1. Introduction

Work-related neck pain (WRNP) is a common condition among office workers, especially workers who use computers on a daily basis [

1]. Globally, 27.0 per 1000 workers has work-related neck pain [

2], and about 49-67% of workers using computers for at least 6 hours a day has neck pain complaints [

3,

4]. The pain doesn’t affect workers clinically, but also company’s productivity which cost the company financially. While the computer use increases over time, this burden is critical to be solved.

Computer or laptop use often leads workers to sit for hours, and non-ergonomic position, such as forward leaning head position and increased thoracic kyphosis, potentially increase the workload of spinal muscles and joints, including the neck [

4]. Changes in head posture that tend to move forward, particularly when using laptop, can increase the activity of the upper

trapezius and

erector spinae cervicalis muscles, increasing the risk of neck and shoulder pain. This pressure triggers for the neck pain [

5]. It is therefore important for head and neck to stay in a straight-line axis while visibility is maintained to reduce the burden of the neck and shoulder muscles [

4].

One of potential intervention to reduce or prevent the pain when using computer or laptop is using notebook riser and external keyboard. These can improve work posture, especially in maintaining a neutral posture between the head and neck while using a laptop [

6] and therefore can significantly reduce fatigue. A study shows that workers using notebook riser had 24% lower mechanical load (

torque) on cervical segments C7-Th1 and an average 17% lower discomfort score than workers without notebook risers. They also had 17% higher productivity score than those without notebook riser [

7].

However, there has been limited study examining the effect of notebook riser in preventing and reducing neck pain, especially among Indonesian workers. Therefore, this study aimed to assess whether the use of notebook risers and external keyboards as additional instruments to improve posture during laptop use for work could prevent and prevent the neck pain among office workers in Indonesia.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a superiority, non-randomized controlled trial study involving 60 office workers in a mining company operating in Indonesia.

2.1. Setting and Population

The study was conducted at a nickel exploration company located in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia, which was purposively selected. The company’s office-based employees, ranging from management to operational staff, routinely perform daily administrative tasks using laptops. Prior to the study, an initial ergonomic survey was conducted using the Rapid Office Strain Assessment (ROSA) questionnaire among 40 randomly selected workers. The results indicated that more than 50% were at high risk of developing neck pain due to non-ergonomic head and neck postures, likely resulting from prolonged laptop use.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All office-based workers who used laptops in two office sites of the company were included in the study. Participants were not randomly allocated; instead, two distinct office populations were selected to avoid potential interference between intervention and control groups. Workers with a history of chronic neck pain or acute neck pain within the past three days, as well as those who had used a notebook riser during the same period, were excluded. These criteria were verified through a screening questionnaire, and individuals who declined to participate were also excluded from the study.

2.3. Intervention

We divided the intervention and control groups based on the office-based sites to avoid interference. Thirty workers in the intervention group received notebook risers and external keyboards for them to use and educational session about ergonomics, while other 30 workers in control group receive only education session about ergonomics. The education session was delivered by the principal investigator, AHV, at Day-0.

2.4. Variables and Assessment

The effect of the notebook riser was assessed by measuring participants’ neck pain at baseline and daily through Day-10. Neck pain was evaluated using the Nordic Body Discomfort Map to identify the presence and progression of pain over the study period. Baseline data included demographic and individual characteristics such as gender, age, job position, tenure, physical activity, and smoking status. In addition, information on the daily duration of smartphone and laptop use—both within and outside working hours—was collected at baseline (Day 0) using a self-developed questionnaire.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data were collected at baseline (Day-0) and monitored daily until Day-10. Descriptive analyses were performed using frequencies (n) and percentages (%), and the trend of neck pain complaints was illustrated through a bar graph. To assess the effect of notebook riser use on the prevention of neck pain, binary logistic regression analysis was conducted using SPSS software to estimate the crude relative risk (cRR) and adjusted relative risk (aRR), along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and significance levels.

3. Results

All of 60 participants completed the trial. There were no statistically significant differences between groups in gender, job position, tenure period, physical activity, smoking, smartphone use duration, and duration of laptop use within and outside working hours (

Table 1). More workers aged >30 years in control group than in intervention group.

