1. Introduction

Dysphagia—clinically defined as impaired deglutition [

1]—is designated by the WHO as a high-impact disorder contributing to excess morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs[

2]. Globally affecting 590 million individuals[

3], this underdiagnosed yet prevalent condition demonstrates progressive age-dependent incidence[

4], fulfilling diagnostic criteria for a geriatric syndrome with 10%-33% prevalence in elderly populations[

5] and 11%-60% among community-dwelling seniors[

6] . Primary etiologies include chronic neurological disorders—notably stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and dementia[

7]. Specifically, stroke patients exhibit dysphagia rates of 37%–78%[

8], while >80% of Alzheimer’s disease and 60%–80% of Parkinson’s disease cases develop swallowing impairment during disease progression[

9,

10]. Iatrogenic dysphagia occurs in 70%-80% of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients post-radiotherapy and 1%-79% following anterior cervical fusion[

11]. Crucially, multivariate analyses establish dysphagia as an independent mortality predictor[

12] that elevates risks for malnutrition, aspiration pneumonia, dehydration, doubled 6-month mortality[

13] ,1.7-fold increased mortality[

14], and long-term care institutionalization[

5]. This evidence base mandates implementation of standardized screening algorithms and early targeted interventions.

Anemia is an independent risk factor for decreased health-related quality of life in older individuals[

15]. It is associated with all-cause mortality[

16], as well as mortality due to CVD[

17,

18], cancer, and respiratory disease[

19]. Anemia frequently accompanies percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), correlating with reduced survival and serving as a metabolic distress indicator portending poor prognosis[

20]. Notably, it predicts 4-week mortality in PEG-dependent nutritional support patients[

21]. Post-stroke rehabilitation data further associate low baseline hemoglobin as a significant risk factor for sarcopenia, delayed functional recovery, and dysphagia progression[

22]. Optimal gastrointestinal management prioritizes symptom control while monitoring complications, particularly anemia and malabsorption[

23]. The prognostic role of hemoglobin concentrations in mortality risk stratification for geriatric dysphagia patients represents a significant and clinically relevant research gap, warranting further investigation given its potential utility as an accessible prognostic indicator.

Despite these clinical implications, standardized guidelines for geriatric dysphagia management remain inadequate. Early assessment is consequently essential for adverse outcome prognostication. Although hemoglobin demonstrates prognostic value across multiple pathologies, its relationship with mortality in dysphagia patients especially Japanese elderly is poorly defined. With mortality predictors in this population lacking consensus, this study specifically examined hemoglobin's independent correlation with mortality in Japanese geriatric patients with dysphagia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

The present study is a secondary analysis of a de-identified dataset deposited in the Dryad Digital Repository (Masaki S. et al., 2019; doi:10.5061/dryad.gg407h1)[

24]. The original study was conducted at Miyanomori Memorial Hospital and details of data collection, inclusion/exclusion criteria and primary ethical approvals are reported in the source publication. We accessed and analyzed the publicly available dataset in compliance with Dryad terms and the ethical framework described in the primary report. The present secondary analysis did not involve direct contact with human participants.

2.2. Study Design and Participants

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis at a single institution involving dysphagia patients aged ≥65 years who received percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) or total parenteral nutrition (TPN) from January 2014 to January 2017. Multidisciplinary clinical assessments (physicians, nurses, speech-language pathologists) combined with video fluoroscopy confirmed severe dysphagia in all cases. Exclusion criteria encompassed: 1) terminal malignancies; 2) PEG for gastric decompression; 3) PEG placement prior to January 2014. The Miyanomori Memorial Hospital Ethics Board approved this study and waived informed consent due to anonymized retrospective data.

2.3. Procedures

Nutritional support modality (PEG vs TPN) was determined through shared decision-making between clinicians and patients (or their family members). Appropriate nutrition was administered based on the clinical evaluations conducted by healthcare professionals. Clinical information, including age, sex, underlying diseases such as cerebrovascular diseases, severe dementia, aspiration pneumonia, ischemic heart disease (IHD), the presence of non-tunneled central venous catheters (NT.CVC), percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), oral intake recovery, and laboratory parameters were obtained from patients’ medical records. Hemoglobin values were measured ≤7 days before initiating nutritional interventions. The primary objective of this study was to assess mortality rates following the initiation of the procedure during the designated follow-up period. Participants were stratified into three groups (T1 <9 g/dL, T2 9–12 g/dL, T3 ≥12 g/dL), based on their hemoglobin at the time of enrollment.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Publicly available datasets enabled secondary analyses.

