Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

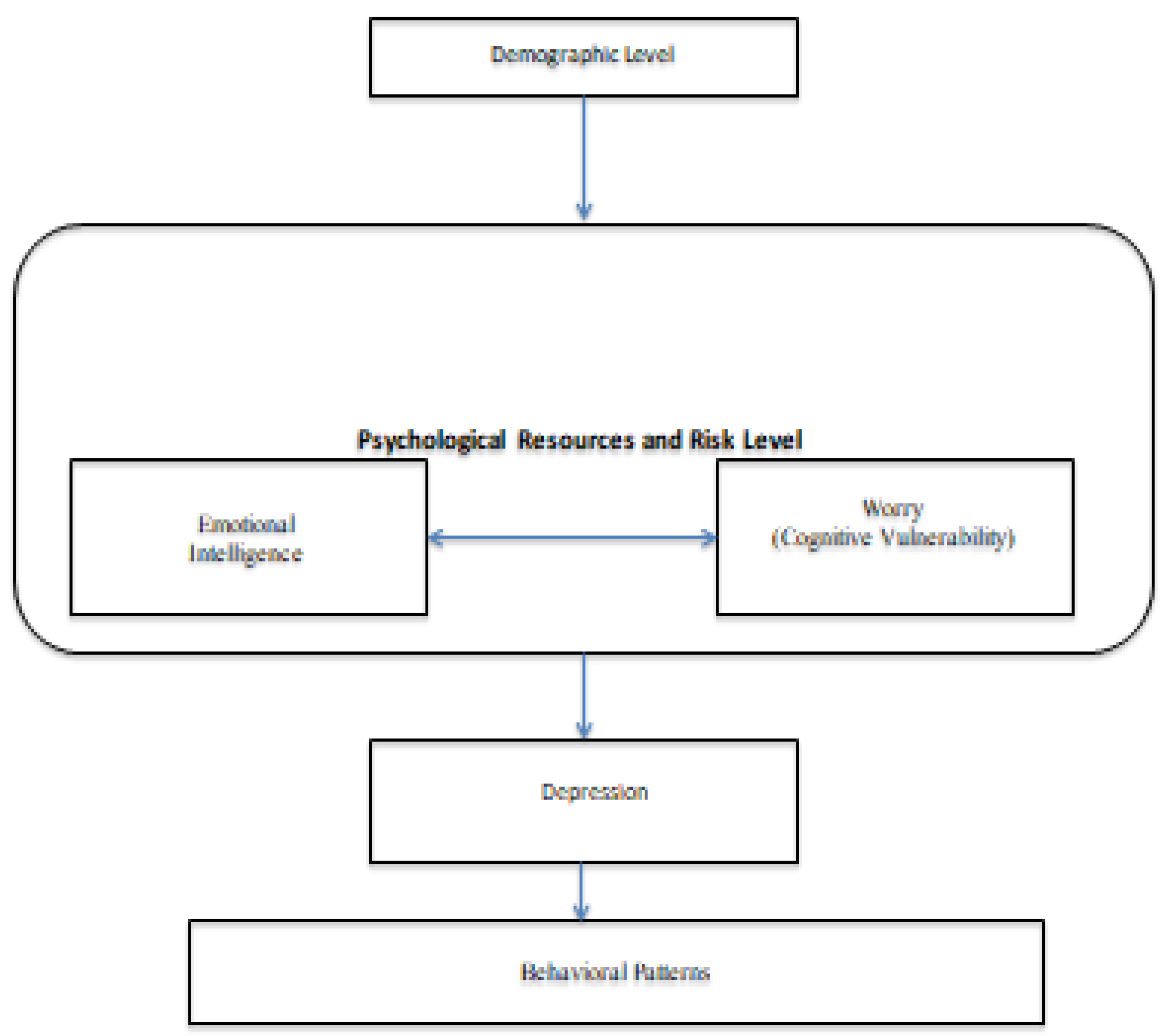

1. Introduction

1.1. The Role of Worry and Emotional Intelligence in Depression

- H1a: Worry could be positively related to affective factors of depression both in clinical and non-clinical samples;

- H1b: Worry could be positively related to somatic factor of depression both in clinical and non-clinical samples.

- H1c: EI could be negatively related to affective factor of depression both in clinical and non-clinical samples;

- H1d: EI could be negatively related to somatic factors of depression both in clinical and non-clinical samples;

- H1e: EI could be negatively related to worry both in clinical and non-clinical samples.

- H2a: We examine whether the posterior estimates supported a relationship between worry and the affective factor of depression in both participants above BDI threshold and non-clinical sample;

- H2b: Worry was expected to contribute to the explanation of the somatic factor of depression in both participants above BDI threshold and non-clinical sample;

- H2c: Both worry and were expected to be associated with the affective factor of depression in both participants above BDI threshold and non-clinical sample;

- H2d: Both worry and EI were expected to contribute to the explanation of the somatic factor of depression in both participants above BDI threshold and non-clinical sample.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.2. Statistical Analyses

- -

- 1–3: weak evidence

- -

- 3–10: moderate evidence

- -

- 10–30: strong evidence

- -

- 30–100: very strong evidence

- -

- >100: extreme evidence for one model over another.

