1. Introduction

Warthin’s tumors are characterized by papillary, cystic, or tubular growths of epithelial cells, mainly oncocytes, along with lymphoid stroma. They are the second most common benign salivary gland tumors after pleomorphic adenoma, accounting for about 10% of all salivary gland tumors. Their occurrence is almost exclusively limited to the parotid gland and surrounding parotid lymph nodes. They are more common in elderly men and are strongly associated with smoking. They present as soft, slow-growing nodular lesions. They are often bilateral or multiple, and malignant transformation is extremely rare. It is believed that with a reliable diagnosis, Warthin’s tumors can often avoid surgical intervention [

1]. However, in practice, fine-needle aspiration cytology has been reported to misdiagnose about 3%–8% of cases as other histopathologic types [

1,

2,

3].

Recent studies have shown that periostin expression is significantly higher in cardiac disease and the majority of cancer tumor tissues than in normal tissues [

4]. Periostin is overexpressed in a variety of solid epithelial tumors. Periostin directly influences cancer characteristics through its interaction with cell surface receptors, integrins, which regulate intracellular signaling pathways [

5]. Furthermore, periostin is increased during metastasis and may affect the tumor size and number of metastatic lesions. This highlights its important role in shaping and remodeling the cancer tissue microenvironment [

5].

Periostin was reported to be expressed in the stroma of Warthin’s tumors [

6]. In this study, we focused on the expression of periostin in Warthin’s tumors and malignant lymphomas, as it is essential to differentiate between these two types of tumors. While periostin overexpression in breast cancer correlates with metastatic potential[

7], our study uniquely identifies its stromal enrichment in lymphomas compared to Warthin’s tumors, suggesting tissue-specific regulatory mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

