1. Introduction

Clavicular fractures (CF) rank among the ten most common fractures in adults, frequently occurring in men during cycling or other leisure activities [

1,

2]. Undisplaced CFs are typically managed conservatively, whereas displaced fractures often require surgical fixation to achieve optimal functional outcomes [

3,

4]. The initial pain associated with CF, whether displaced or not, can range from moderate to severe, posing a significant challenge during the initial medical treatment [

5]. Consequently, emergency physicians, orthopedic and trauma surgeons, as well as anesthesiologists, are frequently challenged to provide adequate analgesia for patients with acute CF. Typically, multimodal analgesic regimens are employed, though they often exhibit variable efficacy. Furthermore, particularly opioids [

6,

7] can cause undesired side effects such as drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting. A straightforward alternative to medical treatment of acute pain in CF patients in an emergency department (ED) setting can be the use of selective peripheral nerve blocks (PNB).

PNBs have been reported for clavicle surgery, either in combination with general anesthesia or as a single technique. Recent cadaveric studies have revealed a complex innervation of the clavicle, involving the subclavian nerve, the lateral pectoral nerve, and the supraclavicular nerves. As these nerves originate from both the interscalene brachial plexus and the cervical plexus, effective anesthesia of the clavicle requires blockade of both plexuses [

8]. For this reason, multimodal approaches - including surgical site infiltration and various PNB techniques targeting branches of the cervical and brachial plexus - have been extensively described [

9,

10,

11]. Among these, the combination of interscalene brachial plexus block (ISB) and cervical plexus block (CPB) is recommended as the regional technique of choice for clavicle surgery [

12].

When considering initial pain management prior to clavicle surgery, due to the underlying anatomical conditions an ISB carries the risk of phrenic nerve (PN) involvement which may result in impairment of respiratory function. Investigations into PN-sparing PNBs following shoulder surgery highlight the importance of avoiding inadvertent diaphragmatic dysfunction associated with certain block techniques [

13]. An accurately performed intermediate CPB, however, should theoretically exclude the risk of an unintended PN block. However, such block unnecessarily involves other nerves of the cervical plexus such as the great auricular nerve (GAN), the transverse cervical nerve (TCN), and the lesser occipital nerve (LON). This can compromise patient comfort despite not being a complication per se. Since the supraclavicular nerves (SCLN) are the main sensory providers to the clavicle [

8,

9,

14], and can be visualized by high resolution ultrasound imaging (HRUI), we hypothesized that an ultrasound-guided selective SCLN block could improve initial pain management in patients with acute CF. We therefore performed this randomized controlled study in patients with acute CF to evaluate the effect of a SCLN block on pain relief compared to standard protocol without regional anesthesia (RA) in an ED setting.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was a single-center, parallel, randomized control clinical trial comparing an SCLN-block based pain management strategy with conventional pain management. Adult ED-patients (older than 18 years) with isolated CF to be operated were eligible for the study. Exclusion criteria included contraindications to RA (e.g., local site infection, allergy to local anesthetics), multiple traumata, inability to cooperate (mental or linguistic), chronic analgesic use for other reasons, or neuromuscular defects. The patients were recruited at the daytime ED of a non-academic hospital. Recruitment and randomization were performed by the medical staff of the ED.

Using a computer-generated random allocation sequence created by an independent statistician, patients were randomly assigned to either the block group or the control group (standard therapy) with a 1:1 allocation ratio. Neither stratification nor block randomization was used. Allocation numbers were sealed in opaque envelopes and opened by a nurse not involved in patient assessment. Blinding was not possible due to an obvious sensory block in the block group. Following institutional approval (Ethik Kommission Nordwestschweiz, reference number BASEC2020-03054), the study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04685291) on December 28, 2020. Recruitment started on April 15, 2021. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave oral and written informed consent. Reporting of the study adheres to the Consolidation Standards of Reporting Clinical Trials (CONSORT) Statement [

15].

Blocks were performed in the ED by operators trained in ultrasound-guided PNB. Appropriate ASA monitoring and peripheral intravenous access were applied. Strict aseptic precautions were followed, including sterile draping and covering of the ultrasound probe. Two ultrasound systems with high-frequency linear array probes (Samsung RS85 EVO, LA4-18B, or Samsung HS60 High-End, LA4-18BD) were used.

With the patient supine and the head slightly tilted to the opposite side, the ultrasound probe was placed in a transverse plane in the posterior cervical triangle at the level of the transverse process of the 4th cervical vertebra to identify the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM). The superficial cervical fascia (SCF) and the prevertebral fascia (PVF) were depicted. The SCLN was depicted by HRUI as a strong cluster emerging from the ansa cervicalis between C3 and C4 and C4 itself underneath the PVF (

Figure 1). The PN also emerging mainly from the ventral ramus of the 4th cervical spinal nerve, was identified close to the SCLN, both underneath the PVF in the same compartment. During their course to the target areas, the SCLN ascend through the PVF, traveling between the two fascial layers before becoming superficial to reach the clavicle. In contrast, the PN remains deep to the PVF and lies ventral to the anterior scalene muscle (

Figure 2).

In the interfascial space, the GAN was identified as an additional sonographic landmark emerging from the cervical plexus. It was identified by its characteristic double dot appearance after looping around the lateral border of the SCM before running on top of the SCM towards the ear (

Figure 1). From this position, by shifting the probe slightly caudally, the passage of the SCLN through the PVF was depicted. After piercing the PVF, the SCLN typically divides into three bundles of small nerves (medial, intermediate, and lateral) before becoming superficial (

Figure 2). An injection point was chosen where either the cluster of the trunk or all three bundles were close together caudad from the GAN (

Figure 3). The identification of the SCLN and the blocking procedure are demonstrated in a video in the supplemental material.

