Background

Fish consumption remains one of the key cornerstones of global nutrition and food security. Worldwide apparent per capita fish consumption has increased significantly since the early 1960s, rising from an estimated 9.1 kg/year in 1961 to about 20.7 kg/year in 2022 (Sampson, 2024). Approximately 15% of global animal protein comes from fish and other aquatic foods, representing about 6% of the total protein consumed globally (Sampson, 2024). Besides proteins, fish products are excellent sources of omega-3 fatty acids, essential for supporting brain and cardiovascular health. The growth in fish consumption is evidenced by increased global aquaculture production, with 94.4 million tons of aquatic animals in 2022 (Sampson, 2024). The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) projections suggest increased production to about 205 million tons by 2032 (Sampson, 2024). To put it in context, the aquaculture industry is not just a source of animal protein for humans and animals but also supported approximately 61.8 million workers and hundreds of millions of family members in 2022 (Sampson, 2024).

However, these advances coincide with an emerging animal health and food-safety concern: plastic pollution, and in particular microplastic (MP) contamination (Cholewińska et al., 2022; Li et al., 2024). Plastic materials have become ubiquitous in modern daily life, from bottles to plastic bags, and they fragment into tiny particles, which are considered MPs if their size is <5 mm (US Department of Commerce, 2024). MPs are present in rivers, lakes, and oceans, carried by urban runoff through improper waste disposal, wastewater, and even atmospheric transport (Kurtela and Antolović, 2019). Wash off plastic bottles and plastics on beaches and coastal areas are now a common phenomenon across the world. MPs have also been detected in bottled and piped municipal water (Ramaremisa et al., 2024). It is therefore no surprise that MPs have reported in human and animal tissues. Fish are no exception. Fish readily ingest microplastics through their gills, digestive tracts, or from contaminated fish food (Dalu et al., 2024; Wu et al., 2020). MPs can carry adsorbed toxins and additives as well as promote the growth of disease-causing microbes, raising concerns about new hazards in the food chain (Sheridan et al., 2022).

In farmed aquaculture systems the risk of MPs is an emerging but concerning phenomenon (Cholewińska et al., 2022; Dalu et al., 2024; Sheridan et al., 2022). Many fish farms are situated in ponds or lakes that draw on water inflows contaminated by plastic waste. For example, in Bangladesh, a major aquaculture producer, water and sediment inflows from rivers, canals, and streams has been shown to transport vast amounts of plastic debris and MPs into fish ponds (Hossain et al., 2023). Such scenarios are compounded by MPs originating from plastics in nets, cages, and gear that can degrade and release plastic waste into the water (Sharma et al., 2024). Other sources of MPs in fish ponds include commercial fishmeal and feeds (Muhib and Rahman, 2023; Siddique et al., 2025).

Despite this emerging challenge of MPs in aquaculture, their impacts on fish health and human consumers are not fully understood. Current evidence is mixed: studies confirm ubiquitous microplastic contamination in farmed fish and aquatic systems but the ecological and fish health consequences remain debated (Cholewińska et al., 2025, 2022; Hossain et al., 2023; Muhib and Rahman, 2023, 2023; Siddique et al., 2025). This critical narrative review examines the current and hypothetical state of knowledge on aquaculture in the context of plastic pollution and their implications on fish diseases. The review highlights how MPs threaten fish health, aquaculture sustainability, and ultimately global food security.

