‡ Both names are senior authors of this article.

Abstract

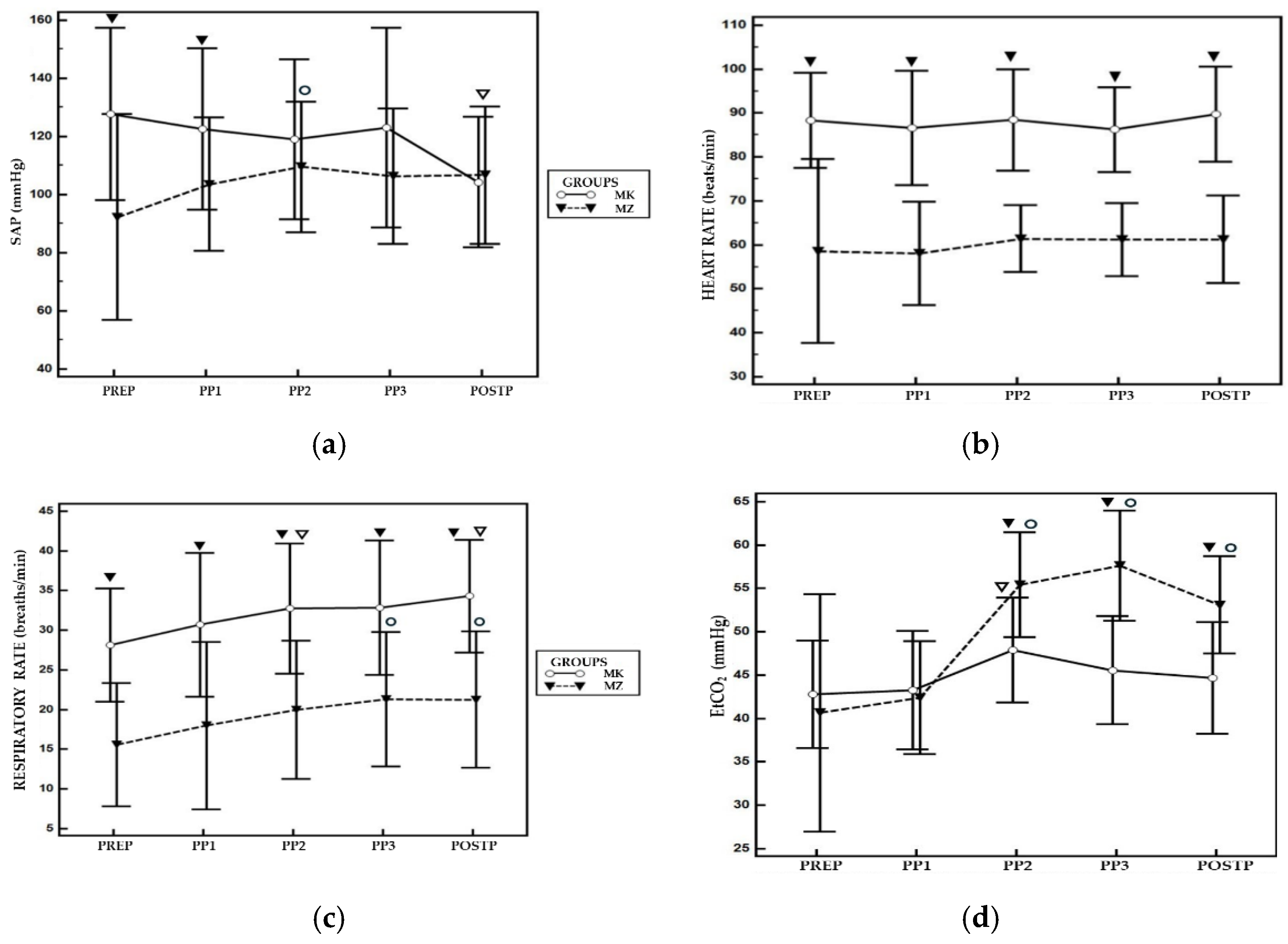

Laparoscopic salpingectomy is a mini-invasive surgery that requires careful anaesthesiologic management due to impact of pneumoperitoneum. In this retrospective study baboons (Papio Hamadryas) were treated with two sedative protocols: medetomidine-ketamine (MK; n=14) or medetomidine-tiletamine-zolazepam (MZ; n=12) via intramuscular injection. A laryngeal mask (LMA) was used for airway management and anaesthesia was maintained with isoflurane. For statistical analysis were considered and analysed via two-way ANOVA: heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), systolic, diastolic and mean arterial blood pressure (SAP, DAP, MAP), end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO₂) and peripheral saturation (SpO₂) recorded five minutes before pneumoperitoneum (PREP), immediately after abdominal insufflation (PP1), at 10 (PP2), 20 (PP3) minutes post-insufflation and 5 minutes after pneumoperitoneum interruption (POSTP). HR and RR were statistically significantly higher (p < 0.05) in MK group compared to MZ group at all time points of the study. EtCO₂ was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in MZ group at PP2, PP3, and POSTP time points. The incidence of hypotension was significantly greater in MZ group (45.5%) compared to MK group (6.25%). Hypercapnia was observed in all baboons sedated with MZ protocol compared to 12.5% of MK group. As a result, MK protocol provides greater cardiorespiratory stability during laparoscopic surgery.

