1. Introduction

The remarkable success of large language models (LLMs) is widely attributed to their strong capability for zero-shot generalization. This success has inspired a surge of interest in building foundation models for computer vision, where the ability to generalize to unseen domains and tasks is equally crucial [

1,

2,

3]. Among these, the Segment Anything Model (SAM) [

4] represents a milestone in promptable image segmentation. Trained on billions of annotated masks from the SA-1B dataset, SAM exhibits impressive zero-shot capabilities across a wide range of scenarios.

However, despite its unprecedented scale and broad applicability, SAM can behave unexpectedly in challenging out-of-distribution (OOD) settings, such as camouflaged object segmentation, medical image segmentation, adversarial perturbations, and visual corruptions [

5,

6]. These failures are largely driven by distribution shifts between the web-scale pre-training data and specialized, often more complex, target domains encountered in real-world deployments. Such observations motivate us to explore computationally feasible ways to adapt SAM for improved robustness and generalization to diverse downstream segmentation tasks.

Traditional paradigm towards improving model robustness and generalization often involves costly re-training. Methods are frequently customized to combat specific domain shifts. For example, domain randomization was developed to improve generalization across real testing domains [

7], while adversarial training is commonly used to enhance robustness against attacks [

8]. Applying these techniques to large foundation model is nonetheless impractical due to the enormous computing resources required for training the model on the web-scale training data. Therefore, instead of re-training the model, we opt for a more computation friendly paradigm by adapting or finetuning a pre-trained foundation model to downstream dataset.

We specify three major challenges when adapting pre-trained foundation model to a new data distribution. First, traditional unsupervised domain adaptation [

9] paradigm requires access to both source and target datasets which may not be feasible due to privacy issue and computation cost [

10]. Second, updating all model weights for adaptation is often superior in performance, however, is constrained by the prohibitive storage cost due to the large model size [

11] and may risk overfitting [

12]. Finally, both weakly-supervised and unsupervised adaptation remain challenging due to the limited or absent label information in the target domain, which can lead to error accumulation and sub-optimal adaptation [

13,

14,

15].

To tackle the above challenges, we propose a self-training based adaptation approach to synergize the exploitation of weak supervision and unlabeled data on target domain as shown in

Figure 1. Specifically, we first alleviate the dependence on source domain data by adopting a self-training based source-free domain adaptation strategy. This approach first make segmentation predictions, a.k.a. pseudo labels, on the target domain data. The pseudo labels are used for supervising the update of segmentation model.

As self-training is fragile due to incorrect pseudo labels, a.k.a. confirmation bias [

16], we introduce a frozen source model as the anchor network to regularize the update of segmentation model in our conference paper WeSAM [

17]. We further enhance this regularization by applying patch-level contrastive learning between the anchor and target models, which helps mitigate the effect of noisy pseudo labels. Furthermore, we introduce a masked image modeling (MIM) strategy that replaces masked regions in the student features with teacher-derived embeddings and employs semantic decoder regularization. This design enforces fine-grained alignment between branches, improving feature consistency and robustness to label noise and domain shift. To further mitigate the high computation cost of updating the full model weights, we apply a low-rank weight decomposition to encoder weights and the backpropagation flows through the low-rank shortcut only.

Our framework is applicable to both unsupervised and weakly-supervised adaptation. In the weakly-supervised setting, we leverage available weak annotations (e.g., sparse point-wise, bounding boxes, or coarse masks) on the target domain. In the unsupervised setting, we design a data pipeline that automatically generates weak labels for target images, enabling adaptation without manual annotation. These weak supervisions are naturally compatible with the prompt encoder within SAM, enabling more localized and less ambiguous pseudo predictions for self-training. The adapted model demonstrates much stronger generalization capability on multiple downstream tasks.

We summarize the contributions of this work as follows.

We are motivated by the generalization issue of segment anything model to diverse downstream segmentation tasks and propose a task-agnostic solution to adapt SAM through self-training with no access to source dataset.

In addition to the conference version, to enhance adaptation robustness, we apply patch-level contrastive regularization to align features and use masked image modeling to improve representation learning during self-training.

Improved from the conference version, we develop a unified adaptation framework for both unsupervised and weakly-supervised settings, where all weak supervisions are seamlessly integrated into the prompt encoder of SAM.

We provide comprehensive experimental validation on five downstream segmentation tasks across four different segmentation scenarios, using both SAM and SAM2 models, which demonstrates the effectiveness of our weakly and unsupervised adaptation approach.

2. Related Work

2.1. Image Segmentation Foundation Model

The success of deep learning is attributed to the increasing size and neural networks and huge amount of training data. Recent successful computer vision models, e.g. image segmentation and object detection, follow a practice of finetuning from encoder network pre-trained on large image dataset, e.g. ImageNet [

18]. Despite achieving impressive results on standard benchmark datasets, e.g. Psacal VOC [

19] and COCO [

20], the zero-shot and few-shot generalization ability is often limited. Inspired by the revolutionizing language/vision-language foundation model pre-trained on web-scale datasets [

3,

21,

22], a new opportunity awaits for developing a generalizable vision foundation model. This motivates the emergence of vision foundation model pre-trained on huge dataset. SAM [

4] and DINO v2 [

2], to name a few. Among these foundation models, SAM stands out for its ability to enable zero-shot segmentation using prompt engineering. Therefore, we pay particular attention to SAM in this work. Since the inception of SAM, numerous attempts are made to validate the robustness of SAM under more challenging scenarios, such as medical images [

23] [

24], camouflaged objects [

25], glass (transparent objects and mirrors) [

26] and pose estimation [

27]. Despite these early attempts to discover the weakness, there are very few matured solutions [

5] to improve the generalization of SAM to challenging downstream tasks. In this work, we aim to fill this gap by proposing principled solutions to enhance the robustness of SAM against downstream tasks subject to significant distribution shift.

2.2. Source-Free Domain Adaptation

Unsupervised Domain Adaptation (UDA)[

9,

28,

29,

30,

31] has emerged as a means to address the domain shift between source training data and target testing data. This enables models to be trained on cost-effective and easily annotated data, facilitating the transfer to more valuable but challenging-to-label datasets. However, UDA methods face limitations when source domain data is inaccessible due to privacy concerns or storage constraints. In response to this, Source-Free Domain Adaptation (SFDA)[

10,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36] has been proposed to reduce the reliance on source data in domain adaptation (DA) methods. SHOT [

10] represents an early effort to alleviate domain shift without access to source data, achieved through self-training on unlabeled target data. Numerous prior works [

1,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42] have explored the effectiveness of a teacher-student like self-training architecture in domain shift mitigation. The similar self-training framework [

43] simultaneously trains on multiple sets of augmented data, utilizing teacher-student cycle consistency for mutual learning of the two networks. Other methods generate source-like samples [

44,

45,

46], construct intermediate domains [

35,

47], or perturb target domains [

48,

49,

50,

51] to enhance model generalization. Recent approaches [

45,

52] leverage contrast loss between target samples and source domain prototypes. Recent attempts to source-free domain adaptation for image segmentation aims to minimize feature discrepancy between source and target domains [

46,

53,

54]. In this work, we aim to adapt SAM to downstream tasks without accessing to the source domain data to avoid the high computation overhead and potential privacy issues for foundation models to be released in the future

2.3. Weakly Supervised Domain Adaptive Segmentation

Unsupervised domain adaptation often follows a self-training paradigm [

10], which is limited by the quality of pseudo labels. Instead of relying on the pseudo predictions, weakly supervised domain adaptive semantic segmentation (WDASS) exploits limited weak supervisions in the form of bounding box, points or coarse segmentation masks [

55,

56,

57,

58]. Among these works, [

55] employs both image and point labels, suggesting an adversarial alignment of features at the pixel level to address WDASS. In contrast, [

56] relies on bounding boxes as weak labels and employs adversarial learning to achieve domain-invariant features. Additionally, [

57] utilizes self-training and a boundary loss to enhance performance in WDASS with coarse labels. More recently, [

58] utilizes weak label for aligning the source-target features and outperforms previous methods to achieve competitive performance compared to supervised learning. We observe that the common weak supervisions are inherently compatible with the SAM model as prompt input. Therefore, we propose to adapt SAM with weak supervisions in a seamless way.

2.4. Masked Image Modeling

Self-supervised pretraining methods [

59] have gained considerable attention in computer vision. One prominent approach is contrastive learning [

60,

61,

62], which promotes augmentation invariance by encouraging high similarity between different augmented views of the same image. Although contrastive learning produces representations with desirable properties, such as high linear separability, it relies heavily on strong data augmentations and negative sampling. Another promising direction is masked image modeling (MIM), which aids in learning meaningful representations by reconstructing masked patches of an image. Early MIM approaches leverage denoising autoencoders [

63] and context encoders [

64] to train vision transformers using masked prediction objectives. Numerous works have explored MIM for self-supervised image pretraining. BEiT [

65] was the first to adopt MIM for ViT pretraining by predicting visual tokens. Additionally, MaskFeat [

66] demonstrated that reconstructing local gradient features derived from HOG descriptors can significantly improve visual pretraining. In SimMIM [

67] and MAE [

68], directly reconstructing the pixel values of the masked image patches achieves effective visual representation learning. By leveraging masked image pretraining, SAMI [

69] is able to effectively learn visual representations by reconstructing features from the SAM image encoder. Our approach builds upon MAE and demonstrates that utilizing MAE to reconstruct features from the SAM image encoder enables more efficient adaptation.

