1. Introduction

Single-celled organisms are able to actively participate in changes in environmental chemistry. They mediate oxidation and reduction reactions occurring in both aquatic and terrestrial environments (e.g., [

1,

2]). Such processes also occurred in the geological past and could be recorded in rocks, which we can read by deciphering fossilization processes (e.g., [

3,

4]). The fossilization of single-celled organisms is most likely if they precipitated extracellular inorganic coatings [

5,

6]. Such structures are usually left as the only remnants after decomposition of bacterial cellular matter, providing valuable information on microbial life in ancient environments (e.g., [

7]). The more resistant to later re-mobilization are metallic bacterial coatings such as those created by iron related bacteria (IRB) [

8,

9]. Such type of bacteria are able to catalyse the oxidation of Fe (II) [

10,

11] and accumulate the (oxyhydr)oxides, either outside the cells or in the surrounding extracellular polymeric matrices (e.g., [

12]).

IRB are well known from modern environments as well as from the fossil record. The earliest fossilized bacterial remnants, morphologically comparable with the modern IRB have been recognized so far from the well-known Precambrian Gunflint cherts [

13,

14], as well as in many Precambrian sediment successions. They also contributed significantly to the bedded iron formations (BIFs) (e.g., [

3,

13,

15]).

The bacterial iron-encrustations have been described also from various sedimentary environments in many Phanerozoic successions, both freshwater (e.g., [

16]) and marine (e.g., [

17,

18,

19]). They were recognized in fossil record from high-energy, shallow (e.g., [

20]) to calm, deep water settings [

7], where they can formed Fe-oolite sands [

21,

22], bacterial mats [

17], stromatolites [

23] or incrustations binding mud mounds [

24]. Especially in marine environments, bacterially mediated amorphous iron oxyhydroxides combined with manganese oxyhydroxides and silica are commonly found in areas of mid-ocean and back-arc volcanic activity, covering vast areas of the ocean floor [

25], also associated with hydrothermal fluids activity.

In the present study, we report morphological and chemical evidences for the presence of bacteria-like structures belonging to IRB group in the Lower Carboniferous limestones along the Upper Silesian Block (

Figure 1a,b) being the northern part of the larger unit known as the Brunovistulian Terrane (e.g., [

26]), and we try to indicate their origin and time of appearance in these rocks. A characteristic feature of the limestones consisting the IRB-like structures is their red colour, which does not occur in underlying carbonate successions [more than 1 km thick] which was formed on the epicontinental shelf stretching from the Western Europe to the Ukraine [

27]. Previous publications suggested the sedimentary origin of the red colouration of these limestones, related to the admixture of hematite which would be redistributed from the terrestrial environment [

28]. Here, we test another hypothesis, which connects the occurrence of IRB-like structures with the activity of hydrothermal waters. In the study area, they could have occurred during two different geological periods. The first one could be related to the late Carboniferous and early Permian post-orogenic granitoid plutonism and bimodal volcanism (e.g., [

29,

30]). And the second one – to the Late Triassic sulphide mineralization [mainly of Zn-Pb] of unknown fluid origin [

31].

2. Geological Setting

The IRB-like remnants have been found in the uppermost part of the upper Devonian–lower Carboniferous succession of the ancient carbonate platform in the Moravo-Silesian Basin that surrounded the Upper Silesian Block, an eastern margin of the Brunovistulicum microcontinent (e.g., [

32,

33,

34]). This carbonate body developed approximately three hundred kilometers on a passive continental margin facing a deep-water basin of the Rhenohercynian system [

35,

36,

37]. Due to sea-level rise and tectonic extension, successive drowning of this platform occurred [

37,

38] being partly associated with its disintegration and the development of intra-platform troughs [

39,

40,

41]. The closure of the Rhenohercynian ocean resulted in subsequent continental collision between Lugodanubian and subducting Brunovistulian terrane [

42] which ultimately amalgamated the Upper Silesian Block with the Bohemian Massif [

26].

During Late Carboniferous–Early Permian post-orogenic stages, granitoid plutonism and bimodal volcanism took place in both foreland and the internal parts of the Variscan orogen including the recent southern Poland [

29,

43]. Their numerous occurrences (e.g., [

30,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]) are associated with the Kraków–Lubliniec Fault Zone which divides the Upper Silesian Block from the Małopolska Block (

Figure 1b).

The Variscan basement containing the Devonian and Carboniferous sediments is covered discordantly by the succession of Permian–Mesozoic carbonate and siliciclastic sediments of the Central European Basin, dominated by the Triassic strata (

Figure 1c). All of them dips toward the northeast reflecting the vertical crustal mobility of this region [

51]. The Middle Triassic limestones and dolomites (Muschelkalk) comprise the Zn-Pb deposits, locally as resources of economic value (e.g., [

31,

52]). However, this Zn-Pb mineralization is hosted also by older (Devonian–Permian) and younger (Jurassic) rocks [

53,

54].

The studied Upper Devonian to Early Carboniferous limestones of the shallow-water platform (bioclastic wackstones with brachiopods) are recently outcropped in the southernmost part of the Kraków–Częstochowa Upland (Southern Poland), 25 km west of Kraków (

Figure 1c). In this area, the Middle Devonian–Early Carboniferous carbonates (limestones and dolomites) are cut by several gorges containing among others, the Racławka and Czernka valleys. Our microfacial and geochemical studies are based on samples from three sections located in these valleys. The section from the Racławka valley (DR3;

Figure 2) corresponds to the Lower Tournaisian, whereas the two sections from the Czernka valley (DC1, DC2;

Figure 2) belong to the middle Visean, based on analyses of foraminiferal assemblages [

55].

4. Results

4.1. Microstructure of Limestones with Ferruginous Pigments

The analysis of foraminiferal assemblages and microfacies showed that all samples studied are biogenic limestones that were formed in a shallow marine environment [

55]. They contain different percentages of calcareous bioclasts which are mainly benthic foraminifers, mostly belonging to the fusulinids (

Figure 4a,b). The remaining bioclasts are fragments of skeletal plates of echinoderms (

Figure 4a). Other biotic particles are very rare. A characteristic feature of these limestones is sparite binder, which crystals vary in size (

Figure 4e). The smallest calcite crystals (3–5 µm) occur in the recrystallized walls of foraminifera, and the largest (5–10 µm and larger) – infill originally empty chambers or pores in skeletons, as well as they occur in the space surrounding bioclasts.

SEM-EDS images of selected surfaces of thin sections of rocks, which were characterized by the presence of redness, show their structural and chemical differences. Larger, light grey and dark grey areas seen in the BSE image (sometimes white-glowing points) correspond to the shell walls of foraminifers and other bioclasts which is confirmed by TLM images (

Figure 4b,c). Among them, white dots and streaks occur mainly around bioclasts or sparite crystals. In turn, dark grey areas are the filling of originally empty spaces in foraminiferal chambers and spaces between bioclasts. Chemical SEM-EDS microanalysis (

Figure 5) indicates that light grey areas consist mainly of calcite, which is the main component of bioclasts. White streaks and glowing points contain an increased content of Fe oxides. In some places, these white peaks occur in microcrystalline quartz (

Figure 6). On the other hand, dark gray areas contain Mg oxide and therefore may be partially composed of dolomite crystals (

Figure 6).

Detailed microscopic analysis of all thin sections of the rocks studied show that only red Visean limestones (section DC1) possess irregular rust to brown areas that could have been caused by iron-related bacterial activity (

Figure 4e,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Microfacies analysis (TLM) shows that these pigmented areas contain iron oxides and oxyhydroxides, accompanied by individual iron-bearing microcrystals and/or aggregates. These ferrous discolourations can occupy areas of up to 40% of the microscopic view. They occur in various positions in relation to the sparite cement crystals. They are most common between crystals, on the edges and walls of crystals forming a characteristic network (

Figure 7). This is especially the case when the calcite crystals are small. Larger crystals contain individual oval structures of size 1–2 µm enclosed within them (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). Rust-coloured and brownish structures may form thin streaks between crystals or thicker coatings with raised, oval shapes and blurred edges. Whereas when these structures are thicker, they become dark brown to black inside and have oval to convex shapes that can be single or clustered in larger black areas. In most cases, these areas were the site of growth of Fe-bearing crystals.

