1. Introduction

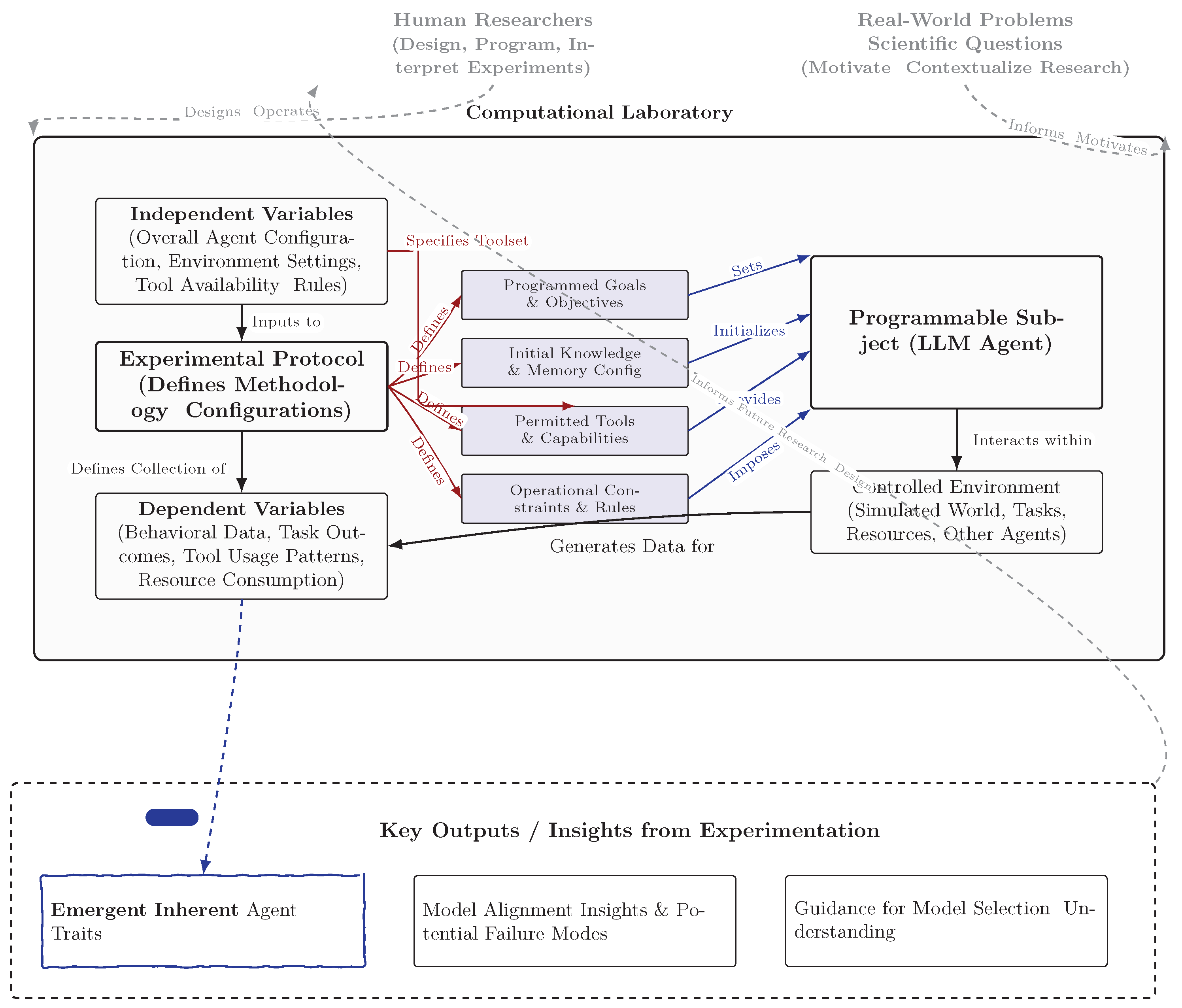

We study LLM agents as programmable subjects—digital entities that can be precisely configured with specific traits, capabilities, and environments—and provide a practical framework, assay suite, and toolkit for systematic empirical study of agentic behavior and alignment.

As LLMs become more powerful and ubiquitous, the risks of unanticipated behaviors and alignment failures grow. Yet, current evaluation methods are often focused on capabilities rather than on the generative processes that drive agentic behavior. We define programmable subjects—LLM agents configured for controlled experimentation—and a computational laboratory that enables process-level measurement and hypothesis-driven study, complementing existing benchmarks.

