Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Anatomy of the Human Eye

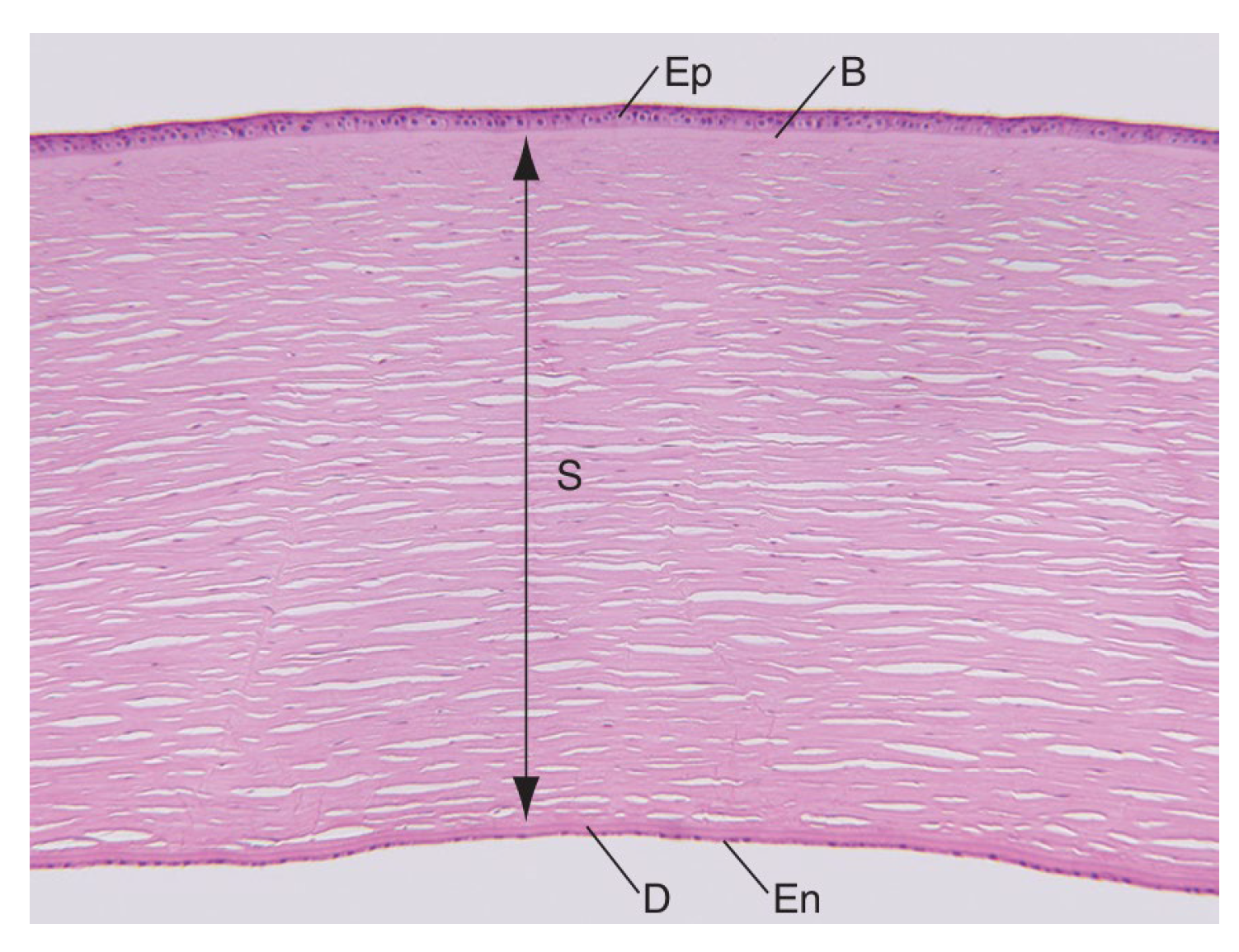

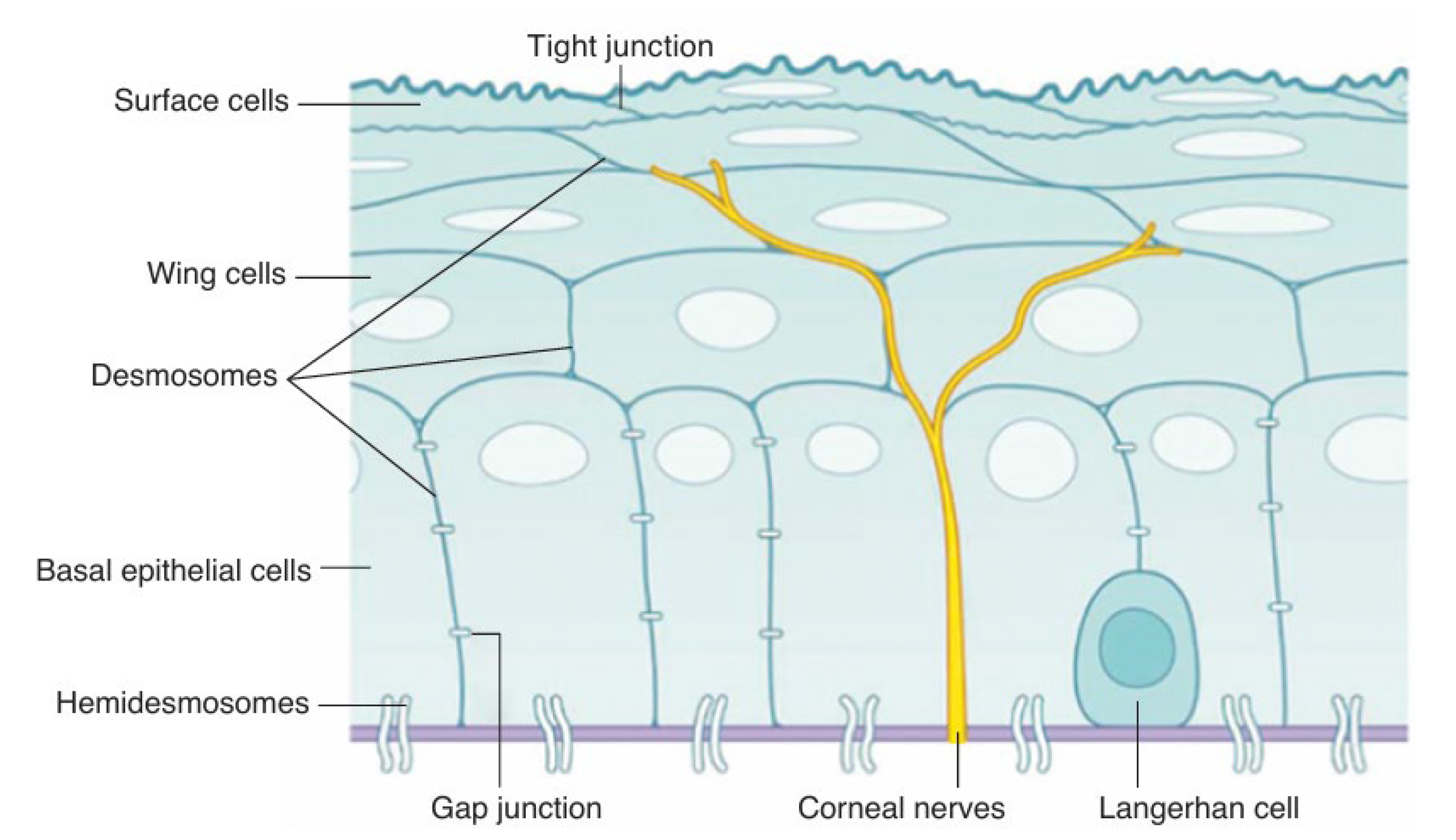

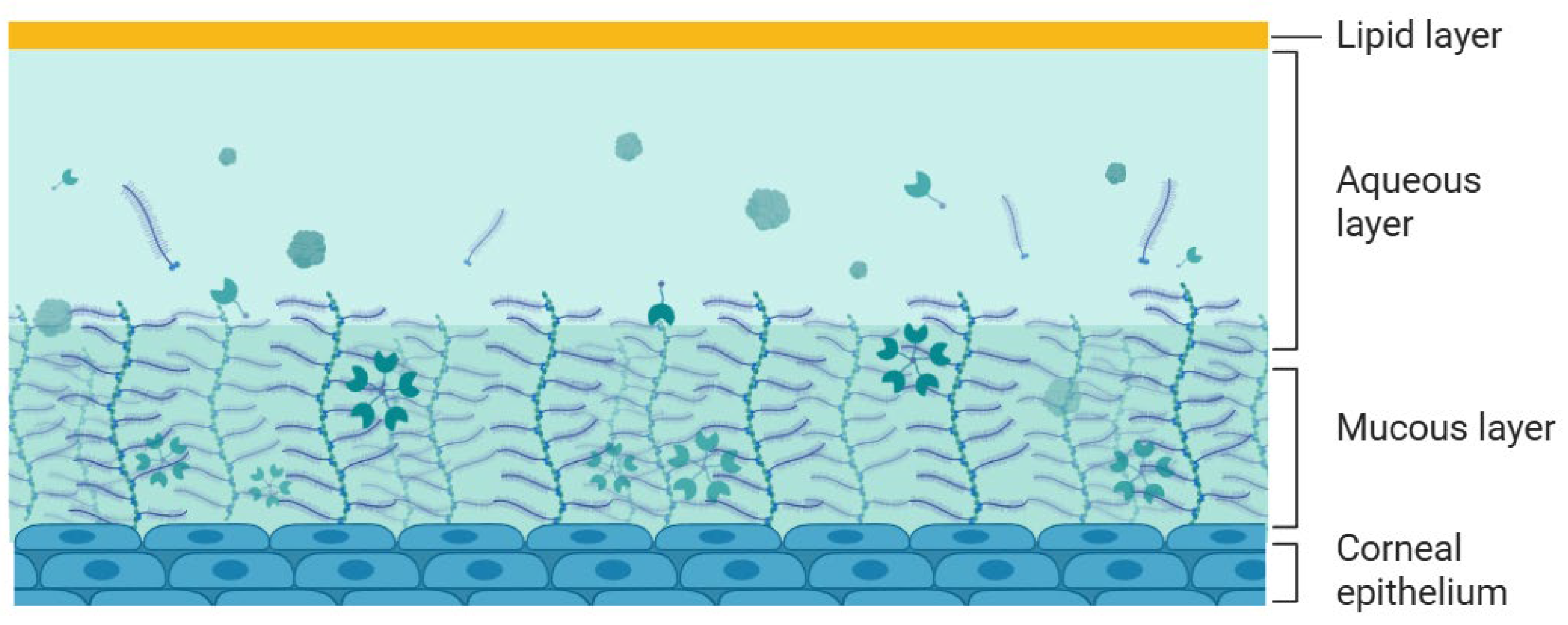

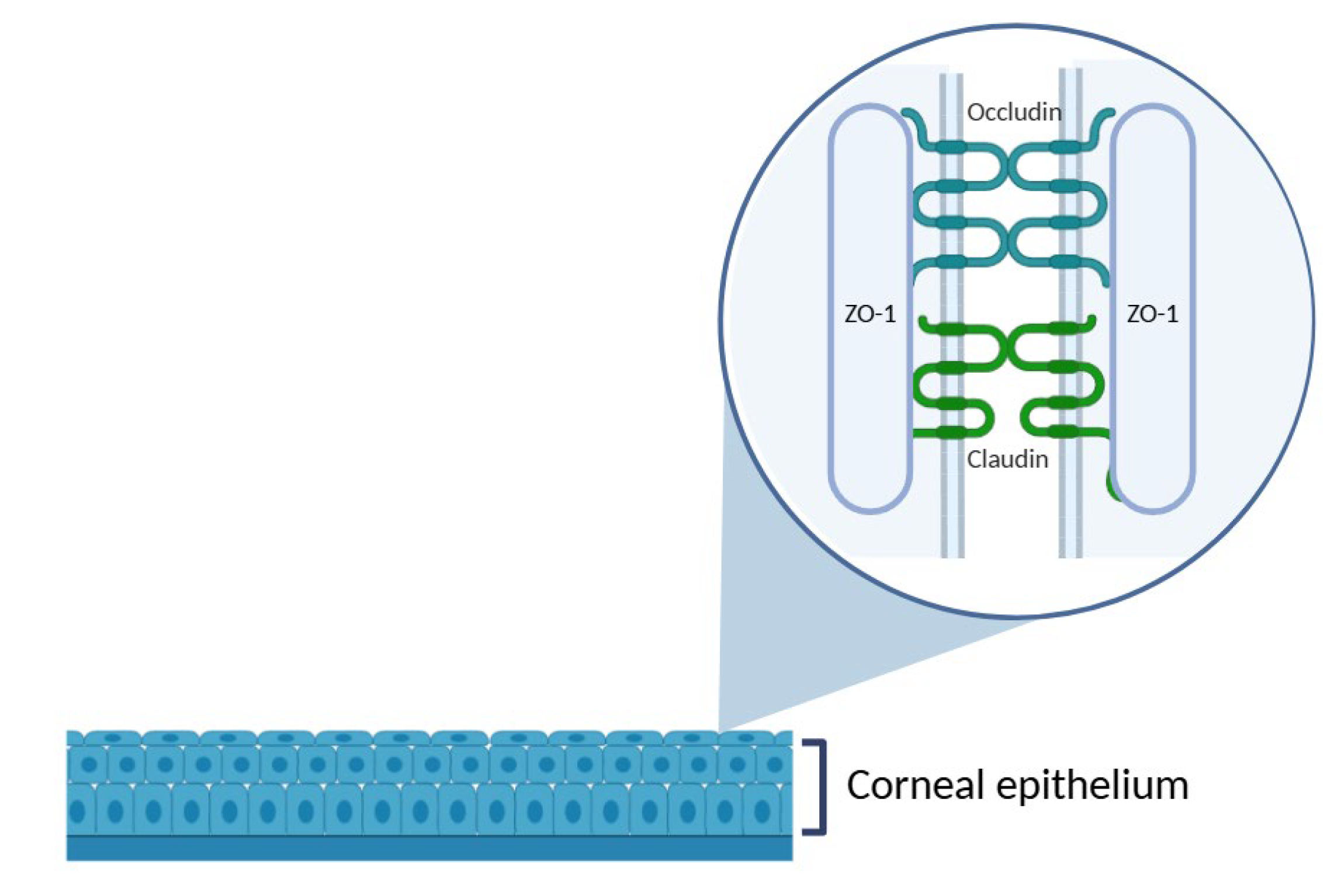

1.1. Cornea

1.2. Ocular Barriers

2. Experimental Models in Corneal Research