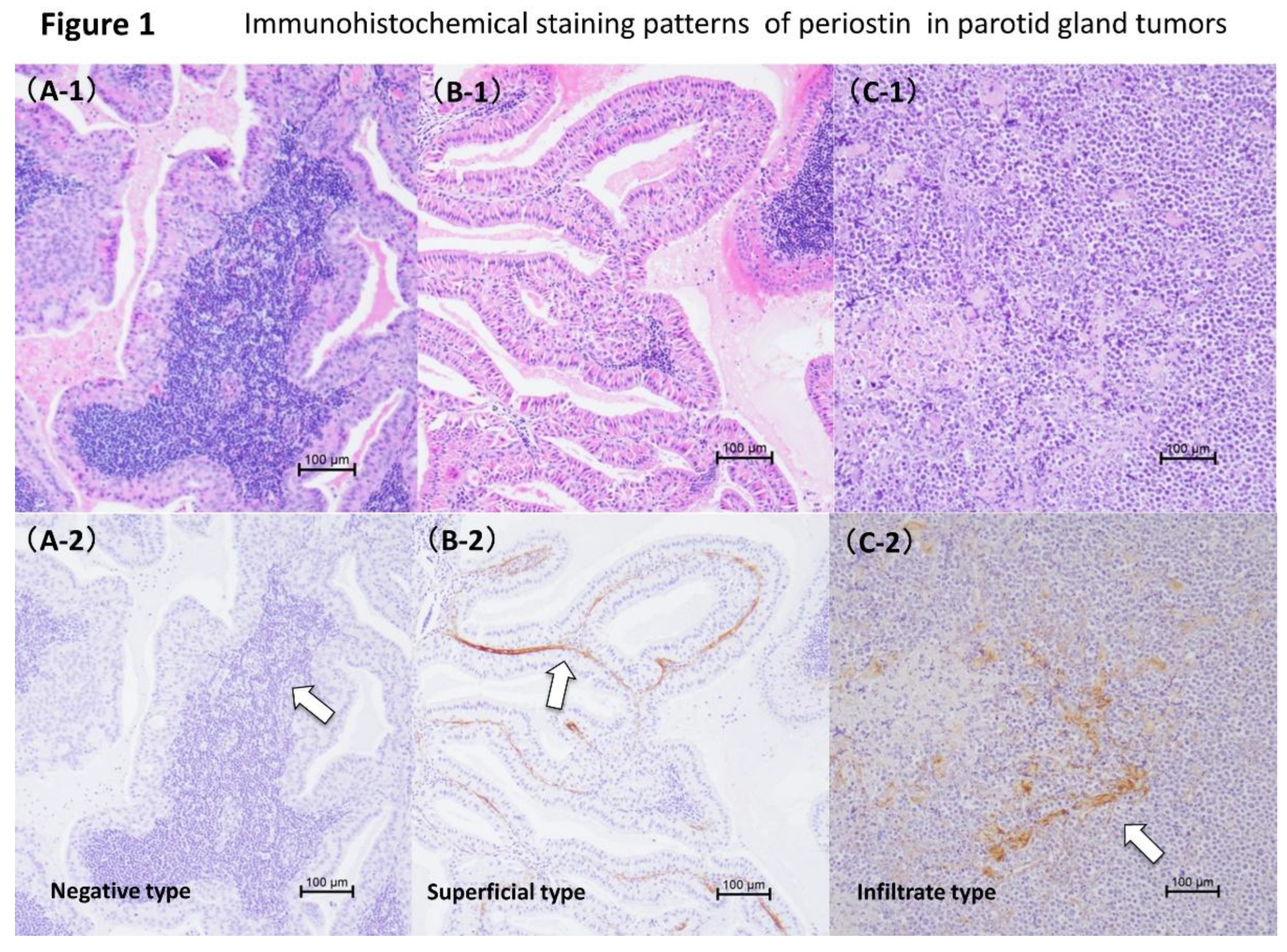

The patients were 26 (mean age 68.4 ± 8.8 [range 51-85] years) with Warthin tumor or malignant lymphoma of the parotid gland. All of these were new cases and there was no sign of infection or recurrence. The patients underwent surgery for parotid gland tumors at the Department of Otolaryngology, Tohoku Medical and Pharmaceutical University Hospital between May 2016 and March 2022. There were two cases of double lesions and 24 cases of single lesions. Only patients with typical clinical and histological findings were included in this study. Tumors were histologically diagnosed as Warthin’s tumors in 15 specimens (13 cases;

Figure 1A1 and 1B1) and malignant lymphomas in 13 specimens (13 cases;

Figure 1C1). The malignant lymphomas included diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in four cases, MALT lymphoma in three cases, and follicular lymphoma in six cases. Normal parotid tissue specimens obtained from patients undergoing partial superficial parotidectomy for pleomorphic adenoma served as controls. The control group ranged in age from 31 to 78 years (mean age 54.1 ± 15.1 years). Histopathological diagnosis of parotid gland tumors was performed by the Division of Pathology, Tohoku Medical and Pharmaceutical University Hospital. This study was approved by the Tohoku Medical University Hospital Ethics Committee (approval number: 2021-2-115). This study adopted an opt-out policy, so obtaining informed consent was not required.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry for Detecting Periostin

Exactly 4-µm sections were cut from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks, deparaffinized, and rehydrated in a graded series of alcohols. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 3% H

2O

2 in absolute methanol at room temperature for 10 minutes. All sections were preincubated in Protein Block Serum-Free (Dako Cat No. X0909) at room temperature for 20 minutes to block nonspecific background staining. The sections were then incubated with a polyclonal anti-periostin antibody, diluted 1:2730, and kept at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with a secondary antibody, the EnVision+ Dual Link System-HRP (Dako Cat No. K4063), for 60 minutes at room temperature. Finally, the sections were incubated with the liquid diaminobenzidine + Substrate Chromogen System (Cat No. K3468, Dako) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Normal gastric tissue was used as a positive control. The validity of the staining was confirmed by the presence of periostin in the interstitium immediately beneath the gastric mucosal epithelium [

6,

8,

9,

10,

11].