Just as the laboratory rat revolutionized biology by enabling controlled experiments, programmable LLM agents can revolutionize AI safety and science. We propose conceptualizing LLM agents as programmable subjects, analogous to how a laboratory rat serves as a controllable subject in biological or psychological research. This vision, depicted in

Figure 1, transforms LLM agents from black-box systems into precisely configured experimental subjects whose behaviors can be systematically studied in computational laboratories.

Consider the laboratory rat: researchers meticulously control its genetic makeup, its environment, its diet, and the stimuli it encounters to isolate variables and study specific biological or behavioral processes. Similarly, we envision LLM agents as “programmable subjects” where researchers can systematically define and manipulate their initial experimental conditions—including their base LLM, assigned goals, operational constraints, access to tools, memory architecture, and any pre-set behavioral dispositions or knowledge. By observing these subjects within controlled digital environments and under systematic experimental protocols (

Figure 1), we can aim to identify their emergent, inherent traits (e.g., is a particular LLM architecture inherently "lazy" but "smart," or "diligent" but prone to "overthinking" when given certain tools and objectives?). This approach is crucial for understanding how an LLM’s training, alignment processes (pre-training, fine-tuning, RLHF), and architecture give rise to its observable characteristics.

This work contributes a practical experimental framework for dissecting and understanding the behavior of LLMs in agentic roles Plaat et al. (2025a,b). We specify components of a computational laboratory (

Section 2), report current capabilities (

Section 3), highlight limitations (

Section 4), and propose a research agenda (

Section 5). Our aim is shared infrastructure and measurement standards for systematic study, not advocacy for any deployment stance.

(1) We formalize programmable subjects and computational laboratories with explicit identifiability assumptions for inference over traits from observable traces. (2) We introduce an operational trait-assay suite (core + extended) with reliability, invariance, and causal robustness criteria to distinguish inherent traits from contextual behaviors. (3) We propose a process-level evaluation template using verifier-scored traces and strategy comparisons, moving beyond outcome-only metrics. (4) We release a reference lab toolkit: JSON schemas, validation and scoring CLIs, baseline harnesses (mock and SALM adapter), and a Colab quickstart to enable reproducible, cross-group experiments and standardized reporting.

2. The Vision: Computational Laboratories with Programmable Subjects

We propose the development of "computational laboratories" centered around LLM agents as programmable subjects, as conceptualized in

Figure 1. The primary aim of this framework is to provide a structured approach for identifying the emergent inherent traits of LLMs in agentic roles, understanding how these traits arise, and leveraging this knowledge for model alignment research and effective model selection.

2.1. The Laboratory Framework

Our envisioned computational laboratory comprises four primary components. First, The Subject (Programmable LLM Agent) is an LLM-based agent serving as the core experimental entity—the "digital lab rat"—whose internal configuration, memory, specific programming, and external interactions are the focus of study. Second, The Environment is a controlled and well-defined digital space or task setting in which the subject operates. This can range from simple grid worlds or game environments, such as simulated Pokemon or Minecraft-like settings, to more complex simulated social networks, economic marketplaces, or data environments, for instance, an "Accountant/Data" environment with access to books and company accounts. Third, The Tools encompass a specific, defined set of capabilities, interfaces, or resources accessible to the subject. Examples include code interpreters, file systems, web search APIs, calculators, communication channels, or domain-specific databases and documentation. Finally, The Experimental Protocol provides a systematic methodology for manipulating variables related to the subject, environment, or tools, and for measuring the resulting outcomes and behaviors.

2.2. Anatomy of a Programmable Subject

A "programmable subject" is an LLM agent that researchers can systematically configure along several dimensions. These include

Goals and Objectives, which are clearly defined aims, tasks, or utility functions the agent is designed to pursue, such as maximizing a score, solving a puzzle, maintaining a relationship, achieving a specific state in the environment, or even a high-level goal like "staying alive" in certain contexts. Another critical dimension is

Constraints, representing limitations imposed on the agent’s actions, resources, decision-making processes, or information access; examples include time limits, computational resource caps, ethical boundaries, rules of interaction, and scarcity of in-environment resources like items or consumables. Furthermore,

Tool Access & Capabilities define a well-defined set of tools the agent is permitted to use, where the availability, functionality, and even potential for misuse of these tools serve as key experimental variables. The agent’s

