Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

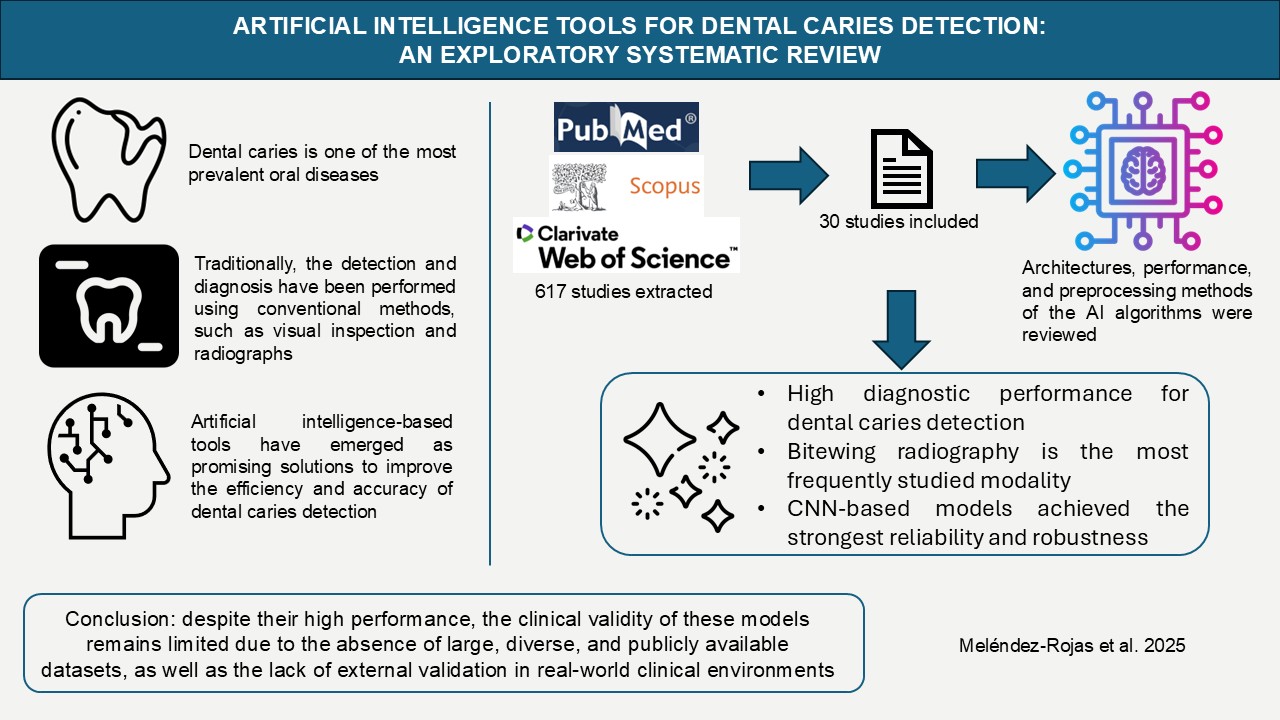

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

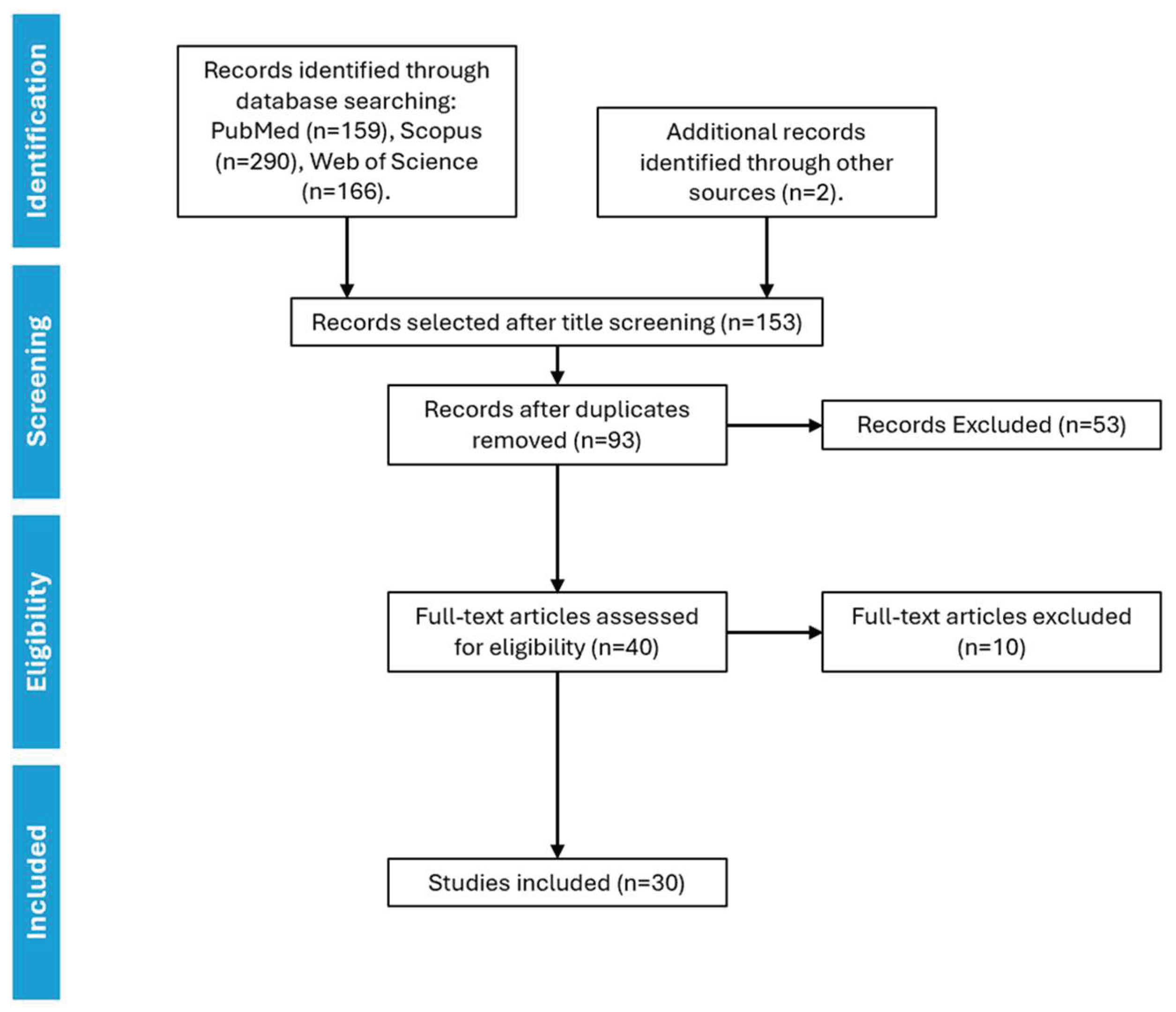

2. Materials and Methods

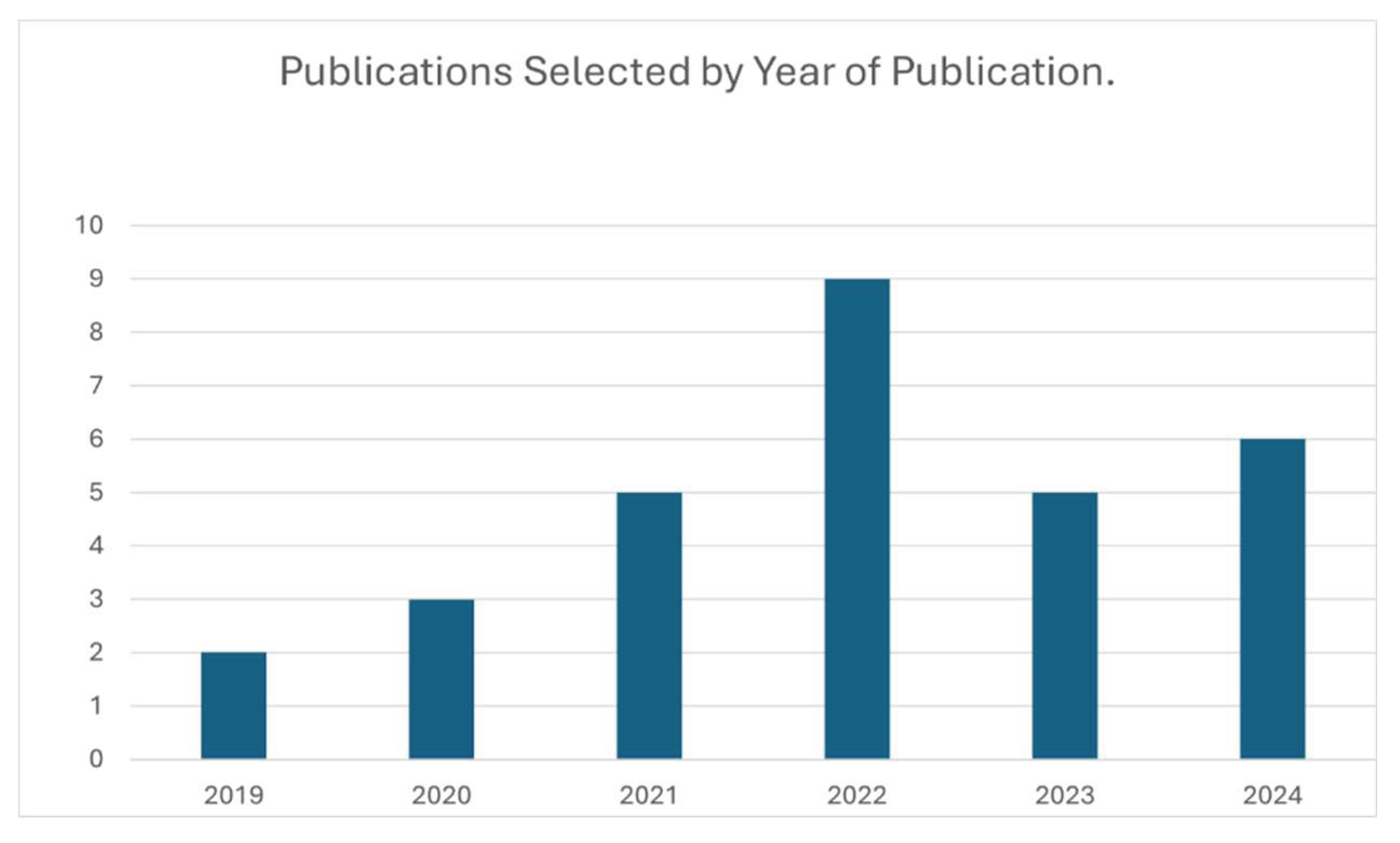

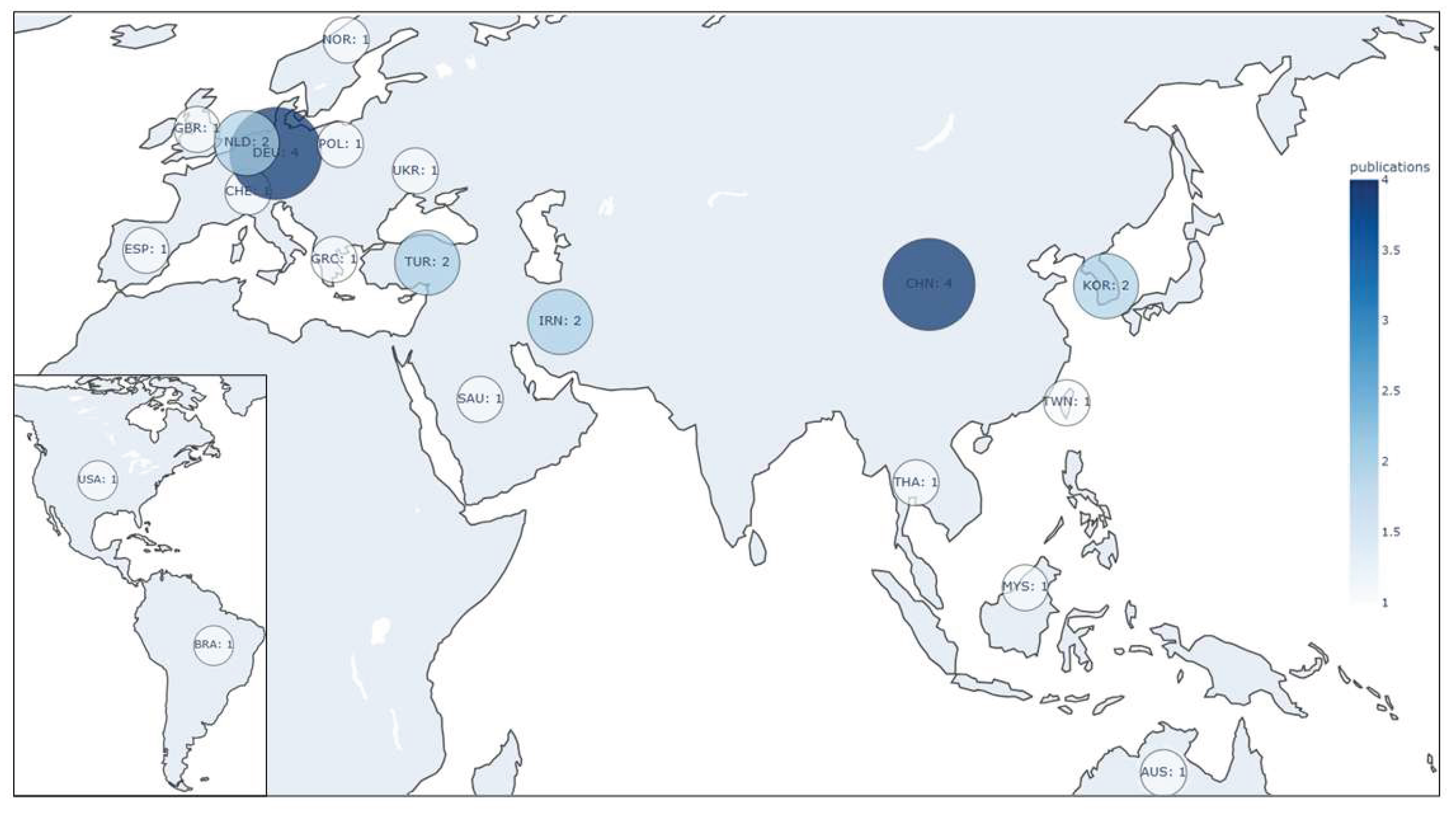

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews |

| WoS | Web of science |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ML | Machine learning |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| MeSH | Medical subject headings |

| TRIPOD-AI | Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis |

| IoU | Intersection over union |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| SE | Sensitivity |

| SP | Specificity |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

| NPV | Negative predictive value |

| NILT | Near-infrared light transillumination |

| TFSNs | Targeted fluorescent nanoparticles |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| CD | Caries detection |

| CBCT | Cone beam computed tomography |

| Micro-CT | Micro computed tomography |

| DL | Deep learning |

References

- Phillips M, Bernabé E, Mustakis A. (2020). Radiographic assessment of proximal surface carious lesion progression in Chilean young adults. Community dentistry and oral epidemiology, 48(5), 409–414. [CrossRef]

