Submitted:

14 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Problem Statement

1.3. Research Main Objective

1.4. Research Questions

- RQ1: Can the state-of-the-art general-purpose LLMs perform construction cost estimation workflow tasks in zero-shot learning, without additional instructions and data?

- RQ2: Can we change the behavior of LLM to better perform construction cost estimation tasks with modular CoT prompting?

1.5. Contributions

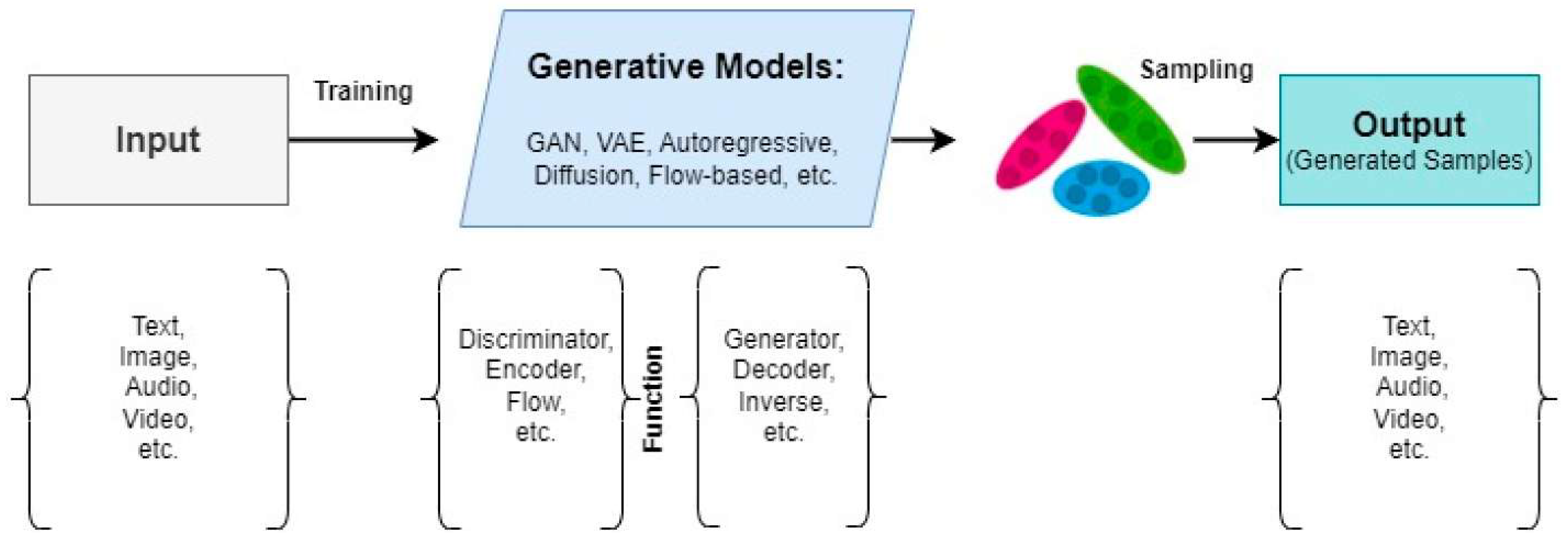

2. Literature Review

2.1. Existing Cost Estimation Approaches in Commercial Construction

2.2. Application of Generative Pre-Trained LLMs in Construction Cost Estimation

2.3. Chain of Thoughts (CoT) Prompting

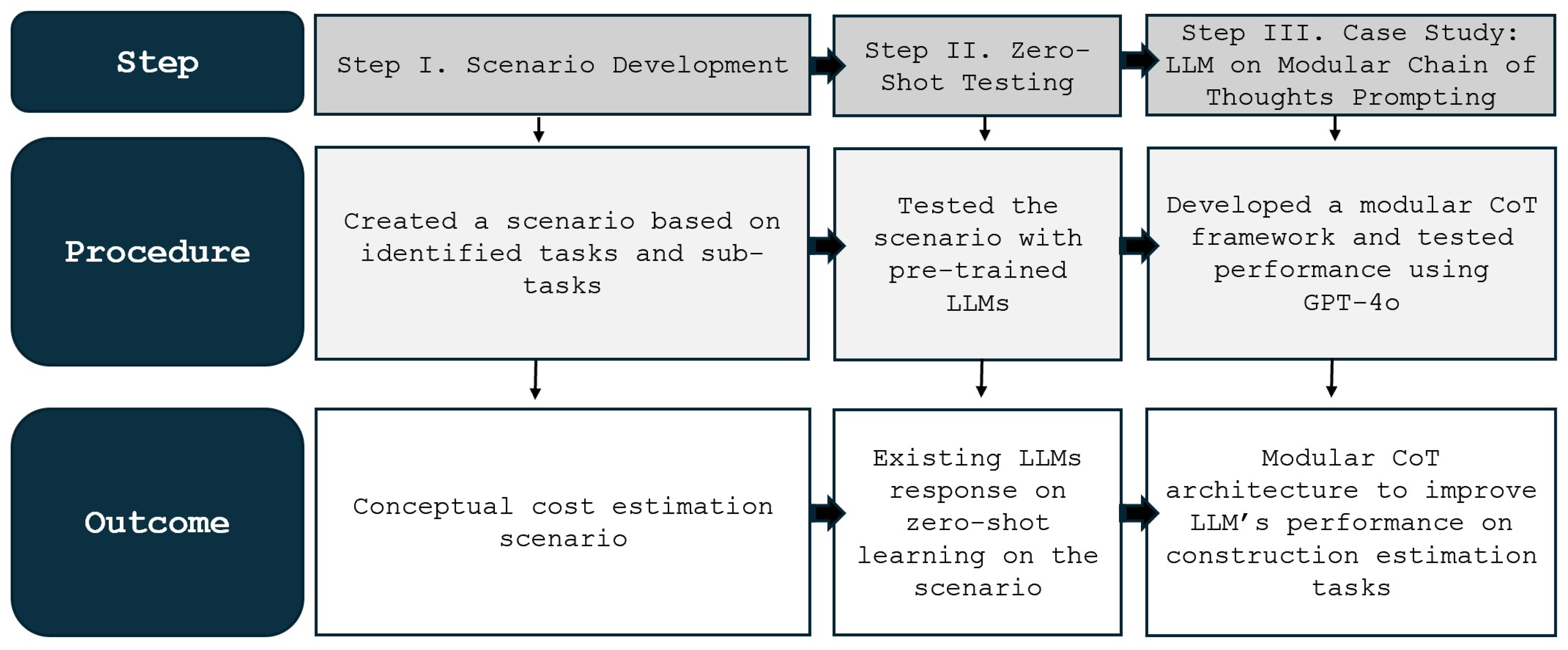

3. Methodology

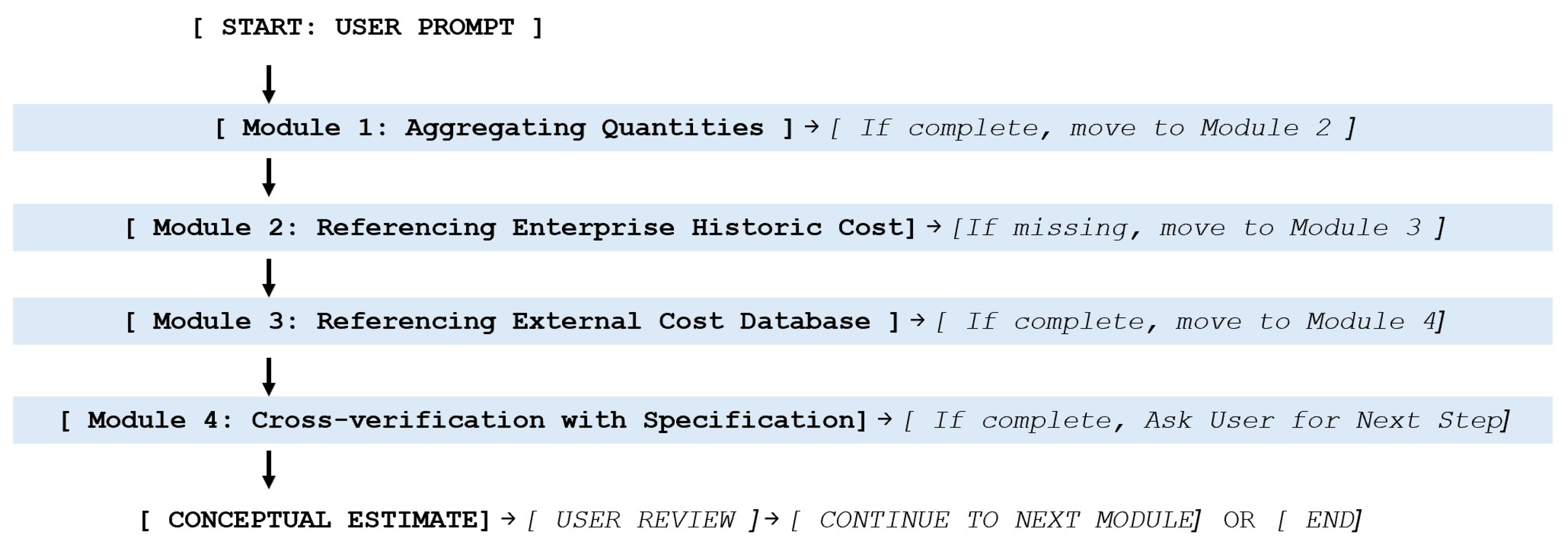

3.1. Proposed LLM Framework

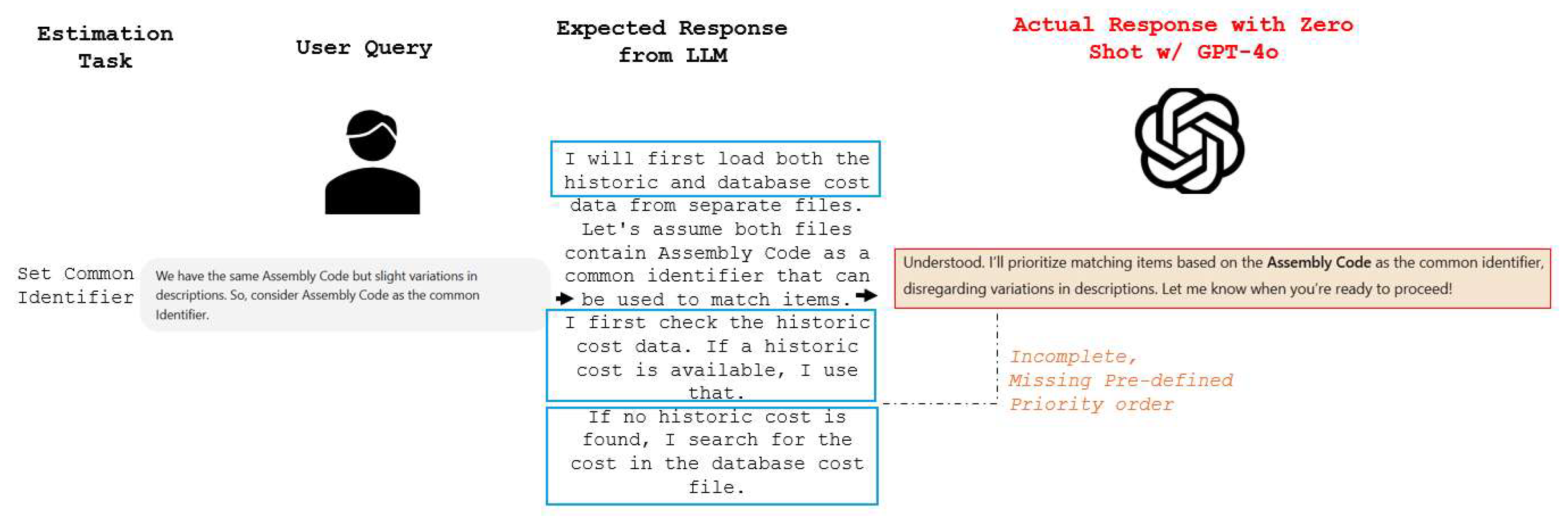

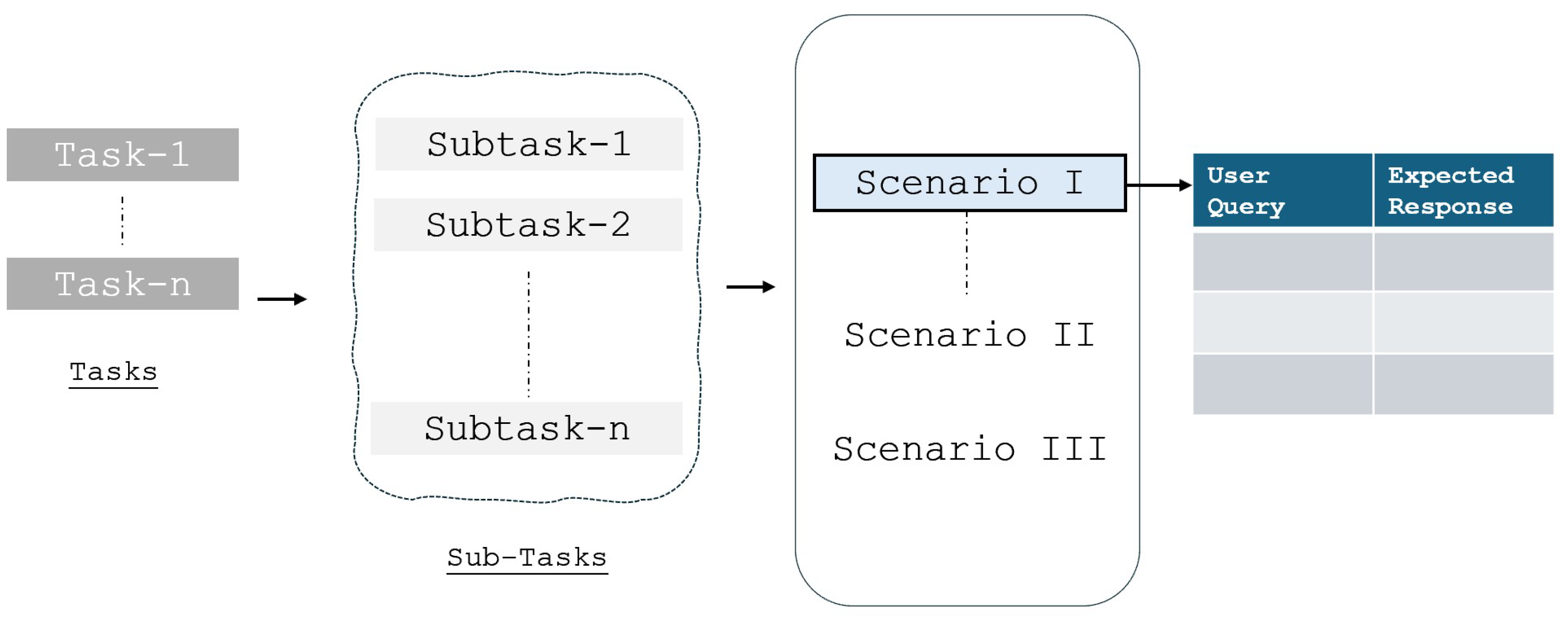

