1. Introduction

To address the brittleness of concrete, fiber-reinforced cementitious composite (FRCC) was developed in the 1970s [

1]. Strain-hardening cementitious composite (SHCC), also known as engineered cementitious composite (ECC), is a special type of FRCC that achieves ultimate tensile strains of 3%–8% and multiple micro-cracking characteristics by optimizing matrix composition, enhancing fiber performance, and improving the fiber-matrix interface. This far exceeds the 0.02% ultimate tensile strain of conventional concrete, with tensile ductility more than 300 times that of plain concrete [2, 3]. In the strain-hardening stage, the crack width of SHCC can be controlled below 100 μm. The compressive strength of conventional SHCC ranges from 30–80 MPa, while high-strength SHCC can exceed 100 MPa with tensile strains up to 11% [

4].

Compared to cast SHCC, sprayed SHCC enables rapid construction through high-speed spraying and can be categorized as dry-mix or wet-mix depending on the material-adding sequence [5, 6]. This technology replaces steel mesh with fiber, significantly improving construction efficiency and expanding applications in structural repair, slope reinforcement, and other fields. Studies have shown that applying sprayed SHCC in masonry retrofitting can enhance the shear strength of composite structures by 4.5–7 times [7, 8] and limit maximum crack widths in beams to below 0.45 mm [

9]. However, the spraying process causes fibers to orient parallel to the spraying direction with some loss before hitting the substrate surface, leading to lower fiber volume fractions compared to cast SHCC [10-12]. Additionally, sprayed SHCC requires a balance between low plastic viscosity (to reduce pumping friction) and high yield stress (to minimize rebound) to achieve the desired buildup thickness on the substrate surface [13, 14]. Current research focuses on improving sprayability through admixture incorporation and mixture optimization, with experiments showing optimal sprayability at a yield stress of 92–119 Pa and plastic viscosity of 4.9–7.2 Pa·s [14-17]. Like cast SHCC, sprayed SHCC also shows strain-hardening behavior, making it suitable for structural repair and strengthening, especially in tension or flexural components. However, the spraying process can significantly affect fiber distribution [

18]. Moreover, the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the sprayed layer and substrate is often the weakest part due to high porosity [

19]. The bond performance between sprayed SHCC and the substrate is affected by substrate roughness, surface moisture, curing methods, and overlay thickness [

20]. Studies have shown that an overly dry substrate leads to significant shrinkage and cracking of the sprayed SHCC layer, so it is recommended that the single-layer spraying thickness not exceed 25 mm to prevent delamination [

21]. Discrete crack models reveal that a 10 mm thick SHCC overlay can induce multiple cracks at the interface between the overlay and substrate, while a 30 mm thick overlay can increase wall shear strength by 4.65 times [

22].

Although existing reviews have summarized the material design, durability, and multi-scale modeling of fiber pullout behavior in SHCC [23-27], limited research has focused on the relationship between flowability, fiber orientation, and the mechanical properties of sprayed SHCC. The conflict between pumpability and sprayability requires further resolution. This paper provides a comprehensive review of the design principles, key raw materials, and their influence on performance, as well as the fresh and hardened properties of sprayed SHCC, and comparison with cast SHCC. It aims to provide scientific and practical references for further research on sprayed SHCC and is expected to expand the applications of sprayed SHCC in the construction industry.

2. Mixture design theory of sprayed SHCC

Improper mixture design for sprayed SHCC with high fiber content may lead to high viscosity, poor fiber dispersion, high pumping resistance, insufficient build-up thickness, and further affect the mechanical properties and durability of sprayed SHCC. Therefore, a scientific mixture proportion design for sprayed SHCC should ensure the synergistic optimization of both its rheology during pumping and spraying processes and mechanical properties after hardening.

2.1. Mixture design based on micromechanical criteria

The mixture design of sprayed SHCC is based on the micromechanics of fiber bridging of microcracks and their propagation mode. The design basis of SHCC links the material microstructure to the composite tensile performance [

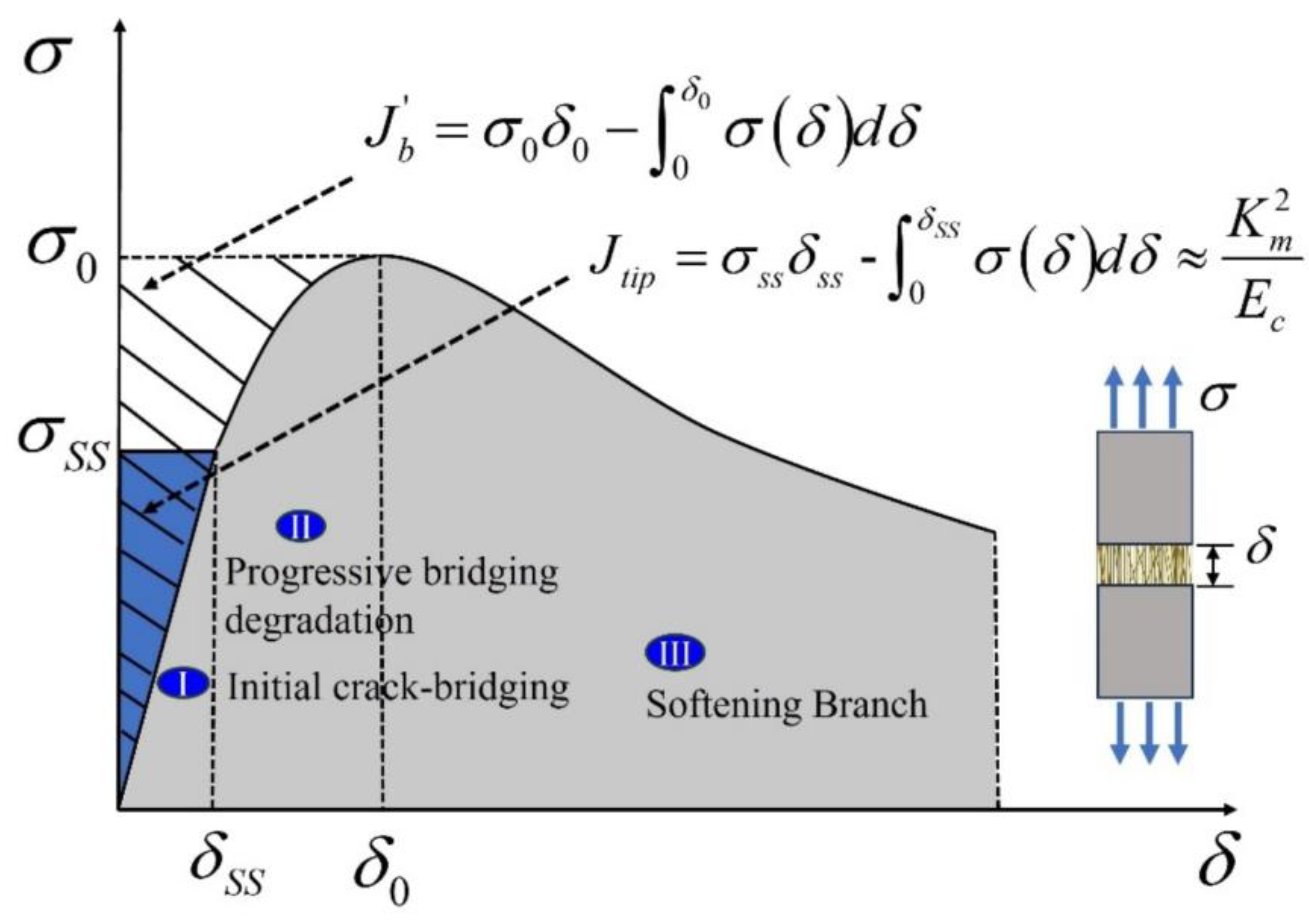

28]. To satisfy the conditions for strain-hardening and multiple cracking characteristics, the size of initial matrix flaws, matrix toughness, and the displacement (σ–δ) behavior of crack-bridging fibers must conform to the energy and strength criteria as expressed in Eqs. (1) to (4), and as illustrated in

Figure 1 [29, 30]. The σ–δ law describes the constitutive relationship between the tensile stress (σ) acting on the matrix crack plane and the crack opening displacement (δ) of a single crack, which emphasizes the synergistic interactions among the fiber, the matrix, and the fiber-matrix interface.

From the σ–δ curve in

Figure 1, the maximum bridging stress

can be inferred. According to the strength criterion, the steady-state matrix cracking stress must be lower than the maximum bridging capacity of fibers, as shown in Eq. (1). This requirement ensures that the tensile stress that initiates a steady-state crack from a pre-existing matrix flaw is below the fiber bridging capacity

[

30]. Otherwise, the fibers would rupture and/or pull out after matrix cracking, failing to serve their bridging function, and the composite would exhibit a strain-softening behavior. According to the energy criterion, Eqs. (2) to (4), the fracture toughness at the crack tip (

) must be lower than the maximum complementary energy of fibers (

), a key condition for achieving steady-state crack extension rather than Griffith fracture [31, 32].

where

represents the tensile cracking strength of the matrix (MPa);

depends on the fracture toughness and defect size distribution of the matrix [

28];

is the peak fiber bridging strength (MPa);

is the crack tip toughness (

);

is the complementary energy (J/m

2);

and

(mm) are the corresponding crack widths for stresses

and

, respectively;

is the steady-state bridging stress (MPa);

(

) and

Ec (GPa) are matrix fracture toughness and Young’s Modulus, respectively.

In SHCC, achieving a steady-state crack enables the development of multiple cracks as the imposed tensile load increases and activates smaller flaws successively. When the applied tensile stress reaches , the composite exhausts the bridging capacity at one of the multiple crack sites, resulting in the localization of crack opening at decreasing bridging traction, i.e., tension softening.

From the above discussion, it can be seen that

and

should be minimized, and

and

should be maximized in the mixture design of SHCC to meet the energy and strength criteria. The pseudo-strain-hardening (PSH) index can be used to assess the strain-hardening potential of SHCC, which is defined in Eqs. (5) and (6) [30, 33]. A high PSH is preferred for steady-state crack propagation in the presence of material variability [

34]. Li [

2] and Kanda et al. [

32] pointed out that while

and

represents theoretical prerequisites for multiple cracking of SHCC, experimental data suggest the need for

and

due to fiber and matrix parametric variability associated with composite processing.

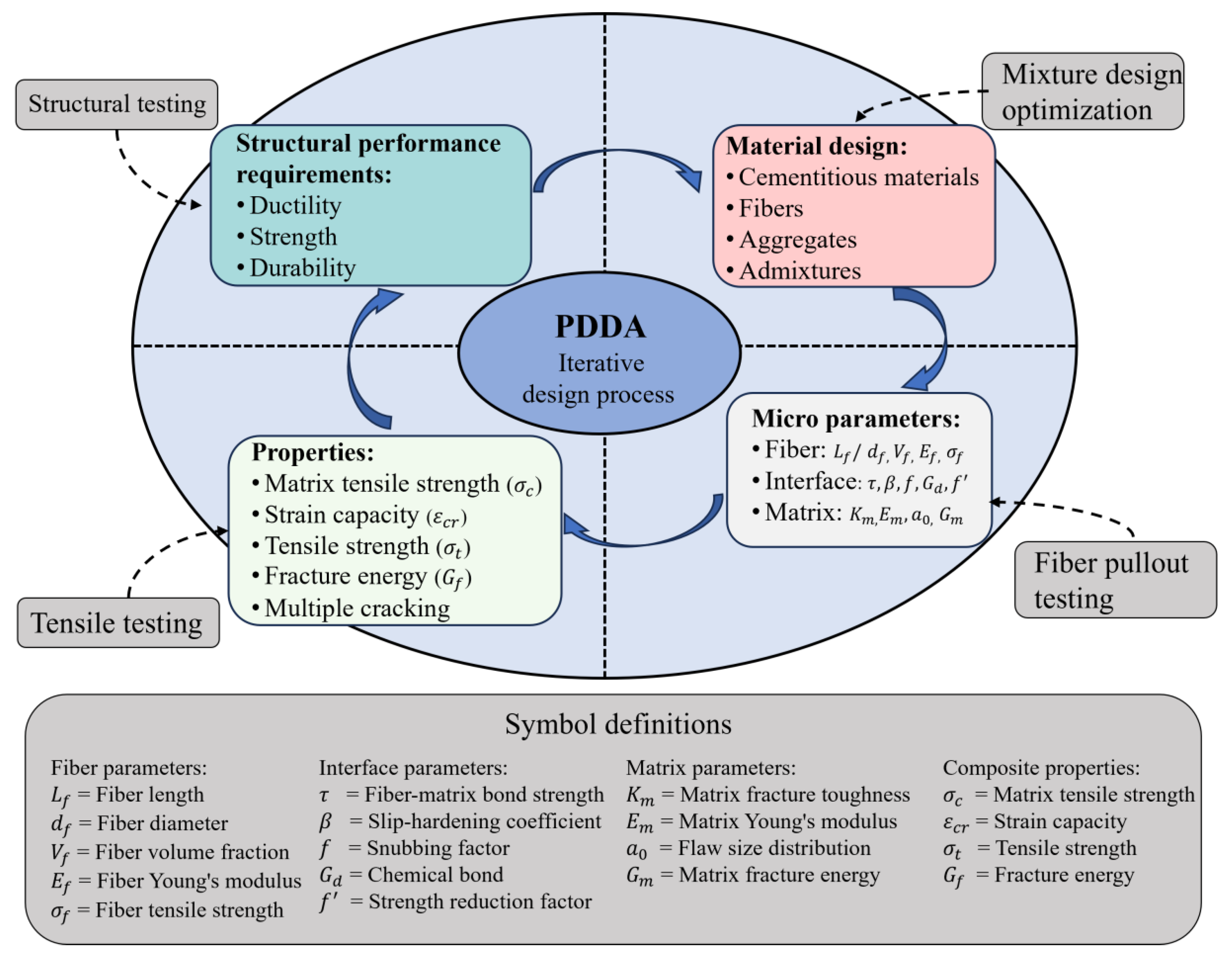

As shown in

Figure 2, the performance-driven design approach (PDDA) proposed by Li et al. [30, 35] connects the material structure and mechanical properties to achieve the high ductility of SHCC. By quantitatively analyzing critical microscopic parameters, such as matrix fracture toughness, fiber strength, and bond strength at the fiber-matrix interface, the corresponding microscopic mechanical models are used to predict macroscopic mechanical behaviors. This enables precise engineering control of SHCC, including ductility and cracking resistance. Specifically, the PDDA process first clarifies the performance requirements for structural applications and then optimizes the fiber-matrix interactions through interface engineering, leading to a scientific and systematic design methodology for SHCC materials.

It should be noted that the s(d) relation is influenced by fiber orientation as affected by the spray process. Similarly, the fiber/matrix interface properties and the matrix flaw size and toughness can be affected by the spray process. Thus, the tensile properties of spray SHCC can be highly dependent on the spray operation details, as will be discussed in

Section 5.3.2.

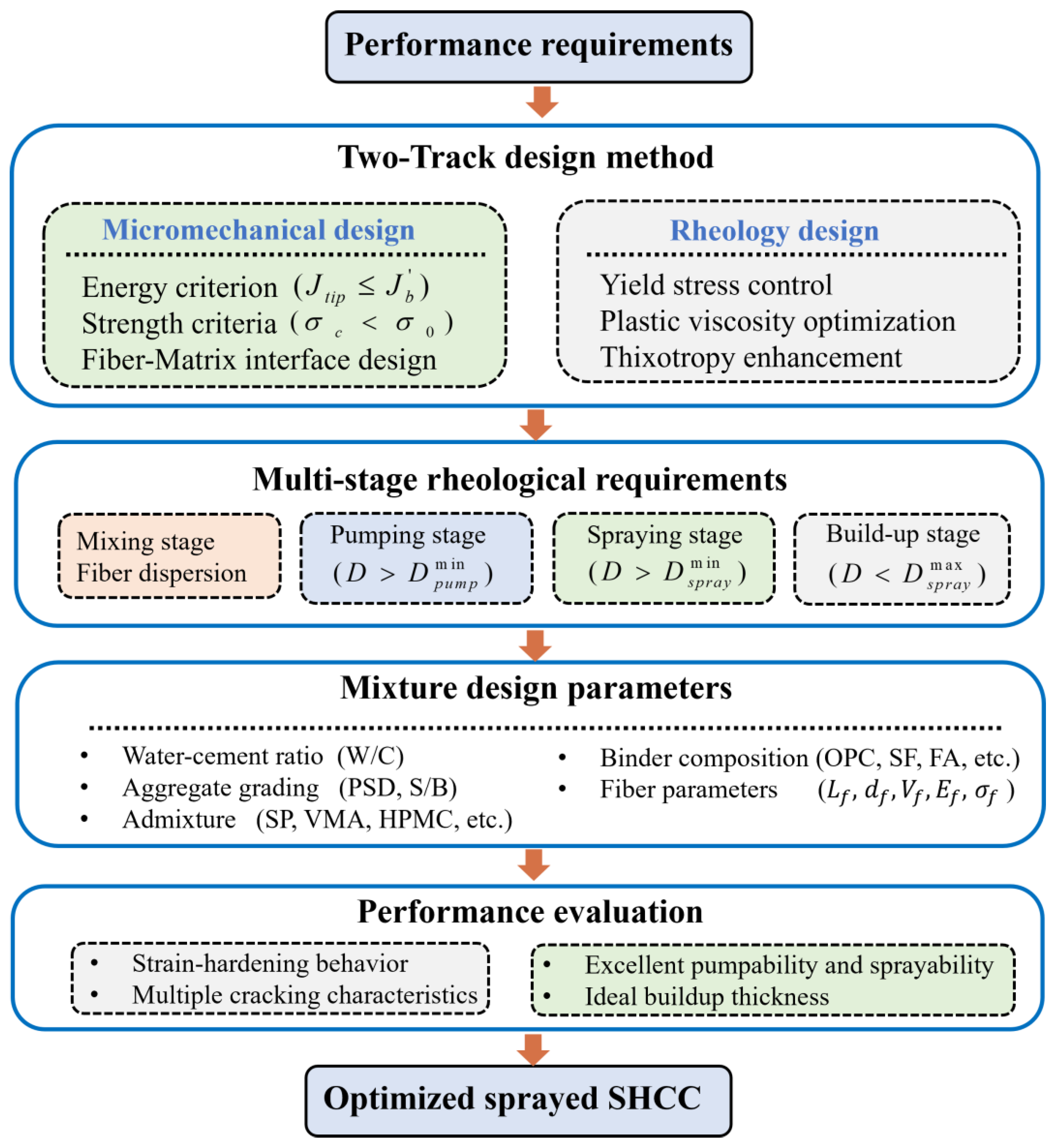

2.2. Mixture design based on rheological properties of sprayed SHCC

2.2.1. Definition and requirements for the rheology of sprayed SHCC

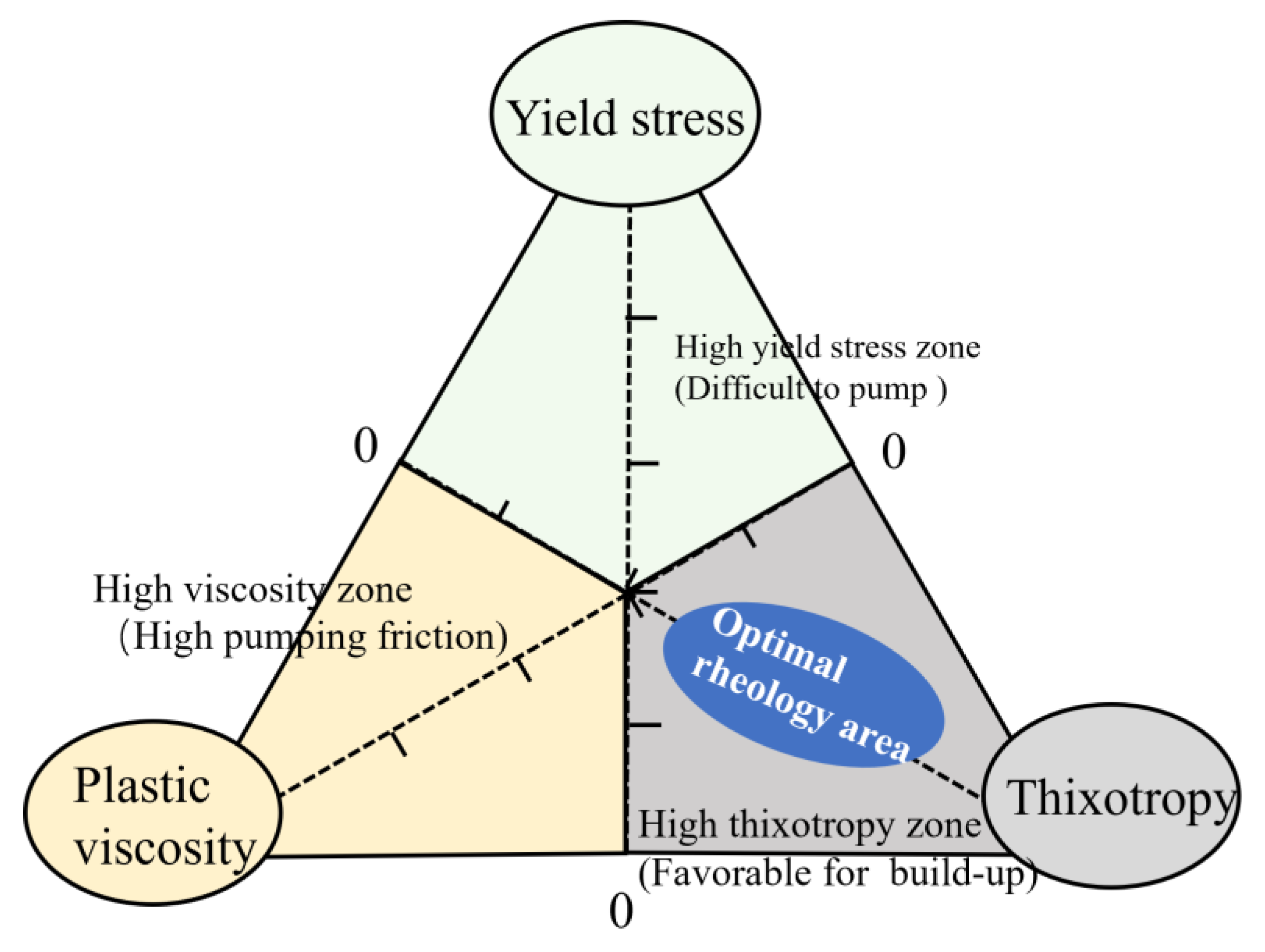

The rheology of SHCC governs its deformation and flow resistance during pumping and spraying processes, primarily characterized by yield stress, plastic viscosity, and thixotropy [

