Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

07 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

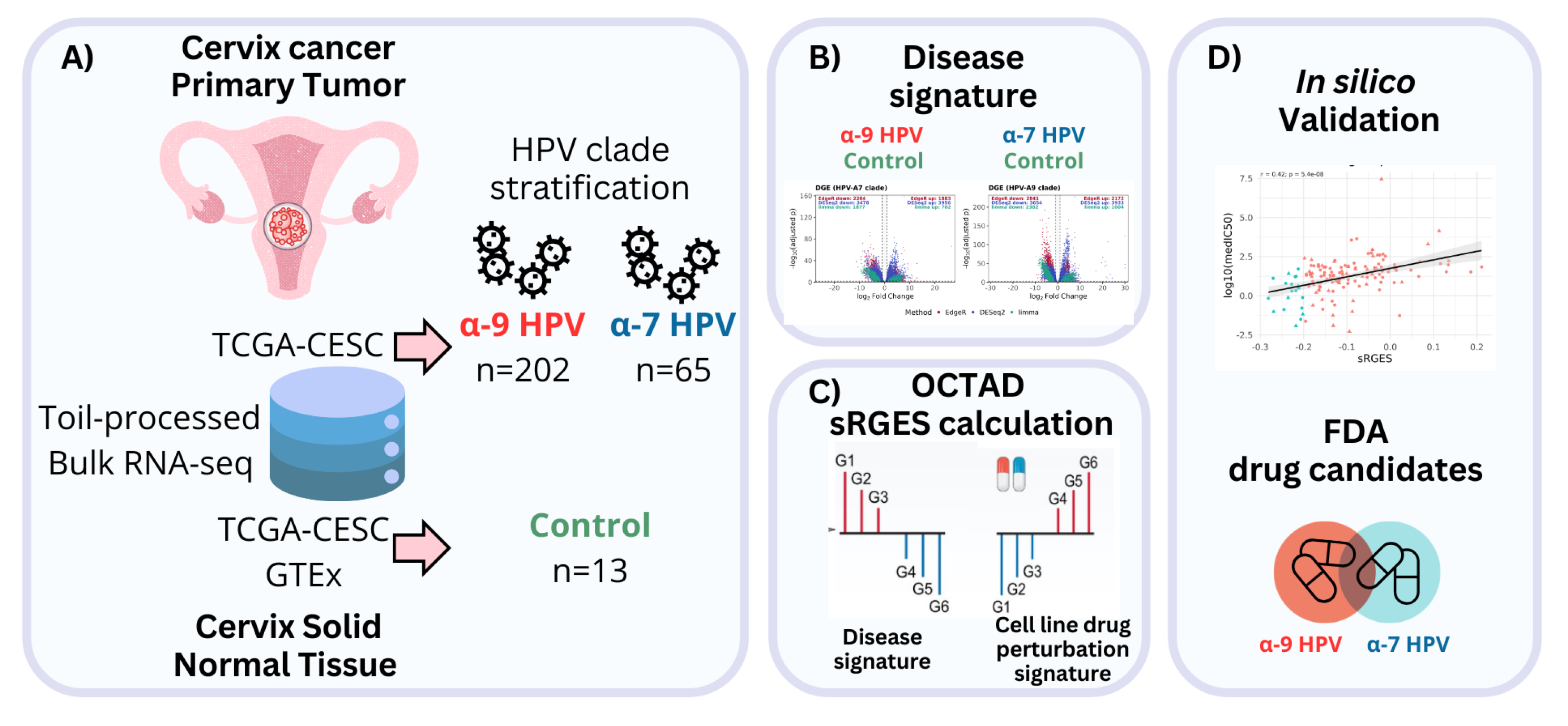

2. Results

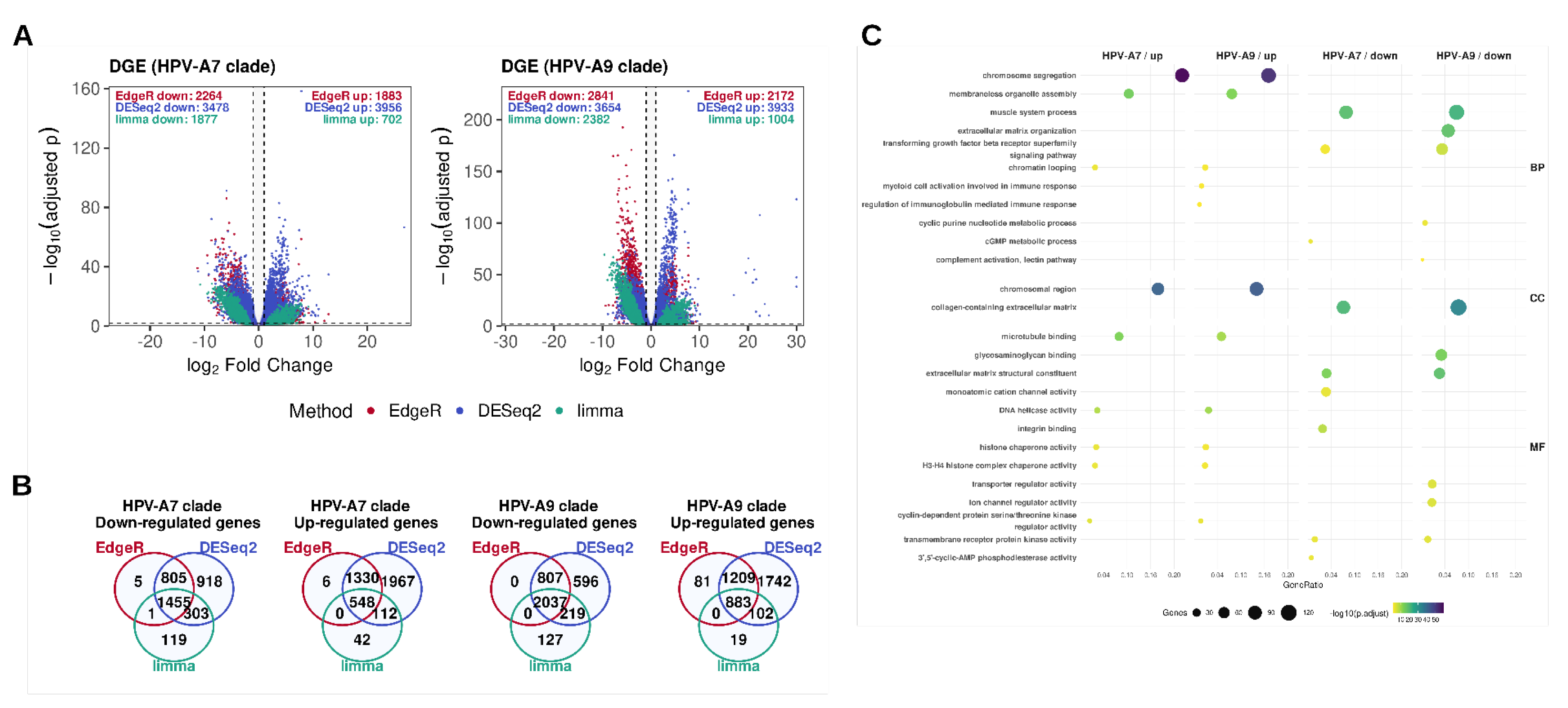

2.1. Differential Expression Analysis Across HPV Clades Supports Both Shared and Clade-Specific Transcriptional Programs

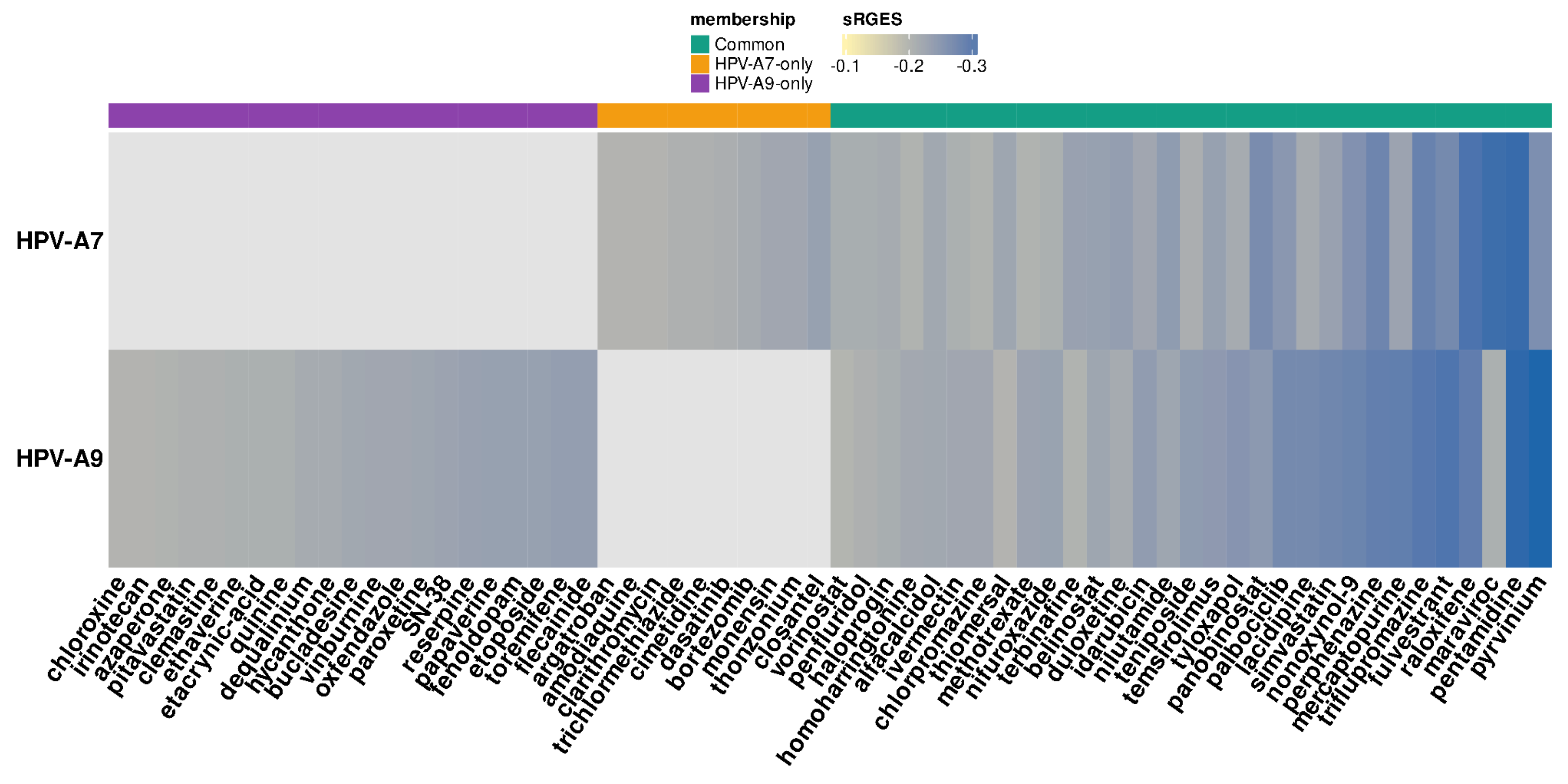

2.2. Drug Candidates for Repositioning in HPV Clade-Specific Cervical Cancer

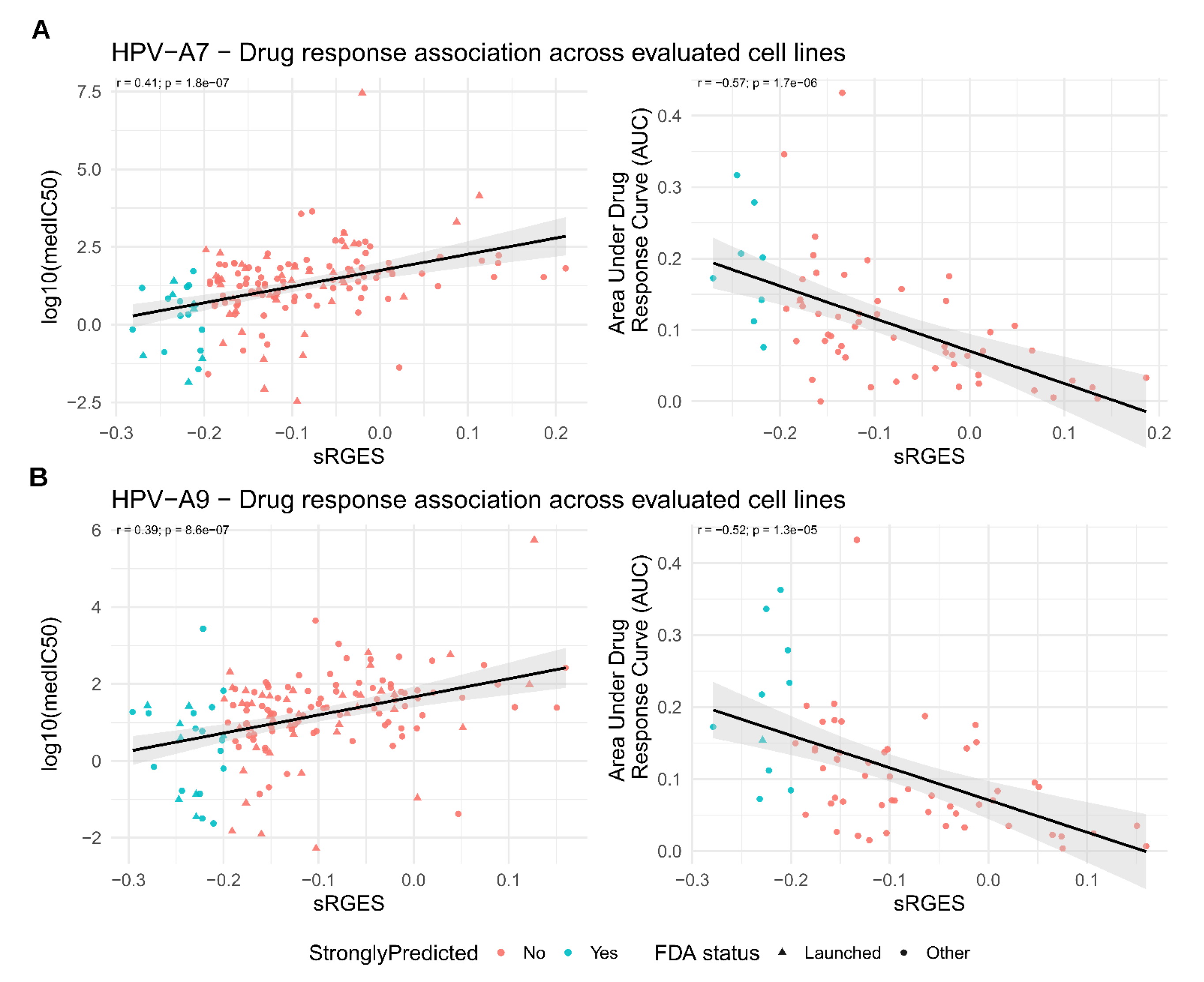

2.3. Validation of Predicted Drug Response

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data and Cohort Definition

4.2. Differential Expression Analysis

4.3. Over-Representation Analysis

4.4. sRGES Calculation

4.5. Drug Set Enrichment Analysis

4.6. Validation of Predicted Drug Response

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Brisson, M.; Kim, J.J.; Canfell, K.; Drolet, M.; Gingras, G.; Burger, E.A.; Martin, D.; Simms, K.T.; Bénard, É.; Boily, M.-C.; et al. Impact of HPV Vaccination and Cervical Screening on Cervical Cancer Elimination: A Comparative Modelling Analysis in 78 Low-Income and Lower-Middle-Income Countries. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2020, 395, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.; Aimagambetova, G.; Ukybassova, T.; Kongrtay, K.; Azizan, A. Human Papillomavirus Infection and Cervical Cancer: Epidemiology, Screening, and Vaccination-Review of Current Perspectives. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 3257939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo-Ruiz, V.; Gutiérrez-Xicotencatl, L.; Medina-Contreras, O.; Lizano, M. Molecular Aspects of Cervical Cancer: A Pathogenesis Update. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Oropeza, R.; Piña-Sánchez, P. Epigenetic and Transcriptomic Regulation Landscape in HPV+ Cancers: Biological and Clinical Implications. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 886613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Zhou, J.; Wang, F.; Shi, H.; Li, Y.; Li, B. HPV-16 E6/E7 Promotes Cell Migration and Invasion in Cervical Cancer via Regulating Cadherin Switch in Vitro and in Vivo. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 292, 1345–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilting, S.M.; Steenbergen, R.D.M. Molecular Events Leading to HPV-Induced High Grade Neoplasia. Papillomavirus Res. 2016, 2, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Bello, J.O.; Carrillo-García, A.; Lizano, M. Epidemiology and Molecular Biology of HPV Variants in Cervical Cancer: The State of the Art in Mexico. