1. Introduction

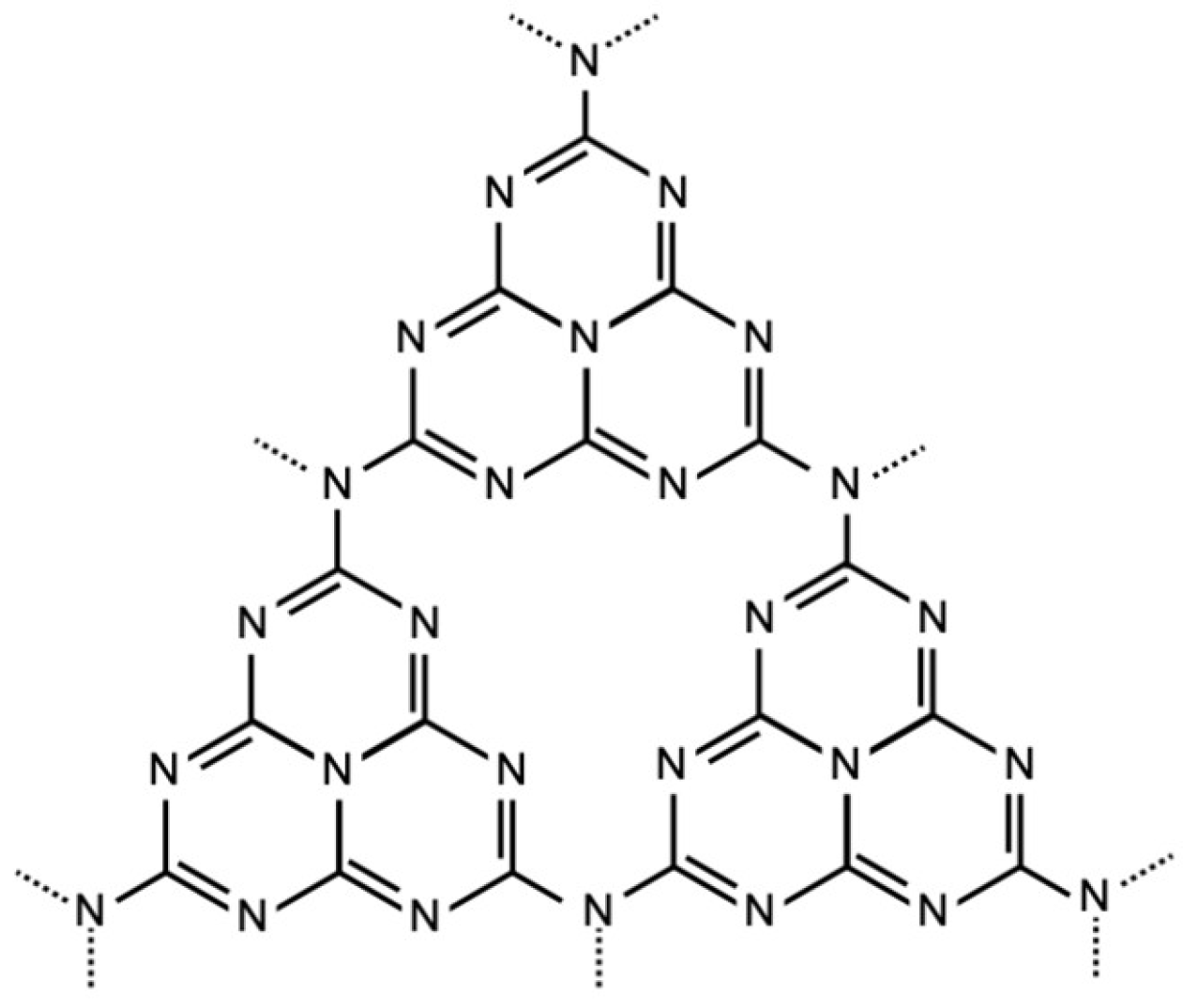

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C

3N

4,

Figure 1) is a carbon nitride polymorph with a graphite-like layered crystal structure that consists of heptazine ring (C

6H

7) units linked with N atoms. g-C

3N

4 behaves as a photocatalyst under visible light illumination. Its band gap of approximately 2.7 eV corresponds to visible light wavelengths, which allows g-C

3N

4 to utilize solar light efficiently. g-C

3N

4 can catalyze various photoinduced reactions, including hydrogen formation from water, pollutant degradation, and conversion of organic molecules [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Additionally, g-C

3N

4 is a metal-free photocatalyst comprising ubiquitous elements (C and N). It can be prepared from various commercially available nitrogen-containing organic materials, including melamine, urea, cyanamide, and dicyandiamide, through thermal condensation in air. Hence, the use of the g-C

3N

4 photocatalyst is potentially beneficial to various industrial and environmental processes.

A well-known shortcoming of g-C3N4 photocatalysts is their low photocatalytic reaction efficiency owing to their high electron–hole recombination rates and small specific surface areas. g-C3N4 photocatalytic reactions are induced by visible light illumination, generating a charge-separation state via electronic excitation. The excited electrons and holes trigger reduction and oxidation, respectively. However, if electrons and holes recombine rapidly through radiative and non-radiative relaxation, the reaction efficiency is reduced. In addition, the specific surface area of g-C3N4 is generally small. Therefore, the space on the g-C3N4 surface that contributes to the photocatalytic reaction is limited. Consequently, improving the photocatalytic reaction efficiency is important for expanding the range of g-C3N4.