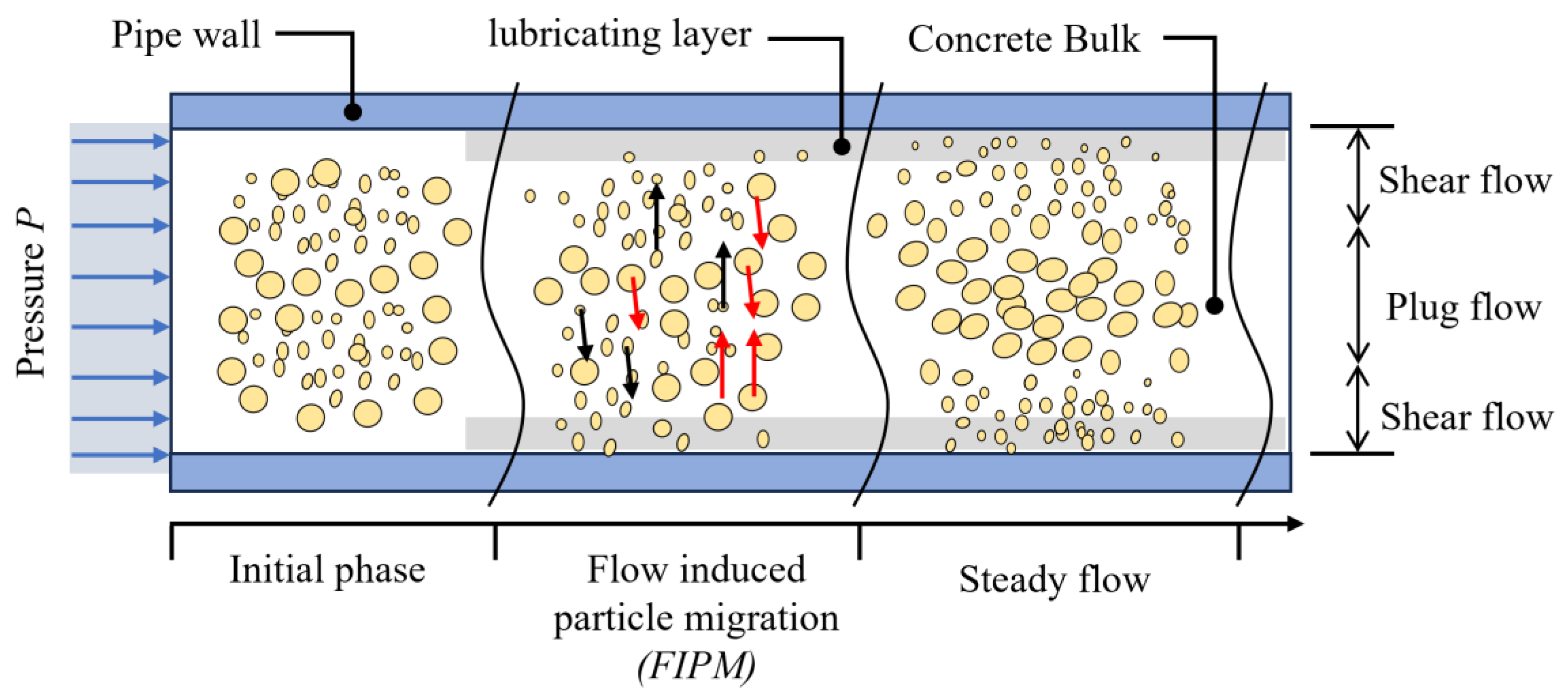

36]. For sprayed SHCC, low dynamic yield stress enables smooth flow through pipes and nozzles during pumping, while developing adequate plastic viscosity and cohesiveness after spraying ensures overlay stability and prevents sagging or segregation [13, 37] (see

Section 5.1 and 5.2 for details). Additionally, ideal sprayed SHCC exhibits distinct thixotropic behavior, showing increased flowability under shear with rapid recovery to a cohesive state at rest, to enable rapid setting and achieve the desired build-up thickness that satisfies structural requirements [

38]. Consequently, the design of sprayed SHCC involves carefully balancing yield stress, plastic viscosity, and thixotropy, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

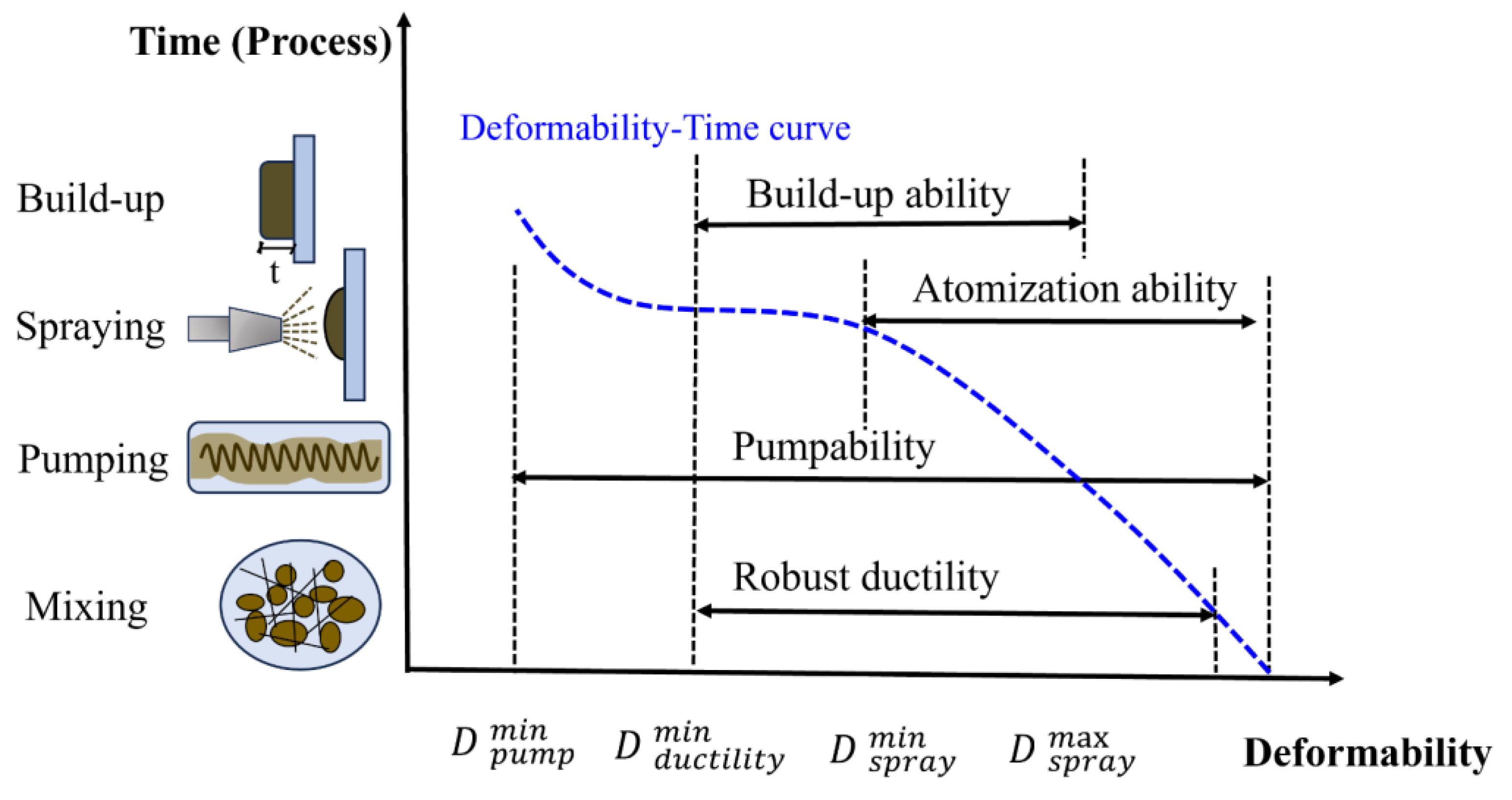

To achieve continuous and stable spraying as well as superior mechanical properties, the rheology of sprayed SHCC should meet the multi-stage requirements. Zhu

et al. [

39] detailed the specific rheological requirements for sprayed SHCC in the mixing, pumping, spraying, and build-up stage: (1) The mixing stage of sprayed SHCC should ensure the uniform distribution of fibers; (2) The pumping stage requires sprayed SHCC to exhibit high initial deformability and low viscosity to minimize frictional resistance within the conveying pipes; (3) The spraying stage requires high concrete adhesion and minimal rebound loss. Zhu

et al. [

39] proposed deformation index and atomization properties as assessment tools for rheological changes during spraying. Freshly sprayed SHCC requires excellent flowability and deformability during pipe transportation until it is sprayed onto the substrate (as shown in

Figure 4). Upon spraying onto the substrate surface, its deformability rapidly decreases while cohesiveness increases, allowing the material to attain sufficient build-up thickness and meet structural performance requirements.

2.2.2. Rheology influence factors

Unlike ordinary shotcrete, sprayed SHCC contains a relatively high-volume fraction (typically 2% or less) of high aspect ratio polymer fibers that bridge cracks, transfer loads, and enhance ductility of the sprayed SHCC. The adjustment of sprayed SHCC rheology aims not only to facilitate pumping and spraying but also to ensure uniform fiber dispersion and to avoid excessive voids [40, 41]. The effect of polymer fibers on the rheological properties of the fresh mix depends on the stiffness, aspect ratio, and volume fraction of the fibers [

42]. Polymer fibers have distinct mechanical properties with an elastic modulus of 10–100 GPa (compared to approximately 200 GPa for steel fibers) and elongations of 3%–15%, enabling substantial deformation under tension without fracture [

43]. According to Forgacs and Mason [

44], lower stiffness or higher aspect ratio promotes fiber bending. Unlike rigid fibers, which tend to align preferentially in the matrix under shear flow, flexible polymer fibers remain randomly oriented, bent, and twisted in SHCC even when subjected to shear fields during mixing, pumping, and spraying [

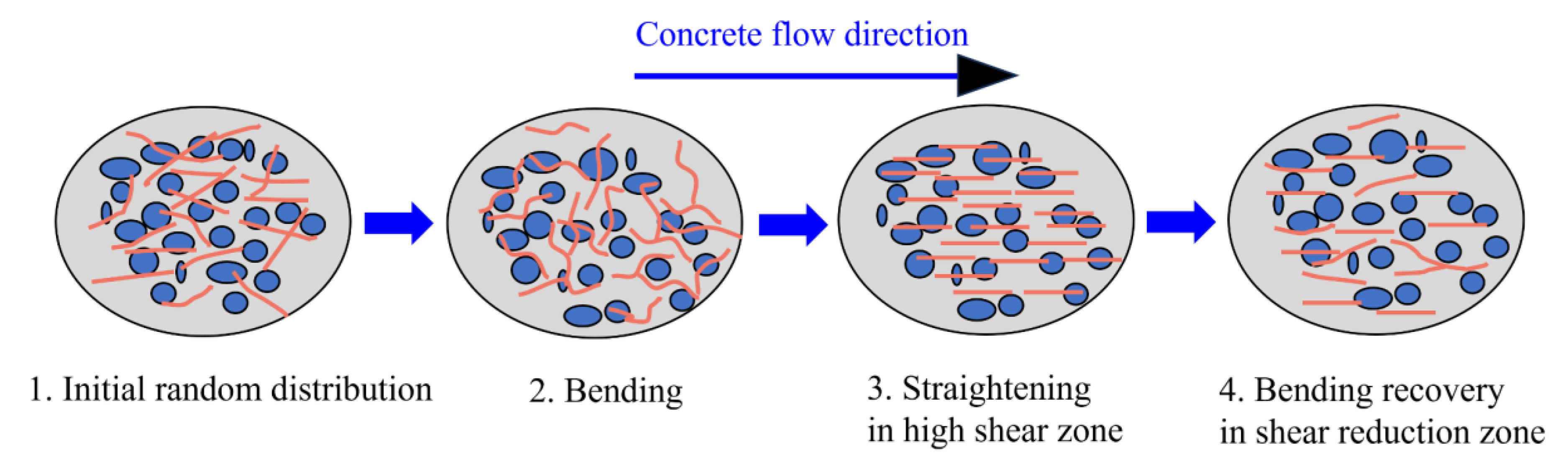

45]. In regions of high shear within SHCC, flexible polymer fibers tend to align with the flow direction. When the SHCC shear force decreases, fibers partially revert to a bent state due to their inherent elasticity and resistance from the surrounding matrix, as shown in

Figure 5. This reversible orientation change enhances SHCC thixotropy by restoring its internal structure after shear cessation. From a particle-packing perspective, flexible fibers occupy inter-particle voids, disrupting the original particle packing structure and forming fiber networks that restrict particle sliding and rearrangement, which directly increases yield stress. The rheological impact of fiber can be quantified by treating SHCC as a colloidal suspension system, where adding fibers increases the shear viscosity of the suspension [46, 47]. According to the Krieger-Dougherty model, when the effective volume fraction of flexible fibers with high aspect ratios approaches the critical value, the viscosity of the paste increases exponentially [

48]. Consequently, polymer fibers with high aspect ratios and high-volume fractions lead to increased yield stress, elevated plastic viscosity, and enhanced thixotropy in sprayed SHCC.

The rheological properties of sprayed SHCC can be regulated by controlling the water-to-cement ratio, optimizing the cementitious material composition and aggregate gradation, incorporating admixtures, and optimizing the mixing process [49-52]. Ku

et al. [

51] found that a higher water-to-cement ratio might improve pumpability but adversely affect the sprayability. An alkali-free accelerator and organic polymer tackifier can be used to increase the yield stress and plastic viscosity of sprayed SHCC, thereby enhancing sprayability, reducing rebound rates, and minimizing material loss during spraying [

53]. A homogeneous aggregate gradation following the Fuller curve or the modified Andreasen model can improve flowability without increasing the amount of water, simultaneously maintaining sufficient viscosity to prevent segregation [

54]. Moreover, incorporating ultra-fine spherical particles, such as nano-silica, can effectively increase the yield stress and build-up thickness of sprayed SHCC [

55].

2.2.3. Rheology-based mixture design

Evaluating and controlling rheological properties of cementitious materials, such as cement, mortar, fiber-reinforced concrete, and shotcrete, is challenging. In SHCC, the challenge is amplified by the large number of fibers. For SHCC reinforced with polypropylene (PP) fiber (PP-SHCC) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fiber (PVA-SHCC) with aligned fibers, for 2% volume fraction of fibers with diameters of 40 μm and 17 μm, respectively, approximately 1600 and 8800 fibers will bridge across each square centimeter of crack surface [

2]. The large number of fibers results in difficulties in pumping and spraying SHCC. Therefore, to satisfy both structural and performance requirements for sprayed SHCC, compatibility among raw materials in the mixture must be ensured. By integrating micromechanical principles with rheological control, Yang and Kim

et al. [56, 57] applied the Integrated Structural and Materials Design (ISMD) concept, combining structural requirements with material properties. They selected appropriate matrices and fibers, adjusted the fiber-matrix interfacial properties, and optimized the paste rheology to ensure that the sprayed SHCC achieves desirable tensile strain-hardening behavior, multiple cracking characteristics, along with excellent pumpability, sprayability, and a low rebound rate.

Therefore, a systematic application of the rheological properties is required for mixture design to ensure that sprayed SHCC exhibits excellent construction performance (such as pumpability, sprayability, and build-up ability) and achieves the target structural properties. This design method is based on optimizing and controlling rheological parameters (e.g., yield stress, plastic viscosity, and thixotropy). It explicitly integrates the specific requirements of each spraying stage (mixing, pumping, spraying, and build-up), while simultaneously considering micromechanical criteria to ensure hardened sprayed SHCC has strain-hardening and multiple cracking behaviors, as illustrated in

Figure 6.

3. Raw materials of sprayed SHCC

3.1. Matrix

3.1.1. Cementitious materials

Binder selection and dosage must ensure compatibility with chemical admixtures, sufficient pumpability, rapid early strength, and long-term durability for sprayed SHCC. In general, CEM I and CEM II Portland cement are often used in sprayed SHCC. CEM I 52.5R cement is the preferred choice for applications demanding high early strength, while CEM II/A-L 42.5R is recommended for typical strength requirements in sprayed SHCC [

58]. Compared with ordinary Portland cement (OPC), rapid-hardening calcium sulfoaluminate (CSA) cement primarily consists of calcium sulfoaluminate (C₄A₃S̄) as the main mineral phase, supplemented by calcium sulfate and calcium sources. At early hydration stages, rapid reaction between calcium sulfoaluminate and calcium sulfate forms abundant needle-like ettringite crystals. It creates a dense network structure, providing significant strength within 1–3 hours, making CSA cement widely used in tunnel construction or slope support processes where shotcrete reinforcement is required [

59]. Silica fume, an ultra-fine pozzolanic admixture (particle size is about 0.1–0.3 μm), increases matrix density through filling effects and pozzolanic reactions. Its spherical shape improves the rheological properties and fiber-matrix bonding of sprayed SHCC. However, a large amount of silica fume significantly increases paste viscosity and thixotropy, raising pumping and spraying resistance, and elevating the risks of autogenous shrinkage and cracking in sprayed SHCC [

60]. To mitigate these effects, industry standards typically recommend silica fume additions not exceeding 12%–15% of cement weight, and Spanish standards specifically recommend keeping silica fume dosage below 10% by cement weight [

61]. Choi

et al. [

62] demonstrated that incorporating 4.5% silica fume significantly enhances the compressive and flexural strengths of sprayed SHCC after spraying. Similarly, fly ash, with its spherical particle morphology, effectively improves the flowability and pumpability of sprayed SHCC. However, high fly ash content may reduce fiber-matrix interfacial bond strength, weakening the overall performance of sprayed SHCC. Kim

et al. [

57] found that fly ash content within 30% in sprayed SHCC balances workability and strength. Cabrera and Wooley [

63] observed a noticeable reduction in rebound rate when 30% fly ash was incorporated. Therefore, carefully optimizing the proportions of cement, silica fume, and fly ash allows effective control of the rheological properties, setting time, strength development, and strain-hardening characteristics of sprayed SHCC.

