1. Introduction

Corporate financial stability is a cornerstone of organisational sustainability, particularly the case as firms increasingly integrate ESG (environmental, social and governance) practices in their strategic framework. Indeed, ESG initiatives have been shown to improve stakeholder trust, long-term competitiveness, resilience, and enhanced market performance (Coşkun, 2023; Tang, 2022; Wang et al., 2024; Yadav & Asongu, 2025; R. Zhang et al., 2021). The benefits of ESG practices are particularly salient in emerging markets, where companies face the dual pressures of achieving economic growth and addressing social and environmental challenges (Krishna et al., 2024). Moreover, the cost of capital and insolvency risks tend to be higher than in emerging markets than in developed markets (Boyer et al., 2017). The emerging market of Brazil, for example, established itself as a prominent leader in sustainability and green finance, backing up its position with a strong commitment to sustainable development, international cooperation, and its prominent role as chair of the G20 international forum of government leaders and central bank presidents in 2024 (Gartia et al., 2024).

While there has been a growth in adopting ESG frameworks, a better understanding of their effects on corporate financial stability in emerging markets is needed, because these markets exhibit unique challenges, including less-predictable market fluctuations, higher cost of debt, and financial risk that increase the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) and the insolvency risk (Altman’s Z-score). Brazil has a strong GDP and has targeted specific ESG goals; however, it also experienced a surge in corporate bankruptcy filings in 2024, affecting some 29% of large companies, with this trend expected to worsen in 2025 (Fernandes, 2024)1. This paradox emphasises two complications: (1) the said benefits of ESG practices may not have an immediate effect, which hampers corporate strategies in fast-moving emerging markets and (2) while ESG practices are presumed to mitigate financial risks, there is clearly a lack of understanding about the specific pathways through which they enhance stability (Bae et al., 2018). Hence, the disconnect between the country’s move toward sustainability and tangible reductions in WACC or insolvency risk in Brazilian firms underscores the need for a deeper understanding of how integrating ESG corporate strategy can address challenges and facilitate financial sustainability in emerging markets like Brazil.

The complication identified above goes beyond theoretical gaps and concerns practical implications because of the dual realities of emerging markets: rapid economic growth and high levels of insolvency risk. Without a clear framework for leveraging ESG practices to mitigate the risks, firms will struggle to sustain long-term performance and resilience. Indeed, the first complication identified above warrants a temporal approach to understanding short- and long-term effects of ESG practices for emerging firms. Moreover, clarifying the link between ESG and key financial metrics (i.e., WACC and insolvency risk) limits the practical utility of ESG strategies in markets that arguably need them the most. Consequently, the present study raises a critical research question: How do ESG practices influence financial stability in a market characterised by systemic challenges?

To examine how ESG practices affect the WACC and the probability of financial distress (insolvency risk), the current study uses a comprehensive dataset– Bloomberg data on Brazilian firms from 2010-2021– and advanced econometric techniques (ordinary least squares, vector autoregressive models, and fully modified ordinary least squares). By looking at firms operating in high-growth, but high-risk environments, and conducting short- and long-term analyses, we offer new perspectives into the financial implications of ESG practices for emerging markets firms.

In this context, the research makes a dual contribution. First, it provides empirical evidence linking ESG practices with dual trade -off behaviors regarding the cost of capital (WACC) and insolvency risk or Altman’s Z-score (AZS). Second, the research deepens the understanding of the impact of ESG practices on financial stability in emerging economies, expanding the existing literature supported by key contributions such as Berg et al. (2020) and Hassan et al. (2023), while integrating recent findings from Ramirez et al. (2022) and Al Azizah & Haron (2025) to contextualise the unique challenges faced in Brazil. In addition, this study shows the importance of contextualising ESG frameworks to align with regional economic and institutional realities.

The article is structured into seven sections. The second section presents the literature review that supports the theoretical framework of the study. The third section describes the methodology and econometric strategy employed. The fourth section details the main results obtained, while the fifth includes the robustness tests that validate the findings. Subsequently, the discussion of the results is developed, and finally, the conclusions of the study are presented.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Studies

The Stakeholder Theory Proposed by Freeman (1984) It postulates a management approach that states that companies, in addition to maximizing shareholder returns, must balance the interests of multiple stakeholders: investors, employees, customers, communities, and regulators in order to sustain positive long-term performance. In this regard, the adoption of ESG practices strengthens the relationship with stakeholders by generating investor confidence, customer loyalty, and employee engagement. In addition, it promotes more resilient value chains, social legitimacy in communities, and regulatory compliance(Zhang et al., 2022). Therefore, a commitment to corporate sustainability can have a positive impact on long-term financial results by reducing operational risk, minimizing agency costs, saving capital costs and improving corporate reputation (Bilivogui & Iqbal, 2025a).

On the other hand, the Resource-Based vision proposed by Barney (1991) It argues that companies can achieve a sustainable competitive advantage by possessing rare, valuable, and inimitable resources. In this framework, the adoption of ESG practices can constitute an intangible element with the potential to generate differentiation and promote value creation in the long term. As they argue Tan & Zhu (2022) and Tunio et al., (2021), companies that invest in environmental innovation, in the well-being of their employees, and in solid corporate governance structures develop capabilities that are difficult for their competitors to replicate. As a result, the ESG approach becomes a strategic resource that reinforces operational resilience and the ability to attract investors, which consequently translates into better financial performance and corporate stability in the long term.

The signaling theory developed by Spence (1973) and later extended to finance, argues that companies send signals to the market to reduce the information asymmetry between managers and investors, so that their strategic decisions reflect the firm's strength and future prospects (Fathi et al., 2025). In this framework, the adoption of ESG practices can be interpreted as a positive sign of commitment to sustainability, non-financial risk management and long-term value creation, which can strengthen investor confidence and improve the perception of financial markets (Itan et al., 2025). From this perspective, the impact of signaling through ESG can translate into a reduction in the cost of capital (WACC) and the probability of bankruptcy as shareholders and creditors perceive less reputational, regulatory and operational risk(Yin et al., 2025).

Based on the Trade-off Theory postulated by Myers (1977), Al Azizah & Haron (2025) they point out that the adoption of ESG strengthens corporate reputation and long-term fiscal durability. However, they warn that the sustainability approach carries significant financial burdens, especially in capital-intensive sectors such as manufacturing, energy, and infrastructure. Therefore, the integration of ESG practices can generate financial tensions in the short term, derived from the initial outlays required in investments such as carbon capture technologies or cleaner waste disposal systems, among others, which affect profitability in the short term. However, in the long term, such investments have the potential to generate regulatory benefits, greater operational efficiency, and increased investor confidence. Consequently, companies must carefully assess the balance between immediate financial costs and future sustainable benefits when maintaining ESG policies.

This study incorporates the vision of the theories previously exposed to analyze how the adoption of ESG practices affects the cost of capital and the risk of insolvency of emerging companies in Brazil, considering the trade-off between short-term and long-term impacts and benefits. About that Testing its relevance not only in developed market corporate contexts, but also in emerging financial markets, is pertinent due to the need to understand how institutional factors, levels of regulatory maturity and limitations on access to capital condition the effectiveness of sustainability strategies(Itan et al., 2025).

2.2. Empirical Studies

2.2.1. ESG Practices and WACC

According to Serebrisky (2014), the advancement of sustainability practices depends on an optimal regulatory and fiscal framework, financial markets and institutions effectively articulated around sustainable initiatives and the creation of sustainability ecosystems. However, there are difficulties that slow down the evolution of ESG practices in emerging markets, such as lower institutional capacity, weak corporate governance and a less favourable business climate. Although some countries have implemented legal reforms related to corporate governance and the stock market, in general, the application and compliance with ESG-related legislation are challenging. Some ESG performance tools and indices have been adapted to national realities to enhance their benefits, however, the misperception that they are expenses and not investments that offer long-term returns in some way remains latent. Consequently, the practical implementation of ESG in the region remains limited.

According to RSM (2023), the adoption of ESG practices in Latin America has lagged behind Europe, North America and Asia, but has also been varied and heterogeneous among companies in the region. Some companies, including Natura and Itau Unibanco, have already started their path towards the implementation of ESG, demonstrating a greater level of progress in these initiatives. On the other hand, other companies have not yet incorporated ESG practices. Despite the above, Cherkasova and Nenuzhenko (2022) identified a gradual increase in the average value of the ESG rating from 2011 to 2019, where international companies showed a higher ESG rating compared to local ones, due to additional sources of capital and pressure from foreign customers, and workers and suppliers who want the implementation and development of ESG activities.

