Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

07 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Swalife PromptStudio — Target Identification & Validation

Material and Methods

- Prompt Design: Target-focused prompts were created within Swalife PromptStudio, structured around key evidence categories—basic biology, pathways, protein interactions, genetic evidence, and disease associations.

- Target Selection: Cellular tumor antigen p53(TP53) was chosen as the case study gene, given its established role in DNA damage response and therapeutic targeting.

- Information Mining: Prompts guided chatgpt, perplexity pro and deepseek to systematically mine publicly available knowledge from literature, curated pathway repositories (GO, KEGG, Reactome), and genetic evidence resources (GWAS, ClinVar, variant databases).

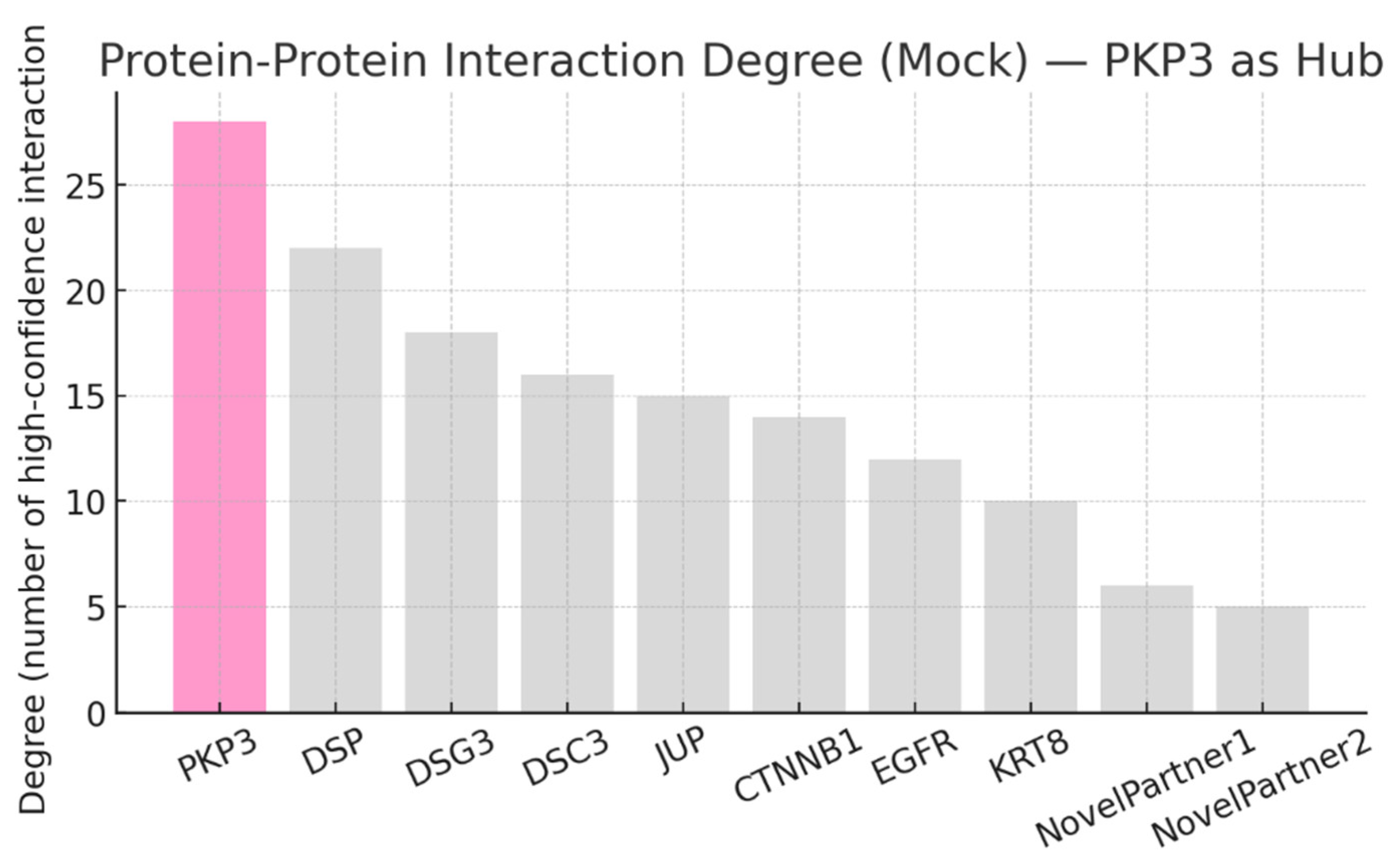