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdellatif, S. A., Hussien, E. S. S., Hamed, W. E., & Zoromba, M. A. (2017). Relation between emotional intelligence, socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with depressive disorders. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 31(1), 13–23. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, A., Hosseini, S. M. E. N., Motalebi, S. A., & Talib, M. A. (2013). Examining the association between emotional Intelligence with depression among Iranian boy students. Depression, 2(3).

- Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96(2), 358–372. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar-Danesh, N., & Landeen, J. (2007). Relation between depression and sociodemographic factors. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 1, 1–9.

- Albert, P. R. (2015). Why is depression more prevalent in women? Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 40(4), 219–221.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision. American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Andrei, F., Smith, M. M., Surcinelli, P., Baldaro, B., & Saklofske, D. H. (2016). The trait emotional intelligence questionnaire: Internal structure, convergent, criterion, and incremental validity in an Italian sample. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 49(1), 34–45. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, V. H., & Borkovec, T. D. (1988). The differential effects of inductions of worry, somatic anxiety, and depression on emotional experience. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 19(1), 21–26. [CrossRef]

- Aradilla-Herrero, A., Tomás-Sábado, J., & Gómez-Benito, J. (2014). Associations between emotional intelligence, depression and suicide risk in nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 34(4), 520–525. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A. R., Galligan, R. F., & Crichley, C. R. (2011). Emotional intelligence and psychological resilience to negative life events. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(3), 331–336. [CrossRef]

- Balsamo, M. (2010). Anger and depression: Evidence of a possible mediating role for rumination. Psychological Reports, 106(1), 3–12. [CrossRef]

- Balsamo, M., & Saggino, A. (2007). Test per l'assessment della depressione nel contesto italiano: Un'analisi critica [Depression assessment questionnaires in the Italian context: A critical analysis]. Psicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale, 13(2), 167–199. https://hdl.handle.net/11564/110634.

- Balsamo, M., & Saggino, A. (2013). TDI: Teate depression inventory: Manuale. Hogrefe.

- Balsamo, M., Giampaglia, G., & Saggino, A. (2014). Building a new Rasch-based self-report inventory of depression. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 153–165. [CrossRef]

- Balsamo, M., Carlucci, L., Sergi, M. R., Klein Murdock, K., & Saggino, A. (2015). The mediating role of early maladaptive schemas in the relation between co-rumination and depression in young adults. PLoS One, 10(10), e0140177. [CrossRef]

- Batool, S. S., & Khalid, R. (2009). Low emotional intelligence: A risk factor for depression. Journal of Pakistan Psychiatric Society, 6(2), 65–72.

- Batselé, E., Stefaniak, N., & Fantini-Hauwel, C. (2019). Resting heart rate variability moderates the relationship between trait emotional competencies and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, 69–74. [CrossRef]

- Bauld, R., & Brown, R. F. (2009). Stress, psychological distress, psychosocial factors, menopause symptoms and physical health in women. Maturitas, 62(2), 160–165. [CrossRef]

- Beach, S. R., & Whisman, M. A. (2012). Affective disorders. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 38(1), 201–219. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. (1996). Beck depression inventory–II [Database record]. APA PsycTests. [CrossRef]

- Bergh, D. V. D., Clyde, M. A., Gupta, A. R. K. N., de Jong, T., Gronau, Q. F., Marsman, M., ... Wagenmakers, E. J. (2021). A tutorial on Bayesian multi-model linear regression with BAS and JASP. Behavior Research Methods, 1–21.

- Bishop, C. M., & Tipping, M. E. (2003). Bayesian regression and classification. Nato Science Series sub Series III Computer And Systems Sciences, 190, 267–288.

- Borkovec, T. D., Robinson, E., Pruzinsky, T., & DePree, J. A. (1983). Preliminary exploration of worry: Some characteristics and processes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21(1), 9–16. [CrossRef]

- Calmes, C. A., & Roberts, J. E. (2007). Repetitive thought and emotional distress: Rumination and worry as prospective predictors of depressive and anxious symptomatology. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 31, 343–356. [CrossRef]

- Cenat, J. M., Farahi, S. M. M. M., Dalexis, R. D., Darius, W. P., Bekarkhanechi, F. M., Poisson, H., Broussard C., Ukwu G., Auguste E., Nguyen D. D., Sehabi G., Furyk S. E., Gedeon A. P., Onesi O., El Aouame A. M., Khodabocus S. N., Shah M. S., & Labelle, P. R. (2022). The global evolution of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 315, 70–95. [CrossRef]

- Chahal, R., Gotlib, I. H., & Guyer, A. E. (2020). Research Review: Brain network connectivity and the heterogeneity of depression in adolescence–a precision mental health perspective. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(12), 1282–1298. [CrossRef]

- Ciarrochi, J., Deane, F. P., & Anderson, S. (2002). Emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between stress and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(2), 197–209. [CrossRef]

- Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 316–336. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J. B., Ford, M., Heary, S., Rodgers, J., & Freeston, M. H. (2017). The relationship between negative problem orientation and worry: A meta-analytic review. Psychopathology Review, 4(3), 319–340. [CrossRef]

- Dar, K. A., Iqbal, N., & Mushtaq, A. (2017). Intolerance of uncertainty, depression, and anxiety: Examining the indirect and moderating effects of worry. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 29, 129–133. [CrossRef]

- Davey, G. C., Hampton, J., Farrell, J., & Davidson, S. (1992). Some characteristics of worrying: Evidence for worrying and anxiety as separate constructs. Personality and Individual Differences, 13(2), 133–147.