1. Introduction

Papio hamadryas baboons are the largest non-anthropomorphic monkeys, which belong to the Old-World monkey family. Males typically weigh between 17 and 30 kg, while females range from 10 to 17 kg. Wild female populations reach sexual maturity at around four years of age and the length of interbirth intervals is two years thereafter. The female reproductive cycle averages 30 days, and the ovulation period may be identified by observing tumescence of the genital area [

1,

2,

3].

Baboons raised in captivity require a birth control program. Various methods can be used in females, including pharmacological contraceptive treatments or salpingectomy surgery [

4,

5,

6]. Pharmacological contraceptive methods are time-consuming and need to be administered regularly, whereas salpingectomy requires a surgical procedure and careful postoperative care. For this reason, laparoscopic surgery could be considered an option to reduce postoperative complications related to wound management and has already been shown to be highly successful in baboons [

7].

During laparoscopic procedure, the increased intra-abdominal pressure determines the compression of abdominal aorta, inferior vena cava and splanchnic vessels. This results in an increase of systemic vascular resistance (SVR), that in euvolemic patient is observed with a rise of mean arterial pressure (MAP), and a reduction in cardiac output (CO) due to a decrease in venous return [

8,

9]. The use of carbon dioxide (CO2) to achieve pneumoperitoneum determines an increase of arterial CO₂ partial pressure (PaCO₂). Additionally, the elevated intra-abdominal pressure displaces cranially diaphragm, reducing pulmonary compliance, which leads to a pulmonary atelectasis, decrease in tidal volume, and further contributes to the rise in CO

2 levels [

10,

11]. The combination of these mechanisms induces a compensatory increase in respiratory rate [

12].

Therefore, ensuring optimal anaesthetic management is fundamental to minimize physiological impact during laparoscopic surgery; however, in scientific literature few data have been reported in non-human primates (NHPs), particularly in baboons [

5,

13].

Several molecules are suggested by EAZA guidelines to anesthetize and immobilize baboons [

2,

14]. Among the principal molecules available there are dissociative agents which act as non-competitive N-methyl-D aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist. Ketamine hydrochloride and tiletamine hydrochloride are the principal compounds, their use has been explored in baboon’s anaesthesia especially in experimental field [

15,

16,

17]. They are characterised by optimal immobilization, marked muscle rigidity and cardiovascular stimulant effects. Compared to ketamine, tiletamine has a faster onset of action and longer duration. It is commercially available in a combined formulation with zolazepam [

18,

19]. Other benzodiazepine, such as midazolam, are commonly administered in NHPs either orally as anxiolytic before anaesthesia induction or combined with dissociative molecules and opioids via parenteral administration, in which case respiratory depression may occur [

20,

21,

22]. Dissociative agents are also combined with α2-agonist to achieve smooth sedation, optimal muscle relaxation and enhanced analgesia. Among this, medetomidine is characterised by a highly selective α2 adrenergic receptor. Its employment has been widely explored in NHPs, including baboons [

6,

23,

24]. Administering atipamezole, its corresponding antagonist, improves the safety margin [

25,

26].

Recently, Scardia et al. investigated the combination medetomidine/tiletamine-zolazepam during laparoscopic surgery [

13]. No data are currently available in the literature documenting the impact of other drugs during laparoscopic procedures in baboons.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the use of two different anaesthetic protocols employed in a control population program in a baboon’s troop, involving laparoscopic salpingectomy.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective study collected results based on a clinical observational study approved by the Ethical Committee for Clinical studies by Section of Veterinary Clinics and Animal Production, Department of Precision and Regenerative Medicine and Ionian Area (DiMePre-J) of University of Bari “Aldo Moro” (Approval num: 05/2020).

2.1. Animals

Baboons hosted at ZooSafari (Fasano, BA, Italy) underwent elective laparoscopic salpingectomy for a population control program, performed by an experienced veterinary surgeon. Animals received two different anaesthetic protocols based on the specific experience of the two veterinarians in charge for the procedures. For this reason, the allocation of the animals in the two protocols was not randomised. With the assistance of the zoo’s keepers, a harem was isolated from the main group and transferred in a designated area for three days prior to the scheduled surgery.

