1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of autonomous driving technologies, pedestrian trajectory prediction has become a critical component in ensuring road traffic safety. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 1.27 million fatalities occur globally each year due to road traffic accidents, with pedestrian-related incidents accounting for over 22% of cases. In urban environments, this proportion increases to 35% [

1]. Consequently, achieving high-accuracy pedestrian trajectory prediction is essential not only for mitigating traffic risks but also for providing prior knowledge to path planning and decision-making modules in autonomous driving systems.

Most existing pedestrian trajectory prediction methods are designed for fixed-camera or global surveillance perspectives, where they demonstrate strong performance in static monitoring scenarios [

2]. However, extending such approaches to vehicle-mounted cameras introduces several challenges. First, the mobility of vehicle-mounted cameras leads to continuously changing viewpoints, making static coordinate-based modeling inadequate [

3]. Second, the complexity of real-world road environments—with vehicles, buildings, and frequent occlusions—places higher demands on both scene understanding and trajectory prediction [

4]. Furthermore, pedestrian motion is jointly influenced by spatial layout and temporal evolution, creating strong spatiotemporal coupling effects that necessitate more advanced modeling strategies [

5].

Although some studies have employed deep learning to enhance modeling capabilities, most existing approaches still target fixed-view scenarios and struggle to adapt effectively to the dynamic and complex conditions encountered from vehicle-mounted perspectives.

To address these challenges, we propose V-PTP-IC (Vehicle-view Pedestrian Trajectory Prediction with Interaction Considerations), a novel end-to-end framework that integrates social interaction modeling with dynamic scene perception. Specifically, the data preprocessing module processes multi-pedestrian trajectory data, applying SIFT-based static keypoint matching to compensate for camera-induced motion and stabilize trajectories. The scene feature extraction module employs VGG19 to extract dynamic scene features, providing contextual semantics to enhance trajectory prediction. The core of the model, the pedestrian interaction modeling block, adopts LSTM-based networks to capture complex interactions between pedestrians and their dynamic scene. A feature fusion component integrates both trajectory and scene information over time, improving prediction accuracy. Finally, the model prediction module leverages tailored loss functions to optimize performance for both trajectory and scene prediction tasks. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

We propose V-PTP-IC, a unified end-to-end framework that combines social interaction modeling, dynamic scene feature extraction, and adaptation to vehicle-mounted camera viewpoints for joint trajectory and scene prediction.

We introduce a SIFT-based static keypoint matching strategy to compensate for camera-induced motion, reducing trajectory jitter and improving stability.

We develop a dynamic scene perception mechanism employing VGG19 to encode environmental semantics, thereby enhancing prediction accuracy.

We conduct extensive evaluation on the JAAD in-vehicle dataset, demonstrating that V-PTP-IC achieves a 22.2% improvement in ADE and a 25.8% improvement in FDE over state-of-the-art methods.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work;

Section 3 details the methodology of V-PTP-IC;

Section 4 presents experimental results; and

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

Pedestrian trajectory prediction aims to forecast future movement paths based on historical trajectory data while considering interactions with surrounding environmental elements, such as other pedestrians, vehicles, and static obstacles. With the increasing adoption of visual sensing technologies, existing research can be categorized into two primary perspectives: fixed/global-view and vehicle-mounted-view approaches.

2.1. Fixed/Global-View Methods

Under fixed-camera or global-view settings, pedestrian trajectory prediction approaches can broadly be divided into three groups: physics-based models, traditional machine learning methods, and deep learning models. Physics-based approaches, such as constant velocity (CV), constant acceleration (CA), reasoning-based models [

6], expert systems [

7], and other handcrafted methods [

8], offer computational efficiency by assuming simplified kinematic patterns. However, such methods often fail to capture nonlinear movements and complex social interactions among pedestrians, limiting their applicability in crowded or highly dynamic scene. To address these limitations, extensions based on the Markov Decision Process (MDP) [

9,

10] have been proposed, enhancing adaptability by explicitly modeling state transitions and decision-making processes.

Traditional machine learning techniques, including Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) [

11], Gaussian Processes (GPs) [

12], and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) [

13], improve prediction accuracy by incorporating probabilistic reasoning and data-driven learning. Nonetheless, these approaches typically rely on handcrafted features and perform effectively only on small-scale datasets, suffering from limited scalability in high-dimensional or complex urban environments.

Deep learning-based models have recently emerged as the dominant paradigm, owing to their capability to automatically learn spatiotemporal dependencies and social interaction patterns from large datasets. Representative examples include Social-LSTM [

14], Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) [

15], and Transformer-based architectures [

16], which can capture long-range temporal correlations and pedestrian-to-pedestrian interactions. Building upon these foundations, the SoPhie model [

17] integrates Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and attention mechanisms to improve trajectory diversity and semantic understanding, while more advanced frameworks such as Social-STGCNN [

18] and STARnet [

19] exploit graph-structured representations and spatiotemporal convolutional features to further enhance prediction performance. Despite these advancements, most existing methods are tailored for fixed surveillance viewpoints, and their performance deteriorates when applied to vehicle-mounted camera scenarios, where viewpoint dynamics, occlusion, and environmental variability are more pronounced.

2.2. Vehicle-Mounted-View Methods

Research on pedestrian trajectory prediction from the vehicle-mounted camera perspective remains relatively limited, yet this setting introduces substantially greater challenges compared to fixed-camera scenarios [

20]. One fundamental difficulty arises from viewpoint variability and image distortion: the continuous motion of vehicle-mounted cameras induces non-stationary coordinate systems and frequent perspective shifts, while wide-angle lenses can result in fisheye distortion. To mitigate these effects, calibration procedures or fisheye-specific camera models have been proposed [

21], although these approaches are often sensitive to noise and require precise parameter tuning.

Another major challenge is occlusion and the accurate modeling of multi-pedestrian interactions. Compared with fixed-camera views, vehicle-mounted perspectives are more susceptible to partial visibility caused by moving objects or road infrastructure. Recent efforts, such as Social-STGCNN [

18], have applied Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to explicitly capture interaction dependencies under occlusion. Furthermore, integrating contextual environmental factors—including road geometry, crosswalk placement, and traffic signal states—has been shown to improve semantic understanding and prediction accuracy in real-world driving scenes [

22].