- Davis, S. K., & Humphrey, N. (2012). Emotional intelligence predicts adolescent mental health beyond personality and cognitive ability. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 144–149. [CrossRef]

- de Jong-Meyer, R., Beck, B., & Riede, K. (2009). Relationships between rumination, worry, intolerance of uncertainty and metacognitive beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(4), 547–551. [CrossRef]

- de Vito, A., Calamia, M., Greening, S., & Roye, S. (2019). The association of anxiety, depression, and worry symptoms on cognitive performance in older adults. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 26(2), 161–173. [CrossRef]

- De Vlieger, P., Crombez, G., & Eccleston, C. (2006). Worrying about chronic pain: An examination of worry and problem solving in adults who identify as chronic pain sufferers. Pain, 120(1–2), 138–144. [CrossRef]

- Delhom, I., Gutierrez, M., Mayordomo, T., & Melendez, J. C. (2018). Does emotional intelligence predict depressed mood? A structural equation model with elderly people. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 1713–1726. [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. (2011). Emotional Intelligence: New perspectives and applications. In Tech.

- Downey, L. A., Johnston, P. J., Hansen, K., Schembri, R., Stough, C., Tuckwell, V., & Schweitzer, I. (2008). The relationship between emotional intelligence and depression in a clinical sample. European Journal of Psychiatry, 22, 93–98. [CrossRef]

- Dugas, M. J., Freeston, M. H., & Ladouceur, R. (1997). Intolerance of uncertainty and problem orientation in worry. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 21, 593–606. [CrossRef]

- Dunson, D. B., Pillai, N., & Park, J. H. (2007). Bayesian density regression. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology, 69(2), 163–183. [CrossRef]

- Eisma, M. C., Boelen, P. A., Schut, H. A., & Stroebe, M. S. (2017). Does worry affect adjustment to bereavement? A longitudinal investigation. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 30(3), 243–252. [CrossRef]

- Extremera, N., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2006). Emotional intelligence as predictor of mental, social, and physical health in university students. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 9(1), 45–51.

- Fergus, T. A., Valentiner, D. P., McGrath, P. B., Gier-Lonsway, S., & Jencius, S. (2013). The cognitive attentional syndrome: Examining relations with mood and anxiety symptoms and distinctiveness from psychological inflexibility in a clinical sample. Psychiatry Research, 210(1), 215–219. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Berrocal, P., Alcaide, R., Extremera, N., & Pizzarro, D. (2006). The role of emotional intelligence in anxiety and depression among adolescents. Individual Differences Research, 4, 16–27.

- Fernández-Berrocal, P., Salovey, P., Vera, A., Extremera, N., & Ramos, N. (2005). Cultural influences on the relation between perceived emotional intelligence and depression. International Review of Social Psychology, 18(1), 91–107.

- Gelman, A., Goodrich, B., Gabry, J., & Vehtari, A. (2019). R-squared for Bayesian regression models. The American Statistician, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Gigantesco, A., Del Re, D., Cascavilla, I., Palumbo, G., De Mei, B., Cattaneo, C., Giovannelli, I., & Bella, A. (2015). A universal mental health promotion programme for young people in Italy. BioMed Research International, 2015, 345926. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, R., Widom, C. S., Browne, K., Fergusson, D., Webb, E., & Janson, S. (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet, 373(9657), 68–81.

- Girgus, J. S., & Yang, K. (2015). Gender and depression. Current Opinion in Psychology, 4, 53–60. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Baya, D., Mendoza, R., Paino, S., & de Matos, M. G. (2017). Perceived emotional intelligence as a predictor of depressive symptoms during mid-adolescence: A two-year longitudinal study on gender differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 303–312. [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H., Yiend, J., & Hirsch, C. R. (2017). Generalized Anxiety Disorder, worry and attention to threat: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 54, 107–122. [CrossRef]

- Goring, H. J., & Papageorgiou, C. (2008). Rumination and worry: Factor analysis of self-report measures in depressed participants. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 554–566. [CrossRef]

- Gravetter, F., & Wallnau, L. (2014). Essentials of Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Greenland, S. (2007). Bayesian perspectives for epidemiological research. II. Regression analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(1), 195–202.

- Gustavson, D. E., du Pont, A., Whisman, M. A., & Miyake, A. (2018). Evidence for transdiagnostic repetitive negative thinking and its association with rumination, worry, and depression and anxiety symptoms: A commonality analysis. Collabra: Psychology, 4(1), 13. [CrossRef]

- Heim, C., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2001). The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: Preclinical and clinical studies. Biological Psychiatry, 49(12), 1023–1039.

- Hong, R. Y. (2007). Worry and rumination: Differential associations with anxious and depressive symptoms and coping behavior. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(2), 277–290. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M. E., Alloy, L. B., & Cogswell, A. (2008). Repetitive thought in psychopathology: The relation of rumination and worry to depression and anxiety symptoms. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 22(3), 271–288. [CrossRef]

- Hwu, H. G., Chang, I. H., Yeh, E. K., Chang, C. J., & Yeh, L. L. (1996). Major depressive disorder in Taiwan defined by the Chinese diagnostic Interview Schedule. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 184(8), 497–502.

- Islam, M. R., & Adnan, R. (2017). Socio-demographic factors and their correlation with the severity of major depressive disorder: A population based study. World Journal of Neuroscience, 7(02), 193.

