Introduction

The biomedical community is engaging in a campaign to persuade the public to severely reduce the amount of alcohol (or ethanol, to use the more precise scientific terminology) that people drink. Some medical experts warn that “the level of alcohol consumption that minimises health loss is zero” [

1,

2]. Several prominent recent publications recommend that drinking should be drastically curtailed and call for public policies to achieve this end. Conversely, other research suggests that moderate ethanol consumption has some health benefits [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. All parties to these debates generally accept that, even below the pathological level of drinking known as “alcoholism” or “alcohol use disorder” (AUD), a lifestyle of sustained ethanol consumption beyond moderate levels can cause several health problems, including several forms of cancer, liver disease, and birth defects [

8]. However, if history is a predictor, these calls to reduce drinking ethanol are unlikely to inspire many people to quit.

Many religious and political movements have sought to curb or ban ethanol consumption. For example, in the United States between 1920 and 1933, a period commonly known as Prohibition, the country amended the United States Constitution to outlaw the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcohol. While state and federal Prohibition laws banning the sale of almost all alcohol initially caused a decline in the public’s consumption by ~70%, this decline rebounded within one year despite the laws’ existence. By the end of Prohibition, the public’s consumption had risen to 30-40% above the level in the year before Prohibition was instituted and the government’s effort to convince its citizens to abandon alcohol consumption was deemed a failure [

9]. With minor fluctuations, the percentage of American and European adults who drink has changed little since the 1930s, with an average from surveys over the years of around 63% in the United States and even higher in Europe [

10,

11]. Most consumers of alcohol are social drinkers who consume moderate amounts, and less than 10% manifest symptoms of alcohol addiction. Thus, for the general population aware of the health risks, continued drinking cannot be explained by addiction. This steady average alcohol consumption is in sharp contrast to tobacco use, which has decreased by roughly two-thirds since the addictive aspects of nicotine and smoking’s health risks became evident starting in the 1960s [

12,

13]. What drives people to continue drinking alcohol and how do we explain the widespread, persistent demand for alcohol despite campaigns and policies to dissuade us, for moral or medical reasons, from drinking?

