1. Introduction

Pain remains one of the most prevalent and disabling clinical syndromes globally, with epidemiological surveys estimating that roughly 20% of the population experiences chronic pain at any given time, rendering it a leading source of disability and health-care burden [

1,

2]. The same data are correct for pediatric population [

3]. Despite advances in pathophysiology [

4,

5], pharmacotherapy, behavioral interventions, and rehabilitation, accurate phenotyping, mechanism-based stratification, and durable therapeutic efficacy remain elusive. The multidimensional character of pain, encompassing nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic components, compounds the challenge [

6]. Moreover, the subjective nature of pain perception limits the capacity of traditional self-report scales to fully capture its underlying neurophysiological landscape [

4,

7].

In this evolving context, clinical engineering has emerged as a potent enabler bridging biophysical innovation and clinical pain care [

8]. Defined as the translation of engineering methodologies into the clinical milieu, it encompasses device development, computational modeling, sensor systems, and digital health architectures tailored to patient care. In pain medicine, its impact can be delineated across three interlinked domains: assessment, therapy, and monitoring.

Assessment has been invigorated by wearable sensor technologies offering continuous, real-world capture of physiological proxies associated with pain [

9]. A recent scoping review identified 24 studies deploying smartwatches, wristbands, and multisensor platforms to monitor heart rate, HR variability, electrodermal activity, surface electromyography, skin temperature, and accelerometry in relation to pain fluctuations [

10]. These signals reflect autonomic, muscular, and neural dynamics, although they are correlates, not direct measures of pain itself, and must complement rather than replace self-reported assessments. Furthermore, emerging studies in chronic pain prediction via wearables suggest that models combining multimodal sensor inputs can forecast pain exacerbations [

11], although data standardization, security, ethics aspects and generalizability remain critical barriers [

12].

Therapeutic advances driven by engineering are most conspicuous in neuromodulation, where closed-loop systems now supplant older fixed (open-loop) designs [

13]. In spinal cord stimulation (SCS), real-time feedback from evoked compound action potentials (ECAPs) permits modulation of amplitude according to electrode-tissue distance and posture, thereby reducing overstimulation and improving consistency of therapy [

14]. Clinical trials show that ECAP-controlled closed-loop SCS yields better pain control and patient preference compared to open-loop systems [

15]. In parallel, the general field of closed-loop neural interfaces (spanning dorsal root ganglion, brain stimulation, peripheral nerve stimulation) is now advancing from animal models into human pilot studies, offering temporally precise and adaptive modulation of nociceptive circuits [

16]. Personalized stimulation strategies, based on hybrid biomarkers (anatomical, functional, electrophysiological), are gaining traction as next-generation paradigms [

17]. Beyond electrical stimulation, novel modalities such as focused ultrasound targeting the spinal cord have demonstrated analgesic effects and modulation of neuroinflammation in preclinical neuropathic pain models, offering a noninvasive adjunct to current device-based therapies [

18,

19].

Monitoring and prognostication represent a third frontier in which clinical engineering exerts influence via digital health and artificial intelligence (AI). Remote patient monitoring (RPM) platforms now integrate sensor-derived physiological streams with device telemetry, enabling continuous oversight of patient status [

8,

20]. AI models can detect deviations, adapt therapy parameters, and predict device faults such as lead migration or battery depletion; thereby reducing interruptions in care [

21,

22]. In pain medicine, a proposed roadmap for AI delineates phases of problem definition, algorithm development, validation, and clinical deployment, with special attention to data heterogeneity, clinical interpretability, and ethical safeguards [

12,

23].

The confluence of clinical engineering and pain medicine is ushering a paradigm shift: from subjective, episodic care toward mechanism-guided, personalized, and adaptive management. Wearable sensor systems enrich phenotyping; closed-loop neuromodulation refines therapy precision; AI-driven monitoring enables continuous adaptation. Nonetheless, challenges remain. Validation across diverse populations, regulatory pathways for implantable adaptive devices, interoperability of health data ecosystems, and clinician-engineer collaboration for translational integration are still there and should find evidence-based solutions. With careful attention to these obstacles, the synergy of engineering and medicine holds the promise of reshaping the future of pain care.

This narrative review has the aim to clarify what is available now, what we should trust and where the future scientific interests should be addressed.

2. Methods

This narrative review was conducted in accordance with the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) guidelines, ensuring methodological transparency, scientific rigor, and balanced synthesis of the available evidence [

24]. A comprehensive literature search was performed in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases, covering the period from January 2018 to September 2025. The search strategy combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms, including: “pain medicine”, “clinical engineering”, “wearable sensors”, “neuromodulation”, “biomedical imaging”, “artificial intelligence”, “rehabilitation robotics”, and “digital health”. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were applied to ensure a comprehensive retrieval of relevant studies. Selection criteria were predetermined to identify high-quality studies with direct applicability to engineering innovations in pain medicine, as detailed in

Table 1.

The selection process was carried out independently by three reviewers (MLGL, TVY, PVP), with disagreements resolved through discussion. This structured methodology ensured that the review was focused, comprehensive, and reflective of the most relevant and recent evidence at the intersection of clinical engineering and pain medicine.

