Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

|

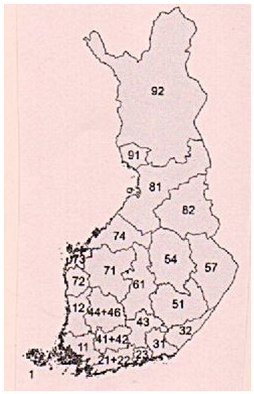

| Map 1. BirdLife Finland observation areas [9]. |

3. Results

3.1. Microevolution

3.2. Wildfires

3.3. Precipitation & Flooding

3.4. Rising Sea Level

3.5. Drought

3.6. Winter and Snow

3.7. Snow Structure

3.8. Habitat Loss

3.9. Climate-Related Nestbox Competition

3.10. The Effect of Climate Change on Prey Species

4. Discussion

References

- Dietz, T., Shwom, R. L. & Whitley, C. T. (2020). Climate Change and Society. Annual Review of Sociology 46:135-158. [CrossRef]

- WMO: https://wmo.int/.

- Sattar, Q., Maqbool, M. E., Ehsan, R. & Akhtar, S. (2021). Review on climate change and its effect on wildlife and ecosystem. Open Journal of Environmental Biology 6(1): 008-014. [CrossRef]

- Sieradzki, A. 2022. Designed for Darkness: The Unique Physiology and Anatomy of Owls. Chapter 1: 3‒26. In: Mikkola, H. (ed.), Owls: Clever Survivors. IntechOpen, London. [CrossRef]

- Pautasso, M. (2012). Observed impacts of climate change on terrestrial birds in Europe: an overview. Italian Journal of Zoology 79(2): 296‒314. [CrossRef]

- Vegvari, Z., Bokony, V., Barta, Z. & Kovacs, G. (2010).Life history predicts advancement ofavian spring migration in response to climate change. Global Change Biology 16: 1‒11.

- BirdLife Finland, https://lintulehti.birdlife.fi.

- Virkkala, R., Heikkinen, R. K., Leikola, N. & Luoto, M. (2008). Projected large-scale range reductions of northern-boreal land bird species due to climate change. Biological Conservation 141: 1343-1353. [CrossRef]

- Honkala, J., Lehikoinen, P., Saurola, P. & Valkama, J. (2025). Breeding and population trends of common raptors and owls in Finland in 2024. Linnut-vuosikirja 2024: 64‒79. (in Finnish, English summary).

- Cartron, J.-L. E., Triepke, F.J., Stahlecker, D.W., Arsenault, D.P., Ganey, J.L., Hathcock, C.D., Thompson, H.K., Cartron, M.C. & Calhoun, K.C. (2023). Climate Change Habitat Model Forecasts for Eight Owl Species in the Southwestern US. Animals, 13, 3770. [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. (2011). Population and range expansion of forest boreal owl (Glaucidium passerinum, Aegolius funereus, Strix uralensis, Strix nebulosa) in East-Central Europe. Vogelwelt 132: 93‒100.

- Kasprzyk, K. & Frątezak, W. (2025). Diet of solitary males Boreal Owls Aegolius funereus in the lowlands of the Bydgoszcz Forest (northern Poland). Ecological Questions 36(2): 1‒15. [CrossRef]

- Booms, T.L., Holroyd, G.L., Gahbauer, M.A., Trefry, H.E., Wiggins, D.A., Holt, D.W., Johnson, J.A., Lewis, S.B., Larson, M.D., Keyes, K.L. & Swengel, S. (2013). Assessing the Status and Conservation Priorities of the Short-eared Owl in North America. The Journal of Wildlife Management 9999. [CrossRef]

- Peak District National Park Authority (2025). Feature Assessment: Wildlife/Short-eared Owl. Reports.peakdistrict.gov.uk/cova/docs/assessment/wildlife/owl.html Accessed 18.09.2025.

- Penagos-López, A.P. & Esquivel Melo (2025). Impact of climate change on Andean owls in Colombia. Ornitologia Colombiana 27(i):49.

- Cruz-McDonnell, K. (2015). Negative effects of rapid warming and drought on reproductive dynamics and population size of an avian predator in the arid southwest. M.Sc. Thesis in the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds/21.

