Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

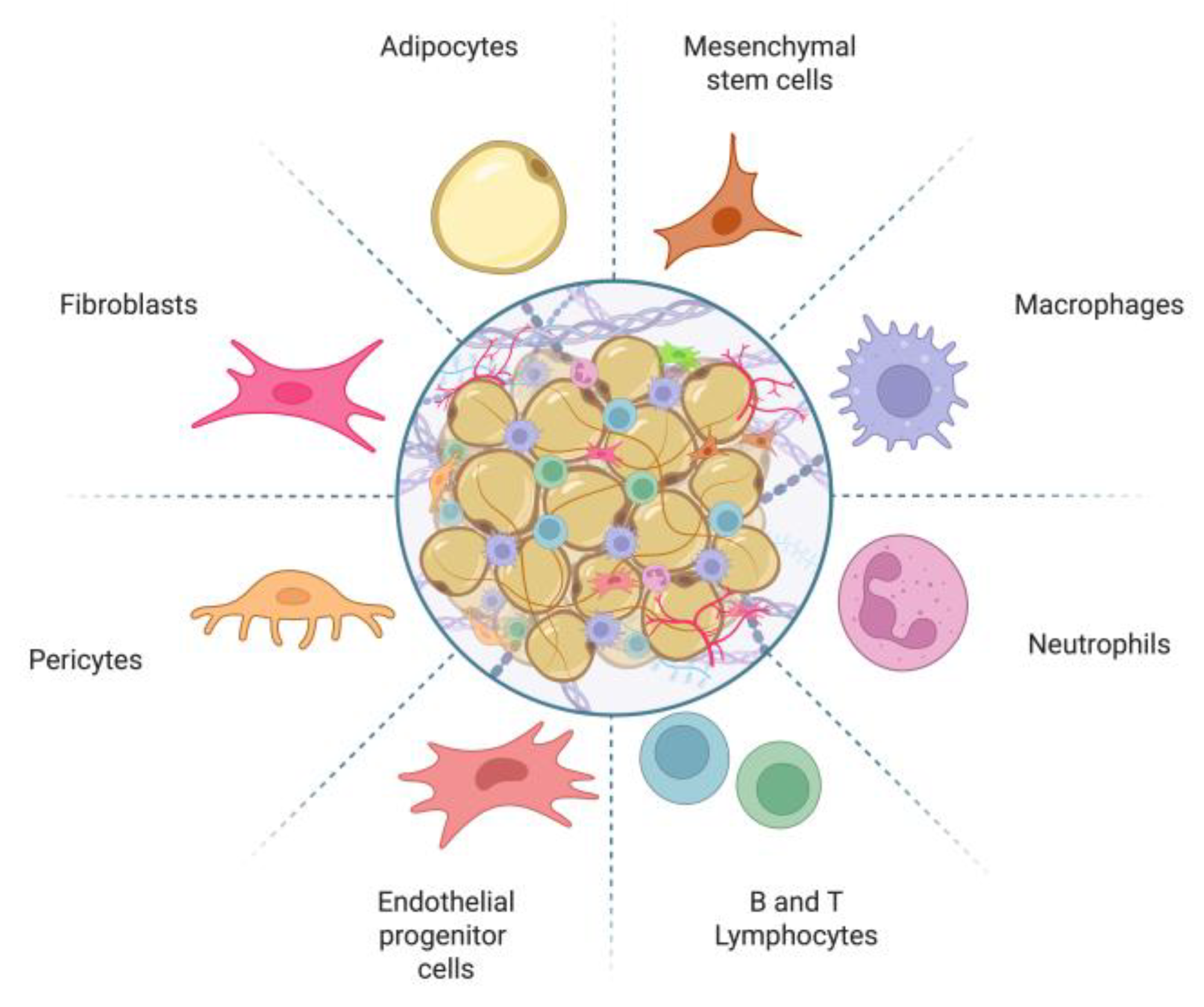

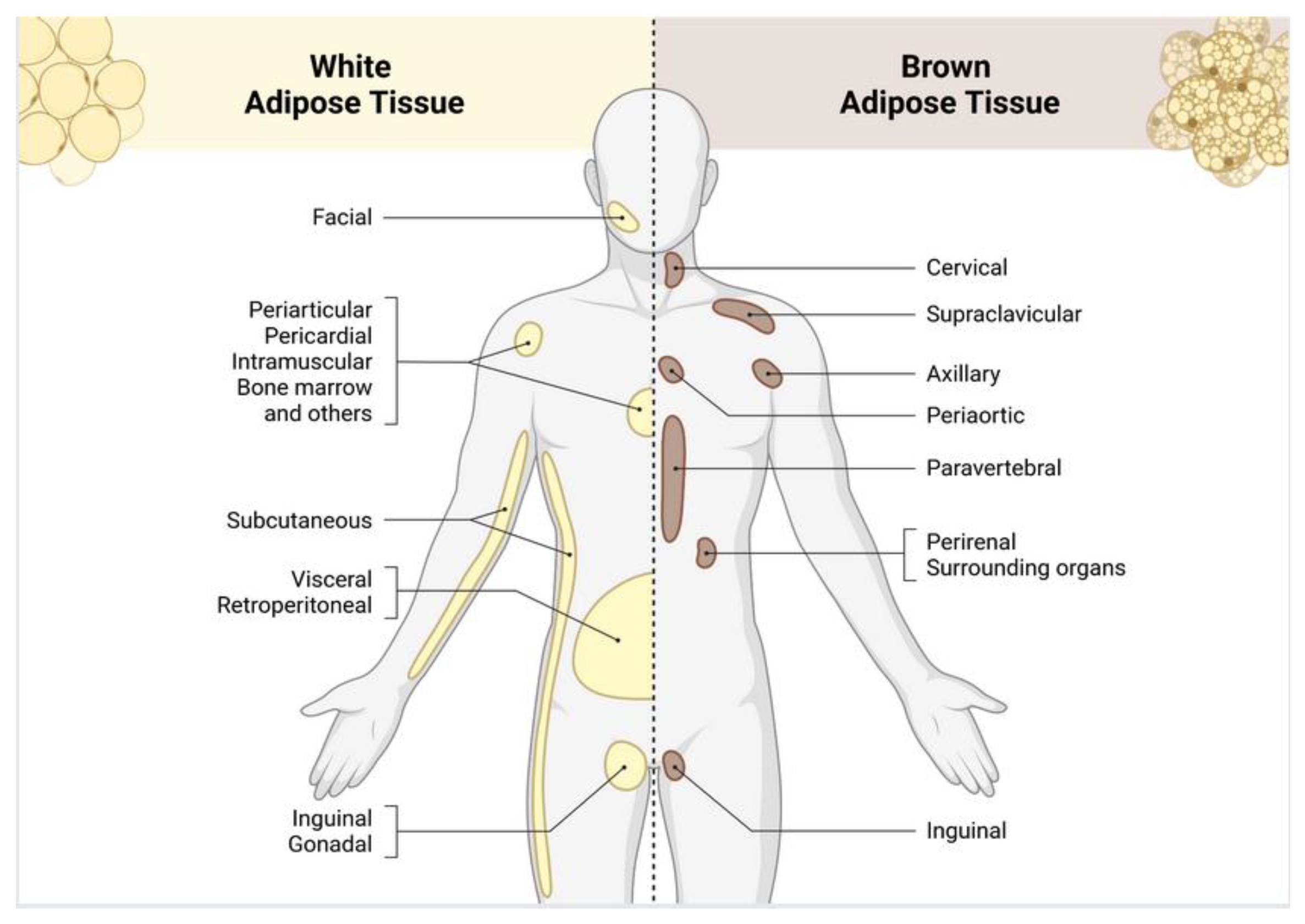

1. Introduction

2. Lipogenesis

3. Adipose Tissue as an Endocrine Organ

| Adipose Tissue | Secreted adipokines/peptides | Principal effects | References |

| WAT | Adiponectin, Leptin, Adipsin, Omentin, TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, PAI-1 , Resistin, Visfatin, RBP4 | Regulation of appetite and energy balance; innate/adaptive inflammation; modulation of glucose and lipid metabolism; increased insulin resistance; influences on cardiovascular remodeling and thrombosis | [1,37,40,47] |

| BAT | FGF21, BMP-7, VEGF-A, Irisin, NRG4, Nesfatin-1, METRNL, Chemerin, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 | Non-shivering thermogenesis; increased energy expenditure; improvement of glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity; favorable lipid handling; angiogenesis; anti-inflammatory and tissue-protective signaling | [10,41] |

| BeAT | FGF21, NRG4, METRNL, CXCL14, IL-6 | Inducible thermogenesis and browning of WAT; increased energy expenditure; improved glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity; anti-inflammatory actions | [8,10,46] |

