1. Introduction

Mountain destinations are increasingly recognized as fragile socio-ecological systems, where tourism development generates both opportunities and vulnerabilities. In such environments, heritage hospitality has emerged as a vital mechanism for linking cultural preservation with sustainable tourism, particularly through the adaptive reuse of traditional architecture [1,2]. Heritage hotels embody cultural narratives, reinforce local identity and contribute to socio-economic resilience [3]. However, despite their growing significance, research on heritage hospitality is fragmented and often lacks a systematic analytical framework [4,5].

In Greece, the development of heritage hotels has been shaped by a combination of public policy, local entrepreneurship, and the socioeconomic characteristics of mountain regions. The Presidential Decrees of 1978 and 1979 established the institutional basis for recognizing “traditional settlements” and development laws provided investment incentive systems to promote the adaptive reuse of vernacular architecture for tourism purposes. Most existing studies emphasise either the legislative framework of traditional settlements [6] or the conservation of architectural heritage [7]. However, few have analyzed how policy instruments, hospitality structures and population dynamics, interact to shape resilience in mountain regions— a gap that has become particularly salient following the Zagori’s inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2023, which has intensified visibility and development pressures.

Zagori, a mountainous municipality in the Epirus region, was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2023. Although it is often presented as a successful example of heritage-led tourism, questions remain concerning the impact of incentive policies and the structural features of heritage hotels on population resilience.

Accordingly, this study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the public policies and legal frameworks that have shaped the protection of architectural heritage in mountain settlements, with a focus on Zagori?

RQ2: How have public policies and Incentives driven the development of heritage hospitality in mountain settlements, with reference to Zagori?

RQ3: In what ways have policy implementation and investment dynamics facilitated the conversion of traditional buildings into heritage hotels in Zagori?

RQ4: What is the structural profile of heritage hospitality in Zagori?

RQ5: To what extend has heritage hospitality contributed to the demographic resilience and revitalisation of Zagori’s mountain settlements?

This paper's methodological contribution lies in extending the Conservation– Development framework of Zhao et al. [8] by introducing a third analytical axis — “Investigation”. This addition enables the systematic linkage of public policy planning, tourism investment, accommodation data, and demographic dynamics, operationalised through quantitative indicators such as beds per capita, investment efficiency ratios, and correlations between tourism and population change. By combining policy analysis, archival research and spatial-temporal quantitative methods, the paper provides a comprehensive view of heritage hospitality as a means of promoting the resilience of mountain regions.

The paper makes two contributions: First, it proposes a replicable model for assessing heritage hospitality that connects policy frameworks with measurable territorial outcomes. Second, it provides the first comprehensive assessment of Zagori’s heritage hospitality sector since its UNESCO designation. The findings emphasize the interplay between policy and conservation frameworks, investment incentive systems, heritage hospitality, total accommodation, and population change. This provides a broader understanding of how heritage-driven tourism can promote the sustainability and adaptive resilience of mountain destinations.

2. Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Mountain Heritage Destinations

Mountains cover approximately 27% of the Earth’s surface, while mountain destinations attract 16–20% of global tourism demand [9]. Despite their importance, they are characterized by considerable heterogeneity and limited data availability, which complicates their management [10]. A review of the relevant literature and international policies highlights two fundamental characteristics of “mountainness”:

First, mountain areas are recognized as “hybrid nature–culture spaces”, combining high levels of ecological, landscape, and cultural diversity [11]. About 43% of Natura 2000 sites in the EU are located in mountain regions [11,12], while 17.5% of UNESCO World Heritage Sites are situated in such areas. Out of the 199 mountain-related sites, the majority are associated with architectural heritage; 115 are classified as cultural and 15 as mixed cultural landscapes [1,13].

Second, mountain regions worldwide face demographic decline and economic downturn, a trend that intensified after World War II [14,15]. In Southern Europe, extensive depopulation during the 1950s and 1960s led the EU to classify mountain areas as “Less-Favoured Areas” requiring specific policy support [12]. In Italy, 72% of abandoned municipalities are located in mountainous regions [16], while in Greece, less than 10% of the population inhabits 50% of the national territory classified as mountainous [17]. Similar trends have been observed in Eastern Europe since the 1990s [18], and in China, where the protection of traditional villages has gained national attention since 2012 due to urbanization and depopulation [19]. The abandonment of these regions seriously threatens their cultural and architectural heritage, leading to degradation and loss of identity [20].

The promotion of sustainable tourism, particularly heritage tourism, is internationally recognized as a key policy tool for the revitalization of mountain regions [19,20,21]. The UNESCO guidelines for integrated management of mountain World Heritage Sites, such as the Dolomites, are considered best practices for sustainable tourism development [22]. The European Union regards the cultural heritage of mountain regions as a strategic asset for sustainable development [23], supporting initiatives such as the EU Strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP) and funding through Interreg Europe and the European Regional Development Fund (€4.7 billion, 2014–2020). Cultural heritage thus emerges as a competitive advantage, enhancing local identity and attracting visitors through the uniqueness and intrinsic beauty of mountain landscapes [3,11,20,24].

2.2. Heritage Hotels as Vehicles for Sustainable Development in Mountain Destinations

A heritage hotel is a type of accommodation closely linked to the cultural, historical, or architectural identity of a place [5]. It is typically housed in renovated or historically significant buildings [4] and combines the preservation of cultural heritage with the enhancement of destination competitiveness [25,26]. Heritage hotels provide authentic experiences that connect local history with production and consumption [27,28], while their adaptive reuse meets both preservation requirements and the expectations of contemporary travelers [29]. Reflecting the principles of post-Fordist tourism, they emphasize uniqueness and personalization [30] and contribute to the sustainable development of rural and mountain regions by attracting visitors seeking authentic cultural experiences [3,31]. Moreover, they generally achieve higher occupancy rates and attract higher-income tourists [32,33].

Research on heritage hotels as a distinct field remains limited, particularly in disadvantaged areas such as mountain destinations. However, successful models exist, such as the Albergo Diffuso concept, developed in Italy in the 1980s and later expanded across Eastern Europe. This model promotes the revitalization of local heritage, socioeconomic development, and employment creation in small settlements [34,35,36]. It integrates hospitality infrastructure with local community life and culture [37,38]. Similarly, “hotel villages” such as Postignano, Castelfalfi, and Finochietto involve the full restoration and management of entire areas as tourism resorts, emphasizing cultural landscape preservation [16]. The Chinese RTTVR framework (Rural Tourism-based Traditional Village Revitalisation) promotes renewal through the enhancement of natural and cultural environments and the strengthening of local identity. In Yuanjia village for example, family-run guesthouses increased household incomes and fostered entrepreneurship, boosting the local economy ([19]. In Norway and Austria, traditional støl/alpe farms operate as tourist lodgings, offering authentic experiences while preserving traditions and the “sense of place” [39]. Overall, these initiatives reinforce cultural identity, employment, and sustainable development in rural and mountain regions.

At the policy level, international and European institutions such as UNESCO and the European Union emphasize the importance of developing appropriate forms of tourism for the revitalization of mountain areas [1,13]. Heritage hospitality serves both as a mechanism of protection and a competitive advantage, promoting local arts, crafts, music, and agri-food products as part of an integrated cultural tourism offer [31,40]. The Chinese Cultural–Tourism Integration (CTI) model, formally introduced in 2018, enhances sustainability by systematically linking the cultural and tourism industries [41]. CTI conceptualizes cultural and natural landscapes as interdependent subsystems within a broader socio-ecological framework, offering valuable parallels with European experiences in heritage hospitality.

In conclusion, heritage tourism in mountain areas represents a critical and dynamically evolving field of research and practice. Its success depends on adequate funding and close collaboration among stakeholders, entrepreneurs, and local communities [5,42]. The systematic study of heritage hotels as an independent domain—especially in mountain destinations—remains a promising and expanding area of academic inquiry, to which the present study seeks to contribute.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Case of Zagori's Designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2023

Zagori extends over approximately 1,000 km² in the Pindus mountain range of northwestern Greece. Its geographic isolation and rugged terrain have shaped a distinct identity, fostering the development of 46 stone-built villages, known as the Zagorochoria, interconnected by cobbled paths and arched bridges that reflect centuries of adaptation to the mountainous landscape. Natural landmarks such as the Vikos Gorge, the Aoos River, and Valia Kalda are protected within the Northern Pindus National Park and the Natura 2000 network, while the designation of Zagori as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2023 affirmed its outstanding value as a cultural landscape.