Electron beam (EB) irradiation is a potential method for improving the reaction efficiency of g-C

3N

4. However, studies of the effects of EB irradiation on g-C

3N

4 are limited. Zhang et al. studied the effect of EB irradiation on the photocatalytic efficiency of g-C

3N

4 [

19]. They found that EB irradiation improved the photocatalytic efficiency of rhodamine B degradation in aqueous solutions. The loss of pyridinic N and increased tertiary N content were also observed, suggesting that the structural alteration of the tri-

s-triazine structure of g-C

3N

4 through EB irradiation resulted in altered photocatalytic efficiency. Picho-Chillán et al. studied the photocatalytic degradation of Direct Blue 1 using g-C

3N

4 irradiated with a low-dose EB [

20], finding that EB irradiation increased the adsorption capacity of the dye. Moreover, the photocatalytic dye decomposition efficiency of the EB-irradiated g-C

3N

4 in the presence of H

2O

2 was higher than that of intact g-C

3N

4. Mendes et al. investigated the structural changes in g-C

3N

4 during EB exposure using transmission electron microscopy [

21] and found that N species were removed by the EB. Mohapatra et al. studied the effect of EB on the photocatalytic performance of g-C

3N

4 for H

2 generation and Cr

6+ reduction [

22]. They reported that N vacancies were generated through EB irradiation, which led to an improvement in photocatalytic efficiency. We also studied the effect of EB irradiation on the structure and reactivity of g-C

3N

4. We found that relatively low-dose EB irradiation improved the photocatalytic efficiency, whereas the efficiency degraded when a higher dose of EB was used [

23]. These results indicate that EB-induced formation of defects through N elimination improves g-C

3N

4 photocatalytic efficiency. The enhancement of photocatalytic performance through N defect formation has also been reported using methods other than EB irradiation [

5,

6,

7,

17,

18,

24,

25,

26].

Another strategy for improving photocatalytic efficiency involves exfoliation to create C

3N

4 nanosheets. This exfoliation technique has been applied in numerous studies of g-C

3N

4 photocatalysts. For example, nanosheet fabrication was carried out in some of the above-mentioned studies [

6,

9,

10,

15,

18] using various methods, such as thermal treatment in air. Liu et al. developed a novel exfoliation method that employed N

2-assisted treatment [

27] and cogrinding with sugar [

28,

29]. As a simpler method, sonication of g-C

3N

4 in an organic liquid can be applied to achieve exfoliation. For example, Yang et al. examined the sonication of g-C

3N

4 in various solvents and found that isopropanol and

N-methyl-pyrrolidone were promising solvents for preparing stable g-C

3N

4 nanosheet dispersions [

30]. She et al. reported the preparation of a stable g-C

3N

4 nanosheet dispersion by sonication using 1,3-butanediol as the solvent [

31]. These exfoliation treatments significantly increased the specific surface area of g-C

3N

4, thereby enhancing its photocatalytic performance. Consequently, a synergistic improvement in the photocatalytic performance is expected from the combination of sonication and EB irradiation. However, studies of these combined effects are scarce.