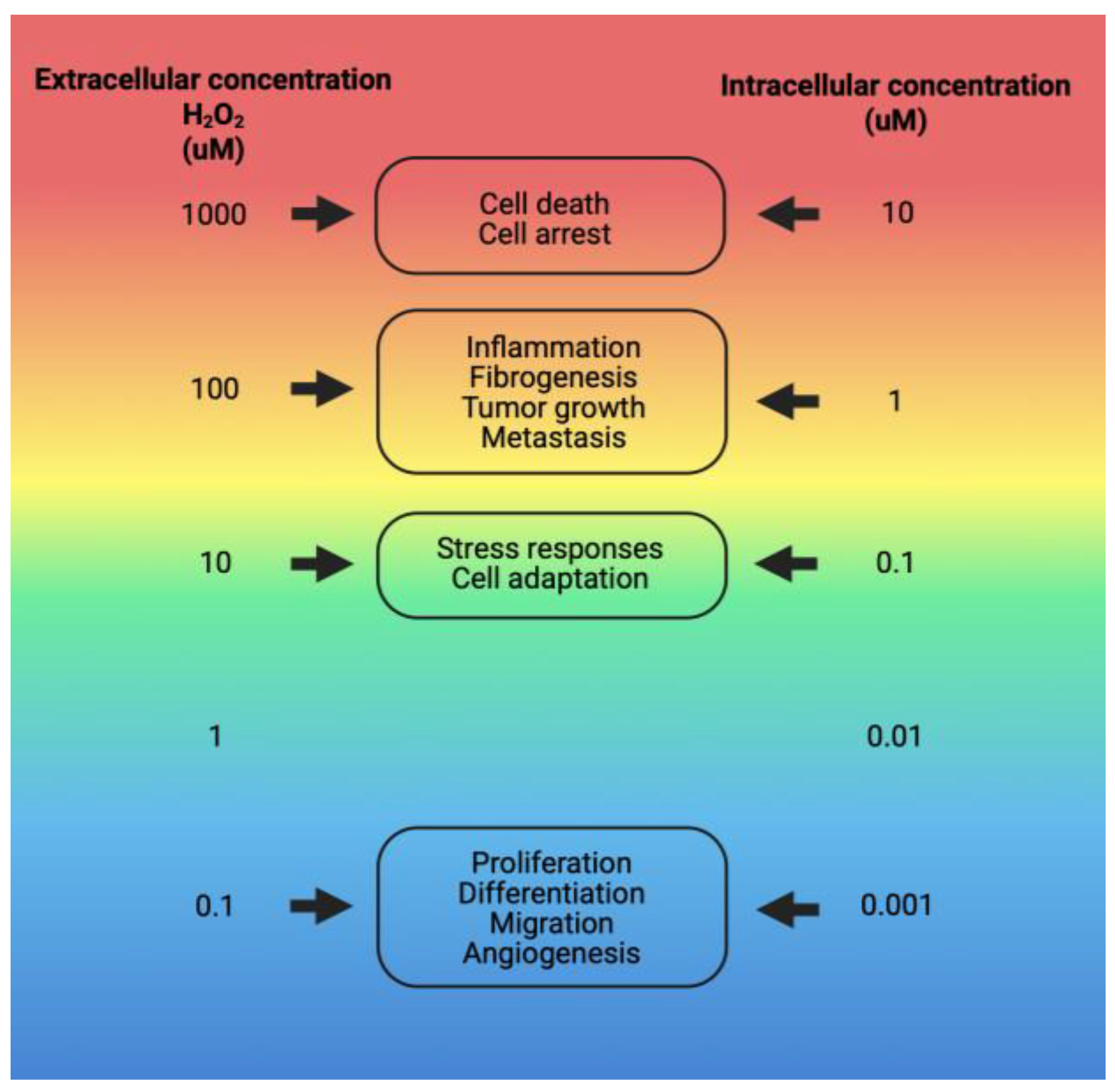

4. Oxidative Stress in Adipose Tissue

5. Inflammation in Adipose Tissue

| Cell type | Markers | Primary function in adipose tissue | Effects | References |