3. Results

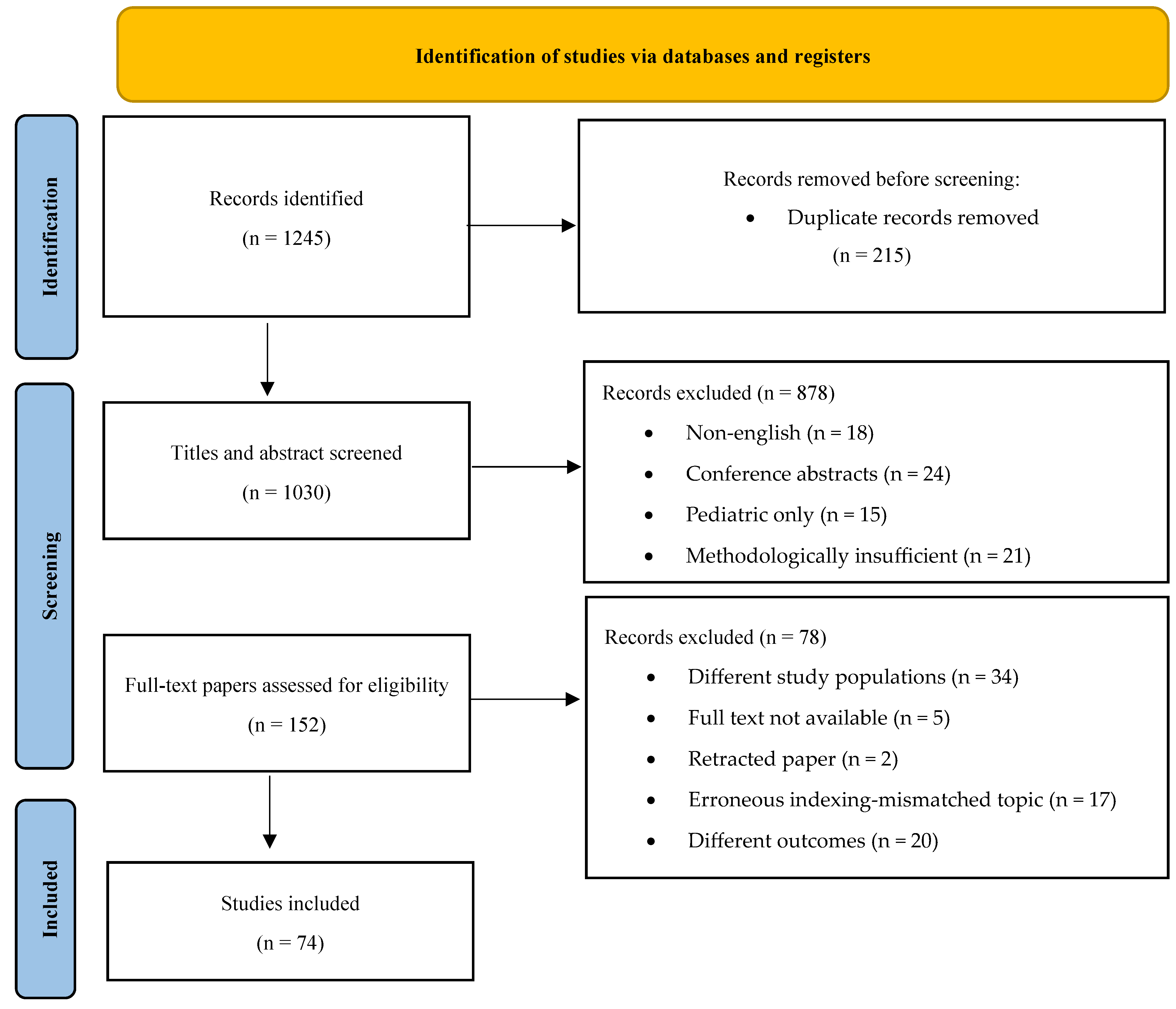

A comprehensive search retrieved 1245 records. After removing 215 duplicates, 1030 records remained for title and abstract screening. Of these, 878 were excluded as they did not meet the eligibility criteria. The full text of 152 articles was assessed, and 78 were excluded due to reasons such as study design, insufficient data, or irrelevance to the study aim. Ultimately, 74 studies were included in the review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process.

3.1. Advances in Pain Assessment through Clinical Engineering

The longstanding reliance on subjective self-report scales such as the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) limits the specificity and objectivity of pain assessment. Such scales capture only the patient’s snapshot perception rather than the dynamic, multidimensional nature of pain. Clinical engineering is helping to bridge this gap, ushering in an era of objective, multimodal assessment that augments (and in some contexts may partly substitute for) self-report.

First, wearable devices and sensors have become increasingly sophisticated and miniaturized. Inertial measurement units (IMUs) embedded in wearables capture movement, posture, and gait metrics [

8,

25]. Surface electromyography (sEMG) monitors muscle activation associated with pain-driven guarding or tension [

8,

26]. Skin conductance sensors (electrodermal activity) index sympathetic arousal during nociceptive events [

27]. A recent scoping review of wearable and passive sensors in chronic pain identified 60 relevant studies, highlighting the promise of continuous, real-world behavioral and physiological monitoring (e.g. accelerometry, heart rate variability, skin conductance) in pain populations [

28]. In another recent study, wristwatch sensors detecting acceleration and pulse-rate changes were able to discriminate moderate abdominal pain episodes (NRS ≥ 4) in ambulatory settings, underscoring the feasibility of such approaches in everyday life [

29]. These wearable data streams can feed into algorithms that detect fluctuations or flare-ups, enabling more timely clinical insight.

