1. Introduction

The HER2 receptor is a 185 kDa membrane-associated protein with tyrosine kinase activity and extensive homology to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). It is involved in tumour cell proliferation, adhesion, apoptosis, differentiation, angiogenesis, and migration. Its deregulation, increased expression or mutation is associated with neoplastic process [

1,

2]. This promotes dimerization, which activates signalling pathways, triggering a specific cellular response through cell signalling cascades [

3]. Increased HER2 expression correlates with an unfavourable prognosis in solid tumours, and it is widely used as a molecular marker [

4]. Studies in several types of human neoplasia have shown HER2 overexpression in 38% of gastric carcinomas, 20-30% of breast cancer, 20% of cervical cancer, 15% of ovarian cancer, and 18% of colorectal cancer [

5,

6,

7]. In fact, in breast cancer, where membrane HER2 is used as a therapeutic target, it was observed in HER2-negative tumours that HER2 was located in the nucleus, being highly oncogenic and generating resistance to treatments [

8]. Regarding renal cell carcinoma (RCC), the histological subtype clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is predominant. On the other hand, RCC exhibits hyperactivated angiogenesis related to the VHL and BAP-1 genes. Loss or mutation of the VHL gene is known to directly cause accumulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) and indirectly, to cause overexpression of the erythropoietin receptor gene, even in a tissue environment with normal oxygen levels [

9,

10,

11]. Of epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptors, EGFR is known to be present in RCC; however, the expression of HER2 remains unclear [

5,

9,

12,

13].

Although tumour stage is the main prognostic factor of ccRCC due to the absence of a molecular marker, the Fuhrman nuclear classification (FNG) helps guide patient management, whether therapeutic or follow-up [

14,

15]

.

This classification system, based on the histological analysis of cell nuclear abnormalities, has a high clinical predictive value in RCC and stratifies the tumour into four Fuhrman grades (FNG 1-4), which correlate with survival, recurrence and the probability of metastasis, with FNG-4 having the worst prognosis [

16].

For these reasons, we hypothesize that the HER2 receptor may be involved in kidney cancer progression and resistance. The objective of our study is to evaluate whether HER2 could be a molecular marker for kidney cancer by analysing HER2 expression and its relationship with prognostic factors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Samples

During the period 2018-2024, a retrospective study was carried out on 110 samples of renal epithelial tumours, normal (without tumor) and oncocytoma (benign tumour) and RCC, fixed in formalin and included in paraffin, from the Pathological Anatomy Service of the JR Vidal Hospital and the José de San Martín Teaching Hospital in the province of Corrientes, Argentina. Cases with necrosis above 30%, hemorrhage, insufficient sample size, or missing data were excluded. In addition, epidemiological, clinical, and pathological information was collected using a form. Informed consent was obtained in all cases in accordance with Law 25326 on Personal Data Protection. The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the JR Vidal Hospital and the José de San Martín Teaching Hospital (Resolution No. 9/15).

2.2. Immunohistolabeling

Two-micron sections were cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. After deparaffinization and hydration with xylene and alcohols of decreasing gradient, antigen exposure was performed with proteinase K (Bioamerica PKB4100) pH 8 (10 µg/ml). Incubated overnight with ErbB-2 (HER2) 3B5 antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# MA5-13675, RRID:AB _10985617), c-erbB-2 oncoprotein antibody (Agilent DAKO Cat# A0485, RRID:AB_2335701) and HIF1 alpha (C-19) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Cat# sc-8711, RRID:AB_2116993), EPAS-1 (190b) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Cat# sc-13596, RRID:AB_627525).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC). The sample was then incubated with anti-mouse/anti-rabbit and streptavidin (Vectastain

® Elite

® ABC Universal Kit PK-7200). The sample was developed with DAB (substrate kit, cell label 957D-20) and counterstained with hematoxylin (GILL II Biopack solution 9491.07).

Inmunohistofluorescence (IHF). Subsequently, it was incubated with the recombinant rabbit anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor™ Plus 488 (green). (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Cat# sc-13596, RRID:AB_627525) and the assembly was performed with proLong™ gold antifade assembly with DAPI (p36941) DNA stain (blue). A breast cancer sample was used as a HER2-positive control. A negative control (not containing the primary antibody) was used in each experiment. Immunostaining was assessed by independent observers blinded to clinicopathological variables, and the kappa index was 0.616, which was considered good agreement. Differences of opinion were resolved by joint reading. Each slide was carefully examined under a light microscope at 400x magnification in the area of the tumor containing the highest proportion of positive stained cancer cells, and a minimum of 100 cells per sample was counted. For quantification, a scoring system taken from the American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) for membrane HER2 in breast cancer was previously used [

17], and for the detection of HER2 in the cell nucleus the scoring system by Schillaci et al. [

18] was used.

2.3. Data Analysis

The collected clinical and epidemiological data was statistically analysed using Graphpad Prism 6 and SSPS software. Correlation between variables was performed using the chi square test and a value of p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Office Excell program was used for graphics design.

