Introduction

Humour is a complex communicative resource with social, affective and cognitive functions. One of its most controversial forms is sarcastic humour, also called ironic or critical humour, characterised by the contradiction between the literal meaning and the communicative intention, which allows indirect messages to be sent for playful purposes or veiled criticism in the face of uncomfortable situations (

Gibbs & Colston, 2007). From psychology, sarcasm has been described both as an adaptive coping strategy, useful for releasing tensions or softening conflicts, and as a covert form of verbal aggression that can affect interpersonal relationships (

Dynel, 2017). International studies show the relevance of the phenomenon. In Indonesia, 76% of students reported high use of sarcasm and 70% experienced frequent misunderstandings in communication, demonstrating that the greater the use of sarcasm, the greater the risk of conflict in social interaction (

Suwendri & Manggalani, 2025). Likewise, in Italy, 35.7% of students manifested a type of humor directly related to their personality traits, which reveals its influence on individual identity (

Ortiz Pérez & Yamo Vallejos, 2023).

Although there are tools, such as the Humor Styles Questionnaire (HSQ) developed by Martín et al. (2003), aimed at examining humorous styles in general, they do not specifically include sarcastic humor or its critical element. This restriction highlights the creation of a psychometric instrument that allows the exact measurement of sarcastic critical humor in university students in the appropriate context, considering its possible effect on academic coexistence, emotional well-being and student productivity. Within the university environment, sarcasm usually appears in conversations between students almost unnoticed, as part of their usual way of communicating. It is often used to joke or to express something without saying it directly, but rarely do we think about how it can affect others or the emotions it can arouse. Within the university environment, sarcasm usually appears in conversations between students almost unnoticed, as part of their usual way of communicating. It is often used to joke or to express something without saying it directly, but rarely do we think about how it can affect others or the emotions it can arouse. Based on this idea, the study seeks to understand how sarcasm influences coexistence, the way people manage their emotions and the possible conflicts that arise in the academic environment. It is hoped that what has been found will help to propose actions that favor a healthier coexistence and better emotional well-being among young university students.

The work is also associated with Sustainable Development Goal No. 3, which seeks to promote health and well-being for all people. The research is based on the importance of designing a tool that contributes to a more accurate analysis of sarcastic critical humor, since so far there are few studies that address it within the university context.

The findings of this work could be useful for students, teachers, and mental health experts, because they would make it possible to recognize sarcastic patterns that impact coexistence and interpersonal relationships. They would also make it possible to detect potential associated risks, such as misunderstandings or conflicts, thus contributing to the creation of more effective preventive strategies.

This study, from the theoretical perspective, contributes to the development of psychological knowledge of humor, since it deals with an aspect that has been little studied. In methodological terms, the IHCD-25 is a tool adapted to the local context that improves future research on emotional well-being, communication and mood. Thus, the creation and validation of the critical sarcastic humor inventory satisfies a need of a scientific and social order: by providing a deeper understanding of sarcasm as a possible coping mechanism or source of conflict in university life.

Thus, the general purpose of the research is to design and establish the psychometric characteristics of the sarcastic critical humor inventory (SCCI-25) in a sample of university students in Trujillo. The particular objectives include: to prepare the instrument specification table; collect evidence of validity based on content; carry out a descriptive analysis of the items; validate the internal structure; examine validity with respect to other variables; calculate the degree of reliability obtained by means of the internal consistency analysis and, at the end, define interpretative rules and cut-off points for the scale.

Method

Study Design:

This is an observational, non-experimental and cross-sectional study, since no variable was altered and the variable analyzed was examined at a single time point. Considered as an instrumental design and its objective was to build and evaluate the psychometric properties of the Critical-Sarcastic Humor Inventory (IHCD-25) in university students in the city of Trujillo (American Educational Research Association et al., 2018; Ato et al. 2013))

Procedure and Participant:

