1. Preliminaries

This section gathers the basic notions used throughout the paper. Unless stated otherwise, all sets are taken to be finite.

1.1. Classical Structures, Hyperstructures, and n-Superhyperstructures

A

Classical Structure is an ordinary algebraic/relational system on a single carrier. A

Hyperstructure is obtained by promoting outcomes of operations to

sets (via the powerset). Iterating the powerset

n times gives rise to an

n-Superhyperstructure; see, e.g., [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Intuitively, the

n-fold powerset records

n layers of “grouping” or aggregation.

Definition 1

(Base set).

Abase set

is a nonempty collection S of atomic elements from which we form derived objects such as and the iterated powersets . Formally,

Definition 2

(Powerset).

[11] For any set S, thepowerset

is the set of all subsets of S:

Definition 3

(Iterated (nonempty) powersets).

(cf. [1,12,13]) Define and inductively

Thus , , and so on. If one wishes to exclude the empty set at each stage, write and set , .

Example 1

(Iterated (nonempty) powersets).— “Committees and Meeting Days”).

Let the employee set be

The first nonempty powerset consists of all nonemptycommittees

. Its cardinality is

The second nonempty powerset collects all nonemptymeeting-day plans

, i.e., nonempty families of committees. Its cardinality is

A concrete meeting-day plan is

interpreted as: on that day, the committee and the committee both convene.

Definition 4

(Classical Structure).

[14] A Classical Structure

is a pair

where is the carrier and each (for ) is a single–valued basic operation subject to the axioms appropriate to the intended theory. Typical instances include:

Sets and logics: a set with designated relations; propositional algebras .

Measure/probability: with .

Algebra:

groups, rings, and vector spaces with their standard operations [15,16,17,18].

Geometry/graphs/automata/games:

metric spaces, (di)graphs [19,20,21], finite automata, and strategic–form games.

Definition 5

(Hyperoperation).

(cf. [22,23,24,25]) Given a set S, ahyperoperation

is a set–valued binary map

Hence combining two elements can yield aset

of possible outcomes.

Definition 6

(Hyperstructure).

(cf. [1,13,26,27,28]) A Hyperstructure

is a pair in which the basic operation(s) act on (and return) subsets of a base set S. In contrast with classical structures, the output of an operation need not be a single element but may be a whole subset of S.

Example 2

(Hyperstructure — “Adding Measurements with Bounded Error”).

Let the base set be real lengths in centimeters, . Fix a worst-case device error bound cm (e.g., two instruments each with cm). Define the hyperoperation

This yields the hyperstructure , where combining two measured values returns the set

of all physically plausible sums given the error. Numerical instance:

If a third measurement (same error model) is combined, the set-wise extension gives

again a subset of S.

Definition 7

(SuperHyperOperations).

(cf. [1]) Let and let be as in Definition 3. An -SuperHyperOperation

is an m-ary map

where denotes either the full n-th powerset or its nonempty variant. Allowing permits set–valued outputs (and, for , nested families of sets).

Definition 8

(

n-Superhyperstructure).

(cf. [1,5,13]) For a base set S and , ann-Superhyperstructure

is any system

whose operations are defined on the n-fold powerset. The case recovers hyperstructures, while larger n encode multi-level aggregation.

Example 3

(

n-Superhyperstructure (

) — “Cross-Functional Project Plans”).

Let be atomic tasks. Then areteams

(task bundles), and are project plans

(families of teams). Define an operation by

Concrete data:

Then

which aggregates two plans into a new plan by pairwise union of teams—typical of multi-team synchronization. Thus is a 2-superhyperstructure.

Definition 9

(

-SuperHyperStructure).

(cf. [12,29]) Let and . An -SuperHyperStructure

(of arity s) consists of an operation

Specializations include ordinary s-ary operations when , hyperoperations when , and superhyperoperations when . Thus the -formalism uniformly bridges classical, hyper, and higher-level set-valued behaviors.

Example 4

(

-SuperHyperStructure (

) — “Shipping Bundle Alternatives”).

Let the item universe be . Elements of are carts

(chosen items), while elements of are bundle families

(alternative packagings made of item-bundles). Define

Here is the “single-box kit” alternative, and is the “two-box split” alternative. Take

Then

Thus realizes an -SuperHyperStructure that maps two carts to a family of feasible shipping-packaging plans.

1.2. Multi-Structure

A Multi-Structure replaces classical operations with maps from tuples to finite multisets, enabling multiple outputs per input tuple flexibly simultaneously.

Definition 10

(Finite Multiset).

(cf.[30,31,32,33]) Let H be a nonempty set. Afinite multiset

on H is a function

with finite support . We denote by the collection of all such finite multisets on H. Equivalently, an element of can be written as , where each and .

Definition 11

(MultiOperation).

Let H be a nonempty set and fix an integer . Amulti-operation

of arity m on H is a map

Thus, instead of producing a single element of H, a multi-operation assigns a finite multiset of elements of H.

Example 5

(MultiOperation — “Frequently bought together” in retail).

Let H be the set of store SKUs

Define a binary multi-operation that returns afinite multiset of recommended companion items

; multiplicities encode strength or quantity:

For instance, from the basket the system proposes , i.e. “suggest two jars of jam.” This is a concrete real-worldmulti-operation

because the output is a multiset of items in H.

Definition 12

(MultiStructure).

[34,35] A MultiStructure

is a pair

where H is a nonempty carrier set and indexes a family of multi-operations of various arities. No further axioms are imposed unless specified.

Example 6

(MultiStructure — unified retail recommendation rules of mixed arity).

Let the carrier be

Define two multi-operations (different arities) that act simultaneously on H:

Unary substitute rule:

Binary bundle rule:

Then

is aMultiStructure

: it fixes a nonempty carrier H and equips it with a family of multi-operations of various arities. A typical evaluation gives

showing how single-item substitutions and two-item bundle suggestions coexist in one practical system.

1.3. Iterative Multi-Structure

An Iterative Multi-Structure extends multiset operations across levels, combining multisets of multisets iteratively through

k hierarchical stages in layered aggregation [

34,

35].

Definition 13

(Iterative Multi-Structure of Order

k).

[34,35] Let H be a nonempty set and fix an integer . Define iteratively themultiset powersets

where denotes the collection of finite multisets on X (Definition 10). Let index a family of arities. AnIterative Multi-Structure of order

kis a tuple

where for each and each ,

Thus is an ordinary Multi-Structure operation on H, combines multisets of multisets, and so on, up to level k.

Example 7

(Iterative Multi-Structure — meal planning: ingredients → dishes → menus → weekly plan).

Fix depth . Let the carrier ofingredients

be

Recall , (finite multisets of ingredients), (finite multisets of dishes), and (finite multisets of menus).

Define levelwise multi-operations of arity 2:

Concretely, for put

For two dishes , let

i.e., a menu consisting of exactly those two dishes (multiplicity counts repeats). For two menus , let

i.e., a weekly plan made of two menus.

Concrete run.

Build a menu from these dishes:

Duplicate the menu to form a simple weekly plan:

Thus is anIterative Multi-Structure of order

: level 0 combines ingredients into dishes; level 1 combines dishes into menus; level 2 combines menus into a weekly plan, all via multiset aggregation.

1.4. MetaStructure (Structure of Structure)

A MetaStructure organizes structures as elements, providing uniform, isomorphism-invariant operations that construct new structures from existing ones via functorial recipes[

36,

37].

Notation 1.

Fix a single–sorted, finitary signature . A Σ-structure is

with carrier , operations and relations of the prescribed arities. Let be the class of all Σ-structures.

Definition 14

(MetaStructure over a fixed signature).

[36,37] A MetaStructure

over Σ is a pair

where , , and for each label ℓ of meta-arity the map is specifieduniformly

as follows: there exist constructors

such that for , the structure has

Each isisomorphism-invariant

: isomorphisms of inputs induce an isomorphism of outputs (naturality).

