Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background. Loss of smell can impair quality of life. Olfactory disorders (ODs) are often caused by viral infections, such as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The aim of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of olfactory training in patients with post-COVID OD. Materials and methods. The entire group consisted of 75 subjects (15 men and 60 women). They were randomly divided into two groups. Patients in both groups received pharmacological treatment (intranasal corticosteroids and vitamin A), salt irrigations, and elements of speech therapy olfactory training (SOT). Participants in the study group additionally carried out classical olfactory training (OT) using applicators with 4 scents twice a day. Olfactory function was assessed using the Sniffin Sticks' Test (SST). Results. For total SST score, the mean change before and after intervention in the study group was 7.9 points (p < 0.001). In the control group, the mean change was 2.8 points (p = 0.006). Conclusions. Classical OT appears to improve the recovery from post-COVID OD compared to pharmacological therapy with SOT elements alone. The use of intranasal corticosteroids, topical vitamin A, and saline nasal irrigation in our therapy seemed to help in improving olfaction. It is thought that the multidisciplinary team used here – doctor, speech therapist, and psychologist – may have also contributed to the effectiveness of the therapy.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

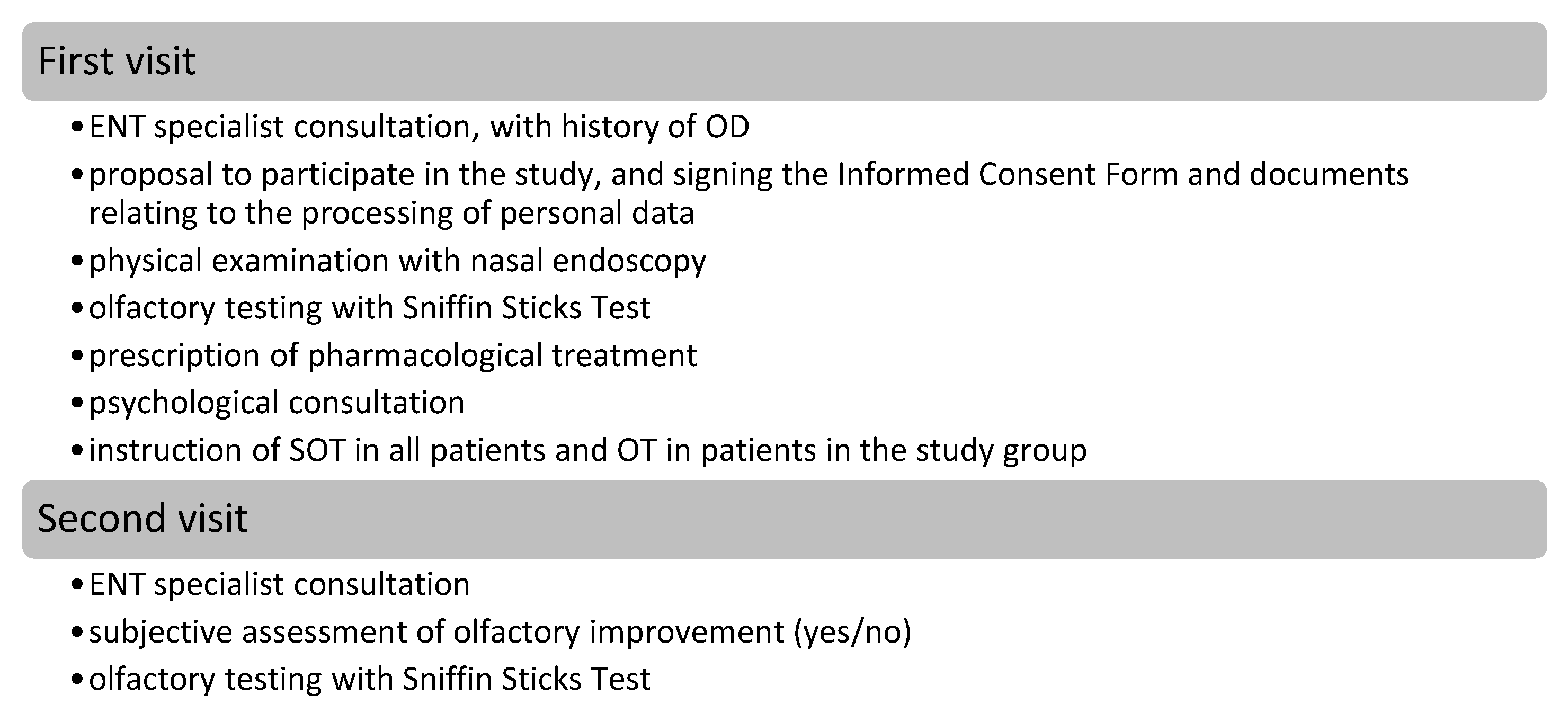

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Group and Control Group

2.4. Olfactory Testing

2.5. ENT Consultation

2.6. Psychological Consultation

2.7. Speech Therapy Olfactory Training (SOT)

2.8. Olfactory Training (OT)

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

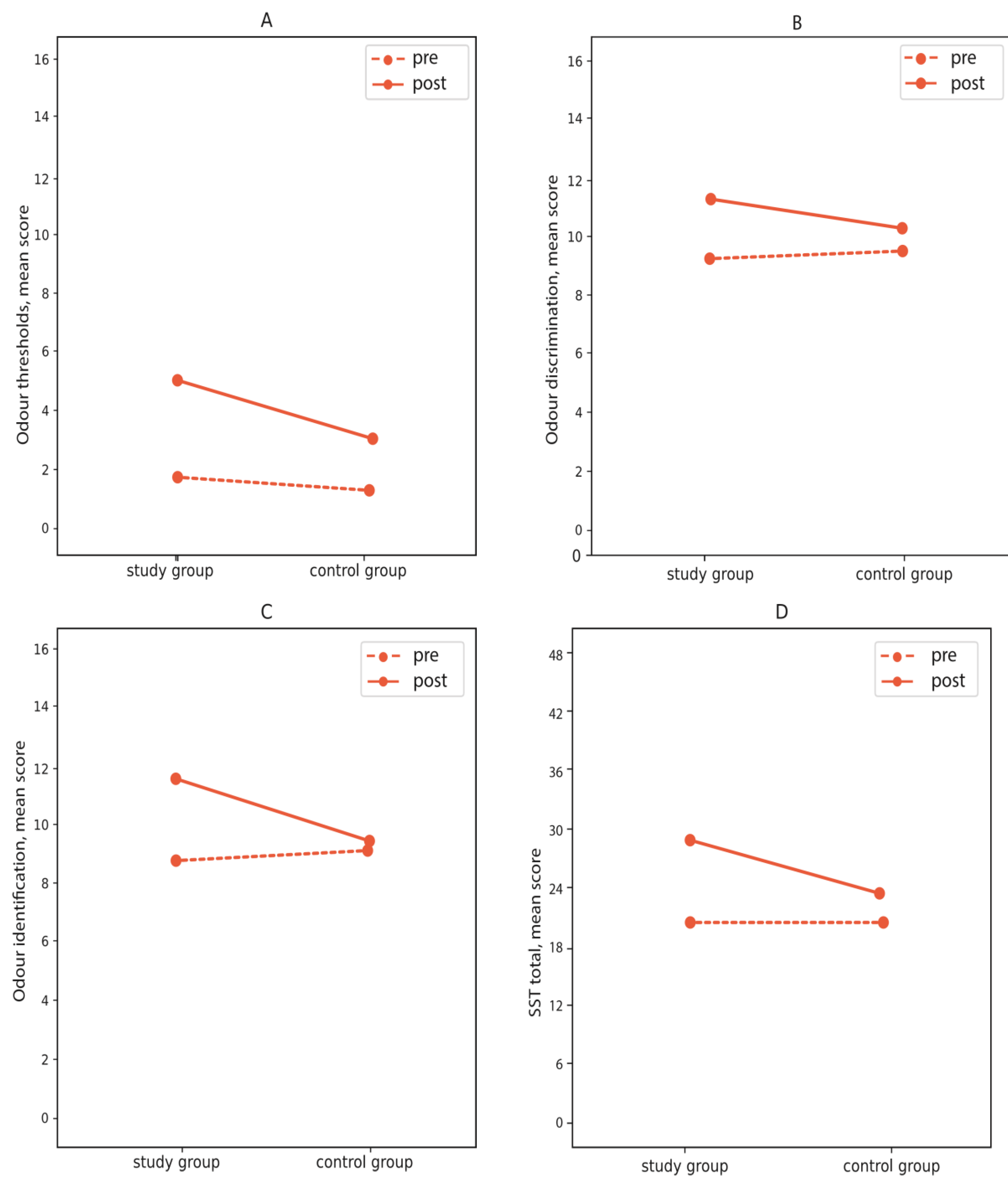

3.2. Change in the Sniffin’ Sticks Test before and after Intervention

3.3. Subjective Improvement and Clinically Significant Improvement in Olfactory Sensitivity

3.4. Improvement in Olfactory Sensitivity in Terms of Age, Gender, Smoking, and Delay in Presentation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saniasiaya, J. & Prepageran, N. Impact of olfactory dysfunction on quality of life in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: a systematic review. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2021, 135, 947–952. [CrossRef]

- Ciofalo, A., Filiaci, F., Romeo, R., Zambetti, G. & Vestri, A. R. Epidemiological aspects of olfactory dysfunction. Rhinology 2006, 44, 78–82.