Microplastics in Aquatic Environments

Plastics enter aquatic ecosystems from a myriad of sources. MPs may arise as primary particles such as microbeads the manufacturing industries, and as secondary fragments from the breakdown of larger plastic debris (Hossain et al., 2023; Muhib and Rahman, 2023; Sharma et al., 2024). Global plastic production has skyrocketed to 414 million tons in 2023 compared to 339 million tons in 2018, representing a 22% growth (Plastics Europe, 2024). In water bodies and drainages, wave action, UV light and mechanical abrasion gradually fragment plastics into micro- and nanoplastics (Jiang et al., 2023). Because they are buoyant and durable, MPs persist in water bodies for years, floating or sinking into sediments. Once in the environment, microplastics are widely dispersed. So far, research shows their presence in oceans, rivers, canals, lakes, and streams (Dalu et al., 2024; Hossain et al., 2023; Muñiz and Rahman, 2025). Basically, wherever humans are living, the problem of plastic pollution is never far, especially in low-income countries where disposal of plastic waste is poorly regulated (Kamara et al., 2021). Water run-offs from waste landfills are also a common source of MPs. Atmospheric transport also carries MPs, depositing them into water bodies far from their source (Bao et al., 2023; Bhat et al., 2023; Österlund et al., 2023). It is currently estimated that approximately 80% of MPs in aquatic environments originate from land-based activities (Pothiraj et al., 2023). Even wastewater treatment plants do not remove all MPs, resulting in continued discharges into rivers (Sadia et al., 2022). Consequently, all aquatic animals get exposed to MPs. These particles have been reported in zooplankton, mussels, fish, birds, and even deep-sea species (Muñiz and Rahman, 2025; Wu et al., 2020).

Microplastic Contamination in Aquaculture Systems

Surveys of fish farms around the world have detected microplastics in water, sediment, and fish. For instance, a recent study examined five types of freshwater fish ponds in Bangladesh (from rural homestead ponds to industrial-adjacent ponds) and found 3 - 137 particles/kg in sediments and 17–100 particles/L in pond water (Hossain et al., 2023). The highest pollution was in ponds near industrial zones, but even rural ponds contained substantial microplastics. Common polymers (polypropylene, polyethylene) were identified (Hossain et al., 2023). Similar findings have been reported in marine aquaculture systems (Kurtela and Antolović, 2019; Muñiz and Rahman, 2025). It appears that fish meal and fish feeds are the major sources of contamination. Analyses of commercial fishmeal and pelleted feeds have consistently found microplastics (fibers and fragments of nylon and polyethylene) (Muhib and Rahman, 2023; Siddique et al., 2025). A global screening of 26 fishmeal products (11 countries, 5 continents) detected MPs in nearly every sample (Gündoğdu et al., 2021). Experimental feeding of carp with those feeds confirmed the plastics transferred into fish tissues (Oh et al., 2023). Even alternative feeds (soy, plant oils, insects) have been shown to contain anthropogenic fibers. Aquaculture infrastructure itself generates plastics. Over time, old pond liners, nets, floats, and containers break down. Studies note abandoned or poorly managed farms leave plastic debris (ghost nets, degraded liners) that shatter into microplastics (Cholewińska et al., 2022; Sharma et al., 2024).

Microplastics in the Tissues of Farmed Fish and Seafood

Unsurprisingly, MPs have been found in farmed fish themselves. Surveys of farmed salmon, tilapia, carp, shrimp, and other aquaculture species frequently detect plastic particles in the gastrointestinal tract and other tissues (Matias et al., 2023; Muhib and Rahman, 2024; Oh et al., 2023; Roch et al., 2020). Field studies of market-bought farmed fish have reported plastics (often fibers) in the gut contents (Wu et al., 2020). MP burdens can differ markedly between wild and farmed fish of the same species, reflecting differences in habitat and diet (Sultana et al., 2023). The types of plastics found in farmed fish often match local pollution. Fibers (from textiles) and fragments of polyethylene or polypropylene are common in both pond and cage fish (Hossain et al., 2023). The human dietary exposure from a serving of fish is generally estimated to be in the range of a few to a few dozen microplastic particles, depending on the species and region (Milne et al., 2024).