In case of failure to clearly identify the passage of the SCLN through the PVF, it was recommended to perform an intermediate CPB taking the GAN as sonographic landmark. After skin infiltration with up to 1 ml of local anesthetic (LA) injection was performed in an in-plane approach from lateral-posterior to medial using an echogenic needle (PAJUNK SonoTAP 24G x 40 mm). Bupivacaine 0.5% (3 ml) with 75 µg clonidine (0.5 ml) [

16] was slowly injected under HRUI control, ensuring accurate injection around the SCLN strictly above the PVF. Blocks were considered successful if pain scores decreased to less than 3 within five minutes. No further testing was routinely performed. Procedures were recorded as video loops and stored on the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) of our clinic.

Use of pain medication was under control of the study as long as patients stayed at the ED. After discharge from the ED to other hospital department, pain management followed the local routine. After discharge to home, pain management was handled by the patients themselves. At the ED upon admission and prior to allocation, all patients initially received standard pain medication consisting of 400 mg ibuprofen and 1000 mg metamizole, administered orally or intravenously according to patient preference. Patients with known intolerance or allergies to ibuprofen or metamizole received paracetamol 1000 mg, respectively. In the control group, patients continued to receive standard protocol treatment, which includes 400 mg ibuprofen every 8 hours and 1000 mg metamizole every 6 hours as basic medication. Patients over 70 years old received 60 mg acemetacin every 8 hours instead of ibuprofen, with metamizole administered as described above. Oxycodone was used as rescue medication if patients rated their pain as severe on the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS).

After receiving the block, patients in the block group initially received no basic medication. They were given ibuprofen 400 mg or acemetacin 60 mg (patients over 70 years) as first-line reserve medication and metamizole 1000 mg as second-line, both on request. Likewise, patients received oxycodone as rescue medication if patients rated their pain as severe on the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS).

Primary outcomes were the pain level and patient satisfaction. Pain intensity was measured by an 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS): 0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain imaginable. Patients were asked to rate their pain upon admission and at 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 hours post-admission. During their hospital stay, patients were contacted by the principal investigator (ES) for assessment. Patients discharged before 24 hours received a questionnaire including the same time scale and were contacted again after 24 hours. For assessment of patient satisfaction, patients responded to five questions regarding their pain management and block procedure experience (Supplemental

Table S1 in online supplemental material) after 24 hours.

Secondary outcomes included the time to first request of pain medication after consent and the amount of analgesics used within the first 24 hours after admission. A potential impact on patient management was assessed by the frequency of clavicle surgery and the frequency of discharge home within 24 hours. Safety was assessed by patient reported adverse reactions - classified according to patient sensation as mild, moderate, or severe – and patient reported adverse events, in particular dyspnoea, nausea or vomiting within the first 24 hours.

From the patient records, the following information was extracted: age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status (ASA score), body mass index (BMI), type of accident, dominant side and fracture type. The later was classified according to the classification of Allman [

17], which fits best for the anatomical consideration of a nerve block in comparison to other classifications [

18].

Based on casuistic application by the principal investigator (ES), a pronounced analgesic effect over 24 hours was anticipated. Sample size calculations were based on an effect size of d=0.8: aiming for 80% power at a 5% significance level, a one-sided t-test required 21 patients per treatment group. Pain intensity was analyzed at each timepoint by computing the mean intensity, visualizing the full distribution in stacked bar charts, and assessing statistical significance using a Wilcoxon rank sum test. The time spent beyond a certain pain level within the first 12 hours was determined by interpolation between the assessment time points. The distribution of this time was depicted using cumulative distribution functions. The distribution of the time until the first request for pain medication was described by the median and the fraction of patients with a request within one hour. The Kaplan-Meier estimator was used to estimate the distribution, regarding discharge as censoring time point.

Patient-reported experience measures were visualized using stacked bar charts, and statistical significance was assessed using a Wilcoxon rank sum test. For each analgesic drug, the frequency of request, the mean and range of doses given between admission and 24 hours post-admission were reported. With respect to adverse reactions and adverse events, the frequency was reported.

3. Results

Recruitment, Randomization and Patient Characteristics

Patients were recruited between April 15, 2021, and July 6, 2023, when the intended sample size was nearly reached. According to

Figure 4, 46 patients were eligible, and 41 patients were randomized. One patient was excluded from the analysis due to a change of indication after randomization. One patient in the control group requested a block after 3 hours. This patient remained in the control group. 19 patients were available for analysis in the block group and 21 patients were available for analysis in the control group.

Patients had an ASA physical status between 1 and 3, were aged between 18 and 71 years, and were predominately male. There were no significant differences in patient demographics and clinical characteristics between the groups (

Table 1).

Pain Relief

In all patients a pain assessment was performed at all planned time points. The individual pain courses are depicted in Supplemental

Figure S1 in the online supplemental material. In the block group, often an early distinct decline could be observed, whereas in the control group many patients remained at their initial pain level for a longer period.