3. Results

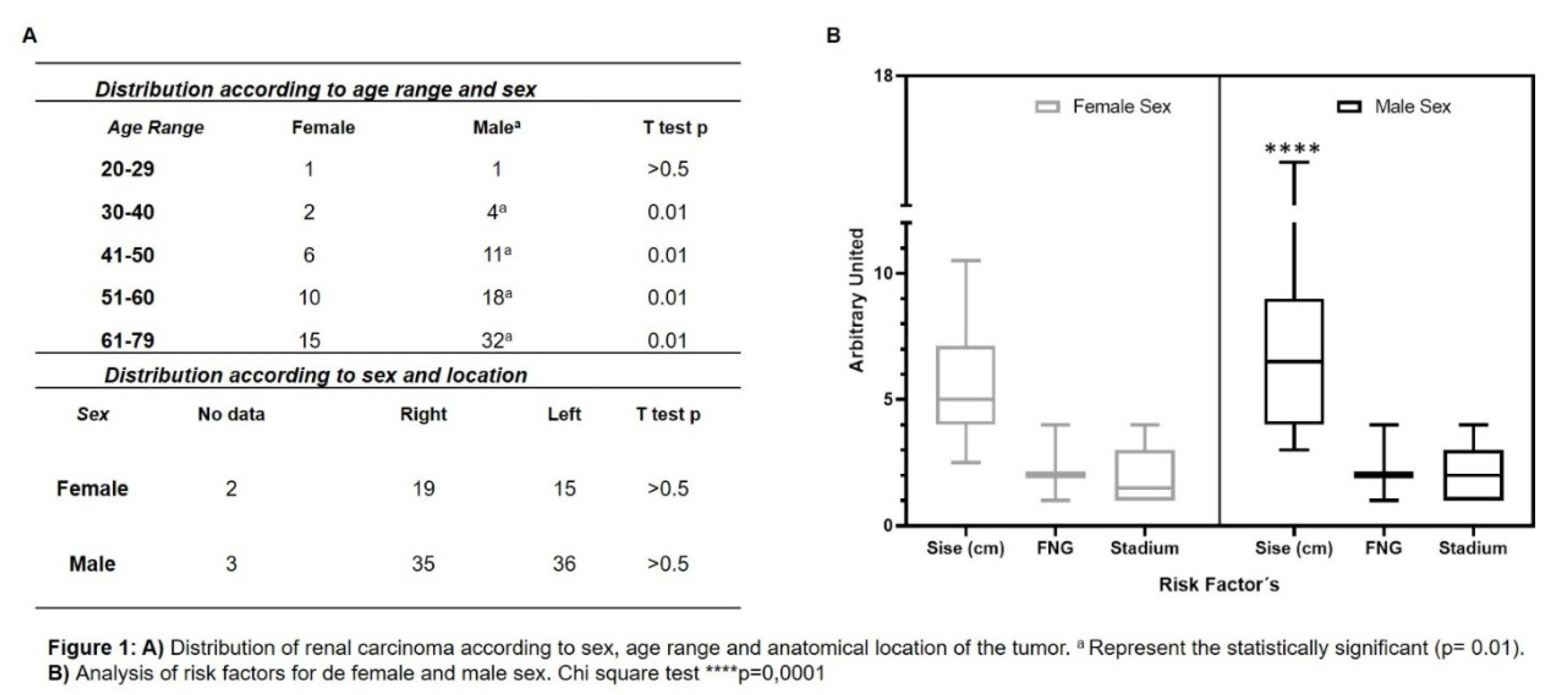

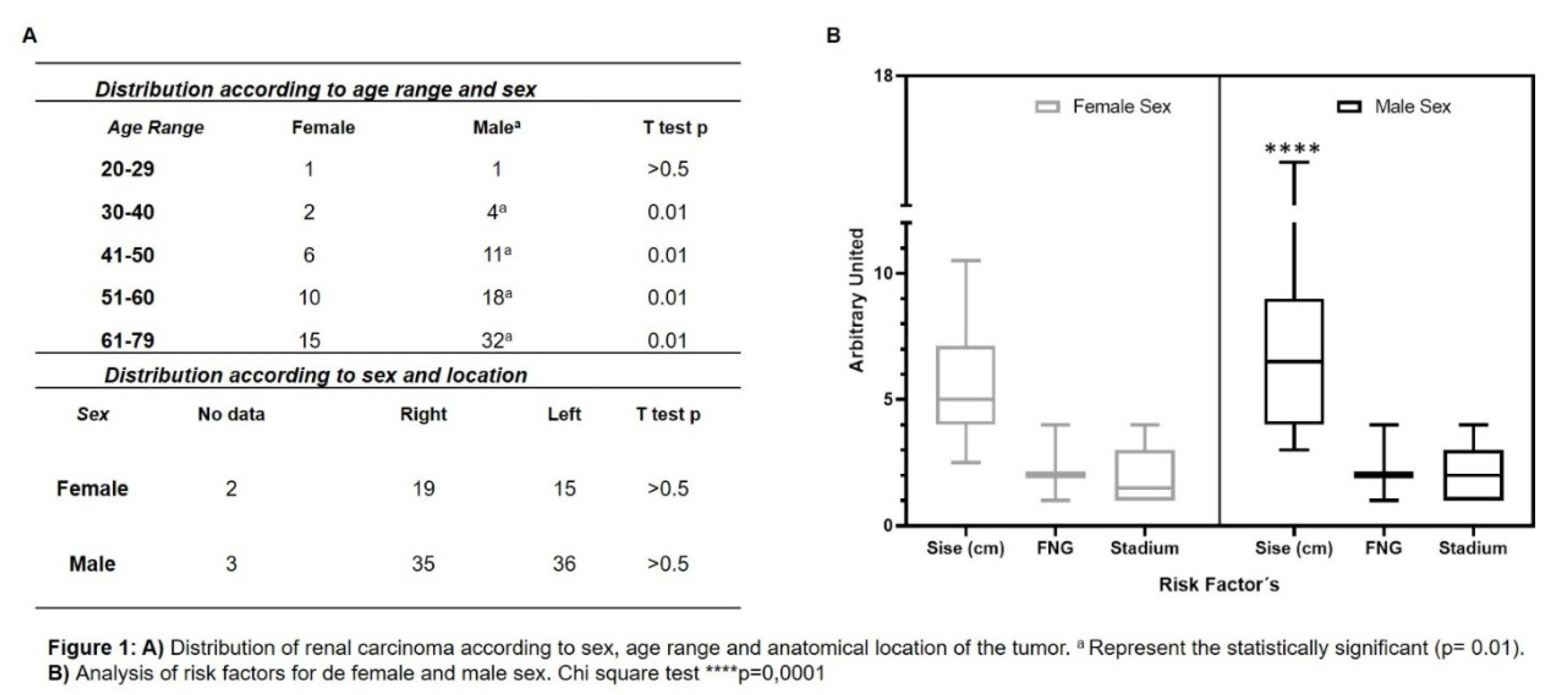

Distribution of renal cancer in our population was studied. Figure 1A shows a significant difference in gender, with renal cancer being more frequent in men than in women. Cases increase starting in the 30- to 40-year age range, with a peak frequency in the 51- to 60- and 61- to 79-year age groups. Regarding tumour location, distributed by sex, it was observed that both female and male populations present renal carcinoma in both kidneys.

We analysed poor prognostic factors associated with RCC based on sex, such as tumour size, FNG, and clinical stage. Figure 1B shows the analysis of risk factors for female and male subgroups. Significant differences were observed in relation to tumour size; men showed a