Effects of MPs on Fish Health

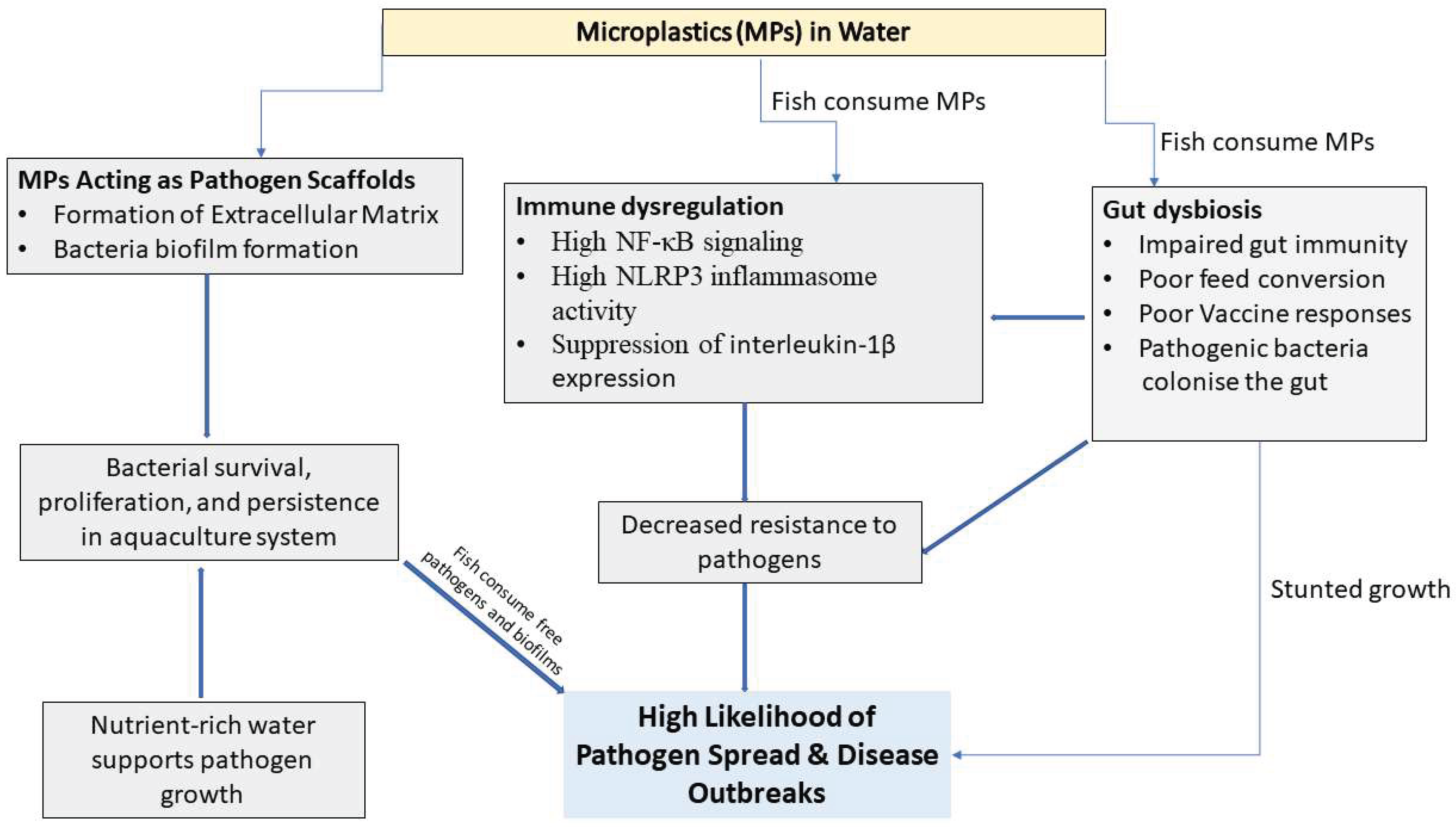

Despite rapid advances in aquaculture, the risks posed by MPs remain underexplored compared to other stressors such as oxygen fluctuations or eutrophication. Some laboratory trials show that high levels of microplastic ingestion can cause tissue inflammation, oxidative stress or reduce growth rates in fish (Pei et al., 2022). However, these studies often use concentrations higher than those typically found in the environment. In commercial farms, the health effects on fish are less obvious but concerns remain: microplastics could carry pathogenic bacteria or toxins to the fish, or physically clog digestive systems (

Figure 1):

Disruption of immune responses in fish: Evidence so far suggests that MPs actively dysregulate fish immunity. In vitro and in vivo studies have found that MP exposure triggers inflammatory and apoptotic pathways in mucosal tissues while dampening systemic immunity. For example, polyethylene MPs in carp gills provoked oxidative stress with upregulation of NF-κB signaling and NLRP3 inflammasome activity, elevating pro-inflammatory cytokines and reducing anti-inflammatory IL-4/IL-10 (Cao et al., 2023). At the same time, polystyrene particles were shown to suppress key innate immune pathways such as interleukin-1β expression, resulting in impaired resistance to bacterial pathogens (Yang et al., 2024). By dampening immune responses as a result of reduced lymphoid cell viability and suppression of immune gene expression, MPs can make fish susceptible to viral pathogens (Yan et al., 2024). These findings are supported by Seeley et al. (2022), who observed that rainbow trout co-exposed to microfibers and a salmonid virus suffered significantly higher mortality, viral burden, and gill inflammation than virus-only controls (Seeley et al., 2023).