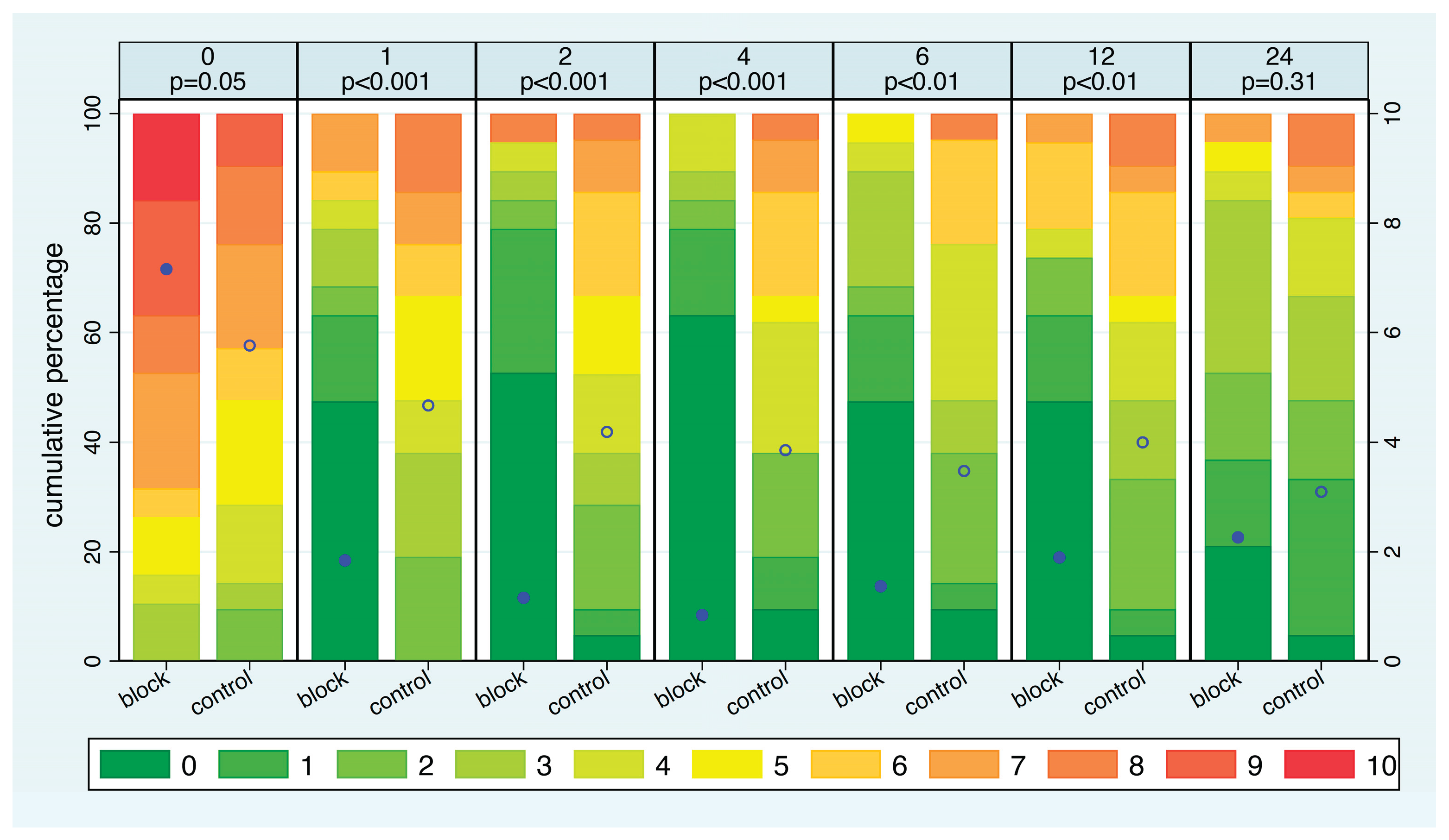

Considering the distribution of pain intensity at each time point (

Figure 5), NRS ratings at admission were slightly higher in the SCLN block group compared to the control group (p=0.05). In the SCLN block group, the average pain intensity significantly decreased within just one hour and continued to decline gradually until the fourth hour. In contrast, in the control group, the average pain intensity decreased very slowly over time. In the block group, the average pain intensity increased slowly after 4 hours but remained lower than that of the control group up. The difference in pain intensity was significant at all time points except after 24 hours. With respect to the distribution of the pain intensity, after 1 hour, 68% of patients in the SCLN group reported an NRS of 0-2, compared to 19% in the control group. Furthermore, at any time point between one hour and twelve hours, more than 40% of patients in the block group reported an NRS score of 0. In contrast, more than 40% of patients in the control group reported an NRS score of 5 or higher at 1, 2, and 4 hours. Half of all patients in the block group had six hours free of pain, whereas this never happened in the control group. Additionally, nearly 80% of patients in the block group experienced a maximum pain level of 3 or lower for at least 8 hours, compared to only one-third of patients in the control group.

The median time from signing the consent until requiring pain medication was 0.7 hours in the control group and 9.1 hours in the block group. 54% of patients in the control group required pain medication within 1 hour, whereas this was the case in only one patient in the block group.

