1. Introduction

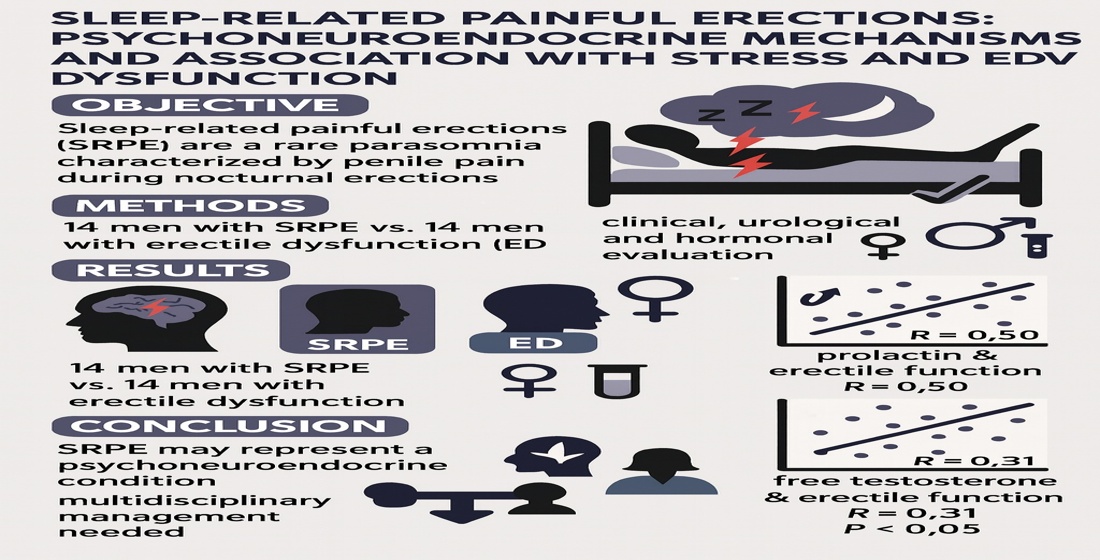

Sleep-related painful erections (SRPE) are a rare and underrecognized sleep disorder characterized by nocturnal erections associated with penile pain, typically during REM sleep [

1]. During wakefulness, erections are painless and otherwise normal. SRPE can lead to sleep disruption, fatigue, sexual avoidance, and anxiety. Although several hypotheses exist, the pathophysiology remains unclear, with proposed mechanisms involving dysregulation of REM sleep, increased sympathetic tone, sacral root hypersensitivity, and psychogenic or endocrine factors [

2]. Organic causes can be hypertension, obesity, hormonal disorders or diabetes mellitus [

3]. Diseases of the urinary tract, especially the prostate, are also an important factor. The above causes may not solely be responsible. In fact, stress, psychosocial trauma or anxiety can be the main problem. Stress associated with the nocturnal tomescense pain can lead to an increase of prolactin in the blood, which can subsequently affect the levels of serotonin and also dopamine.

There are several hormones which can affect Erectile function. The main hormones are testosterone, prolactin and a hormone which stimulates the thyroid gland. However, there are many others that could influence sexual functioning, such as the luteinizing hormone (LH), which stimulates the testes to produce testosterone, or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) which is an adrenal androgen that can, in turn, be a potential precursor to other androgens, for example androstenedione and testosterone.

Most studies on SRPE originate from Europe, notably the Netherlands, France, and Italy, describing only small case series [

4]. The prevalence remains unknown but is likely underestimated due to diagnostic challenges and stigma. This study aimed to examine psychometric and hormonal correlates of SRPE and to explore possible neuroendocrine mechanisms linking stress, prolactin secretion and erectile dysfunction.

2. Methods

This was a case–control study conducted between 2020 and 2023 at two academic sexology centers in the Czech Republic. The SRPE group included 14 men diagnosed with SRPE based on polysomnographic recordings and nocturnal penile tumescence monitoring. The control group included 14 men with erectile dysfunction but no SRPE history. As part of the methodology, we considered 3-4 episodes of painful nocturnal erections within a period of one week for a period of one month to be clinically relevant [

5]. This diagnosis was determined by a sexologist in collaboration with a somnologist.

Inclusion criteria: adult men ≥18 years with confirmed SRPE or ED. Exclusion criteria: diabetes mellitus, thyroid disorders, neurological or major psychiatric diseases, use of antidepressants or antipsychotics, structural urological abnormalities, or pituitary disease.