2.1. In Vitro, Ex Vivo, In Vivo Corneal Models

2.2. Porcine Corneal Models

3. Current Methodologies

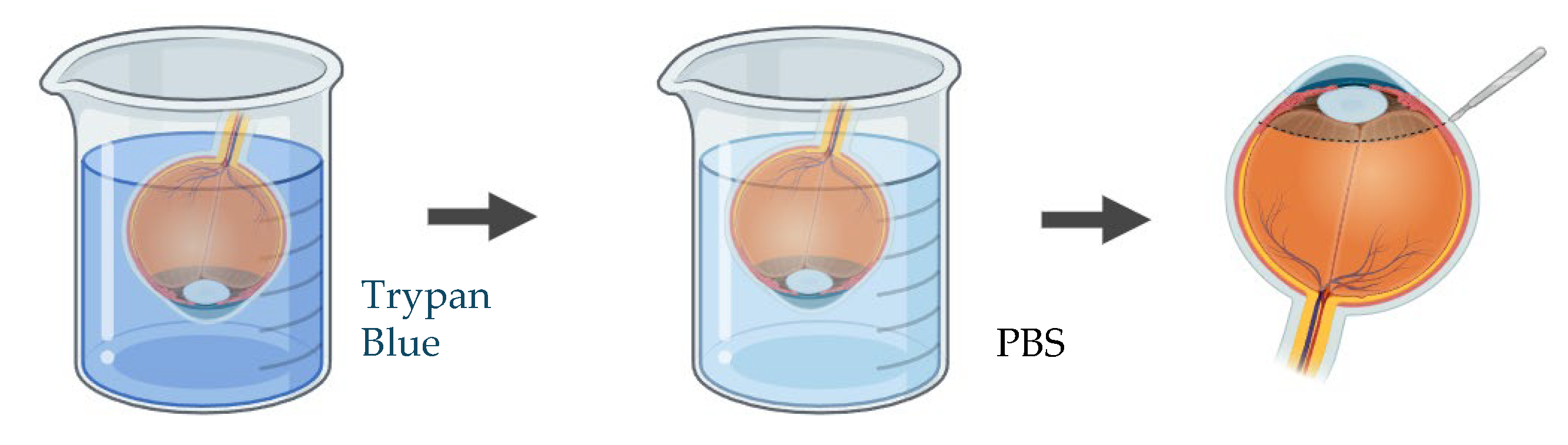

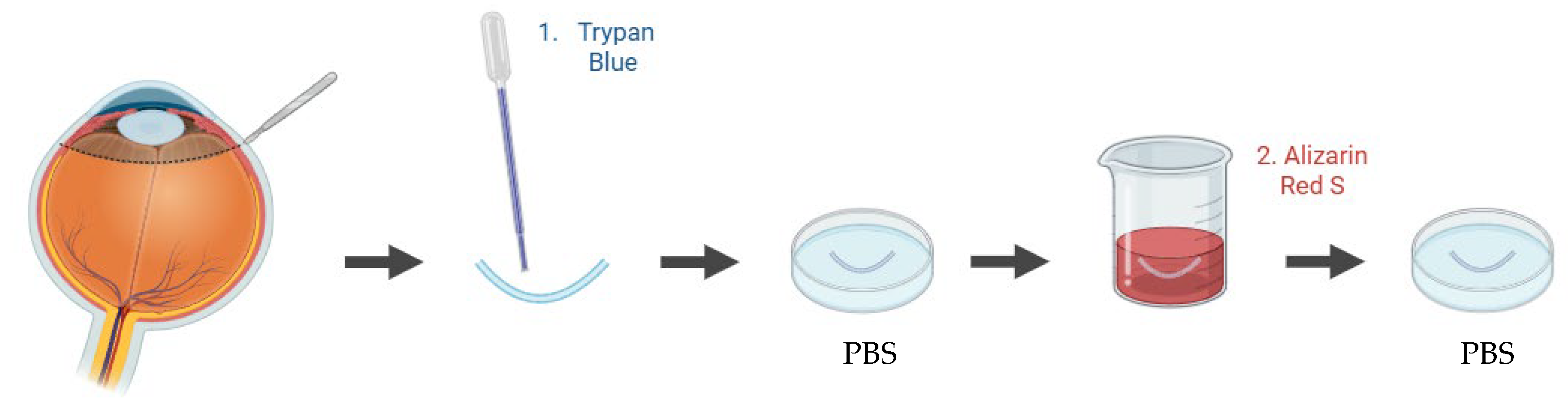

3.1. Cell Viability

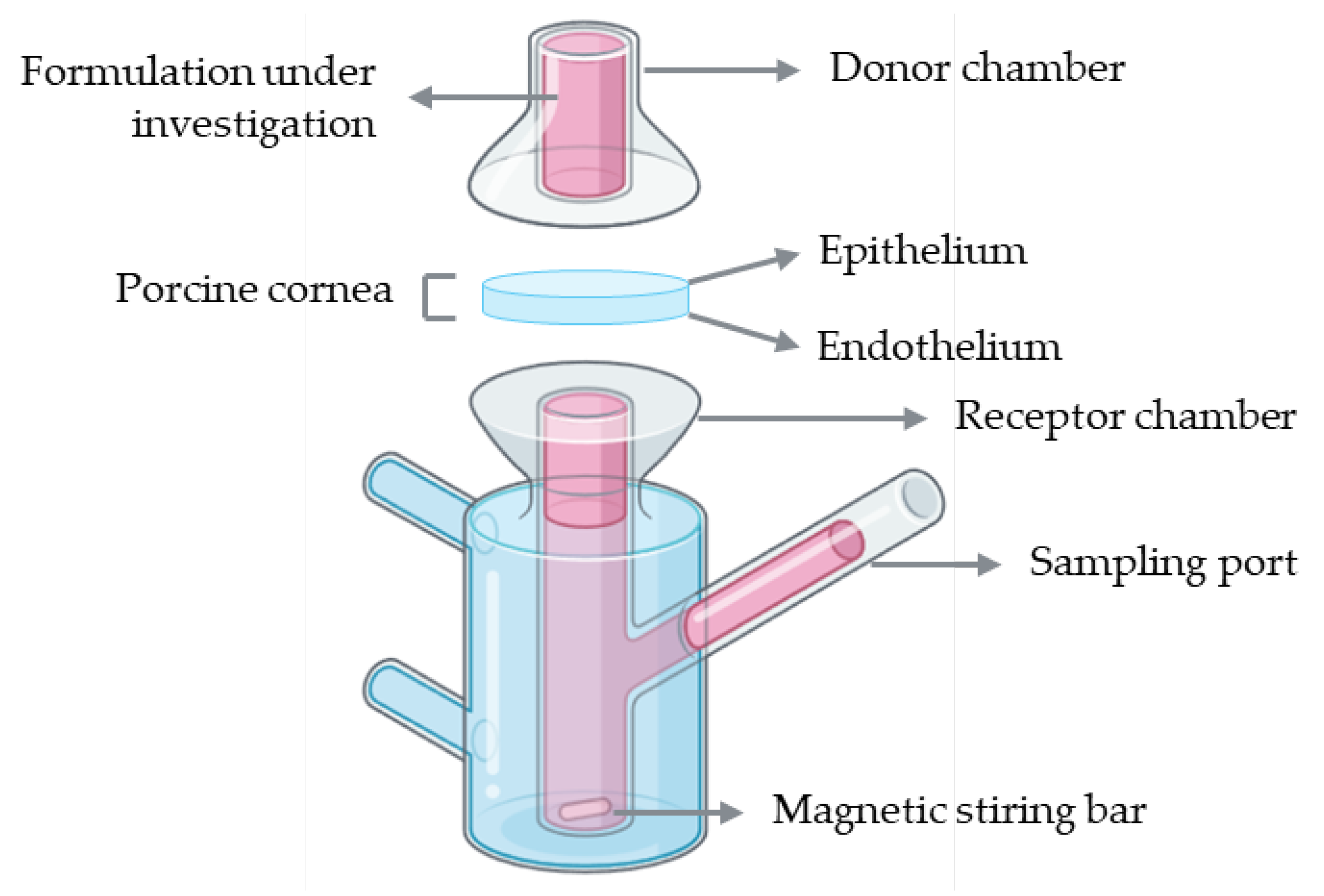

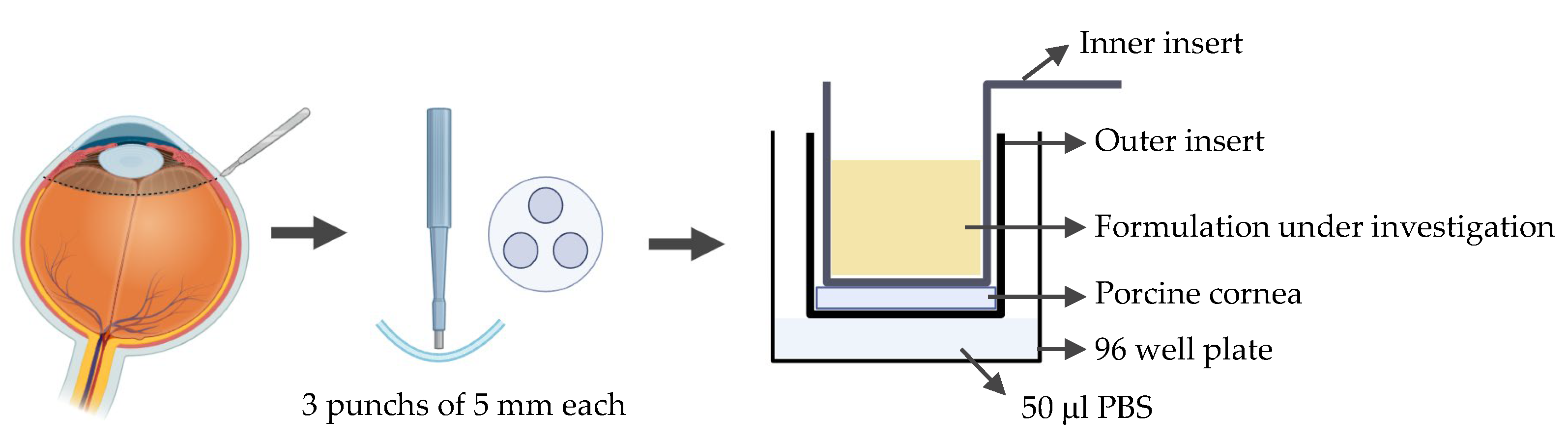

3.2. Drug Permeability

4. Critical Evaluation and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AM | Acetoxymethyl ester |

| CMFDA | 5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate |

| D | Diopter |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| TPGS | D-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol succinate |

| UV–Vis | Ultraviolet–visible |

| ZO-1 | Zonula occludens-1 |

References

- Remington, L.A. Visual System. Clinical Anatomy and Physiology of the Visual System 2012, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Ophthalmology Fundamentals and Principles of Ophthalmology; 2024.

