Submitted:

05 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Material (Manufacturer Data) [71]

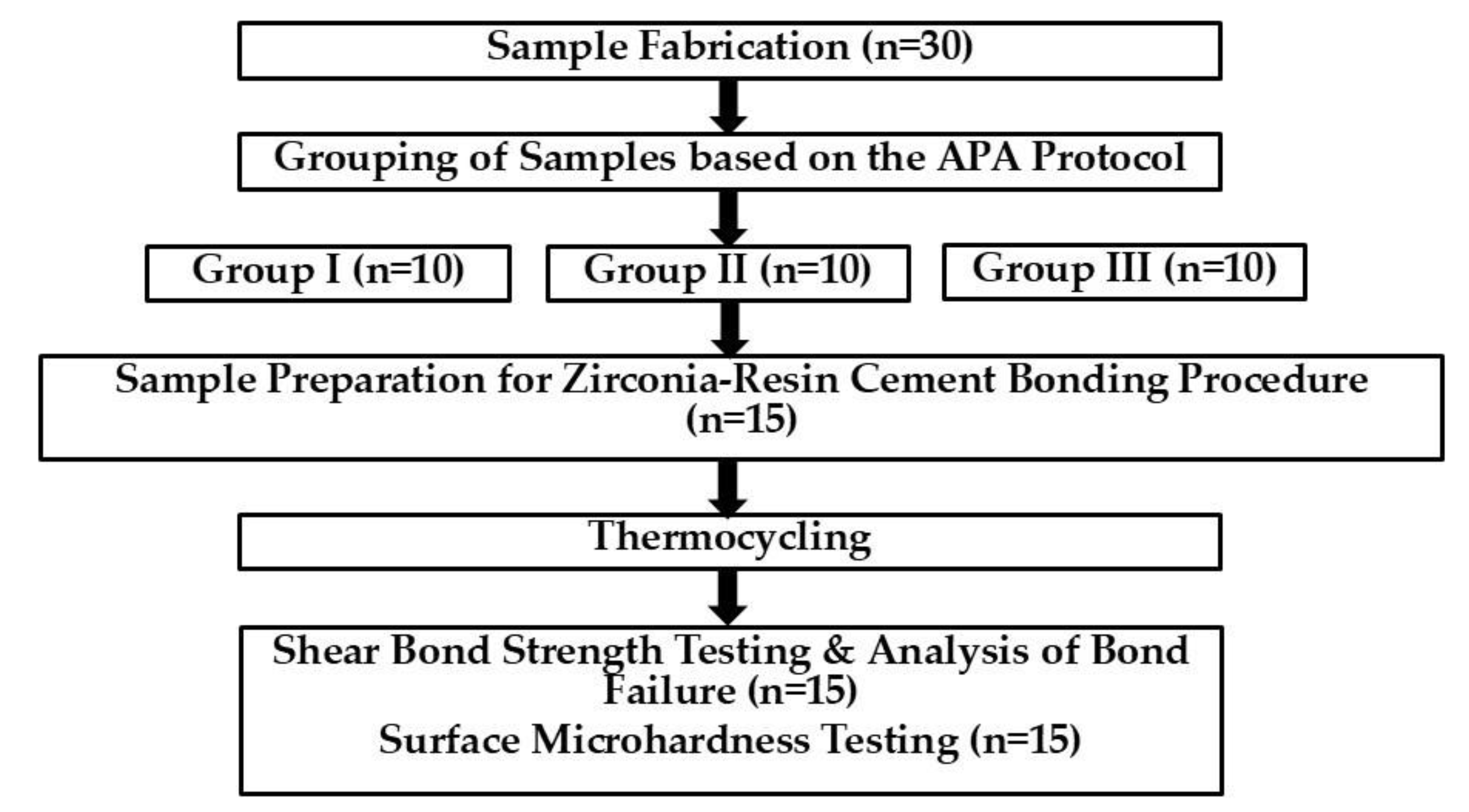

2.2. Experimental Workflow

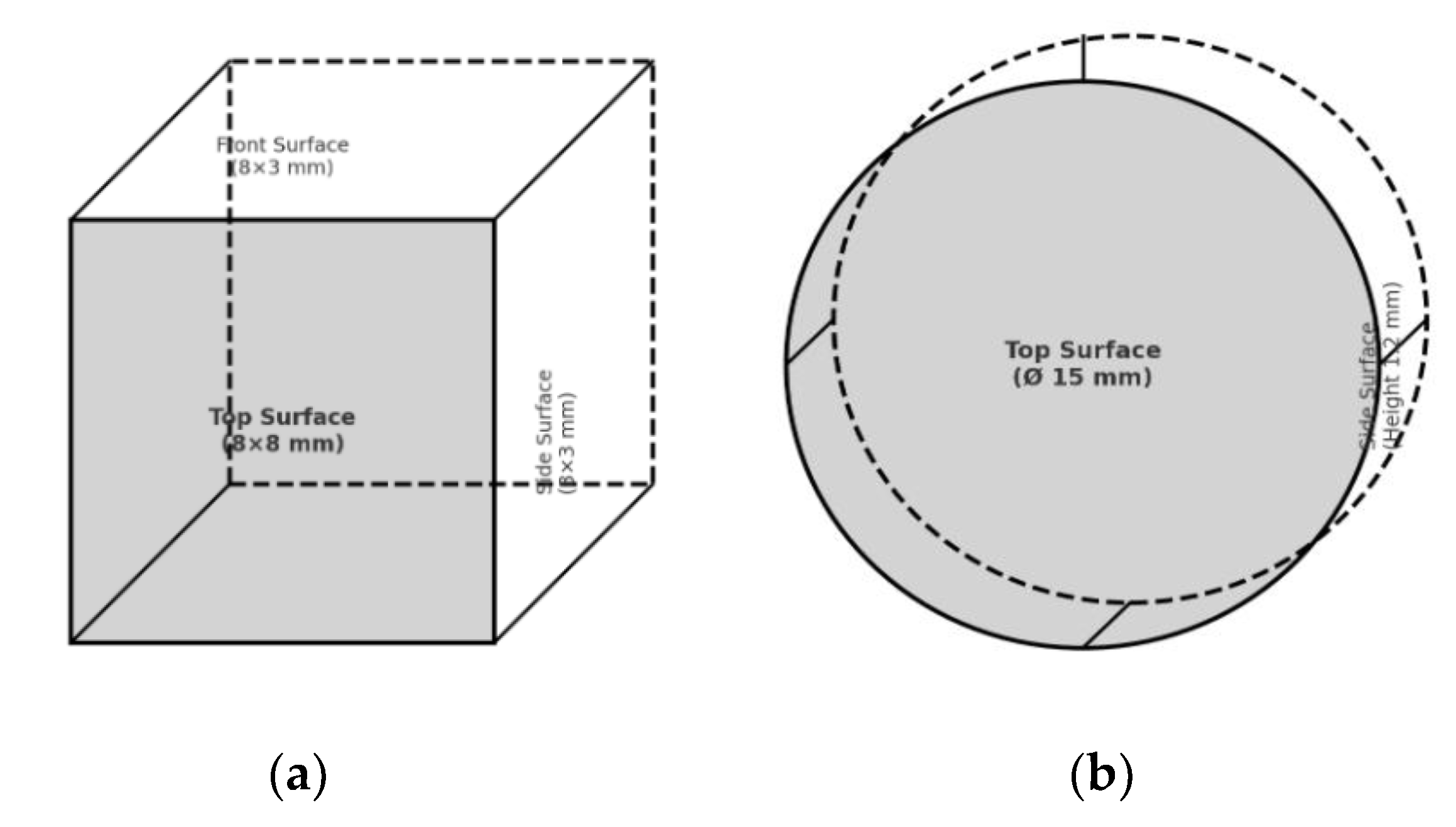

2.3. Sample Fabrication

2.4. Grouping of Samples based on the APA Protocol

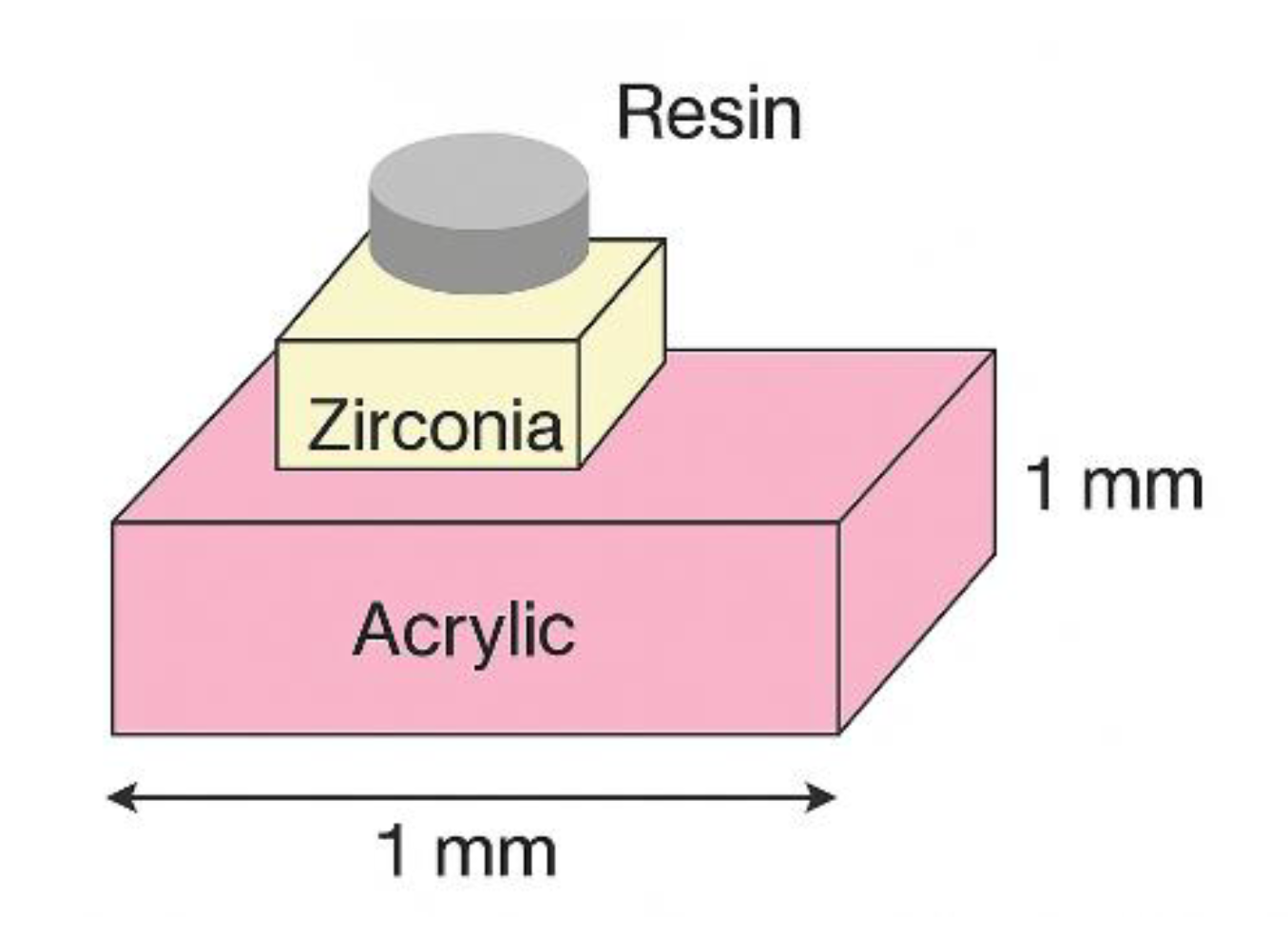

2.5. Sample Preparation for Zirconia-Resin Cement Bonding Procedure

2.6. Thermocycling

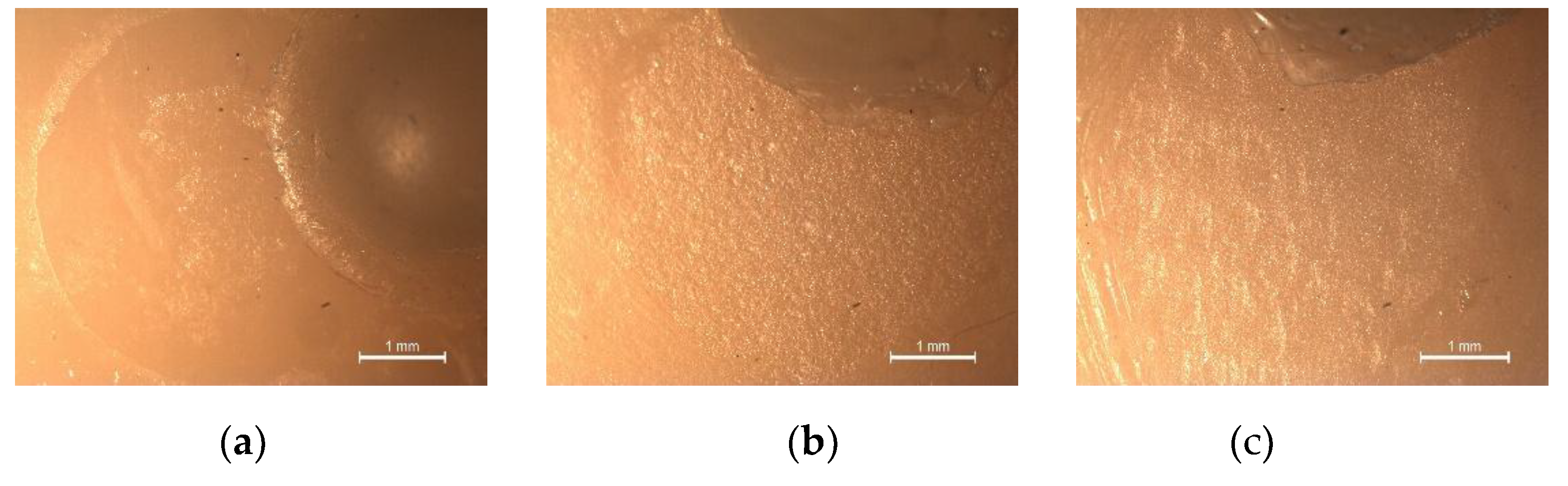

2.7. Shear Bond Strength Testing and Analysis of Bond Failure

2.8. Surface Microhardness Testing

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Shear Bond Strength