- Porro, C.M., Desmond, M.J., Savidge, J.A., Abadi, F., Cruz-McDonnell, K.K., Davis, J.L., Griebel, R.L., Ekstein, R.T. & Rodríguez, N.H. (2020). Burrowing Owl (Athene cunicularia) nest phenology influenced by drought on nonbreeding grounds. The Auk, 137: 1‒17. [CrossRef]

- Lehtiniemi, T. (2025). The occurrence of some threatened and fairly rare bird species in Finland in 2024. Linnut vuosikirja 2024: 80‒89. (In Finnish, English summary).

- McCabe, R.A., Aarvak, T., Aebischer, A., Bates, K., Bety,J., Bollache, L., Brinker, D., Driscoll. C., Elliott, K.H., Fitzgerald, G., Fuller, M., Gauthier, G., Gilg, O., Gousy-Leblanc, M., Holt, D., Jacobsen, K-O., Johnson, D., Kulikova, O., Lang, J., Lecomte, N., McClure, C., McDonald, T., Menyushina, I., Miller, E., Morozov, V.V., Øien, I.J., Robillard, A., Rolek, B., Sittler, B., Smith, N., Sokolov, A., Sokolova, N., Solheim, R., Soloviev, M., Stoffel, M., Weidensaul, S., Wiebe, K.L., Zazelenchuck, D. &Therrien, J.F. (2024). Status assessment and conservation priorities for a circumpolar raptor: the Snowy Owl Bubo scandiacus. Bird Conservation International 34, e41: 1‒11. [CrossRef]

- Domine, F., Gauthier, G., Vionnet, V., Fauteux, D., Dumont, M. & Barrère, M. (2018). Snow physical properties may be a significant determinant of lemming population dynamics in the high Arctic. Arctic Science 4: 813‒826. [CrossRef]

- Lamarre, V., Legagneux, P., Franke, A., Casajus, N., Currie, D.C., Berteaux, D. et al. (2018). Precipitation and ectoparasitism reduce reproductive success in an arctic-nesting top-predator. Scientific Reports 8, 8530. [CrossRef]

- Solheim, R., Jacobsen, K.-O., Øien, I.J., Aarvak, T. & Polojärvi, P. (2013). Snowy Owl nest failures caused by blackfly attacks on incubating females. Ornis Norvegica 36: 1‒5. [CrossRef]

- Penagos-López, A.P., Jiménez García, D. & Carlos, C.J. (2025). Protected areas as key to identifying and prioritizing climate refugia for the conservation of endemic Atlantic Forest owls. Ornitologia Colombiana 27(i): 53.

- Masoero, G. (2020). Food hoarding of an avian predator under food limitation and climate change. Ph.D. thesis, Annales Universitatis Turkuensis, Finland. Ser AII, Tom. 373.

- Class, B., Masoero, G., Terraube, J. & Korpimäki, E. (2021). Estimating the long-term repeatability of food-hoarding behaviours in an avian predator. Biology Letters 17: 202102286. [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.R. & Mikkola, H. (2019). Distribution trends of the Scops Owl in Britain and northern Europe. Scottish Birds 39(2): 168‒172.

- McKelvey, K. S. & Buotte, P. C. (2018). Effects of Climate Change on Wildlife in the Northern Rockies. In Halofsky, J. E. & Peterson, D. L. [Eds.], Climate Change and Rocky Mountain Ecosystems. Advances in Global Change Research 63: 143‒167. [CrossRef]

- Millon, A., Petty, S.J., Little, B., Gimenez, O., Cornulier, T. & Lambin, X. (2014). Dampening prey cycle overrides the impact of climate change on predator population dynamics: a long-term demographic study on tawny owls. Global Change Biology 20: 1770‒1781. [CrossRef]

- Lehikoinen, A., Ranta, E., Pietiäinen, H., Byholm, P., Saurola, P., Valkama, J., Huitu, O., Henttonen, H., and Korpimäki, E. (2011). The impact of climate and cyclic food abundance on the timing of breeding and brood size in four boreal owl species. Oecologia 165: 349‒355.

- Comay, O., Ezov, E., Yom-Tov, Y. & Dayan, T. (2022). In Its Southern Edge of Distribution, the Tawny Owl (Strix aluco) Is More Sensitive to Extreme Temperatures Than to Rural Development. Animals 12, 641. [CrossRef]

- Peery, M.Z., Guttiérez, R.J., Kirby, R., Ledee, O.E. & Layahe, W. (2011). Climate change and spotted owls: Potentially contrasting responses in the Southwestern United States. Global Change Biology 18: 865‒880.