| M1 macrophages | TNF-α; IL-6; iNOS; COX-2; MCP-1/CCL2; MMP-9; VEGF-A | Pro-inflammatory responses; high cytokine/chemokine output; extracellular matrix degradation/remodeling; angiogenic factor release under stress | Promote inflammation and adipose-tissue dysfunction | [81,83] |

| M2 macrophages | IL-10; TGF-β | Resolution of inflammation, tissue repair/remodeling, immune regulation and restoration of homeostasis | Terminate inflammatory processes; pro-resolving, reparative milieu | [81,83] |

| CD8⁺ T lymphocytes | Antigen recognition via MHC-I | Elimination of damaged or infected cells within adipose depots | In obesity, favor inflammatory amplification | [84,85] |

| CD4⁺ T lymphocytes | Antigen recognition via MHC-II | Subsets: Treg—immune regulation Th1—cell-mediated responses Th2—humoral responses Th17—chronic inflammatory programming |

Th1, Th17: pro-inflammatory; Th2, Treg: anti-inflammatory/pro-resolving |

[85,86] |

6. Cholesterol and Lipotoxicity

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full name |

| •OH | Hydroxyl radical |

| 4-HNE | 4-Hydroxynonenal |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| BeAT | Beige adipose tissue |

| BMP-7 | Bone morphogenetic protein 7 |

| CD4+ | CD4+ T lymphocytes (Helper T cells) |

| CD8+ | CD8+ T lymphocytes (Cytotoxic T Cells) |

| CLS | Crown-like structures |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CXCL14 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 14 |

| DAG | Diacylglycerol |

| DAMP | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DM2 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| DNL | De novo lipogenesis |

| FGF21 | Fibroblast growth factor 21 |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| HIF-1 | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 |

| IDL | Intermediate-density lipoprotein |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IR | Insulin Resistence |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| METRNL | Meteorin-like protein |

| MHC-I | Major histocompatibility complex class I |

| MHC-II | Major histocompatibility complex class II |

| MMP-9 | Matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

| NLRP3 | NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| NRG4 | Neuregulin 4 |

| O2•− | Superoxide anion |

| oxLDL | Oxidized low-density lipoprotein |

| PAI-1 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 |

| PRR | Pattern recognition receptors |

| PP2A | Protein Phosphatase 2 |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog |

| PTP1B | Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| RBP4 | Retinol-binding protein 4 |

| RE | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| Th1 | T helper 1 cells |

| Th2 | T helper 2 cells |

| Th17 | T helper 17 cells |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TLR | Toll-like receptors |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| Treg | Regulatory T cells |

| UCP-1 | Uncoupling protein 1 |

| UPR | Unfolded Protein Response |

| VEGF-A | Vascular endothelial growth factor A |

| VLDL | Very-low-density lipoprotein |

| WAT | White adipose tissue |

References

- Harvey, I., A. Boudreau, and J.M. Stephens, Adipose tissue in health and disease. Open Biology, 2020, 10, 200291.

- Horowitz, J.F. , Adipose tissue lipid metabolism during exercise, in Exercise Metabolism. 2022, Springer. 137-159.

- Luo, L. and M. Liu, Adipose tissue in control of metabolism. Journal of Endocrinology, 2016, 231, R77–R99.

- Chait, A. and L.J. den Hartigh, Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med, 2020, 7, 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevor, L.V., et al., Adipose Tissue: A Source of Stem Cells with Potential for Regenerative Therapies for Wound Healing. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2020, 9, 2161. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunnell, B.A. , Adipose Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Cells, 2021, 10(12).

- Hsiao, W.Y. and D.A. Guertin, De Novo Lipogenesis as a Source of Second Messengers in Adipocytes. Curr Diab Rep, 2019, 19, 138. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilkington, A.-C., H.A. Paz, and U.D. Wankhade, Beige adipose tissue identification and marker Specificity—Overview. Frontiers in endocrinology, 2021, 12, 599134. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpentier, A.C., et al., Brown Adipose Tissue—A Translational Perspective. Endocrine Reviews, 2022, 44, 143–192.