4.2. Mineralogy of Ferruginous Discolourations in Limestones

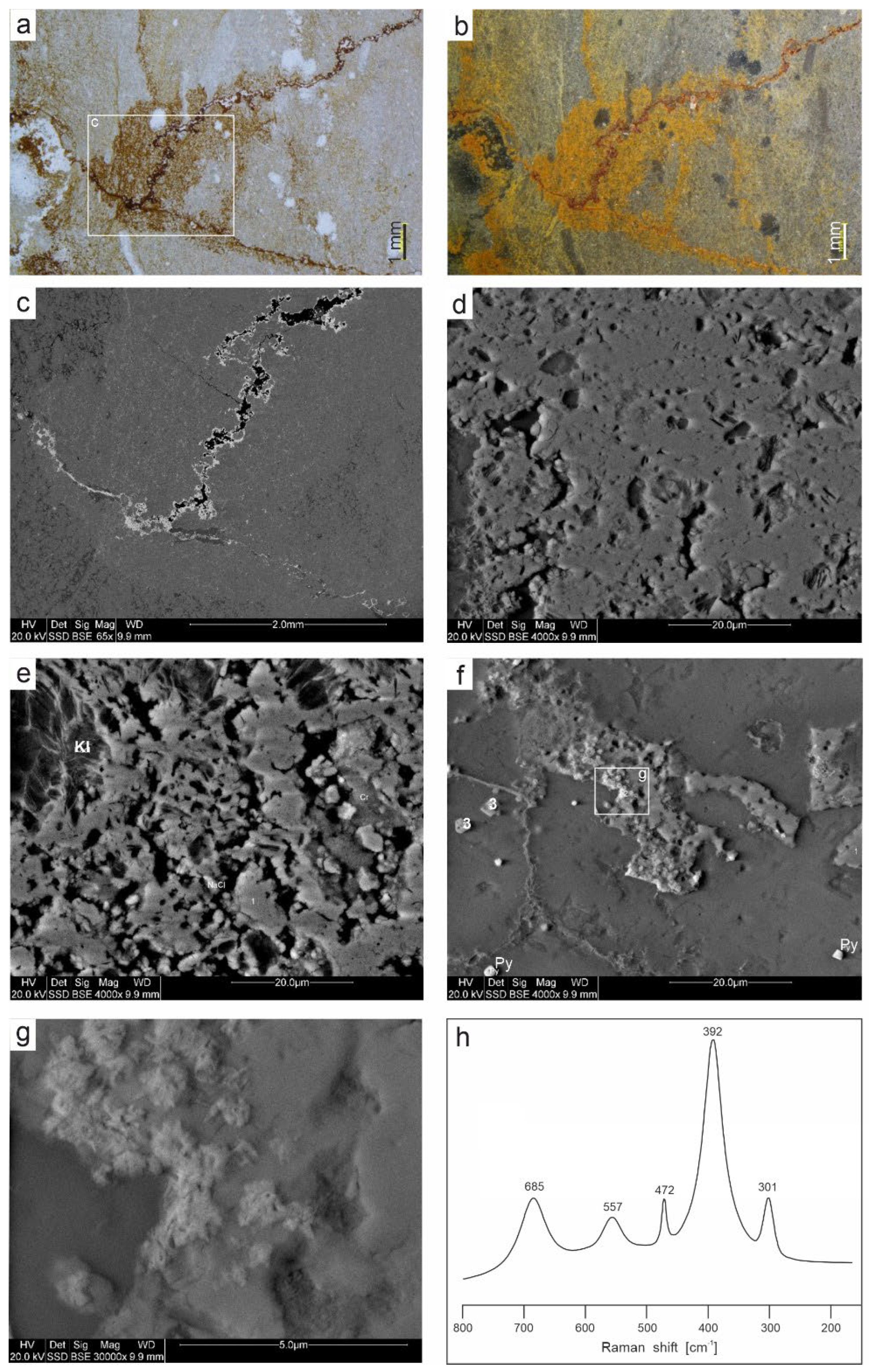

The microscopic images (TLM) shows that the source of reddish and yellowish discolouration of the studied rocks, which gives the overall macroscopic colour and creates rusty coatings around fossils and bioclasts are numerous veins filled with several generations of minerals (

Figure 10a,b).

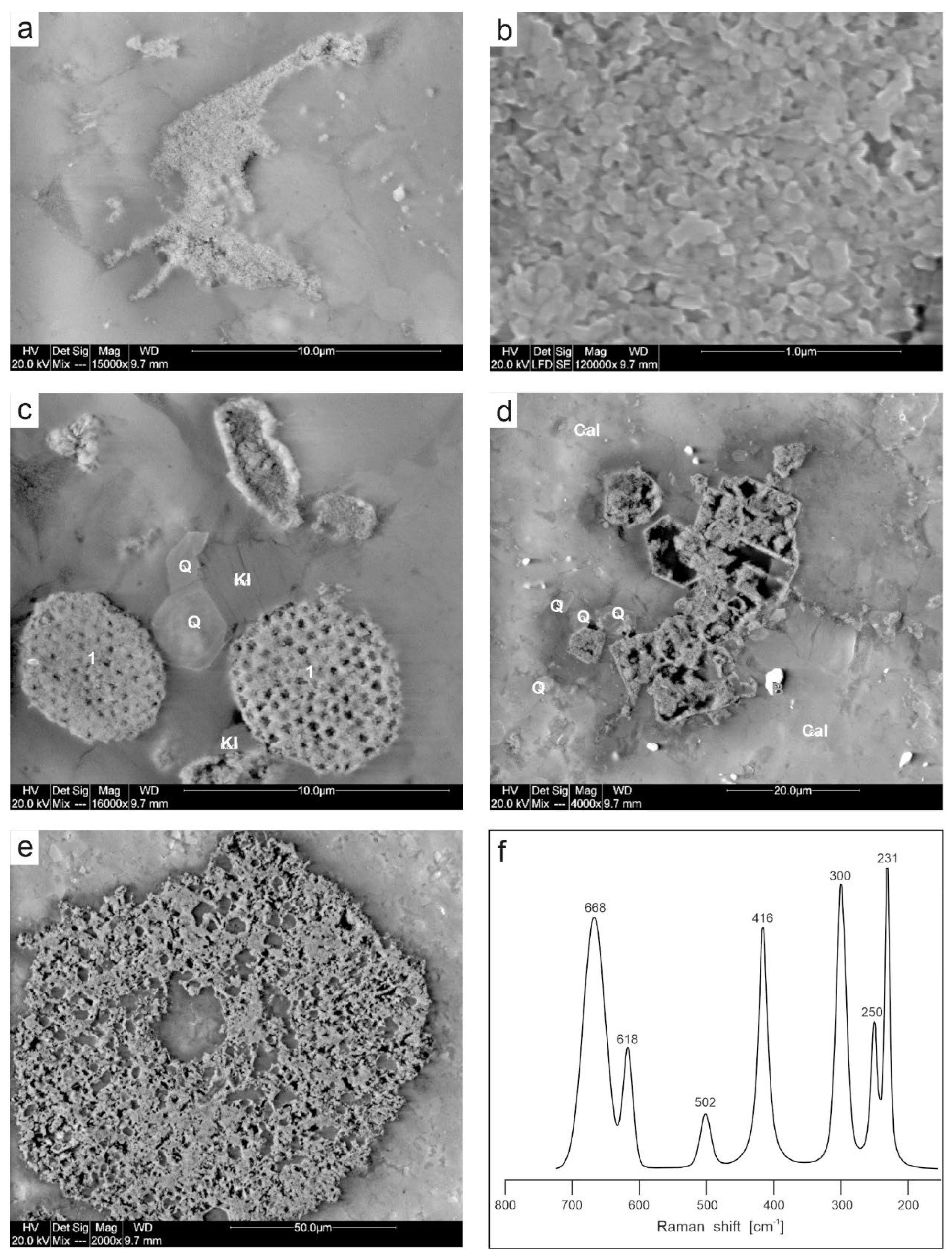

SEM observations and SEM-EDS analyses supported by Raman microspectroscopy indicate that the Fe oxyhydroxides and oxides present in the studied samples are goethite (α-FeOOH) and hematite (α-Fe

2O

3), both of which form very diverse morphological forms (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). These are very finely dispersed crystals and indentations, several µm in size, which are responsible for the majority of the colour of the entire rock. Furthermore, pore and vein fillings are common, as are pseudomorphs after pyrite (e.g.,