3. Methodology

In this section, we present our adaptation framework for the Segment Anything Model (SAM). We first review the main components of SAM. Then, we introduce our self-training based adaptation pipeline, which employs a teacher-student network structure alongside an anchor network. To further enhance domain generalization, we incorporate masked image modeling to improve feature consistency. Moreover, we propose fully automated and weakly-supervised prompt generation strategies to establish reliable correspondences for effective self-training. Finally, we utilize a low-rank weight update approach to enable memory-efficient adaptation of large-scale models.

3.1. Overview of Segment Anything Model

The segment-anything model consists of three major components, the encoder network

, prompt encoder

and mask decoder

. The image encoder is pre-trained using masked autoencoder (MAE) [

68]. The whole SAM model is further fine-tuned on the web-scale labeled training set, SA-1B [

4], with 1.1B labeled masks. A combination of focal loss and dice loss are used for training SAM. During inference, the testing image

x is first encoded by the image encoder

. Given encoded prompts

e, a light-weight mask decoder makes three levels of segmentation predictions. In this work, we are motivated by the challenge of deploying SAM on many downstream tasks and propose to adapt SAM to downstream segmentation tasks with weak supervision without requiring access to source domain training data.

3.2. Source-Free Adaptation as Self-Training

Provided an unlabeled target domain dataset

and the pre-trained encoder network

, we adopt a teacher-student architecture for self-training. As illustrated in

Figure 2, we maintain three encoder networks, namely the anchor network

, the student network

and the teacher network

, where the student and teacher networks share the weights

. For each sample

, we apply one random weak data augmentation

as the input to anchor and teacher networks, and one random strong data augmentation

as the input to student network. Through the three encoder networks, three feature maps are obtained respectively, as

,

and

, where

and

D refers to feature dimension. In the decoder network, given a number

of prompts, e.g. bounding boxes, points or coarse segmentation masks, a set of foreground masks for the instance segmentation results would be deduced,

,

,

, where each mask is then normalized between 0 and 1 by sigmoid function respectively, i.e.

. We further denote a binarized segmentation mask with a threshold of 0.5 as

. Based on these notations, we elaborate three sets of adaptation objectives for self-training purpose.

Teacher-Student Self-Training Loss: We first introduce the Self-Training loss to update student/teacher network. Self-Training is widely used in semi-supervised learning [

70] and recently is demonstrated to be very effective for source-free domain adaptation [

42]. In this work, we continue the idea of self-training in classification task and perform focal loss [

71] and dice loss [

72] for the supervision of student’s outputs with binarized teacher’s predictions as follows, where

controls the focus on hard training pixels and

is a small value to avoid dividing by zero.

Anchored Loss for Robust Regularization: Training the networks with self-training loss alone is vulnerable to the accumulation of incorrect pseudo labels predicted by teacher network, a.k.a. confirmation bias [

16]. Observations are made that the performance will drop after long iterations of self-training alone [

73]. Existing source-free domain adaptation approaches often adopt additional constraints to prevent the negative impact of self-training, e.g. uniform distribution over predictions [

42]. Without making such explicit assumptions, we propose to introduce the regularization by an anchor loss which minimizes the dice loss between an anchor network, which has frozen source model weights, and student and teacher networks respectively in Equation (

3). The frozen anchor network serves as the knowledge inherited from source domain and too much deviation between the source model and self-training updated model is discouraged to prevent the model from collapsing.

Contrastive Learning with Patches: The two training objectives described above operate in the decoder’s output space. As shown in our experiments, updating the encoder is the most effective way to adapt SAM. Therefore, it is crucial to apply regularization directly to the encoder’s feature maps.

To this end, we introduce a patch-level contrastive loss that encourages corresponding regions in two feature maps to be similar, while pushing apart dissimilar regions. This promotes feature consistency at a finer spatial granularity.

Given two

-normalized feature maps

and

from the anchor and student branches, we partition them into non-overlapping

patches using a

patchify operation:

where

are the resulting patch embeddings, and

N is the number of patches per feature map. Each patch embedding is obtained by averaging the feature vectors within that patch, enabling localized similarity comparisons.

We then compute the cosine similarity between all patch pairs from

and

. To emphasize corresponding patches, we scale the similarity scores by a temperature parameter

and define the patch-level contrastive loss as:

where

denotes the cosine similarity between patch

i in

and patch

j in

, and

controls the sharpness of the similarity distribution.

Total Loss: We combine the above three loss functions as the final source-free domain adaptation loss.

Figure 3.

Illustration of contrastive loss between two views.

Figure 3.

Illustration of contrastive loss between two views.

3.3. Masked Image Modeling in Self-Training

We propose a novel masked image modeling (MIM) strategy to bolster domain generalization and robustness in the self-training process for SAM adaptation. Distinct from the conventional MAE [

68] framework, which imputes masked image regions by introducing uninformative learnable mask tokens, our approach leverages semantically meaningful feature embeddings from the teacher branch to fill masked regions in the student branch. Moreover, rather than relying on conventional pixel-level reconstruction as supervision, our method employs a semantic decoder loss to regularize and align the restored features with segmentation objectives, promoting adaptation at the representation level.

During adaptation, the student encoder generates a feature map

, which is randomly masked by a binary matrix

at ratio

r, resulting in

. Unlike previous methods that fill masked positions with learnable tokens, we directly replace masked tokens with the corresponding teacher features, defined as:

where

is the teacher feature map obtained under weak augmentation.

Our approach provides two key advantages over MAE and related methods. First, by mixing teacher tokens into the student feature space, we explicitly encourage the student and teacher representations to converge, leading to fine-grained consistency within the student branch. This design naturally supports the self-training objective: alignment of feature embeddings derived from different sources, rather than only enforcing consistency at the overall branch level. Additionally, this mixed-token strategy mitigates the adverse effects of noisy or low-quality pseudo-labels, particularly for challenging samples, helping prevent the occurrence of overly large discrepancies between branches. Further evidence is presented in GradCAM activation map visualizations for both branches (

Figure 4), which illustrate more focused and consistent feature activations achieved by our method.

To regularize this process, we employ a mask decoder loss that aligns the reconstructed student features with their original teacher counterparts in the semantic space, rather than at the pixel level as in MAE. This loss encourages the restoration of semantically consistent information that directly benefits downstream segmentation objectives, providing stronger representational alignment for domain adaptation.

Empirical results (see

Section 4.9) show that our strategy using teacher features as mask tokens and feature-level semantic regularization significantly surpasses both the MAE baseline [

68] and methods that rely purely on mixing strong/weak augmentations at the image level [

74].

3.4. Prompt Generation for Self-Training

The SAM segmentation requires prompts to disambiguate the granularity of segmentation. The prompt engineering can be implemented in both fully automated way and human interaction.

Fully Automated Prompt for Self-Training: To enable

unsupervised adaptation, we devise a fully automated pipeline for prompt generation and pseudo-label creation, obviating the need for human annotation on the target domain. Given an unlabeled target image, we first densely sample grid points with a spatial distance of 16 pixels as point prompt input. Initial stage segmentation masks

are generated by the anchor network with the grid point prompts. We follow the fully automated segmentation introduced by SAM [

4] to prune out masks with low IoU score and low stability score, followed by NMS suppression. To enable self-training and regularization between different branches, we further generate a fixed set of prompt

from

as input to all three branches. As such, the segmentation outputs

,

and

are of the same length with exact one-to-one correspondence.

Weak Supervision as Prompt: Despite automatic segmentation can be enabled by sampling a grid of point prompts over the image and filtering out low quality and duplicated masks, the quality of segmentation is relatively poor and may contain many false positive predictions, making self-training less effective. Therefore, following prior weakly supervised domain adaptation works [

57], we propose to use three types of weak supervisions, including bounding box, sparse point annotation and coarse segmentation mask. Fortunately, in the context of SAM, these weak supervisions perfect match with the prompt inputs which allow seamless integration of weak supervision for adapting SAM.

3.5. Low-Rank Weights Update

The enormous size of backbone network prohibits updating all model weights with large batchsize. However, many existing studies suggest the update of encoder network weights is an effective way of adapting pre-trained models [

42,

75]. To enable updating the backbone network with larger batchsize, we opt for a computation friendly low-rank updating approach [

11]. For each weight in the encoder network

, we use a low-rank approximation

where

and

with

r indicating the rank. We can achieve a compression rate of

. Only

A and

B are updated via backpropagation during adaptation to reduce memory footprint. At inference stage, the weight is reconstructed by combining the low rank reconstruction and original weight,

.