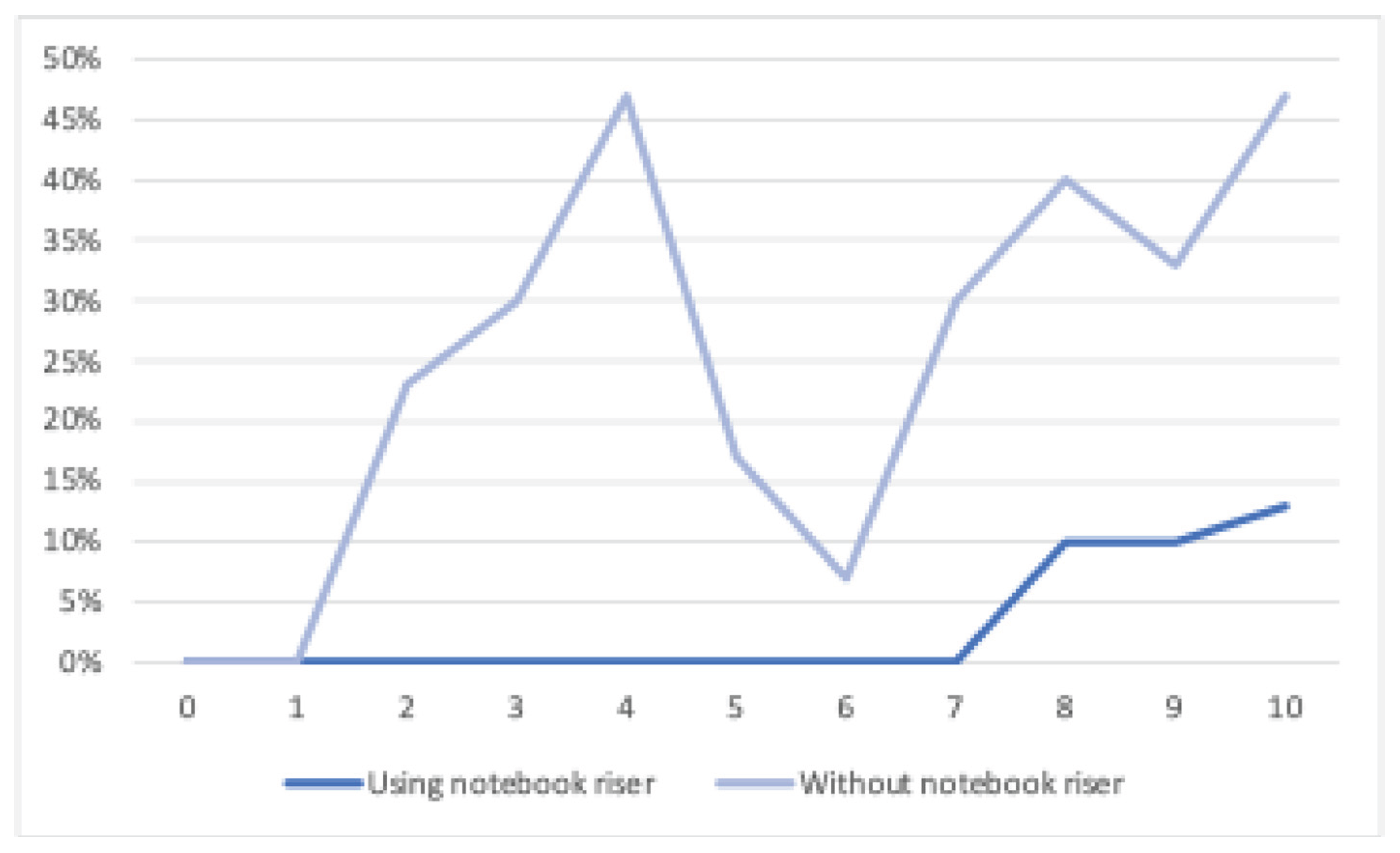

In measurements of neck pain complaints during 10 days of observation, there was a clear difference between the control group and the intervention group. At baseline (H0), all participants at both groups reporting no pain. However, from Day-2 to Day-4, more participants in the control group reported pain complaints than those in the intervention group. At Day-5 and Day-6, the pain complaints reduced, due to weekend and reduced workload. Since Day-7, the reported pain increased in both groups, but the proportion of participants reported pain was higher in control group than intervention group. (

Figure 1)

Until Day-10, workers using notebook risers has statistically significantly lower pain than those without notebook riser, indicating the lower risk of neck pain (cRR = 0.06, 95% CI: 0.02-0.24, P<0.001). The significant lower risk of neck pain was also found in workers’ age below 30 years (cRR = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.04-0.34, P<0.001) and lower ergonomic risk (cRR = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.03-0.28, P<0.001).