Alteration of the gut microbiome and metabolome: MPs profoundly disturb the gut microbiota and mucosal health. In controlled studies, small MPs in fish diets altered community structure and induced intestinal inflammation. For example, adult zebrafish exposed to polystyrene beads (0.5–50 μm) for two weeks showed a classic dysbiosis signature characterised by decreases in Bacteroidetes/Proteobacteria, increases in Firmicutes, overproduction of gut mucus, and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β and IFN) in the intestine (Jin et al., 2018). In Nile tilapia juveniles, a 30-day mixed-polymer MP diet elicited significant changes in liver and intestinal expression of genes linked to inflammation and apoptosis (König Kardgar et al., 2024). Mechanistically, MPs can mechanically irritate the epithelium, alter short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, and increase mucosal permeability, allowing opportunistic bacteria to bloom (Cholewińska et al., 2022; Jin et al., 2018). Broadly, MP-induced dysbiosis can reduce feed-conversion efficiency and heighten baseline inflammation, potentially undermining growth and vaccine responses.

Increased risk of pathogen persistence and disease outbreaks: MPs serve as vectors and reservoirs for diverse aquatic pathogens. Surveys of the “plastisphere” find that MPs tend to harbour a greater diversity of microbes than the surrounding water, including many aquaculture pathogens (Cholewińska et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2025; Jiang et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024; Viršek et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2023). For instance, Cholewińska et al. (2022) report that over 30 potential pathogen or opportunist taxa colonize MPs, with strong representation of fish-pathogenic Vibrio species (e.g. V. parahaemolyticus, V. anguillarum, V. harveyi) and Tenacibaculum sp. Critically, Aeromonas salmonicida, the causative agent of fish furunculosis, has been isolated directly from marine plastic debris (Viršek et al., 2017). Once attached, pathogens benefit from the protective biofilm matrix on MPs, which shields them from UV and grazers and concentrates nutrients and co-contaminants that may induce virulence (Jiang et al., 2023; Sheridan et al., 2022). In nutrient-dense aquaculture waters, the impact of MPs on bacterial pathogen growth is profound (Cholewińska et al., 2022). Floating or suspended, contaminated plastics can transport pathogens across cages or into ponds. In aquaculture systems, this means a high-density pathogen load may be delivered to fish surfaces or gills.

Discussion

This review has explored the emerging challenge of MP contamination in aquaculture and its implications for fish health, disease susceptibility, and ultimately food security. While aquaculture has become indispensable for meeting global nutritional needs, supplying more than half of the fish consumed worldwide, it now faces the dual burden of sustaining production under mounting environmental pressures while navigating new risks posed by MPs (Hossain et al., 2023; Sampson, 2024). The synthesis of data has shown that MPs are not only ubiquitous in aquatic systems, sediments, and aquaculture inputs such as feeds, but they are also being incorporated into fish tissues. They appear capable of disrupting immune responses, reshaping the gut microbiome, and facilitating pathogen transmission (Cao et al., 2023; Jin et al., 2018; Viršek et al., 2017).

One of the striking themes in this review is the capacity of MPs to dysregulate fish immune function. Laboratory studies consistently demonstrate that exposure to MPs can provoke oxidative stress, cytokine imbalance, and apoptosis in lymphoid tissues (Cao et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2024). These immune disruptions are not simply toxicological curiosities; they could translate into lower resilience to novel and endemic fish diseases (Seeley et al., 2023). Hypothetically, if MPs act as chronic immunosuppressants, they may reduce the efficacy of vaccines that aquaculture heavily relies upon.