4. Experiment

In this section, we describe our experimental settings and a broad suite of five downstream segmentation tasks covering domains such as corrupted images natural images, medical images, and camouflaged objects. We conduct comprehensive evaluations, including comparisons with state-of-the-art methods and detailed qualitative analyses. Our experiments encompass prompt segmentation, unsupervised segmentation, open vocabulary segmentation, and one shot segmentation. Both SAM and SAM2 backbones are used in our evaluation, and we perform ablation studies to analyze the contribution of each component.

4.1. Datasets

The source domain training set, SA-1B, was mainly constructed by collecting from natural environments. In this work, we identified five types of downstream segmentation tasks, some of which feature a drastic distribution shift from SA-1B, for evaluation, covering natural clean images, natural corrupted images, medical images, camouflaged images and robotic images. We present the datasets evaluated for each type of downstream task in

Table 1.

Datasplit: We divide each downstream dataset into non-overlapping training and testing sets following the ratio established by [

58]. The adaptation step is implemented on the training set. After the model is adapted, we evaluate the model on the held-out testing set.

4.2. Experiment Details

Segment-Anything Model: We adopt ViT-B [

86] as the encoder network due to memory constraint. The standard prompt encoder and mask decoder are adopted.

Prompt Generation: We first provide details for generating prompt at both training stages. All training prompts are calculated from ground-truth segmentation mask, simulating the human interactions as weak supervision. Specifically, we extract the minimal bounding box that covers the whole instance segmentation mask as box prompt. The point prompt is created as randomly selecting 5 positive points within ground-truth instance segmentation mask and 5 negative points outside ground-truth mask. The coarse segmentation mask is simulated by fitting a polygon to the ground-truth mask. We choose the number of vertices as with P indicating the perimeter of mask. The minimal number of vertices is 3. We use the same way to generate testing prompt on the testing data. This practice guarantees fair evaluation of SAM model which requires prompt input for segmentation.

Evaluation Metrics: We report the mIoU as evaluation metrics. For each input prompt, the IoU is calculated between the ground-truth segmentation mask and predicted mask. The mIoU averages over the IoU of all instances.

Competing Methods: We evaluate multiple source-free domain adaptation approaches and one state-of-the-art weakly supervised domain adaptive segmentation approach. In specific, direct testing the pre-trained model (

Direct) with fixed prompt inputs is prone to the distribution shift and may not perform well on target datasets with significant shift.

TENT [

82] is a vanilla test-time adaptation method which optimizes an entropy loss for adapting to target domain.

SHOT [

42] employs pseudo label and applies uniform distribution assumption for source-free domain adaptation.

Soft Teacher [

83] was originally developed for semi-supervised image segmentation. We adapt Soft Teacher for domain adaptation by keeping the self-training component.

TRIBE [

84] proposed a strong baseline for generic test-time adaptation on continual and class imbalanced domain shifts. We adapt TRIBE for domain adaptive segmentation by replacing the training losses.

DePT [

85] inserts visual prompts into a visual Transformer and adjusts these source-initialized prompts solely during the adaptation process without accessing the source data.

WDASS [

58] developed a weakly supervised domain adaptive segmentation method. We also evaluate the upperbound of adapting SAM by fine-tuning with ground-truth segmentation masks, which is dubbed as

Supervised. Finally, we evaluate our weakly supervised domain adaptation method as

Ours. All the competing methods use the same backbone, i.e. the ViT-B from SAM.

Hyperparameters: We finetune LoRA module of the ViT-B image encoder by Adam optimizer for all experiments. We set the batchsize to 4, distributed over four RTX3090 GPUs, and the learning rate to 0.0001 with a weight decay of 0.0001. For Self-Training loss, we set the hyper-parameters

and

of

and

to 2 and 1 respectively.

is set to 20, which is the coefficients of

. For Anchor loss, the coefficients of two dice losses are denoted as

and

, both of which equal 0.5. For Contrast loss, we set the temperature

to 0.3. We have set the low rank of the LoRA module for the image encoder to 4. We apply strong and weak data augmentations for self-training and choices for augmentation follows [

83,

87]. As for the mask ratio r, we randomly select it from the range of 0 to 0.75 based on previous work.

4.3. Quantitative Evaluations

In this section, we report the quantitative evaluations on the 5 types of target datasets. For each dataset, we also report the adaptation results with weak supervision in the form of bounding box (box), sparse points (point) and coarse segmentation mask (poly).

Adaptation to Corrupted Images: Visual corruptions often occur due to sensor fault, bad weather conditions, etc. As seen from

Table 2, without any adaptation,

Direct testing is significantly worse than than the upperbound. With weakly supervisions, all methods could improve over direct testing, in particular, our proposed method outperforms all competing adaptation methods on 10 out of 15 types of corruptions.

Adaptation to Natural Images: We then present the results of adapting SAM to natural images in

Table 3. For each type of weak supervision, we use the same type of prompt on the testing set. Despite the distribution gap between SA-1B and the target natural images, we observe significant performance gap between

Supervised upperbound and

Direct baseline, e.g. with box level supervision, there is

gap in IoU. When weak supervision is provided, both state-of-the-art generic source-free domain adaptation methods and weakly supervised domain adaptive segmentation method improve the generalization on all three types of weak supervisions. Finally, our proposed weakly supervised method achieves a remarkable improvement over all competing methods.

Adaptation to Medical Images: Segmentation for medical images is a major application of foundation models. Our empirical observations in

Table 4 on two medical segmentation datasets suggest that direct applying pre-trained SAM is suboptimal. With weakly supervised adaptation, the segmentation accuracy is greatly improved. We observe the improvement to be particularly significant with point and box which are relatively easy to obtain due to the low labeling cost.

Adaptation to Camouflaged Objects: We further evaluate on adapting SAM to camouflaged object detection. We evaluate on three camouflaged object detection datasets with results reported in

Table 5. Preliminary studies revealed that SAM is particularly vulnerable to camouflaged objects [

25] due to the low contrast between background and foreground. We make similar observations here that even with the help of prompt inputs at testing stage,

Direct inference suffers a lot, achieving less than 66% mIoU. When weakly labeled data are used for adaptation, we observe very significant improvements, with point prompt only we improved by a staggering 35% in mIoU on the CHAMELEON dataset. Our proposed method is also consistently better than all competing methods on all types of weak supervisions.

Adaptation to Robotic Images: Finally, we evaluate adapting SAM to image collected from robotic environments where segmenting out the spatial extent of individual objects is essential for interactions. As seen from the results in

Table 6, adapting SAM to robotic images with weak supervision further increase the segmentation accuracy. The improvement is more noticeable with point and polygon weak supervisions.

