Submitted:

05 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Background

Objectives

Methods

Protocol Design

Stage 1: Identifying the Research Question

- Tabletop exercises: A tabletop exercise (TTX or TTE) is a low-stress, discussion-based session where team members walk through emergency scenarios to explore their roles and responses. Unlike functional or full-scale exercises, TTXs are informal and held in a collegial setting, focusing on dialogue and decision-making rather than real-time action. Participants respond to scenario prompts based on their organization's emergency plans [16].

- Prehospital emergency medicine: Prehospital emergency medicine (PHEM), also known as EMS medicine or prehospital care, is a medical subspecialty focused on treating critically ill or injured patients before they arrive at the hospital or during emergency transfers. It is practiced by doctors from fields like emergency medicine, anesthesiology, intensive care, or acute medicine after completing their core specialty training [17].

- Disaster preparedness: Disaster preparedness involves actions and strategies designed to reduce the impact of events like floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, and other emergencies on individuals, communities, and organizations. It includes developing emergency plans, assembling disaster-specific kits, managing essential supplies, and carrying out regular training and drills [18].

- Mass casualty incident (MCI): A mass casualty incident (MCI) refers to a situation where the number and severity of casualties exceed the capacity of available emergency medical services, including personnel and equipment. For instance, a small rural clinic facing an influx of patients after a nearby factory explosion may be considered an MCI. More widely recognized examples include large-scale emergencies like earthquakes, plane crashes, building collapses, and major transportation accidents [19].