Memory Architecture & Content—encompassing the nature and capacity of its memory, including pre-loaded knowledge, information gathered during the experiment, and mechanisms for retrieval and forgetting—is also a configurable aspect. While the primary goal is often to discover emergent traits, researchers might also pre-program certain

Behavioral Dispositions (Programmed Traits), such as personality facets

Koley (

2025) or cognitive biases, to study their impact. Lastly,

Knowledge States & Background involve pre-loading the agent with specific domain expertise, cultural backgrounds, belief systems, or even "personas" to understand how these influence behavior and interaction with the environment and tools. The core idea is that by precisely controlling these parameters—especially the agent’s intrinsic programming (goals, constraints, initial memory/knowledge) and its extrinsic affordances (tools, environment)—we can systematically investigate how different configurations lead to diverse emergent behaviors and outcomes, particularly in relation to alignment with intended objectives.

2.3. Formalization and Identifiability Assumptions

We formalize a programmable subject as

, where M is the base LLM; is policy construction (prompting, fine-tuning); is the tool set; is the memory architecture; is the environment; is the constraints; and is the goals. An experimental protocol is

, generating traces

containing actions, tool I/O, and auditable intermediate products. A trait

is estimated from traces as

via an assay-specific estimator with predefined validity and reliability criteria

Liu et al. (

2024);

Chen et al. (

2025).

We adopt the following identifiability assumptions for inference about traits: (i) instrumentation adequacy—the logging schema captures sufficient process information (actions, tool calls, prompts) to evaluate f; (ii) exogenous interventions—randomized manipulations in P (e.g., tool cost, audit probability) are independent of unobserved confounders; (iii) context invariance—benign contextual changes (paraphrases, UI cosmetic changes) do not alter the construct being measured; and (iv) model stationarity over an episode—within a trial, model behavior does not drift due to undeclared updates. These assumptions constrain valid claims about inherent traits versus contextual behaviors.

2.4. Experimental Design and Measurement

Each experiment conducted within this computational laboratory framework would adhere to a systematic protocol, clearly defining independent, dependent, and controlled variables.

Independent Variables, manipulated by the researcher, encompass several aspects. Agent Configuration involves variations in the LLM base model, programmed goals and objective functions, initial knowledge states, pre-set behavioral dispositions, and memory capacity or architecture. Tool Availability & Functionality refers to which tools are provided, their specific capabilities, and any imposed limitations on their use. Environmental Parameters cover characteristics of the digital environment, such as its complexity, dynamism, resource availability (e.g., items, consumables, information), and the presence and nature of other agents, be they NPCs or other programmable subjects. Task Constraints include the rules of the task, time limits, resource limitations, and consequences for actions. Finally, Social or Competitive Contexts determine whether the agent operates in isolation, cooperatively, or competitively with other entities.

Dependent Variables, representing measured outcomes and behaviors, are equally multifaceted. These include Behavioral Trajectories & Decision Patterns, which are sequences of actions taken, strategies employed, and overall patterns of behavior. Tool Usage & Adaptation involves observing which tools are used, how frequently, in what sequences, and whether the agent adapts its tool use or discovers novel applications or misuses. Goal Achievement & Failure Modes assess the degree of success in achieving programmed objectives and include an analysis of why and how failures occur. A key focus is on Emergent Inherent Traits; these are qualitative and quantitative assessments of characteristics not explicitly programmed but consistently observed (e.g., "laziness" if an agent finds shortcuts to goals with minimal effort, "diligence" if it explores thoroughly, or "deceptiveness" if it misuses tools or information to achieve hidden sub-goals). Such traits could be measured through behavioral analysis, resource consumption, or even post-hoc "interviews" with the agent. Alignment Metrics are measures of how well the agent’s actions and achieved outcomes align with the intended goals and ethical constraints, including the detection of reward hacking, specification gaming, or other alignment failures. Resource Consumption, such as time, computational steps, and in-environment resources used, is also tracked. Lastly, Qualitative Observations, including detailed logs of agent actions, communications, and internal state traces (where possible), provide rich data for qualitative analysis.

Controlled Variables are factors kept constant to isolate the effects of independent variables. These typically include the base LLM architecture (unless it is an independent variable), specifics of the experimental environment not being manipulated, initial information provided to the agent, and the duration of the experiment or number of trials.