Baseline characteristics are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed continuous variables, median (interquartile range, IQR) for skewed continuous variables, and counts (percentages) for categorical variables. Between-group comparisons used one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, as appropriate. Survival time was defined as days from initiation of nutritional support (date of PEG insertion or start of TPN) to death or last follow-up. Hemoglobin (Hb) was analyzed both as a continuous variable (per 1 g/dL increase) and categorically by prespecified groups (T1: <9 g/dL; T2: 9–12 g/dL; T3: ≥12 g/dL). We fitted Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Model I was unadjusted; Model II adjusted for age and sex plus major comorbidities (cerebrovascular disease, severe dementia, aspiration pneumonia, ischemic heart disease); Model III additionally adjusted for markers of inflammation and treatment factors (CRP, NT-CVC, PORT, PICC, PEG, oral intake recovery and daily kcal). Subgroup analyses examined effect modification by prespecified variables using likelihood ratio tests for interaction; p-values for interaction are reported. Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank tests compared survival across Hb categories; median survival times with 95% CIs are reported. All tests were two-sided and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed in Free Statistics 2.2.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

The cohort comprised 253 patients (99 males, 154 females) with baseline characteristics detailed in

Table 1. Mean age was 83.1±9.3 years. Nutrition support included PEG (n=180) and TPN (n=73). Significant intergroup differences (

P<0.05) emerged for age, ischemic heart disease, PEG utilization, NT-CVC presence, CRP levels, and hemoglobin concentrations.