- Ghesmati, Z., et al., An update on the secretory functions of brown, white, and beige adipose tissue: Towards therapeutic applications. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, 2024, 25, 279–308. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, S.A., et al., Browning of the white adipose tissue regulation: new insights into nutritional and metabolic relevance in health and diseases. Nutrition & Metabolism, 2022, 19, 61.

- Brown, Z. and T. Yoneshiro, Brown Fat and Metabolic Health: The Diverse Functions of Dietary Components. Endocrinol Metab, 2024, 39, 839–846.

- Bielczyk-Maczynska, E. , White Adipocyte Plasticity in Physiology and Disease. Cells, 2019, 8, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepa-Kishi, D.M. and R.B. Ceddia, White and beige adipocytes: are they metabolically distinct? Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation, 2018, 33(2).

- Frigolet, M.E. and R. Gutierrez-Aguilar, The colors of adipose tissue. Gac Med Mex, 2020, 156, 142–149.

- Parra-Peralbo, E., A. Talamillo, and R. Barrio, Origin and development of the adipose tissue, a key organ in physiology and disease. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2021, 9, 786129.

- Kawai, T., M.V. Autieri, and R. Scalia, Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology, 2021, 320, C375–C391. [CrossRef]

- Małodobra-Mazur, M., et al., Metabolic differences between subcutaneous and visceral adipocytes differentiated with an excess of saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids. Genes, 2020, 11, 1092. [CrossRef]

- Mora, I. , et al., Emerging models for studying adipose tissue metabolism. Biochemical Pharmacology, 2024, 116123.

- Lim, K., et al., Lipodistrophy: a paradigm for understanding the consequences of “overloading” adipose tissue. Physiological Reviews, 2021, 101, 907–993.

- Huo, C., et al., Effect of Acute Cold Exposure on Energy Metabolism and Activity of Brown Adipose Tissue in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Physiol, 2022, 13, 917084. [CrossRef]

- U-Din, M., et al., Cold-stimulated brown adipose tissue activation is related to changes in serum metabolites relevant to NAD+ metabolism in humans. Cell Reports, 2023, 42, 113131. [CrossRef]

- Nirengi, S. and K. Stanford, Brown adipose tissue and aging: A potential role for exercise. Experimental Gerontology, 2023, 178, 112218. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, Y.G., et al., Physiological and pathological roles of lipogenesis. Nature Metabolism, 2023, 5, 735–759. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batchuluun, B., S.L. Pinkosky, and G.R. Steinberg, Lipogenesis inhibitors: therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2022, 21, 283–305. [CrossRef]

- Song, Z., A.M. Xiaoli, and F. Yang, Regulation and Metabolic Significance of De Novo Lipogenesis in Adipose Tissues. Nutrients, 2018, 10, 1383. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M. and C.M. Metallo, Tracing insights into de novo lipogenesis in liver and adipose tissues. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 2020, 108, 65–71.

- Taher, J. Farr, and K. Adeli, Central nervous system regulation of hepatic lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Current Opinion in Lipidology, 2017, 28(1).

- Cook, J.R., A.B. Kohan, and R.A. Haeusler, An Updated Perspective on the Dual-Track Model of Enterocyte Fat Metabolism. Journal of Lipid Research, 2022, 63, 100278. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergès, B. , Intestinal lipid absorption and transport in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia, 2022, 65, 1587–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wit, M., et al., When fat meets the gut—focus on intestinal lipid handling in metabolic health and disease. EMBO Molecular Medicine, 2022, 14, e14742. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscella, A., et al., The Regulation of Fat Metabolism during Aerobic Exercise. Biomolecules, 2020, 10, 1699.

- Li, L., et al., The impact of oxidative stress on abnormal lipid metabolism-mediated disease development. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2025, 766, 110348.

- Akyol, O. , et al., Lipids and lipoproteins may play a role in the neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2023, 17.

- de Lima, E.P., et al., Glycolipid Metabolic Disorders, Metainflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Cardiovascular Diseases: Unraveling Pathways. Biology, 2024, 13, 519.