After adjustment to potential confounders, notebook riser use significantly prevent neck pain than without notebook risers (aRR=0.19, 95% CI 0.04-0.8, p=0.03). Ergonomic risk was also a significant factor where respondents with lower ergonomic risk were less likely to experience neck pain (aRR=0.157, 95% CI 0.03-0.83, p=0.03). Other variables, i.e., gender, physical activity, worker characteristics, tenure, and smoking habits showed no significant association with neck pain).

Table 2.

Effect of using a notebook riser on preventing neck pain.

Table 2.

Effect of using a notebook riser on preventing neck pain.

| Variabel |

Increasing pain |

Not increasing pain |

cRR |

95%CI |

P |

aRR |

95%CI |

P |

| Notebook riser |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

2 (3%)

|

23 (38%)

|

0,06 |

0,02-0,24 |

<0,001 |

0,19

Ref |

0,04-0,89 |

0,03 |

| No |

33(55%)

|

2 (3%)

|

Ref |

|

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 21-30 years |

3 (5%)

|

19 (32%)

|

0,13 |

0,04-0,34 |

<0,001 |

1,37

Ref |

0,62-3,01 |

0,43 |

| >30 years |

32 (53%)

|

6 (10%)

|

Ref |

|

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Female |

10 (17%)

|

11 (18%)

|

0,65 |

0,33-1,29 |

0,217 |

1,17

Ref |

0,75-1,82 |

0,50 |

| Male |

25 (42%)

|

14 (23%)

|

Ref |

|

| Physical Activity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| >90 second/week |

33 (55%)

|

19 (32%)

|

1,24 |

0,98-1,57 |

0,040 |

1,13

Ref |

0,66-1,95 |

0,65 |

| 0-90 second/week |

2 (3%)

|

6 (10%)

|

Ref |

|

| Worker Characteristics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Administration |

11 (18%)

|

9 (15%)

|

0,87 |

0,43-1,79 |

0,711 |

1,07

Ref |

0,56-2,06 |

0,83 |

| Manager/Spv/ etc |

24 (40%)

|

16 (27%)

|

Ref |

|

| Working Period |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 year |

10 (17%)

|

13 (22%)

|

0,55 |

0,29-1,05 |

0,066 |

0,76

Ref |

0,50-1,14 |

0,18 |

| >1 years |

25 (42%)

|

12 (20%)

|

Ref |

|

| Duration of Laptop Use During Working Hours |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2-4 hours/day |

5 (8.3%)

|

9 (15%)

|

0,40 |

0,15-1,04 |

0,050 |

0,80

Ref |

0,56-1,14 |

0,21 |

| 5-7 hours/day |

30 (50%)

|

16 (27%)

|

Ref |

|

| Smoking Status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No. |

21 (35%)

|

16 (27%)

|

0,94 |

0,63-1,40 |

0,753 |

0,89

Ref |

0,59-1,36 |

0,60 |

| Yes |

14 (23%)

|

9 (15%)

|

Ref |

|

| Ergonomic risk |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Low |

3 (5%)

|

23 (38%)

|

0,09 |

0,03-0,28 |

<0,001 |

0,16

Ref |

0,03-0,83 |

0,03 |

| High |

32 (53%)

|

2 (3%)

|

Ref |

|

| Duration of Laptop Use Outside Working Hours |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0-1 hours/day |

23 (38%)

|

23 (38%)

|

0,71 |

0,55-0,93 |

0,018 |

0,54

Ref |

0,23-1,24 |

0,15 |

| >1 hours/day |

12 (20%)

|

12 (3%)

|

Ref |

1,05-17,49 |

| Smartphone Use |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2-4 hours/day |

20 (33%)

|

16 (27%)

|

0,89 |

0,59-1,35 |

0,59 |

1,02

Ref |

0,50-2,14 |

0.94 |

| >4 hours/day |

15 (25%)

|

9 (15%)

|

Ref |

0,62-2,28 |

4. Discussion

The use of notebook risers among office-based workers in this study was significantly associated with a lower incidence of neck pain after 10 days compared to those without notebook riser. It indicates that the use of notebook risers significantly could prevent neck pain complaints among office workers with long sitting duration and position. This finding also strengthens the evidence that simple ergonomic interventions like the use of notebook risers would be effective in reducing static stress on the neck muscles, which is one of the main causes of neck pain in office workers.