higher mean. No significant differences were observed for FNG parameters and clinical stage. Next, the presence of HER2 was analysed in RCC samples of different histological types compared to normal kidney and benign tumour.

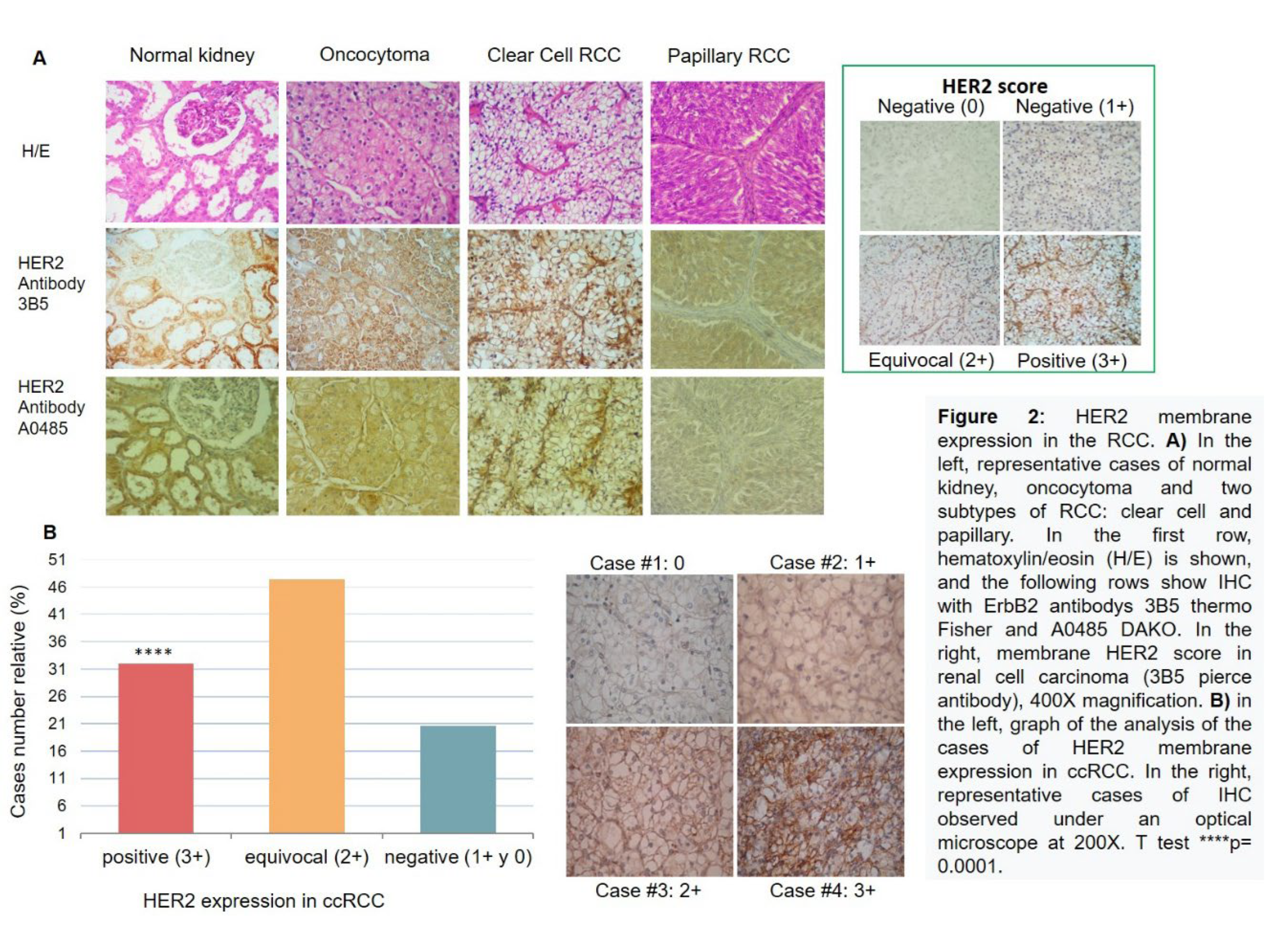

In Figure 2A on the left, HER2 is shown to be specifically present in the clear cell subtype, confirmed by two types of antibodies. To quantify this, a scoring system for membrane HER2 in ccRCC, taken from the American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP), was previously used (Figure 2A right). HER2 frequency was analysed in 97 ccRCC cases. Figure 2B on the left, shows membranous HER2 expression, with a distribution of 32% (31 cases) HER2 positive (3+), 47% (46 cases) equivocal (2+), and 21% (20 cases) negative (1+ and 0).