Despite these advances, existing studies often address these challenges in isolation, without providing a unified framework that simultaneously handles viewpoint dynamics, occlusion, and environmental influences. This gap motivates our work, in which we introduce V-PTP-IC, a feature-fusion framework that combines trajectory stabilization, social interaction modeling, and dynamic scene feature extraction to achieve robust and accurate pedestrian trajectory prediction in vehicle-mounted camera settings.

3. V-PTP-IC

3.1. Model Overview

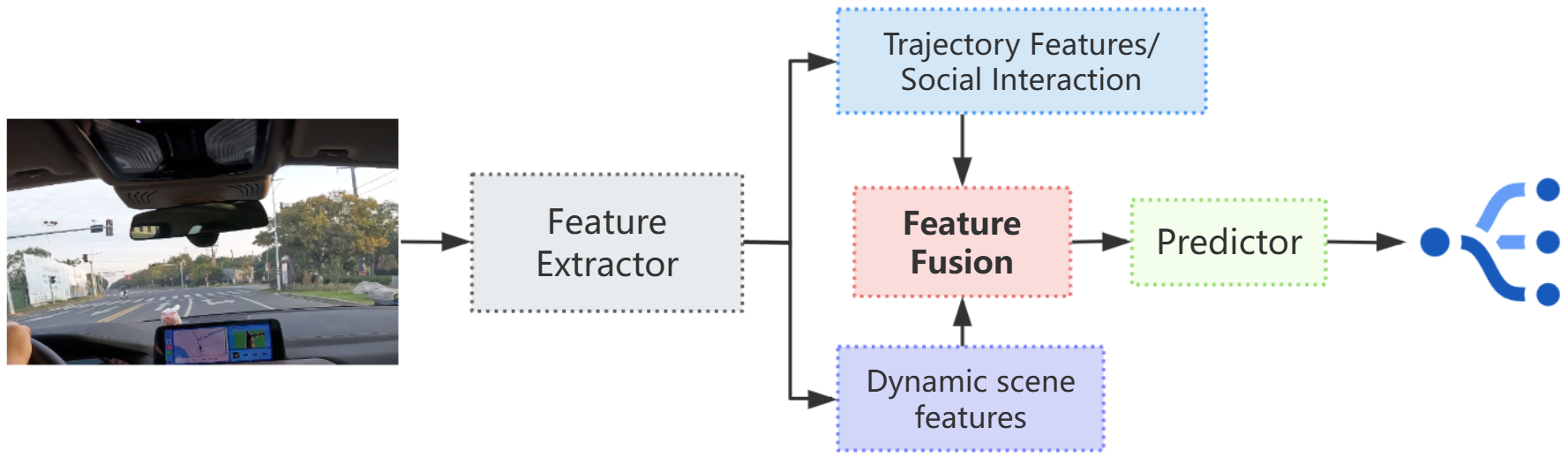

The proposed V-PTP-IC framework is designed to perform robust pedestrian trajectory prediction from vehicle-mounted camera perspectives under dynamic driving conditions. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the framework integrates object detection and tracking, trajectory stabilization, dynamic scene feature extraction, social interaction modeling, and final trajectory prediction into a unified end-to-end pipeline. For the perception stage, YOLOv10 is applied to detect pedestrians in real time, while Simple Online and Realtime Tracking (SORT) is used to maintain multi-target identity consistency across frames. To address viewpoint shifts and vibration artifacts inherent to vehicle-mounted camera systems, a Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT)-based stabilization refinement strategy is employed, ensuring spatial alignment of tracked trajectories. Dynamic scene features are then extracted using a VGG19-based convolutional network, providing contextual semantics that are fused with the stabilized trajectories to enhance environmental awareness. For the prediction stage, the Social-LSTM paradigm is extended by embedding dynamic scene features into the interaction modeling process. This joint representation enables simultaneous learning of pedestrian behavioral patterns and environmental influences, thereby improving both the accuracy and robustness of future trajectory predictions.

3.2. Target Detection and Tracking

The detection and tracking module employs a detection-then-tracking framework, in which we apply YOLOv10 [

23] for pedestrian detection and use SORT [

24] for continuous multi-target tracking. We configure SORT with a maximum tracking age of 30 frames, a minimum confirmation threshold of 5 frames, and an Intersection-over-Union (IoU) threshold of

, enabling precise tracking in resource-constrained vehicle-mounted camera scenarios.

For each detected pedestrian, we initialize an independent Kalman filter-based tracker with a seven-dimensional state vector:

where

and

denote the bounding box center coordinates;

is the bounding box area; and

is the aspect ratio. The terms

represent the corresponding velocity components.

We formulate data association via an IoU-based cost matrix:

where

indicates the cost of assigning detection

to the predicted bounding box

. The IoU metric is computed as:

We adopt a two-stage matching procedure, where preliminary filtering based on the IoU threshold discards low-overlap pairs, followed by Hungarian assignment for optimal matching. Trajectory management follows an initialization–confirmation–termination scheme to maintain stable identities and suppress short-lived noise tracks.

Post-processing involves three refinement strategies:

Coordinate consistency restoration: We transform all detections back to the original image coordinate space and map them to a fixed-resolution reference frame, eliminating inconsistencies caused by preprocessing operations such as padding or cropping. This ensures that all trajectory segments share a uniform spatial reference.

Coordinate normalization: To remove resolution-dependent variations, we normalize all bounding box coordinates to the unit interval relative to the reference frame size. This produces a dimensionless representation, making data association thresholds invariant to image resolution.

Linear interpolation for missing frames: We mitigate short-term dropouts, caused by occlusion or missed detections, by interpolating the center positions and scales between two high-confidence bounding boxes. This is applied only when the temporal gap is below a predefined limit to prevent generating spurious trajectories.

