1. Introduction

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the non-clinical factors that influence health outcomes in relation to the environment, society, and cultural contexts. They encompass the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. Recognized domains of SDOH are housing quality, education, employment, access to healthy food, transportation, social environments, and healthcare services. These interconnected determinants contribute to health inequalities, disproportionately burdening poor and marginalized populations [

1,

2]. According to the World Health Organization, SDOH account for between 30% and 55% of health outcomes globally, making them one of the strongest predictors of premature mortality and inequity [

3].

Environmental science traditionally examines the interactions between natural systems and anthropogenic activities, including pollution, ecosystem health, water and air quality, land use, and climate systems. It provides key information on how pollutants in all three spheres, i.e., in air, water, and soil, penetrate living environments and subsequently the human body, and how they impact biological systems. It also examines how industrialization, urban planning, and energy consumption generate feedback loops that affect both ecosystems and human health over time [

4,

5]. Recent estimates show that environmental and occupational risk factors contribute to 18.9% of global deaths (12.8 million annually) and 14.4% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), with air pollution alone accounting for more than 4 million deaths per year [

6,

7].

However, despite abundant evidence of their intersection, public health research and environmental science have been mostly treated as parallel rather than integrated pathways. This paper argues that environmental exposures must be embedded within the SDOH framework to fully understand and address public health inequities.. Communities in degraded environments characterized by polluted air, contaminated water, and substandard housing face environmental stressors that compound existing socioeconomic vulnerabilities [

8,

9]. These stressors are not distributed equally; they follow lines of structural inequality, zoning bias, and environmental racism [

10].

Consequently, an interdisciplinary approach that includes public health practitioners, environmental scientists, urban planners and policymakers is vital to addressing the underlying determinants of health inequities. Each discipline contributes distinct tools such as epidemiological surveillance, environmental risk modelling, urban design strategies, and regulatory frameworks that together enhance our capacity to identify and reduce health inequities [

11,

12]. This paper explicitly positions itself as bridging the systems frameworks of environmental science (e.g., ecosystems, pollution, energy, and land use units in AP Environmental Science) with justice-oriented public health equity models such as Healthy People 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While most existing research remains siloed, this work introduces an applied interdisciplinary framework designed to inform both education and policy.

This paper investigates how central environmental science themes, including air and water pollution, toxic exposure, waste management, and climate change, intersect and amplify diverse SDOH domains. Drawing on environmental curricula and contemporary public health research, this paper develops an interdisciplinary conceptual framework that links environmental literacy with SDOH to guide equity-based policy approaches. By situating environmental hazards within the larger fabric of structural determinants, this paper highlights the critical need for an integrative, tech-enabled model of health disparities along with corresponding solutions. In doing so, it also looks forward to emerging tools such as AI-driven platforms (e.g., NurseAI) and community-based decision support systems that can operationalize this interdisciplinary integration for both public health practice and environmental education.

This paper offers a unique contribution by bridging pedagogy and practice. The framework emerged from my dual perspective as a student in AP Environmental Science and as a healthcare technology innovator. In class, I studied ecological systems, pollution, and resource management; through my work developing NurseAI, I explored how nurses identify and respond to social determinants of health in real time. By combining these experiences, this work develops an interdisciplinary synthesis that positions environmental factors not only as academic content but as actionable determinants within healthcare delivery. This dual lens classroom learning applied through technology design distinguishes this work from existing reviews and demonstrates how educational frameworks can inform applied health equity strategies.

2. Conceptual Framework: Linking Environment Science and SDOH

Although their intersections are increasingly recognized, social determinants of health (SDOH) and environmental science have traditionally developed in disciplinary silos. Traditional SDOH models often emphasize proximal social conditions (e.g., education, income, housing, healthcare access) while failing to systematically account for environmental degradation, toxic exposures, or ecological decline. Conversely, environmental science emphasizes physical systems such as pollution dynamics and resource use while giving limited attention to the social and political mechanisms that distribute environmental risks across populations [

4,

8].

This disciplinary divide has stifled the development of holistic models that incorporate the range of factors affecting human health. In response, scholars have advocated for integrative models that conceptualize environmental exposures and structural determinants as interrelated processes to better capture cumulative health risks. For instance, the Social Exposure conceptual model includes psychosocial, economic, and physical environmental exposures throughout the life course, while also highlighting the importance of timing, duration, and the combination of exposure types in the context of the significantly relevant health outcomes [

9]. The

Salutogenic Environmental Health Model (SEHM) also provides an interdisciplinary perspective emphasizing those environmental resources alongside stressors, collectively influence health and well-being development across contexts [

5].

Real-world applications of these integrative frameworks are increasingly visible in environmental health research. For example, a 20-year longitudinal study demonstrated that cumulative risk indices combining multiple social and environmental exposures predicted diverse outcomes such as depression, school dropout, and chronic illness, with early-life exposures explaining variance in outcomes beyond later exposures [

13]. Similarly, Bayesian mixture models such as the Low-Rank Kriging Multiple Membership Model (LRK-MMM) have been applied to identify spatial clusters of pesticide exposures and associated cancer risks, providing quantitative evidence of how exposures interact and accumulate [

14]. Other work has merged Aggregate Exposure Pathways (AEP) with Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOP) to model perchlorate toxicity across twelve species, illustrating the translational power of integrated frameworks for both human and ecological health [

15].

Various key conceptual tools are specifically important for linking environmental science with SDOH. The first is embodiment, the process through which social and environmental exposures are biologically embedded, influencing physiology, disease risk, and long-term health trajectories. For example, long-term exposure to airborne pollutants in disadvantaged neighbourhoods can cause inflammation and respiratory compromise, with cumulative effects intensified by poor nutrition, housing strain, and limited healthcare access [

4,

10].

Second, reciprocity refers to the dynamic feedback loop between biophysical environments and social systems. Marginalized communities are not just more negatively impacted by environmental harm but their inability to act further due to lack of agency or political power contributes to ecological harm. For example, insufficient infrastructure may diminish civic engagement and hence under-resourced services and accumulated exposure risks [

8,

11].

Finally, the concepts of vulnerability and resilience provide a framework for understanding disparities in health outcomes. Whereas vulnerability arises from social disadvantage and environmental risk as crossing factors, resilience represents how people or places are capable of adapting after being exposed to damage. Such outcomes are not the product of individual behavior alone, and it is the structural conditions, including housing policies, urban zoning and environmental regulation, that have made them possible [

2,

16].

Through utilizing these integrative principles, interdisciplinary knowledge can more effectively identify and remediate the foundation of health disparities. This approach supports a shift from reactive care models toward proactive systems that prioritize health equity and environmental justice. This paper extends these frameworks by explicitly bridging environmental science teaching units (e.g., pollution, climate, land use) with public health equity models, framing the “classroom-to-policy” crosswalk itself as an original contribution. Moreover, it highlights how emerging technology tools such as NurseAI and community-based decision support systems could operationalize these integrative frameworks for both education and practice.

To develop this framework, I adapted topics from the AP Environmental Science curriculum including pollution, ecosystems, resource use, and climate and mapped them to recognized domains of the Social Determinants of Health. This approach demonstrates how educational content can be reframed to inform public health practice. By aligning classroom pedagogy with applied equity challenges, this paper builds a novel bridge between classroom science and systemic health outcomes. In doing so, it advances an interdisciplinary framework that is both theoretically grounded and practice-oriented.

3. Key Intersections of the Environment with SDOH

3.1. Housing & Neighbourhood Quality

Housing conditions and neighbourhood environments are core social determinants of health (SDOH) that significantly influence both physical and mental health [

17]. Socially disadvantaged groups often reside in housing that is substandard, characterized by structural deterioration, crowding, and poor heating/cooling, as well as, exposure to environmental hazards. These housing stressors intersect with more general socioeconomic vulnerabilities to perpetuate the health inequities experienced by disadvantaged populations [

18,

19].

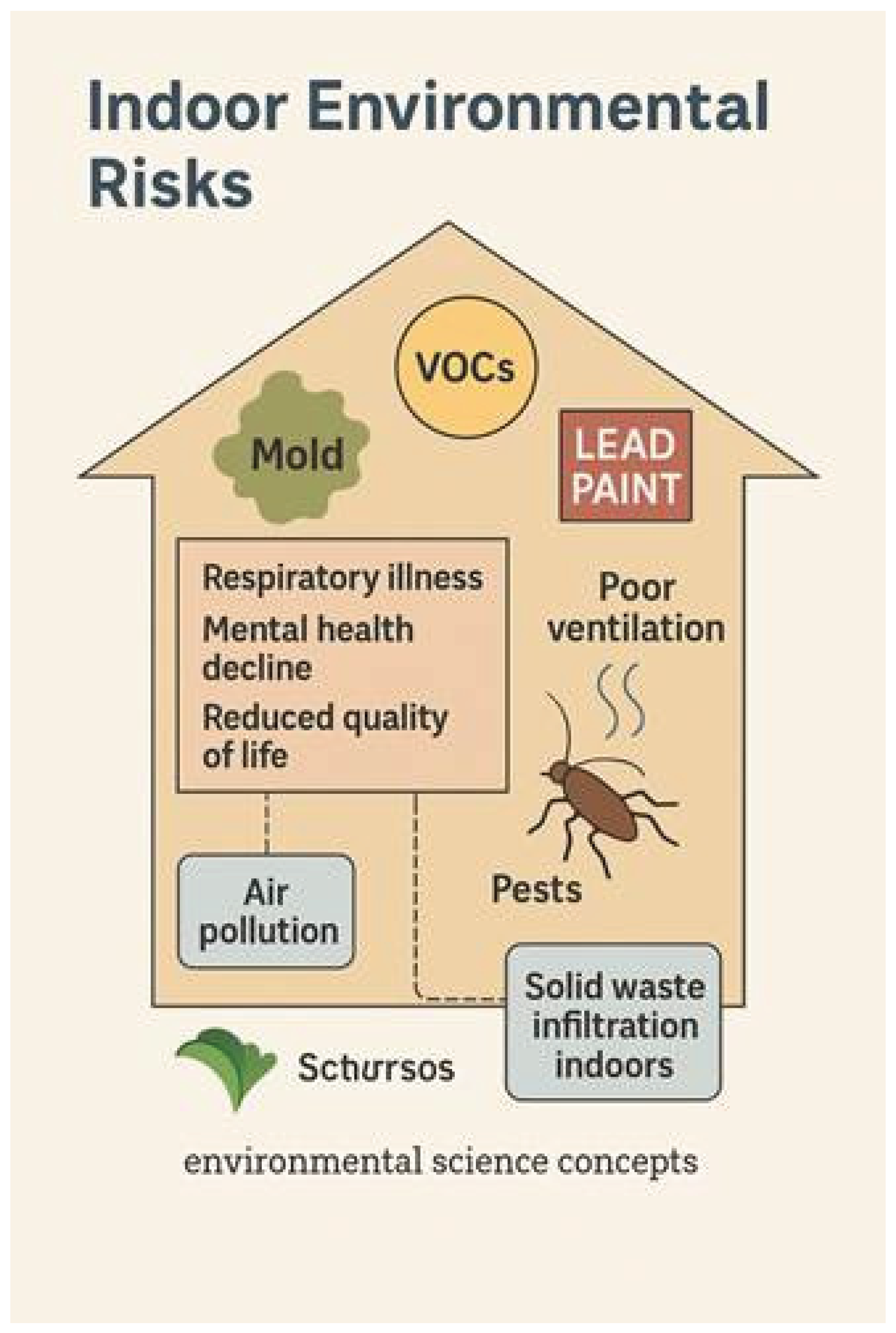

Environmental hazards in substandard living conditions include exposure to mold, lead-based paint, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), pest infestations, and inadequate ventilation. VOCs, in particular, are emitted from plastics, paints, and household materials accumulating in poorly ventilated indoor environments and contributing to respiratory diseases, eye irritation, and neurological effects [

12]. Poor water infrastructure adds to indoor contamination, as non-regulated or failing systems increase exposure to waterborne pathogens and chemicals [

20].