This study findings highlights that use of notebook risers, mouse, and external keyboards could prevent neck pain, potentially through change of workers’ posture during works, as Asandi’s study (2012) found [

8]. Notebook risers are means of ergonomic supports that help workers maintain their neutral head position, improve work positions, and reduce the burden on the neck muscles. Increasing the height of the screen by 15–20 degrees can reduce the tension of the neck and shoulder muscles and decrease musculoskeletal complaints in the neck. Laptop screen tilt at an angle of 130° significantly reduces neck and shoulder discomfort compared to lower tilt angles, such as 100° or 115°, as this angle minimizes forward leaning head postures [

7]. Height adjustment of the laptop screen using a notebook riser and an external keyboard can reduce the cervical flexion angle by 4.53 degrees and cervical erector spinae muscle activity by 10.31%, and multifidius by 15.57%, which contributes to a decrease in neck and upper back discomfort [

9,

10,

11].

Consistent use of the notebook riser could prevent the pain that can last up to 36 weeks. A study reported that the effective use time of the notebook riser was around 4-6 hours per day to get the significant improvements in comfort and pain reduction [

12]. Optimal adjustment of the tilt angle and height of the notebook riser combined with an external keyboard and regular use for at least 12 weeks can effectively reduce or prevent neck pain in workers [

12,

13,

14,

15].

Although younger workers showed lower risk of neck pain in bivariate analysis, in this study, age was not a significant factor in preventing neck pain. Several studies also shows inconclusive findings if older age is related to increasing risk of neckl pain [

16,

18,

19]. The similar inconclusive findings also in relationship between neck pain and gender. [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Although older age biologically contributes to the decline in musculoskeletal function and women are assumed to generally have lower muscle strength than men,, it seems that ergonomic factor and nature of work is more likely the factor contribute to neckj pain.

This study found that physical activity was not related to neck pain. This may be affected by other variables of physical exercise, such as frequency and intensity of the activity [

24,

25], as well as type of physical activity, that were not captured in this study. Instead, static position during work may have significant role in developing neck pain [

26]. Prolonged sitting, typing activities, and looking at monitor screens are potential to develop neck pain [

27,

28,

29].

The effect of notebook risers use may be biased with laptop use time within and beyond Working hours. We found that less laptop use in working place was not significant to prevent neck pain [

30,

31] although prolonged use of electronic devices is assumed to cause musculoskeletal complaints, including pain in the neck or neck [

32]. It seems that the length of time laptops used beyond of working hours, poor posture and strenuous physical activity are more likely to induce neckpain [

33,

34]. The neck pain is more likely occur among those using smartphone use with duration of >10 hours/day [

35], buit it still depends on the posture position when using the smartphone [

36,

39].

This study has several limitations. First, only ten days and could not observe the effect in a longer period of observation. Second, only in one office, other office with different nature of work may have different results, cannot be generalized.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the use of notebook risers, complemented by external keyboards, effectively prevent neck pain among office workers, particularly those with high ergonomic risks. Although individual and occupational factors such as age, gender, and duration of laptop use were not significantly associated with neck pain, ergonomic workstation adjustments contributed to improved posture and comfort. These findings support the inclusion of ergonomic interventions—such as notebook risers—in occupational health and safety policies and highlight the need for further research on their long-term impact and scalability across diverse work settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H.V., M.I, and A.F; methodology, A.H.V., M.I, and A.F; validation, M.I, A.F., R.A.Z., and D.Y.F.; formal analysis, A.H.V., M.I, and A.F.; investigation, A.H.V, A.A, R.A., D.K., and R.F.N.; data curation, A.H.V, A.A, R.A., D.K., and R.F.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.V; writing—review and editing, A.H.V., M.I, A.F, R.A.Z., and D.Y.F.; visualization, A.H.V. and A.F.; supervision, M.I. and A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We received research ethical approval from the Ethical research Committee of Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia and Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital (Number: KET1579/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2024) prior to the study implementation.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants received explanation of the study objectives and procedures before they provided informed consent to join the study.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the company management for their guidance and support during this research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ROSA |

Rapid Office Strain Assessment |

| WRNP |

Work-related neck pain |

References

- Green BN. A literature review of neck pain associated with computer use: public health implications. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2008;52(3):161–167.