- Berg, T., Solheim, R., Wernberg, T. & Østby, E. (2011). Lappuglene kom! [Great Grey Owls come! ]. Vår Fuglefauna 34(3): 108‒115. (in Norwegian).

- Keller, M., Chodkiewicz, T. & Woźniak, B. (2011). Great Grey Owl Strix nebulosa ‒ a new breeding species in Poland. Ornis Polonica 52: 150‒158. (In Polish, English summary).

- Ławicki, L., Abramčuk, A.V., Domashevsky, S.V., Paal, U., Solheim, R., Chodkiewicz, T. & Woźniak, B. (2013). Range extension of Great Grey Owl in Europe. Dutch Birding 35: 145‒154.

- Mikkola, H. (2010). Most Southern Great Grey Owl. Tyto; The International Owl Society XIII (4):8‒9.

- Mikkola, H. (2014a). Global Warming and Great Grey Owls. Tyto; The International Owl Society March 2014: 7‒8.

- Mikkola, H. (2014b). Der Einfluss der Erderwärmung auf die Ausbreitung von Bartkäuzen. Kauzbrief 26:22‒23. (in German).

- Mirski, P., Ivanov, A., Kitel, T. & Tumiel, T. (2021). The ranging behaviour of the Great Grey Owl Strix nebulosa: a pilot study using GPS tracking on a nocturnal species. Bird Study. [CrossRef]

- Solheim, R. (2009). Lappugla ‒ en klimaflyktning på vei sydover? [Great Grey Owl ‒ a climate fugitive on the way south?]. Vår Fuglefauna 32: 164‒169 (in Norwegian).

- Solheim, R. (2014). Lappugglan på frammarsch [Great Grey Owl on the march forward]. Vår Fågelvärld 73: 46‒50 (in Swedish).

- Vermouzek, Z., Krenek,D., Czerneková, B. (2005): Increase in numbers of Ural Owls (Strix uralensis) in the Beskydy Mts. (NE Czech Republic). Sylvia 40: 151-155.

- Šotnár, K. (2005): Nesting, diet and expansion of the Ural Owl (Strix uralensis) in the area of Horné Ponitrie (Central Slovakia). Buteo 14: 67‒68.

- Jenouvrier, S. (2013). Impacts of climate change on avian populations. Global Change Biology 19: 2036‒2057.

- Gilg, O., Kovacs, K.M., Aars, J., Fort, J., Gauthier, G., Grémillet, D., Ims, R.A., Meltofte, H., Moreau, J., Post, E., Schmidt, N.M., Yannic, G. & Bollache, L. (2012). Climate change and the ecology and evolution of Arctic vertebrates. Annals of the New York Academy of Science 1249: 166‒190. [CrossRef]

- Solheim, R., Jacobsen, K-O. & Øien, I.J. (2008). Snøuglenes vandringer: Ett år, tre ugler og ny kunnskap [Snowy Owl movements: one year, three owls and new knowledge]. Vår Fuglefauna 31(3): 102‒109. (In Norwegian).

- Mikkola, H. (2022a). Gufo delle nevi Bubo scandiacus. Pp. 192‒203, 391. In: Cauli, F., Galeotti, P. & Genero, F. (Eds.) Rapaci d’Italia e d’Europa. Edizioni Belvedere, Latina. (in Italian).

- Morozov, V.V., Rosenfeld, S.B., Rogova, N.V., Golovnyuk, V.V., Kirtaev, G.V. & Kharitonov, S.P. (2020). What is the number of snowy owls in the Russian Arctic? Ornithologia 44: 18‒25. (In Russian, English summary).

- Gasparini, J., Bize, P., Piault, R., Wakamatsu, K., Blount, J.D, Ducrest, A.L. & Roulin, A. (2009). Strength and cost of an induced immune response are associated with heritable melanin-based colour trait in female tawny owls. Journal of Animal Ecology 78: 608‒616.

- Gehlbach, F.R. (2012). Eastern screech-owl responses to suburban sprawl, warmer climate, and additional avian food in central Texas. Wilson Journal of Ornithology 124(3): 630‒633.

- Weidensaul, S. (2015). Owls of North America and The Caribbean. 333 p. Peterson Field Guides, New York.

