutional readiness, community involvement, and sustained policy investment.

Policy frameworks and institutional strength are crucial in shaping the diffusion and sustainability of land and water management technologies [

120]. In countries like Kenya, where land-tenure systems are more secure and supported by decentralization policies, farmers are more willing to invest labor and resources in long-term land improvements [

121]. Additionally, extension services and farmer training programs, especially those provided by community cooperatives and field schools, raise awareness and boost adoption rates. [

122]. The review underscores the importance of enabling environments for successful implementation. For example, Ethiopia’s widespread adoption of soil and water conservation practices is facilitated by integrated watershed-management policies and active government involvement [

123]. Conversely, Senegal's lower adoption can be linked to fragmented institutional roles and inconsistent policy incentives for sustainable agriculture [

124]. Awareness-raising mechanisms, such as demonstration plots, local champions, and community-based resource groups, have played a significant role in improving technology uptake in Kenya, Malawi, and Tanzania [

125].

Land- and water-management technologies carry important economic and social implications [

126]. Technologies such as

Zai pits and terracing, while effective, often demand substantial labor inputs and upfront costs, limiting accessibility for resource-constrained farmers [

127]. Economic evaluations are rarely reported, but the results suggest that smallholders prioritize practices that show clear, short-term benefits, with minimal additional financial burden [

128]. Gender dimensions are also critical [

128], but under-researched and under-reported. Access to land, extension services, and credit significantly influence adoption [

129], and women often face systemic barriers in all three [

130]. Technologies that are labor-intensive or require land tenure security tend to exclude women unless tailored support is provided [

131]. Youth engagement remains a largely unexplored frontier. With increasing rural youth unemployment, promoting technologies that are mechanized, entrepreneurial, or digitally supported could create new entry points for youth involvement. However, current literature lacks robust analysis on how land and water technologies affect or are adopted by young farmers. These gaps indicate a need for gender-responsive and youth-inclusive research and programming to ensure equitable access and impact.

This review identifies several limitations in the current body of research. First, there is a lack of long-term trials that assess how soil- and water-management technologies perform over multiple years under changing climate conditions [

132]. Second, the economic dimensions of technology adoption are rarely analyzed in depth [

133]. Yield gains are commonly reported, but data on labor costs, return on investment, and financial barriers are scarce. Without this, it is difficult to assess feasibility or incentivize scaling. Third, there is an absence of gender-disaggregated and youth-specific data [

134]. Although women and youth play critical roles in agriculture, few studies explore how these groups interact with land- and water technologies or benefit from them. This lack of inclusivity weakens the evidence base for equitable development strategies. Finally, many technologies are assumed to be transferable across contexts without thorough testing. Technologies that are effective in one region may underperform elsewhere due to differences in community norms, institutions, soils, or topography [

135]. This assumption of universality may reduce the effectiveness of technologies and reduce uptake.

To ensure that land- and water-management technologies are effective, inclusive, and scalable, future research should focus on several areas to benefit smallholder farmers across Africa’s drylands. First, there is a critical need for long-term impact assessments. Lack of long-term trials limits understanding of the durability of sustainable land-management technologies under prolonged drought, soil stress, or changing climate. Future studies should therefore track soil health, water retention, yield stability, and farmer satisfaction over multiple seasons and under variable weather and land-use conditions. This will help smallholder farmers manage risk and plan better for the future. In addition, studying the economic viability of these technologies is equally important. This will help smallholder farmers to make decisions regarding the most promising technology investment options. Inadequate finance to cover labor and input cost make smallholder farmers reluctant to adopt even these promising technologies. Therefore, future studies should include simple cost-benefit analyses, developed in partnership with farmers, to identify technologies with the best returns on investment. This will enable farmers to minimize risks and enhance access to microfinance or subsidies according to their profitability.

Disaggregated research on gender and youth is also crucial. Despite their significant contributions in agriculture, women and youth are frequently excluded from innovation and adoption pathways. Women face structural barriers such as insecure land tenure and limited access to information and tools [

134], while youths have limited access to land, or find agriculture unattractive [

136]. Future research must explore how land- and water technologies can be adapted to meet the specific needs of these groups. Doing so would ensure that more people benefit from sustainable practices, reduce inequality within farming communities, and build intergenerational interest in land management.