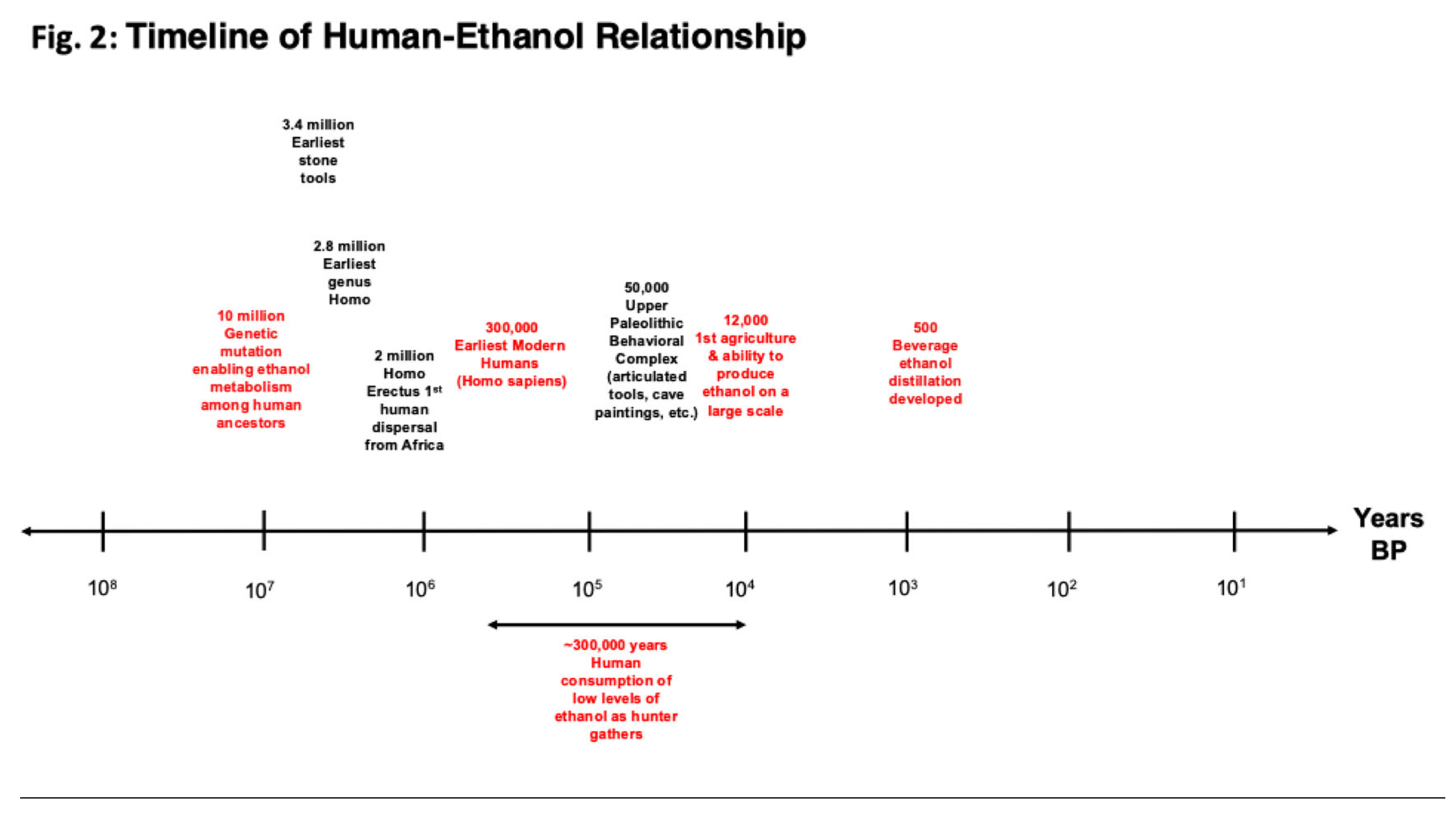

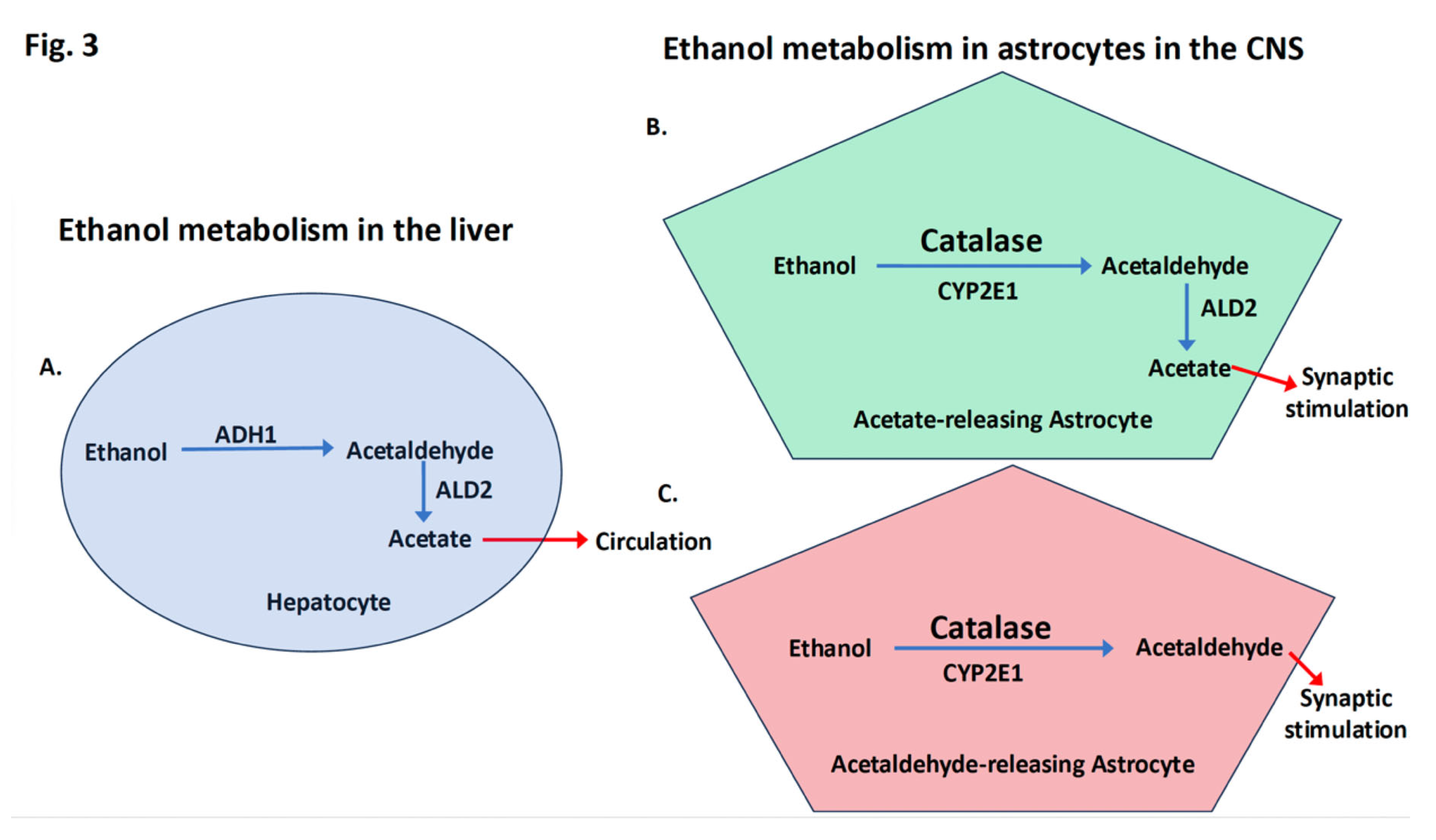

Those questions have several answers for which the social and cultural history of drinking provides context. Our human ancestors were consuming ethanol long before modern humans existed, starting from the point in time that our primate ancestors adapted to eating a fruit-based diet (i.e., frugivory). The psychoactive effects on the brain from eating fermented fruit resulted from mutations in the genes controlling enzymes, alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALH), which together breakdown ethanol into acetate mainly in the liver (see

Figure 3 A), and allowed for the consumption of over-ripe, fermenting fruit. Estimates are that these mutations occurred well before the genus Homo appeared. Based on genetic analysis and comparisons of many frugivore vs. non-frugivore primate species, the genetic mutations that allowed our distant human ancestors and other primate species to metabolize ethanol occurred about 10 to 12 million years ago (see

Figure 2) [

14,

15,

16]. One suggestion, the “drunken monkey hypothesis”, proposes that our current attraction to alcohol derives from this early experience that included a dependence on fermenting fruit for sustenance and the ability to find it by the smell of alcohol [

17]. But this idea does not account for the crucial intervening period of human evolution when our patterns of social interaction and culture developed and had a profound influence on structuring modern behavior and tastes. In fact, most people who abstain from drinking alcohol around the world generally do so for cultural reasons (principally religious ideologies) rather than from any genetically based proclivity (with the possible exception in the case of the “Asian flush syndrome”) [

18].

In addition, for modern humans, alcohol is an important cultural object and social tool. It is no longer something consumed opportunistically in the wild. Instead, it is a ubiquitous form of material culture that humans produce in large quantities from an astonishing variety of substances (basically anything that has sugar or starch) by an enormous variety of techniques. Moreover, humans consume alcohol in a wide range of elaborate culturally-prescribed practices that give it meaning and value [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. This has been the case since at least the development of agriculture over 10,000 years ago, as recent archaeological evidence from the Middle East, China, and other regions demonstrates [

25,

26,

27,

28]. In fact, some archaeologists have suggested that human desire for alcohol, rather than ordinary food, lies behind agriculture’s development. Although this intriguing hypothesis is impossible to verify, alcohol production was clearly part of how early humans used domesticated crops, including cereal cultivation, in multiple locations in Southwest Asia during the Late Epipaleolithic, over ten millennia ago [

29,

30]. Our complex relationship with alcohol is not only ancient, but global. At the time of European colonial expansion beginning in the 15th century, nearly every region of the world, except parts of North America and the Pacific, already had its own indigenous forms of alcohol. In brief, the consumption of alcohol is deeply embedded culturally in a wide range of societies around the world in complex ways that cannot be explained simply by common urges related to distant human ancestors.