- Italian National Institute of Health. (2021). Sorveglianza PASSI. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/passi/dati/depressione.

- Italian National Institute of Health, Working Group "Consensus on Psychological Therapies for Anxiety and Depression". (2022, January). Consensus Conference on Psychological Therapies for Anxiety and Depression. Final Document. English Version. https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/0/Consensus_1_2022_EN.pdf.

- Jacobson, N. C., & Newman, M. G. (2017). Anxiety and depression as bidirectional risk factors in longitudinal studies: A meta-analysis of 66 longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 143(11), 1155–1200. [CrossRef]

- Jahangard, L., Haghighi, M., Bajoghli, H., Ahmadpanah, M., Ghaleiha, A., Zarrabian, M. K., & Brand, S. (2012). Training emotional intelligence improves both emotional intelligence and depressive symptoms in inpatients with borderline personality disorder and depression. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 16(3), 197–204. [CrossRef]

- JASP Team. (2023). JASP (Version 0.18.1) [Computer Software]. https://jasp-stats.org/download/.

- Karajan, T. F., & Yalçın, B. M. (2009). The effects of an emotional intelligence skills training program on the emotional intelligence levels of Turkish university students. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 36, 193–208.

- Karim, J., & Weisz, R. (2010). Discriminant and concurrent validity of trait and ability emotional intelligence measures: A cross-cultural study. International Journal of Arts and Sciences, 3(14), 428–449.

- Kendler, K. S., Gatz, M., Gardner, C. O., & Pedersen, N. L. (2006). A Swedish national twin study of lifetime major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(1), 109–114.

- Kim, H. Y. (2013). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 38(1), 52.

- Knight, R. G. (1984). Some general population norms for the short form Beck Depression Inventory. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40(3), 751–753.

- Korkmaz, S., Keleş, D. D., Kazgan, A., Baykara, S., Gürok, M. G., Demir, C. F., & Atmaca, M. (2020). Emotional intelligence and problem solving skills in individuals who attempted suicide. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 74, 120–123. [CrossRef]

- Kotsou, I., Mikolajczak, M., Heeren, A., Grégoire, J., & Leys, C. (2019). Improving emotional intelligence: A systematic review of existing work and future challenges. Emotion Review, 11(2), 151–165. [CrossRef]

- LeMoult, J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2019). Depression: A cognitive perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 69, 51–66. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., & Ren, S. (2018). Moderating effect of emotional intelligence on the relationship between rumination and anxiety. Current Psychology, 37, 272–279. [CrossRef]

- Llera, S. J., & Newman, M. G. (2010). Effects of worry on physiological and subjective reactivity to emotional stimuli in generalized anxiety disorder and nonanxious control participants. Emotion, 10(5), 640.

- Llera, S. J., & Newman, M. G. (2014). Rethinking the role of worry in generalized anxiety disorder: Evidence supporting a model of emotional contrast avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 45(3), 283–299.

- Lloyd, S. J., Malek-Ahmadi, M., Barclay, K., Fernandez, M. R., & Chartrand, M. S. (2012). Emotional intelligence (EI) as a predictor of depression status in older adults. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 55(3), 570–573. [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, C., Caselli, G., Rovetto, F., Rebecchi, D., Ruggiero, G. M., Sassaroli, S., & Spada, M. M. (2011). Temperament and parental styles as predictors of ruminative brooding and worry. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(2), 186–191. [CrossRef]

- Martins, A., Ramalho, N., & Morin, E. (2010). A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between Emotion Intelligence and health. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 554–564. [CrossRef]

- Maurer, D. M., Raymond, T. J., & Davis, B. N. (2018). Depression: Screening and diagnosis. American Family Physician, 98(8), 508–515.

- McEvoy, P. M., & Brans, S. (2013). Common versus unique variance across measures of worry and rumination: Predictive utility and mediational models for anxiety and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(1), 183–196. [CrossRef]

- Mestre, J. M., Núñez-Lozano, J. M., Gómez-Molinero, R., Zayas, A., & Guil, R. (2017). Emotion regulation ability and resilience in a sample of adolescents from a suburban area. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1980.

- Meyer, T. J., Miller, M. L., Metzger, R. L., & Borkovec, T. D. (1990). Development and validation of the Penn State worry questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(6), 487–495. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M. E., Borowski, S., & Zeman, J. L. (2020). Co-rumination moderates the relation between emotional competencies and depressive symptoms in adolescents: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48, 851–863. [CrossRef]

- Minka, T. (2000). Bayesian linear regression [Technical report]. MIT.