Regarding the effect on the quality of ESG practices and the cost of corporate capital, Hassan et al. (2023) found that non-financial publicly listed companies in eighteen emerging markets manifested a negative and statistically significant association between the interaction of ESG scores and the cost of capital, as well as market risks. These findings suggest that achieving higher ESG scores benefits companies by reducing capital costs and risks in countries with a higher sensitivity to corporate sustainability practices (Dua & Sharma, 2024). Moreover, the benefits are reinforced during periods of exogenous economic shocks, which tend to have more severe consequences in less resilient emerging countries. For Latin American companies, Ramirez et al. (2022) showed that a better ESG score is associated with a lower cost of capital, where only the governance pillar showed a negative relationship, indicating that good governance reduces capital costs by improving financial confidence.

On the other hand, Lavin and Montecinos-Pearce (2022) found that ESG disclosure was directly associated with a lower cost of debt. However, through an indirect channel, ESG disclosure interacts with growth opportunities, increasing the cost of debt due to perceived future risk. Thus, the results show that ESG disclosure influences the cost of financing in opposite directions, highlighting the complex economic implications of these practices in countries that are adopting ESG.

Chau et al., (2025) identify a non-linear, horizontal “S”-shaped relationship between firm value and ESG ratings, revealing that corporate sustainability generates differentiated effects depending on its level of maturity. In the initial stages, improvements in ESG performance enhance firm value; however, after reaching a certain threshold, higher costs and diminishing returns temporarily reduce this value before it recovers as more advanced and strategic practices are consolidated. Similarly, Al Azizah & Haron (2025) report a dynamic shift in the relationship between ESG performance and financial outcomes among firms in emerging markets. Before the pandemic, social (S) and governance (G) factors had a positive influence on profitability and market valuation, while the environmental (E) component showed only a marginal effect. However, in the post-pandemic period, a partial reversal of this trend was observed: the impact of the social component turned negative, the explanatory power of governance weakened, and overall ESG integration exhibited only a weak yet positive correlation with operational efficiency.This dynamic reflects the interaction between growth options and stakeholder influence, while factors such as institutional quality and each country’s environmental sustainability modulate market sensitivity to ESG performance, underscoring the importance of national context in the financial valuation of sustainability.

2.2.2. ESG Practices and Insolvency Risk

According to Hawn & Ioannou (2016), the implementation of sustainable practices can mitigate insolvency risk, as responsible corporate governance is often associated with greater operational stability and lower vulnerability to potential litigation. Moreover, investing in companies that adopt sustainable and socially responsible practices entails lower risk compared to traditional investments, particularly during periods of high financial market volatility (Ortas et al., 2014). Furthermore, Lioui (2018) and Engle et al., (2020) demonstrated that effective management of ESG factors not only contributes to greater sustainability and corporate responsibility but can also significantly reduce financial risk and enhance long-term economic performance.

Cherkasova & Nenuzhenko (2022) found that the region of a company’s headquarters affected the relationship between financial performance and ESG activities, where the most successful companies in developing ESG are international companies, while Latin American companies, both local and multinational, face significant challenges during the implementation of ESG initiatives. On the other hand, Habib (2023) identified that firms implementing a solid cost leadership strategy tend to exhibit superior ESG performance, thereby enhancing their competitiveness and financial resilience. Consequently, both efficient cost management and high sustainability performance negatively influence the likelihood of experiencing financial distress. Furthermore, the study demonstrated that ESG performance acts as a mediating mechanism that mitigates insolvency risk by strengthening operational efficiency, corporate reputation, and investor confidence.

2.3. Formulation of Hypotheses

Brazilian companies have experienced notable growth in the adoption of ESG practices, fostered by various legislative initiatives, the creation of corporate sustainability ecosystems promoted by financial institutions and stock exchanges, and the growing demand for sustainability and social responsibility by both investors and consumers (Meneses et al., 2022). In this regard, Carvalhal & Leal (2005), Moreira et al., (2023), Martins (2022), Roberti & Lanzini (2021) and Santos et al., (2017) provide a comprehensive view of how regulatory, competitive and life cycle factors influence the adoption and management of ESG practices in emerging markets. However, critical questions remain unanswered regarding how effective these practices are in countries that lack a robust regulatory framework, and the perception of high implementation costs may limit their adoption. Therefore, the present study seeks to understand both the short- and long-term effects of ESG practices on financial stability indicators like the WACC and insolvency risk– rarely explored in the literature.

In the context of corporate finance, the quality of ESG practices has emerged as a crucial factor in assessing the financial costs and risks associated with companies. In this regard, the following hypotheses are evaluated for the short- and long-term periods:

2.3.1. Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC)

The quality of ESG practices can influence a company’s WACC by facilitating access to financing, reducing financial risks, and improving reputation and overall performance. These factors can contribute to a lower cost of capital and therefore a lower WACC, which in turn can have a positive impact on the company’s valuation and profitability (Useche et al., 2024; R. Zhang et al., 2021). Thus, the following hypothesis is put forward:

H1. Higher quality sustainability practices imply a lower weighted average cost of capital in the context of Latin American emerging market companies.

2.3.2. Insolvency Risk (AZS)

The implementation of ESG practices can have a significant positive impact on business performance by improving risk compensation (Shad et al., 2019). According to Moraga (2019), since financial performance is associated with different ratios or indicators that allow validating the quality of corporate management, it can be established whether the adoption of ESG practices can keep the organisation away from bankruptcy. In this way, it is pertinent to establish whether this adoption affects variables of the financial solvency of companies estimated through the Z-score model of Altman (1968) and Altman et al. (2014). Therefore, the following hypothesis is established:

H2. Higher quality sustainability practices are associated with lower levels of insolvency probability (bankruptcy risk) in the context of Latin American emerging market companies.

3. Methodology

From a corporate financial management perspective and focused on sustainable development, this research addresses the relationship between ESG practices, profitability, valuation and risk for a sample of companies listed on Latin American financial markets and comprising regional stock market indices. This study adopts a quantitative and longitudinal approach, which allows a rigorous analysis of the evolution of the variables under study and the financial performance of the firms.

3.1. Sample and Data

The sample is composed of companies from various sectors listed on the São Paulo Stock Exchange (B3) that are included in the Bovespa Stock Index, which represents a portfolio of the most representative and liquid stocks in the Brazilian market. In total, approximately 86 firms are considered within an unbalanced panel, given that the composition of the index varies over the years(Meneses Cerón et al., 2021).

