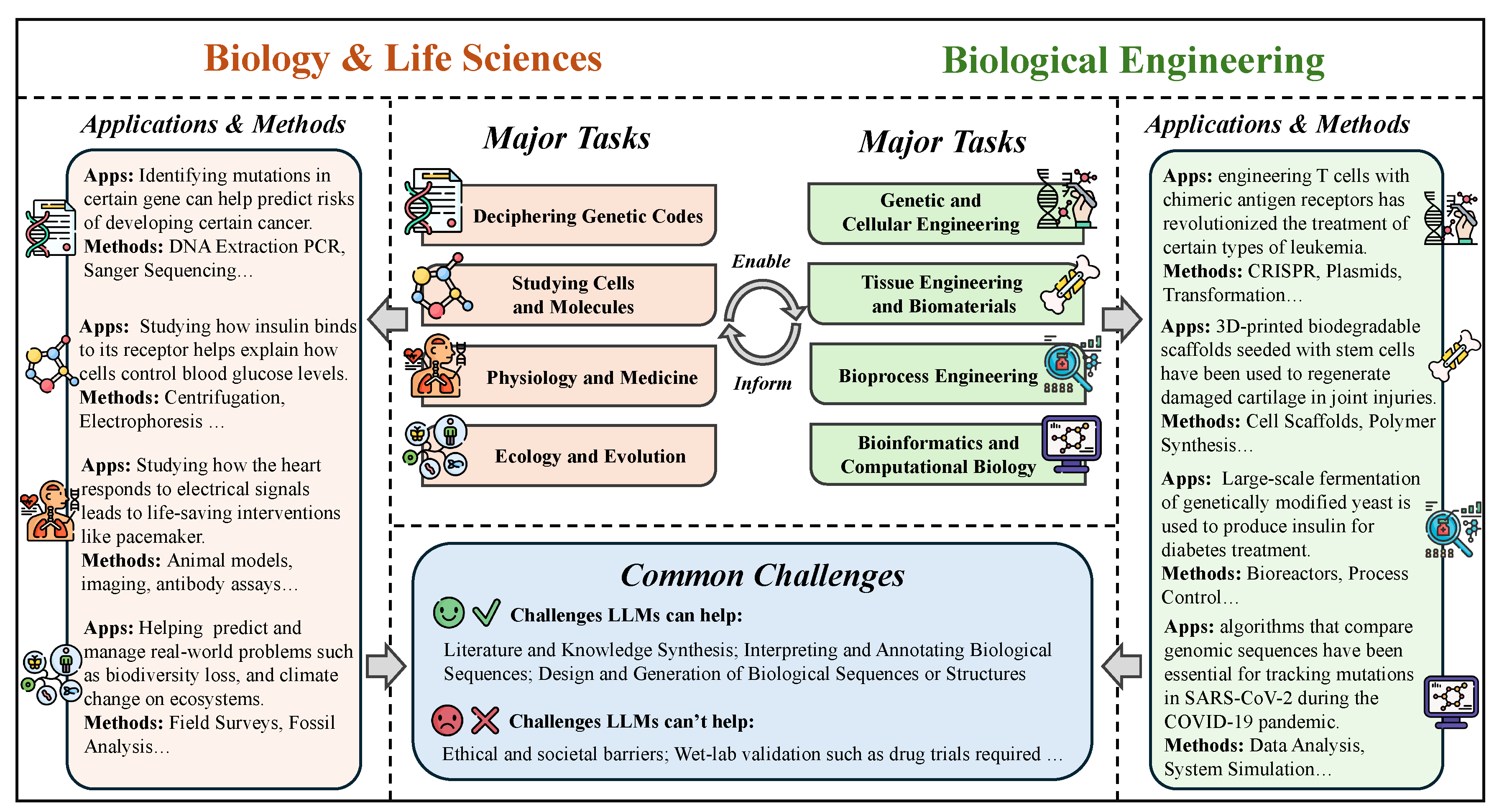

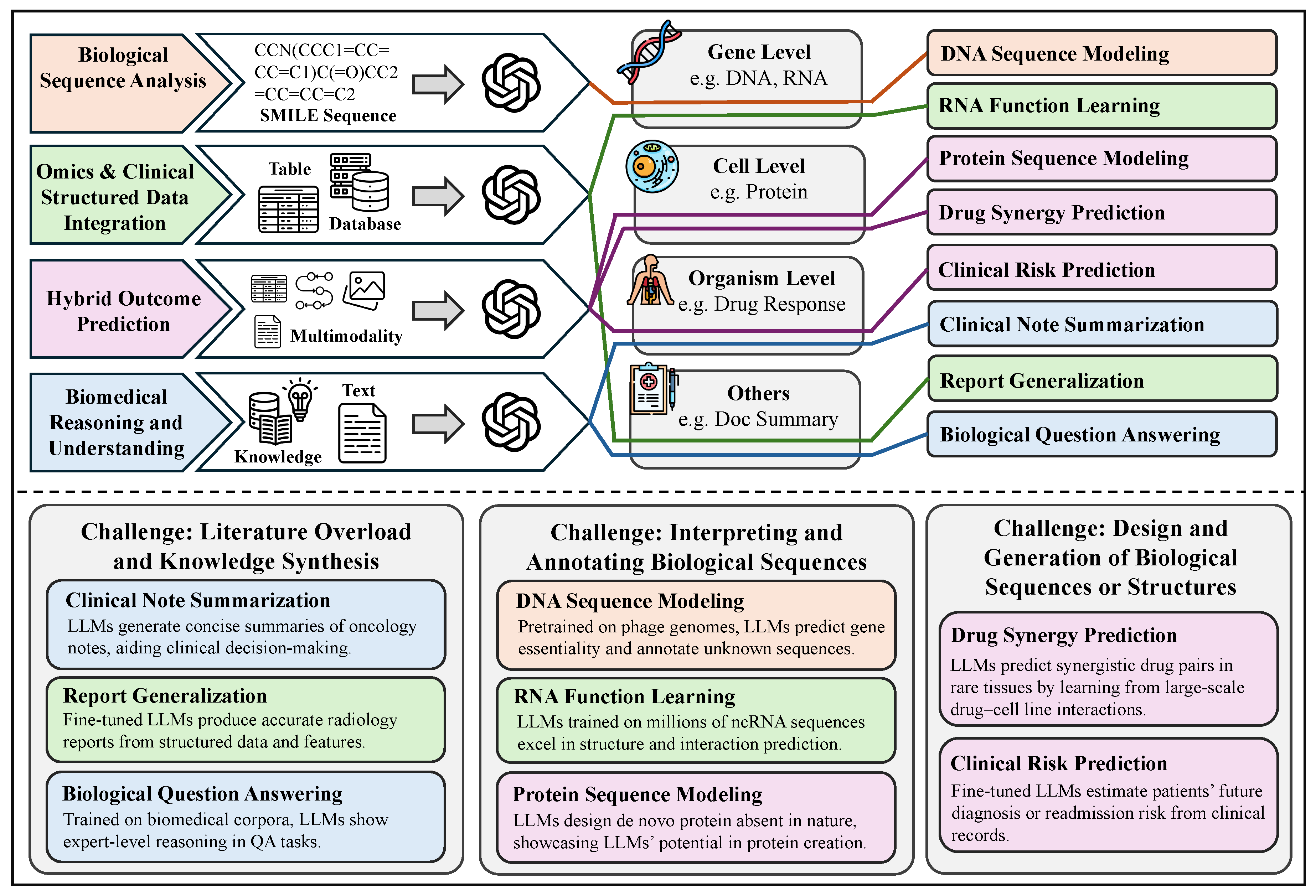

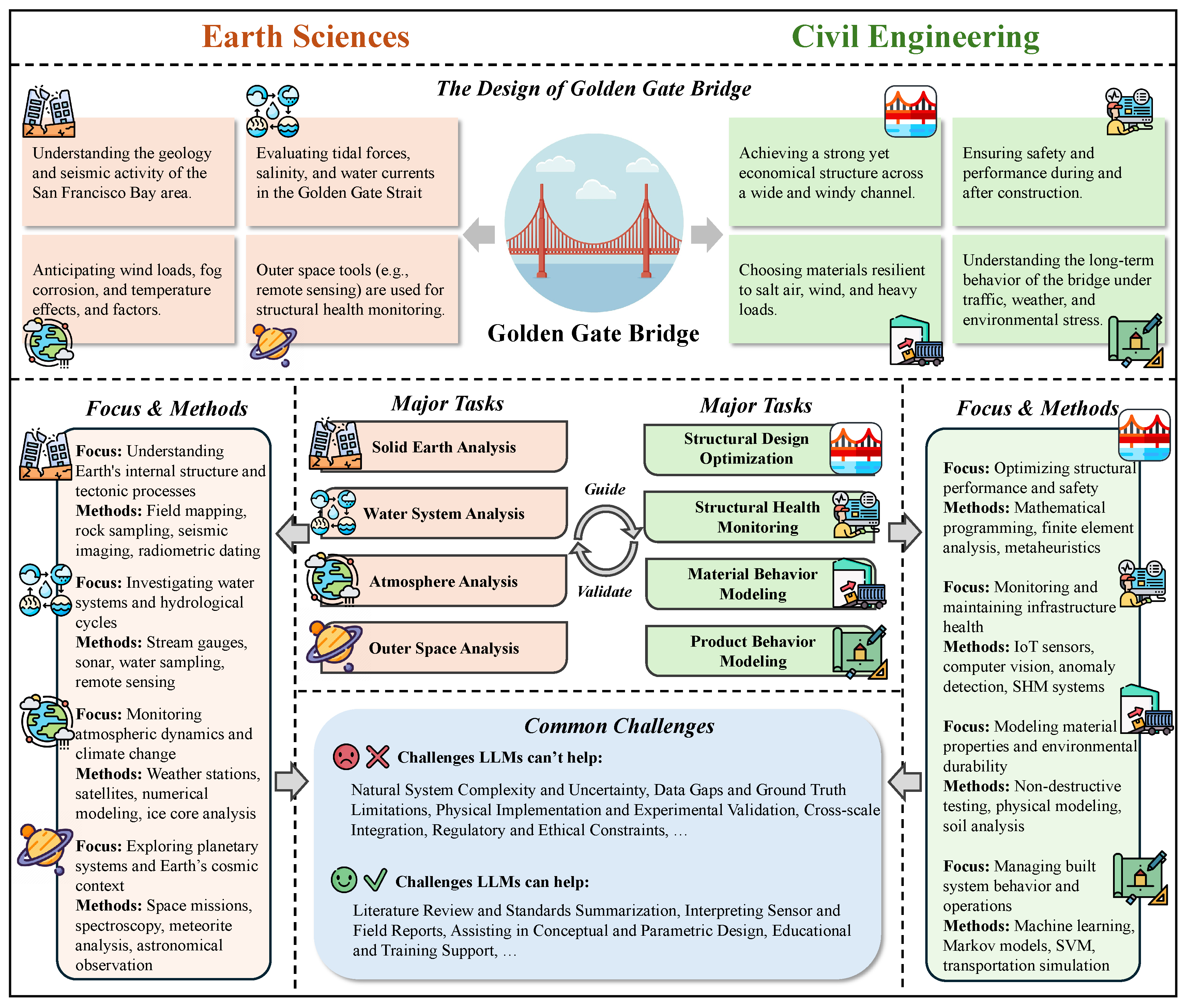

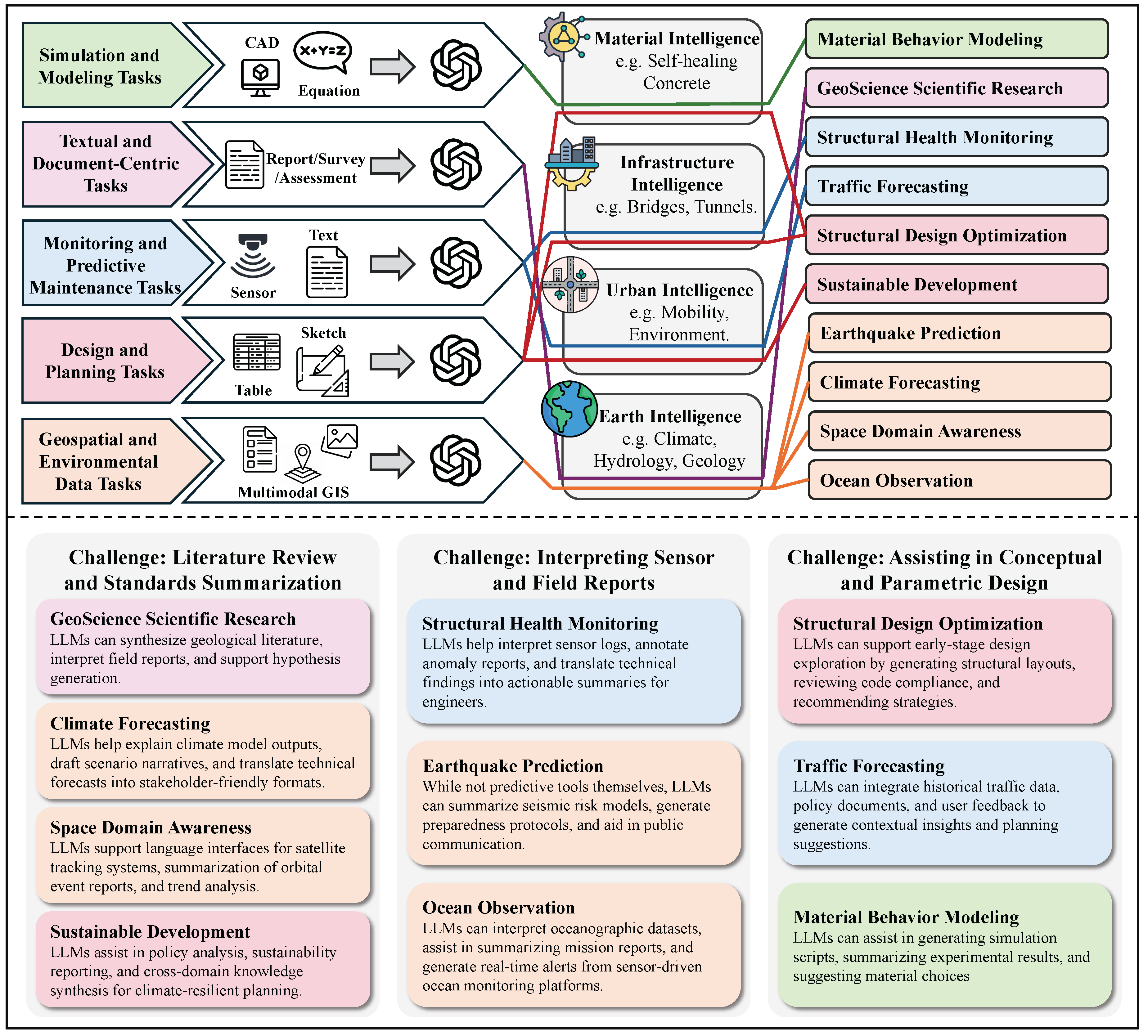

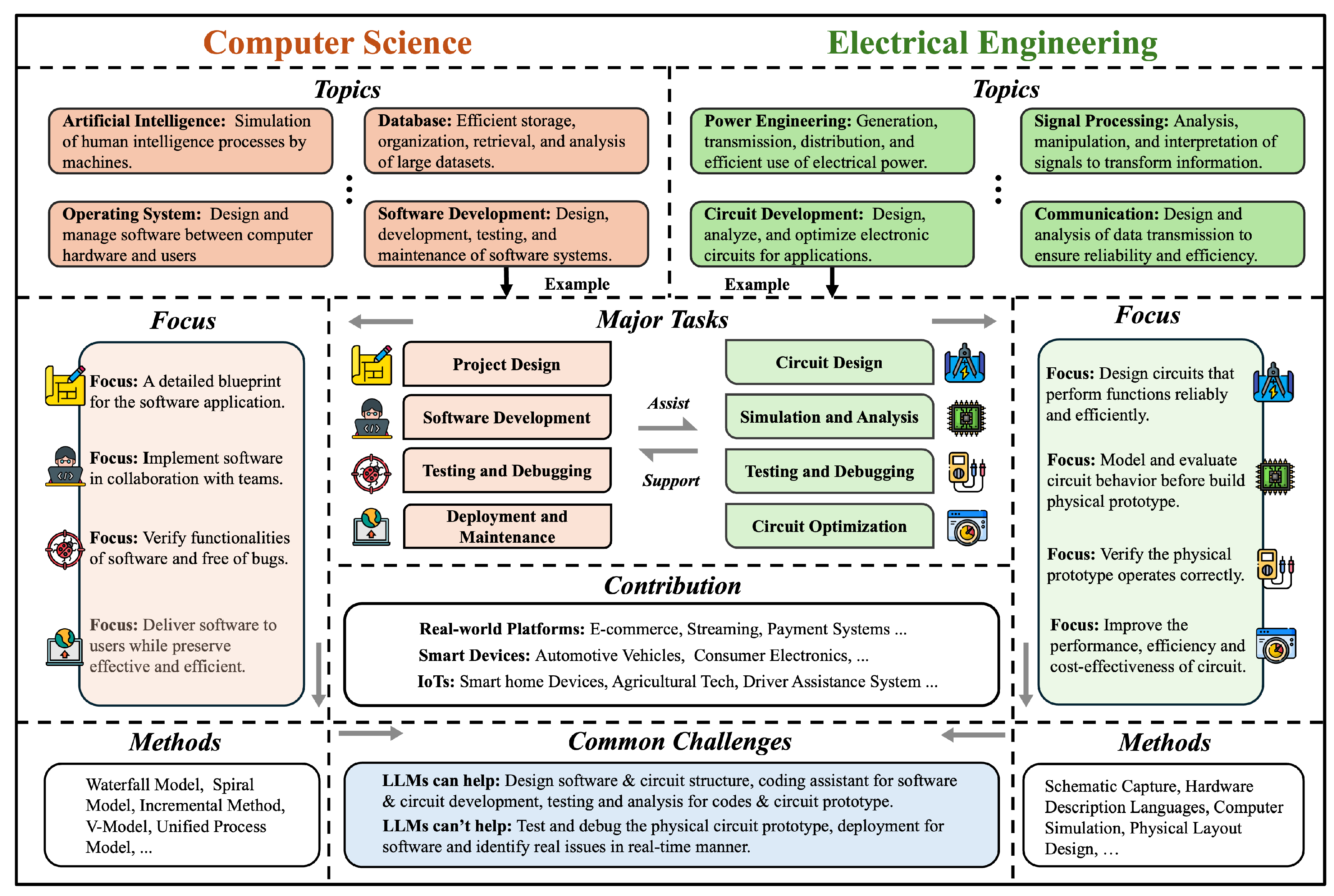

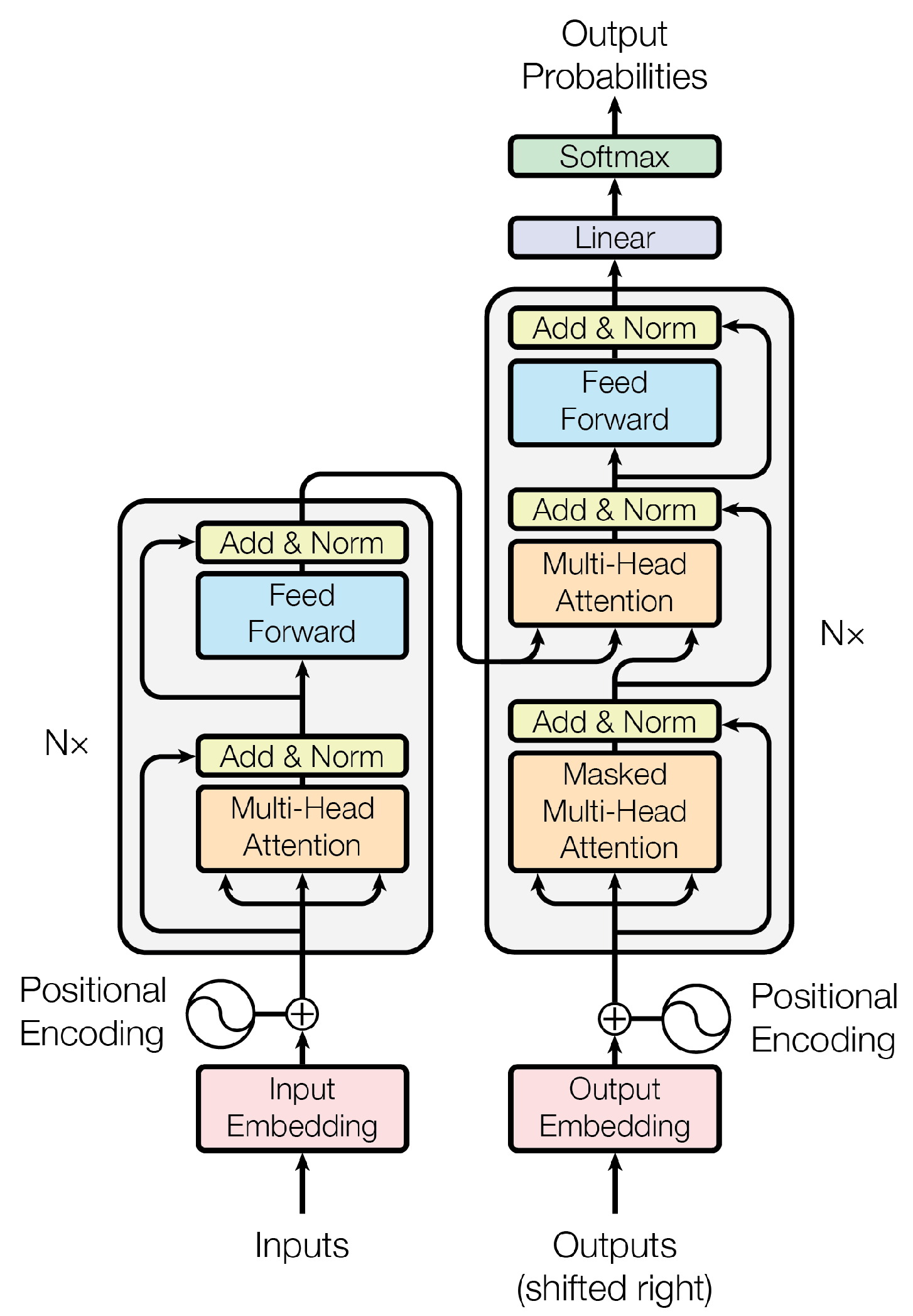

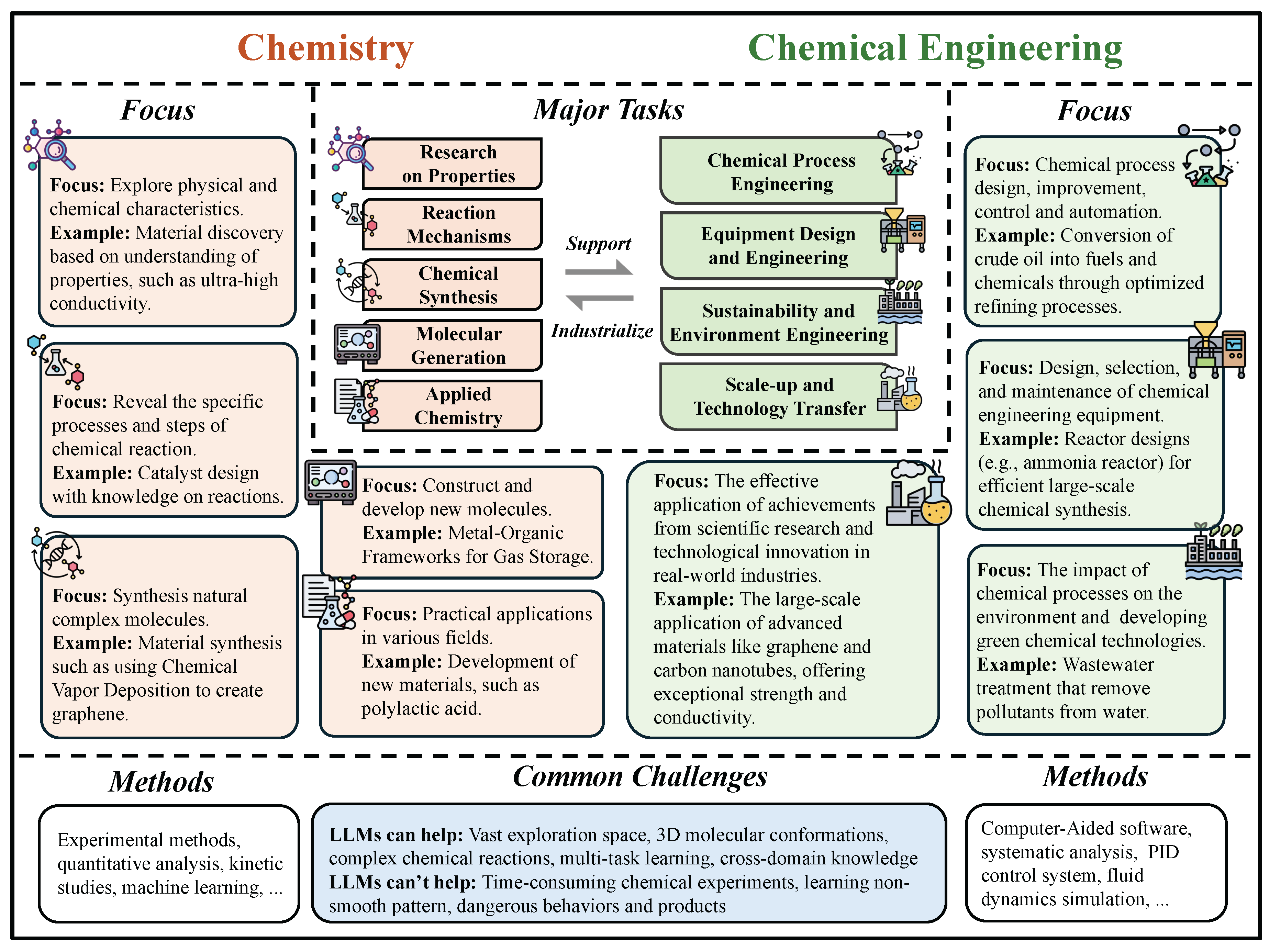

In this chapter, we chart how LLMs are utilized across science and engineering. The chapter spans mathematics; physics and mechanical engineering; chemistry and chemical engineering; life sciences and bioengineering; earth sciences and civil engineering; and computer science and electrical engineering. We open with mathematics—proof support, theoretical exploration and pattern discovery, math education, and targeted benchmarks. In physics and mechanical engineering, we cover documentation-centric tasks, design ideation and parametric drafting, simulation-aware and modeling interfaces, multimodal lab and experiment interpretation, and interactive reasoning, followed by domain-specific evaluations and a look at opportunities and limits. In chemistry and chemical engineering, we examine molecular structure and reaction reasoning, property prediction, materials optimization, test/assay mapping, property-oriented molecular design, and reaction-data knowledge organization, then compare benchmark suites. In life sciences and bioengineering section, we include genomic sequence analysis, clinical structured-data integration, biomedical reasoning and understanding, and hybrid outcome prediction, with emphasis on validation standards. In earth sciences and civil engineering section, we review geospatial and environmental data tasks, simulation and physical modeling, document workflows, monitoring and predictive maintenance, plus design/planning tasks, again with benchmarks. We close with computer science and electrical engineering: code generation and debugging, large-codebase analysis, hardware description language code generation, functional verification, and high-level synthesis, capped by purpose-built benchmarks and a final discussion of impacts and open challenges.

5.2. Physics and Mechanical Engineering

5.2.1. Overview

5.2.1.1 Introduction to Physics

Physics is a natural science that investigates the fundamental principles governing matter, energy, and their interactions through experimental observation and theoretical modeling [

702]. It spans from the smallest subatomic particles to the largest cosmic structures, aiming to establish predictive, explanatory, and unifying frameworks for natural phenomena [

703]. As the most fundamental natural science, physics provides conceptual foundations and methodological tools that support other sciences and engineering disciplines [

704].

Simply put, physics is the science of understanding how the world works. It seeks to explain everyday phenomena, such as why apples fall, why lights turn on, or why we can see stars [

702]. It not only provides explanations but also empowers us to harness these laws to develop new technologies [

705].

For example, the detection of gravitational waves marked one of the most significant breakthroughs in 21st-century physics [

706]. First predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity, gravitational waves had eluded direct observation for a century due to their extremely weak nature [

707]. In 2015, the LIGO interferometer in the United States successfully captured signals produced by the collision of two black holes [

706]. This discovery not only confirmed theoretical predictions but also launched a new field—gravitational wave astronomy [

708]—with far-reaching impacts on astrophysics, cosmology, and quantum gravity [

709,

710].