4.4. Qualitative Evaluations

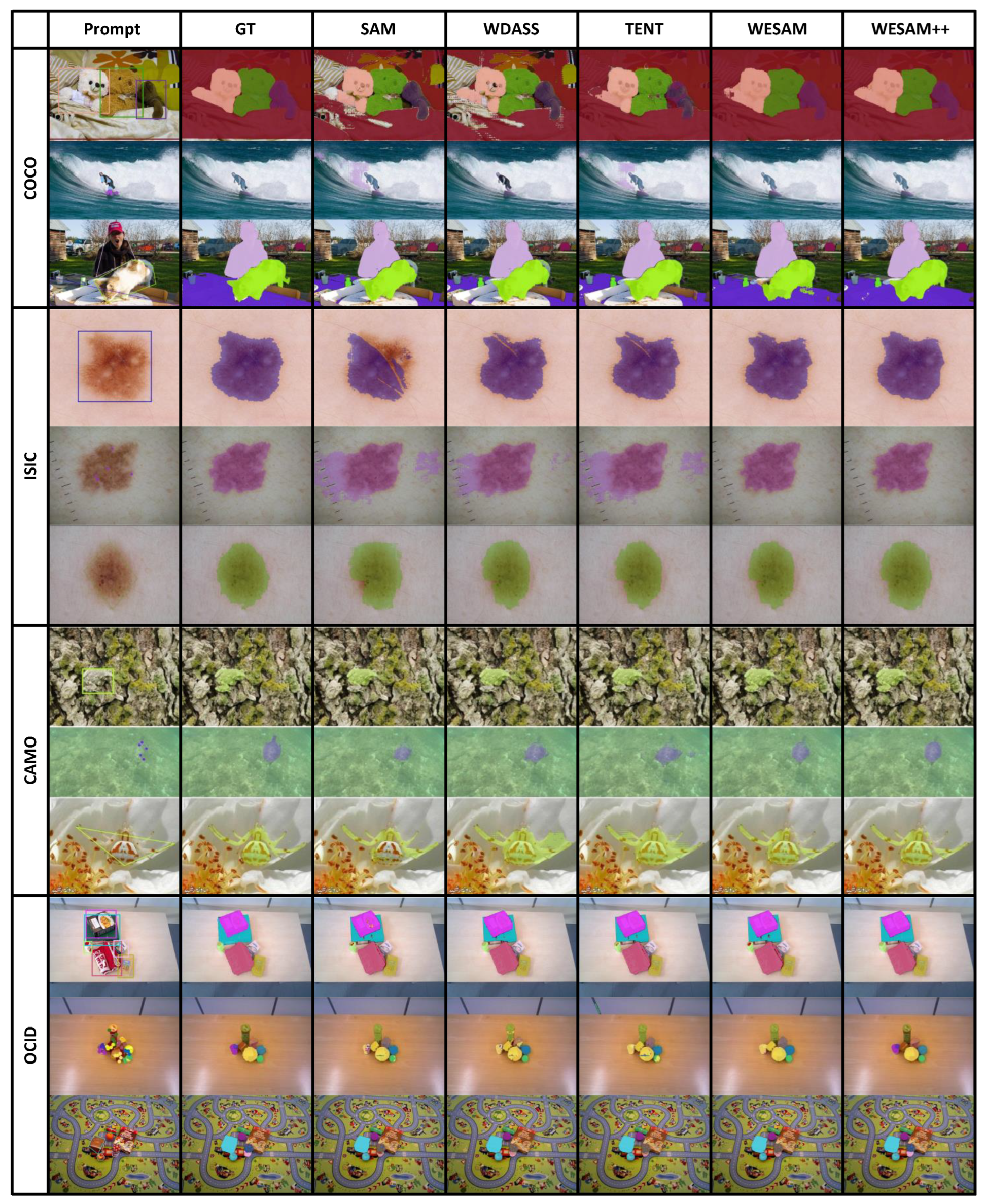

We present the qualitative comparisons of segmentation results for selected examples in

Figure 5. We make the following observations from the results. Evaluating pre-trained SAM (SAM) on COCO with both box and point prompt exhibits very fine-grained segmentation results. However, the model is overly sensitive to the high contrast regions, e.g. the hair for the girl and the toppings of pizza are missing from the segmentation mask. With the proposed weakly supervised adaptation approach, our method is able to generate more smoothed segmentation mask and the mask better reflects the semantic boundary. Similar observations are made from the medical image segmentation dataset. Without adapting the SAM model, segmentation results are either too conservative with low recall or expanding beyond the semantic boundary. With our weakly supervised adaptation, SAM is able to produce high fidelity results. We further present results on camouflaged segmentation task (CAMO). Without adaptation, SAM fails to segment out the spider’s belly and confuses the snow background with the harp seal in the foreground. Our weakly adapted SAM successfully segments out the spider’s belly and produces high quality mask for the harp seal. Finally, two examples from OCID dataset suggest that the pre-trained SAM tends to over-segment, e.g. missing the open whole for the tissue box, or confusing adjacent objects, e.g. merging the pen with the folder label. With weakly supervised adaptation SAM picks up the semantic meaning and produces segmentation results that better aligns with human intention.

4.5. Fully Automated Segmentation

We evaluate the effectiveness of our fully automated prompt generation and self-training strategy on multiple benchmark datasets. Initial point prompts are obtained by densely sampling grid points at 16-pixel intervals, generating an initial set of segmentation masks using the anchor network. These masks are filtered based on IoU and stability scores, followed by Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) to retain only high-quality candidates. From the pruned masks, we derive a fixed set of prompts , which ensures one-to-one correspondence among the segmentation outputs , , and across the three branches, enabling consistent self-training and cross-branch regularization.

As shown in

Table 7, our method consistently outperforms the baseline across all datasets and metrics, achieving notable gains in IoU, mAP, and Dice scores. These results demonstrate that automated prompt generation, combined with cross-branch regularization, significantly enhances segmentation accuracy and robustness.

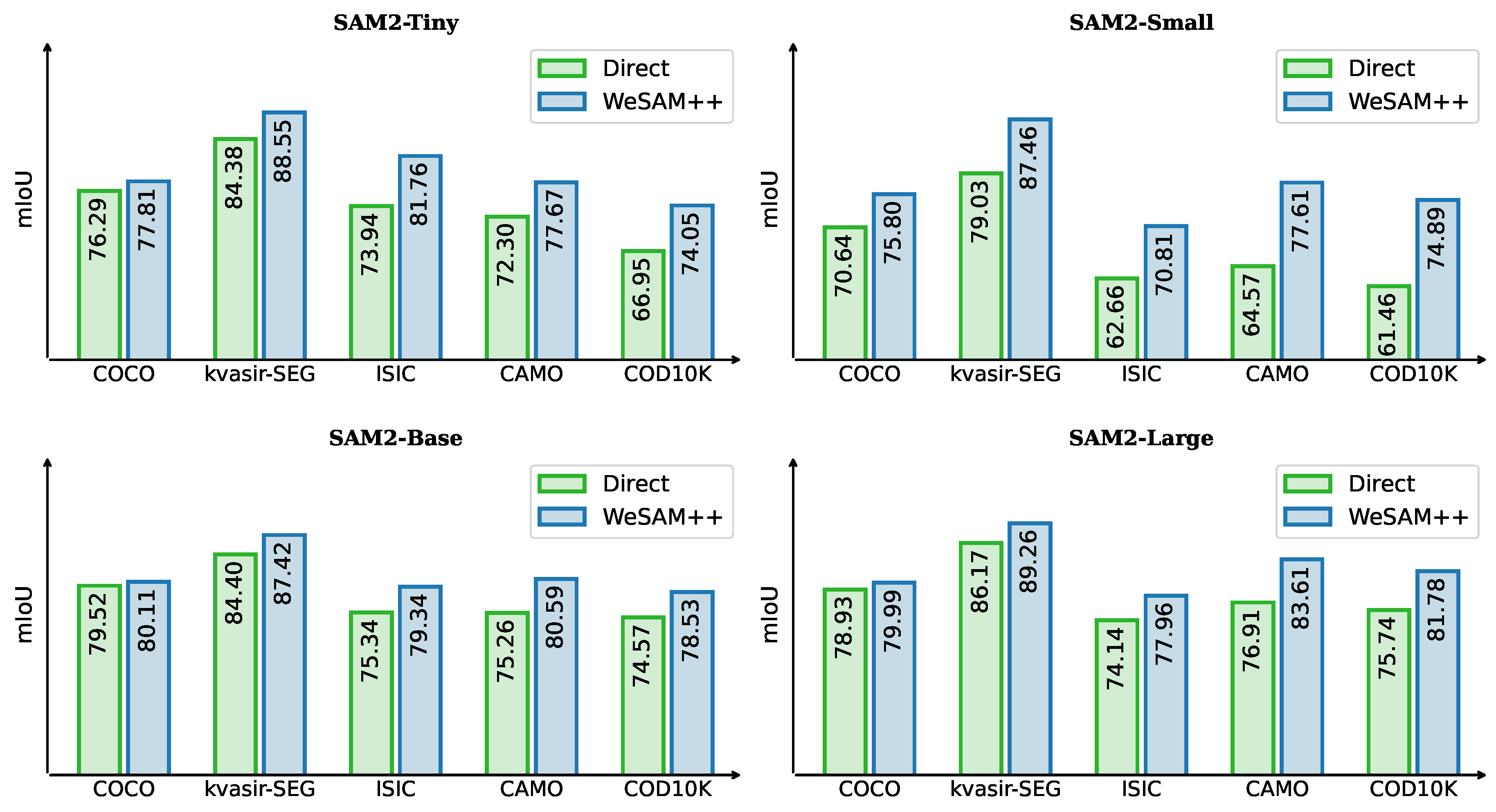

4.6. Segment Anything Model 2

Segment Anything Model 2 (SAM2) [

88] is a state-of-the-art foundational model for promptable visual segmentation in images and videos, delivering both higher segmentation accuracy and up to

faster inference compared to SAM. To assess the generality of our adaptive strategy, we evaluate it on SAM2 across multiple scales (tiny, small, base, large) and benchmark datasets, including COCO [

20], Kvasir-SEG [

76], ISIC [

77], CAMO [

78], and COD10K.

As shown in

Figure 6, our method yields consistent gains across all datasets and model sizes. For example, on Kvasir-SEG, the

small model improves from 79.03 to 87.46, and on COD10K, the

large model increases from 75.74 to 81.78. Gains are particularly pronounced in challenging scenarios with complex backgrounds or subtle object boundaries, underscoring enhanced robustness. These results confirm that our strategy is both effective and model-agnostic—boosting performance for lightweight and large variants alike—and broadly applicable across domains from natural images to specialized tasks such as medical image segmentation and camouflaged object detection.