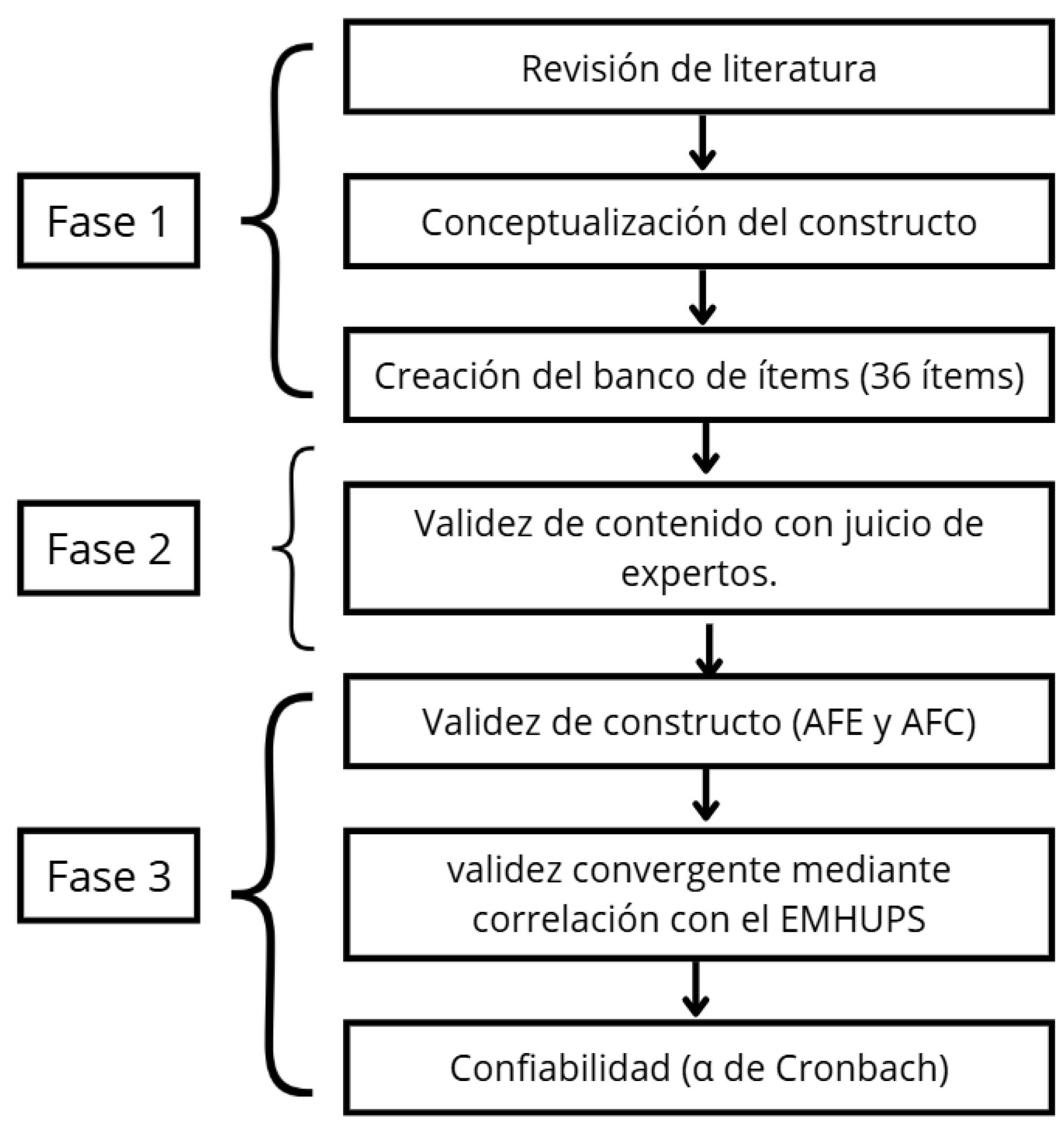

The present study was carried out in three sequential phases that were described in detail in

Figure 1. During the process, a total of 400 people participated, who were intentionally selected taking into consideration previously established inclusion and exclusion criteria, criteria that were applied in order to cover the relevance and validity of the sample and criteria that are exposed in detail in phase III of the study. This methodological structure made it possible to strictly distribute each of the phases of the research process and thus guarantee the same coherence and robustness of the results obtained.

First phase: Development of the items

In the initial part, a preliminary version of the scale was developed, taking a rigorous review of the scientific literature and the analysis of instruments previously developed to evaluate sarcastic critical humor, from the information obtained, the conceptual definition of the construct "Sarcastic Critical Humor" and its theoretical dimensions was established, which guided the construction of the initial items of the instrument; initially, the inventory consisted of 36 items (

Villota et al., 2023). Subsequently, the items were reviewed and refined, when this process was completed, a preliminary version of the instrument was obtained with the same number of items, which was then submitted to evaluation by expert judgment.

Second phase: Validity of the content of the items

In this second phase, the validity of content was evaluated through the expert judgment method, this was achieved with the voluntary participation of eight specialists in the psychology career (American Educational Research Association et al., 2018), specifically, the inclusion criteria required that the participants be from public and private universities, who wished to participate voluntarily, had a committed age of 17 to 30 years, of both sexes and who completed the entire instrument. Likewise, the experts carried out an evaluation of each item in a single round, taking into consideration the necessary aspects such as clarity, coherence and relevance of the content, after that, they assigned the scores that were statistically analyzed using the Aiken V test, in order to correctly determine the consistency of their assessments. it should be noted that this instrument adopted a Likert-type response format with four options: 1 = "never", 2 = "almost never", 3 = "almost always" and 4 = "always"; Finally, each dimension obtained a score by adding the items belonging to each one specifically.

Third phase: Evaluation of psychometric properties

In the third phase, the instrument was applied to evaluate its psychometric properties. The reference population was made up of Peruvian university students. Since there were no specific official figures for the city of Trujillo, the national total of university students reported by the Ministry of Education (MINEDU, 2023) was taken as a reference, which amounts to 1,423,731 students.

For the selection of the sample, a non-probabilistic convenience sampling was used (Hernández-Sampieri & Mendoza, 2018; Ñaupas Paitán et al., 2018). 400 university students participated, who were distributed in two subsamples: the first, made up of 200 students, was destined to the Exploratory Factor Analysis (AFE), which was 36 items, while the second, also made up of 200 students, which was 33 items, was used for the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). This division responded to the methodological recommendations of

Byrne et al. (

1989) and

Ferrando et al. (

2022), who suggest independent subsamples for the validation of the factor structure of psychometric instruments.

