Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

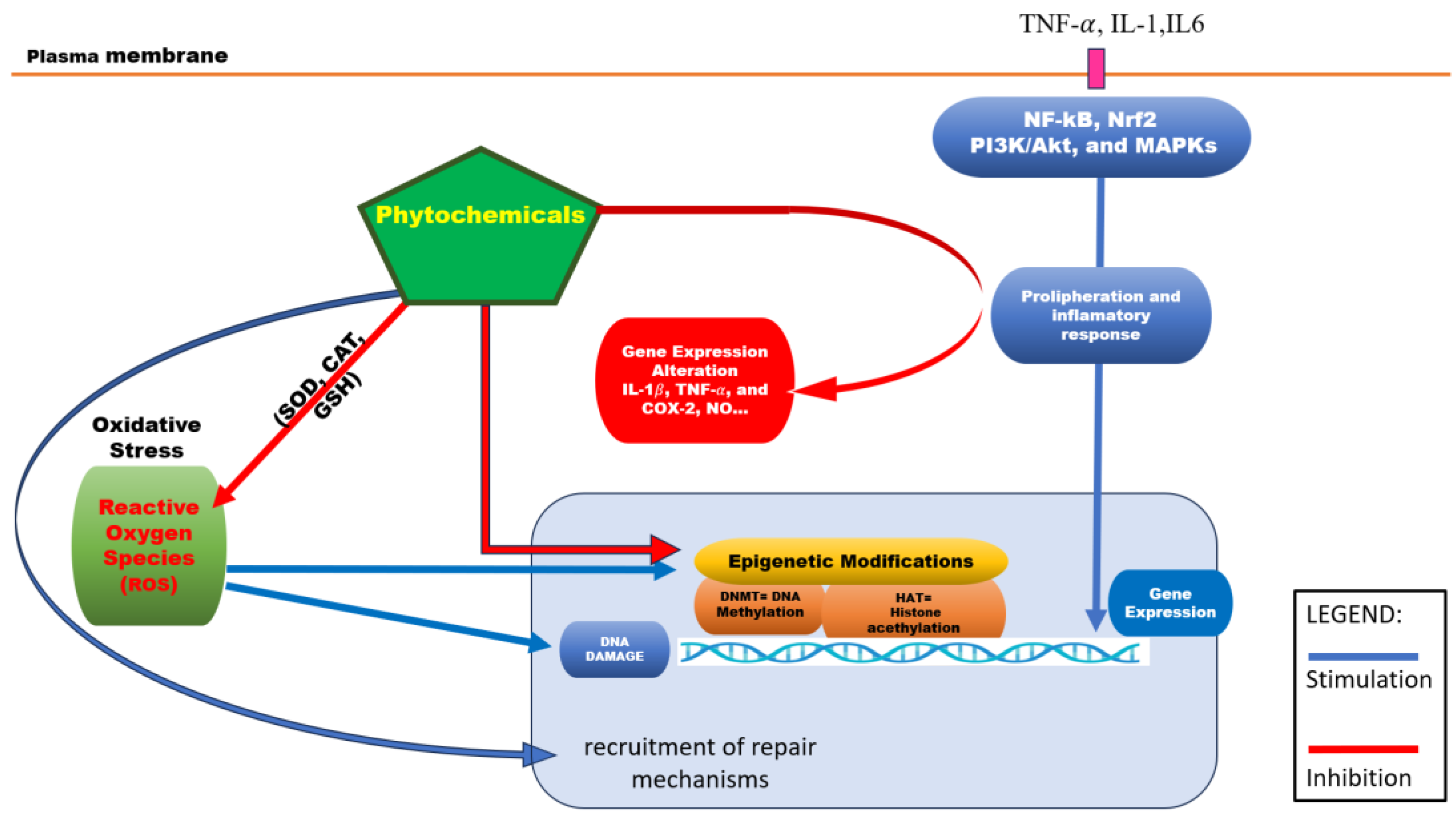

2. Epigenetic Dysregulations in Chronic Diseases

2.1. Oxidative Stress Impacting Epigenetic Mechanisms

2.2. Epigenetic Dysregulations in Inflammation Process

| Class of compound | Phytochemicals | Type of study | Antioxidant | Anti-inflammatory | Epigenetic modulator | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | Hesperidin | MCF-7 ( 50 µM) |

Increases activities of SOD, CAT, GSH; reduces lipid peroxidation; Activates Nrf2 |