The Links Between Ethanol Drinking, Its Fermentation, and Social Bonding During Human Evolution

Modern humans emerged as a separate species ~300,000 years ago. The challenges faced by hunter-gathers shaped subsequent human evolution especially through changes in the cortical regions of our central nervous system (CNS) [

31]. This evolution of the human brain played a critical role in acquiring our unique human social-cognitive skills, such as language and cultural learning [

32]. As discussed above, early humans first consumed low levels of ethanol from scavenged fermenting sources. The ethanol produced psychostimulant effects that were also disinhibitory, relaxing and euphoric. Many social scientists have suggested that low levels of ethanol consumption benefitted human evolution through its social bonding effects and the building of group dynamics among humans [

33,

34]. A recent study has also found similar social bonding effects of ethanol for chimpanzees in the wild sharing fermenting fruit [

35]. Similar to the function of ethanol today, where it plays a vital role in hospitality everywhere it is used, foods containing ethanol became highly sought after as a catalyst for humans to gather together for ethanol consumption, food sharing, rituals, and the exchange of ideas and information [

36].

The social bonding role of ethanol appears to have motivated humans to learn by trial and error how to ferment ethanol, one of the most important early human discoveries. This process of deconstructing how to ferment ethanol must have been multistep starting with the identification of the starch or sugar sources needed for ethanol fermentation. These discoveries, in turn, led to the discovery of the steps needed for fermentation and the realization that the fermentation process could be harnessed to control ethanol production. This enabled early humans to become independent of scavenging for ethanol sources and manage ethanol availability, though limited to low levels compared to what became possible once humans developed agrarian methods.

Importantly, ethanol production often required a significant amount of joint human effort, especially with the fermentation of grains, which likely became a significant communal organizing effort in terms of both ethanol production and its consumption at meals or feasts [

37,

38].

The importance of ethanol production to early humans and the substantial amount of effort applied to this function is evident from the fact that it often had to be reinvented or adapted as humans migrated out of Africa and across the world. In each new place humans settled they exerted significant effort to find new starch and sugar sources to replace sources no longer available. These new sources required humans to find new methods to convert the new sugar or starch source into ethanol. Human migration, along with the constant demand for ethanol, inspired the early discovery and use of an enormous variety of starting materials and methods for ethanol fermentation [

39]. As humans adopted agrarian lifestyles, they engaged in trade across regions that eventually benefitted the most favored, efficient, and economical forms of ethanol production.

Given the importance of ethanol consumption and production to human history, understanding how ethanol mediates its pharmacological and physiological effects is critical. Consequently, we discuss mounting evidence about the way that ethanol is metabolized in the brain and why this may be relevant to understanding what initially motivated ethanol consumption, its social uses and value as a cultural object.

Why Is Human Consumption of Ethanol at Low Levels Stimulatory and What Does That Tell Us About Drinking Ethanol?

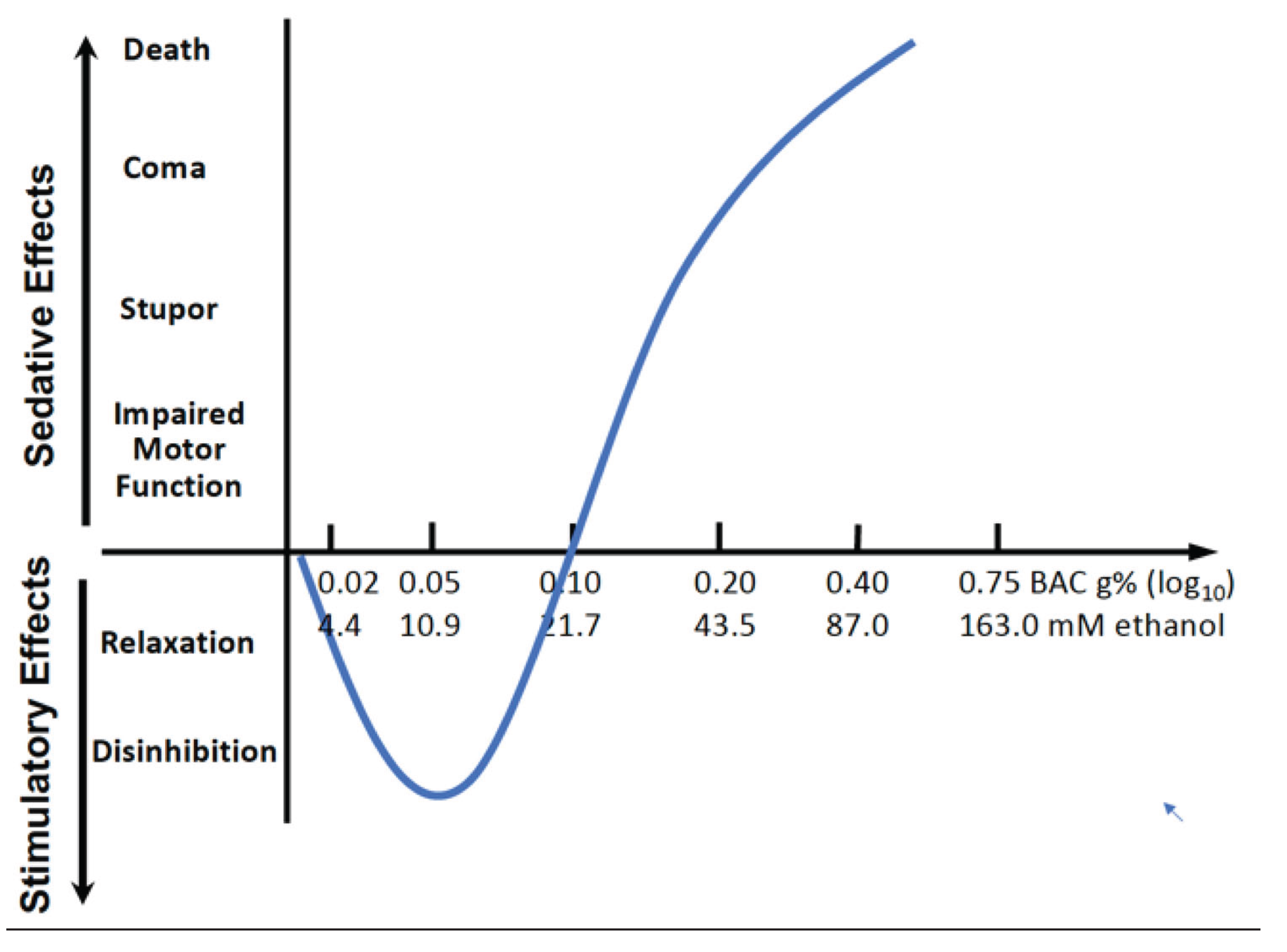

The effects of drinking low amounts of ethanol are summarized in a review by Cui and Koob [