3.1.2. Aggregates

According to micromechanical design principles and steady-state cracking requirements, the proportion of aggregates in SHCC is significantly lower than in plain concrete. Typically, fine aggregates (i.e., sands) are preferred over coarse aggregates because their smaller size creates more uniform stress distribution and reduces the fracture toughness of matrix, promoting the multiple cracking behavior essential for the strain-hardening performance of SHCC [

64]. The effect of aggregate on the SHCC ductility is reflected in two aspects. Firstly, smaller aggregates reduce the matrix toughness [

65] (K

m), lowers the first-cracking strength of SHCC and facilitates the early transfer of loads to the fibers. Second, aggregate affects the distribution of fibers and interfacial properties, consequently influencing the supplementary energy and the fiber bridging strength. Previous studies indicate that specific aggregates, such as granite fines, can improve tensile strength by increasing particle friction [

66], while river sand, by introducing effective defects, promotes crack formation [

67]. Additional defects in SHCC from lower-strength fine aggregates reduce matrix fracture toughness and enhance strain-hardening potential, but their overuse hinders saturated multiple cracking [2, 67, 68]. As the proportion of fine aggregate increases, the tensile strength of the SHCC matrix initially increases and then decreases, while the compressive strength and the average crack width of the SHCC matrix decrease gradually. Thus, SHCC can be produced with acceptable ductility by suitably restricting the quantity of fine aggregate in the SHCC matrix and ensuring adequate bonding at the fiber-matrix interface.

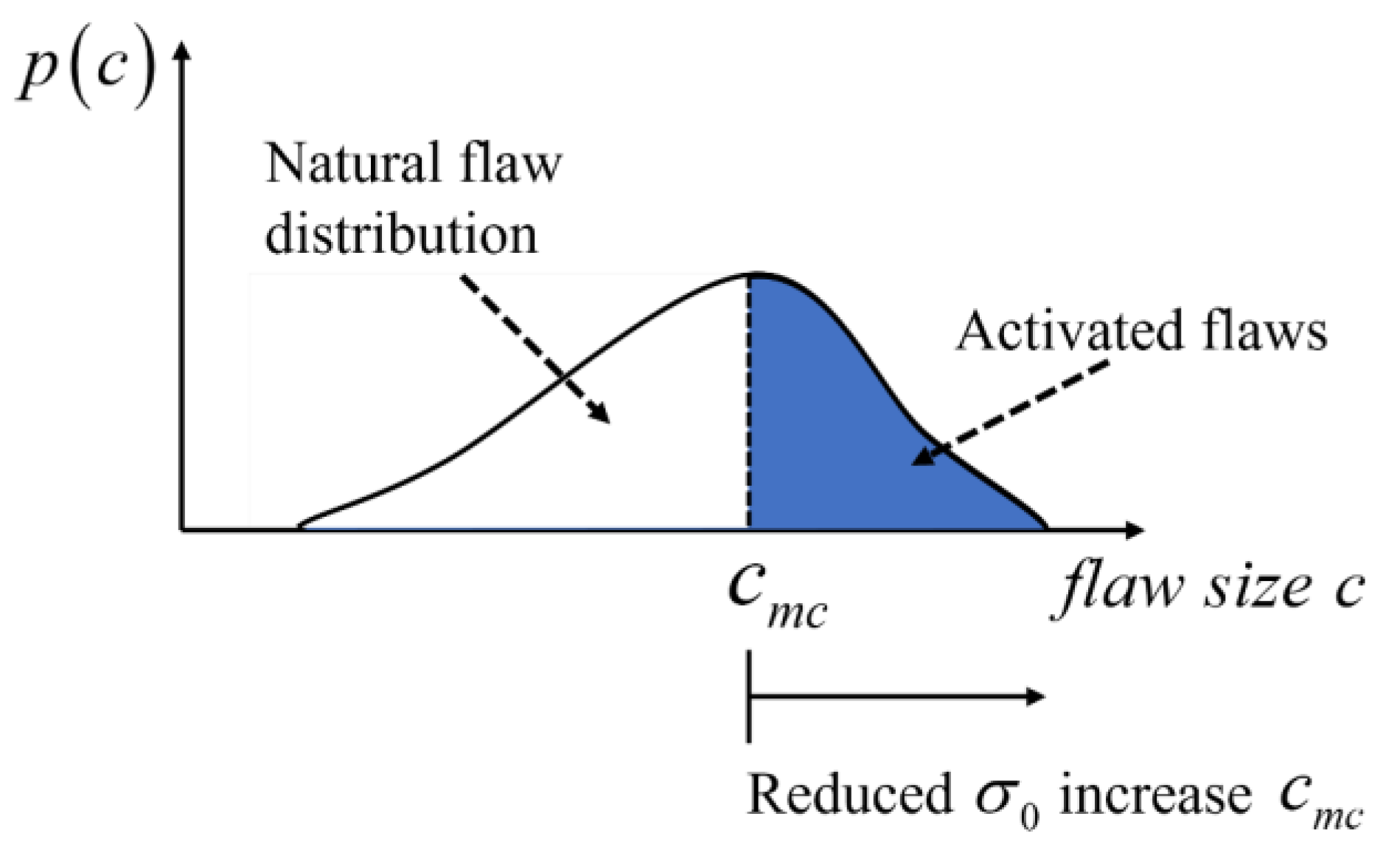

The tensile strain capacity of SHCC is influenced by the distribution of pre-existing flaw sizes, matrix fracture toughness, and the fiber bridging strength, as shown in

Figure 7. Uneven fiber dispersion reduces fiber bridging strength, enlarges critical flaw sizes, and activates fewer pre-existing flaws, which decreases the tensile strain capacity of SHCC [

69]. In general, introducing coarse aggregates with larger particle sizes increases the number and size of internal defects, and increases matrix fracture toughness due to more tortuous crack propagation paths along interfacial transition zones (ITZ), thereby suppressing multiple cracking [

70]. The flaws when using the coarse aggregate also cause variability in the cracking strength of the matrix between neighboring parallel cracks in the SHCC matrix. As existing cracks reach a critical opening under tensile stress, new cracks initiate at other flaw sites throughout the matrix, contributing to the desired multiple cracking behavior [

70]. Xu

et al. [

71] demonstrated that increasing the particle size of the aggregate increases the total flaw size in the SHCC matrix. However, the probability density of smaller flaws (0.1–0.2 mm) decreases. The initial flaw size distribution in the SHCC can be quantified using a Weibull-type function, as expressed in Eq. (7) [

68], where F(r) is the cumulative probability of an initial flaw with an equivalent radius less than

r;

k and λ are the shape and scale parameters, respectively; and

is the minimum flow radius (mm).

According to the particle close-packing theory, continuously graded aggregates contribute to the increased density and dimensional stability of SHCC, enhancing the bonding between fibers and the matrix. The tensile properties of SHCC decrease with increasing aggregate particle size because the larger the aggregate particle size, the smaller the number of particles for the same aggregate amount. Hence, the lack of sufficiently distributed aggregate in the matrix results in a significant deviation in matrix fracture toughness and a gradual decrease in fiber bridging strength [70, 72]. To determine the optimal range of particle size of aggregate in SHCC, Lei

et al. [

73] assumed that 2 vol.% of the fibers in SHCC were uniformly distributed, forming an equidistant three-dimensional cubic lattice structure. The fiber space theory proposed by Romualdi assumed that continuous fibers are evenly distributed along the pullout direction [

74]. Based on the above theory, Hu

et al. [

75] modified the equidistant three-dimensional cubic space with a uniform distribution of fibers by reducing the spacing between fibers and aggregate to 100 μm. This modification aimed to increase the spatial interlocking effect of fibers and aggregate, and the ideal average value of aggregate particle size was calculated using Eqs. (8) to (10).

where

X is the dimension of the equidistant three-dimensional cubic lattice structure proposed by Lei

et al. [

73];

R is the fiber diameter (mm), and

L is the total length of 2 vol.% fibers per unit cubic meter.

During the construction process of sprayed SHCC, aggregate size directly affects rebound behavior and pumpability. Studies have shown that maximum aggregate size positively correlates with rebound rate, with aggregates larger than 5 mm more likely to rebound during high-speed spraying [

76]. Austin

et al. [

77] observed that each 1 mm increase in particle size can raise the rebound rate by roughly 2%–5%, particularly on vertical surfaces and overhead applications. To ensure pumping stability, Morgan [

78] recommends that the maximum aggregate size should not exceed one-third of the delivery pipe diameter, typically kept within the 2–4 mm range. Furthermore, continuously graded aggregates demonstrate lower rebound rates and enhanced cohesiveness compared to uniformly sized aggregates. Moreover, according to CNR DT 204/2006 guidelines [

79], to prevent aggregates from interfering with fiber distribution and orientation, the average aggregate size should not exceed one-quarter to one-third of the fiber length. Therefore, for sprayed SHCC, it is advisable to select fine aggregates with a maximum particle size of less than 4 mm, clean surfaces, regular shape, and continuous gradation to optimize spraying performance and strain-hardening behavior [78, 79].

3.2. Fiber

Commonly used fibers, such as PVA, PP, and polyethylene (PE), play a dual role in the design of sprayed SHCC. From the micromechanical perspective, these fibers enable strain-hardening and multiple cracking mechanisms by providing bridging forces across crack surfaces, with performance dependent on complex fiber-matrix interactions, including chemical bonding, frictional slip, and energy dissipation. Rheologically

, fibers act as flexible units participating in paste flow, undergoing orientation changes and bending deformation under different shear conditions, forming network structures that affect particle packing, significantly affecting material yield stress, plastic viscosity, and thixotropy. To achieve tensile strain capacities of 3%–7%, SHCCs typically incorporate equal to or less than 2 vol.% PVA, PE, or high tenacity polypropylene (HTPP) fibers [24, 39]. Based on fiber bridging theory, fibers prevent structures from strain softening and brittle fracture, but a fiber-reinforced composite with PVA fiber content less than 2 vol.% may not exhibit saturated multiple cracking characteristics [

80]. Additionally, fiber length (L) and diameter (d) determine fiber bridging strength

and complementary energy

. Yu et al. [

81] demonstrated that a higher aspect ratio (L/d) increases fracture energy consumption during pull-out and reduces crack spacing. This is because a higher aspect ratio increases effective bonding area at crack interfaces, and fiber bridging efficiency directly correlates to embedment length, which is longer fibers providing a larger stress-transferring area within the matrix [82, 83]. Finer fibers imply a larger number of fibers due to their smaller cross-sectional area for a given volume fraction, creating more crack-bridging points that distribute applied loads more uniformly across the matrix and reduce the stress concentration, thereby minimizing local matrix crack formation [

2].

Based on the research of Zhang

et al. [

34], micromechanical framework provides effective criteria for fiber selection in SHCC, and optimal fibers should possess the following characteristics: (1) Moderate aspect ratio to maintain composite flowability and fiber dispersion; (2) Appropriate elastic modulus to facilitate controlled microcracking under load; (3) Sufficient elongation at break to prevent breakage during mixing; (4) Balanced interfacial bond properties-neither too weak nor too strong. These criteria specify that fiber content should not be greater than 2 vol.%, with fiber lengths ranging from 6–12 mm, an elastic modulus greater than 10 GPa, tensile strain capacity above 3%, and excellent corrosion resistance and chemical stability within cementitious environments.

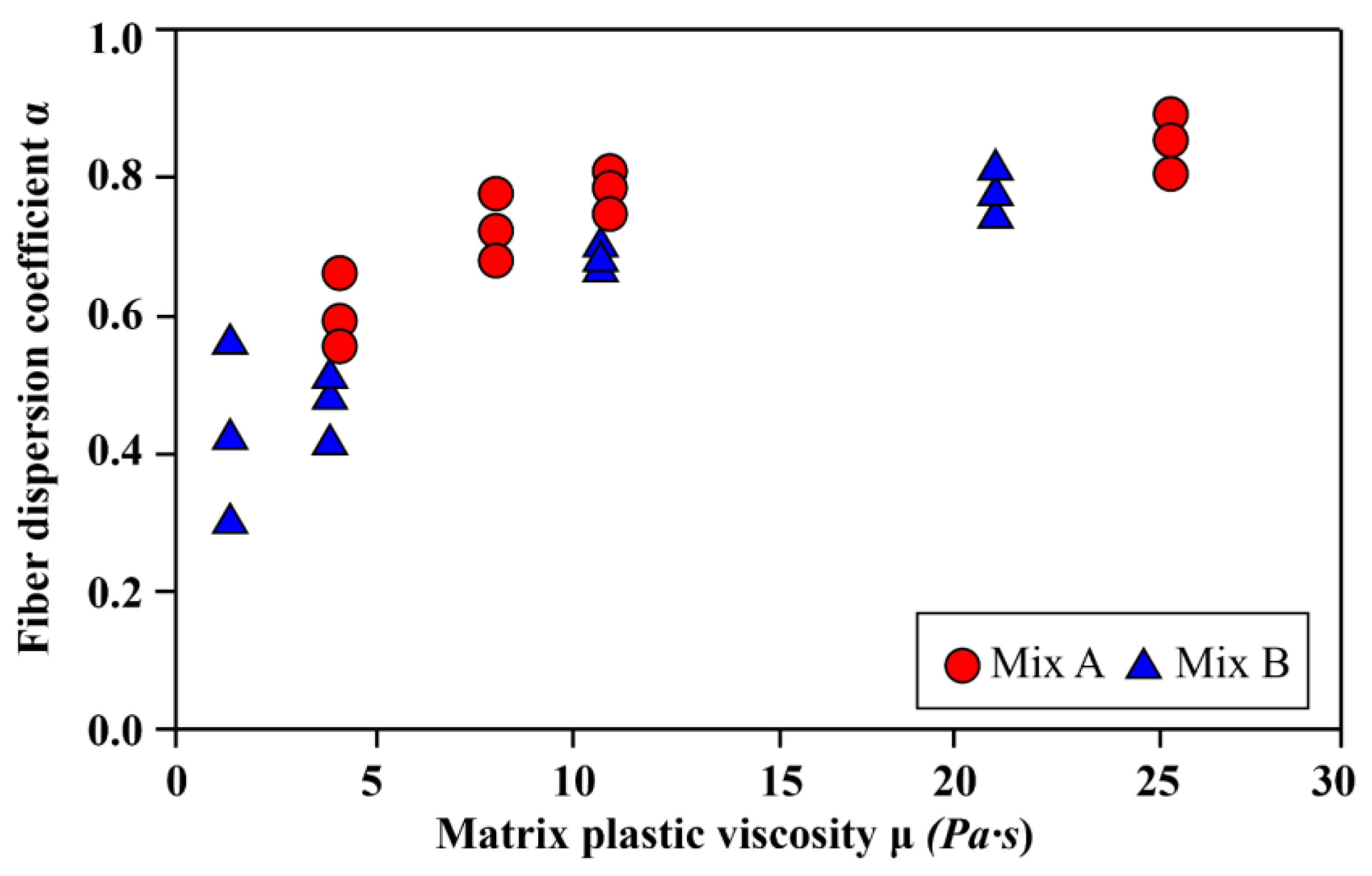

As previously mentioned, fiber dimensions and type influence the rheological properties of SHCC, thereby affecting fiber distribution. Uneven fiber distribution increases critical flaw size and introduces air voids, resulting in reduced tensile strain capacity, as only a small percentage of flaws are activated to form saturated cracks [69, 84]. Zhang and Li

et al. [69, 84] suggested that increasing matrix plastic viscosity from 1–26 Pa·s raised the fiber dispersion coefficient from 0.43–0.85, as shown in

Figure 8. However, excessive viscosity increases air entrapment, weakening interfacial bonding [

69]. Swamy

et al. [

85] indicated that an optimal critical fiber volume and plastic viscosity exist for fiber-reinforced concrete, where an increase in aspect ratio permits reduced fiber contents. In conclusion, effective sprayed SHCC design requires integrated fiber parameter selection encompassing type, geometric parameters, and dosage to optimize dispersion uniformity, crack bridging efficiency, and processing workability.

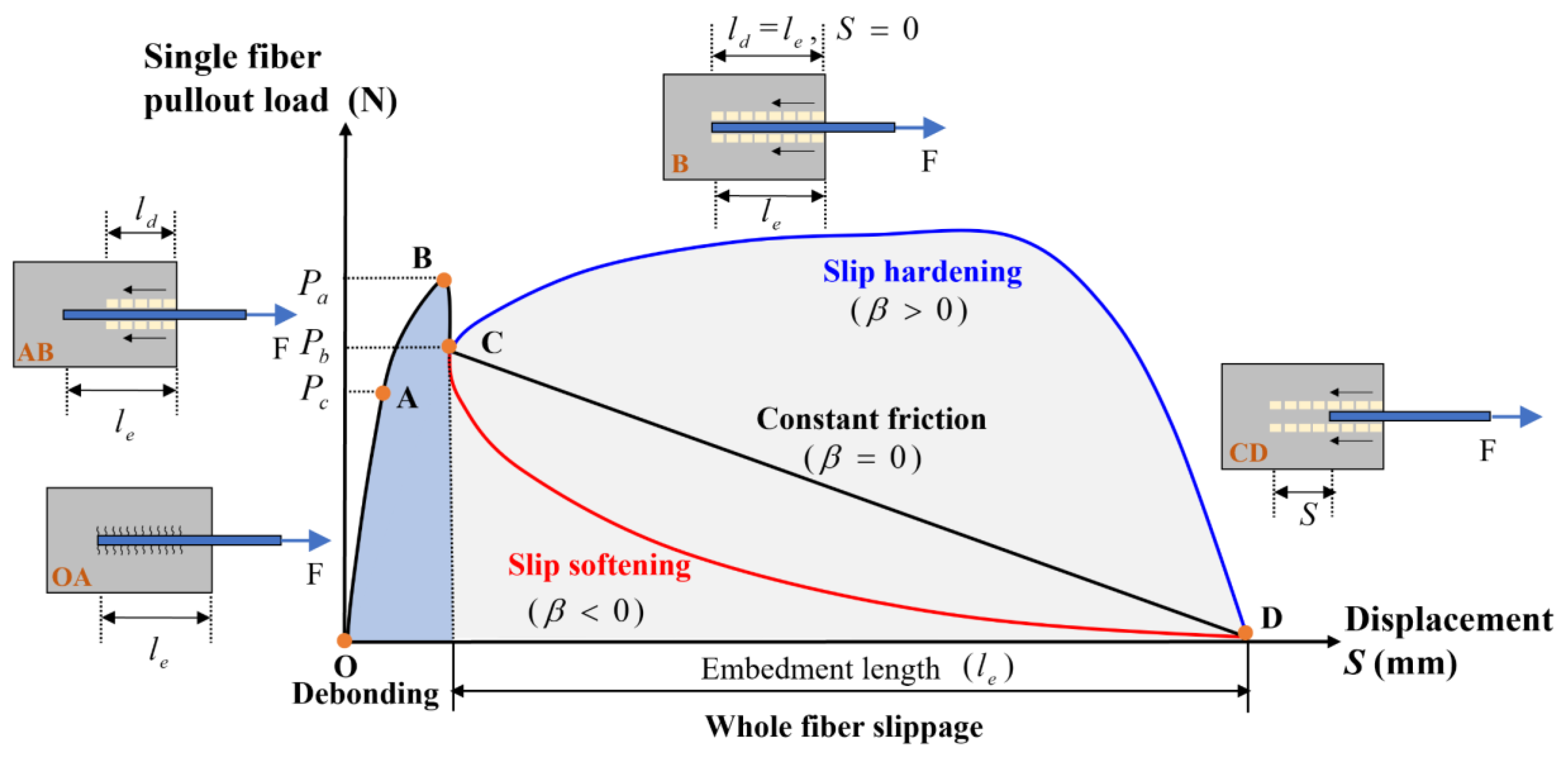

3.3. Fiber-matrix interface

The fiber-matrix interface governs stress transfer and crack control in SHCC, and its performance can be effectively characterized through the fiber pullout process. Fiber pullout mechanics involve the following three sequential stages governed by interfacial bonding and friction mechanisms [86, 87]. (1) As load increases linearly to the critical shear strength

Pc (OA segment), the fiber-matrix interface begins debonding from the fiber embedment end, forming a debonded length (

Ld). When

Ld equals the fiber embedment length (

Le), the load-displacement curve reaches the initial peak

Pa (AB segment). Assuming uniform stress distribution at this instant, the interfacial bond strength can be calculated from Eq. (11). (2) The fibers are fully debonded without slippage, and fiber displacement change is only contributed by the elastic stretch and free length of the debonded fiber segments, with the load gradually decreasing to

Pb (BC segment). The corresponding chemical debonding energy (

Gd) between fiber and matrix is calculated from Eq. (12). (3) Following complete debonding, fibers enter the slip phase with the following three possible modes based on the interfacial friction coefficient (

β). (a) slip-hardening (

β > 0) results from interfacial wear debris accumulation increasing contact area and resistance, potentially inducing fiber rupture, especially in PVA fiber systems [

88]. (b) constant frictional sliding (

β = 0) (CD segment) occurs when fiber and interface wear are minimal and interfacial friction remains stable during slippage; the fiber pullout load exhibits a negative linear relationship with displacement. (c) slip-softening (

β < 0) develops through progressive contact area reduction and debris elimination during continued sliding. The whole process is illustrated in

Figure 9.

where

is the frictional bond strength (MPa); P

a is the maximum tensile force (N); d

f and L

d are the fiber diameter and fiber embedment length (mm), respectively; G

d is the chemical bond energy (J/m

2); and E

f is the Young’s modulus of the fiber.