2.3. Slide Evaluation

Immunostained sections were assessed under a Keyence microscope with a ×40, or ×100 eyepiece reticle. Cell counts were expressed as means per high-power field, equivalent to an area of 0.202 mm2. To ensure accuracy, more than 2 sections were immunostained. At least 5 areas per section were evaluated with a reticle.

2.4. Statistics

Variables were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test, Fisher’s exact test, or the Chi-square test for independence, as appropriate. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Fisher’s exact test was used because there were cells with expected values less than 5. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used because the variances were not equal.

Statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [

12].

3. Results

3.1. Periostin Expression in Warthin’s Tumor and Malignant Lymphoma

Expression of periostin was investigated in 28 samples of parotid gland tumors from 26 patients (

Table 1). The expression was observed in 24 (85.7%) of these samples obtained from patients with Warthin’s tumors and malignant lymphomas. Specifically, periostin was present in 12 out of 15 samples (80.0%) from patients with Warthin’s tumors, and in 12 out of 13 samples (92.3%) from patients with malignant lymphomas.

Three patterns of periostin expression were observed. The patterns were a negative type (

Figure 1A1 and

Figure 2A2), superficial type (

Figure 1B1 and

Figure 2B2), and infiltrative type (

Figure 1C1 and

Figure 2C2). Superficial type = periostin is detected only in the subepithelial layers between the stromal tissue and the basement membrane (

Figure 1B2). Infiltrative type = periostin was observed in different parts of the tumor stroma (

Figure 1C2). Periostin was not expressed in the tumor parenchyma. Staining intensity graded as 0 (negative) to 3 (strong). Periostin expression was not observed in the control group.