The discipline of physics is vast and typically organized into three core domains, each addressing a class of natural phenomena and associated methodologies [

711]:

Fundamental Theoretical Physics. This domain focuses on uncovering the basic laws of nature and forms the theoretical foundation of the entire field of physics [

712]. It encompasses classical mechanics, electromagnetism, thermodynamics, statistical mechanics, quantum mechanics, and relativity [

712]. The scope ranges from macroscopic motion (e.g., acceleration, vibration, and waves) to the behavior of subatomic particles (e.g., electron transitions, spin, self-consistent fields), and includes the structure of spacetime under extreme conditions such as near black holes [

713]. Researchers in this domain employ abstract mathematical tools such as differential equations, Lagrangian and Hamiltonian mechanics, and group theory to construct theoretical models and derive predictions [

714]. These models not only guide experimental physics but also provide essential frameworks for engineering applications [

715].

Physics of Matter and Interactions. This domain explores the microscopic structure of matter, the interaction mechanisms across different scales, and how these determine macroscopic material properties [

716]. Major subfields include condensed matter physics, atomic physics, molecular physics, nuclear physics, and particle physics [

717,

718]. Key research topics cover crystal structure, electronic band theory, spin and magnetism, superconductivity, quantum phase transitions, and the classification and interaction of elementary particles [

716,

718]. Common methodologies include first-principles calculations, quantum statistical modeling, and large-scale experiments involving synchrotron radiation, laser spectroscopy, or high-energy accelerators [

719]. The findings from this domain have led to breakthroughs in semiconductor devices, materials development, quantum computing, and energy systems, driving significant technological innovation [

720,

721].

Cosmic and Large-Scale Physics. This domain addresses phenomena at scales far beyond laboratory conditions and includes astrophysics, cosmology, and plasma physics [

722]. It investigates topics such as stellar evolution, galactic dynamics, gravitational wave propagation, early-universe inflation, and the nature of dark matter and dark energy [

723]. In parallel, plasma physics explores phenomena like solar wind, magnetospheric dynamics, and the behavior of ionized matter in space environments [

724]. Research in this domain typically relies on astronomical observations (e.g., telescopes, gravitational wave detectors, space missions), theoretical models, and large-scale simulations, forming a triad of “observation + simulation + theory” [

725].

Together, these three domains constitute the intellectual architecture of modern physics [

726]. From particle collisions in ground-based accelerators to observations of distant galaxies, physics consistently strives to understand the most fundamental laws of nature [

727]. With the emergence of artificial intelligence, high-performance computing, and advanced instrumentation, the research landscape of physics continues to expand—becoming increasingly intelligent, interdisciplinary, and precise [

728].

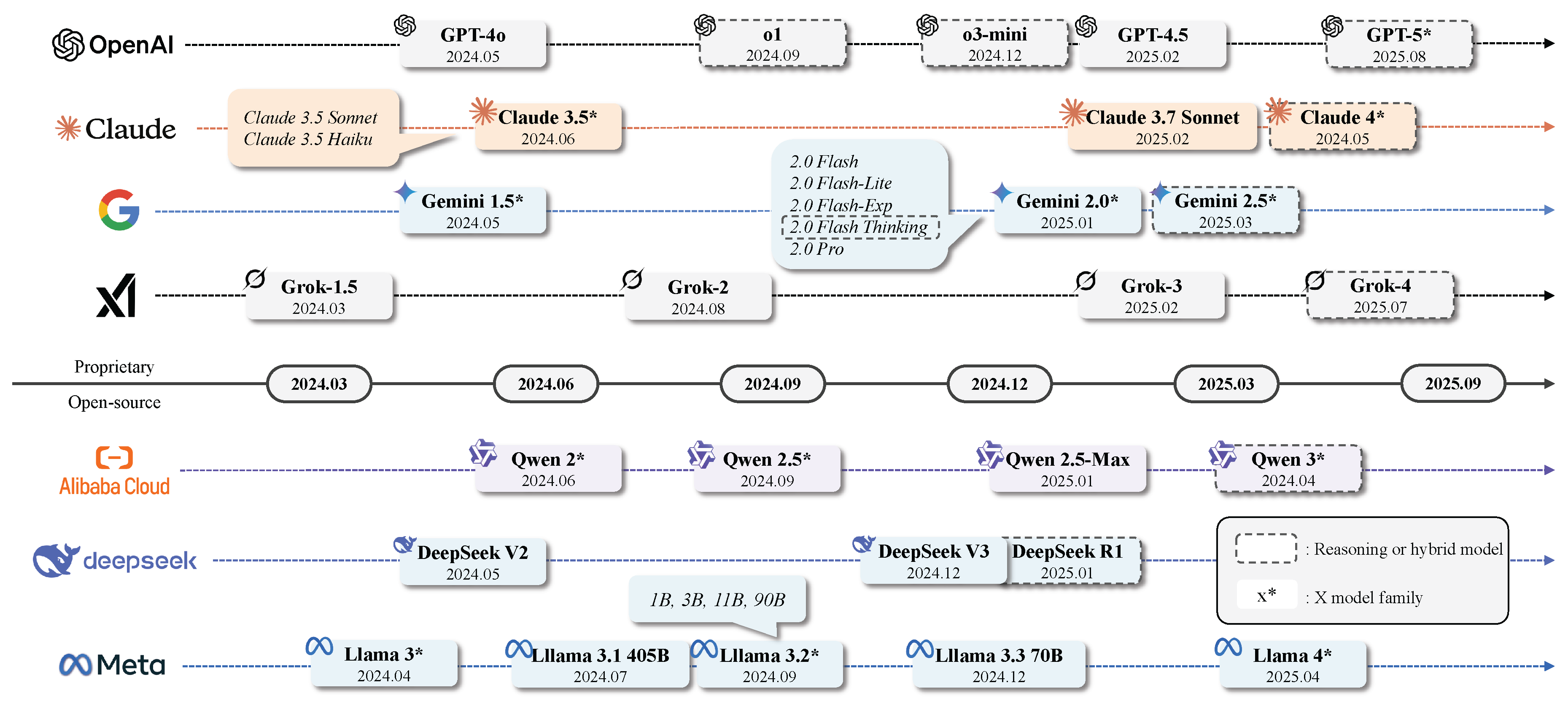

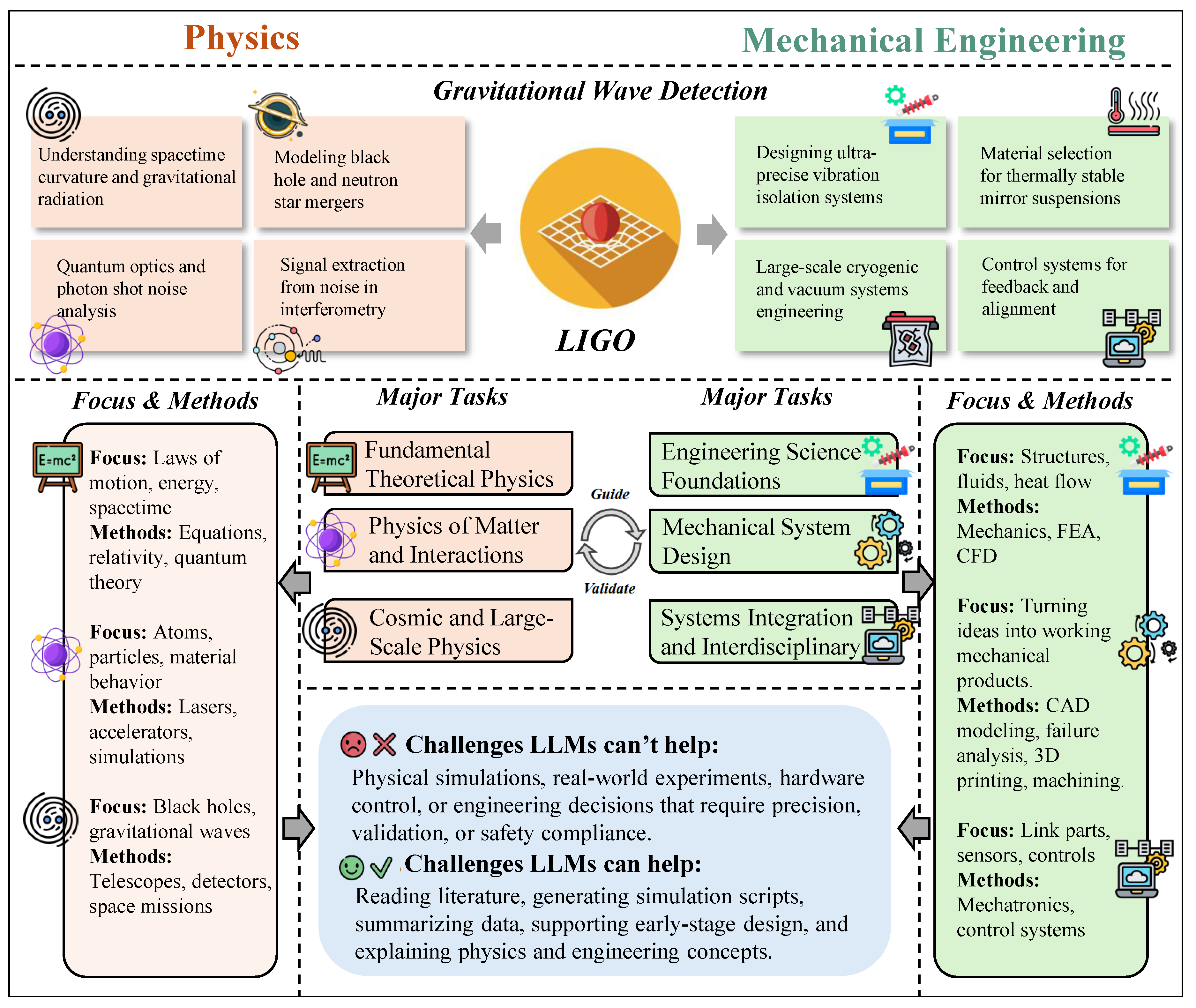

Figure 15.

The relationships between major research tasks between physics and mechanical engineering.

Figure 15.

The relationships between major research tasks between physics and mechanical engineering.

5.2.1.2 Introduction to Mechanical Engineering

Mechanical engineering is an applied discipline that focuses on the design, analysis, manufacturing, and control of mechanical systems driven by the principles of force, energy, and motion [

729]. It integrates engineering mechanics, thermofluid sciences, materials engineering, control theory, and computational tools to solve problems across a wide range of industries. As a foundational engineering field, mechanical engineering provides the backbone for technological advancement in transportation, energy, robotics, aerospace, and biomedical systems [

730].

In simple terms, mechanical engineering is the science and craft of making things move and work reliably. From engines and turbines to robots and surgical devices, it turns physical principles into functional products through design and manufacturing [

730].

For example, the construction of the LIGO gravitational wave observatory represents not only a milestone in fundamental physics but also a triumph of mechanical engineering. LIGO’s ultrahigh-vacuum interferometers required vibration isolation at nanometer precision, thermally stable mirror suspensions, and large-scale structural systems integrated with active control. These engineering feats enabled the detection of gravitational waves, a task demanding extreme precision in structure, thermal regulation, and dynamic stability [

706].

The field of mechanical engineering is vast and is typically categorized into three core domains, each covering a range of methodologies and applications:

Engineering Science Foundations. This domain forms the analytical and physical core of mechanical engineering. It encompasses:

Mechanics: including statics, dynamics, solid mechanics, and continuum mechanics, used to model the deformation, motion, and failure of structures [

731].

Thermal and fluid sciences: covering heat conduction, convection, fluid dynamics, thermodynamics, and phase-change phenomena [

732].

Systems and control: involving system dynamics, feedback control theory, and mechatronic integration [

733]. These fundamentals are implemented via tools such as finite element analysis (FEA), computational fluid dynamics (CFD), and system modeling platforms like Simulink and Modelica [

734,

735].

Mechanical System Design and Manufacturing. This domain addresses how ideas become real-world engineered products. It includes:

Mechanical design: CAD modeling, mechanism design, stress analysis, failure prediction, and design optimization [

736].

Manufacturing: traditional subtractive methods (e.g., milling, turning), additive manufacturing (3D printing), surface finishing, and process planning [

737].

Smart manufacturing and Industry 4.0: integration of sensors, data analytics, automation, and cyber-physical systems to create responsive and intelligent production environments [

738]. These technologies bridge the gap between virtual design and physical realization.

Systems Integration and Interdisciplinary Applications. Modern mechanical systems are often multi-functional and cross-disciplinary. This domain focuses on:

Robotics and mechatronics: combining mechanics, electronics, and computing to build intelligent machines [

739].

Energy and thermal systems: engines, fuel cells, solar collectors, HVAC systems, and sustainable energy technologies [

740].

Biomedical and bioinspired systems: development of prosthetics, surgical tools, and biomechanical simulations [

741].

Multiphysics modeling and digital twins: simulation of systems involving coupled fields (thermal, fluidic, mechanical, electrical) and virtual prototyping [

742]. This integration-driven domain reflects mechanical engineering’s evolution toward intelligent, efficient, and adaptive systems. Together, these three domains define the scope of modern mechanical engineering. From high-speed trains and wind turbines to nanomechanical actuators and wearable exoskeletons, mechanical engineers shape the physical world with ever-growing precision and complexity [

729,

730].