- Kühnisch J, Meyer O, Hesenius M, Hickel R, Gruhn V. (2022). Caries Detection on Intraoral Images Using Artificial Intelligence. Journal of dental research, 101(2), 158–165. [CrossRef]

- Chan EK, Wah YY, Lam WY, Chu CH, Yu OY. (2023). Use of Digital Diagnostic Aids for Initial Caries Detection: A Review. Dentistry journal, 11(10), 232. [CrossRef]

- Pérez de Frutos J, Holden Helland R, Desai S, Nymoen LC, Langø T, Remman T, Sen A. (2024). AI-Dentify: deep learning for proximal caries detection on bitewing x-ray - HUNT4 Oral Health Study. BMC oral health, 24(1), 344. [CrossRef]

- Arsiwala-Scheppach LT, Castner NJ, Rohrer C, Mertens S, Kasneci E, Cejudo Grano de Oro JE, Schwendicke F. (2024). Impact of artificial intelligence on dentists’ gaze during caries detection: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of dentistry, 140, 104793. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Xu T, Peng L, Cao Y, Zhao X, Li S, Zhao Y, Meng F, Ding J, Liang S. (2022). Faster-RCNN based intelligent detection and localization of dental caries. Displays. 74. 102201. 10.1016/j.displa.2022.102201.

- García-Cañas Á, Bonfanti-Gris M, Paraíso-Medina S, Martínez-Rus F, Pradíes G. (2022). Diagnosis of Interproximal Caries Lesions in Bitewing Radiographs Using a Deep Convolutional Neural Network-Based Software. Caries research, 56(5-6), 503–511. [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke F, Mertens S, Cantu AG, Chaurasia A, Meyer-Lueckel H, Krois J. (2022). Cost-effectiveness of AI for caries detection: randomized trial. Journal of dentistry, 119, 104080. [CrossRef]

- Panyarak W, Wantanajittikul K, Suttapak W, Charuakkra A, Prapayasatok S. (2023). Feasibility of deep learning for dental caries classification in bitewing radiographs based on the ICCMS™ radiographic scoring system. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology, 135(2), 272–281. [CrossRef]

- Moutselos K, Berdouses E, Oulis C, Maglogiannis I. (2019). Recognizing Occlusal Caries in Dental Intraoral Images Using Deep Learning. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual International Conference, 2019, 1617–1620. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilyfard R, Bonyadifard H, Paknahad M. (2024). Dental Caries Detection and Classification in CBCT Images Using Deep Learning. International dental journal, 74(2), 328–334. [CrossRef]

- Chaves ET, Vinayahalingam S, van Nistelrooij N, Xi T, Romero VHD, Flügge T, Saker H, Kim A, Lima GDS, Loomans B, Huysmans MC, Mendes FM, Cenci MS. (2024). Detection of caries around restorations on bitewings using deep learning. Journal of dentistry, 143, 104886. [CrossRef]

- Cantu AG, Gehrung S, Krois J, Chaurasia A, Rossi JG, Gaudin R, Elhennawy K, Schwendicke F. (2020). Detecting caries lesions of different radiographic extension on bitewings using deep learning. Journal of dentistry, 100, 103425. [CrossRef]

- Collins GS, Moons KGM, Dhiman P, Riley RD, Beam AL, Van Calster B, Ghassemi M, Liu X, Reitsma JB, van Smeden M, Boulesteix AL, Camaradou JC, Celi LA, Denaxas S, Denniston AK, Glocker B, Golub RM, Harvey H, Heinze G, Hoffman MM, et al. (2024). TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 385, e078378. [CrossRef]

- Basri KN, Yazid F, Mohd Zain MN, Md Yusof Z, Abdul Rani R, Zoolfakar AS. (2024). Artificial neural network and convolutional neural network for prediction of dental caries. Spectrochimica acta. Part A, Molecular and biomolecular spectroscopy, 312, 124063. [CrossRef]

- Qayyum A, Tahir A, Butt MA, Luke A, Abbas HT, Qadir J, Arshad K, Assaleh K, Imran MA, Abbasi QH. (2023). Dental caries detection using a semi-supervised learning approach. Scientific reports, 13(1), 749. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X, Yu G, Yin Q, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Sun J. (2022). Context Aware Convolutional Neural Network for Children Caries Diagnosis on Dental Panoramic Radiographs. Computational and mathematical methods in medicine, 2022, 6029245. [CrossRef]