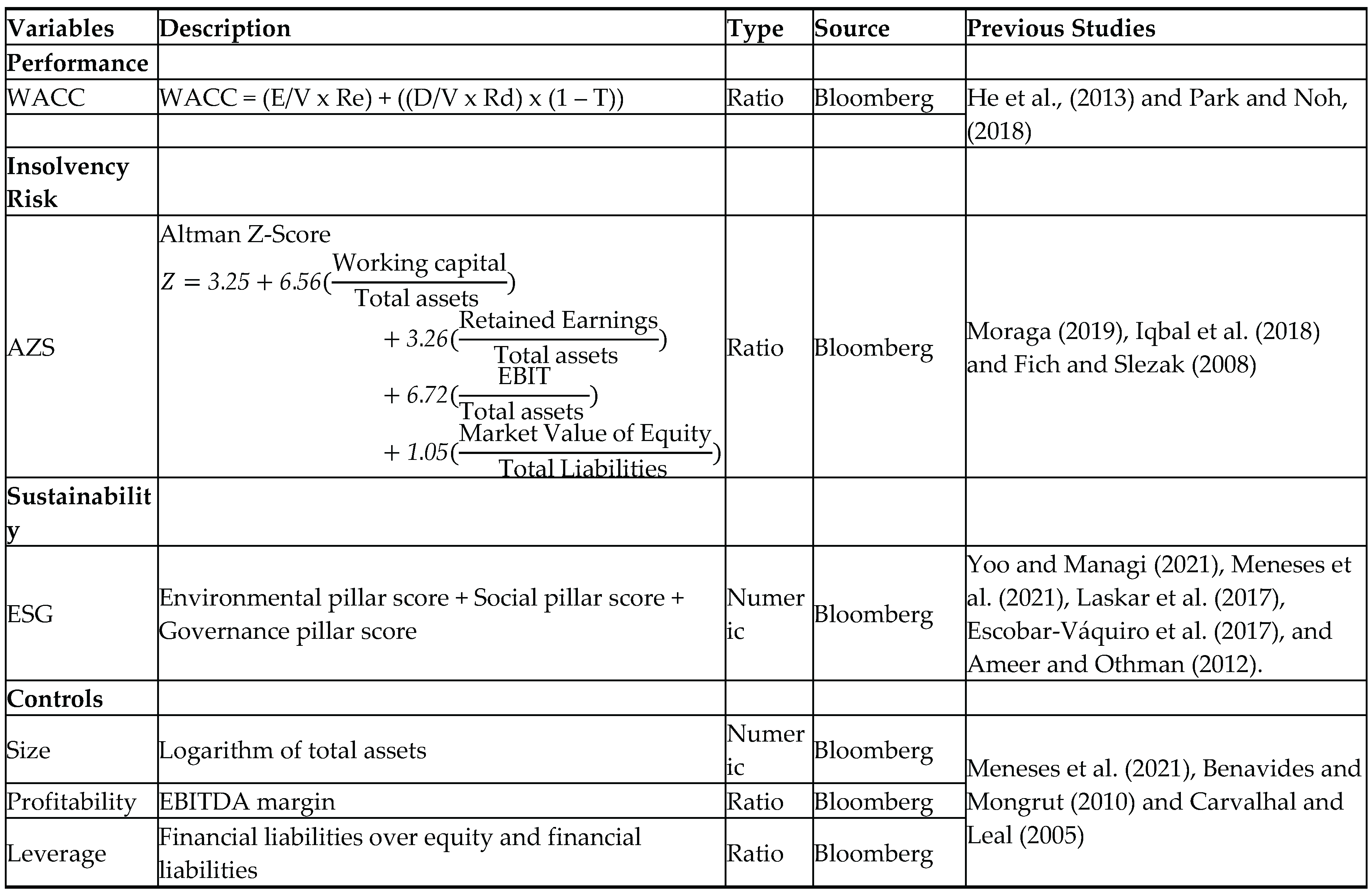

Annual ESG rating and financial data of Brazilian companies from 2010 to 2021 (as of December 31st) were downloaded from the Bloomberg financial platform (see

Table 1). To measure the quality of sustainable practices, the Bloomberg ESG Score was used. This index evaluates a variety of qualitative and quantitative ratios related to the company's accountability, institutional transparency and social responsibility. The data required to determine the ESG rating is collected from multiple sources, including corporate social responsibility reports, annual reports and the company's website, which offers an objective view of the company's environmental, social and governance performance (B. M. Huber et al., 2017).

3.2. Description of Variables and Controls

3.3. Dependent Variables

According to Durst et al. (2019), the evaluation and measurement of organisational performance are crucial for the survival and success of organisations, so all entities are expected to review the actions carried out by their managers or directors. The independent variables capture the two main dimensions of financial stability (See

Table 1). In line with Moraga (2019), Iqbal et al. (2018) and Fich and Slezak (2008), the WACC and a risk measure, specifically the Z score (AZS), were included. The WACC indicates how much it costs the company to obtain funds and is used as the discount rate in the valuation of projects and cash flows(Meneses Cerón et al., 2024). The AZS ratio estimates the probability of a firm's bankruptcy or insolvency(Nian et al., 2025). The selection of these independent variables is based on the premise that the implementation of ESG can positively influence the financial stability and solvency of companies in emerging Latin American markets(Mirza et al., 2025).

3.4. Independent Variables

The study used as an independent variable, the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) rating, understood as a combined ESG rating, provided by the Bloomberg database, which evaluates companies based on the sustainability information they publicly disclose. Bloomberg's ESG score methodology integrates quantitative and qualitative data to build a standardized and comparable measure across firms and sectors, allowing firms' commitment to environmental stewardship, responsible social practices, and the strength of their governance structures to be assessed(Meneses Cerón et al., 2021).

3.5. Controls

Three types of control variables were used in the research (see

Table 1). First, a size control was used, measured through the natural logarithm of the firm's total assets. This variable is widely used in the financial literature to reduce heterogeneity and control scale between companies(Bilivogui & Iqbal, 2025). Second, a profitability control was incorporated, expressed through the EBITDA margin, calculated as the ratio between EBITDA and operating income. This indicator captures the firm's ability to generate cash flow from its core operations. Its inclusion as a control variable is essential, since a higher EBITDA margin can improve financial resilience and facilitate the implementation of ESG practices, while companies with low profitability may face resource constraints that limit such initiatives(Itan et al., 2025). Third, a financial leverage control was used, defined as the ratio between financial liabilities and total financial liabilities plus equity, which allows the company's capital structure to be accurately captured. This indicator is critical because high levels of indebtedness increase the risk of insolvency and agency costs associated with creditor pressure. At the same time, the literature shows that integrating ESG practices can mitigate these risks by strengthening transparency and trust with lenders(Nian et al., 2025).

3.6. Econometric Modelling

In this research, three econometric tools are employed to model the relationship between ESG score, firms’ cost of capital, and insolvency risk. The first two tools, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model on panel data, are used to analyse the short-term relationships, providing insight into how changes in ESG practices affect the cost of capital and insolvency risk over more immediate time periods (Benavides-Franco et al., 2023). The third tool, Fully Modified Least Squares (FMOLS) on panel data, is used to infer the long-term relationship, allowing to assess the sustained and structural effects of ESG practices on the cost of capital and insolvency risk over extended time periods. This multi-method approach provides a comprehensive analysis of both the immediate temporal dynamics and the long-lasting impacts.

3.6.1. OLS with Fixed Effects

As an exploratory analysis, we start from a linear model with fixed effects estimated using OLS. In these models, the independent variables are lagged by one year, to take into account that the effect of the ESG rating may take a period to materialize in terms of corporate performance (see equations 1 and 2).

where represents the cost of financing for firm i in period t, represents ESG one year earlier, is a vector of controls, are firm fixed effects, are the disturbance terms and are the parameters to be estimated. The parameters of interest are

, that is, the expected change, one year later, in WACC and AZS indices in response to an increase in ESG. In other words, the short-term effect of sustainability practices on firms’ cost of financing and the probability of insolvency

.

3.6.2. VAR Model on Panel Data

The Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model is a statistical technique used to capture the dynamic interrelationships between multiple time series. In the context of panel data, this approach is adapted to integrate time series with cross-sectional data, thereby combining observations over time for multiple units or entities(Doh & Smith, 2022). VAR for panel data extends the traditional VAR model commonly applied to univariate or multivariate time series, by incorporating multiple entities within a panel framework, allowing for the simultaneous analysis of interactions between variables across different units and periods (F. Huber & Rossini, 2022).

The VAR model has several advantages compared to a single-equation model. According to Li et al. (2023), the VAR model allows multiple endogenous variables to be modelled simultaneously instead of treating each variable separately as in a single-equation model. This means that feedback relationships and interactions between variables can be captured more realistically. Accordingly, all variables are considered endogenous, meaning that all variables can affect each other. This is especially useful when the variables of interest are interconnected and affect each other. This is fundamentally important for the study, given the possibility that ESG practices influence both the cost of capital and the risk of insolvency, and at the same time, that these financial factors affect ESG performance.

Furthermore, PVAR is a dynamic model that takes into account relationships over time. It can capture changes and adjustments in variables as they evolve over time, making it suitable for time series data(Owjimehr & Meybodi, 2025). Specifically, PVAR allows for impulse-response analysis, which shows how a variable responds to changes in other variables in the system (Sassen et al., 2016). This will allow for assessing the significance and duration over time of ESG on the cost of capital and insolvency risk. This is relevant, as the effects may persist over several periods. Here we consider a homogeneous VAR panel of 3 endogenous variables (cost of capital, insolvency risk and ESG) of order with firm and period fixed effects, represented by the following system (see equation 3):

where

is a vector of size 3, having as input the variables of interest.

are the respective lags of the vector

,

is a vector of exogenous variables,

and

are firm and time fixed effects, respectively, and

is the vector of idiosyncratic disturbances. The parameters

and

are 3 x 3 y

, matrices which contain the parameters to be estimated. The VAR model is homogeneous in the sense that the parameters to be estimated are common to all firms in the country. That is, the time series that make up the panel come from the same data generating process. Additionally, it is assumed that

That is, the disturbance term has zero mean, a variance-covariance matrix and is not autocorrelated.

For a fixed number of periods and N tending to infinity, the presence of lag variables and fixed effects on the right-hand side of the equation causes OLS applied to each equation separately to be a biased estimator. For this reason, the generalised method of moments (GMM) is used to estimate the model, using the highest order lags a of and .

The GMM estimator is constructed as follows. First, the 3 endogenous variables are differentiated and arranged in a row vector:

From now on,

represent the variables in first differences. This transformation is performed to remove the firm fixed effect from the model. Similarly, arranging the explanatory variables in a row vector:

where

In this way, the model can be re-expressed as

where

The last component for the estimation is the instrument matrix Z

it, which must have at least as many columns as

L=kp+l. That is, as many instruments as endogenous variables times the number of their lags, plus the number of exogenous variables. It should be noted that the exogenous variables are instruments of themselves, that is, X

it∈ Z

it:

Now, stacking these row vectors for each firm and then for each period

The GMM estimator is given by:

Based on the estimated parameters, the impulse-response matrix

, for each moment, is obtained as:

Based on the magnitude and significance of the parameters , we will be able to evaluate the size and direction of the ESG effect on the risk of insolvency and the cost of capital, and additionally, evaluate the duration of these effects over time.