40]. That work concludes that drinking ethanol has two very different effects (see

Figure 1). At low drinking levels (1-2 drinks, blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 10 mM or below), ethanol is stimulatory, but also acts to relax the drinker and lower inhibitions. Above these low levels, the effects of ethanol become the exact opposite of stimulatory. At higher levels of consumption, the drinker becomes progressively more sedated, and at even higher levels, can lose physical coordination and, eventually, consciousness. These “biphasic” behavioral effects are well established in humans and animal models of ethanol drinking [

41,

42]. The biphasic nature of how increasing ethanol dose affects human behavior is similar to the “J-shaped” relation suggested by many studies between ethanol consumption and mortality and cardiovascular disease, where drinking at lower ethanol levels is associated with a lower risk

4, 43. These findings are currently controversial and a matter of ongoing debate

1, 5.

How are the biphasic effects of ethanol on behavior at low and high ethanol levels explained? Currently, it is assumed that ethanol’s stimulatory effects as well as its sedative effects occur through the direct interaction of ethanol with many different protein targets [

40,

44,

45,

46]. Here we propose that the mechanisms underlying the opposing pharmacological effects of ethanol at low and high levels are different. Recent findings discussed in more detail below suggest that psychostimulatory effects of ethanol result from the stimulatory effects of ethanol metabolism byproducts, acetaldehyde and acetate, not ethanol itself (see

Figure 3). Contrary to this, it is generally assumed that ethanol’s stimulatory effects as well as its sedative effects occur through the direct interaction of ethanol with several different protein targets [

40,

44,

45,

46].

The evidence is quite strong that intact ethanol directly causes the sedative and other effects observed at higher levels observed (see

Figure 1). Overall, studies have identified ~10 different protein targets whose function is directly altered by ethanol. Most of the targets are ionotropic neurotransmitter receptors and ion channels each of which are either excitatory or inhibitory in terms how they alter neuronal excitability. Generally, for proteins that are inhibitory (e.g., GABA and glycine receptors, potassium channels) ethanol acts to potentiate their inhibitory effects, while for proteins that are excitatory (e.g., NMDA and nicotinic receptors, calcium channels) ethanol acts to inhibit excitatory effects. Therefore, the overall effects of ethanol on its targets dampens neuronal excitability consistent with most of the targets mediating sedative effects. Most of the research in support of ethanol binding directly to target proteins only saw effects with ethanol concentrations higher than 10 mM, and when ethanol was applied in the range of 1 – 10 mM generally the effects were marginal. In these studies, the effects of ethanol were measured functionally by applying ethanol directly onto the cells to measure its physiological responses. These procedures are highly accurate in applying a set ethanol concentration acutely, but act to bypass any ethanol metabolic breakdown that might act to significantly reduce ethanol concentrations. To conclude, while it remains a possibility that the direct binding of ethanol to its protein targets underlies the stimulatory and other effects of ethanol at low levels, most of the evidence is consistent with the targeted binding of ethanol underlying ethanol’s sedative effects at higher levels.

Figure 1.

The biphasisc effects of ethanol with increasing blood alcohol (ethanol) concentrations (BACs). Increased levels of ethanol in the blood cause two different effects, initially a set of “stimulatory” effects at lower ethanol levels, which peak and then are followed by a set of “sedative” effects at higher ethanol levels. The data from

Figure 1 in Cui and Koob [

40] have been replotted to emphasize the parallels with the “J-shaped curve” effects of ethanol drinking at low and high levels.

Figure 1.

The biphasisc effects of ethanol with increasing blood alcohol (ethanol) concentrations (BACs). Increased levels of ethanol in the blood cause two different effects, initially a set of “stimulatory” effects at lower ethanol levels, which peak and then are followed by a set of “sedative” effects at higher ethanol levels. The data from

Figure 1 in Cui and Koob [

40] have been replotted to emphasize the parallels with the “J-shaped curve” effects of ethanol drinking at low and high levels.

If the stimulatory effects of ethanol are caused by its metabolism in the brain, then its impact being restricted to low ethanol levels (lower than 0.10 g% BAC or 21.7 mM as in

Figure 1) can be explained by a limited capacity to breakdown ethanol. Ethanol levels will increase when ethanol exceeds this capacity where breakdown is saturated. Significant ethanol then remains intact allowing it to interact with its targets, which cause the other ethanol-related effects. The limits of metabolic capacity are reached at the zenith of the curve in

Figure 1 at which point the the sedative effects of ethanol begin to dominate over the stimulatory effects. As a result, the curve changes direction as the sedative effects begin to dominate over the stimulatory effects. More specifically, the sedative effects exist throughout the negative slope, and that they dominate at the zero crossingare only evident at the ethanol levels where the line crosses the x-axis. At these ethanol levels the stimulatory effects are balanced by the sedative effects after which the sedative effects predominate. The limited capacity of the brain’s ethanol metabolism is different from elsewhere in our bodies, in particular the liver, where ethanol breakdown increases well beyond the low ethanol levels of breakdown that exist in the brain.