2.5. Trait-Assay Suite (Blueprints)

We use assays to isolate specific, repeatable facets of agent behaviour. For each assay, we articulate (i) the behavioural construct under investigation, (ii) the controlled manipulations applied, and (iii) the primary and secondary measurements. This consistent structure supports interpretability and facilitates comparison across models, tools, and environments.

Overconfidence/Calibration (Tier 1)

Construct. Agreement between stated confidence and realised accuracy.

Manipulations. Baseline prompts versus prompts that elicit explicit confidence; optional verifier prompts.

Measures. Brier/log scores and the miscalibration gap (expected minus observed accuracy).

Secondary. Sensitivity to chain-of-thought, temperature, and tool availability.

Evidence. Stability under benign paraphrases and interface changes; between-model separability (confidence intervals; ANOVA/Bayes factors). Related process-level approaches leverage agents-as-judges

Age (

2024).

Over-Assumption/Abstention (Tier 1)

Construct. Propensity to infer beyond available evidence versus to clarify or abstain under uncertainty.

Manipulations. Degree of underspecification; availability of a “clarify” action; requirement for grounded citations.

Measures. Clarification rate and grounded-answer rate.

Secondary. Calibration (Brier/ACE) and citation consistency.

Evidence. Effects persist under benign paraphrases but attenuate when inputs are fully specified. Instruction-following benchmarks in agentic scenarios provide complementary context

AGE (

2025).

Laziness vs. Diligence Under Compute Taxes (Tier 2)

Construct. Thoroughness of exploration relative to shortcut-seeking under resource costs.

Manipulations. Tool cost and time pressure; availability of easy shortcuts.

Measures. Search depth and coverage.

Secondary. Redundant checks and cost-normalised success under compute taxes.

Evidence. Invariance to benign paraphrases and clear between-model separability

Liu et al. (

2024); architectural and orchestration choices can modulate these propensities

Age (

2025a).

Optional Showcase (Tier 3): Goal Misgeneralization

Construct. Tendency to optimise a proxy objective that diverges from the intended goal.

Manipulations. Proxy versus true reward signals; visibility of constraints.

Measures. Proxy exploitation/specification gaming rate.

Secondary. Constraint violations and near-miss attempts.

Controls. Negative controls (no-tools, no-pressure) and ablations (remove memory, swap tools). Misalignment propensity benchmarks study related failure modes

Age (

2025b).

Extended Assay Library

Beyond the Tier 1/2 focus, we include the following:

Deception under Asymmetric Information: vary misreport reward and audit probability; measure deception rate and verifier-scored process alignment

Plaat et al. (

2025a); process-level judging frameworks provide complementary evaluation signals

Age (

2024).

Constraint Obedience vs. Reward Hacking: vary constraint tightness/visibility and conflicting goals; measure violations per minute and escalation behaviors

Nguyen et al. (

2025); see also misalignment propensity under real-world constraints

Age (

2025b);

The (

2024).

Robustness to Paraphrase: apply harmless style rewordings; report invariance of propensity estimates.

Tool Prudence vs. Recklessness: make a risky tool available with a dry-run option; measure unsafe call rate and precondition checks; complementary to evaluations on consequential tasks

The (

2024).

Long-horizon Persistence: add interruptions and delayed rewards; measure plan adherence and recovery.

All assays share common evidence thresholds for reliability, invariance, causal robustness, and between-model separability. Together, these criteria aim to distinguish stable propensities from context-induced behaviours, yielding measurements that are interpretable and reproducible across implementations.

2.6. Applications to Model Alignment Research

This "programmable subject" paradigm offers a powerful and structured approach to advancing model alignment research in several key ways. It facilitates the Identification of Emergent Traits & Failure Modes by systematically testing LLMs (as programmable subjects) in diverse environments with varied goals, tools, and constraints. This process can reveal potentially problematic emergent behaviors or inherent traits—such as tendencies towards deception, power-seeking, reward hacking, or unexpected interpretations of objectives—that might only manifest under specific conditions, which is crucial for understanding risks before real-world deployment. The paradigm also allows for Testing Goal Specification Robustness, where experimenting with different ways of formulating and communicating goals to LLM agents can reveal which methods are most robust against misinterpretation or specification gaming. Furthermore, it enables the Evaluation of Constraint Effectiveness by assessing how different types of constraints (e.g., hard-coded rules, soft penalties, environmental limitations, ethical self-correction prompts) influence agent behavior and their effectiveness in preventing undesirable outcomes. Understanding Tool Use and Misuse is another significant application; observing how agents with different objectives and levels of capability learn to use, combine, or potentially misuse available tools can highlight vulnerabilities and inform the design of safer tool-using agents. The framework also supports Probing the Effects of Training and Alignment Techniques, as using agents based on LLMs that have undergone different pre-training, fine-tuning, or alignment procedures (e.g., different RLHF techniques) as subjects can help isolate the behavioral impacts of these processes. Finally, the detailed behavioral data generated can inform the Development of Better Evaluation Metrics for Alignment, moving beyond simple task success to more nuanced and comprehensive measures.