- Koskenpato, K., Ahola, K., Karstinen, T. & Karell, P. (2016). Is the denser contour feather structure in pale grey than in pheomelanic brown tawny owls Strix aluco an adaptation to cold environments? Journal of Avian Biology 47(1): 1‒6. [CrossRef]

- Karell, P., Brommer, J.E., Ahola, K. & Karstinen, T. (2013). Brown tawny owls moult more flight feathers than grey ones. Journal of Avian Biology 44(3): 235‒244. [CrossRef]

- Mikkola, H. & Lamminmäki, J. (2014). Moult, ageing and sexing of Finnish Owls. 98 p. BirdLife Suomenselkä (in Finnish, English summary).

- Karell, P., Bensch, S., Ahola, K. & Asghar, M. (2017). Pale and dark morphs of tawny owls show different patterns of telomere dynamics in relation to disease status. – Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 284 (1859): 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Karell, P., Ahola, K., Karstinen, T., Valkama, J. & Brommer, J.E. (2011). Climate change drives microevolution in a wild bird. Nature Communications 2, 208. [CrossRef]

- Brommer, J.E., Ahola, K. & Karstinen, T. (2005). The colour of fitness: Plumage coloration and lifetime reproductive success in the tawny owl. Proceedings of the Royal Society B272, 1566: 935‒940.

- Koskenpato, K., Lehikoinen, A., Lindstedt, C. & Karell, P. (2020). Gray plumage color is more cryptic than brown in snowy landscapes in a resident color polymorphic bird. Ecology and Evolution 10: 1751‒1761. [CrossRef]

- Roulin, A. (2014). Melanin-based colour polymorphism responding to climate change. Global Change Biology 20: 3344–3350. [CrossRef]

- Roulin, A., Riols, C., Dijkstra, C. & Ducrest, A.L. (2001). Female plumage spottiness signals parasite resistance in the barn owl (Tyto alba). Behavioral Ecology 12(1): 103‒110.

- Potapova, P., Tyukavina, A., Turubanova, S., Hansen, M. C., Giglio, L., Hernandez-Serna, A., Lima, A., Harris, N. & Stolleb, F. 2025. Unprecedentedly high global forest disturbance due to fire in 2023 and 2024. PNAS 122(30), e2505418122. [CrossRef]

- McGinn, K., Zuckerberg, B., Jones, G. M., Wood, C. M., Kahl, S., Kelly, K. G., Whitmore, S. A., Kramer, H. A., Barry, J. M., Ng, E. & Peery, M. Z. (2025). Frequent, heterogenous fire supports a forest owl assemblage. Ecological Applications. 2025;35:e3080. [CrossRef]

- Lesmeister, D.B., Davis, R.J., Sovern, S.G. & Yang, Z. (2021). Northern spotted owl nesting forests as fire refugia: a 30-year synthesis of large wildfires. Fire Ecology 17:32. [CrossRef]

- Duchac, L. S., Lesmeister, D. B., Dugger, K. M. & Davis, R. J. (2021). Differential landscape use by forest owls two years after a mixed-severity wildfire. Ecosphere 12(10): e03770. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R. B., Eyes, S. A., Tingley, M. W., Wu, J. X., Stock, S. L., Medley, J. R., Kalinowski, R. S., Casas, A., Lima-Baumbach, M. & Rich, A. C. 2019.Short-term resilience of Great Gray Owls to a megafire in California, USA. The Condor, 121: 1-13. [CrossRef]

- metoffice.gov.uk.

- Barn Owl Trust: www.barnowltrust.org.uk/.

- Avotins, A., Avotins, A. Sr., Kerus, V. & Aunins, A. 2023.Numerical Response of Owls to the Dampening of Small Mammal Population Cycles in Latvia. Life, 2023, 13, 572. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R. J., Wellicome, T. I., Bayne, E. M., Poulin, R. G., Todd, L. D. & Ford, A. T. (2015). Extreme precipitation reduces reproductive output of an endangered raptor. Journal of Applied Ecology 52: 1500‒1508. [CrossRef]

- McDowell, M.C. & Medlin, G.C. (2009). The effects of drought on prey selection of the barn owl (Tyto alba) in the Strzelecki Regional Reserve, north-eastern South Australia. Australian Mammalogy 31: 47‒55. [CrossRef]

- Beemster, M. (2004). Drought and fires threaten the Barking Owls. https://science-health.csu.edu.au/herbarium/woodland-web/barking-owl Accessed18.09.2025.