Instrument

The inventory of Sarcastic Critical Humor (IHCD-25) was created by Avalos Blas, Catyel Alessandra, Avalos Rubio, Carmen del Pilar Maryory, Blas Cerdan, Dayana Yarle and Vaca Estela, Diana Lizeth. It consists of 33 items, which are distributed in three dimensions: Subtle Humor, Defensive Humor and Covert Social Criticism.

Each item is answered on a four-option Likert scale: always (4), almost always (3), almost never (2), and never (1). This instrument has demonstrated appropriate levels of content validity and internal consistency. The application lasts 10 to 5 minutes, and is done online for university students in Trujillo.

Statistical analysis

For the treatment of the data, first, descriptive analyses of the items were performed, which included the calculation of the mean, mode, standard deviation, asymmetry, kurtosis, corrected homogeneity index and communality. These indicators allowed us to examine the distribution of responses and the correlation of items in each dimension of the instrument. All analyses were carried out using the statistical programs JAMOVI (V25) and JASP.

Subsequently, the internal structure of the instrument was evaluated in two complementary stages. In the first, Exploratory Factor Analysis (AFE) was applied, previously verifying the normality of the items using the Mardia test. In cases where the data presented a normal distribution, the Pearson correlation matrix was used; otherwise, the polychoric matrix was used. Factor extraction was performed using parallel analysis with oblique rotation (Oblimin), eliminating those items that presented factor loads lower than 0.40, following the recommendations of

Ferrando et al. (

2022) and

Ferrando and Lorenzo-Seva (

2014).

In the second stage, the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was carried out, considering for the evaluation of the fit of the model the Chi-Square indices (χ²), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), with reference values greater than 0.90, and the RMSEA and SRMR error indices.

Finally, the reliability of the instrument was analyzed using internal consistency, using Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega coefficients, and those values above 0.75 were considered acceptable.

Ethical Aspects

The research was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the César Vallejo University, the Code of Ethics of the APA and the Code of Ethics of the College of Psychologists of Peru. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, ensuring their autonomy, privacy, and confidentiality of information. Likewise, principles of intellectual honesty, scientific integrity and originality in the collection, analysis and presentation of data were respected.

Results

Table 1 presents the results of the content validity of the Sarcastic Critical Humor Inventory (IHCD-25), obtained from the evaluation of 08 expert judges using Aiken's V coefficient, considering the dimensions of clarity, coherence and relevance.

The data showed that all the items reached a value of V = 1.00 in the three dimensions, with confidence intervals between 0.57 and 1.00, these values far exceeded the minimum criterion of acceptability (V > .80).

Table 2 presents the content validity of the Sarcastic Critical Humor Inventory (IHCD-25) corresponding to items d19 to e36, evaluated by 08 expert judges using Aiken's V coefficient in the dimensions of clarity, coherence and relevance. The results showed values of V = 1.00 in all items, with confidence intervals that fluctuated between 0.57 and 1.00.

Table 2.

Content Validity of the Sarcastic Critical Humor Inventory (IHCD-25).

Table 2.

Content Validity of the Sarcastic Critical Humor Inventory (IHCD-25).

| |

Clarity |

Coherence |

Relevance |

| M |

V |

95% CI |

M |

V |

95% CI |

M |

V |

95% CI |

| |

L |

|

Or |

|

|

L |

|

Or |

|

|

L |

|

Or |

|

| D19 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| D20 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| D21 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| D22 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| D23 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| D24 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| E25 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| e26 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| E27 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| E28 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| E29 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| E30 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| E31 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| e32 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| E33 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| e34 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| E35 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

| E36 |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

1,0 |

1,00 |

[ |

0,57 |

- |

1,00 |

] |

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistical Analysis of Sarcastic Critical Humor Inventory (IHCD-25).

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistical Analysis of Sarcastic Critical Humor Inventory (IHCD-25).