2.2. Anesthetic Management

Each animal was individually identified by its microchip number, they were fasted for 15 hours, with water allowed until 8 hours prior to surgery. They were restrained in a crush cage, and sedative drugs were administered via intramuscular injection. The two anaesthetic protocols employed were as follows: ketamine (Ketavet 100 100 mg/mL, MSD Animal Health S.r.l, Milano, Italia) (3–7 mg/kg) combined with medetomidine (Domitor 1 mg/mL, Zoetis s.r.l., Rome, Italy) (50–100 µg/kg) for the first group (MK group); and tiletamine-zolazepam (Zoletil 100 mg/mL, Virbac S.r.l., Milan, Italy) (2 to 4 mg/kg) combined with medetomidine (20–60 µg/kg) for the second group (MZ group). Drug dosages were calculated based on estimated weight and adjusted according to the experience of the zoo veterinarian, and the accurate body weights were obtained once the animals were deeply sedated.

A 22-gauge venous catheter was placed in the cephalic vein, and following induction, a blood sample was collected for complete blood count and biochemical profile analysis.

Animals were positioned in dorsal recumbency on the surgical table and propofol (PropoVet, Zoetis Italia S.r.l., Rome, Italy) was administered to achieve an adequate jaw tone for the placement of a laryngeal mask (LMA Supreme™, The Laryngeal Mask Company Limited, Le Rocher, Victoria, Mahe, Seychelles) appropriately sized for each animal (size 1: <5 kg; size 2: 10–20 kg) [

13]. The LMA was inserted with gentle caudal pressure until resistance was felt, then the cuff was inflated. Proper positioning and seal were verified for each animal by closing the adjustable pressure-limiting (APL) valve and squeezing the reservoir bag to achieve an airway pressure of 20 cmH

2O, checking for any air leakage. Confirmation of adequate positioning was also obtained by observing an adequate capnographic waveform. A maximum of two attempts were allowed for laryngeal mask placement; in case of failure, endotracheal intubation was performed.

Baboons were connected to a rebreathing circuit with spontaneous ventilation. Isoflurane vaporizer (IsoFlo®, Zoetis Italia S.r.l., Roma, Italia) was set between 1 and 1.5% and adjusted according to anaesthetic depth. A mainstream capnograph (EMMA® capnograph, Masimo Corporation 52 Discovery, Irvine, CA, USA) was used to measure end-tidal carbon dioxide concentration (EtCO2) and respiratory rate (RR). A multiparametric monitor (Compact 5, medical ECONET, Im Erlengrund 20, Oberhausen, Germany) recorded heart rate (HR), systolic (SAP), diastolic (DAP), and mean arterial pressure (MAP) using the oscillometric method. A pulse oximeter was applied to the tongue to assess peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2). The adequacy of the anaesthetic plan was monitored by evaluating jaw tone, palpebral reflex, eye position, and hemodynamic parameters. All animals received a Ringer’s solution IV (5 ml/kg/h) (Ringer Lattato, Fresenius Kabi, Mirandola, Italy), meloxicam (Metacam, Boehringer Ingelheim, Milan, Italy) at 0.2 mg/kg IV and cefazoline (Cefazolina Teva, Teva) at 20 mg/kg IV as standard preoperative treatment. Once an adequate depth of anaesthesia was achieved, the surgical procedure started. During the surgical procedure intrabdominal pressure was maintained between 6-8 mmHg. As rescue analgesia was administered a bolus of fentanyl (2 mcg/kg IV) (Fentadon, Dechra Veterinary Products, Turin, Italy) in case of a sudden increase (>30%) of RR and/or MAP and/or HR.