Patient’s Experience

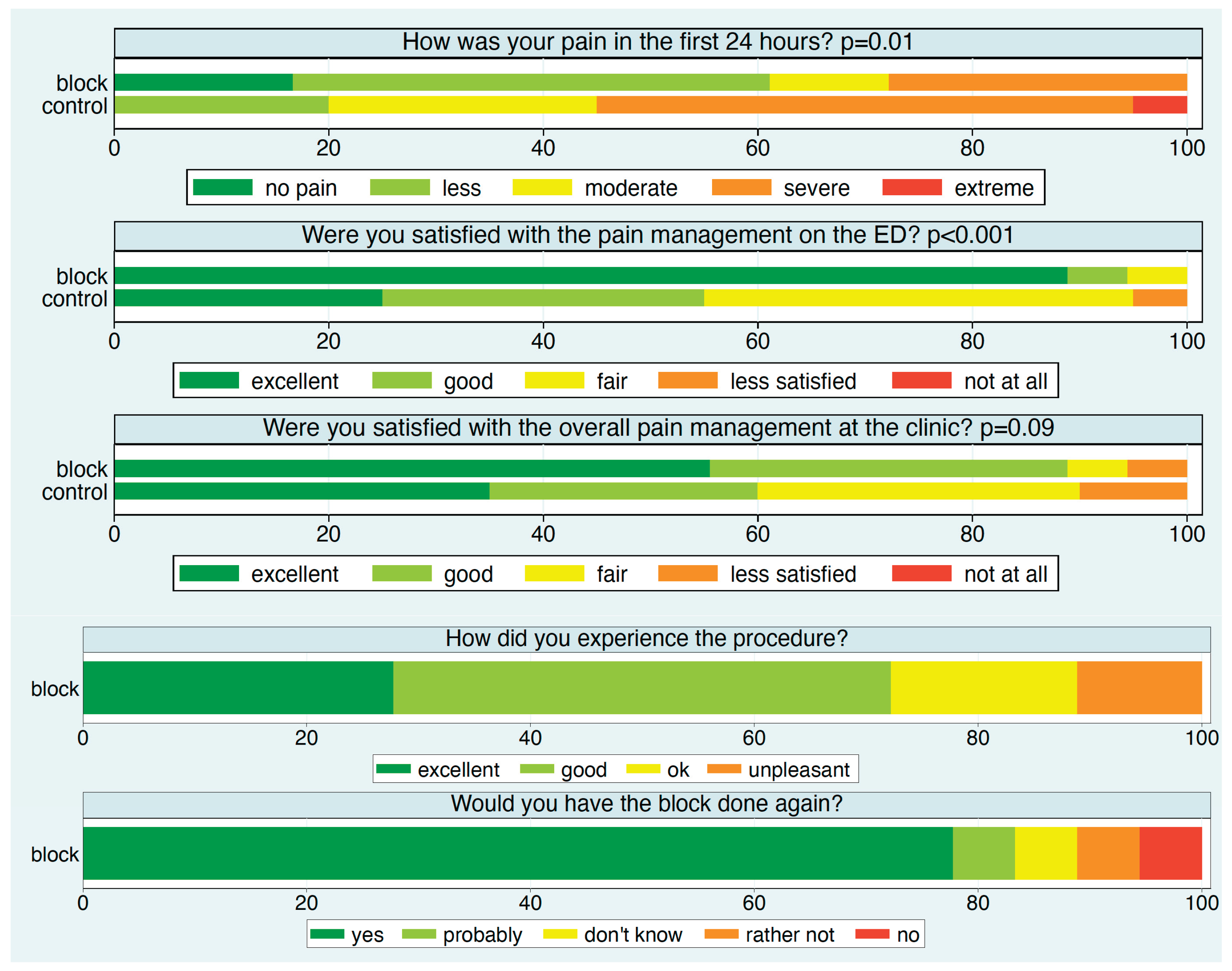

Except for two patients—one in each group—all participants reported their experience after 24 hours (

Figure 6). Approximately 90% of patients in the block group rated their satisfaction with pain management in the ED as excellent, compared to about 25% in the control group. Specifically, over 60% of patients in the block group reported no or minimal pain, compared to 20% in the control group.

Satisfaction with overall pain management in the hospital was also higher in the block group. In this group, about 75% of patients rated the block procedure as excellent or good, and nearly 80% would choose the block again.

Pain Medication

Table 3 shows the frequency and dosage of all types of pain medication administered. A clear trend is evident towards less frequent use of pain medication and lower doses in the block group compared to the control group with the exception of oxycodone. Ketorolac and fentanyl has been given in some patients deviating from the intended pain management reflecting the need for additional management options in some patients. A post-hoc check of the use of oxycodone indicated an occasional preference in order to support the sleep of patients.

Adverse Reactions and Adverse Events

In both groups patients did not report any adverse events related to the pain medication. Four patients in the block group reported adverse reactions indicating a block in the area of the GAN or TCN. Two of these patients had received an intermediate CPB, the two others had received LA doses of 4 and 5ml, respectively. In three patients the sensation was classified as mild. The fourth patient felt bothered by temporary numbness of the ear on the affected side.

Impact on Patient Management

Surgery was performed within 24 hours in 13 of the 19 patients (68%) in the block group, compared to 11 of the 21 patients (57%) in the control group. Patients were discharged home within 24h more often in the control group (2/19 vs 11/21).