Additionally, future studies can assess and validate the adaptability of the diverse soil and water management practices in different locations. Technologies that are successful in one agroecological zone or region might not be effective in another. Soil type, rainfall variability, cultural preferences, and institutional environments differ greatly across the Sahel and sub-Saharan Africa. Evaluating and customizing technology to suit certain local conditions, prior to widespread promotion will save resource wastage and dissatisfaction. For farmers, this would require recommendations that are tailored to their field conditions and landscapes.

There is also a need to effectively integrate Indigenous and local knowledge into research and activities. This is because small-scale farmers across Africa have acquired generations of knowledge in managing scarce water, maintaining soil fertility, and coping with climate extremes. Investing in participatory research would enhance and improve current practices in addition to documenting local knowledge. This can promote cultural relevance, improve farmer ownership, and facilitate the adoption of new initiatives.

Finally, to engage the young generation and assist smallholder decision-making, there is a need to explore digital tools and rural innovations. These include using mobile phones and low-cost weather and soil sensors, which have become increasingly accessible. These can provide real-time guidance on where to access inputs, how to control runoff, and when to plant. Similarly, digital input supply agribusiness models involving water-harvesting and irrigation kits, or leasing farm equipment, can create opportunities for youth and local entrepreneurs. For smallholder farmers, digital and entrepreneurial innovations offer not only better access to information but also new income streams through job creation. These prospective research avenues promise to convert land- and water management from fragmented technical solutions into farmer-centric, contextually relevant techniques that enhance livelihoods, equality, and resilience within dryland agricultural systems.

Selection of Technologies for Adoption in Sédhiou and Tambacounda

Senegal has largely flat terrain, with the highest point being Baunez ridge situated 2.7km southeast of Nepen Diakha at 648m. Tambacounda lies at an elevation of 24m while Sédhiou lies at 33m. Therefore, adoption of soil- and water-management technologies needs to take slope into consideration, for more feasibility. Considering that most agricultural fields lie between a slope of 0 and 10%, the recommended technologies would include: agroforestry, deep ripping, drip irrigation, half-moons, infiltration pits, manure application, minimum tillage, mulching, residual moisture, road runoff water harvesting into pans and ponds, tied ridges, trash lines, water pans, and Zai/Tassa pits.

5. Conclusions

This review presents a synthesis of around 85 land- and water-management technologies implemented across 17 climate-analogous countries in sub-Saharan Africa, identified using K-means clustering based on bioclimatic variables. The technologies reviewed offer substantial potential for improving resilience and productivity in Senegal’s semi-arid zones, particularly Sédhiou and Tambacounda. These areas face declining yields, water stress, and land degradation which are challenges that demand site-appropriate, scalable solutions.

Despite the development of numerous effective soil- and water-conservation techniques across Africa, their adoption in the Sahel—and particularly in Senegal—remains limited due to weak institutional, financial, and political support, coupled with inadequate extension and monitoring systems [

22]. Scaling these technologies is further constrained by insufficient financing and capacity within civil society, local authorities, and the private sector. Yet appropriate water management is essential for achieving optimal economic growth, food security, poverty reduction, climate resilience, biodiversity conservation, and sustainable agriculture. The review underscores that success depends not only on technology but also on systems that foster local ownership, stakeholder participation, and context-specific design. In arid regions, water management is as much a social and economic imperative as a technical one, requiring farmer empowerment, capacity building, and inclusive approaches for youth and women. Proven practices such as half-moons, mulching, rainwater harvesting into pans and ponds, trash lines, and

Zai pits are especially well-suited to Sédhiou and Tambacounda’s terrain. Evidence from cross-country experiences shows that adoption is strongest where awareness, funding, institutions, and policies converge, highlighting the need for integrated strategies to translate technologies into lasting resilience.