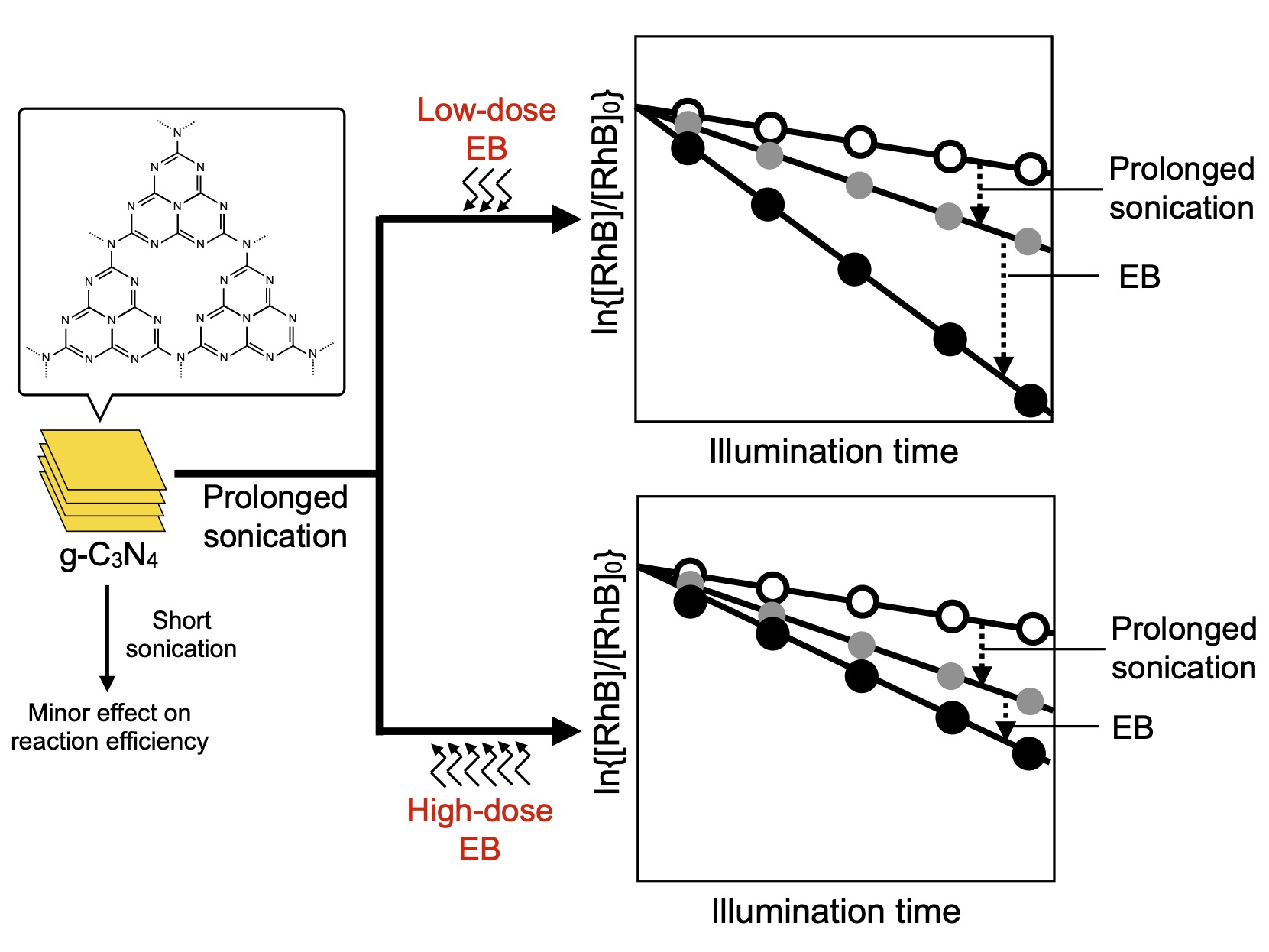

Herein, the combined treatment of sonication and EB irradiation was examined for the first time to develop a novel technique for improving the efficiency of a photocatalytic reaction (decomposition of aqueous rhodamine B). In this study, g-C3N4 prepared from melamine was sonicated for various durations and irradiated with low- or high-dose EB. The textural and chemical characteristics of the samples were investigated to elucidate the effects of the combined irradiation/sonication.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of g-C3N4

The g-C3N4 was prepared using melamine (FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals, Japan). Melamine was placed in an alumina crucible and covered with an alumina lid. Subsequently, the crucible was heated in air in a muffle furnace at a heating rate of 5 ℃/min and maintained at 550 ℃ for 2 h. A pale yellow product was obtained. The product was ball-milled for 24 h and sifted through stainless-steel sieves. g-C3N4 powder with a particle diameter between 1 mm and 180 µm was collected.

2.2. Sonication and Electron Beam Irradiation

The prepared g-C

3N

4 (1.0 g) was added to 25 mL of 1,3-butanediol (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Japan) and sonicated for 60–480 min using an ultrasonic homogenizer (LUH150, Yamato Scientific, Japan) [

31]. The ultrasonic frequency was set at 20 kHz. The solvent was then vaporized at 140 ℃ using a thermostatic drying oven. This procedure was repeated until a sufficient amount of g-C

3N

4 was collected for EB irradiation.

For the EB irradiation, each sample (approximately 5 g) was placed in a polyamide-polyethylene bag (10 × 15 cm) before or after sonication and sealed with a household vacuum sealer. The sample was packed to form a sufficiently thin (1–2 mm thick) particle layer for EB transmission. EB irradiation was conducted at the NHV Corporation Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan. The EB dose used for irradiation was 200 or 600 kGy. Irradiation was conducted at ambient temperature. Hereafter, the samples are named based on the sonication time (“S”) and EB dose (“E”). For example, the sample sonicated for 60 min and irradiated with 200 kGy EB is denoted as “S60E200.”

2.3. Characterization

The crystal structures of the samples were elucidated using X-ray diffractometry (XRD, D8 Discover, Bruker, USA) with Cu K

α X-ray. The elemental analysis and classification of chemical bonds were performed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (JPS-9200, JEOL, Japan) with Mg K

α X-ray. Indium foil was used to mount the samples for XPS experiments. Peak deconvolution of the high-resolution C 1s and N 1s was performed using CasaXPS software [

32]. The specific surface areas of the samples were determined using N

2 adsorption/desorption measurements (Autosorb, Quantachrome Instruments, USA). The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) adsorption isotherm was used to calculate the specific surface areas [

33].

2.4. Photocatalytic Decomposition of Organic Dye

The photocatalytic degradation of RhB was monitored by colorimetric RhB concentration measurements. Portions of a 10 mg/L aqueous RhB solution (50 mL) were taken, and 0.1 g g-C3N4 was added to each solution. The mixture was then illuminated with visible light from an Xe light source (MAX-303, Asahi Spectra, Japan). Visible light illumination was performed using a quartz rod immersed in the sample mixture. The wavelength of the light was 400-600 nm. Air bubbling was continued throughout the photocatalytic reaction. The g-C3N4-containing solution was sampled every 10 min; g-C3N4 was removed from the sample by centrifugation, and the supernatant RhB concentration was determined by colorimetric quantitative analysis (V-630, JASCO, Japan).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of g-C3N4