3.6.3. Fully Modified Least Squares on Panel Data

This method is based on linear relationships between variables:

Note that the independent variables are not lagged, since we are interested in the long-run relationship between the variables (see equations 7 and 8). For this, we use the fully modified least squares method for panel data. FMOLS for panel data is an estimation technique used in econometrics to address problems of endogeneity and serial correlation in panel data models(Fatima et al., 2024). This method is an extension of the OLS approach and is specifically designed to handle cross-sectional or panel time series data.

The main objective of FMOLS is to correct for regression bias that may arise due to endogeneity of the explanatory variables or the presence of serial correlation in the errors. This is achieved by transforming the variables in the model to remove serial correlation in the errors, thereby allowing for more efficient and consistent coefficient estimates. FMOLS estimates long-run effects because it is specifically designed to address the presence of unit roots in time series, which implies that variables have persistent trends over time. When variables in a model have unit roots, they may exhibit a cointegrating relationship, meaning that they are linked in the long run. To estimate by FMOLS we use the STATA xtcointreg function (Khodzhimatov, 2018).

4. Results

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the research variables, providing an overview of the financial and sustainability profiles of the companies analyzed.

The weighted average cost of capital (WACC) exhibits substantial variability, ranging from approximately 2.75% to 29.36%, with a mean of 13.75% and a standard deviation of 3.40%. This dispersion reflects heterogeneity in capital structures and financing costs, highlighting how firms adopt different approaches to balance equity and debt in pursuit of sustainable growth.

The sustainability practices index spans from 3.60 to 74.44, with a mean of 42.14 and a standard deviation of 13.48. This indicates a significant variation in the adoption and implementation of ESG-related practices, suggesting that while some firms are highly committed to sustainability, others are in early stages of integrating these practices into their operations.

Regarding firm size, measured by the logarithm of total assets, values range from 4.49 to 13.24, with a mean of 8.94 and a standard deviation of 1.67. This spread indicates that the sample encompasses firms of varying scales, from small- and medium-sized enterprises to large corporations, each potentially facing different challenges and opportunities in implementing sustainable financial strategies.

The ratio of total liabilities to total assets varies widely, from 0.38 to 246.18, with a mean of 61.25 and a standard deviation of 23.31. Such variability reflects diverse financial leverage strategies across firms, emphasizing the importance of assessing risk and capital allocation when integrating sustainability into corporate finance decisions.

Finally, The EBITDA margin exhibits considerable variability across the sample of firms. With 986 observations, the margin has a mean of 26.53% and a standard deviation of 21.71%, indicating a wide dispersion around the average profitability level. The minimum value of -68.99% signals that some firms are operating at substantial losses relative to their sales, while the maximum of 102.54% reflects exceptionally high operating efficiency in certain cases. This heterogeneity highlights the diverse operational performance across firms and suggests that different management practices, including sustainability initiatives, may significantly influence earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization relative to revenue.

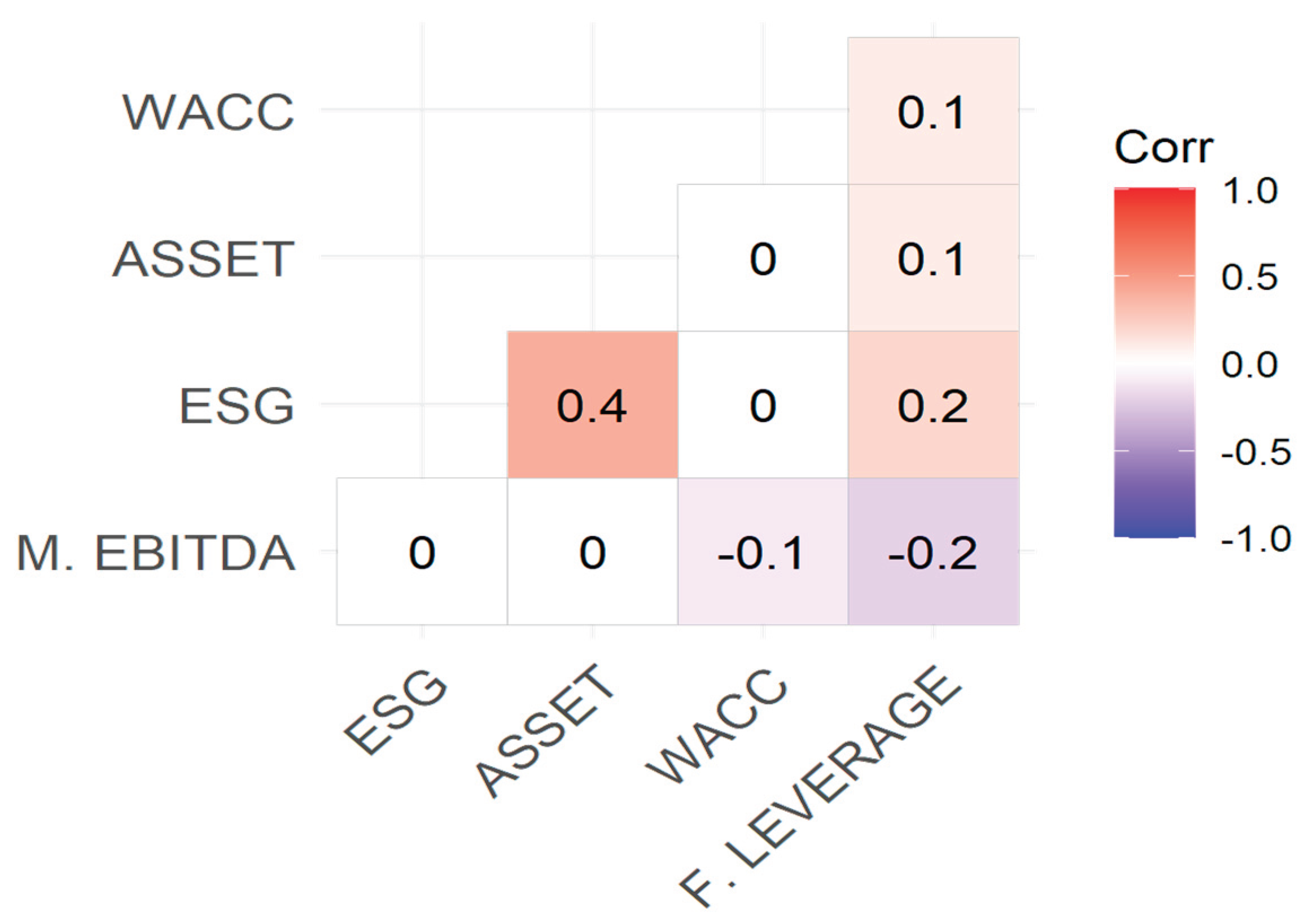

Figure 1 presents the correlations between the variables analysed. The correlation matrix reveals the relationships between the financial and sustainability variables of the company under study. The correlation between WACC and ESG is almost insignificant. This indicates that there is no clear connection between the cost of capital and the level of sustainability of these companies. It seems that investors are not financially penalizing or rewarding companies for their sustainable practices.

Extending our analysis to other financial variables, such as asset size and capital structure, we observe equally weak relationships with financial cost. The correlation between WACC and asset size is small, suggesting that a firm's size does not significantly affect its cost of capital. Similarly, the relationship between WACC and capital structure, represented by the ratio of total liabilities to total assets, is weak, with a correlation approximately equal to 0.1. This indicates that capital structure decisions are not having a significant impact on the financing cost of the firms in this sample.

It is notable that when examining the relationship between WACC and EBITDA margins, we observe a weak negative correlation. This suggests that, while not a strong relationship, there appears to be a slight tendency towards lower cost of capital in companies with higher EBITDA margins. However, this relationship is very tenuous and cannot be considered a driving factor. However, these correlations only reflect the strength of the relationship for a pair of variables. Although no strong correlation is found between WACC and the explanatory variables, the results change when the multivariate analysis presented in the results section is performed.

Table 3 presents the relationship between WACC and ESG, controlling for assets, financial leverage, and EBITDA margin. In these regressions, ESG and controls are lagged one year. This is to capture the expected change in WACC, one year later, in the event of a change in ESG and controls. In other words, the study seeks to capture the effects of the explanatory variables in the short term.

When firm fixed effects are not controlled for, it is found that, with a 1 percentage point increase in ESG, WACC decreases by 0.02 points (columns 1 and 2). These effects are significant at the 10% and 1% levels, respectively. In contrast, when firm fixed effects are included, the effect is not significant. That is, based on the more complete regression, it is concluded that there is no relationship between ESG and WACC in the short term.