Remark 1

(Canonical meta-operations). All are isomorphism-invariant and uniform in Σ.

Product Π (arity 2): carrier ; operations act componentwise; relations are taken as products.

Disjoint union ⊎ (purely relational Σ): carrier ; relations are the tagged unions.

Reduct / Expansion(arity 1): forget or add symbols uniformly with prescribed interpretations.

Example 8

(MetaStructure — composing city transit networks).

Fix the single–sorted relational signature

A Σ-structure represents an urban transit network: H is the set of stops/stations, is the directed reachability relation (there is a scheduled connection from the first stop to the second), and marks airport terminals (intercity gateways).

Meta–operation (intercity linking).Define a binary meta–operation on the class of all such city networks by the uniform constructors:

Thus is the combined region–wide network that keeps all original city connections and adds intercity edges between every pair of airports. This construction is isomorphism–invariant: relabeling the inputs induces a relabeling of the output.

Concrete instance.Let with , , , and with , , . Then has

Interpretation: the regional network contains the original city routes and , and adds two intercity legs between the airports a and (both directions). This is a real–world MetaStructure: an operation onstructures

(city transit systems) that uniformly yields a newstructure

(a connected multimodal network) by functorial carrier/relations constructors.

An Iterated MetaStructure recursively applies MetaStructure construction, forming successive layers where structures of structures create deeper hierarchical meta-levels [

36,

37].

Definition 15

(Iterated MetaStructure of depth

t).

[36,37] AnIterated MetaStructure of depth

tover Σ is any MetaStructure of height t. When , welift

a height-s MetaStructure to height t by

and, for each , defining its lift

and similarly for relations .

Example 9

(Iterated MetaStructure — multi-tier transportation federation).

Fix the single–sorted relational signature

A Σ-structure models a transit fragment: H is a set of stops, is the directed connectivity relation (scheduled links), and are designated terminals (hubs).

Base level (0).Let be the class oflocal lines

(e.g. bus or metro lines). For a finite family , define the k-ary meta-operation by the uniform constructors

Thus fuses several lines into acity network

by tagged union plus bidirectional inter-line links between terminals.

Iterated lift.Let be the canonical “tagging” functor that sends to

and iterate it: applies r nested tags. Given , the lifted meta-operation on height t is defined by Definition 15:

Intuitively, the same “fuse-and-add-terminal-links” recipe is reused at every tier, while the tags record the tier of origin (city → country → region, etc.).

Concrete 3-tier instance ().Take three local lines

Tier 1 (cities).

Form two cities by

Here has carrier , keeps the intra-line edges , , and adds cross-links between terminals.

Tier 2 (country).

Fuse the two cities using the lifted operation

This produces a tagged disjoint union of the two city carriers and adds bidirectional inter-city edges between every terminal of and every terminal of .

Tier 3 (region).

Given several countries , form a region by

again adding links between country-level terminals. The result is a 3-level federation whose carrier is a multiply tagged union of stops, and whose relations are produced by thesame

uniform recipe at each tier. This realizes anIterated MetaStructure of depth

: the tier-independent constructor () is lifted systematically by to operate on structures-of-structures.

2. Review and Result: HyperMatrix and Superhypermatrix

Matrices are rectangular arrays indexed by rows and columns and taking values in a ground algebra (typically a field) [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. A

hypermatrix extends this idea by allowing each entry to be a

set of scalars rather than a single scalar [

45]; iterating the powerset construction then yields

superhypermatrix models that encode hierarchical uncertainty or multi–way choice (cf.[

46]).

Definition 16

(Matrix).

[47,48] Let K be a field (or skewfield) and let , . An matrix over

Kis a function

Addition and scalar multiplication are defined pointwise:

Definition 17

(Hypermatrix (set–valued matrix)).

A(set–valued) hypermatrix

over K is a map

where denotes the powerset of K. We extend linear operations entrywise via Minkowski lifting: for and ,

Thus, for hypermatrices and ,

The embedding , , identifies every classical matrix M with the hypermatrix given by .

Example 10

(Concrete

hypermatrix over

).

Let

where . Then

Definition 18

(

n–Superhypermatrix and recursive lifts).

For , let and . Ann–superhypermatrix

over K is a map

Define addition and scalar multiplication on by recursion: for and ,

Operations on n–superhypermatrices are then taken entrywise:

The canonical embedding is given by iterated singletons: and , so that a classical matrix M embeds as .

Example 11

(2–superhypermatrix: families of intervals).

Let each entry be a finiteset of intervals

, i.e. an element of :

Their sum uses the level–2 rule with interval Minkowski sum:

and similarly for the other entries. Scalar multiplication (e.g. ) doubles every interval in every set at level 2.

Notation 2.

Fix a (skew)field K, finite index sets and , and integers . Write and for . We use two canonical maps between levels:

(nested singleton lift), and the level–lowering maps

Definition 19

(Recursive

m–level lift of scalar operations).

Let be the field addition and multiplication, and for let be scalar multiplication. Define theirm–level set lifts

and recursively by

Definition 20

(

–lifted operations on level

n).

For and define

Thus weflatten

inputs from level n down to level m, perform the m–level Minkowski–type operation, andre–lift

to level n.

Definition 21

(

–Superhypermatrix).

A –superhypermatrix over

Kwith shape is a function

We define addition and scalar multiplication entrywise via Definition 20:

If J is finite, the –matrix product

of and is defined by

where denotes the iterated –sum (well–defined since J is finite).

Remark 2

(Selections and realizations). Aselectionof chooses, for every , an element of and then an element of K, yielding a classical matrix . Hence every –superhypermatrix encodes a (possibly large) family of ordinary matrices compatible with its entries.

Example 12

(A concrete

superhypermatrix).

Let , , , , and

where and is lifted to level 2 by a singleton brace. For addition, flatten to level 1 via (a union of the displayed sets of intervals), apply (interval Minkowski sum or setwise sum), then re–lift by . Scalar multiplication uses the same pattern with (interval scaling). Thus the –rules combine familiar interval arithmetic at level 1 with a level–2 wrapper that preserves hierarchical structure.

Example 13

((m,n)=(1,2)—Delivery time planning with route alternatives).

Fix (minutes). Each matrix entry is afinite set of intervals

(an element of ): each interval is a plausible time window for one route option, and a set of intervals collects theroute alternatives

available in that cell. Let rows becarriers

and columns belegs

. Consider

Let the leg–count vector (how many times each leg is taken) be

i.e., one unit of and one unit of . With , the matrix product

firstflattens to level 1

(sets of scalars), then performs the usual (level–1) Minkowski product/sum, and finally re–lifts to level 2.

Carrier .

Summing legs by :

Carrier .

For the total delivery time is either or minutes, depending on the route combination; for it is either or minutes. The –superhypermatrix keeps thefamily of feasible totals

rather than a single number.

Example 14

((m,n)=(1,2)—Procurement with uncertain quotes and quantities).

Let (USD). Rows arevendors

and columns areparts

. Each entry is aset of unit–price intervals

capturing promotional/market uncertainty:

Quantities (as a column) are exact integers, encoded at level 2 by singleton lifts:

The total spend per vendor is .

Vendor .Compute the two leg terms:

Sum by :

Thus Vendor A’s total is either the interval (if clears at ) or (if it clears at ).

Vendor .

Hence

The –superhypermatrix product returns afamily of plausible order totals

per vendor, explicitly propagating interval uncertainty (quotes) through multiplication by exact quantities and aggregation across parts.

Theorem 1

(Reduction to n–superhypermatrix). Fix and take . Then the operations , , and coincide with the standard level–n recursive lifts , , and from Definition 19. Consequently, every n–superhypermatrix (i.e. a map with entrywise level–n operations) is a special case of an –superhypermatrix (namely with ).

Proof. By Definition 20, when

we have

and

, hence

and similarly for ⊠ and ⊛. Therefore the

–entrywise operations reduce to the usual level–

n recursive Minkowski lifts, proving the claim. □

Theorem 2

(Well–definedness and closure). Let and . Then and (for any ) are again in . If J is finite and , then .