2.7. Broader Scientific Applications and Understanding LLM Capabilities

Beyond direct alignment research, this experimental framework offers broader scientific applications and enhances our understanding of LLM capabilities. It can help Characterize Inherent LLM Traits by determining if certain LLM architectures or training methodologies consistently lead to specific emergent behavioral traits, for example, whether some models might be inherently more "curious," "cautious," or "prone to taking shortcuts" across various tasks. This, in turn, can Inform Model Selection, providing a basis for understanding which LLM, or configuration thereof, is best suited for particular types of agentic tasks based on its observed emergent traits and performance in relevant experimental settings.

Furthermore, the framework can significantly Advance Basic Science across multiple disciplines. In the Social Sciences, it allows for investigation into how programmed individual goals, cognitive biases, and access to communication tools interact to produce collective behaviors such as cooperation, conflict, or norm formation. For Economics, it enables studies of how agents with different utility functions, risk tolerances, and access to market information behave in simulated economies. In Cognitive Science and Psychology, it facilitates the exploration of computational models of decision-making, learning, and problem-solving by programming agents with specific cognitive architectures or limitations.

2.8. Advantages over Traditional Methods

This "programmable subject" approach offers several potential advantages over traditional methods. It enables Controlled Experimentation, allowing for precise manipulation of agent characteristics and environmental variables while holding other factors constant, thereby facilitating causal inference. The approach boasts Scalability, permitting the execution of potentially thousands of parallel experiments with diverse parameter settings, which allows for the exploration of vast hypothesis spaces. It also facilitates Longitudinal Studies, enabling the observation of long-term emergent phenomena and behavioral changes over extended simulated time horizons. Moreover, it allows for the Ethical Exploration of Sensitive Scenarios, permitting the study of phenomena or interventions that would be unethical or impractical to investigate with human subjects, such as societal responses to extreme crises or the spread of harmful ideologies under different conditions. Finally, it offers the potential for Reproducibility, through the exact replication of experimental conditions, agent configurations, and environments across different studies and research groups.

3. Current State and Promising Developments

The vision of LLM agents as fully programmable subjects for rigorous scientific discovery is emergent, but recent advances demonstrate its growing technical feasibility. Systems like SALM (Social Agent-based Language Model;

Koley (

2025)) illustrate that LLM-driven multi-agent simulations can achieve unprecedented temporal stability (remaining stable beyond 4,000 timesteps) and computational efficiency (e.g., a 73

The broader landscape of LLM agent research (

Table 1) shows a burgeoning interest in creating agents that can plan, reason, interact, and utilize tools in increasingly complex settings. For instance, while systems like Generative Agents (

Park et al. 2023) achieve remarkable verisimilitude in simulated social behavior, their primary focus remains on the fidelity of the emergent social dynamics rather than a systematic investigation of the underlying LLM’s inherent traits through controlled manipulation of its core configuration as a programmable subject. Similarly, agent learning frameworks like Voyager (

Wang et al. 2023) impressively demonstrate open-ended skill acquisition; however, our proposed paradigm would complement this by seeking to understand how different base LLMs, when placed within such frameworks, might exhibit distinct inherent learning biases, exploration strategies, or emergent failure modes that are properties of the LLM architecture itself. Even work on enhancing agent reasoning and implicit alignment, such as Reflexion (

Shinn et al. 2023), which improves task robustness through verbal reinforcement, differs from our aim of a more foundational and explicit understanding of alignment. The "programmable subject" approach would systematically probe how an agent’s core programming, tool access, and environmental conditions lead to (mis)alignment, thereby revealing *why* certain corrective or reflective strategies are necessary for specific LLM types. Frameworks for multi-agent systems (e.g., (

Yang et al. 2023;

Zhang et al. 2023)) and specialized evaluation benchmarks (e.g., (

Liu et al. 2023;

Huang et al. 2023;

Zhou et al. 2023)) are also rapidly developing. While essential for assessing agent *performance* and capabilities, these benchmarks are not typically designed as *experimental laboratories* for the systematic *discovery and characterization of emergent inherent traits* of the LLMs themselves, nor for testing hypotheses about how LLM architecture and configuration influence these traits under a wide array of controlled conditions.