Unlocking the full potential of soil- and water-conservation technologies requires governments and development partners to invest in knowledge transfer, demonstration sites, and cross-country learning platforms, while embedding conservation into multisectoral policies, increasing local financing, and ensuring inclusive participation of women, youth, and local leaders. Success depends on early and meaningful stakeholder engagement, which fosters ownership, integrates local knowledge, and enhances the appropriateness of decisions, even in contexts where mistrust or conflicts of interest often undermine adoption. Sustainable implementation also requires balancing economic, environmental, and social factors, and demonstrating both on-site and off-site benefits through an Integrated Water Resources Management approach. Strong policy support is pivotal, with governments shaping land-use decisions through legislation and regulations, while public education and improved knowledge-sharing mechanisms bridge gaps between science, policy, and practice. Without these measures, proven solutions risk remaining fragmented and failing to drive the agricultural transformation urgently needed in the Sahel.

Recommendations/Future Steps

Integration into multi-sectoral policy frameworks: Water management and conservation practices should be seamlessly integrated into multi-sectoral policy frameworks in the region. Given the inherently cross-sectoral nature of such projects, policy frameworks should reflect the interconnectedness of water management and conservation initiatives, from local to regional levels.

Adequate funding: To upscale water-management and -conservation practices, there is a critical need for both internal and external resource mobilization. Adequate funding should be secured to implement techniques and technologies beyond the capacities of local communities, including water-harvesting technologies, soil-fertility improvement techniques, afforestation, and forest management, as well as capacity-building initiatives.

Private-sector involvement: The advisory roles of technical services, especially the participation of the private sector, should be improved to bring on board more key stakeholders, promote scaling up and sustainability of the practices in the long term. This can be achieved through developing harmonized planning and the promotion of marketable goods and services derived from the implementation of Sustainable Land Management practices.

Empowering stakeholders: Soil and water conservation stakeholders should engage in careful planning to better conserve and use their soil and water resources. The ultimate goal is to empower farmers with the necessary tools and technical knowledge to effectively conserve these resources that will translate into improved agricultural productivity and livelihoods. Initiatives should be designed according to participatory and inclusive approaches that integrate ethnic, gender, and youth perspectives and knowledge.

Capacity building, research, education, and extension: Emphasis should be placed on regular research, education, and extension (training) focused on soil- and water-conservation technologies for stakeholders, especially farmers. Continuous learning, awareness building, and knowledge dissemination are essential for the successful implementation of these conservation practices.

Site-Specific Approaches: Soil- and water-conservation practices should be site-specific, considering the variations in soil types, crops, and climatic conditions among other factors, such as the technologies’ installation and maintenance costs across various ecological zones in the country. Tailoring interventions to specific contexts will enhance their effectiveness.

Government Involvement: Governments at all levels should be actively involved in providing technical support and incentives for improving land- and water-management practices. This involvement is crucial for minimizing land degradation and improving water quality, contributing to achieving relevant Sustainable Development Goals.

Arising from the review, the authors recommend that the technologies listed in table 5 below be considered for adoption in Sédhiou and Tambacounda, Senegal and the Sahel region:

Table 5.

Recommended land- and water-management technologies to boost Senegal's agricultural resilience.

Table 5.

Recommended land- and water-management technologies to boost Senegal's agricultural resilience.

| Management approach |

Technology |

| Efficient irrigation |

1 |

Drip irrigation |

| 2 |

Residual moisture irrigation |

| Soil-moisture management |

3 |

Agroforestry |

| 4 |

Deep ripping |

| 5 |

Manure application |

| 6 |

Minimum tillage |

| 7 |

Mulch application |

| 8 |

Trash lines |

| Water harvesting |

9 |

Constructing half-moons |

| 10 |

Constructing infiltration pits |

| 11 |

Road runoff water-harvesting into pans & ponds |

| 12 |

Establishing tied ridges |

| 13 |

Establishing Zai/Tassa pits |

This is mainly because Sédhiou and Tambacounda regions have a fairly undulating terrain which limits the application of most of the researched technologies, which are only applicable in areas with greater slopes.