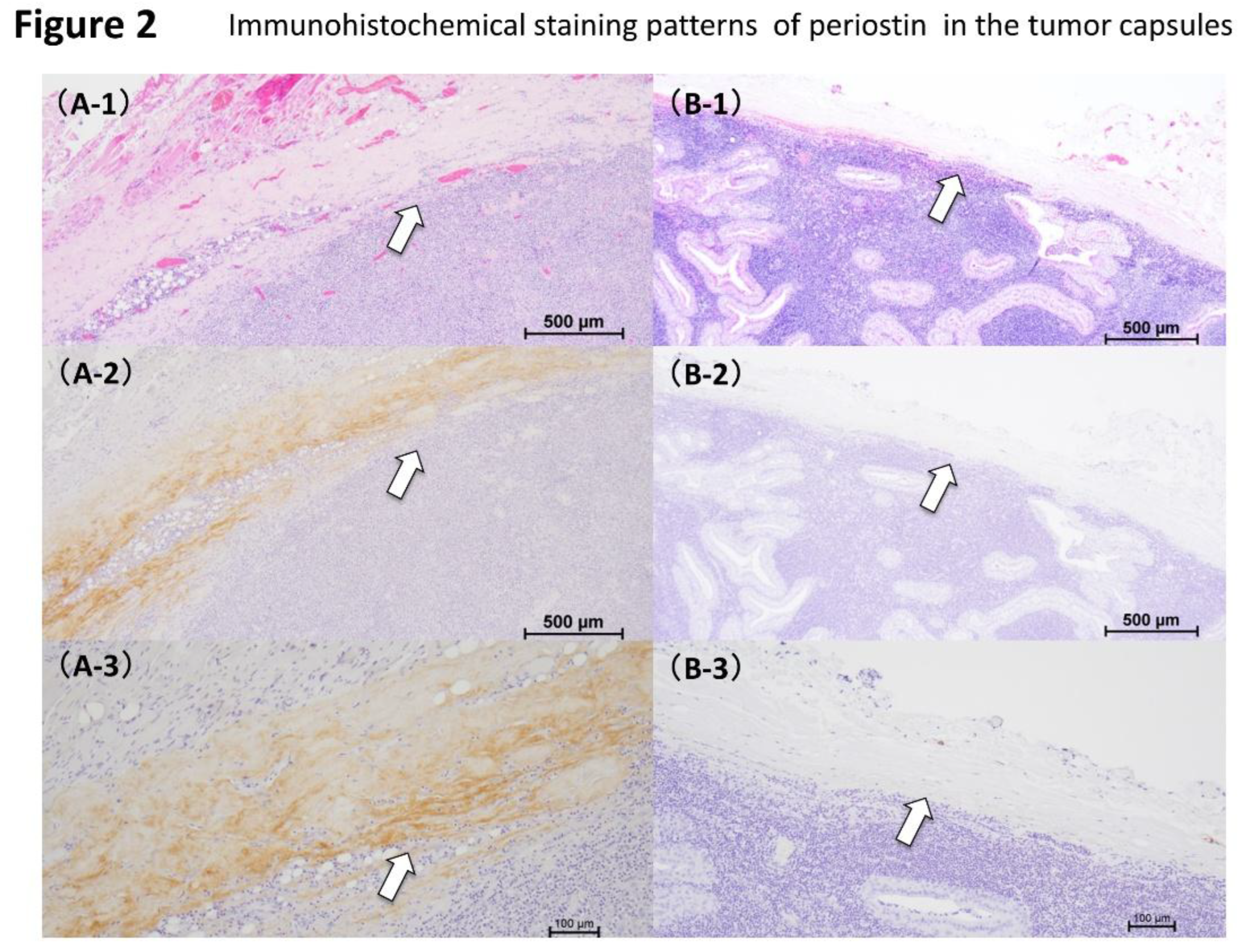

3.2. Periostin Expression in the Capsule of Warthin’s Tumor and Malignant Lymphoma

Periostin expression was examined in the same 28 samples (

Table 2). Thirteen of these (46.4%) had increased periostin expression within the tumor capsule. Tumor capsule periostin was positive in 3 of 15 (20%) Warthin’s tumor and 10 of 13 (76.9%) malignant lymphoma cases. Two distinct periostin expression types were observed in the tumor capsules: positive type (

Figure 2A1–A3) and negative type (

Figure 2B1–B3). A significant association was found between histopathological typing of parotid gland tumors and Periostin expression patterns (

Table 2).

3.3. Periostin Expression Type of Tumors Stroma and Clinical Factors

An association was observed between the periostin expression pattern of parotid gland tumors stroma and the histological types of parotid gland tumors (Warthin’s tumors and malignant lymphomas) (

Table 1). Warthin’s tumors were significantly dominant in the superficial periostin expression type (

Table 1). Conversely, the malignant lymphomas predominantly showed the infiltrate periostin expression type (

Table 1). Furthermore, a notable age difference was found in relation to the patterns of periostin expression in these tumors. Older adults were significantly more likely to exhibit both superficial and infiltrative types of periostin expression (

Table 3). However, no association was found between periostin expression types and other clinical characteristics, such as gender or involvement of the superficial and deep lobes (

Table 3). Similarly, no significant association was found between periostin expression types and tumor size (

Table 4). There were no cases of recurrence or death for Warthin’s tumor. There were two cases of recurrence and one case of death for malignant lymphoma. The cases of recurrence and death were infiltrate type. However, the prognosis for five of the 12 cases of infiltrate type in malignant lymphoma was unknown.