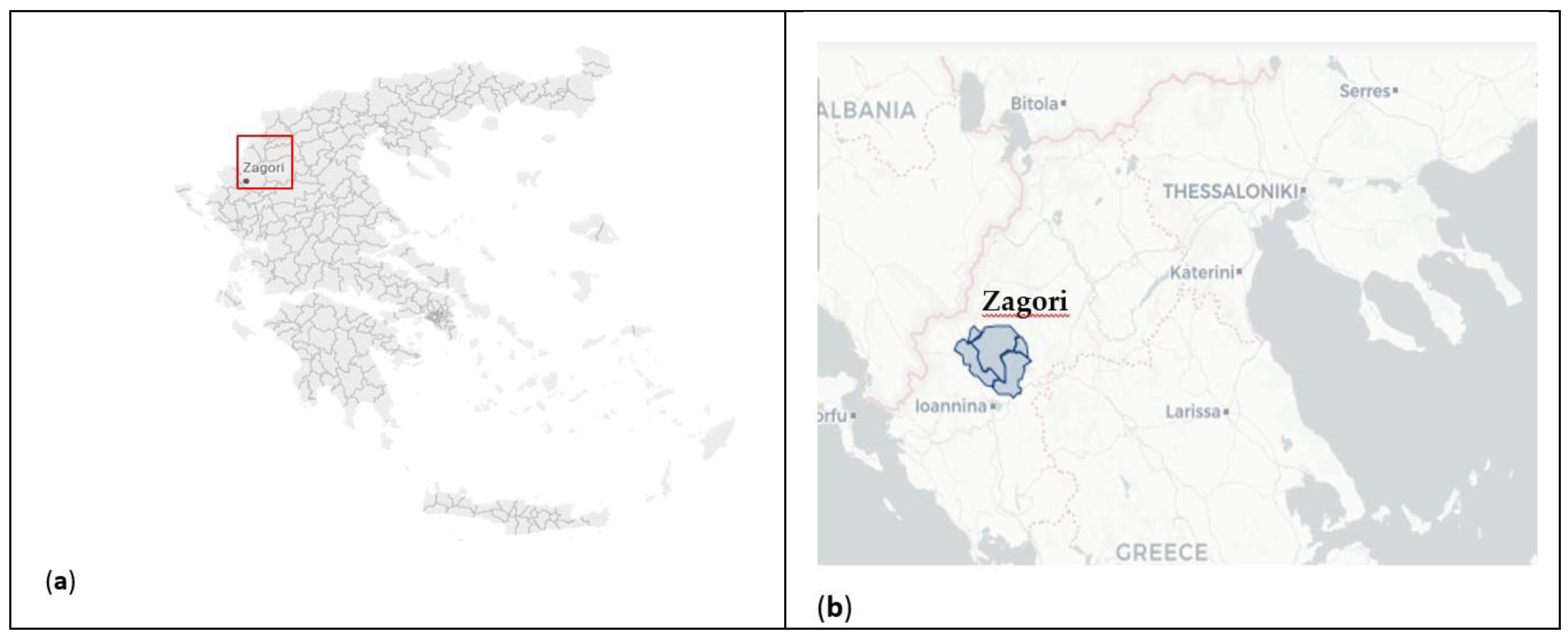

Scheme 1.

Maps (a-b) The location of the Municipality of Zagori, in Greece. Source: Map a — Open-access Datawrapper platform (

https://www.datawrapper.de/maps), Map b — Studies of Long Trails, Topoguide.gr.

Scheme 1.

Maps (a-b) The location of the Municipality of Zagori, in Greece. Source: Map a — Open-access Datawrapper platform (

https://www.datawrapper.de/maps), Map b — Studies of Long Trails, Topoguide.gr.

Historically, the local economy combined subsistence agriculture and livestock farming with extensive trade networks across the Balkans and Europe. Between the 17th and 19th centuries, Zagorian merchants amassed significant wealth, investing in schools, churches, and mansions, while the tradition of benefaction became a central social institution [43,44,45]. This period of prosperity left a lasting imprint on the built environment, shaping an architectural heritage that reflects both economic vitality and cultural sophistication. Despite post-war depopulation, tourism emerged as a key mechanism of resilience.

Organized tourism development began in 1965, when the GNTO converted traditional houses into guesthouses, primarily in Papigo and nearby villages. From 100,000 annual visitors in the 1980s, arrivals rose to 600,000 by 2008, before declining during the financial crisis and subsequently recovering in the following years [46]. Today, foreign visitors—mainly from the Netherlands, Germany, and Israel—constitute about 60% of the total, with an average stay of 2.5 nights [47]. The local economy now relies on heritage hotels, guesthouses, rooms to let and second homes, supported by state programs for the adaptive reuse of historic buildings and regional policies that recognize architecture as a key cultural asset.

Architecturally, Zagori represents a fusion of natural landscape and cultural identity. Its stone houses, with slate roofs and simple geometric forms, demonstrate both adaptation to the mountain environment and respect for local materials [45]. Churches, schools, and mansions bear witness to a past era of prosperity, while traditions and social customs reinforce community cohesion and an enduring ethic of generosity [48]. The region’s multicultural history has produced a mosaic of identities that converge into a shared mountain consciousness.

Overall, Zagori exemplifies a mountain heritage destination where geography, environment, architecture, and culture coexist harmoniously. Heritage tourism today serves as a mechanism for reconciling preservation and development, transforming Zagori into a living cultural landscape and a model of sustainable mountain tourism.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