3.3. SIFT-Based Trajectory Stabilization

In vehicle-mounted camera systems, we obtain raw pedestrian trajectories from object detection and tracking, and these trajectories often suffer from geometric distortions and jitter caused by camera ego-motion, detection noise, and viewpoint variations. To address these issues, we employ a global motion compensation strategy based on the SIFT [

25], which identifies stable background keypoints across the full image frame. Although we perform keypoint search in the entire frame, the majority of stable points are typically located in upper image regions, where static environmental structures—such as tree canopies, lamp posts, and building edges—are abundant. These stationary background features serve as geometric anchors for estimating and compensating camera-induced displacement in the image plane, thereby improving trajectory stability.

Given an input frame

, we first convert it to grayscale to improve feature detection robustness. We then extract SIFT keypoints and descriptors as:

where

denotes the number of detected keypoints.

We obtain temporal correspondence using pyramidal Lucas–Kanade Optical Flow(LK) [

26], propagating each

to frame

:

where

outputs the displacement vector

.

We discard keypoints with apparent motion above a fixed threshold

:

where

.

We match the remaining static keypoints frame-to-frame using the Fast Library for Approximate Nearest Neighbors (FLANN) [

27], approximating

k-nearest neighbor search in the SIFT descriptor space:

where

denotes the Euclidean norm in 128-dimensional descriptor space.

To reject ambiguous matches, we apply Lowe’s ratio test:

where

and

are the smallest and second-smallest Euclidean distances.

We use the matched static keypoints

and

to estimate the dominant inter-frame motion via a Random Sample Consensus (RANSAC) [

28]-based affine transformation:

We apply the inverse transformation to each pedestrian point

, defining the compensation offset:

where

controls compensation strength. The stabilized point is:

Finally, we apply a constant-velocity Kalman filter to each trajectory. The state vector for pedestrian

i at frame

t is

with prediction step:

where the transition matrix is

and

is the inter-frame interval. We update the state using the ego-motion–compensated observation

:

with observation matrix

We compute the Kalman gain in the standard form to minimize posterior covariance. The resulting stabilized trajectories preserve the original format while significantly reducing jitter and improving temporal coherence, thus providing a reliable foundation for downstream social interaction modeling and long-horizon prediction.

3.4. Scene Feature Extraction

To improve trajectory prediction accuracy, we incorporate a scene feature extraction module into the proposed model to capture dynamic scene features—high-level environmental semantics that characterize contextual constraints in vehicle-mounted camera scenarios. By embedding these features into the prediction pipeline, our model can jointly learn pedestrian motion patterns and environment-dependent behavioral cues.

We resize each region of interest (ROI), obtained from YOLOv10 pedestrian detections or scene-level cropping, to

pixels and normalize it via mean subtraction using ImageNet training-set statistics. This preprocessing ensures compatibility with the ImageNet-pretrained VGG19 [

29] architecture.

The hierarchical layers of VGG19 produce multi-level feature representations, ranging from low-level texture patterns to high-level semantic abstractions. In this work, we select the output of the final convolutional layer because it retains spatial context while providing semantically rich descriptors with acceptable computational cost. Let

denote the input scene image; we compute its feature representation as:

where

encodes abstract scene semantics, with

C,

H, and

W denoting the number of channels, height, and width of the feature map, respectively.

We integrate the extracted scene features with the stabilized pedestrian trajectories

from the trajectory stabilization module. We implement feature fusion as a channel-wise concatenation:

where

denotes concatenation along the feature channel dimension.

By explicitly modeling scene elements such as traffic signal states, crosswalk geometry, and neighboring vehicle movement, this module enables the network to capture critical environmental factors that influence pedestrian motion. The resulting fused representation provides a richer context for downstream social interaction modeling and long-horizon trajectory prediction in complex, real-world traffic conditions.

3.5. Pedestrian Interaction Modeling and Joint Trajectory Prediction

3.5.1. Pedestrian Interaction Modeling

As a core component of the proposed framework, the social pooling module implements the social interaction modeling mechanism, explicitly capturing inter-pedestrian influences in dynamic, multi-agent environments. By computing relative positions between a target pedestrian and neighboring pedestrians within a defined spatial range, and aggregating their corresponding latent representations, the module models the mutual influence of agents—a critical factor in complex traffic scenarios where social behavior significantly affects motion dynamics [

14,

30].

For a target pedestrian

i, we define the neighborhood set

as:

where

denotes the 2D position vector, and

R is the interaction radius controlling the spatial extent of influence.

We obtain the social context for pedestrian

i by aggregating the hidden states of all neighbors

generated by the LSTM encoder, where

denotes the

d-dimensional hidden representation of pedestrian

j:

We transform the pooled social feature

via a fully connected layer and nonlinearity:

where

and

are trainable parameters, and

denotes the element-wise activation function.

We concatenate the enhanced social feature with the hidden state of the target pedestrian and feed it into the subsequent LSTM layer for sequential trajectory decoding. This integration allows the model to adapt the effective interaction radius to varying pedestrian densities and spatial configurations, enabling the extraction of richer social behavior patterns.

3.5.2. Joint Scene–Trajectory Prediction

We adopt a joint prediction strategy in the proposed framework that simultaneously estimates future pedestrian trajectories and future dynamic scene features. This dual-branch design consists of a scene prediction branch that models the temporal evolution of the environment, and a trajectory prediction branch that integrates predicted scene features with social interaction features for improved motion forecasting.

In dynamic, vehicle-mounted camera scenarios, environmental changes—such as traffic signal transitions, moving vehicles, and pedestrian flow variations—can significantly influence human motion. To capture these evolving cues, we apply a recurrent neural architecture in the scene prediction branch to forecast the scene feature representation of a future time step before trajectory decoding.

Let

denote the scene feature map at time step

t extracted by the scene feature extraction module, and let

denote its prediction for time step

. We perform temporal modeling using a scene LSTM, which maintains a hidden state

and a cell state

. The LSTM gate operations are defined as:

where

is the sigmoid activation, ⊙ is the Hadamard product, and

and

are learnable parameters.

In compact form, the LSTM update becomes:

We obtain the predicted future scene representation via a projection layer:

where

denotes a fully connected transformation followed by a non-linear activation. The resulting

lies in the same embedding space as

, enabling direct fusion with other features in the trajectory prediction branch.