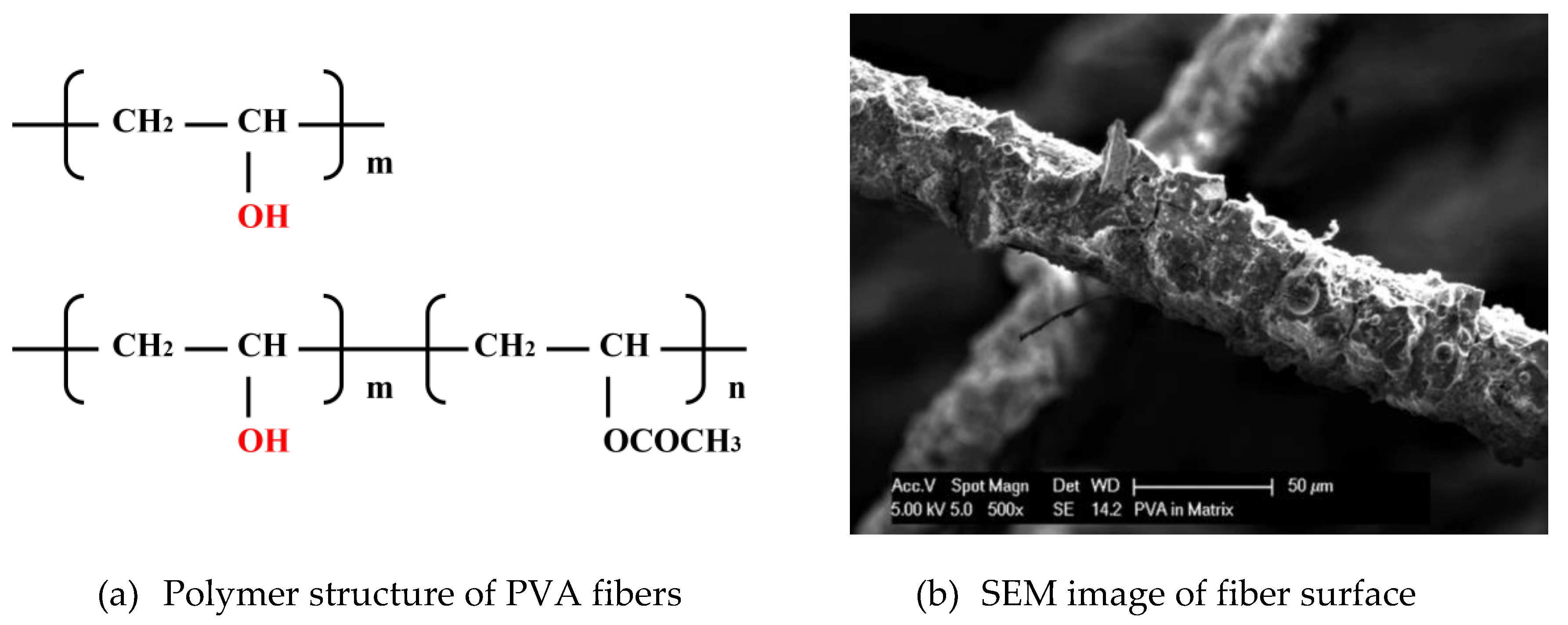

In sprayed SHCC, fiber surface characteristics are crucial to interfacial performance. PVA fibers, rich in hydroxyl groups, can chemically bond with Ca²⁺ ions released during cement hydration and form strong hydrogen bonds with C-S-H gel and Ca(OH)₂ crystals. This promotes dense deposition of hydration products and pronounced hydrophilicity [86, 89], significantly increasing chemical bond strength and frictional resistance. As a result, PVA fibers are more likely to rupture under load rather than gradually pull out. The typical polymer structure of commercial PVA fibers and their SEM appearance in the matrix are shown in

Figure 10. In contrast, PE fibers lack hydroxyl groups, exhibit hydrophobicity, and primarily form mechanical interlocking and frictional contact with cement hydration products, with weak interfacial bond strength that is conducive to the fiber pull-out process. Accordingly, sprayed SHCCs prefer high-strength, high-modulus PE fibers over untreated PVA fibers [

80]. Nevertheless, the hydroxyl functional groups abundant on PVA fiber surfaces enhance wetting within the matrix and enhance the dispersion of the fibers, which represents a significant advantage over PE fibers [

90].

In sprayed SHCC systems, highly hydrophilic PVA fibers may form stronger interfacial bonds with the matrix during the spraying process compared to cast SHCC. Meanwhile, PE fibers with hydrophobic surfaces require surface functional group improvements to achieve uniform dispersion. Based on the existing studies, the methods for modifying PVA and PE fibers include a variety of techniques ranging from traditional oil coating to advanced plasma treatment and nanomaterial composite modification, as shown in

Table 1.

3.4. Accelerator

The use of an accelerator in sprayed SHCC can significantly shorten the initial and final setting time and increase the compressive strength in 1–3 hours by accelerating the rapid formation of hydration products such as ettringite, thereby meeting structural reinforcement requirements. Based on alkali content, accelerators are classified as alkali or alkali-free types. Alkali accelerators typically contain aluminates, silicates, carbonates, and hydroxides [

102]. Considering that alkali accelerators may trigger the alkali-aggregate reaction, which can weaken the long-term strength and durability of sprayed SHCC, alkali accelerators are generally added at a level of less than 10% of the cementitious material content [

103]. Alkali-free accelerators maintain minimal alkali metal content (sodium and potassium), generally less than 1%, with aluminum salts and alkalis being the main active components. Standard alkali-free accelerators are typically combinations of aluminum hydroxide-based accelerators (Al(OH)₃) with aluminum sulfate (Al₂(SO₄)₃) or mixtures of calcium sulfoaluminate (C₄A₃S) and aluminates of sulfate (e.g., Al₂(SO₄)₃) [

104].

Accelerator mechanisms on cement hydration encompass physical and chemical effects. Physical acceleration is based on the seed effect through calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel addition during the cement hydration process [

105]. This method is widely used in commercial accelerators. The underlying principle is that C-S-H gel facilitates ion diffusion due to its porous nature and high specific surface area. This formation of C-S-H gel interconnects the cement particles in suspension, forming a 3D network, which reduces the cement setting time [

106]. Chemical acceleration of cement hydration is mainly through the following three aspects to promote cement hydration: (1) Providing specific ions such as aluminum (Al³⁺) ion, calcium (Ca²⁺) ion, etc. that participate in hydration reactions without significantly altering solution alkalinity; (2) Increasing the pH value of the paste to disrupt cement mineral passivation layers and accelerate ion dissolution; (3) Forming metal complexes that modify hydration kinetics, altering hydration product crystalline morphology and growth rates.

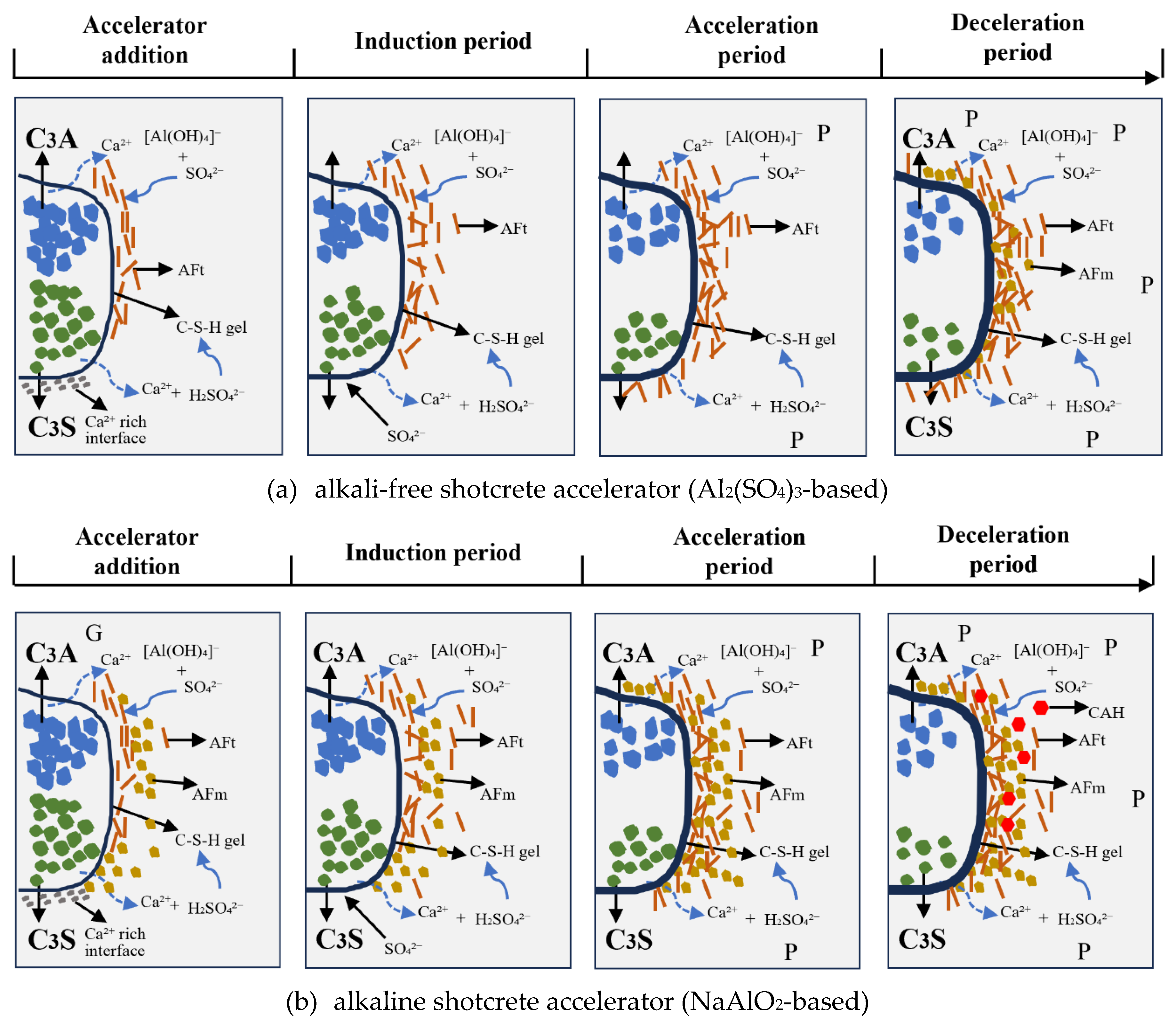

Alkali-free accelerator mechanisms depend fundamentally on ionic chemistry and nucleation pathways. In aluminate-containing systems, aluminum sulfate (Al₂(SO₄)₃) reacts with Ca²⁺ ions released during the induction period of cement hydration to form Al(OH)₃ and ettringite [107, 108], increasing solid-liquid ratios and accelerating matrix hardening, as illustrated in

Figure 11(a) [

109]. Additionally, ettringite adsorbs onto the surface of clinker particles, enhancing their cohesion and further speeding up the initial and final setting times [

108]. Soluble inorganic salts such as calcium chloride (CaCl₂) can also catalyze C-S-H gel generation [110, 111], but the resulting chloride ions promote steel corrosion and reduce the long-term durability of reinforced concrete. Other alkaline accelerators, including carbonates and nitrates, accelerate cement hydration by increasing Ca²⁺ concentration, though with weaker effects due to sulfate depletion and limited ettringite formation [

112]. Other alkaline accelerators, such as sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and sodium silicate, provide Na⁺ and hydroxide ions (OH⁻), significantly increasing the alkalinity of the cement paste pore solution and consequently accelerating the early dissolution of C₃S [

113]. In alkaline solutions, AlO₂⁻ ions convert to [Al(OH)₄]⁻, which subsequently reacts with Ca²⁺ and sulfate ions (SO₄²⁻) to produce AFt, AFm, and C-A-H phases, as illustrated in Eqs. (13) to (17) and

Figure 11(b) [

102].

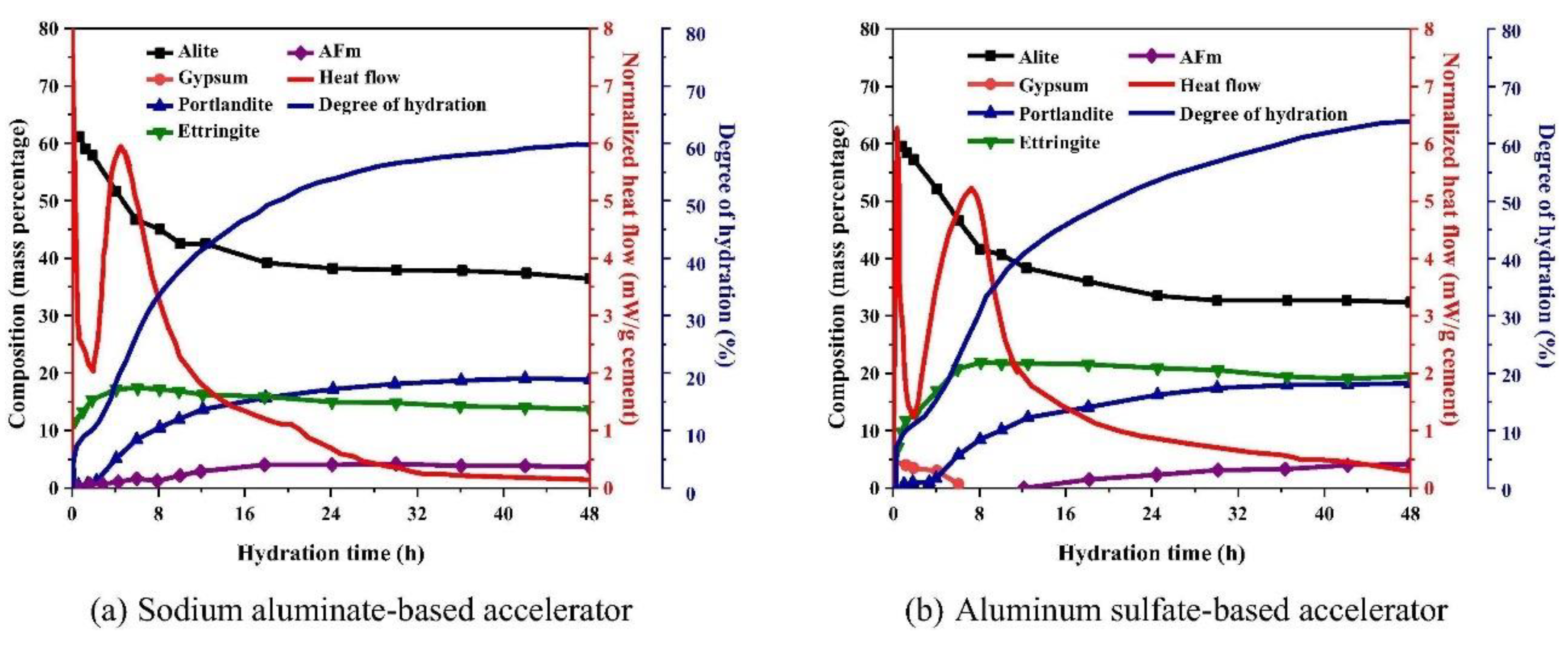

The early-phase hydration products and heat evolution of cement with different accelerators are shown in

Figure 12 [

114]. In the sodium-aluminate system, the sharp increase in pH rapidly breaks down the passive film on cement mineral surfaces while supplying [Al(OH)₄]⁻ complexes, significantly shortening the hydration induction period to less than 1 hour and advancing the occurrence of the heat peak. The aluminum-sulfate accelerator promotes rapid nucleation of ettringite through the synergistic effect of externally provided SO₄²⁻ and Al³⁺ ions, resulting in a slightly delayed but higher peak of heat evolution.

In addition to the common liquid and powdered accelerators, cement-based accelerators, such as quick-setting cement, can be used to reduce the setting time of sprayed SHCC. Examples include calcium sulfoaluminate (CSA) cement and calcium aluminate cement (CAC). According to previous experiments, considering the cost and the long-term strength of sprayed SHCC, the typical dosage of quick-setting cement is usually kept at less than 10% of the cement weight [115-117]. Accelerators promote rapid C-S-H gel formation, providing nucleation sites for cement hydration while enhancing particle flocculation through bridging effects, which increases freshly-sprayed SHCC yield stress and buildup thickness [

118]. However, since the accelerators alter the degree of cement hydration as well as the morphology and distribution of hydration products, Martinez-Ramirez et al. [

119] found that the porosity of cement pastes containing alkaline accelerators was higher than that of cement pastes without accelerators after 28 days of curing. Increased fine pore volumes and higher porosity generally lead to more pronounced drying shrinkage in cement-based materials. Therefore, careful control of accelerator dosage is essential to mitigate potential adverse effects.

4. The spraying process of sprayed SHCC

Cast SHCC and sprayed SHCC differ significantly in their production processes. In sprayed SHCC, the material is conveyed through pneumatic devices and pumping systems to hoses and spray guns, where it is applied at high speed using an airflow of approximately 0.1–0.3 m

3/min and air pressure of 200–600 kPa, with a typical spraying distance of 0.2–0.5 m from the substrate [

9].

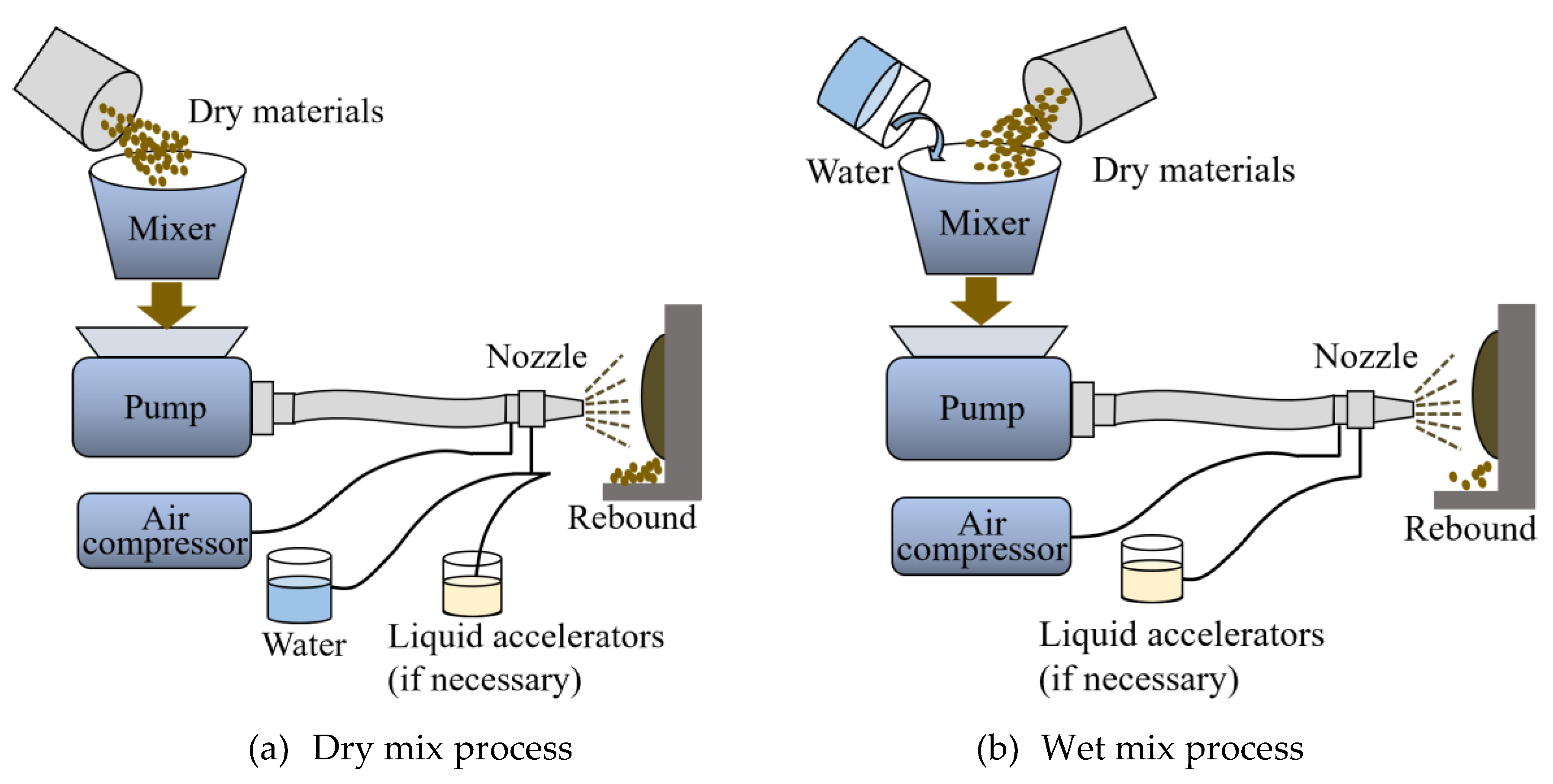

The spraying process can be categorized into dry and wet methods, depending on when water is added and the mixing duration. In dry spraying, dry materials are pneumatically conveyed, and water is introduced at the nozzle, making the mixing quality heavily dependent on operator skill. Wet spraying involves pre-mixing water with dry particles before pumping, producing rapid setting and adequate early strength [5, 6]. Since water is added at the gun outlet during dry spraying, the degree of mixing and homogeneity of the components in the shotcrete during spraying is substantially lower than in wet spraying [

120]. Insufficient air pressure or air volume during the spraying process can reduce spraying speed and quality. Before spraying, the substrate surface should be cleaned to remove contaminants and moistened to minimize over-drying of the substrate and reduce water absorption from the sprayed SHCC. The sprayed SHCC is then pumped through hoses to the spray gun, applied to the substrate, and subsequently smoothed to achieve the desired finish [

121]. The dry and wet mix shotcrete processes are shown in

Figure 13.