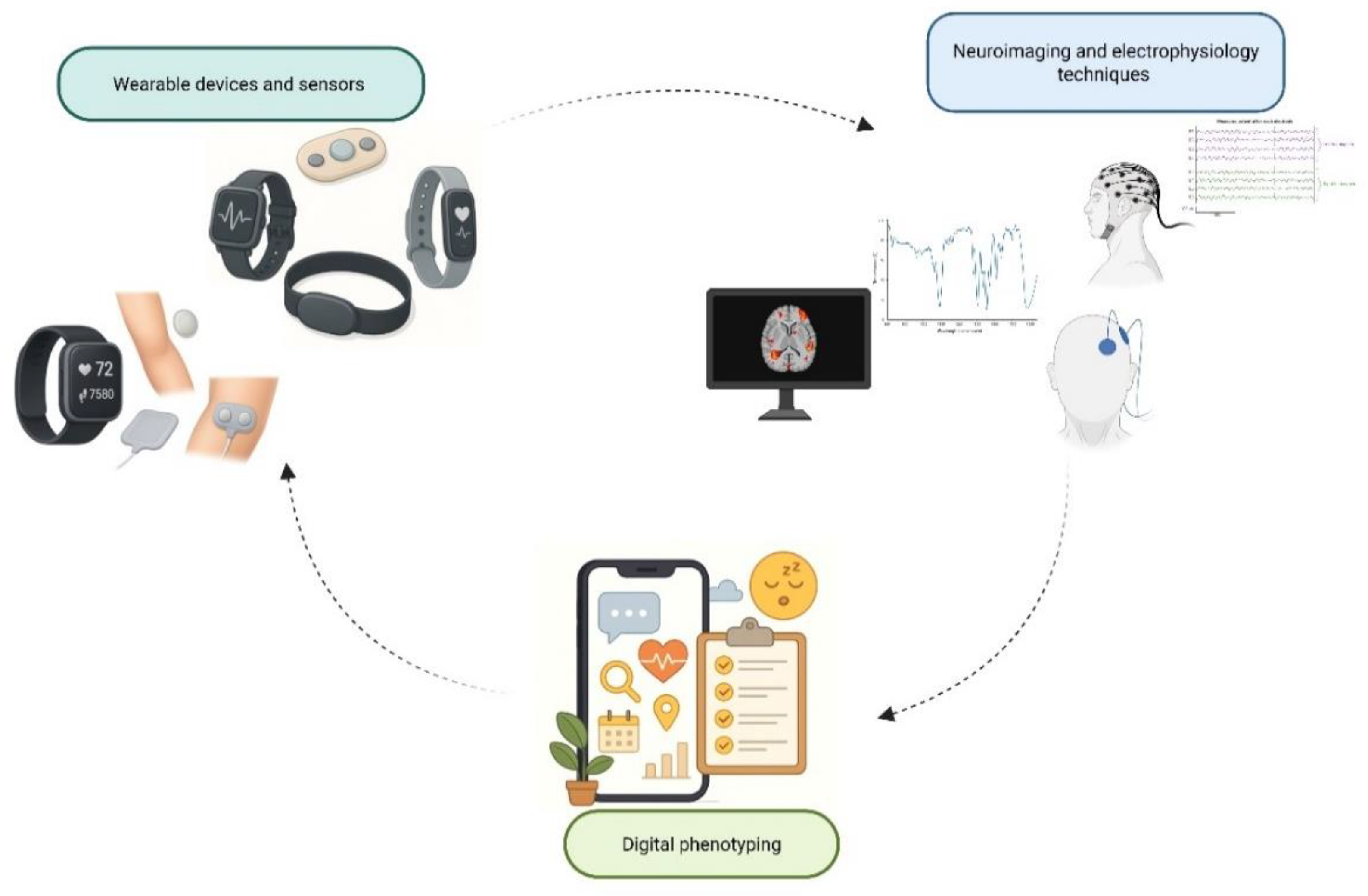

Second, neuroimaging and electrophysiology techniques provide windows into central pain mechanisms. Functional MRI (fMRI) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) allow assessment of cerebral hemodynamic responses linked to pain processing; for example, a 2025 study using resting-state fNIRS and logistic regression could classify pain severity in cancer patients [

30]. Advanced reviews in neuroimaging emphasize candidate neural biomarkers (connectivity, activation patterns) for acute and chronic pain states [

31]. On the electrophysiology side, quantitative EEG studies in chronic pain populations often report elevated theta and alpha power, and newer work correlates beta/gamma oscillatory components with pain intensity (e.g. in low back pain) [

32]. Emerging brain-computer interface (BCI) frameworks aim to decode nociceptive signatures in real time, potentially supporting closed-loop neuromodulation [

33].

Third, the paradigm of digital phenotyping exploits ubiquitous devices like smartphones to capture behavioral and contextual features, sleep/wake patterns, activity rhythms, geolocation, ecological momentary assessments (EMAs), and app-based symptom diaries [

34]. When integrated with AI, these data may reveal latent correlations among behavior, environment, and pain fluctuations [

21]. For instance, wearable polysomnography combined with machine learning has been used to interrogate sleep-pain reciprocity at scale, enabling longitudinal insights into how nocturnal disturbances influence next-day pain [

35]. Together, these three pillars (wearables, neuroimaging/electrophysiology, and digital phenotyping) are constructing a richer, more objective portrait of pain dynamics. Yet, challenges remain, including sensor fidelity, signal artifacts, interpretability of algorithms, and integration with clinical workflows.