- Dayı B, Üzen H, Çiçek İB, Duman ŞB. (2023). A Novel Deep Learning-Based Approach for Segmentation of Different Type Caries Lesions on Panoramic Radiographs. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland), 13(2), 202. [CrossRef]

- Vinayahalingam S, Kempers S, Limon L, Deibel D, Maal T, Hanisch M, Bergé S, Xi T. (2021). Classification of caries in third molars on panoramic radiographs using deep learning. Scientific reports, 11(1), 12609. [CrossRef]

- Holtkamp A, Elhennawy K, Cejudo Grano de Oro JE, Krois J, Paris S, Schwendicke F. (2021). Generalizability of Deep Learning Models for Caries Detection in Near-Infrared Light Transillumination Images. Journal of clinical medicine, 10(5), 961. [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke F, Elhennawy K, Paris S, Friebertshäuser P, Krois J. (2020). Deep learning for caries lesion detection in near-infrared light transillumination images: A pilot study. Journal of dentistry, 92, 103260. [CrossRef]

- Casalegno F, Newton T, Daher R, Abdelaziz M, Lodi-Rizzini A, Schürmann F, Krejci I, Markram H. (2019). Caries Detection with Near-Infrared Transillumination Using Deep Learning. Journal of dental research, 98(11), 1227–1233. [CrossRef]

- Udod OA, Voronina HS, Ivchenkova OY. (2020). Application of neural network technologies in the dental caries forecast. Wiadomosci lekarskie (Warsaw, Poland : 1960), 73(7), 1499–1504.

- Ahmed W, Azhari A, Fawaz K, Ahmed H, Alsadah Z, Majumdar A, Carvalho R. (2023). Artificial intelligence in the detection and classification of dental caries. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 133. 10.1016/j.prosdent.2023.07.013.

- Baydar O, Różyło-Kalinowska I, Futyma-Gąbka K, Sağlam H. (2023). The U-Net Approaches to Evaluation of Dental Bite-Wing Radiographs: An Artificial Intelligence Study. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland), 13(3), 453. [CrossRef]

- Mao YC, Chen TY, Chou HS, Lin SY, Liu SY, Chen YA, Liu YL, Chen CA, Huang YC, Chen SL, Li CW, Abu PAR, Chiang WY. (2021). Caries and Restoration Detection Using Bitewing Film Based on Transfer Learning with CNNs. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 21(13), 4613. [CrossRef]

- ForouzeshFar P, Safaei AA, Ghaderi F, Hashemikamangar SS. (2024). Dental Caries diagnosis from bitewing images using convolutional neural networks. BMC oral health, 24(1), 211. [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar Y, Ayan E. (2022). Diagnosis of interproximal caries lesions with deep convolutional neural network in digital bitewing radiographs. Clinical oral investigations, 26(1), 623–632. [CrossRef]

- Estai M, Tennant M, Gebauer D, Brostek A, Vignarajan J, Mehdizadeh M, Saha S. (2022). Evaluation of a deep learning system for automatic detection of proximal surface dental caries on bitewing radiographs. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology, 134(2), 262–270. [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke F, Rossi JG, Göstemeyer G, Elhennawy K, Cantu AG, Gaudin R, Chaurasia A, Gehrung S, Krois J. (2021). Cost-effectiveness of Artificial Intelligence for Proximal Caries Detection. Journal of dental research, 100(4), 369–376. [CrossRef]

- Arsiwala-Scheppach LT, Castner NJ, Rohrer C, Mertens S, Kasneci E, Cejudo Grano de Oro JE, Schwendicke F. (2024). Impact of artificial intelligence on dentists’ gaze during caries detection: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Dentistry, 140, 104793. [CrossRef]

- Amasya H, Alkhader M, Serindere G, Futyma-Gąbka K, Aktuna Belgin C, Gusarev M, Ezhov M, Różyło-Kalinowska I, Önder M, Sanders A, Costa ALF, Castro Lopes SLP, Orhan K. (2023). Evaluation of a Decision Support System Developed with Deep Learning Approach for Detecting Dental Caries with Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Imaging. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland), 13(22), 3471. [CrossRef]

- Lee S, Oh SI, Jo J, Kang S, Shin Y, Park JW. (2021). Deep learning for early dental caries detection in bitewing radiographs. Scientific reports, 11(1), 16807. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J, Chen Z, Zhao J, Yu Y, Li X, Shi K, Zhang F, Yu F, Shi K, Sun Z, Lin N, Zheng Y. (2023). Artificial intelligence in the diagnosis of dental diseases on panoramic radiographs: a preliminary study. BMC oral health, 23(1), 358. [CrossRef]

