Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

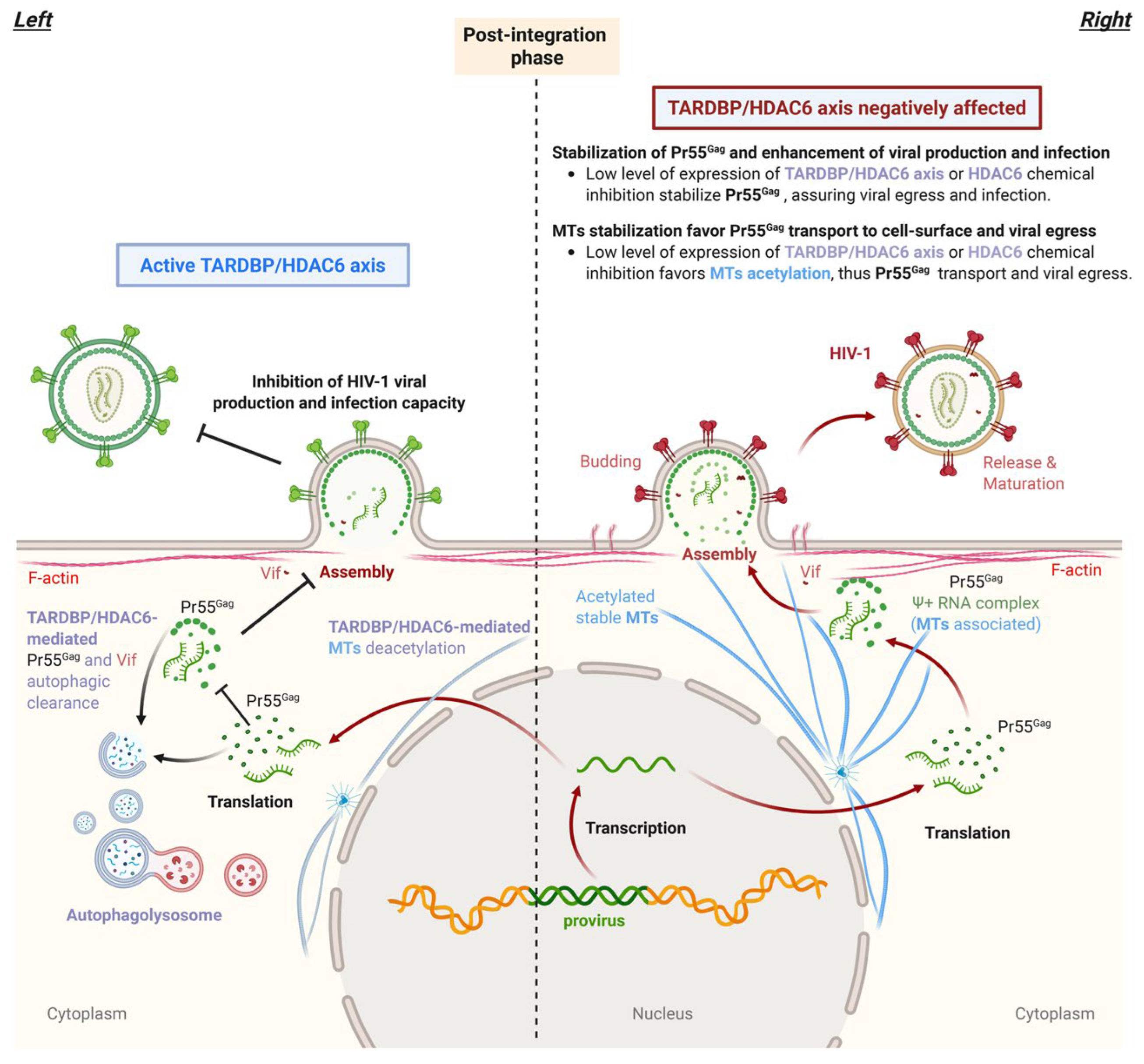

2. TARDBP Regulating Virion Formation and Infectiveness

A sentinel Against Pr55Gag Correct Processing and Virion Incompetence

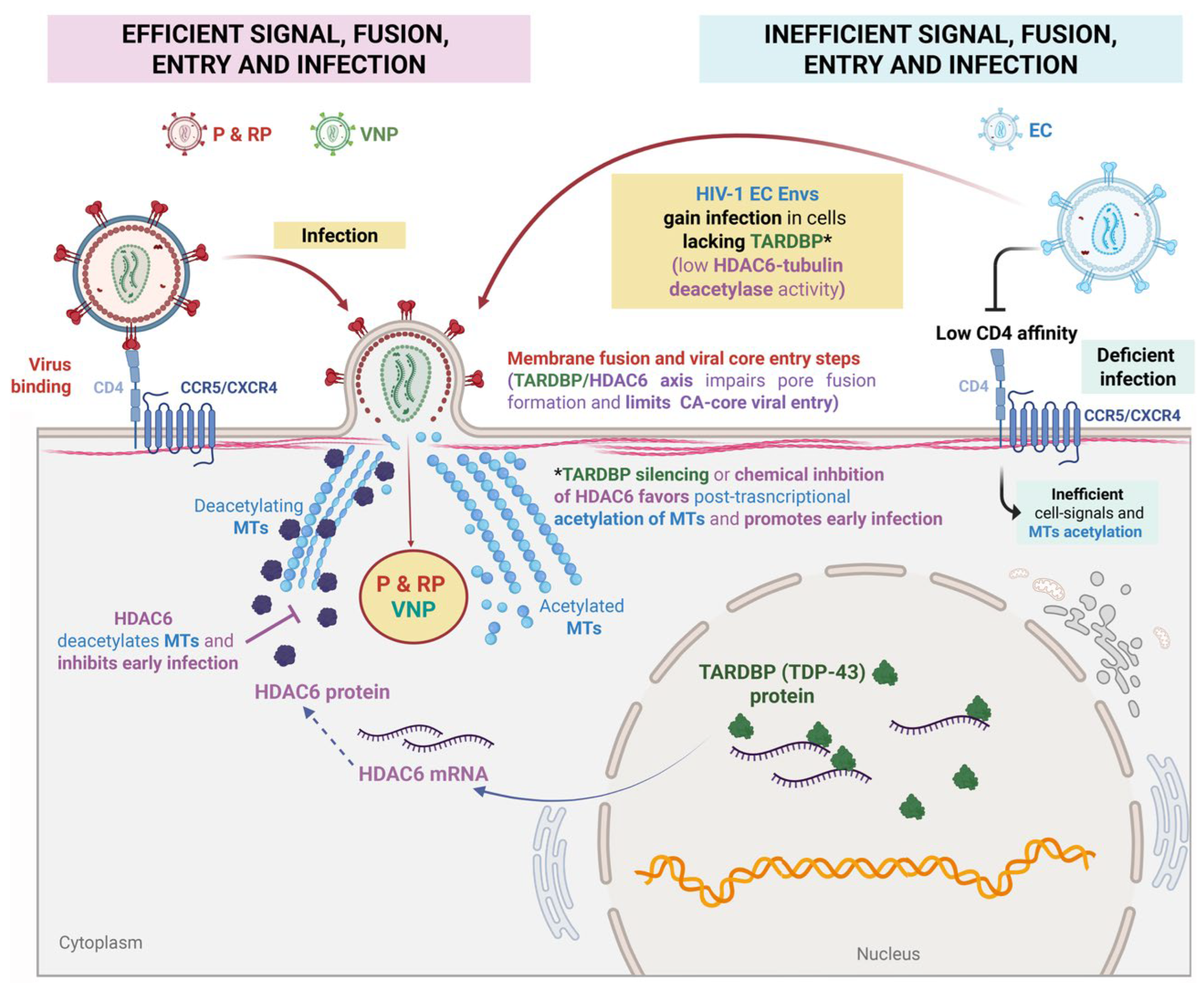

3. TARDBP at the Portal

Blocking Viral Core Entry and Early Infection via HDAC6 Regulation

4. Perspective

TARDBP as a Potential Clinical Target

5. Conclusions

Abbreviations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ganser-Pornillos BK, Cheng A, Yeager M: Structure of full-length HIV-1 CA: a model for the mature capsid lattice. Cell 2007, 131, 70–79. [CrossRef]