3.2. Surface Hardness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Airborne particle abrasion did not improve the shear bond strength, and all failure modes between the dual-cure resin cement and high-translucent zirconia were adhesive, indicating a limited benefit for resin bonding.

- Airborne particle abrasion improves the surface hardness of high-translucent zirconia, particularly with 50 µm Al₂O₃ producing the greatest effect.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ZrO2 | Zirconium Oxide |

| CAD-CAM | Computer-Aided Design and Computer-Aided Manufacturing |

| Y₂O₃ | Yttrium Oxide |

| 3Y-TZP | 3 mol% Yttria-stabilized Tetragonal Zirconia Polycrystal |

| Al₂O₃ | Aluminium Oxide |

| 4Y-PSZ | 4 mol% Yttria-Partially Stabilized Zirconia |

| 5Y-PSZ | 5 mol% Yttria-Partially Stabilized Zirconia |

| LTD | Low Temperature Degradation |

| APA | Airborne Particle Abrasion |

| ZSAT | Zirconia Surface Architecturing Technique |

| 10-MDP | 10-Methacryloyloxydecyl Dihydrogen Phosphate |

| SBS | Shear Bond Strength |

| SH | Surface Hardness |

| Ni-Cr | Nickel-Chromium |

| H₀ | Null hypothesis |

| Hₐ | Alternative hypothesis |

| UDMA | Urethane Dimethacrylate |

| TEGDMA | Triethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate |

| AET | Acryloxyethyltrimellitic Acid |

| HEMA | Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate |

| MHPA | Methacryloyloxyhexyl Phosphonoacetate |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| P | Probability |