- Amasya H, Alkhader M, Serindere G, Futyma-Gąbka K, Aktuna Belgin C, Gusarev M, Ezhov M, Różyło-Kalinowska I, Önder M, Sanders A, Ferreira Costa AL, Pereira de Castro Lopes SL, Orhan K. (2023). Evaluation of a decision support system developed with deep learning approach for detecting dental caries with cone-beam computed tomography imaging. Diagnostics, 13(22), 3471. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad-Rahimi H, Motamedian SR, Rohban MH, Krois J, Uribe SE, Mahmoudinia E, Rokhshad R, Nadimi M, Schwendicke F. (2022). Deep learning for caries detection: A systematic review. Journal of Dentistry, 122, 104115. [CrossRef]

- Yoon K, Jeong HM, Kim JW, Park JH, Choi J. (2024). AI-based dental caries and tooth number detection in intraoral photos: Model development and performance evaluation. Journal of dentistry, 141, 104821. [CrossRef]

- Jones KA, Jones N, Tenuta LMA, Bloembergen W, Flannagan SE, González-Cabezas C, Clarkson B, Pan LC, Lahann J, Bloembergen S. (2022). Convolution Neural Networks and Targeted Fluorescent Nanoparticles to Detect and ICDAS Score Caries. Caries research, 56(4), 419–428. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Guo J, Ye J, Zhang M, Liang Y. (2022). Detection of Proximal Caries Lesions on Bitewing Radiographs Using Deep Learning Method. Caries research, 56(5-6), 455–463. [CrossRef]

- Moran M, Faria M, Giraldi G, Bastos L, Oliveira L, Conci A. (2021). Classification of Approximal Caries in Bitewing Radiographs Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 21(15), 5192. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Liang Y, Li W, Liu C, Gu D, Sun W, Miao L. (2022). Development and evaluation of deep learning for screening dental caries from oral photographs. Oral diseases, 28(1), 173–181. [CrossRef]

- Park EY, Cho H, Kang S, Jeong S, Kim EK. (2022). Caries detection with tooth surface segmentation on intraoral photographic images using deep learning. BMC oral health, 22(1), 573. [CrossRef]

| Year | Reference | Country | Sample | Sample Size | Examiners | Preprocessing | Network architecture | Metrics | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | Casalegno F et al. [22] | Switzerland | Infrared transillumination | 217 images | - | Images scaled to 256 × 320 pixels. Data augmentation techniques such as flipping, zoom, rotation, translation, and contrast and brightness adjustment | U-Net + VGG16 | Intersection-over-union (IoU) (mean) | 0.73 |

| IoU proximal | 0.50 | ||||||||

| IoU occlusal | 0.49 | ||||||||

| Area under the curve (AUC) proximal | 0.86 | ||||||||

| AUC occlusal | 0.84 | ||||||||

| 2019 | Moutselos K et al. [10] | Greece | Intraoral photograph | 88 photographs | 2 examiners | Superpixel segmentation for image annotation | Mask R-CNN (based on Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) and ResNet101) | Accuracy (super pixels) (mean) | 0.64 |

| Accuracy (whole image) (mean) | 0.78 | ||||||||

| 2020 | Cantu AG et al. [13] | Germany | Bitewing X-ray | 3686 X-rays | 4 examiners | Images cropped to 512 × 416 pixels. Transformations such as flipping, central cropping, translation, and rotation were applied, as well as contrast and brightness adjustments | U-Net | Accuracy | 0.80 |

| Sensitivity (SE) | 0.75 | ||||||||

| Specificity (SP) | 0.83 | ||||||||

| Positive predictive value (PPV) | 0.70 | ||||||||

| Negative predictive value (NPV) | 0.86 | ||||||||

| F1-score | 0.73 | ||||||||

| 2020 | Schwendicke F et al. [21] | Germany | Near-infrared light transillumination (NILT) | 226 extracted human teeth | 3 examiners | Images cropped to 224 × 224 pixels. Data augmentation was applied, including resizing, random rotations, and horizontal and vertical flipping. | Resnet18, Resnext50 | AUC | 0.74 |

| Accuracy | 0.69 | ||||||||

| SE | 0.59 | ||||||||

| SP | 0.85 | ||||||||

| PPV | 0.71 | ||||||||

| NPV | 0.73 | ||||||||

| 2020 | Udod OA et al. [23] | Ukraine | Clinical data and biomarkers | 73 patients | - | Patient data were read and normalized using the Pandas library, and one-hot encoding was applied to handle discrete categories | Custom Neural Network | Accuracy | 0.84 |

| 2021 | Bayraktar Y et al. [28] | Turkey | Bitewing X-ray | 1,000 X-rays | 2 examiners | Images cropped to 640 × 480 pixels, and data augmentation was performed through rotation, scaling, zoom, and cropping | DarkNet-53 | Accuracy | 0.95 |

| SE | 0.72 | ||||||||

| SP | 0.98 | ||||||||

| PPV | 0.87 | ||||||||

| NPV | 0.96 | ||||||||

| AUC | 0.87 | ||||||||

| 2021 | Holtkamp A et al. [20] | Germany | NILT | 226 extracted human teeth. 1319 teeth | 4 examiners | Images segmented by tooth, and data augmentation techniques such as random rotations, vertical and horizontal flipping, shifting, and zoom were applied. Images cropped to 224 × 224 pixels. | ResNet | Accuracy (in-vivo train and test) | 0.78 |