The apparent limited capacity of the brain to metabolize ethanol raises the question of why it is limited to this range of ethanol? A highly plausible explanation for why there is this limited capacity is that before and after humans evolved from other primates, ethanol consumption did not go beyond this range of ethanol. Thus, the human brain adapted to this range over around 300,000 years of further evolution (see

Figure 2 timeline). Aside from exceptional sporadic events, human drinking would probably not have extended to higher ethanol levels that had sedative effects until quite recently. Humans only began significant production of ethanol drinks with the transition from a hunter gatherer to an agrarian lifestyle, which occurred about 11,000 to 12,000 years ago in Southwest Asia and at least 8,000 years ago in East Asia (see

Figure 2 timeline) [

47]. Before that time, exceeding a low-level range of alcohol consumption would have been nearly impossible, especially with any regularity over a sustained period, and alcoholism and alcohol use disorders (AUDs) would have been absent. Even with the development of agriculture, although the possibilities for more regular production of larger amounts of alcohol increased, this would probably not have been sufficient to present serious problems with alcoholism and AUDs. Most traditional forms of alcohol spoil rapidly and must be consumed immediately after fermentation. The advent of serious social problems with ethanol likely did not occur until the development of stable forms of alcohol that could be traded over long distances and stockpiled (such as wine), and the potential for such problems increased dramatically with the use of distillation to produce beverage alcohol from the 15th century on.

Figure 2.

Timeline of the relationship between humans during their evolution and drinking ethanol. Time before present (BP) is displayed on the x-axis on a logarithmic scale over 100 million years. Events in red are ethanol related events in human history. Events in black are human evolutionary milestones.

Figure 2.

Timeline of the relationship between humans during their evolution and drinking ethanol. Time before present (BP) is displayed on the x-axis on a logarithmic scale over 100 million years. Events in red are ethanol related events in human history. Events in black are human evolutionary milestones.

Human Evolution and the Metabolism of Ethanol in Our Brains

Figure 3.

Differences between ethanol metabolism in the liver in hepatocytes (A) and in the CNS where most breakdown occurs in a subset of astrocytes (B and C). A. In hepatocytes, there is a high capacity for ethanol breakdown. Ethanol, even at very high levels, is metabolized preventing acetaldehyde buildup and the final product, acetate, is released into the blood stream. B. In the CNS, it is established that the enzyme ALD2, which converts acetaldehyde into acetate, is found in a select subset of astrocytes, which act to release acetate and result in synaptic stimulation. C. We suggest that other astrocytes that lack ALD2, as shown here, act as a second astrocyte subtype that stimulate synapses through the release of low levels of acetaldehyde. Altogether, the data suggest that the main function of ethanol metabolism in the CNS is to stimulate select neuronal circuits while reducing the ethanol concentration.

Figure 3.

Differences between ethanol metabolism in the liver in hepatocytes (A) and in the CNS where most breakdown occurs in a subset of astrocytes (B and C). A. In hepatocytes, there is a high capacity for ethanol breakdown. Ethanol, even at very high levels, is metabolized preventing acetaldehyde buildup and the final product, acetate, is released into the blood stream. B. In the CNS, it is established that the enzyme ALD2, which converts acetaldehyde into acetate, is found in a select subset of astrocytes, which act to release acetate and result in synaptic stimulation. C. We suggest that other astrocytes that lack ALD2, as shown here, act as a second astrocyte subtype that stimulate synapses through the release of low levels of acetaldehyde. Altogether, the data suggest that the main function of ethanol metabolism in the CNS is to stimulate select neuronal circuits while reducing the ethanol concentration.

Several recent findings suggest that a different mechanism mediates ethanol effects at low levels in vivo in the brain. How is ethanol metabolized in the brain compared to other organs? Outside the brain, ethanol is first broken down into acetaldehyde by one set of enzymes after which it is further broken down into acetate as displayed in

Figure 3. This same process occurs

naturally when ethanol solutions are contaminated by acetic acid bacteria (Acetobacter aceti

), the process that produces vinegar. Acetate or its protonated form, acetic acid, are the main components of vinegar. In the liver where most ethanol is metabolized, hepatocytes are designed for the detoxification of exogenous toxins like ethanol (

Figure 3A). Ethanol rapidly enters hepatocytes as we drink and is broken down by enzymes in the cytoplasm, mainly alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (ADH1;

Figure 3A) into acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde is more toxic than alcohol and almost immediately is broken down into acetate by a second, enzyme, aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALD2;

Figure 3A) that breaks down acetaldehyde into acetate, which is not toxic and is released into the blood stream. Asian flush syndrome occurs because of mutations that cause a genetic deficiency in ALD2 and an excess of acetaldehyde [

48,

49]. There are several billion hepatocytes in the liver providing a very large capacity to metabolize ethanol and many other substances.

In the brain, ethanol rapidly crosses the blood-brain barrier and distributes throughout the brain just as fast it enters the liver. The enzymes that break down ethanol into acetaldehyde in the brain appear to be different from the enzymes in the liver and other organs. In the brain, the role of ADH appears to be limited though there are exceptions and ADH may have a bigger role than realized [

50,

51]. Instead, the enzyme catalase, and to a lesser degree the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme CYP2E1 cooperate to oxidize ethanol to acetaldehyde (

Figure 3B, C). All cells throughout the body contain both enzymes. However, little is known about how catalase or CYP2E1 are regulated in the brain so that they are repurposed for ethanol metabolism. What brain regions, which cell types, and the expression levels of the enzymes are all possible factors that limit the metabolic capacity of catalase and CYP2E1 to breakdown ethanol in brain

50.

Recent studies have begun to examine the role of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2), the enzyme that breaks down acetaldehyde into acetate in the brain, and ALDH2 is currently better characterized in brain tissue than either catalase or CYP2E1. It is now established that in the rodent brain [

52,

53] and to a lesser degree in the human brain [

54,

55], ALDH2 distribution is heterogenous. It is expressed more in some brain regions, less in other regions, and not at a measurable level in still other regions [

53]. A recent study in mice found that synapses can be stimulated by the breakdown of ethanol locally in select brain regions and that the breakdown products are not entering the brain from other organs. The local breakdown of acetaldehyde to acetate is mediated by ALDH2 expressed in astrocytes, glial support cells, rather than neurons. This breakdown may be further restricted to a subset of ALDH2 astrocytes that are limited to certain regions of the brain [

53] and other parts of the CNS [

56]. Consequently, acetate production from ethanol in mice is increased in certain areas such as cerebellum and thalamus, and to a lesser extent in other brain regions. The picture that emerges from these studies is that the function of ethanol metabolism in the brain is very different from that in the liver and other organs. As displayed in

Figure 3A, ethanol metabolism in the liver is uniformly distributed over all the hepatocytes, which provide a high-capacity metabolic system that acts to deliver acetate via the blood stream throughout our bodies. Ethanol metabolism in the brain has a much lower capacity because it resides largely in a select set of astrocytes that function to release acetate (

Figure 3B) and perhaps acetaldehyde (

Figure 3C) locally at certain synapses.