| Dimensions |

Items |

Frequency |

M |

OF |

g1 |

g2 |

h2 |

IHC |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Humour

Subtle |

5 |

32,00

|

44,50

|

13,00

|

10,50

|

2,02 |

0,935 |

0,743 |

-0,225 |

0,352 |

0,712 |

| 10 |

47,50

|

32,50

|

10,00

|

10,00

|

1,82 |

0,974 |

1,02 |

-7.78e-5 |

0,32 |

0,697 |

| 6 |

23,50

|

45,50

|

22,50

|

8,50

|

2,16 |

0,882 |

0,435 |

-0,46 |

0,383 |

0,722 |

| 2 |

38,50

|

31,50

|

19,00

|

11,00

|

2,02 |

1,01 |

0,601 |

-0,783 |

0,32 |

0,747 |

| 9 |

28,00

|

34,00

|

28,50

|

9,50

|

2,19 |

0,955 |

0,265 |

-0,927 |

0,505 |

0,668 |

| 4 |

53,50

|

27,50

|

10,50

|

8,50

|

1,74 |

0,958 |

1,13 |

0,211 |

0,348 |

0,701 |

| 11 |

26,00

|

33,50

|

27,50

|

13,00

|

2,27 |

0,992 |

0,235 |

-0,997 |

0,45 |

0,721 |

| 3 |

24,00

|

35,00

|

28,50

|

12,50

|

2,29 |

0,971 |

0,21 |

-0,943 |

0,33 |

0,724 |

| 1 |

30,00

|

32,00

|

28,50

|

9,50

|

2,17 |

0,969 |

0,278 |

-0,981 |

0,464 |

0,709 |

| 12 |

38,00

|

33,50

|

19,50

|

9,00

|

2 |

0,969 |

0,612 |

-0,669 |

0,346 |

0,718 |

| 7 |

29,50

|

33,00

|

26,00

|

11,50

|

2,19 |

0,991 |

0,319 |

-0,97 |

0,33 |

0,76 |

| 8 |

31,50

|

30,00

|

31,00

|

7,50

|

2,15 |

0,953 |

0,233 |

-1,04 |

0,432 |

0,707 |

In this table, the Subtle Humor dimension was observed, that the response frequencies ranged between 8.5% and 53.5%, at the same time, in the mean (M), the values varied between 1.74 and 2.29; and in the standard deviation (SD) they were found between 0.88 and 1.01.

Regarding asymmetry (g1), the values ranged from 0.21 to 1.13, while kurtosis (g2) fluctuated between -1.04 and 1.13. Likewise, the corrected homogeneity index (IHC) was between 0.66 and 0.75, which indicated an adequate internal consistency of the items. Finally, communalities (h2) presented values higher than 0.30.

Table 4 showed that the response frequencies of the items in the Defensive Humor dimension of the Sarcastic Critical Humor Inventory (IHCD-25) ranged from 8.0% to 43.0%, while the mean (M) ranged from 2.21 to 2.56. On the other hand, the standard deviation (SD) presented values between 0.92 and 1.02. In relation to asymmetry (g1), the results were found between -0.20 and 0.49, while kurtosis (g2) ranged from -1.10 to -0.83. On the other hand, the corrected homogeneity index (CFI) varied between 0.63 and 0.79, being higher than the recommended minimum of 0.50. Finally, communalities (h2) presented values higher than 0.26.

Table 5 showed that the response frequencies of the items in the Covert Social Criticism dimension of the Sarcastic Critical Humor Inventory (IHCD-25) ranged from 9.0% to 39.5%. As for the mean (M), the values ranged between 2.12 and 2.33. The standard deviation (SD) fluctuated between 0.93 and 1.03.

In relation to asymmetry (g1), the values ranged from -0.35 to 0.43, while kurtosis (g2) ranged from -1.16 to -0.58. On the other hand, the corrected homogeneity index (IHC) presented values between 0.65 and 0.80. Finally, communalities (h2) registered values above 0.26.

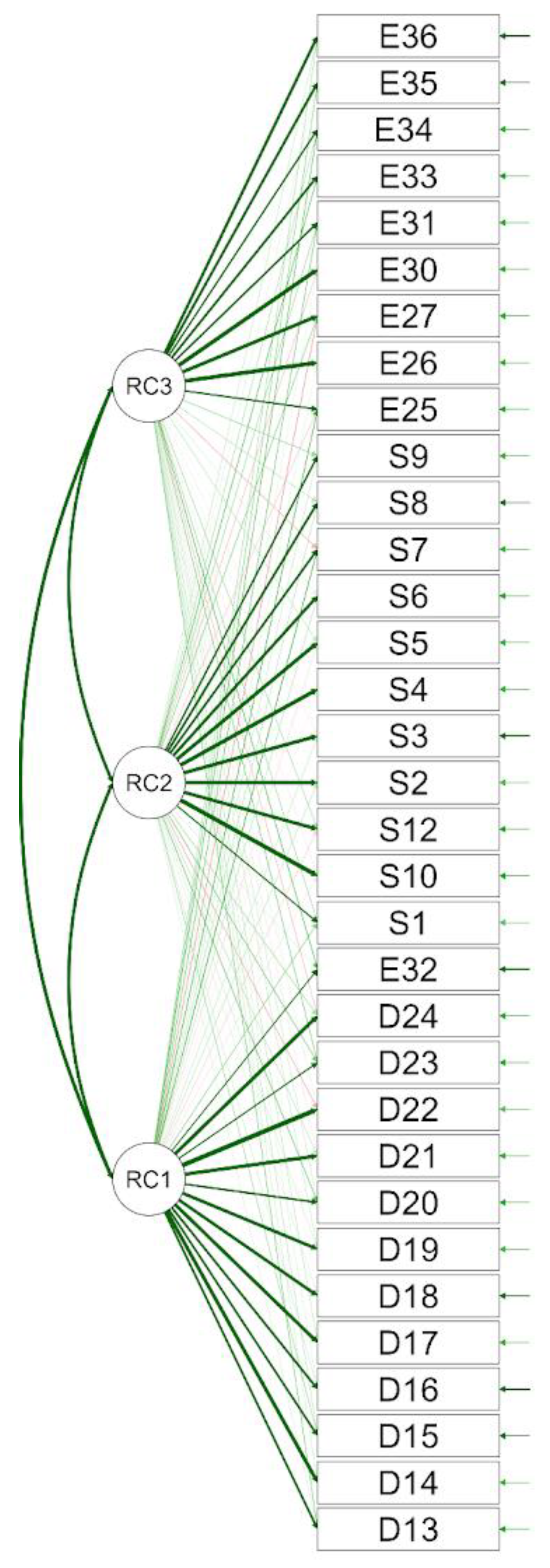

Table 6 presented the results of the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) performed on the Sarcastic Critical Humor Inventory (IHCD-25) in its global structure. Two three-factor models were contrasted: one with 33 items and the other with 35 items.