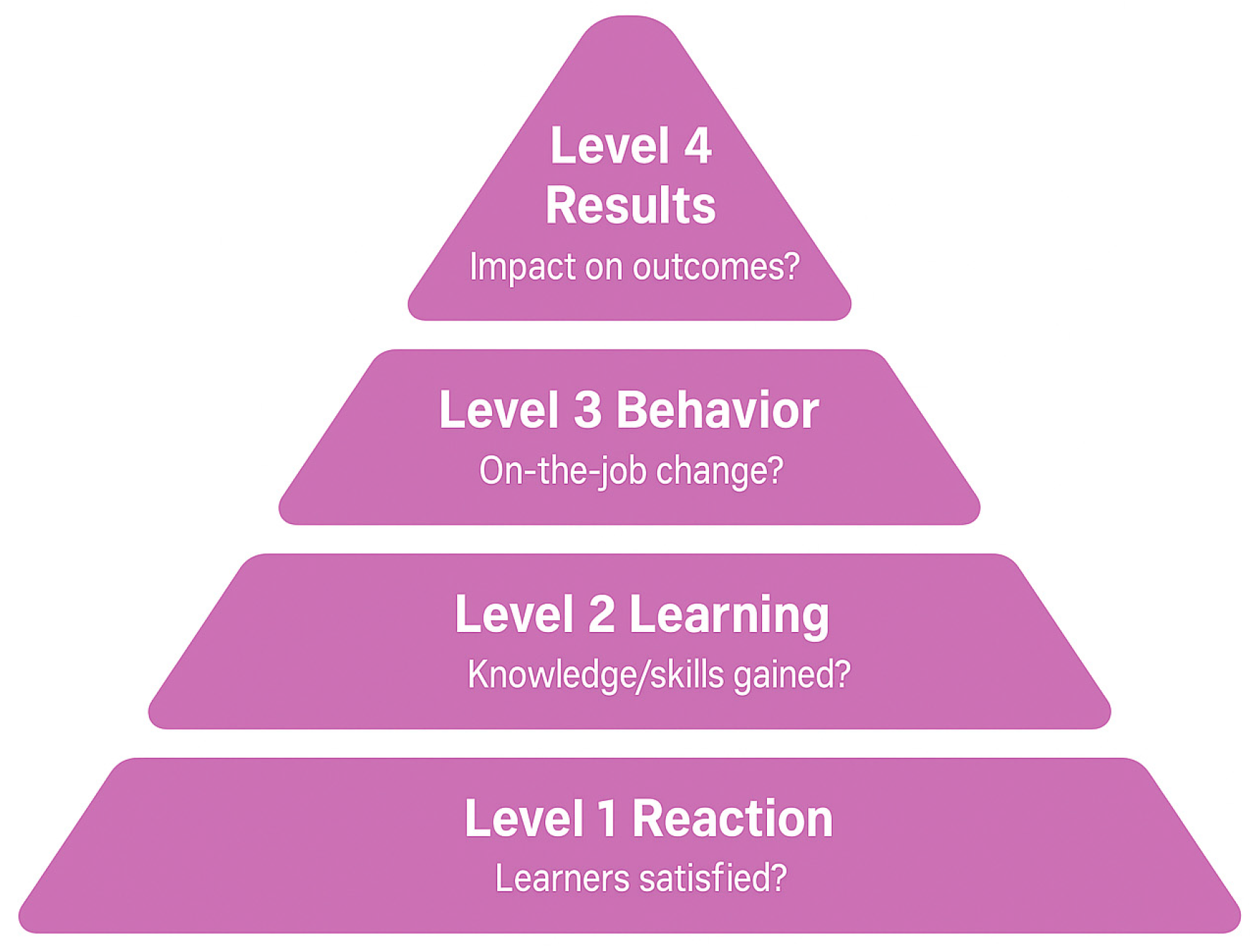

- Kirkpatrick’s model: The Kirkpatrick Model, introduced by Dr. Donald Kirkpatrick in 1959, is one of the most widely used frameworks for evaluating training effectiveness. It breaks down evaluation into four key levels to assess impact and outcomes:

Research Questions

- In what ways have tabletop exercises (TTXs) been used to assess or enhance prehospital preparedness during emergencies?

- Have these TTXs been implemented in the context of disaster response, routine emergency preparedness, or non-disaster scenarios?

- Were they conducted as interprofessional education (IPE) exercises or within a single-discipline framework?

- Did any of the exercises incorporate game-based or board-game elements?

- What outcomes have been reported from studies using TTXs in prehospital emergency preparedness, based on the Kirkpatrick Model of training evaluation?

- Which levels of the model (Reaction, Learning, Behavior, Results) are most frequently addressed?

- Are certain outcome levels underrepresented in the current literature?

- What are the key characteristics of studies using TTXs in prehospital settings? (This includes the design, setting, participant groups, and interventions used in each study).