Figure 11d) and rounded porous aggregates, likely of bacterial origin (

Figure 11c). The collected Raman spectra indicate that goethite and hematite do not occur together; individual samples contain only one or the other mineral. Goethite is the dominant iron carrier in samples DC1.1 and DC1.2, which are characterized by a yellowish colour. Here, small (max 2–3 µm) crystallites (most often filling pores) can be encountered, with the acicular shape characteristic of this oxyhydroxide. In contrast, in specimens with a dominant reddish colour (samples DC1.3, DC1.4.1, DC1.4.2, DC1.5), the colouring agent is hematite, in places forming quasi-spherical or plate-like crystallites. Variation in colour within a single sample (e.g., DC1.4.2) appears to be unrelated to mineralogical diversity (in this particular case, the only Fe form detected is hematite), but rather to the degree of mineral accumulation in different locations. There is also no evidence of significant differences in chemical composition between zones of different colour within a single sample. However, subtle differences in the composition of iron compounds between samples are noticeable. Some samples do not contain EDS-detectable admixtures of other transition metals (as in sample DC1.3) but do contain admixtures of Zn (samples DC1.1, DC1.2, DC1.5), Ti (samples DC1.1, DC1.2), and Mn (in some locations in samples DC1.4.1 and DC1.5). In sample DC1.2, Mn oxides with a significant Pb content are occasionally found alongside goethite. The chemistry and morphology of the fine crystallites suggest that it is coronadite Pb

1-1.4(Mn

4+,Mn

3+)

8O

16 (

Figure 10f,g).

Other non-carbonate components of the limestones include Fe sulfides (pyrite), quartz, and kaolinite (

Figure 10e and

Figure 11c). Barite (

Figure 11d), Ti oxides (rutile), and fluorapatite were also encountered. Pyrite most often occurs as scattered single euhedral or subhedral crystals, with sizes up to several µm. Framboidal clusters (up to 10 µm in diameter) composed of crystals <1 µm in size can also be found (sample DC1.1). Pseudomorphs of Fe oxides after FeS

2 are common alongside fresh, unoxidized pyrite crystals. Quartz and kaolinite typically occur in zones enriched in iron oxides and oxyhydroxides, as evidenced by elemental maps indicating correlations in Fe, Si, and Al concentrations. Both silicates are often euhedral, and euhedral quartzes with visible crystal growth zones are also found.

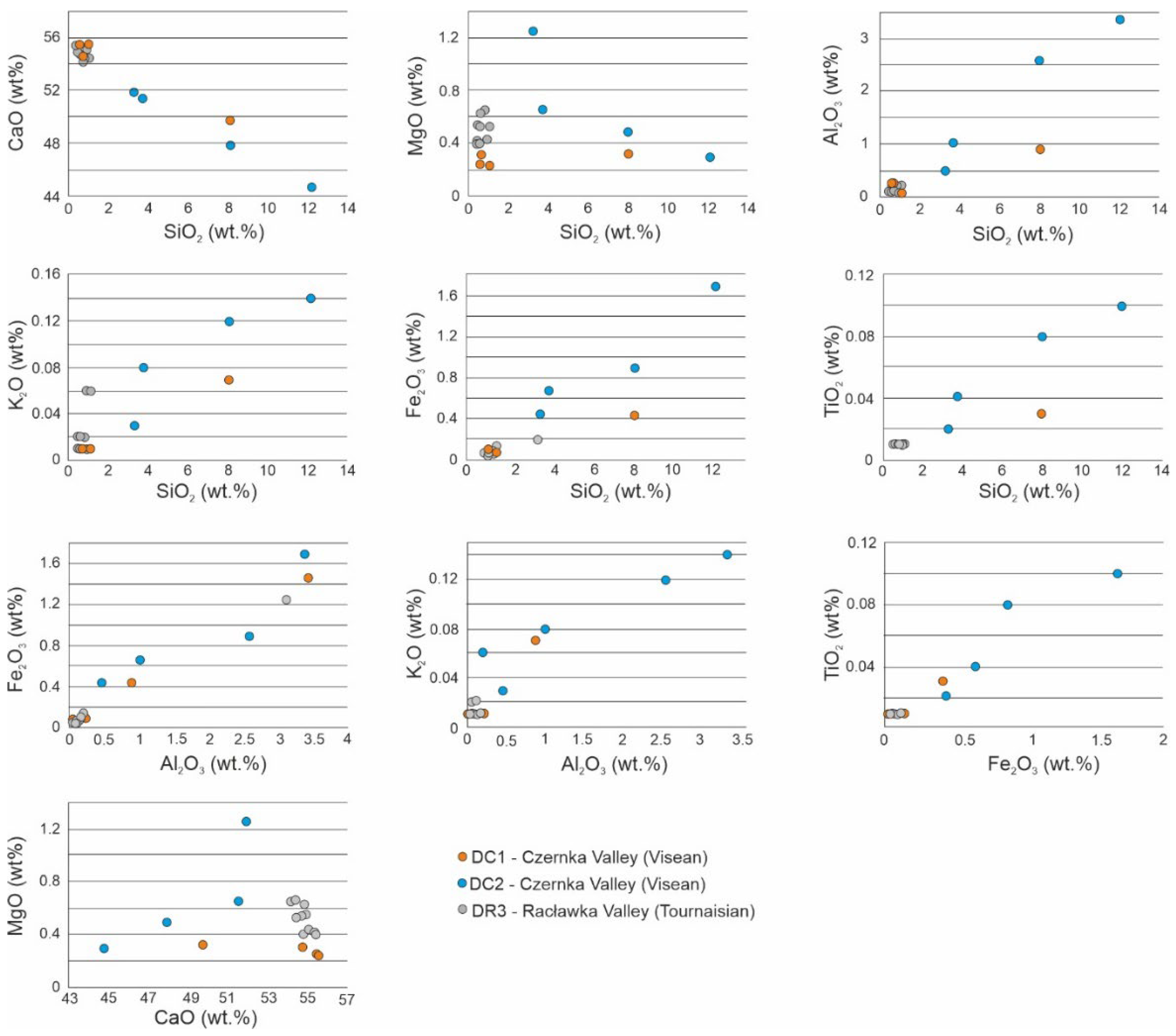

4.3. Geochemistry of Major Oxides and Trace Elements

The rocks studied show strong differences in the content of major elements (

Table 1 and

Table 2). In the Visean red limestones (DC1 section), the concentration of CaO is markedly lower (44.70–51.88 wt%) being in contrast to the sum of other components which are not geochemically related to limestones, i.e., SiO

2, MgO, Fe

2O

3, Al

2O

3, K

2O, MnO, TiO

2, P

2O

5, Na

2O. The content of SiO

2 is high (3.28–12.14 wt%) as well as the content of Al

2O

3 (0.46–3.34 wt%) and Fe

2O

3 (0.44–1.69 wt%), while the amount of MgO is relatively small (1.26–3.28 wt.%). The contents of other elements are also clearly higher than the average contents for marine limestones [

57].

The samples from the second section of the Visean rocks (DC2)are characterized by the higher amount of CaO (49.72–55.51wt%) and a lower the sum of other components (1.19–9.83 wt%). The concentration of SiO2 is lower (0.59–9.83 wt%), similarly as the content of Al2O3 (0.02–0.88 wt%), Fe2O3 (0.07–0.33 wt%) and MgO (0.24–0.33 wt%). The abundance of other elements is lower (K2O < 0.07 wt%; TiO2 < 0.03 wt%; MnO < 0.03 wt%).

Quite different composition of main oxides characterize the Tournaisian limestones (DR-3 section). The high content of CaO (54.16–55.34 wt%) and a low amounts of SiO2 (0.41–1.06 wt%), Al2O3 (0.05–0.19 wt%) and Fe2O3 (0.04–0.13 wt%) are typical values of limestones. The only amount of MgO (0.40–0.66 wt%) is clearly higher in this succession. The abundances of other oxides like TiO2, MnO, P2O5, and Na2O does not exceed 0.01wt%. Only the K2O content is slightly higher (up to 0.06 wt%).

4.4. Correlation Between Main Elements and SEM-EDS Mapping

The Pearson coefficient values, calculated for individual pairs of oxides content in all samples from the DC1 section (

Table 3) show strong linear correlation between SiO

2 and Al

2O

3, Fe

2O

3, K

2O, TiO

2, P

2O

5 and MnO. Moreover, there is a strong negative correlation between CaO and Fe

2O

3, SiO

2, Al

2O

3, K

2O, TiO

2, P

2O

5 and MnO. The significant is also negligible correlation between MgO and all above mentioned oxides, which is characteristic for all samples investigated. The same trend is distinctly visible for samples of all sections investigated (DC1, DC2, DR3) (

Figure 12), although individual profiles were affected to a different extent by the impact of hydrothermal solutions, which was reflected in the different contents of individual elements.