In the first model (33 items), the fit indices showed adequate values: χ² (670.574; df = 432, p < .001), with an SRMR = 0.029 and an RMSEA = 0.052, both within the recommended parameters (< .08). Likewise, the goodness-of-fit indices CFI = 0.953 and TLI = 0.942 exceeded the threshold of 0.90.

On the other hand, the second model (35 items) also presented adequate values (χ² = 6092.756; df = 595, p < .001), with an SRMR = 0.030 and an RMSEA = 0.053, remaining at optimal levels (< .08). Similarly, the incremental adjustment indices (CFI = 0.949 and TLI = 0.938) were above 0.90.

In

Table 7, the values of the factor loads ranged between 0.452 and 0.916, with item D22 having the highest load (0.916) and item E32 having the lowest load (0.452), at the same time, the cumulative explained variance reached 63.6%. In addition, the KMO sample adequacy index was 0.966, while Bartlett's sphericity test presented a value of p < 0.001.

a. Diagram of the factors that make up the instrument

Figure 1 shows the structure of the dimensions of subtle humor, defensive humor, and covert social criticism, which made up the Inventory of Sarcastic Critical Humor (IHCD-25). 3 factors were appreciated, which made up the instrument.

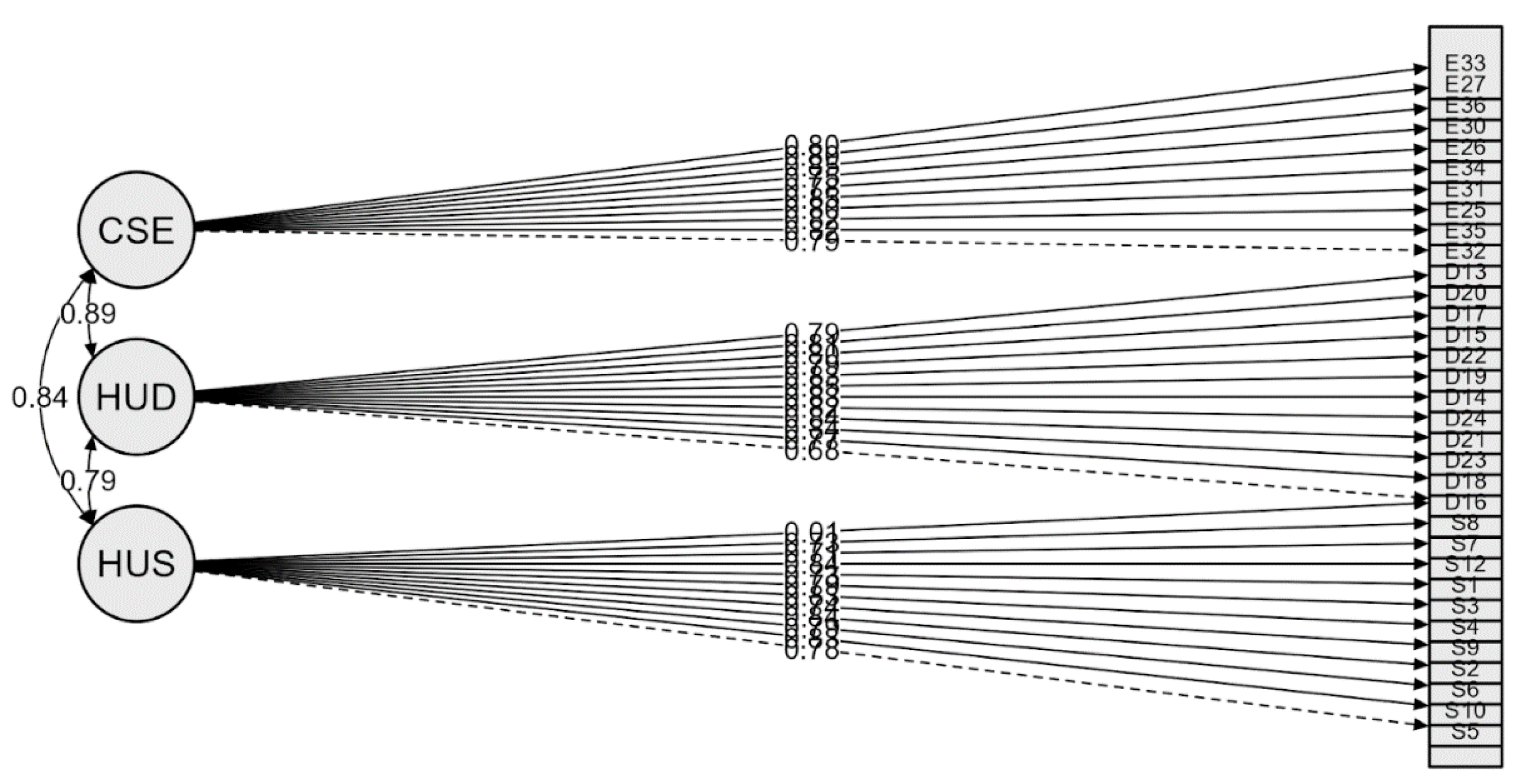

Table 8 shows confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) from the Sarcastic Critical Humor Inventory (IHCD-25) in two models: one one-dimensional and the other three-dimensional. Both models showed statistical significance in the chi-square test. However, additional fit indicators favored the three-factor model, reflecting a better fit (X²(491) = 1039.04, CFI = 0.908, TLI = 0.901, SRMR = 0.051, and RMSEA = 0.075). In contrast, the one-dimensional model presented a poor fit (X²(495) = 1579.80, CFI = 0.818, TLI = 0.806, RMSEA = 0.105, SRMR = 0.061). In this way, the model proposed in the exploratory factor analysis (AFE) was confirmed, validating the structure of three factors and 33 items of the inventory.

b. Diagram of the factors that make up the instrument

Figure 2 presents the confirmatory factor model of the IHCD-25, made up of three dimensions: Subtle Humor (HUS), Defensive Humor (HUD), and Covert Social Criticism (CSE). These dimensions represented the final structure of the instrument.

Table 9 presents the results of the correlation between the Sarcastic Critical Humor Inventory (IHCD-25) and the EMHUPS Scale, used as an external variable. It was evidenced that Spearman's correlation coefficient was negative and of low magnitude (ρ = -0.142), although statistically significant (p = 0.044). Likewise, the coefficient of determination obtained (r² = 0.02) indicated that only 2% of the variability of one scale could be explained by the other. In this way, the data reflected an inverse and weak relationship between both measures.

Table 10 presented the reliability coefficients by internal consistency (Omega). In the total scale, a value of ω = .978 was obtained, while in the specific dimensions the results were: Subtle Humor (ω = .946), Defensive Humor (ω = .967) and Covert Social Criticism (ω = .949). These values exceeded the threshold of .90, which indicated excellent internal consistency.

Percentile Norms