- Steenseth, N.C., Mysterud, A., Ottersen, G., Hurrell, J.W., Chan, K-S.& Lima, M. (2002). Ecological effects of climate fluctuations. Science 297: 1292‒1296.

- John, A., Riat, A.K., Bhat, K.A., Ganie, S.A., Endarto, O., Nugroho, C., Handoko, H. & Wani, A.K. (2024). Adapting to climate extremes: Implications for insect populations and sustainable solutions. Journal for Nature Conservation 79: 1‒10. [CrossRef]

- Kausrud, K.L., Mysterud, A., Steen, H., Vik, J.O., Østbye et al. (2008). Linking climate change in lemming cycles. Nature 456: 93‒97.

- Korslund, L. & Steen, H. (2006). Small rodent winter survival: snow conditions limit access to food resources. Journal of Animal Ecology 75: 156‒166.

- Ims, R.A., Henden, J.A. & Killengreen, S.T. (2008). Collapsing population cycles. Trends of Ecological Evolution 23: 79‒86.

- Armarego-Marriott, T. (2020). Owls’ hoards rot. Nature Climate Change 10:802. [CrossRef]

- Marttinen, V. (2024). Lapinpöllö lensi Helsinkiin ja someraivo räjähti liekkeihin ‒ lintujärjestö joutui kieltämään pöllökuvien julkaisemisen. https:yle.fi/a/74-20078977?utm_medium=social&utm_source=ema… Accessed 14.03.2024 (in Finnish).

- Mikkola, H. (2022b). Allocco di Lapponia Strix nebulosa. Pp. 240‒251, 395‒396. In: Cauli, F., Galeotti, P. & Genero, F. (Eds.) Rapaci d’Italia e d’Europa. Edizione Belvedere, Latina. (in Italian).

- Boev, Z. & Mikkola, H. (2022). First Pleistocene Record of Great Grey Owl (Strix nebulosa Forster, 1772) in Bulgaria. Comptes rendus de l’Académie bulgare des Sciences 75(5): 680‒685. [CrossRef]

- Mysterud, I. (2016). Range extensions of some boreal owl species: comments on snow cover. Ice crusts and climate change. Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Research 48: 213‒219. [CrossRef]

- Solonen, T., 2006: Overwinter population change of small mammals in Southern Finland. Annales Zoologici Fennici 43: 295‒302.

- Marsh, P. & Woo, M.K. (1984).Wetting front advance and freezing of meltwater within a snow cover. 1. Observations in the Canadian Arctic. Water Resources Research 20: 1853‒1864.

- Visser, M.E., Both, C. & Lambrechts, M.M. (2004). Global climate change leads to mistimed avian reproduction. Pp. 89‒110. In: Møller, A.P., Fiedler, W. & Berthold, P. (Eds.) Effects of climate change on birds. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- Gura, K.B., Bedrosian, B., Patla, S. & Chalfoun, A.D. (2025). Variation in habitat selection by male Strix nebulosa (Great Gray Owls) across the diel cycle. Ornithology 142: 1‒14. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, B., L. Taylor, C. Wilsey, J. Wu, G.S. LeBaron, and G. Langham (2020a). North American birds require mitigation and adaptation to reduce vulnerability to climate change. Conservation Science and Practice 2:e242.

- Bateman, B., L. Taylor, C. Wilsey, J. Wu, G. S. LeBaron, and G. Langham (2020b). Risk to North American birds from climate change-related threats. Conservation Science and Practice 2:e243.

- Schneider, Z., Matics, E., Hoffmann, G., Laczi, M., Herczog, G. & Matics, R. (2025). The potential for climate change to intensify nest-site competition between two sympatric owl species. Ibis. [CrossRef]

- Mikkola, H. (1983). Owls of Europe. 397 p. A.D. & T. Poyser, Calton.

- Matics, R., Bank, L., Varga, S., Klein,A. & Hoffmann, G. (2008). Interspecific offspring killing in owls. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 95: 488‒494.

- Mikkola, H. (2026). Owls of the World. A Photographic Guide. 3rd Revised Edition. Bloomsbury/Christopher Helm, London.