The above tendency visible in the analytical results is also clearly depicted in SEM-EDS mapping (

Figure 6). The microanalysis of Si, Fe, Ca, Mg, Al and K clearly shows that the micro-area of increased SiO

2 and Fe oxides and oxyhydroxides contents overlap. This dependence is clearly visible in the images from rocks in profile DC1, where the weight amount of both oxide groups is relatively high. The same area also coincides with the fields of Al and K oxides in the same samples.

The area of co-occurrence of SiO2, Fe oxides and oxyhydroxides and (Al, K) elements is generally separated from the area with increased CaO and MgO values, which is associated primarily with coarse-crystalline cement filling the original porosity and generally does not contain Fe-bearing browning.

4.5. Trace Elements

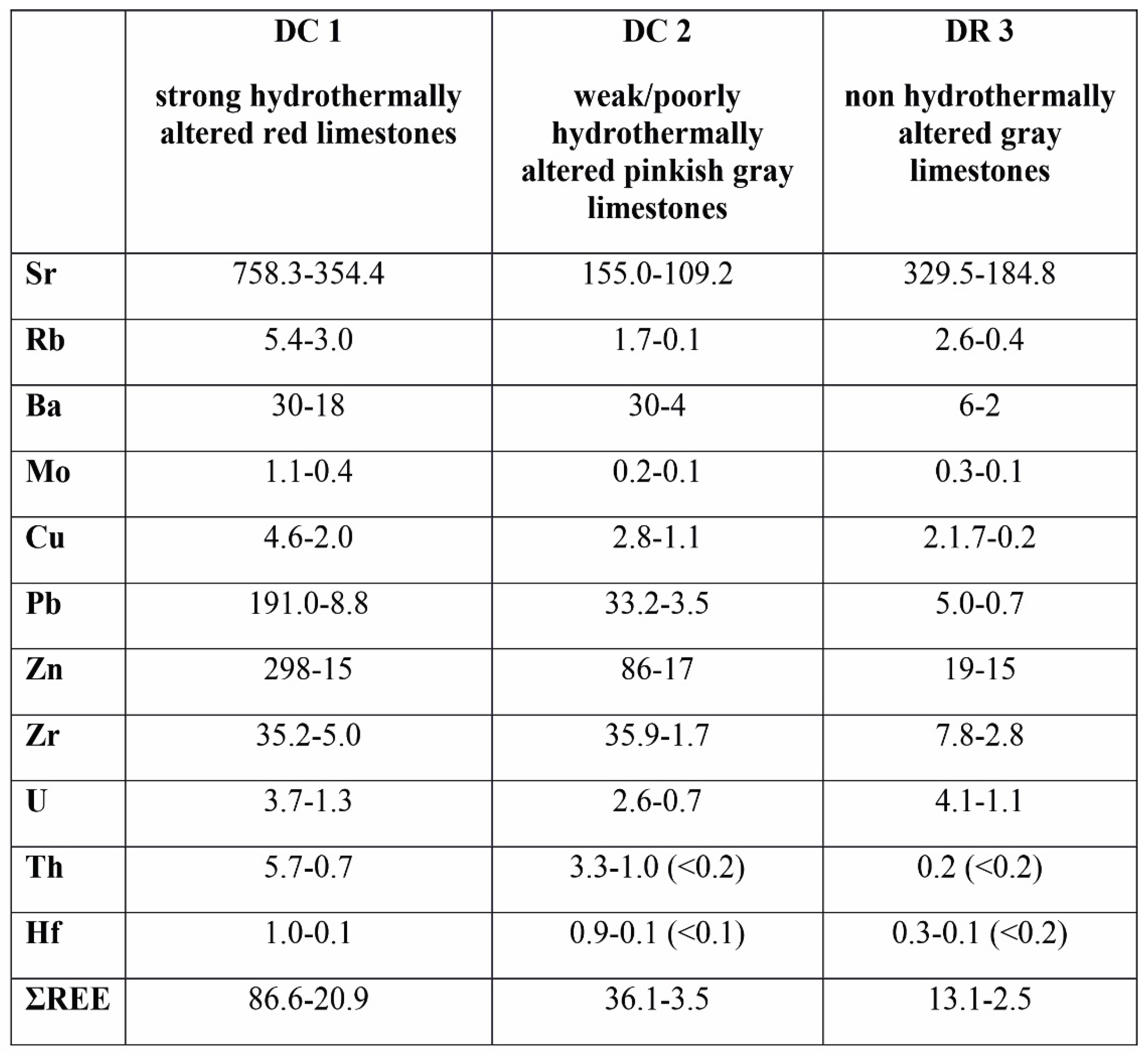

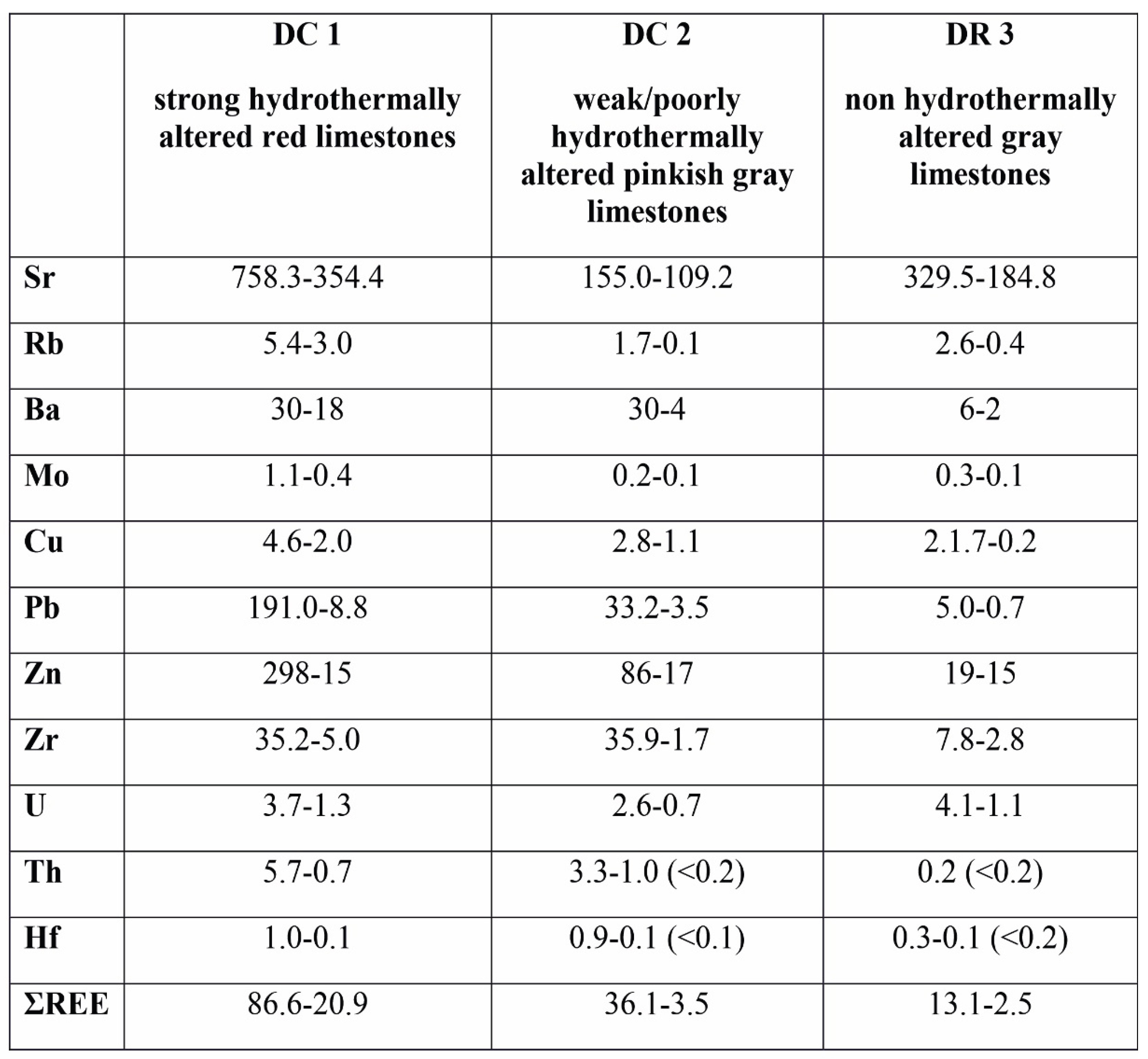

The composition of trace elements in these limestones display similar differences in the sections studied (

Table 4 and

Table 5). The red limestones from the Czernka Valley (DC1, DC2) are particularly distinctive in this respect. The DC1 samples are characterized by enhanced content of several elements in relation to samples from the Racławka Valley (DR3). This applies to the following elements: Zn (up to 298 ppm), Pb (up to 191 ppm), Sr (up to 758 ppm), V (up to 36 ppm), Ba (up to 30 ppm), As (up to 15.1 ppm), Th (up to 5.7 ppm), Nb (up to 4,5 ppm), U (up to 3.7 ppm), Zr (up to 35.2 ppm), Mo (up. To 1.4 ppm), Hf (up to 1 ppm), Sb (up to 1.0 ppm), Ga (up to 1.3 ppm), and Hg (0.4–0.7 ppm).