Proof. By construction for every . Definition 19 yields and . Applying returns elements of , proving entrywise closure for ⊞ and ⊛. For products, each and a finite iterated remains in . □

3. Review and Result: MultiMatrix and Iterative Multimatrix

A MultiMatrix is a matrix whose entries are finite multisets of scalars, with operations lifted entrywise via multiset Minkowski rules. An Iterative Multimatrix stacks MultiMatrices across levels, each entry a multiset-of-multisets, combining levelwise via lifted operations to model hierarchical aggregation.

Notation 3.

For a nonempty set H, a (finite) multiset on H is a function with finite support. The collection of all finite multisets on H is denoted . For and , write for the multiplicity of h. Define themultiset Minkowski lifts

of a binary map and of a unary map by

When H is a (skew)field K with + and ·, we abbreviate

Notation 4

(Indexing). Fix finite index sets and , and set .

Definition 22

(MultiMatrix over a field).

Let K be a (skew)field. AMultiMatrix

of shape over K is a function

i.e., each entry is a finite multiset of scalars. Define operations entrywise by

and, when J is finite, theMultiMatrix product

by

where ⊞ denotes finite iteration of ⊞.

Example 15

(MultiMatrix—weighted course grading (two components, two students)).

Let , , and write multisets with multiplicities as . Consider thescore MultiMatrix

where each entry lists all available scores for a student–component pair (e.g., multiple graders or attempts; the entry means two identical 93’s).

Let the (column)weight MultiMatrix

be

so component 1 carries weight and component 2 weight . Using the MultiMatrix product from Definition 22,

where ⊠ (resp. ⊞) is the multiset lift of scalar multiplication (resp. addition), we obtain amultiset of weighted totals

for each student.

Student 1.

Thus

Student 2.

hence

Therefore returns, for each student, thefinite multiset of all possible weighted course totals

, capturing grading variability (multiple graders/attempts) while remaining compatible with standard matrix weighting when entries are singletons.

Lemma 1

(Closure). For MultiMatrices of the same shape and , and are MultiMatrices of that shape. If and , then .

Proof. Each operation is built from on , which are closed by construction of the lifted multiplicities. Finite iteration of ⊞ remains in , establishing entrywise closure. □

Theorem 3

(MultiMatrix as a MultiStructure and reduction to classical matrices).

Let and define multi-operations on H by

Then the pair is aMultiStructure

(maps from tuples to finite multisets). Its pointwise (dimensional) lift along the axis set ,

has codomain exactly the set of MultiMatrices . Moreover, if we embed classical matrices by thesingleton lift

, then

Hence MultiMatrix generalizes classical matrix algebra (recovering it on singleton entries) and is representable via the MultiStructure lift .

Proof. The multi-operations are finite-multiset valued by definition, so is a MultiStructure. The dimensional lift (Definition of pointwise lift) evaluates at each index , producing an element of , i.e., a MultiMatrix. For a classical matrix M, has singleton entries. Because the lifted multiset operations reduce to classical operations on singletons, coincide with , respectively, yielding the displayed equalities and the reduction. □

Remark 3

(Selections viewpoint). A MultiMatrix induces a (finite) multiset of ordinary matrices: choose for each an element from (counted with product of multiplicities). Under this viewpoint, ⊕ (resp. ⊙) corresponds to the multiset sum of pairwise matrix sums (resp. products), consistent with Definition 22.

Definition 23

(Iterative MultiMatrix of depth

k).

Fix . AnIterative MultiMatrix (IMM) of depth

kand shape is a tuple

Operations actlevelwise and entrywise

using the lifted maps on :