Reduces expressions of TNF-α, IL-6 ex-pression | Inhibits DNMT1; hypo-methylation of p16 promoter | [118,119,120] |

| Phloretin | RAW 264.7 macrophages (25 µM); A549 cells |

Inhibits ROS production and increases GSH activity | Suppresses NF-κB activation and reduces iNOS and COX-2 expression | Inhibits HDAC; increases histone acetylation, p21 expression | [121,122,123] | |

| Genistein | MCF-7, PC3, HL-60 cells | Increases antioxidant enzymes, reduces lipid peroxidation | Reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β) expression via NF-κB | Inhibits DNMT1, demethylates and reactivates tumor suppressor genes | [124,125,126,127] | |

| Phenolic acids | Caffeic acid | Caco-2, HeLa cells (20 µM) |

Neutralizes free radicals and boosts antioxidant enzymes | Inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines and NF-κB activation | Inhibits DNMT; DNA hypomethylation; gene reactivation | [128,129,130] |

| Coumaric acid | LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells; MDA-MB-231 cells (30 µM) |

Free radical scavenger and increases SOD activity | Reduces NO production and COX-2 expression | Inhibits HDAC; increases histone acetylation | [131,132,133] | |

| Terpenoids | Lycopene | HepG2, PC3 cells (10 µM) |

Reduces ROS and increases antioxidant enzyme activity | Inhibits COX-2 expression and lowers prostaglandin E2 levels | ||

| Silibinin | HepG2, DU145 cells (50 µM) | Increases SOD and CAT activity; reduces lipid peroxidation | Inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines and NF-κB activation | Inhibits DNMT and HDAC; hypomethylation and histone acetylation | [134,135,136] | |

| Sesquit-erpenoids | Artemisinin | HeLa cells (50 µM) |

Reduces oxidative stress by lowering ROS and activating Nrf2 | Inhibits IL-1β, TNF-α, and COX-2 expression | — | [137] |

| Mono-terpenoids | Geraniol | RAW 264.7 macrophages (50 µM) | Reduces ROS production and increases GSH activity | Suppresses NO, IL-6, and TNF-α production by inhibiting NF-κB | — | [138] |

| Organo-sulfur com-pounds | Allyl mercaptan | HUVEC, HT-29 cells (15 µM) | Enhances antioxidant enzyme activity and reduces ROS | Inhibits adhesion molecules and reduces vascular inflammation | Inhibits HDAC; increases histone acetylation; gene reactivation | [139,140,141,142] |

4. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anjali; Kumar, S.; Korra, T.; Thakur, R.; Arutselvan, R.; Kashyap, A.S.; Nehela, Y.; Chaplygin, V.; Minkina, T.; Keswani, C. Role of Plant Secondary Metabolites in Defence and Transcriptional Regulation in Response to Biotic Stress. Plant Stress 2023, 8, 100154. [CrossRef]

- Full Text.

- Rabizadeh, F.; Mirian, M.S.; Doosti, R.; Kiani-Anbouhi, R.; Eftekhari, E. Phytochemical Classification of Medicinal Plants Used in the Treatment of Kidney Disease Based on Traditional Persian Medicine. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2022, 2022, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Veiga, M.; Costa, E.M.; Silva, S.; Pintado, M. Impact of Plant Extracts upon Human Health: A Review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2020, 60, 873–886. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A.G.; Efferth, T.; Shikov, A.N.; Pozharitskaya, O.N.; Kuchta, K.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Banerjee, S.; Heinrich, M.; Wu, W.; Guo, D.; et al. Evolution of the Adaptogenic Concept from Traditional Use to Medical Systems: Pharmacology of Stress- and Aging-related Diseases. Medicinal Research Reviews 2021, 41, 630–703. [CrossRef]

- Chihomvu, P.; Ganesan, A.; Gibbons, S.; Woollard, K.; Hayes, M.A. Phytochemicals in Drug Discovery—A Confluence of Tradition and Innovation. IJMS 2024, 25, 8792. [CrossRef]

- Medicinal Plants and Their Traditional Uses in Different Locations. In Phytomedicine; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 207–223 ISBN 978-0-12-824109-7.