Astrocyte Diversity and the Evolution of Ethanol Metabolism in the Human Brain

An important astrocyte function is to form a sheath at synapses that acts to nurture synapses as part of the “tripartite” synapse. Tripartite signifies the three components of the synapse: the presynaptic domain of the signaling neuron, the postsynaptic domain of the signal-receiving neuron, and the astrocyte sheath. The astrocyte sheath provides metabolites in high demand at synapses that can be converted into energy and are needed for neurotransmitter synthesis [

57]. Acetate can be transported from the astrocyte to the neuron where it is converted into acetyl-CoA [

58]. After, increases in acetyl-CoA in mitochondria at pre-synaptic and postsynaptic domains boosts mitochondrial ATP synthesis, which may be the basis of ethanol’s stimulatory effects. It has only recently become evident that the energy demands of active synapses can act to limit signaling in the brain [

59]. During human evolution, brain size, neuronal activity, and circuit complexity increased, which required increasing energy and synaptic adaptations.

Acetate itself is transported across the blood brain barrier independent of ethanol and, for the most part, is transported into astrocytes, not neurons nor other glial cells

60. Ethanol is different from acetate and other energy producing metabolites, such as glucose, because it is highly membrane permeable and does not need transporter proteins to facilitate crossing cell membranes. Consequently, compared to other energy-producing metabolites, ethanol much more rapidly crosses the blood brain barrier and enters cells in the CNS. For acetate to be then produced from ethanol, it appears that ethanol must first enter a specialized astrocyte subtype that specifically expresses ALD2 [

53]. In the specialized ALD2-expressing astrocytes, we suggest that ethanol breakdown can occur at astrocyte synaptic sheathes where newly synthesized acetate is positioned to be rapidly delivered to pre- or postsynaptic terminals where it can used for ATP production or neurotransmitter synthesis (see

Figure 3B).

The discovery that ethanol breakdown in the brain is handled by specialized ALD2-expressing astrocytes [

53] raises the possibility that there are other astrocytes subtypes specialized for ethanol breakdown that do not express ALD2. As displayed in

Figure 3C, these astrocytes would release acetaldehyde at synapses, which like acetate has been shown to be stimulatory when applied at low levels in the brain [

61]. A subset of acetaldehyde-secreting astrocytes that act locally can explain the stimulatory effects of low levels of acetaldehyde in the brain similar to the effects of ethanol yet acetaldehyde blood levels do not reach the levels that are stimulatory nor does acetaldehyde readily cross the blood brain barrier [

62,

63]. Together with the behavorial effects of inhibiting or increasing catalase activity in rats [

63,

64], these findings are consistent with acetaldehyde stimulation resulting from ethanol breakdown by catalase. What is not understood is why it has been so difficult to measure significant levels of acetaldehyde in brain regions [

63], which can be explained by limited local acetaldehyde secretion at synapses by a subset of astocytes that metabolize ethanol (

Figure 3C).

Growing evidence has found that astrocyte diversification into more complex subtypes, as in

Figure 3 B and C, occurred with the evolution of the human brain during the substantial growth of the cortex and other regions resulting in more intricate neural networks and cognitive abilities [

65]. We suggest that this astrocyte diversification into different ethanol-handling subtypes was catalyzed over the several hundred thousand years that humans evolved and began to control ethanol production. As a result, different astrocyte subtypes (

Figure 3B and C) were positioned at strategic locations in the brain such that the release of acetate and/or acetaldehyde from astrocyte synaptic sheathes stimulated human social bonding. In this way, low levels of alcohol consumption over time led to the breakdown of ethanol and reinforcement of the cortical circuits that enhanced human social bonding behaviors.

Other mammal species, especially those with diets high in fruit and nectar, have evolved parallel mechanisms in their livers to metabolize ethanol involving the same enzymes [

66]. Rodents in particular have evolved liver mechanisms like those used by humans to metabolize ethanol. Consequently, mice and rats have widely served as animal models for AUD studies. Mice also have evolved separate mechanisms in the brain for metabolizing ethanol like those of humans, as discussed above. The common features between mice and humans include the breakdown of ethanol locally in select brain regions that cause stimulation by ethanol, local breakdown of acetaldehyde to acetate is by astrocytes expressed ALDH2, and ALDH2 expression is restricted to a subset of astrocytes [

53]. While mice and humans share these features, it is likely that the brain locations where the stimulatory effects of ethanol occur for humans are very different from those of mice given that they were shaped by very different evolutionary circumstances. A detailed comparison between humans and mice, and if possible other species, at the single-cell level where the different ethanol metabolizing enzymes are expressed in the CNS is potentially an exciting strategy to address differences in how the brain’s system to metabolize ethanol differentially evolved and to identify the brain circuits in humans that evolved to receive the stimulatory effects of ethanol breakdown.

Conclusions

When considering what role alcohol drinking will have in our future, we need to fully understand what drove us to drink it originally and what will be lost as well as gained when addressing the very real health risks of ethanol. Humans and ethanol have a very deep history of entanglement with both biological and social implications, and here we tried to better understand why. Early in prehistoric human existence, ethanol consumption appears to have had a growing role in human social life, which must have stimulated efforts at production that were limited in scale and temporality by available resources. Constraints on ethanol production restricted consumption to low levels, which shaped how ethanol metabolism in the CNS evolved and stimulated social bonding. With the development of agriculture, the possibilities for more regular production of larger amounts of alcohol increased, albeit probably not enough to present serious problems with AUDs. Chronic, low-level consumption of ethanol may have been advantageous for health and fitness in our ancestors and many traditional forms of alcohol have been shown to be both nutritious and offer a variety of health benefits [

67]. But when highly concentrated alcohol became easily accessible, our behavioral and physiological adaptations to low levels of ethanol were mismatched and an “evolutionary hangover” began, with some humans developing problems of addiction and chronic abuse [

18,

66]. As discussed above, alcoholism and AUDs likely did not occur until recent developments of stable forms of alcohol. Ethanol consumption preceded and has continuously helped to shape human evolution and social relations beginning as hunter gathers and continuing to the present day [

18,

23,

68]. It is extremely important to continue to investigate the mechanisms underlying why ethanol and other drugs of abuse can be addictive, and why ethanol causes cancer and other AUDs. Also important going forward is understanding what has driven our lengthy evolutionary association with ethanol, why ethanol continues to be such an important and culturally valued good worldwide and what is lost by eliminating the drinking of ethanol.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no no conflicts of interest to declare. All authors have seen and approved the manuscript, and it has not been accepted or published elsewhere. We would like to thank Dr. Brian Hayden, Dr. John Maunsell, Dr. Ben Clites, Dr. Emma Erickson, Dr. Harold Zakon, Dr. Karl Matlin and Grace Dodier for their reading, editing and comments about the manuscript.