However, as

Table 1 suggests, while these current implementations and evaluations are promising for demonstrating general agentic capabilities or task performance, they do not typically adopt the "programmable subject" methodology with the explicit aim of systematically identifying inherent emergent traits of the LLMs themselves, or rigorously testing alignment under controlled variations of agent programming and environment. Most systems focus on what agents can do, rather than deeply characterizing what they are or how their underlying models lead to specific, potentially problematic, emergent tendencies. This gap underscores the need for the paradigm we propose. To realize the full potential of "programmable subjects" as reliable scientific instruments, particularly for identifying inherent traits and robustly testing alignment, significant methodological advances are still required from the machine learning community.

3.1. Case Study: Constraint Obedience in Tool-Enabled Coding

We outline a compact, falsifiable design to concretize the paradigm. Scenario: a coding agent with access to an execution tool and linter constraints. Design: a factorial over goal phrasing (strict/ambiguous/dual-objective), tool cost (0.0/0.05/0.10), and audit probability (0.0/0.3/0.8); three model families; five seeds. Metrics: violations per minute (primary), cost-normalized success, verifier-scored process alignment, stability indices (test–retest). Falsification: if obedience differences vanish under reliability/invariance tests, claims of inherent obedience are withdrawn.

3.2. Applicability to Human–AI Interaction

Programmable subjects are most reliable for prototyping negotiation partners, testing safety guardrails in mixed teams, and evaluating interface changes that affect tool use or plan quality. Prior work on human–agent multi-issue negotiation highlights the importance of adapting to human conflict modes

Koley and Rao (

2018); our assays provide standardized, process-level probes before deployment. They are not appropriate stand-ins for emotion-laden or high-stakes human judgments. We recommend sandboxing, rate limits, audit logs, and a red-team harness for any human-facing assay.

3.3. Evaluation Toolkit

To facilitate adoption, we provide an evaluation toolkit: (i) JSON schemas for subject configuration, protocols, logging, and leaderboard submissions; (ii) a validation CLI for schema conformance; (iii) a scoring CLI that implements assay metrics (e.g., calibration scores, search depth, invariance spans); and (iv) adapters and example harnesses (mock baseline and a SALM adapter) alongside a Colab quickstart. This toolkit standardizes process-level logging and enables comparable reporting across research groups.

4. Critical Limitations Requiring ML Innovation

Despite promising initial steps, several critical limitations currently hinder the widespread and reliable use of LLM agents as programmable subjects for deep scientific inquiry, especially for understanding inherent traits and ensuring model alignment. Addressing these necessitates significant innovation within the ML community. First, current LLMs, while proficient at pattern recognition and text generation, often lack a deep, grounded understanding of causal relationships. For example, recent work has shown that LLMs can struggle with the contextual interpretation necessary to identify subtle causal links or differentiate complex relational dynamics

Anonymous (

2025). This is crucial because, for an agent to be a valid subject in an experiment designed to understand generative processes, its actions should ideally stem from an understanding of cause and effect within its programmed model and environment. Instead, LLM agents might merely reproduce correlations observed in their vast training data or generate plausible but causally unsound behaviors, thereby undermining the scientific validity of experiments aimed at uncovering true emergent traits or mechanisms.

Second, the internal decision-making pathways of most large LLMs are highly opaque. This "black box" nature makes it extremely difficult to verify how or why an agent arrives at specific decisions. If the internal reasoning or decision-making pathways cannot be inspected and understood, researchers cannot confidently determine whether an observed emergent behavior or trait is a genuine consequence of the agent’s programmed goals and the experimental conditions, or an unpredictable artifact of the LLM’s internal workings. This lack of interpretability is a major barrier to using these agents for rigorous scientific discovery about their own inherent properties or for reliable alignment research.