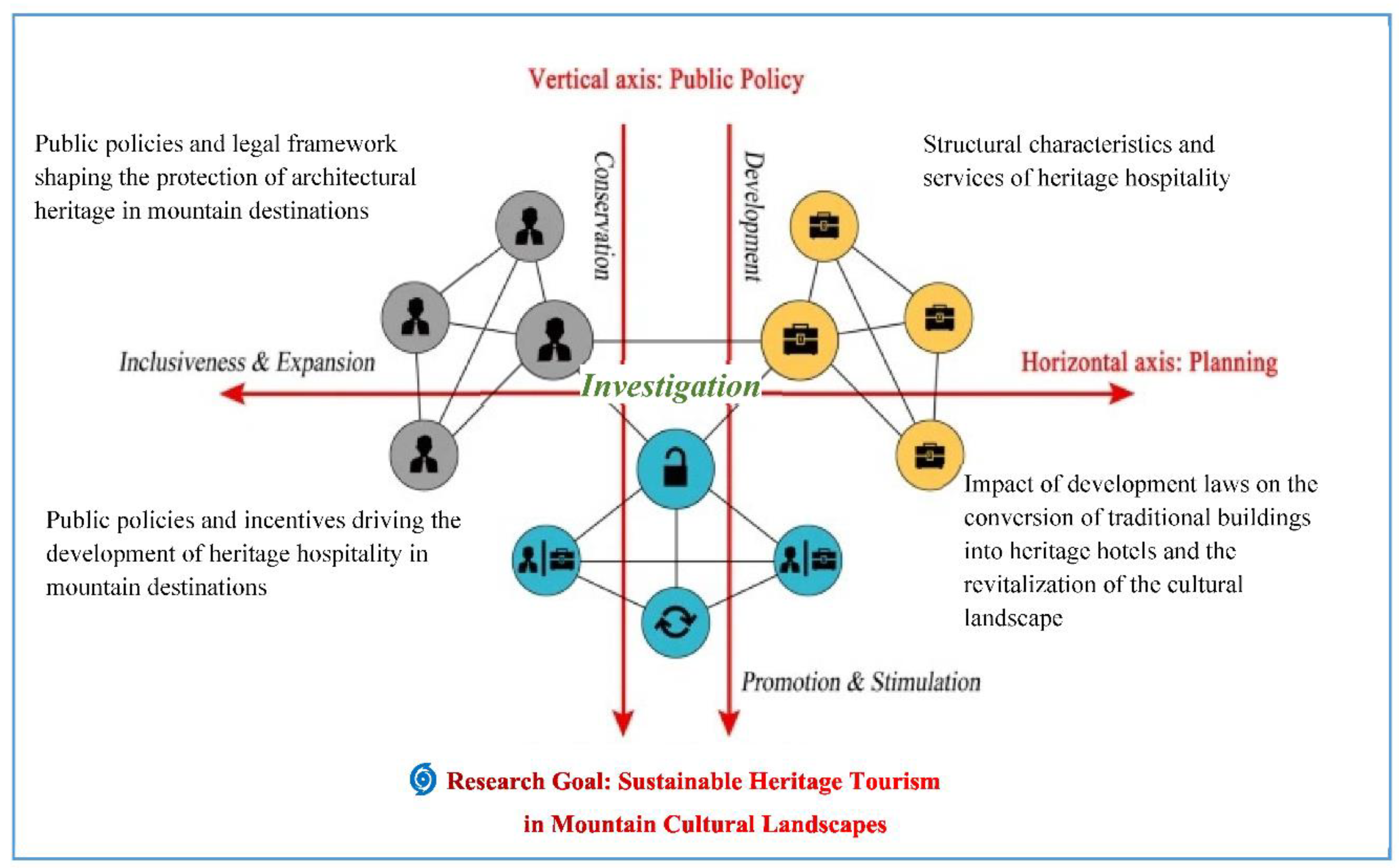

This study explores how policy planning and investment incentives transform traditional mountain settlements into heritage-led tourism destinations, focusing on Zagori as a representative case. Building on Zhao et al.’s [8] Conservation–Development framework, we introduce a third analytical axis—Investigation—which operationalizes planning instruments through empirical evidence (

Figure 1). In doing so, the axis links policy intentions and incentive implementation to their observable outcomes in total hotel sector and population dynamics.

The framework connects policy intent to on-the-ground outcomes through three axes:

Conservation: heritage protection rules, spatial planning and UNESCO designation;

Development: tourism incentives and development laws;

Investigation: empirical operationalization through indicators.

The Investigation axis converts policies into measurable variables—heritage hotel structure and quality, investment efficiency, and municipal units dynamics—revealing how successive incentive phases shaped spatially uneven heritage hospitality growth and its interaction with demographic stability across Zagori’s municipal units.

Within the Investigation axis, policies were operationalised through a concise set of indicators, including subsidy intensity (percentage of public contribution to total investment), completion time (in years), cost efficiency per bed (in constant 2021 euros), heritage beds per capita, total hotel beds per capita, population change (in percentage terms per decade) and the correlation between tourism density and demographic evolution. Additionally, a Quality Intensity Index was introduced to measure improvements in hospitality quality standards, i.e. star category upgrades in accordance with legislation and on a per-unit basis, capturing the qualitative dimension of development outcomes. These metrics quantify the impact of successive incentive phases on the scale, efficiency and spatial distribution of heritage hospitality, as well as its demographic impact.

Three complementary datasets were integrated:

Policy and planning corpus: National legislation and Greek National Tourism Organization (GNTO)/government circulars (1950s–2020s) concerning heritage protection and tourism incentives. Documents were coded thematically (heritage protection, hotel incentives, mountain zones. etc.) and chronologically to trace the shift from subsidy-driven frameworks (1990s–2000s) to second-generation sustainability-oriented incentives (post-2010).

Heritage-hotel register: This is the inventory of the Hellenic Chamber of Hotels (HCH) for the Zagori municipality, containing details such as name of units, bed capacity, star category, opening period, altitude, legal form and amenities. The following were derived: heritage hospitality structural characteristics, development phase (pre-1989, 1990s, 2000s and 2010–2024) and spatial dynamics (municipal units).

Investment files: The Greek Ministry of Development approvals for the conversion of traditional/listed buildings into hotels, including information on the investment cost, subsidy share, loan/private capital combination, completion time, job creation and bed capacity. Records were harmonised by law (1982, 1990, 1998, 2004, 2011 and 2016) to allow cross-phase comparisons.

The analysis unfolded in three stages:

Policy sequencing → investment phases: Mapping legislative frameworks against hotel formation periods, to identify policy 'windows' for heritage-hospitality development.

Structure → capacity → geography: profiling heritage hospitality in terms of size, quality and operation period, and then comparing their spatial distribution with the total tourism accommodation capacity, in order to assess whether heritage hospitality is marginal or central to upgrading the mountain destination.

Socio-spatial reading: juxtaposing heritage and total tourism densities with decadal population change and residences data to interpret correlations with tourism and demographic resilience—or, conversely, decline and over-concentration.

The results are presented in the form of tables, figures and maps that combine: (i) policy phases versus the evolution of heritage hospitality (ii) changes in the structure and quality of heritage hospitality over time and (iii) municipal unit tables showing population change, heritage hotel beds per capita (HBPC)/total beds per capita. The resulting data was recorded in Excel and analysed graphically using charts and thematic maps generated with the open-access Datawrapper platform (

https://www.datawrapper.de/maps).

This policy–archival–quantitative framework enables the tracing of transformation pathways from regulation to outcomes. It demonstrates how the policy implementation and heritage hospitality development jointly shape the revitalization and resilience of mountain destinations such as Zagori.

4. Results

4.1. Public Policies and Legal Frameworks Shaping the Protection of Architectural Heritage in Mountain Settlements, with a Focus on Zagori (RQ1)

In Greece, the systematic protection of modern architectural heritage effectively began after the 1975 Constitution, which explicitly mandated the preservation and safeguarding of traditional settlements as well as individual buildings or structures of architectural significance. A few years later, in 1978 and 1979, special Presidential Decrees designated 30 settlements in the Prefecture of Ioannina—most of them located in the Zagori region—as traditional, while an additional 60 settlements were placed under protection zones. Strict urban planning regulations were introduced, defining permitted land uses, the design of public spaces, and the restoration or construction of buildings. All building activity was brought under the supervision and approval of the Committee for Urban and Architectural Control. Thus, by the late 1970s, a new state policy emerged, aimed at preserving and promoting the identity of traditional settlements.

Over the following decades, the legal and institutional framework for heritage protection in Greece was further strengthened. In 1981, Greece ratified the 1972 UNESCO Convention (Paris) on the Protection of the World’s Natural and Cultural Heritage, and in 1992, it ratified the 1985 Granada Convention on the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe. The latter established the obligation to adopt a comprehensive policy for the protection of architectural heritage and emphasized the importance of integrating protected assets into the economic and social life of their communities.

An examination of the spatial distribution of traditional settlements in Greece reveals that the majority are found in island and lowland areas, while only 15.2% are located in mountainous zones (above 600 m). Significant concentrations exist in areas such as Zagorochoria and Pelion, where intense tourism activity has developed [6]. This low percentage reflects the demographic decline of mountain regions, since the designation of traditional settlements—and, more broadly, the protection of modern built heritage—largely depends on the active participation of local authorities and communities. This condition highlights both the lack of administrative capacity to retain population and the dynamic role of tourism as a driver of preservation and revitalization in mountain settlements.

4.2. Public Policies and Incentives Driving the Development of Heritage Hospitality in Mountain Settlements, with Reference to Zagori (RQ2)

The evolution of heritage hospitality in Greece’s mountain regions, particularly in Zagori, has been directly shaped by public incentive policies that encouraged the adaptive reuse of traditional architecture. Over the past seven decades, distinct policy phases can be identified, each characterized by specific objectives, instruments, and legislative interventions (see

Table 1).

The 1970s marked Greece’s accelerated entry into the international tourism scene [48]. During this period, the GNTO laid the foundations for linking tourism and architectural heritage by including Papigo village in Zagori in the Traditional Settlements Revitalization Program (1975–1992). Moreover, the 1973 Development Law introduced targeted incentives, encouraging the conversion of traditional and listed buildings into hotels by private investors. Disadvantaged mountain areas were classified as Development Zone D, and long-term loans covering up to 85% of reconstruction costs established the first substantial financial mechanism for adaptive reuse. Although implementation was limited, this period laid the groundwork for future heritage hospitality policies. Under GNTO’s supervision, 45 heritage buildings in Zagori received authorization for use as tourist accommodation.