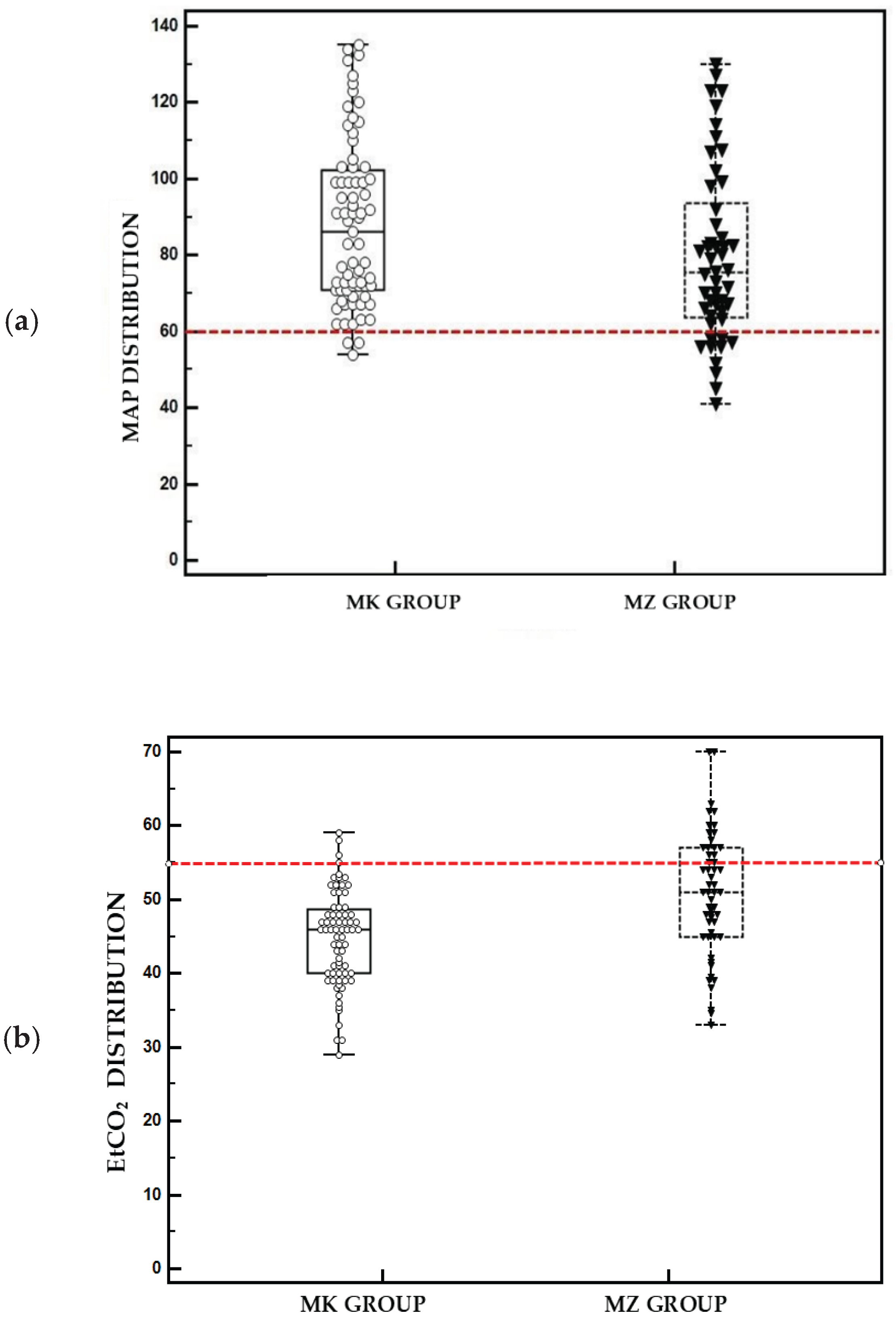

Hypotensive episodes were identified with a mean arterial pressure (MAP) below 60 mmHg for more than 5 minutes and resolved by adjusting the depth of anaesthesia and/or administering maximum two fluid boluses of Ringer’s lactate solution (5ml/kg over 10 minutes). In case of patient not fluid responder, dopamine was infused (5-9 mcg/kg/min). Hypercapnia was defined as a value of EtCO2 above 55 mmHg, and manual intermittent positive pressure ventilation was started in case of EtCO2 > 65 mmHg, RR < 5 and SpO2 < 95%. At the end of procedure isoflurane was interrupted and the animals were positioned in lateral recumbency and treated with Ivermectin (Ivomec, Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health Italia S.p.a., Milano, Italia) 0.2 mg/kg SC, and amoxicillin (Betamox LA, Vétoquinol Italia S.r.l., Bertinoro, Italia) 25 mg/kg IM.

The laryngeal cuff was deflated and removed when the palpebral reflex reappeared, and the animals were transferred to a warm recovery area and monitored up to full recovery with the gain of standing position.

2.3. Statistics

All physiological parameters (HR, SAP, MAP, DAP, EtCO₂, RR and SpO2) were considered at specific time points: five minutes before pneumoperitoneum (PREP), immediately after abdomen insufflation (PP1), at 10 minutes (PP2) and twenty minutes (PP3) from the start of surgery, and 5 minutes after pneumoperitoneum interruption (POSTP). The parameters analysed were as follows: HR, SAP, MAP, DAP, EtCO₂, RR and SpO₂. All recorded parameters were statistically analysed with MedCalc 12.7.0.0. software. Normal distribution of data collected during each study time was confirmed with Shapiro-Wilk test. Mean value and confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated for all data. Physiological parameters were compared for the different time interval between the two groups via two-way ANOVA test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Twenty-eight baboons, weighing between 4 and 15 kg, were considered for the purposes of this study. The MZ protocol was applied in 12 animals, while in the remaining 16 cases, the MK protocol was used. All animals completed the study without complications. The mean body weight was 9.6 kg (95% CI: 7.3–11.9) in the MZ group and 10.7 kg (95% CI: 9.7–11.6) in the MK group.