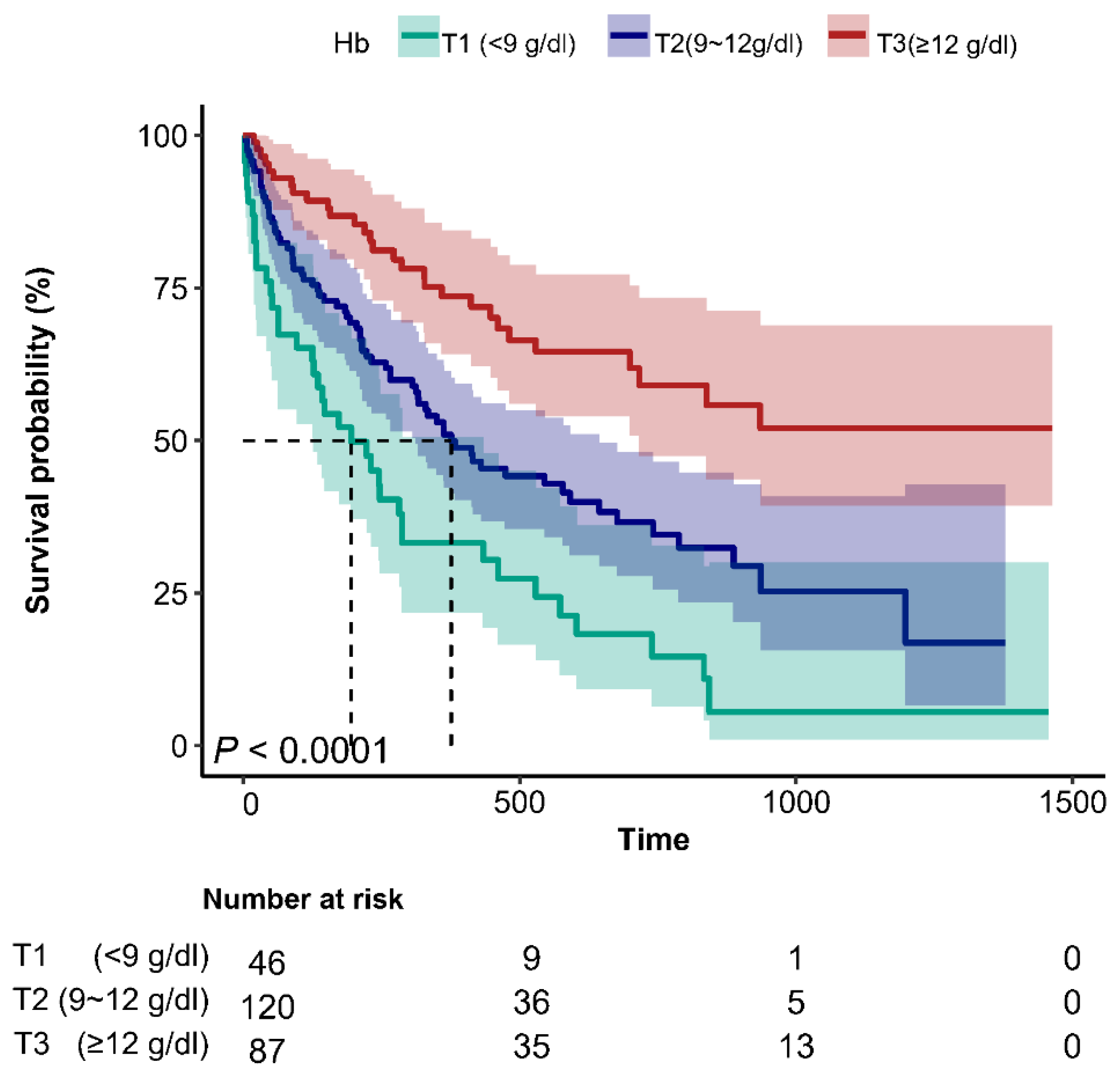

3.2. Kaplan–Meier Curve

Figure 1 displays Kaplan-Meier survival curves. T2 and T3 cohorts exhibited substantially prolonged median survival versus T1 (309 and 405 days vs. 185 days; log-rank

P<0.001).

3.3. Association Between Hemoglobin and Mortality in Various Models

Table 2 illustrates the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% Cl) associated with the risk of mortality in patients with dysphagia based on hemoglobin. There are four models for hemoglobin as continuous and categorical variables. No variables to be chosen to adjust in model I. Variables of demographics (age, sex) and past medical history (cerebrovascular diseases, severe dementia, aspiration pneumonia, IHD) were chosen to adjust in model II. All the variables that we included (age, sex, cerebrovascular diseases, severe dementia, aspiration pneumonia, IHD, C-reactive protein, non-tunneled central venous catheters, implantable central venous ports, peripherally inserted central catheters, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, oral intake recovery and Kcal/day) to be adjusted in model III. The results of these models were shown in

Table 2. The risk of mortality exhibited an upward trend as hemoglobin increased in the univariable Cox regression analysis (HR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.71-0.84,

P < 0.001). Upon adjusting for all covariates in the multivariable Cox regression analysis, the HR was 0.83 (95% CI: 0.76-0.91,

P < 0.001). When compared to the lowest hemoglobin group (T1 < 9g/dL), the adjusted HR values for hemoglobin and mortality in the T2 (9-12 g/dL) and T3 (≥ 12 g/dL) groups were 0.62(95% CI: 0.41-0.93,

P < 0.05) and 0.36 (95% CI: 0.21-0.6,

P for trend < 0.001), respectively.