Prevalence data underscore the scale of the problem. In Dallas, Texas, 31.4% of surveyed households reported a lifetime asthma diagnosis, and 26.7% reported current asthma substantially higher than the U.S. average [

21]. More than 60% of residents in the Singleton Corridor, a predominantly minority neighbourhood, rated their air quality as “low” or “very low,” and 83.7% reported illness attributable to air pollution. These findings highlight how environmental stressors concentrate in under-resourced communities.

In addition to environmental hazards, significant social risks also exist. High population density, insecure housing tenure, and landlord neglect are characteristics of rented housing in low-income areas. In many U.S. cities, more than 40% of low-income renters live in units classified as “inadequate housing,” with limited regulatory oversight, leaving tenants little recourse for demanding repairs or safe living conditions. Most of these apartments are not regulated, giving tenants very little recourse to request repairs or for better living conditions [

22]. For older populations and other vulnerable groups, poor housing quality reduces residential satisfaction and also impacts psychological well-being [

23].

The health impact of these housing conditions is well documented. Physical consequences of poor insulation and ventilation include increased risks of asthma, chronic respiratory diseases and heat-related diseases [

24,

25]. In St. Louis, Missouri, asthma “hotspots” were disproportionately located in neighbourhoods with higher poverty, greater proportions of non-White residents, deteriorating housing, and limited healthcare access, illustrating how built environments interact with social disadvantage to exacerbate health inequities [

26]. Psychological effects and stress levels associated with thermal discomfort, safety perception or cost can increase anxiety, depression, and psychological distress, and they also significantly affect mental health [

2,

27]. Better home quality, specifically in terms of energy efficiency and water access, has been associated with enhanced health and well-being [

28].

From an environmental science perspective, poor housing quality functions as a multiplier of exposure to indoor environmental pollutants. Units on Air and Water Pollution, Human Health, and Solid Waste illustrate how contaminants migrate inside, and how residents of underprivileged housing suffer greater exposures. Experience in low-income countries suggests that the accumulation of solid waste around or in living spaces does not only attract pests, but also results in soil and water contamination through leaching over time, and therefore creates chronic pathways of exposure [

5]. This integrative lens highlights how concepts from environmental science (pollutant transport, toxicology, waste dynamics) explain the mechanisms of SDOH inequities, reinforcing the need for policies that link housing quality improvements with environmental health interventions.

Figure 1.

Indoor Environmental Risks. This infographic illustrates the major hazards associated with substandard housing conditions, including mold, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), lead paint, pests, and poor ventilation. Each of these environmental stressors contributes to adverse health outcomes such as respiratory illness, mental health decline, and reduced quality of life. The figure also connects these risks to environmental science concepts, including air pollution and solid waste infiltration indoors, highlighting the intersection of social and ecological determinants of health.

Figure 1.

Indoor Environmental Risks. This infographic illustrates the major hazards associated with substandard housing conditions, including mold, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), lead paint, pests, and poor ventilation. Each of these environmental stressors contributes to adverse health outcomes such as respiratory illness, mental health decline, and reduced quality of life. The figure also connects these risks to environmental science concepts, including air pollution and solid waste infiltration indoors, highlighting the intersection of social and ecological determinants of health.

3.2. Air Quality Disparities

Air quality is a fundamental environmental determinant of human morbidity and mortality and a central driver of inequities within the broader SDOH framework. Low-income and marginalized communities are disproportionately located near highways, industrial zones, and factories, resulting in higher exposures to fine particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), nitrogen dioxide (NO

2), sulphur dioxide (SO

2), and ozone [

29,

30]. These pollutants are associated with a wide range of chronic health conditions such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cardiovascular disease, and adverse pregnancy outcomes including preterm birth, and low birth weight [

1,

31].

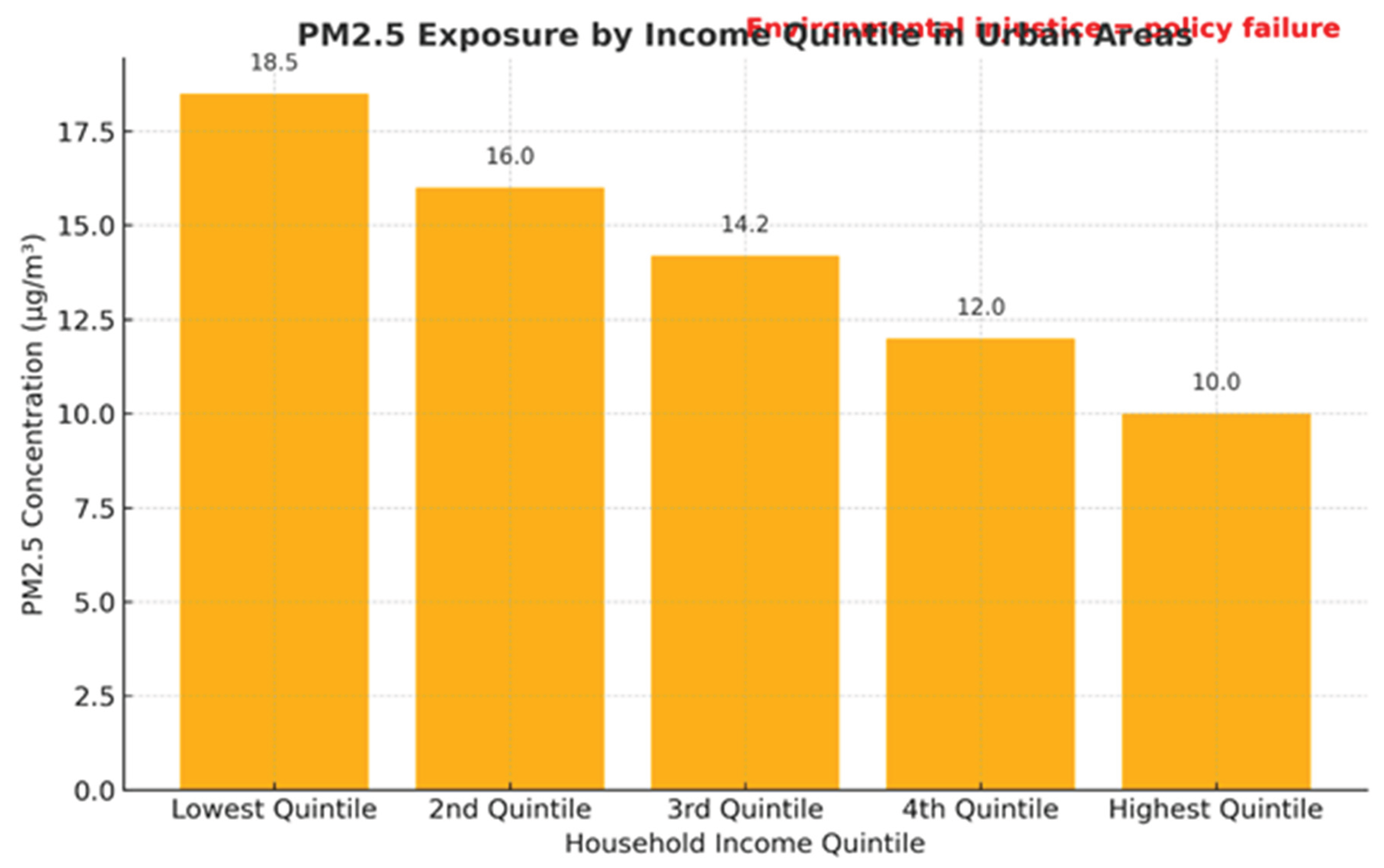

Globally, air pollution is responsible for approximately 8 million premature deaths each year, with outdoor PM2.5 alone accounting for over 4.2 million deaths [

32]. In the United States, Black Americans experience the highest proportion of deaths attributable to PM2.5, with over half of the Black–White mortality gap linked to air pollution exposure [

33].

This environmental burden reflects a persistent pattern of environmental injustice, where polluting infrastructure is most often established in or around low-income communities. Regulatory systems rarely account for cumulative exposures or synergistic effects, leaving low-income neighbourhoods disproportionately burdened. Inadequate air quality monitoring has led to poor health and a lack of community capacity to work for clean divides, in South Chicago and urban Bangladesh [

34,

35].

Case studies highlight the disproportionate impacts. In New York City, neighbourhoods with higher percentages of Black residents reported significantly higher rates of paediatric asthma emergency department (ED) visits, strongly correlated with elevated PM2.5 and urban heat island effects [

36]. Similarly, in Houston, Black children had 2.6 times higher odds of asthma diagnosis compared to White children, even after controlling for environmental exposures [

37].

Despite these challenges, affected communities tend to adapt, wearing masks, staying inside, and checking the air quality indices. Yet these coping strategies are insufficient to offset structurally entrenched exposure inequalities [

38]. Addressing social vulnerability and environmental exposure measures for air quality regulation is critical to achieving health equity [

39,

40].

From an environmental science perspective, air quality disparities illustrate core principles of atmospheric chemistry, pollutant transport, and exposure science. The unequal distribution of PM2.5 and NO2 across urban space exemplifies how physical processes such as thermal inversions and traffic density intersect with zoning policies to shape health inequities.

