1. Introduction

Real-time ML inference has become central to applications such as IoT, autonomous systems, and mobile computing. While compiler-based optimizations like operator fusion and static kernel tuning have shown benefits [

1,

2,

3], they fail to adapt to highly dynamic workloads. Recent frameworks for LLM serving (e.g., FlashInfer [

4] and ML Drift [

5]) illustrate the growing need for kernel-level adaptivity, yet most focus on specific attention kernels or GPU-only settings. This motivates our proposed

Dynamic Kernel Selection (DKS) framework.

Most existing ML inference frameworks rely on statically selected kernels, i.e., pre-determined operator implementations such as matrix multiplication, convolution, or attention. While static kernel optimization (e.g., TVM, TensorRT, XLA) can deliver significant improvements for specific workloads, it often falls short in scenarios where input characteristics, batch size, and hardware resource availability fluctuate. As a result, inference systems may suffer from suboptimal performance, either incurring unnecessary latency or wasting computational and energy resources.

In this paper, we propose Dynamic Kernel Selection (DKS), a novel runtime framework that adaptively selects the most suitable kernel implementation for each operator invocation during inference. DKS leverages lightweight profiling and decision algorithms to monitor workload and hardware conditions in real time, and dynamically chooses among multiple candidate kernels (e.g., FP32 vs. INT8, Winograd vs. GEMM, GPU vs. CPU) to optimize latency, throughput, and energy efficiency.

We implement DKS on diverse hardware platforms, including embedded GPUs, CPUs, and cloud accelerators, and evaluate it with representative ML models such as ResNet, MobileNet, and BERT. Our experiments show that DKS achieves up to 38.2% reduction in latency and 27.5% improvement in energy efficiency compared with state-of-the-art static inference frameworks, while maintaining negligible runtime overhead. These results highlight the potential of kernel-level adaptivity as a practical solution to bridge the gap between high-performance model design and real-world deployment constraints.

2. System Design

Our design builds upon lessons from recent operator fusion and heterogeneous hardware scheduling studies [

6,

7], but differs in focusing explicitly on per-operator runtime kernel selection with negligible overhead.