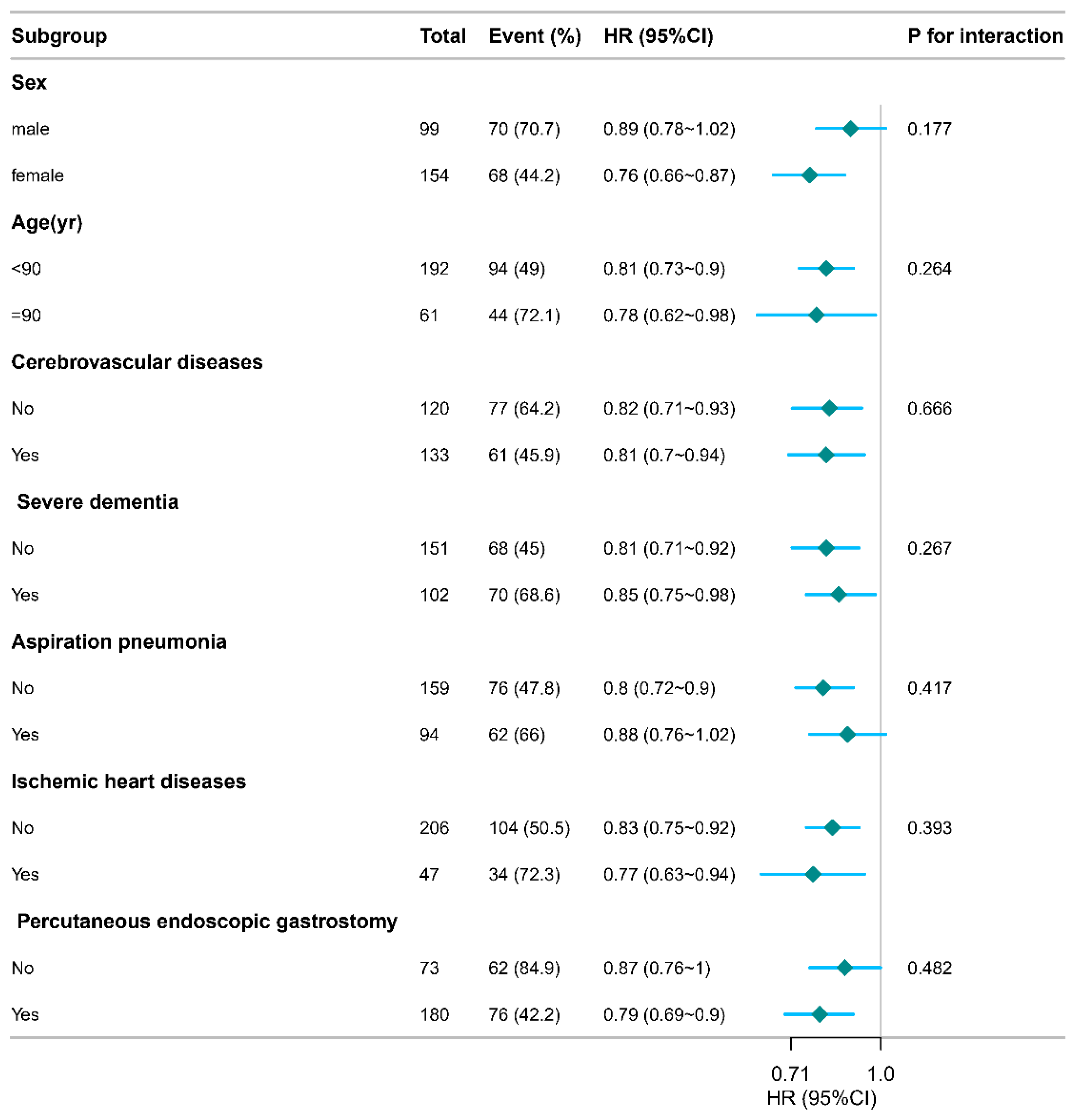

3.4. Subgroup Analyses

Figure 2 presents interaction analyses after comprehensive adjustment for: age, sex, IHD, cerebrovascular disorders, severe dementia, aspiration pneumonia, PEG, CRP, PORT, NT-CVC, PICC, daily caloric intake, and oral recovery status. No significant interactions emerged across seven subgroups, confirming result robustness.

4. Discussion

This investigation demonstrates hemoglobin concentration independently predicts reduced mortality risk in dysphagia patients. Specifically, when treating hemoglobin as a continuous variable, unadjusted models revealed a substantial hemoglobin-mortality correlation in dysphagia patients (HR=0.77, 95% CI: 0.71-0.84, P<0.001), which persisted after full covariate adjustment (adjusted HR=0.83, 95% CI: 0.76-0.91 , P<0.001). Categorical analysis confirmed progressively lower mortality with higher hemoglobin tertiles. Multivariable-adjusted models showed progressive risk reduction of 38% (T2 vs T1) and 64% (T3 vs T1) for all-cause mortality (P<0.05), confirming hemoglobin-dependent mortality protection..