Binomial logistic regression analysis of Warthin’s tumor showed no significant difference when the dependent variable was periostin positivity or negativity and the explanatory variables were age and size. Binomial logistic regression analysis for malignant lymphoma with periostin positivity or negativity as the dependent variable and age and size as the explanatory variables could not be performed because there was only one negative case. In malignant lymphoma, the positive and negative results of periostin and the expression by site cannot be examined because recurrence is often unknown(Binomial logistic regression analysis). The positive and negative results of periostin in Warthin’s tumor and its expression by location cannot be examined because there are no cases of recurrence(Binomial logistic regression analysis). The study of periostin negativity and site-specific expression in malignant lymphoma and death cannot be calculated because there are rows with a total frequency of 0 (Binomial logistic regression analysis). The study of periostin negativity and site-specific expression in Warthin’s tumor and death cannot be calculated because there are rows with a total frequency of 0 (Binomial logistic regression analysis). Binomial logistic regression analysis with periostin as the dependent variable and histological type and age as explanatory variables showed no significant difference. Binomial logistic regression analysis with periostin as the dependent variable and histological type and size as explanatory variables showed no significant difference. Binomial logistic regression analysis using the site of periostin expression in malignant lymphoma as the dependent variable and age and size as explanatory variables is not possible because there is no superficial expression. Binomial logistic regression analysis using the site of periostin expression in Warthin’s tumor as the dependent variable and age and size as explanatory variables showed no significant difference.

4. Discussion

Tateda et al. observed significant differences in periostin expression patterns between benign salivary gland tumors and their histology, particularly in the tumor capsules. It was observed that significant differences exist between the histology of benign salivary gland tumors and the presence of periostin expression in their capsules. Periostin was highly expressed in the stroma of pleomorphic adenomas, and was also highly expressed in the capsule of pleomorphic adenomas. Increased expression and localization of periostin in pleomorphic adenomas may be related to recurrence, a biological characteristic of pleomorphic adenomas [

6]. Our study investigated the relationship between Warthin’s tumor and malignant lymphoma and revealed differential periostin expression in these tumors.

Periostin was originally cloned as osf-2 by Takeshita et al., which is a gene specifically expressed in osteoblasts and is similar to midline fasciclin-1, an intercellular adhesion factor in Drosophila melanogaster. Periostin was specifically expressed in the periosteum and periodontal ligament. This gene was renamed “periostin” because it is specifically expressed in the epiphyseal line and periodontal ligament and is involved in cell adhesion [

13,

14]. Recent studies have implicated periostin not only in epiphyseal and periodontal ligaments, but also in various pathological conditions, such as embryonic development, cancer, myocardial infarction, muscular dystrophy, and myelofibrosis.It has also been reported that periostin is expressed in healing- and regeneration-related processes, such as wound healing and skeletal muscle regeneration. Studies of tumors and periostin have reported overexpression of periostin in non-small cell lung cancers and thymomas [

15,

16]. Subsequently, periostin expression was also reported in other types of cancer, including bladder cancer, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, thyroid cancer and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. It became clear that periostin expression is closely related to cancer malignancy, progression, invasion, metastasis, and prognosis [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

The current study focused on two types of parotid tumors: Warthin’s tumor and malignant lymphomas. In these two histological types, various levels and patterns of periostin expression were observed in the stroma of the tumors. Tateda et al. found that periostin was overexpressed in vocal cord polyps and benign parotid gland tumors [

6,

24]. These vocal cord polyps and benign parotid tumors expressed periostin in the stroma, and the expression patterns were classified into four types: negative, superficial, infiltrative, and diffuse [

6,

24].

The expression patterns of periostin in two histological types of parotid tumors were examined: Warthin’s tumor and malignant lymphomas. None of the parotid tumors studied showed periostin expression in the epithelial cells. Periostin expression in Warthin’s tumor was classified as negative type in 3 cases, superficial type in 10 cases, and invasive type in 2 cases.

In the superficial type, the most common periostin phenotype in Warthin’s tumor, periostin was detected only in the subepithelial layer between the basal cells and stromal tissue. The superficial pattern was consistently observed in all 10 cases of Warthin’s tumors, marking it a characteristic finding. These tumors generally have low rates of recurrence and malignant transformation. In contrast, in cases of malignant lymphomas, periostin expression patterns were as follows: negative in 1 case and infiltrative in 12 cases. Periostin expression has been reported in the fibrous stroma of invasive carcinomas and the fibrous capsule of tumors [

25], as well as in the capsule of pleomorphic adenomas, a benign parotid tumor [

6].