In the 1980s, incentive policies shifted significantly towards supporting small and medium-sized decentralized tourism enterprises through grants and interest-rate subsidies. The Development Law 1262/1982 redefined the restoration and conversion of traditional buildings as productive investments, offering grants of up to 50%. The primary aims were to counter rural depopulation and create new income sources for local communities, linking tourism to cultural heritage preservation. This period proved crucial for Zagori, where traditional mansions were restored and converted into family-run guesthouses.

During the next two decades (1990–2009), incentive frameworks (Laws 1892/1990, 2601/1998, and 3299/2004) emphasized high subsidies (40–58%) and financial leasing mechanisms favoring small-scale restoration projects. The institutional recognition of “traditional accommodations” by the GNTO established heritage hotels as a distinct category within the national hospitality sector. In Zagori, these policies mobilized local and diaspora capital, leading to a wave of mansion and house restorations that made heritage hospitality the cornerstone of local tourism development.

The 2010s, under the strain of Greece’s financial crisis, brought a radical revision of investment frameworks (McKinsey & Company, 2012). Direct grants were replaced by tax incentives and sustainability-based criteria aligned with EU austerity measures and the Green Agenda (Laws 3908/2011 and 4399/2016). Zagori’s heritage hotels increasingly relied on EU-funded programs such as the NSRF 2014–2020 and the Recovery and Resilience Facility to improve energy efficiency and promote digital transformation. Despite financial constraints, this era fostered “second-generation incentives” focused on resilience, environmental adaptation, and smart growth.

The current policy phase (2021–present), shaped by Law 4887/2022, introduces differentiated incentives based on the level of tourism development, with particular emphasis on mountain regions such as Zagori. Aligned with the EU Green Deal and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it prioritizes digital transformation, circular economy practices, and low-impact adaptive reuse. The designation of Zagori as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2023 has further reinforced its role as a laboratory for sustainable, heritage-based tourism policy in mountain territories.

The development of heritage hospitality in Zagori clearly illustrates the shift from isolated architectural reuse projects—supervised by a centralized state authority—to an integrated policy framework that embeds cultural preservation within the principles of sustainability. Public policies have not only enabled the creation of heritage hotels but have also redefined architectural heritage as an active economic resource. Consequently, Zagori stands as a model of policy-driven rural regeneration, where long-term incentives, spatial planning, and adaptive reuse converge to create both a distinct tourism identity and a framework for community resilience.

4.3. Policy Implementation and Investment Dynamics Converting Traditional Buildings into Heritage Hotels (RQ3)

Between 1982 and 2016, 44 out of 52 heritage hotels (85%) in Zagori received funding under six major development laws, confirming the direct link between legislative frameworks and the growth of heritage hospitality (see

Table 2).