4.7. Open-Vocabulary Segmentation

Open-vocabulary segmentation generates pixel-level masks for regions described by arbitrary text prompts, enabling fine-grained and flexible image understanding. The task is challenging due to the scarcity of high-quality annotated segmentation data, particularly in unstructured or open-set scenarios. In contrast, open-set detection is easier, as it relies on cheaper and more abundant bounding box annotations [

89]. Moreover, predicting masks from a given bounding box is more tractable than segmenting directly from text, as the object location is already known. Recent works, such as OpenSeeD [

60] and SAM [

4], have leveraged large-scale datasets to mitigate data scarcity and improve performance.

Building on these advances, we explore open-vocabulary segmentation using text prompts. Our pipeline employs Grounding DINO [

90] to detect bounding boxes conditioned on the input text, which are then passed to SAM [

4] as box prompts. We fine-tune SAM in an open-set setting to boost segmentation capability, evaluating two Grounding DINO variants: tiny (T) and base (B). The baseline (rows 1 and 3 in

Table 8) directly feeds detector outputs to SAM. Our method (rows 2 and 4) first applies unsupervised adaptation to SAM before evaluation.

As shown in

Table 8, our approach consistently outperforms the baseline for both detector variants. With Grounding-DINO-T, IoU improves from 70.46 to 73.12 and accuracy from 79.27 to 81.47. With Grounding-DINO-B, IoU increases from 70.38 to 73.07 and accuracy from 79.09 to 81.33. These results confirm that unsupervised adaptation substantially enhances SAM’s open-vocabulary segmentation performance, particularly in open-set scenarios.

4.8. One-shot Personalized Segmentation

We further evaluate the effectiveness of our weakly supervised adaptation strategy for one-shot personalized segmentation. Specifically, we build upon PerSAM [

91], a training-free approach that enables SAM to perform one-shot segmentation using a single reference image and mask. PerSAM localizes the target concept via a location prior and segments the object through target-guided attention, semantic prompting, and cascaded post-refinement.

To assess cross-domain generalization, we conduct one-shot segmentation experiments on both the COCO (natural images) and ISIC (medical images) datasets. We compare three variants: (1) the original PerSAM, (2) PerSAM-F, which finetunes mask weights on the reference image, and (3) our method, which first adapts SAM with weakly labeled data before applying PerSAM. As shown in

Table 9, our adapted SAM consistently outperforms both PerSAM and PerSAM-F across domains. Notably, on the ISIC dataset, our approach achieves a substantial improvement in mIoU (66.46 vs. 41.06), demonstrating strong robustness to domain shift. On COCO, our method also yields the best performance (33.98 mIoU), indicating that adaptation does not compromise in-distribution accuracy.

These results highlight two key findings: (1) Weakly supervised adaptation significantly enhances SAM’s cross-domain generalization, particularly in challenging medical imaging scenarios, without requiring changes to the reference image. (2) The consistent improvements across both natural and medical domains suggest that our approach provides fundamental gains in segmentation generalization, enabling the model to acquire transferable knowledge that bridges both domain gaps and in-distribution challenges.

4.9. Ablation Study

Effectiveness Of Individual Components: In this section, we analyze the effectiveness of individual components on COCO dataset. As presented in

Table 10, when self-training is applied alone, we observe a significant performance drop (

with box weak supervision), suggesting the severity of confirmation bias. This issue can be well remedied when the anchor loss regularization is applied. Self-training with anchored regularization already improves the performance of SAM after adaptation. Finally, the contrastive loss directly regularizes the encoder network’s output and contributes with additional improvement of segmentation accuracy. We also investigate the final self-training architecture without any weak supervision, i.e. the pseudo label masks are generated with grid point prompt. The results after adaptation is slightly worse than with weak supervision but consistently better than without adaptation on both box and coarse mask testing prompts. Nevertheless, the results with point prompt performs even worse than without adaptation, suggesting the necessity of weakly supervised adaptation.

Comparison with Alternative Masked Image Modelling: We propose an Embedding Mix Up training strategy within the MAE framework to strengthen feature consistency between student and teacher branches during self-training. To isolate its effect, we compare against two alternatives: (1) the standard MAE [

68] using learned mask tokens in the decoder without mix up, and (2) the Data Mix Up strategy from [

74]. Experimental results in

Table 11 show that our approach outperforms both variants, highlighting its effectiveness in enhancing representation quality.

4.10. Additional Analysis

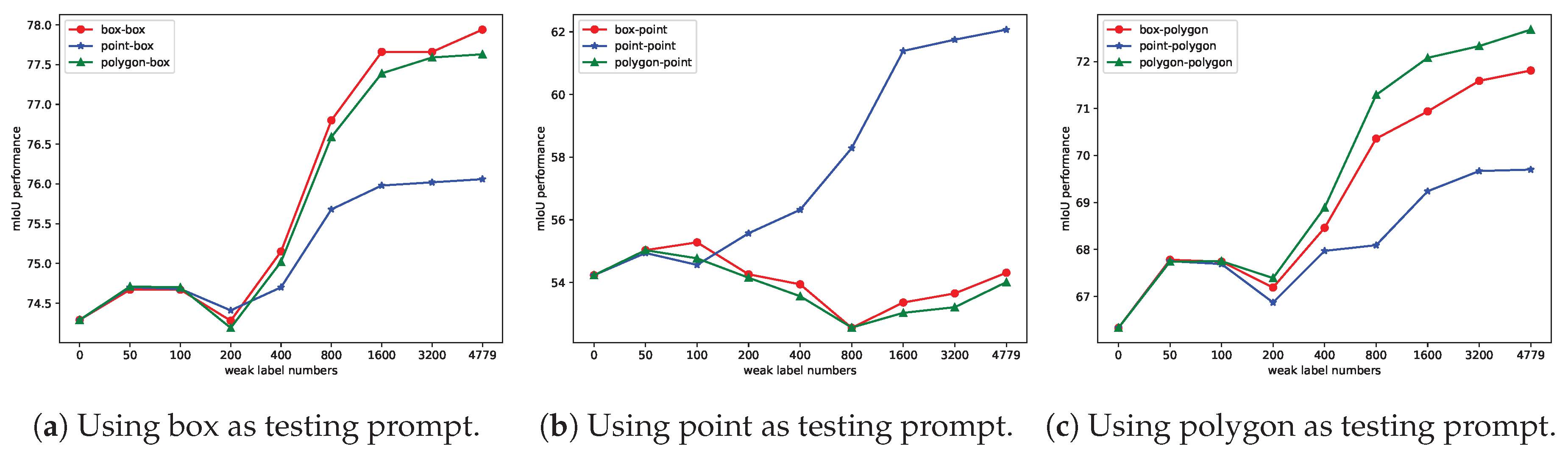

The Impact of Weak Label Numbers on Performance: In this experiment, we aim to demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of utilizing weak labels. To facilitate comparison, we incrementally choose weakly labeled images of 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200, and 4246 in COCO dataset for adaptation. We adapt the model using three different types of weak labels and evaluate their performance using three different prompts. We make the following observations from

Figure 7 (a-c). First, when training/adaptation weak supervision is the same with testing prompt, we observe the most effective generalization of SAM. Moreover, the generalization improves upon more weak supervision except for adaptation with point label and testing with box and polygon prompts. This suggest the mask decoder is still sensitive to the shift of prompt used for training and testing.

Generalization to Cross-Prompt Testing: We further investigate the effectiveness of adaptation by testing with all three types of prompts. Specifically, we compare with the best (WDASS) and second best (TENT) methods with results presented in

Table 12. Apart from using point as testing prompt, our methods consistently improves the performance even though the testing prompt is different from training weak supervision.

Effectiveness of Updating Different Components: Given limited computing resources, choosing the appropriate components of network to update is crucial to optimize the generalization performance. In this section, we investigate several options of network components to update during adaptation.

Full finetune means finetuning the whole encoder.

MaskDecoder finetune the whole decoder of SAM without additional redundant learnable parameters.

LayerNorm finetune the all layernorms of the SAM image encoder.

LoRA finetunes the encoder network in through low-rank decomposition only.

EVP use the Embedding Tune and the HFC Tune to tune the extracted features by image encoder. We present the investigation on the COCO dataset with bounding boxes as weak supervision in

Table 13. In particular, we have also explored the impact of different combinations of components, e.g. MaskDecoder + LoRA, LoRA + EVP, and so on. The results suggest LoRA finetuning the encoder network alone yields the best performance.

Hyper-Parameter Sensitivity: In this section, we evaluate the sensitivity to different hyper-parameters. For Anchor loss, the coefficients of two dice losses are denoted as

and

, For the Anchor loss, the coefficients of the two dice losses are denoted as

and

, respectively, and are set as follows: 1.0:0, 0.7:0.3, 0.5:0.5, 0.3:0.7, 0:1.0. For Contrast loss, we set the temperature

to 0.1, 0.3, 0.5. For model finetuning, we use the Adam optimizer with learning rates set to 0.001, 0.0001, and 0.00001, respectively. As shown in Tab

Table 14, out proposed weakly supervised adaptation method is relatively stable to the choice of hyper-parameters.