Figure 2 summarizes the three emerging pillars in objective pain assessment: wearable devices and sensors, neuroimaging and electrophysiology, and digital phenotyping, highlighting their integration in capturing multidimensional pain dynamics.

3.2. Engineering-Supported Therapeutics in Pain Medicine

Clinical engineering is fostering a new generation of therapeutic modalities in pain medicine, transforming how clinicians may intervene in chronic and complex pain states. Among these, neuromodulation stands at the vanguard. Modern systems in SCS, dorsal root ganglion stimulation (DRG-S), and noninvasive techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) increasingly embed adaptive, closed-loop feedback architectures. In SCS, the use of ECAPs as real-time sensory feedback enables continuous adjustment of stimulation amplitude to compensate for postural changes or electrode displacement, thereby minimizing overstimulation and optimizing consistency of dose [

14,

15]. Clinical trials and observational studies (e.g., EVOKE, Avalon) have demonstrated that ECAP-controlled closed-loop SCS leads to superior responder rates and patient preference over traditional open-loop systems [

36]. Moreover, early outcomes in flexible ECAP-based closed-loop settings report reduced variability in neural activation and improved comfort during activities of daily living [

37]. Device miniaturization, low-power electronics, and improved electrode designs have concurrently improved energy efficiency and implantation ergonomics.

In parallel, rehabilitation robotics is evolving to address pain associated with musculoskeletal disorders. Exoskeletons and robotic assistive devices support repetitive, controlled movement to rehabilitate deconditioned muscle groups and correct dysfunctional biomechanics [

38]. Robotic systems now integrate haptic feedback, precision actuation, and AI-guided personalization of therapy protocols based on patient performance [

39]. A recent systematic review of robotic technologies in motor rehabilitation highlights both the promise and the engineering challenges (actuation, control, safety) in translating to pain populations [

40]. Scoping reviews in pain treatment note that although results are preliminary, robots may serve as adjuncts in chronic pain management, especially when integrated with sensor feedback and adaptive algorithms [

41].

Furthermore, clinical engineering is advancing drug delivery systems toward greater specificity and control. Implantable pumps for intrathecal analgesia have benefited from improved control electronics, smaller form factors, and safer reservoir systems [

42]. Simultaneously, nanotechnology-based carriers (liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and smart responsive vehicles) are being investigated for targeted analgesic delivery, prolonged release, and reduced systemic side effects [

43]. Reviews in nanomedicine for pain emphasize how engineered nanosystems can modulate pharmacokinetics, mitigate off-target toxicity, and potentially deliver therapeutics to peripheral nerves or spinal targets [

44]. For example, recent work in nanotechnology for pain management catalogues emerging designs that integrate stimuli-responsive release or targeted ligands in analgesic nanoformulations [

45].

Together, these engineering-driven therapies envision a synergistic ecosystem: wearable sensors detect pain states and triggers, AI algorithms stratify which patients will benefit, closed-loop neuromodulation delivers adaptive therapy, rehabilitation robotics supports functional recovery, and smart drug delivery complements electrical interventions (

Table 2). The convergence of these modalities has the potential to shift pain care from symptomatic suppression toward mechanism-guided, multimodal, adaptive therapy. Future work must address rigorous clinical validation, device safety, algorithm transparency, long-term durability, and integration across engineering and clinical pathways.

3.3. Clinical Engineering in Pain Monitoring and Prognostication

Monitoring the evolution of pain and the response to treatment is indispensable to truly personalized care, and clinical engineering now supplies the digital scaffolding to do this continuously and at scale. Telemedicine and remote monitoring platforms increasingly integrate wearable streams (accelerometry, heart-rate variability, electrodermal activity) with patient-reported outcomes to create longitudinal “digital trajectories” of pain [

46]. Recent reviews show that wearable-enabled telehealth can sustain engagement, reduce in-person visits, and support timely therapy adjustments, particularly when combined with structured education and coaching workflows [

47]. In neuromodulation, device telemetry and remote programming add a further layer: contemporary spinal cord stimulation ecosystems report bidirectional data flow that supports troubleshooting (e.g., lead issues, battery status) and proactive parameter optimization between clinic visits [

48].

On the analytics side, machine learning models trained on multimodal inputs (sensor data, neuroimaging or neurophysiology, EHR variables, and medication history) are being used to forecast treatment response, risk of transition from acute to chronic pain, and postsurgical chronic pain phenotypes. Recent systematic and methodological reviews document rapid growth in such applications, ranging from predicting chronic postsurgical pain to anticipating opioid use, while underscoring variability in feature sets and the need for external validation and transparent reporting [

49]. In real-world service models, app-derived behavioral and symptom data have been used to predict clinically meaningful improvements, illustrating how remote patient monitoring can be coupled to adaptive care pathways [

50].

Finally, clinical decision-support systems (CDSS) operationalize these insights at the bedside by integrating multimodal data within the EHR to prompt mechanism-informed choices (e.g., analgesic selection, referral to interventional therapies, or non-pharmacological programs). Early evaluations of pain-focused CDSS and implementation studies in primary care indicate potential benefits but also highlight prerequisites (governance, workflow fit, and algorithmic transparency) to avoid alert fatigue and bias [

51].