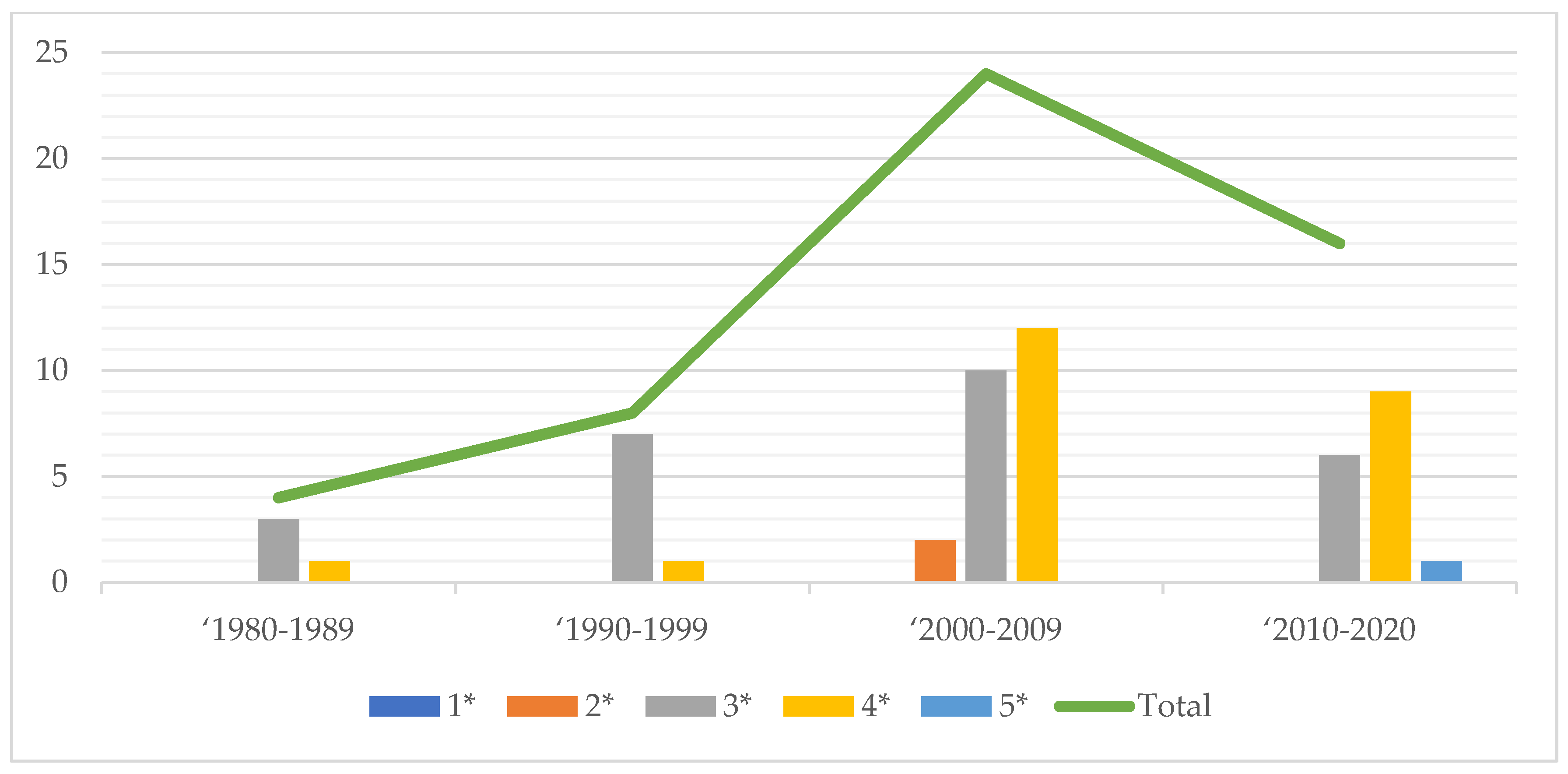

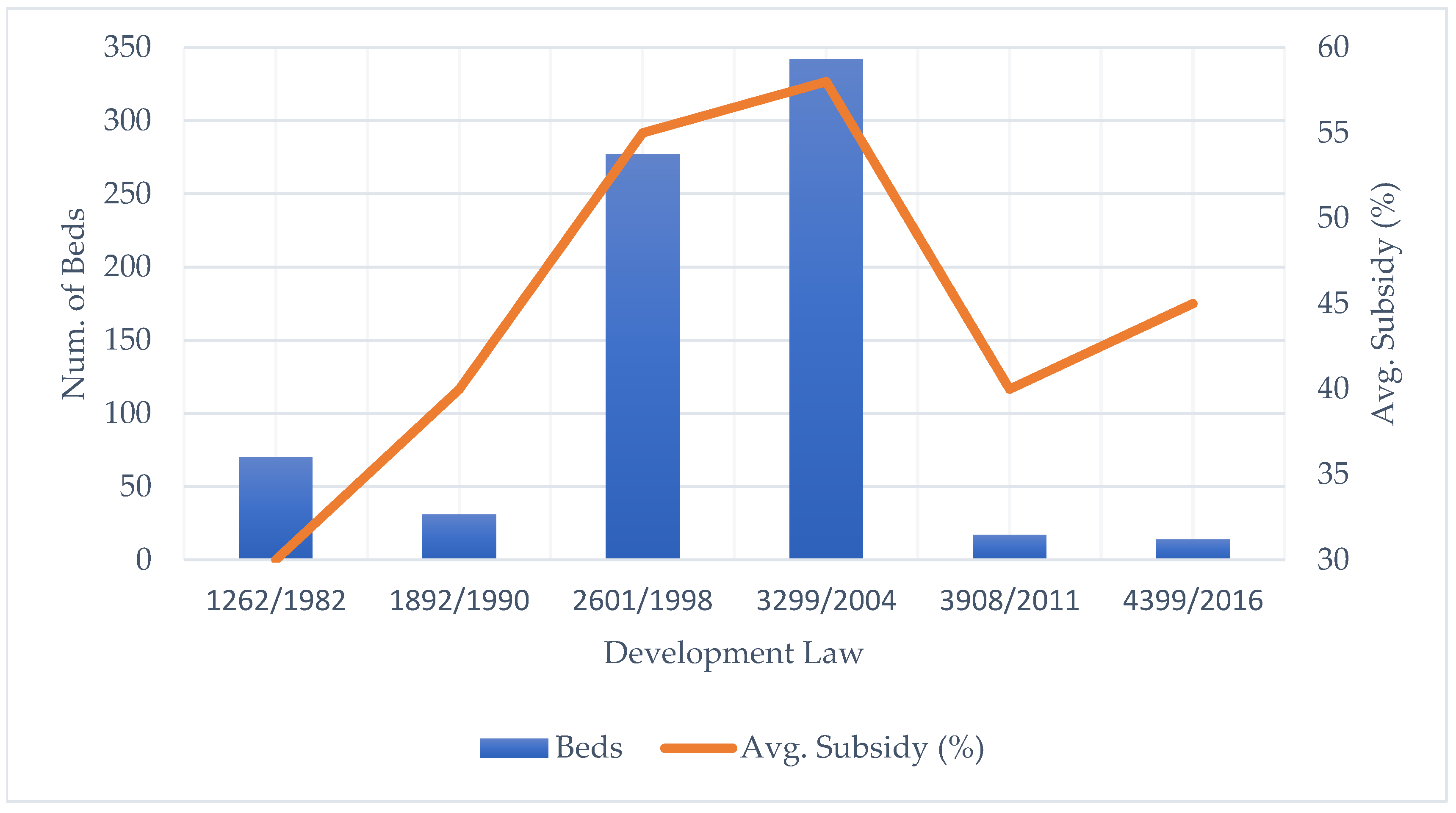

Three policy cycles stand out in the history of heritage hotel investment (see

Table 2 and

Figure 2):

The 1980s: The early frameworks (Law 1262/1982) introduced the concept of productive investment for restoration, offering grants of up to 50%. These schemes catalyzed the conversion of traditional mansions into small, family-run guesthouses, linking tourism development with local entrepreneurship.

The 1990–2009 period: Laws 2601/1998 and 3299/2004 were the most transformative, covering over half of total costs and generating 36 new heritage hotels with 619 new beds. They also signaled a qualitative shift towards higher standards of hospitality, with the first 4-star and 5-star heritage hotels being established during this period.

Post-2010: Growth slowed after 2010 due to the economic crisis and the development laws (3908/2011 and 4399/2016) emphasized sustainability and tax relief over direct subsidies. Many existing heritage hotels used EU funds (such as the NSRF 2014–2020 and the Recovery and Resilience Facility) to improve energy efficiency and digital transformation, thereby reinforcing their long-term resilience.

Investment efficiency indicators highlight the strong symbiosis between the state and the market that shaped this evolution (see

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Figure 2). Subsidy intensity peaked during the 1998–2004 period, with public funding often exceeding 50% of total investment. Completion efficiency improved over time, with average project durations falling from 4.5 years under the 1990 framework to just over 3 years in the 2000s, reflecting more efficient administrative processes.

The Quality Intensity Index measured by the increase in the number of projects in the 4-star and 5-star categories, indicates a deliberate policy orientation towards upgrading quality and achieving cultural differentiation (see

Figure 3) . This quality leap has coincided with rising costs per bed, highlighting the trade-off between improved hospitality standards and greater financial intensity. At constant 2021 prices, the average cost per bed increased from €36,500 in 1998 to €41,200 in 2004, indicating higher quality standards and more complex restoration work.

These illustrate the cumulative effect of policy continuity, including sustained funding, administrative refinement and an increasing focus on cultural quality. The result was a dual transformation of the built environment and local entrepreneurship. Heritage hotels became the embodiment of the state’s developmental vision, transforming architectural conservation into a profitable enterprise.

By 2010, total hotel capacity in Zagori had doubled compared to the 1990s, with heritage hotels accounting for the majority of new rooms and setting a standard for architectural integrity and service quality. Even when subsequent frameworks prioritized sustainability over expansion, the heritage hospitality proved remarkably resilient, adapting through small-scale digitalization, renewable energy retrofits and experiential tourism offerings.

The implementation of development laws transformed Zagori from a marginal mountain region into a developed mountain heritage destination. Consistent support from the state, combined with local entrepreneurship and cultural continuity, has turned the adaptive reuse of historic buildings into an important conservation tool and a vital means of enhancing rural resilience.

The overall impact of these legislative frameworks can be seen in both the number of restored buildings and the structure, ownership and spatial configuration of the resulting heritage hotels. Public incentives have shaped both the number of conversions that have taken place and the type of enterprises that have emerged, which are typically small-scale, family-run and deeply rooted in local society.