- Moeller, R. W., Seehuus, M., & Peisch, V. (2020). Emotional intelligence, belongingness, and mental health in college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 93. [CrossRef]

- Mourady, D., Richa, S., Karam, R., Papazian, T., Hajj Moussa, F., El Osta, N., Kesrouani, A., Jabbour, H., Hajj, A., & Rabbaa Khabbaz, L. (2017). Associations between quality of life, physical activity, worry, depression and insomnia: A cross-sectional designed study in healthy pregnant women. PLoS One, 12(5), e0178181. [CrossRef]

- Naragon-Gainey, K., McMahon, T. P., & Chacko, T. P. (2017). The structure of common emotion regulation strategies: A meta-analytic examination. Psychological Bulletin, 143(4), 384–427. [CrossRef]

- Newman, M. G., & Llera, S. J. (2011). A novel theory of experiential avoidance in generalized anxiety disorder: A review and synthesis of research supporting a contrast avoidance model of worry. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 371–382. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen-Prohl, J., Saliger, J., Güldenberg, V., Breier, G., & Karbe, H. (2013). Stress-stimulated volitional coping competencies and depression in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 74(3), 221–226. [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511. [CrossRef]

- Orth, U., Robins, R. W., & Roberts, B. W. (2008). Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 695–708. [CrossRef]

- Perini, S. J., Abbott, M. J., & Rapee, R. M. (2006). Perception of performance as a mediator in the relationship between social anxiety and negative post-event rumination. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 30, 645–659. [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2000). On the dimensional structure of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 29(2), 313–320.

- Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15(6), 425–448.

- Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2003). Trait emotional intelligence: Behavioural validation in two studies of emotion recognition and reactivity to mood induction. European Journal of Personality, 17(1), 39–57.

- Piccinelli, M., & Wilkinson, G. (2000). Gender differences in depression: Critical review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 177(6), 486–492.

- Picconi, L., Sergi, M. R., Cataldi, F., Balsamo, M., Tommasi, M., & Saggino, A. (2019). Strumenti di assessment per l'intelligenza emotiva in psicoterapia: Un'analisi critica. Psicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale, 25(2), 165–182. https://hdl.handle.net/11564/714263.

- Robichaud, M., & Dugas, M. J. (2005). Negative problem orientation (Part II): Construct validity and specificity to worry. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(3), 403–412. [CrossRef]

- Rood, L., Roelofs, J., Bögels, S. M., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schouten, E. (2009). The influence of emotion-focused rumination and distraction on depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(7), 607–616. [CrossRef]

- Ruan-Iu, L., Pendergast, L. L., Liao, P. C., Jones, P., von der Embse, N., Innamorati, M., & Balsamo, M. (2023). Measuring depression in young adults: Preliminary development of an English version of the Teate Depression Inventory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(15), 6470. [CrossRef]

- Saklofske, D. H., Austin, E. J., & Minski, P. S. (2003). Factor structure and validity of a trait emotional intelligence measure. Personality and Individual Differences, 34(4), 707–721. [CrossRef]

- Salk, R. H., Hyde, J. S., & Abramson, L. Y. (2017). Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychological Bulletin, 143(8), 783.

- Salguero, J. M., Extremera, N., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2012). Emotional intelligence and depression: The moderator role of gender. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(1), 29–32. [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9, 185–211. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Álvarez, N., Extremera, N., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2015). The relationship between emotional intelligence and subjective well-being in adolescents: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Adolescence, 93, 251–265. [CrossRef]

- Sarkisian, K. L., Van Hulle, C. A., & Hill Goldsmith, H. (2019). Brooding, inattention, and impulsivity as predictors of adolescent suicidal ideation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47, 333–344. [CrossRef]

- Schaakxs, R., Comijs, H. C., van der Mast, R. C., Schoevers, R. A., Beekman, A. T., & Penninx, B. W. (2017). Risk factors for depression: Differential across age? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(9), 966–977. [CrossRef]

- Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2011). Emotional intelligence mediates the relationship between mindfulness and subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(7), 1116–1119. [CrossRef]

- Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Hall, L. E., Haggerty, D. J., Cooper, J. T., Golden, C. J., & Dornheim, L. (1998). Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(2), 167–177. [CrossRef]

- Segerstrom, S. C., Tsao, J. C., Alden, L. E., & Craske, M. G. (2000). Worry and rumination: Repetitive thought as a concomitant and predictor of negative mood. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24, 671–688. [CrossRef]

- Sergi, M. R., Picconi, L., & Balsamo, M. (2012). Il ruolo dell'intelligenza emotiva nell'ansia e nella depressione: Uno studio preliminare. In M. Grieco & L. Tommasi (Eds.), Congresso nazionale delle sezioni, Chieti, 20–23 settembre 2012 (p. 155). Espress Edizioni srl.

- Sergi, M. R., Picconi, L., Fermani, A., Bongelli, R., Lezzi, S., Saggino, A., & Tommasi, M. (2023). The mediating role of positive and negative affect in the relationship between death anxiety and Italian students' perceptions of distance learning quality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Societies, 13(7), 163. [CrossRef]

- Sergi, M. R., Picconi, L., Tommasi, M., Saggino, A., Ebisch, S. J. H., & Spoto, A. (2021). The role of gender in the association among the emotional intelligence, anxiety and depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 747702. [CrossRef]

- Sharif, F., Rezaie, S., Keshavarzi, S., Mansoori, P., & Ghadakpoor, S. (2013). Teaching emotional intelligence to intensive care unit nurses and their general health: A randomized clinical trial. The International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 4(3), 141–148.