Taken together, wearable-enabled telemedicine, predictive modeling, and EHR-embedded decision support form a cohesive monitoring framework. This framework shifts pain care from episodic, retrospective assessment to prospective, data-driven adaptation, provided that future work strengthens external validation, equity, interoperability, and clinician-patient interpretability [

47].

4. Discussion

The alliance between pain medicine and clinical engineering is not merely incremental, it is reconfiguring the landscape of pain care. The promise is evident: objective biomarkers, adaptive closed-loop neuromodulation, and AI-assisted decision support coalesce to shift pain management from a heuristic, trial-and-error model to a precision medicine paradigm. But realizing that promise demands engaging three pressing challenges: validation and standardization, ethical and regulatory hurdles, and interdisciplinary training. Each of them both tempers and frames future progresses.

Validation and standardization represent a fundamental hurdle. While multiple sensor systems, biomarker algorithms, and neuromodulation devices have been proposed, many remain validated only under narrowly defined populations or controlled lab settings. For example, many wearable pain models are trained on homogeneous cohorts and may fail to generalize across age, sex, comorbidities, or ethnic groups. In neuromodulation research, biases in study design, especially in device trials sponsored by industry, further complicate conclusions about efficacy and generalizability. Desai et al. [

52] specifically examined biases (conflicts of interest, selection bias, and publication bias) in neuromodulation studies on chronic pain, urging rigorous mitigation strategies. Without harmonized protocols, cross-platform calibration, and robust multicenter studies, adoption at scale remains precarious.

Ethical and regulatory considerations remain a major challenge [

12]. The aggregation of continuous patient data (physiology, behavior, neural signals) raises deep questions of privacy, data ownership, and consent. Algorithms trained on historical data can perpetuate or exacerbate biases: AI decision-support systems may inadvertently disadvantage underrepresented groups unless fairness and transparency are baked in. In one randomized trial of AI guidance in chest pain triage, physicians accepted AI suggestions and improved decision accuracy, but such systems must be scrutinized for bias in clinical domains including pain medicine [

53]. On the regulatory front, the evolving landscape, especially with forthcoming legislation such as the European AI Act, complicates qualification of deep learning-based medical device components (for example, in neuromodulation or imaging analytics). Zanon et al. [

54] highlighted the uncertainties in qualifying DL systems under Class III device regulation, especially around dataset governance, explainability, and post-deployment monitoring.

Finally, interdisciplinary training is indispensable. Pain physicians accustomed to pharmacologic, interventional, and rehabilitative modalities may lack the engineering literacy to interpret sensor data, understand control algorithms, or evaluate AI model validity [

21,

55]. Conversely, engineers designing devices may underappreciate the pathophysiological subtleties, placebo effects, or clinical constraints of pain care [

20,

56]. Without structured cross-training, the translational chasm may persist. Integrated curricula, collaborative labs, and translational “sandboxes” are needed to cultivate fluent bilingual professionals. Yet, even in the face of these obstacles, clinical engineering offers powerful levers for deconvolving pain’s complexity. By aligning objective measurement with therapeutic feedback loops and data-guided decision frameworks, it is possible to begin mapping subjective experience onto mechanistic substrates. The journey is not trivial, but with concerted attention to validation, ethics, regulation, and education, the synergy between engineering and medicine can turn the aspiration of precision pain care into a practical reality [

57].

Limitations: This narrative review has several limitations. First, although a structured literature search was performed, the absence of systematic review methodology implies potential selection bias and incomplete capture of all relevant evidence. Second, heterogeneity across study designs, populations, and technological platforms limits comparability and precludes meta-analytic synthesis. Third, many of the cited innovations remain in early translational stages, with limited validation in large, diverse clinical cohorts. Finally, rapid technological progress may render some findings time sensitive. These constraints should be considered when interpreting the conclusions and their generalizability to broader pain medicine practice.

4. Conclusions

Clinical engineering represents a transformative force in pain medicine, fostering objective assessment, innovative therapeutics, and continuous monitoring. These advances lay the foundation for individualized, mechanism-based approaches to pain management. Future research must focus on standardization, ethical integration, and cost-effectiveness analysis, ensuring that these technologies are accessible and equitably distributed. The collaboration between pain physicians, engineers, and data scientists will define the next era of pain medicine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.V.; methodology, G.V., M.L.G.L., J.V.P., O.V.; data curation, G.V., M.L.G.L., A.A., and A.A.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, G.V., M.L.G.L., C.G., A.A., A.A.A.A., T.E., J.V.P., O.V., TVY, PVP, and G.F.; writing—review and editing, M.L.G.L., G.F., M.M., and A.C.; supervision, G.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the Fondazione Paolo Procacci for their invaluable support and assistance throughout the publication process and valuable discussions. We are also grateful to John Shaw for his assistance with the English revision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| BCI |