| Accuracy (in-vitro train and test) | 0.64 | ||||||||

| 2021 | Mao YC et al. [26] | Taiwan | Bitewing X-ray | 278 X-rays | 3 examiners | Gaussian filtering, Otsu thresholding, horizontal and vertical projection for tooth segmentation, zoom, rotation, translation, contrast and brightness | AlexNet | Accuracy | 0.90 |

| 2021 | Moran M et al. [40] | Brazil | Bitewing X-ray | 112 X-rays | 1 oral and maxillofacial radiologist (OMR) | Adaptive histogram equalization, Otsu thresholding, and morphological operations to improve quality of segmentation, and were cropped to obtain individual images of each tooth | ResNet, Inception | Best Accuracy (Inception) (0.001 learning rate) | 0.73 |

| 2021 | Vinayahalingam S et al. [19] | Netherlands | Panoramic X-ray | 400 X-rays | 2 examiners | Images cropped to 256 × 256 pixels around the third molar and subjected to histogram equalization and data augmentation techniques such as rotation and flipping | MobileNet V2 | Accuracy | 0.87 |

| SE | 0.86 | ||||||||

| SP | 0.88 | ||||||||

| PPV | 0.88 | ||||||||

| NPV | 0.86 | ||||||||

| F1-score | 0.86 | ||||||||

| AUC | 0.90 | ||||||||

| 2022 | Chen X et al. [39] | China | Bitewing X-ray | 978 X-rays | 2 examiners. 1 OMR | Imagens scaled to 800 pixels on shorter side, and random transformations such as flipping, central cropping, rotation, Gaussian blur, sharpening, and contrast and brightness adjustment | Faster R-CNN | Accuracy | 0.87 |

| SE | 0.72 | ||||||||

| SP | 0.93 | ||||||||

| PPV | 0.77 | ||||||||

| NPV | 0.91 | ||||||||

| F1-score | 0.74 | ||||||||

| 2022 | Estai M et al. [29] | Australia | Bitewing X-ray | 2468 X-rays | 3 examiners | Images cropped to 640 × 480 pixels to train Faster R-CNN model. The detected regions of interest (ROI) were cropped and resized to 299 × 299 pixels to train Inception-ResNet-v2 network | Faster R-CNN, VGG-16 | SE | 0.89 |

| Precision | 0.86 | ||||||||

| SP | 0.86 | ||||||||

| Accuracy | 0.87 | ||||||||

| F1-score | 0.87 | ||||||||

| 2022 | García-Cañas Á et al. [7] | Spain | Bitewing X-ray | 300 X-rays | 2 examiners | Radiographs were processed using the Denti.Ai software | Faster R-CNN, VGG-16 | Accuracy | 0.86 |

| SE | 0.87 | ||||||||

| SP | 0.99 | ||||||||

| PPV | 0.89 | ||||||||

| NPV | 0.95 | ||||||||

| AUC | 0.77 | ||||||||

| 2022 | Jones KA et al. [38] | United States | Targeted fluorescent nanoparticles (TFSNs) | 130 extracted human teeth | 1 examiner | Removal of black background pixels through cropping, resizing images to 299 × 299 pixels, fluorescence extraction | U-Net, NASNet | SE | 0.80 |

| PPV | 0.76 | ||||||||

| 2022 | Kühnisch J et al. [2] | Germany | Intraoral photograph | 2,417 photographs | 1 examiner | Cropping of the images. Exclusion of photographs with non-carious hard tissue defects and blurred images | MobileNetV2. | Accuracy caries detection (CD) | 0.93 |

| SE (CD) | 0.90 | ||||||||

| SP (CD) | 0.94 | ||||||||

| AUC (CD) | 0.96 | ||||||||

| 2022 | Park EY et al. [42] | South Korea | Intraoral photograph | 2348 photographs | 1 examiner | Images were segmented to identify dental surfaces using U-Net. Data augmentation techniques such as image mirroring, shifting, and blurring were applied | U-Net, ResNet-18, Faster R-CNN | AUC | 0.84 |

| Accuracy | 0.81 | ||||||||

| SE | 0.74 | ||||||||

| SP | 0.89 | ||||||||

| Precision | 0.87 | ||||||||

| 2022 | Zhang X et al. [41] | China | Intraoral photograph | 3,932 photogrpahs | 3 examiners | Images cropped to 300 × 300 pixels and underwent data augmentation that included shifting, cropping, scaling, rotation, and changes in image hue, saturation, and exposure | VGG-16 | AUC | 0.86 |

| image-wise SE | 0.82 | ||||||||

| box-wise SE | 0.65 | ||||||||

| 2022 | Zhou X et al. [17] | China | Panoramic X-ray | 304 X-rays | - | Individual teeth were extracted from X-rays using annotation tools, and images were resized | ResNet18 | Accuracy | 0.83 |