and, for multiplication when J is finite,

Example 16

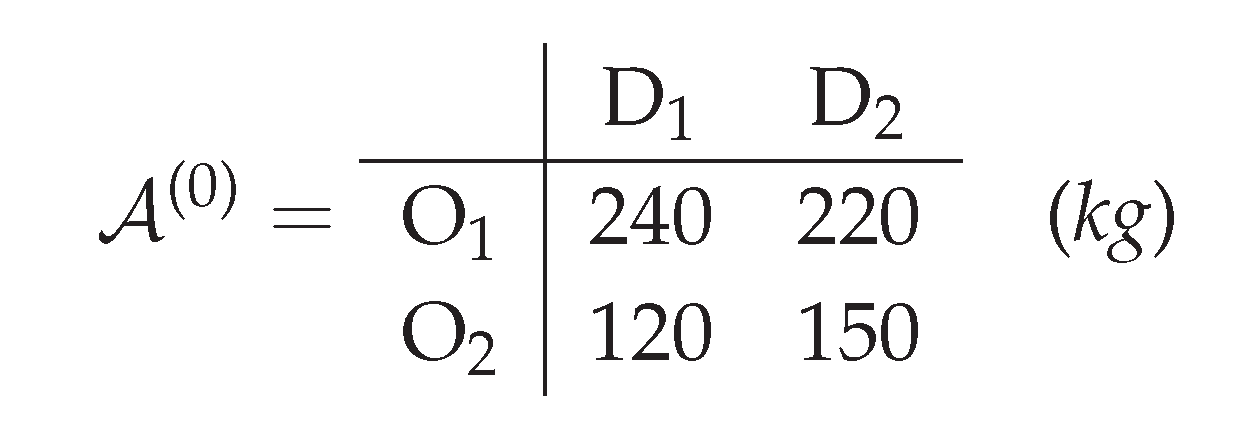

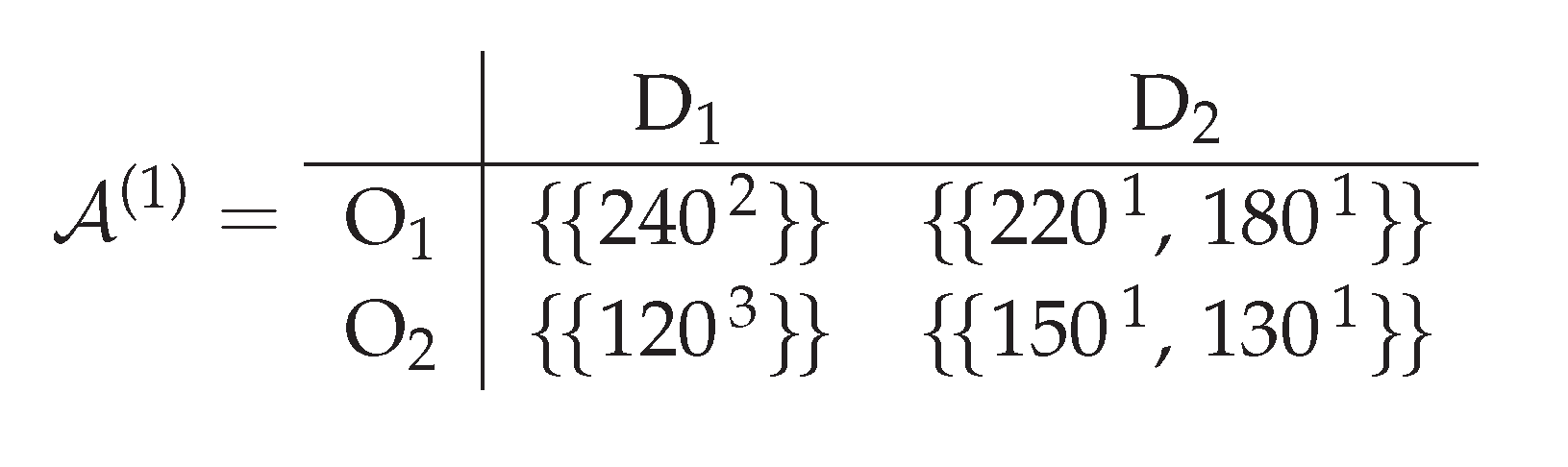

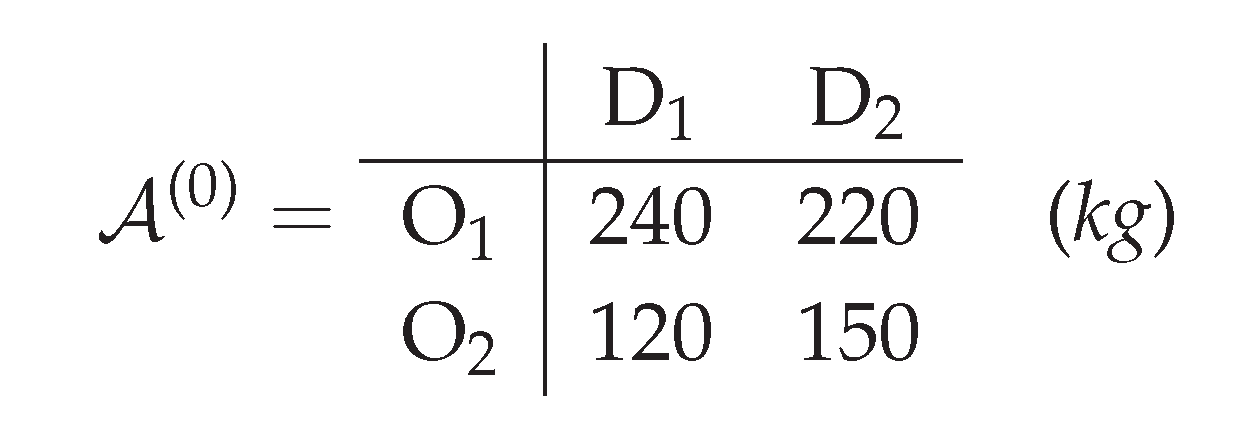

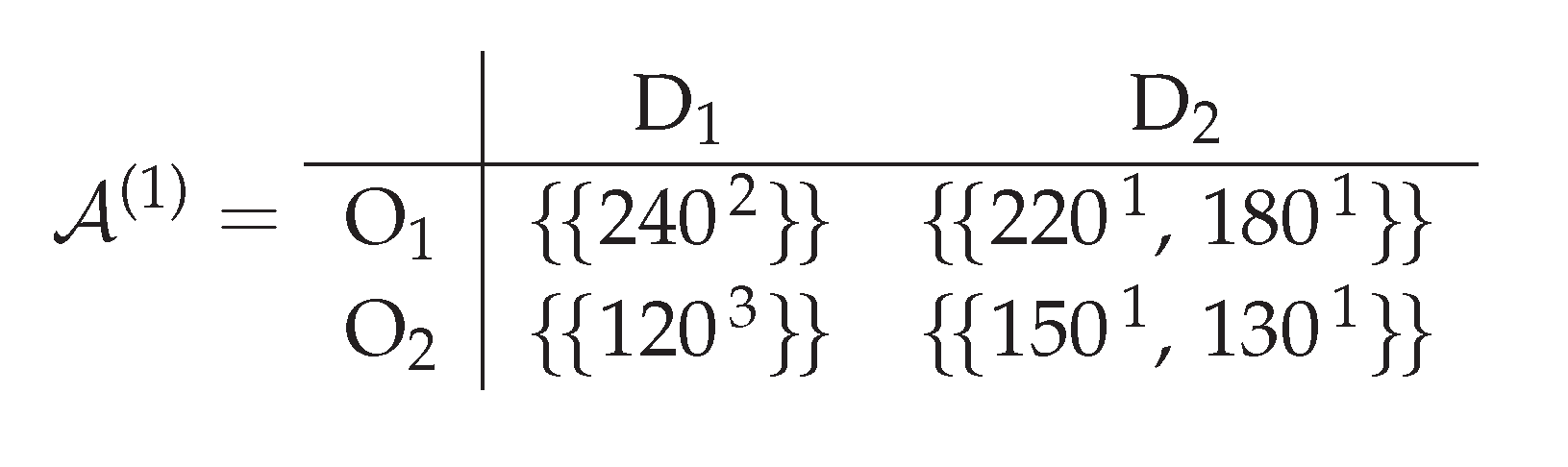

(Iterative MultiMatrix—warehouse packing across levels (items → orders → truckloads)). Let the ground field be (weights in kg). Take two orders and two delivery windows . We build anIterative MultiMatrixof depth , , where .

Level 0 (single pallet option per cell).

Each entry is one representative pallet weight for that (order, window).

Level 1 (multiset of pallets per cell).Here collects all pallets planned for that cell (multiplicity encodes how many identical pallets). We write multisets as .

Example: means two identical pallets of 240 kg.

Level 2 (multiset ofload plansper cell).Now ; each element of is itself a multiset of pallets (i.e., one admissible truckload composition for that cell). For readability, we list the four cells separately:

Interpretation: for there are two feasible truckload plans: either two pallets of 240 kg (plan A) or an alternative mix (two pallets of 180 kg plus one of 100 kg, plan B). Thus the level–2 entry is amultiset of admissible pallet-multisets.

How levelwise operations act.Given another IMM (e.g., a second warehouse), the sum adds scalar weights cellwise; performs the multiset lift of addition on pallet multisets; and combines load plans by the lifted rule on (Definition 23). This preserves the three-tier meaning: single pallets → pallet collections → sets of admissible load plans.

Lemma 2

(Closure per level). For each r, the lifted maps and send to itself, hence the IMM operations are well defined.

Proof. Identical to Lemma 1, applied in the universe . □

Theorem 4

(Iterative MultiMatrix as an Iterative MultiStructure).

For each , set and define levelwise multi-operations

Then

is anIterative MultiStructure

in the sense of level-indexed multi-operations. Moreover, the dimensional lift of along , acting pointwise at each level r, yields exactly the IMM space of Definition 23.

Proof. By construction, each maps m-tuples in to an element of , so the tuple forms an Iterative MultiStructure. Lifting along X replaces elements by X-indexed arrays and applies the same operations entrywise, which is precisely the IMM definition. □

Theorem 5

(Reductions: IMM ⇒ MultiMatrix ⇒ Matrix).

For , an IMM is a single matrix with entries in , with operations from Definition 22; hence IMM generalizes MultiMatrix.

For , an IMM is a classical matrix with entries in , and the lifted operations reduce to standard matrix algebra; hence MultiMatrix generalizes classical matrices via the singleton embedding.

Proof. (1) Immediate from the definitions with .

(2) When , the lifts coincide with on K, and with scalar multiplication, so we recover ordinary matrix operations. The singleton embedding argument is as in Theorem 3. □

4. Review and Result: MetaMatrix and Iterated MetaMatrix

MetaMatrix is a matrix whose entries are matrices; operations act uniformly by lifting row–column arithmetic to block-level structural composition rules. Iterated MetaMatrix stacks MetaMatrices across levels, forming matrices of matrices of matrices, with operations defined recursively and naturally across depths.

Definition 24

(Block profile and admissibility).

Let and be finite index sets. Ablock profile

on consists of two dimension vectors

We say that two profiles and aremultiplication–compatible

if their shared inner dimension vector is identical on both), where and .

Definition 25

(MetaMatrix (matrix of matrices)).