In the short term, an increase in the ESG index does not necessarily lead to a decrease in the cost of financing due to several interrelated factors. First, investors and lenders may not immediately perceive the financial benefits associated with sustainability practices. Although these practices are often linked to more effective long-term risk management, their short-term impact may not be evident, limiting financiers’ willingness to reduce financing costs in response to improvements in the ESG index. Furthermore, implementing sustainability practices often involves significant upfront costs, including investments in infrastructure, technology, and changes to operational processes. These costs can outweigh the financial benefits in the short term, meaning that even if a company improves its ESG index, it will not necessarily experience an immediate decrease in its cost of financing(Tron et al., 2025).

Table 4 presents the relationship between AZS and ESG, controlling for assets, financial leveraged, and EBITDA margin. As before, these regressions capture short-term effects. When not controlled for firm fixed effects, we find that for a 1 percentage point increase in ESG, AZS decreases by approximately 0.03 points (columns 1 and 2) and 0.018 (column 3). These effects are significant at 1% and 5%, respectively. That is, based on all regressions, we conclude that there is a negative relationship between ESG and AZS in the short term.

In the short term, an increase in the ESG score could increase the likelihood of insolvency for a company for several interrelated reasons. First, implementing sustainability practices often requires significant investments in technology, infrastructure, and process change. These upfront costs can put pressure on a company’s liquidity in the short term, especially if they do not immediately translate into tangible financial benefits. Added to this, adopting sustainability practices could reduce available liquidity in the short term. For example, investing in cleaner technologies or improving labour standards could affect the immediate availability of cash, making it difficult to meet short-term financial obligations(DasGupta, 2022).

Sustainability practices could also negatively impact profitability in the short term. For example, transitioning to cleaner energy sources could increase production costs initially, while implementing stricter labour standards could increase labour costs. These cost increases without a corresponding increase in revenue could negatively impact profitability and the company’s ability to meet its financial obligations(Chau et al., 2025).

The robustness of these results is corroborated by using a VAR model for panel data.

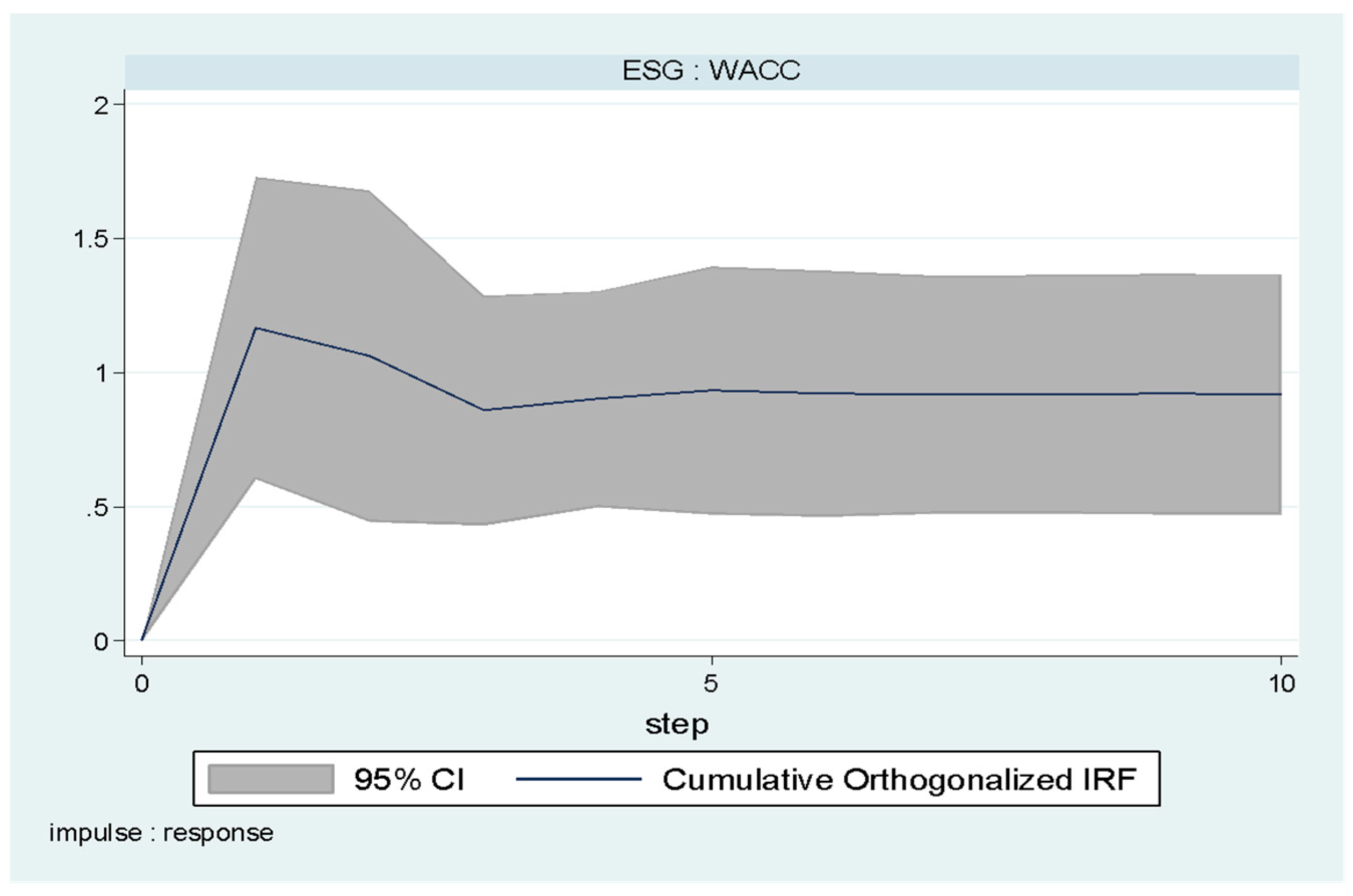

Figure 2 shows how WACC reacts to an unforeseen 1% shock to the ESG, holding the controls constant. The cumulative impulse response reveals that after one year, there is an increase in WACC, which remains stable. That is, increasing the ESG has the cost of an increase in WACC one year later, but from year two onwards, WACC no longer increases.

As mentioned above, in the short term, an increase in the ESG score may result in an increase in the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) because this increase often entails significant upfront costs. For example, investments in cleaner technologies or improvements in labour standards may require significant cash outlays in the short term, which increases operating and financial costs, thereby raising WACC.