We then use

in the trajectory prediction branch, together with social interaction features

, to anticipate future pedestrian positions. Access to both current and anticipated environmental context improves robustness and accuracy in highly dynamic urban driving scenarios. Given the current position

of pedestrian

i, together with its historical trajectory and those of its neighbors, the social pooling mechanism outputs an aggregated interaction feature

. Simultaneously, we encode the motion history of pedestrian

i using a trajectory LSTM:

where

and

denote the hidden and cell states at time

t.

We form the multi-source context by concatenating

,

, and

:

where

denotes channel-wise concatenation.

We map the fused representation to the predicted displacement

:

and update the pedestrian position recursively:

By integrating scene dynamics through and interaction dynamics via , our predictor jointly captures agent–agent and agent–environment dependencies, resulting in accurate trajectory forecasts in complex, dynamic, vehicle-mounted camera scenarios.

3.6. Loss Function

We jointly optimize two task-specific objectives in the proposed dual-task framework, aimed at predicting both pedestrian trajectories and future dynamic scene features. This joint learning strategy improves overall prediction performance in complex vehicle-mounted camera scenarios [

31,

32]. We define the total loss as:

where

and

represent the trajectory prediction loss and scene feature prediction loss, respectively.

We represent each ground-truth pedestrian trajectory as a sequence

, where

denotes the

D-dimensional position (e.g.,

coordinates) of pedestrian

i at time

t, and we denote its prediction as

. The baseline objective is the mean squared error (MSE) over all pedestrians and time steps:

To promote diversity in multi-modal predictions, we extend the objective to:

where

K denotes the number of hypothesis trajectories,

denotes the confidence weight for the

k-th hypothesis,

controls diversity regularization, and

denotes the Manhattan distance. The first term enforces accuracy for each hypothesis; the second discourages redundant trajectories by penalizing high similarity. We then define the trajectory prediction loss as:

Let

denote the ground-truth scene feature map at time

t and

the predicted feature. We define the reconstruction loss as:

To encourage temporal coherence in predicted features, we incorporate a smoothness term:

We then compute the complete scene feature prediction loss as:

where

and

are balancing coefficients tuned on the validation set.

This joint objective enables us to optimize spatial–temporal consistency in dynamic scene representation and achieve an accuracy–diversity trade-off in trajectory forecasting, which is crucial for robustness in highly dynamic traffic environments.

4. Experiments and Evaluation

4.1. Dataset and Experimental Setup

Experiments are conducted on the Joint Attention for Autonomous Driving (JAAD) dataset [

33], a public benchmark comprising 346 short video clips captured in real-world traffic environments. The dataset covers diverse driving scenarios, including dense urban streets and complex intersections, with all footage recorded from vehicle-mounted cameras, thereby ensuring authentic dynamic perspectives.

For each video frame, YOLOv10 is used to detect and track pedestrians, producing raw position sequences. These tracked trajectories are processed through stabilization, coordinate restoration, and normalization to eliminate scale and alignment inconsistencies. Each input sequence contains observed trajectories over 8 time steps, with the prediction horizon set to the subsequent 12 steps, ensuring consistent temporal resolution across clips. Dynamic scene features are extracted from the corresponding frames using the pretrained VGG19 network, and then fused with stabilized pedestrian trajectories to form the complete model input. The dataset is split into training, validation, and testing subsets. The training set is used for parameter learning, the validation set for hyperparameter tuning and model selection, and the test set exclusively for generalization evaluation. All splits preserve the distribution of environmental contexts and pedestrian densities to prevent bias. Model optimization is performed using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with an initial learning rate of over 200 epochs. The learning rate remains fixed during training, and network parameters are updated to minimize the combined trajectory and scene prediction loss. The implementation follows a standardized training pipeline, with fixed random seeds and consistent preprocessing to ensure reproducibility. Evaluation metrics and results are reported in the following sections.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed model in pedestrian trajectory forecasting, we adopt widely used quantitative metrics that capture both short-term and long-term prediction accuracy in complex, dynamic vehicle-mounted camera scenarios. The primary metrics are ADE and FDE. Lower values in both metrics indicate higher predictive accuracy.

4.2.1. Average Displacement Error (ADE)

ADE measures the mean Euclidean distance between the predicted and ground-truth trajectories over the entire prediction horizon. For each time step

, the L2 norm of the positional error is computed and averaged across all

T steps:

where

and

denote the predicted and ground-truth positions at time

t, respectively, and

for

coordinates. Smaller ADE values reflect the proficiency of the model in maintaining high positional accuracy across multiple predicted steps.

4.2.2. Final Displacement Error (FDE)

FDE evaluates the positional error at the final prediction step, placing greater emphasis on long-term forecasting accuracy. It is defined as:

where

T is the last prediction time step. Lower FDE values indicate the capability of the model to precisely anticipate the endpoint of the trajectory, an aspect particularly important for decision-making in autonomous driving scenarios.

4.2.3. Collision Rate

The collision rate quantifies the proportion of predicted trajectories that intersect with other pedestrians or static obstacles, based on a spatial proximity threshold [

34]. Formally, a collision is counted at time step

t if the L2 distance between any two predicted pedestrians is below a predefined safety distance

. This metric is particularly important in crowded scenes, as it reflects the capability of the model to generate socially compliant and physically feasible multi-agent predictions.

4.2.4. Trajectory Smoothness

Trajectory smoothness evaluates the physical plausibility and naturalness of predicted motion by penalizing abrupt changes in velocity or acceleration [

35]. We assess smoothness through three complementary derivatives of the pedestrian position sequence

:

Velocity Smoothness:

where

represents the velocity vector at time

t. Lower values indicate more uniform motion.

Acceleration Smoothness:

where

is the acceleration vector. Smaller values correspond to smoother velocity changes.

Jerk Smoothness:

where

is the jerk vector. This term measures the stability of acceleration changes; lower values indicate more physically plausible motions.

These smoothness measures help ensure that predicted trajectories not only match the ground-truth positions (ADE/FDE) but are also kinematically realistic, which is essential for deployment in real-world autonomous navigation.