- Dar, R.A.; Shahnawaz, M.; Ahanger, M.A.; Majid, I.U. Exploring the Diverse Bioactive Compounds from Medicinal Plants: A Review. J Phytopharmacol 2023, 12, 189–195. [CrossRef]

- Howes, M.R.; Perry, N.S.L.; Vásquez-Londoño, C.; Perry, E.K. Role of Phytochemicals as Nutraceuticals for Cognitive Functions Affected in Ageing. British J Pharmacology 2020, 177, 1294–1315. [CrossRef]

- George, B.P.; Chandran, R.; Abrahamse, H. Role of Phytochemicals in Cancer Chemoprevention: Insights. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1455. [CrossRef]

- Albulescu, L.; Suciu, A.; Neagu, M.; Tanase, C.; Pop, S. Differential Biological Effects of Trifolium Pratense Extracts—In Vitro Studies on Breast Cancer Models. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1435. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.H. Potential Synergy of Phytochemicals in Cancer Prevention: Mechanism of Action. The Journal of Nutrition 2004, 134, 3479S-3485S. [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, V.S.; Popa, A.; Alexandru, A.; Manole, E.; Neagu, M.; Pop, S. Dietary Phytoestrogens and Their Metabolites as Epigenetic Modulators with Impact on Human Health. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1893. [CrossRef]

- Alarabei, A.A.; Abd Aziz, N.A.L.; Ab Razak, N.I.; Abas, R.; Bahari, H.; Abdullah, M.A.; Hussain, M.K.; Abdul Majid, A.M.S.; Basir, R. Immunomodulating Phytochemicals: An Insight into Their Potential Use in Cytokine Storm Situations. Adv Pharm Bull 2023. [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Rajasingh, S.; Cao, T.; Dawn, B.; Rajasingh, J. Epigenetic Dysfunctional Diseases and Therapy for Infection and Inflammation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2017, 1863, 518–528. [CrossRef]

- Tiffon, C. The Impact of Nutrition and Environmental Epigenetics on Human Health and Disease. IJMS 2018, 19, 3425. [CrossRef]

- Gibney, E.R.; Nolan, C.M. Epigenetics and Gene Expression. Heredity 2010, 105, 4–13. [CrossRef]

- Bure, I.V.; Nemtsova, M.V.; Kuznetsova, E.B. Histone Modifications and Non-Coding RNAs: Mutual Epigenetic Regulation and Role in Pathogenesis. IJMS 2022, 23, 5801. [CrossRef]

- The Role of DNA Methylation and Histone Modifications in Transcriptional Regulation in Humans. In Subcellular Biochemistry; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2013; pp. 289–317 ISBN 978-94-007-4524-7.

- Lorenzo, P.M.; Izquierdo, A.G.; Rodriguez-Carnero, G.; Fernández-Pombo, A.; Iglesias, A.; Carreira, M.C.; Tejera, C.; Bellido, D.; Martinez-Olmos, M.A.; Leis, R.; et al. Epigenetic Effects of Healthy Foods and Lifestyle Habits from the Southern European Atlantic Diet Pattern: A Narrative Review. Advances in Nutrition 2022, 13, 1725–1747. [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Qiao, X.; Fang, Y.; Guo, R.; Bai, P.; Liu, S.; Li, T.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, S.; Na, Z.; et al. Epigenetics-Targeted Drugs: Current Paradigms and Future Challenges. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Bannister, A.J.; Kouzarides, T. Regulation of Chromatin by Histone Modifications. Cell Res 2011, 21, 381–395. [CrossRef]

- Handy, D.E.; Castro, R.; Loscalzo, J. Epigenetic Modifications: Basic Mechanisms and Role in Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2011, 123, 2145–2156. [CrossRef]

- Gillette, T.G.; Hill, J.A. Readers, Writers, and Erasers: Chromatin as the Whiteboard of Heart Disease. Circulation Research 2015, 116, 1245–1253. [CrossRef]

- Pop, S.; Enciu, A.M.; Tarcomnicu, I.; Gille, E.; Tanase, C. Phytochemicals in Cancer Prevention: Modulating Epigenetic Alterations of DNA Methylation. Phytochem Rev 2019, 18, 1005–1024. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X. TET (Ten-Eleven Translocation) Family Proteins: Structure, Biological Functions and Applications. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.D.; Le, T.; Fan, G. DNA Methylation and Its Basic Function. Neuropsychopharmacol 2013, 38, 23–38. [CrossRef]

- Mellor, J. Dynamic Nucleosomes and Gene Transcription. Trends in Genetics 2006, 22, 320–329. [CrossRef]

- Becker, P.B.; Workman, J.L. Nucleosome Remodeling and Epigenetics. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2013, 5, a017905–a017905. [CrossRef]

