Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- This paper proposes a two-stage network for joint low-light image enhancement and image fusion, which can alleviate overexposure and block artifacts while eliminating color deviation, named CDFFusion;

- A brightness enhancement formula without color deviation is proposed, which processes the three components (Y, Cb, Cr) simultaneously, and the processed results have no color deviation;

2. Related Work

3. Methods

3.1. Overall Framework

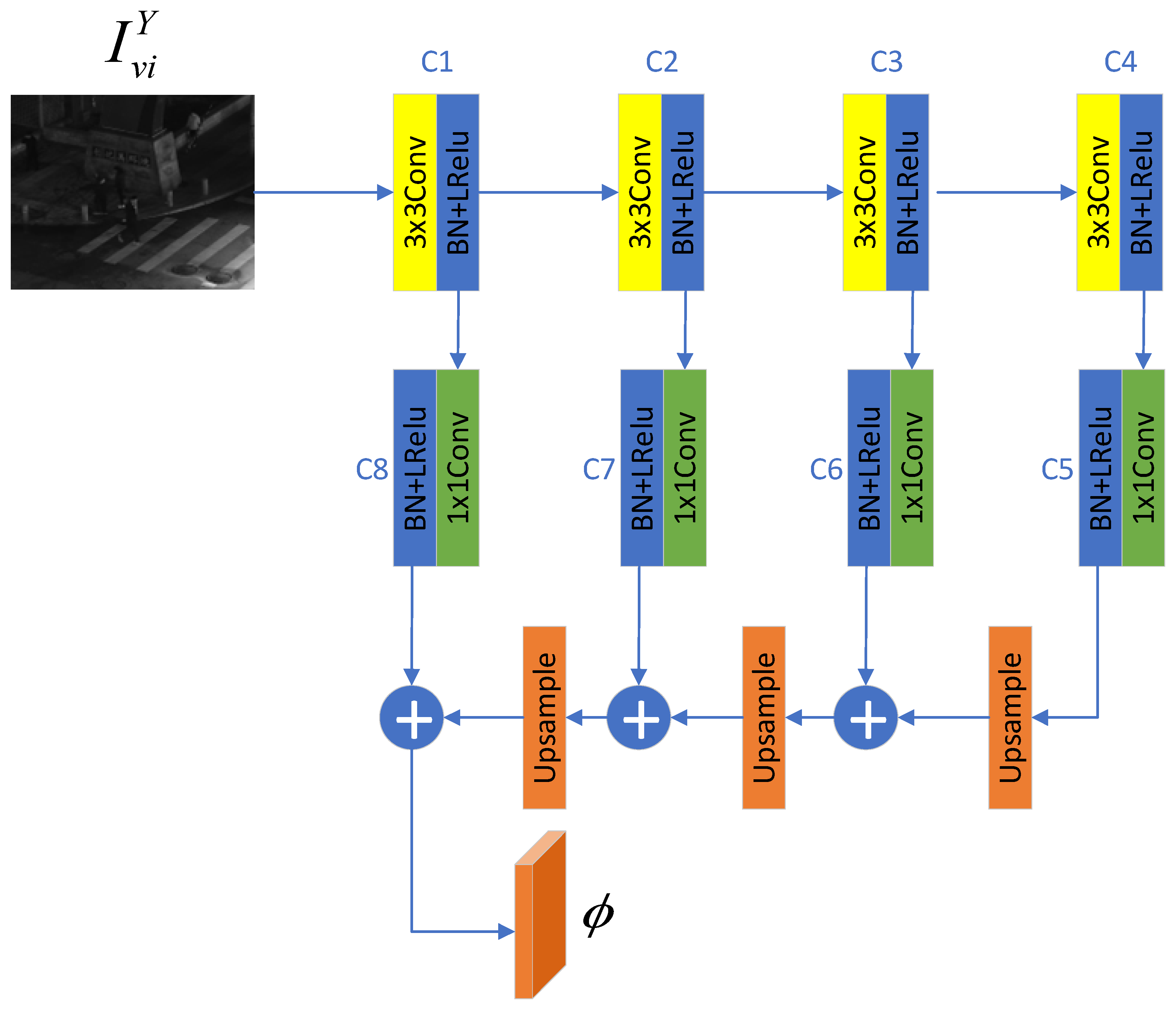

