1. Introduction

Forest therapy and forest bathing (

Shinrin-yoku) are structured practices of mindful immersion in woodland environments that have gained international attention as preventive and complementary health strategies. They were established officially in 1982 by Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, to promote public health in response to rising levels of stress, anxiety, and illnesses linked to urbanization and the phenomenon of

karoshi (death from overwork) [

1]. Forest therapy and forest bathing are now the subject of extensive research globally, including in European countries, with a growing body of scientific literature linking forest exposure to effective psychological and physiological benefits [

2,

3]. Reported effects include reductions in stress and anxiety, enhanced affective well-being, and improvements in cardiovascular, immune, and respiratory functions [

4,

5,

6].

Mechanisms appear to be both psychological and biological. Research suggests that forest settings facilitate attentional restoration and emotion regulation, while exposure to natural volatiles such as plant-emitted monoterpenes may exert direct anxiolytic effects [

7], which was previously confirmed, along with significant effects on the immune and endocrine systems and cardiovascular health, with experiments in both controlled and forest environments [

5]. In particular, clinical studies highlighted that forest immersion can provide supportive benefits for chronic conditions such as pain, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and fibromyalgia [

8,

9,

10].

Forest bathing is a personal health practice devoid of clinical aims, whose degree of structuring can vary from free forest walking to mindful forest immersion sometimes along signed forest trails, till experiences guided by non-clinical personnel. Recently, research in the field of mental health suggested that nature-based walking interventions may be used to relieve at least one’s negative mood, stress, and anxiety; to enhance treatment efficacy, however, they should be combined with formal modes of psychotherapy [

11], which can be best provided by clinical psychotherapists. This leads to forest therapy, as a therapeutic intervention guided by clinical professionals, which, to be substantiated, requires an accurate identification of the scope along with the significance and size of the effects, the latter in turn conditioned on the characteristics of the intervention (environment and activities) and the personal traits including gender, age and possible active illness [

12].

Although some reviews caution against overstating its efficacy, forest therapy is increasingly recognized as a low-risk, accessible intervention that complements conventional care and resonates with the One Health framework linking human well-being and ecosystem health [

13]. These insights highlight its relevance to contemporary health research and practice.

The question whether therapist-guided experiences actually provide also an added benefit to participants’ mood and psychological symptoms compared to self-guided forest immersion experiences remains partially unanswered [

14]. In other words, does therapist-guided (TG) forest therapy really convey additional benefits to short-term mental health compared to self-guided (SG) forest bathing? To the best of the authors’ knowledge, all studies addressing this question focused on university or graduate students on campuses located in Far Eastern countries.

With 37 undergraduate students randomly assigned to a guided forest therapy program or self-guided forest immersion experience in a university campus in South Korea, based on free personal essays, Kim and Shin found that the self-guided experience promoted self-reflection, while guided forest therapy delivered positive emotional changes and promoted social bonds [

15]. Later, the same authors experimented with a randomized 3 × 3 crossover study, where 23 university students were randomly assigned to: a self-guided forest therapy program, a guided forest-therapy program, or routine activities. They found that self-guided and guided forest-therapy programs significantly improved participants’ negative emotions and natural connectedness compared to routine activities; however, for self-esteem, only a guided forest therapy program delivered a significant improvement compared to daily routine activities [

16].

In a similar study, Shin et al. found that self-guided and guided forest-healing programs significantly improved subjects’ mood states and anxiety symptoms compared to routine activities. Participating in a forest healing program with guides and participating in a self-guided forest healing program both provided psychological benefits for subjects, showing that self-guided programs can be effectively combined with forest healing [

17].

In a recent large-scale experiment involving approximately 250 university students, randomly assigned to guided forest therapy or self-guided forest walking on a university campus in China, Guo et al. found no significant differences in effectiveness based on self-reported psychological and physiological measures (blood pressure and heart rate) [

18].

This study aimed to assess the short-term effectiveness for mental health of therapist-guided forest therapy activities compared to the same activities performed through partially self-guided experiences, where the only difference was the verbal communication of the instructions (TG sessions) or the reading and interpretation of written signs placed along the forest trails (SG sessions). Besides this original experimental design, novelty also arises from the evaluation, for the first time, across multiple sites and multiple adult age groups.

Moreover, this study aimed at providing a rough and preliminary assessment of the absolute and comparative economic value of TG and SG programs, based on the existing evidence of the persistence of beneficial effects and using a widely adopted methodology specifically designed for internal budget allocations within healthcare portfolios [

19].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Design and participants

Experimental sessions were conducted between September 2021 and June 2025 in 8 sites, one of which was located in an urban park. This was part of a broader experimental campaign involving tens of sites across Italy, whose data collected from September 2021 to October 2022 were used in a previous study [

7].

Table 1 shows the geographical, vegetational and weather data of study sites; temperature levels were measured using hand-held thermometers and reported as the average value during the TG and SG sessions, while cloudiness was visually estimated by an expert meteorologist.

Table 2 shows participants data of the TG and SG sessions.

Figure 1 shows the location of the eight sites considered in this study. All geospatial data were referenced to the WGS 84 geographic coordinate system (EPSG:4326). Cartographic representation of the study area and sampling sites was performed using QGIS (version 3.28 ‘Firenze’,

https://qgis.org/).

An overall population of 282 adults, aged between 18 and over 70, took part in the study. For each of the eight sites, two forest immersion sessions were carried out along the same trail and starting no more than 20-minute apart to remove possible systematic biases. For each site, the first group participated in a TG session, led by a psychologist or psychotherapist who verbally communicated the instructions, whereas the second group engaged in a SG session, having to read and interpret the same instructions displayed on signs placed along the path. The SG group was led by an author of this study or a hiking guide, who also marked the end time of the stops at any sign; thus, the only difference compared to the TG sessions consisted in reading and interpreting the instructions written on the signs. Each session lasted in total approximately 3.0±0.3 hours, including the filling of questionnaires before and after the session, while the walks lasted about 2.3 hours. Data were collected immediately before and after each TG or SG session, following a pre-post study without a follow-up period.

Only adults who were able to independently complete a questionnaire written in Italian and explicitly willing to participate in forest therapy sessions after filling their informed consent were included in this study. Exclusion criteria were being underage (< 18 years), having any acute illnesses requiring medications beyond those usually taken daily for chronic diseases conditions, and any major physical or mental health problems incompatible with outdoor walking for a few hours. Each participant was allowed to attend only one session, to prevent any possible carry-over effect.

All participants were treated in accordance with the ethical guidelines for research provided by the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions, and the study was approved by the local ethics committee (CNR Ethics Committee n. 0069654/2021).