4.4. Structural Profile of Heritage Hotels in Zagori (RQ4)

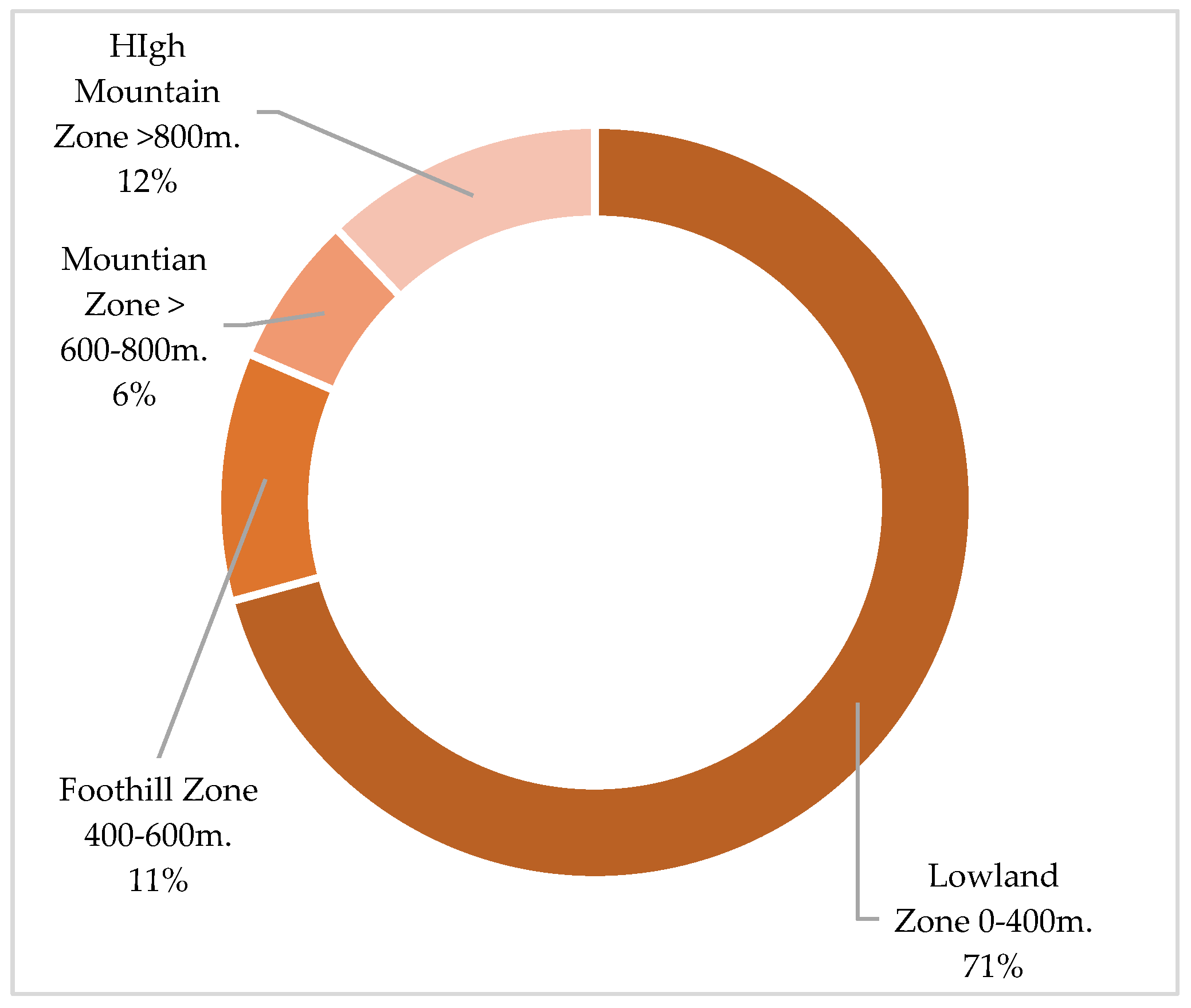

At the national level, Greece has 739 heritage hotels, accounting for 7.35% of total hotel capacity. The majority of these hotels are located in coastal and lowland areas (0–400 m), accounting for 71% of the total. Only 6% are located in mountain zones (600–800 m), and 12% are in high mountain zones above 800 m (see

Figure 4).

The Ioannina Regional Unit has the third largest share of heritage hospitality in Greece, accounting for 10% of the total (72 units). The Municipality of Zagori alone accounts for 68% of these, comprising 52 units with 850 beds distributed across 19 villages. Notably, 49 of these hotels (94%) are located above an altitude of 800 metres, confirming Zagori’s unique concentration of high-mountain heritage hospitality.

These hotels of Zagori are small-scale, independent enterprises, averaging 7 rooms (or 16 beds). They are predominantly owner-managed and family-run, operating all year-round, which reflects their deep local integration. This pattern is also evident in the legal form of their enterprise: 87% are personal companies (37% are sole proprietorships and 50% are general or limited partnerships), while only 13% are incorporated companies (S.A.), which are often the result of family enterprises transforming in order to secure long-term institutional stability and access investment incentives [49]. This ownership profile positions Zagori’s heritage hotels within the broader tradition of community-based entrepreneurship, connecting social cohesion with economic vitality.

In terms of facilities and amenities, nearly half of Zagori’s heritage hotels have in-room fireplaces, which reinforce their mountainous character. Other common facilities include restaurants, bars, room service, minibars, parking and pet-friendly policies. The absence of swimming pools highlights the hotels’ focus on nature-based tourism destination rather than a mass tourism market one.

Architecturally, over 90% of the hotels preserve vernacular features (stone walls, slate roofs, and timber interior elements). Beyond their structural and service attributes, the way heritage hotels present their identity online is a crucial factor. Many highlight the historic narrative of their buildings by presenting information such as construction dates, former uses and restoration details. In marketing terms, they are positioned as traditional hotels or guesthouses that foreground local materials, furniture, crafts and narratives, embedding tourism accommodation within the cultural landscape.

In summary, Zagori’s heritage hotels constitute a distinctive mountain hospitality model, defined by three interrelated attributes (see

Figure 5):

These findings confirm that Zagori’s heritage hotels constitute a distinct, high-altitude hospitality ecosystem that differs significantly from Greece’s dominant coastal model (see

Table 4). This ecosystem did not emerge as a result of spontaneous market forces, but rather through sustained state intervention through incentive laws and adaptive reuse policies. This policy–entrepreneurship synergy shaped both the physical and institutional landscape of tourism in Zagori, transforming heritage preservation into a driver of local development.

4.5. The Contribution of Heritage Hospitality to the Demographic Resilience and Revitalization of Zagori’s Mountain Settlements (RQ5)

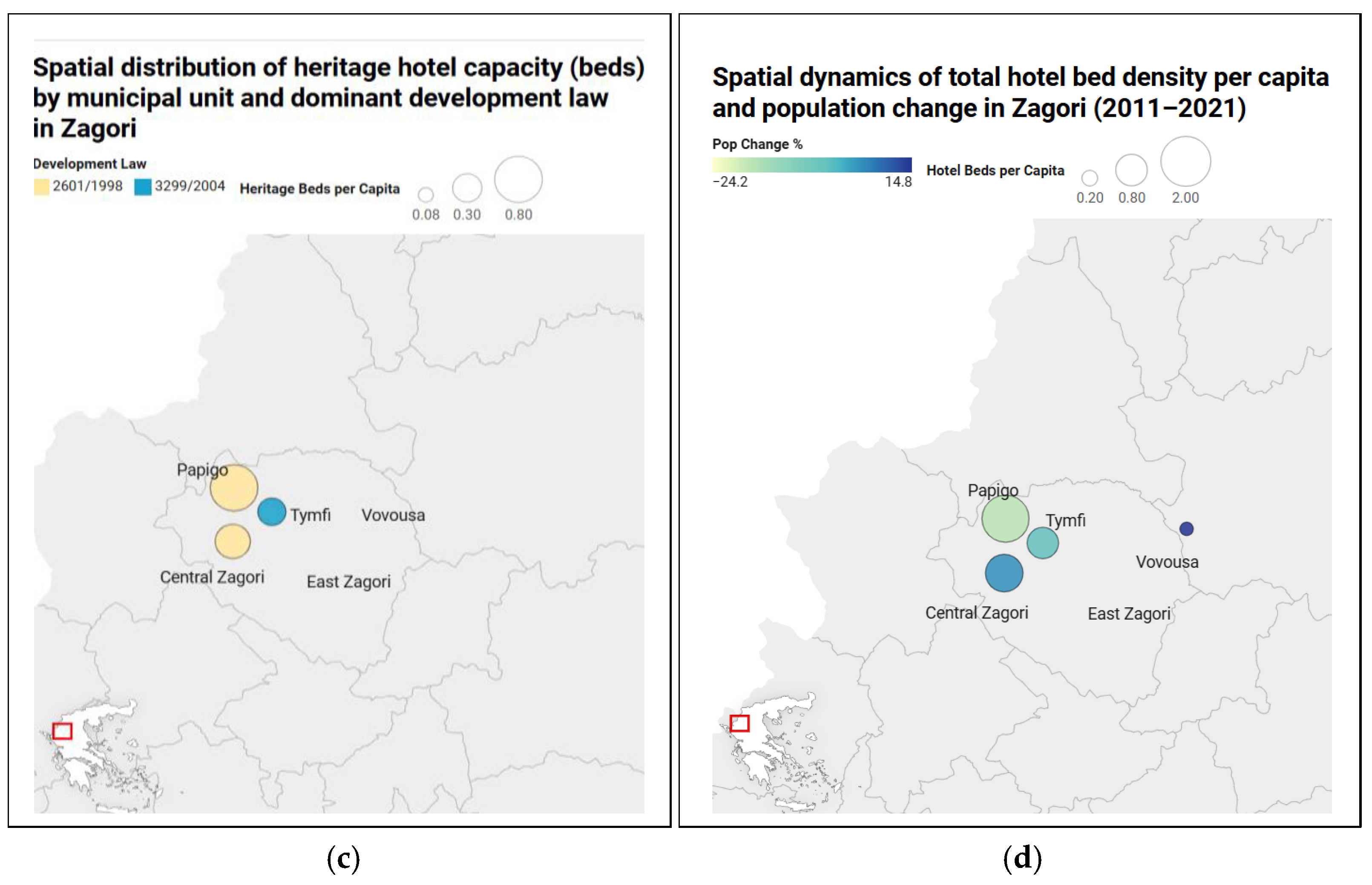

The evolution of Zagori’s population between 2001 and 2021 illustrates the dual role of tourism as a stabilising and transformative force within the wider context of rural depopulation in Greece. The growth of heritage hospitality has reshaped local settlement patterns, creating distinct spatial differences across the municipality’s units (see

Table 5;

Scheme 2c–d).

During the decade 2001–2011, the rate of population decline slowed immediately following the hotel investment boom (Laws 2601/1998 and 3299/2004). This relative stabilization was due to the direct and indirect impacts of tourism-related employment and the adaptive reuse of traditional housing stock. Papigo stands out with its remarkable population increase (65.8%), coinciding with the establishment of heritage hotels and the highest bed density per capita (0,80).