- Ganser BK, Li S, Klishko VY, Finch JT, Sundquist WI: Assembly and analysis of conical models for the HIV-1 core. Science 1999, 283, 80–83. [CrossRef]

- Zhao G, Perilla JR, Yufenyuy EL, Meng X, Chen B, Ning J, Ahn J, Gronenborn AM, Schulten K, Aiken C, Zhang P: Mature HIV-1 capsid structure by cryo-electron microscopy and all-atom molecular dynamics. Nature 2013, 497, 643–646. [CrossRef]

- Briggs JA, Simon MN, Gross I, Krausslich HG, Fuller SD, Vogt VM, Johnson MC: The stoichiometry of Gag protein in HIV-1. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2004, 11, 672–675. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Hill CP, Sundquist WI, Finch JT: Image reconstructions of helical assemblies of the HIV-1 CA protein. Nature 2000, 407, 409–413. [CrossRef]

- Campbell EM, Hope TJ: HIV-1 capsid: the multifaceted key player in HIV-1 infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 2015, 13, 471–483. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health and Human Services (Washington D: Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. HHS Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents—A Working Group of the NIH Office of AIDS Research Advisory Council (OARAC) 2024. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/guidelines-adult-adolescent-arv.pdf.

- Sever B, Otsuka M, Fujita M, Ciftci H: A Review of FDA-Approved Anti-HIV-1 Drugs, Anti-Gag Compounds, and Potential Strategies for HIV-1 Eradication. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25.

- Segal-Maurer S, DeJesus E, Stellbrink HJ, Castagna A, Richmond GJ, Sinclair GI, Siripassorn K, Ruane PJ, Berhe M, Wang H, et al. Capsid Inhibition with Lenacapavir in Multidrug-Resistant HIV-1 Infection. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 1793–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker LG, Das M, Abdool Karim Q, Ahmed K, Batting J, Brumskine W, Gill K, Harkoo I, Jaggernath M, Kigozi G, et al. Twice-Yearly Lenacapavir or Daily F/TAF for HIV Prevention in Cisgender Women. N Engl J Med 2024, 391, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link JO, Rhee MS, Tse WC, Zheng J, Somoza JR, Rowe W, Begley R, Chiu A, Mulato A, Hansen D, et al. Clinical targeting of HIV capsid protein with a long-acting small molecule. Nature 2020, 584, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekerman E, Yant SR, VanderVeen L, Hansen D, Lu B, Rowe W, Wang K, Callebaut C: Long-acting lenacapavir acts as an effective preexposure prophylaxis in a rectal SHIV challenge macaque model. J Clin Invest 2023, 133.

- Marcelin AG, Charpentier C, Jary A, Perrier M, Margot N, Callebaut C, Calvez V, Descamps D: Frequency of capsid substitutions associated with GS-6207 in vitro resistance in HIV-1 from antiretroviral-naive and -experienced patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020, 75, 1588–1590. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzinamarira T, Almehmadi M, Alsaiari AA, Allahyani M, Aljuaid A, Alsharif A, Khan A, Kamal M, Rabaan AA, Alfaraj AH, et al. Highlights on the Development, Related Patents, and Prospects of Lenacapavir: The First-in-Class HIV-1 Capsid Inhibitor for the Treatment of Multi-Drug-Resistant HIV-1 Infection. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock AM, Kufel WD, Dwyer KAM, Sidman EF: Lenacapavir: A novel injectable HIV-1 capsid inhibitor. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2024, 63, 107009. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian R, Tang J, Zheng J, Lu B, Wang K, Yant SR, Stepan GJ, Mulato A, Yu H, Schroeder S, et al. Lenacapavir: A Novel, Potent, and Selective First-in-Class Inhibitor of HIV-1 Capsid Function Exhibits Optimal Pharmacokinetic Properties for a Long-Acting Injectable Antiretroviral Agent. Mol Pharm 2023, 20, 6213–6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perron MJ, Stremlau M, Lee M, Javanbakht H, Song B, Sodroski J: The human TRIM5alpha restriction factor mediates accelerated uncoating of the N-tropic murine leukemia virus capsid. J Virol 2007, 81, 2138–2148. [CrossRef]