Table 11 presents the percentile norms of the Sarcastic Critical Humor Inventory (IHCD-25) in university students in the city of Trujillo. First, it was observed that the average scores obtained corresponded to 25 in Subtle Humor, 28.7 in Defensive Humor and 26.9 in Covert Social Criticism, while the total score of Sarcastic Critical Humor reached an average value of 80.6. Likewise, the values considered within the normal range were between the 25th and 75th percentiles, so those individuals who exceeded the 75th percentile showed a more accentuated critical and sarcastic style of humor, in contrast to those who were below the 25th percentile, who showed a more limited use of this type of humor.

In the same way, when analyzing the dimensions, it was observed that high scores in Subtle Humor were related to the use of indirect comments and double meanings, which were usually socially accepted, but could express implicit criticism towards others. In relation to Defensive Humor, the high scores reflected a tendency to use humor as a mechanism of self-protection against situations of tension or criticism, because this style allowed to preserve the self-image and deflect discomfort. Covertly, the high levels of scoring corresponded to the use of humor in using positive elements to subvert those business aspects, the proposed roles or the situations of injustice that it shows. A style that also gives a glimpse of the implicit opposition to the normative in the Construction of the Environment aspect. Finally, when observing a total score of Sarcastic Critical Humor, it was concluded that people with higher levels of score translated a general style of sarcasm, irony and oral offensiveness, a resource that has probably been creative and denunciatory, although it must be considered that it can also cause tension and conflict in interpersonal relationships.

Discussion

Critical sarcastic humor is a type of communication that fuses covert mockery with social criticism and irony. In this type of humor, what is expressed literally often contradicts the true purpose of the message. According to Dynel (2017) and

Gibbs and Colston (

2007) it can serve as an approach to deal with difficulties and reduce tensions, although it can also be transformed into a covert form of verbal hostility that negatively affects interpersonal relationships. In the university context, due to its impact on students' relationships, coexistence, and quality of social life (

Villota et al., 2023). That is why it is essential to have a tool that is both reliable and valid to carry out an accurate measurement of this variable. From this perspective, the Inventory of Sarcastic Critical Humor (IHCD-25) was developed in order to study its psychometric characteristics in a group of university students in the city of Trujillo.

The first objective was the elaboration of the table of specifications, which included both the operation of the variable and the consistency matrix, 36 items were created to achieve this, which were organized according to the principle of theoretical relevance and clarity. To reduce social tendency and desirability, statements were written in language that students could understand and distributed randomly. Likewise, the Likert scale of four response possibilities (Almost never, Never, Almost always and Always) was used, which facilitated the obtaining of information in intervals and simplified the statistical analysis. This made it possible to ensure that each element accurately showed the subtleties of the variable and that the instrument was relevant and representative from its original conception.