- Kaikkonen, M.U.; Lam, M.T.Y.; Glass, C.K. Non-Coding RNAs as Regulators of Gene Expression and Epigenetics. Cardiovascular Research 2011, 90, 430–440. [CrossRef]

- Statello, L.; Guo, C.-J.; Chen, L.-L.; Huarte, M. Gene Regulation by Long Non-Coding RNAs and Its Biological Functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 96–118. [CrossRef]

- Pop, S.; Enciu, A.; Necula, L.G.; Tanase, C. Long Non-coding RNAs in Brain Tumours: Focus on Recent Epigenetic Findings in Glioma. J Cellular Molecular Medi 2018, 22, 4597–4610. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, H.; Hu, Q.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Ren, J.; Zhu, F.; Liu, G.-H. Epigenetic Regulation of Aging: Implications for Interventions of Aging and Diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7. [CrossRef]

- Copeland, R.A.; Olhava, E.J.; Scott, M.P. Targeting Epigenetic Enzymes for Drug Discovery. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2010, 14, 505–510. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-H.; Kuo, M.-Z.; Chen, I.-A.; Lin, C.-J.; Hsu, V.; HuangFu, W.-C.; Wu, T.-Y. Epigenetic Modifications as Novel Therapeutic Strategies of Cancer Chemoprevention by Phytochemicals. Pharm Res 2025, 42, 69–78. [CrossRef]

- Casalino, L.; Verde, P. Multifaceted Roles of DNA Methylation in Neoplastic Transformation, from Tumor Suppressors to EMT and Metastasis. Genes 2020, 11, 922. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.V.; Nestler, K.A.; Chiappinelli, K.B. Therapeutic Targeting of DNA Methylation Alterations in Cancer. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2024, 258, 108640. [CrossRef]

- Brückmann, N.H.; Pedersen, C.B.; Ditzel, H.J.; Gjerstorff, M.F. Epigenetic Reprogramming of Pericentromeric Satellite DNA in Premalignant and Malignant Lesions. Molecular Cancer Research 2018, 16, 417–427. [CrossRef]

- Sales, V.M.; Ferguson-Smith, A.C.; Patti, M.-E. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Transmission of Metabolic Disease across Generations. Cell Metabolism 2017, 25, 559–571. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, X.; Ding, L.; Liu, D.; Xu, H. DNMT1-Mediated PPARα Methylation Aggravates Damage of Retinal Tissues in Diabetic Retinopathy Mice. Biol Res 2021, 54. [CrossRef]

- Keleher, M.R.; Zaidi, R.; Hicks, L.; Shah, S.; Xing, X.; Li, D.; Wang, T.; Cheverud, J.M. A High-Fat Diet Alters Genome-Wide DNA Methylation and Gene Expression in SM/J Mice. BMC Genomics 2018, 19. [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.; Barnes, S.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Morrow, C.; Salvador, C.; Skibola, C.; Tollefsbol, T.O. Influences of Diet and the Gut Microbiome on Epigenetic Modulation in Cancer and Other Diseases. Clin Epigenet 2015, 7. [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Toxicity, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Chronic Diseases and Aging. Arch Toxicol 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Rath, S.; Adhami, V.M.; Mukhtar, H. Targeting Epigenome with Dietary Nutrients in Cancer: Current Advances and Future Challenges. Pharmacological Research 2018, 129, 375–387. [CrossRef]

- Aanniz, T.; Bouyahya, A.; Balahbib, A.; El Kadri, K.; Khalid, A.; Makeen, H.A.; Alhazmi, H.A.; El Omari, N.; Zaid, Y.; Wong, R.S.-Y.; et al. Natural Bioactive Compounds Targeting DNA Methyltransferase Enzymes in Cancer: Mechanisms Insights and Efficiencies. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2024, 392, 110907. [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2017, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Sawalha, A.H. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Epigenetic Changes Underlying Autoimmunity. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2022, 36, 423–440. [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Chaturvedi, M.M.; Aggarwal, B.B. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Cancer: How Are They Linked? Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2010, 49, 1603–1616. [CrossRef]

- The Double-Edged Sword Role of ROS in Cancer. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Mechanistic Aspects; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1103–1119 ISBN 978-981-15-9410-6.