Outcomes: erectile function (IIEF-5) and stress/trauma symptoms (TSC-40). Hormonal assays included total and free testosterone, prolactin, LH, SHBG, DHEA-S, TSH, and PSA. Morning fasting venous blood samples were collected at 8:00–9:00 a.m. All analyses were performed using certified laboratory protocols.

Questionnaire of Erectile Function

International Index of Erectile Function – 5 items (IIEF-5):

A standardized tool that is validated for the Czech version and is used to assess erectile function, where a lower score indicates more severe dysfunction [

6].

Questionnaire of the Trauma Symptoms Checklist (TSC-40)

The questionnaire is validated for the Czech version. It measures a broad range of psychological symptoms related to trauma and stress, including depression, anxiety, insomnia, dissociation and sexual difficulties. Responses are rated on a four-point Likert scale with a total score ranging from 0 to 120[

7].

Hormonal and Biochemical Assessment

There are several hormones which can affect erectile function. The main hormones are testosterone, prolactin and a hormone which stimulates the thyroid gland. However, there are many others that could influence sexual functioning, such as the luteinizing hormone (LH), which stimulates the testes to produce testosterone, or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) which is an adrenal androgen that can, in turn, be a potential precursor to other androgens, for example androstenedione and testosterone. Prolactin (PRL) is a peptide hormone. This is produced (and secreted) by the anterior lobe of the pituitry gland. This, in turn, affects sexual desire as well as testosterone levels and has an influence on the target tissue. The level of PRL increases with increasing mental stress. However, the production of PRL is primarily surpressed by dopamine. Hyperprolactinemia is described as an increase in prolactin in blood. This can, in turn, lead to problems with libido, erectile dysfunction, even sometimes premature ejaculation and possibly fertility disorders [

5]. Testosterone is the primary male sex hormone. It influences the development of the prostate and testes and affects sexual behavior. There is some evidence that testosterone has an important role in erectile function and reduction can damage penile tissue [

5]. Testosterone is bound to albumin and at about 44% to the Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (SHBG). SHBG is a glycoprotein which is mainly made up of estrogens and androgens. It plays an important role in the regulation of steroids. Approximately 1 to 2% is unbound, or free‘ which, in biological terms, means active and can activate receptors in cells [

8]. The thyroid hormones are produced in the glandular follicles. Circulating Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) is free to act on the TSH receptors [

9]. Sexual function, fertility and some metabolic processes are affected by Thyroid Hormones [

10]. Prostate specific antigen (PSA) is a protein that is formed in prostate cells. PSA affects sperm motility and helps liquefy the ejaculate. Elevated levels of PSA may indicate inflammation or, in the worst case, prostate cancer.

Venous blood samples were collected in the early morning (approximately two hours after awakening) to minimize diurnal variation. Samples were kept at 4°C and processed within 20 minutes.

Analyses included:

• Prolactin (PRL) – reference range 2.1–17.7 µg/L

• Total and free testosterone (TT, free T) – normal TT range: 6–27 nmol/L

• Luteinizing hormone (LH) – reference range: 1.8–8.6 IU/L

• Sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) – normal range: 14–71 nmol/L

• Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) – normal range: 3.6–12 nmol/L

• Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) – reference range: 0.3–4.9 mIU/L

• Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) – reference range: 0.0–1.4 µg/L All assays were performed using standardized laboratory protocols.

Statistical analysis and Power Calculation:

All analyses were performed using non-parametric methods because data did not meet the assumptions of normality (as assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test)[

11]. Data were analyzed using R version 4.3.3. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median [IQR]. Participants were divided into two independent groups according to the presence or absence of nocturnal painful erections. Between-group differences in hormone levels (prolactin, testosterone, FSH, LH), erectile function scores (IIEF-5), and trauma/stress symptoms (TSC-40) were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Associations between continuous or ordinal variables (hormone levels, IIEF-5, and TSC-40 scores) were analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ). All tests were two-tailed and a p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) unless stated otherwise.

A post hoc power analysis was performed to estimate the sensitivity of the study to detect medium-to-large effects (α = 0.05, two-tailed). Given the sample size (n = 14 per group), the estimated power ranged between 0.70 and 0.80 for effect sizes of r ≈ 0.5 (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.6). The design thus provided adequate statistical sensitivity for moderate-to-strong associations but limited power for smaller effects.

3. Results

Significant Spearman correlations were found between prolactin and IIEF-5 (R = 0.50, p < 0.05), between TSC-40 and IIEF-5 (R = 0.55, p < 0.05), and between free testosterone and IIEF-5 (R = 0.31, p < 0.05). No significant correlations were observed for LH, TSH, SHBG, DHEA-S, or PSA.