Older adults with dysphagia exhibit increased mortality that is closely driven by malnutrition and its sequelae. This vulnerable group is predisposed to serious comorbid events: stroke-related dysphagia markedly elevates the risk of aspiration pneumonia[

8] and nutritional decline[

14], and patients demonstrate higher rates of transfer to post–acute care[

25], impaired physical function[

14,

26] , prolonged hospital stays, and excess mortality. Extended hospitalization and independent mortality prediction further characterize this condition. Anemia is frequent in PEG-patients, mostly with the features of ACD or multifactorial. It is associated with poorer survival, acting as a biomarker of severe metabolic distress and adverse prognosis[

27]. These interrelated deficits (malnutrition, sarcopenia, anemia) likely amplify infection risk, reduce functional reserve, and contribute to mortality. Accordingly, dysphagia in older adults requires systematic intervention: early nutritional screening, routine monitoring for anemia and other complications, timely initiation of targeted nutritional and rehabilitation strategies, and multidisciplinary care pathways to mitigate downstream morbidity and mortality[

28].

This study identified hemoglobin concentration as an independent, inverse predictor of mortality in patients with dysphagia [

29] , supporting its role as a pragmatic prognostic marker in clinical practice. Prioritizing improvement of nutritional status is therefore essential to reduce mortality in this vulnerable population. Routine hemoglobin surveillance can facilitate early recognition of clinical deterioration and trigger timely interventions (nutritional optimization, diagnostic evaluation for causes of anemia, or targeted rehabilitation). With global population aging and increasing dysphagia incidence after stroke[

30,

31] and certain orthopedic procedures (hip fracture[

32] , anterior cervical fusion[

33],hemoglobin measurement—readily available, low-cost, and routinely performed—offers a scalable, cost-effective element for mortality risk stratification. These results provide clinicians with an evidence base to integrate hemoglobin monitoring into dysphagia care pathways and justify prospective studies to validate its utility for guiding treatment and improving outcomes.

Nevertheless, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the study was conducted at a single center in Japan and was retrospective, potentially compromising its accuracy compared to more robust multicenter prospective studies from different countries. Second, we must recognize the potential presence of selection bias in our study due to the reliance on a solitary measurement of hemoglobin within a 7-day timeframe upon hospitalization without subsequent follow-up measurements. Consequently, the potential effect of hemoglobin levels at varying time intervals on the desired outcomes was precluded. Third, as a secondary analysis of publicly available data, the investigators could not influence study design, data collection, variable definitions. Together, these limitations underscore the need for prospective, multicenter studies with repeated hemoglobin measurements and standardized data collection to validate and extend the present findings.

5. Conclusion

Hemoglobin concentration independently predicts reduced mortality risk in elderly Japanese patients with dysphagia. Subgroup analyses demonstrated no significant interaction effects, confirming the association was robust across the clinical subgroups examined. Taken together, these findings support the potential utility of hemoglobin as a low-cost prognostic biomarker in the management of geriatric dysphagia.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org

Author Contributions

PY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. JYX: Writing – review & editing. XLG: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Planning Project (Grant No. 2023B110009).

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available in the Dryad repository, doi:10.5061/dryad.gg407h1. The original data collection and ethical approvals are described in the primary publication. We performed de-identified secondary analyses in accordance with Dryad terms.

Ethics Statement

The original study was approved by the Miyanomori Memorial Hospital Ethics Board and written informed consent was obtained from participants as reported in the source publication. This secondary analysis of de-identified, publicly available data was reviewed and exempted from further ethical approval.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shigenori Masaki and Takashi Kawamoto for the original data collection and ethical approvals which are described in the primary publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- McCarty, E.B.; Chao, T.N. Dysphagia and Swallowing Disorders. Med Clin North Am 2021, 105, 939–954. [CrossRef]

- Rommel, N.; Hamdy, S. Oropharyngeal Dysphagia: Manifestations and Diagnosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016, 13, 49–59. [CrossRef]

- Nakao-Kato, M.; Rathore, F.A. An Overview Of The Management And Rehabilitation Of Dysphagia. J Pak Med Assoc 2023, 73, 1749–1752. [CrossRef]