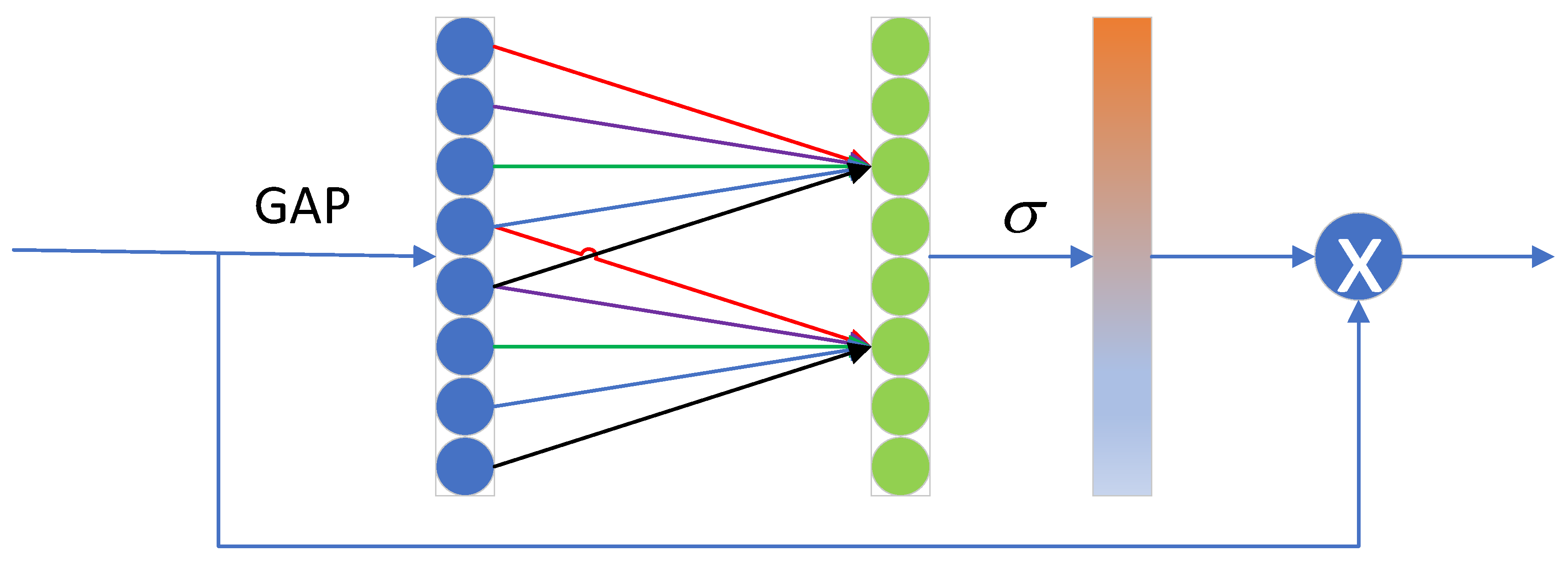

3.2. Reflectance-Illumination Decomposition Network(RID-Net)

3.3. Fusion Network

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Configuration

4.2. Results and Analysis

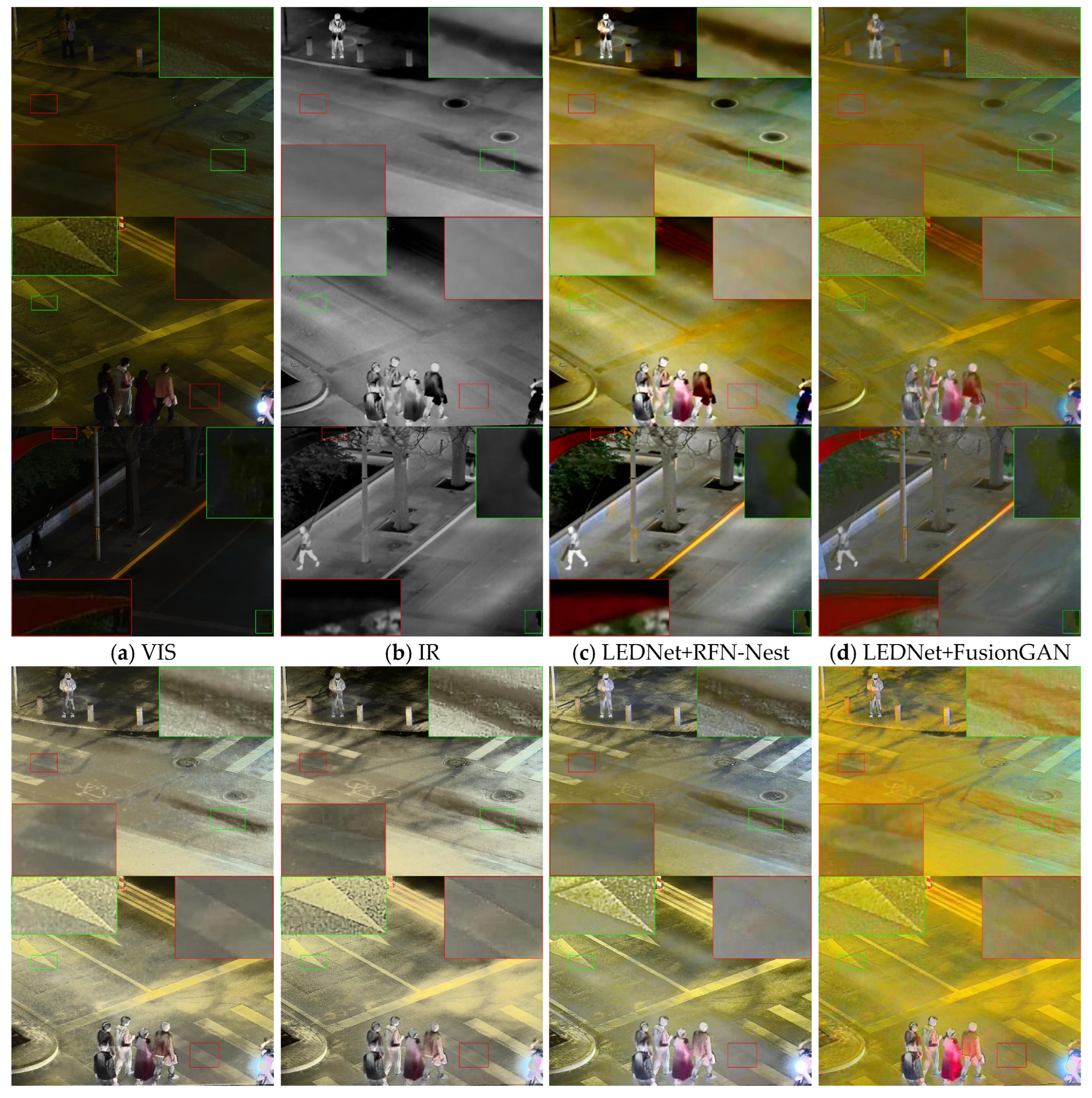

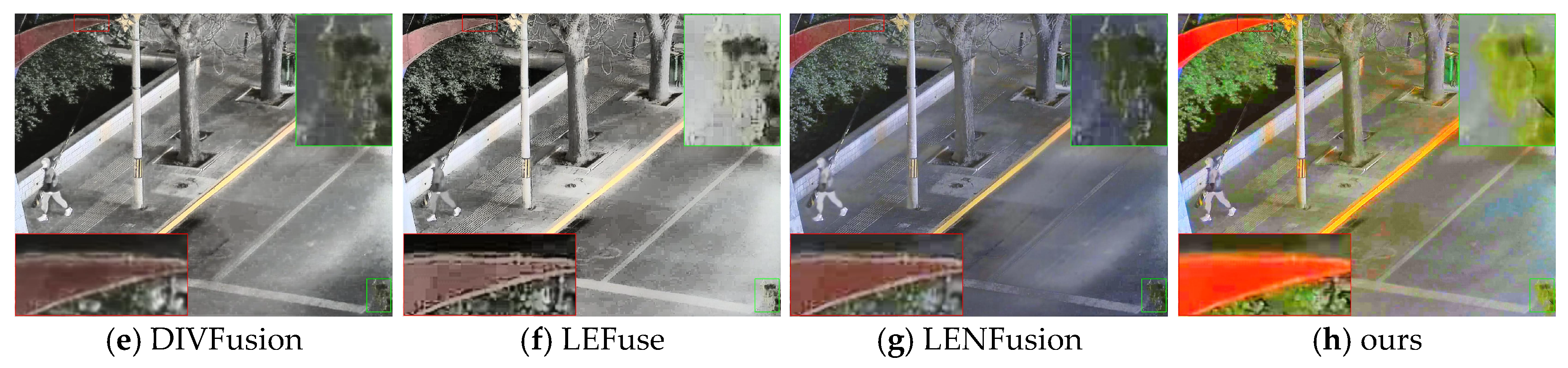

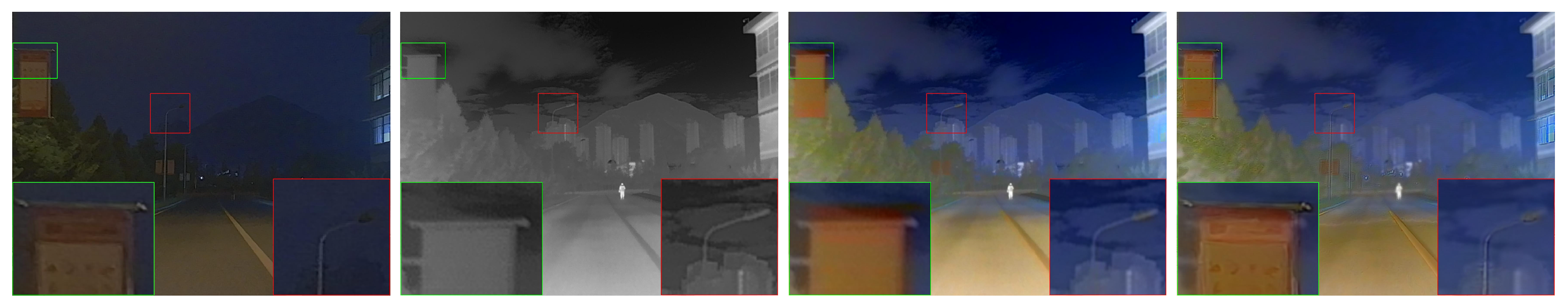

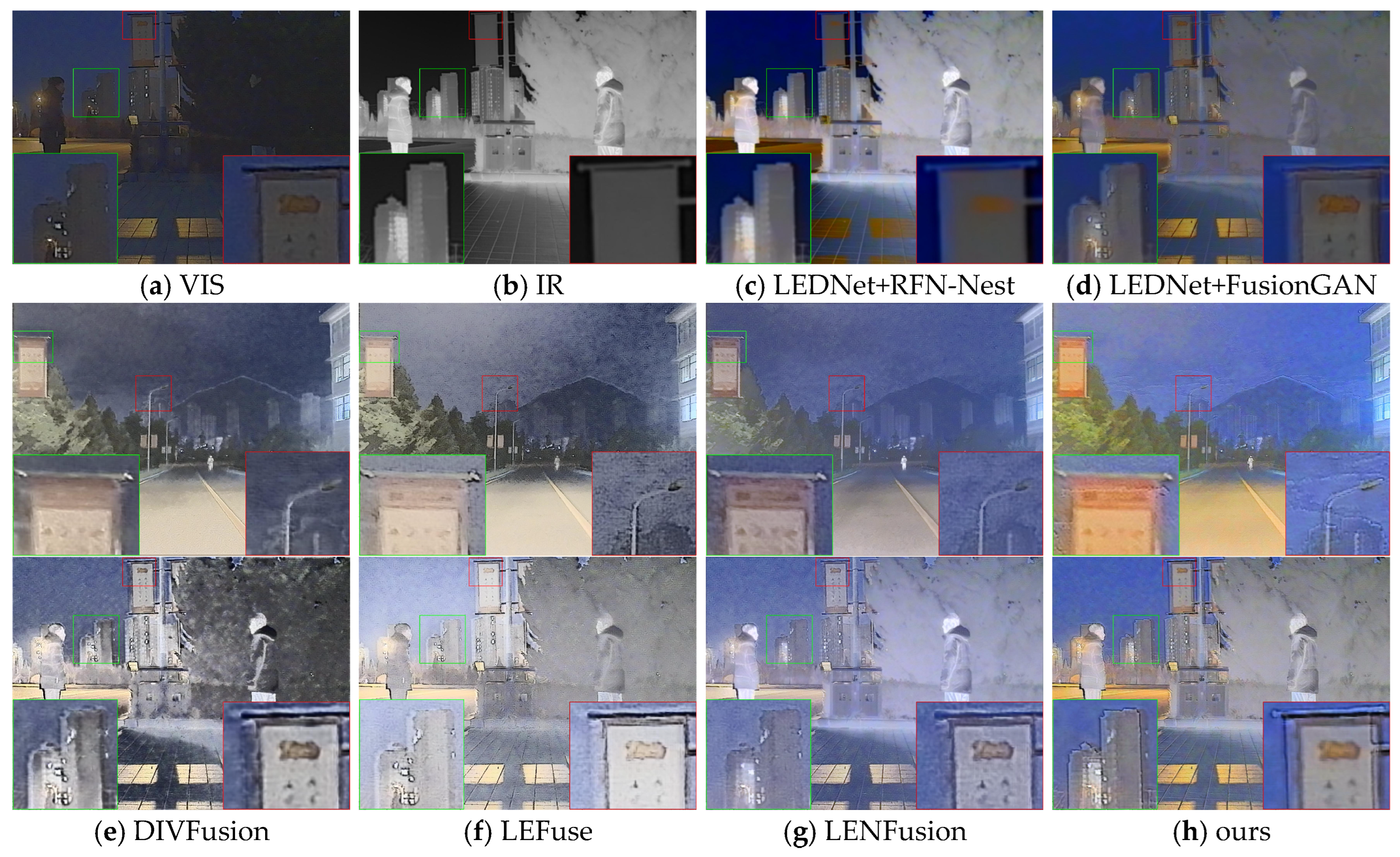

4.2.1. Qualitative Comparison

4.2.2. Quantitative Comparison

4.3. Generalization Experiment

4.3.1. Qualitative Comparison