Twelve of 13 cases of malignant lymphoma expressed periostin, all of which were infiltrative type. In contrast, in Warthin’s tumor, which has a low recurrence rate, periostin expression was negative type in 3 of 15 cases and superficial type in 10 of 15 cases. We also examined the capsules of parotid tumors. Pathological examination revealed that both Warthin’s tumor and malignant lymphoma had capsules. Periostin expression was positive in 12 of 13 malignant lymphoma capsules. Significant differences were observed between the histological types of parotid tumors (Warthin’s tumor and malignant lymphomas) and the expression patterns of periostin. When the tumor capsule was examined, a significant difference was observed between the histological type of parotid tumor and the presence or absence of periostin expression in the tumor capsule. These results suggest a possible association between malignant lymphoma, and increased expression and localization of periostin, which may be indicative of infiltration, tumor growth, recurrence, metastasis, and other characteristics of malignant tumors. Age was the only statistically significant difference. (

Table 3). We believe that this discrepancy is simply due to the difference in the number of cases of Warthin’s tumor and malignant lymphoma included in our study. It was suggested that periostin expression was higher in the tumor stroma of malignant lymphoma than in Warthin’s tumor. Periostin expression was also observed in the tumor capsule of malignant lymphoma, suggesting that periostin may be involved in the microenvironment of malignant lymphoma metastasis and growth. Traditionally, parotid gland tumors have been diagnosed based on symptoms, CT scans, MRI scans, and fine needle aspiration cytology. If diagnosis becomes possible using a simple diagnostic kit that measures biomarkers, including periostin in saliva, similar to influenza diagnostic kits, it could become a safer, cheaper, less invasive, and superior liquid biopsy test. The expression of periostin may be lower in the benign Warthin’s tumor than in malignant lymphoma. These findings suggest that the expression pattern and its enhancement may be closely related to the malignancy, progression, invasion, and metastasis of malignant lymphoma. If the factors involved are clarified, they can be used as biomarkers to assess malignancy and predict malignant change, invasion, and metastasis, which will be extremely useful in disease management and enable the development of treatments targeting these molecules. The diagnostic threshold, sensitivity, specificity, and how periostin staining can be introduced into the clinical workflow remain topics for future investigation. Data supporting its diagnostic performance and feasibility must be accumulated. To determine whether periostin can be used clinically as a marker, the relationship between periostin expression patterns and blood and salivary periostin concentrations must be investigated. In this study, we treated malignant lymphomas as a single group without histological subdivision and suggested a significant correlation between periostin expression patterns and tumor histology, with the superficial pattern being more common in Warthin’s tumor and the invasive pattern being predominant in malignant lymphoma. Naturally, since each subtype of malignant lymphoma exhibits different stromal structures and biological behaviors, their diversity is well known, and it would be desirable to investigate subtype-specific expression patterns. Warthin’s tumor is composed of eosinophilic epithelial cells and lymphoid stroma. Lymphoid stroma with follicle formation is observed. Fibrous changes and an increase in fibroblasts may be observed in the stromal tissue at sites where malignant lymphoma cells have infiltrated. This suggests that when malignant lymphoma spreads into the stromal tissue, the surrounding tissue reacts by causing fibrosis. In this study, periostin was observed in the interstitial fibrotic areas. In Warthin’s tumor, periostin expression tended to be limited to fibrosis just below the basement membrane. In malignant lymphoma, periostin expression was observed in some fibrotic areas of the stroma. These findings suggest that periostin may be involved in the invasion and metastasis of malignant lymphoma through the tumor microenvironment, immune regulation, or stromal remodeling.