Figure 2.

PM2.5 Exposure by Income Quintile in Urban Areas. This bar chart illustrates disparities in PM2.5 exposure levels across household income quintiles, with the lowest-income groups experiencing nearly double the exposure of the highest-income quintiles. The data, reflecting WHO/EPA trends, highlight disproportionate burdens of air pollution on low-income communities. The callout “Environmental injustice = policy failure” emphasizes that unequal exposure to polluted air is not a natural occurrence but the result of systemic regulatory and policy shortcomings.

Figure 2.

PM2.5 Exposure by Income Quintile in Urban Areas. This bar chart illustrates disparities in PM2.5 exposure levels across household income quintiles, with the lowest-income groups experiencing nearly double the exposure of the highest-income quintiles. The data, reflecting WHO/EPA trends, highlight disproportionate burdens of air pollution on low-income communities. The callout “Environmental injustice = policy failure” emphasizes that unequal exposure to polluted air is not a natural occurrence but the result of systemic regulatory and policy shortcomings.

3.3. Quality of Water & Sanitation

Access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation are essential for public health. Globally, 2.2 billion people lack safely managed drinking water and 3.6 billion lack safely managed sanitation services, with the greatest deficits concentrated in low- and middle-income countries [

41]. In the U.S., disadvantaged populations are disproportionately reliant on high-risk water sources, including unregulated wells, intermittent supply systems, or failing plumbing infrastructures [

42,

43]. Toxic materials, including lead and other contaminants, have severe physiological impact when consumed. Specific toxicities have been directly linked to nitrates and microbial pathogens like

E. coli and

Vibrio cholerae, causing widespread outbreaks in rural and informal settlements where water treatment infrastructure is weak [

44,

45], especially in the rural and informal settlements.

The health burden of unsafe water is immense. Inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) are estimated to cause 829,000 deaths annually from diarrheal diseases, accounting for nearly 60% of global diarrhoea-related mortality [

46]. These diseases remain leading causes of mortality among children under five, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia [

47].

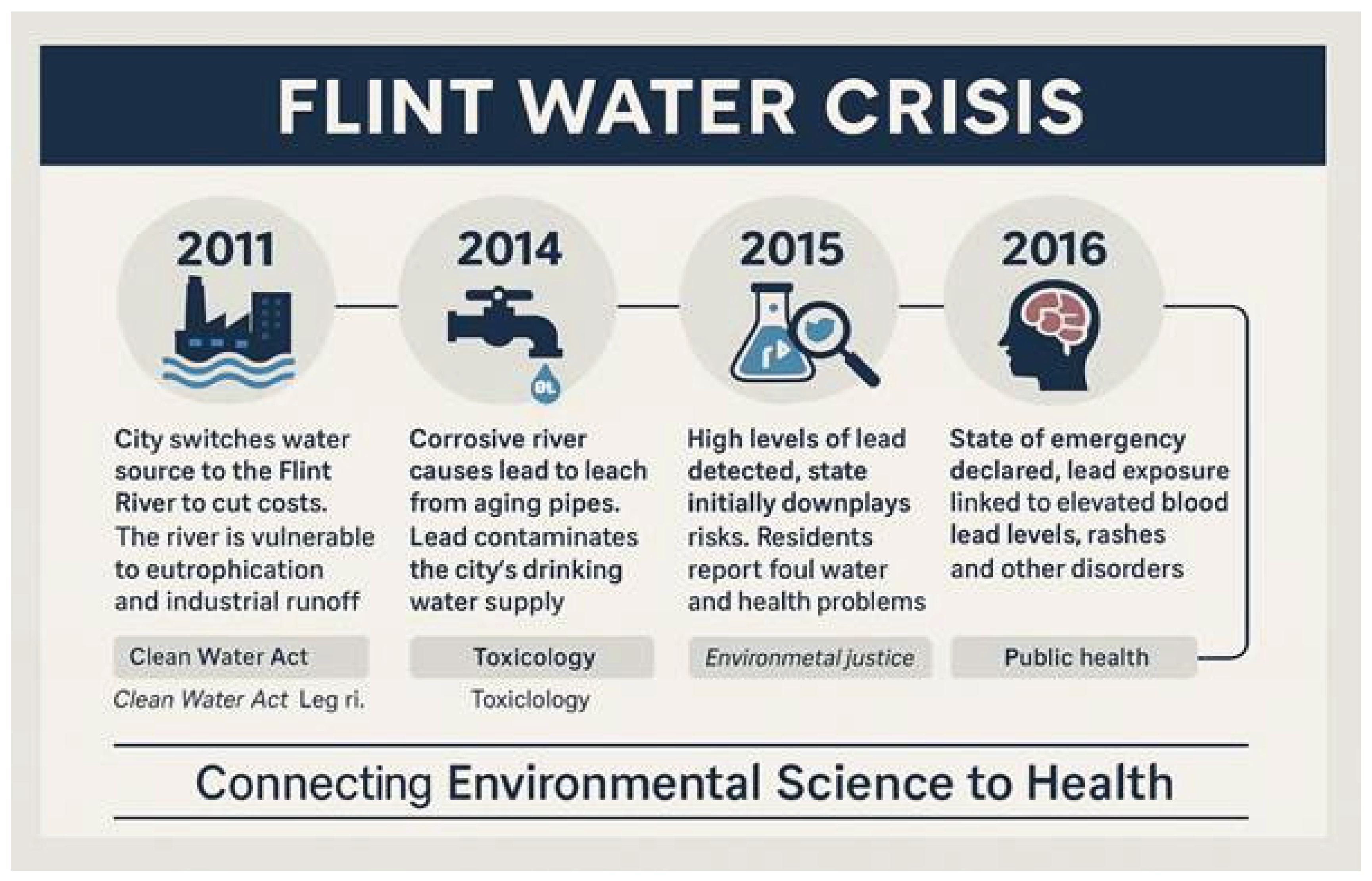

Even in affluent countries such as the U.S., the Flint, Michigan water crisis exposed over 99,000 residents including more than 9,000 children under age six to elevated lead levels, leading to long-term neurodevelopmental and health consequences [

48]. This case illustrates how political disinvestment and regulatory neglect can transform technical failures into systemic injustices.

From an environmental science perspective, chapters on aquatic systems, eutrophication, and microbiology demonstrate how nutrient pollution, industrial runoff, and failing sewage systems degrade water quality, fostering pathogen survival and algal blooms that threaten both ecological and human health. Although policies such as the Clean Water Act are intended to safeguard public health, gaps in enforcement and chronic infrastructure disinvestment leave many low-income and minority communities at heightened risk [

20].

Figure 3.

Timeline of the Flint Water Crisis illustrating policy neglect, lead contamination, and resulting health consequences, with connections to environmental science topics such as the Clean Water Act, eutrophication, and industrial runoff.

Figure 3.

Timeline of the Flint Water Crisis illustrating policy neglect, lead contamination, and resulting health consequences, with connections to environmental science topics such as the Clean Water Act, eutrophication, and industrial runoff.

Sanitation inequities remain stark between rural and urban areas, with Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia showing the greatest disparities in access to both safe water and improved sanitation facilities (

Table 1).

3.4. Waste and Industrial Zone Spatial Proximity

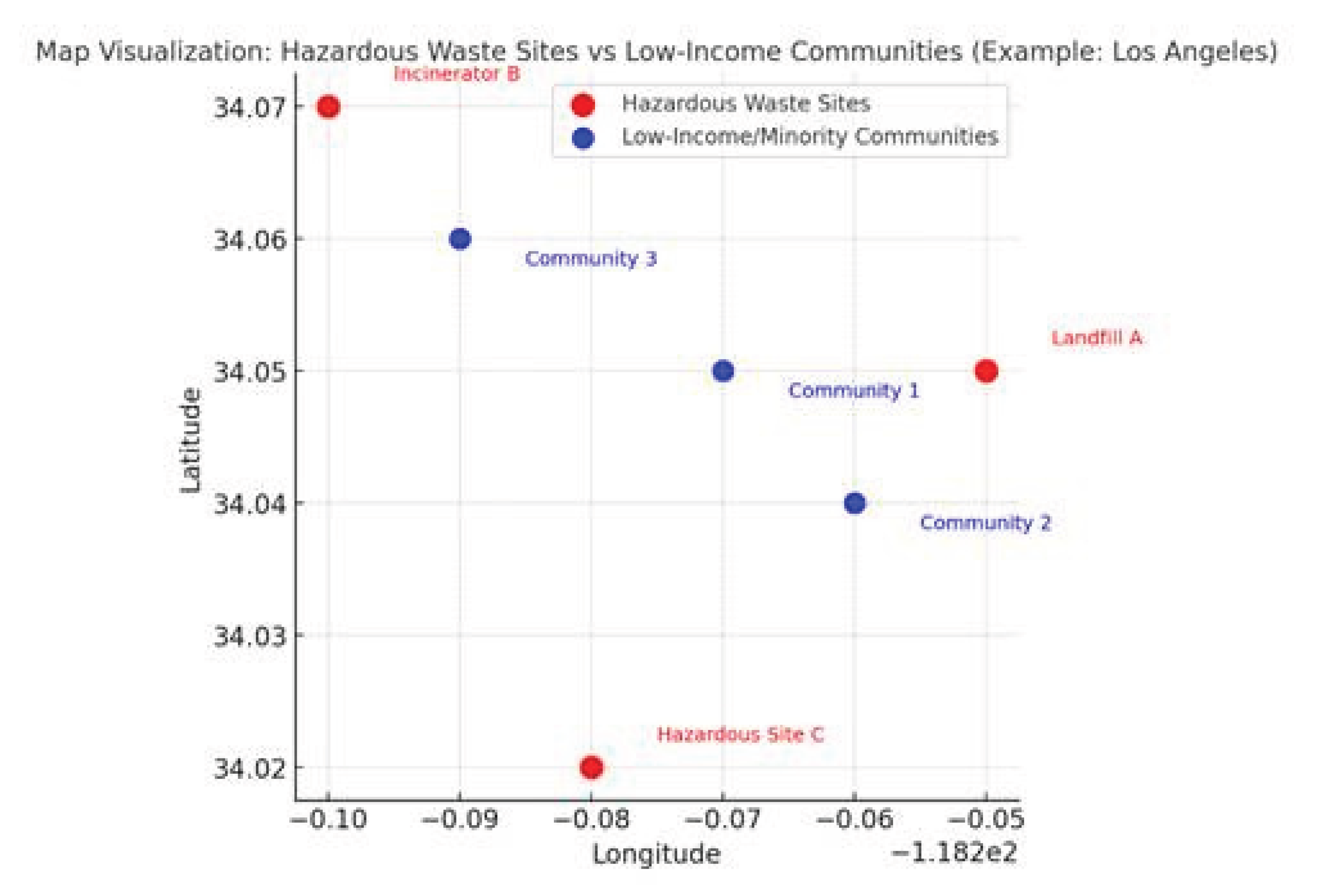

Living near hazardous waste sites, incinerators, and industrial facilities poses significant environmental health risks, particularly for low-income and racially marginalized populations. In the United States, more than 9 million people live within 1 mile of a hazardous waste site, with disproportionate clustering in predominantly Black, Latino, and low-income communities [

49,

50]. These residents are frequently exposed to dioxins, heavy metals, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and other toxins that contaminate air, soil, and groundwater. Documented outcomes include elevated rates of cancer, adverse reproductive events, chronic respiratory illness, and dermatological conditions [

51,

52,

53].