- Yin, F. , Lipid metabolism and Alzheimer’s disease: clinical evidence, mechanistic link and therapeutic promise. Febs j, 2023, 290, 1420–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, F., et al., Deciphering endocrine function of adipose tissue and its significant influences in obesity-related diseases caused by its dysfunction. Differentiation, 2025, 141, 100832. [CrossRef]

- Booth, A. , et al. , Adipose tissue: an endocrine organ playing a role in metabolic regulation. 2016, 26, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hemat Jouy, S. , et al. , Adipokines in the Crosstalk between Adipose Tissues and Other Organs: Implications in Cardiometabolic Diseases. Biomedicines, 2024, 12, 2129. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J. , et al. The Role of Adipokines in Health and Disease. Biomedicines, 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroya, F. , et al. , Brown adipose tissue as a secretory organ. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 2017, 13, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mishra, D. , et al. , Parabrachial Interleukin-6 Reduces Body Weight and Food Intake and Increases Thermogenesis to Regulate Energy Metabolism. Cell Reports, 2019, 26, 3011–3026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sulen, A. and M. Aouadi, Fed Macrophages Hit the Liver’s Sweet Spot with IL-10. Molecular Cell, 2020, 79, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdaviani, K. , et al. , Autocrine effect of vascular endothelial growth factor-A is essential for mitochondrial function in brown adipocytes. Metabolism, 2016, 65, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , et al., Meteorin-like/Metrnl, a novel secreted protein implicated in inflammation, immunology, and metabolism: A comprehensive review of preclinical and clinical studies. Frontiers in Immunology, 2023, Volume 14 - 2023.

- Yang, S. , et al. , Molecular Regulation of Thermogenic Mechanisms in Beige Adipocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024, 25, 6303. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, B. and N. C. Bal, Adipokines from white adipose tissue in regulation of whole body energy homeostasis. Biochimie, 2023, 204, 92–107. [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Rjeileh, U. and G. A. Contreras, Redox Regulation of Lipid Mobilization in Adipose Tissues. Antioxidants, 2021, 10, 1090. [Google Scholar]

- Di Meo, S. , et al. , Role of ROS and RNS Sources in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2016, 2016, 1245049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Revilla Flores, E.M. , Especies reactivas de oxígeno, importancia e implicación patológica. Revista Científica Ciencia Médica, 2021, 24, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Sies, H. and D. Jones, Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, T. , et al., Oxidative stress and inflammation: what polyphenols can do for us? Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2016, 2016.

- Rivas-Arancibia, S. , et al., Ozone Pollution, Oxidative Stress, Regulatory T Cells and Antioxidants. Antioxidants (Basel), 2022, 11(8).

- Rhoads, J. and A. S. Major, How Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Activates Inflammatory Responses. Crit Rev Immunol, 2018, 38, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Venditti, and S. Di Meo, The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Life Cycle of the Mitochondrion. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020, 21, 2173.

- Qian, W. , et al. , Chemoptogenetic damage to mitochondria causes rapid telomere dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2019, 116, 18435–18444. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. , et al. , Endoplasmic reticulum stress: molecular mechanism and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2023, 8, 352. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S. , et al. , Ceramides and mitochondrial homeostasis. Cellular Signalling, 2024, 117, 111099. [Google Scholar]

- Yazıcı, D., S. Ç. Demir, and H. Sezer, Insulin Resistance, Obesity, and Lipotoxicity, in Obesity and Lipotoxicity, A.B. Engin and A. Engin, Editors. 2024, Springer International Publishing: Cham. 391-430.

- Chaurasia, B. and S. A. Summers, Ceramides in Metabolism: Key Lipotoxic Players. Annu Rev Physiol, 2021, 83, 303–330. [Google Scholar]

- Engin, A.B. , What is lipotoxicity? Obesity and lipotoxicity, 2017: 197-220.

- Liu, F. , et al. , Adipose Morphology: a Critical Factor in Regulation of Human Metabolic Diseases and Adipose Tissue Dysfunction. Obesity Surgery, 2020, 30, 5086–5100. [Google Scholar]

- Chaurasia, B., C. L. Talbot, and S.A. Summers, Adipocyte Ceramides—The Nexus of Inflammation and Metabolic Disease. Frontiers in Immunology, 2020. 11.