4. Discussion

This is the first randomized controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of a selective SCLN block for pain relief during the initial treatment of acute CF. Our findings demonstrate that an ultrasound-guided selective block of the SCLN rapidly decreased initial pain to a substantial degree without causing major side effects. This effect was most distinct within the first 12 hours, and it resulted in significantly fewer early requests for pain medication. Previous RA trials have primarily focused on surgical anesthesia rather than analgesia for the initial non-operative treatment in the ED [

12]. Effective pain relief, however, is crucial during this initial treatment phase, which includes diagnostics, reduction of dislocation, and immobilization, such as using a sling. Initial pain intensity can range from moderate to severe and may even be unresponsive to opioids [

19]. For surgical anesthesia, it is necessary to block branches of both the brachial (pectoral nerves, subclavius nerve) and cervical plexuses (supraclavicular nerves) to achieve complete analgesia of the surgical site. This is due to the complex innervation of the clavicle by both plexuses [

8,

9]. Therefore, numerous techniques have been reported that combine different approaches, such as ISB, CPB, or fascia plane blocks. While these RA techniques are effective in pain control, they may also have significant side effects and complications, particularly if an ISB is applied [

20]. In contrast to ISB, which often results in unintended PN blocks[

13], intermediate CPB with higher volumes of LA can provide good analgesia without blocking the PN [

21]. We demonstrated that the topography of the SCLN allows for a selective block under ultrasound guidance. The SCLN, which mainly emerges from the 4th ventral ramus of the spinal nerve alongside the PN, can be visualized as it courses beneath the PVF. It then passes through the fascia in contrast to the PN, which remains underneath the PVF[

14]. After piercing the PVF, the branching pattern of the SCLN (medial, intermediate, and lateral branches) within the interfascial space can also be depicted. However, due to the high variability of this branching pattern, the SCLN was not clearly identified in two patients with challenging ultrasound conditions. In the interfascial space, the SCLN branches share the same compartment as other sensory branches of the cervical plexus, such as the GAN, TCN, and LON, which mainly derive from C2 and C3. This explains why these branches may additionally be blocked by uncontrolled LA spread during an SCLN block. This happened in 2 patients in this study.

Nevertheless, although clinically often not relevant, PN involvement has been recently described even with intermediate cervical plexus blocks [

22]. In that study 10ml of LA was used, suggesting a possible effect by diffusion. We strictly tried to avoid PN block which could be detrimental in patients with pre-existing pulmonary disease [

20]. This was approached by accurate injection above the PVF and a low LA dose. Regularly LA volumes up to 10ml are used for clavicle surgery [

10,

23]. Higher volumes are usually used for RA for carotid artery surgery [

22,

24] but seem to be unnecessary high for pain relief in acute CF. In distinct blocks, even lower volumes of less than 1ml have been shown to provide adequate peripheral nerve blocks [

25]. Since we could not foresee the spread pattern within the interfascial space we intended to inject a LA volume of 3 ml close to the SCLN. The actual dose given was often somewhat higher. This may explain the unintended block of branches of the cervical plexus (GAN, TCN) in 2 patients. Despite this was not a serious complication, it affected patient comfort and caused uncertainty. The two patients receiving an intermediate CPB experienced no effective pain control with pain levels of 4 and 7 after 2 hours. This indicated that they did not achieve a sufficient SCLN block, highlighting the uncontrollability of LA spread within the interfascial space, which is filled with fat and connective tissue. It remains speculative whether a higher LA volume would have successfully blocked the SCLN as well. As anticipated, ultrasound-guided RA of the SCLN proved to be an effective method for reducing pain intensity in the initial treatment of patients with acute CF, significantly enhancing patient satisfaction. Patients in the block group frequently experienced a maximum pain level of 3 on the NRS during the first 12 hours, whereas this low level of pain was rarely achieved in the control group. The frequent use of a higher LA dose than specified in the protocol may partially reflect the prior skin injection, which was not documented separately. However, it may also reflect a certain level of skepticism among ED physicians regarding the efficacy of a lower dose. The frequent decision to keep patients in the hospital after receiving a block may also reflect some concern about the SCLN block which turned out to be justified to some degree due to a loss in efficacy over time. It remains to be investigated whether strict compliance to a dose of 3ml will reduce the frequency of adverse reactions without lowering the efficacy in pain management. Fortunately, this question can be addressed in observational studies. In case of failure to clearly identify the passage of the SCLN through the PVB, there is still a need to optimize management. Similarly, it has to be discussed how to handle the loss of efficacy over time.

Several limitations of the study should be noted. Reliable information on pre-admission pain management could not be obtained. Blocks were not administered at the same time point after admission due to varying workloads in the ED. This could have influenced initial NRS scores. Our focus was on the clinical effects of the SCLN block, rather than a detailed mapping of the sensory distribution. Due to the anatomical proximity of the C5 and C6 nerve roots, diffusion of LA into the brachial plexus territory cannot be entirely excluded—even with the low volume of LA used—making it difficult to confirm that a truly selective block of the SCLN was achieved. Furthermore, while we conducted clinical assessments to evaluate phrenic nerve (PN) involvement, we did not perform functional or ultrasound measurements to fully exclude its involvement. We did not measure the onset time which we expected from prior observations to be less than 5 min. This expectation is in accordance with other reports [

23]. We used clonidine as an adjuvant to the LA, however the efficacy remains controversial. Some trials report a prolongation in the duration of nerve block [

26,

27,

28] whereas others do not [

16,

29,

30]. A pragmatic approach was used with respect to pain medication in the sense that pain medication was only under control of the study as long as patients stayed at the ED. Consequently, the frequency of rescue medication could not be compared in a meaningful manner between the two interventions. Patients in the block group were rarely discharged home which exposed them more frequently to a hospital-based management including the use of oxycodone to support sleep.