- Kazeminasab S, Nejadghaderi SA, Amiri P, et al. Neck pain: global epidemiology, trends and risk factors. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):26. [CrossRef]

- Louw S, Makwela S, Manas L, et al. Effectiveness of exercise in office workers with neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. South African J Physiother. 2017;73(1):392. [CrossRef]

- Lee S, Lee Y, Chung Y. Effect of changes in head postures during use of laptops on muscle activity of the neck and trunk. Phys Ther Rehabil Sci. 2017 Mar 30;6:33–8. [CrossRef]

- Kuo Y-L, Huang K-Y, Kao C-Y, et al. Sitting Posture during Prolonged Computer Typing with and without a Wearable Biofeedback Sensor. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 May;18(10). [CrossRef]

- Amanda, Zulkarnain Z. Peranan Laptop Support dalam mengurangi Kelelahan pada Pengguna Laptop. Insan. 2012 Aug 1;

- Berkhout AL, Hendriksson-Larsén K, Bongers P. The effect of using a laptopstation compared to using a standard laptop PC on the cervical spine torque, perceived strain and productivity. Appl Ergon. 2004;35(2):147–52. [CrossRef]

- Asundi K, Odell D, Luce A, et al. Changes in posture through the use of simple inclines with notebook computers placed on a standard desk. Appl Ergon. 2012 Mar;43(2):400–7. [CrossRef]

- Yadegaripour M, Hadadnezhad M, Abbasi A,et al. The Effect of Adjusting Screen Height and Keyboard Placement on Neck and Back Discomfort, Posture, and Muscle Activities during Laptop Work. Int J Hum Comput Interact. 2020 Oct 4;37:459–69.

- Guo Z, Chen Z, Pai J, et al. Effects of laptop screen height on neck and shoulder muscle fatigue and spine loading for office workers. Work. 2024;79(4):1925–37. [CrossRef]

- Basakci Calik B, Yagci N, Oztop M, et al. Effects of risk factors related to computer use on musculoskeletal pain in office workers. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2022 Mar;28(1):269–74. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs K, Johnson P, Dennerlein J, et al. University students’ notebook computer use. Appl Ergon. 2009;40:404–9.

- Ghadimi H, Garosi E, Izadi Laybidi M, et al. Ergonomic Design and Assessment of an Adjustable Laptop Stand Used in the Typing Task. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2023;37:139. [CrossRef]

- Chiou W-K, Chou W-Y, Chen B-H. Notebook computer use with different monitor tilt angle: effects on posture, muscle activity and discomfort of neck pain users. Work. 2012;41 Suppl 1:2591–5. [CrossRef]

- Rahma Z, Agustini D, Supartono B. Efek postur , lama duduk dan ukuran laptop terhadap nyeri leher selama pembelajaran daring. Maj Kedokt Andalas [Internet]. 2022;45(3):256–69. Available from: http://jurnalmka.fk.unand.ac.id.

- Attawuni A. Pengaruh Penggunaan Perangkat Digital Terhadap Timbulnya Nyeri Leher dan Bahu Pada Mahasiswa Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Yarsi. Jr Med J. 2023;1(3):359–71. [CrossRef]

- Marcilin M, Situngkir D. Faktor-faktor yang berhubungan dengan keluhan musculoskeletal disorders pada unit sortir di pt. indah kiat pulp and paper tangerang. tbk tahun 2018. J Ind Hyg Occup Heal. 2020 May 13;4. [CrossRef]

- Setyowati S, Widjasena B, Jayanti S. Hubungan Beban Kerja, Postur Dan Durasi Jam Kerja Dengan Keluhan Nyeri Leher Pada Porter Di Pelabuhan Penyeberangan Ferry Merak-Banten. J Kesehat Masy. 2017;5(5):356–68.

- Rahman A, Muis M, Thamrin Y. Faktor yang berhubungan dengan keluhan nyeri leher pada karyawan pt. angkasa pura: Factors Related to Complaints of Neck Pain in Employees at PT. Angkasa Pura. Hasanuddin J Public Heal. 2021;2:266–80.