Brain-Computer Interface |

| CDSS |

Clinical Decision Support System |

| DRG-S |

Dorsal Root Ganglion Stimulation |

| ECAP |

Evoked Compound Action Potential |

| EEG |

Electroencephalography |

| EHR |

Electronic Health Record |

| EMA |

Ecological Momentary Assessment |

| fMRI |

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| fNIRS |

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy |

| IMU |

Inertial Measurement Unit |

| NRS |

Numeric Rating Scale |

| RPM |

Remote Patient Monitoring |

| SANRA |

Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles |

| SCS |

Spinal Cord Stimulation |

| sEMG |

Surface Electromyography |

| TMS |

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation |

| VAS |

Visual Analog Scale |

References

- Latina R, Varrassi G, Di Biagio E, Giannarelli D, Gravante F, Paladini A, D'Angelo D, Iacorossi L, Martella C, Alvaro R, Ivziku D, Veronese N, Barbagallo M, Marchetti A, Notaro P, Terrenato I, Tarsitani G, De Marinis MG. Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in a Tertiary Pain Clinic Network: a Retrospective Study. Pain Ther. 2023 Feb;12(1):151-164. Epub 2022 Oct 17. Erratum in: Pain Ther. 2023 Jun;12(3):891-892. doi: 10.1007/s40122-023-00503-3. [CrossRef]

- Latina R, De Marinis MG, Giordano F, Osborn JF, Giannarelli D, Di Biagio E, Varrassi G, Sansoni J, Bertini L, Baglio G, D'Angelo D, Baldeschi GC, Piredda M, Carassiti M, Camilloni A, Paladini A, Casale G, Mastroianni C, Notaro P; PRG, Pain Researchers Group into Latium Region; Diamanti P, Coaccioli S, Tarsitani G, Cattaruzza MS. Epidemiology of Chronic Pain in the Latium Region, Italy: A Cross-Sectional Study on the Clinical Characteristics of Patients Attending Pain Clinics. Pain Manag Nurs. 2019 Aug;20(4):373-381. [CrossRef]

- Lo Cascio A, Cascino M, Dabbene M, Paladini A, Viswanath O, Varrassi G, Latina R. Epidemiology of Pediatric Chronic Pain: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2025 Apr 1;29(1):71. [CrossRef]

- Asimakopoulos T, Tsaroucha A, Kouri M, Pasqualucci A, Varrassi G, Leoni MLG, Rekatsina M. The Role of Biomarkers in Acute Pain: A Narrative Review. Pain Ther. 2025 Jun;14(3):775-789. [CrossRef]

- Varrassi G, Leoni MLG, Farì G, Al-Alwany AA, Al-Sharie S, Fornasari D. Neuromodulatory Signaling in Chronic Pain Patients: A Narrative Review. Cells. 2025 Aug 27;14(17):1320. [CrossRef]

- Vickery S, Junker F, Döding R, Belavy DL, Angelova M, Karmakar C, Becker L, Taheri N, Pumberger M, Reitmaier S, Schmidt H. Integrating multidimensional data analytics for precision diagnosis of chronic low back pain. Sci Rep. 2025 Mar 20;15(1):9675. [CrossRef]

- Manda O, Hadjivassiliou M, Varrassi G, Zavridis P, Zis P. Exploring the Role of the Cerebellum in Pain Perception: A Narrative Review. Pain Ther. 2025 Jun;14(3):803-816. [CrossRef]

- Varrassi G, Leoni MLG, Al-Alwany AA, Sarzi Puttini P, Farì G. Bioengineering Support in the Assessment and Rehabilitation of Low Back Pain. Bioengineering (Basel). 2025 Aug 22;12(9):900. [CrossRef]

- Tamura T. Advanced Wearable Sensors Technologies for Healthcare Monitoring. Sensors (Basel). 2025 Jan 8;25(2):322. [CrossRef]

- Semiz B, Hancioglu ÖK, Şahin RS. Pain assessment and determination methods with wearable sensors: a scoping review. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2025 Sep 24. [CrossRef]

- Ayena JC, Bouayed A, Ben Arous M, Ouakrim Y, Loulou K, Ameyed D, Savard I, El Kamel L, Mezghani N. Predicting chronic pain using wearable devices: a scoping review of sensor capabilities, data security, and standards compliance. Front Digit Health. 2025 May 22;7:1581285. [CrossRef]

- Pergolizzi JV Jr, LeQuang JAK, El-Tallawy SN, Varrassi G. What Clinicians Should Tell Patients About Wearable Devices and Data Privacy: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2025 Mar 25;17(3):e81167. [CrossRef]

- Herbozo Contreras LF, Truong ND, Eshraghian JK, Xu Z, Huang Z, Bersani-Veroni TV, Aguilar I, Leung WH, Nikpour A, Kavehei O. Neuromorphic neuromodulation: Towards the next generation of closed-loop neurostimulation. PNAS Nexus. 2024 Oct 30;3(11):pgae488. [CrossRef]

- Nijhuis H, Kallewaard JW, van de Minkelis J, Hofsté WJ, Elzinga L, Armstrong P, Gültuna I, Almac E, Baranidharan G, Nikolic S, Gulve A, Vesper J, Dietz BE, Mugan D, Huygen FJPM. Durability of Evoked Compound Action Potential (ECAP)-Controlled, Closed-Loop Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS) in a Real-World European Chronic Pain Population. Pain Ther. 2024 Oct;13(5):1119-1136. [CrossRef]

- Mangano N, Torpey A, Devitt C, Wen GA, Doh C, Gupta A. Closed-Loop Spinal Cord Stimulation in Chronic Pain Management: Mechanisms, Clinical Evidence, and Emerging Perspectives. Biomedicines. 2025 Apr 30;13(5):1091. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Chen ZS. Closed-loop neural interfaces for pain: Where do we stand? Cell Rep Med. 2024 Oct 15;5(10):101662. [CrossRef]

- Carè M, Chiappalone M, Cota VR. Personalized strategies of neurostimulation: from static biomarkers to dynamic closed-loop assessment of neural function. Front Neurosci. 2024 Mar 7;18:1363128. [CrossRef]