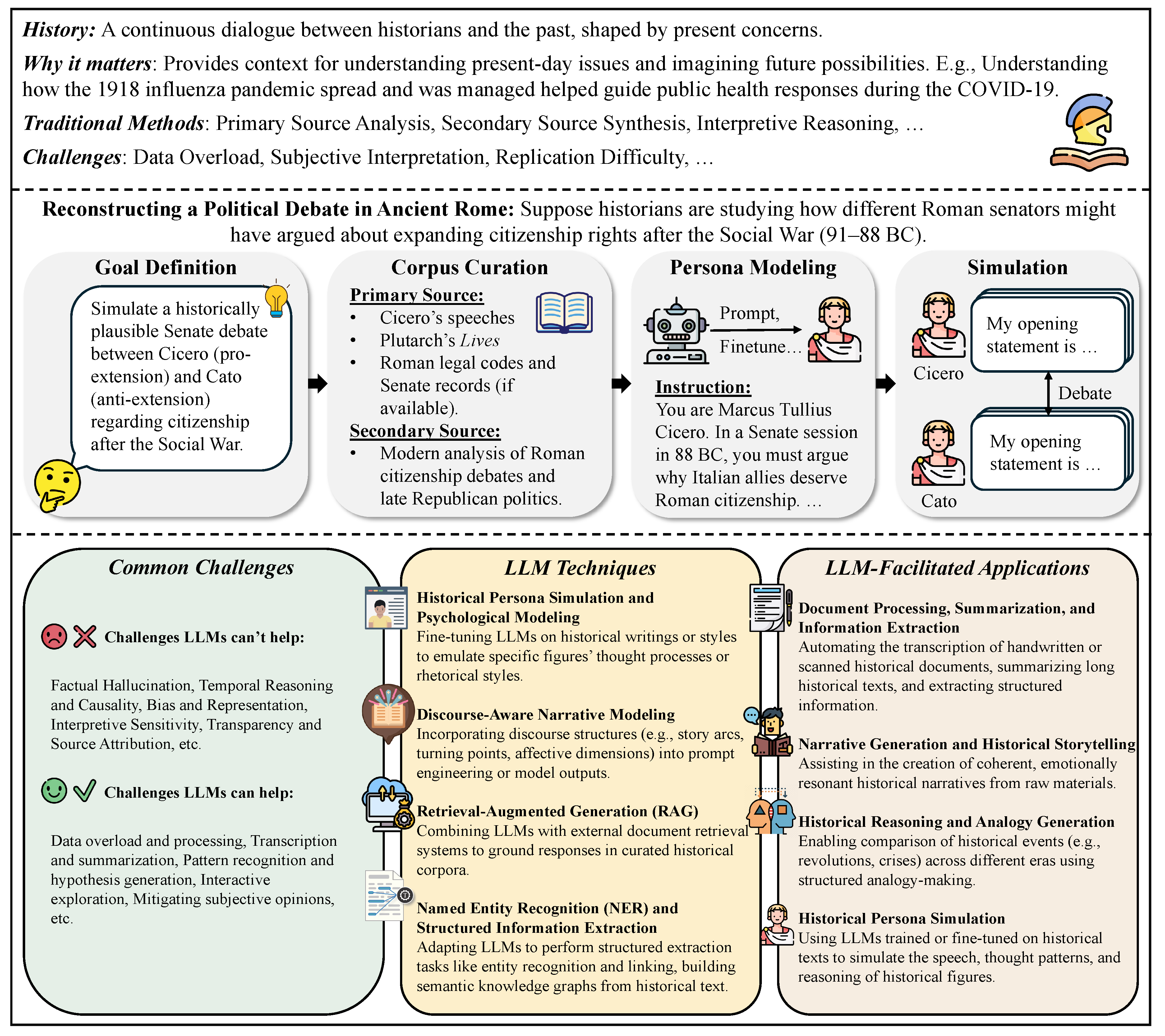

5.2.1.3 Current Challenges

Physics and mechanical engineering are closely interwoven disciplines that form the foundation for understanding and shaping the material and technological world. Physics seeks to uncover the fundamental laws of nature that govern matter, motion, energy, and forces, while mechanical engineering applies these principles to design, optimize, and control systems that power modern life. Together, they enable critical innovations across transportation, energy, manufacturing, healthcare, and space exploration. These disciplines are indispensable for solving complex, cross-scale challenges such as energy efficiency, automation, sustainable mobility, and precision instrumentation. Despite rapid progress in theoretical modeling, simulation, and intelligent design tools, both fields continue to grapple with the intricacies of nonlinear dynamics, multiphysics coupling, and real-world uncertainties in physical systems.

Still Hard with LLMs: The Tough Problems.

Complexity of Multiphysics Coupling and Governing Equations. Physical and mechanical systems are often governed by a series of highly coupled partial differential equations (PDEs), involving nonlinear dynamics, continuum mechanics, thermodynamics, electromagnetism, and quantum interactions [

734,

743]. Solving such systems requires professional numerical solvers, high-fidelity discretization techniques, and physics-informed modeling assumptions. Although LLMs can retrieve relevant equations or suggest approximate forms, they are incapable of deriving physical laws, ensuring conservation principles, or performing accurate numerical simulations.

Simulation Accuracy and Model Calibration. Accurate mechanical design and physical predictions typically rely on high-fidelity simulations such as finite element analysis (FEA), computational fluid dynamics (CFD), or multiphysics modeling [

744,

745]. These simulations demand precise geometry input, boundary conditions, material models, and experimental validation. LLMs may assist in interpreting simulation reports or proposing modeling strategies, but they lack the resolution, numerical rigor, and feedback integration necessary to execute or validate such models.

Experimental Prototyping and Hardware Integration. Engineering innovations ultimately require validation through physical experiments—building prototypes, tuning actuators, installing sensors, and measuring performance under dynamic conditions [

746,

747]. These tasks depend on laboratory facilities, fabrication tools, and hands-on experimentation, all of which are beyond the operational scope of LLMs. While LLMs can help generate test plans or documentation, they cannot replace real-world testing or iterative hardware development.

Materials and Manufacturing Constraints. Real-world engineering designs must account for constraints such as thermal stress, fatigue life, manufacturability, and cost-efficiency [

748]. Addressing these challenges often relies on materials testing, manufacturing standards, and domain experience in processes like welding, casting, and additive manufacturing. LLMs lack access to real-time physical data and material behavior, and thus cannot support tradeoff decisions in design or production.

Ethical, Safety, and Regulatory Considerations. From biomedical devices to autonomous systems, mechanical engineers must weigh ethical impacts, user safety, and legal compliance [

749]. Although LLMs can summarize policies or regulatory codes, they are not equipped to make decisions involving responsibility, risk evaluation, or normative judgment—elements essential for deploying certified, real-world systems.

Easier with LLMs: The Parts That Move.

Although current LLMs remain limited in core tasks such as physical modeling and experimental validation, they have shown growing potential in assisting a variety of supporting tasks in physics and mechanical engineering—particularly in knowledge integration, document drafting, design ideation, and educational support:

Literature Review and Standards Lookup. Both disciplines rely heavily on technical documents such as material handbooks, design standards, experimental protocols, and scientific publications. LLMs can significantly accelerate the literature review process by extracting key information about theoretical models, experimental conditions, or engineering parameters. For instance, an engineer could use an LLM to compare different welding codes, retrieve thermal fatigue limits of materials, or summarize applications of a specific mechanical model [

750,

751].

Assisting with Simulation and Test Report Interpretation. In simulations such as finite element analysis (FEA), computational fluid dynamics (CFD), or structural testing, LLMs can help parse simulation logs, identify setup issues, or generate summaries of experimental findings. When integrated with domain-specific tools, LLMs may even assist in generating simulation input files, interpreting outliers in results, or recommending appropriate post-processing techniques [

752,

753].

Supporting Conceptual Design and Parametric Exploration. During early-stage mechanical design or material selection, LLMs can suggest structural concepts, propose parameter combinations, or retrieve examples of similar engineering cases. For instance, given a prompt like “design a spring for high-temperature fatigue conditions,” the model might generate candidate materials, geometric options, and common failure modes [

754,

755].

Engineering Education and Learning Support. Education in physics and mechanical engineering involves both theoretical understanding and hands-on application. LLMs can generate step-by-step derivations, support simulation-based exercises, or simulate simple lab setups (e.g., free fall, heat conduction, beam deflection). They can also assist with terminology explanation or provide example problems to enhance interactive and self-guided learning [

756,

757].

In summary, while physical modeling, engineering intuition, and experimental testing remain essential in physics and mechanical engineering, LLMs are emerging as effective tools for information synthesis, design reasoning, documentation, and education. The future of these disciplines may be shaped by deep integration between LLMs, simulation platforms, engineering software, and laboratory systems—paving the way from textual reasoning to intelligent system collaboration.

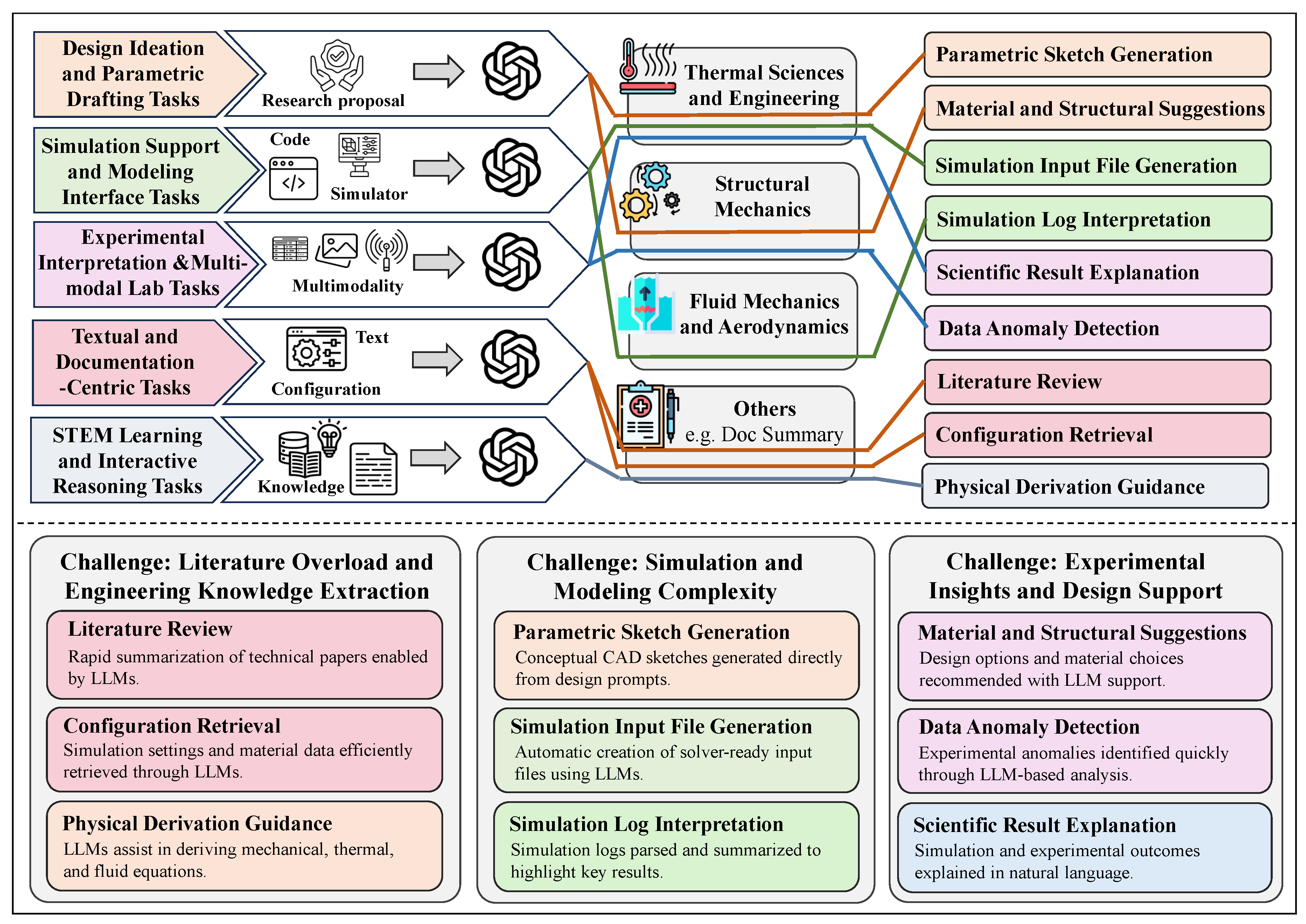

Figure 16.

The pipelines of physics and mechanical engineering.

Figure 16.

The pipelines of physics and mechanical engineering.

5.2.1.4 Taxonomy

Research in physics and mechanical engineering spans a broad spectrum of problems, from modeling fundamental laws of nature to designing and validating engineered systems. With the rapid development of LLMs, many of these tasks are being redefined through human-AI collaboration, automation, and intelligent assistance. Traditionally, physics and mechanical engineering are divided along disciplinary lines—e.g., thermodynamics, solid mechanics, control systems—but from the perspective of LLM-based systems, it is more productive to reorganize tasks based on their computational characteristics and data modalities.

This functional, task-driven taxonomy helps distinguish where LLMs can take on primary responsibilities, where they act in a supporting role, and where traditional numerical methods and expert reasoning remain indispensable. Based on this perspective, we propose five major categories that capture the current landscape of LLM-integrated research in physics and mechanical engineering:

Textual and Documentation-Centric Tasks. LLMs are particularly effective in processing technical documents, engineering standards, lab reports, and scientific literature. For instance, Polverini and Gregorcic demonstrated how LLMs can support physics education by extracting and explaining key information from conceptual texts [

758], while Harle et al. highlighted their use in organizing and generating instructional materials for engineering curricula [

759].

Design Ideation and Parametric Drafting Tasks. In early-stage design and manufacturing workflows, LLMs can transform natural language prompts into CAD sketches, material recommendations, and parameter ranges. The MIT GenAI group systematically evaluated the capabilities of LLMs across the entire design-manufacture pipeline [

760], and Wu et al. introduced CadVLM, a multimodal model that translates linguistic input into parametric CAD sketches [

755].

Simulation-Support and Modeling Interface Tasks. Although LLMs cannot replace high-fidelity physical simulation, they can assist in generating model input files, translating specifications into solver-ready formats, and summarizing results. Ali-Dib and Menou explored the reasoning capacity of LLMs in physics modeling tasks [

761], while Raissi et al.’s PINN framework demonstrated how language-driven architectures can help solve nonlinear partial differential equations by encoding physics into neural representations [

762].

Experimental Interpretation and Multimodal Lab Tasks. In experimental workflows, LLMs can support data summarization, anomaly detection, and textual explanation of multimodal results. Latif et al. proposed PhysicsAssistant, an LLM-powered robotic learning system capable of interpreting physics lab scenarios and offering real-time feedback to students and instructors [

763].

STEM Learning and Interactive Reasoning Tasks. LLMs are increasingly integrated into educational settings to guide derivations, answer conceptual questions, and simulate physical systems. Jiang and Jiang introduced a tutoring system that enhanced high school students’ understanding of complex physics concepts using LLMs [

756], while Polverini’s work further confirmed the model’s utility in supporting structured, interactive learning [

758].

5.2.2. Textual and Documentation-Centric Tasks

In physics and mechanical engineering, researchers and engineers routinely interact with large volumes of unstructured text: scientific papers, technical manuals, design specifications, test reports, and equipment logs. These documents are often dense, domain-specific, and heterogeneous in format. LLMs provide a promising tool for automating the extraction, summarization, and interpretation of this information.