From a policy perspective, these exposures often stem from inequitable zoning practices, “buffer zones” that prioritize industry over residents, and discriminatory siting policies. This reflects structural environmental racism: in Texas, for example, hazardous waste facilities were found to be sited 2–3 times more often in neighbourhoods with majority-minority populations [

54,

55].

Case studies further illustrate this injustice. The Love Canal disaster in New York exposed more than 800 families to toxic waste buried beneath their homes, resulting in widespread reports of birth defects, miscarriages, and chronic illness [

56]. More recently, studies in Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley” have documented cancer risks up to 50 times higher than the national average due to proximity to petrochemical plants [

57].

These patterns reflect what environmental science identifies as a recurring cycle of injustice—where landfills, waste-to-energy incinerators, and industrial facilities are more likely to be located in low-income or marginalized communities. The discipline also teaches how hazardous substances persist in ecosystems through biomagnification and bioaccumulation, contaminating food chains and imposing intergenerational health risks. Lessons from solid waste management, toxicology, and ecological resilience underscore the long-term hazards of mismanaging industrial waste. Policies that prioritize environmental justice through equitable zoning, regulation, and remediation are essential to protecting public health and advancing equity. In many U.S. cities, hazardous waste facilities and incinerators are disproportionately located near low-income or minority neighbourhoods, illustrating patterns of ecological racism (

Figure 4).

Studies consistently show that hazardous waste and industrial facilities are rarely located near higher-income or predominantly white neighborhoods. By comparison, low-income and minority communities—like those visualized in

Figure 4—experience significantly greater exposure to toxic emissions and environmental risk. This spatial imbalance highlights how urban planning decisions perpetuate patterns of ecological racism and structural inequity.

3.5. Climate and Heat Exposure

Disparities in climate-related health among urban populations are stark, with low-income neighbourhoods, such as those in Philadelphia, Phoenix, and Detroit experiencing high levels of the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect because of low levels of vegetation density, limited tree cover, and poorly insulated housing. Such conditions increase ambient temperatures, particularly during heat waves, and enhance the chances for heat strokes, cardiovascular events, and heat-induced mortality, especially among the elderly and chronically ill [

29,

39].

Quantitative evidence underscores this inequity: during the 1995 Chicago heat wave, more than 700 deaths were recorded in just five days, with mortality rates highest among low-income Black and Latino neighbourhoods that lacked air conditioning and adequate social support systems [

58]. Globally, the WHO estimates that between 2000 and 2019, heat-related mortality among people over 65 increased by 53%, disproportionately affecting urban residents in low-resource settings [

59].

Research in Los Angeles and other parts of the south-western United States shows that disadvantaged neighbourhoods can be 2.2–3.7 °C hotter than affluent ones, with UHI intensity correlating strongly with redlined districts and housing segregation [

40,

60]. City populations are particularly at risk, since many households lack adequate cooling infrastructure, energy-efficient housing, or political leverage to demand climate-responsive urban planning [

61].

From an environmental science perspective, units on Global Climate Change, Urban Sustainability, and Environmental Justice explain how anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions and urban design choices amplify UHI intensity. Mitigation strategies such as reflective surfaces, tree planting, and equitable access to cooling infrastructure are essential adaptations. Applying a climate justice lens is critical to understanding how climate science and urban infrastructure must evolve to protect vulnerable residents.

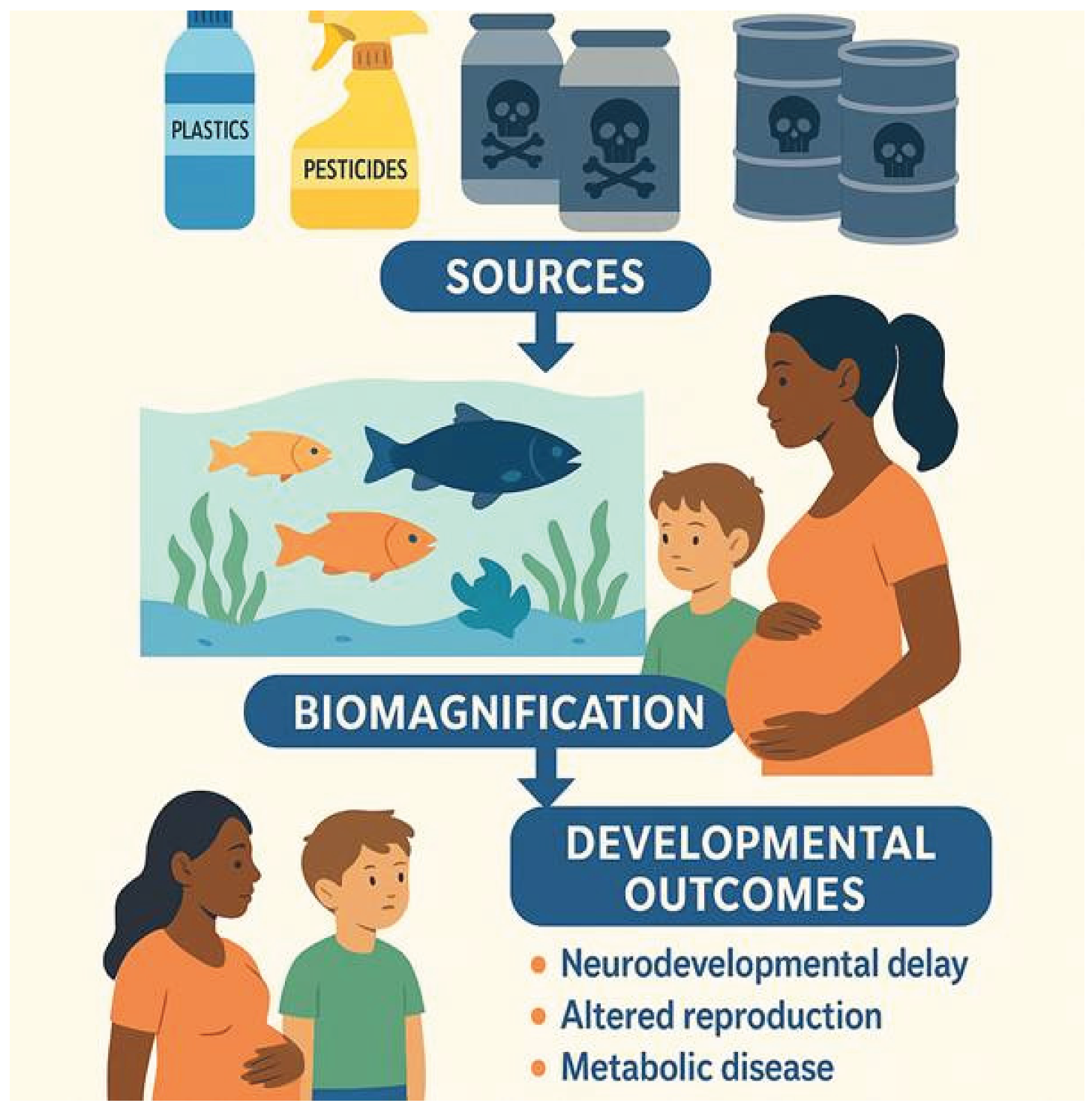

3.6. Toxicology and Endocrine Disruption

Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) such as phthalates, biphenyl A (BPA), pesticides, and heavy metals including mercury and lead represents a growing global public health crisis, with disproportionate risks borne by pregnant people, children, and low-income communities. Bio monitoring studies show that over 90% of the U.S. population has detectable levels of BPA or phthalates in their bodies, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have been detected in the blood of an estimated 97% of Americans [

62]. These chemicals disrupt endocrine regulation and are associated with neurodevelopmental delay, altered reproductive function, and chronic metabolic disease [

63,

64].

EDCs enter human systems through multiple pathways, including contaminated food and water, domestic products, cosmetics, and agricultural residues. In regions with weak or absent regulatory oversight, exposures are significantly higher, especially in Global South communities reliant on pesticide-intensive farming [

65,

66]. These substances are persistent in ecosystems, where they biomagnify through food webs: a process emphasized in environmental science curricula that address the topics of toxicology and chemical pollution [

65,

67].

Documented adverse health effects include reduced IQ, increased risk of autism spectrum disorders, childhood obesity, and altered timing of puberty [

68,

69]. Case studies illustrate the devastating consequences: the Minamata Bay mercury poisoning disaster in Japan led to thousands of cases of neurological impairment, congenital disabilities, and death; more recently, PFAS contamination of U.S. municipal water supplies has been linked to thyroid disorders, cancers, and immune dysfunction [

70]. Environmental disparities in exposure, stemming from geographic location, housing conditions, and regulatory loopholes, highlight the urgency for environmental health policy solutions that curtail chemical risks in marginalized communities [

66,

71]. The following diagram demonstrates how toxic exposures, such as plastics, pesticides, and heavy metals, enter ecosystems, undergo bio magnification, and result in developmental and metabolic health consequences (

Figure 5).