5. Conclusions

Ultrasound guided blocking of supraclavicular nerves is a highly effective approach to reduce pain intensity and improve patient satisfaction in patients suffering from clavicular fractures in an emergency department. Patients have to be informed about the risk of side effects in an adequate manner and the risk may be reduced by strict dose control.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S., M.U.G., W.V., M.R. and R.J.L.; methodology, E.S., M.U.G., W.V., M.R. and R.J.L.; validation, E.S., M.U.G., M.R R.J.L. and W.V.; formal analysis, E.S., M.U.G., W.V., M.R. and R.J.L.; investigation, E.S., W.V. and M.R..; resources, E.S., W.V. R.J.L. and M.R..; data curation, E.S., M.U.G., W.V. M.R. and R.J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S., M.U.G., W.V., R.J.L. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, E.S., M.U.G., W.V., M.R. and R.J.L.; visualization, E.S., W.V., M.U.G., R.J.L. and M.R..; supervision, E.S., M.U.G. W.V.and R.J.L.; project administration, E.S., M.U.G., W.V. and R.J.L.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approval by the Ethics Committee of Northwestern Switzerland (Ethikkommission Nordwestschweiz, reference number BASEC2020-03054).

Informed Consent Statement

All patients gave oral and written informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the authors on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RA |

Regional anesthesia |

| SCLN |

Supraclavicular nerve |

| PN |

Phrenic nerve |

| GAN |

Great auricular nerve |

| TCN |

Transverse cervical nerve |

| LON |

Lesser occipital nerve |

| SCM |

Sternocleidomastoid muscle |

| SCF |

Superficial cervical fascia |

| PVF |

Prevertebral fascia |

| mSM |

Middle scalene muscle |

| aSM |

anterior scalene muscle |

| minSM |

Scalenus minimus muscle |

| RvC5 |

Ventral ramus of the 5th spinal nerve |

| CF |

Clavicle fracture |

| ED |

Emergency department |

| NRS |

Numeric rating scale |

| ASA |

American Society of Anesthesiologists |

References

- Ullah K, Khan S, Wang Y, Zhao Z, Cheng P, Sapkota B, et al. Bilaterally Threaded, Minimal Invasive, Elastic Locking Intramedullary Nailing (ELIN) for the Treatment of Clavicle Fractures. Orthopaedic Surgery. 2020; 12: 321–32. [CrossRef]

- Rupp M, Walter N, Pfeifer C, Lang S, Kerschbaum M, Krutsch W, et al. The incidence of fractures among the adult population of Germany. Deutsches Ärzteblatt international [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Jul 23]; Available from: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0238. [CrossRef]

- Lindsey MH, Grisdela P, Lu L, Zhang D, Earp B. What Are the Functional Outcomes and Pain Scores after Medial Clavicle Fracture Treatment? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021; 479: 2400–7. [CrossRef]

- Kim D-W, Kim D-H, Kim B-S, Cho C-H. Current Concepts for Classification and Treatment of Distal Clavicle Fractures. Clin Orthop Surg. 2020; 12: 135. [CrossRef]

- Yoo J-S, Heo K, Kwon S-M, Lee D-H, Seo J-B. Effect of Surgical-Site, Multimodal Drug Injection on Pain and Stress Biomarkers in Patients Undergoing Plate Fixation for Clavicular Fractures. Clin Orthop Surg. 2018; 10: 455. [CrossRef]

- Joshi GP. Multimodal Analgesia Techniques and Postoperative Rehabilitation. Anesthesiology Clinics of North America. 2005; 23: 185–202. [CrossRef]

- Phillips DM. JCAHO Pain Management Standards Are Unveiled. JAMA. 2000; 284: 428. [CrossRef]

- Leurcharusmee P, Maikong N, Kantakam P, Navic P, Mahakkanukrauh P, Tran DQ. Innervation of the clavicle: a cadaveric investigation. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2021; 46: 1076–9. [CrossRef]

- Tran DQH, Tiyaprasertkul W, González AP. Analgesia for Clavicular Fracture and Surgery: A Call for Evidence. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 2013; 38: 539–43. [CrossRef]

- Abdelghany MS, Ahmed SA, Afandy ME. Superficial cervical plexus block alone or combined with interscalene brachial plexus block in surgery for clavicle fractures: a randomized clinical trial. Minerva Anestesiol. 2021; 87. Available from: https://www.minervamedica.it/index2.php?show=R02Y2021N05A0523. [CrossRef]

- Reverdy F. Combined interscalene-superficial cervical plexus block for clavicle surgery: an easy technique to avoid general anesthesia. BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2024 Jul 23]; 115. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/bja/article/2451503/Combined. [CrossRef]

- Lee CCM, Beh ZY, Lua CB, Peng K, Fathil SM, Hou J-D, et al. Regional Anesthetic and Analgesic Techniques for Clavicle Fractures and Clavicle Surgeries: Part 1—A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2022; 10: 1487. [CrossRef]

- Tran DQH, Elgueta MF, Aliste J, Finlayson RJ. Diaphragm-Sparing Nerve Blocks for Shoulder Surgery: Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 2017; 42: 32–8. [CrossRef]

- Litz, R; Avila Gonzalez, C; Feigl, G. Cervical Plexus Block. Karmakar, MJ editors(s) Musculoskeletal Ultrasound for Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Medicine. 2nd Edition. Hong Kong: Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care; 2016. p. 253–65.

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010; 152: 726–32. [CrossRef]

- Erlacher W, Schuschnig C, Koinig H, Marhofer P, Melischek M, Mayer N, et al. Clonidine as adjuvant for mepivacaine, ropivacaine and bupivacaine in axillary, perivascular brachial plexus block. Can J Anesth. 2001; 48: 522–5. [CrossRef]

- Allman FL. Fractures and ligamentous injuries of the clavicle and its articulation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967; 49: 774–84.

