Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

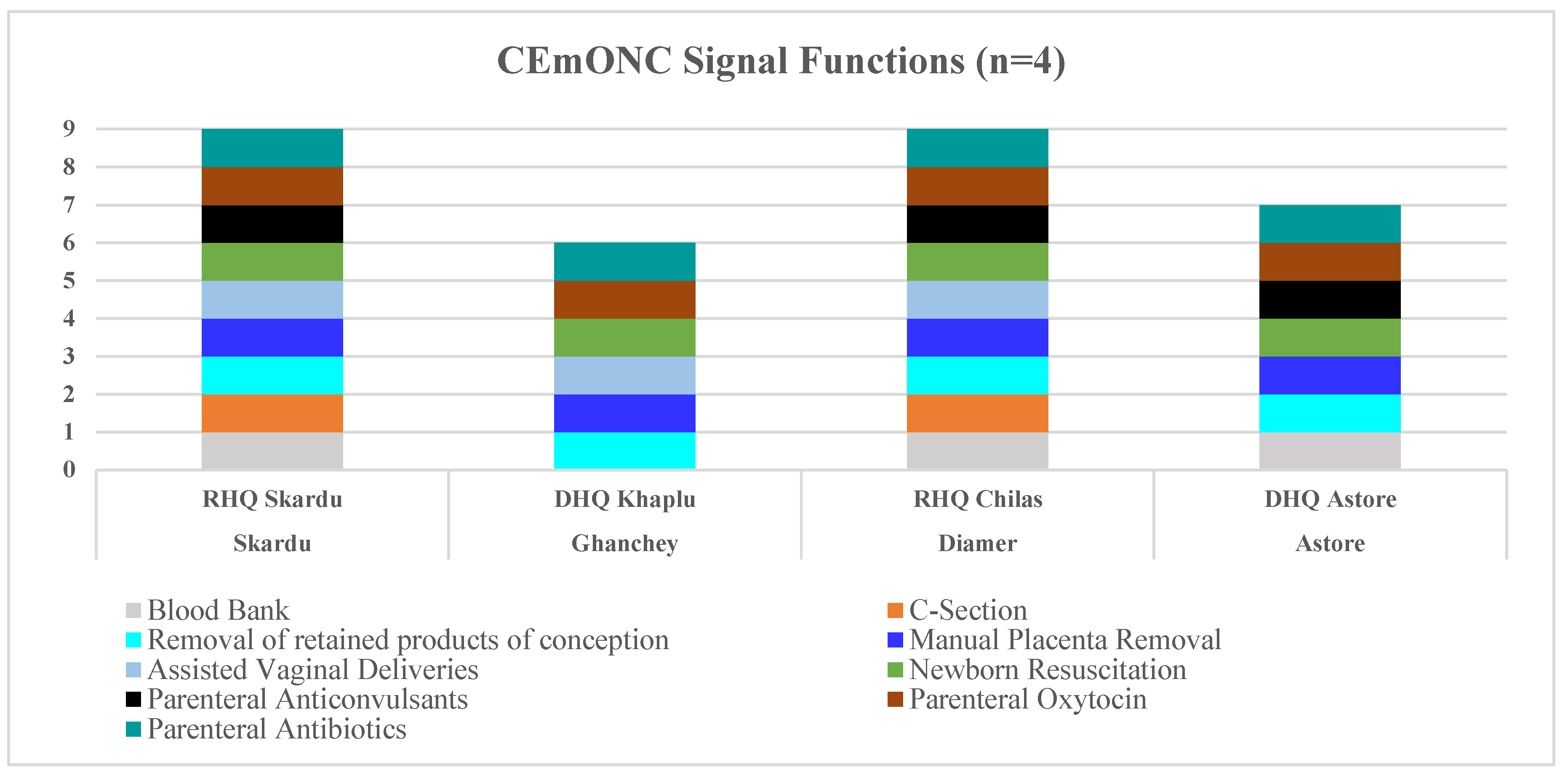

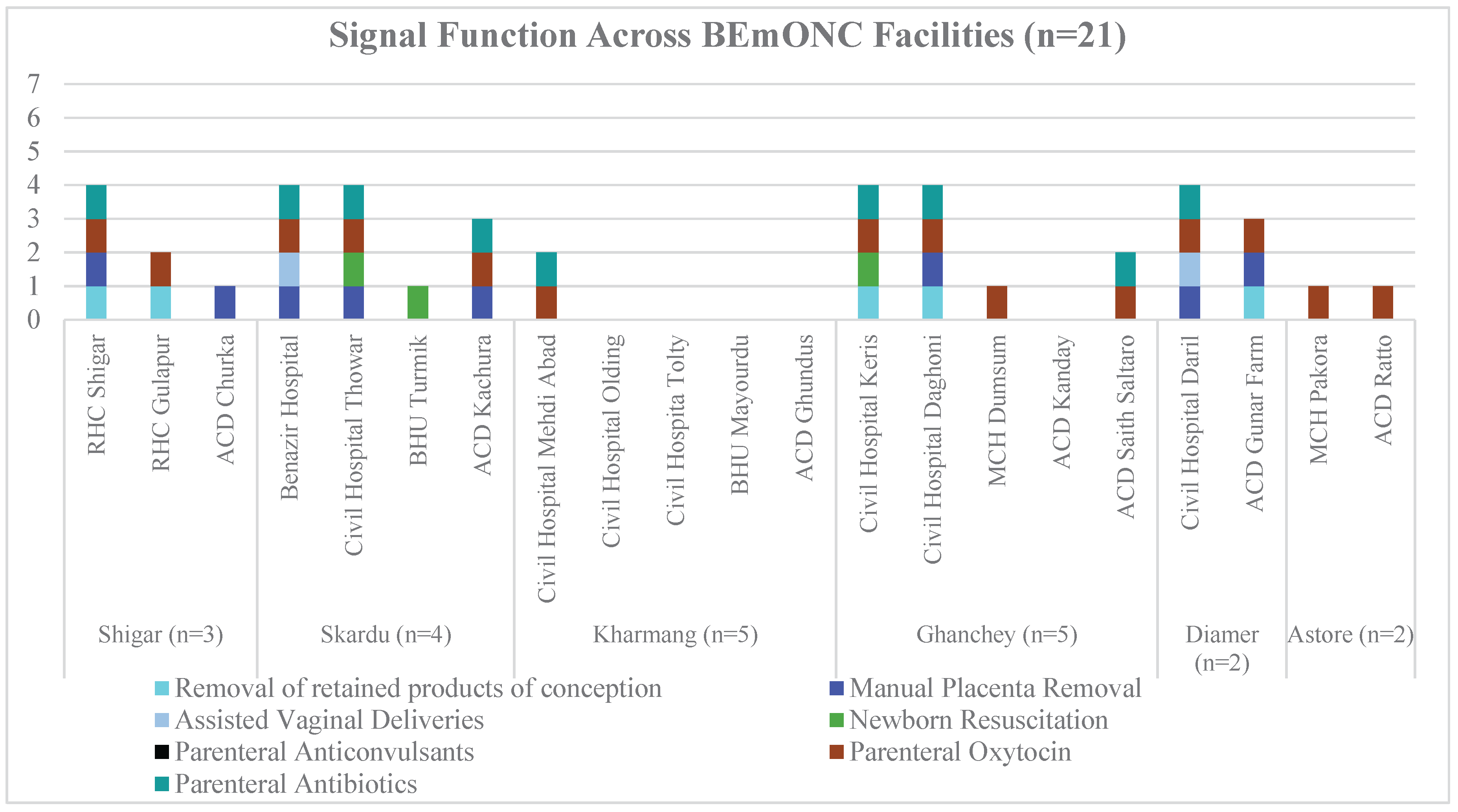

Background: High maternal and neonatal mortality in Pakistan, especially in the geographically challenging and underserved region of Gilgit-Baltistan, underscores the urgent need to strengthen Basic and Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (BEmONC and CEmONC) services. With limited progress toward SDGs 3.1 and 3.2, this study aims to assess the health system issues that lead to poor maternal and neonatal health outcomes. Methods: This mixed-methods study evaluated the maternal and neonatal healthcare services across six high-mortality districts in Baltistan and Diamer, Northern Pakistan. Using the Health Facility Assessment tools, we evaluated infrastructure, delivery volume, signal functions, and workforce capacity. Geospatial analysis examined facility accessibility, while surveys captured provider confidence in managing emergencies and patient satisfaction via exit interviews. Focus groups with healthcare providers and pregnant women provided valuable insights into community experiences. Results: Out of 60 assessed healthcare facilities, only 25 (41.7%) were found to be functional. They included four high-volume CEmONC sites and 21 low-volume BEmONC centers. Only one facility met all nine signal functions. NICUs were available in just two facilities, while only four facilities had operating rooms. Staff were critically inadequate, and the existing staff lacked confidence in managing obstetric complications. Patient satisfaction was mixed, with concerns over delays, hygiene, and staff shortages. Although 76.2% of BEmONC facilities were within two hours of a CEmONC