Given a block profile , aMetaMatrix over

Kwith that profile is a function

If we defineblockwise addition

andscalar multiplication

entrywise:

If and are multiplication–compatible, theMetaMatrix product

is

Example 17

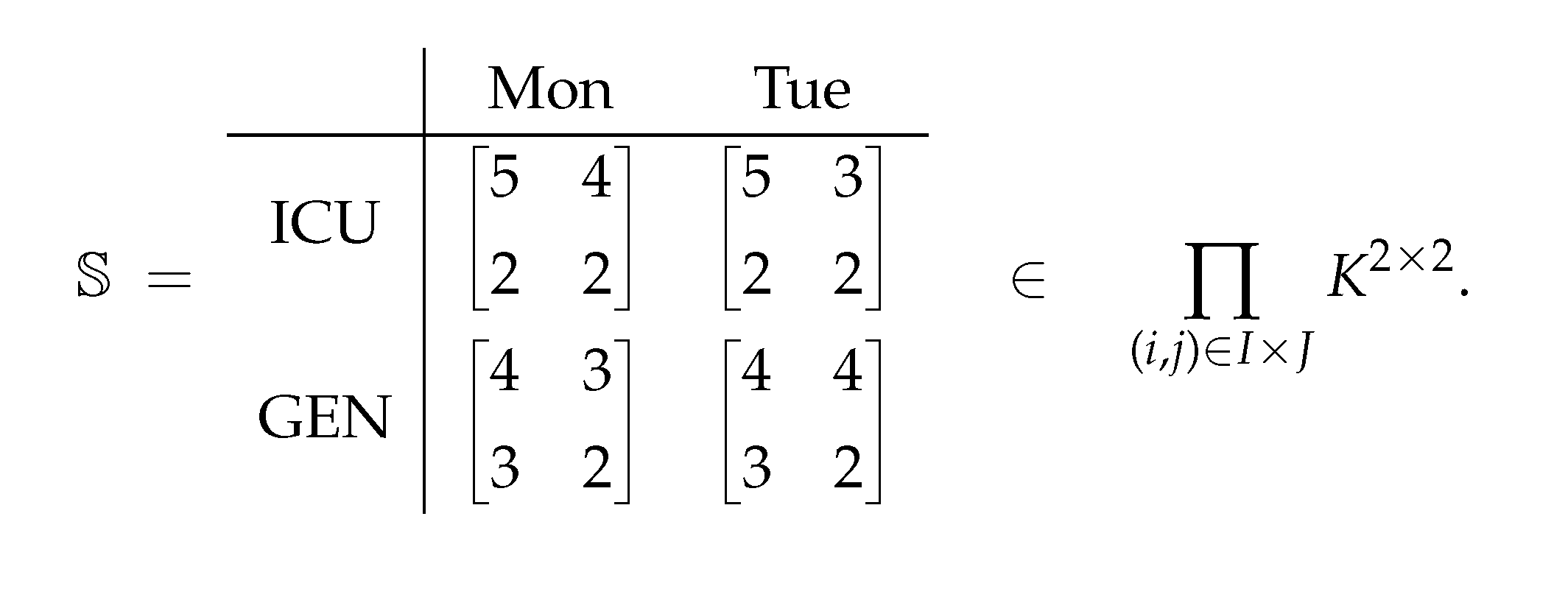

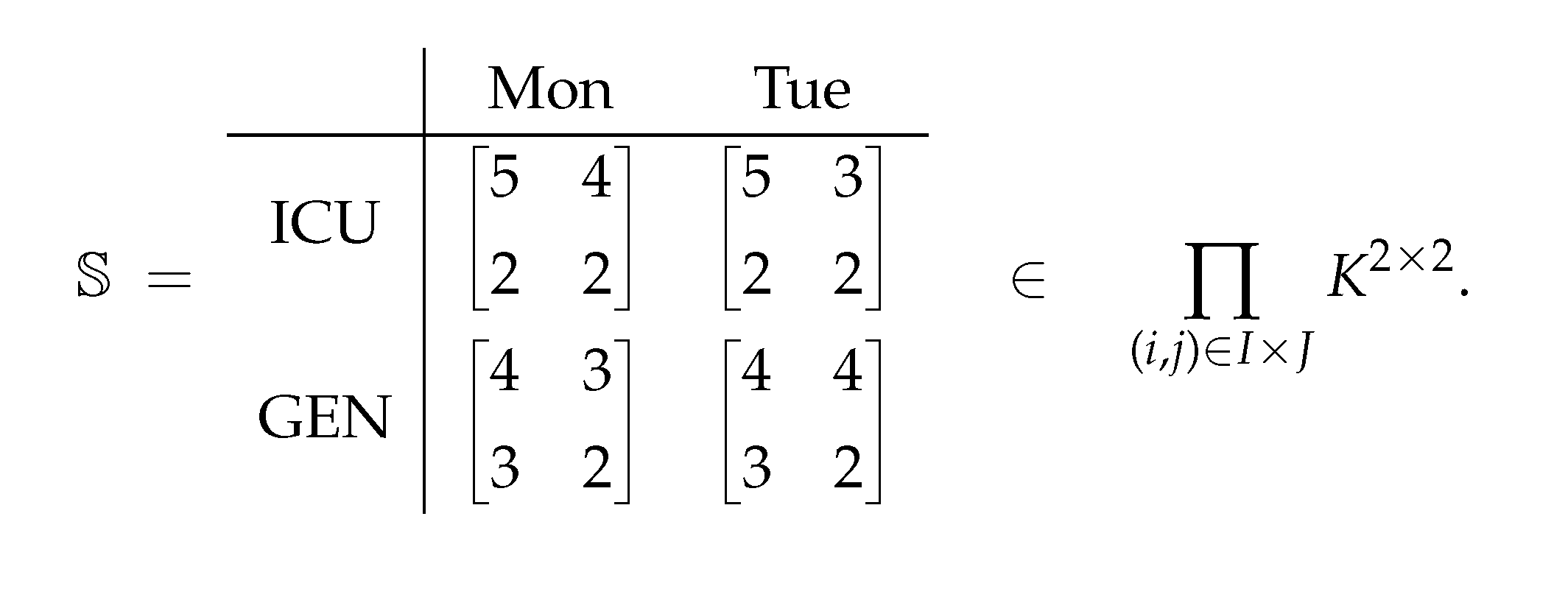

(MetaMatrix — hospital staffing (roles × shifts within wards × days)). Fix the ground field (headcounts). Let rows indexwards and columns indexdays. Each block is a matrix whose rows are (roles) and whose columns are (shifts). Thus the block profile is with , .

Define the MetaMatrix by

Its flattening is the block–assembled matrix

(rows ordered as ICU: RN,ICU:LPN,GEN:RN,GEN:LPN).

Aggregating across shifts. Let be the block column with profile where and, for each ,

The MetaMatrix product (Definition 25) gives a block column . Concretely,

Interpretation: over the two days, ICU needs 17 RNs and 8 LPNs in total; the General ward needs 15 RNs and 10 LPNs. The MetaMatrix organizes per–day, per–shift staffing as blocks while allowing standard block algebra for aggregation and downstream costing.