- Soliman N, Moisset X, Ferraro MC, de Andrade DC, Baron R, Belton J, Bennett DLH, Calvo M, Dougherty P, Gilron I, Hietaharju AJ, Hosomi K, Kamerman PR, Kemp H, Enax-Krumova EK, McNicol E, Price TJ, Raja SN, Rice ASC, Smith BH, Talkington F, Truini A, Vollert J, Attal N, Finnerup NB, Haroutounian S; NeuPSIG Review Update Study Group. Pharmacotherapy and non-invasive neuromodulation for neuropathic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2025 May;24(5):413-428. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen R, El-Hajj VG, Battistin U, Habashy KJ, Staartjes VE, Elmi-Terander A, Zhang J, Ghaith AK. Potential applications of focused ultrasound for spinal cord diseases: a narrative review of preclinical studies. Brain Spine. 2025 Jun 13;5:104298. [CrossRef]

- Flavin MT, Foppiani JA, Paul MA, Alvarez AH, Foster L, Gavlasova D, Ma H, Rogers JA, Lin SJ. Bioelectronics for targeted pain management. Nature Rev Electr Engin. 2025 May 22:1-8. [CrossRef]

- El-Tallawy SN, Pergolizzi JV, Vasiliu-Feltes I, Ahmed RS, LeQuang JK, El-Tallawy HN, Varrassi G, Nagiub MS. Incorporation of "Artificial Intelligence" for Objective Pain Assessment: A Comprehensive Review. Pain Ther. 2024 Jun;13(3):293-317. [CrossRef]

- Cascella M, Leoni MLG, Shariff MN, Varrassi G. Towards artificial intelligence application in pain medicine. Recenti Prog Med. 2025 Mar;116(3):156-161. [CrossRef]

- Adams MCB, Bowness JS, Nelson AM, Hurley RW, Narouze S. A roadmap for artificial intelligence in pain medicine: current status, opportunities, and requirements. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2025 Oct 1;38(5):680-688. [CrossRef]

- Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S. SANRA-a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2019 Mar 26;4:5. [CrossRef]

- van Amstel RN, Dijk IE, Noten K, Weide G, Jaspers RT, Pool-Goudzwaard AL. Wireless inertial measurement unit-based methods for measuring lumbopelvic-hip range of motion are valid compared with optical motion capture as golden standard. Gait Posture. 2025 Jul;120:72-80. [CrossRef]

- Albaladejo-Belmonte M, Houston M, Dias N, Spitznagle T, Lai H, Zhang Y, Garcia-Casado J. Does Muscle Pain Induce Alterations in the Pelvic Floor Motor Unit Activity Properties in Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome? A High-Density sEMG-Based Study. Sensors (Basel). 2024 Nov 21;24(23):7417. [CrossRef]

- Kong Y, Chon KH. Electrodermal activity in pain assessment and its clinical applications. Appl Physics Rev. 2024 Sep 1;11(3). [CrossRef]

- Vitali D, Olugbade T, Eccleston C, Keogh E, Bianchi-Berthouze N, de C Williams AC. Sensing behavior change in chronic pain: a scoping review of sensor technology for use in daily life. Pain. 2024 Jun 1;165(6):1348-1360. [CrossRef]

- Hirayama H, Yoshida S, Sasaki K, Yuda E, Yoshida Y, Miyashita M. Pain detection using biometric information acquired by a wristwatch wearable device: a pilot study of spontaneous menstrual pain in healthy females. BMC Res Notes. 2025 Jan 22;18(1):31. [CrossRef]

- Shafiei SB, Shadpour S, Pangburn B, Bentley-McLachlan M, de Leon-Casasola O. Pain classification using functional near infrared spectroscopy and assessment of virtual reality effects in cancer pain management. Sci Rep. 2025 Mar 15;15(1):8954. [CrossRef]

- Zhang LB, Chen YX, Li ZJ, Geng XY, Zhao XY, Zhang FR, Bi YZ, Lu XJ, Hu L. Advances and challenges in neuroimaging-based pain biomarkers. Cell Rep Med. 2024 Oct 15;5(10):101784. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Gewandter JS, Geha P. Brain Imaging Biomarkers for Chronic Pain. Front Neurol. 2022 Jan 3;12:734821. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan R, Moger SS, Umesh S, Bhuvana GN. Revolutionizing Pain Management: The Future of AAT, BCI, Exoskeleton, and Soft Robotics. In “Unveiling Technological Advancements and Interdisciplinary Solutions for Pain Care” 2026 (pp. 129-164). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Collins JT, Walsh DA, Gladman JRF, Patrascu M, Husebo BS, Adam E, Cowley A, Gordon AL, Ogliari G, Smaling H, Achterberg W. The Difficulties of Managing Pain in People Living with Frailty: The Potential for Digital Phenotyping. Drugs Aging. 2024 Mar;41(3):199-208. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Zeitzer JM, Mackey S, Darnall BD. Revealing sleep and pain reciprocity with wearables and machine learning. Commun Med (Lond). 2025 May 7;5(1):160. [CrossRef]

- Chung M, Abd-Elsayed A. Comparative efficacy of closed-loop spinal cord stimulation and dorsal root ganglion stimulation through combination trialing for cancer pain - A retrospective case series. Pain Pract. 2025 Feb;25(2):e70010. [CrossRef]