In the second section of the Visean limestones (DC2), the increased values refer only to one sample (DC2.08) and to some trace elements, i.e., Zn (86 ppm), Ba (30 ppm), Zr (35.9 ppm), Pb (33.2 ppm), Th (3.3. ppm), U (1.6 ppm), Nb (1.6 ppm), are medium (Sr – 109.2–155.0 ppm; Ba – 4–30 ppm) but the content of Rb is low (0.1–1.7 ppm). The amounts of Zr (up to 35.9 ppm), Th (up to 3.3 ppm) and Hf (up to 0.9 ppm) are comparable to the DC1 samples. The abundance of Pb (up to 33.2 ppm), Zn (up to 86 ppm), Cu (up to 2.8 ppm) and Mo (up to 0.2 ppm) are markedly lower.

The DR3 samples have small amounts of the most trace elements compared to the rock samples described above (

Table 4 and

Table 5). Only the content of Sr (184.8–333.8 ppm) is medium and it is higher than that of the DC2 samples.

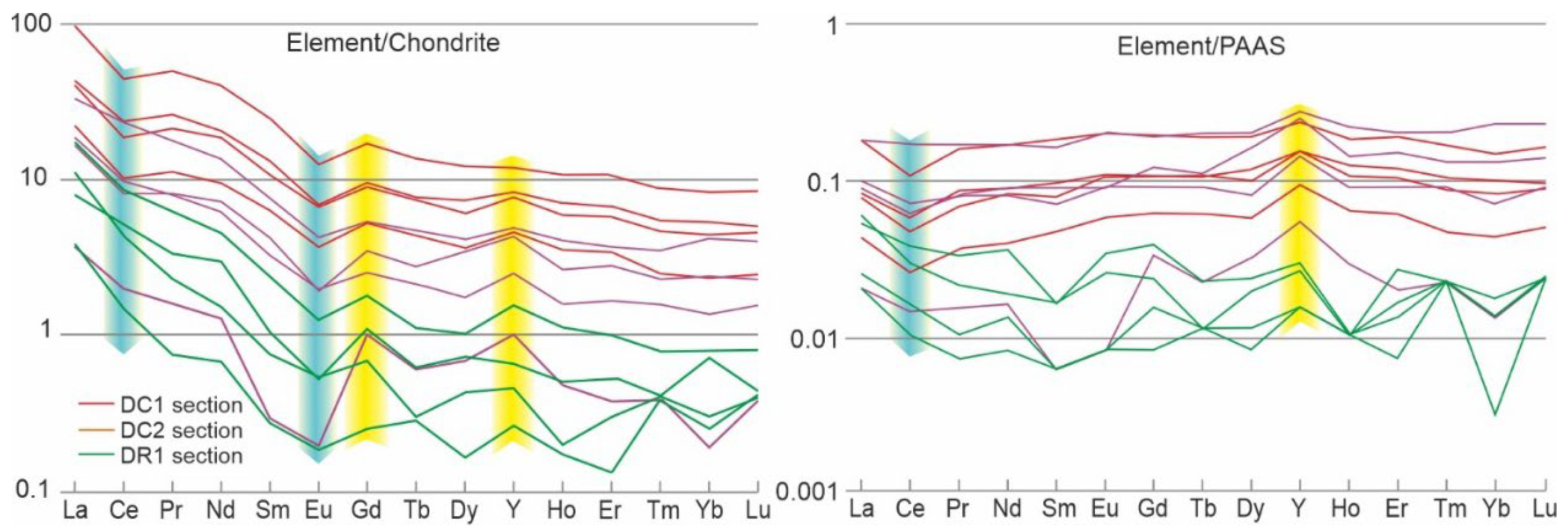

4.6. REE Signatures

The studied sediments display a variable content of REE (

Table 4 and

Table 5). In the red limestones (section DC1; av. 60.3 ppm) it is higher than in the grey limestones containing pink spots (section DC2; av. 23.2 ppm), and much higher than in the grey limestones containing ferruginous discolourations and coatings visible in microscopic observations (section DR3; av. 5.7 ppm). The chondrite- and PAAS-normalized REE + Y patterns were similar between the sections in the Czernka Valley (DC1 and DC2), emphasized by Ce and Eu negative anomalies with Gd and Y positive anomalies (

Figure 13). This pattern for limestones from the Racławka Valley (section DR2) differs among the Light-REE in the lack of cerium anomaly. The materials studied from the Czernka Valley exhibit superchondritic Y/Ho ratios (av. 35–57 in particular sections). In turn, the lowest values (32–39) are characteristic of the DC1 section. The Ce/Ce

∗ average values in limestones vary significantly between the sections with range from 0.73 (DC1 section) to 1.6 (DR3 section). The values of Dy

N/Sm

N ratio, a signature of diagenetic enrichment among the MREE [

58] are above 1.2, excluding a single sample in the Czernka Valley (DC1.01). The Gd/Gd

∗ average values in limestones vary significantly between the sections with range from 20 (DC1 section) to 160 (DR3 section).

5. Discussion

5.1. Bacterial Origin of Rust-Coloured and Brown Pigments

The thin-sections view of samples from DC1 profile, using TLM at magnifications x 1000, show spherical to oval dark brown structures 1–2 micrometers across (

Figure 4e,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 14). They occur as single capsules or tubes enclosed in a spary binder (e.g.,

Figure 14a,b,c), arranged linearly (

Figure 14a) between crystal walls (e.g.,

Figure 4e) or appear in groups of several specimens (

Figure 11c,

Figure 14c). The single capsule is hollow inside and has a wall about 0.1 µm thick. SEM-EDS and Raman analysis showed that the capsules walls contain large amount of iron oxides and hydroxides (

Figure 6 and

Figure 11), therefore may be a remnant of the original bacterial sheath from the IRB group. Oval to elongated structures of sizes resembling bacterial cells are often arranged linearly or in rounded consorcia (

Figure 11c and

Figure 14–c). This indicates a similarity to IRB from the

Sphaerotilus-Leptothrix group by the arrangement of individual cells in bacterial sheaths. In some places, empty tubular structures are visible, which may also be remnants of specimens of this group of bacteria (

Figure 14c). Some of the specimens possess stalked, twisted ribbon-like structure (

Figure 14b) resembling IRB from

Galionella group or another Fe oxidizers as

Mariprofundus ferrooxydans (e.g., [

59,

60,

61]).

Further evidence for the association of rusty discolourations with bacterial origin are oval, dark brown pigment clusters usually surrounded by rusty, translucent haloes with an unevenly coloured, floccular structure, visible under light microscope (

Figure 14d). These structures resemble the bacterial holdfasts, which general outline and shape might be similar to bacteria from the

Sphaerotilus-Leptothrix group. Particular similarity to the present-day species of

Leptothrix lopholea and

Leptothrix cholodnii can be seen [

5,

62].

The structures that occur in the examined samples from the DC1 outcrop can be classified as bacteria only on the basis of above mentioned features because in the case of fossil material from the late Paleozoic, this is the only available criterion. It is not possible to assess the belonging to any group of bacteria (or even Archaea) using microbiological and chemical methods applied to modern material. For this reason, we stick to the term “bacteria-like” or “resembling bacteria” to fully reflect the above impossibility of classifying the above structures as bacteria. However, in some cases, especially when bacteria precipitate inorganic compounds such as iron oxides or calcium carbonate outside the cell membrane, they may preserved in the fossil record unique shapes and various types of bacterial sheaths, and filaments, corresponding to features of specific bacterial species cf. [

61].