The second objective is to gather evidence of content validity through the judgment of eight experts, who evaluate the clarity, coherence and relevance of each item. The results indicate values of V = 1.00 in all items, with confidence intervals between 0.57 and 1.00, far exceeding the minimum criterion of 0.80 (American Educational Research Association et al., 2018). These findings demonstrate that the content of the IHCD-25 is highly consistent with the theoretical definition of the variable, which reinforces the validity of the instrument. Unlike other psychometric studies where some items are eliminated or reformulated, in this case it is not necessary to modify any reagents, which reflects the conceptual solidity achieved from the construction phase.

The third objective is to perform the descriptive analysis of the items. In all three dimensions, balanced response frequencies and moderate mean values are observed, with standard deviations within the expected ranges. The asymmetry and kurtosis indices remain within ±1.5, which shows normality in the responses. Likewise, the corrected homogeneity indices exceed the minimum recommended value of 0.50 and the communalities are greater than 0.30, which indicates that the items are adequately related to their factors. These results confirm that the instrument measures the construct homogeneously and accurately, avoiding problems of isolated or non-representative items. Thus, the IHCD-25 shows a coherent structure with the theoretical proposal, in which each dimension reflects differentiated, but interrelated, aspects of sarcastic humor.

In relation to the fourth objective, the validity of the internal structure is verified by means of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In the AFE, carried out with 36 items, a KMO index of 0.966 and an explained variance of 63.6% are obtained, with factor loads ranging between 0.452 and 0.916. These values show that the items are consistently grouped around the proposed theoretical dimensions. Subsequently, two models are evaluated in the AFC: one one-dimensional and the other three-dimensional with 33 items. Although both are significant in the chi-square test, the three-dimensional model presents a better fit (CFI = 0.908, TLI = 0.901, RMSEA = 0.075, SRMR = 0.051). These results confirm that sarcastic critical humor is best understood from three different dimensions (subtle humor, defensive humor, and covert social criticism), empirically supporting the theoretical model proposed. This finding strengthens the relevance of the inventory, since it allows a complex phenomenon to be evaluated in a specific and structured way.

The fifth objective is to explore the divergent validity based on the correlation with the Multidimensional Scale of Mood in Health Professionals (EMHUPS). A negative and weak Spearman's coefficient (ρ = -0.142) is found, although statistically significant (p = 0.044). The coefficient of determination (r² = 0.02) indicates that only 2% of the variability can be explained between both scales. These results confirm that the IHCD-25 measures a different construct than the EMHUPS and that there is no redundancy between the instruments. The conceptual independence found reinforces the divergent validity of the inventory and its ability to exclusively evaluate sarcastic critical humor.

The sixth objective is to evaluate reliability using the Omega coefficient. A value of .978 is obtained for the total scale and results of .946, .967 and .949 in Subtle Humor, Defensive Humor and Covert Social Criticism, respectively. These values far exceed the recommended minimum of 0.75 and confirm that the IHCD-25 has excellent internal consistency (

Díaz Concepción et al., 2021;

Salvador-Moreno et al., 2021). The high reliability achieved supports the stability of the measurements, which ensures that the inventory can be used in academic and professional contexts with reliable and replicable results.

Finally, the seventh objective is to define cut-off points and percentiles. It is identified that the average scores are 25 in Subtle Humor, 28.7 in Defensive Humor and 26.9 in Covert Social Criticism, while the average total score is 80.6. Students above the 75th percentile display a more pronounced form of sarcastic and critical humor, distinguished by sarcasm, verbal confrontation, and indirect criticism. In terms of dimensions, the high scores in Subtle Humor show the use of indirect comments that society accepts; in Defensive Humor, the tendency to protect one's self-image in the face of criticism; and in Hidden Social Criticism, the ability to question authorities and norms implicitly (Fernández-Poncela, 2024;

Villota et al., 2023). This analysis provides exact normative guidelines that facilitate the interpretation of the results at various levels of expression of the variable.

Overall, the results of this study show that the Sarcastic Critical Humor Inventories (IHCD-25) meet strict standards of validity and reliability. The relevance of this innovative and useful instrument in the field of university is supported by the theoretical and methodological solidity achieved, which allows offering a scientific tool that can be used in subsequent research and interventions focused on understanding and managing the impact of sarcastic humor on the social and academic life of students.