| Precision | 0.85 | ||||||||

| SE | 0.88 | ||||||||

| F1-score | 0.87 | ||||||||

| AUC | 0.90 | ||||||||

| 2022 | Zhu Y et al. [6] | China | Dental X-ray | 200 X-rays | - | Images adjusted to a uniform size and subjected to data augmentation techniques such as random changes in brightness, contrast, and horizontal flipping | Faster R-CNN | Precision (mean) | 0.74 |

| F1-score | 0.68 | ||||||||

| Image time detection | 0.19 s.. | ||||||||

| 2023 | Ahmed W et al. [24] | Saudi Arabia | Bitewing X-ray | 554 X-rays | 2 examiners | Images converted to JPEG format and resized to 512x512 pixels. Brightness and contrast enhancement | U-Net | IoU (mean) | 0.55 |

| F1-score (mean) | 0.54 | ||||||||

| 2023 | Baydar O et al. [25] | Poland | Bitewing X-ray | 500 X-rays | 1 examiner. 1 OMR | Identification and segmentation with CranioCatch | U-Net | SE | 0.82 |

| Accuracy | 0.95 | ||||||||

| F1-score | 0.88 | ||||||||

| 2023 | Dayı B et al. [18] | Turkey | Panoramic X-ray | 504 X-rays | 1 examiner. 1 OMR | Images cropped to 540 × 1300 pixels to focus on the teeth, and then reduced to 256 × 512 pixels for processing | DCDNet | Precision | 0.72 |

| SE | 0.70 | ||||||||

| F1-score | 0.71 | ||||||||

| 2023 | Panyarak W et al. [9] | Thailand | Bitewing X-ray | 2758 X-rays | 3 OMR | Random movements in vertical and horizontal directions, and random rotation of ±15 degrees | ResNet | Accuracy | 0.71 |

| SE | 0.83 | ||||||||

| SP | 0.57 | ||||||||

| Classification error | 0.25 | ||||||||

| 2023 | Qayyum A et al. [16]. | United Kingdom | Dental X-ray | 229 X-rays | 1 team supervised by 1 OMR | Centered cropping of caries regions in the images. Horizontal flipping, rotation | Deeplabv3 | Accuracy (mean) | 0.99 |

| IoU (mean) | 0.51 | ||||||||

| DICE score | 0.50 | ||||||||

| 2024 | Basri KN et al. [15] | Malaysia | Ultraviolet (UV) absorption spectroscopy | 102 saliva spectra | - | Centering measure (CM), auto-scaling (AS), and Savitzky-Golay (SG) smoothing | ANN, CNN | Accuracy (ANN) | 0.85 |

| Precision (ANN) | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Accuracy (CNN + smooth SG) | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Precision (CNN + smooth SG) | 1.0 | ||||||||

| 2024 | Chaves ET et al. [12] | Netherlands | Bitewing X-ray | 425 X-rays | 7 examiners | Data augmentation was used, including random horizontal flipping, resizing, and cropping | Mask R-CNN | AUC primary caries detection | 0.81 |

| AUC secondary caries detection | 0.80 | ||||||||

| F1-score primary caries detection | 0.69 | ||||||||

| F1-score secondary caries detection | 0.72 | ||||||||

| 2024 | Esmaeilyfard R et al. [11] | Iran | Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) | 785 CBCT | 2 OMR | Vertical and horizontal flipping, random rotations of 20°, magnification up to 2x. Cropping and splitting in three views, resizing to 96x160 pixels | Deep CNN with multiple inputs | Accuracy | 0.95 |

| SE | 0.92 | ||||||||

| SP | 0.96 | ||||||||

| F1-score | 0.93 | ||||||||

| 2024 | ForouzeshFar P et al. [27] | Iran | Bitewing X-ray | 713 X-rays | - | Images cropped into smaller images with a single tooth and resized to 100 × 100 pixels. Images were rotated and aligned to separate upper and lower teeth | VGG16, VGG19, AlexNet, ResNet50 | Accuracy | 0.94 |

| Precision | 0.93 | ||||||||

| SE | 0.95 | ||||||||

| SP | 0.97 | ||||||||

| F1-score | 0.93 | ||||||||

| 2024 | Pérez de Frutos J et al. [4] | Norway | Bitewing X-ray | 13,887 X-rays | 6 examiners | The images underwent intensity standardization in the range (0, 1), and data augmentation was applied, such as horizontal and vertical flipping with a probability of 50% | RetinaNet (ResNet50), YOLOv5, EficcientNet | Precision (mean) | 0.65 |

| F1-score | 0.55 | ||||||||

| False negative rate (FNR) (mean) | 0.15 | ||||||||

| 2024 | Yoon K et al. [37] | South Korea | Intraoral photograph | 24,578 photographs | 20 labelers. 3 examiners | Data augmentation techniques, resizing, random flipping, photometric distortion, and cut-out | Cascade Region-Based Deep CNN (R-CNN) | SE | 0.73 |

| SP | 0.97 | ||||||||

| Accuracy | 0.95 | ||||||||

| AUC | 0.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).