There were no cases of recurrence or death for Warthin’s tumor. There were two cases of recurrence and one case of death for malignant lymphoma. The cases of recurrence and death were infiltrate type. However, the prognosis for five of the 12 cases of infiltrate type in malignant lymphoma was unknown. Regarding periostin and recurrence, there is much information unknown in malignant lymphoma, so testing is not possible (Fisher’s exact test). In Warthin’s tumor, there were no positive or negative patients, so testing is not possible(Fisher’s exact test). Regarding periostin and death, Fisher’s exact test showed P = 1 for malignant lymphoma (Fisher’s exact test). For Warthin’s tumor, no test was possible as there were no positive or negative cases. To examine the association between periostin expression patterns and patient outcomes, further validation is needed in larger cohort studies.

5. Conclusions

While periostin expression correlates with tumor aggressiveness (p < 0.001), its diagnostic utility requires validation against gold-standard markers (e.g., CD20 for lymphoma).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T. and Takahiro.Suzuki.; methodology, Y.T.; validation, Y.T., Takahiro.Suzuki., Teruyuki. Sato., Kenji. Izuhara., Kazue. Ise., H.S., Keigo. Murakami., Kazuhiro. Murakami., Y.N., and N.O.; formal analysis, Y.T. and Teruyuki. Sato.; investigation, Y.T.; data curation, Y.T. and Teruyuki. Sato.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.T.; writing—review and editing, Y.T.; visualization, Y.T.; supervision, N.O.; project administration, Y.T.; funding acquisition, N.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the ethics review committee of Tohoku Medical University Hospital (approval no. 2021-2-115(2023)).