References

- GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Online August 23, 2018 (2018).

- World Health Organization. No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health. WHO News Release 4 January 2023. https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/04-01-2023-no-level-of-alcohol-consumption-is-safe-for-our-health (2023).

- Klatsky, A. L., Friedman, G. D. & Siegelaub, A. B. Alcohol consumption before myocardial infarction: Results from the Kaiser-Permanente epidemiologic study of myocardial infarction. Annals of Internal Medicine 81, 294-301 (1974).

- Ronksley, P. E., Brien, S. E., Turner, B. J., Mukamal, K. J. & Ghali, W. A. Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal 342:d671. (2011). [CrossRef]

- GBD 2020 Alcohol Collaborators. Population-level risks of alcohol consumption by amount, geography, age, sex, and year: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2020. The Lancet 400, 185-235 (2022).

- Stockwell, T. et al. Why do only some cohort studies find health benefits from low-volume alcohol use? A systematic review and meta-analysis of study characteristics that may bias mortality risk estimates. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 85, 441-452 (2024).

- Luo, H. et al. Modifiable risk factors and attributable burden of cardiac arrest: an exposome-wide and Mendelian randomization analysis. Canadian Journal of Cardiology 1-10 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Peele, S. The truth we won’t admit: drinking Is healthy. Pacific Standard August 12. https://psmag.com/social-justice/truth-wont-admit-drinking-healthy-87891/ (2014).

- Thornton, M. Alcohol prohibition was a failure. Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 157. https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/pa157.pdf (1991).

- Brenan, M. U.S. alcohol consumption on low end of recent readings. Gallup Poll Social Series August 19, 2021 [https://news.gallup.com/poll/353858/alcohol-consumption-low-end-recent-readings.aspx?version=print] (2021).

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health - 2014 Edition. (World Health Organization, 2014).

- US Department of Health and Human Services-Public Health Service. Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. (Office of the Surgeon General, 2020).

- Holford, T. R. et al. Tobacco control and the reduction in smoking-related premature deaths in the United States, 1964-2012. Journal of the American Medical Association 311, 164-171 (2014).

- Carrigan, M. A. et al. Hominids adapted to metabolize ethanol long before human-directed fermentation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112, 458-463 (2015).

- Carrigan, M. A. Hominoid adaptation to dietary ethanol, in Alcohol and Humans: A Long and Social Affair (eds Kimberley J. Hockings & Robin Dunbar) 24-44 (Oxford University Press, 2020).

- Dudley, R. The Drunken Monkey: Why We Drink and Abuse Alcohol. (University of California Press, 2014).

- Dudley, R. The natural biology of dietary ethanol and its implications for primate evolution, in Alcohol and Humans: A Long and Social Affair (eds Kimberley J. Hockings & Robin Dunbar) 9-23 (Oxford University Press, 2020).

- Clites, B. L., Hofmann, H. A. & Pierce, J. T. The promise of an evolutionary perspective of alcohol consumption. Neuroscience Insights (2023). 18: 26331055231163589. PMID: 37051560; PMCID: PMC10084549. [CrossRef]

- Bryceson, D. F. ed. Alcohol in Africa: Mixing Business, Pleasure, and Politics. (Heinemann, Portsmouth, N.H., 2002).

- Dietler, M. Alcohol: anthropological/archaeological perspectives. Annual Review of Anthropology 35, 229-249 (2006).

- Dietler, M. Alcohol as embodied material culture: anthropological reflections on the deep entanglement of humans and alcohol, in Alcohol and Humans: A Long and Social Affair (eds Robin Dunbar & Kimberley J. Hockings) 299-319 (Oxford University Press, 2020).

- Heath, D. B. Drinking Occasions: Comparative Perspectives on Alcohol and Culture. (Brunner/Mazel, 2000).

- Hornsey, I. S. Alcohol and its Role in the Evolution of Human Society. (RSC Publishing, 2012).

- Wilson, T. M. ed. Drinking Cultures: Alcohol and Identity. (Berg, New York, 2005).

- Dietrich, O. & Dietrich, L. Rituals and feasting as incentives for cooperative action at Early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, in Alcohol and Humans: A Long and Social Affair (eds Kimberley J. Hockings & Robin Dunbar) 93-114 (Oxford University Press, 2020).

- McGovern, P. E., Fleming, S. J. & Katz, S. H. eds. The Origins and Ancient History of Wine. (Gordon and Breach, Amsterdam, 1995).

- McGovern, P. E. et al. Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101, 17593-17598 (2004).

- Michel, R. H., McGovern, P. E. & Badler, V. R. The first wine and beer: chemical detection of ancient fermented beverages. Analytical Chemistry 65, 408-413 (1993).

- Braidwood, R. et al. Symposium: Did man once live by beer alone? American Anthropologist 55, 515–526 (1953).

- Hayden, B., Canuel, N. & Shanse, J. What was brewing in the Natufian? An archaeological assessment of brewing technology in the Epipaleolithic. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 20, 102-150 (2013).

- Neubauer, S., Hublin, J. J. & Gunz, P. The evolution of modern human brain shape. Sci Adv 4, eaao5961 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, M. The adaptive origins of uniquely human sociality. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 375, 20190493 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, R. Feasting and its role in human community formation, in Alcohol and Humans: A Long and Social Affair (eds Kimberley J. Hockings & Robin Dunbar) 163-177 (Oxford University Press, 2020).