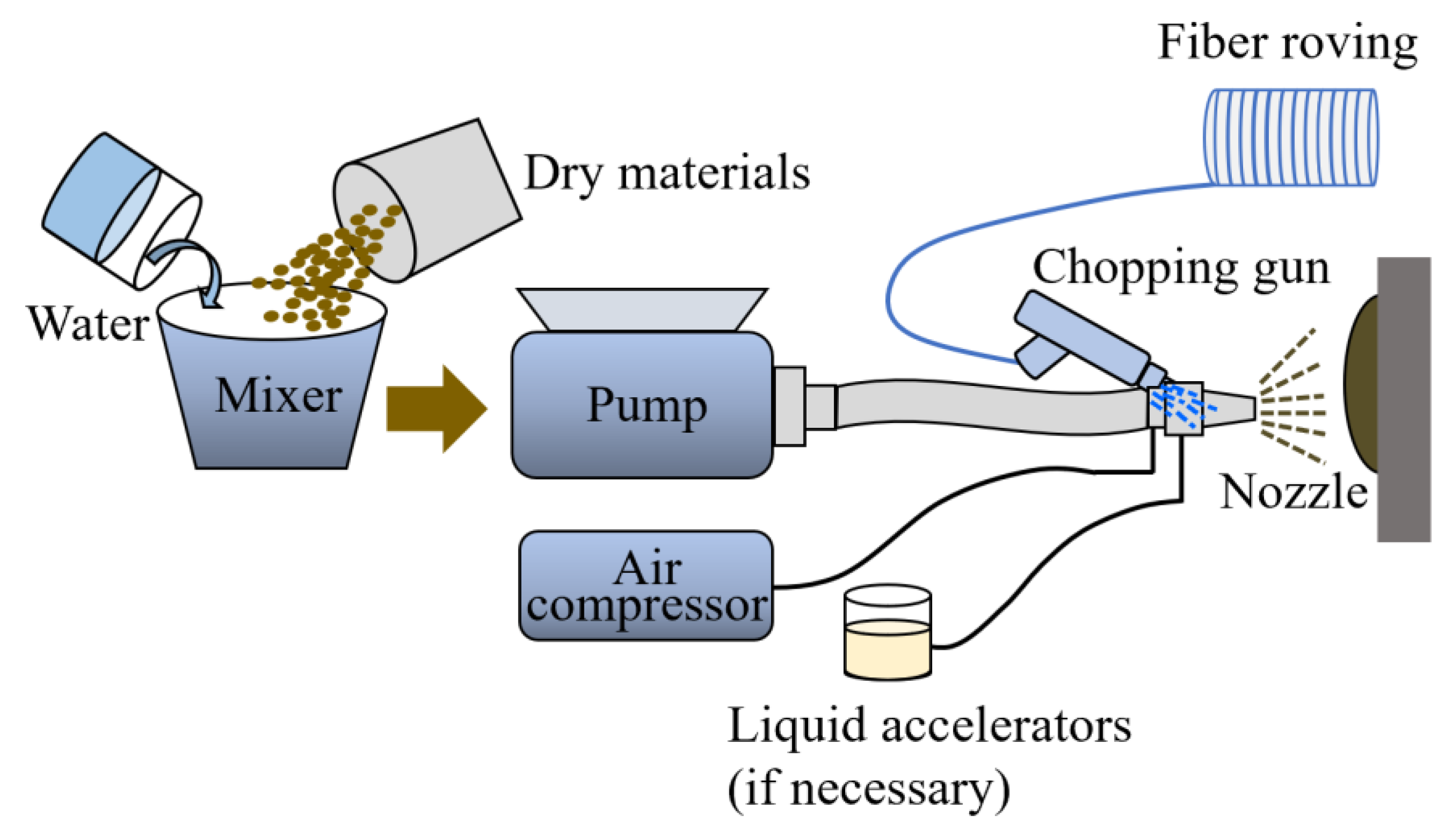

To avoid fiber clogging or pumping difficulties during spraying, some fibers, such as glass fibers, can be cut to the required length using a chopper at the gun nozzle [

122]. The chopped fibers are then sprayed onto the substrate surface in conjunction with mortar directly from the gun, rather than pre-mixing during initial preparation, as shown in

Figure 14. Al-Ameen et al. [

123] used two separate spray guns to introduce fiber addition separately at the head of the spray system. However, their results indicated that human error was inevitable in synchronizing and moving the spray paths, resulting in non-uniform fiber distribution within the matrix. Consequently, a single concentric spray system, which allows fibers and mortar to be sprayed simultaneously, is recommended to achieve more consistent fiber dispersion.

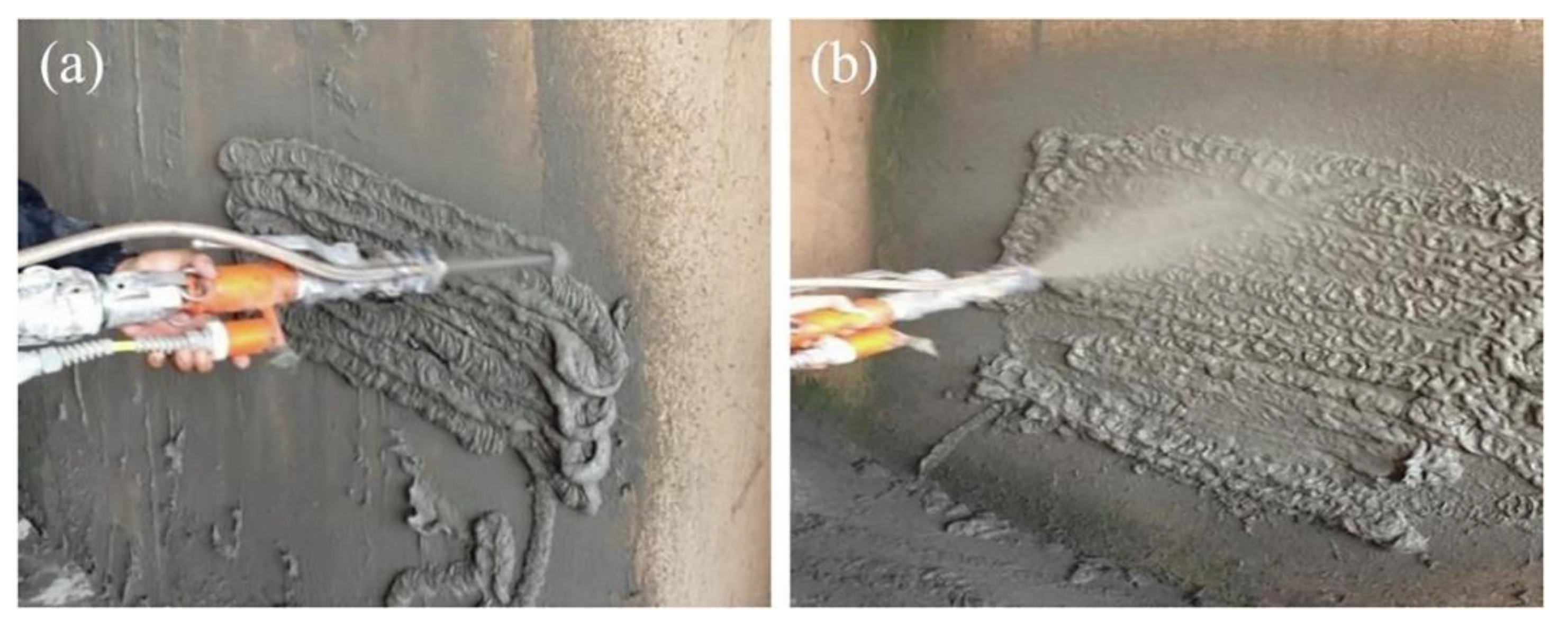

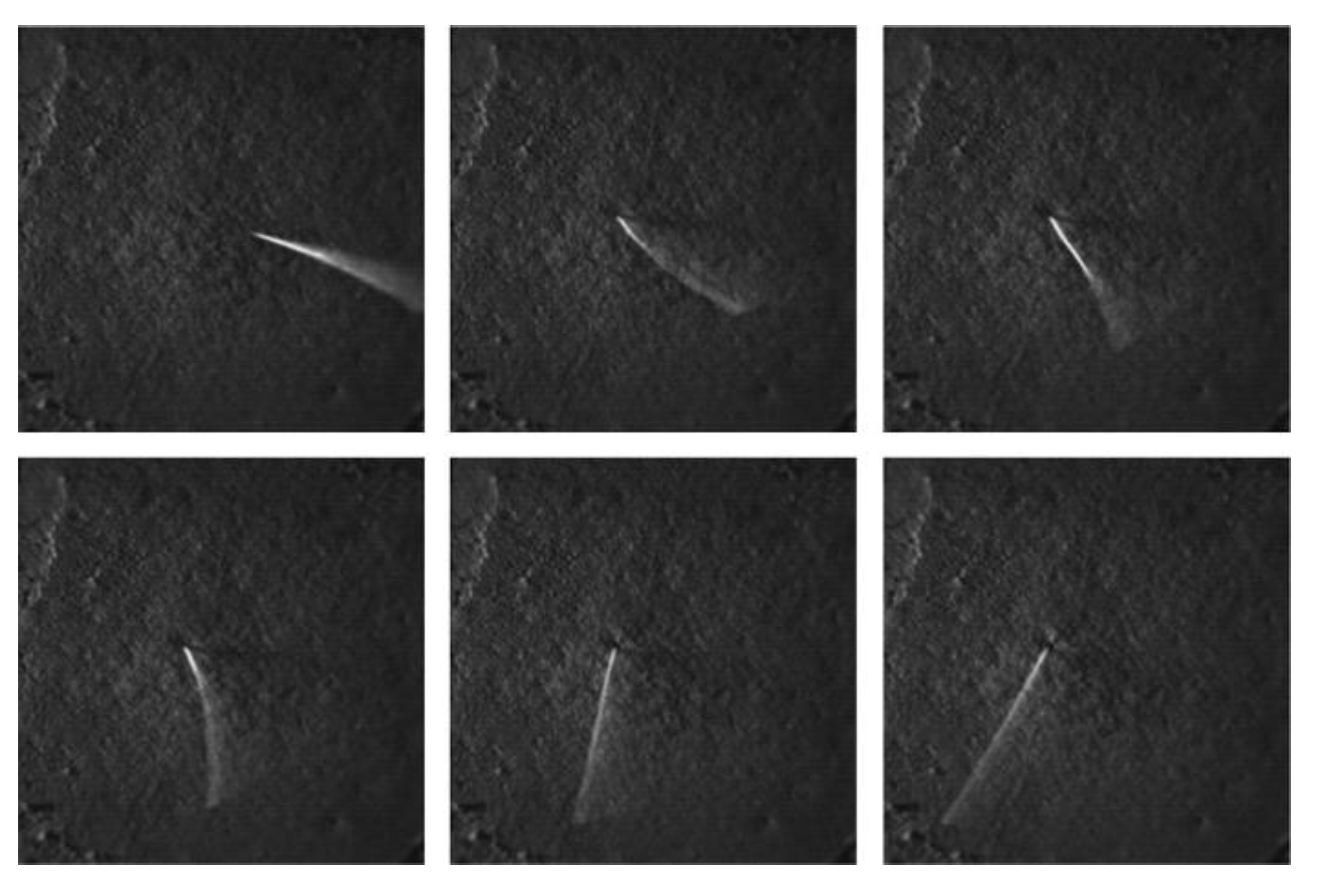

During the construction and maintenance of SHCC, the spraying processes can be selected according to the size of the construction area. Narrow-stream spraying is commonly employed for small construction areas, while fog spraying is preferred for large areas. Huang et al. [

9] reported that narrow streams of sprayed SHCC can be observed at an airflow of about 0.3 m

3/min and air pressure of 200 kPa, whereas fog sprays form at 0.1 m

3/min airflow and 600 kPa air pressure, as shown in

Figure 15. Lukkarila

et al. [

124] suggested that low-speed spraying should be preferred over high-speed spraying for SHCC. It should also be noted that the size distribution of flaws in SHCC can affect its multiple-cracking and tensile strain capacity, although the pneumatic pressure applied during spraying makes flaw size prediction in sprayed SHCC challenging.

Spraying direction also influences the overlay quality. When SHCC is sprayed vertically downward, the combined effects of air pressure and gravity result in a denser overlay on the substrate surface, especially near the interface between the substrate and the overlay. In contrast, overhead spraying creates more pores and interfacial cracks before the overlay hardens [

125]. Due to rebound and potential detachment during the spraying process, the recommended maximum single-layer thickness is 50 mm for vertical spraying and 30 mm for overhead spraying [

9]. Excessive thickness in overhead spraying can lead to immediate spalling or even delamination due to the effects of gravity. When the thickness of the overlay exceeds the maximum thickness of sprayed SHCC in a single continuous spraying, a layered spraying method should be adopted. Xu et al. [

125] reported that 50 mm overhead overlays can be achieved in two 25 mm layers with a 3-hour interval. Lin

et al. [

126] successfully applied 30 mm-thick sprayed SHCC over the wall surface in three separate shots of 10 mm each at 45-minute intervals. Xu et al. [

127] found that increasing the thickness of sprayed SHCC from 10–30 mm improved the ultimate load capacity of the structure by over 30%.

Since there are no standardized thickness and viscosity requirements for sprayed SHCC in substrate covering and reinforcement, mixture design and process parameters are often optimized through iterative experimental adjustments to achieve strong adhesion while minimizing material loss. Before spraying, the proportions of each constituent should be carefully adjusted to prevent hose clogging and reduce waste.

5. Properties of sprayed SHCC

To achieve a consistent overlay of the substrate surface and form a reliable reinforcement or repair layer, it is essential for sprayed SHCC to have excellent flowability and cohesion. This prevents clogging during pumping, ensures strong adhesion to the substrate, reduces sagging, and results in a low rebound rate. For sprayed SHCC, whether using dry spraying or wet spraying, the main goal for sprayed SHCC is to improve pumpability and sprayability, thereby enhancing the mechanical properties and durability of the substrate.

5.1. Pumpability

5.1.1. Pumpability mechanisms and material migration in sprayed SHCC

The pumpability of shotcrete refers to its ability to flow under pressure within a pumping system while maintaining its initial characteristics, emphasizing both flowability and stability [

128]. Good pumpability requires shotcrete to have excellent flowability and stability, pass easily through pipes, and maintain stability without segregation under shear and pressure. Most of the existing studies on pumpability focus on the flow rate of shotcrete in the hose, the diameter of the hose, the pumping distance, the lubrication layer formed on the inner wall of the pipe, rheological properties, and slump [15-17]. The pumping pressure depends on the interfacial friction between the shotcrete and the pipe wall, which is determined by the thickness of the lubrication layer formed inside the pipe wall and the rheological properties, including yield stress, plastic viscosity, and thixotropy. The formula for the pumping pressure inside a shotcrete pipe is shown in Eq. (18) [

129], where

P is the pumping pressure (bar);

L is the length of the pumping pipe (m), and

R is the radius of the pipe (m);

Q is the pumping flow rate of the shotcrete in the pipe (m

3/h);

is the filling factor that depends on the type of pump (0.7 for automatic pumps, 0.8 for stationary pumps);

is the viscous constant (

);

is the yield stress at the interface of the lubrication layer on the pipe wall (Pa).

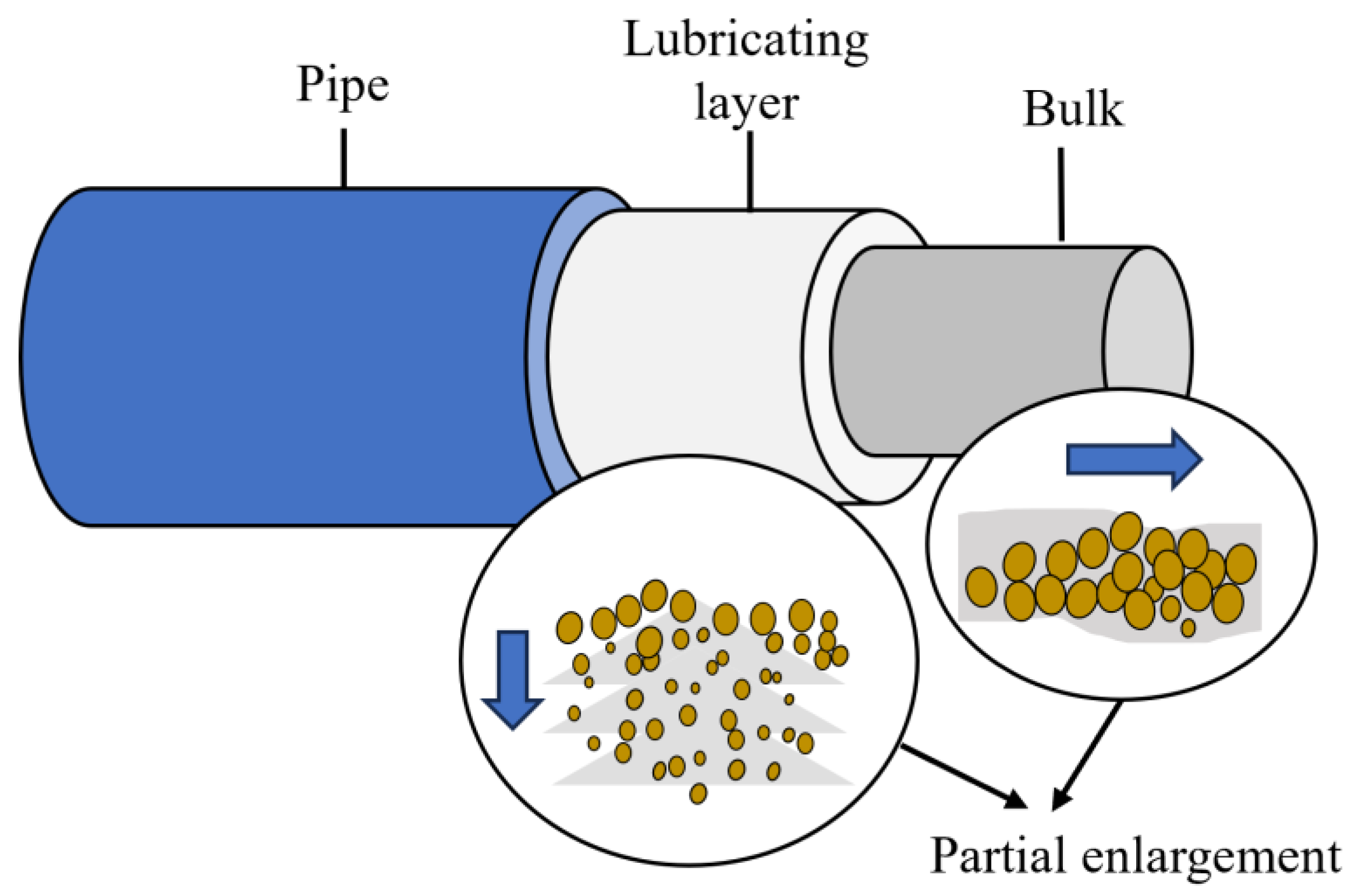

The flow behavior of freshly sprayed SHCC in the pipeline during pumping is complex. As shotcrete is transported from the pipe to the nozzle, segregation between aggregates and paste can occur, resulting from the migration of aggregates from high-shear zones to low-shear zones as shear forces decrease gradually from the pipe wall to zero at the center of the pipe. Coarse particles tend to move toward the center of the pipe due to the wall effect, while finer particles form a lubrication layer around the pipe. This lubrication layer reduces friction and fills gaps between particles, as shown in

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 [130, 131]. According to the principles and hypotheses proposed by Chapdelaine

et al. [

132], a lubrication layer approximately 1 mm thick around the hose forms at the start of pumping. Considering the rheological properties of concrete, pumping sprayed SHCC without a lubrication layer, typically 1–5 mm thick, is generally not feasible [

133].