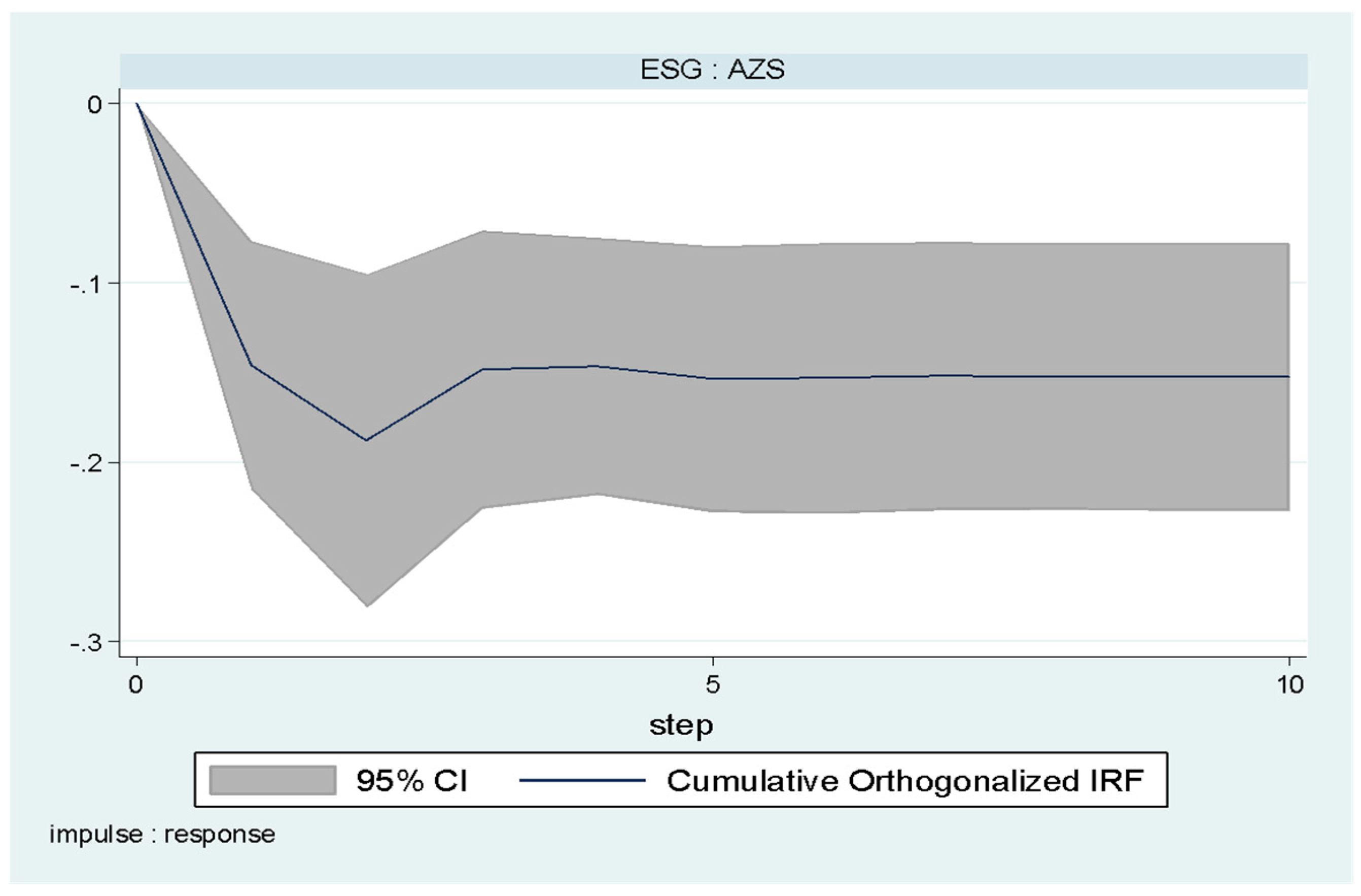

Figure 3 shows how AZS reacts to an unforeseen 1% shock to ESG, holding controls constant. The cumulative impulse response function reveals that after one year, there is an increase in AZS, which then decreases again in year 2. That is, increasing ESG comes at the cost of a decrease in AZS one and two years later, but from year three onwards, AZS no longer decreases.

Finally, the long-term results are presented, based on the inference of the cointegration relationship between WACC/AZS with ESG and the controls.

Table 5 presents the results. It is found that, in the long term, an increase in the ESG decreases WACC by 0.01 points, and increases the AZS by 0.01 points. That is, although in the short term the ESG can increase the cost of financing and the risk of bankruptcy, in the long term these effects are reversed.

The contrast between the short- and long-term effects of increasing the ESG score on the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) and the probability of insolvency can be understood by considering different time horizons and underlying factors. In the short term, implementing sustainability practices entails significant upfront costs, which may temporarily increase WACC. Investments in cleaner technologies or improvements in labour standards may put pressure on the company’s operating and financial costs, negatively impacting its ability to meet its financial obligations.

In the long term, however, these practices can lead to substantial improvements in operational efficiency, risk reduction and value creation. Investments in sustainability can translate into significant savings in energy costs, environmental compliance and improvements in labour productivity. This improvement in operational efficiency can reduce WACC, as investors perceive lower risks associated with the company. In addition, a strong sustainability strategy can improve the company's reputation and strengthen its relationship with investors and lenders. As the company demonstrates a long-term sustainable commitment and achieves positive results, investors may be more willing to accept a lower return, which further lowers WACC and facilitates access to capital on more favourable terms(Ramirez et al., 2022).

Regarding the probability of insolvency, sustainability practices show strong potential to enhance firms’ long-term operational and financial stability by promoting more efficient risk management, optimal resource allocation, and greater resilience to adverse economic environments. Adopting sound environmental policies can reduce exposure to regulatory fines and litigation, while fair labor practices can increase employee retention and productivity. These factors can strengthen a company’s competitive position and reduce its vulnerability to economic shocks, decreasing the likelihood of insolvency(Nian et al., 2025).

Therefore, although the adoption of sustainability practices may generate short-term financial challenges, the long-term benefits —in terms of operational efficiency, corporate reputation, and financial stability— can translate into a reduction in WACC and a lower probability of insolvency. In this regard, the present research provides empirical evidence that, in emerging business contexts, the implementation of ESG practices entails a financial learning curve or a short-term versus long-term trade-off, in which the initial higher costs are offset by a progressive strengthening of financial stability, corporate reputation, and the firm’s adaptive capacity to environmental and social risks over the long term.

5. Robustness Tests

Because the results are based on panel data models, it is important to perform robustness tests to ensure that the results are reliable, interpretable, and consistent. To this end, three tests are undertaken: model stability test, non-autocorrelation test in the residuals, and overidentification test(Bramati & Croux, 2007).

5.1. Model Stability Test

The stability test in an econometric model, such as a PVAR, assesses whether the model is stable and produces reliable results. In the context of a VAR or PVAR, stability ensures that disturbances in variables do not generate explosive effects, but rather dissipate over time, allowing simulations (such as impulse response functions) and predictions to be valid.

A VAR model is stable if all the roots of the associated characteristic polynomial are inside the unit circle in the complex plane. The roots of the estimated PVAR are presented in

Table 6. As can be seen, the pattern of each of the roots is less than 1, that is, the roots are inside the unit circle. This implies that the estimated PVAR is stable.

5.2. Overidentification Test

The overidentification test (also known as the Sargan test or Hansen test in heteroscedasticity-robust contexts) is a tool to assess the validity of instruments in econometric models that employ instrumental variables, such as the PVAR. A model is overdetermined (overidentified) if there are more instruments than equations or endogenous variables. In this case, the consistency between instruments can be assessed. The null hypothesis of the Hansen test is that the instruments are not correlated with the error term, that is, they are valid. The alternative hypothesis is that at least one of the instruments is correlated with the error term. The test results are presented in

Table 7. At 1% significance, it is concluded that the null hypothesis is not rejected. That is, there is evidence that the instruments used to estimate the PVAR are valid.

5.3. Autocorrelation Test

The optimal choice of lags in a PVAR model is crucial because an incorrect number of lags can lead to autocorrelated residuals, which compromises the validity of the model. Since the results presented above are based on a PVAR of order 1, it is necessary to verify whether this is the optimal number of lags. To verify this, the information criteria AIC, BIC and HQIC are used. The optimal number of lags is the one that minimises any of these criteria. As can be seen in

Table 8, the lag number that minimises the mentioned criteria is 1, so this guarantees that the residuals of the model are well behaved, that is, they are not autocorrelated.

Since these robustness tests yield good results, it can be concluded that the model is correctly specified. The model is robust and reliable, the diagnostic tests showed no problems, which supports the validity of the inferences made. In addition, the model adequately captures the dynamic relationships: the optimal selection of lags and the absence of autocorrelation in the residuals ensure that the model explains the temporal patterns correctly.

6. Discussion

This study makes a significant contribution to the financial literature by integrating sustainability into the analysis of corporate performance among publicly traded firms in emerging economies. Specifically, in the case of the Brazilian market, evidence indicates that the relationship between ESG performance and key financial variables —the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) and insolvency risk (AZS)— exhibits a complex nature that depends on the temporal horizon of analysis. This dynamic reflects the existence of a financial learning curve or ESG trade-off between the short and long term, in which the higher initial costs associated with the implementation of sustainable strategies —such as investments in clean technologies, improvements in governance, or social programs— are gradually offset by a sustained strengthening of financial stability, an enhanced corporate reputation, and a greater capacity for resilience to environmental, social, and regulatory risks.

In the short term no significant relationship exists between the ESG practices rating and the WACC. This suggests that implementing ESG strategies does not generate an immediate decrease in financing costs due to factors such as high initial investment requirements, lack of knowledge about the cost-benefit ratio of the transition and limited recognition of short-term risks by investors and lenders, among other aspects (Burcă et al., 2024). In the long term, however, the relationship between ESG performance and WACC changes significantly. Indeed, an increase in the ESG score is consistently associated with a reduction in the WACC, which demonstrates the tangible benefits of sustainability in financial terms to generating a more attractive environment for investors and lenders, increase stakeholder confidence and contribute to greater financial stability and lower exposure to regulatory risks (Darsono et al., 2025). These findings are supported by previous literature focused on emerging markets. In this regard, Priem and Gabelone (2024) observed that companies with higher ESG scores tend to benefit from lower capital costs, especially in countries with less robust legal environments, where the long-term benefits are more clearly evident. Likewise, Tawfiq et al. (2024) showed that strong ESG performance not only increases disclosure levels, but also reduces leverage ratios and lowers the WACC, thanks to more favourable financing conditions and a more favourable risk perception by the market. On the other hand, Pirgaip and Rizvic (2023) established that the adoption of integrated reporting is positively related to WACC and cost of debt, although its impact on cost of equity is not significant.

Regarding financial risk, the study found that in the short term, an increase in the ESG index is associated with an increase in the probability of insolvency due to initial implementation costs, including investments in cleaner technologies and improved labour standards. These expenses put pressure on liquidity, increasing operating and financial costs. However, the analysis also reveals that, in the long term, ESG practices significantly improve operational efficiency and reduce the risk of insolvency. This is evidenced by better AZS levels, suggesting greater financial stability. This finding coincides with Gartia (2024), who also identified a positive relationship in the case of Brazil, where companies with high ESG performance manage risks better and take advantage of associated financial opportunities, allowing them to have superior corporate performance. Our findings align with Gholami et al (2023), who found that the mitigating impact of corporate ESG performance disclosure scores on the company's idiosyncratic risk is due to improved access to cheaper sources of financing. We also affirm the findings of Giese et al. (2021), who argued that the transmission of ESG characteristics to financial performance is a multi-channel process, since it affects the valuation and performance of companies, both through their systematic risk profile (lower capital costs and higher valuations) and their idiosyncratic risk profile (higher profitability and lower exposure to extreme risks).