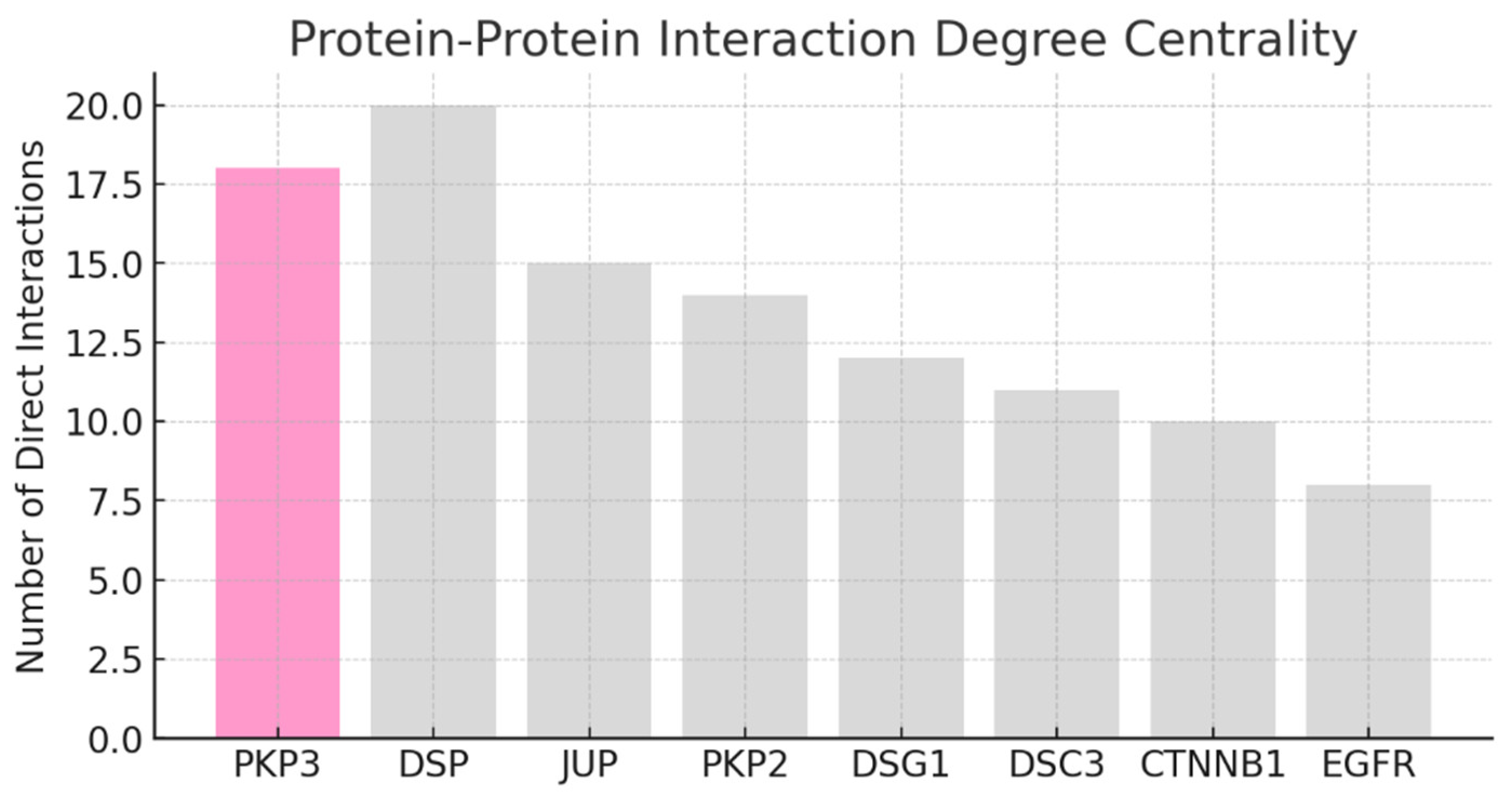

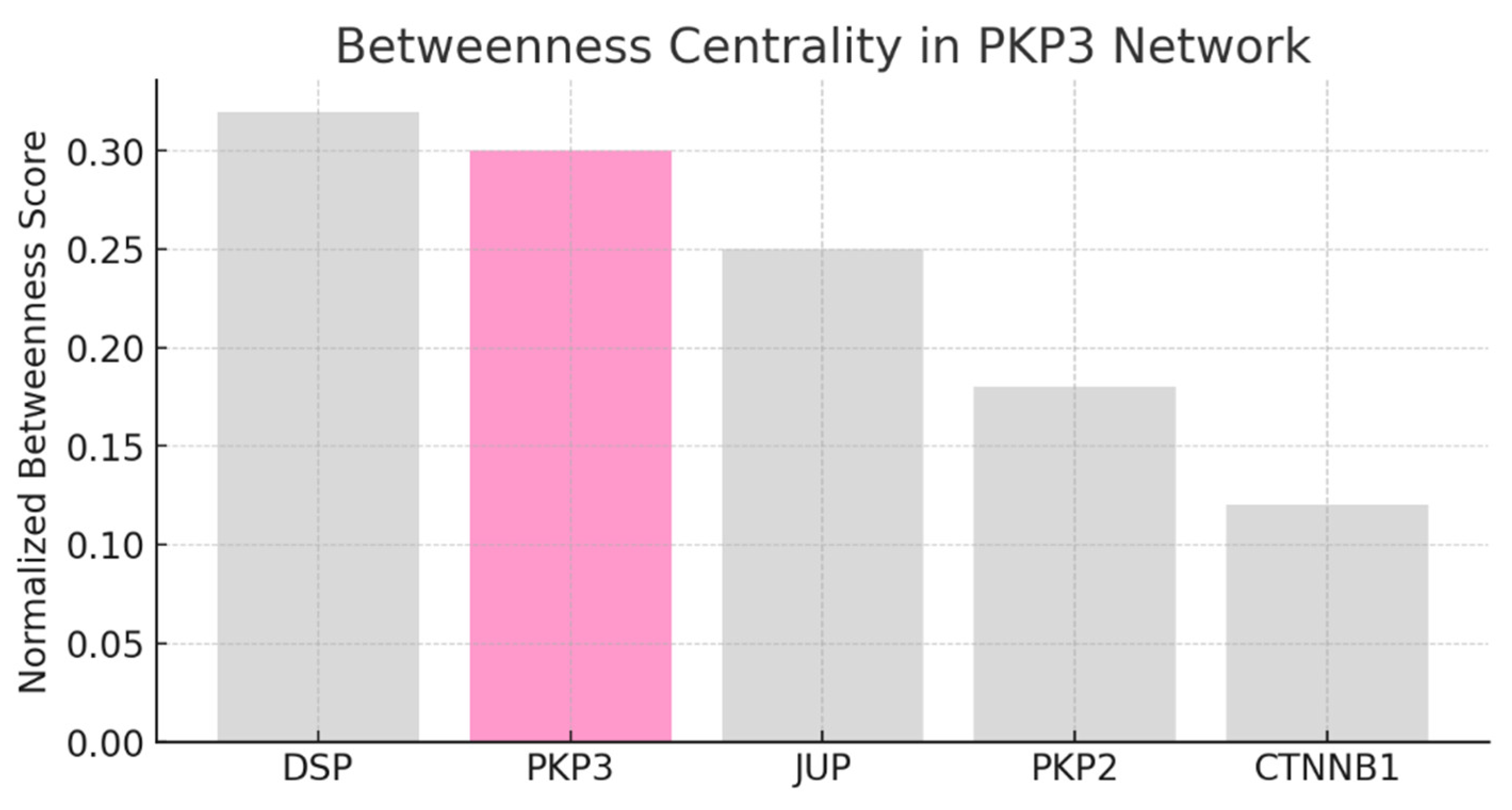

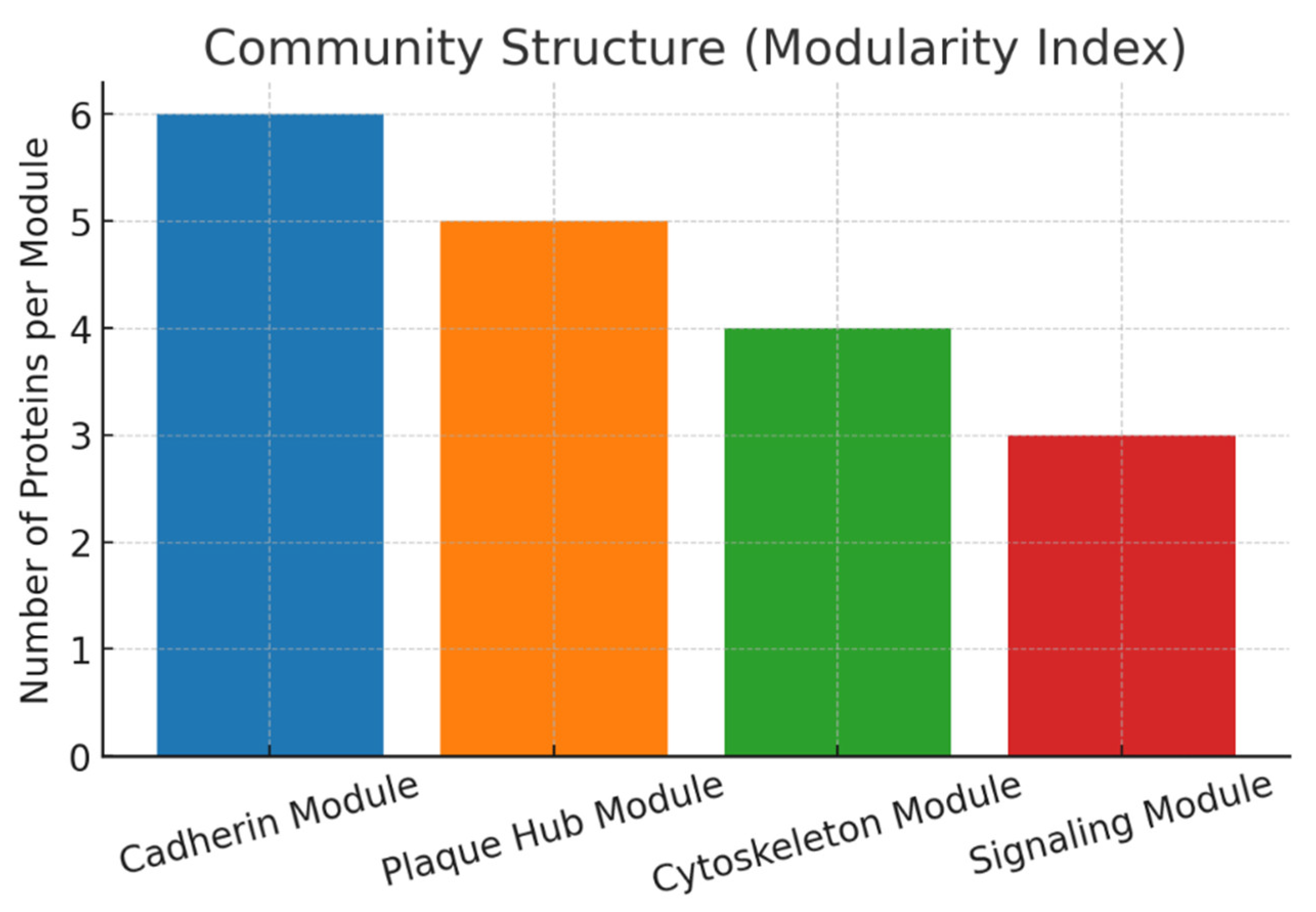

- Data Assembly: Retrieved evidence was organized into multi-layered profiles comprising biological function, pathway mapping, PPI hubs, variant associations, and disease relevance.

Result and Discussion

Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ji Y, et al. “Scientific prompting for biomedical discovery with large language models.” Nature Biotechnol. 2023.

- Wang J, et al. “Multi-agent systems in AI-driven drug discovery.” Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2024.

- Badhe, P. (2025). Prompt-Driven Target identification: A Multi-Omics and Network Biology case study of PARP1 using SwaLife PromptStudio. bioRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory). [CrossRef]