3.2. Cost Estimation Scenario for Existing LLMs

3.3. Cost Estimation Scenario for Existing LLMs

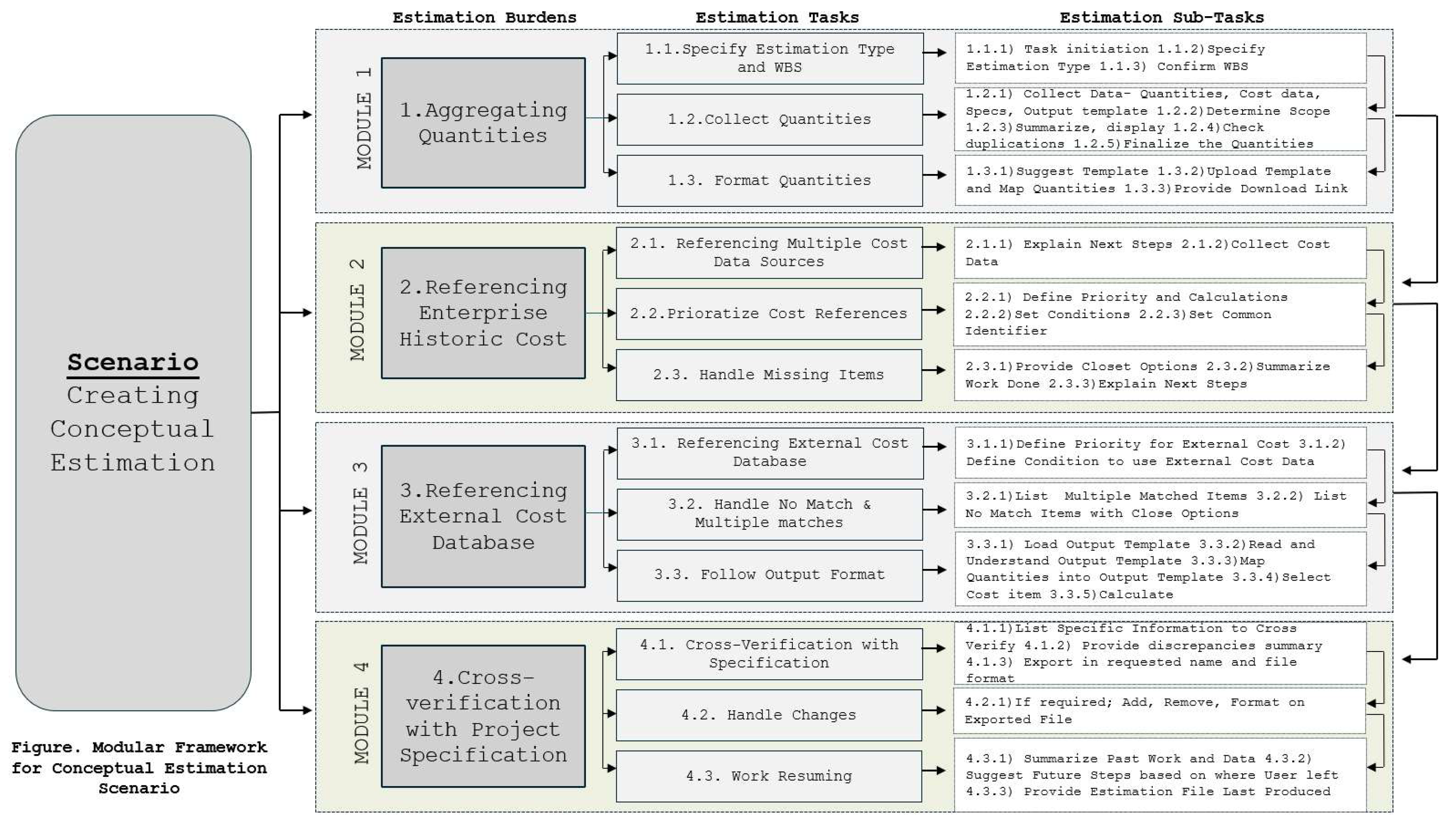

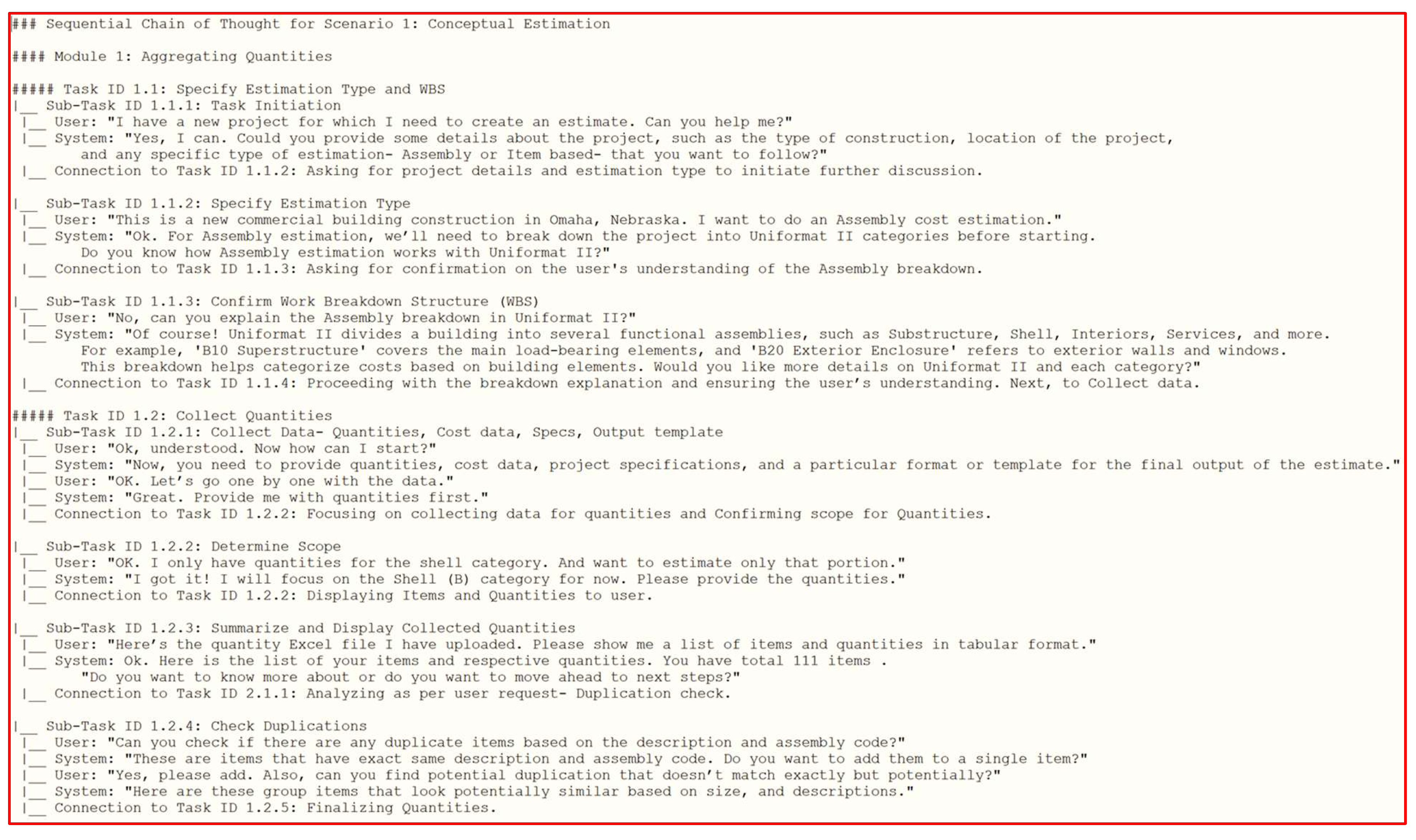

4. Case Study: Modular Chain of Thoughts Prompting for Conceptual Estimation

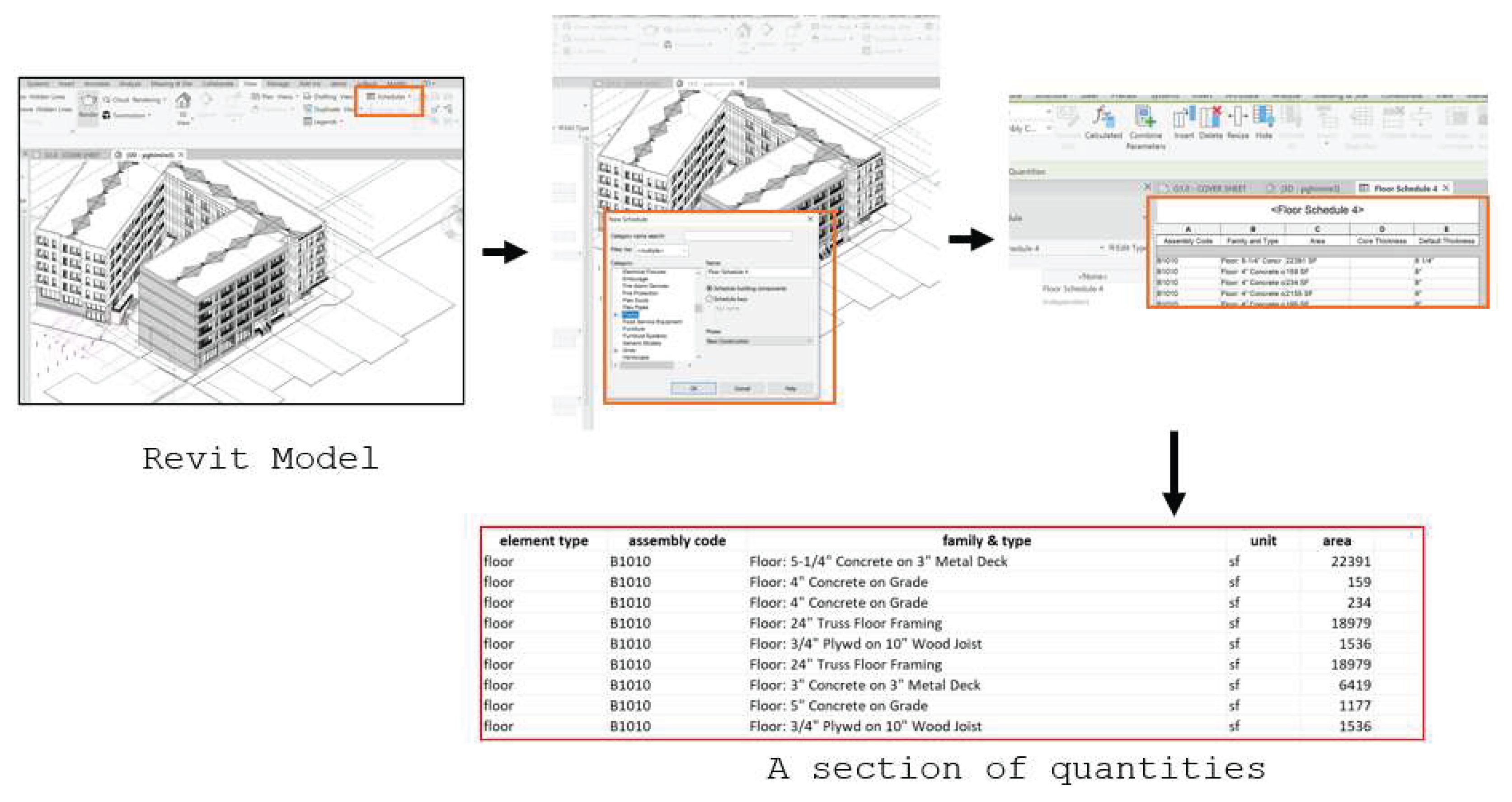

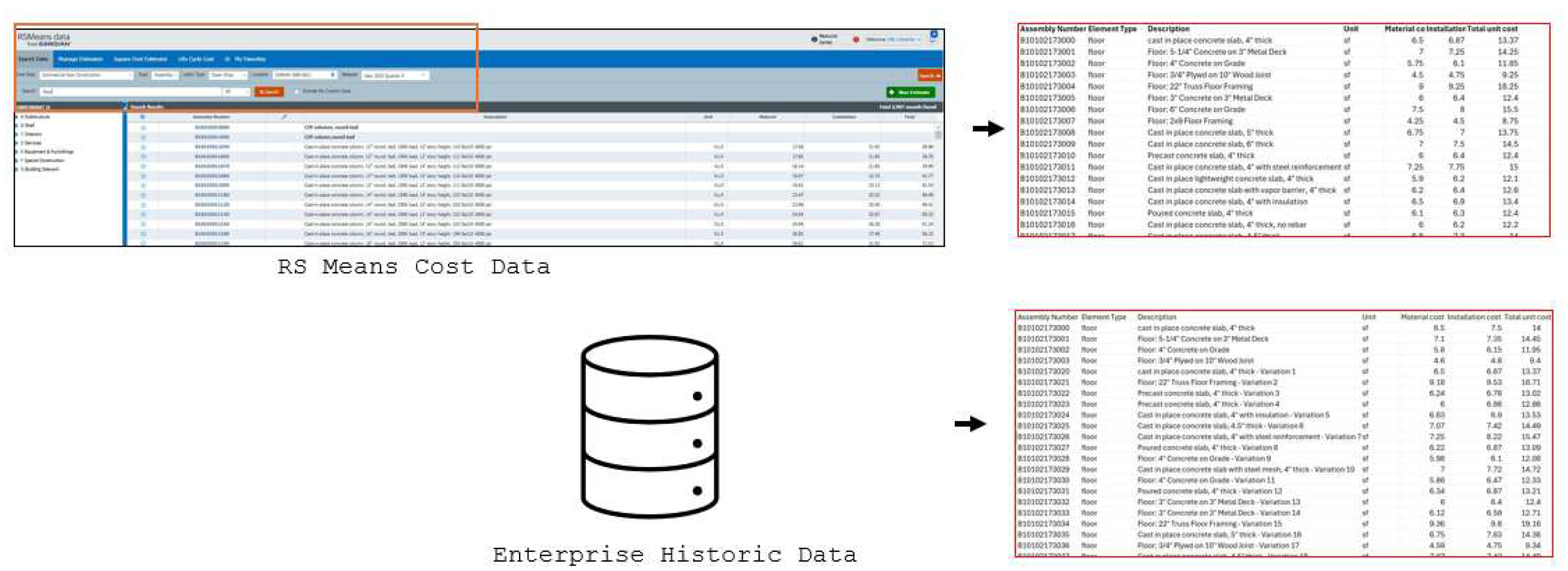

4.1. Data

4.2. Modular Framework for the Scenario

4.3. CoT Instructions

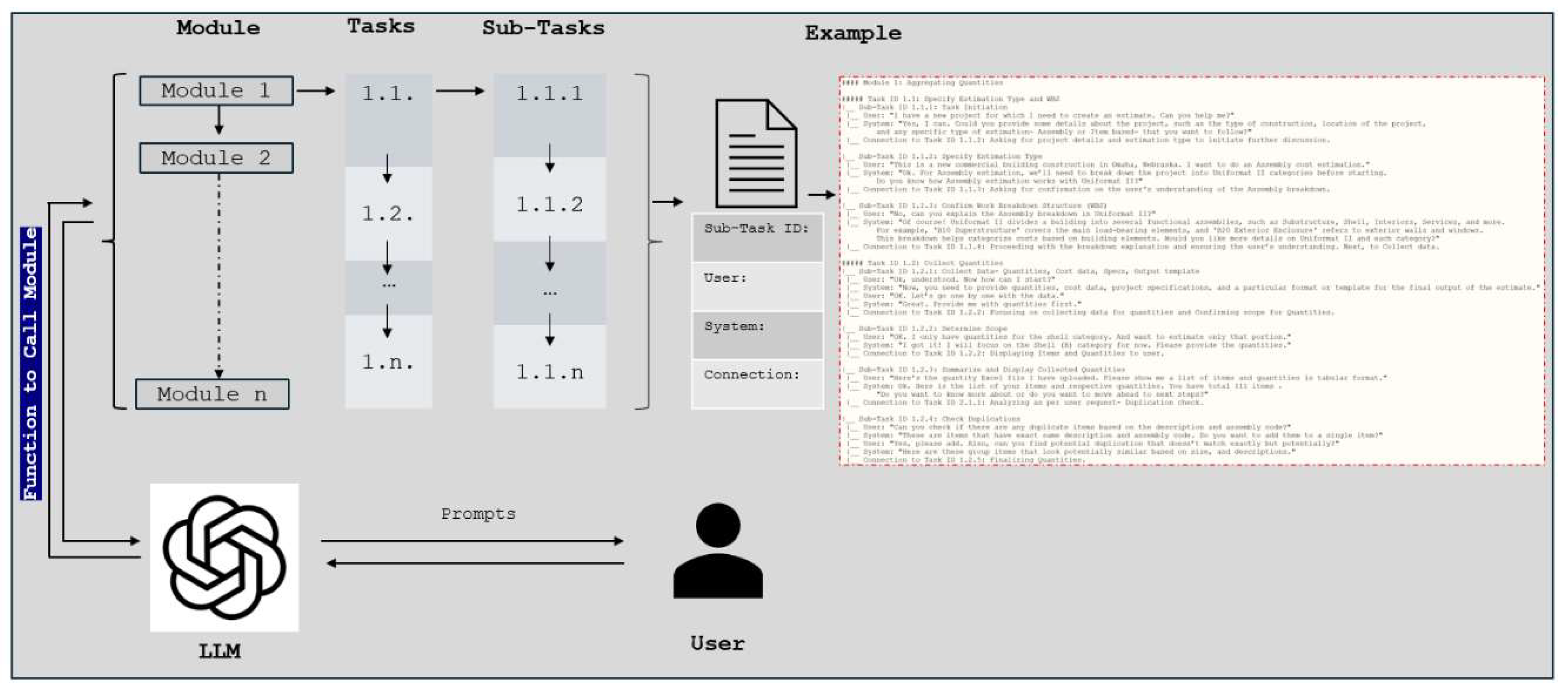

4.4. Modular CoT Architecture

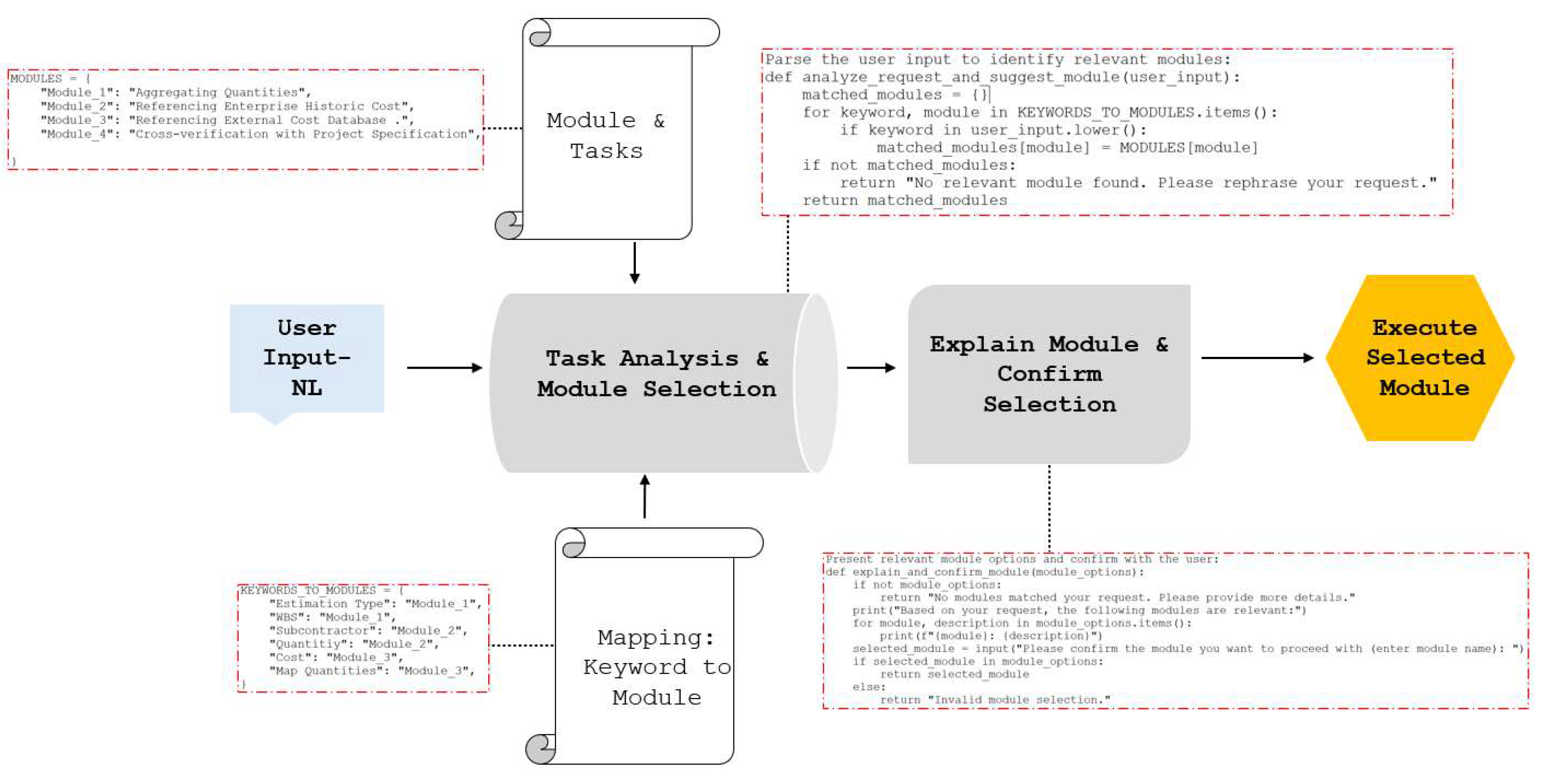

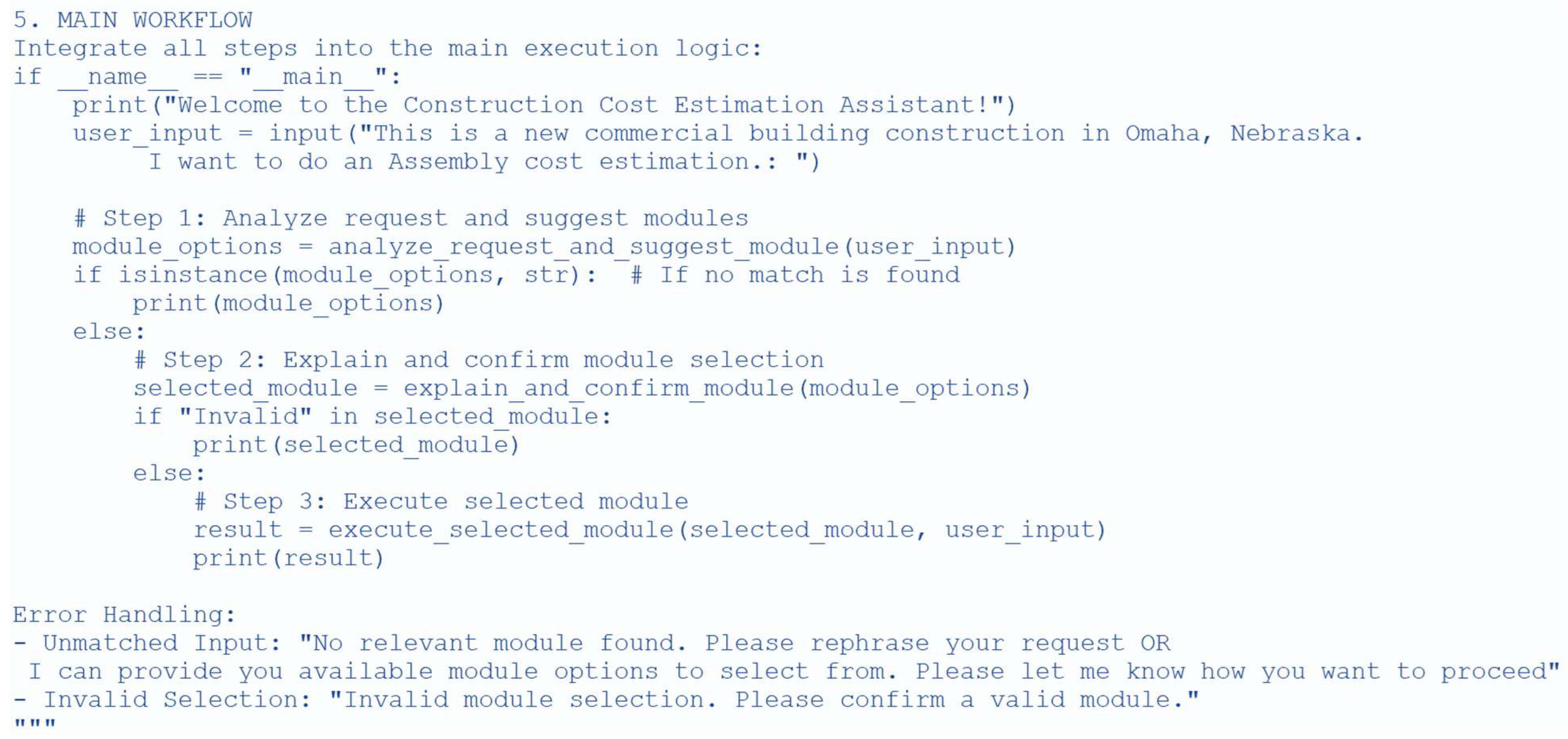

4.5. Module Calling Function

5. Results & Discussion

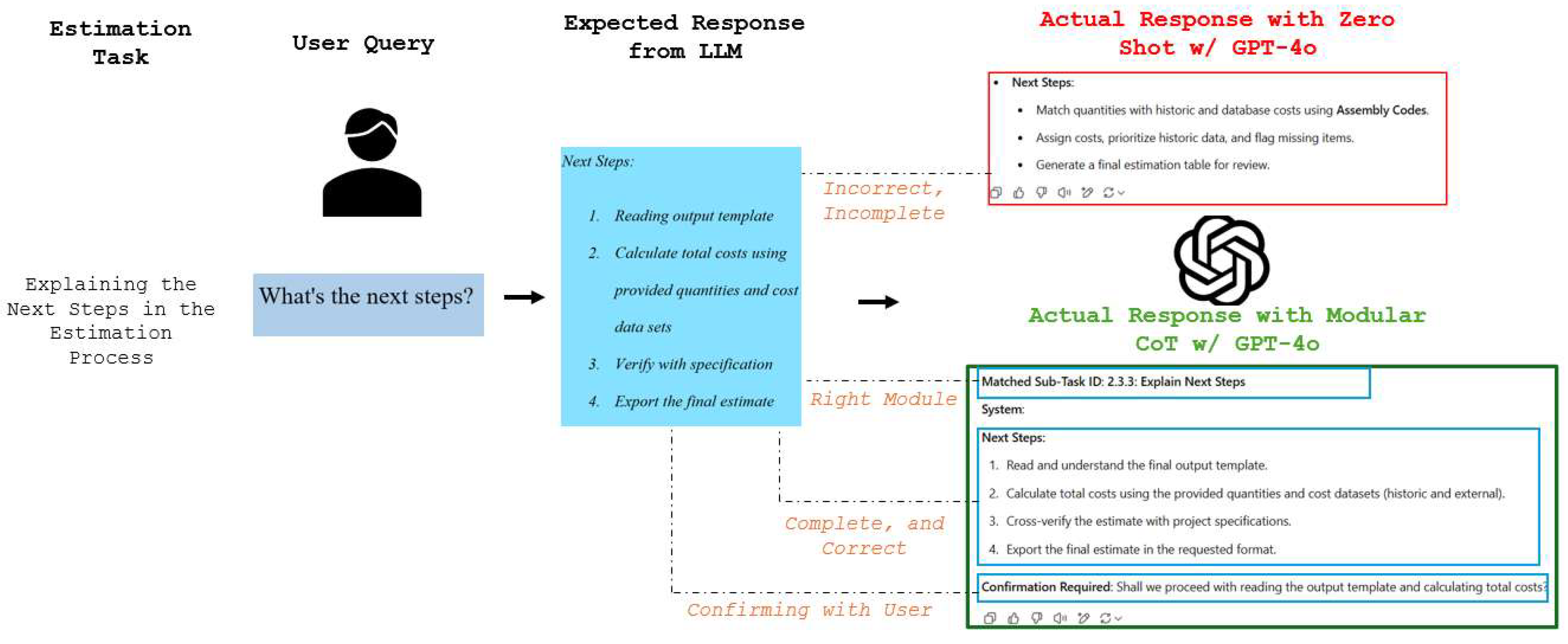

5.1. Qualitative Evaluation

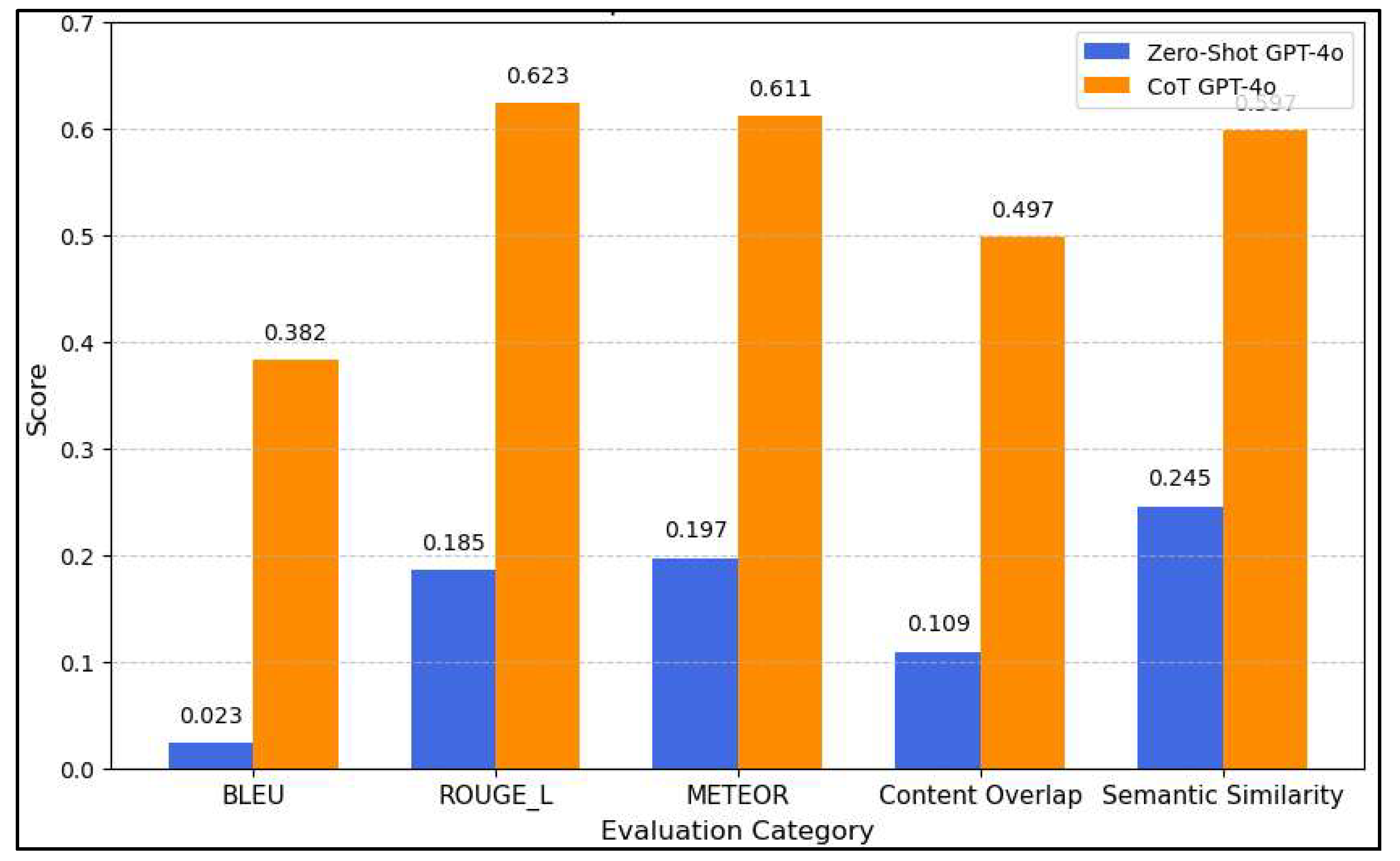

5.2. Quantitative Evaluation

6. Limitations and Future Work

7. Conclusion

Appendix A. Burdens to Taks to Sub- Tasks Mapping [59]