| VHN | Vickers Hardness Number |

| t→m | tetragonal→monoclinic |

References

- Hussien, Z.Y.; Moften, A.Q.; Abdulrehman, M.A. Review of zirconia (ZrO₂) biomedical applications: Advanced manufacturing techniques and materials properties. Revue des Composites et des Matériaux Avancés 2025, 35, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapat, R.A.; Yang, H.J.; Chaubal, T.V.; Dharmadhikari, S.; Abdulla, A.M.; Arora, S.; Rawal, S.; Kesharwani, P. Review on synthesis, properties and multifarious therapeutic applications of nanostructured zirconia in dentistry. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 12773–12793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarshanan, A.; Kurian, B.P.; Joseph, A.M. CAD–CAM technology and its application in prosthodontics: An overview. Malanadu Dental Journal 2018, 7(3), 226–233. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, A.M.; Aldhuwayhi, S.D.; Mustafa, M.Z.; Deeban, Y.; Thakare, A.A.; Joseph, A. Fingernail form as a post-extraction guide for selecting the maxillary central incisor tooth form in the Saudi Arabian population: A novel application of CAD software. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2023, 26(8), 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karapetyan, H. The use of zirconium dioxide in dentistry and oral implantology: Narrative review. Bull. Stomatol. Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 21(2), 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, L.; Grădinaru, M.; Rîcă, R.; Mărășescu, P.; Stan, M.; Manolea, H.; Ionescu, A.; Moraru, I. Zirconia Use in Dentistry—Manufacturing and Properties. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2019, 45(1), 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.S.; Musani, S.; Madanshetty, P.; Shaikh, T.; Shaikh, M.; Lal, Q. A Study of the Antagonist Tooth Wear, Hardness, and Fracture Toughness of Three Different Generations of Zirconia. World J. Dent. 2023, 14(8), 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, S.; Fujita, T.; Fujisawa, M. Zirconia in fixed prosthodontics: A review of the literature. Odontology 2025, 113(2), 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzic, C.; Rominu, M.; Pricop, A.; Urechescu, H.; Pricop, M.O.; Rotar, R.; Cuzic, O.S.; Sinescu, C.; Jivanescu, A. Clinician’s Guide to Material Selection for All-Ceramics in Modern Digital Dentistry. Materials 2025, 18(10), 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Schmidt, F.; Beuer, F.; Yassine, J.; Hey, J.; Prause, E. Effect of surface treatment strategies on bond strength of additively and subtractively manufactured hybrid materials for permanent crowns. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28(7), 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amari, A.S.; Saleh, M.S.; Albadah, A.A.; Almousa, A.A.; Mahjoub, W.K.; Al-Otaibi, R.M.; Alanazi, E.M.; Alshammari, A.K.; Malki, A.T.; Alghelaiqah, K.F.; Akbar, L.F. A Comprehensive Review of Techniques for Enhancing Zirconia Bond Strength: Current Approaches and Emerging Innovations. Cureus 2024, 16(10), e70893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, S. Classification and Properties of Dental Zirconia as Implant Fixtures and Superstructures. Materials 2021, 14(17), 4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toksoy, D.; Önöral, Ö. Optical Behavior of Zirconia Generations. Cyprus J. Med. Sci. 2024, 9(6), 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawarczyk, B.; Keul, C.; Eichberger, M.; Figge, D.; Edelhoff, D.; Lümkemann, N. Three Generations of Zirconia: From Veneered to Monolithic. Part I. Quintessence Int. 2017, 48(5), 369–380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pizzolatto, G.; Borba, M. Optical Properties of New Zirconia-Based Dental Ceramics: Literature Review. Cerâmica 2021, 67(383), 338–343.