4.3. Trajectory Stabilization Visualization

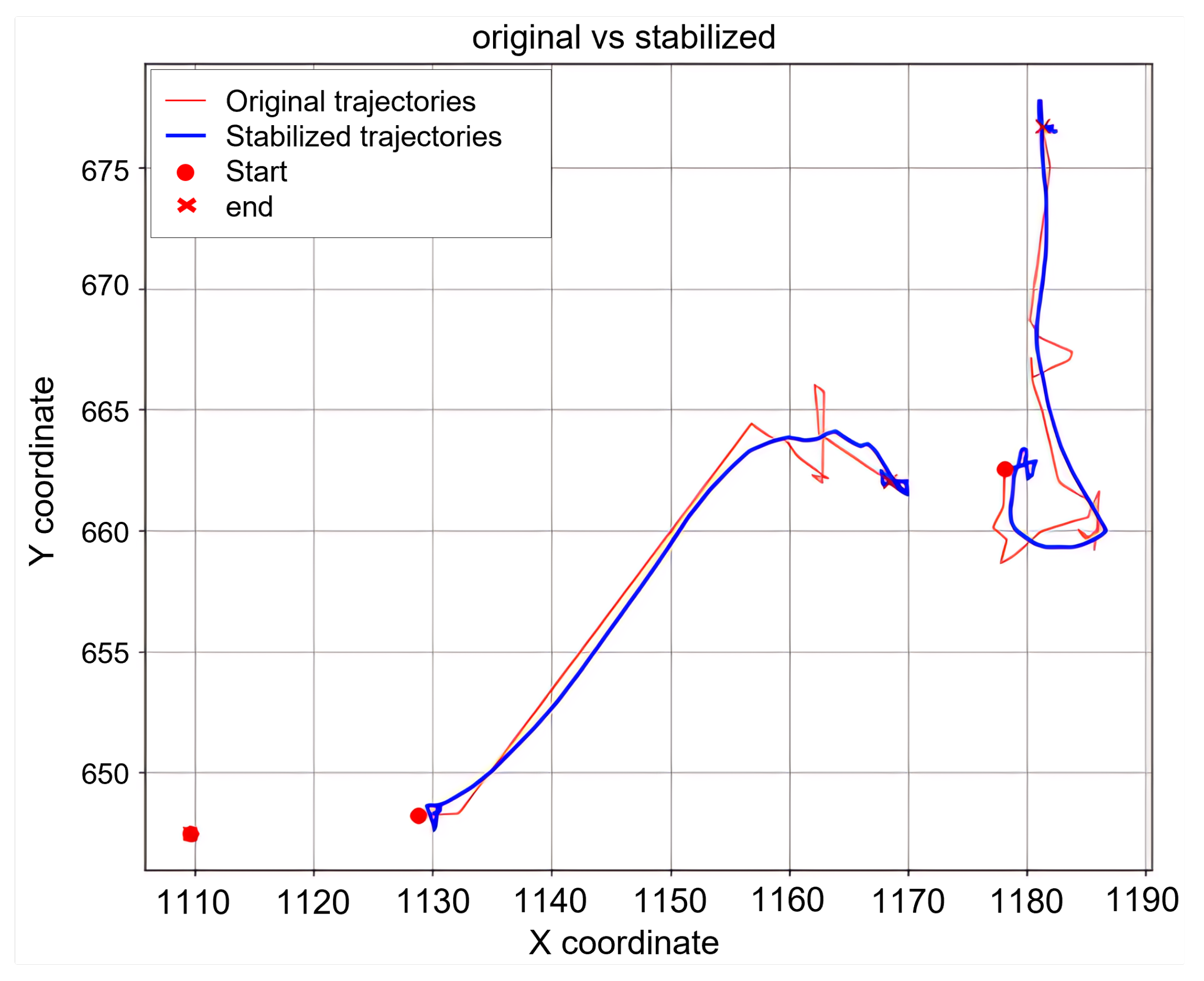

Figure 2 presents a qualitative comparison between raw and stabilized pedestrian trajectories. The original trajectory (red) exhibits noticeable high-frequency oscillations and abrupt jumps, which are significantly mitigated after SIFT-based stabilization (blue), yielding a temporally coherent path.

Figure 3 illustrates the matching of static background keypoints between adjacent frames. These matches serve as geometric anchors for estimating and compensating camera-induced displacements, thus directly enabling the trajectory smoothing effect shown in

Figure 2.

4.4. Comparative Experiments

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed V-PTP-IC framework—built upon Social-LSTM augmented with dynamic scene feature fusion—we conduct comparative experiments against representative pedestrian trajectory prediction baselines. All baseline models are trained and evaluated under identical experimental settings, using the same trajectory and scene feature preprocessing pipeline, dataset splits, and optimization parameters, ensuring fairness in comparison.

The baselines are as follows:

Standard LSTM: A fundamental Long Short-Term Memory network that independently models each pedestrian’s trajectory without incorporating social interactions or environmental context. Serves as a minimal baseline for sequential forecasting.

LSTM Encoder–Decoder: An architecture employing an LSTM-based encoder to capture historical trajectory features and an LSTM-based decoder to predict future positions. This model improves upon Standard LSTM in sequence handling but still lacks explicit interaction or scene modeling.

Social-LSTM: An extension of LSTM that incorporates a social pooling mechanism to model inter-pedestrian influences, thereby improving accuracy in multi-agent scenarios. This serves as a direct reference point for evaluating the impact of integrating dynamic scene features into social interaction modeling.

Transformer: A self-attention-based sequence model capable of capturing global temporal dependencies across trajectory sequences. Unlike recurrent architectures, it efficiently models relationships between any two time steps, showing strong performance in long-range motion forecasting tasks.

Table 1 reports the quantitative results on the JAAD test set, with comparisons conducted using ADE, FDE, and training time. These results provide both accuracy and efficiency perspectives for evaluating the benefits of the proposed framework.

4.5. Ablation Studies

We conduct ablation experiments to quantify the contribution of each core component in the proposed V-PTP-IC framework: the social pooling module, dynamic scene feature fusion, and SIFT-based trajectory stabilization. The goal is to separately evaluate the effect of removing or replacing each module and to investigate possible interactions between components.

4.5.1. Ablation on Model Components

Table 2 presents the quantitative results for various model configurations, comparing

,

, and trajectory smoothness scores. The “Benchmark Model" here denotes the base trajectory LSTM without any of the three components.