- Hurtte, E.; Young, J.; Gyawali, C.P. Dysphagia. Prim Care 2023, 50, 325–338. [CrossRef]

- Thiyagalingam, S.; Kulinski, A.E.; Thorsteinsdottir, B.; Shindelar, K.L.; Takahashi, P.Y. Dysphagia in Older Adults. Mayo Clin Proc 2021, 96, 488–497. [CrossRef]

- Di Pede, C.; Mantovani, M.E.; Del Felice, A.; Masiero, S. Dysphagia in the Elderly: Focus on Rehabilitation Strategies. Aging Clin Exp Res 2016, 28, 607–617. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.M.; Codipilly, D.C.; Wilfahrt, R.P. Dysphagia: Evaluation and Collaborative Management. Am Fam Physician 2021, 103, 97–106.

- Martino, R.; Foley, N.; Bhogal, S.; Diamant, N.; Speechley, M.; Teasell, R. Dysphagia After Stroke: Incidence, Diagnosis, and Pulmonary Complications. Stroke 2005, 36, 2756–2763. [CrossRef]

- Suttrup, I.; Warnecke, T. Dysphagia in Parkinson’s Disease. Dysphagia 2016, 31, 24–32. [CrossRef]

- Clavé, P.; Shaker, R. Dysphagia: Current Reality and Scope of the Problem. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015, 12, 259–270. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zheng, P.; Chen, S.; Wei, L.; Fu, X.; Fu, Y.; Hu, T.; Chen, S. Association between the C-Reactive Protein/Albumin Ratio and Mortality in Older Japanese Patients with Dysphagia. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1370763. [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, S.H.; Rosenvinge, P.M.; Modlinski, R.M.; Olesen, M.D.; Rasmussen, H.H.; Holst, M. Signs of Dysphagia and Associated Outcomes Regarding Mortality, Length of Hospital Stay and Readmissions in Acute Geriatric Patients: Observational Prospective Study. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2021, 45, 412–419. [CrossRef]

- Wirth, R.; Pourhassan, M.; Streicher, M.; Hiesmayr, M.; Schindler, K.; Sieber, C.C.; Volkert, D. The Impact of Dysphagia on Mortality of Nursing Home Residents: Results From the nutritionDay Project. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018, 19, 775–778. [CrossRef]

- Tagliaferri, S.; Lauretani, F.; Pelá, G.; Meschi, T.; Maggio, M. The Risk of Dysphagia Is Associated with Malnutrition and Poor Functional Outcomes in a Large Population of Outpatient Older Individuals. Clin Nutr 2019, 38, 2684–2689. [CrossRef]

- Wouters, H.J.C.M.; van der Klauw, M.M.; de Witte, T.; Stauder, R.; Swinkels, D.W.; Wolffenbuttel, B.H.R.; Huls, G. Association of Anemia with Health-Related Quality of Life and Survival: A Large Population-Based Cohort Study. Haematologica 2019, 104, 468–476. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-M.; Li, L.-E.; Wang, C.-H.; Dou, Q.-L.; Yang, Y.-Z. The Association between Anemia and All-Cause Mortality among Chinese Older People: The Evidence from CHARLS. J Nutr Health Aging 2024, 28, 100281. [CrossRef]

- Cleland, J.G.F.; Zhang, J.; Pellicori, P.; Dicken, B.; Dierckx, R.; Shoaib, A.; Wong, K.; Rigby, A.; Goode, K.; Clark, A.L. Prevalence and Outcomes of Anemia and Hematinic Deficiencies in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol 2016, 1, 539–547. [CrossRef]

- Jhand, A.S.; Abusnina, W.; Tak, H.J.; Ahmed, A.; Ismayl, M.; Altin, S.E.; Sherwood, M.W.; Alexander, J.H.; Rao, S.V.; Abbott, J.D.; et al. Impact of Anemia on Outcomes and Resource Utilization in Patients with Myocardial Infarction: A National Database Analysis. Int J Cardiol 2024, 408, 132111. [CrossRef]