- Zhang, F.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Vleugels, J. Importance of Tetragonal Phase in High-Translucent Partially Stabilized Zirconia for Dental Restorations. Dent. Mater. 2020, 36(4), 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerman, E.; Lümkemann, N.; Eichberger, M.; Zoller, C.; Nothelfer, S.; Kienle, A.; Stawarczyk, B. Evaluation of translucency, Martens’s hardness, biaxial flexural strength and fracture toughness of 3Y-TZP, 4Y-TZP and 5Y-TZP materials. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37(2), 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manziuc, M.-M.; Gasparik, C.; Negucioiu, M.; Constantiniuc, M.; Burde, A.; Vlas, I.; Dudea, D. Optical properties of translucent zirconia: A review of the literature. EuroBiotech J. 2019, 3(1), 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousry, M.; Hammad, I.; Halawani, M.E.; Aboushelib, M. Translucency of recent zirconia materials and material-related variables affecting their translucency: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24(1), 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, A.; Rodrigues, S.J.; Mahesh, M.; Ginjupalli, K.; Shetty, T.; Pai, U.Y.; Saldanha, S.; Hegde, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Kamath, V.; Bajantri, P.; Srikant, N.; Kotian, R. Effect of different surface treatments on the micro-shear bond strength and surface characteristics of zirconia: An in vitro study. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 1546802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieniak, D.; Walczak, A.; Walczak, M.; Przystupa, K.; Niewczas, A.M. Hardness and wear resistance of dental biomedical nanomaterials in a humid environment with non-stationary temperatures. Materials 2020, 13(5), 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesar, P.F.; Miranda, R.B.P.; Santos, K.F.; Scherrer, S.S.; Zhang, Y. Recent advances in dental zirconia: 15 years of material and processing evolution. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40(5), 824–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, K.; Hao, Z.; Dou, R.; Zhu, F.; Gao, Y. Fracture toughness and subcritical crack growth analysis of high-translucent zirconia prepared by stereolithography-based additive manufacturing. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2025, 164, 106917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, Y.; Chen, K.; Jiang, Y.; Swain, M.V.; Yao, M.; He, Y.; Liang, Y.; Jian, Y.; Zhao, K. Effect of low-temperature degradation on the fatigue performance of dental strength-gradient multilayered zirconia restorations. J. Dent. 2024, 142, 104866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.G. Effect of low-temperature degradation treatment on hardness, color, and translucency of single layers of multilayered zirconia. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025, 133(1), 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavriqi, L.; Traini, T. Mechanical properties of translucent zirconia: An in vitro study. Prosthesis 2023, 5, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo-Junior, E.N.S.; Bergamo, E.T.P.; Bastos, T.M.C.; Benalcázar Jalkh, E.B.; Lopes, A.C.O.; Monteiro, K.N.; Cesar, P.F.; Tognolo, F.C.; Migliati, R.; Tanaka, R.; Bonfante, E.A. Ultra-translucent zirconia processing and aging effect on microstructural, optical, and mechanical properties. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38(4), 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, S.G.A.; Hussein, H.G.A.; Mohamed, G.A.; Ibrahim, S.R.M. Different Zirconia Surface Treatments: Strategies to Enhance Adhesion in Zirconia-Based Dental Restorations. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2025, 17, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaminaci Russo, D.; Cinelli, F.; Sarti, C.; Giachetti, L. Adhesion to Zirconia: A Systematic Review of Current Conditioning Methods and Bonding Materials. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, L.G.; Pang, N.S.; Kim, S.H.; Jung, B.Y. Mechanical properties of additively manufactured zirconia with alumina air abrasion surface treatment. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaoka, N.; Yoshihara, K.; Tamada, Y.; Yoshida, Y.; Van Meerbeek, B. Ultrastructure and bonding properties of tribochemical silica-coated zirconia. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38(1), 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyazadehfar, N.; Azimi Zavaree, M.; Shayegh, S.S.; Yahyazadehfar, M.; Hooshmand, T.; Hakimaneh, S.M.R. Effect of different surface treatments on surface roughness, phase transformation, and biaxial flexural strength of dental zirconia. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospects 2021, 15(3), 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Jang, G.W.; Park, I.I.; Heo, Y.R.; Son, M.K. The effects of surface grinding and polishing on the phase transformation and flexural strength of zirconia. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2019, 11(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, H.; Abdulsamee, N.; Farouk, H.; Saba, D.A. Effect of Er:YAG laser surface treatment on surface properties and shear-bond strength of resin-cement to three translucent zirconia: An in vitro study. Discov. Mater. 2024, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, S.B.; Ferreira, L.C.; Mazza, L.C.; Dos Santos, D.M.; Pesqueira, A.A.; Theodoro, L.H. Effect of laser irradiation on bond strength between zirconia and resin cement or veneer ceramic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2021, 21(2), 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergun Kunt, G.; Duran, I. Effects of laser treatments on surface roughness of zirconium oxide ceramics. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18(1), 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakırbay Tanış, M.; Akay, C.; Şen, M. Effect of selective infiltration etching on the bond strength between zirconia and resin luting agents. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2019, 31(3), 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimal, A.; Ramdev, P.; Shruthi, C.S. Evaluation of effect of zirconia surface treatment, using plasma of argon and silane, on the shear bond strength of two composite resin cements. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11(8), ZC39–ZC43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, K.; Hosseinpour, S.; Mohammad-Rahimi, H. The impact of plasma treatment of Cercon® zirconia ceramics on adhesion to resin composite cements and surface properties. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 8 (Suppl. 1), S56–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skienhe, H.; Abdou, A.; Matinlinna, J.P.; Ferrari, M.; Salameh, Z. Effect of low-fusing porcelain glaze as zirconia surface treatment on the adhesion of resin cement. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2025, 17(4), e407–e415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malgaj, T.; Mirt, T.; Kocjan, A.; Jevnikar, P. The Influence of Nanostructured Alumina Coating on Bonding and Optical Properties of Translucent Zirconia Ceramics: In Vitro Evaluation. Coatings 2021, 11, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Külünk, T.; Külünk, Ş.; Baba, S.; Oztürk, Ö.; Danişman, Ş.; Savaş, S. The effect of alumina and aluminium nitride coating by reactive magnetron sputtering on the resin bond strength to zirconia core. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2013, 5(4), 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Yang, X.; Jiang, T. Influence of hot-etching surface treatment on zirconia/resin shear bond strength. Materials 2015, 8(12), 8087–8096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, F.; Liu, M.; Cui, Z.; Ma, J.; Chen, J. Effect of hot etching with HF on the surface topography and bond strength of zirconia. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 1008704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołasz, P.; Kołkowska, A.; Zieliński, R.; Simka, W. Zirconium Surface Treatment via Chemical Etching. Materials 2023, 16, 7404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojedehian, H.; Moezzizadeh, M.; Abdollahi, N.; Soltaninejad, F.; Valizadeh Haghi, H. The effect of bioglass coating on microshear bond strength of resin cement to zirconia. Front. Dent. 2024, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Pow, E.H.N.; Tsoi, J.K.; Matinlinna, J.P. Evaluation of four surface coating treatments for resin to zirconia bonding. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 32, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Her, S.B.; Kim, K.H.; Park, S.E.; Park, E.J. The effect of zirconia surface architecturing technique on the zirconia/veneer interfacial bond strength. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2018, 10(4), 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkamhaeng, K.; Poomparnich, K.; Chitkraisorn, T.; Boonpitak, K.; Tosiriwatanapong, T. Effect of combining different 10-MDP-containing primers and cement systems on shear bond strength between resin cement and zirconia. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalaj, V.; Kamath, V.; Pai, U.; Natarajan, S.; S, S.; Gupta, A. Effect of sandblasting and MDP-based primer application on the surface topography and shear bond strength of zirconia: An in vitro study. F1000Res. 2025, 14, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Wang, H.; Shi, Y.; Su, Z.; Hannig, M.; Fu, B. The Effect of Surface Treatments on Zirconia Bond Strength and Durability. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, R.; Tsujimoto, A.; Takamizawa, T.; Tsubota, K.; Suzuki, T.; Shimamura, Y.; Miyazaki, M. Influence of surface treatment of contaminated zirconia on surface free energy and resin cement bonding. Dent. Mater. J. 2015, 34(1), 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, S.A.; Lima, N.B.; Yoshito, W.K.; Campos, F.; Bottino, M.A.; Valandro, L.F.; Bottino, M.C. Bonding strategies to full-contour zirconia: Zirconia pretreatment with piranha solution, glaze and airborne-particle abrasion. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2017, 77, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Cho, S.-C.; Lee, M.-H.; Kim, H.-J.; Oh, N.-S. Effect of 9% Hydrofluoric Acid Gel Hot-Etching Surface Treatment on Shear Bond Strength of Resin Cements to Zirconia Ceramics. Medicina 2022, 58, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Yu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Shi, Z.; Cui, Z.; Zhu, S. Construction of a silicate-based epitaxial transition film on a zirconia ceramic surface to improve the bonding quality of zirconia restorations. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 32476–32484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, A.; Palacios, N.; Jiménez, O.R. Zirconia Cementation: A Systematic Review of the Most Currently Used Protocols. Open Dent. J. 2024, 18, e18742106300869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liang, S.; Inokoshi, M.; Zhao, S.; Hong, G.; Yao, C.; Huang, C. Different surface treatments and adhesive monomers for zirconia-resin bonds: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2024, 60, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigos, A.E.; Sarafidou, K.; Kontonasaki, E. Zirconia bond strength durability following artificial aging: A systematic review and meta-analysis of in vitro studies. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2023, 59, 138–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, M.F.R.P.; dos Santos, C.; Elias, C.N.; Amarante, J.E.V.; Ribeiro, S. Comparison between different fracture toughness techniques in zirconia dental ceramics. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2023, 111, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrabeah, G.; Al-Sowygh, A.H.; Almarshedy, S. Use of Ultra-Translucent Monolithic Zirconia as Esthetic Dental Restorative Material: A Narrative Review. Ceramics 2024, 7, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatz, M.B.; Alvarez, M.; Sawyer, K.; Brindis, M. How to Bond Zirconia: The APC Concept. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2016, 37, 611–617. [Google Scholar]