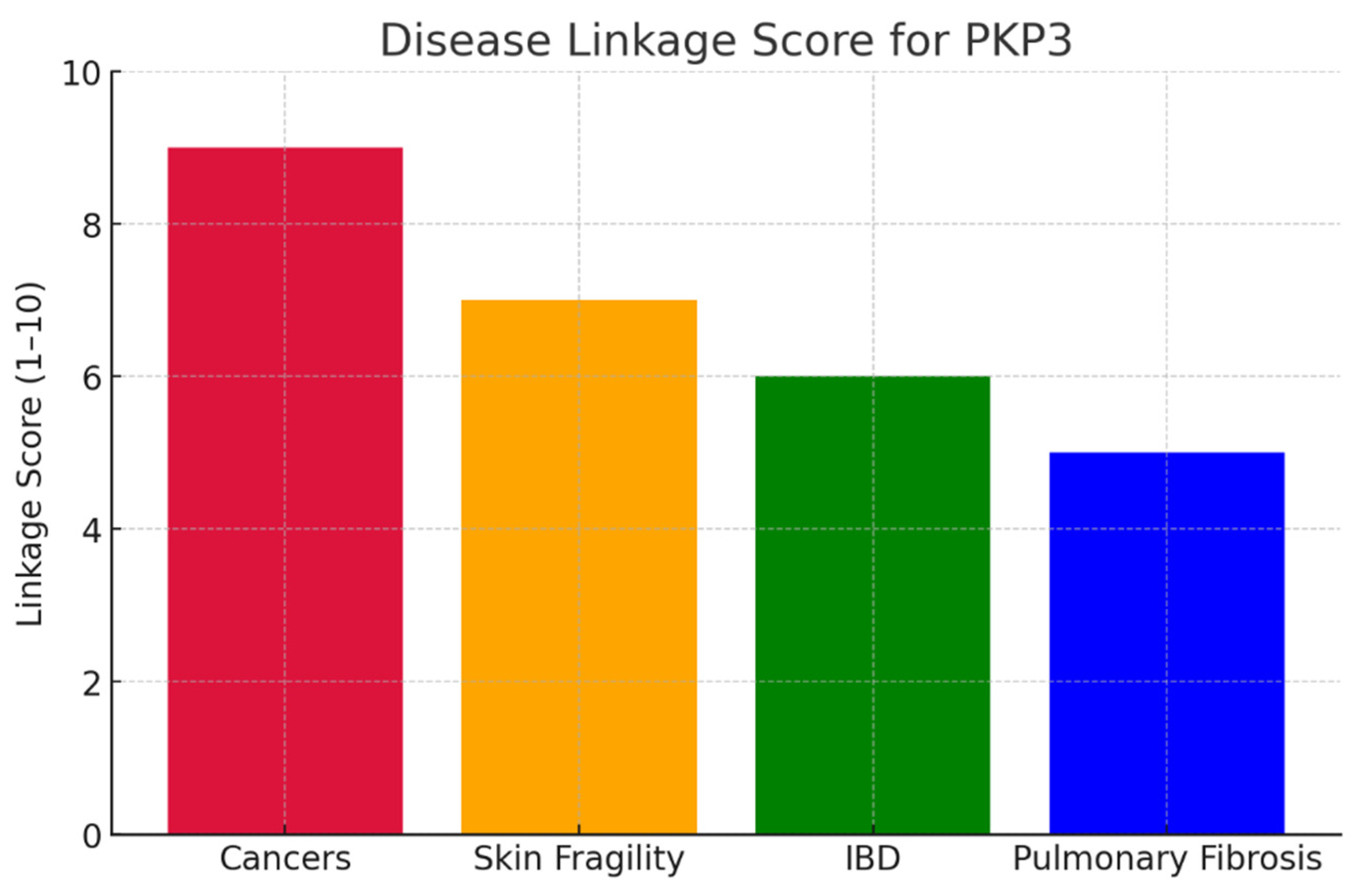

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Tian, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Role and function of plakophilin 3 in cancer progression and skin disease. Cancer Sci. 2023, 115, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UniProt. (n.d.). UniProt. https://www.uniprot.