Conclusion

The main purpose of the research was to establish the psychometric characteristics of the Inventory of Sarcastic Critical Humor (IHCD-25) university students in the city of Trujillo. It was determined that the instrument is both valid and reliable in this environment, because it showed acceptable levels of internal consistency and a structure composed of three dimensions, which has 33 items that are properly attached, as well as evidence of content, factorial and divergent validity. Percentile norms were also developed to facilitate their application for the measurement of the variable in the population studied.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Avalos Blas, Catyel Alessandra, Avalos Rubio, Carmen del Pilar Maryory, Blas Cerdan, Dayana Yarle and Vaca Estela, Diana Lizeth Methodology: Avalos Blas, Catyel Alessandra, Avalos Rubio, Carmen del Pilar Maryory, Blas Cerdan, Dayana Yarle and Vaca Estela, Diana Lizeth Formal analysis: Avalos Blas, Cayel Alessandra, Avalos Rubio, Carmen del Pilar Maryory, Blas Cerdan, Dayana Yarle and Vaca Estela, Diana Lizeth Research: Avalos Blas, Catyel Alessandra, Avalos Rubio, Carmen del Pilar Maryory, Blas Cerdan, Dayana Yarle and Vaca Estela, Diana Lizeth Data purification: Avalos Blas, Catyel Alessandra Original drafting: Avalos Blas, Catyel Alessandra, Avalos Rubio, Carmen del Pilar Maryory, Blas Cerdan, Dayana Yarle and Vaca Estela, Diana Lizeth Writing-revision and editing: Avalos Blas, Catyel Alesaandra, Avalos Rubio, Carmen del Pilar Maryory, Blas Cerdan, Dayana Yarle and Vaca Estela, Diana Lizeth Supervision: Paredes Jara, Fernando

Funding

This study did not receive financial support from any source.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was developed following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants gave informed consent prior to becoming part of the research.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the results of this work are available upon reasonable request addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to the students who participated in the study, whose collaboration was fundamental to the realization of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education. 2018. Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Translated by M. Lieve. Washington, DC: Available online: https://www.testingstandards.net/uploads/7/6/6/4/76643089/9780935302745_web.pdf.

- Ato, M., M. López, and A. Benavente. 2013. A classification system of research designs in psychology. Annals of Psychology 29, 3: 1038–1059. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=16728244043.

- Byrne, B. M., R. J. Shavelson, and B. Muthén. 1989. Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin 105, 3: 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Concepción, A., R. Benítez Montalvo, A. del Castillo Serpa, J. Cabrera Gómez, L. Villar Ledo, A. J. Rodríguez Piñeiro, A. Díaz Concepción, R. Benítez Montalvo, A. del Castillo Serpa, J. Cabrera Gómez, L. Villar Ledo, and A. J. Rodríguez Piñeiro. 2021. Formulation of a new concept of operational reliability. Ingeniare. Revista chilena de ingeniería 29, 1: 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynel, M. 2017. The Irony of Irony: Irony Based on Truthfulness. Corpus Pragmatics 1, 1: 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P. J., and U. Lorenzo-Seva. 2014. Exploratory factor analysis of items: Some additional considerations. Annals of Psychology 30, 3: 1170–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P. J., U. Lorenzo-Seva, A. Hernández-Dorado, and J. Muñiz. 2022. Decalogue for the Factor Analysis of the Items of a Test. Psicothema 34, 1: 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, R. W., and H. L. Colston. 2007. Irony in Language and Thought: A Cognitive Science Reader. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Sampieri, R., and C. P. Mendoza Torres. 2018. Research methodology: The quantitative, qualitative and mixed routes. McGrawHill Edication. [Google Scholar]

- Leñero Cirujano, M. 2022. Design and validation of a questionnaire to assess the attitude towards humour in healthcare professionals. Available online: https://docta.ucm.es/entities/publication/b7ce2a57-9a7d-4726-bd40-e85cfb19e0f8.

- Ministry of Education of Peru. 2023. The University in Numbers: General Information [Report]. Lima: Ministry of Education. Retrieved from. Available online: https://repositorio.minedu.gob.pe/bitstream/handle/20.500.12799/9077/La%20Universidad%20en%20Cifras.pdf.

- Ñaupas, H., M. Valdivia, J. Palacios, and H. Romero. 2018. Quantitative-qualitative research methodology and thesis writing, 5th ed. Bogotá: Ediciones of the U: Available online: http://www.biblioteca.cij.gob.mx/Archivos/Materiales_de_consulta/Drogas_de_Abuso/Articles/MetodologiaInvestigacionNaupas.pdf.

- Ortiz Pérez, W. C., and V. V. Yamo Vallejos. 2023. Styles of humor and resilience in Students of a Private University in the district of Pimentel, Chiclayo. Available online: https://repositorio.uss.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12802/11606.

- Ruch, W., and S. Heintz. 2013. Humour styles, personality and psychological well-being: What's humour got to do with it? European Journal of Humour Research 1, 4: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Moreno, J. E., M. E. Torrens-Pérez, V. Vega-Falcón, D. R. Noroña-Salcedo, J. E. Salvador-Moreno, M. E. Torrens-Pérez, V. Vega-Falcón, and D. R. Noroña Salcedo. 2021. Design and validation of an instrument for the insertion of the emotional salary in the face of COVID-19. CHALLENGES. Journal of Administration Sciences and Economics 11, 21: 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwendri, R. A., and R. Manggalani. 2025. The Influence of Sarcasm on Communication Misunderstandings in University Students. Journal of Communication 3, 1. Available online: https://ejournal.stiab-jinarakkhita.ac.id/index.php/jocrss/article/view/216/120. [CrossRef]

- Villota, M., P. Ferroni, C. Urbano, and L. F. R. Rueda. 2023. Is it just a joke? The uses of hostile humor in school and its relationship with bullying. Psychological Tempus 6, 2: Article 2. Available online: https://revistasum.umanizales.edu.co/ojs/index.php/tempuspsi/article/view/4819/7538.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).