- O’Neill BJ, Hirpara KM, O’Briain D, McGarr C, Kaar TK. Clavicle fractures: a comparison of five classification systems and their relationship to treatment outcomes. International Orthopaedics (SICOT). 2011; 35: 909–14. [CrossRef]

- Herring AA, Stone MB, Frenkel O, Chipman A, Nagdev AD. The ultrasound-guided superficial cervical plexus block for anesthesia and analgesia in emergency care settings. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2012; 30: 1263–7. [CrossRef]

- Divella M, Vetrugno L. Regional blocks for clavicle fractures: keep Hippocrates in mind. Minerva Anestesiol. 2021; 87. Available from: https://www.minervamedica.it/index2.php?show=R02Y2021N05A0499. [CrossRef]

- Kim HY, Soh EY, Lee J, Kwon SH, Hur M, Min S-K, et al. Incidence of hemi-diaphragmatic paresis after ultrasound-guided intermediate cervical plexus block: a prospective observational study. J Anesth. 2020; 34: 483–90. [CrossRef]

- Opperer M, Kaufmann R, Meissnitzer M, Enzmann FK, Dinges C, Hitzl W, et al. Depth of cervical plexus block and phrenic nerve blockade: a randomized trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022; 47: 205–11. [CrossRef]

- Arjun BK, Vinod CN, Puneeth J, Narendrababu MC. Ultrasound-guided interscalene block combined with intermediate or superficial cervical plexus block for clavicle surgery: A randomised double blind study. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2020; 37: 979–83. [CrossRef]

- Petrucci E. Intermediate Cervical Plexus Block in theManagement of Persistent Postoperative PainPost Carotid Endarterectomy: A Prospective,Randomized, Controlled, Clinical Trial. Pain Phys. 2020; 23: 237–44. [CrossRef]

- Eichenberger U, Stöckli S, Marhofer P, Huber G, Willimann P, Kettner SC, et al. Minimal Local Anesthetic Volume for Peripheral Nerve Block: A New Ultrasound-Guided, Nerve Dimension-Based Method. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 2009; 34: 242–6. [CrossRef]

- Ali Q, Manjunatha L, Amir S, Jamil S, Quadir A. Efficacy of clonidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine in supraclavicular brachial plexus block: A prospective study. Indian J Anaesth. 2014; 58: 709. [CrossRef]

- Patil K, Singh N. Clonidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine-induced supraclavicular brachial plexus block for upper limb surgeries. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2015; 31: 365. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia R, Payal Y, Khurana G. Addition of clonidine or lignocaine to ropivacaine for supraclavicular brachial plexus block: a comparative study. smedj. 2014; 55. Available from: http://www.smj.org.sg/article/addition-clonidine-or-lignocaine-ropivacaine-supraclavicular-brachial-plexus-block. [CrossRef]

- Beaussier M, Weickmans H, Abdelhalim Z, Lienhart A. Inguinal Herniorrhaphy Under Monitored Anesthesia Care with Ilioinguinal-Iliohypogastric Block: The Impact of Adding Clonidine to Ropivacaine: Anesth Analg. 2005; 1659–62. [CrossRef]

- Helayel PE, Kroth L, Boos GL, Jahns MT, Oliveira Filho GRD. Efeitos da clonidina por via muscular e perineural no bloqueio do nervo isquiático com ropivacaína a 0,5%. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2005; 55. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-70942005000500002&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pt. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Typical double dot of the GAN (white arrows) after its loop around the lateral border of the SCM. The GAN is already located over the PVF. At this sonographic cross-section, the SCLN (dotted white circle) has not yet pierced the PVF completely and lies as a grape-like structure over the middle scalene muscle (mSM). The ventral ramus of the 5th spinal nerve (RvC5) lies ventrally of the mSM.

Figure 1.

Typical double dot of the GAN (white arrows) after its loop around the lateral border of the SCM. The GAN is already located over the PVF. At this sonographic cross-section, the SCLN (dotted white circle) has not yet pierced the PVF completely and lies as a grape-like structure over the middle scalene muscle (mSM). The ventral ramus of the 5th spinal nerve (RvC5) lies ventrally of the mSM.

Figure 2.

After perforating the PVF, the SCLN divides into three bundles (three white arrows), while the PN (single white arrow) remains beneath the PVF, coursing around the anterior scalene muscle (aSM). C5 and C6 represent the ventral rami of their respective spinal nerves, in this patient separated by the scalenus minimus muscle (minSM). mSM: middle scalene muscle; SCM: sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Figure 2.

After perforating the PVF, the SCLN divides into three bundles (three white arrows), while the PN (single white arrow) remains beneath the PVF, coursing around the anterior scalene muscle (aSM). C5 and C6 represent the ventral rami of their respective spinal nerves, in this patient separated by the scalenus minimus muscle (minSM). mSM: middle scalene muscle; SCM: sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Figure 3.

Injection of the local anesthetic (LA) using the in-plane technique around the supraclavicular nerves (SCLN, dotted white circle) strictly over the prevertebral fascia (PVF, upward white arrows). The injection needle (downward gray arrows) is advanced laterally between the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) and the PVF. At this point, the SCLN has already pierced the PVF, so the underlying ventral rami of the spinal nerves C5 and C6 are spared from the LA. Anterior scalene muscle: aSM, middle scalene muscle: mSM.