- Andrews, P. J.; et al. Olfactory and taste dysfunction among mild-to-moderate symptomatic COVID-19 positive health care workers: An international survey. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2020, 5, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsetto, D.; et al. Self-reported alteration of sense of smell or taste in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis on 3563 patients. Rhinology 2020, 58, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman A. A., Chin, K. L., Landersdorfer, C. B., Liew, D. & Ofori-Asenso, R. Smell and Taste Dysfunction in Patients With COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 1621–1631. [CrossRef]

- Reiter, E. R., Coelho, D. H., French, E., Costanzo, R. M., & N3C Consortium. COVID-19-Associated Chemosensory Loss Continues to Decline. Otolaryngol.--Head Neck Surg. Off. J. Am. Acad. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, D. H., Reiter, E. R., French, E. & Costanzo, R. M. Decreasing Incidence of Chemosensory Changes by COVID-19 Variant. Otolaryngol.--Head Neck Surg. Off. J. Am. Acad. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2023, 168, 704–706. [CrossRef]

- Karamali, K., Elliott, M. & Hopkins, C. COVID-19 related olfactory dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 30, 19–25.

- Speth, M. M.; et al. Time scale for resolution of olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19. Rhinology 2020, 58, 404–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torabi, A.; et al. Proinflammatory Cytokines in the Olfactory Mucosa Result in COVID-19 Induced Anosmia. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 1909–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fodoulian, L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Receptors and Entry Genes Are Expressed in the Human Olfactory Neuroepithelium and Brain. iScience 2020, 23, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanjanaumporn J., Aeumjaturapat, S., Snidvongs, K., Seresirikachorn, K. & Chusakul, S. Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: A review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatment options. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 38, 69–77.

- Arndal, E.; et al. Olfactory and Gustatory Outcomes Including Health-Related Quality of Life 3–6 and 12 Months after Severe-to-Critical COVID-19: A SECURe Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buksinska M., Skarzynski, P. H., Raj-Koziak, D., Gos, E. & Talarek, M. Persistent Olfactory and Taste Dysfunction after COVID-19. Life 2024, 14, 317.

- Boscolo-Rizzo, P.; et al. High prevalence of long-term olfactory, gustatory, and chemesthesis dysfunction in post-COVID-19 patients: a matched case-control study with one-year follow-up using a comprehensive psychophysical evaluation. Rhinol. J. 2021, 0, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitcroft, K. L.; et al. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction: 2023. Rhinology 2023, 61, 1–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak-Firadza, R. Zmysł węchu – istota, zaburzenia, diagnoza, terapia (Na przykładzie logopedy pracującego z dziećmi). 2021. [CrossRef]

- Buksińska, M., Tomaszewska-Hert, I. & Skarżyński, P. H. Subiektywne metody badania węchu – przegląd wybranych narzędzi diagnostycznych. Nowa Audiofonologia 2024, 13, 7–19. [CrossRef]

- Hummel, T., Sekinger, B., Wolf, S. R., Pauli, E. & Kobal, G. ‘Sniffin’ Sticks’: Olfactory Performance Assessed by the Combined Testing of Odor Identification, Odor Discrimination and Olfactory Threshold. Chem. Senses 1997, 22, 39–52. [CrossRef]

- Sorokowska, A. & Hummel, T. Polska wersja testu Sniffin’ Sticks – adaptacja i normalizacja. Otolaryngol. Pol. 2014, 68, 308–314. [CrossRef]

- Hummel, T., Kobal, G., Gudziol, H. & Mackay-Sim, A. Normative data for the “Sniffin’ Sticks” including tests of odor identification, odor discrimination, and olfactory thresholds: an upgrade based on a group of more than 3,000 subjects. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2007, 264, 237–243. [CrossRef]

- Skarżyńska, M. B. Leki recepturowe stosowane donosowo i w farmakoterapii chorób zatok w codziennej praktyce otorynolaryngologicznej – możliwości, wskazania, wyzwania. Nowa Audiofonologia 2022, 11, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gudziol, V., Lötsch, J., Hähner, A., Zahnert, T. & Hummel, T. Clinical significance of results from olfactory testing. The Laryngoscope 2006, 116, 1858–1863.