- Alshali, R. Z.; Alqahtani, M. A.; Alturki, B. N.; Algizani, L. I.; Batarfi, A. O.; Alshamrani, Z. K.; Faden, R. M.; Bukhary, D. M.; Altassan, M. M. Effect of air-particle abrasion and methacryloyloxydecyl phosphate primer on fracture load of thin zirconia crowns: An in vitro study. Front. Dent. Med. 2024, 5, 1501909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, R.; Elhejazi, A.; Alnahedh, H.; Maawadh, A. Effects of different airborne particle abrasion protocols on the surface roughness and shear bonding strength of high/ultra-translucent zirconia to resin cement. Ceramics-Silikáty 2021, 65, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Ferreyra, B.I.; Moyaho-Bernal, M.L.A.; Chavarría-Lizárraga, H.N.; Castro-Ramos, J.; Franco-Romero, G.; Velázquez-Enríquez, U.; Flores-Ledesma, A.; Reyes-Cervantes, E.; Ley-García, A.K.; Velasco-León, E.D.C.; Carrasco-Gutiérrez, R.G. Surface treatment, chemical characterization, and debonding crack initiation strength for veneering dental ceramics on Ni-Cr alloys. Materials 2025, 18, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobuaki, A.; Keiichi, Y.; Takashi, S. Effects of air abrasion with alumina or glass beads on surface characteristics of CAD/CAM composite materials and the bond strength of resin cements. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2015, 23, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlMutairi, R.; AlNahedh, H.; Maawadh, A.; Elhejazi, A. Effects of Different Air Particle Abrasion Protocols on the Biaxial Flexural Strength and Fractography of High/Ultra-Translucent Zirconia. Materials 2022, 15, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kui, A.; Buduru, S.; Labuneț, A.; Sava, S.; Pop, D.; Bara, I.; Negucioiu, M. Air Particle Abrasion in Dentistry: An Overview of Effects on Dentin Adhesion and Bond Strength. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turp, V.; Sen, D.; Tuncelli, B.; Goller, G.; Özcan, M. Evaluation of air-particle abrasion of Y-TZP with different particles using microstructural analysis. Aust. Dent. J. 2013, 58, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagodzinska, P.; Dejak, B.; Konieczny, B. The influence of alumina airborne-particle abrasion on the properties of zirconia-based dental ceramics (3Y-TZP). Coatings 2023, 13, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.E.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.B.; Han, J.S.; Yeo, I.S.; Ha, S.R. Effects of airborne-particle abrasion protocol choice on the surface characteristics of monolithic zirconia materials and the shear bond strength of resin cement. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 1552–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shofu Dental Asia-Pacific. ZR Lucent. Available online: https://www.shofu.com.sg/product/zr-lucent/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- BEGO GmbH & Co., KG. Korox 50. Available online: https://eshop.bego.com/en-en/products/den_46062 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Renfert GmbH. Rolloblast 100 µm. Available online: https://www.renfert.com/en/products/materials/dental-abrasives/rolloblast (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Shofu Dental Asia-Pacific. AZ Primer. Available online: https://shofu.co.in/available_products/az-primer (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Shofu Dental Asia-Pacific. ResiCem. Available online: https://www.shofu.com.sg/product/resicem/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Carek, A.; Dukaric, K.; Miler, H.; Marovic, D.; Tarle, Z.; Par, M. Post-Cure Development of the Degree of Conversion and Mechanical Properties of Dual-Curing Resin Cements. Polymers 2022, 14, 3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, M.S.; Darvell, B.W. Thermal cycling procedures for laboratory testing of dental restorations. J. Dent. 1999, 27, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra-Prat, J.; Cano-Batalla, J.; Cabratosa-Termes, J.; Figueras-Àlvarez, O. Adhesion of dental porcelain to cast, milled, and laser-sintered cobalt-chromium alloys: Shear bond strength and sensitivity to thermocycling. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 112, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, M.; Poggio, C.; Lasagna, A.; Chiesa, M.; Scribante, A. Vickers Micro-Hardness of New Restorative CAD/CAM Dental Materials: Evaluation and Comparison after Exposure to Acidic Drink. Materials 2019, 12, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosmac, T.; Oblak, C.; Jevnikar, P.; Funduk, N.; Marion, L. The effect of surface grinding and sandblasting on flexural strength and reliability of Y-TZP zirconia ceramic. Dent. Mater. 1999, 15, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shehri, E.Z.; Al-Zain, A.O.; Sabrah, A.H.; Al-Angari, S.S.; Al Dehailan, L.; Eckert, G.J.; Özcan, M.; Platt, J.A.; Bottino, M.C. Effects of air-abrasion pressure on the resin bond strength to zirconia: A combined cyclic loading and thermocycling aging study. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2017, 42, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanakakis, E.; Tzoutzas, I.; Koidis, P. Is there a potential for durable adhesion to zirconia restorations? A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, L.; Kaizer, M.R.; Zhao, M.; Guo, B.; Song, Y.F.; Zhang, Y. Graded ultra-translucent zirconia (5Y-PSZ) for strength and functionalities. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, E.A.; Lawson, N.; Choi, J.; Kang, J.; Trujillo, C. New high-translucent cubic-phase-containing zirconia: Clinical and laboratory considerations and the effect of air abrasion on strength. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2017, 38, e13–e16. [Google Scholar]