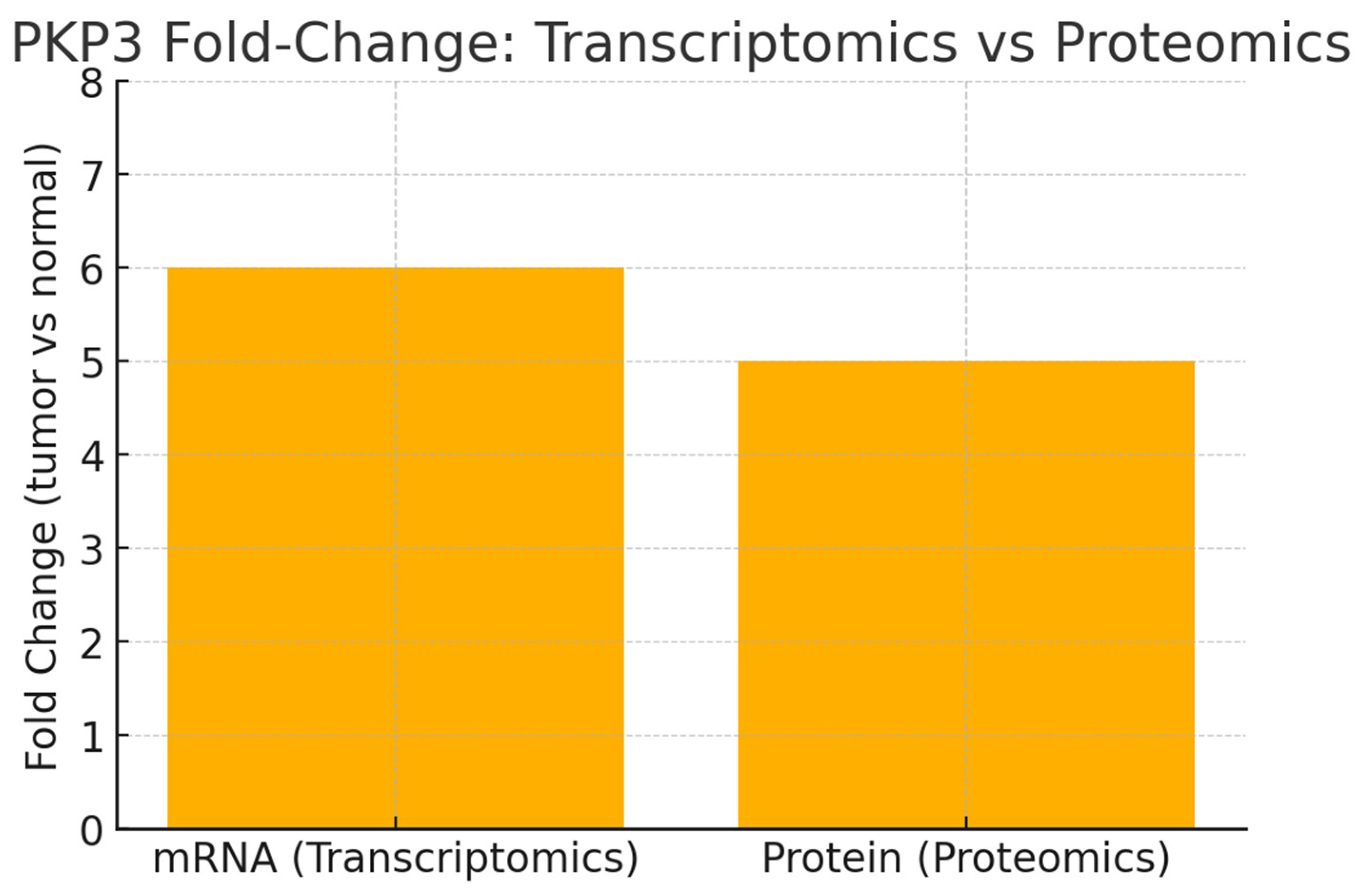

- Valladares-Ayerbes, M.; Díaz-Prado, S.; Reboredo, M.; Medina, V.; Lorenzo-Patiño, M.J.; Iglesias-Díaz, P.; Haz, M.; Pértega, S.; Santamarina, I.; Blanco, M.; et al. Evaluation of Plakophilin-3 mRNA as a Biomarker for Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells in Gastrointestinal Cancer Patients. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2010, 19, 1432–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Feng, Y.; Xie, N.; Yang, Y.; Yang, D. FERMT1 promotes cell migration and invasion in non-small cell lung cancer via regulating PKP3-mediated activation of p38 MAPK signaling. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H.; Yuan, D.; Bao, J.; Liu, F.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Han, G.; Huang, J.; Sheng, H.; Yu, H. Increased expression of plakophilin 3 is associated with poor prognosis in ovarian cancer. Medicine 2019, 98, e14608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Advanced Centre for Treatment Research & Education in Cancer | PLAKOPHILIN3 FUNCTIONS REQUIRED FOR THE INHIBITION OF TUMOR PROGRESSION AND METASTASIS. (n.d.). https://actrec.gov.