The gut ecosystem of fish, like that of mammals, is pivotal to nutrient absorption and immune homeostasis. Data reviewed in this article indicate that MPs can induce dysbiosis, shifting microbiota balance toward pro-inflammatory states and reducing beneficial short-chain fatty acid production (Pei et al., 2022). Such changes are not trivial: they could reduce feed conversion ratios, stunt growth, and elevate baseline inflammation. If compounded by other aquaculture stressors such as overcrowding and fluctuating oxygen levels, the presence of MPs in feeds or pond water may generate a “perfect storm” where growth performance declines while susceptibility to pathogens increases (Seeley et al., 2023). Although much of this evidence comes from short-term laboratory exposures, the consistency across fish species supports the hypothesis that MP-mediated dysbiosis could emerge as a hidden cost of modern aquaculture intensification (Jin et al., 2018; Pei et al., 2022).

The evidence reviewed also positions MPs as potential reservoirs and vehicles for pathogens, creating a novel ecological niche, the “plastisphere”, that shelters bacteria and viruses from environmental pressures (Cholewińska et al., 2022; Sheridan et al., 2022). Vibrio sp., Aeromonas sp., and Tenacibaculum sp., all notorious in aquaculture, are enriched on MPs compared to the surrounding water (Cholewińska et al., 2025, 2022; Viršek et al., 2017). This raises the possibility that MPs circulating within ponds and cages amplify pathogen pressure, accelerating outbreak dynamics. A hypothetical but plausible scenario is that MPs, laden with biofilm-bound pathogens, facilitate simultaneous transmission to large numbers of fish in high-density cages, thereby overwhelming even robust immune defenses. Actually, biofilm-covered MPs are likely to be consumed by fish than plain plastics. This function of MPs as mobile pathogen hubs suggests that their risks are ecological as well as toxicological.

Taken together, the findings point toward MPs as an underappreciated but multifaceted stressor on aquaculture. Beyond direct effects on fish, there are potential downstream consequences for human consumers, both in terms of microplastic ingestion and the stability of fish supply. If fish health declines due to immune suppression or heightened disease outbreaks, production costs could rise, threatening the affordability and accessibility of fish protein in low- and middle-income countries where it is most vital. Furthermore, the persistence and pervasiveness of MPs mean that mitigation will require systemic changes in waste management, feed production, and aquaculture infrastructure design.

Conclusion

MPs simultaneously threaten fish health, compromise aquaculture sustainability, and create novel pathways for pathogen emergence. While much of the evidence remains preliminary, the convergence of mechanistic insights, field detections, and ecological plausibility argues for urgent action. Addressing MPs in aquaculture should not be relegated to a niche research agenda; it must become central to discussions on food security, climate resilience, and planetary health. As aquaculture is projected to nearly double in production by 2032, ignoring the role of MPs risks undermining both economic gains and public health. A decisive, interdisciplinary response integrating environmental science, aquaculture technology, and policy innovation will be crucial to safeguard the promise of fish as a sustainable cornerstone of global diets.

Declaration

Author Declares No Conflict of Interest.

References

- Bao, M., Xiang, X., Huang, J., Kong, L., Wu, J., Cheng, S., 2023. Microplastics in the Atmosphere and Water Bodies of Coastal Agglomerations: A Mini-Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.A., Gedik, K., Gaga, E.O., 2023. Atmospheric micro (nano) plastics: future growing concerns for human health. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health 16, 233–262. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J., Xu, R., Wang, F., Geng, Y., Xu, T., Zhu, M., Lv, H., Xu, S., Guo, M., 2023. Polyethylene microplastics trigger cell apoptosis and inflammation via inducing oxidative stress and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in carp gills. Fish & Shellfish Immunology 132, 108470. [CrossRef]

- Cholewińska, P., Moniuszko, H., Wojnarowski, K., Pokorny, P., Szeligowska, N., Dobicki, W., Polechoński, R., Górniak, W., 2022. The occurrence of microplastics and the formation of biofilms by pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria as threats in aquaculture. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, 8137. [CrossRef]

- Cholewińska, P., Wojnarowski, K., Szeligowska, N., Pokorny, P., Hussein, W., Hasegawa, Y., Dobicki, W., Palić, D., 2025. Presence of microplastic particles increased abundance of pathogens and antimicrobial resistance genes in microbial communities from the Oder river water and sediment. Scientific Reports 15, 16338. [CrossRef]