- Ireland, S.C. , et al. , Hydrogen peroxide induces Arl1 degradation and impairs Golgi-mediated trafficking. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 2020, 31, 1931–1942. [Google Scholar]

- Masschelin, P.M. , et al. , The Impact of Oxidative Stress on Adipose Tissue Energy Balance. Front Physiol, 2019, 10, 1638. [Google Scholar]

- Hauck, A.K. , et al. , Adipose oxidative stress and protein carbonylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2019, 294, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Nègre-Salvayre, A. and R. Salvayre, Reactive Carbonyl Species and Protein Lipoxidation in Atherogenesis. Antioxidants, 2024, 13, 232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jebari-Benslaiman, S. , et al. , Pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. International journal of molecular sciences, 2022, 23, 3346. [Google Scholar]

- Soulage, C.O. , et al. , Two toxic lipid aldehydes, 4-hydroxy-2-hexenal (4-HHE) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), accumulate in patients with chronic kidney disease. Toxins, 2020, 12, 567. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, C. , et al. , Enhancing adipose tissue functionality in obesity: senotherapeutics, autophagy and cellular senescence as a target. Biological Research, 2024, 57, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Frąk, W. , et al. , Pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases: new insights into molecular mechanisms of atherosclerosis, arterial hypertension, and coronary artery disease. Biomedicines, 2022, 10, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Y.I. and J. Y.J. Shyy, Context-Dependent Role of Oxidized Lipids and Lipoproteins in Inflammation. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2017, 28, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , et al. , Metabolism-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs). Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2020, 31, 712–724. [Google Scholar]

- Lolescu, B.M. , et al. , Adipose tissue as target of environmental toxicants: focus on mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative inflammation in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, 2025, 480, 2863–2879. [Google Scholar]

- Lennicke, C. and H. M. Cochemé, Redox regulation of the insulin signalling pathway. Redox Biol, 2021, 42, 101964. [Google Scholar]

- Chouchani, E.T. , et al. , Mitochondrial ROS regulate thermogenic energy expenditure and sulfenylation of UCP1. Nature, 2016, 532, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Q. and K.L. Spalding, The regulation of adipocyte growth in white adipose tissue. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2022. Volume 10 - 2022.

- Longo, M. , et al., Adipose Tissue Dysfunction as Determinant of Obesity-Associated Metabolic Complications. Int J Mol Sci, 2019. 20(9).

- Dahdah, N. , et al. , Interrelation of adipose tissue macrophages and fibrosis in obesity. Biochemical Pharmacology, 2024, 225, 116324. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J.H., J. H. Sung, and J.Y. Huh, Diverse Functions of Macrophages in Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: Bridging Inflammation and Metabolism. Immune Netw, 2025, 25, e12. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, H.Y. , et al., Molecular Crosstalk Between Macrophages and Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2020. 8.

- Caër, C. , et al. , Immune cell-derived cytokines contribute to obesity-related inflammation, fibrogenesis and metabolic deregulation in human adipose tissue. Scientific reports, 2017, 7, 3000. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock, A. , et al., Leukocyte heterogeneity in adipose tissue, including in obesity. Circulation research, 2020. 126, 1590-1612.

- Pishesha, N., T. J. Harmand, and H.L. Ploegh, A guide to antigen processing and presentation. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2022, 22, 751–764. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.-S. and N. Shastri, The role of T cells in obesity-associated inflammation and metabolic disease. Immune Network, 2022. 22(1).

- Zhu, X. and J. Zhu, CD4 T helper cell subsets and related human immunological disorders. International journal of molecular sciences, 2020, 21, 8011. [Google Scholar]

- Varra, F.-N. , et al. , Molecular and pathophysiological relationship between obesity and chronic inflammation in the manifestation of metabolic dysfunctions and their inflammation--mediating treatment options. Molecular Medicine Reports, 2024, 29, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zatterale, F. , et al. , Chronic adipose tissue inflammation linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Frontiers in physiology, 2020, 10, 505887. [Google Scholar]

- Chakarov, S., C. Blériot, and F. Ginhoux, Role of adipose tissue macrophages in obesity-related disorders. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 2022. 219(7).

- Huynh, P.M., F. Wang, and Y.A. An, Hypoxia signaling in the adipose tissue. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology, 2024. 16(8).