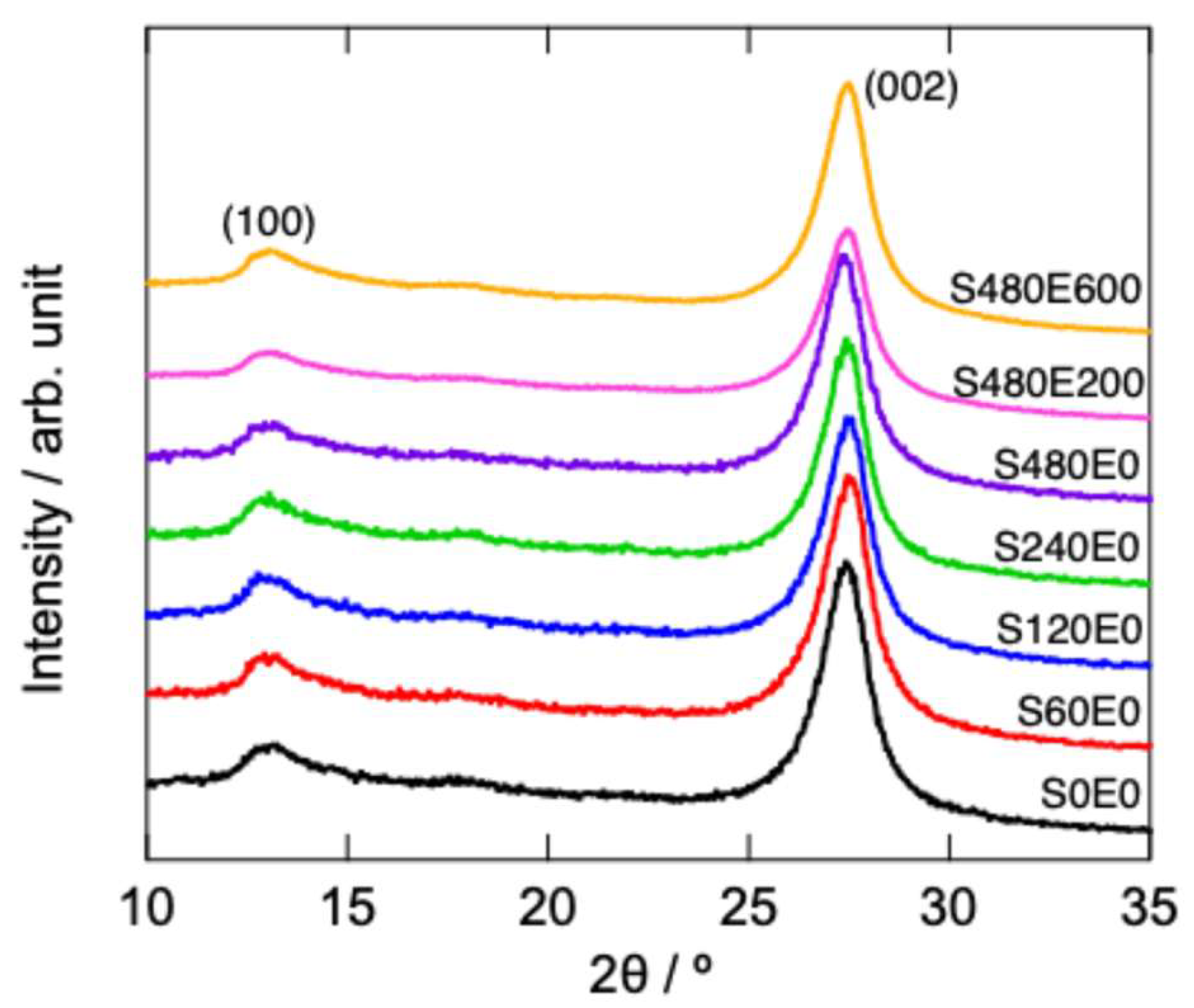

Figure 2 shows the powder XRD patterns of intact and sonicated samples before EB irradiation (S0E0–S480E0). The XRD patterns of S480E200 and S480E600 are also shown. Two major peaks assigned to the (100) and (002) reflections, corresponding to the in-plane packing and interlayer stacking, respectively, were observed at approximately 13° and 27°. Comparison of these diffraction patterns shows that sonication and subsequent EB irradiation slightly affected the entire g-C

3N

4 crystal structure. Although a slight shift in the (002) peak was observed, the main features of the diffraction pattern did not change after sonication and EB irradiation. These results also indicate that sonication under the present treatment conditions did not cause intensive interlayer expansion to create nanosheets with a few layers and probably leads to mild exfoliation. If exfoliation proceeded intensively through sonication, the (002) peak should have shifted significantly as the interlayer distance increased.