- Dalu, T., Themba, S.T., Dondofema, F., Wu, N., Munyai, L.F., 2024. Assessing microplastic abundances in freshwater fishes in a subtropical African reservoir. Discover Sustainability 5, 360. [CrossRef]

- Gündoğdu, S., Eroldoğan, O.T., Evliyaoğlu, E., Turchini, G.M., Wu, X.G., 2021. Fish out, plastic in: Global pattern of plastics in commercial fishmeal. Aquaculture 534, 736316. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W., Li, D., Chen, B., Li, J., Li, Z., Cao, X., Qiu, H., Zhao, L., 2025. Microbial colonization on four types of microplastics to form biofilm differentially affecting organic contaminant biodegradation. Chemical Engineering Journal 503, 158060. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.B., Banik, P., Nur, A.-A., Choudhury, T.R., Liba, S.I., Albeshr, M.F., Yu, J., Arai, T., 2023. Microplastics in fish culture ponds: abundance, characterization, and contamination risk assessment. Frontiers in Environmental Science Volume 11-2023. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C., Almuhtaram, H., McKie, M.J., Andrews, R.C., 2023. Assessment of Biofilm Growth on Microplastics in Freshwaters Using a Passive Flow-Through System. Toxics 11. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y., Xia, J., Pan, Z., Yang, J., Wang, W., Fu, Z., 2018. Polystyrene microplastics induce microbiota dysbiosis and inflammation in the gut of adult zebrafish. Environmental Pollution 235, 322–329. [CrossRef]

- Kamara, A.B., Sawaneh, I.A., Tarawally, M., 2021. The adverse effects of plastics pollution on the environment, health of animals and human beings. environment 6.

- König Kardgar, A., Doyle, D., Warwas, N., Hjelleset, T., Sundh, H., Carney Almroth, B., 2024. Microplastics in aquaculture - Potential impacts on inflammatory processes in Nile tilapia. Heliyon 10. [CrossRef]

- Kurtela, A., Antolović, N., 2019. The problem of plastic waste and microplastics in the seas and oceans: impact on marine organisms. Croatian Journal of Fisheries 77, 51–56. [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Zeng, J., Zheng, N., Ge, C., Li, Y., Yao, H., 2024. Polyvinyl chloride microplastics in the aquatic environment enrich potential pathogenic bacteria and spread antibiotic resistance genes in the fish gut. Journal of Hazardous Materials 475, 134817. [CrossRef]

- Matias, R.S., Gomes, S., Barboza, L.G.A., Salazar-Gutierrez, D., Guilhermino, L., Valente, L.M.P., 2023. Microplastics in water, feed and tissues of European seabass reared in a recirculation aquaculture system (RAS). Chemosphere 335, 139055. [CrossRef]

- Milne, M.H., De Frond, H., Rochman, C.M., Mallos, N.J., Leonard, G.H., Baechler, B.R., 2024. Exposure of U.S. adults to microplastics from commonly-consumed proteins. Environmental Pollution 343, 123233. [CrossRef]

- Muhib, Md.I., Rahman, Md.M., 2024. How do fish consume microplastics? An experimental study on accumulation pattern using Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Environmental Science and Pollution Research 31, 39303–39317. [CrossRef]

- Muhib, M.I., Rahman, M.M., 2023. Microplastics contamination in fish feeds: Characterization and potential exposure risk assessment for cultivated fish of Bangladesh. Heliyon 9, e19789. [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, R., Rahman, M.S., 2025. Microplastics in coastal and marine environments: A critical issue of plastic pollution on marine organisms, seafood contaminations, and human health implications. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 18, 100663. [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.-K., Lee, J., Lee, S.Y., Kim, T.K., Chung, D., Seo, J., 2023. Microplastic Distribution and Characteristics in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio) from Han River, South Korea. Water 15. [CrossRef]

- Österlund, H., Blecken, G., Lange, K., Marsalek, J., Gopinath, K., Viklander, M., 2023. Microplastics in urban catchments: Review of sources, pathways, and entry into stormwater. Science of The Total Environment 858, 159781. [CrossRef]

- Pei, X., Heng, X., Chu, W., 2022. Polystyrene nano/microplastics induce microbiota dysbiosis, oxidative damage, and innate immune disruption in zebrafish. Microbial pathogenesis 163, 105387. [CrossRef]

- Plastics Europe, 2024. Plastics - the fast Facts 2024.