4.3.2. Quantitative Analysis

4.4. Ablation Experiment

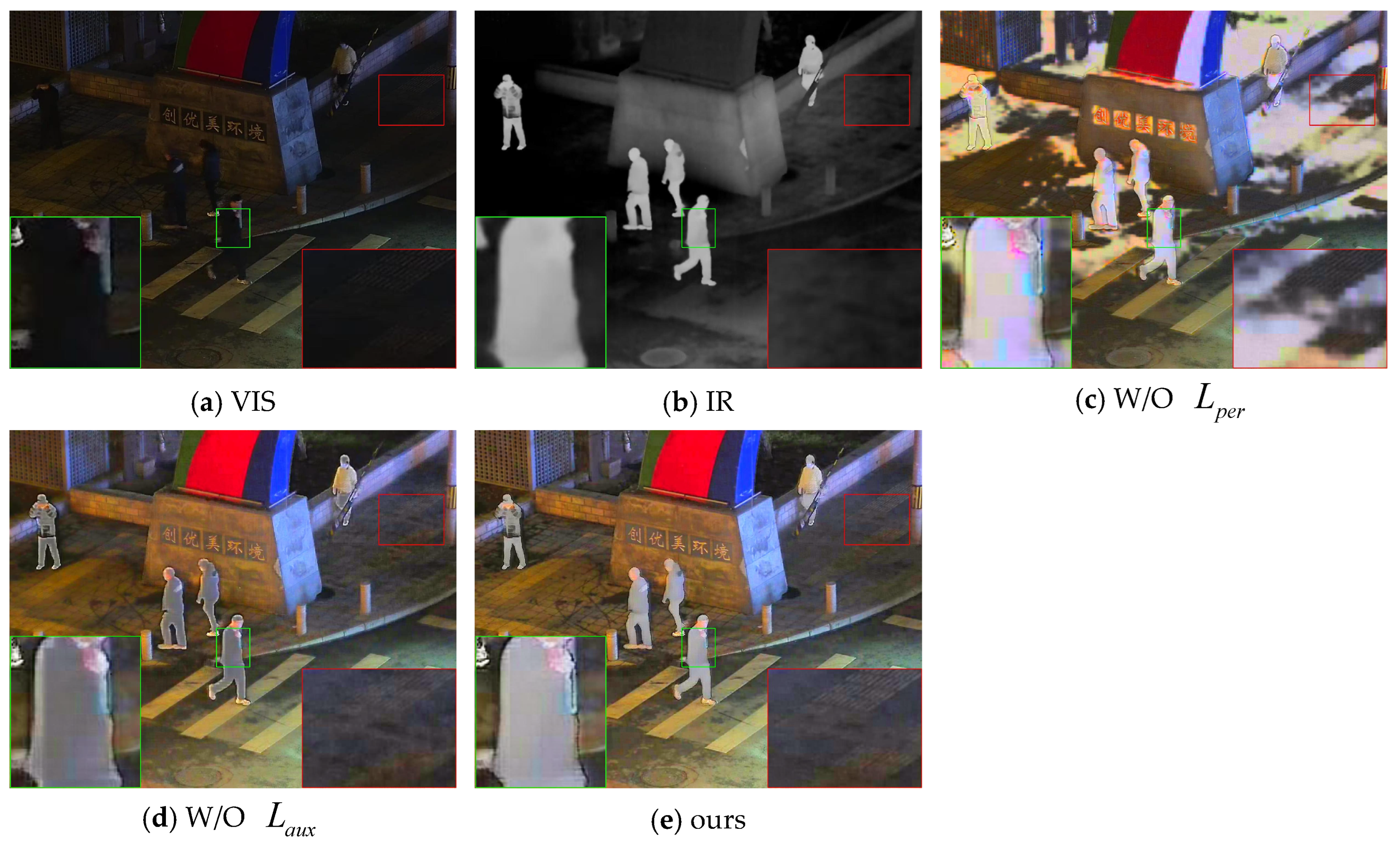

4.4.1. Qualitative Comparison

4.4.2. Quantitative Analysis

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Appendix A

- 1.

- First item;

- 2.

- Second item;

References

- Shangchen Zhou, Chongyi Li & Chen Change Loy. LEDNet: Joint Low-Light Enhancement and Deblurring in the Dark[C]//Computer Vision – ECCV 2022. 2022.

- Hao Zhang, Jiayi Ma. SDNet: A Versatile Squeeze-and-Decomposition Network for Real-Time Image