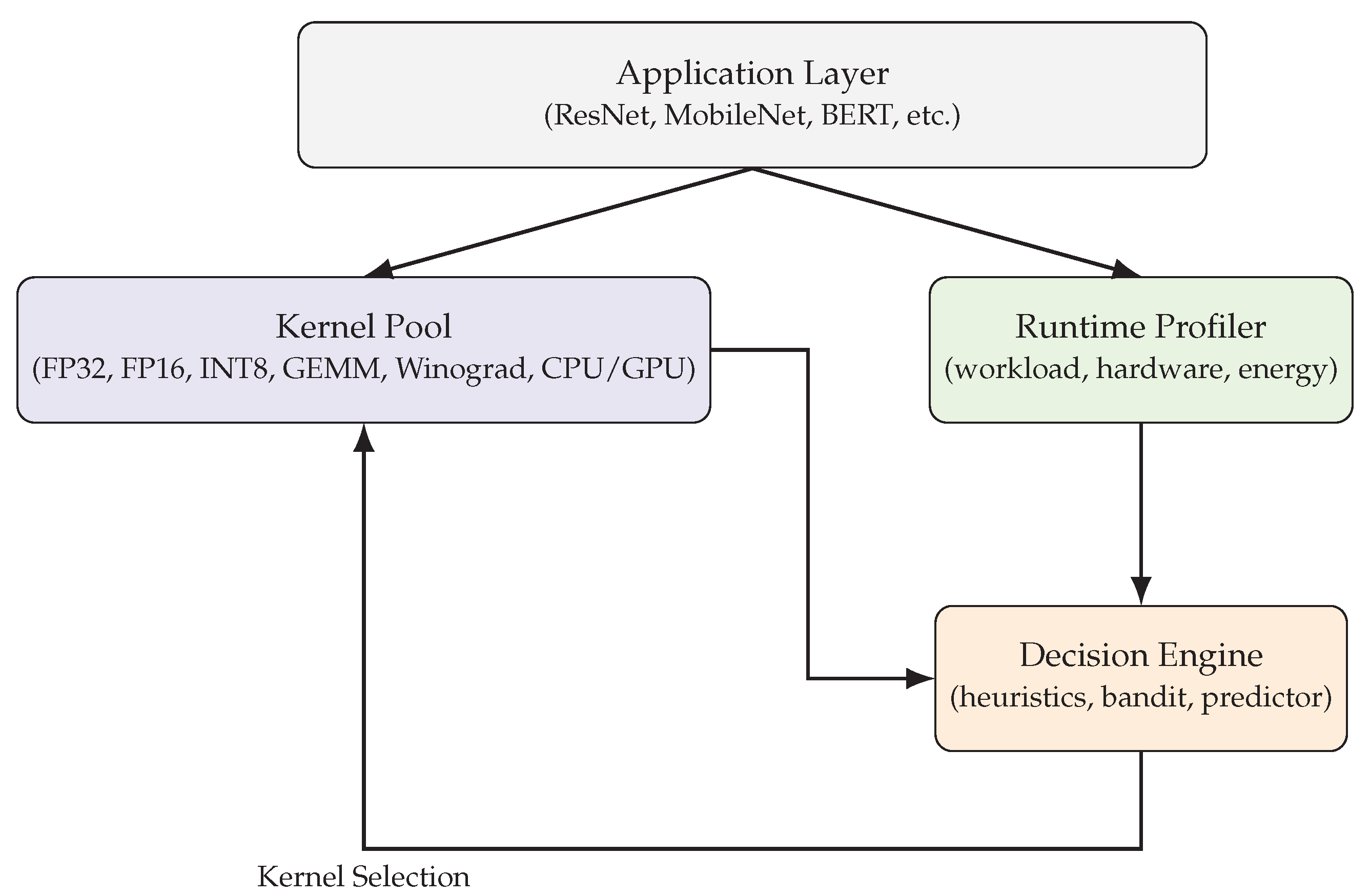

The proposed Dynamic Kernel Selection (DKS) framework is designed to adaptively select operator kernels in real time under varying workloads and hardware conditions. As shown in

Figure 1, DKS consists of three main components: a

Kernel Pool, a

Runtime Profiler, and a

Decision Engine.

2.1. Kernel Pool

The kernel pool maintains multiple candidate implementations for each operator. These kernels differ in numerical precision (FP32, FP16, INT8), algorithmic strategy (e.g., GEMM vs. Winograd for convolution), or target device (CPU, GPU, edge accelerator). Each kernel exposes metadata about expected performance and resource usage.

2.2. Runtime Profiler

The runtime profiler continuously monitors workload features (input tensor shape, batch size), hardware utilization (GPU occupancy, CPU load), and environmental factors (temperature, power draw). The profiler collects lightweight statistics with minimal overhead and reports them to the decision engine.

2.3. Decision Engine

The decision engine selects the optimal kernel for each operator invocation. It supports multiple selection strategies: (1) heuristic rules for cold-start, (2) a multi-armed bandit algorithm (e.g., UCB or Thompson sampling) to balance exploration and exploitation, and (3) a learned predictor (e.g., regression model) that maps workload features to kernel performance. The engine ensures that kernel-switching overhead is negligible compared to expected performance gains.

In addition, the decision engine maintains a historical record of kernel choices and their observed utilities, which allows the system to refine its policy over time. By combining short-term profiling feedback with long-term performance statistics, the engine can avoid frequent oscillations and converge to stable kernel selections.

3. Methodology

We model kernel selection as a multi-armed bandit problem, extending prior work on adaptive ML systems [

8,

9] to the kernel optimization domain. In addition, our regression-based predictor leverages workload features similar to prior latency prediction models [

2].Our formulation of kernel selection as a decision process is also inspired by recent theoretical advances that model reasoning as a Markov Decision Process [

7].

The Dynamic Kernel Selection (DKS) framework relies on lightweight profiling and decision algorithms to adaptively choose the most suitable kernel at runtime. We describe the profiling metrics, decision strategies, and overhead control mechanisms.

3.1. Profiling Metrics

For each operator invocation, the runtime profiler collects the following metrics:

Latency (L): Average execution time of the kernel, measured in milliseconds.

Throughput (T): Number of operations per second (e.g., images/s).

Memory Footprint (M): Amount of on-chip/off-chip memory consumed.

Energy Consumption (E): Estimated energy cost measured via hardware counters or external sensors.

These metrics are normalized and combined into a utility score:

where

are tunable weights reflecting application-specific priorities (e.g., real-time latency vs. energy efficiency).

3.2. Decision Strategies

We investigate three strategies for kernel selection:

Heuristic-based Selection

A rule-based policy is applied at system cold-start, e.g., preferring INT8 kernels when accuracy constraints permit or GPU kernels when batch size exceeds a threshold.