- Li, Z., Anne, A. & Hummel, T. Olfactory training: effects of multisensory integration, attention towards odors and physical activity. Chem. Senses 2023, 48, bjad037.

- Hummel, T.; et al. Effects of olfactory training in patients with olfactory loss. The Laryngoscope 2009, 119, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thesen, T., Vibell, J. F., Calvert, G. A. & Österbauer, R. A. Neuroimaging of multisensory processing in vision, audition, touch, and olfaction. Cogn. Process. 2004, 5, 84–93.

- Vandersteen, C.; et al. Persistent post-COVID-19 dysosmia: Practices survey of members of the French National Union of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Specialists. CROSS analysis. CROSS analysis. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fleiner, F., Lau, L. & Göktas, Ö. Active Olfactory Training for the treatment of Smelling Disorders. Ear. Nose. Throat J. 2012, 91, 198–215.

- Scangas, G. A. & Bleier, B. S. Anosmia: Differential diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2017, 31, 3–7.

- Kasiri, H., Rouhani, N., Salehifar, E., Ghazaeian, M. & Fallah, S. Mometasone furoate nasal spray in the treatment of patients with COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction: A randomized, double blind clinical trial. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 98, 107871.

- Abdelalim, A. A., Mohamady, A. A., Elsayed, R. A., Elawady, M. A. & Ghallab, A. F. Corticosteroid nasal spray for recovery of smell sensation in COVID-19 patients: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 42, 102884.

- Wang, J.-Y.; et al. Corticosteroids for COVID-19-induced olfactory dysfunction: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0289172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiri, M. & Emadzadeh, M. The Effect of Corticosteroids on Post-Covid-19 Smell Loss: A Meta-Analysis. Iran. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 35, 235–246.

- Schwob, J. E. Neural regeneration and the peripheral olfactory system. Anat. Rec. 2002, 269, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J. E. & Blomhoff, R. Gene expression regulation by retinoic acid. J. Lipid Res. 2002, 43, 1773–1808.

- Rawson, N. E. & LaMantia, A.-S. A speculative essay on retinoic acid regulation of neural stem cells in the developing and aging olfactory system. Exp. Gerontol. 2007, 42, 46–53.

- Reden, J., Lill, K., Zahnert, T., Haehner, A. & Hummel, T. Olfactory function in patients with postinfectious and posttraumatic smell disorders before and after treatment with vitamin A: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. The Laryngoscope 2012, 122, 1906–1909.

- Hummel, T., Whitcroft, K. L., Rueter, G. & Haehner, A. Intranasal vitamin A is beneficial in post-infectious olfactory loss. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Off. J. Eur. Fed. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Soc. EUFOS Affil. Ger. Soc. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. - Head Neck Surg. 2017, 274, 2819–2825.

- Succar, E. F., Turner, J. H. & Chandra, R. K. Nasal saline irrigation: a clinical update. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019, 9, S4–S8.

- Yuan, T.-F. & Slotnick, B. M. Roles of olfactory system dysfunction in depression. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 54, 26–30.

- Mahmut, M. K., Fitzek, J., Bittrich, K., Oleszkiewicz, A. & Hummel, T. Can focused mindfulness training increase olfactory perception? A novel method and approach for quantifying olfactory perception. Sens. Stud. 2021, 36, e12631.

- Oleszkiewicz, A.; et al. Odours count: human olfactory ecology appears to be helpful in the improvement of the sense of smell. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, M., Raninger, J., Kaiser, J., Mueller, C. A. & Liu, D. T. Treatment adherence to olfactory training: a real-world observational study. Rhinology. 2024 Feb 1;62(1):35-45.

| Formula | Dosage |

|---|---|

| Liquid vitamin A 1,0 g Lanoline 3,0 g Liquid paraffin 3,0 g Vaseline 3,0 g Mixed into an ointment |

2 times a day into both nasal cavities |

| Study group (n = 50) | Control group (n = 25) | |||||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Thresholds | 1.87 | 2.34 | 5.11 | 3.98 | 1.41 | 1.55 | 3.04 | 3.03 |

| Discrimination | 9.28 | 3.14 | 11.30 | 2.55 | 9.52 | 2.80 | 10.28 | 3.05 |

| Identification | 8.74 | 2.94 | 11.54 | 3.35 | 9.12 | 3.29 | 9.40 | 3.33 |

| Total score | 19.91 | 6.57 | 27.85 | 8.22 | 20.05 | 5.97 | 22.80 | 6.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).