facility, access to advanced care remains limited. Focus groups revealed barriers to access and community-led potential solutions. Conclusion: The study identifies critical gaps in maternal and neonatal health services across Baltistan and Diamer, revealing significant disparities in facility functionality, human resources, and service availability. An evidence-based package with a health system approach is vital to ensure adequate resource allocation and improved maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study Design and Setting

Data Collection Tools

Sampling

Training and Data Collection

Data Analysis

Ethical Considerations

Results

Barriers to Health Service Utilization: Qualitative findings

Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

Author Declaration

Ethics Approval

References

- World Health Organization. Maternal mortality [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality.

- World Health Organization. Neonatal mortality [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborn-mortality.

- UNICEF. Maternal mortality [Internet]. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2023 [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/maternal-mortality/.

- World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240068759.

- World Bank. Pakistan [Internet]. Washington, DC: World Bank Group; [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/country/pakistan.

- Anwar, J.; Torvaldsen, S.; Sheikh, M.; Taylor, R. Under-Estimation of Maternal and Perinatal Mortality Revealed by an Enhanced Surveillance System: Enumerating All Births and Deaths in Pakistan. BMC Public Health 2018, 18 (1), 428. [CrossRef]

- Farrar DS, Pell LG, Muhammad Y, Khan SH, Tanner Z, Bassani DG, et al. Association of maternal, obstetric, fetal, and neonatal mortality outcomes with Lady Health Worker coverage from a cross-sectional survey of >10,000 households in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. PLOS Global Public Health [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 20];4(2):e0002693. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan], ICF. 2017-18 Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey: key findings [Internet]. Islamabad (PK), Rockville (MD): NIPS and ICF; 2019 [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR257/SR257.pdf.

- UNICEF. Child survival and the SDGs [Internet]. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2024 [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/child-survival dgs/#:~:text=The%20proposed%20SDG%20target%20for, deaths%20per% 201%2C000%20live%20births.

- (10) Mweemba C, Mapulanga M, Jacobs C, Katowa-Mukwato P, Maimbolwa M. Access barriers to maternal healthcare services in selected hard-to-reach areas of Zambia: a mixed methods design. Pan Afr Med J [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 May 20];40:4. [CrossRef]

- Wilunda C, Oyerinde K, Putoto G, Lochoro P, Dall’Oglio G, Manenti F, et al. Availability, utilisation and quality of maternal and neonatal health care services in Karamoja region, Uganda: a health facility-based survey. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 May 20];12(1):30. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund, Mailman School of Public Health. Averting Maternal Death and Disability, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Monitoring emergency obstetric care: a handbook [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009 [cited 2025 May 20].