- Wudu, K., Abegaz, A., Ayele, L. & Ybabe, M. (2023). The Impacts of Climate Change on Biodiversity Loss and Its Remedial Measures Using Nature Based Conservation Approach: A Global Perspective. Biodiversity and Conservation 32(12): 3681–3701. [CrossRef]

- Setsaas, T.H. (2024). Insects prefer cold winters with lots of snow. https://partner.sciencenorway.no/climate-change-insects-natural-sci… Accessed 23.9.2025.

- Hansson, L. & Henttonen, H. (1988). Rodent dynamics as community processes. Trends of Ecological Evolution 3: 195‒200. [CrossRef]

- Previtali, M.A., Lima, M., Meserve, P.L., Kelt, D.A. & Gutierrez, J.R. (2009). Population dynamics of two sympatric rodents in a variable environment: rainfall, resource availability, and predation. Ecology 90(7): 1996–2006. [CrossRef]

- Krebs, C.J., Boonstra, R., Gilbert, B.S., Kenney, A.J. & Boutin, S. (2019). Impact of climate change on the small mammal community of the Yukon boreal forest. Integrative Zoology 14: 528‒541. [CrossRef]

- Szpunar, G., Aloise, G., Mazzotti, S., Nieder, I. & Cristaldi, M. (2008). Effects of global climate change on terrestrial small mammal communities in Italy. Fresenius Environ Bulletin 17: 1526‒1533.

- Santoro, S., Sanchez-Suorez, C., Rouco, C., Palomo, L.J., Fernández, M.C., Kufner,M.B. & Moreno, S. (2017). Long-term data from a small mammal community reveal loss of diversity and potential effects of local climate change. Current Zoology 63(5): 515‒523. [CrossRef]

- Sharikov, A.V., Volkov, S.V., Sviridova, T.V. & Buslakov, V. V. (2019). Cumulative Effect of Trophic and Weather ‒ Climatic Factors on the Population Dynamics of the Vole-Eating Birds of Prey in Their Breeding Habitats. Biology Bulletin, 46(9):1097‒1107. [CrossRef]

- Kouba, M., Bartoš, L., Bartošová, J., Hongisto, K. & Korpimäki, E. (2020).Interactive influences of fluctuations of main food resources and climate change on long-term population decline of Tengmalm’s owls in the boreal forest. Scientific Reports 10:20429. [CrossRef]

- Lehikoinen, A., and Virkkala, R. (2016). North by northwest: climate change and directions of density shifts in birds. Global Change Biology 22: 1121‒1129.

- Bretagnolle, V. & Terraube, J. (2019). Predator-prey interactions and climate change. In: Dunn, P.O. & Møller, A.P. (Eds.) Effects of Climate Change on Birds. Second Edition. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, J. (2025). Key North Atlantic current is on the brink of collapsing ‒ plunging Europe into the Ice Age, scientists warn.https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-15165637/Key-No… Accessed 6.10.1605.

- Arellano Nava, B., Halloran, P.R., Boulton, C.A. & Lenton, T.M. (2024). Clams reveal the North Atlantic subpolar gyre has destabilised over recent decades. EGU General Assembly 2024, Vienna, Austria, 14‒19 April 2024, EGU24-20891. [CrossRef]

- Arellano Nava B,. Lenton, T.M., Boulton, C.A., Holmes, S., Scourse, J., Butler, P.G., Reynolds, D.J., Trofimova, T., Poitevin, P., Roman-Gonzáles, A. & Halloran, P.R. (2025). Recent and early 20th century destabilization of the subpolar North Atlantic recorded in bivalves. Sciences Advances 11: 1‒12. [CrossRef]