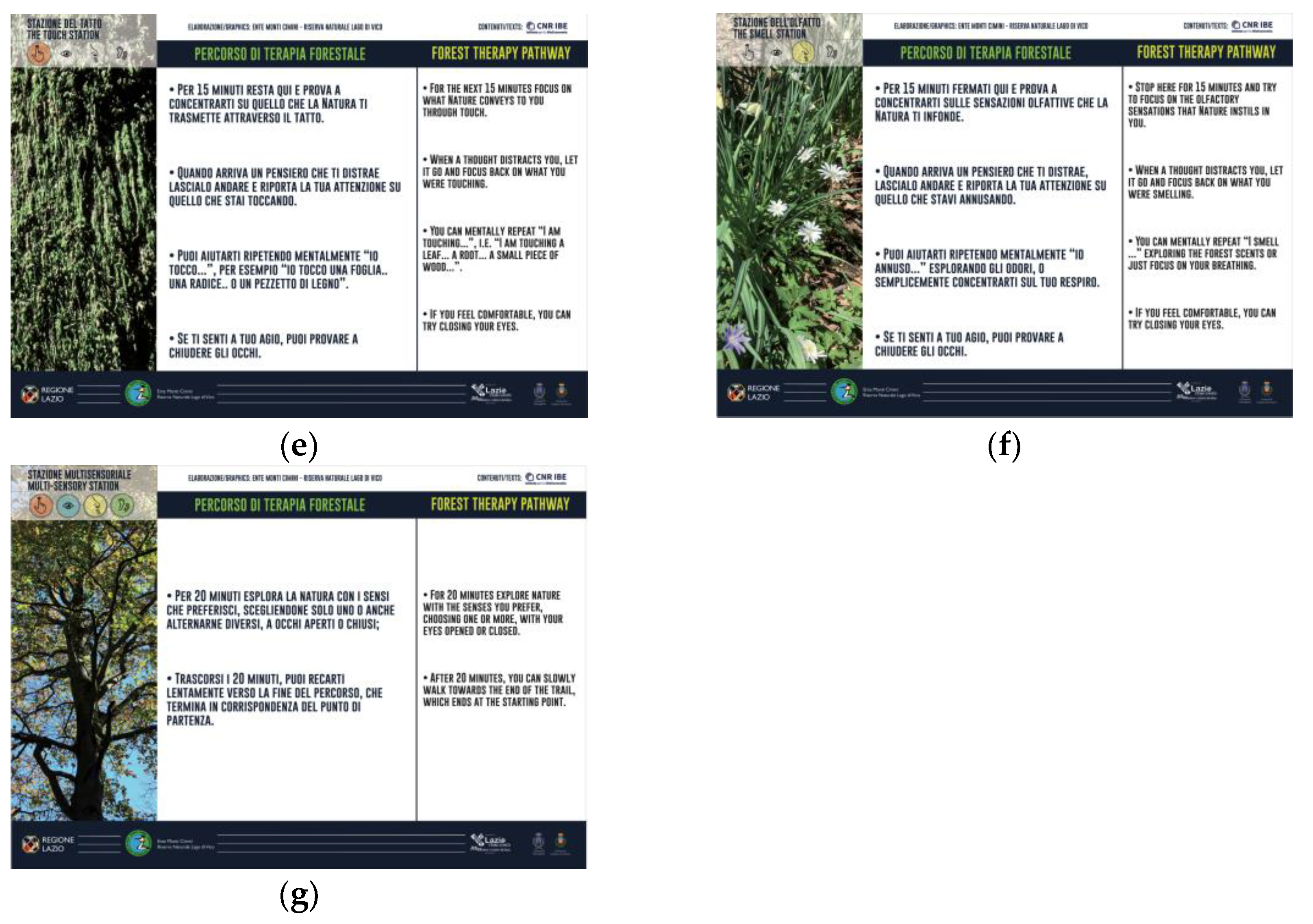

The forest immersion program, both in TG and SG sessions, consisted of simple instructions to the participants to focus their attention on the external environment. The protocol was designed to provide reproducible instructions to all the psychologists or psychotherapists involved, in order to minimize any interference related to the therapists’ personal styles and ensure homogeneous experimental conditions [

7]. The overall duration of each session was approximately 3 hours, including short, slow walks, interspersed with five stops focusing on senses (sight, hearing, touch, smelling, and a final multi-sensorial stop), and a final walk, before filling out the psychometric self-assessment questionnaires after the forest therapy experience. The physical intensity of the sessions was kept low to avoid potential biases due to adrenergic hyperactivation. Each session was conducted in the morning, starting around 10:00 a.m. and ending around 01:00 p.m., local time (corresponding to GMT+2 for all sessions). As shown in

Table 1, the considered forest therapy sessions were performed with fair weather, without rain, and with comfortable temperatures within the range of 18 to 25 °C.

Figure 2 shows representative pictures of the local environments of the 8 sites.

Figure 3 shows the content of the boards displaying the instructions, in Italian and English languages, read by the participants (SG sessions) or verbally communicated by the therapist (TG sessions).

2.2 Outcome measures

All participants reached each forest therapy site autonomously and, upon arrival, they were required to fill in the informed consent form. Then, every participant was presented with an anonymous questionnaire (with a unique ID code), aimed at collecting information about gender, age, and other personal features. Then, they were asked to fill in two psychometric questionnaires, the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaires.

STAI is a validated questionnaire used to measure state and trait non-disorder-specific anxiety, in both healthy and clinical populations [

20]. It consists of a 20-item self-report measure of anxiety, using a 4-point Likert-type scale for each item. It has two scales: state anxiety, i.e., how one feels at a given moment (STAI-S), and trait anxiety, i.e., how one generally feels (STAI-T), both consisting of 20 items. Total scores were calculated by summing up the items in each respective form of anxiety (ranging from 20 to 80), where higher scores reflect greater levels of anxiety.

The POMS is a validated questionnaire consisting of 40 items, each measured with a 5-point Likert scale, related to domains such as tension, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue, confusion and self-esteem [

21]. Both POMS and STAI questionnaires have been widely used in the environmental psychology fields, such as recently with healthy people cohorts [

6,

22], and with patients cohorts [

10,

23], as well as in contexts similar to the one investigated in this study [

17].

STAI-S was chosen as the outcome measure of state anxiety, as it has been often used with clinical and subclinical study populations and can detect subtle changes in anxiety levels, even when there are large differences in baseline scores, as occurs with highly heterogeneous participants in forest therapy sessions, showing varying degrees of vulnerability to anxiety [

24].