- Gao, L.; Li, X.; Guo, Q.; Nie, X.; Hao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhu, L.; Yan, L.; Lin, B. Identification of PKP 2/3 as potential biomarkers of ovarian cancer based on bioinformatics and experiments. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, Y.; Jiang, W.; Dong, S.; Li, W.; Tang, H.; Yi, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, H. Integrated transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics-based analysis uncover TAM2-associated glycolysis and pyruvate metabolic remodeling in pancreatic cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1170223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorovic´, V.; Koetsier, J.L.; Godsel, L.M.; Green, K.J. Plakophilin 3 mediates Rap1-dependent desmosome assembly and adherens junction maturation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 3749–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arreola-Aldape, C.A.; Moran-Guerrero, J.A.; Pons-Monnier, G.K.; Flores-Salcido, R.E.; Martinez-Ledesma, E.; Ruiz-Manriquez, L.M.; Razo-Alvarez, K.R.; Mares-Custodio, D.; Avalos-Montes, P.J.; Figueroa-Sanchez, J.A.; et al. A systematic review and functional in-silico analysis of genes and variants associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1598336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Mu, W.; Zheng, M.; Bao, X.; Li, H.; Luo, X.; Ren, J.; Zuo, Z. RMVar 2.0: an updated database of functional variants in RNA modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53, D275–D283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamisoglu, K.; Acevedo, A.; Almon, R.R.; Coyle, S.; Corbett, S.; Dubois, D.C.; Nguyen, T.T.; Jusko, W.J.; Androulakis, I.P. Understanding Physiology in the Continuum: Integration of Information from Multiple -Omics Levels. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandereyken, K.; Sifrim, A.; Thienpont, B.; Voet, T. Methods and applications for single-cell and spatial multi-omics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2023, 24, 494–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Filippo, M.; Pescini, D.; Galuzzi, B.G.; Bonanomi, M.; Gaglio, D.; Mangano, E.; Consolandi, C.; Alberghina, L.; Vanoni, M.; Damiani, C. INTEGRATE: Model-based multi-omics data integration to characterize multi-level metabolic regulation. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1009337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yizhak, K.; Benyamini, T.; Liebermeister, W.; Ruppin, E.; Shlomi, T. Integrating quantitative proteomics and metabolomics with a genome-scale metabolic network model. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, i255–i260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, M.; Snyder, M. Multi-Omics Profiling for Health. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2023, 22, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, M.; Asmis, R.; Hawkins, G.A.; Howard, T.D.; Cox, L.A. The Need for Multi-Omics Biomarker Signatures in Precision Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprulu, M.; Carrasco-Zanini, J.; Wheeler, E.; Lockhart, S.; Kerrison, N.D.; Wareham, N.J.; Pietzner, M.; Langenberg, C. Proteogenomic links to human metabolic diseases. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 516–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, E.; Lombardi, A.; De Lange, P.; Glinni, D.; Senese, R.; Cioffi, F.; Lanni, A.; Goglia, F.; Moreno, M. Studies of Complex Biological Systems with Applications to Molecular Medicine: The Need to Integrate Transcriptomic and Proteomic Approaches. BioMed Res. Int. 2010, 2011, 810242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, W. Protein–protein interaction network analysis of insecticide resistance molecular mechanism in Drosophila melanogaster. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2018, 100, e21523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhami, M.; Sadeghi, B.; Rezapour, A.; Haghdoost, A.A.; MotieGhader, H. Repurposing novel therapeutic candidate drugs for coronavirus disease-19 based on protein-protein interaction network analysis. BMC Biotechnol. 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A., ; Mukhtar, S. (2023). Protein–Protein interaction network exploration using Cytoscape. Methods in Molecular Biology, 419–427. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Tavirani, M.; Rezaei-Tavirani, S.; Mansouri, V.; Rostami-Nejad, M.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M. Protein-Protein Interaction Network Analysis for a Biomarker Panel Related to Human Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. 18, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