- Sun, K., X. Li, and P. E. Scherer, Extracellular matrix (ECM) and fibrosis in adipose tissue: overview and perspectives. Comprehensive Physiology, 2023, 13, 4387–4407. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y., H. Li, and N. Xia, The interplay between adipose tissue and vasculature: Role of oxidative stress in obesity. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 2021, 8, 650214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, J. , et al. , Cholesterol metabolism: physiological regulation and diseases. MedComm (2020), 2024, 5, e476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Long, T., E. W. Debler, and X. Li, Structural enzymology of cholesterol biosynthesis and storage. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 2022, 74, 102369. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, W.Y., H. Hartmann, and S. C. Ling, Central nervous system cholesterol metabolism in health and disease. IUBMB Life, 2022, 74, 826–841. [Google Scholar]

- Bays, H.E. , et al. , Obesity, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease: A joint expert review from the Obesity Medicine Association and the National Lipid Association 2024. Obes Pillars, 2024, 10, 100108. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y. , et al. , Regulation of cholesterol homeostasis in health and diseases: from mechanisms to targeted therapeutics. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2022, 7, 265. [Google Scholar]

- White, U. , Adipose tissue expansion in obesity, health, and disease. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2023, 11, 1188844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, S.S. , et al., Adipose Tissue Remodeling: Its Role in Energy Metabolism and Metabolic Disorders. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 2016. Volume 7 - 2016.

- Corvera, S., J. Solivan-Rivera, and Z. Yang Loureiro, Angiogenesis in adipose tissue and obesity. Angiogenesis, 2022, 25, 439–453. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q. and C. S. Lim, Molecular Activation of NLRP3 Inflammasome by Particles and Crystals: A Continuing Challenge of Immunology and Toxicology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 2024, 64, 417–433. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.J., I. D. C. Fraser, and C.E. Bryant, Lipid regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activity through organelle stress. Trends Immunol, 2021, 42, 807–823. [Google Scholar]

- Lindhorst, A. , et al. , Adipocyte death triggers a pro-inflammatory response and induces metabolic activation of resident macrophages. Cell Death & Disease, 2021, 12, 579. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-J. , et al. , Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4): new insight immune and aging. Immunity & Ageing, 2023, 20, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Goicoechea, L. , et al. , Mitochondrial cholesterol: Metabolism and impact on redox biology and disease. Redox Biology, 2023, 61, 102643. [Google Scholar]

- Rauchbach, E. , et al., Cholesterol Induces Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Damage and Death in Hepatic Stellate Cells to Mitigate Liver Fibrosis in Mice Model of NASH. Antioxidants (Basel), 2022. 11(3).

- Brunner, S. , et al., Mitochondrial lipidomes are tissue specific - low cholesterol contents relate to UCP1 activity. Life Sci Alliance, 2024. 7(8).

- Baila-Rueda, L. , et al. , Association of Cholesterol and Oxysterols in Adipose Tissue With Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome Traits. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2022, 107, e3929–e3936. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, W.J. , et al. , Metabolism of Non-Enzymatically Derived Oxysterols: Clues from sterol metabolic disorders. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2019, 144, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mutemberezi, V., O. Guillemot-Legris, and G. G. Muccioli, Oxysterols: From cholesterol metabolites to key mediators. Progress in Lipid Research, 2016, 64, 152–169. [Google Scholar]

- Nury, T., et al., Attenuation of 7-ketocholesterol- and 7β-hydroxycholesterol-induced oxiapoptophagy by nutrients, synthetic molecules and oils: Potential for the prevention of age-related diseases. Ageing Research Reviews, 2021, 68, 101324. [CrossRef]

- Pariente, A. , et al., Identification of 7-Ketocholesterol-Modulated Pathways and Sterculic Acid Protective Effect in Retinal Pigmented Epithelium Cells by Using Genome-Wide Transcriptomic Analysis. Int J Mol Sci, 2023. 24(8).

- Nguyen, C., et al., 25-Hydroxycholesterol in health and diseases. Journal of Lipid Research, 2024, 65, 100486. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, I.A., et al., Bone metabolism – an underappreciated player. npj Metabolic Health and Disease, 2024, 2, 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Fuente, D.C., et al., Impaired oxysterol-liver X receptor signaling underlies aberrant cortical neurogenesis in a stem cell model of neurodevelopmental disorder. Cell Reports, 2024, 43, 113946. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.J., L.J. Sharpe, and M.J. Rogers, Oxysterols: From physiological tuners to pharmacological opportunities. British Journal of Pharmacology, 2021, 178, 3089–3103. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).