In addition to the radial separation of aggregate and paste, fibers also experience significant shear-induced migration and orientation evolution during pumping. Their morphological changes directly affect the rheological properties and shear effects of sprayed SHCC. Polymer fibers commonly used in sprayed SHCC, which generally have low stiffness, are more prone to bending and even entangling with each other during concrete pumping, easily forming fiber bundles and orienting along the flow direction. Under continuous shear, coarse particles and long fibers migrate radially, resulting in fiber enrichment in the pipe center and the formation of a fiber-depleted, paste-rich lubrication layer near the pipe wall [

134]. Therefore, a fiber-aggregate ratio imbalance develops within the 1–5 mm lubrication layer adjacent to the wall. When the pumped material passes through sections with changes in pipe diameter, such as nozzles, fiber orientation redistributes, and transient bending or mechanical interlocking can occur, potentially leading to nozzle blockage. Switzer

et al. [

135] simulated frictional interactions between fibers and analyzed the influence of fiber stiffness on the rheological properties of the suspension, showing that suspension viscosity decreases with increasing fiber flexibility. Pu

et al. [

136] concluded that flexible polymer fibers enhance the non-Newtonian effect of concrete and promote particle agglomeration, resulting in plug flow formation. As shear rates increase during pumping, the interfacial shear can exceed the yield stress of the sprayed SHCC, causing the elastic flocculation structure formed by fibers and paste to break down, resulting in shear thinning [

137].

5.1.2. Evaluation of pumpability

The slump test is traditionally used to evaluate the flowability of fresh shotcrete; however, it does not adequately reflect the stability of the sprayed SHCC. Consequently, freshly sprayed SHCC with a good slump does not necessarily meet pumpability requirements [

138]. To more accurately assess pumpability, rheological tests are typically conducted to determine the yield stress and plastic viscosity of the material [

128], and the pressure loss gradient and piston pressure (kPa/m) are measured during the pumping process [38, 131]. The Bingham model is commonly employed to characterize the rheological behavior of fresh concrete, emphasizing that the concrete must overcome the yield stress to initiate flow [

128]. Yun et al. [38, 139] used an IBB rheometer to show that moderate silica fume content can reduce torque viscosity and piston pressure, thereby improving pumpability, whereas fly ash and steel fibers have adverse effects. During sprayed SHCC pumping in the pipe, from the initial low-speed flow stage to the stage where interfacial shear forces exceed the yield stress of sprayed SHCC, the lubricating layer on the inner pipe wall becomes the primary factor influencing pressure loss [

131]. Pumping pressure loss depends on the pipe and lubrication length, rather than the initially applied pressure [

140], and is not influenced by the lubrication layer thickness [

141]. Liu

et al. [

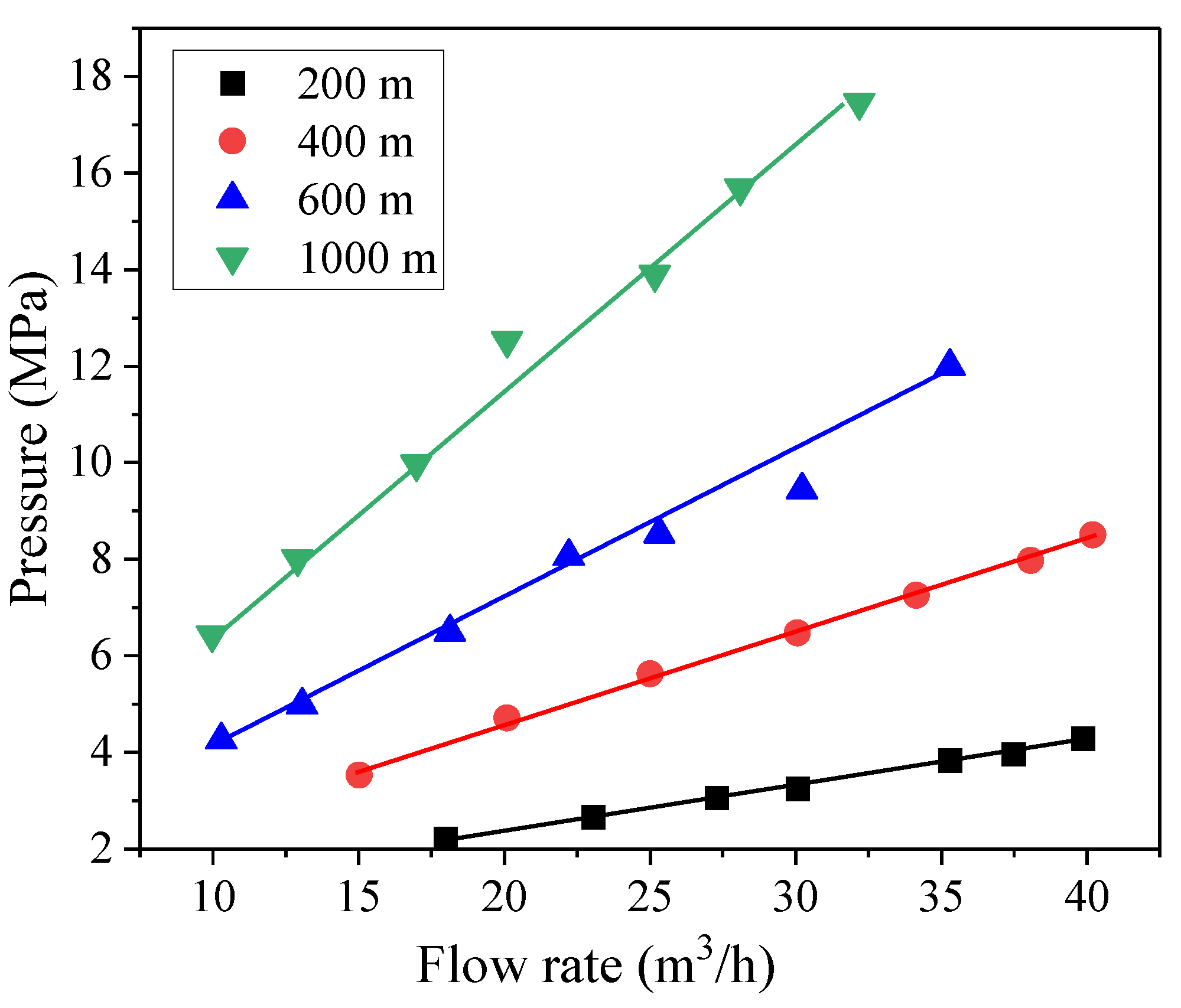

6] confirmed a near-linear positive correlation between plastic viscosity and pumping pressure loss in tests with 25 shotcrete mixes in a 100 m delivery pipe.

Pumpability of sprayed SHCC can be significantly improved by systematically regulating the material composition and construction parameters. For material optimization, sprayed SHCC suspension stability can be enhanced by optimizing the particle size distribution and proportions of silica fume and fly ash, using accelerators to effectively adjust the setting time and rheological properties of freshly sprayed SHCC [

142]. Air-entraining agents can be added to introduce micro-bubbles, which reduce pipe wall friction and compensate for air loss during pumping, thereby maintaining pumpability [143, 144]. The use of smaller and regular-shaped round aggregates improves inter-particle contact and reduces pipe clogging during the pumping process [

120]. For construction parameters, pipe radius, transport distance, and pipe wall roughness strongly affect the pumpability of sprayed SHCC by changing pressure loss, shear rate, and flow resistance during pumping. For example, reducing pipe diameter from 125 mm to 100 mm (about 20% reduction) can double the pumping pressure at the same flow rate [

145]. Increasing the conveying distance increases the required pumping pressure proportionally to maintain the same flow rate, while the pressure drop per unit length remains approximately 12 kPa/m regardless of total pipe length [

146]. The linear correlation between pumping pressure and flow rate at different conveying distances is shown in

Figure 18.

The pumpability of sprayed SHCC is a complex property involving materials science and fluid mechanics. Freshly mixed sprayed SHCC requires high flowability to minimize friction and clogging in the pipe and meet pumping requirements. At the same time, sprayed SHCC also needs sufficient viscosity to adhere to the substrate without falling off under its own weight. Insufficient pumpability of sprayed SHCC or insufficient buildup on the substrate can compromise the durability and mechanical properties of the structure. Therefore, balancing pumpability and sprayability is essential for achieving optimal durability and mechanical performance of sprayed SHCC.

5.2. Sprayability

5.2.1. Evaluation of sprayability

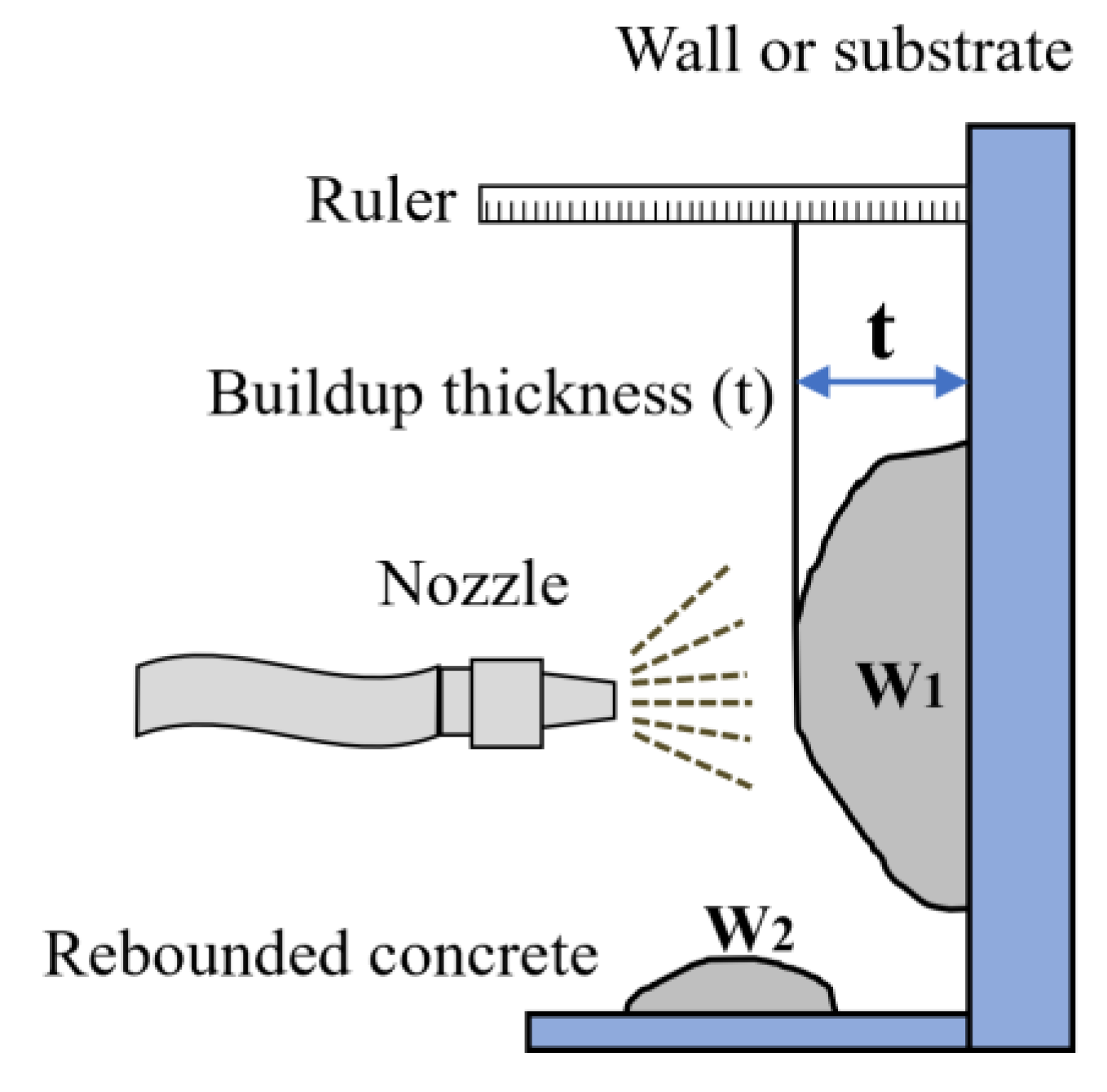

The sprayability of sprayed SHCC refers to its capacity to adhere vertically to the substrate surface after being pumped to the nozzle and sprayed under specific conditions, such as pumping speeds, air pressure, and accelerator dosages. This property is influenced by both the cohesion of the SHCC and its adhesion to the substrate [

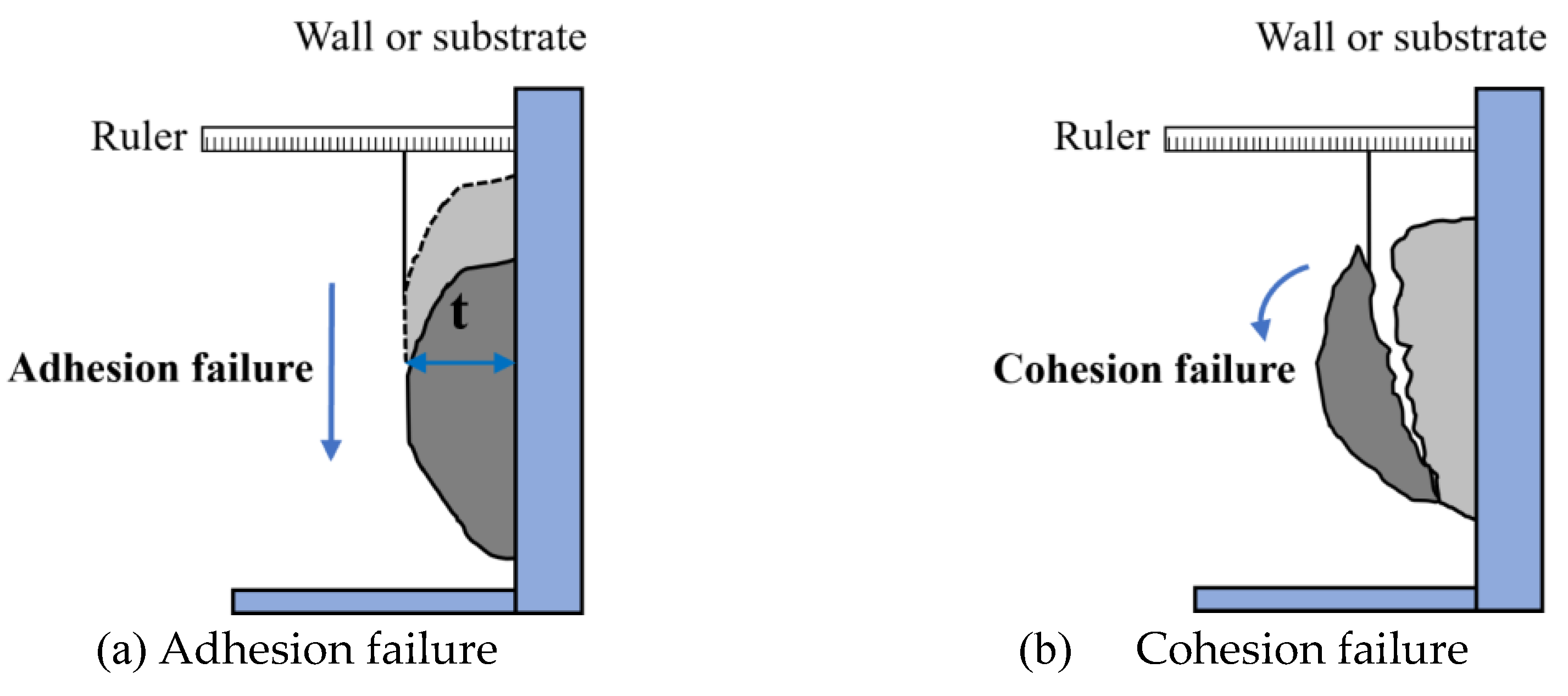

38]. Sprayability is typically evaluated by two indicators: maximum build-up thickness and rebound rate.

The build-up thickness of sprayed SHCC is defined as the thickness of the material sprayed vertically to a specific point on the substrate surface by continuous spraying until the material falls off under its own weight, as shown in

Figure 19 [

14]. It is determined by both adhesion and cohesion. When the adhesion between the sprayed SHCC and the sprayed surface is small, it will slide or fall off along the sprayed surface. When there is insufficient cohesion between the shotcrete paste, sprayed SHCC will be dislodged by its self-weight, as shown in

Figure 20 [

147]. The method of measuring build-up thickness varies with substrate geometry. For substrates with regular shapes, the maximum spraying thickness can first be determined visually and then measured with a steel ruler. Standardized methods for measuring build-up thickness are currently lacking for complex structures such as tunnels. Common approaches include three-dimensional radar dynamic scanning technology, or direct shear methods can be employed to estimate build-up thickness through cohesion measurements [

148].

Rebound rate of sprayed SHCC measures the proportion of material that detaches instead of adhering to the substrate, indicating the self-adhesion of sprayed SHCC and adhesion to the substrate [

11]. A higher rebound rate signifies poorer adhesion of the sprayed SHCC to the substrate. It is measured by placing a rebound collection board on the ground, weighing the fallen material (

W2), and calculating

R from Eq. (19), where

is the rebound rate (%);

is the mass of material adhering to the substrate (g);

is the mass of shotcrete collected on the rebound panel (g). To achieve optimal sprayability, freshly-sprayed SHCC must have a high yield stress to ensure the material adheres to the substrate without detachment while maintaining sufficient flowability for effective pumping and spraying [

14].

5.2.2. Influencing factors

Material composition plays a decisive role in the sprayability of SHCC. Adding silica fume and accelerators effectively improves the cohesion of sprayed SHCC, increasing build-up thickness and reducing rebound [

37]. However, excessive cementitious materials increase the viscosity of sprayed SHCC, reducing flowability and thereby hindering spraying. When the fly ash content exceeds 60%, its large specific surface area leads to significant water absorption, further reducing the free water content in the freshly sprayed SHCC and increasing its viscosity [

14]. Feng

et al. [

14] established a correlation between buildup thickness, rebound, and rheological parameters to identify the optimal ratios for sprayed SHCC mixtures. Yun et al. [

38] found that 4.5% silica fume significantly improves the flow resistance and build-up thickness of sprayed SHCC, and 9% silica fume reduces the rebound rate by approximately 5%, with the rebound rate almost inversely linear with the build-up thickness. Furthermore, the sprayability of sprayed SHCC can be effectively tailored through various chemical admixtures. Incorporating air-entraining agents into sprayed SHCC enhances the flowability of freshly sprayed SHCC via the ball-bearing effect of entrained air voids, thus improving pumpability. However, the release of entrained air during the spraying process increases the yield stress and reduces the flowability, which in turn enhances build-up thickness [6, 149]. In addition, rapid-setting accelerators (e.g., CSA cement) create overly short working times; however, retarders (e.g., citric acid) can effectively adjust the setting time by forming protective films on cement particle surfaces that retard the degree of cement hydration, thereby achieving ideal build-up thickness [

150].