Example 18

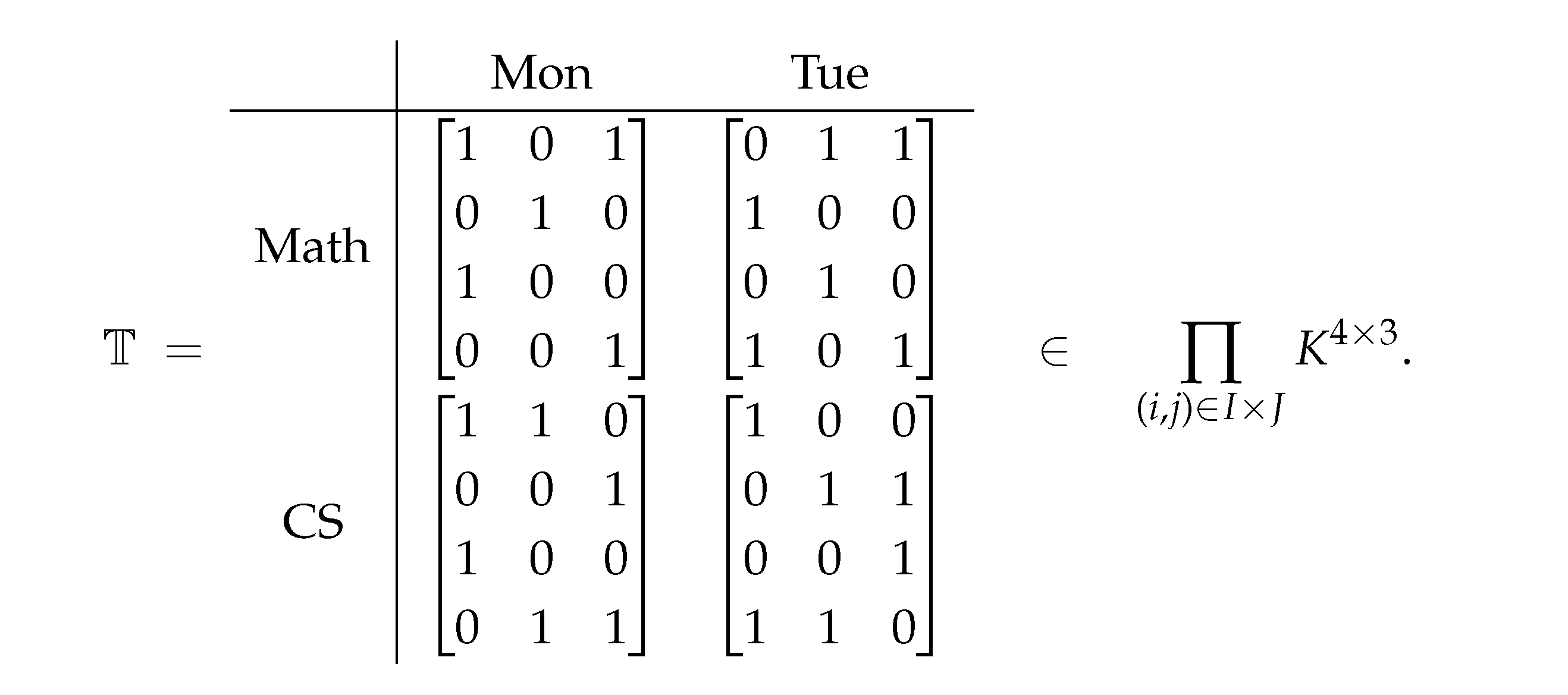

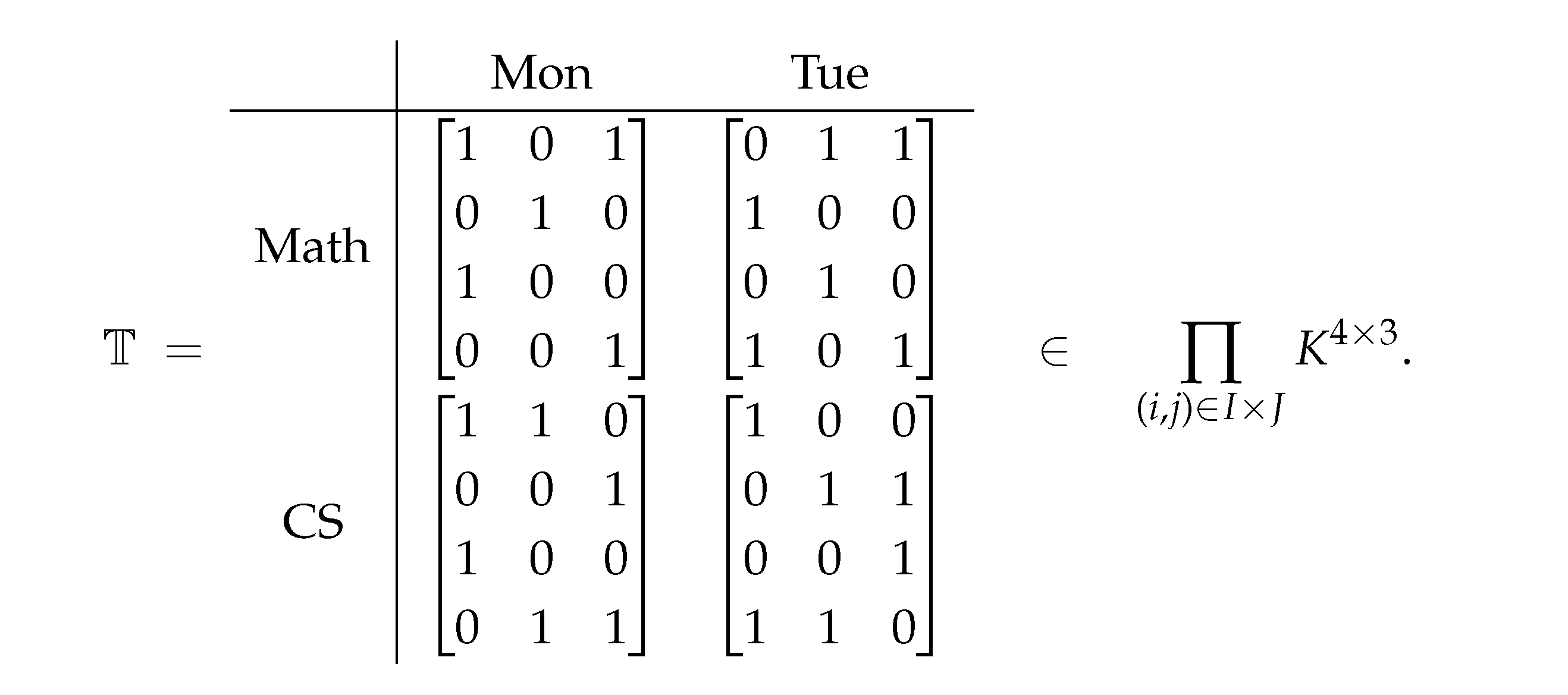

(MetaMatrix — university timetable (periods × rooms within departments × days)). Let (room occupancy). Rows indexdepartments and columns indexdays. Each block encodes a day’s timetable for a department: rows are periods and columns are rooms (1 if the room is used in that period).

Define the MetaMatrix by

Its flattening is a block–assembled occupancy matrix .

From occupancy to seated capacity.Let room capacities be , , and form the block column with profile , where , , and

Then returns theseated capacity per period

accumulated over the two days for department i. For example, for on Monday alone,

so periods 1–4 seat students respectively. The MetaMatrix organizes each (department, day) timetable as a block, while block multiplication with per–day capacity vectors yields usable aggregates (per–period seat counts) without leaving matrix algebra.

Definition 26

(Flattening (canonical block assembly)).

For a MetaMatrix with profile define itsflattening

(assembled block matrix)

by placing each block in its natural block position; i.e., rows are concatenated in the order and columns in the order .

Theorem 6

(Well-definedness and consistency with classical algebra).

Let be MetaMatrices with the same profile , and let have profile compatible with . Then

In particular, ⊕, ⊙, and ⊗ are well defined and associative whenever the inner profiles match, and flattening is a homomorphism into the classical matrix algebra.

Proof. All identities are standard block–matrix equalities. Each entry of (resp. ) equals the blockwise sum (resp. scalar multiple), which matches the definition of ⊕ (resp. ⊙). For products, the block of the classical product equals , which is exactly . Associativity and distributivity follow from the classical laws on blocks of compatible sizes. □

Theorem 7

(MetaMatrix as a MetaStructure; reduction to classical matrices).

Let be the single–sorted signature with function symbols + (binary), · (binary), and (unary). For each pair let

be the –structure on the carrier . Fix a profile and define theMetaStructure operation

with assembling the carrier by block–concatenation and prescribing blockwise addition; similarly define for block multiplication on compatible profiles via the classical block formula. Then:

-

(a)

with is aMetaStructurein the sense of Definition 14.

-

(b)

The data of a MetaMatrix with profile is precisely the input tuple to , and is the carrier produced by . The operations ⊕, ⊙, ⊗ coincide with the meta-operations induced on that carrier.

-

(c)

If for all , then every block is and a MetaMatrix is exactly a classical matrix in . Thus MetaMatrixgeneralizesclassical matrices.