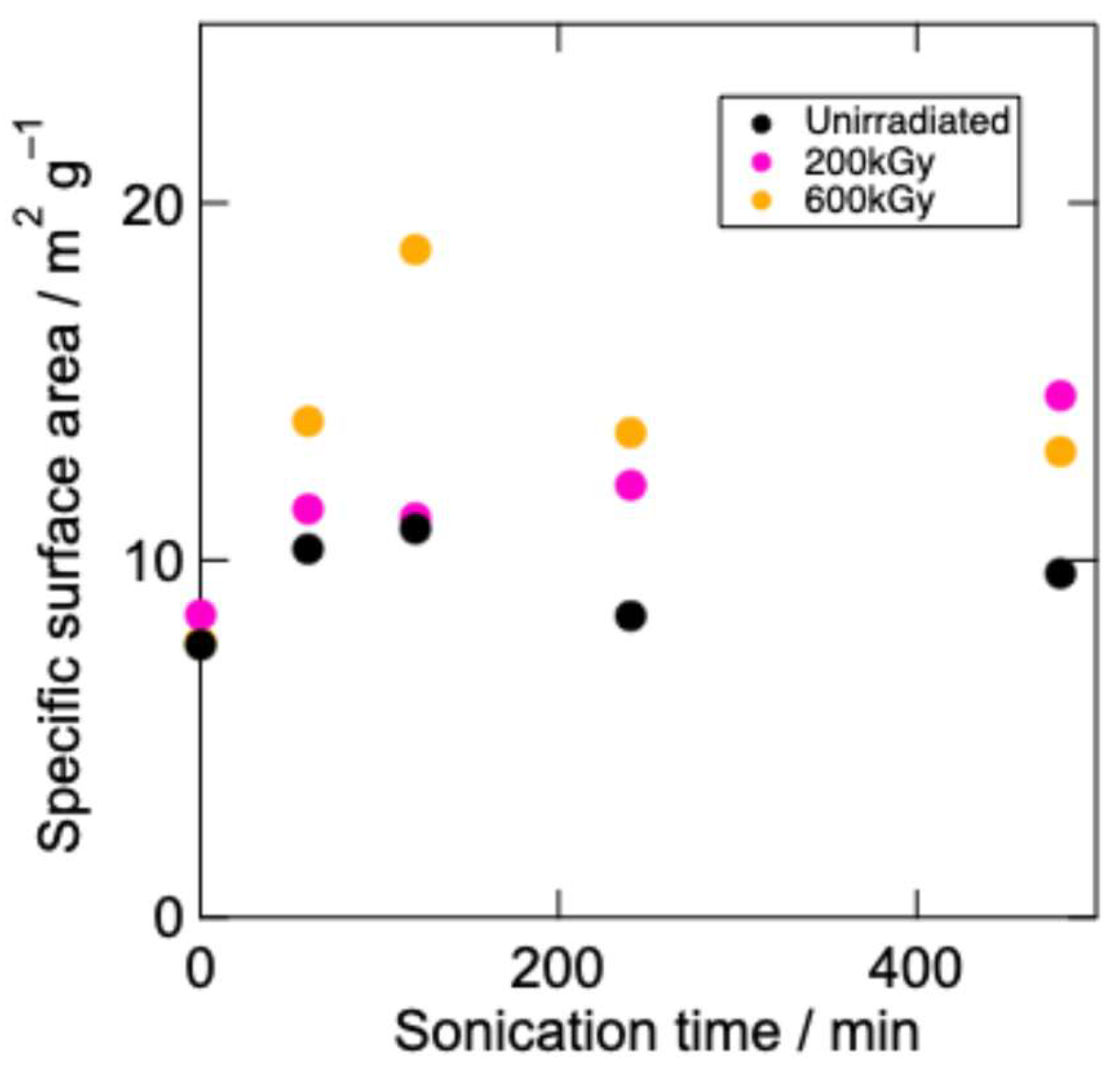

The specific surface areas of the samples as functions of sonication time are shown in

Figure 3. The specific surface areas tended to be small, even after sonication (approximately 10-20 m

2 g

–1). The specific surface areas of the EB-irradiated g-C

3N

4 were larger than those of the unirradiated g-C

3N

4 in all cases. In addition, the EB dose affected the specific surface area. Prolonged sonication increased the specific surface areas of the EB(200 kGy)-irradiated samples (S0E200–S480E200). In contrast, the specific surface areas of the EB(600 kGy)-irradiated samples (S0600–S480E600) exhibited marked fluctuations depending on the sonication time. A similar tendency was observed in our previous work [

23]; the moderate structural change that occurred through low-dose EB irradiation contributed to an increase in the surface area, whereas excess EB irradiation led to more destructive structural changes and a resultant decrease in the specific surface area.

The fluctuation in the specific surface area in the case of EB irradiation at 600 kGy can be understood based on the coarsening of the relatively small particles caused by EB-induced electrification. Small g-C

3N

4 fragments formed through prolonged sonication aggregated significantly by EB-induced electrification compared to moderately sonicated g-C

3N

4. The EB-induced electrification of materials has been previously reported [

34,

35]. Oxidation by EB causing electron detachment from metal cations has also been reported for Co

3O

4 (the transformation of Co

2+ to Co

3+) [

36]. Ionization is a typical initial process that occurs via radiation; thus, electron detachment from g-C

3N

4 is possible through EB irradiation. If g-C

3N

4 is electrified by EB-induced charging, the g-C

3N

4 particles could aggregate via electrostatic interactions, causing coarsening. However, the understanding of the impact of ionizing radiation on the physicochemical properties of g-C

3N

4 remains insufficient, and further investigation of the irradiation effect is necessary.