The STAI-S and POMS questionnaires were administered immediately before and after each forest therapy session, in order to intercept any short-term effects (changes from baseline) elicited during the sessions. Change-from-baseline STAI-S scores, along with the domain of self-esteem (POMS-esteem) and the total mood disturbance (POMS-TMD), the latter computed as the sum of negative moods (anxiety, depression, anger, fatigue and confusion) subtracted by positive moods (vigor and self-esteem), were assumed as the main outcome measures. The STAI-T questionnaire was administered only at baseline to better characterize the participants based on their trait anxiety, which reflects the stable long-term tendency toward anxiety, and contributed to the homogeneity analysis of groups across different sessions.

2.3 Missing data

To address missing responses on the questionnaires, we used k-nearest neighbors (KNN) imputation, which estimates missing values by referencing the most similar response patterns from other participants [

25,

26]. This approach was selected because it maintains the multivariate relationships among items without imposing distributional assumptions, making it well suited for Likert-type psychological data. Imputation was performed separately within each TG–SG session pair, to avoid potential bias that could arise from pooling heterogeneous populations across different sites or times. The procedure was limited to cases with up to 20% missing responses per participant on a given questionnaire.

Although more advanced approaches such as expectation–maximization [

27] or multiple imputation [

28] are available, our focus was on ensuring complete datasets for descriptive and comparative purposes rather than for parameter estimation.

Calculations were performed in

Python (version 3.13) and implemented in the

KNNImputer routine of the

scikit-learn package [

29]. Responses were rounded to the nearest integer and constrained within the expected Likert ranges (1–4 for STAI items; 0–4 for POMS items). Generative artificial intelligence (ChatGPT 5, OpenAI, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) was used for the purpose of debugging python codes.

2.4 Homogeneity across groups

To evaluate the baseline comparability of the groups, we examined demographic characteristics such as gender and age class using chi-square tests of homogeneity [

30]. In addition to significance testing, we calculated Cramer’s V [

31] as a measure of association, interpreting effect sizes according to Cohen’s [

32] benchmarks (0.10 = small, 0.30 = medium, 0.50 = large). This combined approach provided both statistical and substantive assessments of group equivalence.

Contingency tables were constructed to examine the relationship between group membership and categorical demographic variables (i.e., gender and age class). Chi-square tests of homogeneity were performed using the

scipy.stats module [

33], with Fisher’s exact test automatically applied for 2×2 tables with low expected frequencies. The strength of associations was quantified using Cramer’s V, computed from chi-square statistics. Data wrangling and tabulation were performed with

pandas [

34]. Generative artificial intelligence (ChatGPT 5, OpenAI, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) was used for the purpose of debugging python codes.

Homogeneity was further assessed based on STAI-T, i.e., the baseline anxiety levels, reflecting stable individual differences in anxiety proneness that extend beyond demographic factors such as gender and age. Assessing STAI-T distributions across groups allows evaluation of baseline psychological homogeneity, ensuring that differences between TG and SG interventions were not confounded by underlying trait anxiety [

35]. The use of baseline anxiety, represented by STAI-T, is further supported by the evidence provided by a large-scale study, which found that visiting protected areas improved mental health of initially mentally unhealthy individuals by nearly 2.5 times more than mentally healthy individuals [

36]. STAI-T levels were compared across paired TG-SG sessions in the same way as explained in

Section 2.5, because STAI-T is homogeneous in nature to STAI-S.

2.5 Outcome analysis

The significance of differences in the mean values of the outcomes considered from the responses to the psychometric questionnaires, i.e, STAI-T, STAI-S, POMS-esteem and POMS-TMD, was assessed using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney non-parametric rank test, which does not assume normal distribution and is widely used in psychological science and particularly in forest healing studies [

23]. The effect size of each intervention was assessed using Cohen’s d index, a metric also widely employed in the environmental psychology field [

37]. Cohen’s d index complements p-values by providing meaningful information, especially in studies with limited size samples [

38].

Finally, to examine changes in variability across each psychological domain, we employed the Brown–Forsythe test, a robust alternative to Levene’s test that assesses equality of variances based on deviations from the median, and Welch’s test, which adjusts the degrees of freedom to provide unbiased mean comparisons under heteroscedasticity [

39]. Both tests have been successfully used in psychological science [

40].

The dataset was organized in Microsoft® Excel® for Microsoft 365 MSO (Version 2509, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and all the statistical tests mentioned in this section were developed and performed within the same software environment.

2.6 Economic assessment

To provide a preliminary estimate of the economic value of professional guidance, it was assumed that repeated TG or SG experiences could lead to sustained improvements in emotional functioning. To date, most studies of nature-based interventions have focused on short-term psychological outcomes, with little attention to persistence or economic implications [

14]. Markell and Gladwin found that repeated 4-hour SG sessions, conducted once a week for four weeks, were able to maintain the benefits on positive affect and well-being over the following month [

41]. More recent evidence showed that forest- and nature-based interventions can yield sustained improvements in subjective well-being. Chauvenet and collaborators found that a 12-week nature walking program (about 5 h per week) not only produced a higher increase in the Personal Well-Being Index (PWI) at the end of the intervention compared to a control group, both groups consisting of women only, but also a longer persistence of the effects, with little decline over three months after the end of the intervention and with leftover benefits lasting as much as 12 months, especially when training in team [

42]. The same study found that mentally unhealthy individuals at baseline showed the greatest leftover benefit 3 months after the program.

Based on the available evidence, the following assumption was made: average per-person changes in STAI-S, POMS-esteem and POMS-TMD, derived from a suitable program consisting in roughly 25 sessions per year, i.e., once a week for four consecutive weeks, followed by a 4-week break, were considered to translate into equivalent long-term changes in the respective domains, i.e., to the permanent stabilization of the domains considered on new levels. Then, projected changes in mental health domains were converted into gains in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and further into economic value.

Generative artificial intelligence (ChatGPT 5, OpenAI, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) was used for the purpose of debugging python codes and the method proceeded as follows.

2.6.1. Standardization of change

For each outcome j (either STAI-S, POMS-TMD or POMS-EST), the standardized mean change was computed using Equation (1):

where Δj is the difference in the mean between post intervention and baseline and SD

baseline,j is the standard deviation of the outcome j at baseline. For STAI-S and POMS-TMD, where reductions indicate improvement, the sign was inverted so that positive zj always indicated beneficial change. SD

baseline,j was calculated separately for each intervention arm and session, ensuring that standardization reflected the variability inherent to each specific group. This approach aligns with the psychometric tradition of expressing meaningful change in units of baseline variability [

43].

2.6.2. Mapping to QALY gain

A half–standard deviation (0.5SD) improvement in mental health was associated with an utility gain of approximately +0.07 on the EQ-5D scale, a short generic patient-rated questionnaire for subjectively describing and valuing health-related quality of life [

44]. Accordingly, each standardized change was scaled as shown in Equation (2):

where U

j is the annualized QALY gain associated with outcome j. The inclusion of esteem-related affect as an outcome domain is consistent with recent EQ-5D research demonstrating that self-confidence is a relevant health attribute, conceptually overlapping with quality-of-life valuation and increasingly tested as a bolt-on dimension in patient studies [

45,

46].