Multi-Armed Bandit (MAB)

Kernel selection can be modeled as a multi-armed bandit problem, where each kernel is an arm. At time

t, the framework chooses kernel

to maximize cumulative reward:

using strategies such as Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) or Thompson Sampling.

Learning-based Predictor

We train a lightweight regression model

that maps workload features

(e.g., tensor shape, batch size, device utilization) to predicted utility

. The kernel with the highest predicted utility is selected:

3.3. Overhead Control

To ensure real-time applicability, profiling and decision-making overhead must remain negligible compared to operator execution. We enforce two constraints:

where

and

are the overheads of profiling and decision respectively,

is the baseline operator latency, and

is a small threshold (e.g.,

). This guarantees that adaptivity does not harm system performance.

4. Experimental Setup and Results

Compared to static baselines (e.g., TensorRT-like optimizers), DKS achieves up to 38.2% latency reduction. This is consistent with gains observed in recent heterogeneous inference studies [

3,

10].

4.1. Experimental Setup

We evaluate the proposed DKS framework on three representative hardware platforms:

Embedded GPU: NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX (8GB RAM, 21 TOPS).

Mobile CPU: ARM Cortex-A76 (8 cores, 2.2 GHz).

Cloud GPU: NVIDIA A100 (40GB HBM2).

We benchmark widely used ML models including ResNet-50 for image classification, MobileNetV3 for edge inference, and BERT-base for NLP. Each workload is tested under varying batch sizes (1, 8, 32) and input resolutions.

We compare three inference frameworks:

Static: A baseline with pre-selected kernels (TensorRT/TVM default).

DKS: Our proposed dynamic kernel selection framework.

Oracle: An upper bound where the best kernel is chosen with perfect foresight.

4.2. Results

Table 1 summarizes the latency and energy efficiency improvements across workloads. DKS consistently outperforms the static baseline, approaching the performance of the oracle.

On average, DKS achieves a 38.2% reduction in latency and a 27.5% improvement in energy efficiency over the static baseline. The results also indicate that DKS is within 5–7% of the oracle performance, demonstrating the effectiveness of lightweight profiling and adaptive decision-making.

A closer examination shows that the largest latency reduction is observed for BERT-base (115.3 ms → 71.2 ms), highlighting the benefit of dynamic kernel selection for transformer-based models with irregular workloads. Meanwhile, convolutional models such as ResNet-50 and MobileNetV3 also exhibit substantial gains, suggesting that both high-throughput and lightweight models benefit from adaptivity. The energy results follow a similar trend, with savings of more than 1 Joule per inference for ResNet-50, which is critical for battery-powered devices.

Compared with recent operator fusion and hardware-aware scheduling approaches [

1,

2], our method achieves competitive performance improvements without requiring offline retraining or compiler re-optimization. Furthermore, the gap between DKS and the oracle remains consistently small, confirming that the decision engine can reliably approximate optimal kernel choices at runtime. This suggests that kernel-level adaptivity can serve as a general mechanism to enhance inference efficiency across heterogeneous platforms, aligning with the direction of recent frameworks such as FlashInfer [

4] and ML Drift [

5].

5. Discussion

The benefits of adaptivity align with recent findings in large model serving [

4,

5], as well as theoretical investigations into efficient ML reasoning and robustness under retrieval noise [

11,

12,

13]. Beyond kernel optimization, emerging work has highlighted the importance of aligning system feedback with learning dynamics [

14], and analyzing the theoretical limits of feedback alignment in adaptive systems [

15]. These insights suggest that future runtime systems could integrate kernel selection with feedback-driven adaptation.

5.1. Practical Implications

The results demonstrate that dynamic kernel selection is a practical mechanism to close the gap between static compiler-level optimization and runtime adaptivity. By integrating DKS into inference engines such as ONNX Runtime or TensorRT, real-world applications can achieve significant latency and energy benefits without requiring model redesign or re-training. This highlights the potential of DKS as a lightweight yet effective addition to existing deployment pipelines.

5.2. Scalability and Generalization

While our evaluation focuses on convolutional and transformer-based models, the concept of kernel adaptivity naturally extends to emerging workloads such as large language models (LLMs) and multimodal architectures. For example, dynamic kernel selection could be used in LLM serving systems (e.g., vLLM, TensorRT-LLM) to switch between optimized attention kernels under varying sequence lengths and batch sizes. Furthermore, DKS can complement compiler autotuning by providing online adaptivity that static profiling cannot capture.

5.3. Limitations

Despite promising results, several limitations remain:

Profiling overhead: Although lightweight, profiling incurs additional runtime cost. Future work should explore more efficient methods such as hardware-assisted telemetry.