In the MZ group, the effective dosage of tiletamine-zolazepam ranged from 2.3 to 10.4 mg/kg (mean: 4.4 mg/kg, 95% CI: 2.8–6.1), while medetomidine ranged from 0.01 to 0.04 mg/kg (mean: 0.02 mg/kg, 95% CI: 0.017–0.03). In the MK group, ketamine was administered at doses ranging from 3 to 7 mg/kg (mean: 4.37 mg/kg, 95% CI: 3.6–5.15), and medetomidine from 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg (mean: 0.08 mg/kg, 95% CI: 0.063–0.09). The placement of the LMA was performed without complications and endotracheal intubation was never required. The mean surgical time was 36.5 minutes in the MZ group (95% CI: 30.5–42.5) and 27 minutes in the MK group (95% CI: 24–30).

The mean values and CI 95% for HR, MAP, RR, EtCO₂ and SpO₂ for both groups are reported in

Table 1. A statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups for SAP, the MK group showed higher values compared to the MZ group at PREP and PP1. Within the same group, compared to PREP, MZ protocol exhibited higher values of SAP at PP2 while the MK group showed lower values at POSTP (

Figure 1a). Regarding HR, the MK group showed higher values compared to MZ group at all timepoints during the study (

Figure 1b).

For RR, the MK group showed significantly higher values during entire study times compared to MZ group. Within the same group, compared to PREP, MK group showed higher RR values at PP2 and POSTP, while the MZ group at PP3 and POSTP (

Figure 1c). EtCO₂ levels were significantly higher in the MZ group at PP2, PP3, and POSTP compared to PREP, conversely in MK group was observed a significant higher value at PP2 compared PREP. A statistical difference was observed between two groups, with a higher value of EtCO

2 at PP2, PP3 and POSTP for MZ group (

Figure 1d). For all other parameters analysed, no statistically significant differences were reported between the two groups. None of the animals required rescue analgesia during the surgical procedure.

In the MZ group, 5 out of 12 baboons (41.6%) experienced transient hypotension episodes during pneumoperitoneum, which were resolved by adjusting the depth of the anaesthetic plane and administering fluid boluses. The incidence of hypotension was significantly lower in the MK group, with only 1 episode recorded among 16 animals (6.25%). At least one episode of hypercapnia was recorded in all cases of the MZ group, while in the MK group, the incidence was significantly lower (p < 0.001), with 2 of 16 animals (12.5%) affected. Nevertheless, no animal required manual assisted ventilation.

Figure 2 shows box plots representing the distribution of hypercapnia and hypotension episodes in the patients throughout the different time points of the study. Recovery was uneventful for all animals, within one hour of the end of the surgery.

4. Discussion

Considering the physiological alterations associated with laparoscopic surgery, the use of medetomidine–ketamine (MK) protocol resulted in a lower impact on both respiratory and cardiovascular functions compared to medetomidine–tiletamine–zolazepam (MZ) protocol during laparoscopic salpingectomy in baboons.

Despite the theoretical increase of MAP during pneumoperitoneum and sympathomimetic action of dissociative agents, the MZ group showed a higher incidence of hypotension and a significantly lower SAP trend across intraoperative time points. Heart rate was also significantly lower in MZ group compared to MK group.

This finding may also be attributed at the typically behavior of α2-agonist on the heart rate, an effect that appears to be more pronounced in combination with tiletamine-zolazepam [

27]

. These data align with previous studies, reporting decrease cardiocirculatory performance in NHPs anesthetized with tiletamine-zolazepam [

28,

29].

In this specific study, the absence of mechanical ventilation may have highlighted the different impact of the two protocols on respiratory drive.

During pneumoperitoneum, the physiological response to hypercapnia typically involves an increase of respiratory rate to facilitate CO₂ elimination [

12]. This compensatory mechanism was not evident in the MZ group, as shown in

Figure 1c, indicating the presence of respiratory depression. Consequently, a progressive increase in EtCO₂ was observed during the surgical procedure. Although there was hypoventilation in the MZ group, no hypoxemia (SpO

2 <94%) was recorded at any time during the study; however, this result was achieved through administration of pure oxygen, causing altered representation of peripheral oxygen saturation [

15,

30,

31]

.