2.6.3. Accounting for statistical significance and inclusion

Each domain was weighted by a binary flag f

j (1 if the change was statistically significant or explicitly included, 0 otherwise), according to Equation (3):

In particular, with reference to the method explained in

Section 2.5, f

j was set to 0 for outcomes showing non-significant changes, preventing non-significant outcomes from contributing spuriously to the economic value.

2.6.4. Multivariate combination

Because STAI-S, POMS-TMD and POMS-EST are correlated, as POMS-TMD subsumes anxiety and esteem dimensions [

21,

47], a multivariate adjustment was applied. The three standardized scores were combined using a Mahalanobis-type distance, as per Equation (4):

where z=(f

STAI-Sz

STAI-S, f

POMS-TMDz

POMS-TMD, f

POMS-esteemz

POMS-esteem) and Σ is the correlation matrix of the observed changes. To reduce the influence of sampling noise in small groups while avoiding spurious associations across heterogeneous populations, correlations were pooled across matched TG and SG sessions conducted at the same site and period (e.g., S1_TG with S1_SG), but not across different sites or seasons. This ensures that the covariance structure reflects the shared context of each study site while preserving ecological validity.

The overall annual QALY gain was then given by Equation (5):

2.6.5. Monetization

The projected QALY gains were monetized using commonly adopted Italian cost-effectiveness thresholds λ (€20,000–€50,000 per QALY) [

48], as per Equation (6):

The analytic approach described above, in particular in

Section 2.6.2 and

Section 2.6.5, is consistent with recent evidence showing that changes in subjective well-being indices following nature-based interventions can be validly translated into QALY gains and monetized values. In large-scale Australian studies, improvements in PWI from a walking-in-nature therapy program were mapped to QALY changes and valued in monetary terms, confirming both the feasibility and policy relevance of such health-economic translation [

19,

42].

2.6.6. Uncertainty analysis

Uncertainty was quantified by nonparametric bootstrapping with 2000 replicates [

49]. Resampling was conducted within each session file independently, so that the distribution of changes and correlations was preserved separately for each TG or SG group. For each replicate, U

total and its monetized value were recalculated, producing percentile-based 95% confidence intervals. In addition, cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) were derived, reporting the probability that Value>0 across conventional willingness-to-pay thresholds [

50].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Data imputation

Out of a total of 282 records, and following data imputation, the number of records available for further analysis was as follows: STAI-T, 274 (97.2%); STAI-S before sessions, 260 (92.2%); STAI-S after sessions, 273 (96.8%); POMS-TMD and POMS-esteem before sessions: 274 (97.2%); POMS-TMD and POMS-esteem after sessions: 274 (97.2%). No paired TG-SG sessions retained less than 85% of original records in any domain.

3.2. Pairwise group homogeneity

Table 3 shows the level of pairwise group homogeneity, assessed based on gender, age, class and STAI-T of each pair of TG and SG groups. Full homogeneity (H) of groups was associated with p>0.05 and effect size (Cramer’s V or Cohen’s d) < 0.5 for all variables; small imbalance (SI) of groups was associated with the case of p≤0.05 and effect size <0.5, or p>0.05 and effect size ≥0.5 for at least one variable; non homogeneity (NH) was associated with other cases.

Groups in sessions S1_TG and S1_SG, S6_TG and S6_SG, S8_TG and S8_SG, were fully homogenous; all the other paired groups showed a small imbalance in one variable and no paired groups showed non homogeneity. All sessions were retained for further analysis.

3.3. Pairwise comparison of effects

Table 4 shows the significance level and the effect size of changes observed in the psychological domains considered, i.e., STAI-S, POMS-esteem and POMS-TMD, along with the significance level of variance changes across all paired sessions.

Aside from the similar and comparatively poorer performance in sessions S6_TG and S6_SG, TG sessions generally produced significantly superior outcomes in at least one domain or in most of domains, relatively more frequently in self-esteem and anxiety, both in terms of significance and effect size. The overall comparative superiority of therapist-guided experiences was also observed for sessions S2_TG and S2_SG, which were performed in an urban riverine park.

The forest therapy trail of sessions S6_TG and S6_SG, which delivered the poorest performance, was characterized by a steep initial climb (95 m of elevation gain in just 300 m of linear route), followed by crossing an evident black pine plantation, both features being susceptible of hindering restoration and healing effects and likely dominant compared to the effects of different guidance models. None of the other trails included steep climbs or plantations.

The increase in positive emotions arising from the exposure to natural environments was ascribed a specific role for subjective well-being [

51]. Earlier, Stellar and coworkers found significant and inverse associations between positive emotions and inflammation markers [

52], although causality appeared complex and likely bidirectional [

53]. A possible physiological interpretation in the context of the exposure to natural environments was recently provided by Chen and coworkers, based on the consolidated reduction in cortisol in the blood [

54]. Cortisol is a hormone associated with stress and anxiety, leading to immunosuppression and hindrance to the activation of immune natural killer cells; its reduction can enable the activation of natural killer cells via the exposure to plant-emitted monoterpenes, likely mediated by the effect of monoterpenes on the gut microbiota [

54]. Finally, the short-time period of the interventions can not be considered a hindrance to such a biological pathway, since positive emotions can influence inflammatory markers within just a few hours [

52].

Significant reductions in variance were occasionally observed only for therapist-led guidance, specifically for the domains STAI-S (session S1_TG, and close to significance for sessions S2_TG and S5_TG) and POMS-TMD (session S3_TG), suggesting a convergence of participants’ responses following forest therapy intervention. These reductions in variance may reflect a form of regulatory stabilization; for example, with reference to STAI-S, whereby initially more anxious individuals approached the levels of less anxious peers, consistent with notions of emotional homeostasis [

55,

56]. This pattern implies that beyond mean-level shifts, sometimes forest therapy may foster greater homogeneity in state anxiety, reflecting adaptive processes of emotional regulation.