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for obtaining informed consent was waived because of the adoption of an opt-out policy in the study.:.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Mr. Junya Ono for his assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Veder, L.L.; Kerrebijn, J.D.; Smedts, F.M.; den Bakker, M.A. Diagnostic accuracy of fine-needle aspiration cytology in Warthin tumors. Head Neck. 2010, 32, 1635–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.; MacKenzie, K.; McGarry, G.W.; Mowat, A. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland : A review of 341 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000, 22, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parwani, A.V.; Ali, S.Z. Diagnostic accuracy and pitfalls in fine-needle aspiration interpretation of Warthin tumor. Cancer Cytopathol. 2003, 99, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoersch, S.; Andrade-Navarro, M.A. Periostin shows increased evolutionary plasticity in its alternatevely spliced region. BMC Evol Biol. 2010, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez, L.; Alonso, J. Periostin: a matricellular protein with multiple functions in cancer development and progression. Front Oncol. 2018, 8, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tateda, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Sato, T.; Izuhara, K.; Ise, K.; Shimada, H.; Murakami, K.; Murakami, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Ohta, N. Expression of Periostin in Benign salivary gland tumors. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2024, 262, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, Y.; Taniyama, Y.; Sanada, F.; Morishita, R.; Nakamori, S.; Morimoto, K.; Yeung, K.T.; Yang, J. Periostin blockade overcomes chemoresistance via restricting the expansion of mesenchymal tumor subpopulations in breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateda, Y.; Ikeda, R.; Kakuta, R.; Ono, J.; Izuhara, K.; Ogawa, T.; Ise, K.; Shimada, H.; Murakami, K.; Murakami, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Katori, Y.; Ohta, N. Expression of Periostin in Vocal Fold Polyps. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2022, 258, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateda, Y.; Ikeda, R.; Kakuta, R.; Izuhara, K.; Ogawa, T.; Ise, K.; Shimada, H.; Murakami, K.; Murakami, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Katori, Y.; Ohta, N. Immunohistochemical Localization of D-β-Aspartic Acid and Periostin in Vocal Fold Polyps. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2023, 260, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateda, Y.; Sato, T.; Ikeda, R.; Kakuta, R.; Izuhara, K.; Ogawa, T.; Ise, K.; Shimada, H.; Murakami, K.; Murakami, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Katori, Y.; Ohta, N. Immunohistochemical localization of CD31, CD34, and periostin in vocal fold polyps. Acta Otolaryngol. 2023, 143, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateda, Y.; Ikeda, R.; Kakuta, R.; Izuhara, K.; Ogawa, T.; Ise, K.; Shimada, H.; Murakami, K.; Murakami, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Katori, Y.; Ohta, N. Expression of Vascular and Tissue Repair Factors in Laryngeal Granulomas. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2024, 264, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely-available easy-to-use software “EZR” (Easy R) for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshita, S.; Kikuno, R.; Tezuka, K.; Amann, E. Osteoblast-specific factor 2: cloning of a putative bone adhesion protein with homology with the insect protein fasciclin I. Biochem J. 1993, 294, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiuchi, K.; Amizuka, N.; Takeshita, S.; Takamatsu, H.; Katsuura, M.; Ozawa, H.; Toyama, Y.; Bonewald, L.F.; Kudo, A. Identification and characterization of a novel protein, periostin, with restricted expression to periosteum and periodontal ligament and increased expression by transforming growth factor beta. J Bone Miner Res. 1999, 14, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, H.; Dai, M.; Auclair, D.; Fukai, I.; Kiriyama, M.; Yamakawa, Y.; Fujii. Y.; Chen, L.B. Serum level of the periostin, a homologue of an insect cell adhesion molecule, as a prognostic marker in nonsmall cell lung carcinomas. Cancer. 2001, 92, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, H.; Dai, M.; Auclair, D.; Kaji, M.; Fukai, I.; Kiriyama, M.; Yamakawa, Y.; Fujii, Y.; Chen, L.B. Serum level of the periostin, a homologue of an insect cell adhesion molecule, in thymoma patients. Cancer Lett. 2001, 172, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Ouyang, G.; Bai, X.; Huang, Z.; Ma, C.; Liu, M.; Shao, R.; Anderson, R.M.; Rich, J.N.; Wang, X.F. Periostin potently promotes metastatic growth of colon cancer by augmenting cell survival via the Akt/PKB pathway. Cancer Cell. 2004, 5, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, Y.; Ogawa, I.; Kitajima, S.; Kitagawa, M.; Kawai, H.; Gaffney, P.M.; Miyauchi. M.; Takata, T. Periostin promotes invasion and anchorage-independent growth in the metastatic process of head and neck cancer. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 6928–6935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, N.; Kikuchi, Y.; Nishiyama, T.; Kudo, A.; Fukayama, M. Periostin deposition in the stroma of invasive and intraductal neoplasms of the pancreas. Mod Pathol. 2008, 21, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppin, C.; Fabbro, D.; Dima, M.; Loreto, C.D.; Puxeddu, E.; Filetti, S.; Russo, D.; Damante, D.G. High periostin expression correlates with aggressiveness in papillary thyroid carcinomas. J Endocrinol. 2008, 197, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim. C.J.; Sakamoto. K.; Tambe, Y.; Inoue, H. Opposite regulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and cell invasiveness by periostin between prostate and bladder cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2011, 38, 1759–1766. [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak-Wielgomas, K.; Grzegrzolka, J.; Piotrowska, A.; Matkowski, A.; Wojnar, A.; Rys, J.; Ugorski, M.; Dziegiel, P. Expression of periostin in breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2017, 51, 1300–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Li, W.; Chen, R.; Wang, J.; Lu, X.; Jun, Li. Stromal POSTN induced by TGF-β1 facilitates the migration and invasion of ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 2021, 160, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateda, Y.; Ikeda, R.; Kakuta, R.; Ono, J.; Izuhara, K.; Ogawa, T.; Ise, K.; Shimada, H.; Murakami, K.; Murakami, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Katori, Y.; Ohta, N. Expression of periostin in vocal fold polyps. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2022, 258, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazaki, M.; Kudo, A. Impaired capsule formation of tumors in periostin-null mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008, 367, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).