5.2. Timing for IRB Growth

The rocks in which the bacteria-like remnants are found have a long geological history. They belong to a nearly 1,200 m long sequence of the Upper Paleozoic carbonate platform [

63]. Carbonate sedimentation occurred in a relatively shallow part of the epicontinental Moravo-Silesian Basin (MSB), along the shelves bordering the Upper Silesian Block – a part of a larger tectonic unit – the Brunovistulicum microcontinent [

32,

34,

64]. Older basement of this tectonic structure is interpreted as ancient piece derived from the Gondwana continent [

65].

The taphonomic analysis shows that bacteria-like remnants are not associated with the sedimentation in shallow marine environment of the original limestones. First of all, bacteria are present in part of limestone with sparite cement, which occurs in the studied rocks as narrow, several millimeter to several centimeters zones, unrelated to bedding and cutting rocks in different directions (

Figure 10a,b), also across microfossils as different types of foraminifers or echinoderm plates (

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). Rusty pigmentation occurs especially in the originally porous parts of the rock, which are microfossils chambers or porous walls of skeletal remains (

Figure 3c,d,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 11e). Additionally, bacterium-like structures are not associated with bacterial mats, which could have formed in the sedimentary environment of the host-rocks at that time [

55].

In order to draw conclusions about the origin of bacteria in the studied rocks, it is important to note that bacterial remnants are present locally; only in samples from the DC1 profile. In other profiles (DC2, DR3), bacteria were not observed despite the fact that they represent similar lithotypes of shallow-water limestones.

The microfacies analysis of the reddish colourations inside the microfossils walls and around them (

Figure 3c,d), as well as shape of the walls and their vicinity (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) show that their origin is partly related to the dissolution process. The thinnest infillings were developed as seams bordering bioclasts, which usually consist of calcite spare, while they were surrounded by micrite. Reddish (iron oxides) seams started to develop in places where calcitic bioclast contacted with micrite. This shows that fissures can be opened by leaching micrite from the host limestone and successively filling them with iron oxides, which are associated with calcite spar and quartz crystals. The more resistant part of foraminiferal chambers or echinoid plates were left as residue (

Figure 11e). Additionally, the crystals of calcitic spar are rounded (

Figure 7) indicating their stepwise dissolution and crystallization during subsequent hydrothermal pulses.

This may indicate that bacterial growth occurred in the originally empty micropores of the skeletons and shells of microfossils, between bioclasts, or in secondary voids formed during the selective dissolution of micrite or smaller sparite crystals. The spatial relationship of sparite crystals to iron deposits and bacteria-like remnants indicates that iron oxide precipitation and sparite crystallization were contemporaneous processes. For the development of IRB, bacteria had to be solutions with increased iron content to such a level that individual species of bacteria could encrust cell membranes during their life. Samples from the DC1 profile contain increased contents of Fe, and in addition to this, other elements constituting a trace of the influence of hydrothermal conditions on these rocks. These solutions had to be relatively cold if IRB could live during their circulation. Another indicator of low-temperature hydrothermal activity is enrichment in elements like Ba, Sr, As and Sb (e.g., [

66]). Significantly increased contents of these elements compared to samples from other tested profiles occur in the DC1 profile.

Among the studied platform succession sediments, the IRB-like structures were not found in the Tournaisian limestones (DC2 profile), whose location right next to the same fault as the red limestones from the DC1 exposure suggests the possibility of their infiltration by hydrothermal waters. However, among the oxides whose elevated content may indicate hydrothermal origin, the composition and weight fraction differs from that in the DC1 profile. Additionally, the content of iron oxides and hydroxides is over 50 percent lower. Differences in chemical composition suggest different origins, and perhaps different durations, of hydrothermal solutions in these nearby areas. At the same time, the lack of visible structures resembling IRB bacteria indicates low iron concentrations in the original solutions circulating in the rock, which were insufficient for bacterial formation to produce inorganic coatings. This may also indicate the higher temperature of the solutions interacting in this part of the carbonate complex.

In turn, the limestone succession from DR3 profile is characterized by the typical marine limestone content of oxides, accessory elements, and rare earth elements. The biotic components and the state of preservation of the clasts indicate a high-energy sedimentary environment. Therefore, the sparite present in these samples likely crystallized in the sedimentary environment and does not originate from subsequent recrystallization of micrite during the circulation of hydrothermal solutions.

The local scope of influence of hydrothermal solutions and the possibility of temporary development of IRB in them only in the area of neptunian dikes is evidenced by the fact that total REE content measured from the studied limestones is comparable to that of normal seawater (25–26 ppm;

Table 5; e.g., [

67]) or even lower in the case of the Si-enriched dyke (20 ppm). The same conclusion as above is suggested here on the basis of the PAAS-normalized REE patterns of the material from the dykes which were more or less flat, excluding the Y enrichment (

Figure 13). This is similar to carbonate and authigenic marine phases, which mainly produced a seawater-like REE pattern [

68]. The REE of the host rock was slightly higher (ca 20%;

Table 5), which may reflect the contamination of phosphates in the echinoderm-foraminiferal limestone observed in thin-sections of the rock (

Figure 11e).

5.3. Potential Sources of Hydrothermal Fluids

Here, we consider two potential fluid sources, the first of which could be related to post-Variscan magmatism and volcanism, and the second – to a stage of Mesozoic sulphide mineralization. The first of these episodes is well documented in the study area, the second – in its immediate vicinity.

Variscan compressional deformations in this area, which took place at the turn of the Moscovian and Kasimovian (Westphalian and Stephanian), resulted in the formation of gentle folds and faults with a latitudinal course and strike-slip character [

42]. In this phase, the Dębnik anticline was formed, among others (

Figure 1c). Starting from the Gzhelian (Stephanian B), this area experienced a phase of accumulation of post-orogenic deposits (arkosic sandstones and conglomerates containing silicified

Dadoxylon tree trunks) and the onset of terrestrial volcanism, which lasted until the Early Permian (e.g., [

69]). Volcanic, subvolcanic and volcanoclastic rocks occur in this area on a surface of approx. 200 km

2 in the form of lava flows and small intrusions in the form of domes, laccoliths and veins, and locally tuffs of an ignimbrite nature (e.g., [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

70]). The intrusions are local and do not form continuous covers, although they are associated with the Kraków–Lubliniec tectonic zone which divides the Upper Silesian Block from the Małopolska Block (

Figure 1b) [

32,

43]. This volcanism was bimodal, from andesitic to rhyolitic, and a history of more than 100 years of research indicates that both varieties of volcanites appear to be genetically related and derived from magmas originating from the lithospheric mantle and crust (e.g., [

30]).

Zircon U–Pb dating of various igneous rocks (granodiorites, dacites, lamprophyre and diabase) from this igneous belt showed that magmatism spanned within a short-lived event, between 303.8 ± 2.2 and 292.7 ± 4.9 Ma [

30]. Felsic calc-alkaline magmatism was characteristic for the oldest interval (during the latest Carboniferous), followed by slightly alkaline volcanism of mafic–intermediate composition (the oldest Permian). The last one concerns the lamprophyre and diabase dikes located near the study area, in the 20 km wide zone along the Kraków – Lubliniec tectonic zone [

30]. The oldest of them is the so-called granodiorite II from the Zawiercie region located in the Lubliniec–Kraków Fault Zone, which has been dated (Sr-Rb) to 340 ± 4 Ma [

71].

This type of magmatism is associated with the Cu-Mo mineralization in this area occurring both in porphyry-type deposits, and in the surrounding skarn-contact metasomatic and vein-type deposits [

44,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79] forming a system of quartz veins with ore minerals. This mineralization was related to felsic magmatism, and could be the most likely source of the elevated trace element values found in the Czernka Valley. In turn, the younger alkaline volcanism is characterized by the REE mineralization of metasomatic hydrothermal type [

80], which was not confirmed in the examined deposits.