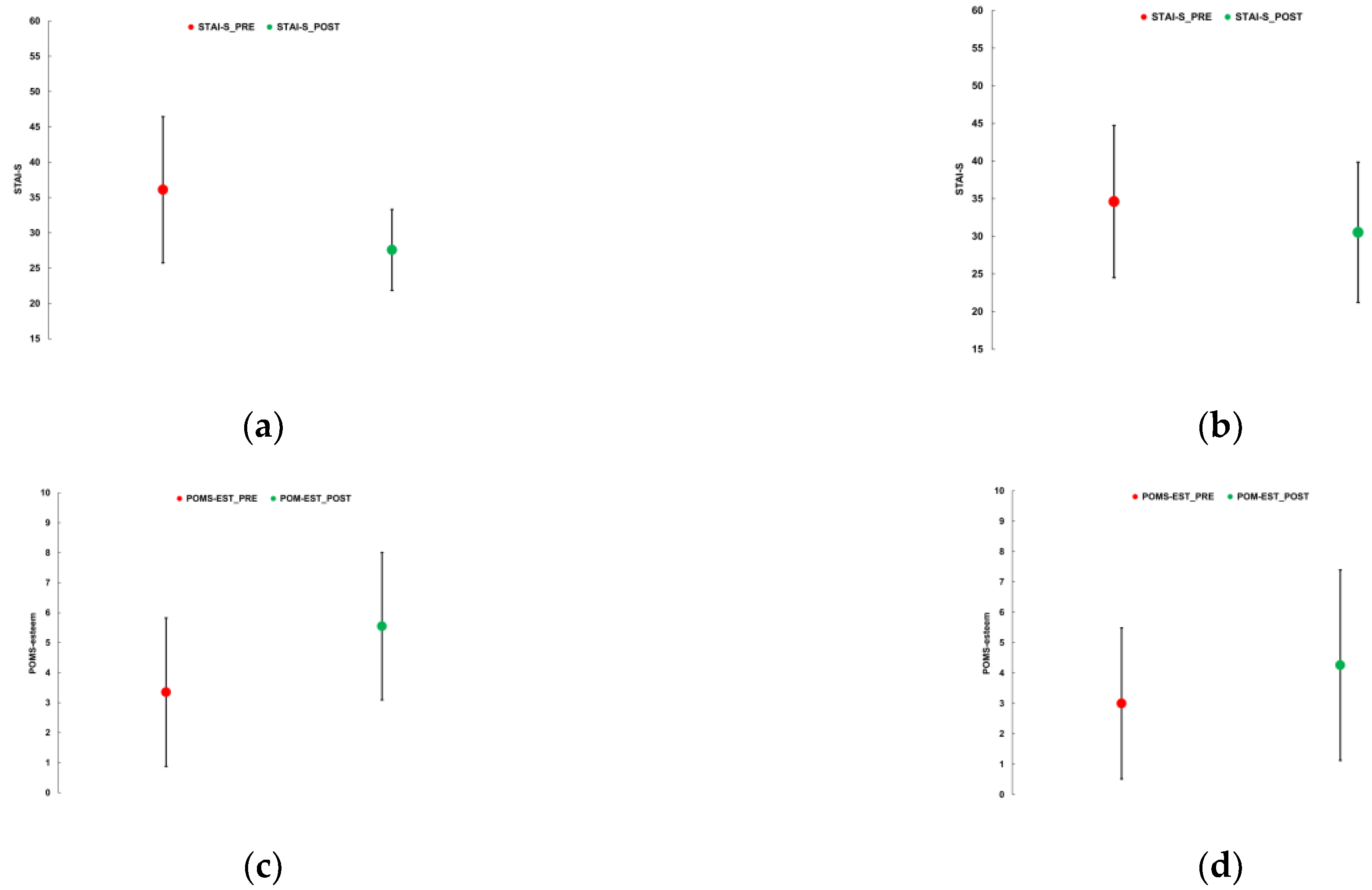

As an example,

Figure 4 shows the changes in psychological domains for sessions S1_TG and S1_SG, for which the TG and SG groups were fully homogenous, the outcomes were significantly different, and S1_TG showed a significant reduction in STAI-S variance.

The superior outcomes observed in TG forest therapy compared to SG experiences, generally for mean levels and occasionally for variance, can be interpreted as an effect of delivery mode rather than intervention content. In TG sessions, the therapist’s voice provided social presence and co-regulation, reducing cognitive demands and fostering deeper attentional absorption, whereas SG participants had to interrupt immersion to read and self-pace written instructions. This difference is consistent with evidence that social cues and reduced cognitive load enhance restoration and flow [

57,

58]. Therapist-led guidance also might activate expectancy and ritual effects, known to amplify psychological benefits [

59], and parallels can be drawn with findings from park prescription programs, where structured group activities produced greater stress reduction than individual instructions alone [

60]. Taken together, these mechanisms suggest that guidance delivered interpersonally strengthens the restorative potential of forest immersion beyond what can be achieved through written instruction alone.

3.4. Economic assessment

Table 5 shows the mean changes in STAI-S, POMS-esteem and POMS-TMD and the preliminary economic assessment of TG and SG guidance modes, computed according to the method described in

Section 2.6. The per-person average changes in STAI-S, POMS-esteem and POMS-TMD and monetization are shown for all sessions, since all paired groups were homogeneous or showed a small non-significant imbalance. Non-significant changes in specific domains were set to 0 and the same domain was excluded from the economic assessment.

The economic assessment, performed according to the methods presented in

Section 2.6, showed remarkably higher annual per person monetization associated with TG sessions compared to SG sessions for S1, S2, S3 and S7, and slightly higher for S8; conversely, SG sessions generated moderately higher monetization for S4 and S5, and slightly higher for S6. All TG sessions generated a significant positive economic value, while sessions S3_SG and S7_SG did not generate a significant monetization. The median level of annual per person monetization for TG sessions was €4076 at the lower threshold of €20,000/QALY and €10,189 at the upper threshold of €50,000/QALY, while the corresponding levels for SG session were €2462 and €6154, with a ratio of nearly 1.7.

Table S1 in

Supplementary Materials shows the same estimates as in

Table 5, limited to the lower threshold of €20,000/QALY and with the progressive inclusion of STAI-S, POMS-TMD and POMS-esteem. Although these domains showed remarkable mutual correlations, the contribution of domains other than STAI-S contributed substantially to the estimates, up to more than four times compared to assessment based on STAI-S only, with POMS-esteem contributing more than POMS-TMD and, in the case of sessions S6_TG and S6_SG, being the sole responsible for the positive figures.

Recalling that forest immersion experiences should be performed once a week for 4 consecutive weeks to carry over long-term effects during the following month, approximately 25 sessions are needed every year. We can further assume, based on the experience of the performed forest therapy sessions, that a therapist can lead on average 20 people per session, while the same therapist could be assigned a gross compensation per session of €400 i.e., approximately a gross compensation of €10,000 on an annual basis. Thus, each person participating to TG sessions could be ascribed an annual cost of approximately €500 (€10,000 divided by 20 people) due to the therapist guidance, which is approximately 12% of the estimated median annual per person monetization of TG sessions at the lower threshold of €20,000/QALY, translating into an annual saving of approximately €3600 per person, with the corresponding figures rising to approximately 5% and €9700 at the upper threshold of €20,000/QALY.