Table 3 further summarizes the relative

/

improvements (in %) over the benchmark model across different component configurations.

Results indicate several important trends: when applied in isolation, the social pooling module leads to a significant performance drop ( ADE, FDE), likely due to the introduction of noisy interaction cues in sparse or low-quality detection scenarios. By contrast, using only dynamic scene features yields moderate gains ( ADE, FDE), as scene-level environmental context improves the plausibility of motion forecasts. The SIFT-based stabilization module alone achieves a notable ADE gain () by compensating for ego-motion and detection-induced jitter, though its effect on long-horizon FDE is limited ().

Combining scene features with social pooling mitigates interaction noise and substantially boosts FDE performance ( ADE, FDE), indicating that environmental cues support more reliable interaction modeling. Pairing social pooling with stabilization ( ADE, FDE) suggests that stabilizing trajectories improves the extraction of social interaction patterns, though benefits are less pronounced in long-term predictions. Integrating scene features with stabilization achieves balanced improvements in both metrics ( ADE, FDE), enhancing the physical realism and smoothness of predicted paths.

The complete V-PTP-IC model, which unifies all three components, delivers the highest gains ( ADE, FDE), confirming that balanced fusion of dynamic scene understanding, social interaction modeling, and stabilization yields the optimal trade-off between accuracy, diversity, and trajectory smoothness.

4.5.2. Comparison of Scene Feature Backbones

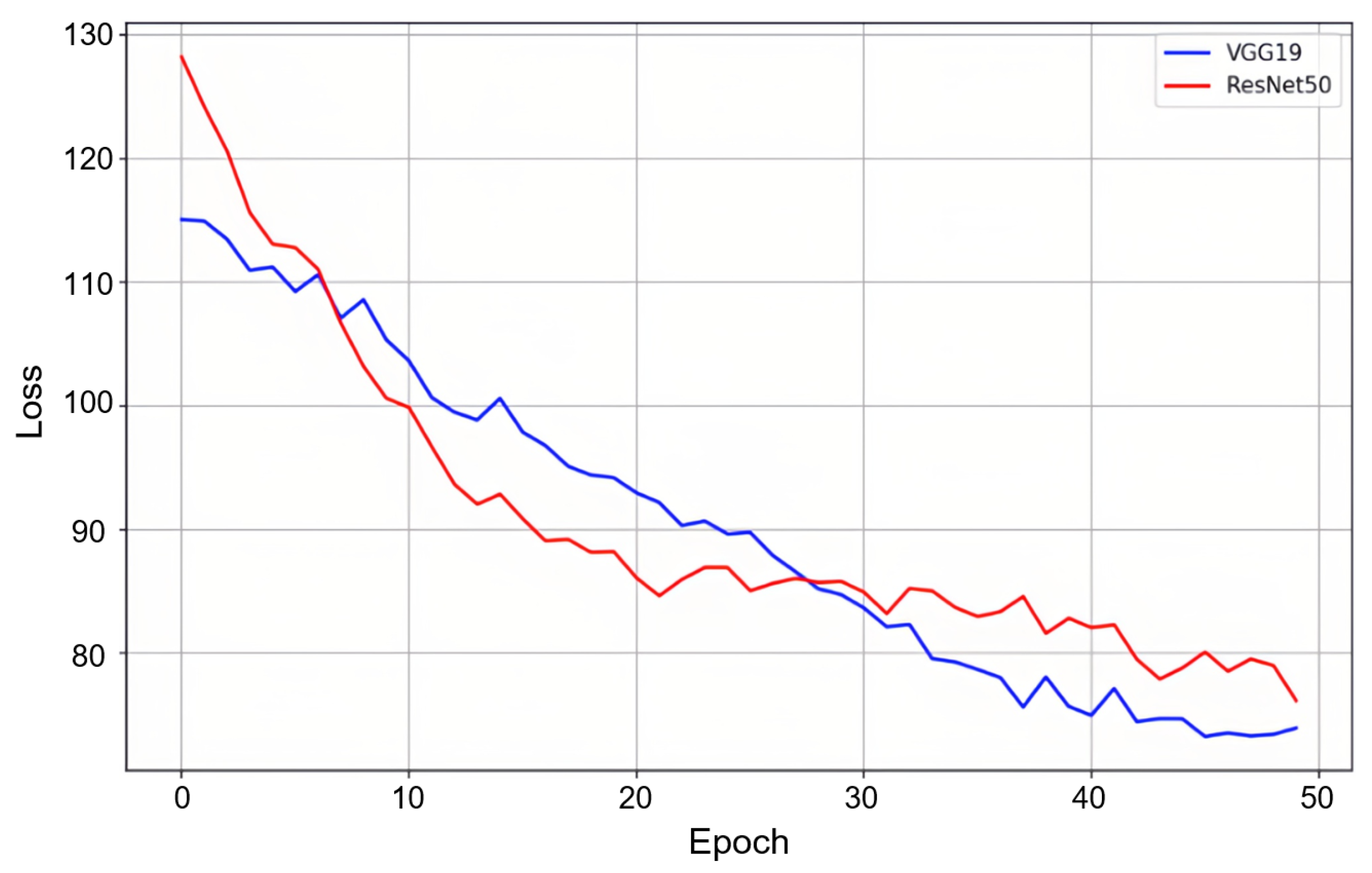

Given the critical role of scene features in V-PTP-IC, we further compare two popular CNN backbones: VGG19 and ResNet50, both pretrained on ImageNet.

Figure 4 shows the training loss comparisons.

We observe that although ResNet50 exhibits faster early-stage convergence, VGG19 achieves lower final validation loss. This may be attributed to the capability of VGG19 for capturing high-level semantic features of static structures (e.g., buildings, road layouts) that remain stable in dynamic driving scenes, leading to better generalization when data is limited.