Conversely, in the MK group, EtCO₂ levels were better regulated during pneumoperitoneum. It seems that the combination of ketamine-medetomidine showed less interference with the physiological compensatory respiratory drive response to CO₂ insufflation. In

Figure 1d, an increase in ETCO₂ is observed after 10 minutes of pneumoperitoneum, followed by a decrease during the subsequent phase. This reflects the respiratory center sensitivity to rising CO₂ levels. In fact, an increase in respiratory rate was observed, resulting in a corresponding decrease in EtCO₂ (

Figure 1c-d). In this group, mild hypercapnia was observed in only two subjects.

Based on these data, MZ protocol was associated with greater cardiovascular and respiratory depression, resulting in more pronounced physiological alterations compared to the MK group. This negative impact could be attributed to the presence of zolazepam as benzodiazepine. This observation is also supported by previous data reported in the literature on the depressive effects of benzodiazepines in NHPs and other species [

19,

32,

33]

. Benzodiazepines can be considered drugs with a good safety margin when administered alone; however, when combined with other agents, they may enhance negative cardiorespiratory effects [

34]. Their combination with α2-agonist may result in a synergistic action on the central nervous system and increased muscle relaxation, leading to deeper sedation [

29,

35].

Regarding the use of LMA, no patients showed complications during its application. This study confirms findings previously reported in the literature regarding its safety and efficacy in NHPs [

13,

36,

37]. The baboon’s trachea is shorter compared to other primates, which complicates intubation. The use of LMA overcomes this anatomical limitation, facilitating airway management and preventing potential airway damage and infection [

15,

38]. The main risk associated with its application is the possibility of regurgitation, particularly during laparoscopic procedures, which can lead to increased intra-abdominal pressure. This may result in aspiration pneumonia due to airways being patent and unprotected [

39]. However, this risk can be reduced through an adequate fasting period and by using second-generation LMA, which offers improved sealing and safety. In this study no animals presented regurgitation during procedure.

The study presented several limitations. Primarily, its retrospective nature may have influenced data collected, as there was no randomization of patients between the two groups. The drug dosages were not standardized, which may have resulted in variable effect of cardiovascular and respiratory parameters among individuals within the same group. Moreover, due to logistic of the zoo, it was not possible to have a complete and adequate monitoring of the quality of recovery. A recent study by Amati et al. proved that quality of recovery was significantly worst in animals receiving tiletamine [

27].

5. Conclusions

Data collected in this study proved that the combination of medetomidine and ketamine results in less cardiovascular and respiratory depression compared to a combination with tiletamine-zolazepam, in baboons undergoing laparoscopic procedures. Moreover, the study confirms that LMA is a valid and safe alternative to orotracheal intubation in these animals. Further studies are recommended to investigate the effects of this combination on the quality of recovery.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions:

conceptualization, CP, FS; methodology, RP, CP, CV, EB, MS, CA, LL, MG, PL, FS.; software, FS.; validation, FS, PL, LL.,.; formal analysis, EB; FS, RP.; investigation, RP, CP, CV, MS, CA, EB, LL, MG, PL, FS; resources, FS, LL.; data curation, RP, EB, FS; writing—original draft preparation, RP, FS.; writing—review and editing, FS, CP, RP, CV.; visualization, RP, CP, CV, EB, MS, CA, LL, MG, PL, FS; supervision, FS, LL, PL.; project administration, FS, LL.; funding acquisition, FS, LL. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Bari (05/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Please confirm this template revision.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to kindly acknowledge the support of the staff of the Fasano Safari Zoo.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| CI |

Interval confidence |

| CO |

Cardiac output |

| CO2 |

Carbon dioxide |

| DAP |

Diastolic arterial pressure |

| EAZA |

European Association Zoos and Acquaria |

| EtCO2

|

End-tidal carbon dioxide |

| HR |

Heart rate |

| IV |

Intravenous |

| LMA |

Laryngeal Mask airway |

| MAP |

Mean arterial pressure |

| MK |

Medetomidine-ketamine group |

| MZ |

Medetomidine-tiletamine-zolazepam group |

| NHPs |

Non-human primates |

| PaCO2

|

Partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide |

| POSTP |

5 minutes after pneumoperitoneum interruption |

| PP1 |

Immediately after starting pneumoperitoneum |

| PP2 |

Pneumoperitoneum 10 minutes |

| PP3 |

Pneumoperitoneum 20 minutes |

| PREP |

Pre-pneumoperitoneum |

| RR |

Respiratory rate |

| SAP |

Systolic arterial pressure |

| SpO2

|

Peripheral oxygen saturation |

References

- Zinner, D. & Schwibbe, Michael & Kaumanns, Werner. (1994). Cycle synchrony and probability of conception in female hamadryas baboons Papio hamadryas. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology - BEHAV ECOL SOCIOBIOL. 35. 175-183. [CrossRef]

- AZA Baboon Species Survival Plan®. Hamadryas Baboon Care Manual; Association of Zoos and Aquariums: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2020.