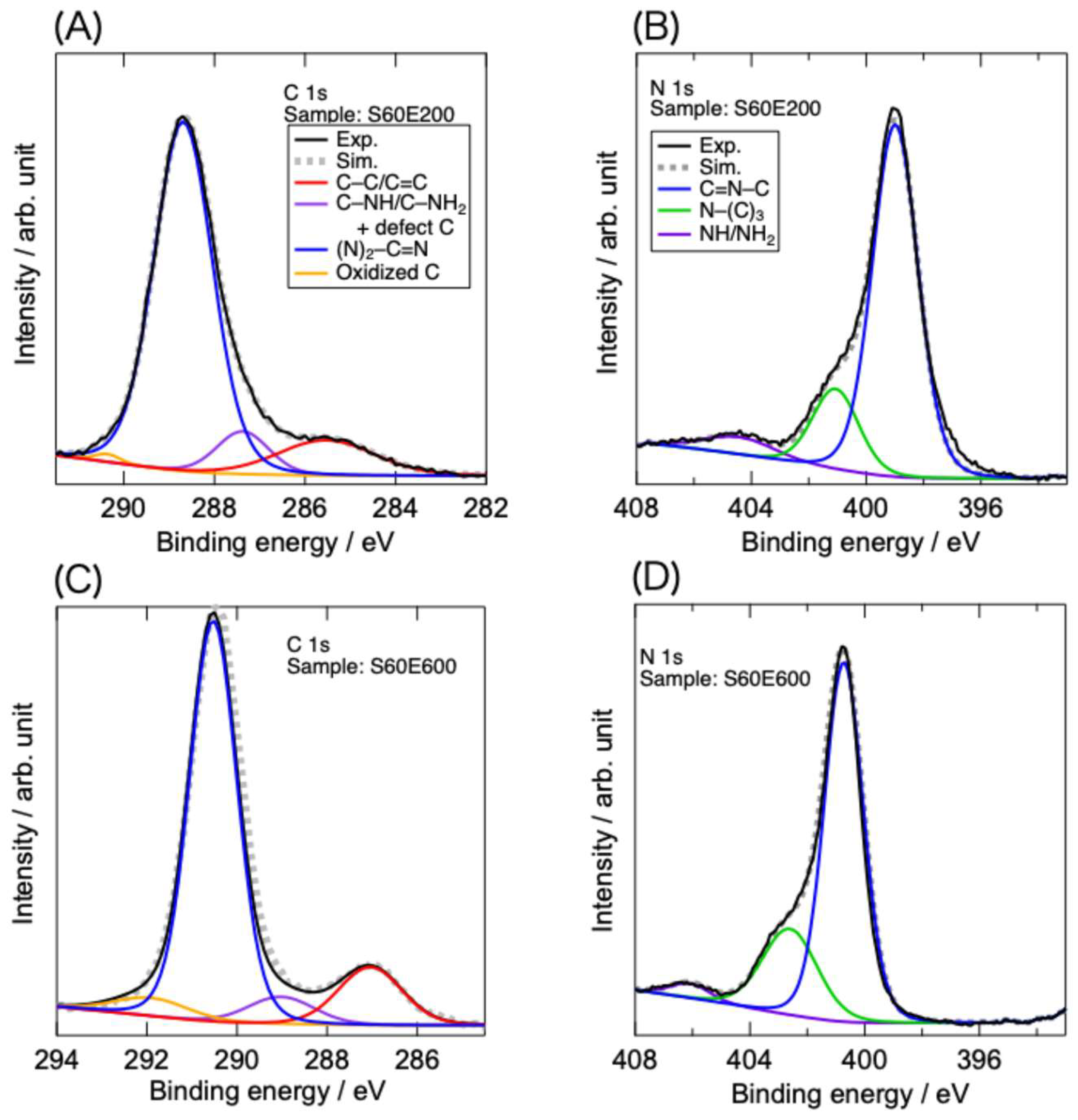

Figure 4 shows typical C 1s and N 1s high-resolution XPS spectra of the EB-irradiated samples after sonication for 60 min. The C 1s spectra reveal that four types of C exist in the samples [

23,

37]: unexpectedly formed C–C + C=C; C–N possessing hydrogen-containing amino groups; (N)

2–C=N contained in triazine rings; and other species, including oxidized C (the XPS survey also detected a small amount of O). Although the peaks corresponding to defect moieties generated through EB-induced N elimination are not specifically identified, the species exhibiting C–NH/C–NH

2 peaks (denoted as “C–NH/C–NH

2 + defect C” in

Figure 5(A, C)) may include also defect carbons. The N 1s spectra also exhibited features similar to those of intact and EB-irradiated g-C

3N

4 without sonication. They consist of three types of N atoms: pyridinic C–N=C, N–(C)

3 connecting three carbon atoms, and hydrogen-containing amino groups. Although charge-up-induced peak shifts were observed, the typical features of the C 1s and N 1s spectra were consistent with previously reported results.

EB irradiation altered the composition of C and N in the samples, as previously reported [

23], whereas sonication did not cause obvious changes. Similarly, the abundance ratios of C and N with different chemical bonding states were altered by EB irradiation but were not significantly affected by sonication. Previous results have revealed that pyridinic N is the predominant species eliminated upon EB irradiation, and that N vacancies and C defects form through N elimination [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. This structural alteration could be related to the improvement in the photocatalytic efficiency. In the present study, the change in the chemical structure of g-C

3N

4 was mainly caused by EB irradiation, and the impact of sonication on the chemical structure was minor.

3.2. Photocatalytic RhB Decomposition Using Treated g-C3N4

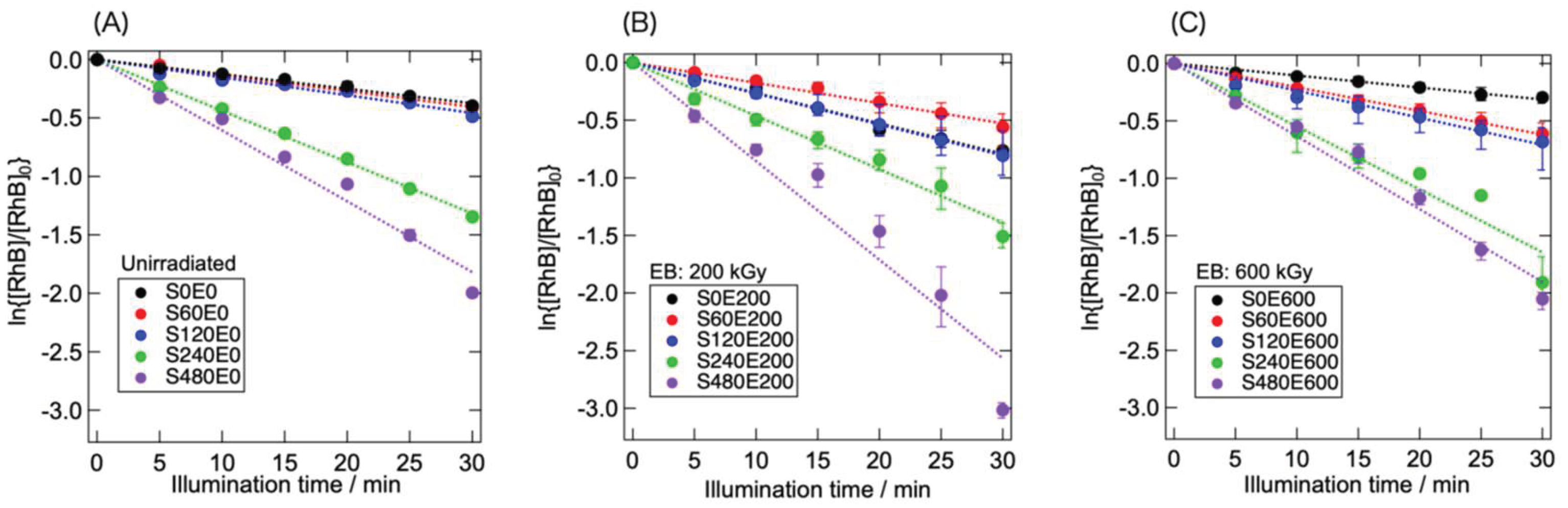

Figure 5 shows the RhB concentration as a function of the illumination time under visible light. The effects of sonication and EB irradiation on the rate of photocatalytic RhB decomposition can be observed. A comparison of the RhB decomposition rates of S0E0, S0E200, and S0E600 revealed that S0E200 exhibited the highest reaction rate. This difference in the reaction rate has already been reported in an earlier study [

23], where moderate structural modification with low-dose EB irradiation improved the photocatalytic reaction efficiency. The preceding sonication altered the reaction rate depending on sonication time. Sonication for up to 120 min had a relatively minor effect on the photocatalytic efficiency, but prolonged sonication markedly accelerated the photocatalytic RhB decomposition.