Consequently, sustainability extends beyond a mere ethical or reputational commitment, emerging as a strategic driver of long-term corporate value. Its effective implementation can reduce the cost of capital, enhance operational efficiency, and mitigate financial risk, particularly in highly uncertain and volatile environments. From the perspective of signaling theory (Spence, 1973), stakeholder theory (Freeman, 2010) and the financial trade-off theory (Myers, 1977), sustainable practices provide tangible financial benefits by improving investor perception, lowering capital costs, and fostering long-term value creation. Moreover, sustainability strengthens corporate competitiveness, attracts responsible investors and consumers, and reinforces the organization’s legitimacy and market confidence.

7. Conclusions

This study makes important contributions to the sustainable finance literature by addressing several crucial gaps in current research. First, it extends the analysis on the implementation of ESG practices and their impact on financial stability to the level of Latin American emerging markets, a context generally underexplored in contemporary corporate finance. Second, it incorporates novel financial variables such as the WACC or the Altman ZScore. Third, the study proposes an interesting comparative analysis by comparing the effects of ESG implementation in the short and long term, which affords a better assessment of the cost-benefit ratio of their incorporation by emerging market firms. Lastly, the research makes a methodological innovation by using two uncommon econometric models in the study of the relationship between ESG implementation and financial performance: the Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model on panel data and the Fully Modified Least Squares (FMOLS) on panel data.

The findings from this study offer critical insights into the financial implications of integrating ESG practices into corporate strategies in emerging markets. The analysis reveals that, in the short term, ESG adoption triggers an increase in the WACC and the risk of insolvency, largely due to the high initial costs, such as investments in technology and operational improvements that put pressure on financial costs, reduce liquidity and increase indebtedness during the first year. However, in the long term, these costs are reversed. This is a particularly salient finding for firms operating in more volatile economic environments like Brazil.

From a practical perspective, the findings offer actionable recommendations for policymakers, investors, and corporate leaders. Policymakers should focus on designing a robust regulatory framework that incentivizes ESG adoption, for instance, through tax incentives, preferential loans, green bonds, and public-private financing programs that reduce the initial implementation costs. Likewise, investors can use ESG ratings as a proxy for long-term stability and resilience, guiding investment decisions toward companies committed to sustainability. Shifting management focus from short-term profitability to long-term value creation allows organizations to align around common ESG objectives. Corporate leaders, in turn, should prioritize transparency, strategic alignment, and active stakeholder engagement, effectively communicating the financial and operational impacts of ESG initiatives to build trust and reduce perceived barriers. Collaboration between the public and private sectors, through incentives, technical support, and co-financing mechanisms, can minimize upfront costs, accelerating the transition toward sustainable business models without compromising financial stability.

The research has some limitations. First, the reliance on annual data provided by Bloomberg may introduce discrepancies due to differences in calculation methodologies compared to other financial information platforms. Data from other Latin American markets was not included. Only companies from the Brazilian market were selected due to their consistency in terms of sustainability data within the observation window. In addition, the sample is restricted to listed companies that are part of regional stock market indices, which may not adequately reflect other contexts and sectors. For future studies, it would be beneficial to integrate higher frequency data, expand the research to various regions and sectors, explore alternative ESG measurement tools, and analyse the impact of non-financial factors and economic or political shocks, in order to obtain a more comprehensive and accurate view of the relationship between ESG practices, profitability, and risk in emerging markets.

References

- Al Azizah, U. S.; Haron, R. The sustainability imperative: Evaluating the effect of ESG on corporate financial performance before and after the pandemic. Discover Sustainability 2025, 6(1), 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E. I. FINANCIAL RATIOS, DISCRIMINANT ANALYSIS AND THE PREDICTION OF CORPORATE BANKRUPTCY. In The Journal of Finance; Scopus, 1968; Volume 23, 4, pp. 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E. I.; Iwanicz-Drozdowska, M.; Laitinen, E. K.; Suvas, A. Distressed Firm and Bankruptcy Prediction in an International Context: A Review and Empirical Analysis of Altman’s Z-Score Model; Social Science Research Network; SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 2536340; 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S. M.; Masud, Md. A. K.; Kim, J. D. A Cross-Country Investigation of Corporate Governance and Corporate Sustainability Disclosure: A Signaling Theory Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10(8), 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management 1991, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides-Franco, J.; Carabalí-Mosquera, J.; Alonso, J. C.; Taype-Huaman, I.; Buenaventura, G.; Meneses, L. A. The evolution of loan volume and non-performing loans under COVID-19 innovations: The Colombian case. Heliyon 2023, 9(4), e15420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.; Rigobón, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bilivogui, P.; Iqbal, M. A. Do ESG scores matter? An empirical analysis of corporate financial performance in BRICS economies. Environmental Research Communications 2025a, 7(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilivogui, P.; Iqbal, M. A. Do ESG scores matter? An empirical analysis of corporate financial performance in BRICS economies. Environmental Research Communications 2025b, 7(6), 065023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, B.; Lim, R.; Lyons, B. M. Estimating the Cost of Equity in Emerging Markets: A Case Study. 2017. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Estimating-the-Cost-of-Equity-in-Emerging-Markets%3A-Boyer-Lim/4dfcc0961bbfac8a3ae89eb6bd62a13a5c373f13.

- Bramati, M. C.; Croux, C. Robust estimators for the fixed effects panel data model. The Econometrics Journal 2007, 10(3), 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcă, V.; Bogdan, O.; Bunget, O.-C.; Dumitrescu, A.-C.; Imbrescu, C. M. Financial Implications of Supply Chains Transition to ESG Models. Contemporary Studies in Economic and Financial Analysis 2024, 116, 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalhal, A.; Leal, R. Corporate Governance Index, Firm Valuation na Performance in Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Finanças 2005, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, L.; Anh, L.; Duc, V. Valuing ESG: How financial markets respond to corporate sustainability. International Business Review 2025, 34(3), 102418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkasova, V.; Nenuzhenko, I. Investment in ESG Projects and Corporate Performance of Multinational Companies. Journal of Economic Integration 2022, 37(1), 54–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, Y. The role of ESG in corporate financial performance and competitiveness. In En Reference Module in Social Sciences; Elsevier, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darsono, D.; Dwi; ratmono; Abas; tujori; Tiara, Y. The relationship between ESG, financial performance, and cost of debt: The role of independent assurance. Cogent Business & Management 2025, 12(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DasGupta, R. Financial performance shortfall, ESG controversies, and ESG performance: Evidence from firms around the world. Finance Research Letters 2022, 46, 102487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, T.; Smith, A. L. A new approach to integrating expectations into VAR models. Journal of Monetary Economics 2022, 132, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, J.; Sharma, A. K. Corporate Sustainability and Capital Costs: A Panel Evidence from BRICS Countries. Indian Journal of Corporate Governance 2024, 17(1), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Hinteregger, C.; Zieba, M. The linkage between knowledge risk management and organizational performance. Journal of Business Research 2019, 105, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R. F.; Giglio, S.; Kelly, B.; Lee, H.; Stroebel, J. Hedging Climate Change News. The Review of Financial Studies 2020, 33(3), 1184–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, S.; Mohammadin, Z.; Azarbayjani, K. Corporate finance signaling theory: An empirical analysis on the relationship between information asymmetry and the cost of equity capital. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 2025, 22(3), 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, N.; Xuhua, H.; Alnafisah, H.; Akhtar, M. R. Synergy for climate actions in G7 countries: Unraveling the role of environmental policy stringency between technological innovation and CO2 emission interplay with DOLS, FMOLS and MMQR approaches. Energy Reports 2024, 12, 1344–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A. Corporate bankruptcy filings rise despite strong GDP growth. valorinternational. 2024. Available online: https://valorinternational.globo.com/business/news/2024/12/19/corporate-bankruptcy-filings-rise-despite-strong-gdp-growth.ghtml.