5. Conclusions

We investigate the generalization capability of the Segment Anything Models (SAM and SAM2) across diverse downstream segmentation tasks and identify their limitations under distribution shifts. To address this, we propose a task-agnostic adaptation method based on self-training without source data and low-rank finetuning for memory efficiency. Our framework supports both weakly-supervised and unsupervised adaptation, leveraging weak supervision via SAM’s prompt encoder. Patch-level contrastive regularization and masked image modeling further enhance feature alignment and robustness. Experiments on five segmentation tasks across four scenarios with SAM and SAM2 demonstrate that our approach consistently improves generalization and outperforms domain adaptation baselines.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant Number: 62106078), and Agency for Science, Technology and Research (Grant Number: M23L7b0021). This work was partially done during Yongyi Su’s attachment with Institute for Infocomm Research (I2R), funded by China Scholarship Council (CSC).

References

- Kim, Y.; Cho, D.; Han, K.; Panda, P.; Hong, S. Domain adaptation without source data. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oquab, M.; Darcet, T.; Moutakanni, T.; Vo, H.; Szafraniec, M.; Khalidov, V.; Fernandez, P.; Haziza, D.; Massa, F.; El-Nouby, A.; et al. Dinov2: Learning robust visual features without supervision. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.07193 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Zhu, L.; Ding, C.; Cao, R.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, L.; Mao, P.; Zang, Y. SAM Fails to Segment Anything?–SAM-Adapter: Adapting SAM in Underperformed Scenes: Camouflage, Shadow, and More. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.09148 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, T.; Juefei-Xu, F.; Lin, D.; Tsang, I.W.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Q. On the robustness of segment anything. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.16220 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Hu, J.; Jin, C.; Li, L.; Wang, L. Understanding domain randomization for sim-to-real transfer. In Proceedings of the Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Zaremba, W.; Sutskever, I.; Bruna, J.; Erhan, D.; Goodfellow, I.; Fergus, R. Intriguing properties of neural networks. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6199 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ganin, Y.; Lempitsky, V. Unsupervised domain adaptation by backpropagation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Hu, D.; Feng, J. Do we really need to access the source data? source hypothesis transfer for unsupervised domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Raghunathan, A.; Jones, R.M.; Ma, T.; Liang, P. Fine-Tuning can Distort Pretrained Features and Underperform Out-of-Distribution. In Proceedings of the Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Y.H.; Hung, W.C.; Schulter, S.; Sohn, K.; Yang, M.H.; Chandraker, M. Learning to adapt structured output space for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Tao, D. Category anchor-guided unsupervised domain adaptation for semantic segmentation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.; Yu, Z.; Liu, X.; Kumar, B.; Wang, J. Confidence regularized self-training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arazo, E.; Ortego, D.; Albert, P.; O’Connor, N.E.; McGuinness, K. Pseudo-labeling and confirmation bias in deep semi-supervised learning. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Su, Y.; Xu, X.; Jia, K. Improving the generalization of segmentation foundation model under distribution shift via weakly supervised adaptation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024; pp. 23385–23395.

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Everingham, M.; Eslami, S.A.; Van Gool, L.; Williams, C.K.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The pascal visual object classes challenge: A retrospective 2015.

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Tang, H.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, L. Dual Memory Networks: A Versatile Adaptation Approach for Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Wang, B. Segment anything in medical images. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.12306 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, D. Customized segment anything model for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.13785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Xiao, H.; Li, B. Can sam segment anything? when sam meets camouflaged object detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.04709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Zhang, C.; Qiao, Y.; Qamar, M.; Jung, Y.; Lee, S.; Bae, S.H.; Hong, C.S. Segment anything model (sam) meets glass: Mirror and transparent objects cannot be easily detected. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.00278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Liu, L.; Lu, D.; Jia, K. SAM-6D: Segment Anything Model Meets Zero-Shot 6D Object Pose Estimation, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2311.15707].

- Long, M.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Jordan, M. Learning transferable features with deep adaptation networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, M.; Meng, L.; Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Shen, H.T. Adversarial mixup ratio confusion for unsupervised domain adaptation. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, E.; Hoffman, J.; Saenko, K.; Darrell, T. Adversarial discriminative domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, B.; Tang, H.; Zhang, L.; Jia, K. Unsupervised multi-class domain adaptation: Theory, algorithms, and practice. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2020, 44, 2775–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Jiao, Q.; Cao, W.; Wong, H.S.; Wu, S. Model adaptation: Unsupervised domain adaptation without source data. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu, J.N.; Venkat, N.; Babu, R.V.; et al. Universal source-free domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Van De Weijer, J.; Herranz, L.; Jui, S. Generalized source-free domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, H.; Zhao, H.; Ding, Z. Adaptive adversarial network for source-free domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Kothari, P.; Van Delft, B.; Bellot-Gurlet, B.; Mordan, T.; Alahi, A. Ttt++: When does self-supervised test-time training fail or thrive? Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Sheng, L.; Liang, J.; Zheng, A.; He, R. Proxymix: Proxy-based mixup training with label refinery for source-free domain adaptation. Neural Networks 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, W.; Morerio, P.; Murino, V. Cleaning noisy labels by negative ensemble learning for source-free unsupervised domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, S.; Chen, G.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; He, W.; Tao, D. Bmd: A general class-balanced multicentric dynamic prototype strategy for source-free domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M.; Bu, Y.; Wornell, G. On the benefits of selectivity in pseudo-labeling for unsupervised multi-source-free domain adaptation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.00796 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, T.; Liu, Y.; Deng, J.; Li, W.; Duan, L. Denoised Maximum Classifier Discrepancy for Source-Free Unsupervised Domain Adaptation. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Hu, D.; Wang, Y.; He, R.; Feng, J. Source data-absent unsupervised domain adaptation through hypothesis transfer and labeling transfer. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, L.; Sato, Y. Weakly Supervised Temporal Sentence Grounding With Uncertainty-Guided Self-Training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023; pp. 18908–18918.

- Kurmi, V.K.; Subramanian, V.K.; Namboodiri, V.P. Domain impression: A source data free domain adaptation method. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, H.; Niu, S.; Liu, Y.; Du, Q.; Tan, M. Source-free domain adaptation via avatar prototype generation and adaptation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.15326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J. Source-free domain adaptation for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Herranz, L.; Jui, S.; van de Weijer, J. Casting a BAIT for offline and online source-free domain adaptation. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Ye, M.; Zhang, D.; Gan, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y. Source data-free domain adaptation of object detector through domain-specific perturbation. International Journal of Intelligent Systems 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ye, M.; Xiong, L.; Li, S.; Li, X. Source-style transferred mean teacher for source-data free object detection. In ACM Multimedia Asia; 2021.

- Jing, M.; Zhen, X.; Li, J.; Snoek, C. Variational model perturbation for source-free domain adaptation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Du, Z.; Zhu, L.; Ding, Z.; Lu, K.; Shen, H.T. Divergence-agnostic unsupervised domain adaptation by adversarial attacks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wu, Z.; Weng, Z.; Chen, J.; Qi, G.J.; Jiang, Y.G. Cross-domain contrastive learning for unsupervised domain adaptation. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateson, M.; Kervadec, H.; Dolz, J.; Lombaert, H.; Ayed, I.B. Source-free domain adaptation for image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, J.N.; Kulkarni, A.; Singh, A.; Jampani, V.; Babu, R.V. Generalize then adapt: Source-free domain adaptive semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, S.; Tsai, Y.H.; Schulter, S.; Roy-Chowdhury, A.K.; Chandraker, M. Domain adaptive semantic segmentation using weak labels. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Gao, J.; Li, X. Weakly supervised adversarial domain adaptation for semantic segmentation in urban scenes. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Xian, Y.; He, Y.; Akata, Z.; Schiele, B. Urban Scene Semantic Segmentation with Low-Cost Coarse Annotation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.; Xian, Y.; Dai, D.; Schiele, B. Weakly-Supervised Domain Adaptive Semantic Segmentation With Prototypical Contrastive Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, M.; Touvron, H.; Misra, I.; Jégou, H.; Mairal, J.; Bojanowski, P.; Joulin, A. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 9650–9660.

- Zhang, H.; Li, F.; Zou, X.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L. A simple framework for open-vocabulary segmentation and detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023; pp. 1020–1031.

- Chen, X.; He, K. Exploring simple siamese representation learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021; pp. 15750–15758.

- Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Shen, C.; Kong, T.; Li, L. Dense contrastive learning for self-supervised visual pre-training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021; pp. 3024–3033.