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rader, J.S.; Tsaih, S.; Fullin, D.; Murray, M.W.; Iden, M.; Zimmermann, M.T.; Flister, M.J. Genetic Variations in Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer Outcomes. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 2206–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, A.; Porter, V.L.; Zong, Z.; Bowlby, R.; Titmuss, E.; Namirembe, C.; Griner, N.B.; Petrello, H.; Bowen, J.; Chan, S.K.; et al. Analysis of Ugandan Cervical Carcinomas Identifies Human Papillomavirus Clade–Specific Epigenome and Transcriptome Landscapes. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 800–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobeyama, H.; Sumi, T.; Misugi, F.; Okamoto, E.; Hattori, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Yasui, T.; Honda, K.-I.; Iwai, K.; Ishiko, O. Association of HPV Infection with Prognosis after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Advanced Uterine Cervical Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2004, 14, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdousi, J.; Nagai, Y.; Asato, T.; Hirakawa, M.; Inamine, M.; Kudaka, W.; Kariya, K.-I.; Aoki, Y. Impact of Human Papillomavirus Genotype on Response to Treatment and Survival in Patients Receiving Radiotherapy for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Cervix. Exp. Ther. Med. 2010, 1, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-C.; Lai, C.-H.; Huang, H.-J.; Chao, A.; Chang, C.-J.; Chang, T.-C.; Chou, H.-H.; Hong, J.-H. Clinical Effect of Human Papillomavirus Genotypes in Patients with Cervical Cancer Undergoing Primary Radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 78, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Control: A Guide to Essential Practice; World Health Organization, World Health Organization, Eds. ; Second edition.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2014; ISBN 978-92-4-154895-3. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wu, X.; Cheng, X. Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment of Metastatic Cervical Cancer. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 27, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.; Viveros-Carreño, D.; Hoegl, J.; Ávila, M.; Pareja, R. Human Papillomavirus-Independent Cervical Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burmeister, C.A.; Khan, S.F.; Schäfer, G.; Mbatani, N.; Adams, T.; Moodley, J.; Prince, S. Cervical Cancer Therapies: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Tumour Virus Res. 2022, 13, 200238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Luo, H.; Zhang, W.; Shen, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhu, X. Molecular Mechanisms of Cisplatin Resistance in Cervical Cancer. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2016, 10, 1885–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Wang, M.; Li, X.; Yin, S.; Wang, B. An Overview of Novel Agents for Cervical Cancer Treatment by Inducing Apoptosis: Emerging Drugs Ongoing Clinical Trials and Preclinical Studies. Front. Med. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Xie, N.; Nice, E.C.; Zhang, T.; Cui, Y.; Huang, C. Overcoming Cancer Therapeutic Bottleneck by Drug Repurposing. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langedijk, J.; Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K.; Slijkerman, D.S.; Schutjens, M.-H.D.B. Drug Repositioning and Repurposing: Terminology and Definitions in Literature. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weth, F.R.; Hoggarth, G.B.; Weth, A.F.; Paterson, E.; White, M.P.J.; Tan, S.T.; Peng, L.; Gray, C. Unlocking Hidden Potential: Advancements, Approaches, and Obstacles in Repurposing Drugs for Cancer Therapy. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 130, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Kim, M.; Lee, S.; Jung, W.; Kim, B. Therapeutic Potential of Natural Products in Treatment of Cervical Cancer: A Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capistrano I, R.; Paul, S.; Boere, I.; Pantziarka, P.; Chopra, S.; Nout, R.A.; Bouche, G. Drug Repurposing as a Potential Source of Innovative Therapies in Cervical Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer Off. J. Int. Gynecol. Cancer Soc. 2022, 32, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Anda-Jáuregui, G.; Guo, K.; McGregor, B.A.; Hur, J. Exploration of the Anti-Inflammatory Drug Space Through Network Pharmacology: Applications for Drug Repurposing. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Anda-Jáuregui, G.; Guo, K.; Hur, J. Network-Based Assessment of Adverse Drug Reaction Risk in Polypharmacy Using High-Throughput Screening Data. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coria-Rodríguez, H.; Ochoa, S.; de Anda-Jáuregui, G.; Hernández-Lemus, E. Drug Repurposing for Basal Breast Cancer Subpopulations Using Modular Network Signatures. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2023, 105, 107902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, J.; Crawford, E.D.; Peck, D.; Modell, J.W.; Blat, I.C.; Wrobel, M.J.; Lerner, J.; Brunet, J.-P.; Subramanian, A.; Ross, K.N.; et al. The Connectivity Map: Using Gene-Expression Signatures to Connect Small Molecules, Genes, and Disease. Science 2006, 313, 1929–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Narayan, R.; Corsello, S.M.; Peck, D.D.; Natoli, T.E.; Lu, X.; Gould, J.; Davis, J.F.; Tubelli, A.A.; Asiedu, J.K.; et al. A Next Generation Connectivity Map: L1000 Platform and the First 1,000,000 Profiles. Cell 2017, 171, 1437–1452.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Pedroza, R.A.; Espinal-Enríquez, J.; Hernández-Lemus, E. Pathway-Based Drug Repositioning for Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Lemus, E.; Martínez-García, M. Pathway-Based Drug-Repurposing Schemes in Cancer: The Role of Translational Bioinformatics. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Ma, L.; Paik, H.; Sirota, M.; Wei, W.; Chua, M.-S.; So, S.; Butte, A.J. Reversal of Cancer Gene Expression Correlates with Drug Efficacy and Reveals Therapeutic Targets. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 16022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessetto, Z.Y.; Chen, B.; Alturkmani, H.; Hyter, S.; Flynn, C.A.; Baltezor, M.; Ma, Y.; Rosenthal, H.G.; Neville, K.A.; Weir, S.J.; et al. In Silico and in Vitro Drug Screening Identifies New Therapeutic Approaches for Ewing Sarcoma. Oncotarget 2016, 8, 4079–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahchan, N.S.; Dudley, J.T.; Mazur, P.K.; Flores, N.; Yang, D.; Palmerton, A.; Zmoos, A.-F.; Vaka, D.; Tran, K.Q.T.; Zhou, M.; et al. A Drug Repositioning Approach Identifies Tricyclic Antidepressants as Inhibitors of Small Cell Lung Cancer and Other Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 1364–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, H.; Chen, M.; Wang, S.; Qian, R.; Zhang, L.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Qin, W.; et al. A Survey of Optimal Strategy for Signature-Based Drug Repositioning and an Application to Liver Cancer. eLife 2022, 11, e71880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, B.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Newbury, P.; Chekalin, E.; Xing, J.; Liu, K.; Wen, A.; Chow, C.; Chen, B. OCTAD: An Open Workspace for Virtually Screening Therapeutics Targeting Precise Cancer Patient Groups Using Gene Expression Features. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 728–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burk, R.D.; Chen, Z.; Saller, C.; Tarvin, K.; Carvalho, A.L.; Scapulatempo-Neto, C.; Silveira, H.C.; Fregnani, J.H.; Creighton, C.J.; Anderson, M.L.; et al. Integrated Genomic and Molecular Characterization of Cervical Cancer. Nature 2017, 543, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inkman, M.J.; Jayachandran, K.; Ellis, T.M.; Ruiz, F.; McLellan, M.D.; Miller, C.A.; Wu, Y.; Ojesina, A.I.; Schwarz, J.K.; Zhang, J. HPV-EM: An Accurate HPV Detection and Genotyping EM Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Straub, E.; Stubenrauch, F.; Iftner, T.; Schindler, M.; Simon, C. An Enhanced Triple Fluorescence Flow-Cytometry-Based Assay Shows Differential Activation of the Notch Signaling Pathway by Human Papillomavirus E6 Proteins. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Majerciak, V.; Zheng, Z.-M. HPV16 and HPV18 Genome Structure, Expression, and Post-Transcriptional Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Newbury, P.; Ishi, Y.; Chekalin, E.; Zeng, B.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Wen, A.; Paithankar, S.; Sasaki, T.; Suri, A.; et al. Reversal of Cancer Gene Expression Identifies Repurposed Drugs for Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2022, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrefai, E.A.; Alhejaili, R.T.; Haddad, S.A. Human Papillomavirus and Its Association With Cervical Cancer: A Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e57432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Qiu, K.; Ren, J.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, P. Roles of Human Papillomavirus in Cancers: Oncogenic Mechanisms and Clinical Use. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, V.L.; Ng, M.; O’Neill, K.; MacLennan, S.; Corbett, R.D.; Culibrk, L.; Hamadeh, Z.; Iden, M.; Schmidt, R.; Tsaih, S.-W.; et al. Rearrangements of Viral and Human Genomes at Human Papillomavirus Integration Events and Their Allele-Specific Impacts on Cancer Genome Regulation. Genome Res. 2025, 35, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, A.A.; Warburton, A. The Role of Integration in Oncogenic Progression of HPV-Associated Cancers. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løvestad, A.H.; Repesa, A.; Costanzi, J.