Fiber rebound in sprayed SHCC fundamentally determines material performance through mechanisms that vary significantly between fiber types. The phenomenon occurs when relatively high impact velocities prevent complete adhesion of matrix and fibers to substrate surfaces, with the governing parameters including fiber stiffness, aspect ratio, and fresh-mixture rheology [

10]. Notably, sprayed SHCC containing synthetic fibers exhibited significantly superior build-up thickness compared to steel fibers. Studies have shown that fiber rebound losses in steel fiber-reinforced shotcrete can reach up to 44% by fiber mass due to their inherent high stiffness and resulting rigid impact characteristics [

10]. Upon substrate impact, steel fibers demonstrate superior momentum transfer efficiency that stores energy as elastic deformation, subsequently releasing this energy to drive fiber rebound from the matrix surface. Research has established clear relationships between steel fiber properties and rebound magnitude. Bindiganavile

et al. [

151] found linear increases in rebound with fiber length and maximum aggregate size, with particularly severe effects on vertical and overhead substrate surfaces. Mitigation strategies include fine powder additions such as metakaolin, fly ash, or micro silica. However, Austin

et al. [

152] indicated that while fiber dosage, fiber geometry, or fiber mass show minimal influence on shotcrete rebound, fiber length remains critical, with each 1 mm increase corresponding to 2%–5% higher rebound rates.

In contrast, sprayed SHCC containing synthetic fibers exhibits markedly reduced rebound compared to steel fiber-reinforced shotcrete. Badr and Brooks [

153] measured fiber rebound rates of only 5%–9% in PP fiber-reinforced sprayed SHCC, which is attributed to the lower flexural rigidity and higher surface roughness of the fibers that facilitate in-situ embedding and mechanical anchorage with the substrate. Similarly, sprayed SHCC containing 2 vol% PVA fibers achieved rebound rates of approximately 11%, substantially lower than comparable steel fiber-reinforced shotcrete [

75]. This performance advantage results from the complex dynamic response of polymer fibers upon impact. The polymer fibers initially exhibit small-amplitude high-frequency oscillations followed by large-amplitude tail swinging, which sequentially dissipates the fiber impact kinetic energy, as shown in

Figure 21 [

10].

The complex interplay between polymer fiber properties and fresh-mixture rheology creates conditions more favorable for fiber retention and reduced rebound losses. The interlocking mechanism between the fibers and aggregates serves to diminish the flowability of the SHCC. However, the hydrophilic nature of PVA fibers enhances the consistency of the paste by binding water molecules to their surface [

154]. Therefore, PVA fibers contribute to an enhancement in the adhesion of sprayed SHCC to the substrate to some extent. Feng et al. [

14] found that the build-up thickness of sprayed SHCC initially increases and then decreases as the content of PVA fiber gradually increases. In contrast, the rebound rate exhibited an initial decrease followed by an increase. The optimal sprayability of sprayed SHCC was observed at 2 vol.% fiber content. Unlike the random fiber distribution in cast SHCC, fibers in sprayed SHCC tend to align more vertically in the direction of spraying due to the pneumatic effect and gravity [

10].

5.3. Flexural and tensile strengths of sprayed SHCC

Sprayed SHCC, as a reinforcement layer on structural surfaces, is mainly subject to in-plane and out-of-plane tensile and bending loads. When the substrate structure is deformed or cracked, the crack resistance, ductility, and energy absorption capacity of sprayed SHCC become the key factors determining the effectiveness of the reinforcement. In contrast, since the substrate structure usually already has sufficient compressive capacity and the sprayed SHCC layer is thin, its compressive performance has a relatively limited contribution to the overall structural reinforcement effect. Therefore, the tensile properties and flexural strength of sprayed SHCC are of more concern than compressive strength.

5.3.1. Specimen preparation and size requirements

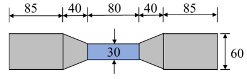

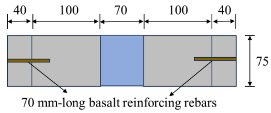

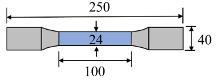

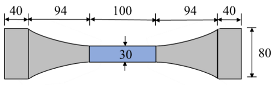

Typically, test specimens for sprayed SHCC are obtained by cutting the SHCC panels sprayed on the surface of a substrate. The preparation of sprayed SHCC samples typically involves spraying SHCC onto molds or substrate surfaces, curing to the appropriate age, and then cutting it to suitable dimensions according to test size requirements. Three-point bending and four-point bending tests are commonly used to evaluate the maximum flexural strength, fracture toughness, multiple cracking behavior, and strain-hardening properties of SHCC [

155]. Currently, there is no fixed specimen size requirement for flexural testing, but according to the recommendations of ASTM C1609 [

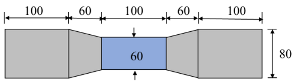

155], the ratio of span (L) to height (h) is typically maintained at 4:1 or greater to ensure that shear forces do not dominate the failure mode in flexural testing. The specimen thickness should also be at least three times the fiber length to avoid fiber orientation effects. Uniaxial tensile testing is the method by which the tensile properties of SHCC can be directly determined. Commonly used SHCC tensile tests require specimen sizes and shapes, as shown in

Table 2. According to the recommendations of the Japan Society of Civil Engineers (JSCE) [

156], spraying SHCC into commonly used molds resulted in the SHCC failing to compact properly at the edges of the molds. Therefore, cutting the sprayed SHCC into dog-bone, rectangular, and circular bar specimens is more feasible after curing is completed. Lin

et al. [

157] showed that circular bar-shaped samples proved to be the most practical shape for tensile testing because the sample had the least variation in size and the least fluctuation in test results.

5.3.2. Influencing factors

The flexural and tensile properties of sprayed SHCC are influenced by a combination of factors, including matrix rheology, fiber characteristics, raw material composition, spraying process parameters, environmental conditions, and interfacial behavior. Matrix rheology is a key determinant of pumpability, sprayability, and atomization quality. Maintaining a deformability index between 1.8 and 2.5 has been shown to minimize air entrapment and void formation, thereby enabling stable strain-hardening behavior with multiple cracking [

39]. Fiber type, dosage, and spatial orientation exert a decisive influence on both flexural and tensile responses. Huang

et al. [

9] reported that sprayed SHCC with 2% PVA fibers achieved a 28-day tensile strength of approximately 2.5 MPa, an ultimate tensile strain of 0.75%, and a flexural strength of about 11 MPa. Zhang and Li [

65] developed a spray-applied fire-resistive SHCC incorporating vermiculite and HTPP fibers, which exhibited a tensile strength of 0.87 MPa and a strain capacity of 1.0%. Hu

et al. [

75] used desulfurization gypsum and an expansion agent to reduce the shrinkage of sprayed SHCC, and incorporated 1% PVA and 1% PP fibers to make sprayed SHCC with an ultimate tensile strain of 1.19% by utilizing the fiber hybridization effect, with its stress-strain curve as shown in

Figure 22 [

75].

During spraying, high-velocity airflow tends to align fibers along the spray direction, increasing the fiber orientation coefficient. When the loading direction is parallel to this primary fiber orientation, crack-bridging efficiency improves, resulting in higher flexural strength and more effective crack control. Hung

et al. [

18] used X-ray computed tomography to characterize fiber distribution in sprayed SHCC and found anisotropic flexural behavior, with specimens loaded parallel to the spraying direction exhibiting up to 70% greater flexural strength than cast SHCC. This enhancement was attributed to the preferential fiber alignment in the spraying plane and to local variations in fiber packing density caused by wall effects, gravity, and rebound, which can lead to non-uniform fiber distribution in different regions of sprayed SHCC. A similar anisotropic effect has been reported in centrifugal spraying. Zhu

et al. [

158] showed that centrifugally sprayed SHCC exhibited direction-dependent tensile behavior, with circumferential specimens (CS-C) achieving 5.7 MPa tensile strength and 5.3% strain capacity compared to longitudinal specimens (CS-L) showing reduced values of 4.7 Mpa and 2.2%. This anisotropic performance was attributed to preferential circumferential fiber alignment during centrifugal spraying, which reduces fiber bridging in the longitudinal direction and consequently lowers tensile strength and ductility. Binder composition plays an equally important role. In calcined clay limestone cement (LC3) systems, the formation of highly polymerized C-A-S-H gel and abundant ettringite has been shown to enhance flexural performance [

159]. Zhu et al. [

39] developed sprayed SHCC incorporating LC3 and CSA additives, which exhibited improved ductility and superior crack control. Spraying parameters, such as air pressure, nozzle configuration, and spray direction, indirectly affect both flexural and tensile behavior by influencing atomization quality, fiber dispersion, and interlayer bonding between the sprayed overlay and substrate. Temperature affects hydration rate, microstructural densification, and fiber-matrix interface performance, with curing at 40 °C reported to improve the deformability of sprayed SHCC [

160]. Key factors affecting the flexural and tensile properties of sprayed SHCC are summarized in

Table 3.

5.3.3. Comparison with cast SHCC

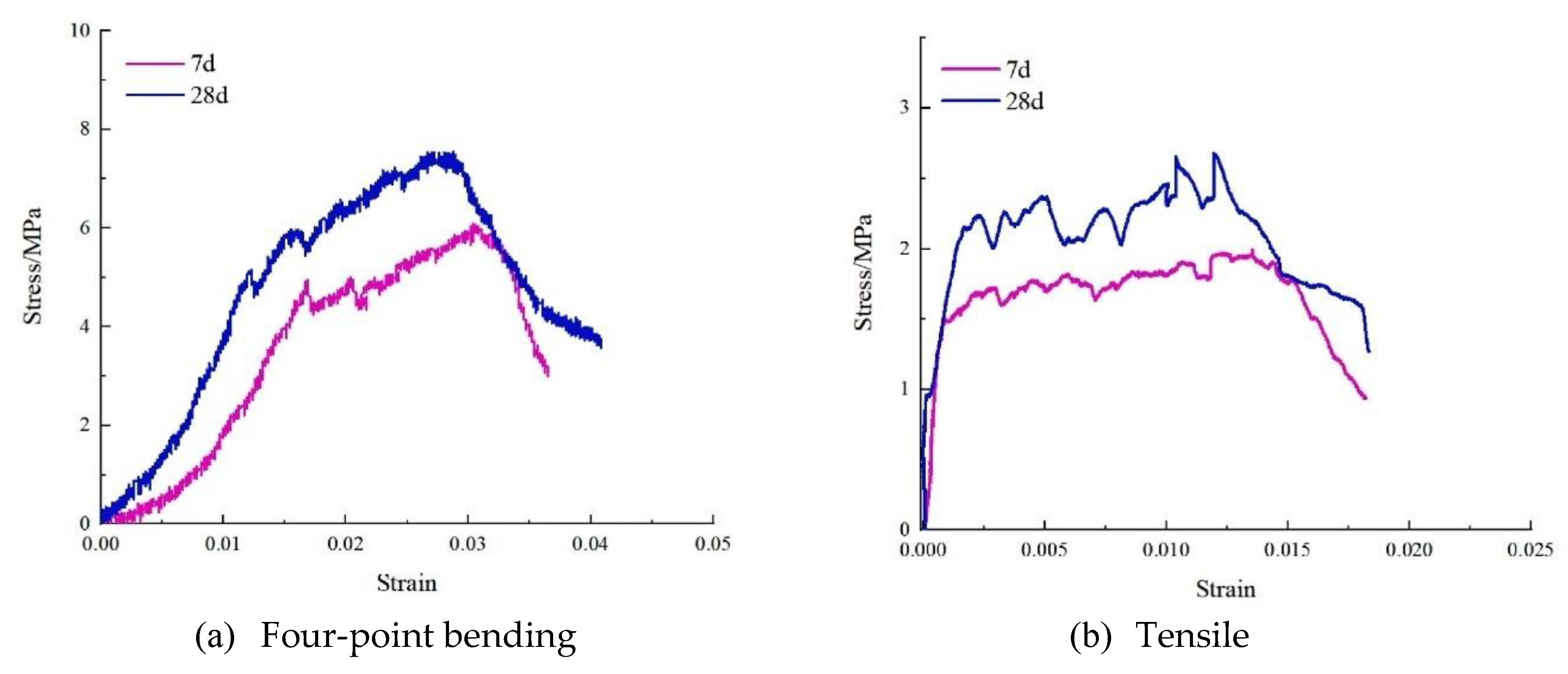

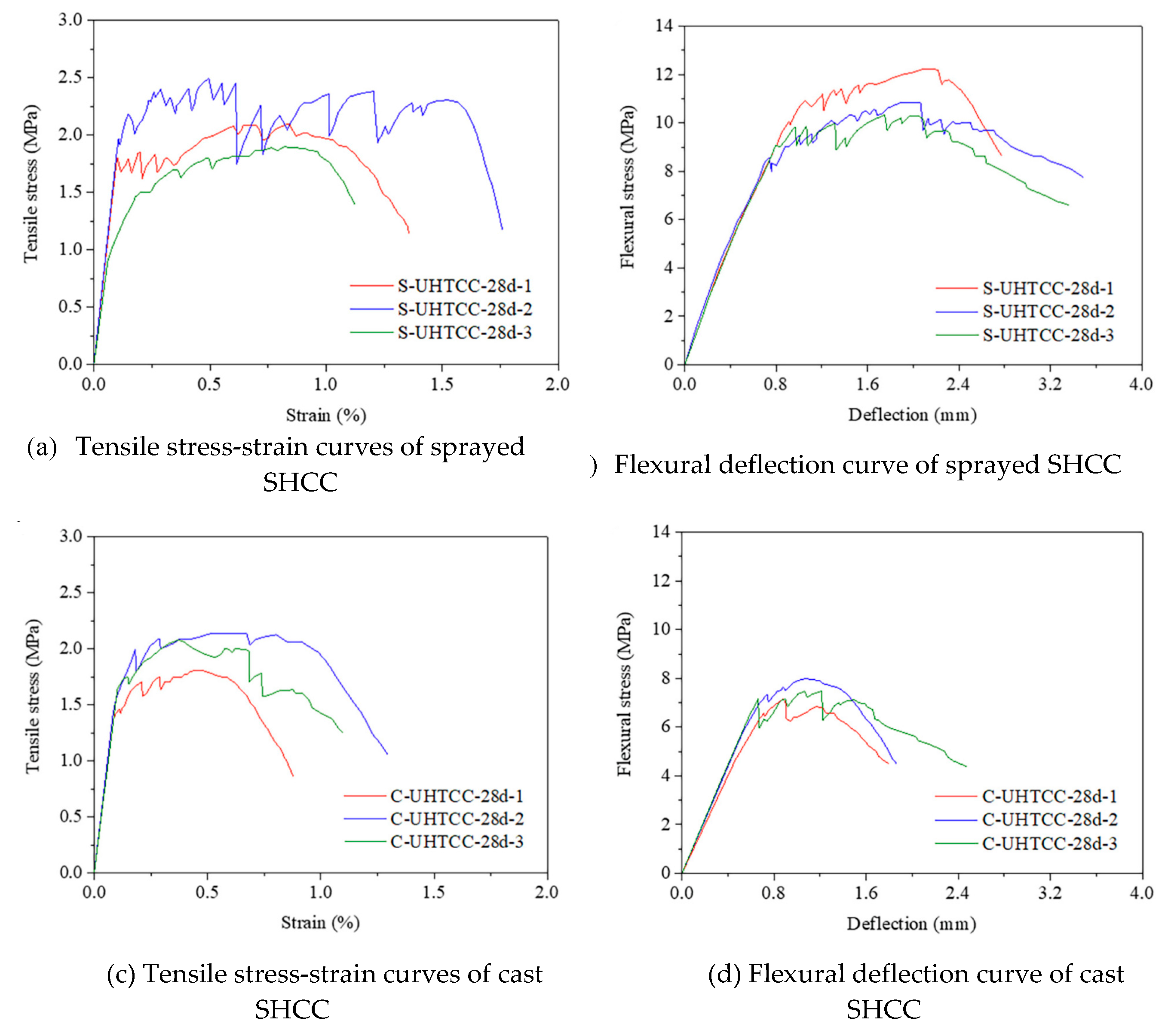

Huang et al. [

9] cut specimens with dimensions of 40 mm (W) × 40 mm (D) × 160 mm (L) and 50 mm (W) × 15 mm (D) × 300 mm (L) from sprayed panels to evaluate the flexural and tensile strengths of the sprayed SHCC, respectively. As shown in

Figure 23, the results demonstrated that the tensile strength, tensile strain capacity, and flexural strength of sprayed SHCC at 28 days of curing were higher than those of cast SHCC. Different engineering applications prioritize different material performance requirements. Cast SHCC is mainly used in tensile members in structural elements due to its tensile strain-hardening and multiple cracking characteristics, while sprayed SHCC needs excellent surface bonding performance and out-of-plane flexural capacity to strengthen composite material structures effectively. Huang

et al. [

9] and Banthia

et al. [

161] found that while the compressive strength of cast SHCC was generally higher than that of sprayed SHCC, sprayed SHCC exhibits superior flexural strength and tensile properties than cast SHCC. Due to the high requirements for crack resistance and durability in structural repair and reinforcement projects, sprayed SHCC has a higher energy absorption capacity and toughness than cast SHCC, making it more suitable for the engineering needs of composite material structures [

120]. However, the comparative performance between cast and sprayed SHCC is influenced by multiple factors. Zhang and Li [

65] reported that while the first crack strengths of cast and sprayed SHCC were similar, the sprayed specimens exhibited lower ultimate tensile strength and reduced ductility. This reduction was mainly due to changes in fiber orientation during spraying, as fibers in cast specimens tended to align longitudinally due to mold restraint. Kim

et al. [

162] demonstrated that with sufficient compaction during the wet-mix spraying process, the ductility and tensile strength of sprayed SHCC can be comparable to those of cast SHCC specimens, which is most likely due to the pneumatic compaction during the wet-mix spraying process.

5.4. Interfacial bonding properties and shear-slip behavior of sprayed SHCC

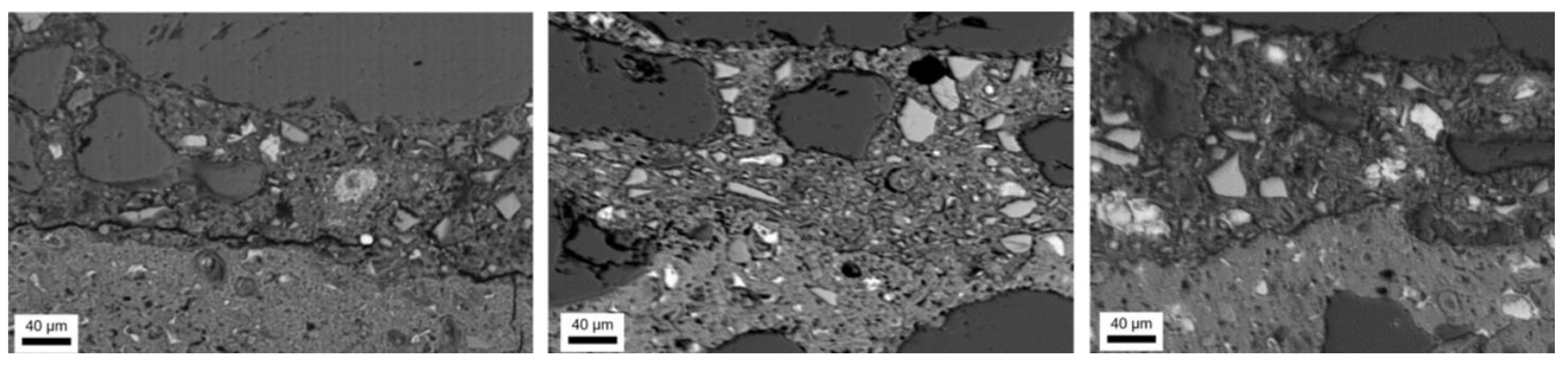

5.4.1. Transition Zone between substrate and reinforcement

The interfacial bonding behavior between the sprayed SHCC and the concrete substrate influences the effectiveness of sprayed SHCC in structural repair and reinforcement. This interface, known as the Overlay Transition Zone (OTZ), tends to be the weakest part of the composite structure. Beushausen et al. [

19] found that the OTZ is enriched with hardened cement paste and anhydrous cement particles, typically around 100 μm thick, characterized by high porosity and low strength. As can be seen in the SEM images of the OTZ in

Figure 24, there is a thin layer of hardened paste and anhydrous cement particles in the OTZ, with particles having sharp edges and sizes up to 30 μm. The interface exhibits wall effects between the aggregates and anhydrous cement particles, which disrupt optimal particle packing and lead to higher porosity [

163].