One of the primary use cases is literature review and standards extraction. LLMs can parse multiple engineering reports or scientific articles to extract key findings, quantitative parameters, or references to specific standards, thereby reducing time-consuming manual review. For example, Khan et al. (2024) showed that LLMs can effectively assist in requirements engineering by identifying constraints and design goals from complex textual documents [

764].

Another growing application is in log interpretation and structured report analysis. In mechanical systems testing and diagnostics, engineers often work with detailed experiment logs and operational narratives. Tian et al. (2024) demonstrated that LLMs can identify conditions, setup parameters, and key outcomes from such semi-structured text logs, making them useful in experiment-driven engineering workflows [

765].

Furthermore, LLMs have been applied in sensor data documentation and matching. Berenguer et al. (2024) proposed an LLM-based system that interprets natural language descriptions to retrieve relevant sensor configurations and data, effectively bridging the gap between textual requirements and structured data sources [

766].

These applications point to a broader role for LLMs as interfaces between human engineers and machine-readable engineering assets, enabling a smoother flow of information across documentation, modeling, and decision-making. While challenges remain—particularly in domain-specific precision and context disambiguation—the utility of LLMs in handling technical documentation is becoming increasingly evident.

5.2.3. Design Ideation and Parametric Drafting Tasks

In physics and mechanical engineering, the early stages of design—where ideas are generated and formalized into parameter-driven models—play a critical role in shaping the final product. These processes traditionally require both deep domain knowledge and creativity, often relying on iterative exploration using CAD tools, handwritten specifications, and physical prototyping. With the emergence of LLMs, this early design workflow is being significantly transformed. LLMs can help engineers rapidly generate, interpret, and modify design concepts using natural language, thus improving both accessibility and productivity in the drafting process.

Recent studies have shown that LLMs are capable of generating design concepts from textual prompts that describe functional requirements or contextual constraints. For instance, Makatura et al. (2023) introduced a benchmark for evaluating LLMs on design-related tasks, showing that these models can generate reasonable design plans and material suggestions purely based on natural language input [

767]. This capability supports brainstorming and variant generation, especially in multidisciplinary systems where engineers must evaluate many trade-offs quickly.

Beyond concept generation, LLMs are increasingly used to support parametric drafting. This involves translating natural language into design specifications, such as dimensioned geometry, material choices, and assembly constraints. Wu et al. (2024) proposed CadVLM, a model capable of generating parametric CAD sketches from language-vision input, bridging LLMs with traditional CAD workflows [

755]. Such models allow engineers to iterate on design through language-driven instructions (e.g., “Make the slot wider by 2 mm” or “Add a fillet at the bottom edge”), greatly simplifying the communication between design intent and digital geometry.

Some systems have also incorporated LLMs directly into CAD environments, allowing interactive, prompt-based drafting and editing. Tools like SketchAssistant and AutoSketch use LLMs to assist with geometry creation and layout proposals. These interfaces reduce the learning curve for non-expert users and open up early-stage design to a broader range of collaborators. However, challenges remain in aligning generated outputs with engineering standards, ensuring the manufacturability of outputs, and maintaining traceability between design versions and decision logic.

Overall, LLMs are becoming valuable collaborators in the ideation-to-drafting pipeline of physics and mechanical engineering design. While they are not yet substitutes for domain expertise or formal simulation, they significantly accelerate exploration, reduce iteration costs, and expand accessibility to design tools.

5.2.4. Simulation-support and Modeling Interface Tasks

In physics and mechanical engineering, simulations play a critical role in modeling complex systems, validating designs, and predicting behavior. Traditionally, configuring and running simulations requires significant domain expertise, specialized tools, and manual scripting. The integration of LLMs into simulation workflows is introducing new levels of efficiency and accessibility.

LLMs can translate natural language descriptions of physical setups into structured simulation code or configuration files. For example,

FEABench evaluates the ability of LLMs to solve finite element analysis (FEA) tasks from text-based prompts and generate executable multiphysics simulations, showing encouraging performance across benchmark problems [

752]. Similarly,

MechAgents demonstrates how LLMs acting as collaborative agents can solve classical mechanics problems (e.g., elasticity, deformation) through iterative planning, coding, and error correction [

753].

Beyond code generation, LLMs are being deployed as intelligent simulation interfaces.

LangSim, developed by the Max Planck Institute, connects LLMs to atomistic simulation software, enabling users to query and configure simulations via natural language [

768]. Such systems lower the barrier for non-experts to engage in simulation workflows, automate routine tasks, and reduce friction in setting up complex models.

Moreover, LLMs can help interpret simulation results, summarize outcome trends, and generate human-readable reports that connect raw numerical output with engineering reasoning. This interpretability is especially valuable in multi-physics scenarios where simulation logs and visualizations are often overwhelming.

While these advances are promising, there remain limitations in LLMs’ ability to ensure physical correctness, handle multiphysics coupling, and reason over temporal or boundary conditions. Nonetheless, their role as modeling assistants is becoming increasingly practical in early prototyping and parametric studies.

5.2.5. Experimental Interpretation and Multimodal Lab Tasks

In physics and mechanical engineering, laboratory experiments often generate complex datasets comprising textual logs, numerical measurements, images, and sensor outputs. Interpreting these multimodal datasets requires significant expertise and time. The advent of LLMs offers promising avenues to streamline this process by enabling automated analysis and interpretation of diverse data types.

LLMs can assist in translating experimental procedures and observations into structured formats, facilitating easier analysis and replication. For instance, integrating LLMs with graph neural networks has been shown to enhance the prediction accuracy of material properties by effectively combining textual and structural data [

769]. This multimodal approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of experimental outcomes.

Moreover, LLMs have demonstrated capabilities in interpreting complex scientific data, such as decoding the meanings of eigenvalues, eigenstates, or wavefunctions in quantum mechanics, providing plain-language explanations that bridge the gap between complex mathematical concepts and intuitive understanding [

770]. Such applications highlight the potential of LLMs in making intricate experimental data more accessible.

Additionally, frameworks like GenSim2 utilize multimodal and reasoning LLMs to generate extensive training data for robotic tasks by processing and producing text, images, and other media, thereby enhancing the training efficiency for robots in performing complex tasks [

771].

Despite these advancements, challenges remain in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of LLM-generated interpretations, especially when dealing with noisy or incomplete data. Ongoing research focuses on improving the robustness of LLMs in handling diverse and complex experimental datasets.

5.2.6. STEM Learning and Interactive Reasoning Tasks

LLMs are increasingly being integrated into STEM education to enhance learning experiences and support interactive reasoning tasks. Their ability to process and generate human-like text allows for more engaging and personalized educational tools.

LLMs can simulate teacher-student interactions, providing real-time feedback and explanations that adapt to individual learning needs. This capability has been utilized to improve teaching plans and foster deeper understanding in subjects like mathematics and physics [

771]. Additionally, LLMs have been employed to interpret and grade student responses, offering partial credit and constructive feedback, which aids in the learning process [

772].

Interactive learning environments powered by LLMs, such as AI-driven tutoring systems, have shown promise in facilitating inquiry-based learning and promoting critical thinking skills. These systems can guide students through problem-solving processes, encouraging them to explore concepts and develop reasoning abilities [

770].

Despite these advancements, challenges remain in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of LLM-generated content. Ongoing research focuses on improving the alignment of LLM outputs with educational objectives and integrating multimodal data to support diverse learning styles.

Table 31.

Physics and Mechanical Engineering Tasks and Benchmarks

Table 31.

Physics and Mechanical Engineering Tasks and Benchmarks

| Type of Task |

Benchmarks |

Introduction |

| CAD and Geometric Modeling |

ABC Dataset [773] DeepCAD [774] Fusion 360 Gallery [775] CADBench [776] |

The ABC Dataset, DeepCAD, and Fusion 360 Gallery together provide a comprehensive foundation for studying geometry-aware language and generative models. While ABC emphasizes clean, B-Rep-based CAD structures suitable for geometric deep learning, DeepCAD introduces parameterized sketches tailored for inverse modeling tasks. Fusion 360 Gallery complements these with real-world user-generated modeling histories, enabling research on sequential CAD reasoning and practical design workflows. CADBench further supports instruction-to-script evaluation by providing synthetic and real-world prompts paired with CAD programs. It serves as a high-resolution benchmark for measuring attribute accuracy, spatial correctness, and syntactic validity in code-based CAD generation. |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) |

FEABench [? ] |

FEABench is a purpose-built benchmark that targets the simulation domain, offering structured prompts and tasks for evaluating LLM performance in generating and understanding FEA input files. It serves as a critical testbed for bridging the gap between symbolic physical language and numerical simulation. |

| CFD and Fluid Simulation |

OpenFOAM Cases [777] |

The OpenFOAM example case library provides a curated set of fluid dynamics simulation setups, widely used for training models to understand solver configuration, mesh generation, and boundary condition specifications in CFD contexts. |

| Material Property Retrieval |

MatWeb [778] |

MatWeb is a widely-used material database containing thermomechanical and electrical properties of thousands of substances. It plays an essential role in supporting downstream simulation tasks such as material selection, constitutive modeling, and multi-physics simulation setup. |

| Physics Modeling and PDE Learning |

PDEBench [779] PHYBench [780] |

PDEBench and PHYBench collectively advance the evaluation of LLMs in physical reasoning and numerical modeling. PDEBench focuses on classical PDEs like heat transfer, diffusion, and fluid flow in the context of scientific machine learning, while PHYBench introduces a broader spectrum of perception and reasoning tasks grounded in physical principles. Together, they support benchmarking across symbolic reasoning, equation prediction, and simulation-aware generation. |

| Fault Diagnosis and Health Monitoring |

NASA C-MAPSS [781] |

NASA C-MAPSS provides real-world time-series degradation data from turbofan engines, serving as a benchmark for predictive maintenance, anomaly detection, and reliability modeling in aerospace and mechanical systems. |

5.2.7. Benchmarks

In physics and mechanical engineering, tasks such as computer-aided design (CAD), finite element analysis (FEA), and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) are characterized by strong physical constraints, structured representations, and deep reliance on geometry or numerical solvers. The development of benchmarks to support LLMs in these domains is still in its infancy. Although recent datasets have enabled initial exploration of LLMs in these fields, they present multiple challenges with respect to scale, accessibility, and alignment with language-based modeling.

In the CAD domain, several large-scale datasets have been developed to support geometric learning and generative modeling. For example, the ABC Dataset [

773] provides over one million clean B-Rep (Boundary Representation) models, DeepCAD [

774] offers parameterized sketches for inverse modeling, and the Fusion 360 Gallery [

775] includes real-world design sequences from professional and amateur CAD users. However, most of these datasets represent geometry using numeric or parametric formats that lack symbolic or linguistic structure. Specifically, B-Rep trees and STEP files are low-level and require domain-specific parsers, making them difficult for LLMs to interpret or generate in a meaningful way.

While some recent efforts have attempted to represent CAD workflows through code-based formats such as FreeCAD Python scripts or Onshape feature code, these datasets are often small, sparse in supervision, and highly sensitive to syntactic or logical errors. Moreover, generating coherent and executable CAD programs remains a significant challenge due to the limited spatial reasoning capacity of current LLMs.

Recent advances, however, demonstrate that specialized instruction-to-code datasets and self-improving training pipelines can significantly improve LLM performance in CAD settings. For instance, BlenderLLM [

776] is trained on a curated dataset of instruction–Blender script pairs and further refined through self-augmentation. As shown in

Table 32, it achieves state-of-the-art results on the CADBench benchmark, outperforming models like GPT-4-Turbo and Claude-3.5-Sonnet across spatial, attribute, and instruction metrics, while maintaining a low syntax error rate. This indicates that domain-adapted LLMs, when paired with well-structured code-generation benchmarks, can overcome many of the geometric and syntactic limitations faced by general-purpose models.

To address these issues, several strategies can be explored. One direction involves decomposing full modeling workflows into modular sub-tasks, such as sketch creation, constraint placement, extrusion operations, and feature sequencing. This allows the LLM to focus on smaller, interpretable segments of the modeling pipeline. Another direction is to reframe CAD problems into geometric reasoning tasks—for instance, by translating design problems into 2D or 3D visual logic similar to those found in geometry exams. Prior studies have shown that LLMs such as GPT-4 perform surprisingly well on geometric puzzles when the problem is represented symbolically or visually. Furthermore, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) can be employed to provide contextual examples from past designs or sketches, thus improving generation quality through analogy-based learning. Overall, bridging the gap between high-dimensional geometric information and language representation remains a central challenge in CAD-focused LLM research.

Similarly, simulation-based tasks in FEA and CFD also require structured input generation, including mesh topology, material properties, solver settings, and boundary conditions. These tasks often involve producing complete simulation decks compatible with engines such as CalculiX or OpenFOAM, followed by interpreting complex field outputs such as stress distributions or velocity gradients.

Benchmarks such as FEABench [

? ] and curated OpenFOAM case libraries [

777] provide valuable baselines for evaluating the simulation-awareness of LLMs. However, the availability of large-scale paired datasets—comprising natural language descriptions, simulation input files, and corresponding numerical results—remains limited, posing a bottleneck for supervised fine-tuning and instruction-based evaluation.

To address this gap, FEABench introduces structured tasks that assess LLMs’ ability to extract simulation-relevant information.

Table 33 presents the performance of various LLMs across multiple physics-aware metrics, including interface factuality, feature recall, and dimensional consistency. Models like Claude 3.5 Sonnet and GPT-4o demonstrate strong results in retrieving factual and geometric descriptors, particularly in interface and feature extraction. However, all models show relatively low performance in recalling physical properties and structured feature attributes, reflecting ongoing challenges in capturing physical relationships from text. These results suggest that while LLMs can reliably recover high-level simulation inputs, deeper understanding of numerical structure and physical laws remains an open research problem.

A promising solution is to integrate LLMs with external numerical solvers in a simulator-in-the-loop framework. In this approach, an LLM is tasked with generating a complete simulation setup given a natural language prompt or design goal. The generated setup is then executed by a physics-based solver to produce ground-truth outputs. The input-output pairs, along with the original language prompt, can be stored as a triplet dataset and reused for supervised training. This method enables semi-automated dataset construction at scale, facilitates error correction via feedback from the simulator, and promotes the development of LLM agents that can reason across symbolic and physical domains. Additionally, by iterating through prompt refinement and result validation, such frameworks could enable reinforcement learning with human or physical feedback for high-fidelity simulation tasks.