- Mohabbati V, Sullivan R, Yu J, Georgius P, Brooker CD, Siorek M, McClelland NL, Coletti F, Sun X, Franke A, Russo MA. Early Outcomes with a Flexible ECAP Based Closed Loop Using Multiplexed Spinal Cord Stimulation Waveforms-Single-arm Study with In-clinic Randomized Crossover Testing. Pain Med. 2025 May 16:pnaf058. [CrossRef]

- Khalid S, Alnajjar F, Gochoo M, Renawi A, Shimoda S. Robotic assistive and rehabilitation devices leading to motor recovery in upper limb: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2023 Jul;18(5):658-672. [CrossRef]

- Snow P. Virtual reality and pain management: The need for clarity for future interventions. Brit J Pain. 2025 Apr;19(2):68-70. [CrossRef]

- Banyai AD, Brișan C. Robotics in Physical Rehabilitation: Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Aug 29;12(17):1720. [CrossRef]

- Higgins A, Llewellyn A, Dures E, Caleb-Solly P. Robotics Technology for Pain Treatment and Management: A Review. In: Cavallo, F., et al. Social Robotics. ICSR 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13817. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Corriero A, Giglio M, Soloperto R, Preziosa A, Stefanelli C, Castaldo M, Gloria F, Paladini A, Guardamagna VA, Puntillo F. The Missing Link: Integrating Interventional Pain Management in the Era of Multimodal Oncology. Pain Ther. 2025 Aug;14(4):1223-1246. [CrossRef]

- Kuskov AN, Kukovyakina EV, Krasnoselskaya EN. Nanotechnology-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics. 2025 Jun 24;17(7):817. [CrossRef]

- Li L, Li T, Wang H, Luo L, Cheng Y, Li Y, Huang S, Zhang X, He J, Guo J, Zhang C, Zhang F, Tang L, Xu J. Nanomedicine for chronic pain management: From pathophysiology to engineered drug delivery systems. Mater Today Bio. 2025 Jun 10;33:101976. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Yao Y, Kuang R, Chen Z, Du Z, Qu S. Global research trends of nanotechnology for pain management. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023 Aug 28;11:1249667. [CrossRef]

- Vudathaneni VKP, Lanke RB, Mudaliyar MC, Movva KV, Mounika Kalluri L, Boyapati R. The Impact of Telemedicine and Remote Patient Monitoring on Healthcare Delivery: A Comprehensive Evaluation. Cureus. 2024 Mar 4;16(3):e55534. [CrossRef]

- Patel PM, Green M, Tram J, Wang E, Murphy MZ, Abd-Elsayed A, Chakravarthy K. Beyond the Pain Management Clinic: The Role of AI-Integrated Remote Patient Monitoring in Chronic Disease Management - A Narrative Review. J Pain Res. 2024 Dec 11;17:4223-4237. [CrossRef]

- Zhong T, William HM, Jin MY, Abd-Elsayed A. A Review of Remote Monitoring in Neuromodulation for Chronic Pain Management. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2024 Dec;28(12):1225-1233. [CrossRef]

- Antel R, Whitelaw S, Gore G, Ingelmo P. Moving towards the use of artificial intelligence in pain management. Eur J Pain. 2025 Mar;29(3):e4748. [CrossRef]

- Skoric J, Lomanowska AM, Janmohamed T, Lumsden-Ruegg H, Katz J, Clarke H, Rahman QA. Predicting Clinical Outcomes at the Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service via the Manage My Pain App: Machine Learning Approach. JMIR Med Inform. 2025 Mar 28;13:e67178. [CrossRef]

- O'Hagan M, Johnson D, Lobo DN, Levy N. A clinical decision support tool for acute pain within an electronic health record to improve analgesic prescribing practice. Br J Anaesth. 2025 Apr;134(4):1238-1240. [CrossRef]

- Desai SA, Hayek SM. Bias in neuromodulation studies on chronic pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2025 Oct 1;38(5):674-679. [CrossRef]

- Goh E, Bunning B, Khoong EC, Gallo RJ, Milstein A, Centola D, Chen JH. Physician clinical decision modification and bias assessment in a randomized controlled trial of AI assistance. Commun Med (Lond). 2025 Mar 4;5(1):59. [CrossRef]

- Zonon Diaz J, Brennan T, Corcoran P. Navigating the EU AI Act: Foreseeable Challenges in Qualifying Deep Learning-Based Automated Inspections of Class III Medical Devices. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.20144. 2025 Aug 27. arXiv:2508.20144. [CrossRef]

- De Lucia A, Donisi V, Pasini I, Polati E, Del Piccolo L, Schweiger V, Perlini C. Perspectives and Experiences on eHealth Solutions for Coping with Chronic Pain: Qualitative Study Among Older People Living With Chronic Pain. JMIR Aging. 2024 Sep 5;7:e57196. [CrossRef]

- Iafrate L, Benedetti MC, Donsante S, Rosa A, Corsi A, Oreffo ROC, Riminucci M, Ruocco G, Scognamiglio C, Cidonio G. Modelling skeletal pain harnessing tissue engineering. In Vitro Model. 2022;1(4-5):289-307. [CrossRef]

- Weerarathna IN, Kumar P, Luharia A, Mishra G. Engineering with Biomedical Sciences Changing the Horizon of Healthcare-A Review. Bioengineered. 2024 Dec;15(1):2401269. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).