The distribution of cases between positive and negative groups was significant (p = 0.0001 for both groups) compared to the negative cases. For diagnostic purposes, equivocal cases (2+) should be confirmed by FISH. Figure 2B on the right shows the IHC microscopy of four representative cases. We also observed HER2 expression at the nuclear level.

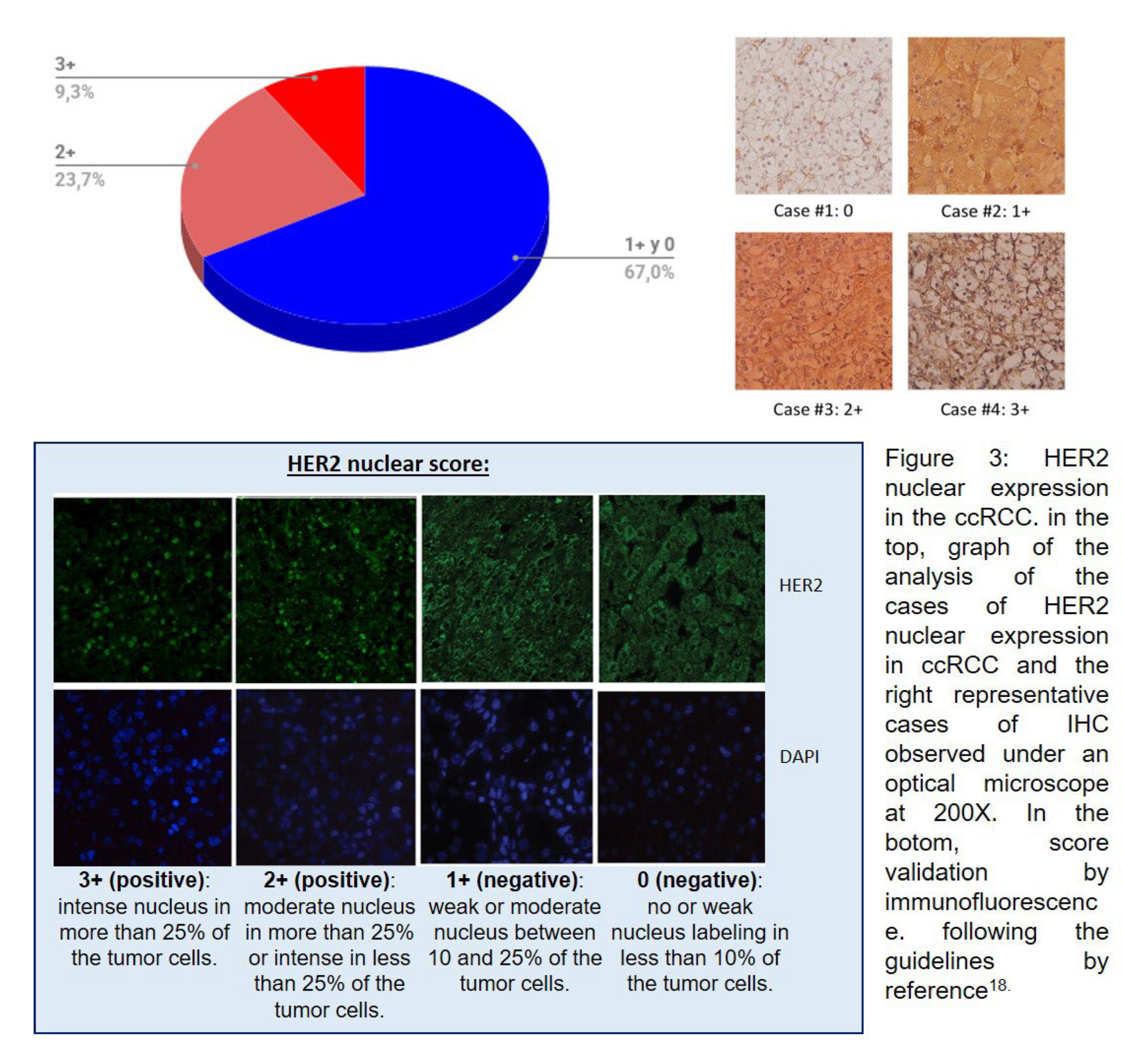

In Figure 3 (above), our results show a nuclear HER2 expression of 33% (intense expression 3+ (9.3%), moderate 2+ (23.7%), and negative 1+/0 (67%)). The immunofluorescence scoring is shown in Figure 3 (below).