- Fich, E. M.; Slezak, S. L. Can corporate governance save distressed firms from bankruptcy? An empirical analysis. In Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting; Scopus, 2008; Volume 30, 2, pp. 225–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gartia, U.; Bhue, R.; Panda, A. K. Unlocking the dynamic linkages between sustainable equity investment and economic policy uncertainty: An empirical analysis for G-20 countries. Business Strategy & Development 2024, 7(2), e359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, A.; Sands, J.; Shams, S. Corporates’ sustainability disclosures impact on cost of capital and idiosyncratic risk. In Meditari Accountancy Research; Scopus, 2023; Volume 31, 4, pp. 861–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, G.; Nagy, Z.; Lee, L.-E. Deconstructing ESG ratings performance: Risk and return for E, S, and G by time horizon, sector, and weighting. The Journal of Portfolio Management : JPM 2021, 47(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A. M. Do business strategies and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance mitigate the likelihood of financial distress? A multiple mediation model. Heliyon 2023, 9(7), e17847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M. K.; Chiaramonte, L.; Dreassi, A.; Paltrinieri, A.; Piserà, S. Equity costs and risks in emerging markets: Are ESG and Sharia principles complementary? Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 2023, 77, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawn, O.; Ioannou, I. Mind the gap: The interplay between external and internal actions in the case of corporate social responsibility. Strategic Management Journal 2016, 37(13), 2569–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, B. M.; Comstock, M.; Polk, D. ESG Reports and Ratings: What They Are, Why They Matter. The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. 2017. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2017/07/27/esg-reports-and-ratings-what-they-are-why-they-matter/.

- Huber, F.; Rossini, L. Inference in Bayesian additive vector autoregressive tree models. The Annals of Applied Statistics 2022, 16(1), 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Nawaz, A.; Ehsan, S. Financial Performance and Corporate Governance in Microfinance: Evidence from Asia. Journal of Asian Economics 2018, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itan, I.; Sylvia, S.; Septiany, S.; Chen, R. The influence of environmental, social, and governance disclosure on market reaction: Evidence from emerging markets. Discover Sustainability 2025, 6(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodzhimatov, R. XTCOINTREG: Stata module for panel data generalization of cointegration regression using fully modified ordinary least squares, dynamic ordinary least squares, and canonical correlation regression methods. Statistical Software Components. 2018. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org//c/boc/bocode/s458447.html.

- Krishna, M.; Jain, M.; Manu, K. Impact of ESG Practices on the Firm’s Performance: A Longitudinal Study on Emerging Markets. 2024 International Conference on Trends in Quantum Computing and Emerging Business Technologies; 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavin, J. F.; Montecinos-Pearce, A. A. Heterogeneous Firms and Benefits of ESG Disclosure: Cost of Debt Financing in an Emerging Market. Sustainability 2022, 14(23), Article 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Umair, M. The protective nature of gold during times of oil price volatility: An analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Extractive Industries and Society 2023, 15, 101284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioui, A. Is ESG Risk Priced? (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3285091). 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, H. C. Competition and ESG practices in emerging markets: Evidence from a difference-in-differences model. Finance Research Letters 2022, 46, 102371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses Cerón, L. Á.; Carabali Mosquera, J. A.; Pérez Pacheco, C. A.; Caracas Nuñez, A. F. Sostenibilidad y su incidencia en el desempeño financiero corporativo: Evidencia empírica en el mercado bursátil colombiano. Económicas CUC 2021, 42(2), 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses Cerón, L. Á.; van Klyton, A.; Rojas, A.; Muñoz, J. Climate Risk and Its Impact on the Cost of Capital—A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16(23), Article 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, L.; Orozco Álvarez, J. E.; Muñoz Zúñiga, D. F.; Pareja, A. Las prácticas ESG y su efecto en el desempeño financiero corporativo: Análisis empírico en el mercado de valores brasileño. Dictamen Libre 2022, 31, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, N.; Umar, M.; Lobont, O.-R.; Safi, A. ESG lending, technology investment and banking performance in BRICS: Navigating sustainability and financial stability. China Finance Review International 2025, 15(2), 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga, H. Gobierno corporativo y riesgo de quiebra en las empresas chilenas, 2019.

- Moreira, C. S.; de Araújo, J. G. R.; da Silva, G. R.; Lucena, W. G. L. Environmental, social and governance and the firm life cycle: Evidence from the Brazilian market. Revista Contabilidade & Finanças 2023, 34, e1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S. C. Determinants of corporate borrowing. Journal of Financial Economics 1977, 5(2), 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, H.; Said, F. F.; Mohd Azam, A. H.; Mohd Ariff, N. Does ESG implementation reduce bankruptcy risk of manufacturing and non-manufacturing firms? Evidence from dynamic panel threshold model. Finance Research Letters 2025a, 85, 108101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, H.; Said, F. F.; Mohd Azam, A. H.; Mohd Ariff, N. Does ESG implementation reduce bankruptcy risk of manufacturing and non-manufacturing firms? Evidence from dynamic panel threshold model. Finance Research Letters 2025b, 85, 108101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortas, E.; Moneva, J. M.; Burritt, R.; Tingey-Holyoak, J. Does Sustainability Investment Provide Adaptive Resilience to Ethical Investors? Evidence from Spain. Journal of Business Ethics 2014, 124(2), 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owjimehr, S.; Meybodi, M. E. Dynamic relationship between climate policy uncertainty shocks and financial stress: A GMM-Panel VAR approach. Regional Science Policy & Practice 2025, 17(5), 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirgaip, B.; Rizvić, L. The Impact of Integrated Reporting on the Cost of Capital: Evidence from an Emerging Market. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2023, 16(7), Article 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priem, R.; Gabellone, A. The impact of a firm’s ESG score on its cost of capital: Can a high ESG score serve as a substitute for a weaker legal environment. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 2024, 15(3), 676–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, A. G.; Monsalve, J.; González-Ruiz, J. D.; Almonacid, P.; Peña, A. Relationship between the Cost of Capital and Environmental, Social, and Governance Scores: Evidence from Latin America. Sustainability 2022, 14(9), Article 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberti, A.; Lanzini, C. Adequate regulation of ESG standards in Brazil: A comparative analysis with European regulation ESG Studies Review. ESG Studies Review 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RSM. ESG en América Latina y la necesidad de cambio RSM Latin America. 2023. Available online: https://www.rsm.global/latinamerica/es/insights/esg-en-america-latina-y-la-necesidad-de-cambio.

- Santos, B. R.; Soares Machado, M. A.; Jusan, D.; Caldeira, A. M. Sustainability of Brazilian Companies: A Financial Analysis. Procedia Computer Science 2017, 122, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, R.; Hinze, A.-K.; Hardeck, I. Impact of ESG factors on firm risk in Europe. Journal of Business Economics 2016, 86(8), 867–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebrisky, T. Infraestructura sostenible para la competitividad y el crecimiento inclusivo; IDB Publications, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shad, M. K.; Lai, F.-W.; Fatt, C. L.; Klemeš, J. J.; Bokhari, A. Integrating sustainability reporting into enterprise risk management and its relationship with business performance: A conceptual framework. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 208, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job Market Signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 1973, 87(3), 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Signaling in Retrospect and the Informational Structure of Markets. The American Economic Review 2002, 92(3), 434–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhu, Z. The effect of ESG rating events on corporate green innovation in China: The mediating role of financial constraints and managers’ environmental awareness. Technology in Society 2022, 68, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H. ESG performance, investors’ heterogeneous beliefs, and cost of equity capital in China. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfiq, T. T.; Tawaha, H.; Tahtamouni, A.; Almasria, N. A. The Influence of Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure on Capital Structure: An Investigation of Leverage and WACC. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2024, 17(12), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tron, A.; Franceschi, L. F.; Colantoni, F.; Paolone, F. ESG Dynamics: Assessing the Link Between Sustainability Practices and the Cost of Capital. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2025, 32(4), 5038–5053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunio, R. A.; Jamali, R. H.; Mirani, A. A.; Das, G.; Laghari, M. A.; Xiao, J. The relationship between corporate social responsibility disclosures and financial performance: A mediating role of employee productivity. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28(9), 10661–10677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useche, A. J.; Martínez-Ferrero, J.; Reyes, G. E. Taking ESG strategies for achieving profits: A dynamic panel data analysis. Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science ahead-of-print. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jiao, S.; Ma, C. The impact of ESG responsibility performance on corporate resilience. International Review of Economics & Finance 2024, 93, 1115–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Asongu, S. The Role of ESG Performance in Moderating the Impact of Financial Distress on Company Value: Evidence of Wavelet-Enhanced Quantile Regression With Indian Companies. Business Strategy and the Environment 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Han, Y.; Shao, J.; Dai, J.; Shou, Y. Does ESG rating divergence depress trade credit? A signaling theory perspective; Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 2025; Volume 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. T.; Li, B.; Xie, D. Zhang, Q. T., Li, B., Xie, D., Eds.; Environmental, Social Responsibility, and Corporate Governance (ESG) Factors of Corporations. In Alternative Data and Artificial Intelligence Techniques: Applications in Investment and Risk Management; Springer International Publishing, 2022; pp. 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Green bond issuance and corporate cost of capital. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 2021, 69, 101626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).