- Short, M. M., & Mazmanian, D. (2013). Perfectionism and negative repetitive thoughts: Examining a multiple mediator model in relation to mindfulness. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(6), 716–721. [CrossRef]

- Siegle, G. J., Moore, P. M., & Thase, M. E. (2004). Rumination: One construct, many features in healthy individuals, depressed individuals, and individuals with lupus. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28, 645–668. [CrossRef]

- Slaski, M., & Cartwright, S. (2003). Emotional intelligence training and its implications for stress, health and performance. Stress and Health, 19(4), 233–239. [CrossRef]

- Sorg, S., Vögele, C., Furka, N., & Meyer, A. H. (2012). Perseverative thinking in depression and anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 20. [CrossRef]

- Spinhoven, P., Drost, J., van Hemert, B., & Penninx, B. W. (2015). Common rather than unique aspects of repetitive negative thinking are related to depressive and anxiety disorders and symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 33, 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Stordal, E., Mykletun, A., & Dahl, A. A. (2003). The association between age and depression in the general population: A multivariate examination. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 107(2), 132–141.

- Teicher, M. H., Samson, J. A., Anderson, C. M., & Ohashi, K. (2016). The effects of childhood maltreatment on brain structure, function and connectivity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(10), 652–666.

- Thapar, A., Eyre, O., Patel, V., & Brent, D. (2022). Depression in young people. The Lancet, 400(10352), 617–631. [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Regional Health–Europe. (2022). Protecting the mental health of youth. The Lancet Regional Health-Europe, 12, 100306. [CrossRef]

- Vandekerckhove, J., Rouder, J. N., & Kruschke, J. K. (2018). Bayesian methods for advancing psychological science. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25, 1–4.

- Vickers, K. S., & Vogeltanz-Holm, N. D. (2003). The effects of rumination and distraction tasks on psychophysiological responses and mood in dysphoric and nondysphoric individuals. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 331–348. [CrossRef]

- Vîslă, A., Stadelmann, C., Watkins, E., Zinbarg, R. E., & Flückiger, C. (2022). The relation between worry and mental health in nonclinical population and individuals with anxiety and depressive disorders: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 46(3), 480–501.

- Vucenovic, D., Sipek, G., & Jelic, K. (2023). The role of emotional skills (competence) and coping strategies in adolescent depression. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(3), 540–552. [CrossRef]

- Walton, V. A., Romans-Clarkson, S. E., Mullen, P. E., & Herbison, G. P. (1990). The mental health of elderly women in the community. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 5(4), 257–263.

- Wapaño, M. R. (2021). Emotional intelligence and mental health among adolescents. International Journal of Innovation Management, 5, 467–481.

- Watkins, E., & Baracaia, S. (2001). Why do people ruminate in dysphoric moods? Personality and Individual Differences, 30(5), 723–734. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, E. R., & Moulds, M. L. (2009). Thought control strategies, thought suppression, and rumination in depression. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 2(3), 235–251. [CrossRef]

- Weiss Wiesel, T. R., Nelson, C. J., Tew, W. P., Hardt, M., Mohile, S. G., Owusu, C., Klepin H. D., Gross C. P., Gajra A., Lichtman S. M., Ramani R., Katheria V., Zavala L., Hurria A., & Cancer Aging Research Group (CARG). (2015). The relationship between age, anxiety, and depression in older adults with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 24(6), 712–717. [CrossRef]

- Wells, A. (1995). Meta-cognition and worry: A cognitive model of generalized anxiety disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(3), 301–320.

- World Health Organization. (2022, March 2). COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide. Wake-up call to all countries to step up mental health services and support. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide.

- Yalcin, B. M., Karahan, T. F., Ozcelik, M., & Igde, F. A. (2008). The effects of an emotional intelligence program on the quality of life and well-being of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Educator, 34(6), 1013–1024. [CrossRef]

- Zysberg, L., & Zisberg, A. (2022). Days of worry: Emotional intelligence and social support mediate worry in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(2), 268–277. [CrossRef]

| Non-clinical sample (N=806) | Mean |

SD |

Skewness | Kurtosis |

| Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Self | 35.403 | 4.544 | -0.510 | 0.516 |

| Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Other | 22.247 | 3.782 | -0.407 | 0.102 |

| Social Skills | 14.701 | 2.906 | -0.277 | -0.255 |

| Optimism/Mood Regulation | 21.201 | 2.601 | -0.767 | 0.594 |

| Affective symptoms | 3.319 | 2.917 | 0.883 | 0.289 |

| Somatic symptoms | 4.536 | 3.197 | 0.532 | -0.060 |

| Worry | 47.744 | 10.585 | -0.056 | -0.087 |

| Subclinical sample with elevated depressive symptoms (N=118) | ||||

| Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Self | 33.166 | 5.430 | -0.450 | 0.323 |

| Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Other | 21.898 | 4.877 | -0.574 | -0.319 |

| Social Skills | 12.728 | 3.204 | 0.141 | -0.185 |

| Optimism/Mood Regulation | 20.010 | 3.296 | -1.002 | 1.420 |

| Affective symptoms | 13.129 | 4.173 | 0.707 | 0.602 |

| Somatic symptoms | 13.320 | 3.395 | -0.028 | -0.104 |

| Worry | 59.334 | 10.660 | -0.379 | -0.259 |

| Non-clinical sample (N=806) | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. |

| 1. Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Self |

|||||||

| 2. Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Others |

.307*** | ||||||

| 3. Social Skills | .325*** | .338*** | |||||

| 4. Optimism/Mood Regulation | .506*** | .373*** | .269*** | ||||

| 5. Affettive symptoms | -.184*** | -.015 | -.127 *** | -.034 | |||

| 6. Somatic symptoms | -.081* | -.065 | -.154*** | -.002 | .456*** | ||

| 7. Worry | -.048 | -.042 | -.139*** | .110** | .363*** | .288*** | |

| Subclinical sample with elevated depressive symptoms (N=118) | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. |