- Cagnie B, Danneels L, Van Tiggelen D, et al. Individual and work related risk factors for neck pain among office workers: a cross sectional study. Eur spine J Off Publ Eur Spine Soc Eur Spinal Deform Soc Eur Sect Cerv Spine Res Soc. 2007 May;16(5):679–86. [CrossRef]

- Yeoh A, Collins A, Fox K, et al. Treatment delay and the risk of relapse in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;34(1):38–42. [CrossRef]

- Nadhifah N, Udijono A, Wuryanto MA, et al. Gambaran kejadian nyeri leher pada pengguna smartphone (Studi Di Pulau Jawa 2020). J Kesehat Masy. 2021;9(4):548–54. [CrossRef]

- Aulia R, Faidullah HZ, Nurhayati UA. Hubungan Physical Activity , Kurva Neck dan Tingkat Stres terhadap Neck Pain pada Mahasiswa Yogyakarta. 2025;7(4):2962–73. [CrossRef]

- Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, et al. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2017. 4(4):1-68.

- Dzakpasu FQS, Carver A, Brakenridge CJ, et al. Musculoskeletal pain and sedentary behaviour in occupational and non-occupational settings: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18(1):159. [CrossRef]

- Szeto GPY, Ho P, Ting ACW, et al. Work-related Musculoskeletal Symptoms in Surgeons. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(2):175–84. [CrossRef]

- Waersted M, Hanvold TN, Veiersted KB. Computer work and musculoskeletal disorders of the neck and upper extremity: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010; 11:79. [CrossRef]

- Szeto GPY, Straker L, Raine S. A field comparison of neck and shoulder postures in symptomatic and asymptomatic office workers. Appl Ergon. 2002;33(1):75–84. [CrossRef]

- Hardianto, Elly Trisnawati, Rossa I. Faktor-Faktor Yang Berhubungan Dengan Keluhan Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs) Pada Karyawan Bank X. J Chem Inf Model. 2015;(9):1–20.

- IJmker S, Huysmans MA, Van Der Beek AJ, et al. Software-recorded and self-reported duration of computer use in relation to the onset of severe arm-wrist-hand pain and neck-shoulder pain. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68(7):502–9. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud NA, Abu Raddaha AH, Zaghamir DE. Impact of Digital Device Use on Neck and Low Back Pain Intensity among Nursing Students at a Saudi Government University: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthc (Basel, Switzerland). 2022;10(12). [CrossRef]

- Anderson V, Bernard B, Burt SE, et al. Musculoskeletal Disorders and Workplace Factors: A Critical Review of Epidemiologic Evidence for Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders of the Neck, Upper Extremity, and Low Back. 1997.

- El Shunnar K, Afeef Nisah M, Kalaji ZH. The impact of excessive use of smart portable devices on neck pain and associated musculoskeletal symptoms. Prospective questionnaire-based study and review of literature. Interdiscip Neurosurg Adv Tech Case Manag. 2024;36:1-4. [CrossRef]

- Hakami I, Sherwani A, Hadadi M, et al. Assessing the Impact of Smartphone Use on Neck Pain and Related Symptoms Among Residents in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus. 2024;16(7). [CrossRef]

- Putri, Aulia M, Violita E, et al. Studi Kesehatan Masyarakat P, Ilmu Kesehatan F, Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta U. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Neck Pain in College Students Prevalensi dan Faktor Risiko yang Berhubungan dengan Neck Pain pada Mahasiswa. J Prot Kesehat. 2023;12(1):7–14.

- Mustafaoglu R, Yasaci Z, Zirek E, et al. The relationship between smartphone addiction and musculoskeletal pain prevalence among young population: a cross-sectional study. Korean J Pain. 2021 Jan;34(1):72–81. [CrossRef]

- Oktaviannoor H, Helmi ZN, Setyaningrum R. The Correlation between Smoking Status and BMI with The Complaints of Musculoskeletal Disorders on Palm Farmers. Int J Public Heal Sci. 2015;4(2):140.

- Shiri R, Karppinen J, Leino-Arjas P, et al. The association between smoking and low back pain: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2010 Jan;123(1):87.e7-35.

- Pramono T, Sayuti A, Gaffar M, et al. Penilaian Risiko Ergonomi Pada Lingkungan Kerja Perkantoran Menggunakan Metode Rapid Office Strain Assessment (ROSA). J Pendidik Adm Perkantoran. 2022;10:246–55. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).