Proof. (a) Uniform carrier constructor and symbol–constructors are given by block assembly and the standard block formulas; naturality (isomorphism–invariance) is immediate from the functorial behavior of direct sums and products of vector spaces. (b) Unwinding the definitions shows that the meta-operations act blockwise exactly as in Definitions 25–26. (c) With blocks, is the identity identification of entries with scalars, so we recover ordinary matrices and operations. □

Definition 27

(Depth, uniform profiles, and recursive objects). Fix adepth and, for each level , fix a profile . Adepth–0 Iterated MetaMatrixis a classical matrix (some ). Recursively, adepth–u Iterated MetaMatrix is a MetaMatrix with profile whose entries are depth– Iterated MetaMatrices, all using the same level– profile.

Example 19

(Iterated MetaMatrix—regional advertising spend (Regions → Stores → Channels × DayTypes)). We build a depth-2 Iterated MetaMatrix as in Definition 27.

Level 0 (classical matrices).Rows arechannels

and columns areday types

. An entry records the (weekly) spend in USD. For a fixed store and week , a block is

Level 1 (MetaMatrix: Stores×Weeks). Let (stores), (weeks), and , (each block ). For the (Region,Month) cell we specify the four level-0 blocks:

Level 2 (MetaMatrix: Regions×Months). Let and with , , so each entry is a level-1 MetaMatrix as above. Thus .

Nested aggregation via MetaMatrix products. Let (sum Weekday+Weekend). At level 1 define the block column by for each . Then the level-1 product

returns, for each store i, thetwo-channel weekly totals summed over weeks

. Compute explicitly:

Store

.

Now sum channels by to obtain per-store monthly totals:

Finally, sum stores (scalar addition) to get the East–Jan regional total:

(The same construction, applied one level higher as with , executes the week-summing step uniformlyinside

each level-1 block, illustrating the recursive nature.)

Example 20

(Iterated MetaMatrix — manufacturing throughput (Regions → Plants → Lines×Days with Stations×Shifts blocks)). We construct a depth-2 Iterated MetaMatrix capturing production counts.

Level 0 (Stations×Shifts). For each line/day, let rows beshifts and columns bestations. An entry is the number of finished units. Thus a block .

Level 1 (MetaMatrix: Lines×Days). Fix lines and days with (each block ). ForPlant North

we set:

ForPlant South

we set:

Each plant thereby determines a level-1 MetaMatrix on .

Level 2 (MetaMatrix: Regions×Weeks).

Let regions , weeks , and profile so that each entry is the corresponding level-1 .

Nested aggregation (units per week). Let to sum stations, and to sum shifts. At level 1 define for . Then, for any line i,

Apply to obtain the line’s two-day total. Compute explicitly:

Plant North.

Plant North weekly total: units.

Plant South.

Plant South weekly total: units.

Regional aggregation (level 2).Placing and as the two blocks of (rows , single column ) exposes a final summation across plants as a level-2 operation (scalar addition of the computed plant totals), yielding the region vector

This example illustrates how the same

block recipe (“sum columns by e, then sum rows by , then sum over days”) is reused recursively inside each entry of the next level.

Definition 28

(Recursive flattening and operations).

Define theflattening

by

i.e., first flatten each entry to a classical block, then assemble the block matrix. Define ⊕, ⊙, and ⊗ on depth–u objects entrywise at level u using the MetaMatrix rules, assuming inner profiles match.

Theorem 8

(Flattening is a homomorphism at every depth).

For each depth and all well–typed and scalars λ,

Proof. Induction on u. The base is trivial. For , apply the induction hypothesis to each entry (depth u), then Theorem 6 at the top MetaMatrix level to assemble blocks; the three identities follow. □

Theorem 9

(Iterated MetaMatrix as an Iterated MetaStructure; reductions).

For each level u let be the class of depth–u Iterated MetaMatrices with fixed profile . The triple

where applies the MetaMatrix constructors to entries in and then assembles via Γ (Definition 14), is anIterated MetaStructure

. Moreover:

-

(a)

(Generalization) Depth 1 recovers MetaMatrix; depth 0 recovers classical matrices.

-

(b)

(Compatibility) The flattening is a natural homomorphism –Mat(Theorem 8).

Proof. The carrier constructors and symbol–constructors are given uniformly at each depth by the block assembly of Definition 28 and the block rules of Definition 25. Naturality is inherited from the functoriality of assembling direct sums/products of vector spaces. (a) follows from the definitions; (b) is Theorem 8. □

5. Conclusions

In this paper we defined

HyperMatrix,

SuperHyperMatrix,

MultiMatrix,

Iterative MultiMatrix,

MetaMatrix, and

Iterated MetaMatrix—all as extensions of the classical notion of a matrix—and we offer a concise examination of their properties. In future work, we plan to consider extensions that incorporate uncertainty and multi-valuedness by employing advanced set-theoretic frameworks such as the

Fuzzy Set [

49,

50,

51,

52],

Intuitionistic Fuzzy Set [

53,

54], Vague Sets [

55,

56,

57],

Hesitant Fuzzy Set [

58,

59,

60], Picture Fuzzy Set [

61,

62,

63],

Neutrosophic Set [

64,

65,

66], and

Plithogenic Set [

67,

68,

69,

70].

Funding

No external funding was received for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research did not involve human participants or animals, and therefore did not require ethical approval.

Data Availability Statement

This paper is theoretical and did not generate or analyze any empirical data. We welcome future studies that apply and test these concepts in practical settings.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

We use generative AI and AI-assisted tools for tasks such as English grammar checking, and We do not employ them in any way that violates ethical standards.

Acknowledgments

We thank all colleagues, reviewers, and readers whose comments and questions have greatly improved this manuscript. We are also grateful to the authors of the works cited herein for providing the theoretical foundations that underpin our study. Finally, we appreciate the institutional and technical support that enabled this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this work.

References

- Smarandache, F. Foundation of SuperHyperStructure & Neutrosophic SuperHyperStructure. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 2024, 63, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tahan, M.; Davvaz, B.; Smarandache, F.; Anis, O. On some neutroHyperstructures. Symmetry 2021, 13, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davvaz, B.; Nezhad, A.D.; Nejad, S.M. Algebraic hyperstructure of observable elementary particles including the Higgs boson. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section A: Physical Sciences 2020, 90, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggero, M.S.; Vougiouklis, T. Hyperstructures in Lie-Santilli admissibility and iso-theories. Ratio Mathematica 2017, 33, 151. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.K.; Das, R.; Das, S.; Debnath, B.K.; Granados, C.; Shil, B.; Das, R. A Comprehensive Study of Neutrosophic SuperHyper BCI-Semigroups and their Algebraic Significance. Transactions on Fuzzy Sets and Systems 2025, 8, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmati, M.; Hamidi, M. Extension of g-algebras to superhyper g-algebras. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 2023, 55, 557–567. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, T. Weak HyperFuzzy Set and Weak SuperHyperFuzzy Set. Computational Methods 2025, 2, 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X. Students’ Innovation Ability Evaluation in Vocational Colleges Based on the STEAM Education Concept: A Neutrosophic SuperHyper Pentapartitioned Process Model. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 2025, 93, 250–261. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, T. Medical SuperHyperStructure and Healthcare SuperHyperStructure. Journal of Medicine and Health Research 2025, 10, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. A Neutrosophic SuperHyperModal Framework for the Multilayered Evaluation of New Media Marketing Strategies in the Automotive Industry. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 2025, 88, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Jech, T. Set theory: The third millennium edition, revised and expanded; Springer, 2003.

- Smarandache, F. SuperHyperFunction, SuperHyperStructure, Neutrosophic SuperHyperFunction and Neutrosophic SuperHyperStructure: Current understanding and future directions; Infinite Study, 2023.