Together, these benchmarks and emerging methodologies form the foundation of an evolving research area at the intersection of language modeling, geometry, and physics. As more domain-specific tools and datasets are adapted for LLM-compatible formats, we expect substantial progress in generative reasoning, simulation co-pilots, and data-driven modeling for engineering systems.

5.2.8. Discussion

Opportunities and Impact. LLMs are beginning to reshape workflows in physics and mechanical engineering, particularly in tasks such as CAD modeling, finite element analysis (FEA), material selection, simulation setup, and result interpretation. As demonstrated by models like CadVLM [

755] which translates textual input into parametric sketches, FEABench [

? ] which evaluates LLMs on FEA input generation, and LangSim [

768] which enables natural language interaction with atomistic simulation tools, LLMs are emerging as intelligent intermediaries between domain experts and computational tools.

By converting natural language into structured engineering commands, LLMs greatly simplify early-stage design, parameter exploration, technical documentation, and preliminary simulation configuration. Through code generation, auto-completion, document retrieval, and example-based prompting, LLMs are becoming integral assistants in modern engineering workflows. As multimodal and multi-agent systems (e.g., MechAgents [

753]) become more common, LLMs are poised to play a key role in the next generation of closed-loop “design–simulate–validate” engineering pipelines.

Challenges and Limitations. Despite these promising applications, multiple challenges persist. First, physical modeling tasks such as FEA and CFD involve highly coupled, nonlinear partial differential equations (PDEs) that require domain-specific inductive biases, numerical stability, and conservation principles—capabilities that current LLMs fundamentally lack.

Second, existing datasets in engineering domains present significant structural barriers. Most CAD datasets (e.g., B-Rep, STEP) are stored in numeric or parametric formats with minimal symbolic representation, making them difficult for LLMs to understand or generate. Code-based CAD datasets are more interpretable by LLMs, but are often limited in size, brittle in syntax, and sensitive to logical correctness.

Moreover, LLMs struggle with tasks requiring unit consistency, physical constraint enforcement, and boundary condition reasoning. In real-world engineering, even small errors in design parameters or simulation configurations can lead to system failure, safety risks, or structural inefficiencies. This makes it difficult to rely on LLMs for mission-critical design tasks without rigorous validation.

Research Directions. To further improve the effectiveness of LLMs in physics and mechanical engineering, several research directions are particularly promising:

Simulation-Augmented Dataset Generation. Integrating LLMs with numerical solvers in a simulator-in-the-loop framework allows the generation of language-input–simulation-output triplets at scale. This enables supervised training, fine-tuning, and RLHF strategies grounded in physically valid feedback.

Task Decomposition and Geometric Reformulation. Decomposing CAD workflows into modular sub-tasks (e.g., sketching, constraints, extrusion) and reformulating modeling problems as geometric reasoning tasks can align better with LLM capabilities and improve interpretability.

Multimodal and Multi-agent Integration. Developing LLM systems that can call CAD tools, solvers, and databases autonomously—as seen in MechAgents or LangSim—will allow LLMs to reason, plan, and act across tools in complex design and simulation pipelines.

Standardized Benchmarks and Evaluation. Creating large-scale, task-diverse, and format-unified benchmark datasets (e.g., combining natural language prompts, simulation files, and result summaries) will accelerate model evaluation and fair comparison in this field.

Physics Validation and Safety Assurance. Embedding physical rule checkers and verification mechanisms into generation loops can help enforce unit consistency, structural validity, and simulation compatibility, ensuring that outputs are not just syntactically correct but physically plausible.

Conclusion. LLMs are becoming increasingly valuable assistants in physics and mechanical engineering, especially in peripheral tasks such as documentation, concept generation, parametric modeling, and simulation support. However, to deploy them in core workflows, future systems must integrate LLMs with symbolic reasoning, geometric logic, physics-based solvers, and expert feedback. This synergy will enable the transition from language-based assistance to trustworthy, intelligent co-creation in complex engineering design and modeling workflows.

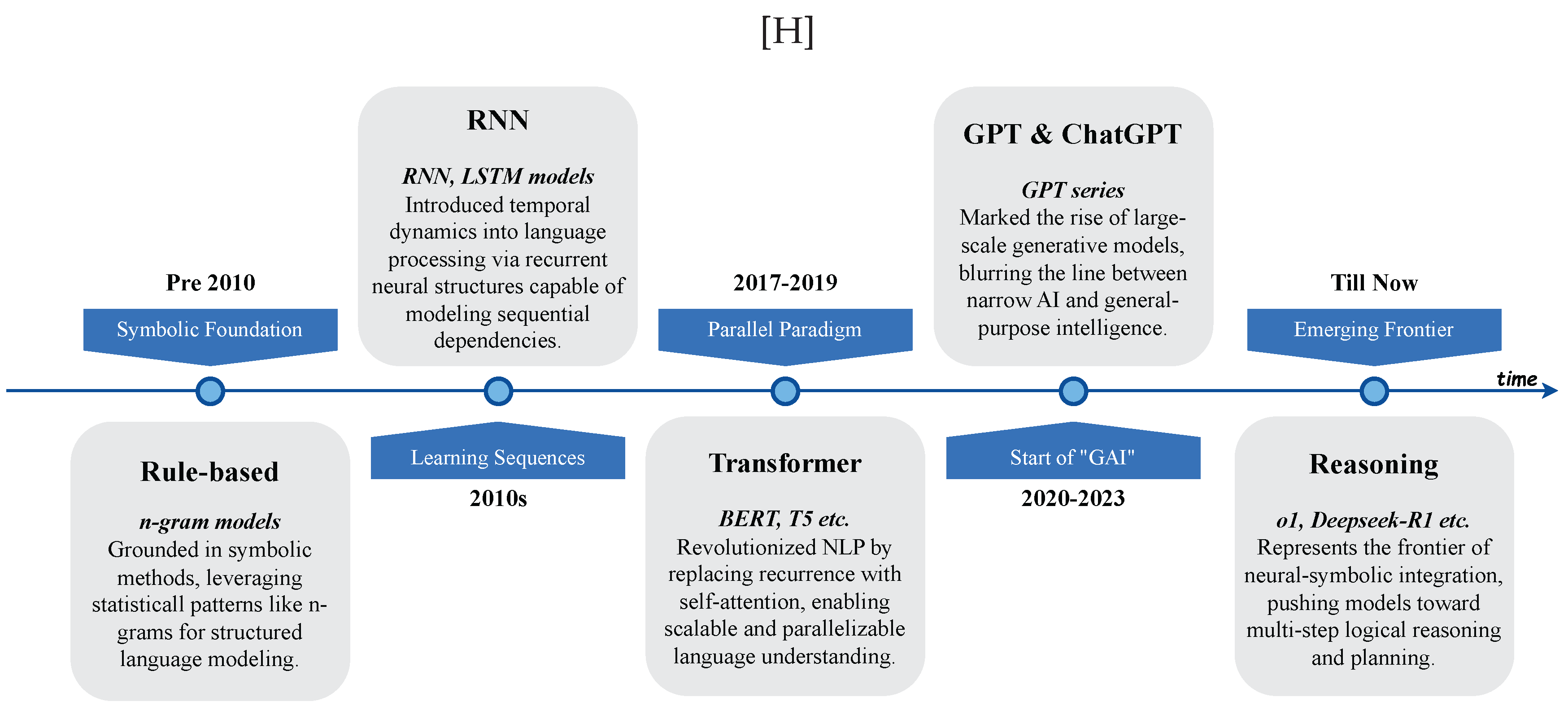

5.3. Chemistry and Chemical Engineering

5.3.1. Overview

5.3.1.1 Introduction to Chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific discipline dedicated to understanding the properties, composition, structure, and behavior of matter. As a branch of the physical sciences, it focuses on the study of chemical elements and the compounds formed from atoms, molecules, and ions—their interactions, transformations, and the principles governing these processes [

782,

783].

Put simply, chemistry seeks to explain how matter behaves and how it changes [

784]. We must acknowledge that the field of chemistry is vast and encompasses a variety of branches. Given the particularly rich application scenarios in areas such as organic chemistry, life sciences—especially in relation to LLM-related work—we will discuss these branches in the following chapter to provide a detailed introduction to works closely related to biology and life sciences.

In the field of chemistry, there are numerous sub-tasks, and many scientists have made significant contributions and achieved groundbreaking results over the past few hundred years.

Before diving into LLM-related topics, we would like to provide an overview of major tasks and traditional methods in chemistry research. By integrating information from official websites [

785] and literature across various branches of the field [

786,

787,

788,

789,

790,

791,

792,

793,

794,

795], we have summarized the research tasks in the domain of chemistry as follows:

Analysis and Characterization. This task involves identifying the substances present in a sample (qualitative analysis) and determining the quantity of each substance (quantitative analysis) [

796]. In this section we emphasize experimental measurement and detection methods aimed at identifying which substances are present, as well as determining their composition, structure, and morphology; we do not here focus on how their properties change under varying conditions nor on prediction or modeling of those properties. It also includes elucidating the structure and properties of these substances at a molecular level [

797]. Traditional methods for analysis and characterization include techniques such as observing physical properties (color, odor, melting point), performing specific chemical tests to identify certain substances (like the iodine test for starch or flame tests for metals), and classical quantitative analysis using precipitation, extraction, and distillation [

798]. Modern research in this area heavily relies on sophisticated instruments. Spectroscopy, which studies how matter interacts with light, can provide significant insights into a molecule’s structure and composition [

797]. Chromatography is employed to separate complex mixtures into their individual components for analysis [

797]. Mass spectrometry (MS) is a powerful technique that can identify and quantify substances by measuring their mass-to-charge ratio with very high sensitivity and specificity [

797,

799].

Research on Properties. Research on properties in chemistry refers to the systematic exploration and analysis of the physical and chemical characteristics of substances, with the main objective being to reveal the behavior and reaction characteristics of substances under different conditions [

800,

801]. We take “Research on Properties” to include both experimental determination and prediction or modeling of physical and chemical properties, with a primary interest in how those properties behave or change under different conditions. Traditionally, researchers have employed experimental methods to determine these properties. For thermodynamic properties, calorimetry is a key technique used to measure heat flow during physical and chemical processes [

802,

803]. Equilibrium methods, such as measuring vapor pressure, can assist in determining energy changes during phase transitions [

802]. For kinetic properties, traditional methods involve monitoring the changes in concentration of reactants or products over time [

804].

Reaction Mechanisms. The primary objective of studying reaction mechanisms in chemistry is to reveal the specific processes and steps involved in chemical reactions, including the microscopic mechanisms by which reactants are converted into products. This research field focuses on the formation of various intermediates during the reaction, the reaction pathways, rate-determining steps, and their corresponding energy changes [

800,

805]. Traditional methods for investigating reaction mechanisms include kinetic studies, where the rate of a reaction is measured under different conditions to understand its progression [

806,

807,

808]. Isotopic labeling involves using reactants with specific isotopes to trace the movement of atoms during the reaction [

807]. Stereochemical analysis examines the spatial arrangement of atoms in reactants and products, providing insights into the reaction pathway [

807]. Identifying the intermediate products formed during the reaction is also a crucial aspect of this research.

Chemical Synthesis. Chemical Synthesis refers to actually producing molecules in the laboratory or pilot-scale. The synthesis of natural products is an important task in chemistry, aimed at using chemical methods to synthesize complex organic molecules found in nature [

809]. The realization of such synthesis in practice relies on several traditional experimental methods. Plant extraction separates compounds from plants using techniques like solvent extraction, cold pressing, or distillation, yielding various active ingredients. Fermentation technology utilizes microorganisms to produce natural products, commonly for antibiotics and bioactive substances [

810]. Organic synthesis constructs chemical structures through multi-step synthesis and the introduction of functional groups [

811]. Lastly, semi-synthetic methods modify simple precursors to create more complex natural compounds or their derivatives [

812].

Molecule Generation. Molecule Generation involves computational chemistry and molecular modeling techniques to predict, optimize, or generate new molecular structures with desired functions or properties [

813,

814]. It includes computer-aided design, virtual screening, property prediction, structure optimization, and theoretical modelling of molecules, etc. [

813,

814]. Molecular synthesis and design encompass both experimental synthesis [

814] and computer-aided design [

815].

Applied Chemistry. Applied Chemistry refers to the branch of chemistry that focuses on practical applications in various fields such as industry, medicine, and environmental science. It involves using chemical principles to solve real-world problems and improve processes, including material chemistry and drug chemistry [

816,

817,

818,

819]. Traditionally, several key methods are relied upon, including structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies, computer-aided drug design [

820], high-throughput screening [

821], and synthetic chemistry [

822].

5.3.1.2 Introduction to Chemical Engineering

Chemical engineering is an engineering field that deals with the study of the operation and design of chemical plants, as well as methods of improving production. Chemical engineers develop economical commercial processes to convert raw materials into useful products. Chemical engineering utilizes principles of chemistry, physics, mathematics, biology, and economics to efficiently use, produce, design, transport, and transform energy and materials [

823]. According to the Oxford Dictionary,

chemical engineering is a branch of engineering concerned with the application of chemistry to industrial processes, particularly involving the design, operation, and maintenance of equipment used to carry out chemical processes on an industrial scale [

824]. In summary, it serves as the bridge that applies chemical achievements to industry.

Similar to chemistry, chemical engineering encompasses multiple fields, including not only chemistry, but also mathematics, physics, and economics. Through a comprehensive review of previous research [

825,

826,

827,

828,

829], we have categorized the tasks in chemical engineering into the following types.

Chemical Process Engineering. Chemical process engineering includes chemical process design, improvement, control, and automation. Chemical process design focuses on the design of reactors, separation units, and heat exchange equipment to achieve efficient material conversion and energy utilization [

827,

830], typically employing computer-aided design software and process simulation tools [

831,

832]. Chemical process improvement involves the systematic analysis and optimization of existing chemical processes to enhance production efficiency, reduce resource consumption, and minimize environmental impact [

830]. It primarily relies on quality management tools [

833,

834] and process simulation software [

835]. Process control and automation aim to monitor and regulate chemical processes through control systems to ensure stable operation under set conditions, typically based on proportional–integral–derivative (PID) control systems [

836], combined with advanced control technologies such as Model Predictive Control [

837] to optimize processes. Distributed control systems and programmable logic controllers are also commonly used automation systems that can monitor and adjust process variables in real-time [

838,

839].