Comparing S480E0, S480E200, and S480E600, the influence of EB irradiation on the reaction efficiency was obvious. S480E200 exhibited the highest reaction efficiency, indicating that low-dose EB irradiation effectively improves the photocatalytic reaction efficiency of sonicated g-C

3N

4. In contrast, the reaction efficiency of S480E600 was similar to that of S480E0 despite its larger specific surface area (

Figure 3). Notably, although S120E600 had the highest specific surface area among the samples examined, it exhibited a relatively low reaction efficiency. This suggests that the combined effect of EB-induced structural changes and surface area alteration through sonication dominated the reaction efficiency. The structural and textural changes induced by low-dose EB irradiation had a positive effect. However, the positive effect of EB irradiation at a higher dose (600 kGy) was limited; under these conditions, electrostatic particle coarsening and EB-induced destructive structural alteration influenced the reaction efficiency as much as did the change in textural properties (increase in the specific surface area).

4. Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the combined effects of EB irradiation and sonication on the photocatalytic efficiency of g-C3N4. Prolonged sonication before EB irradiation improved the g-C3N4 reaction efficiency. The effect of the subsequent EB irradiation on the photocatalytic efficiency depended on the EB dose and is summarized as follows:

Low-dose EB irradiation further improved the reaction efficiency of sonicated g-C3N4, as it does that of g-C3N4 that is not sonicated.

Higher-dose EB irradiation did not markedly increase the reaction efficiency compared to that of unirradiated g-C3N4 despite its larger specific surface area.

Therefore, the photocatalytic efficiency can be determined based on the complex counterbalance between the EB- and ultrasonic-induced textural and structural alterations. Sonication and high-dose EB irradiation likely caused opposite changes in the textural features, that is, moderate particle refining and electrostatic coarsening, and led to variations in the specific surface area. Additionally, as previously reported, high-dose EB irradiation results in destructive structural alterations through N elimination, decreasing photocatalytic efficiency.