- Wagner JM, Roganowicz MD, Skorupka K, Alam SL, Christensen D, Doss G, Wan Y, Frank GA, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Sundquist WI, Pornillos O: Mechanism of B-box 2 domain-mediated higher-order assembly of the retroviral restriction factor TRIM5alpha. Elife 2016, 5.

- Wagner JM, Christensen DE, Bhattacharya A, Dawidziak DM, Roganowicz MD, Wan Y, Pumroy RA, Demeler B, Ivanov DN, Ganser-Pornillos BK, et al. General Model for Retroviral Capsid Pattern Recognition by TRIM5 Proteins. J Virol 2018, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Griffero F, Vandegraaff N, Li Y, McGee-Estrada K, Stremlau M, Welikala S, Si Z, Engelman A, Sodroski J: Requirements for capsid-binding and an effector function in TRIMCyp-mediated restriction of HIV-1. Virology 2006, 351, 404–419. [CrossRef]

- Li YL, Chandrasekaran V, Carter SD, Woodward CL, Christensen DE, Dryden KA, Pornillos O, Yeager M, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Jensen GJ, Sundquist WI: Primate TRIM5 proteins form hexagonal nets on HIV-1 capsids. Elife 2016, 5.

- Javanbakht H, Diaz-Griffero F, Yuan W, Yeung DF, Li X, Song B, Sodroski J: The ability of multimerized cyclophilin A to restrict retrovirus infection. Virology 2007, 367, 19–29. [CrossRef]

- Kutluay SB, Perez-Caballero D, Bieniasz PD: Fates of retroviral core components during unrestricted and TRIM5-restricted infection. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9, e1003214.

- Lukic Z, Hausmann S, Sebastian S, Rucci J, Sastri J, Robia SL, Luban J, Campbell EM: TRIM5alpha associates with proteasomal subunits in cells while in complex with HIV-1 virions. Retrovirology 2011, 8, 93. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielson CM, Cianci GC, Hope TJ: Recruitment and dynamics of proteasome association with rhTRIM5alpha cytoplasmic complexes during HIV-1 infection. Traffic 2012, 13, 1206–1217. [CrossRef]

- Danielson CM, Hope TJ: Using antiubiquitin antibodies to probe the ubiquitination state within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies.

- Roa A, Hayashi F, Yang Y, Lienlaf M, Zhou J, Shi J, Watanabe S, Kigawa T, Yokoyama S, Aiken C, Diaz-Griffero F: RING domain mutations uncouple TRIM5alpha restriction of HIV-1 from inhibition of reverse transcription and acceleration of uncoating. J Virol 2012, 86, 1717–1727. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher AJ, Christensen DE, Nelson C, Tan CP, Schaller T, Lehner PJ, Sundquist WI, Towers GJ: TRIM5alpha requires Ube2W to anchor Lys63-linked ubiquitin chains and restrict reverse transcription. EMBO J 2015, 34, 2078–2095. [CrossRef]

- Campbell EM, Weingart J, Sette P, Opp S, Sastri J, O’Connor SK, Talley S, Diaz-Griffero F, Hirsch V, Bouamr F: TRIM5α-Mediated Ubiquitin Chain Conjugation Is Required for Inhibition of HIV-1 Reverse Transcription and Capsid Destabilization.