| Estimation Burdens | Tasks | Sub-Tasks |

|

Aggregating Quantities |

Specify Estimation Type and WBS |

|

| Collect Quantities |

|

|

| Format Quantities |

|

|

|

Referencing Enterprise Historic Cost |

Referencing Multiple Cost Data Sources |

|

| Prioritize Cost References |

|

|

| Handle Missing Items |

|

|

|

Referencing External Cost Database |

Referencing External Cost Database |

|

| Handle No Match & Multiple matches |

|

|

| Follow Output Format |

|

|

|

Cross-verification with Project Specification |

Cross-Verification with Specification |

|

| Handle Changes |

|

|

| Work Resuming |

|

|

|

Planning Evaluation |

Initialize Subcontractor Evaluation |

|

| Handle Inconsistencies & Mapping |

|

|

|

Evaluating Completeness |

Check Completeness |

|

| Evaluating Discrepancies |

|

|

| Identify Options |

|

|

|

Metrics Based Evaluation |

Metrics Based Evaluation |

|

| Create Negotiation List |

|

|

|

Visualizing and compiling |

Calculate and visualize |

|

| Compile Estimates |

|

|

| Generate Final Estimate |

|

|

|

Managing Changes |

Navigate Recent Estimation |

|

| Update Changes |

|

|

| Version Control | Naming Standard |

|

| Changes between Versions |

|

|

| Data Re-Cycling | Recycle to Historic database |

|

References

- Z. H. Ali and A. M. Burhan, “Hybrid machine learning approach for construction cost estimation: an evaluation of extreme gradient boosting model,” Asian J Civ Eng, vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 2427–2442, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- O. Swei, J. Gregory, and R. Kirchain, “Construction cost estimation: A parametric approach for better estimates of expected cost and variation,” Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, vol. 101, pp. 295–305, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Tayefeh Hashemi, O. M. Ebadati, and H. Kaur, “Cost estimation and prediction in construction projects: a systematic review on machine learning techniques,” SN Appl. Sci., vol. 2, no. 10, p. 1703, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Holm and J. E. Schaufelberger, Construction Cost Estimating. London: Routledge, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Ahiaga-Dagbui and S. D. Smith, “Rethinking construction cost overruns: cognition, learning and estimation,” Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 38–54, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Ghimire, S. Pokharel, K. Kim, and P. Barutha, “Machine learning-based prediction models for budget forecast in capital construction,” in Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Construction, Energy, Environment & Sustainability, Funchal, Portugal, 2023, pp. 27–30.