| 1. Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self |

|||||||

| 2. Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Others |

.369*** | ||||||

| 3. Social Skills | .447*** | .365*** | |||||

| 4. Optimism/Mood Regulation | .513*** | .518*** | .314*** | ||||

| 5. Affective symptoms | -.117 | .151 | .001 | -.016 | |||

| 6. Somatic symptoms | -.202* | -.011 | -.150 | -.172 | .030 | ||

| 7. Worry | -.074 | .211* | -.088 | .083 | .189* | .201* |

| Models in the female sample | p(M) | p(M|) | BFMj | BF01 | R² | ||||||

| Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self + Worry | .016 | .389 | 40.091 | 2.273×10-15 | .140 | ||||||

| Models in the male sample | p(M) | p(M|) | BFMj | BF01 | R² | ||||||

| Worry + Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self | .016 | 0.389 | 40.091 | 2.273×10-15 | .140 | ||||||

| 95% Credible Interval | |||||||||||||||||||

| Coefficient in the female sample | p(incl) | P(excl) | p(incl|data) | BFinclusion | M | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 3.638 | 0.124 | 3.394 | 3.875 | |||||||||||

| Worry | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.997 | 361.156 | -0.119 | 0.030 | -0.179 | -0.062 | |||||||||||

| Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.283 | 0.395 | 0.015 | 0.030 | -6.906×10-4 | 0.099 | |||||||||||

| Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Others | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.161 | 0.192 | -0.005 | 0.022 | -0.070 | 0.025 | |||||||||||

| Social Skills | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.131 | 0.150 | 0.001 | 0.023 | -0.042 | 0.069 | |||||||||||

| Optimism/Mood Regulation | 0.500 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 2.744×10+11 | 0.095 | 0.012 | 0.070 | 0.118 | |||||||||||

| Age | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.284 | 0.397 | -0.005 | 0.010 | -0.032 | 1.107×10-4 | |||||||||||

| 95% Credible Interval | |||||||||||||||||||

| Coefficient in the male sample | p(incl) | p(excl) | p(incl|data) | BFinclusion | M | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 3.638 | 0.124 | 3.388 | 3.856 | |||||||||||

| Worry | 0.500 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 2.744×10+11 | 0.095 | 0.012 | 0.071 | 0.117 | |||||||||||

| Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.997 | 361.156 | -0.119 | 0.030 | -0.176 | -0.065 | |||||||||||

| Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Others | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.283 | 0.395 | 0.015 | 0.030 | -0.002 | 0.088 | |||||||||||

| Social Skills | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.161 | 0.192 | -0.005 | 0.022 | -0.070 | 0.016 | |||||||||||

| Optimism/Mood Regulation | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.131 | 0.150 | 0.001 | 0.023 | -0.044 | 0.068 | |||||||||||

| Age | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.284 | 0.397 | -0.005 | 0.010 | -0.030 | 0.000 | |||||||||||

| Models in the female sample | p(M) | p(M |) | BFMj | BF01 | R² | ||||||

| Worry | 0.016 | 0.237 | 19.529 | <.001 | 0.076 | ||||||

| Models in the male sample | p(M) | p(M |) | BFMj | BF01 | R² | ||||||

| Worry | 0.016 | 0.237 | 19.529 | 2.050×10-8 | 0.076 | ||||||

| 95% Credible Interval | |||||||||||||||||||

| Coefficient in the female sample | p(incl) | P(excl) | p(incl|data) | BFinclusion | M | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 4.654 | 0.133 | 4.404 | 4.924 | |||||||||||

| Worry | 0.500 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 2.309×10+7 | 0.082 | 0.013 | 0.057 | 0.108 | |||||||||||

| Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.202 | 0.253 | -0.007 | 0.020 | -0.076 | 0.006 | |||||||||||

| Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Others | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.271 | 0.372 | -0.014 | 0.031 | -0.103 | 0.001 | |||||||||||

| Social Skills | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.431 | 0.758 | -0.037 | 0.053 | -0.155 | 0.000 | |||||||||||

| Optimism/Mood Regulation | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.153 | 0.181 | 0.005 | 0.028 | -0.033 | 0.085 | |||||||||||

| Age | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.156 | 0.185 | 0.001 | 0.006 | -0.009 | 0.020 | |||||||||||

| 95% Credible Interval | |||||||||||||||||||

| Coefficient in the male sample | p(incl) | p(excl) | p(incl|data) | BFinclusion | M | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 4.654 | 0.133 | 4.388 | 4.912 | |||||||||||

| Worry | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.202 | 0.253 | -0.007 | 0.020 | -0.068 | 0.011 | |||||||||||

| Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.271 | 0.372 | -0.014 | 0.031 | -0.104 | 0.002 | |||||||||||

| Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Others | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.431 | 0.758 | -0.037 | 0.053 | -0.146 | 4.798×10-4 | |||||||||||

| Social Skills | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.153 | 0.181 | 0.005 | 0.028 | -0.006 | 0.115 | |||||||||||

| Optimism/Mood Regulation | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.156 | 0.185 | 0.001 | 0.006 | -0.007 | 0.019 | |||||||||||

| Age | 0.500 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 2.309×10+7 | 0.082 | 0.013 | 0.056 | 0.108 | |||||||||||