- Remington, L.A. Cornea and Sclera. Clinical Anatomy and Physiology of the Visual System 2012, 10–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, L.; Fu, Y. Nanotechnology-Based Ocular Drug Delivery Systems: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2023 21:1 2023, 21, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, Y.Y.; Tong, L. Barrier Function in the Ocular Surface: From Conventional Paradigms to New Opportunities. Ocular Surface 2015, 13, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiseau, A.; Raîche-Marcoux, G.; Maranda, C.; Bertrand, N.; Boisselier, E. Animal Models in Eye Research: Focus on Corneal Pathologies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, Vol. 24, Page 16661 2023, 24, 16661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Do, K.K.; Wang, F.; Lu, X.; Liu, J.Y.; Li, C.; Ceresa, B.P.; Zhang, L.; Dean, D.C.; Liu, Y. Zeb1 Facilitates Corneal Epithelial Wound Healing by Maintaining Corneal Epithelial Cell Viability and Mobility. Commun Biol 2023, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.C.G.; Chialchia, A.R.; de Castro, E.G.; e Silva, M.R.L.; Arantes, D.A.C.; Batista, A.C.; Kitten, G.T.; Valadares, M.C. A New Corneal Epithelial Biomimetic 3D Model for in Vitro Eye Toxicity Assessment: Development, Characterization and Applicability. Toxicology in Vitro 2020, 62, 104666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluzhny, Y.; Kinuthia, M.W.; Truong, T.; Lapointe, A.M.; Hayden, P.; Klausner, M. New Human Organotypic Corneal Tissue Model for Ophthalmic Drug Delivery Studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018, 59, 2880–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiju, T.M.; Carlos de Oliveira, R.; Wilson, S.E. 3D in Vitro Corneal Models: A Review of Current Technologies. Exp Eye Res 2020, 200, 108213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, F.; Grottone, G.T.; Covre, J.L.; Cristovam, P.C.; Loureiro, R.R.; Pinheiro, F.I.; Casaroli-Marano, R.P.; Donato, W.; Gomes, J.Á.P. A Framework for Human Corneal Endothelial Cell Culture and Preliminary Wound Model Experiments with a New Cell Tracking Approach. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, Vol. 24, Page 2982 2023, 24, 2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkoc-Biradli, F.Z.; Ozgun, A.; Öztürk-Öncel, M.Ö.; Marcali, M.; Elbuken, C.; Bulut, O.; Rasier, R.; Garipcan, B. Bioinspired Hydrogel Surfaces to Augment Corneal Endothelial Cell Monolayer Formation. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2021, 15, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travers, G.; Coulomb, L.; Aouimeur, I.; He, Z.; Bonnet, G.; Ollier, E.; Gavet, Y.; Moisan, A.; Gain, P.; Thuret, G.; et al. Investigating the Role of Molecular Coating in Human Corneal Endothelial Cell Primary Culture Using Artificial Intelligence-Driven Image Analysis. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balters, L.; Reichl, S. 3D Bioprinting of Corneal Models: A Review of the Current State and Future Outlook. J Tissue Eng 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Hoon, I.; Boukherroub, R.; De Smedt, S.C.; Szunerits, S.; Sauvage, F. In Vitro and Ex Vivo Models for Assessing Drug Permeation across the Cornea. Mol Pharm 2023, 20, 3298–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, Y.; García-Posadas, L. Ex Vivo Applications of Porcine Ocular Surface Tissues: Advancing Eye Research and Alternatives to Animal Studies. Histol Histopathol 2025, 40, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, G.N.; Falcão, M.A.; Lopes, J.M.S.; Lopes, J.M.; Contarato, J.L.A.; Gelfuso, G.M.; Cunha-Filho, M.; Gratieri, T. Dynamic Ex Vivo Porcine Eye Model to Measure Ophthalmic Drug Penetration under Simulated Lacrimal Flow. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescina, S.; Govoni, P.; Potenza, A.; Padula, C.; Santi, P.; Nicoli, S. Development of a Convenient Ex Vivo Model for the Study of the Transcorneal Permeation of Drugs: Histological and Permeability Evaluation. J Pharm Sci 2015, 104, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.-D.; Sung, K.-C.; Huang, J.-M.; Chen, C.-H.; Wang, Y.-J.; Shi, M.-D.; Sung, K.-C.; Huang, J.-M.; Chen, C.-H.; Wang, Y.-J. Development of an Ex Vivo Porcine Eye Model for Exploring the Pathogenicity of Acanthamoeba. Microorganisms 2024, Vol. 12, Page 1161 2024, 12, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okurowska, K.; Roy, S.; Thokala, P.; Partridge, L.; Garg, P.; Macneil, S.; Monk, P.N.; Karunakaran, E. Establishing a Porcine Ex Vivo Cornea Model for Studying Drug Treatments against Bacterial Keratitis. J Vis Exp 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.C.; Kureshi, A.; Daniels, J.T. Establishment of an Ex Vivo Human Corneal Endothelium Wound Model. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2025, 14, 24–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, N.; Gillespie, S.R.; Bernstein, A.M. Ex Vivo Corneal Organ Culture Model for Wound Healing Studies. J Vis Exp 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netto, A.R.T.; Hurst, J.; Bartz-Schmidt, K.-U.; Schnichels, S.; Rocha, A.; Netto, T.; Hurst, J.; Bartz-Schmidt, K.-U.; Schnichels, S. Porcine Corneas Incubated at Low Humidity Present Characteristic Features Found in Dry Eye Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, Vol. 23, Page 4567 2022, 23, 4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhbakhshzaeri, M.; Rabiee, B.; Azar, N.; Ghahari, E.; Putra, I.; Eslani, M.; Djalilian, A.R. New Ex Vivo Model of Corneal Endothelial Phacoemulsification Injury and Rescue Therapy with Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Secretome. J Cataract Refract Surg 2019, 45, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues da Penha, J.; Garcia da Silva, A.C.; de Ávila, R.I.; Valadares, M.C. Development of a Novel Ex Vivo Model for Chemical Ocular Toxicity Assessment and Its Applicability for Hair Straightening Products. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2022, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarfraz, M.; Behl, G.; Rani, S.; O’Reilly, N.; McLoughlin, P.; O’Donovan, O.; Lynch, J.; Fitzhenry, L.; Sarfraz, M.; Reynolds, A.L.; et al. Development and in Vitro and Ex Vivo Characterization of a Twin Nanoparticulate System to Enhance Ocular Absorption and Prolong Retention of Dexamethasone in the Eye: From Lab to Pilot Scale Optimization. Nanoscale Adv 2025, 7, 3125–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, S.S.; Shrestha, D.; Rupenthal, I.D. Evaluation of 2 Ex Vivo Bovine Cornea Storage Protocols for Drug Delivery Applications. Ophthalmic Res 2019, 61, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehab, A.; Gram, N.; Ivarsen, A.; Hjortdal, J. The Importance of Donor Characteristics, Post-Mortem Time and Preservation Time for Use and Efficacy of Donated Corneas for Posterior Lamellar Keratoplasty. Acta Ophthalmol 2022, 100, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.E. Bowman’s Layer in the Cornea– Structure and Function and Regeneration. Exp Eye Res 2020, 195, 108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasy, S.M.; Eaton, J.S.; Timberlake, M.J.; Miller, P.E.; Matsumoto, S.; Murphy, C.J. Species Differences in the Geometry of the Anterior Segment Differentially Affect Anterior Chamber Cell Scoring Systems in Laboratory Animals. https://home.liebertpub.com/jop 2016, 32, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vézina, M. Comparative Ocular Anatomy in Commonly Used Laboratory Animals. Molecular and Integrative Toxicology 2012, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, I.; Martin, R.; Ussa, F.; Fernandez-Bueno, I. The Parameters of the Porcine Eyeball. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011, 249, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnichels, S.; Paquet-Durand, F.; Löscher, M.; Tsai, T.; Hurst, J.; Joachim, S.C.; Klettner, A. Retina in a Dish: Cell Cultures, Retinal Explants and Animal Models for Common Diseases of the Retina. Prog Retin Eye Res 2021, 81, 100880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.S.; Chen, W.; Libin, B.M.; S. boyer, D.; Kaiser, P.K.; Liebmann, J.M. Sustained Ocular Delivery of Bevacizumab Using Densomeres in Rabbits: Effects on Molecular Integrity and Bioactivity. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2023, 12, 28–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauchat, L.; Guerin, C.; Kaluzhny, Y.; Renard, J.P. Comparison of In Vitro Corneal Permeation and In Vivo Ocular Bioavailability in Rabbits of Three Marketed Latanoprost Formulations. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2023, 48, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Gao, N.; Yu, F.S. Interleukin-36 Receptor Signaling Attenuates Epithelial Wound Healing in C57BL/6 Mouse Corneas. Cells 2023, Vol. 12, Page 1587 2023, 12, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akpek, E.K.; Aldave, A.J.; Amescua, G.; Colby, K.A.; Cortina, M.S.; Cruz, J.; Parel, J.M.A.; Li, G. Twelve-Month Clinical and Histopathological Performance of a Novel Synthetic Cornea Device in Rabbit Model. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2023, 12, 9–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, K.; Hatou, S.; Inagaki, E.; Higa, K.; Tsubota, K.; Shimmura, S. A Rabbit Corneal Endothelial Dysfunction Model Using Endothelial-Mesenchymal Transformed Cells. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Xi, L.W.Q.; Luu, W.; Enkhbat, M.; Neo, D.; Mehta, J.S.; Peh, G.S.L.; Yim, E.K.F. Preclinical Models for Studying Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Cells 2025, Vol. 14, Page 505 2025, 14, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, N.D.; Chen, E.; Tuwani, R.; Kompa, B.; Cox, S.M.; Cuneyt Ozmen, M.; Massaro-Giordano, M.; Beam, A.L.; Hamrah, P. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Model for Diagnosing Neuropathic Corneal Pain via in Vivo Confocal Microscopy. NPJ Digit Med 2025, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.K.; Pheby, D.; Henehan, G.; Brown, R.; Sieving, P.; Sykora, P.; Marks, R.; Falsini, B.; Capodicasa, N.; Miertus, S.; et al. Ethical Considerations Regarding Animal Experimentation. J Prev Med Hyg 2022, 63, E255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, B.K.; Stirland, D.L.; Lee, H.K.; Wirostko, B.M. Ocular Translational Science: A Review of Development Steps and Paths. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2018, 126, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, S. Porcine Ophthalmology. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 2010, 26, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menduni, F.; Davies, L.N.; Madrid-Costa, D.; Fratini, A.; Wolffsohn, J.S. Characterisation of the Porcine Eyeball as an In-Vitro Model for Dry Eye. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2018, 41, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo-Moral, M.; García-Posadas, L.; López-García, A.; Diebold, Y. Histological and Immunohistochemical Characterization of the Porcine Ocular Surface. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0227732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, C.H.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, M.K. Corneal Xenotransplantation: Where Are We Standing? Prog Retin Eye Res 2021, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peynshaert, K.; Devoldere, J.; De Smedt, S.C.; Remaut, K. In Vitro and Ex Vivo Models to Study Drug Delivery Barriers in the Posterior Segment of the Eye. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2018, 126, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, N.; Fallano, K.; Bussel, I.; Kagemann, L.; Lathrop, K.L. Training Strategies and Outcomes of Ab Interno Trabeculectomy with the Trabectome. F1000Res 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunette, I.; Rosolen, S.G.; Carrier, M.; Abderrahman, M.; Nada, O.; Germain, L.; Proulx, S. Comparison of the Pig and Feline Models for Full Thickness Corneal Transplantation. Vet Ophthalmol 2011, 14, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhbakhshzaeri, M.; Rabiee, B.; Azar, N.; Ghahari, E.; Putra, I.; Eslani, M.; Djalilian, A.R. New Ex Vivo Model of Corneal Endothelial Phacoemulsification Injury and Rescue Therapy with Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Secretome. J Cataract Refract Surg 2019, 45, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foja, S.; Heinzelmann, J.; Hünniger, S.; Viestenz, A.; Rüger, C.; Viestenz, A. Drug-Dependent Inhibitory Effects on Corneal Epithelium Structure, Cell Viability, and Corneal Wound Healing by Local Anesthetics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, Vol. 25, Page 13074 2024, 25, 13074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, E.P.Y.; To, T.S.S.; Cho, P.; Benzie, I.F.F.; Choy, C.K.M. Viability of Porcine Corneal Epithelium Ex Vivo and Effect of Exposure to Air: A Pilot Study for a Dry Eye Model. Cornea 2004, 23, 715–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.Y.; Cho, P.; Boost, M. Corneal Epithelial Cell Viability of an Ex Vivo Porcine Eye Model. Clin Exp Optom 2014, 97, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodella, U.; Bosio, L.; Ferrari, S.; Gatto, C.; Giurgola, L.; Rossi, O.; Ciciliot, S.; Ragazzi, E.; Ponzin, D.; Tóthová, J.D. Porcine Cornea Storage Ex Vivo Model as an Alternative to Human Donor Tissues for Investigations of Endothelial Layer Preservation. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2023, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, M.Y.; Gerena, V.A.; Navia, J.L. Corneal Crosslinking with Genipin, Comparison with UV-Riboflavin in Ex-Vivo Model. Mol Vis 2012, 18, 1068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.W.; Shin, Y.J.; Lee, S.C.S. Novel ROCK Inhibitors, Sovesudil and PHP-0961, Enhance Proliferation, Adhesion and Migration of Corneal Endothelial Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 14690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, C.A.; Brookes, N.H.; Clover, G.M. Confocal Imaging of the Keratocyte Network in Porcine Cornea Using the Fixable Vital Dye 5-Chloromethylfluorescein Diacetate. Curr Eye Res 1996, 15, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoon, I.; Boukherroub, R.; De Smedt, S.C.; Szunerits, S.; Sauvage, F. In Vitro and Ex Vivo Models for Assessing Drug Permeation across the Cornea. Mol Pharm 2023, 20, 3298–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, A.P.; Silva, B.; Braz, B.S.; Nunes, T.; Gonçalves, L.; Delgado, E. Ex Vivo Permeation of Erythropoietin through Porcine Conjunctiva, Cornea, and Sclera. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2017, 7, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brütsch, D.R.; Hunziker, P.; Pot, S.; Tappeiner, C.; Voelter, K. Corneal and Scleral Permeability of Desmoteplase in Different Species. Vet Ophthalmol 2020, 23, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Segura, L.; Parra, A.; Calpena, A.C.; Gimeno, Á.; Boix-Montañes, A. Carprofen Permeation Test through Porcine Ex Vivo Mucous Membranes and Ophthalmic Tissues for Tolerability Assessments: Validation and Histological Study. Veterinary Sciences 2020, Vol. 7, Page 152 2020, 7, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, A.J.; Petalas, D.; Skondra, P.; Rico, H.; Garrigues, T.M.; Melero, A. Ciprofloxacin Self-Dissolvable Soluplus Based Polymeric Films: A Novel Proposal to Improve the Management of Eye Infections. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2021, 11, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostacolo, C.; Caruso, C.; Tronino, D.; Troisi, S.; Laneri, S.; Pacente, L.; Del Prete, A.; Sacchi, A. Enhancement of Corneal Permeation of Riboflavin-5′-Phosphate through Vitamin E TPGS: A Promising Approach in Corneal Trans-Epithelial Cross Linking Treatment. Int J Pharm 2013, 440, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, T.P. de A.; Kishishita, J.; Souza, A.T.M.; Vieira, J.R.C.; Melo, C.M.L. de; Santana, D.P. de; Leal, L.B. A Proposed Eye Ex Vivo Permeation Approach to Evaluate Pesticides: Case Dimethoate. Toxicology in Vitro 2020, 66, 104833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbalho, G.N.; Falcão, M.A.; Lopes, J.M.S.; Lopes, J.M.; Contarato, J.L.A.; Gelfuso, G.M.; Cunha-Filho, M.; Gratieri, T. Dynamic Ex Vivo Porcine Eye Model to Measure Ophthalmic Drug Penetration under Simulated Lacrimal Flow. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhujbal, S.; Rupenthal, I.D.; Agarwal, P. Evaluation of Ocular Tolerability and Bioavailability of Tonabersat Transfersomes Ex Vivo. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Mei, H.; Cui, H.; Song, M.; Qiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Lei, Y. Permeation Dynamics of Organic Moiety-Tuned Organosilica Nanoparticles across Porcine Corneal Barriers: Experimental and Mass Transfer Analysis for Glaucoma Drug Delivery. Biomed Phys Eng Express 2025, 11, 045015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Behl, G.; Rani, S.; O’Reilly, N.; McLoughlin, P.; O’Donovan, O.; Lynch, J.; Fitzhenry, L.; Sarfraz, M.; Reynolds, A.L.; et al. Development and in Vitro and Ex Vivo Characterization of a Twin Nanoparticulate System to Enhance Ocular Absorption and Prolong Retention of Dexamethasone in the Eye: From Lab to Pilot Scale Optimization. Nanoscale Adv 2025, 7, 3125–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, G.; Leigh, T.; Courtie, E.; Moakes, R.; Butt, G.; Ahmed, Z.; Rauz, S.; Logan, A.; Blanch, R.J. Rapid Assessment of Ocular Drug Delivery in a Novel Ex Vivo Corneal Model. Sci Rep 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauwe, B.; Steen, P.E.V. Den; Opdenakker, G. The Biochemical, Biological, and Pathological Kaleidoscope of Cell Surface Substrates Processed by Matrix Metalloproteinases. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 2007, 42, 113–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z. Corneal Alternations Induced by Topical Application of Benzalkonium Chloride in Rabbit. PLoS One 2011, 6, e26103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Li, N.; Fan, L.; Lu, J.; Liu, B.; Zhang, B.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Pi, J.; et al. Study of Penetration Mechanism of Labrasol on Rabbit Cornea by Ussing Chamber, RT-PCR Assay, Western Blot and Immunohistochemistry. Asian J Pharm Sci 2019, 14, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Guimarães, P.; Campos, E.J.; Fernandes, R.; Martins, J.; Castelo-Branco, M.; Serranho, P.; Matafome, P.; Bernardes, R.; Ambrósio, A.F. Retinal OCT-Derived Texture Features as Potential Biomarkers for Early Diagnosis and Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2025, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Y.H.; Uematsu, M.; Kusano, M.; Inoue, D.; Tang, D.; Suzuki, K.; Kitaoka, T. A Novel Technique for Corneal Transepithelial Electrical Resistance Measurement in Mice. Life 2024, Vol. 14, Page 1046 2024, 14, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anterior chamber | Posterior chamber | Vitreous | Whole eye | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average depth (emmetropic eye) | 3.11 mm | 0.52 mm | 16.5 mm | 23-25 mm |