Fusion[J]. International Journal of Computer Vision, 2021,Vol. 129(10): 2761-2785.

- Han Xu, Jiayi Ma, Junjun Jiang, et al. U2Fusion: A Unified Unsupervised Image Fusion Network[J]. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 2022, Vol.44(1): 502-518.

- Hui Li, Xiao-Jun Wu, Josef Kittler. RFN-Nest: An end-to-end residual fusion network for infrared and visible images[J]. Information Fusion, 2021, Vol.73: 72-86.

- Xu, Han, Zhang, et al. Classification saliency-based rule for visible and infrared image fusion.[J]. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging, 2021, Vol.7: 824-836.

- Jiayi Ma, Wei Yu, Pengwei Liang, et al. FusionGAN: A generative adversarial network for infrared and visible image fusion[J]. Information Fusion, 2019, Vol.48: 11-26.

- Jiayi Ma, Hao Zhang, Zhenfeng Shao, et al. GANMcC: A Generative Adversarial Network With Multiclassification Constraints for Infrared and Visible Image Fusion[J]. Instrumentation and Measurement, IEEE Transactions on, 2021,Vol.70: 1-14.

- Linfeng Tang, Xinyu Xiang, Hao Zhang, et al. DIVFusion: Darkness-free infrared and visible image fusion[J]. Information Fusion, 2023, Vol.91: 477-493.

- Jun Chen, Liling Yang, Wei Liu, et al. LENFusion: A Joint Low-Light Enhancement and Fusion Network for Nighttime Infrared and Visible Image Fusion[J]. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 2024, Vol.73: 1-15.

- Linfeng Tang, Jiteng Yuan, Hao Zhang, et al. PIAFusion: A progressive infrared and visible image fusion network based on illumination aware[J]. Information Fusion, 2022, Vol.83: 79-92.