- Nitsch, F., Stueckle, S., Stahl, D. & Zinner, D. Copulation patterns in captive hamadryas baboons: a quantitative analysis. Primates 52, 373 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Taberer, T. R., Mead, J., Hartley, M. & Harvey, N. D. Impact of female contraception for population management on behavior and social interactions in a captive troop of Guinea baboons (Papio papio). Zoo Biology 42, 254–267 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Yu, P., Weng, C., Kuo, H. & Chi, C. Evaluation of endoscopic salpingectomy for sterilization of female Formosan macaques (Macaca cyclopis). American J Primatol 77, 359–367 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Reiners JK, Gregersen HA. How to plan and provide general anesthesia for a troop of 98 hamadryas baboons (Papio hamadryas) for contraceptive and preventative health interventions. Am J Vet Res. 2024 May 18;85(7): ajvr.23.12.0274. PMID: 38744308. [CrossRef]

- Lacitignola L, Laricchiuta P, Imperante A, Acquafredda C, Stabile M, Staffieri F. Laparoscopic salpingectomy in Papio hamadryas for birth control in captivity. Vet Surg. 2022 Jul;51 Suppl 1:O98-O106. Epub 2022 Jan 5. PMID: 34985139. [CrossRef]

- Di Bella C, Lacitignola L, Fracassi L, Skouropoulou D, Crovace A, Staffieri F. Pulse Pressure Variation Can Predict the Hemodynamic Response to Pneumoperitoneum in Dogs: A Retrospective Study. Vet Sci. 2019 Feb 20;6(1):17. PMID: 30791578; PMCID: PMC6466147. [CrossRef]

- Odeberg-Wernerman S. Laparoscopic surgery-effects on circulatory and respiratory physiology: an overview. Eur J Surg Suppl. 2000;(585):4-11. PMID: 10885548. [CrossRef]

- Di Bella, C. et al. Effects of two alveolar recruitment maneuvers in an “open-lung” approach during laparoscopy in dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 904673 (2022).

- Jo, Y. Y. & Kwak, H.-J. What is the proper ventilation strategy during laparoscopic surgery? Korean J Anesthesiol 70, 596 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, T. M., Giraud, G. D., Togioka, B. M., Jones, D. B. & Cigarroa, J. E. Cardiovascular and Ventilatory Consequences of Laparoscopic Surgery. Circulation 135, 700–710 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Annalaura Scardia et al. Use of Laryngeal Mask and Anesthetic Management in Hamadryas Baboons (Papio hamadryas) Undergoing Laparoscopic Salpingectomy—A Case Series. Veterinary Sciences 10, 158 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Johann, A. & Brüning, N. EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Gelada Baboon (Theropithecus Gelada). (European Association of Zoos and Aquaria, NL, 2021).

- Monkeys and Gibbons. in Zoo Animal and Wildlife Immobilization and Anesthesia pp. 561–571 (Wiley, 2014). [CrossRef]

- Santerre D, Chen RH, Kadner A, Lee-Parritz D, Adams DH. Anaesthetic management of baboons undergoing heterotopic porcine cardiac xenotransplantation. Vet Res Commun. 2001 May;25(4):251-9. PMID: 11432427. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, K. R. et al. Comparison of indirect and direct blood pressure measurements in baboons during ketamine anaesthesia. J of Medical Primatology 43, 217–224 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. C., Thurmon, J. C., Benson, G. J. & Tranquilli, W. J. Review: Telazol – a review of its pharmacology and use in veterinary medicine. Vet Pharm & Therapeutics 16, 383–418 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. P., Zagon, I. S., Larach, D. R. & Max Lang, C. Cardiovascular and respiratory effects of tiletamine-zolazepam. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 44, 1–8 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Gomes, V. H. et al. Anesthetic effects of isoflurane and fentanyl infusion in capuchin monkeys (Sapajus sp) undergoing salpingectomy or deferentectomy, previously chemically restrained with ketamine–midazolam or ketamine–dexmedetomidine. J of Medical Primatology 52, 149–155 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Lee, V. K., Flynt, K. S., Haag, L. M. & Taylor, D. K. Comparison of the Effects of Ketamine, Ketamine–Medetomidine, and Ketamine– Midazolam on Physiologic Parameters and Anesthesia-Induced Stress in Rhesus (Macaca mulatta) and Cynomolgus (Macaca fascicularis) Macaques. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science 49, (2010).