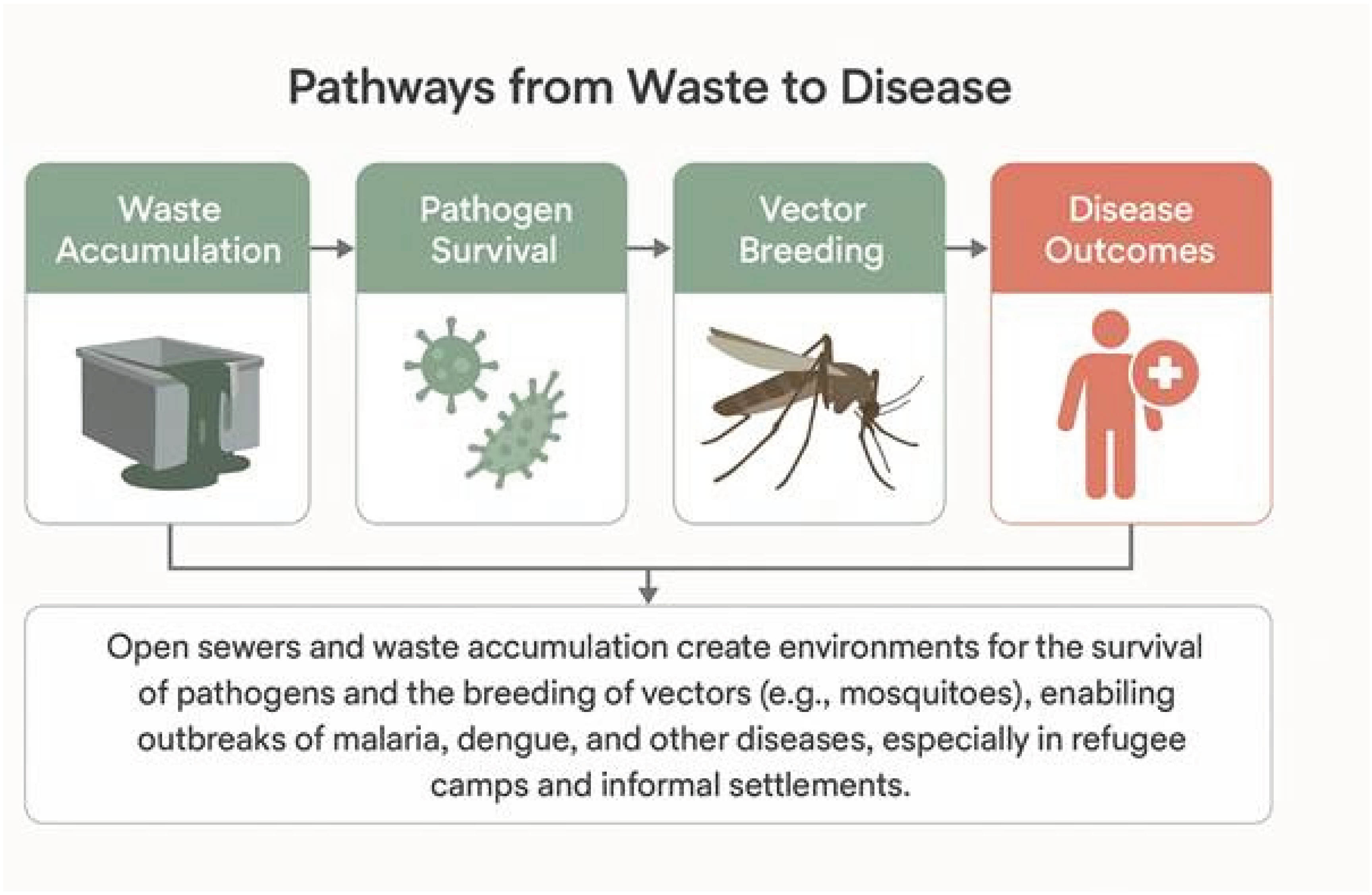

3.7. Infectious Diseases and Sanitation

Crowded living conditions and inadequate sanitation contribute to the spread of infectious diseases such as hepatitis and leishmaniasis, particularly in refugee camps and informal settlements.. Inadequate sanitation facilities—such as open drains, lack of regular waste disposal, and overcrowding become incubation grounds for contagious diseases, especially in refugee camps or urban slums. Globally, unsafe water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) are responsible for an estimated 1.4 million deaths annually and 74 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), with the greatest burden in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia [

46]. These conditions provide the enabling environment for the transmission of vector-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue fever, and bacterial infections like typhoid, leptospirosis, and tuberculosis [

72,

73].

Environment contamination from uncollected waste provides a foundation for the survival of pathogens in water, soil, and surfaces, in countries where no protective services or public sensitization exist [

74,

75]. Research in West Africa demonstrates a direct relationship between waste exposure to the occurrence of disease, especially among children and waste handlers [

76,

77].

Case examples highlight the devastating consequences of sanitation failures: the 2010 cholera outbreak in Haiti, linked to contaminated rivers, caused over 800,000 cases and 10,000 deaths, disproportionately affecting rural and peri-urban communities [

78]. Similarly, informal urban settlements in Lagos, Nigeria report diarrhea prevalence rates exceeding 25% in children under five, directly linked to lack of sewage and water infrastructure [

73]. This injustice is compounded by the fact that cholera is easily treatable with timely access to oral rehydration therapy and medical care—resources that were largely unavailable to those most affected.

The Pathogens and Water Quality environmental science chapters qualitatively explain how environmental factors (e.g., stagnant water and lack of sewage disposal) facilitate vector breeding and microbial sustainability. Challenging these problems requires investment in infrastructure and community participation to break the cycle of poverty and infection. The diagram below illustrates how inadequate sanitation and waste accumulation facilitate pathogen survival and vector breeding, creating conditions for widespread infectious disease outbreaks (

Figure 6).

3.8. Transportation Access

Safe and reliable transportation is also a key determinant of health, because it directly conditions access to healthcare, schools, employment, and nutritious food sources. In the U.S., nearly 3.6 million people miss or delay medical care each year due to lack of transportation, with disproportionate impacts on rural and low-income households [

79]. In low-income or rural regions, transportation barriers result in missed medical visits, low medication adherence, and uncontrolled chronic disease [

80,

81].

Children and families with lower mobility have lesser access to schools, safe playgrounds, and fresh food supply, and are more likely to suffer from mental health, developmental delay, and malnutrition [

82]. Studies of the built environment highlight how fragmented urban transit systems, automobile-dependent infrastructure, and emission-intensive traffic corridors threaten communities through pollution and spatial segregation [

83]. Food deserts, areas where residents must travel more than a mile in urban settings or 10 miles in rural settings to access fresh food, affect over 23.5 million Americans, with transportation barriers compounding inequities [

82].

Studies of the built environment highlight how fragmented urban transit systems, automobile-dependent infrastructure, and emission-intensive traffic corridors threaten communities through pollution and spatial segregation [

83]. For example, reliance on car-centric planning in U.S. cities contributes not only to traffic-related emissions (responsible for ~29% of greenhouse gas emissions nationally) but also to disproportionate asthma burdens in low-income and minority neighbourhoods located near highways [

84].

Although less emphasized in environmental science literature, chapters on urban land use and sustainable planning reinforce that transportation systems shape exposure to pollution and influence social inclusion or exclusion. From an environmental health equity lens, reliable transit is not only mobility infrastructure but also a mechanism to reduce emissions, bridge socioeconomic divides, and promote equitable access to healthcare and education. Equal access to clean, affordable, and efficient transit ought to be a central plank of health and environment policy reform.

3.9. Education and Environmental Health Literacy

Health literacy, or the ability to obtain, process, and understand health information, is a foundational determinant for reducing environmental health risks and promoting preventive behaviours. Low health literacy affects an estimated 36% of the U.S. adult population, disproportionately burdening migrant, minority, and low-income groups [

85]. Lower literate people do not know what unsafe exposure practices are, who the sources of pollution are, and what to do about it. This is particularly evident for migrants and low-income communities, who frequently experience a double burden of linguistic and systemic obstacles limiting access to health information [

86,

87].

Research demonstrates that increased environmental health literacy (EHL) promotes individual and community capabilities to manage risks, practice preventive measures, and participate in community-based environmental action [

88,

89]. For example, community-based water quality monitoring programs in rural Italy and South Asia have significantly increased residents’ ability to identify contamination and advocate for safer supplies [

90,

91]. Targeted programs for groups that are at risk, such as context-specific learning, community-based science and outreach, and bilingual outreach, have proven effective in increasing risk understanding and control [

90,

91].

The field of environmental science education already has a significant focus on environmental ethics, policy literacy, and citizen engagement. Incorporating these elements into public health frameworks can empower communities to not only protect themselves but also to push back on decision-makers for environmental injustices. Emerging tools like NurseAI and digital decision-support platforms further expand EHL by providing real-time, localized data on pollution, climate risks, and exposure pathways, equipping communities with both knowledge and agency. The following graphic illustrates how low levels of health literacy increase risk exposure, while improved health literacy fosters preventive behaviours, community advocacy, and better health outcomes (

Figure 7).