| Owl species |

2008‒2014 percentage of nests from total in S,C,N |

Average numbers of nests/region |

2018‒2024 percentage of nest from total in S,C,N |

Average numbers of nests/region |

Difference in two period percentages + or - |

Difference in annual average nest numbers |

| Aegolius funereus | S 7.9% C 74.4% N 17.7% TN 3050 |

S 35 C 324 N 77 TA 436 |

S 2.2% C 65.3% N 32.5% TN 1242 |

S 4 C 116 N 58 TA 178 |

S - 5.7% C - 9.1% N + 14.8% TP - 59.3% |

S - 31 C -208 N - 19 TD -258 |

| Asio flammeus | S 1.7% C 79.8% N 18.5% TN 346 |

S 0.9 C 39.4 N 9.1 TA 49.4 |

S 1.6% C 55% N 43.4% TN 129 |

S 0.3 C 10.1 N 8 TA 18.4 |

S - 0.1% C -24.8% N +24.9% TP -62.7% |

S - 0.6 C -29.3 N - 1.1 TD -31 |

| Asio otus | S 33.6% C 65.1% N 1.3% TN 2380 |

S 114.3 C 221.3 N 4.4 TA 340 |

S 51.3% C 47.1% N 1.6% TN 826 |

S 60.6 C 55.6 N 1.9 TA 118.1 |

S + 17.7% C - 18% N -7.5% TP -65.3% |

S - 53.7 C -165.7 N - 2.5 TD - 221.9 |

| Bubo bubo | S 48.6% C 48.9% N 2.5% TN 1215 |

S 84 C 85 N 4 TA 173 |

S 52.9% C 43.6% N 3.5% TN 953 |

S 72 C 59 N 5 TA 136 |

S + 4.3% C - 5.3% N + 1.0% TP - 21.6% |

S - 12 C - 26 N + 1 TD - 37 |

| Glaucidium passerinum | S 6.2% C 91.7% N 2.1% TN 2794 |

S 24.7 C 366.1 N 8.3 TA 399.1 |

S 10.5% C 85.6% N 3.9% TN 1170 |

S 17.6 C 143 N 6.6 TA 167.2 |

S + 4.3% C - 6.1% N + 1.8% TP - 58.1% |

S -7.1 C - 223.1 N - 1.7 TD - 231.9 |

| Strix aluco | S 46% C 54% N 0% TN 3045 |

S 200 C 235 N 0 TA 435 |

S 62.3% C 37.5% N 0% TN 4334 |

S 387 C 232 N 0 TA 619 |

S + 16.3% C - 16.5% N 0 TP + 29.7% |

S + 187 C - 3 N 0 TD + 184 |

| Strix nebulosa | S 2.8% C 81.3% N 15.9% TN 503 |

S 2 C 58.5 N 11.4 TA 71.9 |

S 3.7% C 57.3% N 39 TN 546 |

S 2.9 C 44.7 N 30.4 TA 78 |

S + 0.9% C - 24% N + 23.1% TP + 8.5% |

S + 0.9 C -13.8 N + 19 TD + 6.1 |

| Strix uralensis | S 10% C 85.8% N 4.2% TN 7435 |

S 106 C 912 N 44 TA 1062 |

S 11.6% C 82.4% N 6% TN 5613 |

S 93.1 C 660.7 N 48 TA 801.8 |

S + 1.6% C - 3.4% N + 1.8% TP - 24.5% |

S -12.9 C -251.3 N + 4 TD - 260.2 |

| Surnia ulula | S 0.5% C 15.2% N 84.3% TN 198 |

S 0.1 C 4.3 N 23.9 TA 28.3 |

S 0% C 9.9% N 90.1% TN 81 |

S 0 C 1.2 N 10.4 TA 11.6 |

S - 0.5% C - 5.3% N + 5.8% TP - 59.1% |

S - 0.1 C -3.1 N -13.5 TD - 16.7 |

| Owl species | Climate change impact(s) | Reference(s) |

| Aegolius acadicus | Predicted to lose 60% of its current breeding habitats in the Southwestern US (hereafter SW US) | 10 |

| Aegolius funereus | In Finland, a drastic habitat related decrease (nearly 60%) in population but the reduced numbers have shifted northwards (+ 15%) In SW US projected to experience the steepest climate change related habitat loss, up to 85% Interestingly, in Central Europe one of range increasing owls even in commercially used forests and in Scots pine Pinus sylvestris and not Spruce Picea sp: a keystone species (namely Norway Spruce Picea abies) for the owl in Finland |

Table 1. 10 11 and 12 |

| Asio flammeus | In Finland, second largest loss of the population (nearly 63%) and the largest shift northwards (+25%) Loss, fragmentation, and degradation of grass- and wetlands causing a range-wide long term decline in North America Sea level rising reduces winter habitats |

Table 1. 13 14 |

| Asio otus | In Finland, the largest population loss (over 65%) and remaining owls have shifted to south (nearly 18%) In SW US predicted to lose 70% of its current breeding habitats |