- Cannon, E.J.; Misialek, J.R.; Buckley, L.F.; Aboelsaad, I.A.F.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Leister, J.; Pankow, J.S.; Lutsey, P.L. Anemia, Iron Deficiency, and Cause-Specific Mortality: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Gerontology 2024, 70, 1023–1032. [CrossRef]

- Brito, M.; Laranjo, A.; Nunes, G.; Oliveira, C.; Santos, C.A.; Fonseca, J. Anemia and Hematopoietic Factor Deficiencies in Patients after Endoscopic Gastrostomy: A Nine-Year and 472-Patient Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3637. [CrossRef]

- Lima, D.L.; Miranda, L.E.C.; da Penha, M.R.C.; Lima, R.N.C.L.; Dos Santos, D.C.; Eufrânio, M.S.; Miranda, A.C.G.; Pereira, L.M.M.B. Factors Associated with 30-Day Mortality in Patients after Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy. JSLS 2021, 25, e2021.00040. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, Y.; Wakabayashi, H.; Nagano, F.; Bise, T.; Shimazu, S.; Shiraishi, A. Low Hemoglobin Levels Are Associated with Sarcopenia, Dysphagia, and Adverse Rehabilitation Outcomes After Stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2020, 29, 105405. [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, A. Current Management of the Gastrointestinal Complications of Systemic Sclerosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016, 13, 461–472. [CrossRef]

- Masaki, S.; Kawamoto, T. Comparison of Long-Term Outcomes between Enteral Nutrition via Gastrostomy and Total Parenteral Nutrition in Older Persons with Dysphagia: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217120. [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.A.; Krishnaswami, S.; Steger, E.; Conover, E.; Vaezi, M.F.; Ciucci, M.R.; Francis, D.O. Economic and Survival Burden of Dysphagia among Inpatients in the United States. Dis Esophagus 2018, 31, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Michel, A.; Vérin, E.; Gbaguidi, X.; Druesne, L.; Roca, F.; Chassagne, P. Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Community-Dwelling Older Patients with Dementia: Prevalence and Relationship with Geriatric Parameters. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018, 19, 770–774. [CrossRef]

- Brito, M.; Laranjo, A.; Nunes, G.; Oliveira, C.; Santos, C.A.; Fonseca, J. Anemia and Hematopoietic Factor Deficiencies in Patients after Endoscopic Gastrostomy: A Nine-Year and 472-Patient Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3637. [CrossRef]

- Cava, E.; Lombardo, M. Narrative Review: Nutritional Strategies for Ageing Populations - Focusing on Dysphagia and Geriatric Nutritional Needs. Eur J Clin Nutr 2025, 79, 285–295. [CrossRef]

- Keller, U. Nutritional Laboratory Markers in Malnutrition. JCM 2019, 8, 775. [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.-C.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chang, Y.-H.; Chen, C.-H.; Chiang, H.-C.; Huang, L.-C.; Yang, Y.-H.; Hung, C.-H. The Mortality and the Risk of Aspiration Pneumonia Related with Dysphagia in Stroke Patients. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases 2019, 28, 1381–1387. [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.T.; Ribeiro, P.W.; De Paiva, S.A.R.; Tanni, S.E.; Minicucci, M.F.; Zornoff, L.A.M.; Polegato, B.F.; Bazan, S.G.Z.; Modolo, G.P.; Bazan, R.; et al. Dysphagia and Tube Feeding after Stroke Are Associated with Poorer Functional and Mortality Outcomes. Clinical Nutrition 2020, 39, 2786–2792. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Nagano, A.; Ueshima, J.; Saino, Y.; Kawase, F.; Kobayashi, H.; Murotani, K.; Inoue, T.; Nagami, S.; Maeda, K. Prevalence of Dysphagia in Patients after Orthopedic Surgery. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 2024, 119, 105312. [CrossRef]

- Sherrod, B.; Nguyen, S.; Strauss, A.; Wilkerson, C.G.; Lawrence, B.; Spiker, W.R.; Spina, N.T.; Brodke, D.S.; Mazur, M.D.; Mahan, M.A.; et al. Predictors of Dysphagia Following Anterior Cervical Fusion. Neurosurgery 2020, 67. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).