Another possibility of the origin of the fluid sources for IRB-bacteria that we considered, could be related to the Mississippi Valley-type Zn-Pb mineralization hosted mainly by the Middle Triassic limestones and dolomites (Muschelkalk) which is of economic importance in a neighbouring region, just west of the study area [

31,

52]. Most probably, these ore fluids have been also related to the Variscan igneous rocks which gave rise the polymetallic ores, and later they became remobilized by heat flow and redeposited in various sedimentary successions [

81]. The timing of the remobilization of older ores and the origin of fluids is still debated. They are most likely related to crustal extension during the Mesozoic plate-tectonic reorganization (?late Triassic according to [

81] or ?Early Cretaceous according to [

82]). This type of mineralization is also known in association with Devonian–Permian rocks, which occur close to the studied sediments, in the Czernka Valley [

53]. This proximity to the studied profiles DC1 and DC2, and the fact that Pb-Zn mineralization was associated with low-temperature hydrothermal fluids, leads us to consider this Fe source for the IRB growth. However, our geochemical data are insufficient in this respect, and geological publications contain data on trace element content without detailed information on whether they originate from mining fields or their transition zones, or from “pure” limestones or dolomites (e.g., [

83]). For this reason, we leave this issue open for further geochemical studies.

6. Conclusions

1. In the Visean part of the thick limestone succession located along the Upper Silesian Block (northern part of the Brunivitulicum terrane) there are local zones of red-coloured rocks, which, based on morphological and chemical evidence, have been classified here as bacterial structures. These are spherical or oval forms, 1–2 µm in diameter, that occur as individual capsules or tubes arranged linearly between the walls of calcite crystals. The single capsule is hollow inside and has a wall approximately 0.1 µm thick, which contains a large amount of iron oxides and oxyhydroxides; this may be a remnant of the original bacterial sheath. Some oval, dark brown pigment clusters, surrounded by translucent halos with a floccular structure, resemble the bacterial holdfasts. We present here morphology and chemistry of the microstructures showing their similarities to IRB from the present-day Sphaerotilus-Leptothrix group, the Galionella group, and the species Mariprofundus ferrooxydans.

2. The taphonomic analysis shows that bacteria-like remnants are not associated with the sedimentation of shallow marine carbonate mud. They are present only in narrow zones of a few millimeters to several centimeters wide, unrelated to bedding, and also occur across various microfossils. Based on microfacies analysis, we indicate that bacterial growth occurred in the originally empty micropores of microfossil skeletons and shells, between bioclasts, or in secondary voids formed during the selective dissolution of micrite or smaller sparite crystals. The dissolution of primary micrite and the subsequent filling of spaces with iron oxides were associated with repeated hydrothermal pulses. The solutions must have been relatively cold which is evidenced by the increased content of Ba, Sr, As, and Sb.

3. Taking into account the types of mineralization associated with post-Variscan magmatism and volcanism, well documented in the immediate vicinity of the studied Lower Carboniferous sediment succession, we suggest that the hydrothermal pulses that we associate with the formation of bacterial structures are probably related to felsite magmatism (Late Carboniferous), which was characterized, among others, by Cu-Mo mineralization, typical of many neighbouring porphyry deposits and skarn metasomatic deposits. However, this issue requires further geochemical studies of these sediments, in conjunction with analogous studies of carbonate rocks around the Zn-Pb mineralization zones, but outside the ore bodies and their transition zones.

Figure 1.

A. The study area (red rectangle) against the background of the general tectonic units of Europe.

B. The study area (blue rectangle) against the background of the Paleozoic basement of the southern edge of the Silesian-Cracow Monocline; mutual position of tectonic units after Żelaźniewicz et al. [

83].

C. Location of the studied lithological profiles on the background of the geological map of the southern part of the Silesian-Cracow Monocline [

84].

Figure 1.

A. The study area (red rectangle) against the background of the general tectonic units of Europe.

B. The study area (blue rectangle) against the background of the Paleozoic basement of the southern edge of the Silesian-Cracow Monocline; mutual position of tectonic units after Żelaźniewicz et al. [

83].

C. Location of the studied lithological profiles on the background of the geological map of the southern part of the Silesian-Cracow Monocline [

84].

Figure 2.

Research profiles in the Czernka Valley (DC1, DC2) and in the Racławka Valley (DR3) with samples selected for microfacial, geochemical and petrographic analyses.

Figure 2.

Research profiles in the Czernka Valley (DC1, DC2) and in the Racławka Valley (DR3) with samples selected for microfacial, geochemical and petrographic analyses.

Figure 3.

Details of limestones exposed in the DC1 profile (Red Wall). A. General view of the exposure state with the middle- to thick-bedded Visean limestones. B. Cross-sections of brachiopod shells visible in the bed in the lower part of the exposure. C, D. Microscopic images (TLM) of the red limestone microfacies from the DC1 profile (sample DC1.4) in plane-polarized light (C) and plane-polarized light with reflected light (EPI; D) showing occurrence of bioclasts surrounded by rusty-brown coatings, which appear red and/or yellow in reflected light depending on the occurrence and packing of iron minerals.

Figure 3.

Details of limestones exposed in the DC1 profile (Red Wall). A. General view of the exposure state with the middle- to thick-bedded Visean limestones. B. Cross-sections of brachiopod shells visible in the bed in the lower part of the exposure. C, D. Microscopic images (TLM) of the red limestone microfacies from the DC1 profile (sample DC1.4) in plane-polarized light (C) and plane-polarized light with reflected light (EPI; D) showing occurrence of bioclasts surrounded by rusty-brown coatings, which appear red and/or yellow in reflected light depending on the occurrence and packing of iron minerals.

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of bioclasts and spary binder in the sample DC1.4. Foraminifers (A) and echinoids plates (B) surrounding by rusty coatings and with rusty fillings of originally porous parts of the skeletons visible in TLM plane polarized light. C,D. The same types of bioclasts observed in SEM-BSE imaging, showing different shades of grey corresponding to different structures and arrangements of calcite crystals, while white dots correspond to iron-containing particles. E. Spary binder between bioclasts (TLM plane polarized light) and rusty pigment, when viewed at high magnification consisting of numerous small oval or elongated elements resembling in size and shape the casings of iron bacteria.

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of bioclasts and spary binder in the sample DC1.4. Foraminifers (A) and echinoids plates (B) surrounding by rusty coatings and with rusty fillings of originally porous parts of the skeletons visible in TLM plane polarized light. C,D. The same types of bioclasts observed in SEM-BSE imaging, showing different shades of grey corresponding to different structures and arrangements of calcite crystals, while white dots correspond to iron-containing particles. E. Spary binder between bioclasts (TLM plane polarized light) and rusty pigment, when viewed at high magnification consisting of numerous small oval or elongated elements resembling in size and shape the casings of iron bacteria.

Figure 5.

Chemical SEM-EDS microanalysis of sample DC1.4 in SEM-BSE image. (1) Light gray calcite clusters. (2) Dark gray dolomite clusters. (3) White Fe oxides/oxyhydroxides.

Figure 5.

Chemical SEM-EDS microanalysis of sample DC1.4 in SEM-BSE image. (1) Light gray calcite clusters. (2) Dark gray dolomite clusters. (3) White Fe oxides/oxyhydroxides.

Figure 6.

SEM-EDS detailed chemical mapping of the selected area of sample DC1.4 showing the occurrence of the elements Mg, Si, Ca, Mn and Fe in the oxide form and the overlapping of the areas of occurrence of individual elements, proving their common origin. The graph shows the total content of the analyzed elements from the entire tested surface.

Figure 6.

SEM-EDS detailed chemical mapping of the selected area of sample DC1.4 showing the occurrence of the elements Mg, Si, Ca, Mn and Fe in the oxide form and the overlapping of the areas of occurrence of individual elements, proving their common origin. The graph shows the total content of the analyzed elements from the entire tested surface.

Figure 7.

A. Photomicrographs (TLM) of thin section of sample DC1.5 shows rusty brown pigment between sparite crystals and rusty pigmentation within individual crystals, plane-polarized light. B,C. SEM-EDS imaging of the surface of sample DC1.5 showing that the rusty brown pigmentation is composed of Fe oxides/oxyhydroxides.

Figure 7.

A. Photomicrographs (TLM) of thin section of sample DC1.5 shows rusty brown pigment between sparite crystals and rusty pigmentation within individual crystals, plane-polarized light. B,C. SEM-EDS imaging of the surface of sample DC1.5 showing that the rusty brown pigmentation is composed of Fe oxides/oxyhydroxides.

Figure 8.