| Models in the female sample | p(M) | p(M|) | BFMj | BF01 | R² | ||||||

| Worry | 0.016 | 0.060 | 4.041 | 1.048 | 0.030 | ||||||

| Models in the male sample | p(M) | p(M|) | BFMj | BF01 | R² | ||||||

| Worry | 0.016 | 0.060 | 4.041 | 1.048 | 0.030 | ||||||

| 95% Credible Interval | |||||||||||||||||||

| Coefficient in the female sample | p(incl) | P(excl) | p(incl|data) | BFinclusion | M | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 13.219 | 0.386 | 12.396 | 13.918 | |||||||||||

| Worry | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.519 | 1.081 | 0.028 | 0.037 | -0.007 | 0.109 | |||||||||||

| Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.535 | 1.151 | -0.064 | 0.081 | -0.246 | 0.001 | |||||||||||

| Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Others | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.503 | 1.011 | 0.065 | 0.089 | -0.026 | 0.259 | |||||||||||

| Social Skills | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.260 | 0.352 | -0.002 | 0.067 | -0.194 | 0.147 | |||||||||||

| Optimism/Mood Regulation | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.279 | 0.386 | -0.014 | 0.078 | -0.238 | 0.149 | |||||||||||

| Age | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.374 | 0.598 | 0.015 | 0.030 | -0.013 | 0.093 | |||||||||||

| 95% Credible Interval | |||||||||||||||||||

| Coefficient in the male sample | p(incl) | p(excl) | p(incl|data) | BFinclusion | M | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 13.219 | 0.386 | 12.476 | 13.958 | |||||||||||

| Worry | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.535 | 1.151 | -0.064 | 0.081 | -0.248 | 0.016 | |||||||||||

| Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.503 | 1.011 | 0.065 | 0.089 | -0.015 | 0.256 | |||||||||||

| Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Others | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.260 | 0.352 | -0.002 | 0.067 | -0.205 | 0.161 | |||||||||||

| Social Skills | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.279 | 0.386 | -0.014 | 0.078 | -0.306 | 0.115 | |||||||||||

| Optimism/Mood Regulation | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.519 | 1.081 | 0.028 | 0.037 | -0.004 | 0.117 | |||||||||||

| Age | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.374 | 0.598 | 0.015 | 0.030 | -0.018 | 0.093 | |||||||||||

| Models in the female sample | p(M) | p(M|) | BFMj | BF01 | R² | ||||||

| Worry +Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self + Age | 0.016 | 0.103 | 7.264 | 0.064 | 0.128 | ||||||

| Models in the male sample | p(M) | p(M|) | BFMj | BF01 | R² | ||||||

| Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self+ Worry + Age | 0.016 | 0.103 | 7.264 | 0.064 | 0.128 | ||||||

| 95% Credible Interval | |||||||||||||||||||

| Coefficient in the female sample | p(incl) | P(excl) | p(incl|data) | BFinclusion | M | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 13.363 | 0.307 | 12.731 | 13.906 | |||||||||||

| Worry | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.724 | 2.628 | 0.041 | 0.035 | 0.000 | 0.103 | |||||||||||

| Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.614 | 1.588 | -0.067 | 0.073 | -0.213 | 0.009 | |||||||||||

| Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Others | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.292 | 0.412 | 0.012 | 0.044 | -0.048 | 0.158 | |||||||||||

| Social Skills | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.422 | 0.731 | -0.054 | 0.094 | -0.302 | 0.023 | |||||||||||

| Optimism/Mood Regulation | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.445 | 0.803 | -0.062 | 0.102 | -0.308 | 0.038 | |||||||||||

| Age | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.733 | 2.741 | 0.046 | 0.038 | -0.002 | 0.114 | |||||||||||

| 95% Credible Interval | |||||||||||||||||||

| Coefficient in the male sample | p(incl) | p(excl) | p(incl|data) | BFinclusion | M | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 13.363 | 0.307 | 12.699 | 13.930 | |||||||||||

| Worry | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.614 | 1.588 | -0.067 | 0.073 | -0.213 | 0.000 | |||||||||||

| Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.292 | 0.412 | 0.012 | 0.044 | -0.056 | 0.141 | |||||||||||

| Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Others | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.422 | 0.731 | -0.054 | 0.094 | -0.288 | 0.027 | |||||||||||

| Social Skills | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.445 | 0.803 | -0.062 | 0.102 | -0.341 | 0.036 | |||||||||||

| Optimism/Mood Regulation | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.724 | 2.628 | 0.041 | 0.035 | -9.757×10-4 | 0.103 | |||||||||||

| Age | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.733 | 2.741 | 0.046 | 0.038 | -2.492×10-4 | 0.116 | |||||||||||

| Variable | Welch’s F | df₁ | df₂ | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expression and Evaluation of Emotion to Self |

18.169 | 1 | 141.996 | < .001 |

| Evaluation and Expression of Emotion to Others |

0.556 | 1 | 138.354 | .457 |

| Social Skills | 39.935 | 1 | 146.583 | < .001 |

| Optimism / Mood Regulation | 14.125 | 1 | 139.133 | < .001 |

| BDI Affective | 898.613 | 1 | 139.144 | < .001 |

| BDI Somatic | 573.732 | 1 | 152.655 | < .001 |

| Worry | 121.900 | 1 | 152.755 | < .001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).