Notably, the therapist-related per-person cost of €500 is approximately 30% of the estimated figure of €1614 (€4076-€2462) for the added annual economic value per person of TG sessions compared to SG sessions at the lower threshold of €20,000/QALY, and just approximately 10% of the corresponding estimated figure of €4035 (€10,189-€6154) at the upper threshold of €50,000/QALY. In other words, a TG-session program would produce an annual per person saving nearly 1.5 greater than the corresponding figure for a SG-session program (€3576 vs €2462).

Our findings complement and extend recent work linking forest-based well-being improvements to economic value [

42]. Whereas that study demonstrated the feasibility of mapping PWI gains into QALY increments and AU

$ values, our approach integrates validated psychometric instruments (STAI, POMS-TMD, POMS-Esteem) within a comparative TG vs SG design. Together, these lines of evidence strengthen the case for considering forest therapy not only as an individual health-promoting practice, but also as an intervention with quantifiable economic benefits, suitable for inclusion in healthcare protocols.

3.5. Limitations

The generalization of the presented results is hindered by the limited number of pairwise sessions and participants and the partial representativeness of the natural environments, which were all located in Italy. The economic assessment should be considered preliminary and likely affected by significant uncertainties due to the oversimplified assumptions; moreover, the comparative estimate of operational savings achieved by means of a TG- compared to a SG-session program did not account for other capital costs, such as equipping and maintaining the signage along the forest immersion trails, which are needed to allow SG sessions and useful for the purpose of attracting further tourism and thus directly benefit local communities.

The economic assessment was based only on direct mental health benefits, not accounting for either physiological health benefits and personal productivity increases. For example, a research in Australia showed that the increase in economic productivity related to independent public visits to protected areas produced a 3 times higher monetization than the reduction in healthcare expenditure [

36]; while mental health improvements are likely associated with an increase in economic productivity and the QALY-based monetization could include at least part of the latter effect, the possibility remains that the figures presented were affected by a systematic underestimation. For example, a recent research based on 1400 interviewees in a survey conducted in Italy found that visiting forests and green spaces at least once in the past year was associated with a higher life satisfaction equivalent to a €11,171 increase in average income [

61], which is higher than our the figures presented in this study even at the upper threshold of €50,000/QALY. Although the life satisfaction approach is completely different from the approach adopted in this study, along with the increase in economic productivity it suggests that the real economic spillover of forest therapy programs might be substantially higher and encompass multiple dimensions.

However, within the limitations of this study, the results concerning both mental health parameters and monetization showed a clear added value of therapist-led guidance, which is therefore not only mandatory for clinically-relevant forest therapy interventions, but also significantly more effective compared with self-guidance.

4. Conclusions

This study provides original comparative evidence showing that therapist-guided forest therapy conveys significantly greater short-term mental health benefits than an equivalent forest immersion (same site and time) conducted in a self-guided format. Sessions were carried out in eight different forest sites, in natural outdoor settings, with groups of adult participants.

Therapist-led sessions consistently outperformed self-guided ones in reducing state anxiety and total mood disturbance, while simultaneously enhancing self-esteem. These effects were occasionally accompanied by a reductions in variability across specific domains, suggesting a stabilization of participants’ emotional states, in line with theories of psychological homeostasis. The findings underscore that the interpersonal guidance—through the therapist’s voice, presence, and co-regulation—cannot be fully replicated by written instructions, which tend to impose cognitive load that may interrupt immersion and reduce restorative processes.

The preliminary economic analysis further highlighted the added value of therapist guidance, showing that the incremental costs of professional involvement are outweighed by the projected gains in quality-adjusted life years and the associated monetary value. These results strengthen the rationale for considering forest therapy as a cost-effective intervention within preventive and complementary health strategies, especially relevant in societies increasingly burdened by rising stress and anxiety linked to urbanization.

Certain constraints remain, particularly the limited number of sessions, sites and participants, as well as the simplified assumptions underlying the economic model. Nevertheless, the consistency of outcomes across heterogeneous contexts suggests that therapist-guided forest therapy deserves broader implementation and systematic evaluation. Future studies should incorporate long-term follow-ups, physiological health indicators, and more refines health-economic models capable of capturing productivity gains and healthcare savings. Taken together, these results position therapist-guided forest therapy as a scalable, low-risk and economically valuable addition to public health portfolios.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Table S1: Estimate of annual economic value of TG and SG sessions for the lower threshold of 20,000 €/QALY, with progressive inclusion of STAI-S, POMS-TMD and POMS-esteem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Rosa Rivieccio and Francesco Meneguzzo; Data curation, Rosa Rivieccio, Francesco Meneguzzo and Federica Zabini; Funding acquisition, Francesco Meneguzzo and Federica Zabini; Investigation, Rosa Rivieccio, Francesco Meneguzzo, Giovanni Margheritini and Tania Re; Methodology, Francesco Meneguzzo, Tania Re and Federica Zabini; Project administration, Giovanni Margheritini and Federica Zabini; Resources, Giovanni Margheritini; Software, Rosa Rivieccio and Francesco Meneguzzo; Supervision, Ubaldo Riccucci and Federica Zabini; Validation, Francesco Meneguzzo and Ubaldo Riccucci; Visualization, Rosa Rivieccio; Writing – original draft, Rosa Rivieccio, Francesco Meneguzzo, Tania Re and Ubaldo Riccucci.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Consorzio Melinda Sca, grant number: quotation of the Institute of Bioeconomy, National Research Council of Italy, number 0005610 of 15-December-2021, DBA.AD001.491; Tuscany Regional Government under the project Forests and Health (FOR.SA), grant number CUP: 1241140; Partenio Regional Park , grant number: Resolution: 27 of 20-March-2025; Cimini Mountains Authority - Vico Lake Reserve under the project Nature and/is Wellbeing, grant number CUP: D94J25000570002.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the National Research Council (CNR) Ethics Committee n. 0069654/2021 (20-October-2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. All subjects were anonymized and no subject can be identified.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request. Such data will also be openly shared in the form of a structured database in an upcoming study.