- Vincent, P.; Larochelle, H.; Lajoie, I.; Bengio, Y.; Manzagol, P.A.; Bottou, L. Stacked denoising autoencoders: Learning useful representations in a deep network with a local denoising criterion. Journal of machine learning research 2010, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, D.; Krahenbuhl, P.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Efros, A.A. Context encoders: Feature learning by inpainting. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016; pp. 2536–2544.

- Bao, H.; Dong, L.; Piao, S.; Wei, F. Beit: Bert pre-training of image transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.08254 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Fan, H.; Xie, S.; Wu, C.Y.; Yuille, A.; Feichtenhofer, C. Masked feature prediction for self-supervised visual pre-training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022; pp. 14668–14678.

- Xie, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Lin, Y.; Bao, J.; Yao, Z.; Dai, Q.; Hu, H. modeling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022; pp. 9653–9663.

- He, K.; Chen, X.; Xie, S.; Li, Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Masked autoencoders are scalable vision learners. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y.; Varadarajan, B.; Wu, L.; Xiang, X.; Xiao, F.; Zhu, C.; Dai, X.; Wang, D.; Sun, F.; Iandola, F.; et al. anything. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024; pp. 16111–16121.

- Sohn, K.; Berthelot, D.; Carlini, N.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Raffel, C.A.; Cubuk, E.D.; Kurakin, A.; Li, C.L. Fixmatch: Simplifying semi-supervised learning with consistency and confidence. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.A. V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on 3D vision; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, T.; Jia, K. Revisiting Realistic Test-Time Training: Sequential Inference and Adaptation by Anchored Clustering Regularized Self-Training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.10856, arXiv:2303.10856 2023.

- Zhu, J.; Bai, H.; Wang, L. Patch-mix transformer for unsupervised domain adaptation: A game perspective. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023; pp. 3561–3571.

- Su, Y.; Xu, X.; Jia, K. Revisiting realistic test-time training: Sequential inference and adaptation by anchored clustering. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, D.; Smedsrud, P.H.; Riegler, M.A.; Halvorsen, P.; de Lange, T.; Johansen, D.; Johansen, H.D. Kvasir-seg: A segmented polyp dataset. In Proceedings of the MultiMedia Modeling: 26th International Conference, MMM 2020, Daejeon, South Korea, 2020, Proceedings, Part II 26, 2020., January 5–8.

- Gutman, D.; Codella, N.C.; Celebi, E.; Helba, B.; Marchetti, M.; Mishra, N.; Halpern, A. Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection: A challenge at the international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI) 2016, hosted by the international skin imaging collaboration (ISIC). arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.01397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.N.; Nguyen, T.V.; Nie, Z.; Tran, M.T.; Sugimoto, A. Anabranch network for camouflaged object segmentation. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.P.; Ji, G.P.; Sun, G.; Cheng, M.M.; Shen, J.; Shao, L. Camouflaged object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Suchi, M.; Patten, T.; Fischinger, D.; Vincze, M. EasyLabel: A Semi-Automatic Pixel-wise Object Annotation Tool for Creating Robotic RGB-D Datasets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Robotics and Automation; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Richtsfeld, A.; Mörwald, T.; Prankl, J.; Zillich, M.; Vincze, M. Segmentation of unknown objects in indoor environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Shelhamer, E.; Liu, S.; Olshausen, B.; Darrell, T. Tent: Fully test-time adaptation by entropy minimization. In Proceedings of the Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Wei, F.; Bai, X.; Liu, Z. End-to-end semi-supervised object detection with soft teacher. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Xu, X.; Jia, K. Towards Real-World Test-Time Adaptation: Tri-Net Self-Training with Balanced Normalization. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.14949 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Tang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Li, M.; Metaxas, D.N. Visual prompt tuning for test-time domain adaptation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.04831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, K.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C.L.; Zhang, H.; Lee, C.Y.; Pfister, T. A simple semi-supervised learning framework for object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.04757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, N.; Gabeur, V.; Hu, Y.T.; Hu, R.; Ryali, C.; Ma, T.; Khedr, H.; Rädle, R.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; et al. Sam 2: Segment anything in images and videos. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.00714 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, T.; Liu, S.; Zeng, A.; Lin, J.; Li, K.; Cao, H.; Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Chen, Y.; Yan, F.; et al. Grounded sam: Assembling open-world models for diverse visual tasks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.14159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zeng, Z.; Ren, T.; Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Jiang, Q.; Li, C.; Yang, J.; Su, H.; et al. Grounding dino: Marrying dino with grounded pre-training for open-set object detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Jiang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Yan, S.; Pan, J.; Dong, H.; Gao, P.; Li, H. Personalize segment anything model with one shot. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.03048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Segment Anything Model was pre-trained on a large-scale dataset but exhibits awkward performance on diverse downstream segmentation tasks. We adapt SAM through weak supervision to enhance its generalization capabilities.

Figure 1.

Segment Anything Model was pre-trained on a large-scale dataset but exhibits awkward performance on diverse downstream segmentation tasks. We adapt SAM through weak supervision to enhance its generalization capabilities.

Figure 2.

Pipeline of our proposed self-training framework for adapting SAM to downstream segmentation tasks. The architecture consists of anchor, student, and teacher branches for source-free self-training. Output-space regularization is achieved through pseudo-label supervision, while feature-space consistency is enforced via patch-level contrastive loss between anchor and student/teacher networks. Masked Image Modeling (MIM) enhances inter-branch feature alignment and robustness. The framework supports fully automated prompt generation for unsupervised adaptation and makes use of weak labels as prompts for weakly supervised adaptation. Model weights are updated via LoRA-based low-rank fine-tuning for computational efficiency.

Figure 2.

Pipeline of our proposed self-training framework for adapting SAM to downstream segmentation tasks. The architecture consists of anchor, student, and teacher branches for source-free self-training. Output-space regularization is achieved through pseudo-label supervision, while feature-space consistency is enforced via patch-level contrastive loss between anchor and student/teacher networks. Masked Image Modeling (MIM) enhances inter-branch feature alignment and robustness. The framework supports fully automated prompt generation for unsupervised adaptation and makes use of weak labels as prompts for weakly supervised adaptation. Model weights are updated via LoRA-based low-rank fine-tuning for computational efficiency.

Figure 4.

Illustration of GradCAM visualization between two views.

Figure 4.

Illustration of GradCAM visualization between two views.

Figure 5.

qualitative results on some selected examples. Three types of prompts at testing stage are visualized for reference.

Figure 5.

qualitative results on some selected examples. Three types of prompts at testing stage are visualized for reference.

Figure 6.

Adaptation results of different SAM2 model sizes on the COCO dataset.

Figure 6.

Adaptation results of different SAM2 model sizes on the COCO dataset.

Figure 7.

Annotation cost vs. performance. 1. Performance of different numbers of weak labels on performance. 2. Performance of three weak labels under the same prompt verification.

Figure 7.

Annotation cost vs. performance. 1. Performance of different numbers of weak labels on performance. 2. Performance of three weak labels under the same prompt verification.

Table 1.

Dataset and datasplit used in this work.

Table 1.

Dataset and datasplit used in this work.

| |

Natural Images |

Corrupted Images |

Medical Images |

Camouflaged Objects |

Robotic Images |

| |

COCO [20] |

Pascal VOC [19] |

COCO-C |

kvasir-SEG [76] |

ISIC [77] |

CAMO [78] |

COD10K [79] |

OCID [80] |

OSD [81] |

| # Training |

4246 |

2497 |

4246 |

834 |

900 |

1000 |

6000 |

1972 |

56 |

| # Testing |

706 |

416 |

706 |

166 |

379 |

250 |

4000 |

328 |

55 |

Table 2.

Adaptation results on COCO-C dataset using bounding box prompt.

Table 2.