- Rasaiyaah J, Tan CP, Fletcher AJ, Price AJ, Blondeau C, Hilditch L, Jacques DA, Selwood DL, James LC, Noursadeghi M, Towers GJ: HIV-1 evades innate immune recognition through specific cofactor recruitment. Nature 2013, 503, 402–405. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Caballero D, Hatziioannou T, Zhang F, Cowan S, Bieniasz PD: Restriction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by TRIM-CypA occurs with rapid kinetics and independently of cytoplasmic bodies, ubiquitin, and proteasome activity. J Virol 2005, 79, 15567–15572. [CrossRef]

- Wu X, Anderson JL, Campbell EM, Joseph AM, Hope TJ: Proteasome inhibitors uncouple rhesus TRIM5alpha restriction of HIV-1 reverse transcription and infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 7465–7470. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson JL, Campbell Em Fau - Wu X, Wu X Fau - Vandegraaff N, Vandegraaff N Fau - Engelman A, Engelman A Fau - Hope TJ, Hope TJ: Proteasome inhibition reveals that a functional preintegration complex intermediate can be generated during restriction by diverse TRIM5 proteins. 2006.

- O’Connor C, Pertel T, Gray S, Robia SL, Bakowska JC, Luban J, Campbell EM: p62/sequestosome-1 associates with and sustains the expression of retroviral restriction factor TRIM5alpha. J Virol 2010, 84, 5997–6006. [CrossRef]

- Mandell MA, Jain A, Arko-Mensah J, Chauhan S, Kimura T, Dinkins C, Silvestri G, Münch J, Kirchhoff F, Simonsen A, et al.: TRIM proteins regulate autophagy and can target autophagic substrates by direct recognition.

- Keown JR, Black MM, Ferron A, Yap M, Barnett MJ, Pearce FG, Stoye JP, Goldstone DC: A helical LC3-interacting region mediates the interaction between the retroviral restriction factor Trim5α and mammalian autophagy-related ATG8 proteins.

- Tanida I, Ueno T Fau - Kominami E, Kominami E: LC3 and Autophagy.

- Imam S, Talley S, Nelson RS, Dharan A, O’Connor C, Hope TJ, Campbell EM: TRIM5α Degradation via Autophagy Is Not Required for Retroviral Restriction.

- Cabrera-Rodriguez R, Perez-Yanes S, Lorenzo-Sanchez I, Estevez-Herrera J, Garcia-Luis J, Trujillo-Gonzalez R, Valenzuela-Fernandez A: TDP-43 Controls HIV-1 Viral Production and Virus Infectiveness. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24.

- Cabrera-Rodriguez R, Perez-Yanes S, Montelongo R, Lorenzo-Salazar JM, Estevez-Herrera J, Garcia-Luis J, Inigo-Campos A, Rubio-Rodriguez LA, Munoz-Barrera A, Trujillo-Gonzalez R, et al.: Transactive Response DNA-Binding Protein (TARDBP/TDP-43) Regulates Cell Permissivity to HIV-1 Infection by Acting on HDAC6. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23.

- Zeng J, Luo C, Jiang Y, Hu T, Lin B, Xie Y, Lan J, Miao J: Decoding TDP-43, the molecular chameleon of neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2024, 12, 205. [CrossRef]

- Brown AL, Wilkins OG, Keuss MJ, Hill SE, Zanovello M, Lee WC, Bampton A, Lee FCY, Masino L, Qi YA, et al. TDP-43 loss and ALS-risk SNPs drive mis-splicing and depletion of UNC13A. Nature 2022, 603, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buratti E, Baralle FE: The multiple roles of TDP-43 in pre-mRNA processing and gene expression regulation. RNA Biol 2010, 7, 420–429. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombrita C, Onesto E, Megiorni F, Pizzuti A, Baralle FE, Buratti E, Silani V, Ratti A: TDP-43 and FUS RNA-binding proteins bind distinct sets of cytoplasmic messenger RNAs and differently regulate their post-transcriptional fate in motoneuron-like cells. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 15635–15647. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tollervey JR, Curk T, Rogelj B, Briese M, Cereda M, Kayikci M, Konig J, Hortobagyi T, Nishimura AL, Zupunski V, et al. Characterizing the RNA targets and position-dependent splicing regulation by TDP-43. Nat Neurosci 2011, 14, 452–458. [Google Scholar]