Acknowledgments

Pordenone and Mantua Sections of the Italian Alpine Club, Luca Lovatti, Jessica Paternoster and Jamine Chini of Consorzio Melinda Sca, Francesco Iovino and Luigi Iozzoli of Partenio Regional Park, Eugenio Maria Monaco, Ilaria de Parri and Andrea Sasso of Cimini Mountains Authority - Vico Lake Reserve, are gratefully acknowledged for the invaluable logistic help, accommodation, communication and recruitment of voluntary participants for part of the experimental field study; A. Sasso is also gratefully thanked for the permission to use copies of the boards shown in Figure 3. During the preparation of this study, the authors used ChatGPT 5 (OpenAI, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) for the purpose of debugging python codes. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CEAC |

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve |

| FH |

Fully homogenous |

| KNN |

k-nearest neighbors |

| POMS |

Profile of Mood States |

| POMS-esteem |

Profile of Mood States – self-esteem |

| POMS-TMD |

Profile of Mood States – total mood disturbance |

| QALY |

Quality-adjusted life years |

| SAC |

Special Area of Conservation |

| SG |

Self-guided |

| SI |

Small imbalance |

| SPA |

Special Protection Area |

| STAI |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| STAI-S |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – state |

| STAI-T |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – trait |

| TG |

Therapist-guided |

References

- Wen, Y.; Yan, Q.; Pan, Y.; Gu, X.; Liu, Y. Medical Empirical Research on Forest Bathing (Shinrin-Yoku): A Systematic Review. Environ Health Prev Med 2019, 24, 70. [CrossRef]

- Mazzoleni, E.; Donelli, D.; Zabini, F.; Meneguzzo, F.; Antonelli, M. Forest Therapy Research in Europe: A Scoping Review of the Scientific Literature. Forests 2024, 15, 848. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Meng, Z.; Luo, J. Is Forest Bathing a Panacea for Mental Health Problems? A Narrative Review. Front Public Health 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Baldessari, S.; Barbierato, E.; Bernetti, I.; Cerutti, A.; Righi, S.; Ruggieri, B.; Landi, A.; Notaro, S.; Sacchelli, S. A Quantitative Literature Review on Forest-Based Practices for Human Well-Being. Forests 2025, 16, 1246. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Preventive Effects of Forest Bathing/Shinrin-Yoku on Cardiovascular Diseases: A Review of Mechanistic Evidence. Forests 2025, 16, 310. [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, H.; Inoue, S.; Masuda, G.; Amagasa, S.; Sugishita, T.; Ochiai, T.; Yanagisawa, N.; Nakata, Y.; Imai, M. Randomized Controlled Trial on the Efficacy of Forest Walking Compared to Urban Walking in Enhancing Mucosal Immunity. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 3272. [CrossRef]

- Donelli, D.; Meneguzzo, F.; Antonelli, M.; Ardissino, D.; Niccoli, G.; Gronchi, G.; Baraldi, R.; Neri, L.; Zabini, F. Effects of Plant-Emitted Monoterpenes on Anxiety Symptoms: A Propensity-Matched Observational Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 2773. [CrossRef]

- Steininger, M.O.; White, M.P.; Lengersdorff, L.; Zhang, L.; Smalley, A.J.; Kühn, S.; Lamm, C. Nature Exposure Induces Analgesic Effects by Acting on Nociception-Related Neural Processing. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 2037. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Takayama, N.; Kimura, Y.; Takayama, H.; Kumeda, S.; Miura, T.; Kitagawa, T.; Aoyagi, Y.; Imai, M. Forest Bathing Improves Inflammatory Markers, SpO2 and Subjective Symptoms Related to COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease) in Male Subjects at Risk of Developing COPD. J Occup Health 2025. [CrossRef]

- Serrat, M.; Royuela-Colomer, E.; Alonso-Marsol, S.; Ferrés, S.; Nieto, R.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Muro, A. The Psychological Benefits of Forest Bathing in Individuals with Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: A Pilot Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1654. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Lin, P.; Williams, J. Effectiveness of Nature-Based Walking Interventions in Improving Mental Health in Adults: A Systematic Review. Current Psychology 2024, 43, 9521–9539. [CrossRef]

- Caponnetto, P.; Inguscio, L.; Triscari, S.; Casu, M.; Ferrante, A.; Cocuzza, D.; Maglia, M.M. New Perspectives in Psychopathology and Psychological Well-Being by Using Forest Therapy: A Systematic Review. Open Psychol J 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- Miani, A.; Shang, J. Nature as Medicine: A One Health Approach to Global Health Challenges. International Journal of Environmental Medicine 2025, 1, 2. [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.C.; Cooper, M.A.; Zhong, L. Principal Sensory Experiences of Forest Visitors in Four Countries, for Evidence-Based Nature Therapy. People and Nature 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.G.; Shin, W.S. Forest Therapy Alone or with a Guide: Is There a Difference between Self-Guided Forest Therapy and Guided Forest Therapy Programs? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 6957. [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.-S.; Kim, J.-G. The Influence of Self-Guided and Guided Forest Therapy Program on Students’ Psychological Benefits. Journal of People, Plants, and Environment 2023, 26, 169–179. [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.S.; Seong, I.K.; Kim, J.G. Psychological Benefits of Self-Guided Forest Healing Program Using Campus Forests. Forests 2023, 14, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Xu, T.; Luo, J.; Wang, X.; Lin, S.; Lin, C.; Hong, Y.; Chang, W. The Evidence for Stress Recovery in Forest Therapy Programs: Investigating Whether Forest Walking and Guided Forest Therapy Activities Have the Same Potential? J For Res (Harbin) 2025, 36, 15. [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.; Brough, P.; Hague, L.; Chauvenet, A.; Fleming, C.; Roche, E.; Sofija, E.; Harris, N. Economic Value of Protected Areas via Visitor Mental Health. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 5005. [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Sydeman, S.J.; Owen, A.E.; Marsh, B.J. Measuring Anxiety and Anger with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). In The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment; Maruish, M.E., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 993–1021.

- Grove, J.R.; Prapavessis, H. Preliminary Evidence for the Reliability and Validity of an Abbreviated Profile of Mood States. Int J Sport Psychol 1992, 23, 93–109.

- Longman, D.P.; Van Hedger, S.C.; McEwan, K.; Griffin, E.; Hannon, C.; Harvey, I.; Kikuta, T.; Nickels, M.; O’Donnell, E.; Pham, V.A.-V.; et al. Forest Soundscapes Improve Mood, Restoration and Cognition, but Not Physiological Stress or Immunity, Relative to Industrial Soundscapes. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 33967. [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.; Cao, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, S.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Xing, W.; Ren, X.; Lv, X.; Dong, J.; et al. The Salutary Influence of Forest Bathing on Elderly Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017, 14, 368. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, V.; Pourtois, G. Transient State-Dependent Fluctuations in Anxiety Measured Using STAI, POMS, PANAS or VAS: A Comparative Review. Anxiety Stress Coping 2012, 25, 603–645. [CrossRef]

- Troyanskaya, O.; Cantor, M.; Sherlock, G.; Brown, P.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Botstein, D.; Altman, R.B. Missing Value Estimation Methods for DNA Microarrays. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 520–525. [CrossRef]

- Beretta, L.; Santaniello, A. Nearest Neighbor Imputation Algorithms: A Critical Evaluation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2016, 16, 74. [CrossRef]

- Dempster, A.P.; Laird, N.M.; Rubin, D.B. Maximum Likelihood from Incomplete Data Via the EM Algorithm. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 1977, 39, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys; Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics; Wiley, 1987; ISBN 9780471087052.