Figure 3.

Injection of the local anesthetic (LA) using the in-plane technique around the supraclavicular nerves (SCLN, dotted white circle) strictly over the prevertebral fascia (PVF, upward white arrows). The injection needle (downward gray arrows) is advanced laterally between the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) and the PVF. At this point, the SCLN has already pierced the PVF, so the underlying ventral rami of the spinal nerves C5 and C6 are spared from the LA. Anterior scalene muscle: aSM, middle scalene muscle: mSM.

Figure 4.

CONSORT study flow chart. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Figure 4.

CONSORT study flow chart. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Figure 5.

The distribution of pain intensity at each time point, stratified by intervention group. The eleven possible pain levels are represented by different colors from green to red. The mean pain intensity at each time point is shown as a blue dot, which refers to the NRS on the right y-axis. p-values refer to a comparison of the two intervention groups. Filled dot: block group. Open dot: control group.

Figure 5.

The distribution of pain intensity at each time point, stratified by intervention group. The eleven possible pain levels are represented by different colors from green to red. The mean pain intensity at each time point is shown as a blue dot, which refers to the NRS on the right y-axis. p-values refer to a comparison of the two intervention groups. Filled dot: block group. Open dot: control group.

Figure 6.

The distribution of the patient experience measures at each time point stratified by intervention group. p-values refer to a comparison of the two intervention groups.

Figure 6.

The distribution of the patient experience measures at each time point stratified by intervention group. p-values refer to a comparison of the two intervention groups.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and classification of fractures. Data are presented as mean (range), or numbers (percentage) if applicable.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and classification of fractures. Data are presented as mean (range), or numbers (percentage) if applicable.

| |

Block (n=19) |

Control (n=21) |

p-value |

| Age (years) |

40 (18-70) |

43 (18-67) |

0.56 |

| Female/male |

1 (5%)/18(94.7%) |

2 (9.5%)/19(90.5%) |

1.00 |

| ASA |

1.5 (1-3) |

1.5 (1-3) |

1.00 |

| BMI |

24.2 (19.4-30.4) |

24.3 (19.5-33.9) |

1.00 |

| Type of accident |

|

|

0.42 |

| Bicycle |

14 (73.7%) |

14 (66.7%) |

|

| Sports |

2 (10.5%) |

6 (28.6%) |

|

| Fall of other cause |

2 (10.5%) |

1 (4.8%) |

|

| Direct blow |

1 (5.3%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

| Fracture location |

|

|

0.33 |

| Lateral third |

5 (26.3%) |

3 (14.3%) |

|

| Middle third |

13 (68.4%) |

18 (85.7%) |

|

| Medial third |

1 (5.3%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

| Dislocation |

|

|

1.00 |

| < 5 mm |

1 (5.3%) |

2 (9.5%) |

|

| > 5mm |

18 (94.7%) |

19 (90.5%) |

|

Table 2.

Distribution of block characteristics in the block group (n=19).

Table 2.

Distribution of block characteristics in the block group (n=19).

| Type of block |

| Supraclavicular Nerves block |

17 (89.5%) |

| Intermediate cervical plexus block |

2 (10.5%) |

| Local anesthetic |

| Bupivacain 0.5% + Clonidin |

17 (89.5%) |

| Ropivacain 1% + Clonidin |

1 (5.3%) |

| Ropivacain 0.75% |

1 (5.3%) |

| Dose of local anesthetic |

| 3 ml |

5 (26.3%) |

| 3.5 ml |

1 (5.3%) |

| 4 ml |

12 (63.2%) |

| 5 ml |

1 (5.3%) |

Table 3.

The frequency and dosage of all pain medication given stratified by intervention group. The frequency refers to the number of patients receiving the specific medication. The dose refers to the cumulative dose given over 24 hours after admission. For the dose, mean and range are reported.

Table 3.

The frequency and dosage of all pain medication given stratified by intervention group. The frequency refers to the number of patients receiving the specific medication. The dose refers to the cumulative dose given over 24 hours after admission. For the dose, mean and range are reported.

| |

block |

control |

| Sample size, n |

19 |

21 |

| Metamizole - iv |

| given |

2 (10.5%) |

5 (23.8%) |

| dose (mg) |

1750 (500-3000) |

2214 (1000-4000) |

| Ketorolac - iv |

| given |

0 (0.0%) |

3 (14.3%) |

| dose (mg) |

.(.-.) |

30(30-30) |

| Paracetamol - iv |

| given |

3 (15.8%) |

3 (14.3%) |

| dose (mg) |

1333(1000-2000) |

2000(1000-4000) |

| Ibuprofen – per os |

| given |

12 (63.2%) |

18 (85.7%) |

| dose (mg) |

633(400-2000) |

1156(400-2200) |

| Metamizole - per os |

| given |

4 (21.1%) |

15 (71.4%) |

| dose (mg) |

2000(1000-3000) |

2607(500-5000) |

| Paracetamol - per os |

| given |

1 (5.3%) |

3 (14.3%) |

| dose (mg) |

1000(1000-1000) |

1500(1000-2000) |

| Oxycodone - per os |

| given |

7 (36.8%) |

6 (28.6%) |

| dose (mg) |

18(7-35) |

22(7-40) |

| Fentanyl - iv |

| given |

4 (21.1%) |

6 (28.6%) |

| dose (µg) |

162(50-300) |

200(50-350) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).