In the SRPE group, no somatic or psychiatric disorders were detected despite elevated prolactin and free testosterone levels. Erectile dysfunction was confirmed exclusively by history taking, physical examination, and questionnaire assessment (IIEF-5). Prostate ultrasonography and penile–scrotal Doppler examination showed no pathological findings.

The control group, consisting of men with erectile dysfunction but without sleep-related pain, had a mean IIEF-5 score of 14.00 ± 3.37 and a mean TSC-40 score of 42.43 ± 9.51. Mean TT was 17.72 ± 6.44 nmol/L, fT 141.61 ± 56.51 pmol/L, SHBG 34.00 ± 16.95 nmol/L, DHEA-S 11.09 ± 2.64 µmol/L, TSH 1.20 ± 0.64 mIU/L, PRL 10.94 ± 5.92 µg/L, LH 1.35 ± 0.65 mIU/L, and PSA 1.39 ± 1.15 µg/L. No significant correlations were found in the control group between IIEF-5 and TSC-40 (z = –1.573, p = 0.116) or between TSC-40 and PRL (z = –1.704, p = 0.089).

Taken together, these results indicate that in men with sleep-related painful erections (SRPE), higher prolactin levels and greater severity of stress-related symptoms are associated with poorer erectile function, while such associations are absent in men with erectile dysfunction (ED) without SRPE.

4. Discussion

Our findings confirm that SRPE represents a complex psychoneuroendocrine condition rather than a purely urological disorder. The correlations between prolactin, stress indicators, and erectile dysfunction support the hypothesis of stress-related hyperprolactinemia contributing to impaired sexual function [

12]. Previous European studies by van Driel et al. and Liguori et al. similarly suggested an interplay between REM sleep mechanisms, endocrine function, and emotional stress. Increased prolactin during REM episodes may alter dopaminergic inhibition of sexual reflexes, enhancing pain perception and arousal-related discomfort [

13]. Importantly, the use of both Spearman correlations and the Mann–Whitney U test in this study addresses different hypotheses: correlations evaluate associations among variables within a group, while the Mann–Whitney U test compares distributions between groups. In the revised analysis, we clearly separate these approaches and interpret them appropriately. Our study demonstrates that men with SRPE exhibit a distinctive pattern of hormonal and psychological associations not present in men with erectile dysfunction alone. Elevated prolactin levels were significantly correlated with both erectile function and stress measures, suggesting a stress-related neuroendocrine mechanism.

Previous literature has highlighted the complex role of prolactin in male sexual health. Chronic stress can increase prolactin secretion, which may suppress libido and interfere with erectile mechanisms. Rastrelli reported a possible relationship between prolactin levels, sexual dysfunction, and even male fertility [

14]. The association between depressive symptoms and anxiety in men with sexual dysfunction was also observed in the European population. Our results confirm the relationship between erectile dysfunction, elevated blood prolactin levels, and symptoms of trauma along with psychosocial stress. These findings underscore the etiologic role of prior stressful experiences in the development of erectile dysfunction [

15]. There is clear evidence that intimate relationships can be very sensitive and can subsequently cause sexual dysfunction, especially erectile dysfunction [

12]. Prolactin is considered a hormone that can be affected by stress and therefore increases the likelihood of erectile dysfunction [

16].

Before the diagnosis of SRPE, most patients reported sleep disorders, nocturia, fear, and anxiety; two patients exhibited symptoms of depression. Even when awake and pain-free, all patients described fear of sexual activity, avoidance behavior, and partner-related sexual difficulties [

17]. In our study, it was not possible to clearly demonstrate the cause of SRPE; however, our results suggest that SRPE may be linked to stress, anxiety, and depression, which can subsequently lead to hyperprolactinemia, psychogenic erectile dysfunction, and disturbances in partner sexual relationships. In the control group, where patients suffered from erectile dysfunction but did not report pain during erection, we did not find a significant increase in stress, although prolactin levels were elevated in some individuals. A positive correlation between erectile dysfunction, stress, and prolactin was not observed, as was the case in the SRPE group.

Based on these findings, we offered affected patients a combination therapy of pregabalin, low-dose prolactin-lowering bromocriptine mesylate, and sildenafil citrate (PDE-5 inhibitor) to address pain, fear, and erectile dysfunction. Treatment began with pregabalin 150 mg per day in two divided doses, later increased to 300 mg daily after one month. Three patients reported reduced pain sensation; in another eleven, the dose was titrated up to 600 mg daily, with good results after six months. This dose was continued for an additional six months. Prolactin levels were gradually reduced with bromocriptine mesylate 2.5 mg taken in the evening, which also improved sleep quality. Erectile dysfunction was treated with sildenafil citrate 100 mg before sexual activity, with good initial effect.