- Pulley, A. C. S., Roberts, J. A. & Lerche, N. W. FOUR PREANESTHETIC ORAL SEDATION PROTOCOLS FOR RHESUS MACAQUES (MACACA MULATTA). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 35, 497–502 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Jalanka, Harry H., and Bengt O. Roeken. “The Use of Medetomidine, Medetomidine-Ketamine Combinations, and Atipamezole in Nondomestic Mammals: A Review.” Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, vol. 21, no. 3, 1990, pp. 259–82. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20095064.

- Watuwa, J., Mbabazi, R., Sente, C., Musinguzi, J. & Laubscher, L. A retrospective study on the immobilisation of captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) at UWEC, Uganda. Vet Record Case Reports 11, e602 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Vié, J.-C. et al. Anesthesia of wild red howler monkeys (Alouatta seniculus) with medetomidine/ketamine and reversal by atipamezole. Am. J. Primatol. 45, 399–410 (1998).

- Langoi, D.L., P.G. Mwethera, K.S.P. Abelson, I.O. Farah, and H.E. Carlsson. "Reversal of Ketamine/Xylazine combination anesthesia by Atipamezole in olive baboons (Papio anubis)." Journal of Medical Primatology 38.6 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Amari, M. et al. Comparison of Three Different Balanced Sedative-Anaesthetic Protocols in Captive Baboons (Papio hamadryas). Veterinary Sciences 12, 859 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Lee JI, Hong SH, Lee SJ, Kim YS, Kim MC. Immobilization with ketamine HCl and tiletamine-zolazepam in cynomolgus monkeys. J Vet Sci. 2003 Aug;4(2):187-91. PMID: 14610374. [CrossRef]

- Atencia R, Stöhr EJ, Drane AL, Stembridge M, Howatson G, Del Rio PRL, Feltrer Y, Tafon B, Redrobe S, Peck B, Eng J, Unwin S, Sanchez CR, Shave RE. HEART RATE AND INDIRECT BLOOD PRESSURE RESPONSES TO FOUR DIFFERENT FIELD ANESTHETIC PROTOCOLS IN WILD-BORN CAPTIVE CHIMPANZEES (PAN TROGLODYTES). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2017 Sep;48(3):636-644. PMID: 28920777. [CrossRef]

- Tusman G, Bohm SH, Suarez-Sipmann F. Advanced Uses of Pulse Oximetry for Monitoring Mechanically Ventilated Patients. Anesth Analg. 2017 Jan;124(1):62-71. PMID: 27183375. [CrossRef]

- Piemontese C, Stabile M, Di Bella C, Scardia A, Vicenti C, Acquafredda C, Crovace A, Lacitignola L, Staffieri F. The incidence of hypoxemia in dogs recovering from general anesthesia detected with pulse-oximetry and related risk factors. Vet J. 2024 Jun;305:106135. [CrossRef]

- Bucknell P, Dobbs P, Martin M, Ashfield S, White K. Cardiorespiratory effects of isoflurane and medetomidine-tiletamine-zolazepam in 12 bonobos (Pan paniscus). Vet Rec. 2023 Feb;192(4):e2589. Epub 2023 Jan 24. PMID: 36692993. [CrossRef]

- Brown LJ, Jamieson SE. Field Evaluation of Tiletamine-Zolazepam-Medetomidine for Immobilization of Raccoons (Procyon lotor) and Striped Skunks (Mephitis mephitis). J Wildl Dis. 2022 Oct 1;58(4):914-918. PMID: 35951023. [CrossRef]

- Gerak, L. R., Brandt, M. R. & France, C. P. Studies on benzodiazepines and opioids administered alone and in combination in rhesus monkeys: ventilation and drug discrimination. Psychopharmacology 137, 164–174 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Parada, E., Schwartz, H., Lam, A. Y., Baca-Montero, O. & Laubscher, L. Utilisation of dexmedetomidine, ketamine and midazolam for immobilisation and health assessment of captive white-bellied spider monkeys (Ateles belzebuth) in the Amazon rainforest of Iquitos, Peru. Vet Record Case Reports 12, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. A., Atkins, A. L. & Heard, D. J. Application of the Laryngeal Mask Airway for Anesthesia in Three Chimpanzees and One Gibbon. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 41, 535–537 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Cerveny, S. N., D’Agostino, J. J., Davis, M. R. & Payton, M. E. COMPARISON OF LARYNGEAL MASK AIRWAY USE WITH ENDOTRACHEAL INTUBATION DURING ANESTHESIA OF WESTERN LOWLAND GORILLAS (GORILLA GORILLA GORILLA). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 43, 759–767 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Klonner, M. E., Springer, S. & Braun, C. Complications secondary to endotracheal intubation in dogs and cats: A questionnaire-based survey among veterinary anaesthesiologists. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia 50, 220–229 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ip, J. Y. C. & Lo, K.-M. Perioperative management of patients with aspiration risk. Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine 25, 550–554 (2024). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).