In the subsequent decade (2011–2021) a lack of new large-scale incentives and limited establishment of new heritage hotels resulted in an overall demographic contraction of -9.4%. However, local patterns diverged sharply: Central Zagori, the main tourism hub, was the only area in Epirus to experience population growth (4.7%), driven by its extensive hospitality infrastructure (1.1 total beds and 0.42 heritage beds per capita). Tymfi experienced near-stability (–1.7% with 0.75 total beds per capita). Although Papigo exhibited the highest tourism intensity (1.78 beds per capita), it also experienced a population decrease of 16.5%, highlighting the limitations of carrying capacity and the consequences of overconcentration. In contrast, East Zagori, with no hotel infrastructure and only a few rent rooms, suffered a sharp decline of 24.2%, while Vovousa, with its modest community-based tourism, grew by 14.8%.

Heritage hotels have acted as catalysts in revitalising the housing stock, preserving vernacular architecture and stimulating restoration activity in the surrounding areas, particularly in Central Zagori and Papigo. Meanwhile, the proliferation of short-term rentals has extended this transformation to unlisted properties, creating the mixed 'tourism–residence' landscape that is typical of Mediterranean mountain areas.

5. Discussion

The findings demonstrate that the evolution of heritage hospitality in Zagori has been shaped by long-term policy consistency, family entrepreneurship and the adaptive reuse of vernacular architecture, rather than spontaneous market forces. In this respect, the case study supports the argument that policy-driven investment frameworks can foster resili-ence in mountain cultural landscapes [1,3,12,13,14,15]. The Conservation–Development–Investigation model, employed in this study, provides an analytical bridge between herit-age governance and tourism performance by operationalizing the transition from legisla-tive intent to measurable socio-spatial outcomes.

The results reveal three key patterns. Firstly, heritage hospitality in Zagori did not emerge from spontaneous market dynamics, but rather from continuous public interven-tion, initiated through preservation policy frameworks, and then through the Develop-ment Laws of 1982–2016 [6,7,34]. These successive frameworks channeled public and private resources towards the restoration of traditional/listed buildings, creating a network of small-scale, high-altitude hotels that combine cultural authenticity with sustain-able development. Secondly, in areas where policy incentives aligned with local initiatives, such as in Central Zagori and Tymfi, heritage-driven tourism can counteract depopulation and generate diversified income structures. This is consistent with international evidence on the capacity of rural tourism, when anchored in place-based heritage, to sup-port community resilience [3,34,35,36,37,38]. Thirdly, the contrasting cases of Papigo and East Zagori illustrate two key limitations of the model: overconcentration which risks exceed-ing local carrying capacity, and lack of investment which leads to functional decline.

From a policy perspective, the study provides empirical evidence that investment in-centives shape not only tourism infrastructure, but also the structures of municipal units. Heritage hotels acted as catalysts for broader processes of spatial regeneration, reviving abandoned mansions and houses, sustaining local crafts and reinforcing landscape in-tegrity [50]. However, the rapid spread of short-term rentals has blurred the distinction be-tween heritage hospitality, tourism accommodation and seasonal housing, highlighting the need for the tourism–residence interface to be regulated more effectively. The maps in

Scheme 2 visually confirm these uneven dynamics, illustrating the clustering of total tourism accommodation and the demographic outcomes associated with different levels of development.

In comparative terms, Zagori represents a distinct Mediterranean model of heritage hospitality, differing from the more fragmented rural tourism Albergo Diffuso trajectories found in southern Italy. Building on the Albergo Diffuso concept, it embeds adaptive reuse within a coherent legal and planning framework, with quality improvements driven by family entrepreneurship [34,35,36,37,38,49]. The region’s long tradition of benefaction and social capital—mobilising both residents and the diaspora—underpinned collective steward-ship of architectural identity [44,45]. This demonstrates that heritage preservation is as much a social practice as a regulatory one.

From a methodological perspective, adding the Investigation axis to Zhao et al.’s Conservation–Development framework enables the operationalization of policy sequenc-ing, investment efficiency and bed-to-population ratio as monitoring tools. This approach is particularly useful for small destinations where detailed datasets are scarce, but the impacts of policies are tangible [8]. This methodological contribution offers a transferable template for linking policy frameworks and investment incentive schemes to outcomes in mountain cultural landscapes.

Finally, the findings have implications for sustainable heritage governance. As Zagori enters a new phase, following its inscription as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2023, managing growth without compromising authenticity, becomes central. Future governance should emphasize participatory mechanisms, continuous monitoring of car-rying capacity and differentiated policies between the core and peripheral municipal units — principles that are consistent with EU mountain guidance and sustainable heritage agendas [12,13,14,15,22,23].

6. Conclusions

This study shows that heritage-based tourism led by policy can foster socio-economic and demographic resilience while reinforcing conservation goals. By linking public incentives with measurable demographic and spatial outcomes, the research shows that heritage-led tourism in Zagori was the result of sustained policy planning rather than spontaneous development. The adaptive reuse of traditional buildings under successive incentive laws has created a micro-scale, high-altitude hospitality network that contributes to preservation and livelihood diversification.

The main conclusions are:

Policy continuity matters: Long-term incentive schemes and the recognition of traditional settlements created the institutional foundation for sustainable heritage reuse.

Community participation amplifies policy: Family-run heritage hotels converted subsidies into durable place-rooted assets, sustaining authenticity and local identity.

Heritage hospitality supports demographic resilience: Municipal units combining heritage and general tourism accommodation (Central Zagori and Tymfi) experienced stabilization or growth, while units without investment declined.

Balanced spatial distribution is essential. Overconcentration (e.g., Papigo) and neglect (e.g., East Zagori) lead to asymmetries in population trends and landscape management.

These findings establish Zagori as a replicable model for heritage-led mountain development, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals — particularly SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 15 (Life on Land). The policy insights derived from this study can inform the development of other Mediterranean mountain regions that are facing similar challenges of depopulation and landscape degradation.

The research is limited mainly by data availability and scope. Firstly, the analysis relies on secondary data sources such as official hotel registers, census statistics and policy archives. Despite triangulation, these sources may not fully capture informal or seasonal tourism activities. Secondly, the study focuses on one UNESCO-listed region, which limits the ability to generalize beyond comparable cultural landscapes. Thirdly, while quantitative indicators are effective for identifying trends, they cannot capture qualitative aspects such as visitor experience, cultural attachment or governance dynamics.

Therefore, future research should expand the empirical base by conducting household and visitor surveys as well as carrying out longitudinal tracking of heritage hospitality performance. Comparative studies of other Mediterranean mountain destinations could validate the transferability of the Conservation–Development–Investigation framework and refine its policy implications for heritage-led sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V., G.T. and E.S.; methodology, A.V. and G.T.; validation, A.C. and E.S.; formal analysis, A.V., A.C. and E.S.; investigation, G.T.; resources, A.C. and G.T.; data curation, A.V. and G.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V. and G.T.; writing—review and editing, A.C. and E.S.; visualization, A.V.; supervision, A.V.; project administration G.T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the assistance of the Hellenic Chamber of Hotels in the provision of data from the register of heritage hotels of Zagori.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rössler, M.;. World Heritage and Mountain Sites. . In Book Montology Palimpsest: A Primer of Mountain Geographies; Sarmiento F.O., Ed.; Springer: Cham 2022; 413-425. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Geng, S.; Chau, H.-W.; Wang, T.; Jamei, E.; Vrcelj, Z. Adaptive Reuse of Russian Influenced Religious Architecture in Harbin: Architectural Identity and Heritage Tourism. Heritage 2024, 7, 7115–7141. [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.; Kastenholz, E. Rural tourism: the evolution of practice and research approaches – towards a new generation concept? Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2015, 23(8–9). 1133-1156. [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.F.; Shi, W.L. Elucidating the characteristics of heritage hotels. Anatolia 2020, 31(4). 670-673. [CrossRef]

- Sarantakou, E.; Tsamos, G.; Vlami. A; Christidou. A.; Maniati, E. Factors of Authenticity: Exploring Santorini’s Heritage Hotels. Tourism and Hospitality 2024, 5(3), 782–799. [CrossRef]

- Pozoukidou, G.; Papageorgiou, M. Protection of traditional settlements in Greece: Legislation and practice. In Proceedings of the Conference: International Conference on Changing Cities: Spatial, morphological, formal & socio-economic dimensions , Skiathos island. Greece, 18-21 June 2013.