- Polymenidou M, Lagier-Tourenne C, Hutt KR, Huelga SC, Moran J, Liang TY, Ling SC, Sun E, Wancewicz E, Mazur C, et al. Long pre-mRNA depletion and RNA missplicing contribute to neuronal vulnerability from loss of TDP-43. Nat Neurosci 2011, 14, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara Y, Mieda-Sato A: TDP-43 promotes microRNA biogenesis as a component of the Drosha and Dicer complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 3347–3352. [CrossRef]

- Highley JR, Kirby J, Jansweijer JA, Webb PS, Hewamadduma CA, Heath PR, Higginbottom A, Raman R, Ferraiuolo L, Cooper-Knock J, et al. Loss of nuclear TDP-43 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) causes altered expression of splicing machinery and widespread dysregulation of RNA splicing in motor neurones. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2014, 40, 670–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma X, Ying Y, Xie H, Liu X, Wang X, Li J: The Regulatory Role of RNA Metabolism Regulator TDP-43 in Human Cancer. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 755096. [CrossRef]

- Ma XA-O, Prudencio MA-O, Koike YA-O, Vatsavayai SC, Kim GA-O, Harbinski F, Briner AA-O, Rodriguez CM, Guo C, Akiyama TA-O, et al.: TDP-43 represses cryptic exon inclusion in the FTD-ALS gene UNC13A.

- Sephton CF, Cenik C, Kucukural A, Dammer EB, Cenik B, Han Y, Dewey CM, Roth FP, Herz J, Peng J, et al. Identification of neuronal RNA targets of TDP-43-containing ribonucleoprotein complexes. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 1204–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiesel FC, Voigt A, Weber SS, Van den Haute C, Waldenmaier A, Gorner K, Walter M, Anderson ML, Kern JV, Rasse TM, et al. Knockdown of transactive response DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) downregulates histone deacetylase 6. EMBO J 2010, 29, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbert C, Guardiola A, Shao R, Kawaguchi Y, Ito A, Nixon A, Yoshida M, Wang XF, Yao TP: HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase. Nature 2002, 417, 455–458. [CrossRef]

- Zilberman Y, Ballestrem C, Carramusa L, Mazitschek R, Khochbin S, Bershadsky A: Regulation of microtubule dynamics by inhibition of the tubulin deacetylase HDAC6. J Cell Sci 2009, 122, 3531–3541. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casado C, Marrero-Hernandez S, Marquez-Arce D, Pernas M, Marfil S, Borras-Granana F, Olivares I, Cabrera-Rodriguez R, Valera MS, de Armas-Rillo L, et al. Viral Characteristics Associated with the Clinical Nonprogressor Phenotype Are Inherited by Viruses from a Cluster of HIV-1 Elite Controllers. mBio 2018, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Yanes S, Pernas M, Marfil S, Cabrera-Rodríguez R, Ortiz R, Urrea V, Rovirosa C, Estévez-Herrera J, Olivares I, Casado C, et al. The Characteristics of the HIV-1 Env Glycoprotein Are Linked With Viral Pathogenesis. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela-Fernandez A, Alvarez S, Gordon-Alonso M, Barrero M, Ursa A, Cabrero JR, Fernandez G, Naranjo-Suarez S, Yanez-Mo M, Serrador JM, et al. Histone deacetylase 6 regulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Mol Biol Cell 2005, 16, 5445–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Fernandez A, Cabrero JR, Serrador JM, Sanchez-Madrid F: HDAC6, a key regulator of cytoskeleton, cell migration and cell-cell interactions. Trends Cell Biol 2008, 18, 291–297. [CrossRef]