4.5.3. Qualitative Visualization

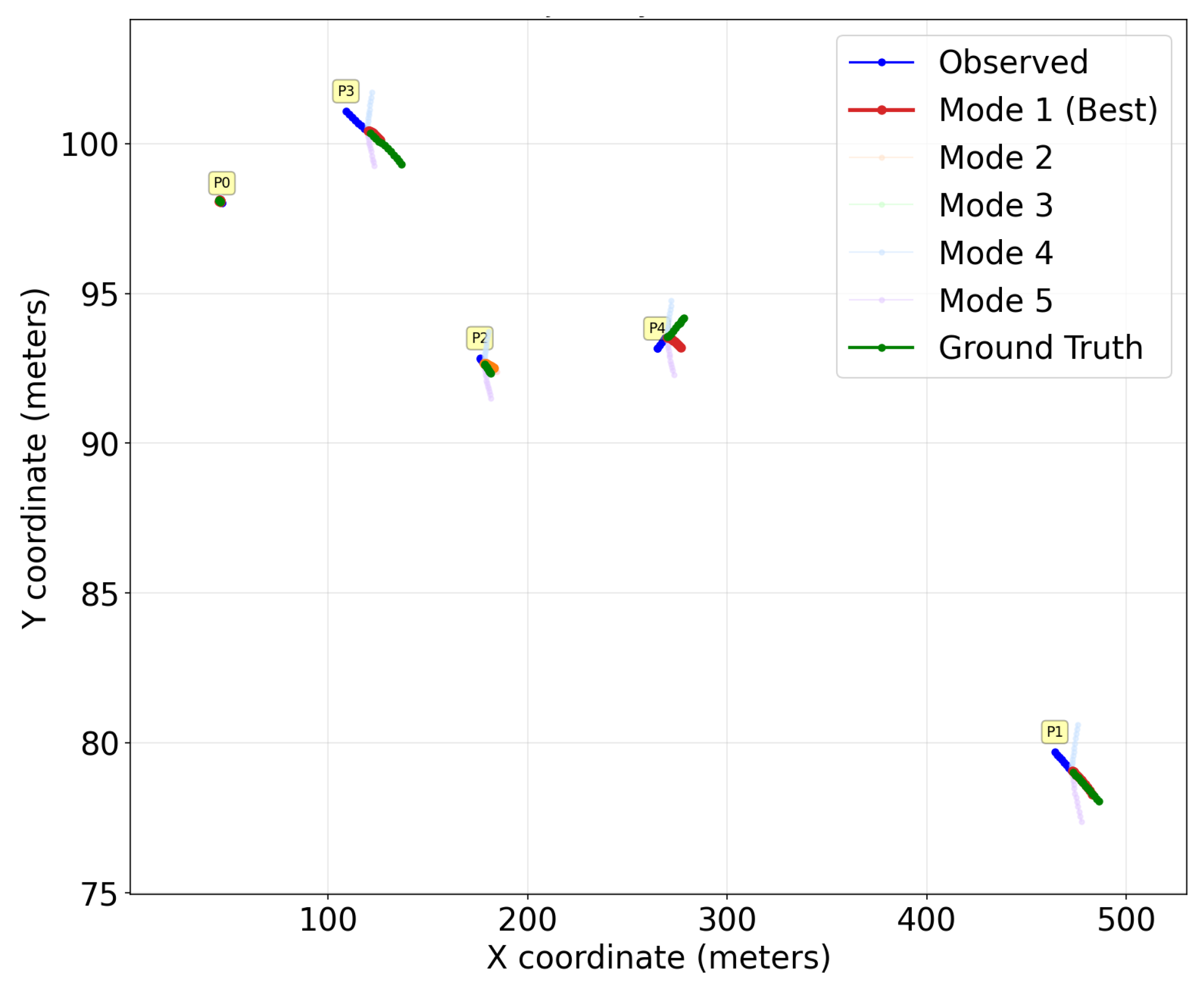

Figure 5 shows multi-modal trajectory prediction results from V-PTP-IC. Observed trajectories are in blue, the ground truth in green, the most probable predicted mode in red, and lighter curves represent alternative predicted modes. The main predicted mode (red) aligns with the ground truth (green), confirming accurate path forecasting. Alternative modes exhibit diverse yet reasonable variations that comply with scene constraints, reflecting the ability of the model to represent motion uncertainty.

These results are consistent with quantitative evaluations and verify that combining SIFT-based stabilization, VGG19-based scene features, and social interaction features leads to predictions that are both accurate and smooth. In particular, SIFT-based stabilization reduces jitter from ego-motion and detection noise; VGG19-based scene features provide rich contextual cues from the environment; and social interaction modeling captures pedestrian–pedestrian influence. Together, they produce trajectories that are precise, stable, and socially compliant in complex vehicle-mounted camera scenarios.

5. Conclusions

This paper has addressed the challenges of viewpoint dynamism, scene complexity, and spatiotemporal coupling in pedestrian trajectory prediction from vehicle-mounted camera perspectives through an end-to-end joint feature fusion framework. The proposed V-PTP-IC method integrates two components: a dynamic scene understanding module, including SIFT-based background keypoint matching for ego-motion compensation and trajectory stabilization together with VGG19-based scene feature extraction for capturing both static and dynamic environmental context; and a social interaction modeling module built upon a Social-LSTM network for learning spatiotemporal dependencies among pedestrians and producing socially compliant motion forecasts. By unifying these two modalities with a balanced feature fusion strategy, the framework fully leverages both dynamic scenes and pedestrian interactions to produce accurate and robust trajectory forecasts in complex driving scenarios. Experiments on the JAAD dataset demonstrate that V-PTP-IC achieves 22.2% and 25.8% improvements in ADE and FDE, respectively, over mainstream baselines, validating the effectiveness of the proposed joint modeling approach.