Adaptation results on COCO-C dataset using bounding box prompt.

| Method |

Brit |

Contr |

Defoc |

Elast |

Fog |

Frost |

Gauss |

Glass |

Impul |

Jpeg |

Motn |

Pixel |

Shot |

Snow |

Zoom |

Avg |

| Direct |

73.12 |

58.21 |

64.11 |

68.89 |

72.02 |

70.61 |

66.06 |

63.90 |

66.54 |

67.53 |

62.44 |

68.49 |

66.82 |

68.8 |

58.28 |

66.39 |

| TENT [82] |

76.02 |

61.51 |

67.48 |

70.88 |

74.89 |

69.21 |

69.01 |

67.10 |

69.28 |

60.21 |

65.45 |

61.73 |

69.96 |

70.77 |

62.59 |

67.74 |

| SHOT [42] |

73.96 |

60.04 |

64.95 |

69.73 |

73.00 |

71.33 |

67.29 |

64.79 |

67.67 |

68.64 |

63.77 |

69.61 |

68.13 |

69.79 |

59.97 |

67.51 |

| Soft Teacher [83] |

74.06 |

58.91 |

65.58 |

69.47 |

73.22 |

71.74 |

67.72 |

65.67 |

67.90 |

69.27 |

64.17 |

70.50 |

68.88 |

70.97 |

60.05 |

67.87 |

| TRIBE [84] |

74.46 |

59.09 |

52.04 |

70.53 |

71.47 |

72.84 |

69.45 |

63.61 |

69.20 |

70.41 |

64.07 |

72.92 |

71.20 |

72.49 |

62.37 |

67.74 |

| DePT [85] |

69.15 |

57.26 |

59.08 |

66.80 |

58.73 |

66.75 |

66.78 |

62.74 |

65.65 |

66.39 |

61.66 |

66.65 |

67.57 |

66.62 |

58.21 |

64.42 |

| WDASS [58] |

74.21 |

60.13 |

64.96 |

70.10 |

73.15 |

71.74 |

67.53 |

65.09 |

68.14 |

68.87 |

64.18 |

69.88 |

68.26 |

70.06 |

60.17 |

67.76 |

| WeSAM [17] |

77.11 |

50.29 |

56.19 |

72.75 |

73.14 |

75.40 |

71.39 |

68.55 |

71.80 |

73.59 |

66.88 |

75.03 |

72.04 |

74.96 |

65.16 |

69.62 |

| WeSAM++ |

77.44 |

47.40 |

67.61 |

72.92 |

77.34 |

75.95 |

72.09 |

70.28 |

72.15 |

73.84 |

67.31 |

75.09 |

72.40 |

75.32 |

64.70 |

70.79 |

| Supervised |

78.86 |

74.81 |

72.04 |

74.32 |

78.01 |

77.14 |

73.43 |

72.12 |

74.08 |

75.30 |

71.39 |

75.15 |

74.25 |

76.34 |

68.04 |

74.35 |

Table 3.

Adaptation results on natural clean image datasets.

Table 3.

Adaptation results on natural clean image datasets.

| Method |

COCO 2017 [20] |

Pascal VOC [19] |

| |

box |

point |

poly |

box |

point |

poly |

| Direct |

74.29 |

54.23 |

66.33 |

76.89 |

69.21 |

60.79 |

| TENT [82] |

77.32 |

52.99 |

71.51 |

80.24 |

74.97 |

65.03 |

| SHOT [42] |

75.18 |

58.46 |

69.26 |

79.80 |

74.26 |

63.38 |

| Soft Teacher [83] |

75.05 |

57.07 |

67.19 |

78.05 |

71.62 |

62.25 |

| TRIBE [84] |

75.49 |

57.39 |

68.77 |

80.32 |

72.65 |

64.75 |

| DePT [85] |

70.62 |

45.26 |

64.29 |

73.89 |

67.34 |

60.89 |

| WDASS [58] |

75.21 |

60.55 |

70.19 |

78.75 |

56.38 |

64.39 |

| WeSAM [17] |

77.70 |

60.25 |

72.14 |

81.57 |

77.13 |

68.77 |

| WeSAM++ |

78.37 |

62.37 |

72.22 |

81.98 |

76.54 |

69.40 |

| Supervised |

81.50 |

69.77 |

73.39 |

81.23 |

76.98 |

71.32 |

Table 4.

Adaptation results on medical image segmentation datasets.

Table 4.

Adaptation results on medical image segmentation datasets.

| Method |

kvasir-SEG [76] |

ISIC [77] |

| |

box |

point |

poly |

box |

point |

poly |

| Direct |

81.50 |

60.97 |

76.25 |

66.88 |

53.03 |

63.40 |

| TENT [82] |

82.47 |

61.84 |

62.97 |

71.76 |

53.46 |

67.12 |

| SHOT [42] |

82.30 |

63.76 |

61.34 |

71.99 |

55.99 |

66.86 |

| Soft Teacher [83] |

84.36 |

69.75 |

78.89 |

70.52 |

58.03 |

66.76 |

| TRIBE [84] |

86.71 |

78.47 |

81.06 |

76.80 |

67.95 |

72.24 |

| DePT [85] |

81.95 |

52.06 |

77.24 |

77.15 |

46.79 |

69.97 |

| WDASS [58] |

84.31 |

49.13 |

78.86 |

70.91 |

42.12 |

67.00 |

| WeSAM [17] |

87.17 |

81.28 |

82.11 |

78.81 |

65.77 |

75.17 |

| WeSAM++ |

88.05 |

81.74 |

81.40 |

81.51 |

80.29 |

76.27 |

| Supervised |

85.89 |

77.54 |

81.64 |

81.62 |

79.81 |

80.26 |

Table 5.

Adaptation results on camouflaged object datasets.

Table 5.

Adaptation results on camouflaged object datasets.

| Method |

CAMO [78] |

COD10K [79] |

| |

box |

point |

poly |

box |

point |

poly |

| Direct |

62.65 |

57.88 |

54.02 |

63.19 |

62.12 |

44.99 |

| TENT [82] |

72.34 |

58.00 |

63.01 |

67.80 |

59.27 |

48.67 |

| SHOT [42] |

67.23 |

55.16 |

58.98 |

67.67 |

57.00 |

47.75 |

| Soft Teacher [83] |

69.24 |

63.61 |

60.81 |

67.9 |

65.11 |

47.31 |

| TRIBE [84] |

74.00 |

70.34 |

65.43 |

68.72 |

67.51 |

47.30 |

| DePT [85] |

55.33 |

55.26 |

48.93 |

58.36 |

59.61 |

41.79 |

| WDASS [58] |

67.59 |

55.45 |

59.45 |

67.92 |

57.84 |

47.83 |

| WeSAM [17] |

75.93 |

67.66 |

69.22 |

72.19 |

70.96 |

50.21 |

| WeSAM++ |

77.25 |

69.00 |

70.63 |

72.97 |

72.25 |

51.82 |

| Supervised |

78.59 |

76.14 |

73.11 |

77.12 |

76.18 |

62.62 |

Table 6.

Adaptation results on robotic image datasets.

Table 6.

Adaptation results on robotic image datasets.

| Method |

OCID [80] |

OSD [81] |

| |

box |

point |

poly |

box |

point |

poly |

| Direct |

86.43 |

69.71 |

84.10 |

85.89 |

73.10 |

84.33 |

| TENT [82] |

87.77 |

66.61 |

86.94 |

87.32 |

74.32 |

87.06 |

| SHOT [42] |

86.65 |

74.39 |

84.38 |

86.58 |

74.48 |

85.24 |

| Soft Teacher [83] |

86.99 |

72.00 |

84.74 |

86.87 |

79.79 |

85.72 |

| TRIBE [84] |

87.47 |

77.79 |

85.71 |

87.41 |

83.64 |

86.41 |

| DePT [85] |

84.47 |

68.58 |

82.79 |

84.17 |

69.14 |

83.55 |

| WDASS [58] |

86.95 |

32.66 |

84.58 |

86.81 |

74.52 |

85.36 |

| WeSAM [17] |

88.23 |

77.82 |

86.11 |

87.62 |

84.01 |

86.91 |

| WeSAM++ |

88.05 |

83.69 |

86.08 |

88.01 |

85.35 |

87.16 |

| Supervised |

91.24 |

89.22 |

88.68 |

92.14 |

82.41 |

90.83 |

Table 7.

Adaptation results by fully automated segmentation across multiple datasets.

Table 7.

Adaptation results by fully automated segmentation across multiple datasets.

| Method |

COCO [20] |

PascalVOC [19] |

kvasir-SEG [76] |

ISIC [77] |

CAMO [78] |

COD10K [79] |

OCID [80] |

OSD [81] |

| Direct[4] |

74.29 |

76.89 |

81.50 |

66.88 |

62.65 |

63.19 |

86.43 |

85.89 |

| TENT[82] |

75.30 |

78.62 |

81.60 |

67.41 |

67.20 |

65.40 |

87.65 |

85.26 |

| SHOT[10] |

74.51 |

77.03 |

82.67 |

69.98 |

65.38 |

65.44 |

87.31 |

85.84 |

| Soft Teacher [83] |

74.78 |

78.96 |

83.48 |

69.98 |

67.58 |

63.53 |

87.05 |

85.27 |

| TRIBE [84] |

75.03 |

78.24 |

84.34 |

76.51 |

68.65 |

65.74 |

87.33 |

85.86 |

| WDASS [58] |

74.50 |

78.35 |

82.63 |

67.71 |

65.60 |

65.50 |

87.34 |

86.80 |

| WeSAM [17] |

75.42 |

79.21 |

83.58 |

84.30 |

66.26 |

65.87 |

87.05 |

87.07 |

| WeSAM++ |

76.89 |

79.90 |

85.94 |

86.22 |

69.31 |

66.72 |

87.48 |

87.36 |

Table 8.

Open-vocabulary results on the COCO dataset.

Table 8.

Open-vocabulary results on the COCO dataset.

| Detector |

box AP |

Segmentor |

IoU |