| Volume | 220 μL | 60 μL | 5-6 mL | 6.5-7 mL |

| Content | Aqueous | Aqueous | Vitreous |

| Mouse | Rat | Rabbit | Porcine | Human | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average eye dimension in volume (cm3) | 0.025 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 6.5 | 7.2 |

| Average eye dimension (axial length in mm) | 3.4 | 6.0 | 17.1 | 23.9 | 24 |

| Corneal horizontal diameter (mm) | 3.15 | 5.1 | 13.4 | 14.3 | 11.81 |

| Corneal thickness (µm) | 0.089-0.123 | 0.16-2 | 0.36 | 543-797 | 530-710 |

| Cornea shape | flat | flat | dome | dome | dome |

| Bowman’s membrane | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Time between eye blinks | 5 min | 5 min | 6 min | 20-30 s | 5 s |

| References | [6,29,30,31] | [6,29,30,31,32] | [1,6,29,30,31,33] | ||

| Porcine | Human | |

|---|---|---|

| Corneal curvature | 7.85-8.28 mm [44] | 6.5-7.8 mm [3] |

| Corneal epithelium thickness | 80 μm [32] | 50 μm [3] |

| Corneal epithelium cell layers | 6-8 layers [45] | 4-6 layers [2] |

| Corneal endothelium cell density | 3250 cell/mm2 [44] | 2496.9-4049.5 cell/mm2 [44] |

| Retinal thickness | 300 μm [33] | 310 μm [33] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).