- Poulios, I. Discussing strategy in heritage conservation: Living heritage approach as an example of strategic innovation. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 2014, 4(1), 16–34. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhang Z. Public policies and conservation plans of historic urban landscapes under the sustainable heritage tourism milieu: discussions on the equilibrium model on Kulangsu Island, UNESCO World Heritage site. Built Heritage 2023, 7(6). 02-20. [CrossRef]

- Batista e Silva, F.; Barranco, R.; Proietti, P.; Pigaiani, C.; Lavalle, C. A new European regional tourism typology based on hotel location patterns and geographical criteria. Annals of Tourism Research 2021, 89. 01-06. [CrossRef]

- Sarantakou, E. Contemporary Challenges in Destination Planning: A Geographical Typology Approach. Geographies 2023, 3(4), 687–708. [CrossRef]

- Interreg Europe. Mountain Cultural Heritage: Policy, Solutions, and EU Support 2021.

- EEA. European Ecological Backbone: Recognising the True Value of Our Mountains. In Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 2010, 22(1). [CrossRef]

- Euromontana, V.D.D. (2018). Cultural heritage: an asset rooted in the territory synonymous with attractiveness and the future of our mountains! In Proceedings of the XI European Mountain Convention. Vatra Dornei, Romania. 25-27 September 2018.

- European Commission. Mountain Areas in Europe: Analysis of mountain areas in EU member states, acceding and other European countries. 2004.

- European Parliament. Resolution on the EU Agenda for Rural, Mountainous and Remote Areas. 2018.

- Di Figlia, L. Turnaround: abandoned villages, from discarded elements of modern Italian society to possible resources. International Planning Studies 2016, 21(3). [CrossRef]

- Beriatos, H. A spatial and environmental approach to mountain areas. In Mountain Areas: Environment, Society, Development. University of Thessaly Press. Greece. 2005.

- Vaishar, A.; Vavrouchová, H.; Lešková, A.; Peřinková, V. Depopulation and extinction of villages in moravia and the czech part of silesia since world war ii. Land 2021, 10(4). [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tourism Management 2017, 63. [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Resolution on the EU Agenda for Rural, Mountainous and Remote Areas. 2018.

- Duglio, S.; Bonadonna, A.; Letey, M.; Peira, G.; Zavattaro, L.; Lombardi, G. Tourism Development in Inner Mountain Areas—The Local Stakeholders’ Point of View through a Mixed Method Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11.5997. [CrossRef]

- Della Lucia, M., & Franch, M. The effects of local context on World Heritage Site management: the Dolomites Natural World Heritage Site, Italy. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2017, 25(12). 1756-1775. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Towards an integrated approach to cultural heritage in Europe. 2014.

- European Commission. Economic benefits of material cultural heritage in mountain areas. 2019.

- Lux, M.S.; Tzortzi, J.N.. From thermal city to well-being landscape: a proposal for the UNESCO Heritage Site of Pineta Park in Montecatini Terme. Heritage 2025, 8 (123). [CrossRef]

- Munar, A.M.; Ooi, C.-S. What Social Media Tell Us about the Heritage Experience; CLCS Working Paper Series; Department of International Economics and Management, Copenhagen Business School: Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2012.

- Moscatelli, M. Heritage as a driver of sustainable tourism development: The case study of the Darb Zubaydah Hajj Pilgrimage Route. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7055. [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D. A cultural hospitality framework for heritage accommodations. Journal Heritage Tourism 2015, 10, 184–190. [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Gronau, W., Enhancing competences for co-creating appealing and meaningful cultural heritage experiences in tourism. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2020. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C. Post-Fordist tourism: Trends and implications. Tourism Recreation Research 2011, 36(3), 209–218.

- Henderson, J.C. Selling the past: Heritage hotels. Tourism 2013, 61(4).

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S. Authenticity, Involvement, and Nostalgia in Heritage Hotels in the Era of Digital Technology: A Moderated Meditation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(10). [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Fayyad, S.; Ammar, S.; Abdulaziz, T.A., Mahmoud, S.W. Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Houses and Hotel Conative Loyalty: Digital Technology as a Moderator and Memorable Tourism and Hospitality Experience as a Mediator. Sustainability 2022, 14(6). [CrossRef]

- Cucari, N.; Wankowicz, E.; Esposito De Falco, S. Rural tourism and Albergo Diffuso: A case study for sustainable land-use planning. Land Use Policy2019, 82. [CrossRef]

- Hrvatin, S.; Markuz, A.; Miklošević, I. Analysis and evaluation of albergo diffuso as sustainable business model. Oeconomica Jadertina 2022, 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Morena, M.; Truppi, T.; Del Gatto, M.L. Sustainable tourism and development: the model of the Albergo Diffuso. Journal of Place Management and Development 2017, 10(5). [CrossRef]

- Confalonieri, M. A typical Italian phenomenon: The “albergo diffuso”. Tourism Management 2011, 32(3). [CrossRef]

- Presenza, A.; Messeni Petruzzelli, A.; Sheehan, L. Innovation trough tradition in hospitality. The Italian case of Albergo Diffuso. Tourism Management 2019, 72. [CrossRef]

- Daugstad, K.; Kirchengast, C. Authenticity and the pseudo-backstage of agri-tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 2013, 43. [CrossRef]

- Floričić, T.; Jurica, K. Wine Hotels—Intangible Heritage, Storytelling and Co-Creation in Specific Tourism Offer. Heritage 2023, 6(3). [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, Sh.; Li, H.; Niu, L.; Zhang, H. Evaluation and Enhancement of Landscape Resilience in Mountain-Water Town from the Perspective of Cultural and Tourism Integration: Case Study of Yinji Town, Wugang City, Sustainability 2025. Preprints.

- Lee, W.; Chhabra, D. Heritage hotels and historic lodging: Perspectives on experiential marketing and sustainable culture. Journal of Heritage Tourism 2015, 10 (2). [CrossRef]

- Vlachopoulou-Oikonomou, A., The Zagoria of Epirus: History from the Paleolithic era to Roman rule, In EPIRUS, Seven Days of the Daily 1997, Greece. 146-149.

- Karametou, P. The Role of Social Capital in the Development of Mountainous Rural Areas in Greece: A Case Study of the Pelion and Zagori Regions, Doctoral Thesis 2009, Harokopio University, Greece.

- Toufegopoulou, A., Alternative forms of tourism and emerging tourist destinations. The role of planning in their spatial structure and the conditions for their development, Doctoral Thesis 2014, National Technical University of Athens, Greece.

- Syngounas, S., Analysis and evaluation of visitor numbers and the tourist profile of Zagori, In Proceedings of the Conference Conference: The Contribution of the National Technical University of Athens to the Integrated Development of Zagori. Research Center of the National Technical University of Athens, Ano Pedina, Zagori. Greece. 20 July 2013,.

- Tzimas, O.,P., Rural tourism in the Zagori region, Epirus, and the evaluation of the tourist experience by visitors. Thesis, Hellenic Open University, Greece.Giotis, A., Traditional Settlements: Transition from the Traditional Regime to Modern Reality, Doctoral Thesis 2023, University of the Aegean, Greece.

- Vlami, A.; Tsamos, G.; Zacharatos, G. Tourism planning and policy in selected mountainous areas of Greece, Tourismos 2012, 7(2), 481-494. [CrossRef]

- Harlaftis, G.; Vlami, A. Greek Family Business of the Tertiary Sector, 19th–20th Centuries: Shipping and Tourism, In Global Family Capitalism: A Business History Perspective, Fernández Pérez, P., Ed.; Routledge. London, 2025. pp. 129-146.

- Vythoulka, A.; Caradimas, C.; Delegou, E.; Moropoulou, A. Cultural Heritage Preservation and Management in Areas Affected by Overtourism—A Conceptual Framework for the Adaptive Reuse of Sarakina Mansion in Zakynthos, Greece. Heritage 2025, 8, 288. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).