- Smarandache, F. Introduction to SuperHyperAlgebra and Neutrosophic SuperHyperAlgebra. Journal of Algebraic Hyperstructures and Logical Algebras 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, T.; Smarandache, F. A Unified Framework for U-Structures and Functorial Structure: Managing Super, Hyper, SuperHyper, Tree, and Forest Uncertain Over/Under/Off Models. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 2025, 91, 337–380. [Google Scholar]

- Selvachandran, G.; Salleh, A.R. Hypergroup theory applied to fuzzy soft sets. Global Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 2015, 11, 825–834. [Google Scholar]

- Stenstrom, B. Rings of quotients: an introduction to methods of ring theory; Vol. 217, Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- Jun, Y.B.; Park, C.H.; Alshehri, N.O. Hypervector spaces based on intersectional soft sets. In Proceedings of the Abstract and Applied Analysis. Wiley Online Library, Vol. 2014; p. 784523. [Google Scholar]

- Tallini, M.S. Hypervector spaces. In Proceedings of the Proceeding of the 4th International Congress in Algebraic Hyperstructures and Applications; 1991; pp. 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J.L.; Yellen, J.; Anderson, M. Graph theory and its applications; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018.

- Diestel, R. Graph theory 3rd ed. Graduate texts in mathematics 2005, 173, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Diestel, R. Graph theory; Springer (print edition); Reinhard Diestel (eBooks), 2024.

- Vougioukli, S. Helix hyperoperation in teaching research. Science & Philosophy 2020, 8, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Vougioukli, S. Hyperoperations defined on sets of S -helix matrices. 2020.

- Rezaei, A.; Smarandache, F.; Mirvakili, S. Applications of (Neutro/Anti)sophications to Semihypergroups. Journal of Mathematics 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vougioukli, S. HELIX-HYPEROPERATIONS ON LIE-SANTILLI ADMISSIBILITY. Algebras Groups and Geometries 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsini, P.; Leoreanu, V. Applications of hyperstructure theory; Vol. 5, Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

- Novák, M.; Křehlík, Š.; Ovaliadis, K. Elements of hyperstructure theory in UWSN design and data aggregation. Symmetry 2019, 11, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguz, G.; Davvaz, B. Soft topological hyperstructure. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 40, 8755–8764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smarandache, F. SuperHyperStructure & Neutrosophic SuperHyperStructure, 2024. Accessed: 2024-12-01.

- Shinoj, T.; John, S.J. Intuitionistic fuzzy multisets and its application in medical diagnosis. World academy of science, engineering and technology 2012, 6, 1418–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Ejegwa, P. New operations on intuitionistic fuzzy multisets. Journal of Mathematics and Informatics 2015, 3, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Girish, K.; John, S.J. Rough Multisets and Information Multisystems. Advances in Decision sciences 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girish, K.; John, S.J. On rough multiset relations. International Journal of Granular Computing, Rough Sets and Intelligent Systems 2014, 3, 306–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, T. Iterative Multistructure and Curried Iterative Multistructure: Graph, Function, Chemical Structure, and beyond 2025.

- Fujita, T. Introduction for Structure, HyperStructure, SuperHyperStructure, MultiStructure, Iterative MultiStructure, TreeStructure, and ForestStructure 2025.

- Fujita, T. MetaStructure, Meta-HyperStructure, and Meta-SuperHyperStructure, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Fujita, T. MetaHyperGraphs, MetaSuperHyperGraphs, and Iterated MetaGraphs: Modeling Graphs of Graphs, Hypergraphs of Hypergraphs, Superhypergraphs of Superhypergraphs, and Beyond, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Horn, R.A.; Johnson, C.R. Matrix analysis. 1985.

- Yaz, E.E. Linear Matrix Inequalities In System And Control Theory. Proceedings of the IEEE 1998, 86, 2473–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, G.H. Matrix computations. 1983.

- Chrzeszczyk, A.; Kochanowski, J. Matrix Computations. In Proceedings of the Encyclopedia of Parallel Computing; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, T.; de Souza, A.H.; Fifty, C.; Yu, T.; Weinberger, K.Q. Simplifying Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.D.; Sebastian, H.; y, S. Algorithms for Non-negative Matrix Factorization. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Engler, A.J.; Engler, A.J.; Sen, S.; Sen, S.; Sweeney, H.L.; Discher, D.E. Matrix Elasticity Directs Stem Cell Lineage Specification. Cell 2006, 126, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motameni, M.; Ameri, R.; Sadeghi, R. Hypermatrix Based on Krasner Hypervector Spaces. 2013.

- Fujita, T. A theoretical exploration of hyperconcepts: Hyperfunctions, hyperrandomness, hyperdecision-making, and beyond (including a survey of hyperstructures). Advancing Uncertain Combinatorics through Graphization, Hyperization, and Uncertainization: Fuzzy, Neutrosophic, Soft, Rough, and Beyond 2025, p. 111.

- Tropp, J.A. Tropp, J.A. An Introduction to Matrix Concentration Inequalities. ArXiv 2015, abs/1501.01571.

- Bellman, R. Introduction to Matrix Analysis. 1972.

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets. Information and control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.; Luqman, A. Fuzzy hypergraphs and related extensions; Springer, 2020.

- Al-Hawary, T. Complete fuzzy graphs. International Journal of Mathematical Combinatorics 2011, 4, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Nishad, T.; Al-Hawary, T.A.; Harif, B.M. General Fuzzy Graphs. Ratio Mathematica 2023, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Atanassov, K.T. Circular intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems 2020, 39, 5981–5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanassov, K.T.; Gargov, G. Intuitionistic fuzzy logics; Springer, 2017.

- Lu, A.; Ng, W. Vague sets or intuitionistic fuzzy sets for handling vague data: which one is better? In Proceedings of the International conference on conceptual modeling. Springer; 2005; pp. 401–416. [Google Scholar]

- Gau, W.L.; Buehrer, D.J. Vague sets. IEEE transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics 1993, 23, 610–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustince, H.; Burillo, P. Vague sets are intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy sets and systems 1996, 79, 403–405. [Google Scholar]

- Torra, V.; Narukawa, Y. On hesitant fuzzy sets and decision. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE international conference on fuzzy systems. IEEE; 2009; pp. 1378–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Torra, V. Hesitant fuzzy sets. International journal of intelligent systems 2010, 25, 529–539. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. Hesitant fuzzy sets theory; Vol. 314, Springer, 2014.

- Das, S.; Ghorai, G.; Pal, M. Picture fuzzy tolerance graphs with application. Complex & Intelligent Systems 2022, 8, 541–554. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, W.A.; Arif, W.; NGUYEN, Q.H.; Le, T.T.; Van Pham, H. Picture Fuzzy Directed Hypergraphs with applications towards decision-making and managing hazardous chemicals. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cuong, B.C.; Kreinovich, V. Picture fuzzy sets-a new concept for computational intelligence problems. In Proceedings of the 2013 third world congress on information and communication technologies (WICT 2013). IEEE; 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Smarandache, F.; Jdid, M. An Overview of Neutrosophic and Plithogenic Theories and Applications 2023.

- Broumi, S.; Talea, M.; Bakali, A.; Smarandache, F. Single valued neutrosophic graphs. Journal of New theory 2016, 10, 86–101. [Google Scholar]

- Broumi, S.; Talea, M.; Bakali, A.; Smarandache, F.; Kumar, P.K. Shortest path problem on single valued neutrosophic graphs. In Proceedings of the 2017 international symposium on networks, computers and communications (ISNCC). IEEE; 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sultana, F.; Gulistan, M.; Ali, M.; Yaqoob, N.; Khan, M.; Rashid, T.; Ahmed, T. A study of plithogenic graphs: applications in spreading coronavirus disease (COVID-19) globally. Journal of ambient intelligence and humanized computing 2023, 14, 13139–13159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, W.V.; Ilanthenral, K.; Smarandache, F. Plithogenic Graphs; Infinite Study, 2020.

- Sathya, P.; Martin, N.; Smarandache, F. Plithogenic Forest Hypersoft Sets in Plithogenic Contradiction Based Multi-Criteria Decision Making. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 2024, 73, 668–693. [Google Scholar]

- Smarandache, F. Extension of HyperGraph to n-SuperHyperGraph and to Plithogenic n-SuperHyperGraph, and Extension of HyperAlgebra to n-ary (Classical-/Neutro-/Anti-) HyperAlgebra; Infinite Study, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).