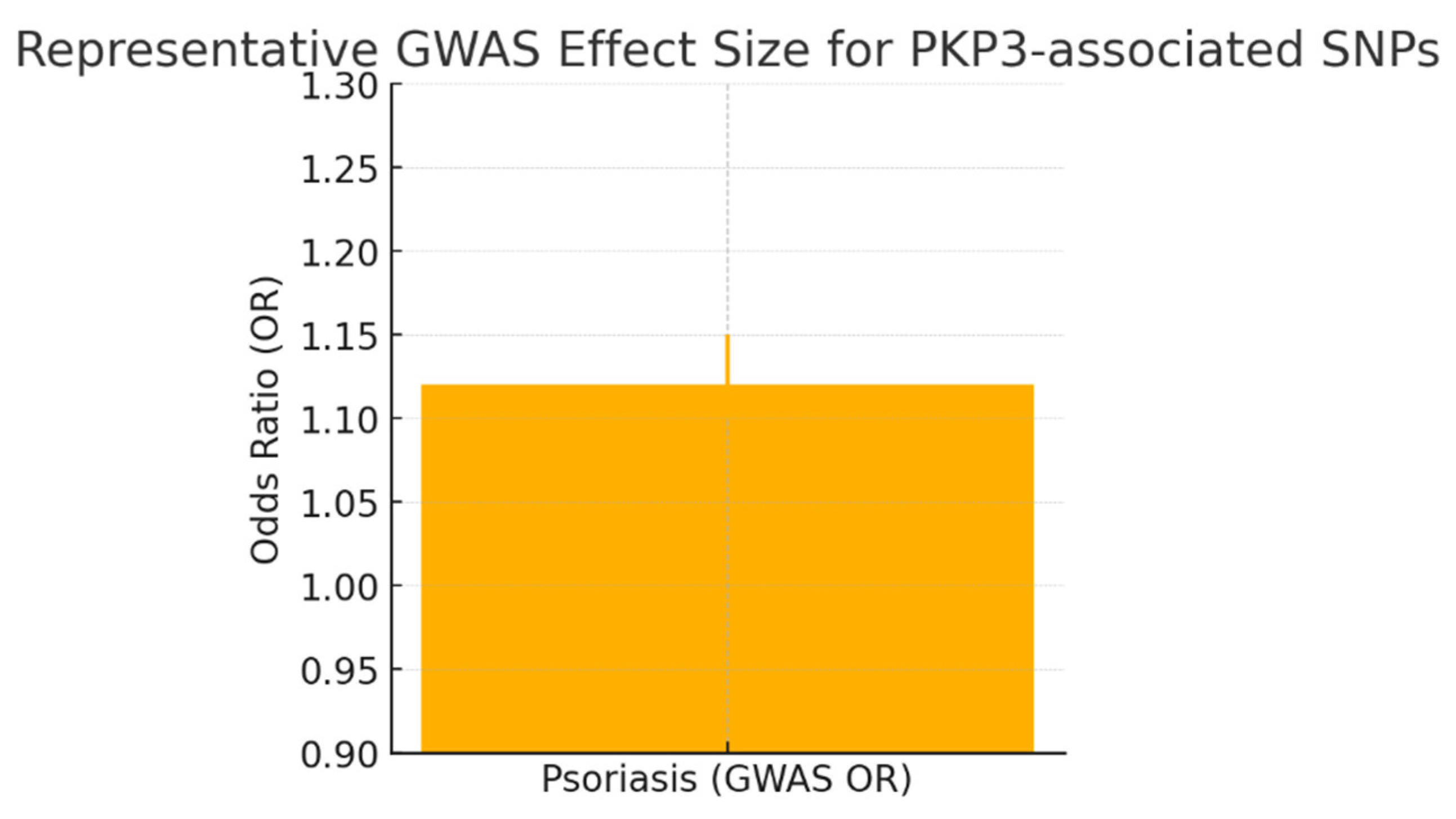

- Dand, N.; Stuart, P.E.; Bowes, J.; Ellinghaus, D.; Nititham, J.; Saklatvala, J.R.; Teder-Laving, M.; Thomas, L.F.; Traks, T.; Uebe, S.; et al. GWAS meta-analysis of psoriasis identifies new susceptibility alleles impacting disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinVar. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/ (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Sanches, P.H.G.; de Melo, N.C.; Porcari, A.M.; de Carvalho, L.M. Integrating Molecular Perspectives: Strategies for Comprehensive Multi-Omics Integrative Data Analysis and Machine Learning Applications in Transcriptomics, Proteomics, and Metabolomics. Biology 2024, 13, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maan, K.; Baghel, R.; Dhariwal, S.; Sharma, A.; Bakhshi, R.; Rana, P. Metabolomics and transcriptomics based multi-omics integration reveals radiation-induced altered pathway networking and underlying mechanism. npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 2023, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, A.; Salehi, H.; Bashir, S.; Tabassum, J.; Jamla, M.; Charagh, S.; Barmukh, R.; Mir, R.A.; Bhat, B.A.; Javed, M.A.; et al. Transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics interventions prompt crop improvement against metal(loid) toxicity. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, J.L.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Shen, L.; Long, Q. Deep learning-based approaches for multi-omics data integration and analysis. BioData Min. 2024, 17, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide to Multi-Omics Association Analysis in Metabolomics and Transcriptomics. (n.d.). MetwareBio. https://www.metwarebio.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).