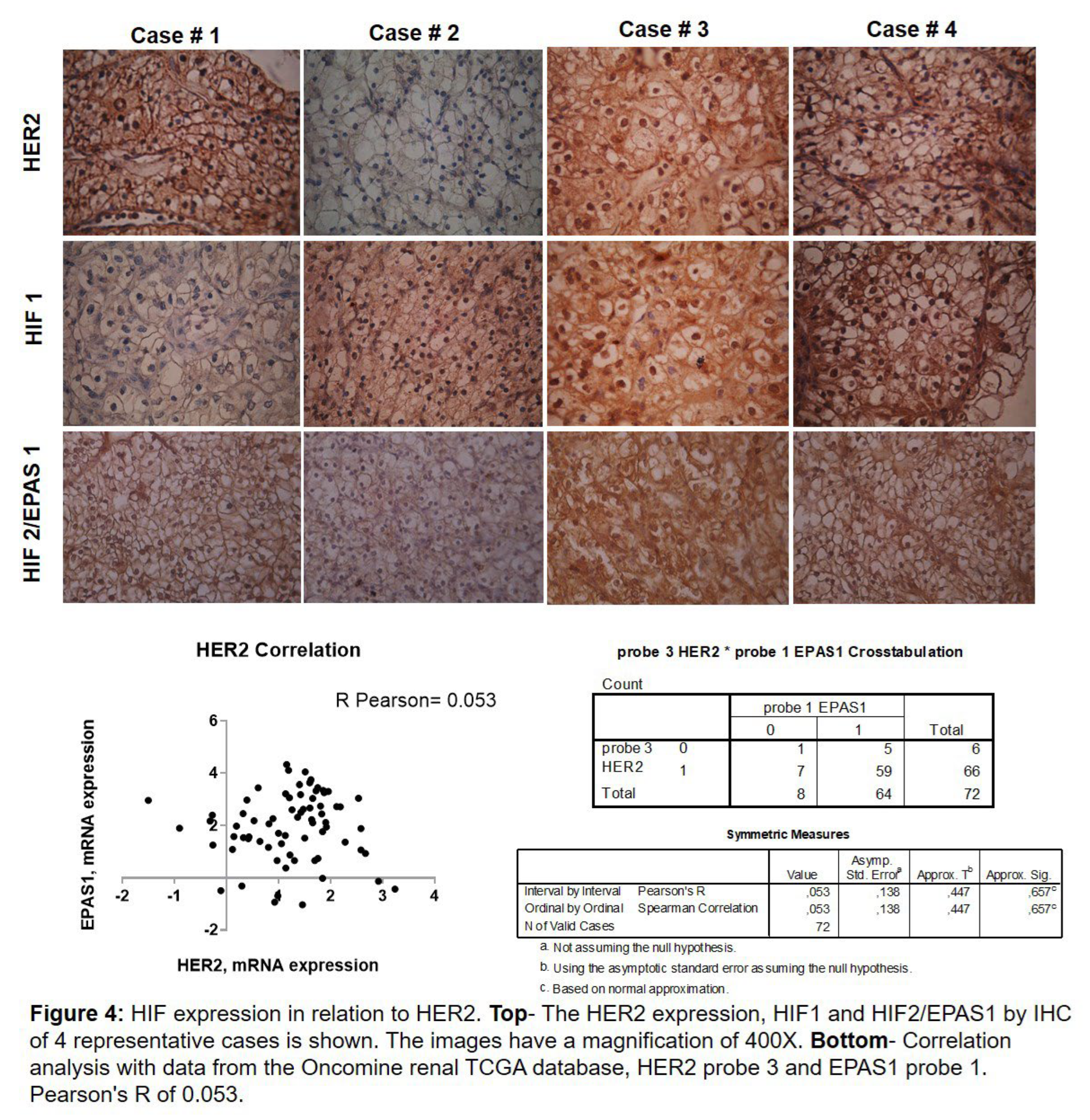

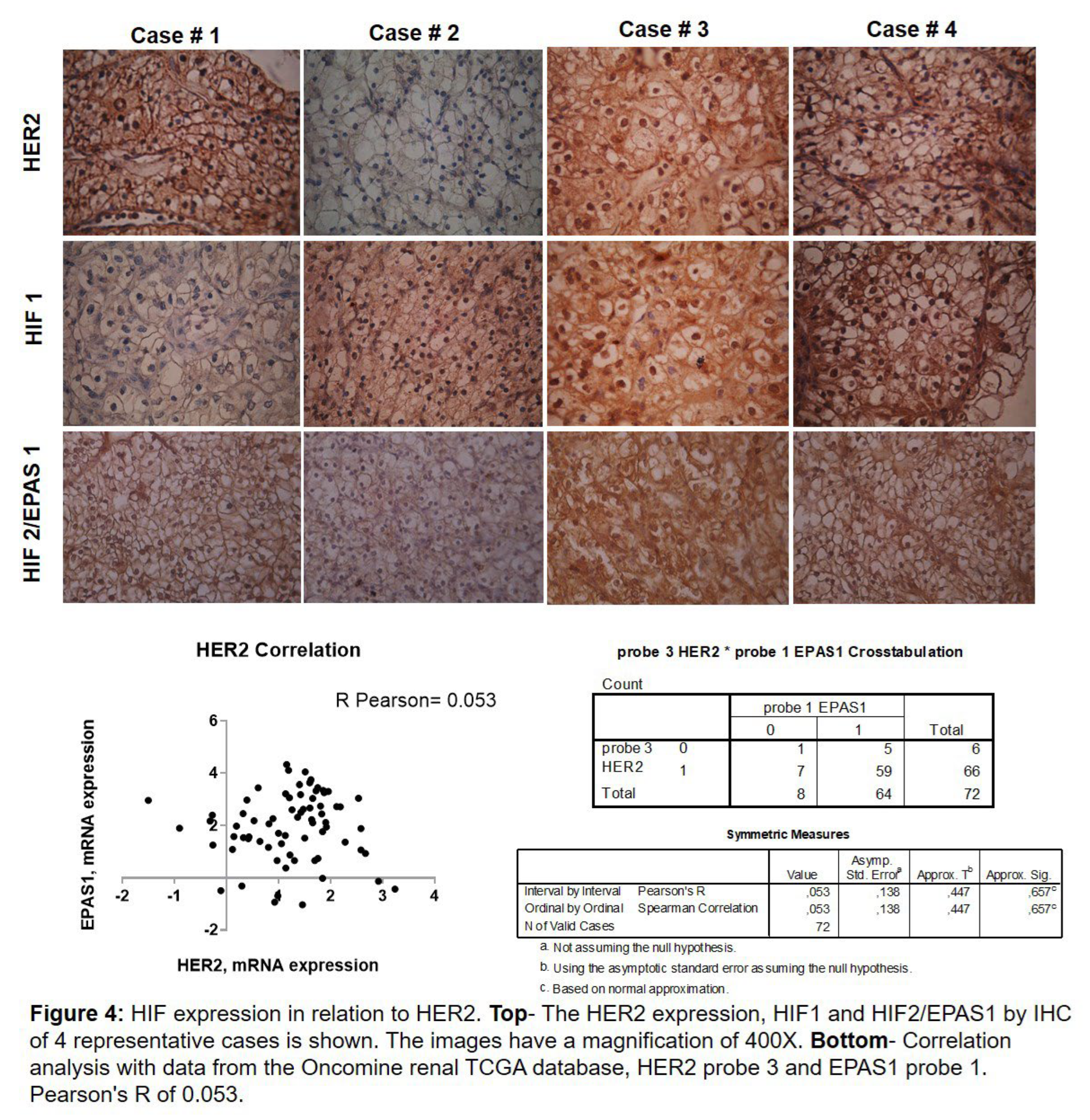

With these results, we analysed whether HER2 was related to HIF due to the absence of VHL. Figure 4 above shows that when HER2 is present in the membrane/nucleus, HIF1 is expressed in the nucleus (cases 3 and 4). But this relationship does not always occur since we also have cases that are positive for HER2 and negative for HIF1 (case 1) and vice versa (case 2). Regarding the relationship between HER2 and HIF2, it is different. We observed that HER2 is expressed in the membrane/nucleus and HIF2 in the nucleus (cases 1, 3, and 4), and when HER2 is negative, HIF2 has low expression 1+ or negative (case 2). Next, we analysed the relationship of HER2 genes with HIF2 in the TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) Kidney’s ONCOMINE [

19] database.

In Figure 4 below, the correlation of HER2 mRNA expression (probes 1, 2, 3, and 4) with HIF2 (probe 1) is shown. Analysis of all HER2 probes versus HIF1 yielded similar results. Considering that if Pearson’s R is between 0 and 1 (0 < r > 1), the correlation is positive. Our analysis yielded a positive Pearson’s R of 0.053.