- Ling L, Hu F, Ying X, Ge J, Wang Q: HDAC6 inhibition disrupts maturational progression and meiotic apparatus assembly in mouse oocytes. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 550–556. [CrossRef]

- Osseni A, Ravel-Chapuis A, Thomas JL, Gache V, Schaeffer L, Jasmin BJ: HDAC6 regulates microtubule stability and clustering of AChRs at neuromuscular junctions. J Cell Biol 2020, 219.

- Bershadsky AD, Ballestrem C, Carramusa L, Zilberman Y, Gilquin B, Khochbin S, Alexandrova AY, Verkhovsky AB, Shemesh T, Kozlov MM: Assembly and mechanosensory function of focal adhesions: experiments and models. Eur J Cell Biol 2006, 85, 165–173. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-Rodriguez R, Hebmann V, Marfil S, Pernas M, Marrero-Hernandez S, Cabrera C, Urrea V, Casado C, Olivares I, Marquez-Arce D, et al. HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins isolated from Viremic Non-Progressor individuals are fully functional and cytopathic. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik J: Lenacapavir: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 1499–1504. [CrossRef]

- Ma XR, Prudencio M, Koike Y, Vatsavayai SC, Kim G, Harbinski F, Briner A, Rodriguez CM, Guo C, Akiyama T, et al. TDP-43 represses cryptic exon inclusion in the FTD-ALS gene UNC13A. Nature 2022, 603, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera MS, de Armas-Rillo L, Barroso-Gonzalez J, Ziglio S, Batisse J, Dubois N, Marrero-Hernandez S, Borel S, Garcia-Exposito L, Biard-Piechaczyk M, et al. The HDAC6/APOBEC3G complex regulates HIV-1 infectiveness by inducing Vif autophagic degradation. Retrovirology 2015, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jager S, Kim DY, Hultquist JF, Shindo K, LaRue RS, Kwon E, Li M, Anderson BD, Yen L, Stanley D, et al. Vif hijacks CBF-beta to degrade APOBEC3G and promote HIV-1 infection. Nature 2011, 481, 371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Kim DY, Kwon E, Hartley PD, Crosby DC, Mann S, Krogan NJ, Gross JD: CBFbeta stabilizes HIV Vif to counteract APOBEC3 at the expense of RUNX1 target gene expression. Mol Cell 2013, 49, 632–644. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X, Han X, Zhao K, Du J, Evans SL, Wang H, Li P, Zheng W, Rui Y, Kang J, Yu XF: Dispersed and conserved hydrophobic residues of HIV-1 Vif are essential for CBFbeta recruitment and A3G suppression. J Virol 2014, 88, 2555–2563. [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi Y, Kovacs JJ, McLaurin A, Vance JM, Ito A, Yao TP: The deacetylase HDAC6 regulates aggresome formation and cell viability in response to misfolded protein stress. Cell 2003, 115, 727–738. [CrossRef]

- Seigneurin-Berny D, Verdel A Fau - Curtet S, Curtet S Fau - Lemercier C, Lemercier C Fau - Garin J, Garin J Fau - Rousseaux S, Rousseaux S Fau - Khochbin S, Khochbin S: Identification of components of the murine histone deacetylase 6 complex: link between acetylation and ubiquitination signaling pathways.

- Hook SS, Orian A Fau - Cowley SM, Cowley Sm Fau - Eisenman RN, Eisenman RN: Histone deacetylase 6 binds polyubiquitin through its zinc finger (PAZ domain) and copurifies with deubiquitinating enzymes.

- Marrero-Hernandez S, Marquez-Arce D, Cabrera-Rodriguez R, Estevez-Herrera J, Perez-Yanes S, Barroso-Gonzalez J, Madrid R, Machado JD, Blanco J, Valenzuela-Fernandez A: HIV-1 Nef Targets HDAC6 to Assure Viral Production and Virus Infection. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 2437.