- Silva-Llanes, I.; Shin, C.H.; Jiménez-Villegas, J.; Gorospe, M.; Lastres-Becker, I. The Transcription Factor NRF2 Has Epigenetic Regulatory Functions Modulating HDACs, DNMTs, and miRNA Biogenesis. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 641. [CrossRef]

- He, W.-J.; Lv, C.-H.; Chen, Z.; Shi, M.; Zeng, C.-X.; Hou, D.-X.; Qin, S. The Regulatory Effect of Phytochemicals on Chronic Diseases by Targeting Nrf2-ARE Signaling Pathway. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 236. [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, T.; Petry, A.; Shvetsova, A.; Gerhold, J.M.; Görlach, A. The Epigenetic Landscape Related to Reactive Oxygen Species Formation in the Cardiovascular System. British J Pharmacology 2017, 174, 1533–1554. [CrossRef]

- Madugundu, G.S.; Cadet, J.; Wagner, J.R. Hydroxyl-Radical-Induced Oxidation of 5-Methylcytosine in Isolated and Cellular DNA. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42, 7450–7460. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, I.; Alghamdi, S.; Rajab, B.S.; Babalghith, A.O.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Islam, S.; Islam, Md.R. Flavonoids a Bioactive Compound from Medicinal Plants and Its Therapeutic Applications. BioMed Research International 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lü, J.; Lin, P.H.; Yao, Q.; Chen, C. Chemical and Molecular Mechanisms of Antioxidants: Experimental Approaches and Model Systems. J Cellular Molecular Medi 2010, 14, 840–860. [CrossRef]

- Andrés, C.M.C.; Pérez De La Lastra, J.M.; Juan, C.A.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. Antioxidant Metabolism Pathways in Vitamins, Polyphenols, and Selenium: Parallels and Divergences. IJMS 2024, 25, 2600. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, M.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Tran, K.; Reddy, S.P.; Malik, A.B. Reactive Oxygen Species in Inflammation and Tissue Injury. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2014, 20, 1126–1167. [CrossRef]

- Mucha, P.; Skoczyńska, A.; Małecka, M.; Hikisz, P.; Budzisz, E. Overview of the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Selected Plant Compounds and Their Metal Ions Complexes. Molecules 2021, 26, 4886. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2345. [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Chen, Z.; Wen, Y.; Yi, Y.; Lv, C.; Zeng, C.; Chen, L.; Shi, M. Phytochemical Activators of Nrf2: A Review of Therapeutic Strategy in Diabetes. ABBS 2022. [CrossRef]

- Baird, L.; Yamamoto, M. The Molecular Mechanisms Regulating the KEAP1-NRF2 Pathway. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2020, 40. [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.-A.; Kwak, M.-K. The Nrf2 System as a Potential Target for the Development of Indirect Antioxidants. Molecules 2010, 15, 7266–7291. [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Ru, X.; Wen, T. NRF2, a Transcription Factor for Stress Response and Beyond. IJMS 2020, 21, 4777. [CrossRef]

- Carlos-Reyes, Á.; López-González, J.S.; Meneses-Flores, M.; Gallardo-Rincón, D.; Ruíz-García, E.; Marchat, L.A.; Astudillo-de La Vega, H.; Hernández De La Cruz, O.N.; López-Camarillo, C. Dietary Compounds as Epigenetic Modulating Agents in Cancer. Front. Genet. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory Responses and Inflammation-Associated Diseases in Organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218. [CrossRef]

- Yasmeen, F.; Pirzada, R.H.; Ahmad, B.; Choi, B.; Choi, S. Understanding Autoimmunity: Mechanisms, Predisposing Factors, and Cytokine Therapies. IJMS 2024, 25, 7666. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Meng, Y.; Zhou, L.; Qiu, L.; Wang, H.; Su, D.; Zhang, B.; Chan, K.; Han, J. Targeting Epigenetic Regulators for Inflammation: Mechanisms and Intervention Therapy. MedComm 2022, 3. [CrossRef]

- Cronkite, D.A.; Strutt, T.M. The Regulation of Inflammation by Innate and Adaptive Lymphocytes. Journal of Immunology Research 2018, 2018, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, Z.; Shen, W.; Huang, G.; Sedivy, J.M.; Wang, H.; Ju, Z. Inflammation, Epigenetics, and Metabolism Converge to Cell Senescence and Ageing: The Regulation and Intervention. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Miao, C. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Immune Remodeling in Sepsis: Targeting Histone Modification. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kaszycki, J.; Kim, M. Epigenetic Regulation of Transcription Factors Involved in NLRP3 Inflammasome and NF-kB Signaling Pathways. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16. [CrossRef]