- Dunbar, R. I. M. et al. Functional benefits of (modest) alcohol consumption. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology 3, 118-133 (2017).

- Bowland, A. C. et al. Wild chimpanzees share fermented fruits. Current Biology 35, R273–R280 (2025).

- Dietler, M. Theorizing the feast: rituals of consumption, commensal politics, and power in African contexts, in Feasts: Archaeological and Ethnographic Perspectives on Food, Politics, and Power (eds Michael Dietler & Brian Hayden) 65-114 (Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001).

- Dietler, M. & Hayden, B. eds. Feasts: Archaeological and Ethnographic Perspectives on Food, Politics, and Power. (Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C., 2001).

- Hayden, B. The Power of Feasts: From Prehistory to the Present. (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- Hornsey, I. S. Alcohol and its Role in the Evolution of Human Society. (RSC Publishing, 2012).

- Cui, C. & Koob, G. F. Titrating tipsy targets: the neurobiology of low-dose alcohol. Trends Pharmacol Sci 38, 556-568 (2017). PMID: 28372826; PMCID: PMC5597438. [CrossRef]

- Pohorecky, L. A. Biphasic action of ethanol. Biobehavioral Reviews 1, 231-240 (1977). [CrossRef]

- Hendler, R. A., Ramchandani, V. A., Gilman, J. & Hommer, D. W. Stimulant and sedative effects of alcohol. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 13, 489-509 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Di Castelnuovo, A. et al., Alcohol dosing and total mortality in men and women: an updated meta-analysis of 34 prospective studies. Archives of Internal Medicine 166, 2437-2445 (2006).

- Harris, R. A., Trudell, J. R. & Mihic, S. J. Ethanol’s molecular targets. Sci Signal 1, re7 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Harrison, N. L. et al. Effects of acute alcohol on excitability in the CNS. Neuropharmacology 122, 36-45 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Abrahao, K. P., Salinas, A. G. & Lovinger, D. M. Alcohol and the Brain: Neuronal Molecular Targets, Synapses, and Circuits. Neuron 96, 1223-1238 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Cowan, C. W. & Watson, P. J. eds. The Origins of Agriculture: An International Perspective. (University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, AL, 2006).

- Tawa, E. A., Hall, S. D. & Lohoff, F. W. Overview of the Genetics of Alcohol Use Disorder. Alcohol Alcohol 51, 507-514 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Edenberg, H. J. & McClintick, J. N. Alcohol Dehydrogenases, Aldehyde Dehydrogenases, and Alcohol Use Disorders: A Critical Review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 42, 2281-2297 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Heit, C. et al. The role of CYP2E1 in alcohol metabolism and sensitivity in the central nervous system. Subcell Biochem 67, 235-247 (2013). PMID: 23400924; PMCID: PMC4314297. [CrossRef]

- Gross, E. R. et al. A personalized medicine approach for Asian Americans with the aldehyde dehydrogenase 2*2 variant. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 55, 107-127 (2015).

- Weiner, H. & Ardelt, B. Distribution and properties of aldehyde dehydrogenase in regions of rat brain. J Neurochem 42, 109-115 (1984). [CrossRef]

- Jin, S. et al. Brain ethanol metabolism by astrocytic ALDH2 drives the behavioural effects of ethanol intoxication. Nat Metab 3, 337-351 (2021). PMID: 33758417; PMCID: PMC8294184. [CrossRef]

- Deza-Ponzio, R., Herrera, M. L., Bellini, M. J., Virgolini, M. B. & Herenu, C. B. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 in the spotlight: The link between mitochondria and neurodegeneration. Neurotoxicology 68, 19-24 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Picklo, M. J., Olson, S. J., Markesbery, W. R. & Montine, T. J. Expression and activities of aldo-keto oxidoreductases in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 60, 686-695 (2001). PMID: 11444797. [CrossRef]

- Jin, S. et al. Spinal astrocyte aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 mediates ethanol metabolism and analgesia in mice. Br J Anaesth 127, 296-309 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Faria-Pereira, A. & Morais, V. A. Synapses: The Brain’s Energy-Demanding Sites. Int J Mol Sci 23, 3627 (2022). PMID: 35408993; PMCID: PMC8998888. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. F. & Matschinsky, F. M. Ethanol metabolism: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Med Hypotheses 140, 109638 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. et al. Brain Energy Metabolism: Astrocytes in Neurodegenerative Diseases. CNS Neurosci Ther 29, 24-36 (2023). PMID: 36193573; PMCID: PMC9804080. [CrossRef]

- Rae, C. D. et al. Brain energy metabolism: A roadmap for future research. J Neurochem 168, 910-954 (2024). PMID: 38183680; PMCID: PMC11102343. [CrossRef]

- Quertemont, E. & Didone, V. Role of acetaldehyde in mediating the pharmacological and behavioral effects of alcohol. Alcohol Res Health 29, 258-265 (2006).

- Deitrich, R., Zimatkin, S. & Pronko, S. Oxidation of ethanol in the brain and its consequences. Alcohol Res Health 29, 266-273 (2006).

- Correa, M. et al. Piecing together the puzzle of acetaldehyde as a neuroactive agent. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 36, 404-430 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Peana, A. T. et al. Mystic Acetaldehyde: The Never-Ending Story on Alcoholism. Front Behav Neurosci 11, 81 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Chin, R., Chang, S. W. C. & Holmes, A. J. Beyond cortex: The evolution of the human brain. Psychol Rev 130, 285-307 (2023). PMID: 35420848. [CrossRef]

- Janiak, M. C., Pinto, S. L., Duytschaever, G., Carrigan, M. A. & Melin, A. D. Genetic evidence of widespread variation in ethanol metabolism among mammals: revisiting the ‘myth’ of natural intoxication. Biol Lett 16, 20200070 (2020). PMID: 32343936; PMCID: PMC7211468. [CrossRef]

- Tamang, J. P. ed. Microbiology and Health Benefits of Traditional Alcoholic Beverages. (Academic Press, 2025).

- Hrnčíř, V., Chira, A. M. & Gray, R. D. Did alcohol facilitate the evolution of complex societies? Humanities and Socieal Sciences Communications 12, 1091,1-13 (2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).