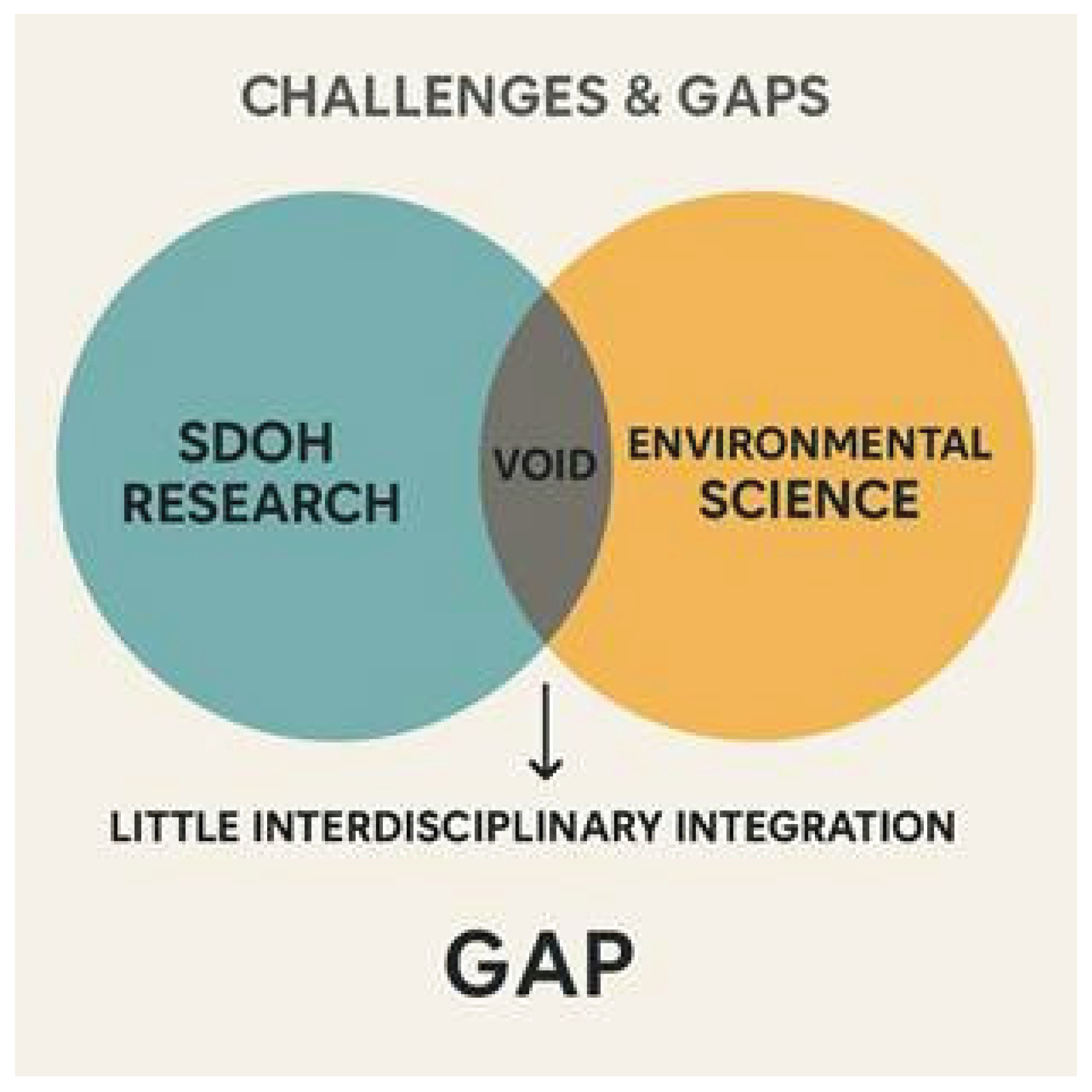

4. Challenges and Theoretical Void

Although the relationships between environmental science and SDOH have received growing attention, significant conceptual and operational challenges remain. One key obstacle is the gap between the prevailing bio-medical frameworks and ecological theory. Conventional allopathic medical models focus on individual-level disease diagnosis and treatment and fail to attend to primary environmental predisposing factors, such as air pollution, toxic exposure, or vulnerability to heat [

8,

10]. Ecological models, in contrast, emphasize global environmental changes, but rarely incorporate the socio-political systems through which environmental harms are unequally distributed [

4].

A critical barrier is data scarcity. Fewer than 20% of the world’s population is covered by robust environmental health surveillance systems, and most low- and middle-income countries lack long-term monitoring [

92]. This gap leads to major underestimations of disease burden. For instance, in India, incomplete satellite PM2.5 data contributed to nearly 94,000 excess deaths being misattributed annually [

93]. In China, improved data integration revealed 30.8 million premature deaths from PM2.5 exposure between 2000–2016 losses previously invisible to global models [

94].

A further issue is the absence of robust cross-sector data to account for the joint effects of multiple exposures in areas such as housing, pollution, climate, and socioeconomic status. This impedes attempts to evaluate long-term synergistic health risks, particularly in underprivileged communities where multiple vulnerabilities frequently coexist [

2,

9]. Current data systems rarely link environmental indicators to other health surveillance systems, resulting in incomplete assessments of risk and the distribution of resources [

95].

Further, the concept of SDOH is at risk of dilution, miscommunication, or loss, especially when reduced to lists of variables with little consideration to structural roots or historical trajectory. As Lucyk et al. (2017) assert, failing to anchor SDOH in a framework of health equity and justice can obscure accountability and impact effective policy measures [

16].

Finally, there is a small literature on intersectionality in environmental exposure as it relates to race, class, gender, and geography and how these intersect to create vulnerability and resilience. Evidence from urban heat island studies, for instance, shows that Black and Latino residents face both greater exposure and higher asthma exacerbation rates than White residents, illustrating cumulative disadvantage [

23,

60]. These theoretical gaps can be addressed with interdisciplinary models that bridge science, policy, and justice. To illustrate the conceptual and methodological divide, the diagram below highlights the limited overlap between SDOH research and environmental science, emphasizing the theoretical “void” where interdisciplinary integration is urgently needed. Despite increasing recognition of the links between environment and health, research on social determinants of health (SDOH) and environmental science often develops in isolation, leaving a critical gap in interdisciplinary integration (

Figure 8).

5. Policy and Intervention Strategies

The promotion of health equity requires interdisciplinary and broad scale actions that take into account the social

and environmental determinants of health. The foundational step is to promote integrated frameworks in public health planning and this will provide means to comprehend how cumulative exposures influence health across time and space [

5,

9].

Environmental regulations also need to be strengthened in low-income and marginalized areas, where enforcement is often weak and exposure risks are highest. These include more stringent regulations related to industrial emissions in proximity to residential areas, better waste treatment facilities, and pollution treatment techniques suited to high-risk environments [

31,

34].

Quantified evidence underscores the impact of strong policy. The U.S. Clean Air Act Amendments (1990) are estimated to prevent 230,000 premature deaths annually and return benefits worth 30 times the cost of compliance [

96]. Lead abatement programs save

$17–

$221 for every

$1 invested, mainly via improved lifetime earnings and reduced special education needs [

97]. In New York City, climate action plans (80x50) are projected to reduce PM2.5 by 7% and prevent 160–390 premature deaths annually, generating

$3.4 billion in yearly economic benefits [

98]. Public cooling centres reduce heat-related mortality by up to 30% in heat wave-prone urban neighbourhoods [

61].

Investments in data infrastructure, such as real-time monitoring systems of environmental hazards, health disparities, and social vulnerability indicators are equally critical. Such resources are critical for focused interventions and fair resource distribution [

20,

48].

To build resilience, governments and institutions should scale up environmental literacy programs and promote community-led efforts. For sustaining positive changes in environmental and public health outcomes, resident’s knowledge and agency are highly important [

88,

99]. For instance, implementation of school-based programs in the form of environmental health education, neighbourhood advocacy coalitions, and citizen science programs can generate awareness and policy motivation [

90,

91].

Specific Intervention strategies may include the following:

· Zoning reforms to protect at-risk neighbourhoods from siting of toxic facilities

· Screening tools for environmental justice reflecting SDOH and exposures

· Transformational public cooling systems in heat-burdened, underserved urban communities

· Discounted transit fare for low-income residents

· Routine SDOH screening in all healthcare settings, combined with eco-epidemiological metrics [

80,

81]

We need a pivot to holistic, equity-informed policy design to respond to the mutually reinforcing environmental degradation and public health disparities.

One practical implication of this synthesis is the potential integration of environmental SDOH into digital health tools. For example, the NurseAI platform that I co-developed includes screening for social needs such as housing or food insecurity. Expanding this to incorporate environmental risks like air quality alerts or heat vulnerability screening could help frontline providers translate environmental science insights directly into patient care. This illustrates how research can be operationalized through technology to advance health equity.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have shown that environmental conditions are not extraneous to health; they are key social determinants that heavily influence health pathways, particularly among stigmatized populations. From clean air and water to toxic exposure and housing infrastructure, the field of environmental science provides a crucial lens for understanding the ways in which structural and environmental forces intersect to create health disparities.

An urgent and overdue necessity is to fully integrate environmental science with public health equity frameworks. According to the World Health Organization, nearly 24% of global deaths are attributable to modifiable environmental factors, including air, water, and chemical exposures [

46]. The Global Burden of Disease study further estimates that environmental and occupational risks account for 18.9% of global deaths and 14.4% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [

6]. Separating environmental exposures from social circumstances obscures the nuances of vulnerability and resilience. Inter-disciplinary models, such as the Social Exposure and Salutogenic Environmental Health Model, point the way forward by thinking about health as the result of the dynamic interplay between biological, sociological, and ecological systems.

But combining these fields takes more than just theoretical alignment: It requires systems-level reform and structural transformation. This includes multidisciplinary work among public health practitioners, environmental scientists, urban planners, educators, and policy-makers. It is only by making structural change strengthened environmental regulation, community-driven education and mobilization, just urban design, and focused public investment that we can start to overcome the root causes of environmental health disparities.

The message is straightforward: justice and science must underpin equitable environmental policy and practice. The distinctive contribution of this work is its explicit bridging of AP Environmental Science frameworks with public health equity models, framed not only as an academic synthesis but as a pedagogical and policy innovation. Emerging technology tools such as NurseAI and community-based decision support systems offer a future-facing capacity to integrate environmental and health data in real time, empowering both practitioners and communities to identify risks, monitor exposures, and mobilize interventions.

By linking environmental science knowledge with the lived realities documented in SDOH frameworks, and by leveraging digital tools for community empowerment, we can move toward a future in which all communities not only survive but thrive in healthy, sustainable, and equitable environments.

References

- Jilani MH, Javed Z, Yahya T, Valero-Elizondo J, Khan SU, Kash B, et al. Social Determinants of Health and Cardiovascular Disease: Current State and Future Directions Towards Healthcare Equity. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2021 Jul 26;23(9):55.

- Noor T, Ahmad T, Afrin S. Role of Social Determinants in Reshaping the Public Health Policies: A Comprehensive Study. Int J Sci Healthcare Res [Internet]. 2024 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Sep 21];9(2):263–70. Available from: https://ijshr.com/IJSHR_Vol.9_Issue.2_April2024/IJSHR36.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Social determinants of health [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health.

- Graham H, White PCL. Social determinants and lifestyles: integrating environmental and public health perspectives. Public Health [Internet]. 2016 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Sep 21];141:270–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0033350616302505.

- Pleyer JA, Pesliak LD, McCall T. Salutogenic Environmental Health Model-proposing an integrative and interdisciplinary lens on the genesis of health. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1445181.

- Clark SN, Anenberg SC, Brauer M. Global Burden of Disease from Environmental Factors. Annu Rev Public Health. 2025 Apr;46(1):233–51.

- Fuller R, Landrigan PJ, Balakrishnan K, Bathan G, Bose-O’Reilly S, Brauer M, et al. Pollution and health: a progress update. Lancet Planet Health. 2022 Jun;6(6):e535–47.

- Golden TL, Wendel ML. Public Health’s Next Step in Advancing Equity: Re-evaluating Epistemological Assumptions to Move Social Determinants From Theory to Practice. Front Public Health. 2020;8:131.

- Gudi-Mindermann H, White M, Roczen J, Riedel N, Dreger S, Bolte G. Integrating the social environment with an equity perspective into the exposome paradigm: A new conceptual framework of the Social Exposome. Environ Res. 2023 Sep 15;233:116485.

- Yates-Doerr E. Reworking the Social Determinants of Health: Responding to Material-Semiotic Indeterminacy in Public Health Interventions. Med Anthropol Q. 2020 Sep;34(3):378–97.

- Dean HD, Williams KM, Fenton KA. From Theory to Action: Applying Social Determinants of Health to Public Health Practice. Public Health Rep [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 Sep 21];128(Suppl 3):1–4. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3945442/.