Clinical implications include the need for integrated management that combines sleep hygiene, stress reduction, and pharmacotherapy (e.g., bromocriptine, pregabalin, or PDE-5 inhibitors). Future studies should expand the sample size, include neuroimaging and circadian hormone profiling, and test targeted interventions.

Sexual dysfunctions in men are complex disorders that consist of organic and psychogenic components. The most common sexual dysfunction is erectile dysfunction. It is the inability to achieve or maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual performance. This disorder can be caused by high blood pressure, heart disease, vascular problems, psychological and hormonal factors such as problems with testosterone and prolactin levels. In this study, we tested the relationship between erectile dysfunction, hyperprolactinemia and psychosocial stress. Clinical examinations of 60 patients with erectile dysfunction, which also included psychosocial stress, focussed on patient history, comprehensive sexological examination, biochemical analyses of serum prolactin, total testosterone and thyroid-stimulating hormone with psychometric evaluation of erectile function and a checklist of trauma symptoms (TSC-40). The results show significant Spearman correlations of psychometric evaluation of erectile function with prolactin (R = .50) and results of the trauma checklist score (R = .55) and significant Spearman correlations between TSC-40 and prolactin (R = .52). This result indicates a significant relationship between erectile dysfunction, hyperprolactinemia and stress symptoms in men REM sleep rebound is a common behavioural response to some stressors and represents an adaptive coping strategy. Animals submitted to multiple, intermittent, footshock stress (FS) sessions during 96h of REM sleep deprivation (REMSD) display increased REM sleep rebound (when compared to the only REMSD ones, without FS), which is correlated to high plasma prolactin levels. To investigate whether brain prolactin plays a role in stress-induced REM sleep rebound two experiments were carried out. In experiment 1, rats were either not sleep-deprived (NSD) or submitted to 96h of REMSD associated or not to FS and brains were evaluated for PRL immunoreactivity (PRL-ir) and determination of PRL concentrations in the lateral hypothalamus and dorsal raphe nucleus. In experiment 2, rats were implanted with cannulas in the dorsal raphe nucleus for prolactin infusion and were sleep-recorded. REMSD associated with FS increased PRL-ir and content in the lateral hypothalamus and all manipulations increased prolactin content in the dorsal raphe nucleus compared to the NSD group. Prolactin infusion in the dorsal raphe nucleus increased the time and length of REM sleep episodes 3h after the infusion until the end of the light phase of the day cycle. Based on these results we concluded that brain prolactin is a major mediator of stress-induced REMS. The effect of PRL infusion in the dorsal raphe nucleus is discussed in light of the existence of a bidirectional relationship between this hormone and serotonin as regulators of stress-induced REM sleep rebound.

5. Conclusions

According to current literature, the main cause of Sleep-Related Painful Erections (SRPE) may include obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) as well as psychogenic factors, increased androgen levels, and disturbances in neuroendocrine regulation leading to altered pain thresholds during the REM phase of sleep. Subsequent erectile dysfunction without algia is probably secondary to the fear and pain that accompany SRPE episodes.

Our study indicates that there may be a relationship between painful sleep-related erections (SRPE), stress, hyperprolactinemia, and erectile dysfunction in the examined men. Unfortunately, SRPE remains a rare and underrecognized disorder, which limited the size of our patient cohort. To date, no large-scale clinical studies have verified the etiology or evaluated effective treatment options for this condition [

17].

A foreign study has mentioned baclofen as one of the potential treatment options, primarily indicated for spasticity of skeletal muscles, multiple sclerosis, and spinal cord injuries or tumors [

4]. In our cohort, patients were evaluated in a sleep laboratory to assess possible psychogenic contributions after negative findings in urology, neurology, and orthopedics. Psychogenic factors are often associated with peripheral and central neuropathic pain of unclear etiology, and pregabalin remains indicated for generalized anxiety disorder and related syndromes [

18]

This study highlights the potential interplay between SRPE, psychological stress, and hormonal imbalance in the pathogenesis of erectile dysfunction. SRPE appears to contribute to secondary erectile dysfunction through mechanisms linking stress, prolactin dysregulation, and fear conditioning. Recognition of SRPE as a psychoneuroendocrine disorder may improve both diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic outcomes.