- Michida, S.M. de A. ; Kimpara, E.T.; dos Santos, C.; Souza, R.O.A.; Bottino, M.A.; Özcan, M. Effect of air-abrasion regimens and fine diamond bur grinding on flexural strength, Weibull modulus and phase transformation of zirconium dioxide. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2015, 13, 266–273. [Google Scholar]

- Mehari, K.; Parke, A.S.; Gallardo, F.F.; Vandewalle, K.S. Assessing the Effects of Air Abrasion with Aluminum Oxide or Glass Beads to Zirconia on the Bond Strength of Cement. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2020, 21, 713–717. [Google Scholar]

- Alrabeah, G.; Alomar, S.; Almutairi, A.; Alali, H.; ArRejaie, A. Analysis of the effect of thermocycling on bonding cements to zirconia. Saudi Dent. J. 2023, 35, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yan, X.; Toufani, N.; Sano, H.; Fu, J. Curing modes affect micro-tensile bond strength and durability of dual curing resin cements to dentin. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 12, 1511099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samran, A.; Al-Ammari, A.; El Bahra, S.; Halboub, E.; Wille, S.; Kern, M. Bond strength durability of self-adhesive resin cements to zirconia ceramic: An in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.H.; Kim, S.J.; Shim, J.S.; Lee, K.W. Effect of zirconia surface treatment using nitric acid-hydrofluoric acid on the shear bond strengths of resin cements. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2017, 9, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, M.; Belli, R.; Cesar, P.F.; Valandro, L.F.; Petschelt, A.; Lohbauer, U. The potential of novel primers and universal adhesives to bond to zirconia. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alammar, A.; Blatz, M.B. The resin bond to high-translucent zirconia: A systematic review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2022, 34, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kui, A.; Manziuc, M.; Petruțiu, A.; Buduru, S.; Labuneț, A.; Negucioiu, M.; Chisnoiu, A. Translucent zirconia in fixed prosthodontics—An integrative overview. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.; Hussein, N.; Kusumasari, C.; et al. Alumina and glass-bead blasting effect on bond strength of zirconia using 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate (MDP) containing self-adhesive resin cement and primers. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amari, A.S.; Saleh, M.S.; Albadah, A.A.; Almousa, A.A.; Mahjoub, W.K.; Al-Otaibi, R.M.; Alanazi, E.M.; Alshammari, A.K.; Malki, A.T.; Alghelaiqah, K.F.; Akbar, L.F. A comprehensive review of techniques for enhancing zirconia bond strength: Current approaches and emerging innovations. Cureus 2024, 16, e70893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liang, S.; Li, J.; Tang, W.; Yu, M.; Ahmed, M.H.; Liang, S.; Zhang, F.; Inokoshi, M.; Yao, C.; Huang, C. Influence of surface treatments on highly translucent zirconia: Mechanical, optical properties and bonding performance. J. Dent. 2025, 154, 105580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.M.; Joseph, S.; Mathew, N.; Koshy, A.T.; Jayalakshmi, N.L.; Mathew, V. Effect of incorporation of nanoclay on the properties of heat cure denture base material: An in vitro study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2019, 10, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shofu Dental Europe. ZR Lucent Supra. Available online: https://www.shofu-dental.fr/en/produkt/shofu-disk-zr-lucent-supra-en (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Nakai, H.; Inokoshi, M.; Liu, H.; Uo, M.; Kanazawa, M. Evaluation of extra-high translucent dental zirconia: Translucency, crystalline phase, mechanical properties, and microstructures. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejak, B.D.; Langot, C.; Krasowski, M.; Klich, M. Evaluation of hardness and wear of conventional and transparent zirconia ceramics, feldspathic ceramic, glaze, and enamel. Materials 2024, 17, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongkiatkamon, S.; Booranasophone, K.; Tongtaksin, A.; Kiatthanakorn, V.; Rokaya, D. Comparison of fracture load of the four translucent zirconia crowns. Molecules 2021, 26, 5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongkiatkamon, S.; Rokaya, D.; Kengtanyakich, S.; Peampring, C. Current classification of zirconia in dentistry: An updated review. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıkaya, I.; Hayran, Y. Adhesive bond strength of monolithic zirconia ceramic finished with various surface treatments. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguiar, T.C.; Saad, J.R.C.; Pinto, S.C.S.; Calixto, L.R.; Lima, D.M.; Silva, M.A.S.; et al. The effects of exposure time on the surface microhardness of three dual-cured dental resin cements. Polymers 2011, 3, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Oh, K.C.; Moon, H.S. Effects of surface-etching systems on the shear bond strength of dual-polymerized resin cement and zirconia. Materials 2024, 17, 3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osuchukwu, O.A.; Salihi, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Audu, A.A.; Makoyo, M.; Mohammed, S.A.; Lawal, M.Y.; Etinosa, P.O.; Isaac, I.O.; Oni, P.G.; Oginni, O.G.; Obada, D.O. Weibull analysis of ceramics and related materials: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Brand and Manufacturer | Shade and Composition |

|---|---|---|

| High- Translucent 5Y-PSZ Zirconia Ceramic | ZR Lucent, Shofu Dental Corporation, Kyoto, Japan | Shade: A2; Composition: A multilayer zirconia disc with dimensions 98.5 × 18 mm fabricated from 100% Tosoh zirconia powder, containing 5 mol% yttria-stabilized zirconia (5Y-PSZ). The disc comprises five gradient layers with varying translucency and strength: one enamel layer (30%), three dentin layers (35%), and one cervical layer (35%). Exact oxide weight percentages are not disclosed in the manufacturer’s literature [71]. |

| Dual cure adhesive resin cement | ResiCem, Shofu Dental Corporation, Kyoto, Japan | Shade: Clear; Composition: Paste A- UDMA, TEGDMA, Fluoro-alumino-silicate glass, initiator [75]. Paste B- UDMA, TEGDMA, Carboxylic acid monomer, 4-AET, 2-HEMA, Fluoro-alumino-silicate glass, initiator [75]. |

| Primer | AZ primer, Shofu Dental Corporation, Kyoto, Japan | Composition: Phosphonic acid monomer (6-MHPA), Thioctic acid monomer, Acetone [74]. |

| 50-μm Al₂O₃ | Korox 50, Bego, Germany | Composition: 99.6 % Al₂O₃, special corundum, other constituents [72]. |

| 100-μm glass microbeads | Rolloblast, Renfert, Germany | Composition: Glass microbeads [73]. |

| Group | Mean (MPa) ± SD | Mean Difference (MPa) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| I- Control | 5.64 ± 1.49 | - | - |

| II- 50 µm Al₂O₃ | 6.49 ± 1.59 | vs I: 0.85 | vs I: 0.875 |

| III- 100 µm Glass Microbeads | 6.42 ± 4.05 | vs I: 0.78 vs II: - 0.07 |

vs I: 0.889 vs II: 0.999 |

| Group | Mean (MPa) ± SD | Mean Difference (MPa) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| I- Control | 876.34 ± 25.10 | - | - |

| II- 50 µm Al₂O₃ | 1747.26 ± 37.37 | vs I: 870.92 | vs I: ˂ 0.001* |

| III- 100 µm Glass Microbeads | 1246.94 ± 33.81 | vs I: 370.60 vs II: - 500.32 |

vs I: ˂ 0.001* vs II: ˂ 0.001* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).