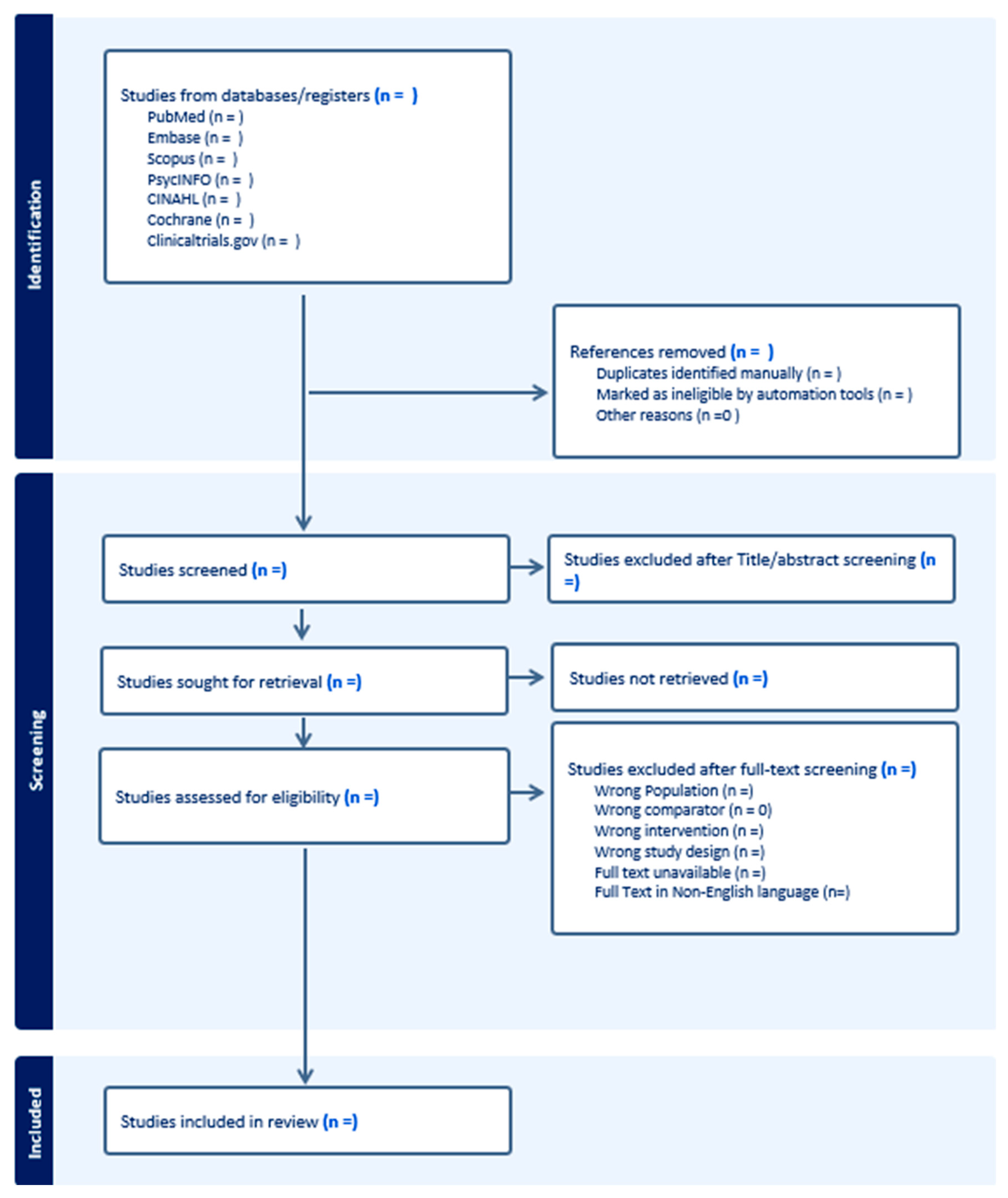

Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

- PubMed – for peer-reviewed research in biomedical and life sciences

- Embase – for extensive biomedical literature, including European and Asian sources

- Scopus – for a wide array of scientific, technical, and medical publications

- PsycINFO (via APA PsycNet) – for literature focused on psychological aspects of training and education

- CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) – for research in nursing and allied health professions

- Cochrane Library – for systematic reviews and evidence from clinical trials

- Google Scholar – to identify additional academic and non-academic literature.

- ClinicalTrials.gov – to review any registered clinical trials related to tabletop exercises or emergency preparedness.

Stage 3: Study Selection

- Population: First responders, EMS personnel, paramedics, ambulance teams, disaster response teams, and healthcare trainees (students, interns, residents, physicians) involved in prehospital tabletop exercises.

- Setting: Academic, clinical, field-based, or professional training environments focused on prehospital emergency preparedness.

- Intervention: Use of tabletop exercises (TTXs) either as a stand-alone activity or part of a multicomponent intervention (e.g., combined with simulation, lectures, or workshops).

- Outcomes: Studies may report on TTXs addressing prehospital planning, triage, response coordination, or decision-making in simulated emergencies or disaster scenarios, and at least one learning outcome from the Kirkpatrick Model.

- Study Design: Qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods studies, commentaries, pedagogical descriptions, and conference proceedings.

- Studies published in English, with a restriction on publication year to the last 10 years.

- Studies that focus solely on in-hospital preparedness or do not address the prehospital phase of emergency response.

- Articles that do not involve tabletop exercises as a central component of the intervention.

- Systematic reviews, Literature reviews, and other scoping reviews.