- Cheng, MuhangCAa, Huang, et al. LEFuse: Joint low-light enhancement and image fusion for nighttime infrared and visible images[J]. Neurocomputing, 2025, Vol.626: 129592.

- Jia, Xinyu, Zhu, et al. LLVIP: A Visible-infrared Paired Dataset for Low-light Vision[C]//18th IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, ICCVW 2021. 2021.

- Liu, Jinyuan, Fan, et al. Target-aware Dual Adversarial Learning and a Multi-scenario Multi-Modality Benchmark to Fuse Infrared and Visible for Object Detection[C]//2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2022.

- MA J Y, TANG L F, XU M L, et al. STDFusionNet: an infrared and visible image fusion network based on salient target detection[J]. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 2021, 70: 1-13.

- Liu Y, Chen X, Ward R K, et al. Image fusion with convolutional sparse representation[J]. IEEE signal processing letters, 2016, 23(12): 1882-1886.

- LI H, WU X J, KITTLER J. Infrared and visible image fusion using a deep learning framework[C]// 2018 24th International Conference on Pattern Recognition(ICPR). 2018:2705-2710.

- LI H, WU X J, DURRANI T S. Infrared and visible image fusion with ResNet and zero-phase component analysis[J].Infrared Physics & Technology, 2019, 102:103039.

- LI H, WU X J. DenseFuse: a fusion approach to infrared and visible images[J]. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 2019, 28(5): 2614-2623.

- XU H, GONG M Q, TIAN X, et al. CUFD: an encoderdecoder network for visible and infrared image fusion based on common and unique feature decomposition[J]. Computer Vision and Image Understanding, 2022, 218: 103407.

- XU H, LIANG P W, YU W, et al. Learning a generative model for fusing infrared and visible images via conditional generative adversarial network with dual discriminators[C]// Proceedings of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Macao, China, Aug 10-16, 2019: 3954-3960.

| In channels | Out channels | Kernel size | stride | padding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 1 | 64 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| C2 | 64 | 128 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| C3 | 128 | 256 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| C4 | 256 | 512 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| SF | CC | Nabf | Qabf | SCD | MS-SSIM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFN-Nest | 5.0344 | 0.5824 | 0.0099 | 0.3332 | 1.0923 | 0.7730 |

| FusionGAN | 6.7466 | 0.6479 | 0.0124 | 0.2788 | 0.9159 | 0.8188 |

| DIVFusion | 14.7371 | 0.6922 | 0.1364 | 0.3823 | 1.5373 | 0.7973 |

| LEFuse | 24.0328 | 0.6087 | 0.1856 | 0.3006 | 1.2262 | 0.7027 |

| LENFusion | 21.4990 | 0.5928 | 0.1969 | 0.3534 | 1.0440 | 0.7236 |

| ours | 17.6531 | 0.6619 | 0.1075 | 0.4279 | 1.2760 | 0.8335 |

| SF | CC | Nabf | Qabf | SCD | MS-SSIM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFN-Nest | 4.1495 | 0.6260 | 0.0039 | 0.3133 | 0.9690 | 0.8565 |

| FusionGAN | 6.2380 | 0.6579 | 0.0143 | 0.2770 | 0.7082 | 0.8788 |

| DIVFusion | 14.4927 | 0.7360 | 0.1525 | 0.3684 | 1.6140 | 0.8276 |

| LEFuse | 20.6205 | 0.6623 | 0.2416 | 0.2504 | 1.2501 | 0.7236 |

| LENFusion | 14.6193 | 0.6640 | 0.1402 | 0.3637 | 0.9860 | 0.8011 |

| ours | 16.4501 | 0.6879 | 0.1251 | 0.3694 | 1.0070 | 0.8416 |

| SF | CC | Nabf | Qabf | SCD | MS-SSIM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W/O | 17.7592 | 0.209 | 0.0868 | 0.4103 | 0.1861 | 0.6925 |

| W/O | 15.3465 | 0.6607 | 0.0957 | 0.4169 | 1.242 | 0.8699 |

| ours | 17.6531 | 0.6619 | 0.1075 | 0.4279 | 1.276 | 0.8335 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).