Third, current methods for instilling specific behavioral traits, cognitive capabilities, or even consistent personalities into LLM agents often lack the necessary precision and reliability for controlled experimentation. While prompting can guide behavior to some extent, ensuring that a programmed characteristic (such as risk-aversion or cooperativeness) consistently and exclusively drives decision-making across diverse contexts and over extended periods remains an open challenge. Without this, it is difficult to isolate the effect of specific programmed traits on emergent behavior or to confidently identify traits as inherent versus contextually induced.

Finally, while the outcomes of simulations (such as task success rates or aggregate behaviors) can sometimes be validated against empirical data, directly validating the internal generative processes within LLM agents or the authenticity of observed emergent traits is far more complex. Methodologies are needed that go beyond outcome-matching to assess whether the simulated processes are plausible and whether an observed trait is a robust characteristic of the underlying model or merely an artifact of the specific experimental setup. This is particularly true for identifying subtle or undesirable emergent traits relevant to model alignment.

5. Related Work

Despite these advances, the systematic use of LLMs as programmable subjects for controlled scientific experimentation and alignment research remains an open and timely area for further investigation. Our work builds on these foundations and calls for a more rigorous, standardized approach to using LLM agents as digital experimental subjects.

Conventional agent-based models (ABM) employ hand-coded transition rules and objective functions, emphasizing outcome trajectories under designed mechanisms. By contrast, programmable subjects expose language-mediated policies, tool affordances, and memory as first-class experimental levers and emphasize process-trace evaluation. Prior LLM-agent labs and benchmarks primarily target task performance or ecological plausibility; our paradigm contributes (i) operational trait assays with reliability/invariance/causal criteria, (ii) verifier-scored process evaluation and strategy comparisons, and (iii) a reference lab API and logging standard for cross-group replication

Plaat et al. (

2025b);

Liu et al. (

2024).

6. A Research Agenda for Programmable Subjects

To transform LLM agents into reliable and insightful programmable subjects, particularly for understanding their emergent traits and advancing model alignment, the machine learning community must prioritize research in several interconnected areas. First, there is a need to develop LLM architectures and training methodologies that explicitly encourage agents to learn, represent, and reason about causal relationships within their environment, rather than relying solely on correlational patterns

Romera-Paredes et al. (

2023);

Bengio et al. (

2009);

Pearl (

2009);

Qiu et al. (

2023). Such developments are crucial for enhancing the scientific utility of programmable subjects. This includes training on data structured to highlight causal links and interventions, incorporating causal discovery algorithms or inductive biases into model architectures, and designing explicit causal modeling components that interface with the LLM’s generative capabilities, allowing for more grounded decision-making.

Second, advancing explainable AI (XAI) methods specifically for agentic LLMs is essential

Cobbe et al. (

2021);

Elhage et al. (

2022);

Gil et al. (

2022);

Madaan et al. (

2023). Researchers must be able to understand the step-by-step reasoning or decision-making processes of these agents. This includes methods for tracing decision pathways from programmed goals, constraints, and perceived environmental states to specific actions and tool use, as well as developing hybrid architectures that combine the flexibility of LLMs with more transparent or auditable symbolic reasoning modules for critical decision points. Tools for real-time inspection and logging of relevant internal states or attention patterns that contribute to decisions will facilitate the identification of emergent strategies or biases.

Third, robust techniques are needed for reliably instilling and controlling specific behavioral traits, cognitive capabilities, memories, and internal states in LLM agents

Shinn et al. (

2023);

Liu et al. (

2023);

Kambhampati et al. (

2024);

Majumder et al. (

2023). This involves researching methods beyond simple prompting, such as targeted fine-tuning, conditioning on explicit knowledge graphs, or architectural modifications that allow for more precise control over agent characteristics. Techniques for systematically varying these programmed generative factors will enable causal inference about their impact on behavior and the emergence of other traits, and frameworks for validating the successful and consistent implementation of these programmed traits across different contexts and time periods are needed.

Fourth, new methodologies are required to validate the simulated generative processes themselves and to reliably identify robust emergent traits, not just task outcomes

Trinh et al. (

2024);

Stanley et al. (

2017);

Zhang et al. (

2023);

Wolf et al. (

2023). This includes techniques for comparing simulated decision traces or behavioral sequences against established theories of decision-making or domain-specific process models, developing behavioral assays or standardized experimental protocols designed to elicit and measure specific emergent traits (such as cooperativeness, deceptiveness, risk-propensity, laziness, or diligence) across different LLMs and configurations, and interactive tools allowing domain scientists and alignment researchers to probe agent behaviors, test hypotheses about emergent traits, and iteratively refine experimental designs.