- Full text not available

Stage 4: Data Charting

Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

- Study focus and objectives

- Educational or training context

- Target populations (e.g., EMS personnel, paramedics, first responders)

- TTX characteristics (e.g., format, setting, disaster type)

- Outcomes reported, categorized using the Kirkpatrick Model

Stage 6: Stakeholder Consultation (Optional Stage)

Limitations

Ethics and Dissemination

Ethical Considerations

Dissemination Strategy

- World Association for Disaster and Emergency Medicine (WADEM)

- International Conference on Emergency Medicine (ICEM)

- National EMS conferences and simulation-based training events

- Emergency medical services (EMS) organizations

- Disaster response agencies

- Simulation centers

- Prehospital training institutions

Project Timeline

| Stage | Duration | Weeks |

| Planning & Protocol Development | 4 weeks | Weeks 1–4 |

| - Team meetings & protocol drafting | ||

| - Protocol registration (e.g., OSF) | ||

| Literature Search | 3 weeks | Weeks 5–7 |

| - Finalize and conduct search | ||

| - Gray literature and manual search | ||

| Study Selection | 6 weeks | Weeks 8–13 |

| - Title/abstract screening | ||

| - Full-text screening | ||

| Data Charting | 4 weeks | Weeks 14–17 |

| - Pilot and finalize the charting form | ||

| - Extract data from included studies | ||

| Analysis & Synthesis | 6 weeks | Weeks 18–23 |

| - Thematic and descriptive analysis | ||

| - Identify trends, gaps, and insights | ||

| Report Writing | 4 weeks | Weeks 24–27 |

| - Draft, review, and finalize manuscript | ||

| Dissemination Activities | 5+ weeks | Weeks 28–32+ |

| - Prepare journal submission | ||

| - Presentations, briefs, stakeholder outreach |

- Weekly team meetings to monitor progress

- Buffer time built into each phase to accommodate unforeseen delays

- Dissemination activities may continue beyond Week 32 due to conference and stakeholder engagement schedules

Support/Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Acknowledgments

References

- Bissmeyer, H.; Gallegos, C.; Randazzo, S.; Scheffler, C.; Sullivan Lee, L.; Powell, L. Tabletop Simulation as an Innovative Tool for Clinical Workflow Testing. Nursing Administration Quarterly 2025, 49, E1–E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro Delgado, R.; Fernández García, L.; Cernuda Martínez, J.A.; Cuartas Álvarez, T.; Arcos González, P. Training of Medical Students for Mass Casualty Incidents Using Table-Top Gamification. Disaster med. public health prep. 2023, 17, e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guideline-for-Innovative-Tabletop-Simulation.pdf.