- Tiruneh MG, Fenta ET, Delie AM, Masresha SA, Mustofa SM, Kidie AA, et al. Service availability and readiness to provide comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care services in post-conflict at North Wollo Zone hospitals, Northeast Ethiopia: mixed survey. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 20];23(1):205. [CrossRef]

- Otolorin E, Gomez P, Currie S, Thapa K, Dao B. Essential basic and emergency obstetric and newborn care: from education and training to service delivery and quality of care. Int J Gynecol Obstet [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 May 20];130(S2):S46–S53. [CrossRef]

- Faqir M, Zainullah P, Tappis H, Mungia J, Currie S, Kim YM. Availability and distribution of human resources for provision of comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care in Afghanistan: a cross-sectional study. Confl Health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 May 20];9(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava A, Avan BI, Rajbangshi P, Bhattacharyya S. Determinants of women’s satisfaction with maternal health care: a review of literature from developing countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 May 20];15(1):97. [CrossRef]

- Majeed R, Fatima U, Mahmood N, Khan MA. Public health status and socioeconomic conditions in climate change-affected northern areas of Pakistan. Int J Biol Biotechnol. 2020;17(2):307–17.

- World Health Organization. Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA) [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015 [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/data-collection-tools/service-availability-and-readiness-assessment-(sara).

- World Bank. Service Delivery Indicators (SDI) [Internet]. Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 2018 [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/service-delivery-indicators.

- UNFPA. The Service Provision Assessment (SPA) [Internet]. New York: United Nations Population Fund; 2014 [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/resources/service-provision-assessment.

- Geleto A, Chojenta C, Musa A, Loxton D. Barriers to access and utilization of emergency obstetric care at health facilities in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of literature. Syst Rev [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 May 20];7(1):183. [CrossRef]

- Kamala SR, Julius Z, Kosia EM, Manzi F. Availability and functionality of neonatal care units in healthcare facilities in Mtwara Region, Tanzania: the quest for quality of in-patient care for small and sick newborns. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 May 20];17(11):e0269151. [CrossRef]

- Kozhimannil KB, Leonard SA, Handley SC, Passarella M, Main EK, Lorch SA, et al. Obstetric volume and severe maternal morbidity among low-risk and higher-risk patients giving birth at rural and urban US hospitals. JAMA Health Forum [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 20];4(6):e232110. [CrossRef]

- Fotso JC, Higgins-Steele A, Mohanty S. Male engagement as a strategy to improve utilization and community-based delivery of maternal, newborn and child health services: evidence from an intervention in Odisha, India. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 May 20];15(S1):S5. [CrossRef]

- Gerein N, Green A, Pearson S. The implications of shortages of health professionals for maternal health in Sub-Saharan Africa. Reprod Health Matters [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2025 May 20];14(27):40–50. [CrossRef]

- Asim M, Saleem S, Ahmed ZH, Naeem I, Abrejo F, Fatmi Z, et al. We won’t go there: barriers to accessing maternal and newborn care in District Thatta, Pakistan. Healthcare [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 May 20];9(10):1314. [CrossRef]

- Tanou M, Kamiya Y. Assessing the impact of geographical access to health facilities on maternal healthcare utilization: evidence from the Burkina Faso Demographic and Health Survey 2010. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 May 20];19(1):838. [CrossRef]

- Ebener S, Stenberg K, Brun M, Monet JP, Ray N, Sobel HL, et al. Proposing standardised geographical indicators of physical access to emergency obstetric and newborn care in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 May 20];4(Suppl 5):e000778. [CrossRef]

- Tuyisenge G, Hategeka C, Luginaah I, Babenko-Mould Y, Cechetto D, Rulisa S. Continuing professional development in maternal health care: barriers to applying new knowledge and skills in the hospitals of Rwanda. Matern Child Health J [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 May 20];22(8):1200–1207. [CrossRef]

- Love-Koh J, Griffin S, Kataika E, Revill P, Sibandze S, Walker S. Methods to promote equity in health resource allocation in low- and middle-income countries: an overview. Glob Health [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 May 20];16(1):6. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, World Bank. Delivering quality health services: a global imperative for universal health coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

| Description | Total Facilities Surveyed | Facilities for Performing Childbirth / Deliveries | Deliveries not conducted due to the absence of staffing or labor rooms | Deliveries not a mandate |

| Shigar | 10 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Skardu | 10 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Kharmang | 10 | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Ghanchey | 10 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| Diamer | 10 | 3 | 7 | 0 |

| Astore | 10 | 3 | 7 | 0 |

| Total (%) | 60 (100) | 25 (41.7) | 28 (48.3) | 7 (11.7) |

| Districts | Category Capacity | Maternity Beds* | Labor Room | Obstetric Operating Theater | Facilities with Blood Transfusion | Facilities with Nursery/NICU |

| Shigar (N=3) |

BEmONC (n = 3) | 6 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Skardu (N=5) |