The aforementioned chemical radiation process and its effects on g-C3N4 have not been thoroughly elucidated. The primary reaction induced by ionizing radiation is electron detachment to form positively charged species, and EB-induced attractive interparticle interaction (electrification followed by particle coarsening) explains the change in the specific surface area. However, the related processes that take place in g-C3N4 remain unclear. To clarify the effects of irradiation on the textural features of g-C3N4, further study is needed on this radiation-chemical process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T.; methodology, A.H. and T.T.; validation, A.H. and T.T.; investigation, A.H., S.S., K.S., and T.T.; resources, A.F. and T.T.; data curation, A.H. and T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T.; writing—review and editing, A.H. and A.F.; visualization, A.H. and T.T.; supervision, A.F. and T.T.; project administration, T.T.; funding acquisition, A.F. and T.T. All authors have read and approved the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Joint Usage/Research Center for Catalysis (Proposal No. 23DS0381).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Joint Usage/Research Center for Catalysis (No. 23DS0381) and the Advanced Research Infrastructure for Materials and Nanotechnology in Japan (ARIM), Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan (Nos. JPMXP1223HK0110 and JPMXP1223CT0053).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Iqbal, W.; Shi, M.; Yang, L.; Chang, N.; Qin, C. Morphology-effects of four different dimensional graphitic carbon nitrides on photocatalytic performance of dye degradation, water oxidation and splitting. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2023, 173, 111109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Hu, W.; Xu, S.; Gao, C.; Li, X. Nitrogen vacancy/oxygen dopants designed nanoscale hollow tubular g-C3N4 with excellent photocatalytic hydrogen evolution and photodegradation. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2023, 180, 111477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Nga, T.T.T; Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Dong, C.-L.; Shen, S. Electron-rich pyrimidine rings enabling crystalline carbon nitride for high-efficiency photocatalytic hydrogen evolution coupled with benzyl alcohol selective oxidation. EES Catal. 2023, 1, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Shi, W.; Lu, J.; Shi, Y.; Guo, F.; Kang, Z. Dual-channels separated mechanism of photo-generated charges over semiconductor photocatalyst for hydrogen evolution: Interfacial charge transfer and transport dynamics insight. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, C.; Wu, L.; Jiao, F. Precise Defect Engineering with Ultrathin Porous Frameworks on g-C3N4 for Synergetic Boosted Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 2665–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, U.; Pal, A. Defect engineered mesoporous 2D graphitic carbon nitride nanosheet photocatalyst for rhodamine B degradation under LED light illumination. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2020, 397, 112582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Yang, D.; Ding, F.; An, K.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, W.; Jiang, Z. One-pot fabrication of porous nitrogen-deficient g-C3N4 with superior photocatalytic performance. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2020, 400, 112729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Fang, W.-X.; Wang, J.-C.; Qiao, X.; Wang, B.; Guo, X. pH-controlled mechanism of photocatalytic RhB degradation over g-C3N4 under sunlight irradiation. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2021, 20, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Li, X.; Song, P.; Ma, F. Porous graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of formaldehyde gas. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021, 762, 138132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, Y.; Sui, X.; Wang, B.; Ma, Y.; Feng, X.; Xu, H.; Mao, Z. g-C3N4 nanosheets exfoliated by green wet ball milling process for photodegradation of organic pollutants. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021, 766, 138335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.A.; Pham, C.T.N.; Ngoc, T.N.; Phi, H.N.; Ta, Q.T.H.; Truong, D.H.; Nguyen, V.T.; Luc, H.H.; Nguyen, L.T.; Dao, N.N.; Kim, S.J.; Vo, V. One-step synthesis of oxygen doped g-C3N4 for enhanced visible-light photodegradation of Rhodamine B. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2021, 151, 109900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Tsai, W.-F.; Wei, W.-H.; Lin, K.-Y.A.; Liu, M.-T.; Nakagawa, K. Hydroxylation and sodium intercalation on g-C3N4 for photocatalytic removal of gaseous formaldehyde. Carbon 2021, 175, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.G.; Hussain, M.Z.; Hammond, N.; Luca, S.V.; Fischer, R.A.; Minceva, M. Synthesis of Highly Active Doped Graphitic Carbon Nitride using Acid-Functionalized Precursors for Efficient Adsorption and Photodegradation of Endocrine-Disrupting Compounds. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202201909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, G.; Ganai, A.M.; Lakshmi, D.V.; Rao, N.N.; Rajarikam, N.; Rao, P.V. Impact of pyrolysis temperature on physicochemical properties of carbon nitride photocatalyst. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2023, 38, 055020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefa, S.; Zografaki, M.; Dimitropouros, M.; Paterakis, G.; Galiotis, C.; Sangeetha, P.; Kiriakidis, G.; Konsolakis, M.; Binas, V. High surface area g-C3N4 nanosheets as superior solar-light photocatalyst for the degradation of parabens. Appl. Phys. A 2023, 129, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Molina, Á.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M.; Morales-Torres, S.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J. Photodegradation of cytostatic drugs by g-C3N4; Synthesis, properties and performance fitted by selecting the appropriate precursor. Catal. Today 2023, 418, 114068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.A.; Huu, H.T.; Ngo, H.N.T.; Ngo, N.N.; Thi, L.N.; Phan, T.T.T.; Nguyen, L.T.; Nguyen, T.L.; Luc, H.H.; Le, V.T.; Vo, V. Magnesiothermic reduction synthesis of N-deficient g-C3N4 with enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible light. Chem. Phys. 2023, 575, 112061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, D.; Kim, S.; Fujitsuka, M.; Majima, T. Defects rich g-C3N4 with mesoporous structure for efficient photocatalytic H2 production under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2018, 238, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Miao, Y.; Ding, G.; Jiao, Z. Two physical strategies to reinforce a nonmetallic photocatalyst, g-C3N4: vacuum heating and electron beam irradiation. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 14002–14008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picho-Chillán, G.; Dante, R.C.; Muños-Bisesti, F.; Martín-Ramos, P.; Chamorro-Posada, P.; Vargas-Jentzsch, P.; Sánchez-Arévalo, F.M.; Sandoval-Pauker, C.; Rutto, D. Photodegradation of Direct Blue 1 azo dye by polymeric carbon nitride irradiated with accelerated electrons. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 237, 121878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.G.; Ta, H.Q.; Yan, X.; Bachmatiuk, A.; Praus, P.; Mamakhel, A.; Iversen, B.B.; Su, R.; Gemming, T.; Rümmeli, M.H. Tailoring the stoichiometry of C3N4 nanosheets under electron beam irradiation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 4747–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, L.; Paramanik, L.; Choi, D.; Yoo, S.H. Advancing photocatalytic performance for enhanced visible-light-driven H2 evolution and Cr(VI) reduction of g-C3N4 through defect engineering via electron beam irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 685, 161996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harako, A.; Shimoda, S.; Suzuki, K.; Fukuoka, A.; Takada, T. Effects of the electron-beam-induced modification of g-C3N4 on its performance in photocatalytic organic dye decomposition. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2023, 813, 140320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cao, Y.; Wang, H.; Yu, H.; Peng, F.; Zou, H.; Liu, Z. Revealing active-site structure of porous nitrogen-defected carbon nitride for highly effective photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 373, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, B.; Dou, M.; Huang, X.; Ma, Z. A porous g-C3N4 nanosheets containing nitrogen defects for enhanced photocatalytic removal meropenem: Mechanism, degradation pathway, and DFT calculation. Environ. Res. 2020, 184, 109339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Jia, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Meng, F.; Wang, D.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Facile synthesis of distinctive nitrogen defect-regulated g-C3N4 for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 142, 110816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Iwasa, N.; Fujita, S.; Koizumi, H.; Yamaguchi, M.; Shimada, T. Porous graphitic carbon nitride nanoplates obtained by a combined exfoliation strategy for enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 499, 143901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yanase, T.; Iwasa, N.; Koizumi, H.; Mukai, S.; Iwamura, S.; Nagahama, T.; Shimada, T. Sugar-assisted mechanochemical exfoliation of graphitic carbon nitride for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 8444–8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Song, C.; Kou, M.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Shimada, T.; Ye, L. Fabrication of ultra-thin g-C3N4 nanoplates for efficient visible-light photocatalytic H2O2 production via two-electron oxygen reduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425, 130615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhan, L.; Ma, L.; Fang, Z.; Vajtai, R.; Wang, X.; Ajayan, P.M. Exfoliated Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanosheets as Efficient Catalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Under Visible Light. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 2452–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, X.; Xu, H.; Xu, Y.; Yan, J.; Xia, J.; Xu, L.; Song, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H. Exfoliated graphene-like carbon nitride in organic solvents: enhanced photocatalytic activity and highly selective and sensitive sensor for the detection of trace amounts of Cu2+. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 2563–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairley, N.; Fernandez, V.; Richard-Plouet, M.; Guillot-Deudon, C.; Walton, J.; Smith, E.; Flahaut, D.; Greiner, M.; Biesinger, M.; Tougaard, S.; Morgan, D.; Baltrusaitis, J. Systematic and collaborative approach to problem solving using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 5, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudouzi, H.; Egashira, M.; Shinya, N. Formation of electrified images using electron and ion beams. J. Electrostat. 1997, 42, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarintsev, A.A.; Zykova, E.Y.; Ieshkin, A.E.; Orikovsaya, N.G.; Rau, E.I. Electrization of the Quartz Glass Surface by Electron Beams. Phys. Solid State 2023, 65, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobashy, M.M.; Sharshir, A.I.; Zaghlool, R.A.; Mohamed, F. Investigating the impact of electron beam irradiation on electrical, magnetic, and optical properties of XLPE/Co3O4 nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, R.; Dou, H.; Chen, L.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, Y. Graphitic carbon nitride with S and O codoping for enhanced visible light photocatalytic performance. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 15842–15850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).