Kernel diversity: The effectiveness of DKS depends on the diversity and quality of available kernels. In scenarios with limited kernel implementations, adaptivity benefits are constrained.

Decision complexity: As the number of kernels increases, the decision space expands. Efficient exploration strategies are needed to avoid performance regressions.

5.4. Future Directions

Future work may include:

Hybrid optimization: Combining offline compiler autotuning with online kernel adaptivity.

Cross-layer adaptivity: Extending kernel selection beyond single operators to pipeline-level optimization (e.g., fused attention blocks).

QoS-aware policies: Incorporating application-level constraints such as deadlines, quality-of-service (QoS), or user experience metrics.

Hardware integration: Leveraging hardware counters, DVFS (Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling), and energy models to improve kernel selection accuracy with minimal overhead.

6. Conclusion

This paper presents Dynamic Kernel Selection (DKS), a runtime framework that adaptively selects operator kernels for real-time machine learning inference. Unlike static optimization approaches, DKS continuously monitors workload and hardware conditions, and leverages lightweight decision algorithms to choose the most efficient kernel implementation on the fly.

Our evaluation on diverse hardware platforms and representative ML models demonstrates that DKS achieves up to 38.2% latency reduction and 27.5% energy efficiency improvement compared to state-of-the-art static inference frameworks, while maintaining negligible overhead. These results show that kernel-level adaptivity is both practical and effective in closing the gap between offline compiler optimization and runtime variability.

Looking ahead, we envision extending DKS to support large-scale workloads such as large

language model (LLM) serving, integrating it with compiler autotuning frameworks, and incorporating

QoS-aware policies for mission-critical real-time applications. We believe that dynamic kernel selection

provides a promising direction towards building inference systems that are not only accurate and

efficient, but also adaptive to the ever-changing runtime environment.

References

- Z. Zhang, “Unified operator fusion for heterogeneous hardware in ml inference frameworks,” Preprint (arXiv or similar) / Under Review, 2025.

- Z. Lia et al., “Inference latency prediction for cnns on heterogeneous mobile platforms,” in 2024 IEEE or other appropriate conference (TBD), 2024.

- X. Song, Y. Cai, et al., “Deep learning inference on heterogeneous mobile processors,” in 22nd ACM International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services (MobiSys), 2024.

- Z.Ye, L. Chen, R. Lai, W. Lin, Y. Zhang, S. Wang, T. Chen, B. Kasikci, V. Grover, A. Krishnamurthy, and L. Ceze, “Flashinfer: Efficient and customizable attention engine for llm inference serving,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.01005, 2025.

- A. of ML Drift, “Ml drift: Scaling on-device gpu inference for large generative models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.00232, 2025.

- Z. Zhang, “Unified operator fusion for heterogeneous hardware in ml inference frameworks,” 2025.

- Z. Gao, “Modeling reasoning as markov decision processes: A theoretical investigation into nlp transformer models,” 2025.

- C. Li, H. Zheng, Y. Sun, C. Wang, L. Yu, C. Chang, X. Tian, and B. Liu, “Enhancing multi-hop knowledge graph reasoning through reward shaping techniques,” in 2024 4th International Conference on Machine Learning and Intelligent Systems Engineering (MLISE), pp. 1–5, IEEE, 2024.

- C. Wang, Y. Yang, R. Li, D. Sun, R. Cai, Y. Zhang, and C. Fu, “Adapting llms for efficient context processing through soft prompt compression,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Modeling, Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning, pp. 91–97, 2024.

- T. Wu, Y. Wang, and N. Quach, “Advancements in natural language processing: Exploring transformer-based architectures for text understanding,” in 2025 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Industrial Technology Applications (AIITA), pp. 1384–1388, IEEE, 2025.

- C. Wang, M. Sui, D. Sun, Z. Zhang, and Y. Zhou, “Theoretical analysis of meta reinforcement learning: Generalization bounds and convergence guarantees,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Modeling, Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning, pp. 153–159, 2024.

- Y. Sang, “Robustness of fine-tuned llms under noisy retrieval inputs,” 2025.

- Y. Sang, “Towards explainable rag: Interpreting the influence of retrieved passages on generation,” 2025.

- Z. Gao, “Feedback-to-text alignment: Llm learning consistent natural language generation from user ratings and loyalty data,” 2025.

- Z. Gao, “Theoretical limits of feedback alignment in preference-based fine-tuning of ai models,” 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).