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830.

- McHugh, M.L. The Chi-Square Test of Independence. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2013, 143–149. [CrossRef]

- Cramér, H. Mathematical Methods of Statistics; Princeton Univ. Press: New York, USA, 1999;

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; 2nd Editio.; Routledge: New York, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781134742707.

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W.; others Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference; van der Walt, S., Millman, J., Eds.; 2010; pp. 51–56.

- Barnes, L.L.B.; Harp, D.; Jung, W.S. Reliability Generalization of Scores on the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Educ Psychol Meas 2002, 62, 603–618. [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.C.; Chauvenet, A.L.M. Economic Value of Nature via Healthcare Savings and Productivity Increases. Biol Conserv 2022, 272, 109665. [CrossRef]

- Menardo, E.; Brondino, M.; Hall, R.; Pasini, M. Restorativeness in Natural and Urban Environments: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol Rep 2021, 124, 417–437. [CrossRef]

- Czakert, J.; Kandil, F.I.; Boujnah, H.; Tavakolian, P.; Blakeslee, S.B.; Stritter, W.; Dommisch, H.; Seifert, G. Scenting Serenity: Influence of Essential-Oil Vaporization on Dental Anxiety - a Cluster-Randomized, Controlled, Single-Blinded Study (AROMA_dent). Sci Rep 2024, 14, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Delacre, M.; Lakens, D.; Leys, C. Why Psychologists Should by Default Use Welch’s t-Test Instead of Student’s t-Test. International Review of Social Psychology 2017, 30, 92–101. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Abascal, E.G.; Martín-Díaz, M.D. Longitudinal Study on Affect, Psychological Well-Being, Depression, Mental and Physical Health, Prior to and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain. Pers Individ Dif 2021, 172, 110591. [CrossRef]

- Markwell, N.; Gladwin, T.E. Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) Reduces Stress and Increases People’s Positive Affect and Well-Being in Comparison with Its Digital Counterpart. Ecopsychology 2020, 12, 247–256. [CrossRef]

- Chauvenet, A.L.M.; Wardle, C.; Westaway, D.; Buckley, R. Duration and Economic Value of a Walking-in-nature Therapy Programme: Implications for Conservation. People and Nature 2025. [CrossRef]

- Norman, G.R.; Sloan, J.A.; Wyrwich, K.W. Interpretation of Changes in Health-Related Quality of Life. Med Care 2003, 41, 582–592. [CrossRef]

- König, H.-H.; Born, A.; Günther, O.; Matschinger, H.; Heinrich, S.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Roick, C. Validity and Responsiveness of the EQ-5D in Assessing and Valuing Health Status in Patients with Anxiety Disorders. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 47. [CrossRef]

- Rencz, F.; Mukuria, C.; Bató, A.; Poór, A.K.; Finch, A.P. A Qualitative Investigation of the Relevance of Skin Irritation and Self-Confidence Bolt-Ons and Their Conceptual Overlap with the EQ-5D in Patients with Psoriasis. Quality of Life Research 2022, 31, 3049–3060. [CrossRef]

- Szlávicz, E.; Szabó, Á.; Kinyó, Á.; Szeiffert, A.; Bancsók, T.; Brodszky, V.; Gyulai, R.; Rencz, F. Content Validity of the EQ-5D-5L with Skin Irritation and Self-Confidence Bolt-Ons in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis: A Qualitative Think-Aloud Study. Quality of Life Research 2024, 33, 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Yin, J.; An, Y.; Wang, J.; Qiu, J. The Structural Validity and Latent Profile Characteristics of the Abbreviated Profile of Mood States among Chinese Athletes. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 636. [CrossRef]

- Russo, P.; Zanuzzi, M.; Carletto, A.; Sammarco, A.; Romano, F.; Manca, A. Role of Economic Evaluations on Pricing of Medicines Reimbursed by the Italian National Health Service. Pharmacoeconomics 2023, 41, 107–117. [CrossRef]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R.J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 1994; ISBN 9780429246593.

- Fenwick, E.; O’Brien, B.J.; Briggs, A. Cost-effectiveness Acceptability Curves – Facts, Fallacies and Frequently Asked Questions. Health Econ 2004, 13, 405–415. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Zhang, S.; He, H.; Xu, M. Nature Perception and Positive Emotions in Urban Forest Parks Enhance Subjective Well-Being. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 31457. [CrossRef]

- Stellar, J.E.; John-Henderson, N.; Anderson, C.L.; Gordon, A.M.; McNeil, G.D.; Keltner, D. Positive Affect and Markers of Inflammation: Discrete Positive Emotions Predict Lower Levels of Inflammatory Cytokines. Emotion 2015, 15, 129–133. [CrossRef]

- Mac Giollabhui, N.; Slaney, C.; Hemani, G.; Foley, É.M.; van der Most, P.J.; Nolte, I.M.; Snieder, H.; Davey Smith, G.; Khandaker, G.M.; Hartman, C.A. Role of Inflammation in Depressive and Anxiety Disorders, Affect, and Cognition: Genetic and Non-Genetic Findings in the Lifelines Cohort Study. Transl Psychiatry 2025, 15, 164. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhu, H.; Jounaidi, Y. Comprehensive Snapshots of Natural Killer Cells Functions, Signaling, Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Utilization. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 302. [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, D.S.; Young, S.N. Ecological Momentary Assessment: What It Is and Why It Is a Method of the Future in Clinical Psychopharmacology. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2006, 31, 13–20.

- Houben, M.; Van Den Noortgate, W.; Kuppens, P. The Relation between Short-Term Emotion Dynamics and Psychological Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol Bull 2015, 141, 901–930. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. J Environ Psychol 1991, 11, 201–230. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, NY, 1989; ISBN 9780521349390.

- Price, D.D.; Finniss, D.G.; Benedetti, F. A Comprehensive Review of the Placebo Effect: Recent Advances and Current Thought. Annu Rev Psychol 2008, 59, 565–590. [CrossRef]

- Razani, N.; Morshed, S.; Kohn, M.A.; Wells, N.M.; Thompson, D.; Alqassari, M.; Agodi, A.; Rutherford, G.W. Effect of Park Prescriptions with and without Group Visits to Parks on Stress Reduction in Low-Income Parents: SHINE Randomized Trial. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0192921. [CrossRef]

- Sealy Phelan, A.; Grilli, G.; Pisani, E.; Secco, L. Using the Life Satisfaction Approach to Economically Value the Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Forest and Green Space Visits in Italy. For Policy Econ 2025, 181, 103640. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).