- Torpan, S.; Orru, K.; Hansson, S.; Klaos, M. Using a table-top exercise to identify communication-related vulnerability to disasters. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2025, 119, 105264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emaliyawati, E.; Ibrahim, K.; Trisyani, Y.; Nuraeni, A.; Sugiharto, F.; Miladi, Q.; Abdillah, H.; Christina, M.; Setiawan, D.; Sutini, T. Enhancing Disaster Preparedness Through Tabletop Disaster Exercises: A Scoping Review of Benefits for Health Workers and Students. AMEP 2025, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutiarasari, D.; Zulkifli, A.; Rivai, F.; Thamrin, Y.; Mallongi, A.; Miranti, M. The Effectiveness Of Table-Top Exercise Simulation For Hospital Disaster Preparedness Training A Systematic Review. J Neonatal Surg 2025, 14, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khirekar, J.; Badge, A.; Bandre, G.R.; Shahu, S. Disaster Preparedness in Hospitals. Cureus 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sena, A.; Forde, F.; Yu, C.; Sule, H.; Masters, M.M. Disaster Preparedness Training for Emergency Medicine Residents Using a Tabletop Exercise. MedEdPORTAL 2021, 11119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, W.-K.; Cheng, M.-T.; Lin, C.-H. Teaching mass casualty incident management to senior medical students by three-dimensional tabletop exercise without lecture. BMC Med Educ 2025, 25, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alakrawi, G.A.; Al-Wathinani, A.M.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Alobaid, A.M.; Abahussian, M.; Alhazmi, R.; Mobrad, A.; Jebreel, A.; Althunayyan, S.; Goniewicz, K. Evaluating the efficacy of full-scale and tabletop exercises in enhancing paramedic preparedness for external disasters: A quasi-experimental study. Medicine 2024, 103, e40777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frégeau, A.; Vinette, B.; Lapierre, A.; Maheu-Cadotte, M.-A.; Fontaine, G.; Castonguay, V.; Flores-Soto, R.; Garceau-Tremblay, Z.; Blais, S.; Vigneault, L.-P.; et al. Tabletop Simulations in Medical Emergencies: A Scoping Review. Sim Healthcare 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazim, M.; Prashanth, P.; Narayanan, D.; Elmisbah, S.A.; Zary, N.; Hubloue, I.; Omayer, A.; Yousif, A.; AlRahma, A. Tabletop Exercises for Prehospital Preparedness During Emergencies: A Scoping review protocol. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Fathoni, M.; Yueniwati Prabowowati Wadjib, Y.; Addiarto, W. The Effect of Learning Tabletop Disaster Exercise (TDE) to Improve Knowledge among Nursing Students for Disaster Emergency Response. RJLS 2019, 6, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.H.; Habig, K.; Wright, C.; Hughes, A.; Davies, G.; Imray, C.H.E. Pre-hospital emergency medicine. The Lancet 2015, 386, 2526–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disaster Preparedness: A Guide. Available online: https://safetyculture.com/topics/disaster-preparedness/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- World Health Organization Mass casualty management systems : Strategies and guidelines for building health sector capacity. 2007, 34.

- Falletta, S. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels Donald L. Kirkpatrick, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco, CA, 1996, 229 pp. The American Journal of Evaluation 1998, 19, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org.

| Population | Concept | Context |

| paramedic* | tabletop exercise* | emergency preparedness |

| first responder* | table-top exercise* | disaster preparedness |

| ambulance* | Table top exercise* | mass casualty incident* |

| emergency medical services | tabletop simulation* | MCI |

| EMS | discussion-based exercise* | field triage |

| prehospital | discussion based simulation* | incident command |

| tabletop | prehospital care | |

| tabletop drill* | disaster simulation | |

| preparedness exercise* | response coordination | |

| board game* | "Mass Casualty Incidents"[Mesh] | |

| simulation game* | ||

| scenario-based simulation* | ||

| "Computer Simulation"[Mesh] | ||

| "Gamified exercise" |

| Database | Search strategy | |

| PubMed | ((paramedic* OR "first responder" OR "first responders" OR ambulance* OR "emergency medical services" OR "emergency medical service" OR "EMS" OR "prehospital") AND ("Computer Simulation"[Mesh] OR "gamified exercise" OR "tabletop exercise" OR "tabletop exercises" OR "table-top exercise" OR "table-top exercises" OR "table top exercise" OR "table top exercises" OR "tabletop simulation" OR "tabletop simulations" OR "tabletop" OR "tabletop drills" OR "preparedness exercise" OR "preparedness exercises" OR "board game" OR "board games" OR "simulation game" OR "simulation games" OR "scenario-based simulation" OR "scenario-based simulations")) AND ("emergency preparedness" OR "disaster preparedness" OR "mass casualty incidents" OR "mass casualty incident" OR "MCI" OR "field triage" OR "incident command" OR "prehospital care" OR "disaster simulation" OR "response coordination" OR crisis OR "Mass Casualty Incidents"[Mesh]) AND (y_10[Filter]) | |