- J. Messner, “Introduction to Construction Cost Estimating,” Aug. 2022, Accessed: Mar. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://psu.pb.unizin.

- F. H. Abanda, B. Kamsu-Foguem, and J. H. M. Tah, “BIM – New rules of measurement ontology for construction cost estimation,” Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 443–459, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Ghimire, K. Kim, and M. Acharya, “Opportunities and Challenges of Generative AI in Construction Industry: Focusing on Adoption of Text-Based Models,” Buildings, vol. 14, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Rane, “Role of ChatGPT and Similar Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Construction Industry,” Oct. 10, 2023, Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY: 4598258. [CrossRef]

- M.-Y. Cheng, H.-C. Tsai, and W.-S. Hsieh, “Web-based conceptual cost estimates for construction projects using Evolutionary Fuzzy Neural Inference Model,” Automation in Construction, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 164–172, Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- H. H. Elmousalami, “Artificial Intelligence and Parametric Construction Cost Estimate Modeling: State-of-the-Art Review,” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, vol. 146, no. 1, p. 03119008, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Walton and J. D. Stevens, “Improving Conceptual Estimating Methods Using Historical Cost Data,” Transportation Research Record, vol. 1575, no. 1, pp. 127–131, Jan. 1997. [CrossRef]

- S.-H. Ji, M. Park, and H.-S. Lee, “Cost estimation model for building projects using case-based reasoning,” Can. J. Civ. Eng., vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 570–581, May 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Charette and H. E. Marshall, “UNIFORMAT II elemental classification for building specifications, cost estimating, and cost analysis,” National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, NIST IR 6389, 1999. [CrossRef]

- M. Sayed, M. Abdel-Hamid, and K. El-Dash, “Improving cost estimation in construction projects,” International Journal of Construction Management, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 135–143, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Juszczyk, “The Challenges of Nonparametric Cost Estimation of Construction Works with the use of Artificial Intelligence Tools,” Procedia Engineering, vol. 196, pp. 415–422, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Lim, W.-K. Hong, D. Lee, and S. Kim, “Automatic Rebar Estimation Algorithms for Integrated Project Delivery,” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. O. Elfaki, S. Alatawi, and E. Abushandi, “Using Intelligent Techniques in Construction Project Cost Estimation: 10-Year Survey,” Advances in Civil Engineering, vol. 2014, no. 1, p. 107926, 2014. [CrossRef]

- RSMeans and S., A. Mubarak, How to Estimate with RSMeans Data: Basic Skills for Building Construction. John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

- S. O. Babatunde, S. Perera, D. Ekundayo, and T. E. Adeleye, “An investigation into BIM-based detailed cost estimating and drivers to the adoption of BIM in quantity surveying practices,” Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 61–81, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Wahab and J. Wang, “Factors-driven comparison between BIM-based and traditional 2D quantity takeoff in construction cost estimation,” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 702–715, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Mahamid, “Factors affecting cost estimate accuracy: Evidence from Palestinian construction projects,” International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 117–125, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Akanbi and J. Zhang, “Design information extraction from construction specifications to support cost estimation,” Automation in Construction, vol. 131, p. 103835, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Feuerriegel, J. Hartmann, C. Janiesch, and P. Zschech, “Generative AI,” Bus Inf Syst Eng, vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 111–126, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Baidoo-anu and L. O. Ansah, “Education in the Era of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI): Understanding the Potential Benefits of ChatGPT in Promoting Teaching and Learning,” Journal of AI, vol. 7, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Zheng and M. Fischer, “Dynamic prompt-based virtual assistant framework for BIM information search,” Automation in Construction, vol. 155, p. 105067, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Li, Y. Su, and W. Liu, “Text-To-Text Generative Adversarial Networks,” in 2018 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Jul. 2018, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, C. Zhang, M. Zhang, and I. S. Kweon, “Text-to-image Diffusion Models in Generative AI: A Survey,” Apr. 02, 2023. arXiv:arXiv:2303.07909. [CrossRef]

- V. Liu, T. Long, N. Raw, and L. Chilton, “Generative Disco: Text-to-Video Generation for Music Visualization,” Apr. 17, 2023. arXiv:arXiv:2304.08551. Accessed: Aug. 27, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2304.

- T. Lei, R. Barzilay, and T. Jaakkola, “Rationalizing Neural Predictions,” Nov. 02, 2016, arXiv: arXiv:1606.04155. Accessed: Aug. 27, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1606.04155.

- A. N. Wu, R. Stouffs, and F. Biljecki, “Generative Adversarial Networks in the built environment: A comprehensive review of the application of GANs across data types and scales,” Building and Environment, vol. 223, p. 109477, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Goodfellow et al., “Generative adversarial networks,” Commun. ACM, vol. 63, no. 11, pp. 139–144, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Kingma and M. Welling, “An Introduction to Variational Autoencoders,” MAL, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 307–392, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Radford, J. Wu, R. Child, D. Luan, D. Amodei, and I. Sutskever, “Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners”.

- J. Ho, A. Jain, and P. Abbeel, “Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Curran Associates, Inc., 2020, pp. 6840–6851. Accessed: Sep. 16, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2020/hash/4c5bcfec8584af0d967f1ab10179ca4b-Abstract.

- M. Kumar et al., VideoFlow: A Flow-Based Generative Model for Video. 2019.

- J. Lee, H. Kim, J. Shim, and E. Hwang, “Cartoon-Flow: A Flow-Based Generative Adversarial Network for Arbitrary-Style Photo Cartoonization,” in Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, in MM ’22. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, Oct. 2022, pp. 1241–1251. [CrossRef]

- H. Wan, J. Zhang, Y. Chen, W. Xu, and F. Feng, “Generative AI Application for Building Industry,” Oct. 01, 2024. arXiv:arXiv:2410.01098. [CrossRef]

- A. Saka et al., “GPT Models in Construction Industry: Opportunities, Limitations, and a Use Case Validation,” May 30, 2023. arXiv:arXiv:2305.18997. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Prieto, E. T. Mengiste, and B. García de Soto, “Investigating the Use of ChatGPT for the Scheduling of Construction Projects,” Buildings, vol. 13, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Mohamed Hassan, E. Marengo, and W. Nutt, “A BERT-Based Model for Question Answering on Construction Incident Reports,” in Natural Language Processing and Information Systems, P. Rosso, V. Basile, R. Martínez, E. Métais, and F. Meziane, Eds., in Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 215–223. [CrossRef]

- K. Kim, M. Ivashchenko, P. Ghimire, and P.-C. Huang, “Context-Aware and Adaptive Task Planning for Autonomous Construction Robots Through Llm-Robot Communication,” May 14, 2024, Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY: 4827728. [CrossRef]

- K. Kim, P. Ghimire, and P.-C. Huang, “Framework for LLM-Enabled Construction Robot Task Planning: Knowledge Base Preparation and Robot–LLM Dialogue for Interior Wall Painting,” Robotics, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 117, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. Parsafard, O. Elezaj, D. Ekundayo, E. Vakaj, M. Parmar, and M. Ahmad Wani, “Automation in Construction Cost Budgeting using Generative Artificial Intelligence,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Dubai, UAE: IEOM Society International, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Gatto, J. Cassandro, C. Mirarchi, and A. Pavan, “LLM based automatic relation between cost domain descriptions and IFC objects,” MAR, 2024. Accessed: Feb. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://re.public.polimi.it/handle/11311/1280791.

- T. Kojima, S. (Shane) Gu, M. Reid, Y. Matsuo, and Y. Iwasawa, “Large Language Models are Zero-Shot Reasoners,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 35, pp. 22199–22213, Dec. 2022.

- A. Lazaridou, E. Gribovskaya, W. Stokowiec, and N. Grigorev, “Internet-augmented language models through few-shot prompting for open-domain question answering,” May 23, 2022. arXiv:arXiv:2203.05115. [CrossRef]

- S. Yao et al., “Tree of Thoughts: Deliberate Problem Solving with Large Language Models,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 36, pp. 11809–11822, Dec. 2023.

- J. Wei et al., “Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 35, pp. 24824–24837, Dec. 2022.

- Y. Nong, M. Aldeen, L. Cheng, H. Hu, F. Chen, and H. Cai, “Chain-of-Thought Prompting of Large Language Models for Discovering and Fixing Software Vulnerabilities,” Feb. 27, 2024. arXiv:arXiv:2402.17230. [CrossRef]

- T. Brown et al., “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Curran Associates, Inc., 2020, pp. 1877–1901. Accessed: Feb. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2020/hash/1457c0d6bfcb4967418bfb8ac142f64a-Abstract.