Future work will focus on enhancing real-time performance through lightweight architecture design, exploring advanced sequence modeling such as Transformers to capture long-range spatiotemporal dependencies in both scene and interaction domains, and extending the framework to more diverse real-world driving conditions—including adverse weather and challenging illumination—to further improve generalization and practical applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Bai Siqi and Fang Yuwei; methodology, Bai Siqi and Fang Yuwei; software, Fang Yuwei; validation, Bai Siqi and Fang Yuwei; formal analysis, Bai Siqi; investigation, Bai Siqi; resources, Li Hongbing; data curation, Fang Yuwei; writing—original draft preparation, Fang Yuwei; writing—review and editing, Bai Siqi; visualization, Fang Yuwei; supervision, Li Hongbing; project administration, Li Hongbing; funding acquisition, Li Hongbing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Open Fund of Sichuan Oil and Gas Development Research Center (Grant No. 2025SY011) and the Tuojiang River Basin High-quality Development Research Center (Grant No. TJGZL2025-12). The APC was not funded by any external organization.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in the JAAD (Joint Attention in Autonomous Driving) dataset at

https://github.com/ykotseruba/JAAD. The dataset includes video sequences and annotations for pedestrian behavior analysis in autonomous driving scenarios.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Air Quality Guidelines for Europe. WHO 2020, 91.

- Sighencea, B.I.; Stanciu, R.I.; Căleanu, C.D. A Review of Deep Learning-Based Methods for Pedestrian Trajectory Prediction. Sensors 2021, 21, 7543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laugier, C.; Paromtchik, I.E.; Perrollaz, M.; Yong, M.; Yoder, J.-D.; Tay, C.; Mekhnacha, K.; Nègre, A. Probabilistic Analysis of Dynamic Scenes and Collision Risks Assessment to Improve Driving Safety. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2011, 3, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridel, D.; Rehder, E.; Lauer, M.; Stiller, C.; Wolf, D. A Literature Review on the Prediction of Pedestrian Behavior in Urban Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 3105–3112. [Google Scholar]

- Gulzar, M.; Muhammad, Y.; Muhammad, N. A Survey on Motion Prediction of Pedestrians and Vehicles for Autonomous Driving. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 137957–137969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, T.; Pandey, A.K.; Alami, R.; Kirsch, A. Human-aware Robot Navigation: A Survey. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 1726–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Johora, F.T.; Sester, M.; Müller, J.P. Trajectory Modelling in Shared Spaces: Expert-based vs. Deep Learning Approach? In International Workshop on Multi-Agent Systems and Agent-Based Simulation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bighashdel, A.; Dubbelman, G. A Survey on Path Prediction Techniques for Vulnerable Road Users: From Traditional to Deep-Learning Approaches. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 1039–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Bellman, R. A Markovian Decision Process. J. Math. Mech. 1957, 6, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D.; Molnar, P. Social Force Model for Pedestrian Dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 1995, 51, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Althoff, M.; Mergel, A. Comparison of Markov Chain Abstraction and Monte Carlo Simulation for the Safety Assessment of Autonomous Cars. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2011, 12, 1237–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.E. Gaussian Processes in Machine Learning. In Summer School on Machine Learning; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003; pp. 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Mandalia, H.M.; Salvucci, M.D.D. Using Support Vector Machines for Lane-Change Detection. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Orlando, FL, USA, 26–30 September 2005; Volume 49, pp. 1965–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Alahi, A.; Goel, K.; Ramanathan, V.; Robicquet, A.; Fei-Fei, L.; Savarese, S. Social LSTM: Human Trajectory Prediction in Crowded Spaces. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 961–971. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Sun, P.; Hong, R.; Fu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, M. SocialGCN: An Efficient Graph Convolutional Network Based Model for Social Recommendation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.02815. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yao, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Sammut, C. Social Graph Transformer Networks for Pedestrian Trajectory Prediction in Complex Social Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Atlanta, GA, USA,, 17–21 October 2022; pp. 1339–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghian, A.; Kosaraju, V.; Sadeghian, A.; Hirose, N.; Rezatofighi, H.; Savarese, S. Sophie: An Attentive GAN for Predicting Paths Compliant to Social and Physical Constraints. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 1349–1358. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.; Qian, K.; Elhoseiny, M.; Claudel, C. Social-STGCNN: A Social Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Neural Network for Human Trajectory Prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 14424–14432. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Qian, D.; Ren, D.; Xia, H. StarNet: Pedestrian Trajectory Prediction Using Deep Neural Network in Star Topology. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Macau, China, 3–8 November 2019; pp. 8075–8080. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, F.M.; Sammarco, M.; Costa, L.H.M.K.; Detyniecki, M. Vehicle Telematics Via Exteroceptive Sensors: A Survey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.12632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, S.; Watta, P.; Murphey, Y.L. Pedestrian Re-identification Using a Surround-View Fisheye Camera System. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, Shenzhen, China, 18–22 July 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Westny, T.; Olofsson, B.; Frisk, E. Diffusion-based Environment-aware Trajectory Prediction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.11643. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J. YOLOv10: Real-time End-to-end Object Detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

- Bewley, A.; Ge, Z.; Ott, L.; Ramos, F.; Upcroft, B. Simple Online and Realtime Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; pp. 3464–3468. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive Image Features from Scale-Invariant Keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, X. Moving Target Detection and Tracking Based on Pyramid Lucas-Kanade Optical Flow. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Image, Vision and Computing, Chongqing, China, 27–29 June 2018; pp. 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara, S.; Draper, B.A. Are You Using the Right Approximate Nearest Neighbor Algorithm? In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Workshop on Applications of Computer Vision, Clearwater Beach, FL, USA, 15–17 January 2013; pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Strandmark, P.; Gu, I.Y.H. Joint Random Sample Consensus and Multiple Motion Models for Robust Video Tracking. In Scandinavian Conference on Image Analysis; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 450–459. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Deo, N.; Trivedi, M.M. Convolutional Social Pooling for Vehicle Trajectory Prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 1468–1476. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M.; Nasrabadi, N.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Novo, A.S.; Krüger, M.; Stolpe, M.; Bertram, T. A Review on Scene Prediction for Automated Driving. Physics 2022, 4, 132–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotseruba, I.; Rasouli, A.; Tsotsos, J.K. Joint Attention in Autonomous Driving (JAAD). arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.04741. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Lin, X.; Pan, D.; Li, Y.; Su, L.; Thomson, R.; Mizuno, K. Pedestrian Trajectory Prediction Method Based on the Social-LSTM Model for Vehicle Collision. Transp. Saf. Environ. 2024, 6, tdad044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Melendez-Calderon, A.; Roby-Brami, A.; Burdet, E. On the Analysis of Movement Smoothness. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2015, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).