- Riva A, Rebecchi A, Capolongo S, Gola M. Can Homes Affect Well-Being? A Scoping Review among Housing Conditions, Indoor Environmental Quality, and Mental Health Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Jan [cited 2025 Sep 21];19(23):15975. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/23/15975.

- Atkinson L, Beitchman J, Gonzalez A, Young A, Wilson B, Escobar M, et al. Cumulative risk, cumulative outcome: a 20-year longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0127650.

- Boyle J, Ward MH, Cerhan JR, Rothman N, Wheeler DC. Estimating mixture effects and cumulative spatial risk over time simultaneously using a Bayesian index low-rank kriging multiple membership model. Stat Med. 2022 Dec 20;41(29):5679–97.

- Hines DE, Edwards SW, Conolly RB, Jarabek AM. A Case Study Application of the Aggregate Exposure Pathway (AEP) and Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) Frameworks to Facilitate the Integration of Human Health and Ecological End Points for Cumulative Risk Assessment (CRA). Environ Sci Technol. 2018 Jan 16;52(2):839–49.

- Lucyk K, McLaren L. Taking stock of the social determinants of health: A scoping review. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2017 May 11 [cited 2025 Sep 21];12(5):e0177306. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0177306.

- Braubach M, Fairburn J. Social inequities in environmental risks associated with housing and residential location--a review of evidence. Eur J Public Health. 2010 Feb;20(1):36–42.

- Chimed-Ochir O, Ikaga T, Ando S, Ishimaru T, Kubo T, Murakami S, et al. Effect of housing condition on quality of life. Indoor Air. 2021 Jul;31(4):1029–37.

- Pineo H, Clifford B, Eyre M, Aldridge RW. Health and wellbeing impacts of housing converted from non-residential buildings: A mixed-methods exploratory study in London, UK. Wellbeing, Space and Society [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Sep 21];6:100192. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666558124000101.

- Cartwright A, Khalatbari-Soltani S, Zhang Y. Housing conditions and the health and wellbeing impacts of climate change: A scoping review. Environ Res. 2025 Apr 1;270:120846.

- Favorite X, Cisneros J, Kendrick A, O’Quinn M, Mayo E, Roberts C, et al. The West Dallas environmental health project: the importance of community health experiences related to air pollution. Front Public Health. 2025;13:1613899.

- Park GR, Seo BK. Revisiting the relationship among housing tenure, affordability and mental health: Do dwelling conditions matter? Health Soc Care Community. 2020 Nov;28(6):2225–32.

- Phillips DR, Siu O ling, Yeh AGO, Cheng KHC. The impacts of dwelling conditions on older persons’ psychological well-being in Hong Kong: the mediating role of residential satisfaction. Soc Sci Med. 2005 Jun;60(12):2785–97.

- Ige J, Pilkington P, Orme J, Williams B, Prestwood E, Black D, et al. The relationship between buildings and health: a systematic review. J Public Health (Oxf) [Internet]. 2019 Jun [cited 2025 Sep 21];41(2):e121–32. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6645246/.

- Liddell C, Guiney C. Living in a cold and damp home: frameworks for understanding impacts on mental well-being. Public Health. 2015 Mar;129(3):191–9.

- Harris KM. Mapping inequality: Childhood asthma and environmental injustice, a case study of St. Louis, Missouri. Soc Sci Med. 2019 Jun;230:91–110.

- Ward P, Flores A, Rojas A, Ruiz M. THE INTERSECTION BETWEEN THE DWELLING ENVIRONMENT AND HEALTH AND WELLBEING IN IMPOVERISHED RURAL PUEBLA, MEXICO. THE INTERSECTION BETWEEN THE DWELLING ENVIRONMENT AND HEALTH AND WELLBEING IN IMPOVERISHED RURAL PUEBLA, MEXICO. 2021.

- Howden-Chapman P, Crane J, Chapman R, Fougere G. Improving health and energy efficiency through community-based housing interventions. Int J Public Health. 2011 Dec;56(6):583–8.

- Chakraborty T, Hsu A, Manya D, Sheriff G. Disproportionately higher exposure to urban heat in lower-income neighborhoods: A multi-city perspective. Environmental Research Letters. 2019 Oct 1;14.

- Renteria R, Grineski S, Collins T, Flores A, Trego S. Social disparities in neighborhood heat in the Northeast United States. Environ Res. 2022 Jan;203:111805.

- Frazenburg C, Sepadi MM, Chitakira M. Investigating the Disproportionate Impacts of Air Pollution on Vulnerable Populations in South Africa: A Systematic Review. Atmosphere [Internet]. 2025 Jan [cited 2025 Sep 21];16(1):49. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4433/16/1/49.

- Chatkin J, Correa L, Santos U. External Environmental Pollution as a Risk Factor for Asthma. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2022 Feb;62(1):72–89.

- Geldsetzer P, Fridljand D, Kiang MV, Bendavid E, Heft-Neal S, Burke M, et al. Disparities in air pollution attributable mortality in the US population by race/ethnicity and sociodemographic factors. Nat Med. 2024 Oct;30(10):2821–9.

- Illgner T, Lad N. Data to improve air quality environmental justice outcomes in South Chicago. Front Public Health. 2022;10:977948.

- Palinkas LA, De Leon J, Yu K, Salinas E, Fernandez C, Johnston J, et al. Adaptation Resources and Responses to Wildfire Smoke and Other Forms of Air Pollution in Low-Income Urban Settings: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Apr 4;20(7):5393.

- Adams K, Knuth CS. The effect of urban heat islands on pediatric asthma exacerbation: How race plays a role. Urban Climate [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Sep 21];53:101833. Available from: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2024UrbCl..5301833A.

- Brewer M, Kimbro RT, Denney JT, Osiecki KM, Moffett B, Lopez K. Does neighborhood social and environmental context impact race/ethnic disparities in childhood asthma? Health Place [Internet]. 2017 Mar [cited 2025 Sep 21];44:86–93. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6728803/.

- Khan RN, Saporito AF, Zenon J, Goodman L, Zelikoff JT. Traffic-related air pollution in marginalized neighborhoods: a community perspective. Inhal Toxicol. 2024 May;36(5):343–54.

- Dialesandro J, Brazil N, Wheeler S, Abunnasr Y. Dimensions of Thermal Inequity: Neighborhood Social Demographics and Urban Heat in the Southwestern U.S. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jan 22;18(3):941.

- Yin Y, He L, Wennberg PO, Frankenberg C. Unequal exposure to heatwaves in Los Angeles: Impact of uneven green spaces. Science Advances [Internet]. 2023 Apr 28 [cited 2025 Sep 21];9(17):eade8501. [CrossRef]

- WHO & UNICEF. 1 in 4 people globally still lack access to safe drinking water—WHO, UNICEF [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/26-08-2025-1-in-4-people-globally-still-lack-access-to-safe-drinking-water---who--unicef.

- Abanyie SK, Amuah EEY, Douti NB, Antwi MN, Fei-Baffoe B, Amadu CC. Sanitation and waste management practices and possible implications on groundwater quality in peri--urban areas, Doba and Nayagenia, northeastern Ghana. Environmental Challenges [Internet]. 2022 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Sep 21];8:100546. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667010022001032.

- Wang T, Sun D, Zhang Q, Zhang Z. China’s drinking water sanitation from 2007 to 2018: A systematic review. Sci Total Environ. 2021 Feb 25;757:143923.

- Bain R, Johnston R, Slaymaker T. Drinking water quality and the SDGs. npj Clean Water. 2020 Dec 1;3.

- Ondieki JK, Akunga DN, Warutere PN, Kenyanya O. Socio-demographic and water handling practices affecting quality of household drinking water in Kisii Town, Kisii County, Kenya. Heliyon [Internet]. 2022 May 1 [cited 2025 Sep 21];8(5):e09419. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844022007071.

- Prüss-Ustün A, Wolf J, Bartram J, Clasen T, Cumming O, Freeman MC, et al. Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene for selected adverse health outcomes: An updated analysis with a focus on low- and middle-income countries. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2019 Jun;222(5):765–77.

- Wolf J, Prüss-Ustün A, Cumming O, Bartram J, Bonjour S, Cairncross S, et al. Assessing the impact of drinking water and sanitation on diarrhoeal disease in low- and middle-income settings: systematic review and meta-regression. Trop Med Int Health. 2014 Aug;19(8):928–42.

- Sheingold SH, Zuckerman RB, Lew ND, Chappel A. Social Determinants of Health, Quality of Public Health Data, and Health Equity in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2023 Dec;113(12):1301–8.

- Bullard RD, Mohai P, Saha R, Wright B. Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty: Why Race Still Matters After All of These Years. Environmental Law [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2025 Sep 21];38(2):371–411. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43267204.

- Mohai P, Saha R. Which came first, people or pollution? Assessing the disparate siting and post-siting demographic change hypotheses of environmental injustice. Environ Res Lett [Internet]. 2015 Nov [cited 2025 Sep 21];10(11):115008. [CrossRef]

- Njoku PO, Edokpayi JN, Odiyo JO. Health and Environmental Risks of Residents Living Close to a Landfill: A Case Study of Thohoyandou Landfill, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2019 Jun [cited 2025 Sep 21];16(12):2125. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6617357/.

- Palmiotto M, Fattore E, Paiano V, Celeste G, Colombo A, Davoli E. Influence of a municipal solid waste landfill in the surrounding environment: toxicological risk and odor nuisance effects. Environ Int. 2014 Jul;68:16–24.

- Vinti G, Bauza V, Clasen T, Medlicott K, Tudor T, Zurbrügg C, et al. Municipal Solid Waste Management and Adverse Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Apr 19 [cited 2025 Sep 21];18(8):4331. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8072713/.

- Brender JD, Maantay JA, Chakraborty J. Residential Proximity to Environmental Hazards and Adverse Health Outcomes. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2011 Dec [cited 2025 Sep 21];101(Suppl 1):S37–52. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3222489/.

- Schütt M. Systematic Variation in Waste Site Effects on Residential Property Values: A Meta-Regression Analysis and Benefit Transfer. Environ Resource Econ [Internet]. 2021 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Sep 21];78(3):381–416. [CrossRef]

- Fisher MR. 6.5 Case Study: The Love Canal Disaster. 2017 [cited 2025 Sep 21]; Available from: https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/envirobiology/chapter/6-4-case-study-the-love-canal-disaster/.

- Johns Hopkins University. The Shocking Hazards of Louisiana’s Cancer Alley | Johns Hopkins | Bloomberg School of Public Health [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 21]. Available from: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2025/the-shocking-hazards-of-louisianas-cancer-alley.