-M.; Lagström, S.; Christiansen, I.K.; Rounge, T.B.; Ambur, O.H. Differences in Integration Frequencies and APOBEC3 Profiles of Five High-Risk HPV Types Adheres to Phylogeny. Tumour Virus Res. 2022, 14, 200247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, A.; Reddin, I.; Henderson, S.; Dong, C.; Kirkwood, N.; Jeyakumar, M.; Rodriguez, D.R.; Martinez, N.G.; McDermott, J.; Su, X.; et al. Integrated Analysis of Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cohorts from Three Continents Reveals Conserved Subtypes of Prognostic Significance. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, S.; Luo, J.; Ying, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, P.; Wang, X. Subtyping of Human Papillomavirus-Positive Cervical Cancers Based on the Expression Profiles of 50 Genes. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 801639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, M.; Yu, J.; Yu, S.; Ruan, Z. Histone Modifications in Cervical Cancer: Epigenetic Mechanisms, Functions and Clinical Implications (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2025, 54, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejligbjerg, M.; Grauslund, M.; Litman, T.; Collins, L.; Qian, X.; Jeffers, M.; Lichenstein, H.; Jensen, P.B.; Sehested, M. Differential Effects of Class I Isoform Histone Deacetylase Depletion and Enzymatic Inhibition by Belinostat or Valproic Acid in HeLa Cells. Mol. Cancer 2008, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, N.S.; Moore, D.W.; Broker, T.R.; Chow, L.T. Vorinostat, a Pan-HDAC Inhibitor, Abrogates Productive HPV-18 DNA Amplification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, E11138–E11147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borcoman, E.; Cabarrou, B.; Francisco, M.; Bigot, F.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Vansteene, D.; Legrand, F.; Halladjian, M.; Dupain, C.; Le Saux, O.; et al. Efficacy of Pembrolizumab and Vorinostat Combination in Patients with Recurrent and/or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinomas: A Phase 2 Basket Trial. Nat. Cancer 2025, 6, 1370–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.-H.; Lambert, P.F. Prevention and Treatment of Cervical Cancer in Mice Using Estrogen Receptor Antagonists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 19467–19472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.-Q.; Wang, X.-H.; Tang, L.-P.; Chen, X.-W.; Lou, G. Raloxifene Suppress Proliferation-Promoting Function of Estrogen in CaSKi Cervical Cells. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 5571–5575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buccioli, G.; Testa, C.; Jacchetti, E.; Pinoli, P.; Carelli, S.; Ceri, S.; Raimondi, M.T. The Molecular Basis of the Anticancer Effect of Statins. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Xu, J.; Ma, L. Simvastatin Enhances Chemotherapy in Cervical Cancer via Inhibition of Multiple Prenylation-Dependent GTPases-Regulated Pathways. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 34, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacıseyitoğlu, A.Ö.; Doğan, T.Ç.; Dilsiz, S.A.; Canpınar, H.; Eken, A.; Bucurgat, Ü.Ü. Pitavastatin Induces Caspase-Mediated Apoptotic Death through Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage in Combined with Cisplatin in Human Cervical Cancer Cell Line. J. Appl. Toxicol. JAT 2024, 44, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Wu, J.-X.; Yang, S.-F.; Wu, Y.-C.; Hsiao, Y.-H. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Anticancer Properties of Pitavastatin against Cervical Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Xu, L.; Mo, G.; Duan, G.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Chen, H. Targeting the eIF4E/β-Catenin Axis Sensitizes Cervical Carcinoma Squamous Cells to Chemotherapy. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Ponzini, F.M.; Schultz, C.W.; Leiby, B.E.; Cannaday, S.; Yeo, T.; Posey, J.; Bowne, W.B.; Yeo, C.; Brody, J.R.; Lavu, H.; et al. Repurposing the FDA-Approved Anthelmintic Pyrvinium Pamoate for Pancreatic Cancer Treatment: Study Protocol for a Phase I Clinical Trial in Early-Stage Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e073839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.-Y.; Xia, B.; Liu, H.-C.; Xu, Y.-Q.; Huang, C.-J.; Gao, J.-M.; Dong, Q.-X.; Li, C.-Q. Closantel Suppresses Angiogenesis and Cancer Growth in Zebrafish Models. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2016, 14, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Fang, L.; Wang, R.; Zhang, X. Inhibition of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling by Monensin in Cervical Cancer. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Off. J. Korean Physiol. Soc. Korean Soc. Pharmacol. 2024, 28, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, Y. Long Non-Coding RNA MEG3 Inhibits Cervical Cancer Cell Growth by Promoting Degradation of P-STAT3 Protein via Ubiquitination. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qabbus, M.B.; Hunt, K.S.; Dynka, J.; Woodworth, C.D.; Sur, S.; Samways, D.S.K. Ivermectin-Induced Cell Death of Cervical Cancer Cells in Vitro a Consequence of Precipitate Formation in Culture Media. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2022, 449, 116073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiyama, T.; Yakushiji, M.; Noda, K.; Ikeda, M.; Kudoh, R.; Yajima, A.; Tomoda, Y.; Terashima, Y.; Takeuchi, S.; Hiura, M.; et al. Phase II Study of Irinotecan and Cisplatin as First-Line Chemotherapy in Advanced or Recurrent Cervical Cancer. Oncology 2000, 58, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabuchi, S.; Yokoi, E.; Shimura, K.; Komura, N.; Matsumoto, Y.; Sawada, K.; Isobe, A.; Tsutsui, T.; Kitada, F.; Kimura, T. A Phase II Study of Irinotecan Combined with S-1 in Patients with Advanced or Recurrent Cervical Cancer Previously Treated with Platinum Based Chemotherapy. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2019, 29, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, E.; Hoskins, P.J.; Pike, J.A.; Swenerton, K.D. Cisplatin/Etoposide Chemotherapy for Recurrent or Primarily Advanced Cervical Carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 1997, 64, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Wada-Hiraike, O.; Seiki, T.; Tanikawa, M.; Hiraike, H.; Sone, K.; Nagasaka, K.; Oda, K.; Kawana, K.; et al. Sequential Effects of the Proteasome Inhibitor Bortezomib and Chemotherapeutic Agents in Uterine Cervical Cancer Cell Lines. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 29, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, P.V.; Wouters, A.; Dirix, L.; Rolfo, C. Abstract 2317: Palbociclib Monotherapy Exhibits Potent Activity in Cervical Cancer Cell Lines. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Liao, X.; Yi, Y.; Xue, Y.; Yang, L.; Cheng, H.; Liu, P. The SGK3-Catalase Antioxidant Signaling Axis Drives Cervical Cancer Growth and Therapy Resistance. Redox Biol. 2023, 67, 102931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinker, A.V.; Ellard, S.; Welch, S.; Moens, F.; Allo, G.; Tsao, M.S.; Squire, J.; Tu, D.; Eisenhauer, E.A.; MacKay, H. Phase II Study of Temsirolimus (CCI-779) in Women with Recurrent, Unresectable, Locally Advanced or Metastatic Carcinoma of the Cervix. A Trial of the NCIC Clinical Trials Group (NCIC CTG IND 199). Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 130, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B. Atomic Force Microscopy Study on Chlorpromazine-Induced Morphological Changes of Living HeLa Cells In Vitro. Scanning 2009, 31, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekalin, E.; Paithankar, S.; Zeng, B.; Chen, B. Octad.Db: Open Cancer TherApeutic Discovery (OCTAD) Database.

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).