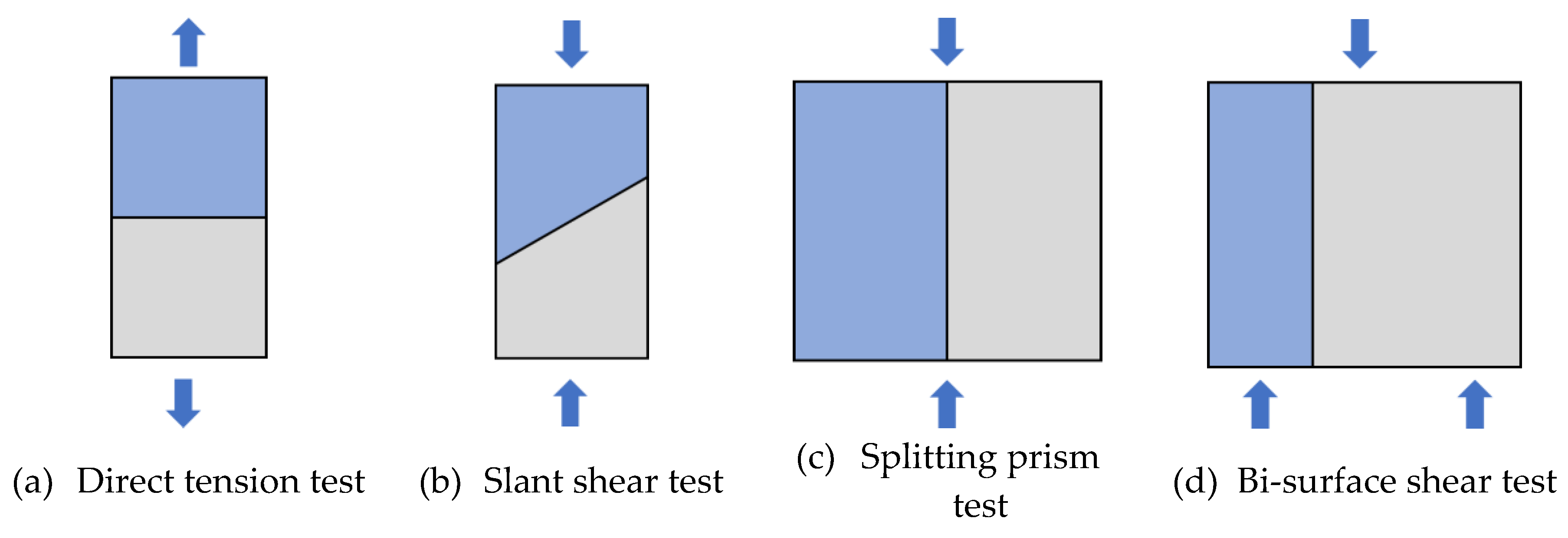

The bonding properties of OTZ are crucial for the strength and durability of the composite. Test methods for measuring interfacial bonding performance are limited for sprayed SHCC compared to cast SHCC. Cast specimens can be formed into various shapes using different molds. However, sprayed specimens cannot achieve precise positioning even with molds due to the spraying process. The standard test methods include direct tension tests, slant shear tests, splitting prism tests, and bi-surface shear tests, as shown in

Figure 25. Manawadu

et al. [

164] compared these methods and found that slant shear performance depends on the bonded area and contact area, where increasing the interface bonding angle increases the risk of mixed failure mode. Although tensile pull-off tests provide the most direct measure of bond strength, the coefficient of variation of the test results is significant. Pulkit

et al. [

165] found that pull-off tests typically produce the lowest values, while slant shear tests provide the highest values. This is because the compressive stresses in slant shear tests offer additional friction and interlocking, increasing the failure load.

5.4.2. Interface failure mode and shear slip behavior

The interface failure mode and shear slip behavior between sprayed SHCC and concrete substrate are complex, primarily experiencing four typical stages. In the initial stage, stress concentration occurs at the interfacial unevenness, and microscopic cracks are formed under the critical shear stress. Subsequently, the microcracks propagate stably under shear loading, and pores in the OTZ promote the development of crack connectivity. When shear stress reaches the interface bond strength threshold, cracks accelerate and gradually penetrate through the OTZ, at which point relative shear slip occurs between the substrate and sprayed SHCC. Finally, the residual shear strength is jointly controlled by mechanical interlocking provided by interface roughness and fiber bridging effects, ultimately leading to interface failure [

7]. The failure of sprayed SHCC as an overlay reinforcing substrate is mainly caused by interfacial debonding, stripping failure, and the failure of the protective concrete layer. Under large bending loads, interfacial debonding may initiate near the bending cracks, where the stress concentrations are highest [

127]. Kim

et al. [

162] investigated the behavior of sprayed SHCC-repaired beams under bending loads. The results showed that the sprayed SHCC exhibited strong interfacial properties and excellent energy absorption, with no interfacial debonding observed in the OTZ. The shear slip behavior between sprayed SHCC and substrate can be assessed using the triplet shear test, where the substrate exhibits Coulomb-friction behavior under shear loading [

22]. The interfacial shear experiments between the sprayed SHCC and the substrate can be divided into two stages. In the initial stage, the interfacial shear stress increases linearly with the tangential relative displacement. In the second stage, the interfacial shear stress gradually decreases as the tangential relative position increases. Van Zijl [

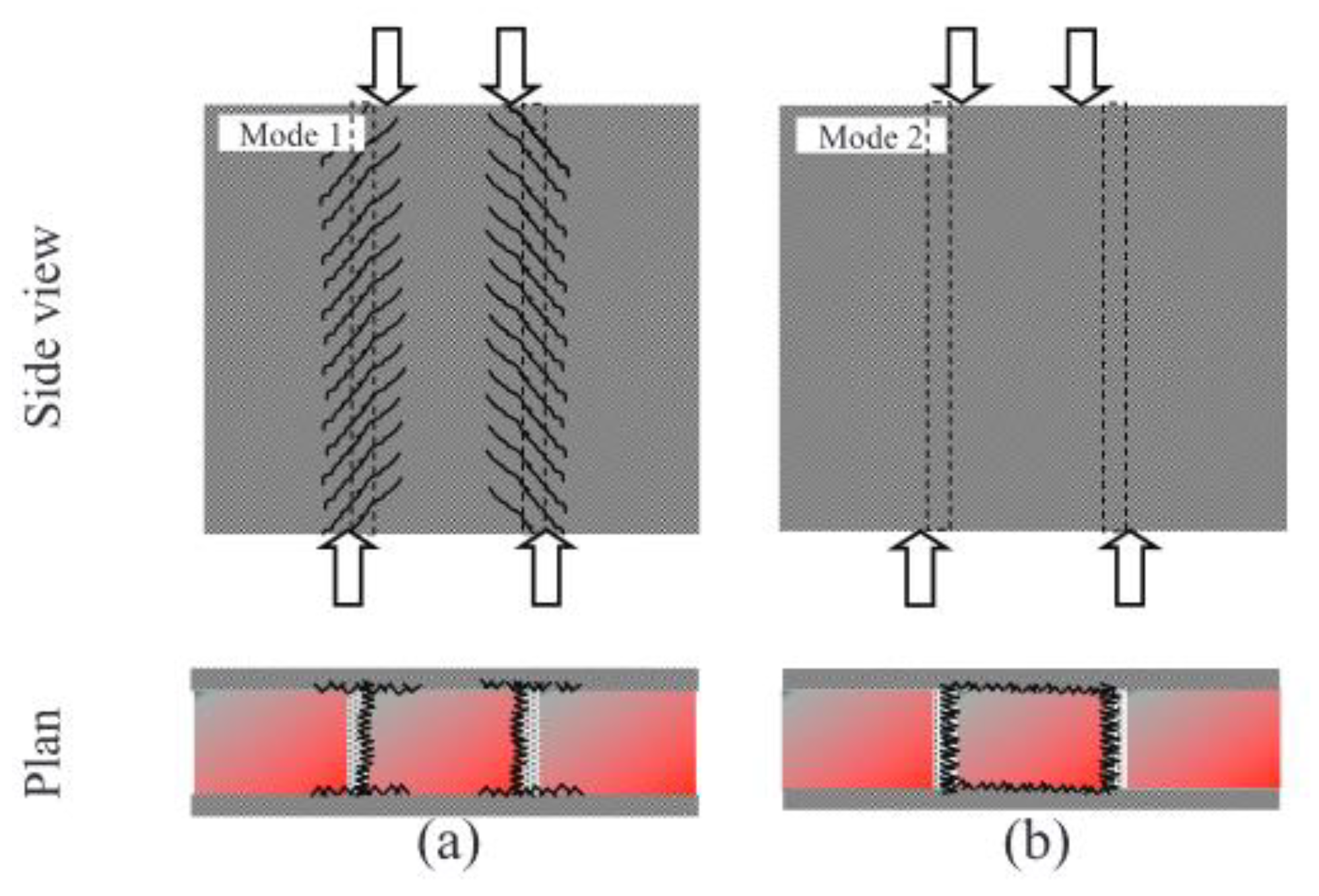

21] conducted joint shear slip experiments after spraying SHCC as a cover layer on the surface of masonry wall structures. The results showed that the initial crack formation led to the alignment of the main cracks with the rotational cracks, increasing the compressive stresses and promoting crack expansion. This enhanced the multiple cracking characteristics of sprayed SHCC, ultimately resulting in a higher ultimate shear strength than tensile strength in the composite structure. Under shear loading, the damage modes of the sprayed SHCC and concrete substrate were categorized into multiple cracking on the surface of the composite structure and overall debonding at the interface, as shown in

Figure 26.

5.4.3. Influencing factors

The main factors affecting the interfacial bond between the concrete substrate and sprayed SHCC include the construction process, surface roughness, wetting condition of the substrate surface, type of cementitious material, curing conditions, flowability, and compressive strength of sprayed SHCC [19, 20]. Van Zijl [

21] replaced more than 10% of CEM I 52.5 cement with calcium aluminate cement (CAC), which improved the adhesion of freshly-sprayed SHCC to the substrate. Dry substrate surfaces are not conducive to improving bond properties in the OTZ, as concrete substrates with lower water-to-cement ratios tend to absorb more water from the overlay, thereby reducing the water available for the hydration reaction of the cement in the OTZ and weakening mechanical interlocking between the overlay and substrate [

19]. However, sprayed SHCC with excessive flowability may also cause shrinkage and stress concentration after hardening, resulting in cracks at the interface zone [

20]. Additionally, the lower aggregate content in sprayed SHCC cannot effectively constrain shrinkage after SHCC hardening. If the relative shrinkage at the interface exceeds the maximum tensile cracking strain of sprayed SHCC, it may lead to larger crack formation and ultimately result in interface debonding [

21]. The bond strength between overlay and substrate is significantly affected by interface roughness, texture, and spraying direction of SHCC. Sand blasting the concrete substrate has been used to reduce the risk of delamination between the overlay and the concrete substrate while significantly increasing the shear and tensile strengths of the composite structure [

163]. In general, upward spraying leads to the poorest bonding performance of OTZ [

125]. For overhead spraying, the thickness of each spray should not exceed 25 mm. Otherwise, spalling of the overlay SHCC may occur. When no slip occurs between sprayed SHCC and substrate, the bonding at the overlay-substrate interface is controlled by chemical bonding forces, van der Waals forces, and mechanical interlocking forces. However, when slippage occurs, the interfacial bonding is maintained by mechanical interlocking [

166]. Key factors affecting the interfacial bond behavior of sprayed SHCC are summarized in

Table 4.

5.4.4. Comparison with other concrete

The bond-splitting tensile strength in the interface of the concrete substrate and sprayed SHCC is almost 1.5 times that of conventional concrete [

125]. This strength increases with the surface roughness of the concrete substrate, while the variation in the bond strength to the interface is relatively small. However, once the surface roughness of the concrete substrate reaches a certain level, further increases do not enhance bond strength [

167]. Studies by Tian et al. [

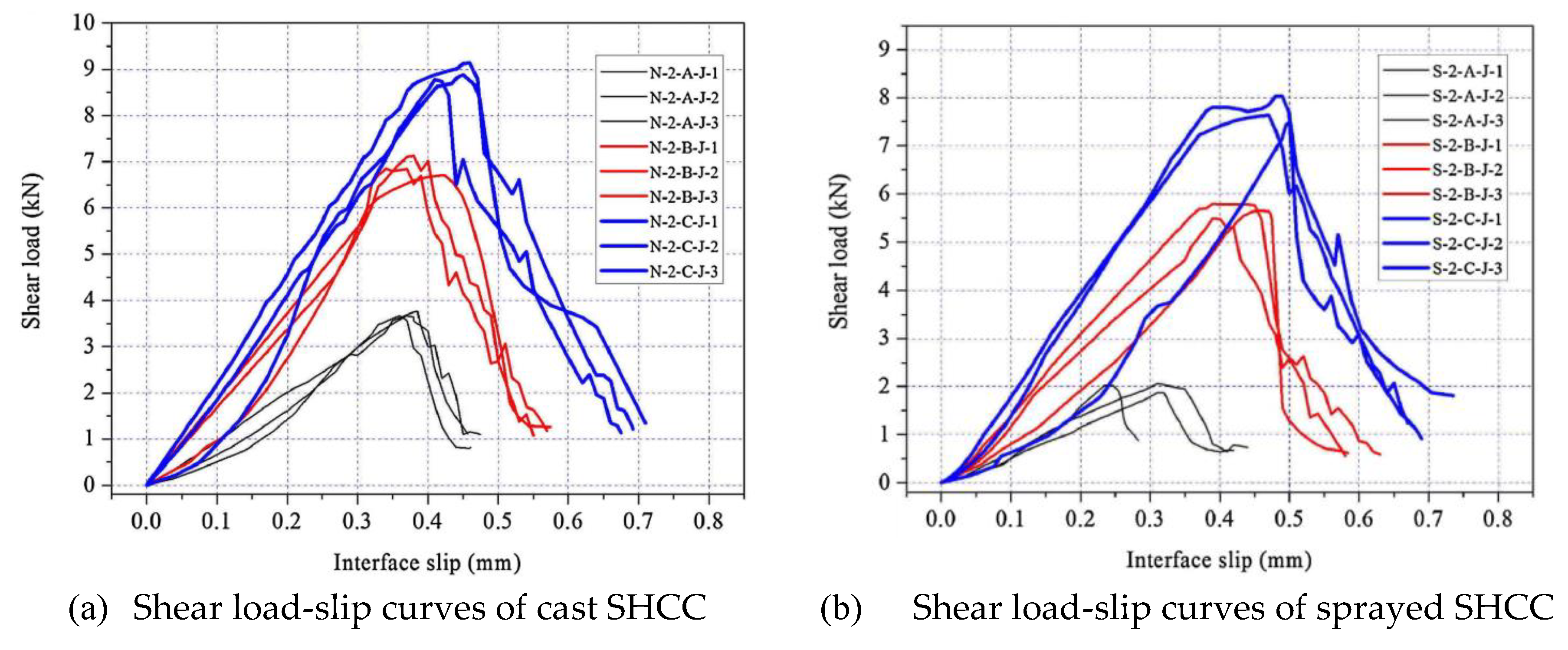

166] revealed that the shear load-slip curve of sprayed SHCC remains unchanged compared to cast SHCC, although the interfacial shear strength of sprayed SHCC is notably lower, as shown in

Figure 27.

6. Application of sprayed SHCC

As a structural reinforcement material, sprayed SHCC combines the construction convenience of shotcrete technology with the excellent strain-hardening and multiple-cracking properties of SHCC materials. Compared to ordinary shotcrete, sprayed SHCC forms numerous fine cracks rather than a single penetrating crack under tensile stress, significantly improving the deformation capacity and energy absorption performance of the reinforcement layer, making it particularly suitable for reinforcing structures subjected to dynamic loads, seismic effects, or uneven settlement. Meanwhile, its micro-crack control characteristics improve the durability of the reinforcement layer, extend the maintenance cycle, and reduce life cycle costs. These combined advantages make sprayed SHCC ideal for repairing aging structures, seismic reinforcement, and protecting structures in special environments.

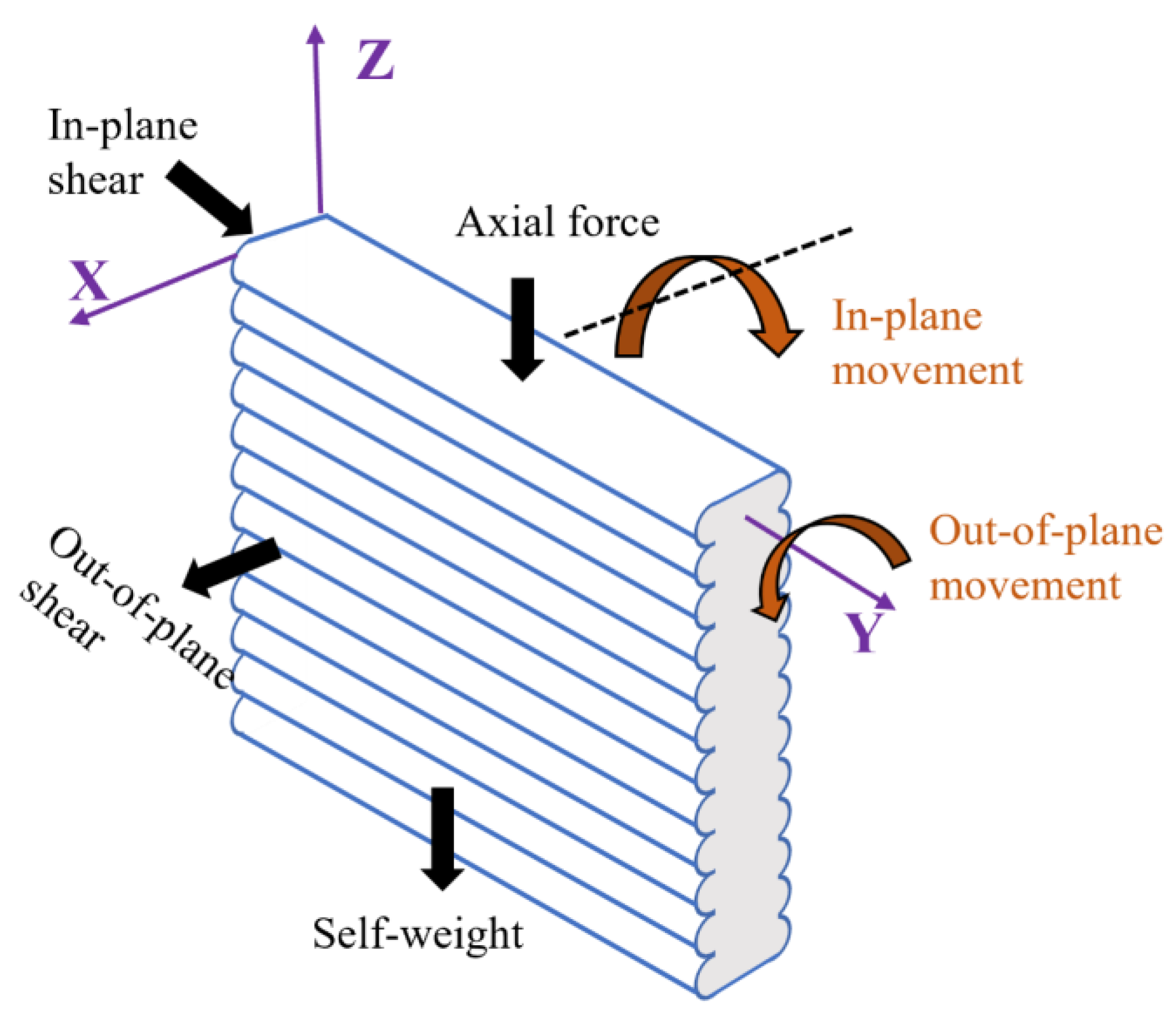

Wall shear reinforcement is a key application of sprayed SHCC, effectively enhancing structural performance when applied as an overlay. Sprayed SHCC significantly improves both the in-plane and out-of-plane tensile and flexural strengths of walls, effectively controlling displacement and deformation [

157]. Van Zijl

et al. [

7] used sprayed SHCC to retrofit unreinforced load-bearing masonry structures, tested the mechanical properties and free shrinkage of composite structures, and found that masonry structures covered with 30 mm of sprayed SHCC showed 6.7 times improvement in shear strength and energy absorption capacity. Similarly, Lin

et al. [

126] sprayed a 30 mm thick layer of SHCC on the wall surface to reinforce the masonry. The results from monotonic and cyclic lateral load tests showed that the out-of-plane tensile strength of the reinforced masonry increased by up to 1267%. In this case, the sprayed SHCC acted as a tensile member while the masonry functioned as a compressive member. Lin et al. [