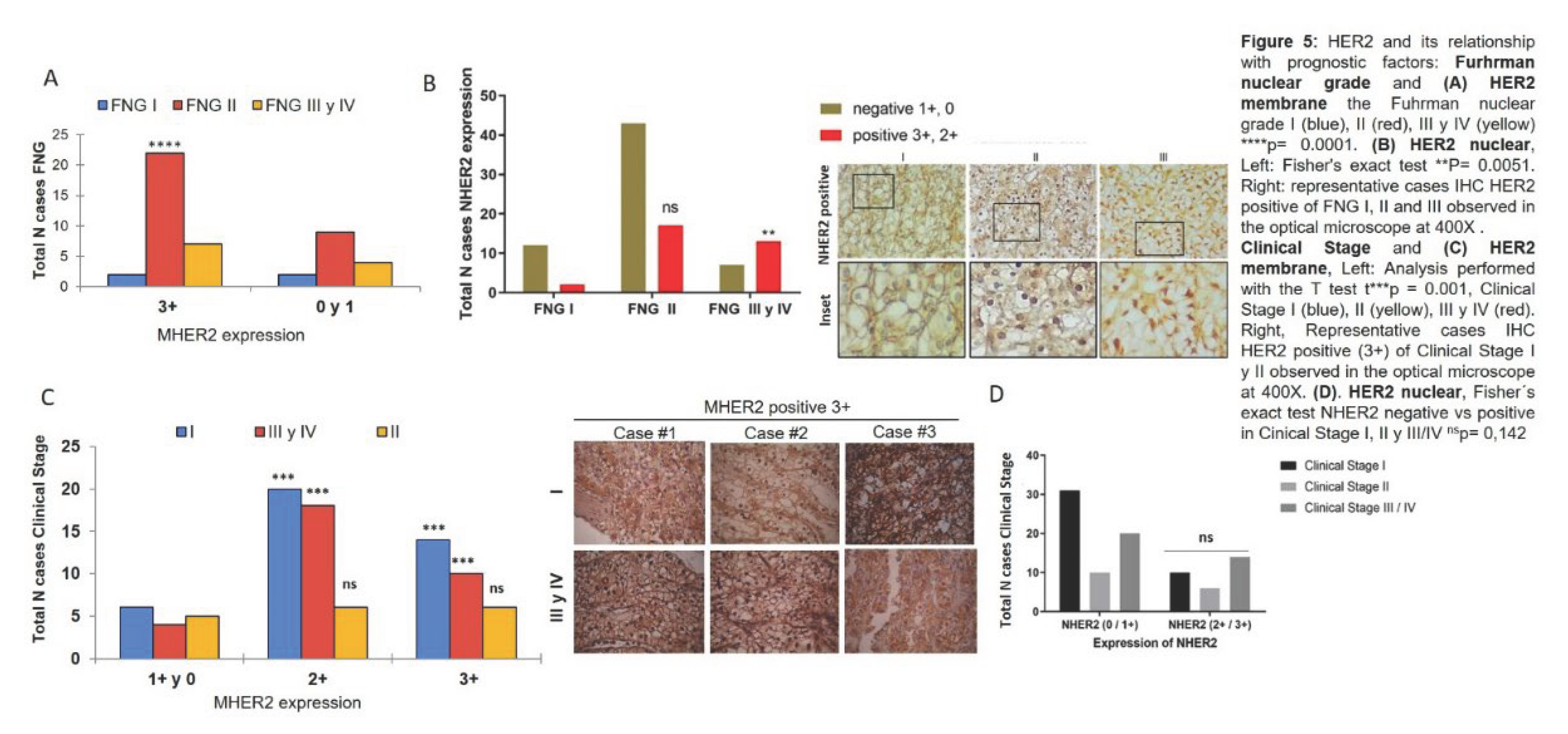

It was also studied whether HER2 was associated with poor prognostic factors in ccRCC. The relationship between HER2 and FNG was studied and it was observed that membranous HER2 expression was associated with nuclear grade II (Figure 5A) and nuclear HER2 expression relates to nuclear grades III and IV (Figure 5B). The involvement of HER2 in the patient’s clinical stage was assessed and was observed that membranous HER2 was expressed in low (I) and high (III and IV) clinical stages and not in intermediate (II) clinical stages (Figure 5C). However, when analysing nuclear HER2, there were no significant differences between negative and positive cases with respect to clinical stage (Figure 5D).

4. Discussion

We found that RCC was distributed in our cohort, with a higher frequency and larger in size in male population than the opposite sex. In our study, we observed that an increase in size can be associated with a poor prognosis only in the male population. The other analysed factors showed no differences. The frequency and larger size in men in our population are comparable with the literature which indicates a higher mortality rate from RCC in menfdagh [

20,

21].

In the search for oncological markers to guide therapy for renal cancer, we found that HER2 is present in the membrane of the ccRCC subtype specifically, in 32% (3+). In contrast to our results, there are studies that do not confirm an overexpression of HER2 in ccRCC [

22], but another study, did find that HER2 overexpression in the membrane is present in this subtype of cancer [

12]. However, there are publications that support our results, Phuoc, et al. [

23], found high levels of HER2 by immunohistochemistry although they did not relate it to survival. Nagasawa, et al. [

24], found that the growth of xenograft tumours with renal cell carcinoma decreases until they disappear using a HER2 inhibitor.

We believe this difference is due to the fact that the HER2 oncoprotein may accumulate in the membrane and does not increase with gene amplification in ccRCC. For this reason, elevated levels of HER2 protein are observed by immunohistochemistry [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23] or Western blotting [

24], but not by PCR [

22]. We also observed HER2 expression in the nucleus in 33% of cases, which is interesting since nuclear localization in renal cancer has still not been studied. This is consistent with published data on highly aggressive triple-negative breast cancer, where HER2 localizes in the nucleus, activating gene transcription [

18].

It has also been reported that in gastric cancer, HER2 activity in the nucleus generates resistance to treatments [

25]. We believe that in renal cancer it could act as a transcription factor, thus promoting the progression of the disease. The high frequency of HER2 in the ccRCC histological type is partly due to its association with HIF2, which was verified by TCGA analysis at ONCOMINE. Regarding the implication of HER2 as a poor prognostic factor, membranous HER2 expression was associated with Fuhrman nuclear grade (FNG) II, whereas nuclear HER2 was associated with nuclear grades III and IV. It is worth mentioning that no previous studies address this topic. We speculate that nuclear localization of HER2 may be promoting the nuclear dedifferentiation observed in cases with a high Fuhrman grade, indicating a poor prognosis. This is consistent with recent work in breast cancer indicating that nuclear localization is associated with a poor prognosis [

25]. When correlating membranous HER2 expression with clinical stage, we observed that it is expressed in low (I) and high (III and IV) clinical stages, but not in intermediate (II) clinical stages. HER2 may be promoting the progression of ccRCC by different mechanisms in clinical stage I and in clinical stages III and IV. We believe that finding membranous HER2 expression in high stages, and nuclear HER2 in high FNG, indicates that HER2 could be, on one hand, a therapeutic target, and, on the other hand, serve as a marker of poor prognosis with its nuclear localization [

26].

There are no studies that relate HER2 with clinical stage; despite this, it has been described for endovascular growth factor (VEGF), which is related to Fuhrman nuclear grade [

27]. The HER2 expression found in the studied population is of interest in ccRCC because it might be involved in nuclear differentiation mechanisms. However, at some point, this nuclear differentiation is driven by another mechanism at the expense of HER2, which would explain the differences in the patient’s clinical stage. This work contributes to the search for therapeutic targets for this pathology, as well as to the understanding of molecular mechanisms of the HER2 oncogene.