Finally, comprehensive ethical guidelines and technical safeguards must be established for the responsible design and use of programmable LLM subjects, especially in alignment research and studies of potentially sensitive behaviors

Touvron et al. (

2023);

Caliskan et al. (

2017);

Hendrycks et al. (

2020);

Callison-Burch (

2023);

Magnusson et al. (

2023). This includes methods for identifying and mitigating the influence of harmful biases in agent programming and emergent behavior, frameworks for the responsible interpretation and communication of results—particularly when inferring inherent traits of LLMs or potential real-world implications—and developing stress tests and adversarial environments to assess the robustness of agent behavior and the stability of their alignment under challenging or unexpected conditions.

6.1. Reproducibility Artifacts and Reference Lab

We propose a minimal reference laboratory comprising: (i) a subject configuration schema (model, prompts, memory, tools, goals, constraints), (ii) a protocol DSL for interventions and measurement, and (iii) a logging schema capturing actions, tool I/O, prompts, seeds, versions, and costs. We release a validation CLI for schema checks, a scoring CLI for computing assay metrics, a mock baseline harness, a SALM adapter for social environments, and a Colab quickstart. Each assay release includes reference configurations for multiple model families, seeds, and environments, and ships with anonymized logs to facilitate independent re-analysis

Liu et al. (

2024);

Zhang et al. (

2025);

Chen et al. (

2025).

7. Alternative Views

There are several important critiques of the programmable subject paradigm for LLMs. Some scholars argue that LLMs, as fundamentally pattern-matching systems trained on vast correlational data, are inherently unsuited to serve as reliable scientific instruments for discovering causal mechanisms or "inherent" model traits

Pearl (

2009);

Anderson (

2008);

Marcus (

2022);

Lake et al. (

2017). They contend that any observed "emergent behaviors" are merely complex artifacts of the training data and experimental setup, rather than authentic representations of underlying generative processes or stable characteristics of the model itself. This perspective is supported by work highlighting the limitations of current deep learning approaches in achieving genuine causal understanding or robust generalization

Bengio et al. (

2009);

Pearl (

2009);

Lake et al. (

2017).

The inherent opacity of LLMs—the so-called "black box" problem—presents another significant concern

Rudin (

2019);

Doshi-Velez and Kim (

2017);

Lipton (

2018). Skeptics argue that the requirements for interpretability and validation of internal decision-making pathways, as proposed in our research agenda, are so substantial and technically challenging as to render the programmable subject approach impractical or even unattainable with current or foreseeable LLM technology. This has led some to favor more traditional, transparent modeling techniques, such as explicitly coded agent-based models

Bonabeau (

2002);

Gilbert and Troitzsch (

2005), or direct empirical investigation with human subjects, despite the respective limitations of those methods.

Ethical concerns are also frequently raised regarding the potential for misinterpretation of simulation results, or the creation of agents that convincingly mimic human processes without any true underlying understanding or intent

Caliskan et al. (

2017);

Bommasani et al. (

2022);

Bender et al. (

2021). The very idea of identifying "inherent traits" in LLMs could be seen as anthropomorphizing these systems to a problematic degree, potentially leading to flawed conclusions about their nature and capabilities.

While these concerns are valid and highlight significant hurdles, they also underscore precisely why a dedicated research program by the machine learning community, focused on the areas outlined in this paper, is so crucial. The limitations of current LLMs are not necessarily terminal flaws for this paradigm but rather define the frontiers of ML research needed to overcome them. The goal is not to naively accept current LLM outputs as direct reflections of reality or to claim they possess human-like consciousness, but to develop the rigorous methodologies—in causal reasoning, interpretability, precise behavioral control, and robust validation—that can transform LLMs into scientifically useful and understandable experimental tools. The challenge of understanding the emergent properties and failure modes of complex AI systems, particularly those intended for agentic roles, is immense. The programmable subject framework offers a structured, empirical approach to tackling this challenge, provided the ML community invests in making these subjects and the laboratories they inhabit suitable for rigorous scientific endeavor. The alternative of not pursuing this path may mean missing a unique opportunity to develop powerful tools for understanding both the capabilities and the risks of advanced AI.