- Cabrera-Rodriguez R, Perez-Yanes S, Lorenzo-Sanchez I, Trujillo-Gonzalez R, Estevez-Herrera J, Garcia-Luis J, Valenzuela-Fernandez A: HIV Infection: Shaping the Complex, Dynamic, and Interconnected Network of the Cytoskeleton. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24.

- Ward AB, Wilson IA: Insights into the trimeric HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein structure.

- Ward AB, Wilson IA: The HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein structure: nailing down a moving target.

- Simoes-Pires C, Zwick V, Nurisso A, Schenker E, Carrupt PA, Cuendet M: HDAC6 as a target for neurodegenerative diseases: what makes it different from the other HDACs? Mol Neurodegener 2013, 8, 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao J, Wang L, Huntley ML, Perry G, Wang X: Pathomechanisms of TDP-43 in neurodegeneration. J Neurochem 2018.

- Guo W, Van Den Bosch L: Therapeutic potential of HDAC6 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cell Stress 2017, 2, 14–16.

- Odagiri S, Tanji K, Mori F, Miki Y, Kakita A, Takahashi H, Wakabayashi K: Brain expression level and activity of HDAC6 protein in neurodegenerative dementia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013, 430, 394–399. [CrossRef]

- Lemos M, Stefanova N: Histone Deacetylase 6 and the Disease Mechanisms of alpha-Synucleinopathies. Front Synaptic Neurosci 2020, 12, 586453. [CrossRef]

- Trzeciakiewicz H, Ajit D, Tseng JH, Chen Y, Ajit A, Tabassum Z, Lobrovich R, Peterson C, Riddick NV, Itano MS, et al. An HDAC6-dependent surveillance mechanism suppresses tau-mediated neurodegeneration and cognitive decline. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cykowski MD, Powell SZ, Peterson LE, Appel JW, Rivera AL, Takei H, Chang E, Appel SH: Clinical Significance of TDP-43 Neuropathology in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2017, 76, 402–413. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong LK, Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ: TDP-43 proteinopathy: the neuropathology underlying major forms of sporadic and familial frontotemporal lobar degeneration and motor neuron disease. Acta Neuropathol 2007, 114, 63–70. [CrossRef]

- Wenzel ED, Speidell A, Flowers SA, Wu C, Avdoshina V, Mocchetti I: Histone deacetylase 6 inhibition rescues axonal transport impairments and prevents the neurotoxicity of HIV-1 envelope protein gp120. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 674. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Yanes S, Lorenzo-Sánchez I, Cabrera-Rodríguez RA-O, García-Luis JA-O, Trujillo-González RA-O, Estévez-Herrera J, Valenzuela-Fernández AA-O: The ZIKV NS5 Protein Aberrantly Alters the Tubulin Cytoskeleton, Induces the Accumulation of Autophagic p62 and Affects IFN Production: HDAC6 Has Emerged as an Anti-NS5/ZIKV Factor. LID - 10.3390/cells13070598 [doi] LID - 598. [CrossRef]

- Bartholomeeusen K, Fujinaga K, Xiang Y, Peterlin BM: Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) that release the positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb) from its inhibitory complex also activate HIV transcription.

- Cabrera-Rodriguez R, Perez-Yanes S, Estevez-Herrera J, Marquez-Arce D, Cabrera C, Espert L, Blanco J, Valenzuela-Fernandez A: The Interplay of HIV and Autophagy in Early Infection. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 661446.

- Lanman T, Letendre S, Ma Q, Bang A, Ellis R: CNS Neurotoxicity of Antiretrovirals. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2021, 16, 130–143. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson LJ, Reoma LB, Kovacs JA, Nath A: Advances toward Curing HIV-1 Infection in Tissue Reservoirs. J Virol 2020, 94.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).