The treatment approach used in our cohort—consisting of pregabalin, bromocriptine mesylate, and PDE-5 inhibitors—was followed for one year and can be considered partially effective. The observed improvement supports the relevance of an integrated therapeutic strategy combining neuroendocrine modulation, stress reduction, and sleep regulation. In the future, psychotherapy may also represent a valuable adjunct to pharmacotherapy, particularly in addressing the psychosocial dimensions of SRPE.

Early identification and multidisciplinary management are essential for reducing chronic distress and preserving sexual health in affected individuals. Further research should focus on larger patient samples, neuroendocrine monitoring, and long-term follow-up to better define underlying mechanisms and optimize treatment strategies. We anticipate that this pilot study may contribute to shaping future diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to SRPE.

Author Contributions

LF- Study Design, Writing Original, Data Analysis. JL - Manuscript Review and Editing. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study was unsupported.

Declarations of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethical Committee's (ec) decision No.226/20.

Funding

Authors declare that there was no financial assistance to support this study.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study can be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- S. G. Wong, Y. Vorakunthada, J. Lee-Iannotti, and K. G. Johnson, “Sleep-related motor disorders,” Handb. Clin. Neurol., vol. 195, pp. 383–397, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Hu et al., “[Diagnosis and management of sleep-related painful erections:A report of 9 cases],” Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue Natl. J. Androl., vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 330–334, Apr. 2016.

- G. Corona, G. Rastrelli, S. Filippi, L. Vignozzi, E. Mannucci, and M. Maggi, “Erectile dysfunction and central obesity: an Italian perspective,” Asian J. Androl., vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 581–591, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Vreugdenhil, A. C. Weidenaar, I. J. de Jong, and M. F. van Driel, “Sleep-Related Painful Erections: A Meta-Analysis on the Pathophysiology and Risks and Benefits of Medical Treatments,” J. Sex. Med., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 5–19, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Mulhall, I. Goldstein, A. G. Bushmakin, J. C. Cappelleri, and K. Hvidsten, “Validation of the erection hardness score,” J. Sex. Med., vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 1626–1634, Nov. 2007. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Rosen, A. Riley, G. Wagner, I. H. Osterloh, J. Kirkpatrick, and A. Mishra, “The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction,” Urology, vol. 49, no. 6, pp. 822–830, June 1997. [CrossRef]

- J. Briere, “Dissociative symptoms and trauma exposure: specificity, affect dysregulation, and posttraumatic stress,” J. Nerv. Ment. Dis., vol. 194, no. 2, pp. 78–82, Feb. 2006. [CrossRef]

- L. Fiala and J. Lenz, “Psychosocial stress, somatoform dissociative symptoms and free testosterone in premature ejaculation,” Andrologia, vol. 52, no. 11, p. e13828, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Zimmermann, “Iodine deficiency,” Endocr. Rev., vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 376–408, June 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. Carani et al., “Multicenter study on the prevalence of sexual symptoms in male hypo- and hyperthyroid patients,” J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., vol. 90, no. 12, pp. 6472–6479, Dec. 2005. [CrossRef]

- F. Habibzadeh, “Data Distribution: Normal or Abnormal?,” J. Korean Med. Sci., vol. 39, no. 3, p. e35, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Fiala, J. Lenz, and R. Sajdlova, “Effect of increased prolactin and psychosocial stress on erectile function,” Andrologia, vol. 53, no. 4, p. e14009, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Machado, M. R. Rocha, and D. Suchecki, “Brain prolactin is involved in stress-induced REM sleep rebound,” Horm. Behav., vol. 89, pp. 38–47, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Rastrelli, G. Corona, and M. Maggi, “The role of prolactin in andrology: what is new?,” Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord., vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 233–248, Sept. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Brotto et al., “Psychological and Interpersonal Dimensions of Sexual Function and Dysfunction,” J. Sex. Med., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 538–571, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Z.-H. Xu et al., “Effect of prolactin on penile erection: a cross-sectional study,” Asian J. Androl., vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 587–591, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lu, J. Zhang, H. Su, Y. Xiao, B. Guo, and H. Li, “Improvement of associated symptoms using combined therapy in 44 patients with sleep-related painful erection during 1-year follow up,” Andrologia, vol. 54, no. 8, p. e14472, Sept. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Baldwin, K. Ajel, V. G. Masdrakis, M. Nowak, and R. Rafiq, “Pregabalin for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: an update,” Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat., vol. 9, pp. 883–892, 2013. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).