| Scopus | ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( paramedic* OR "first responder*" OR ambulance* OR "emergency medical service*" OR ems OR prehospital ) ) AND ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "tabletop exercise*" OR "table top exercise*" OR "tabletop simulation*" OR "discussion based simulation*" OR "gamified exercise" OR tabletop OR "tabletop drill*" OR "preparedness exercise*" OR "board game*" OR "simulation game*" OR "scenario based simulation*" ) ) AND ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "emergency preparedness" OR "disaster preparedness" OR "mass casualty incident*" OR mci OR "field triage" OR "incident command" OR "prehospital care" OR "disaster simulation" OR "response coordination" ) ) AND PUBYEAR > 2014 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 | |

| Embase | #23 | #22 AND (2015:py OR 2016:py OR 2017:py OR 2018:py OR 2019:py OR 2020:py OR 2021:py OR 2022:py OR 2023:py OR 2024:py OR 2025:py) |

| #22 | #6 AND #12 AND #21 | |

| #21 | #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 | |

| #20 | 'prehospital care' | |

| #19 | 'incident command' | |

| #18 | 'field triage' | |

| #17 | 'mass casualty incident' | |

| #16 | 'mass disaster' | |

| #15 | 'mass disaster' | |

| #14 | 'disaster preparedness' | |

| #13 | 'emergency preparedness' | |

| #12 | #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 | |

| #11 | 'tabletop exercise' | |

| #10 | 'tabletop simulation' | |

| #9 | tabletop | |

| #8 | 'simulation based medical education' | |

| #7 | 'simulation training' | |

| #6 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 | |

| #5 | 'prehospital time' | |

| #4 | 'emergency health service' | |

| #3 | 'ambulance' | |

| #2 | 'first responder (person)' | |

| #1 | 'paramedical personnel'/exp OR 'paramedical personnel' | |

|

PsycNET |

((Any Field: (paramedic*)) OR (Any Field: (first responder*)) OR (Any Field: (ambulance*)) OR (Any Field: (emergency medical services)) OR (Any Field: (EMS)) OR (Any Field: (prehospital))) AND ((Any Field: (tabletop exercise*)) OR (Any Field: (table-top exercise*)) OR (Any Field: (table top exercise*)) OR (Any Field: (tabletop simulation*)) OR (Any Field: (discussion-based exercise*)) OR (Any Field: (discussion based simulation*)) OR (Any Field: (tabletop)) OR (Any Field: (tabletop drill*)) OR (Any Field: (preparedness exercise*)) OR (Any Field: (board game*)) OR (Any Field: (simulation game*)) OR (Any Field: (scenario-based simulation*))) AND ((Any Field: (emergency preparedness)) OR (Any Field: (disaster preparedness)) OR (Any Field: (mass casualty incident*)) OR (Any Field: (MCI)) OR (Any Field: (field triage)) OR (Any Field: (incident command)) OR (Any Field: (prehospital care)) OR (Any Field: (disaster simulation)) OR (Any Field: (response coordination))) AND Year: 2015 To 2025 | |

| CINAHL | (paramedic* OR "first responder*" OR ambulance* OR "emergency medical service*" OR ems OR prehospital ) AND ("tabletop exercise*" OR "table top exercise*" OR "tabletop simulation*" OR "discussion based simulation*" OR tabletop OR "gamified exercise" OR "tabletop drill*" OR "preparedness exercise*" OR "board game*" OR "simulation game*" OR "scenario based simulation*" ) AND ("emergency preparedness" OR "disaster preparedness" OR "mass casualty incident*" OR mci OR "field triage" OR "incident command" OR "prehospital care" OR "disaster simulation" OR "response coordination" ) Filter: Last 10 years |

|

| Cochrane | paramedic* OR "first responder" OR "first responders" OR ambulance* OR "emergency medical service" OR "emergency medical services" OR ems OR prehospital in Title Abstract Keyword AND "tabletop exercise" OR "tabletop exercises" OR "table-top exercise" OR "table-top exercises" OR "table top exercise" OR "table top exercises" OR "tabletop simulation" OR "tabletop simulations" OR "gamified exercise" OR "tabletop" OR "tabletop drills" OR "preparedness exercise" OR "preparedness exercises" OR "board game" OR "board games" OR "simulation game" OR "simulation games" OR "scenario-based simulation" OR "scenario-based simulations" in Title Abstract Keyword AND "emergency preparedness" OR "disaster preparedness" OR "mass casualty incidents" OR "mass casualty incident" OR "MCI" OR "field triage" OR "incident command" OR "prehospital care" OR "disaster simulation" OR "response coordination" in Title Abstract Keyword | |