Table 1. 10 |

| Asio stygius | In Colombia, up to 22% habitat loss due to climate change | 15 |

| Athene cunicularia | One well studied population in central New Mexico declined from 52 pairs to 1 pair in 16 years due to increasing air temperature and extreme multiyear drought conditions Changes in phenology linked to climate change in N-America. Delays in breeding are due to food limitation caused by drought. Drought during migration also constrains energetic requirements, forcing owls to stop more frequently and for longer periods at stopover sites, resulting in delayed arrival on breeding grounds |

16 17 |

| Bubo bubo | In Finland, nearly 22% decrease in population but no clear region shifts |

Table 1. |

| Bubo scandiacus | In Finland, Snowy Owls breeds irregularly , average 2 nests per year (min 0 and max 10) ; the population change – 88% calculated by comparing the average during the first four and last four years between 2007‒2024 Global decline, however, is only 30% over the past three generations Milder and wetter climate in the Arctic has been fading lemming population cycles and increasing the risk for detrimental black fly (Simulidae) attacks on nestlings and breeding females |

18 19 20,21 and 22 |

| Bubo virginianus | Predicted to lose 35% of its current breeding habitats in SW US | 10 |

| Glaucidium jardinii | Up to 43% habitat loss due to climate change in Colombia | 15 |

| Glaucidium minutissimum | Climate change will have a negative impact in Brazil | 23 |

| Glaucidium gnoma | Predicted to lose 75% of its current breeding habitats in SW US | 10 |

| Glaucidium passerinum | In Finland, nearly 60% population decline but no clear region shifts Climate change lowers food store quality when autumn rains and mild winters rot food hoards |

Table 1. 24 and 25 |

| Megascops albogularis | Up to 41% habitat loss due to climate change in Colombia | 15 |

| Megascops atricapilla | Climate change will have a negative impact in Brazil | 23 |

| Megascops ingens | In Colombia, significant habitat loss due to climate change but no percentage given | 15 |

| Megascops kennicottii | Predicted to lose 55% of its current breeding habitats in SW US | 10 |

| Megascops sanctaecatarinae | Climate change will have a negative impact in Brazil | 23 |

| Megascops trichopsis | Predicted to lose up to 60% of its current breeding habitats in SW US | 10 |

| Otus scops | Northward moving population in Britain and Europe | 26 |

| Psiloscops flammeolus | As cavity nester associated with large diameter trees, climate change would most likely be through disturbance processes that remove large trees. Shifts to denser forest structure would be a concern, but this is unlikely because drought and wildfire are projected to increase throughout the Northern Rockies In SW US projected to experience the steepest climate change related habitat loss, up to 85% |

27 10 |

| Pulsatrix koeniswaldiana | In Brazil, climate change will have a negative impact but no percentage given | 23 |

| Pulsatrix melanota | Up to 44% habitat loss due to climate change in Colombia | 15 |

| Strix albitarsis | In Colombia, significant habitat loss due to climate change but no percentage given | 15 |

| Strix aluco | Dampening vole cycles may drive this owl towards extinction from Northern England In Finland, advance in breeding dates have been noted Only owl in Finland with clearly increased population (+30%) but this far no northward expansion happening In Israel, climate change, which would increase spring temperatures and decrease rainfall, is a larger threat to this owl than rural development. |

28 29 Table 1. 30 |

| Strix hylophila | In Brazil, climate change will have a negative impact | 23 |

| Strix occidentalis | In SW US negative associations between warm, dry conditions and seemingly less heat-tolerant | 31 |

| Strix nebulosa | In Europe, population moving southward and westward against the climate change expectations In Finland, the second owl with a clear population increase (+ 8.5%) and this material would indicate population move between Central and North Finland (C-24% and N +23%) |

32‒40 Table 1. |

| Strix uralensis | In Finland, less alarming population decrease (less than 25%) and no clear sift to south or north. Climate change may advance the breeding in Finland– deep snow depth has delayed breeding In Slovakia, a positive population and range trend (from the east to the west), but reason may not be climate related |

Table 1. 29 41 and 42 |

| Surnia ulula | In Finland, almost 60% reduction in breeding population, remaining owls moving northwards (+6%) |

Table 1. |

| Tyto alba | Snowrich winters are part of non-linear climate change and can be dramatic to adult and juvenile barn owls in Switzerland | 43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).