Equipment Design and Engineering. Equipment design and engineering focus on the design, selection, and maintenance of chemical engineering equipment to ensure its efficient and safe operation within specific processes. The reliability and functionality of the equipment directly impact overall efficiency and safety [

840]. Equipment design is typically carried out in accordance with industry standards and regulations, such as American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) and American Petroleum Institute (API). Engineers use computer-aided design (CAD) software for detailed design and simulation [

841,

842]. Additionally, strength analysis and fluid dynamics simulation are critical components, generally relying on computational fluid dynamics software to ensure the safety and efficiency of equipment under various operating conditions [

840].

Sustainability and Environmental Engineering. Sustainability and environmental engineering focus on the impact of chemical processes on the environment and are dedicated to developing green chemical technologies to reduce pollution and resource consumption. This field emphasizes the importance of life cycle assessment and environmental impact assessment in achieving sustainability goals [

843].

Scale-up and Technology Transfer. The task of translating chemical achievements into practical applications in chemical engineering involves bridging the gap between laboratory discoveries and industrial-scale implementation, ensuring that innovative chemical processes and materials are effectively integrated into real-world production systems to meet societal and industrial demands [

844]. Traditionally, the application of chemical achievements employs methods such as pilot scale testing to validate the feasibility and stability of the technology [

844], and process simulation and optimization (e.g., using tools like Aspen Plus and CHEMCAD) to model and optimize process flows, thereby reducing costs and improving efficiency. Simultaneously, factors such as economic viability, supply chain and market dynamics, and safety and environmental compliance are also evaluated and optimized [

825,

827].

From the definition, we can see that there is a strong logical relationship between the fields of chemical engineering and chemistry at the macroscopic level. The main battleground of chemical science is in the laboratory, while the main battleground of chemical engineering is in the factory. Chemical engineering aims to translate processes developed in the lab into practical applications for the commercial production of products, and then work to maintain and improve those processes [

782,

783,

823,

845].

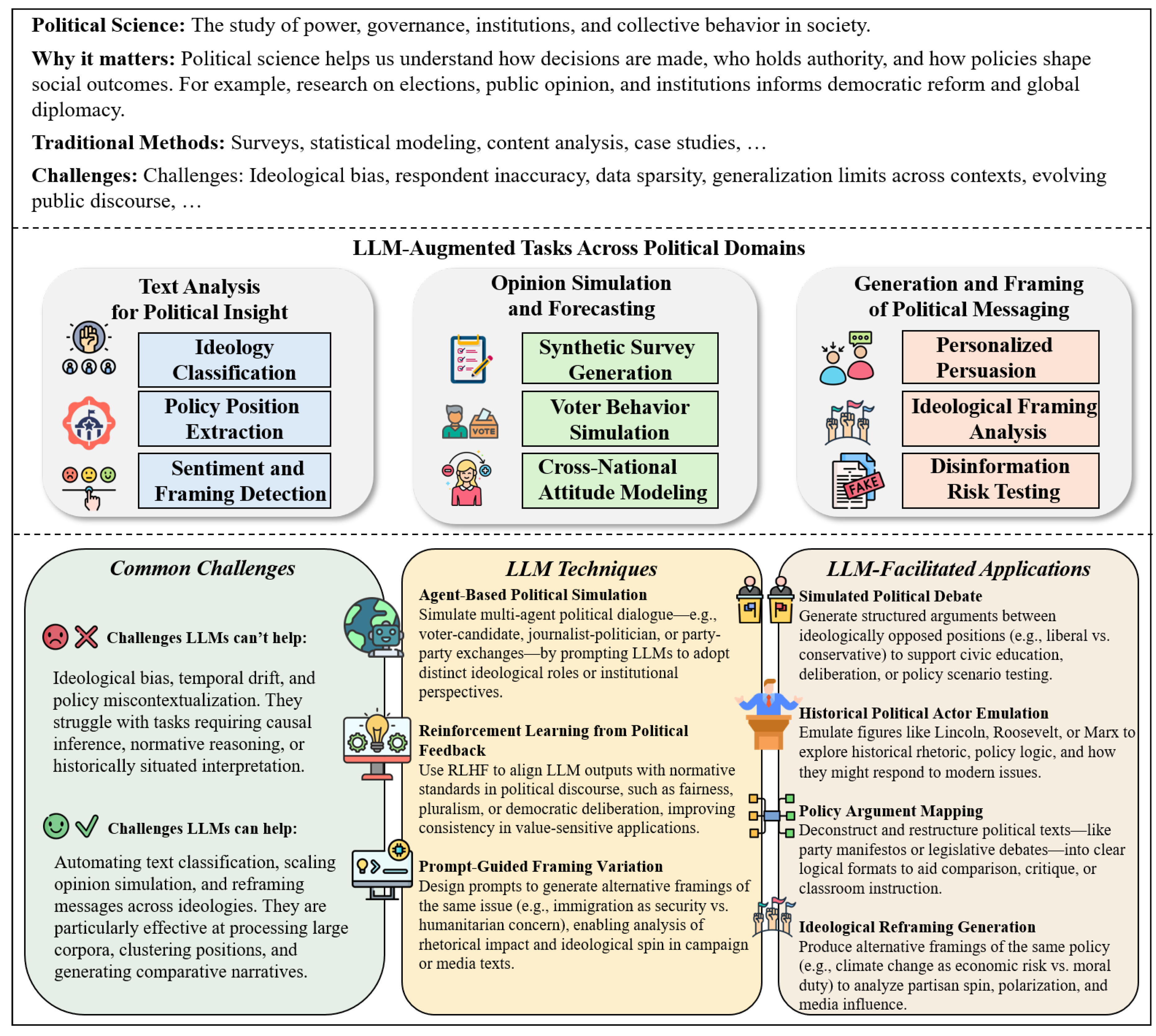

At the microscopic level, chemistry and chemical engineering share many common technologies, such as CAD and computational simulation. Moreover, there are varying degrees of connections between the different sub-tasks within these two fields. We have summarized the relationships among them in the form of a diagram in

Figure 17.

5.3.1.3 Contribution of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering

It is not difficult to imagine that chemistry, as a fundamental science, has profoundly impacted various aspects of human society, with its contributions evident in public health, materials innovation, environmental protection, and energy transition. Firstly, the contributions of chemistry to public health are significant. Through the synthesis and development of new pharmaceuticals, chemists have greatly improved human health [

846,

847]. For instance, the discovery of penicillin not only marked the beginning of the antibiotic era but also reduced the mortality risk associated with bacterial infections [

846,

848]. In recent years, the development of targeted therapies [

847,

849], such as drugs aimed at specific cancers, relies on a chemical understanding of the internal mechanisms of tumor cells, thereby significantly enhancing patient survival rates. Secondly, chemistry has a revolutionary impact on materials innovation. Through the development of polymers [

850], alloys [

851,

852], and nanomaterials [

853,

854], chemists have not only enhanced material properties but also advanced technological progress. For example, the application of modern lightweight and high-strength composite materials has enabled greater energy efficiency and safety in the aerospace and automotive industries [

850]. Moreover, the emergence of graphene and other nanomaterials has opened new possibilities for the development of electronic products [

853,

854].

In the realm of environmental protection, the contributions of chemistry cannot be overlooked. By developing efficient catalysts and clean technologies, chemists play a crucial role in reducing industrial emissions and tackling water pollution [

855]. For example, selective catalytic reduction reactions effectively convert harmful gases emitted by vehicles, significantly improving urban air quality [

856,

857]. Furthermore, the role of chemistry in energy transition is becoming increasingly important [

858,

859]. The development of renewable energy storage and conversion is fundamentally supported by chemical technologies [

860]. For instance, the research and development of lithium-ion batteries [

861] and hydrogen fuel cells [

862] depend on the optimization of chemical reactions and material innovations, making the use of clean energy feasible.

5.3.1.4 Challenges in the Era of LLMs

Despite the significant achievements in the fields of chemical science and chemical engineering, there remain unresolved challenges in these areas. The emergence of LLMs presents an opportunity to address these issues. We must acknowledge that, unfortunately, LLMs are not omnipotent; they cannot solve all the challenges within this field. However, for certain tasks, LLMs hold promise in assisting chemists in overcoming these challenges. We have listed the following difficulties that LLMs cannot solve:

The Irreplaceability of Time-consuming Chemical Experiments. LLMs-generated outcomes in chemical research still require experimental validation. Assessing the true utility of these generated molecules, such as evaluating their novelty in real-world applications, can be a time-consuming undertaking [

863]. While LLMs have their advantages in data processing and information retrieval, solely relying on the results generated by the model may not accurately reflect the actual experimental conditions. Moreover, LLMs are trained on existing data and literature; if a specific field lacks sufficient data support, the outputs of the model may be inaccurate or unreliable [

864].

Limitations in Learning Non-smooth Patterns. Traditional deep learning struggles to learn non-smooth target functions that map molecular data to labels, as these target functions are frequently non-smooth in molecular property prediction. This implies that minor alterations in the chemical structure of a molecule can lead to substantial changes in its properties [

865]. Additionally, LLMs also find it difficult to solve this problem under the limited size of molecular datasets.

Dangerous Behaviors and Products. The field of chemistry carries certain inherent risks, as some products or reactions can be hazardous (e.g., flammable, explosive, toxic gases, etc.). LLMs may generate scientifically incorrect or unsafe responses, and in some cases, they may encourage users to engage in dangerous behavior [

866]. Furthermore, LLMs can also be misused to create toxic or illegal substances [

863]. At the current stage of development, LLMs still cannot be fully trusted to ensure complete reliability.

On the other hand, despite the aforementioned limitations, the potential of LLMs in the fields of chemistry and chemical engineering is undeniable, as they hold promise in addressing many challenges:

Decrease the Vast Chemical Exploration Space. Inverse design enables the creation of synthesizable molecules that meet predefined criteria, accelerating the development of viable therapeutic agents and expanding opportunities beyond natural derivatives [

867]. However, this quest faces a combinatorial explosion in the number of potential drug candidates—the chemical space made up of all small drug-like molecules—which is unimaginably large (estimated at

) [

867]. Testing any significant fraction of these molecules, either computationally or experimentally, is simply impossible [

868]. This field has been revolutionized by machine learning methods, particularly generative models, which narrow down the search space and enhance computational efficiency, making it possible to delve deeply into the seemingly infinite chemical space of drug-like compounds [

869]. LLMs, such as MolGPT [

870], which employs an autoregressive pre-training approach, have proven to be instrumental in generating valid, unique, and novel molecular structures. The emergence of multi-modal molecular pre-training techniques has further expanded the possibilities of molecular generation by enabling the transformation of descriptive text into molecular structures [

871].

Generation of 3D Molecular Conformations. Generating three-dimensional molecular conformations is another significant challenge in the field of molecular design, as the three-dimensional spatial structure of a molecule profoundly impacts its chemical properties and biological activity. Traditional computational methods are often resource-intensive and time-consuming, making it difficult for researchers to design and screen new drugs effectively. Unlike conventional approaches based on molecular dynamics or Markov chain Monte Carlo, which are often hindered by computational limitations (especially for larger molecules), LLMs based on 3D geometry exhibit remarkable superiority in conformation generation tasks, as they can capture inherent relationships between 2D molecules and 3D conformations during the pre-training process [

871].

Automate Chemical Agents. Autonomous chemical agents combine LLM “brains” with planning, tool use, and execution modules to carry out experiments end-to-end. In the coscientist system, for example, GPT-4 first decomposes a high-level goal (“optimize a palladium-catalyzed coupling”) into sub-tasks (reagent selection, condition screening), retrieves relevant literature via a search tool, generates executable Python code for liquid-handling robots, and then interprets sensor feedback to iteratively refine the protocol—closing the loop between design and execution [

872]. Similarly, Boiko et al. built an agent that plans ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy (UV–Vis) experiments by writing code to control plate readers and analyzers, automatically processing spectral data to identify optimal wavelengths, and even adapting to novel hardware modules introduced after the model’s training cutoff [

873]. By leveraging LLMs for hierarchical task decomposition, self-reflection, tool invocation (e.g., search APIs, code execution, robotics control), and memory management, these systems drastically accelerate repetitive experimentation and free researchers to focus on hypothesis generation rather than manual protocol execution [

873].

Enhance Understanding of Complex Chemical Reactions. The field of reaction prediction faces several key challenges that affect the accuracy of forecasting chemical reactions. A significant issue is reaction complexity, stemming from multi-step pathways and dynamic intermediates, which complicates product predictions, especially with varying conditions like different catalysts. Traditional models often struggle with these complexities, leading to biased outcomes. Utilizing advanced transformer architectures, LLMs can model complex relationships in chemical reactions and adjust predictions based on varying conditions. They excel in learning from unlabeled data through self-supervised pretraining, helping identify patterns in chemical reactions, particularly useful for rare reactions.

Multi-task Learning and Cross-domain Knowledge. The complexity of multi-task learning makes the simultaneous optimization of diverse prediction tasks difficult, while LLMs effectively handle this via shared representations and multi-task fine-tuning [

874]. Traditional methods also struggle to integrate cross-domain knowledge from chemistry, biology, and physics, yet LLMs address this seamlessly through pre-training and knowledge graph enhancement.