BEmONC (n = 4) | 9 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CEmONC (n = 1) | 22 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Kharmang (N=5) |

BEmONC (n = 5) | 8 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Ghanchey (N=6) |

BEmONC (n = 5) | 5 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CEmONC (n = 1) | 15 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Diamer (N=3) |

BEmONC (n = 2) | 2 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CEmONC (n = 1) | 33 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Astore (N=3) |

BEmONC (n = 2) | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CEmONC (n = 1) | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Districts |

Category Capacity |

Total Deliveries/Annum N (%) |

N = Number of Facilities | |||

|

Very Low Volume (<60) /Annum |

Low Volume (60 – 364) /Annum | Medium Volume (365-999) /Annum |

High Volume (>1000) /Annum |

|||

| Shigar (N=3) |

BEmONC (n = 3) | 336 (1.8%) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (16.7%) | - | 0 (0%) |

| Skardu (N=5) |

BEmONC (n = 4) | 610 (3.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (16.7%) | - | 0 (0%) |

| CEmONC (n = 1) | 3,994 (21.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 1 (25%) | |

| Kharmang (N=5) | BEmONC (n = 5) | 414 (2.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | 3 (25%) | - | 0 (0%) |

| Ghanchey (N=6) |

BEmONC (n = 5) | 274 (1.5%) | 4 (44.4%) | 1 (8.3%) | - | 0 (0%) |

| CEmONC (n = 1) | 1,248 (6.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 1 (25%) | |

| Diamer (N=3) |

BEmONC (n = 2) | 477 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (16.7%) | - | 0 (0%) |

| CEmONC (n = 1) | 10,000 (53%)* | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 1 (25%) | |

| Astore (N=3) |

BEmONC (n = 2) | 170 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (16.7%) | - | 0 (0%) |

| CEmONC (n = 1) | 1339 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 1 (25%) | |

|

Total |

18,862 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 12 (100%) | - | 4 (100%) | |

| Districts | Category | Medical Officer | Gynecologists/Obstetricians | Pediatricians | Nurses | Midwives/ LHVs | Anesthetist/Anesthesiologists | Anesthetists Technicians |

| Shigar (N=3) |

BEmONC (n = 3) | 4 | N/A | N/A | 0 | 4 | N/A | N/A |

| Skardu (N=5) |

BEmONC (n = 4) | 0 | N/A | 1 | 0 | 12 | N/A | 3 |

| CEmONC (n = 1) | 7 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Kharmang (N=5) |

BEmONC (n = 5) | 8 | N/A | N/A | 3 | 9 | N/A | 6 |

| Ghanchey (N=6) |

BEmONC (n = 5) | 3 | N/A | N/A | 4 | 10 | N/A | N/A |

| CEmONC (n = 1) | 10 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 14 | 2 | 2 | |

| Diamer (N=3) |

BEmONC (n = 2) | 2 | N/A | N/A | 0 | 6 | N/A | N/A |

| CEmONC (n = 1) | 35 | 1 | 2 | 21 | 15 | 1 | 2 | |

| Astore (N=3) |

BEmONC (n = 2) | 0 | N/A | N/A | 2 | 5 | N/A | N/A |

| CEmONC (n = 1) | 13 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Description | Managed Complication in past 12 moths | Confidence in Managing Complication | ||||

|

Doctors and Nurses (N=15) |

LHV/ Midwivesb (N=31) |

Medical Traineesc (N=32) |

Doctorsa (N=15) |

LHV /Midwivesb (N=31) |

Medical Traineesc (N=32) |

|

| Eclampsia/Pre-eclampsia | 27% | 10% | 0% | 27% | 6% | 0% |

| Post-partum hemorrhage | 27% | 32% | 0% | 13% | 29% | 3% |

| Obstructed labor | 0% | 10% | 0% | 7% | 6% | 0% |

| Newborn resuscitation | 20% | 10% | 3% | 27% | 6% | 6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).