A. Photomicrograph of a cross-section through an echinoderm plate with the original microstructure, where the pores have been filled by rust-colored pigment (sample DC1.5), plane-polarized light. B. Close-up of image A showing that the rust pigment is composed partly of oval and elongated forms resembling bacteria in size and shape, plane-polarized light.

Figure 8.

A. Photomicrograph of a cross-section through an echinoderm plate with the original microstructure, where the pores have been filled by rust-colored pigment (sample DC1.5), plane-polarized light. B. Close-up of image A showing that the rust pigment is composed partly of oval and elongated forms resembling bacteria in size and shape, plane-polarized light.

Figure 9.

A. Photomicrograph of bioclast left from an echinoderm plate, where rusty brown pigmentation is found within the original void and along the contact with the surrounding micrite (sample CD1.5), plane-polarized-light. B. Close-up of the exterior showing clumps of brown pigment and accompanying oval structures resembling bacteria, plane-polarized-light. C. Close-up of the internal part of the bioclast, showing additional bright flocs surrounding pigment tufts resembling bacterial holdfasts, plane-polarized-light.

Figure 9.

A. Photomicrograph of bioclast left from an echinoderm plate, where rusty brown pigmentation is found within the original void and along the contact with the surrounding micrite (sample CD1.5), plane-polarized-light. B. Close-up of the exterior showing clumps of brown pigment and accompanying oval structures resembling bacteria, plane-polarized-light. C. Close-up of the internal part of the bioclast, showing additional bright flocs surrounding pigment tufts resembling bacterial holdfasts, plane-polarized-light.

Figure 10.

Iron oxides in sample DC1.2. A. Microscopic image (TLM) of vein infillings and disseminated pigment within carbonate mass. B. The same image in plane-polarized light with reflected light (EPI). C. SEM-BSE image of central part of A image. D–F. Closer look at areas from C image; D. Compact, botryoidal cryptocrystalline mass. E. Cryptocrystalline porous aggregates (Kl – kaolinite). F. Tiny cryptocrystalline aggregates (Py – pyrite; 3 – Fe oxide pseudomorphs after pyrite). G. Closer view of F image showing accumulation of Mn oxides (probably coronadite). H. Typical processed Raman spectrum showing diagnostic goethite features.

Figure 10.

Iron oxides in sample DC1.2. A. Microscopic image (TLM) of vein infillings and disseminated pigment within carbonate mass. B. The same image in plane-polarized light with reflected light (EPI). C. SEM-BSE image of central part of A image. D–F. Closer look at areas from C image; D. Compact, botryoidal cryptocrystalline mass. E. Cryptocrystalline porous aggregates (Kl – kaolinite). F. Tiny cryptocrystalline aggregates (Py – pyrite; 3 – Fe oxide pseudomorphs after pyrite). G. Closer view of F image showing accumulation of Mn oxides (probably coronadite). H. Typical processed Raman spectrum showing diagnostic goethite features.

Figure 11.

Iron oxides in sample DC1.4.2. A. Pore infillings, SEM-BSE+SE image. B. A detail of A - cryptocrystalline hematite, SEM-SE image. (Q – quartz, Kl – kaolinite, Cal – calcite). C. Cryptocrystalline aggregates (1) of possibly bacterial origin (Q – quartz, Cal – calcite, Kl – kaolinite). D. Pseudomorphs after pyrite, SEM-BSE+SE (Q – quartz, Cal – calcite, B – barite). E. Echinoderm plate with porous microstructure, SEM-BSE+SE image F. Typical processed Raman spectrum showing diagnostic hematite features.

Figure 11.

Iron oxides in sample DC1.4.2. A. Pore infillings, SEM-BSE+SE image. B. A detail of A - cryptocrystalline hematite, SEM-SE image. (Q – quartz, Kl – kaolinite, Cal – calcite). C. Cryptocrystalline aggregates (1) of possibly bacterial origin (Q – quartz, Cal – calcite, Kl – kaolinite). D. Pseudomorphs after pyrite, SEM-BSE+SE (Q – quartz, Cal – calcite, B – barite). E. Echinoderm plate with porous microstructure, SEM-BSE+SE image F. Typical processed Raman spectrum showing diagnostic hematite features.

Figure 12.

Correlation graphs for individual pairs of oxides content in all samples investigated.

Figure 12.

Correlation graphs for individual pairs of oxides content in all samples investigated.

Figure 13.

REE curves of the studied samples, normalized to chondrites [

86] and Post-Archean Australian Shale standards [

87,

88].

Figure 13.

REE curves of the studied samples, normalized to chondrites [

86] and Post-Archean Australian Shale standards [

87,

88].

Figure 14.

Bacteria-like structures in rusty brown pigment in samples of DC1 sections, plane-polarized-light. A. Ovals contain Fe oxide/oxyhydroxide arranged as single capsules inside crystals or chains located between crystals of spary binder. B. Twisted chains and clusters of spheres resembling bacterial-like consortia. C. Spherical and elongated Fe oxide/oxyhydroxide structures resembling iron bacteria capsules. D. Flocks of rusty brown pigment with thin flocs and oval capsules resembling bacterial holdfasts.

Figure 14.

Bacteria-like structures in rusty brown pigment in samples of DC1 sections, plane-polarized-light. A. Ovals contain Fe oxide/oxyhydroxide arranged as single capsules inside crystals or chains located between crystals of spary binder. B. Twisted chains and clusters of spheres resembling bacterial-like consortia. C. Spherical and elongated Fe oxide/oxyhydroxide structures resembling iron bacteria capsules. D. Flocks of rusty brown pigment with thin flocs and oval capsules resembling bacterial holdfasts.

Table 1.

The content of major elements (wt%) in the rock samples studied. DC 1 – strong hydrothermally altered red limestones (the Czernka Valley – the Red Wall); DC 2 - weak/poorly hydrothermally altered pinkish gray limestones (the Czernka Valley); DR 3 - non hydrothermally altered gray limestones (the Racławka Valley). .

Table 1.

The content of major elements (wt%) in the rock samples studied. DC 1 – strong hydrothermally altered red limestones (the Czernka Valley – the Red Wall); DC 2 - weak/poorly hydrothermally altered pinkish gray limestones (the Czernka Valley); DR 3 - non hydrothermally altered gray limestones (the Racławka Valley). .

Table 2.

Average content (wt%) of major elements in the rock samples studied. DC 1 – strong hydrothermally altered red limestones (the Czernka Valley – the Red Wall); DC 2 - weak/poorly hydrothermally altered pinkish gray limestones (the Czernka Valley); DR 3 - non hydrothermally altered gray limestones (the Racławka Valley).

Table 2.

Average content (wt%) of major elements in the rock samples studied. DC 1 – strong hydrothermally altered red limestones (the Czernka Valley – the Red Wall); DC 2 - weak/poorly hydrothermally altered pinkish gray limestones (the Czernka Valley); DR 3 - non hydrothermally altered gray limestones (the Racławka Valley).

Table 3.

The Pearson coefficient values, calculated for individual pairs of oxides content in all samples from the DC1 section.

Table 3.

The Pearson coefficient values, calculated for individual pairs of oxides content in all samples from the DC1 section.

Table 4.

The content of trace elements (ppm) in the rock samples studied. DC 1 – strong hydrothermally altered red limestones (the Czernka Valley – the Red Wall); DC 2 - weak/poorly hydrothermally altered pinkish gray limestones (the Czernka Valley); DR 3 - non hydrothermally altered gray limestones (the Racławka Valley). .

Table 4.

The content of trace elements (ppm) in the rock samples studied. DC 1 – strong hydrothermally altered red limestones (the Czernka Valley – the Red Wall); DC 2 - weak/poorly hydrothermally altered pinkish gray limestones (the Czernka Valley); DR 3 - non hydrothermally altered gray limestones (the Racławka Valley). .

Table 5.

Average content (ppm) of trace elements in the rock samples studied. DC 1 – strong hydrothermally altered red limestones (the Red Wall – the Czernka Valley); DC 2 - weak/poorly hydrothermally altered pinkish gray limestones (the Czernka Valley); DR 3 - non hydrothermally altered gray limestones (the Racławka Valley).

Table 5.

Average content (ppm) of trace elements in the rock samples studied. DC 1 – strong hydrothermally altered red limestones (the Red Wall – the Czernka Valley); DC 2 - weak/poorly hydrothermally altered pinkish gray limestones (the Czernka Valley); DR 3 - non hydrothermally altered gray limestones (the Racławka Valley).