5. Conclusion

We conclude that, RCC is more common in the male population and is larger in size, with presence in the cell membrane and nucleus in the ccRCC subtype. Membranous HER2 expression is associated with EPAS1/HIF2. Nuclear HER2 expression favours FNG (III and IV). Membranous HER2 expression is present in clinical stages (I) and (III).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the collaboration of: The CIN-UNNE research fellows, Juan Jose Diaz, Sofia Meza, Ayelen Hermoso, Guido Avalos, Antonella Avalos and J. Francisco Franceschi for collecting samples and performing IHC.To Patricia Elizalde of the IBYME laboratory for her advice and financial support for the stay and experiments. To the Pathology Services of the School “José de San Martin” Hospital (Corrientes) and J.R. Vidal Hospital (Corrientes) for the sample donation. To the Secretary of Science and Technology of the UNNE for the economic contribution of the projects. We thank Mariana Climent for translating this article.

References

- Baselga J, Swain SM. Novel anticancer target: revisiting ERBB2 and discovering ERBB3. Nat Rev Cancer 2009, 9, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minner S, Rump D, Tennstedt P, Simon R, Burandt E, Terracciano L, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor protein expression and genomic alterations in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2012, 118, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moasser, MM. The oncogene HER2: Its signaling and transforming functions and its role in human cancer pathogenesis. Oncogene 2007, 26, 6469–6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Liu C, Han J, Zhen L, Zhang T, He X, et al. HER2 expression in renal cell carcinoma is rare and negatively correlated with that in normal renal tissue. Oncol Lett. 2012, 4, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Receptores ErbB y cáncer. Methods Mol Biol. 2017, 1652, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu S, Liu Q, Han X, Qin S, Zhao W, Li A, et al. Development and clinical application of anti-HER2 monoclonal and bispecific antibodies for cancer treatment. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2017, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose R, Kavuri SM, Searleman AC, Shen W, Shen D, Koboldt DC, et al. Activating HER2 mutations in HER2 gene amplification negative breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo B, Wu XH, Feng YJ, Zheng HM, Zhang Q, Liang XJ, et al. Nuclear Her2 contributes to paclitaxel resistance in breast cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2021, 32, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh JJ, Purdue MP, Signoretti S, Swanton C, Albiges L, Schmidinger M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017, 3, 17009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luviano-García EH, Sandoval-Pulido JI, González-Pérez R, García-Torres V, Cueva Martínez E, Sierra-Díaz E. TNM vs grado nuclear (OMS-ISUP): supervivencia en pacientes con cáncer renal de células claras. Bol Col Mex Urol 2021, 36, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi S, Kessler ER, Bernard B, Flaig TW, Lam ET. Renal cell carcinoma: a review of biology and pathophysiology. F1000Res. 2018, 7, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini M, Amoreo CA, Torregrossa L, Alì G, Munari E, Jeronimo C, et al. Assessment of HER2 Protein Overexpression and Gene Amplification in Renal Collecting Duct Carcinoma: Therapeutic Implication. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12, 3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorozu T, Sato S, Kimura T, Iwatani K, Onuma H, Yanagisawa T, et al. HER2 Status in Molecular Subtypes of Urothelial Carcinoma of the Renal Pelvis and Ureter. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2020, 18, e443–e449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novara G, Martignoni G, Artibani W, Ficarra V. Grading systems in renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2007, 177, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delahunt B, Eble JN, Egevad L, Samaratunga H. Grading of renal cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 2019, 74, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahunt B, Eble JN, Samaratunga H, Thunders M, Yaxley JW, Egevad L. Staging of renal cell carcinoma: current progress and potential advances. Pathology. 2021, 53, 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, Dowsett M, McShane LM, Allison KH, et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014, 138, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schillaci, R. , Guzmán, P., Cayrol, F. Wendy Beguelin, María C Díaz Flaqué, Cecilia J Proietti, et al. Clinical relevance of ErbB-2/HER2 nuclear expression in breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, Deshpande N, Varambally R, Ghosh D, et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia. 2004, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Sánchez I, Polo-Rosales Y, Zaragoza-Durañona R, Sánchez-Lorenzo I. Características clínicas y epidemiológicas de pacientes con adenocarcinoma de células renales tratados con nefrectomía radical. Revista Electrónica Dr. Zoilo E. Marinello Vidaurreta [Internet].2020. Available from: http://www.revzoilomarinello.sld.cu/index.php/zmv/article/view/2335.

- Capitanio U, Bensalah K, Bex A, Boorjian SA, Bray F, Coleman J, et al. Epidemiology of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2019, 75, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif Z, Watters AD, Bartlett JM, Underwood MA, Aitchison M. Gene amplification and overexpression of HER2 in renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int. 2002, 89, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc NB, Ehara H, Gotoh T, Nakano M, Yokoi S, Deguchi T, Hirose Y. Immunohistochemical analysis with multiple antibodies in search of prognostic markers for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 2007, 69, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa J, Mizokami A, Koshida K, Yoshida S, Naito K, Namiki M. Novel HER2 selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor, TAK-165, inhibits bladder, kidney and androgen-independent prostate cancer in vitro and in vivo. Int J Urol. 2006, 13, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi W, Zhang G, Ma Z, Li L, Liu M, Qin L, et al. Hyperactivation of HER2-SHCBP1-PLK1 axis promotes tumor cell mitosis and impairs trastuzumab sensitivity to gastric cancer. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nami B, Wang Z. A Non-Canonical p75HER2 Signaling Pathway Underlying Trastuzumab Action and Resistance in Breast Cancer. Cells. 2024, 13, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lkhagvadorj S, Oh SS, Lee MR, Jung JH, Chung HC, Cha SK, et al. VEGFR-1 Expression Relates to Fuhrman Nuclear Grade of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Lifestyle Med. 2014, 4, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).