- D. Zhou et al., “Least-to-Most Prompting Enables Complex Reasoning in Large Language Models,” Apr. 16, 2023. arXiv:arXiv:2205.10625. [CrossRef]

- A. Madaan et al., “Self-Refine: Iterative Refinement with Self-Feedback,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 36, pp. 46534–46594, Dec. 2023.

- H. Conklin, B. Wang, K. Smith, and I. Titov, “Meta-Learning to Compositionally Generalize,” Jun. 29, 2021. arXiv:arXiv:2106.04252. [CrossRef]

- A. Creswell, M. Shanahan, and I. Higgins, “Selection-Inference: Exploiting Large Language Models for Interpretable Logical Reasoning,” May 19, 2022. arXiv:arXiv:2205.09712. [CrossRef]

- E. Zelikman, Y. Wu, J. Mu, and N. Goodman, “STaR: Bootstrapping Reasoning With Reasoning,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 35, pp. 15476–15488, Dec. 2022.

- A. Havrilla et al., “Teaching Large Language Models to Reason with Reinforcement Learning,” Mar. 07, 2024. arXiv:arXiv:2403.04642. [CrossRef]

- P. Ghimire, “Framework for Integrating Industry Knowledge into a Large Language Model to Assist Construction Cost Estimation,” Ph.D., The University of Nebraska - Lincoln, United States -- Nebraska, 2025. Accessed: Oct. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.proquest.com/docview/3198872319/abstract/D556793967F749FCPQ/1.

- R. Islam and O. M. Moushi, GPT-4o: The Cutting-Edge Advancement in Multimodal LLM. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Touvron et al., “LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models,” Feb. 27, 2023, Accessed: Aug. 26, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2302.13971. arXiv:arXiv:2302.13971.

- R. Islam and I. Ahmed, “Gemini-the most powerful LLM: Myth or Truth,” in 2024 5th Information Communication Technologies Conference (ICTC), May 2024, pp. 303–308. [CrossRef]

- R. Kurokawa et al., “Diagnostic performances of Claude 3 Opus and Claude 3.5 Sonnet from patient history and key images in Radiology’s ‘Diagnosis Please’ cases,” Jpn J Radiol, vol. 42, no. 12, pp. 1399–1402, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Papineni, S. Roukos, T. Ward, and W.-J. Zhu, “BLEU: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation,” in Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics - ACL ’02, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Association for Computational Linguistics, 2001, p. 311. [CrossRef]

- N. Diab, “Out of the BLEU: An Error Analysis of Statistical and Neural Machine Translation of WikiHow Articles from English into Arabic,” CDELT Occasional Papers in the Development of English Education, vol. 75, no. 1, pp. 181–211, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Lee et al., “A Survey on Evaluation Metrics for Machine Translation,” Mathematics, vol. 11, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Ganesan, “ROUGE 2.0: Updated and Improved Measures for Evaluation of Summarization Tasks,” Mar. 05, 2018. arXiv:arXiv:1803.01937. [CrossRef]

- C.-Y. Lin, “ROUGE: A Package for Automatic Evaluation of Summaries,” in Text Summarization Branches Out, Barcelona, Spain: Association for Computational Linguistics, Jul. 2004, pp. 74–81. Accessed: Mar. 02, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://aclanthology.org/W04-1013/.

- S. Banerjee and A. Lavie, “METEOR: An Automatic Metric for MT Evaluation with Improved Correlation with Human Judgments,” in Proceedings of the ACL Workshop on Intrinsic and Extrinsic Evaluation Measures for Machine Translation and/or Summarization, J. Goldstein, A. Lavie, C.-Y. Lin, and C. Voss, Eds., Ann Arbor, Michigan: Association for Computational Linguistics, Jun. 2005, pp. 65–72. Accessed: Mar. 02, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://aclanthology.org/W05-0909/.

- A. Holzinger, K. Zatloukal, and H. Müller, “Is human oversight to AI systems still possible?,” New Biotechnology, vol. 85, pp. 59–62, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- I. O. Gallegos et al., “Bias and Fairness in Large Language Models: A Survey,” Computational Linguistics, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 1097–1179, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Jung, F. Brahman, and Y. Choi, “Trust or Escalate: LLM Judges with Provable Guarantees for Human Agreement,” Jul. 25, 2024. arXiv:arXiv:2407.18370. [CrossRef]

- prolego-team/pdd. (Feb. 19, 2025). Python. prolego-team. Accessed: Mar. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/prolego-team/pdd.

- Y. Virk, P. Devanbu, and T. Ahmed, “Enhancing Trust in LLM-Generated Code Summaries with Calibrated Confidence Scores,” Dec. 03, 2024. arXiv:arXiv:2404.19318. [CrossRef]

- R. Liu, M. Li, S. Zhao, L. Chen, X. Chang, and L. Yao, “In-Context Learning for Zero-shot Medical Report Generation,” in Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, in MM ’24. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, Oct. 2024, pp. 8721–8730. [CrossRef]

- B. Merkus, “An assessment of Zero-Shot Open Book Question Answering using Large Language Models,” Master Thesis, 2023. Accessed: Mar. 02, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://studenttheses.uu.nl/handle/20.500.12932/44625.

- J. Salvador, N. Bansal, M. Akter, S. Sarkar, A. Das, and S. K. Karmaker, “Benchmarking LLMs on the Semantic Overlap Summarization Task,” Feb. 26, 2024. arXiv:arXiv:2402.17008. [CrossRef]

- S. Xu et al., “Reasoning before Comparison: LLM-Enhanced Semantic Similarity Metrics for Domain Specialized Text Analysis,” Feb. 20, 2024. arXiv:arXiv:2402.11398. [CrossRef]

- G. Yang, Y. Zhou, X. Chen, X. Zhang, T. Y. Zhuo, and T. Chen, “Chain-of-Thought in Neural Code Generation: From and for Lightweight Language Models,” IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, vol. 50, no. 9, pp. 2437–2457, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Niwattanakul, J. Singthongchai, E. Naenudorn, and S. Wanapu, “Using of Jaccard Coefficient for Keywords Similarity,” Hong Kong, 2013.

- P. Sitikhu, K. Pahi, P. Thapa, and S. Shakya, “A Comparison of Semantic Similarity Methods for Maximum Human Interpretability,” in 2019 Artificial Intelligence for Transforming Business and Society (AITB), Nov. 2019, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

| ID | Estimation Sub-Task | Query from the “User” | Expected Answer from “LLM” |

| 1 | Task Initiation | I have a new project for which I need to create an estimate. Can you help me? | Yes, I can. Could you provide some details about the project, such as the type of construction, location of the project, and any specific type of estimation- Assembly or Item based- that you want to follow? |

| 2 | Specify Estimation Type | Yes. This is a new commercial building construction in Omaha, Nebraska. I want to do an Assembly cost estimation. | Ok. For assembly estimation, you need to know the assembly breakdown in Uniformat II before starting the estimation. Do you know this? |

| 3 | Confirm Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) | No, can you explain the Assembly breakdown in Uniformat II down structure for me? |

Of course! Uniformat II divides the building into major functional areas or “assemblies” based on the work they perform. Here’s an overview of the Uniformat II structure, broken down into its primary categories: A. Substructure This section includes all the elements related to the building’s foundation and below-grade construction:

The building’s exterior envelope or shell:

This section covers everything inside the building:

Systems that provide utilities and services to the building:

This category covers the built-in equipment and furnishings in the building:

Non-standard or specialized construction:

Anything outside the building footprint:

|

| 4 | Collect Quantities | Ok, understand. Now how can I start? | Now, you need to provide quantities, cost data, project specifications, and a particular format or template for the final output of the estimate. |

| 5 | Collect Quantities | OK. let’s go one by one with the data | Great. Provide me quantities. |

| 6 | Determine Scope | OK. I only have quantities for the shell category. And want to estimate only that portion. | I got it! I will focus on the Shell (B) category for now. Please provide the quantities. |

| 7 | Summarize and Display Collected Quantities | Here’s the quantity excel file I have uploaded. Please show me a list of items and quantities in tabular format. | Ok. Here is the list of your items and respective quantities. Do you want to know more about, or do you want to move ahead to the next steps? |

| 8 | Check Duplications | Can you check if there are any duplicate items based on the description and assembly code? | These are items that have exactly the same description and assembly code. Do you want to add them to a single item? |

| 9 | Check Duplications | Yes, please add. Also, can you find potential duplication that doesn’t match exactly but potentially? | Here are these group items that look potentially similar based on size and descriptions. |

| 10 | Finalize Quantities | No, they are not the same items. Keep separate. | Ok. We have now total 25 items. What do you want to do next with quantities? Should we move to cost data? |

| 11 | Format Quantities | Now, I want you to help formatting before starting estimate. Can you do that? | Yes, I can. Do you have any template of format or you want me to suggest some format? |

| 12 | Suggest Template | Please suggest a template format suitable for this estimation | Here is the suggested format suitable for the assembly estimate… Do you want to use this? Or do you want me to create other templates? |

| 13 | Upload Template and Map Quantities | I have one standard template format for quantities. Here I have uploaded. Please put quantities into this new format and follow this instructions to do mapping- i)Read Instructions inside Template file, each description under every title is the description for you understand what it means ii) Look at example output and understand iii) map all quantities to suitable section of this template’s yellow highlighted area, and you are free to add remove rows as required for items. Show the table and save. |