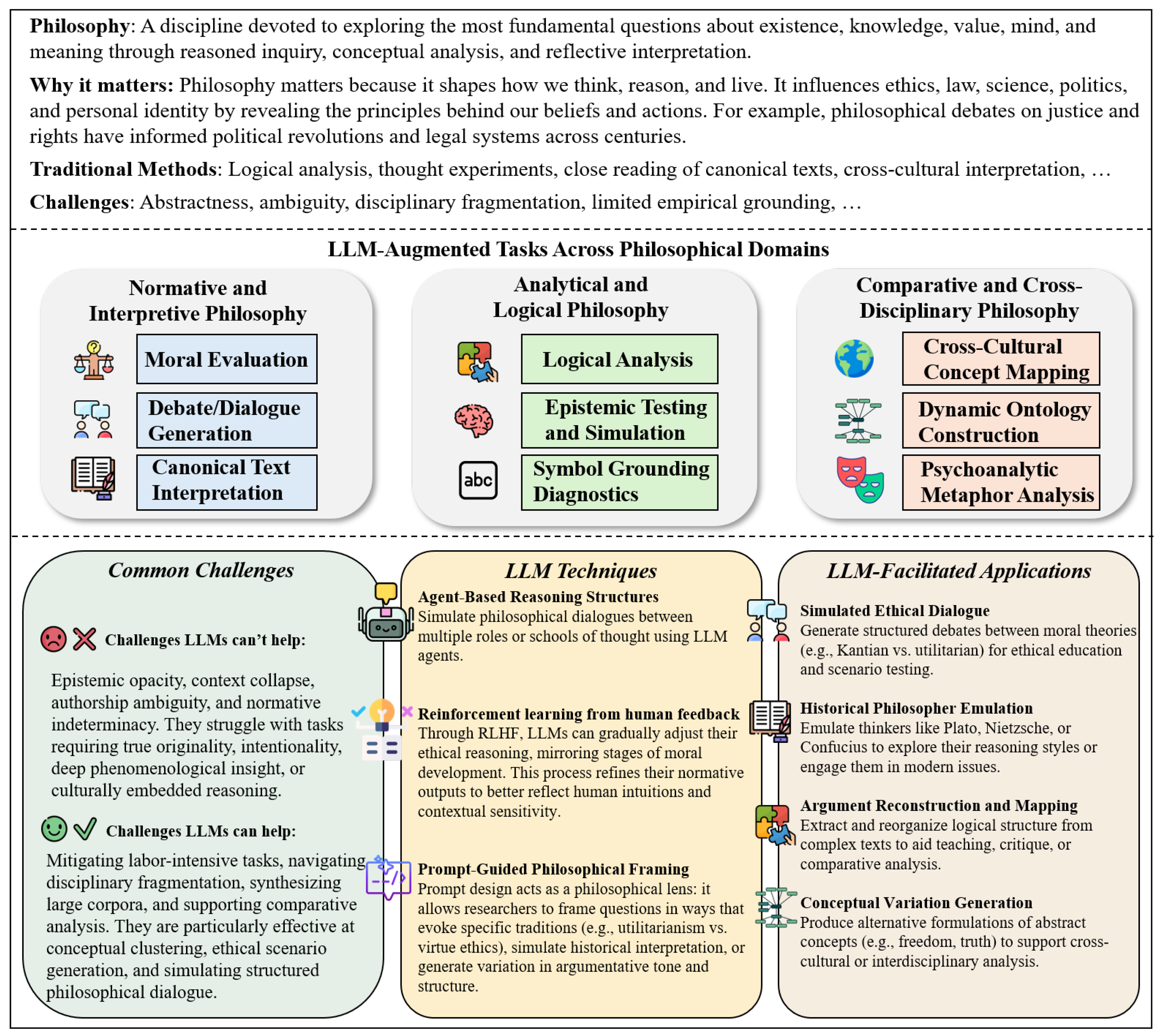

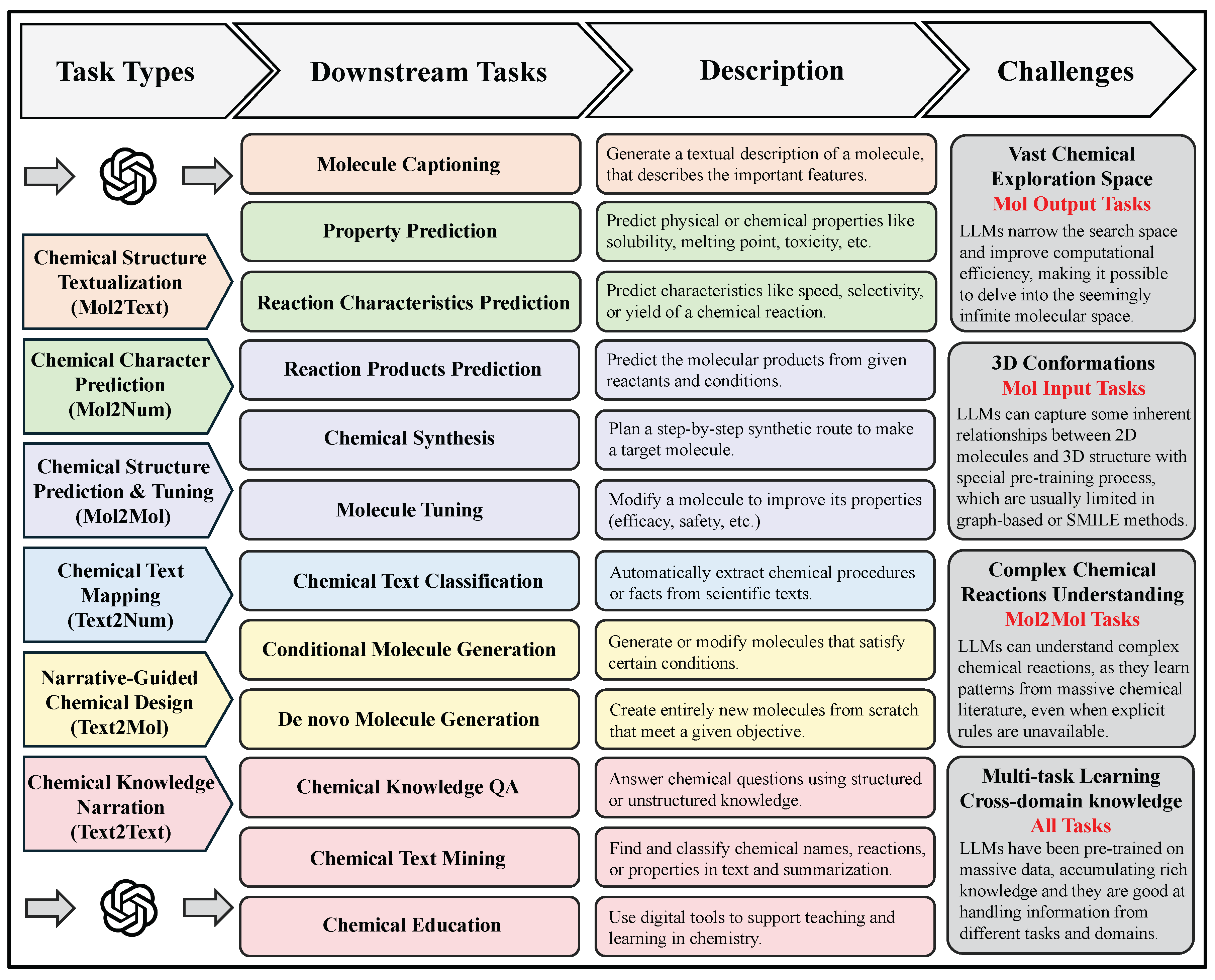

5.3.1.5 Taxonomy

As summarized in

Table 34, in efforts to integrate chemistry research with artificial intelligence, particularly LLMs, many chemists primarily focus on tasks such as property prediction, property-directed inverse design, and synthesis prediction [

867,

874,

875]. However, other chemists highlight additional significant tasks, including data mining and predicting synthesis conditions [

876,

877]. By synthesizing insights from these studies along with other seminal works [

878,

879,

880], we propose a more comprehensive classification method. This method accounts for both the rationality of chemical task classification and the characteristics of computer science.

From the chemistry perspective, our taxonomy echoes the field’s established research divisions—such as molecular property prediction, property-directed inverse design, reaction type and yield prediction, synthesis condition optimization, and chemical text mining—ensuring that each category corresponds directly to a recognized experimental or theoretical task in chemical science. Concurrently, from the computer science perspective, by mapping every task onto a unified input–output modality framework, we add a computationally consistent structure that facilitates model development, benchmarking, and comparative analysis across diverse tasks within a single formal paradigm. Together, these dual alignments guarantee that our classification remains both chemically and algorithmically meaningful.

Figure 18.

A taxonomy of chemical tasks enabled by LLMs, categorized by input-output types and downstream objectives.

Figure 18.

A taxonomy of chemical tasks enabled by LLMs, categorized by input-output types and downstream objectives.

Chemical Structure Textualization. Chemical structure textualization is the process of taking a molecule’s SMILES sequence as input and producing a detailed textual depiction that highlights its structural features, physicochemical properties, biological activities, and potential applications. Here, SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) encodes a molecule’s atomic composition and connectivity as a concise, linear notation—for example, “CCO” denotes ethanol (each “C” represents a carbon atom and “O” an oxygen atom), while “C1=CC=CC=C1” represents benzene (the digits mark ring closure and “=” indicates double bonds)—enabling computational models to capture meaningful structural patterns and relationships for downstream text generation. Subtasks include molecule captioning, which exemplifies the goal of generating rich, human-readable descriptions of molecules to give chemists and biologists rapid, accessible insights for experimental design and decision-making [

881].

Chemical Characteristics Prediction. Nowadays, SMILES provides a standardized method for encoding molecular structures into strings [

882]. This string-based representation enables efficient parsing and manipulation by computational models and underpins a variety of tasks in cheminformatics, drug discovery, and reaction prediction. Notably, many machine learning models, including large-scale language models like GPT, are pre-trained or fine-tuned using corpora of SMILES sequences. Among the tasks leveraging SMILES input are property prediction and reaction characteristics prediction, where the model takes a SMILES sequence as input and outputs numerical values, categorical labels, or multi-dimensional vectors representing chemical properties, reactivity, bioactivity, and other experimentally relevant quantities.

Chemical Structure Prediction & Tuning. Chemical structure prediction & tuning tasks represent a classical form of sequence-to-sequence modeling [

883], where the goal is to transform an input molecular sequence into an output sequence. In chemistry, this formulation is particularly intuitive because molecules are often represented as SMILES strings, which encode structural information in a linear textual format. Given an input SMILES sequence, the model learns to generate another SMILES string corresponding to a chemically meaningful transformation. This input–output structure underlies a variety of chemical modeling tasks, including reaction product prediction, chemical synthesis planning, and molecule tuning. For instance, the input may describe reactants or precursors, and the output may represent reaction products or structurally modified molecules, making these tasks central to computational reaction modeling and automated molecular design.

Chemical Text Mapping. Chemical text mapping tasks refer to the process of transforming unstructured textual input into numerical outputs such as labels, scores, or categories. At their core, these tasks involve analyzing chemical text—ranging from scientific articles to experimental protocols—and mapping the extracted information to structured numerical values for downstream applications like classification, relevance scoring, or trend prediction [

867,

884]. A typical example is document classification, where the input is natural language text and the output is a discrete or continuous number representing, for example, a document’s category or relevance score. These tasks enable scalable analysis of chemical literature and facilitate integration of textual knowledge into data-driven modeling workflows.

Narrative-Guided Chemical Design. Narrative-Guided chemical design is a generative modeling paradigm extensively applied in chemistry and materials science, with the core objective of deriving molecular structures or material candidates that fulfill specific target properties or functional requirements [

885,

886]. Unlike conventional forward design—which predicts properties from a given structure—inverse design begins with the desired outcome and works backward to propose compatible structures. In this context, the input is a description of the target properties, which may take the form of numerical constraints, categorical labels, or free-text descriptions, and the output is a molecular structure—typically represented as a SMILES string—that satisfies those specified criteria. This framework encompasses tasks such as de novo molecule generation and conditional molecule generation, enabling applications like targeted drug design, property-driven material discovery, and personalized molecular synthesis.

Chemical Knowledge Narration. Chemical knowledge narration tasks in chemistry refer to the transformation of one form of textual input into another, with both input and output grounded in chemical knowledge and language use [

867]. These tasks leverage Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques to process, convert, or generate chemistry-related textual data, thereby facilitating a range of downstream applications in research, education, and industry. For instance, given a textual input such as a paragraph from a research paper, the model may extract key information, translate it into another language, generate a summary, or answer domain-specific questions. Such tasks—encompassing chemical text mining, chemical knowledge question answering, and educational content generation—typically operate on natural language input and produce human-readable textual output, making them essential tools for improving access to and understanding of chemical information.

Table 34.

Chemistry Tasks, Subtasks, Insights and References

Table 34.

Chemistry Tasks, Subtasks, Insights and References

| Type of Task |

Subtasks |

Insights and Contributions |

Key Models |

Citations |

| Chemical Structure Textualization |

Molecular Captioning |

LLMs, by learning structure–property patterns from data, generate meaningful molecular captions, thus improving interpretability and aiding chemical understanding. |

MolT5: generates concise captions by mapping substructures to descriptive phrases; MolFM: uses fusion of molecular graphs and text for richer narrative summaries. |

[887,888,889,890,891,892,893,894,895,896,897,898,899,900,901,902,892] |

| Chemical characteristics prediction |

Property Prediction |

LLMs, by capturing complex structure–property relationships from molecular representations, enable accurate property prediction, thereby providing mechanistic insights and guiding the rational design of molecules with desired functions. |

SMILES-BERT: self-supervised SMILES pretraining for robust property inference; ChemBERTa: masked SMILES modeling boosting solubility and toxicity predictions. |

[903,904,905,906,907,908,909,910,911,912,913,914] |

| |

Reaction Characteristics Classification |

LLMs, by modeling the relationships between reactants, conditions, and outcomes from large reaction datasets, can accurately predict reaction types, yields, and rates, thereby uncovering hidden patterns in chemical reactivity and enabling chemists to optimize reaction conditions and select efficient synthetic routes with greater confidence. |

RXNFP: fingerprint-transformer accurately classifies reaction types; YieldBERT: fine-tuned on yield data to predict experimental yields within 10% error. |

[863,915,916,917,918,919,920,921,922,923,924,925,926,927] |

| Chemical Structure Prediction & Tuning |

Reaction Products Prediction |

LLMs, by learning underlying chemical transformations from reaction data, can accurately predict reaction products, thus uncovering implicit reaction rules and supporting more efficient and informed synthetic planning. |

Molecular Transformer: state-of-the-art SMILES-to-product translation; |

[921,923,924,925,926,928,929,930,931,932,933] |

| |

Chemical Synthesis |

LLMs, by capturing patterns in reaction sequences and chemical logic from large datasets, can suggest plausible synthesis routes and rationales, thereby enhancing human understanding of synthetic strategies and accelerating discovery. |

Coscientist: GPT-4-driven planning and robotic execution. |

[872,932,934,935,936,937,938,939,940,941,942,943,944,945,946,947,948,949,950,951] |

| |

Molecule Tuning |

LLMs, by modeling structure–property relationships across diverse molecular spaces, enable targeted molecule tuning to optimize desired properties, thereby providing insights into molecular design and accelerating the development of functional compounds. |

DrugAssist: uses LLM prompts for ADMET property optimization; ControllableGPT: enables constraint-based molecular modifications. |

[952,953,954,955,956,957,958,959,960,961,962,963,964,964] |

| Chemical Text Mapping |

Chemical Text Mining |

LLMs, by capturing semantic and contextual nuances in chemical literature, enable accurate classification and regression in text mining tasks, thereby uncovering trends, predicting research outcomes, and transforming unstructured texts into actionable scientific insights. |