- Kaiser R, Le Tertre A, Schwartz J, Gotway CA, Daley WR, Rubin CH. The Effect of the 1995 Heat Wave in Chicago on All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2007 Apr [cited 2025 Sep 21];97(Suppl 1):S158–62. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1854989/.

- World Health Organisation. Ambient (outdoor) air pollution [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health.

- Voelkel J, Hellman D, Sakuma R, Shandas V. Assessing Vulnerability to Urban Heat: A Study of Disproportionate Heat Exposure and Access to Refuge by Socio-Demographic Status in Portland, Oregon. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Mar 30;15(4):640.

- Berger T, Chundeli FA, Pandey RU, Jain M, Tarafdar AK, Ramamurthy A. Low-income residents’ strategies to cope with urban heat. Land Use Policy [Internet]. 2022 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Sep 21];119:106192. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837722002198.

- Botelho JC, Kato K, Wong LY, Calafat AM. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) exposure in the U.S. population: NHANES 1999–March 2020. Environ Res [Internet]. 2025 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Sep 21];270:120916. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12082571/.

- Predieri B, Alves CAD, Iughetti L. New insights on the effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on children. J Pediatr (Rio J) [Internet]. 2021 Dec 15 [cited 2025 Sep 21];98(Suppl 1):S73–85. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9510934/.

- Tanner EM, Hallerbäck MU, Wikström S, Lindh C, Kiviranta H, Gennings C, et al. Early prenatal exposure to suspected endocrine disruptor mixtures is associated with lower IQ at age seven. Environ Int. 2020 Jan;134:105185.

- Schug TT, Blawas AM, Gray K, Heindel JJ, Lawler CP. Elucidating the links between endocrine disruptors and neurodevelopment. Endocrinology. 2015 Jun;156(6):1941–51.

- Yang Z, Zhang J, Wang M, Wang X, Liu H, Zhang F, et al. Prenatal endocrine-disrupting chemicals exposure and impact on offspring neurodevelopment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurotoxicology. 2024 Jul;103:335–57.

- Landrigan P, Garg A, Droller DBJ. Assessing the effects of endocrine disruptors in the National Children’s Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2003 Oct;111(13):1678–82.

- Meeker JD. Exposure to Environmental Endocrine Disruptors and Child Development. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med [Internet]. 2012 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Sep 21];166(6):E1–7. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3572204/.

- O’Shaughnessy KL, Fischer F, Zenclussen AC. Perinatal exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals and neurodevelopment: How articles of daily use influence the development of our children. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Sep;35(5):101568.

- Harada M. Minamata disease: methylmercury poisoning in Japan caused by environmental pollution. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1995;25(1):1–24.

- Finn S, O’Fallon L. The Emergence of Environmental Health Literacy—From Its Roots to Its Future Potential. Environmental Health Perspectives [Internet]. 2017 Apr [cited 2025 Sep 21];125(4):495–501. [CrossRef]

- Kitole FA, Ojo TO, Emenike CU, Khumalo NZ, Elhindi KM, Kassem HS. The Impact of Poor Waste Management on Public Health Initiatives in Shanty Towns in Tanzania. Sustainability [Internet]. 2024 Jan [cited 2025 Sep 21];16(24):10873. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/16/24/10873.

- Okpara DA, Kharlamova M, Grachev V. Proliferation of household waste irregular dumpsites in Niger Delta region (Nigeria): unsustainable public health monitoring and future restitution. Sustainable Environment Research [Internet]. 2021 Jan 7 [cited 2025 Sep 21];31(1):4. [CrossRef]

- Almeida LS, Cota ALS, Rodrigues DF. Sanitation, Arboviruses, and Environmental Determinants of Disease: impacts on urban health. Cien Saude Colet. 2020 Oct;25(10):3857–68.

- Boadi KO, Kuitunen M. Environmental and health impacts of household solid waste handling and disposal practices in third world cities: the case of the Accra Metropolitan Area, Ghana. J Environ Health. 2005 Nov;68(4):32–6.

- Mphasa M, Ormsby MJ, Mwapasa T, Nambala P, Chidziwisano K, Morse T, et al. Urban waste piles are reservoirs for human pathogenic bacteria with high levels of multidrug resistance against last resort antibiotics: A comprehensive temporal and geographic field analysis. Journal of Hazardous Materials [Internet]. 2025 Feb 15 [cited 2025 Sep 21];484:136639. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304389424032205.

- Wankhede P, Wanjari M. Health Issues and Impact of Waste on Municipal Waste Handlers: A Review. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International [Internet]. 2021 Oct 23 [cited 2025 Sep 21];577–81. Available from: https://journaljpri.com/index.php/JPRI/article/view/3746.

- Piarroux R, Moore S, Rebaudet S. Cholera in Haiti. La Presse Médicale [Internet]. 2022 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Sep 21];51(3):104136. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S075549822200029X.

- Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health. 2013 Oct;38(5):976–93.

- Chukmaitov A, Dahman B, Garland SL, Dow A, Parsons PL, Harris KA, et al. Addressing social risk factors in the inpatient setting: Initial findings from a screening and referral pilot at an urban safety-net academic medical center in Virginia, USA. Prev Med Rep [Internet]. 2022 Jul 28 [cited 2025 Sep 21];29:101935. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9501992/.

- Echeverria NJ, Mandalapu SA, Kaufman A, Yu D, Lu X, Ramsey FV, et al. The Impact of Education Level, Access to Transportation, and the Home Environment on Patient-Reported Outcomes after Orthopaedic Trauma Surgery. SurgiColl [Internet]. 2023 Sep 22 [cited 2025 Sep 21];1(3). Available from: https://surgicoll.scholasticahq.com/article/84890-the-impact-of-education-level-access-to-transportation-and-the-home-environment-on-patient-reported-outcomes-after-orthopaedic-trauma-surgery.

- Perez NP, Ahmad H, Alemayehu H, Newman EA, Reyes-Ferral C. The impact of social determinants of health on the overall wellbeing of children: A review for the pediatric surgeon. J Pediatr Surg. 2022 Apr;57(4):587–97.

- Frank LD, Iroz-Elardo N, MacLeod KE, Hong A. Pathways from built environment to health: A conceptual framework linking behavior and exposure-based impacts. Journal of Transport & Health [Internet]. 2019 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Sep 21];12:319–35. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214140518303360.

- Hystad P, Willis M, Hill E, Schrank D, Molitor J, Larkin A, et al. Impacts of Vehicle Emission Regulations and Local Congestion Policies on Birth Outcomes Associated with Traffic Air Pollution. Res Rep Health Eff Inst [Internet]. 2025 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Sep 21];2025:223. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12070800/.

- Schillinger D. Social Determinants, Health Literacy, and Disparities: Intersections and Controversies. Health Lit Res Pract [Internet]. 2021 Jul 8 [cited 2025 Sep 21];5(3):e234–43. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8356483/.

- Carducci A, Fiore M, Lorini C, Federigi I, Verani M, Ferrante M, et al. Environmental Health Literacy: an index to study its relations with pro-environmental behaviors. Eur J Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Oct 25 [cited 2025 Sep 21];32(Suppl 3):ckac130.074. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9593461/.

- Tutu RA, Busingye JD. Health Literacy of Migrants: Environmental Risks to Health. In: Tutu RA, Busingye JD, editors. Migration, Social Capital, and Health: Insights from Ghana and Uganda [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 21]. p. 71–96. [CrossRef]

- Davis LF, Ramirez-Andreotta MD, McLain JET, Kilungo A, Abrell L, Buxner S. Increasing Environmental Health Literacy through Contextual Learning in Communities at Risk. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Oct 9;15(10):2203.

- Finn S, O’Fallon L. The Emergence of Environmental Health Literacy—From Its Roots to Its Future Potential. Environ Health Perspect [Internet]. 2017 Apr [cited 2025 Sep 21];125(4):495–501. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5382009/.

- Marsili D, Pasetto R, Iavarone I, Fazzo L, Zona A, Comba P. Fostering Environmental Health Literacy in Contaminated Sites: National and Local Experience in Italy From a Public Health and Equity Perspective. Front Commun [Internet]. 2021 Sep 16 [cited 2025 Sep 21];6. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/communication/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.697547/full.

- Zaveri B, Panda AK, Hemanth KR, Dev S, Mane M, Chandra PP, et al. Evaluating Health Education Programs in Addressing Environmental Health Risks. Health Leadership and Quality of Life [Internet]. 2024 Dec 30 [cited 2025 Sep 21];3. Available from: https://hl.ageditor.ar/index.php/hl/article/view/372.

- Shaffer RM, Sellers SP, Baker MG, de Buen Kalman R, Frostad J, Suter MK, et al. Improving and Expanding Estimates of the Global Burden of Disease Due to Environmental Health Risk Factors. Environmental Health Perspectives [Internet]. 2019 Oct [cited 2025 Sep 21];127(10):105001. [CrossRef]

- Katoch V, Kumar A, Imam F, Sarkar D, Knibbs LD, Liu Y, et al. Addressing Biases in Ambient PM2.5 Exposure and Associated Health Burden Estimates by Filling Satellite AOD Retrieval Gaps over India. Environ Sci Technol. 2023 Dec 5;57(48):19190–201.

- Liang F, Xiao Q, Huang K, Yang X, Liu F, Li J, et al. The 17-y spatiotemporal trend of PM2.5 and its mortality burden in China. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Oct 13;117(41):25601–8.

- Brook JR, Setton EM, Seed E, Shooshtari M, Doiron D, CANUE—The Canadian Urban Environmental Health Research Consortium. The Canadian Urban Environmental Health Research Consortium—a protocol for building a national environmental exposure data platform for integrated analyses of urban form and health. BMC Public Health. 2018 Jan 8;18(1):114.

- US EPA O. Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act 1990-2020, the Second Prospective Study [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 Sep 21]. Available from: https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/benefits-and-costs-clean-air-act-1990-2020-second-prospective-study.

- Gould E. Childhood lead poisoning: conservative estimates of the social and economic benefits of lead hazard control. Environ Health Perspect. 2009 Jul;117(7):1162–7.

- Johnson S, Haney J, Cairone L, Huskey C, Kheirbek I. Assessing Air Quality and Public Health Benefits of New York City’s Climate Action Plans. Environ Sci Technol. 2020 Aug 18;54(16):9804–13.

- Finn S, O’Fallon L. The Emergence of Environmental Health Literacy—From Its Roots to Its Future Potential. Environ Health Perspect [Internet]. 2017 Apr [cited 2025 Sep 21];125(4):495–501. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5382009/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).