- Pothiraj, C., Amutha Gokul, T., Ramesh Kumar, K., Ramasubramanian, A., Palanichamy, A., Venkatachalam, K., Pastorino, P., Barcelò, D., Balaji, P., Faggio, C., 2023. Vulnerability of microplastics on marine environment: A review. Ecological Indicators 155, 111058. [CrossRef]

- Ramaremisa, G., Tutu, H., Saad, D., 2024. Detection and characterisation of microplastics in tap water from Gauteng, South Africa. Chemosphere 356, 141903. [CrossRef]

- Roch, S., Friedrich, C., Brinker, A., 2020. Uptake routes of microplastics in fishes: practical and theoretical approaches to test existing theories. Scientific Reports 10, 3896. [CrossRef]

- Sadia, M., Mahmood, A., Ibrahim, M., Irshad, M.K., Quddusi, A.H.A., Bokhari, A., Mubashir, M., Chuah, L.F., Show, P.L., 2022. Microplastics pollution from wastewater treatment plants: A critical review on challenges, detection, sustainable removal techniques and circular economy. Environmental Technology & Innovation 28, 102946. [CrossRef]

- Sampson, S., 2024. FAO Report: Global fisheries and aquaculture production reaches a new record high [WWW Document]. Newsroom. URL https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/fao-report-global-fisheries-and-aquaculture-production-reaches-a-new-record-high/en (accessed 10.4.25).

- Seeley, M.E., Hale, R.C., Zwollo, P., Vogelbein, W., Verry, G., Wargo, A.R., 2023. Microplastics exacerbate virus-mediated mortality in fish. Science of The Total Environment 866, 161191. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D., Dhanker, R., Bhawna, Tomar, A., Raza, S., Sharma, A., 2024. Fishing Gears and Nets as a Source of Microplastic, in: Shahnawaz, Mohd., Adetunji, C.O., Dar, M.A., Zhu, D. (Eds.), Microplastic Pollution. Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, pp. 127–140. [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, E.A., Fonvielle, J.A., Cottingham, S., Zhang, Y., Dittmar, T., Aldridge, D.C., Tanentzap, A.J., 2022. Plastic pollution fosters more microbial growth in lakes than natural organic matter. Nature Communications 13, 4175. [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.A.M., Tahsin, T., Das, K., 2025. Microplastic contamination in commercial tilapia feeds: lessons from a developing country. Aquaculture International 33, 190. [CrossRef]

- Sultana, N., Tista, R.R., Islam, M.S., Begum, M., Islam, S., Naser, M.N., 2023. Microplastics in freshwater wild and farmed fish species of Bangladesh. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 30, 72009–72025. [CrossRef]

- US Department of Commerce, N.O. and A.A., 2024. What are microplastics? [WWW Document]. URL https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/microplastics.html (accessed 10.4.25).

- Viršek, M.K., Lovšin, M.N., Koren, Š., Kržan, A., Peterlin, M., 2017. Microplastics as a vector for the transport of the bacterial fish pathogen species Aeromonas salmonicida. Marine Pollution Bulletin 125, 301–309. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Lai, M., Zhang, Y., Li, J., Zhou, H., Jiang, R., Zhang, C., 2020. Microplastics in the digestive tracts of commercial fish from the marine ranching in east China sea, China. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2, 100066. [CrossRef]

- Yan, L., Yao, X., Wang, P., Zhao, C., Zhang, B., Qiu, L., 2024. Effect of polypropylene microplastics on virus resistance in spotted sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus). Environmental Pollution 342, 123054. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Ju, J., Wang, Y., Zhu, Z., Lu, W., Zhang, Y., 2024. Micro-and nano-plastics induce kidney damage and suppression of innate immune function in zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae. Science of The Total Environment 931, 172952. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., Zhou, Z.-C., Shuai, X., Lin, Z., Liu, Z., Zhou, J., Lin, Y., Zeng, G., Ge, Z., Chen, H., 2023. Microplastics exacerbate co-occurrence and horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes. Journal of Hazardous Materials 451, 131130. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).