I have arranged the original quantities into the new template that you provided as per instructions i, ii, and iii. See the table below. Let me know if you want to modify or change anything. |

| 14 | Provide download link | Also, can you export new table in excel format. | You can click on the link below to download the new quantities table. |

| 15 | Referencing Multiple Cost Data Sources | Now, we are good for quantities. What’s our next task? | We will work on cost data in the next step. Please provide me with cost data. |

| 16 | Collect Cost Data | Ok. I have uploaded two datasets for cost data that I want to use. 1) Historic cost- enterprise database 2) External cost database | Great! I have stored both datasets. How do you want to set up the estimation to use both your historic cost and external cost? |

| 17 | Define Priority and calculations | I want to use the historical database as much as possible. | Ok. I can structure the estimation to prioritize historic cost and only use the database cost if the historic cost for an item is not available. |

| 18 | Define Priority and calculations | In the historic cost data add a column and get the average of all available commercial projects, for all cost items | Ok. The new column is added to historic dataset, I have saved the updated data. I have calculated the average for items in past commercial projects Here is the table: |

| 19 | Set Conditions | I want to use historic cost for all items if it is available. If not , then i want to use database cost. | Ok. I can structure the estimation to prioritize historic cost and only use the database cost if the historic cost for an item is not available. |

| 20 | Set Common Identifier | How would you prioritize? | Are there any common identifiers in two cost data sets? On what basis you want to find items? |

| 21 | Set Common Identifier | We have the same Assembly Code but slight variations in descriptions. So, consider Assembly Code as the common Identifier. |

I will first load both the historic and database cost data from separate files. Let’s assume both files contain Assembly Code as a common identifier that can be used to match items. I first check the historic cost data. If a historic cost is available, I use that. If no historic cost is found, I search for the cost in the database cost file. |

| 22 | Handle Missing Items | If an item is missing from both datasets, what would you do? | I will ask you with closest options based on description. |

| 23 | Summarize Work Done | Briefly Summarize in bullet points: what you have done so far, what data you have, what data you need now |

Summary of What Has Been Done:

|

| 24 | Explain Next Steps | What’s the next steps? |

Next Steps:

|

| 25 | Output Template Recall | Here, I have uploaded the output template file and specification file. Please read and store both files. | Thank you! Now that I have the output template and project specification files. Can I go ahead start cost calculations? |

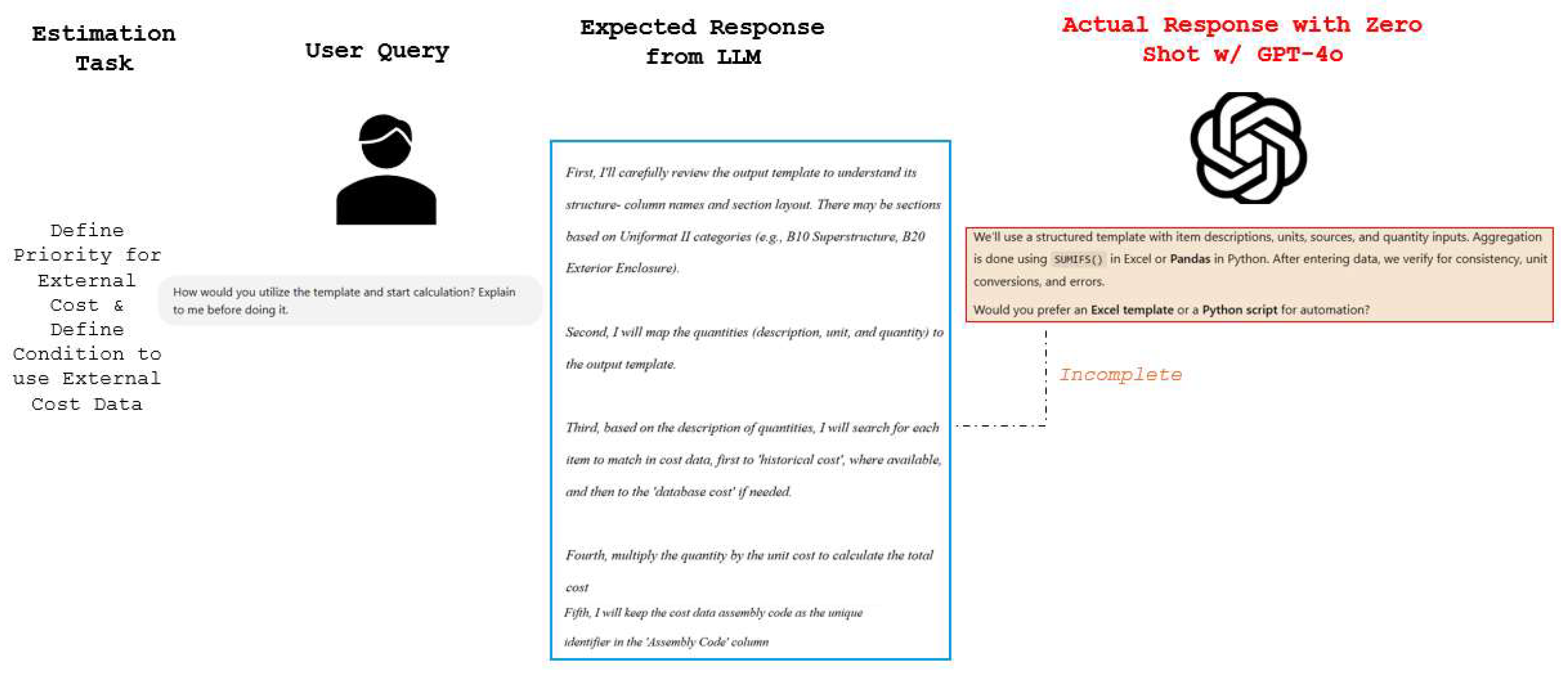

| 26 | Define Priority for External Cost & Define Condition to use External Cost Data | How would you utilize the template and start calculation? Explain to me before doing it. |

First, I’ll carefully review the output template to understand its structure- column names and section layout. There may be sections based on Uniformat II categories (e.g., B10 Superstructure, B20 Exterior Enclosure). Second, I will map the quantities (description, unit, and quantity) to the output template. Third, based on the description of quantities, I will search for each item to match in cost data, first to ‘historical cost’, where available, and then to the ‘database cost’ if needed. Fourth, multiply the quantity by the unit cost to calculate the total cost Fifth, I will keep the cost data assembly code as the unique identifier in the ‘Assembly Code’ column |

| 27 | Handling No Match Items | What if you don’t find an exact match? | If I don’t find each match in the cost data, I will ask you to select with the closest options (maximum 5 options). |

| 28 | Handling Multiple Matched Items | What if you find multiple matches? | If I find multiple matching items in the cost data, I will provide you with options and ask you to select one out of those options. |

| 29 | Follow Output Format | Can you export the estimate in excel format with the file name ‘conceptual estimation _today’s date)? | Yes, I can export the estimate with the file name “conceptual estimation_[today’s date].” |

| 30 | Cross-Verification with Specification | Ok. If I want to verify anything with specifications, how would you help? |

I can help you in multiple ways: I can provide any specific information that you want to look at. I can also provide a summary of any discrepancies in item or installation description, between specification and items in estimation, that need clarification. And, If adjustments are required, I can incorporate them into the estimate. |

| 31 | Handle Changes | If something needs to be modified, added, removed, or corrected, would you do it for me? | Absolutely! If any modifications, additions, removals, or corrections are needed, just let me know the specific details, and I’ll make the necessary changes for you. Whether it’s adjusting costs, updating quantities, or correcting formatting, I’m happy to assist with all aspects of the estimate. |

| 32 | Work Resuming | If I stop here, and come back to continue work, could you remind me with summary of what we have done, and what’s next step, and providing me the last file? | Yes. When you come back, I’ll provide a quick summary of the work we’ve completed so far, including details like the data we’ve loaded, the calculations performed, and any adjustments made. I’ll outline the next steps based on where we left off, so you can pick up exactly where you need to. I’ll also share the last file we were working on. |

| Model | BLEU | ROUGE-L | METEOR |

| GPT4o | 0.023* | 0.185* | 0.196* |

| Llama 3.2 | 0.0126 | 0.112 | 0.157 |

| Gemini 2.0 | 0.010 | 0.095 | 0.122 |

| Claude 3.5 Sonnet | 0.0135 | 0.170 | 0.168 |

| Task ID | Estimation Sub-Task |

Completeness Criteria for LLM Response |

User Confidence Level on Response (1=Low 2=Medium 3= High) |

| 1 | Task Initiation |

|

3 |

| 2 | Specify Estimation Type |

|

2 |

| 3 | Confirm Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) |

|

3 |

| 4 | Collect Quantities |

|

1 |

| 5 | Collect Quantities |

|

1 |

| 6 | Determine Scope |

|

3 |

| 7 | Summarize and Display Collected Quantities |

|

3 |

| 8 | Check Duplications |

|

1 |

| 9 | Check Duplications |

|

1 |

| 10 | Finalize Quantities |

|

1 |

| 11 | Format Quantities |

|

3 |

| 12 | Suggest Template |

|

3 |

| 13 | Upload Template and Map Quantities |

|

2 |

| 14 | Provide download link |

|

2 |

| 15 | Referencing Multiple Cost Data Sources |

|

3 |

| 16 | Collect Cost Data |

|

2 |

| 17 | Define Priority and calculations |

|

3 |

| 18 | Define Priority and calculations |

|

2 |

| 19 | Set Conditions |

|

2 |

| 20 | Set Common Identifier |

|

2 |

| 21 | Set Common Identifier |

|

1 |

| 22 | Handle Missing Items |

|

1 |

| 23 | Summarize Work Done |

|

1 |

| 24 | Explain Next Steps |

|

1 |

| 25 | Output Template Recall |

|

2 |

| 26 | Define Priority for External Cost & Define Condition to use External Cost Data |

|

2 |

| 27 | Handling No Match Items |

|

1 |

| 28 | Handling Multiple Matched Items |

|

1 |

| 29 | Follow Output Format |

|

1 |

| 30 | Cross-Verification with Specification |

|

2 |

| 31 | Handle Changes |

|

3 |

| 32 | Work Resuming |

|

2 |

| Evaluation Category | Zero-Shot with GPT4o | CoT with GPT4o |

| BELU | 0.023365 | 0.382353 |

| ROUGE_L | 0.185215 | 0.622845 |

| METEOR | 0.196798 | 0.610922 |

| Content Overlap | 0.109057 | 0.497031 |

| Semantic Similarity | 0.245202 | 0.597011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).