| Clinicaltrials.gov | (paramedic* OR "first responder" OR "first responders" OR ambulance* OR "emergency medical service" OR "emergency medical services" OR ems OR prehospital) AND ("tabletop exercise" OR "tabletop exercises" OR "table-top exercise" OR "table-top exercises" OR "table top exercise" OR "table top exercises" OR "tabletop simulation" OR "tabletop simulations" OR "gamified exercise" OR "tabletop" OR "tabletop drills" OR "preparedness exercise" OR "preparedness exercises" OR "board game" OR "board games" OR "simulation game" OR "simulation games" OR "scenario-based simulation" OR "scenario-based simulations") AND ("emergency preparedness" OR "disaster preparedness" OR "mass casualty incidents" OR "mass casualty incident" OR "MCI" OR "field triage" OR "incident command" OR "prehospital care" OR "disaster simulation" OR "response coordination") | |

| Field | Description |

| Study ID | Last name of author and year of publication. |

| Country | The country where the study was conducted. |

| Study design | Type of study (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, case study, commentary). |

| Population type | Description of participants (e.g., EMS personnel, paramedics, medical students). |

| Sample size | Number of participants included in the study. |

| Training setting | Context of delivery (e.g., university, EMS training center, hospital, field exercise). |

| Interprofessional involvement | Was the exercise interprofessional? (Yes/No/Not specified). |

| Exercise objectives | Specific goals or learning outcomes that the tabletop exercise aimed to achieve. |

| TTX description | Summary of how the tabletop exercise was designed and conducted (duration, modality, number of scenarios, etc.). |

| Number of scenarios | Total number of distinct emergency scenarios used during the exercise. |

| Duration of exercise | Total time (in minutes or hours) allocated for the tabletop exercise. |

| Pre-Exercise Lecture | Indicate whether a formal briefing or instructional session was provided before the TTX. |

| Pre-TTX Evaluation | Whether an assessment was conducted before the tabletop (e.g., baseline knowledge, readiness survey). |

| Supplementary resources | Any materials provided before the exercise (e.g., readings, protocols, guidelines). |

| Subject matter experts' availability | Whether content experts (e.g., EMS leaders, disaster planners) were involved in designing the TTX. |

| Support team availability | Presence of facilitators, coordinators, or technical support teams during the exercise. |

| Disaster type | Type of emergency simulated (e.g., MCI, pandemic, natural disaster, CBRN). |

| Real-world alignment | Whether the scenarios and responses were based on actual or likely local incidents. |

| Debriefing | Indicate if and how a structured debriefing was conducted post-exercise. |

| Post-TTX evaluation | Whether a follow-up assessment was conducted to measure impact (e.g., post-test, survey, reflection). |

| Comparator | If a comparison was made (e.g., FSE, lecture-based training), describe the comparator. |

| Measurement tools | Instruments or methods used to assess outcomes (e.g., surveys, pre/post-tests, observation checklists). |

| Self-reported measures | Subjective feedback from participants (e.g., confidence, satisfaction, perceived preparedness). |

| Outcomes assessed | Learning or performance outcomes were evaluated in the study. |

| Frameworks used during the exercise | Disaster frameworks or operational models guiding the exercise (e.g., ICS, NIMS, START triage, and WHO frameworks). |

| Frameworks used while designing or assessing the training | Instructional/educational design frameworks used (e.g., ADDIE model, Kern’s 6-step approach, Bloom’s taxonomy, Kirkpatrick’s model). |

| Kirkpatrick level | Outcome level according to the Kirkpatrick Model (Reaction, Learning, Behavior, Results). |

| Main findings | Summary of the key results. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).