- Jurkowska, R.Z. Role of Epigenetic Mechanisms in the Pathogenesis of Chronic Respiratory Diseases and Response to Inhaled Exposures: From Basic Concepts to Clinical Applications. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2024, 264, 108732. [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, B.; Carinci, M.; Previati, M.; Giacovazzi, S.; Della Sala, M.; Gafà, R.; Lanza, G.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Pinton, P.; Giorgi, C. Epigenetic Regulation: A Link between Inflammation and Carcinogenesis. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 1221. [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.Y.X.; Zhang, J.; Tee, W.-W. Epigenetic Regulation of Inflammatory Signaling and Inflammation-Induced Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 931493. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-H.; Dang, Y.-Q.; Ji, G. Role of Epigenetics in Transformation of Inflammation into Colorectal Cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2019, 25, 2863–2877. [CrossRef]

- Pandareesh, M.D.; Kameshwar, V.H.; Byrappa, K. Prostate Carcinogenesis: Insights in Relation to Epigenetics and Inflammation. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 2021, 21, 253–267. [CrossRef]

- Rostami, A.; White, K.; Rostami, K. Pro and Anti-Inflammatory Diets as Strong Epigenetic Factors in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. World J Gastroenterol 2024, 30, 3284–3289. [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Karthik, N.; Taneja, R. Crosstalk Between Inflammatory Signaling and Methylation in Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Bagni, G.; Biancalana, E.; Chiara, E.; Costanzo, I.; Malandrino, D.; Lastraioli, E.; Palmerini, M.; Silvestri, E.; Urban, M.L.; Emmi, G. Epigenetics in Autoimmune Diseases: Unraveling the Hidden Regulators of Immune Dysregulation. Autoimmunity Reviews 2025, 24, 103784. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ni, S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Xie, M.; Huang, X. Molecular Insights and Clinical Implications of DNA Methylation in Sepsis-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: A Narrative Review. BMC Nephrol 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Bacher, S.; Meier-Soelch, J.; Kracht, M.; Schmitz, M.L. Regulation of Transcription Factor NF-κB in Its Natural Habitat: The Nucleus. Cells 2021, 10, 753. [CrossRef]

- Grabiec, A.M.; Tak, P.P.; Reedquist, K.A. Targeting Histone Deacetylase Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Asthma as Prototypes of Inflammatory Disease: Should We Keep Our HATs On? Arthritis Res Ther 2008, 10, 226. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Gao, T.; Zhong, K.; Shan, K.; Ye, G.; Ke, Y.; et al. Histone Deacetylase in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Novel Insights. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2025, 18. [CrossRef]

- Raisch, J. Role of microRNAs in the Immune System, Inflammation and Cancer. WJG 2013, 19, 2985. [CrossRef]

- Alivernini, S.; Gremese, E.; McSharry, C.; Tolusso, B.; Ferraccioli, G.; McInnes, I.B.; Kurowska-Stolarska, M. MicroRNA-155—at the Critical Interface of Innate and Adaptive Immunity in Arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, M.J.; Shanle, E.K.; Khan, A.; Chua, K.F.; Hong, T.; Boxer, L.D.; Allis, C.D.; Josefowicz, S.Z.; Garcia, B.A.; Rothbart, S.B.; et al. HDAC Inhibition Results in Widespread Alteration of the Histone Acetylation Landscape and BRD4 Targeting to Gene Bodies. Cell Reports 2021, 34, 108638. [CrossRef]

- Phimmachanh, M.; Han, J.Z.R.; O’Donnell, Y.E.I.; Latham, S.L.; Croucher, D.R. Histone Deacetylases and Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors in Neuroblastoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Al Bitar, S.; Gali-Muhtasib, H. The Role of the Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor P21cip1/Waf1 in Targeting Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Novel Therapeutics. Cancers 2019, 11, 1475. [CrossRef]

- Sturmlechner, I.; Zhang, C.; Sine, C.C.; Van Deursen, E.-J.; Jeganathan, K.B.; Hamada, N.; Grasic, J.; Friedman, D.; Stutchman, J.T.; Can, I.; et al. P21 Produces a Bioactive Secretome That Places Stressed Cells under Immunosurveillance. Science 2021, 374. [CrossRef]

- Arora, I.; Sharma, M.; Sun, L.Y.; Tollefsbol, T.O. The Epigenetic Link between Polyphenols, Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Genes 2020, 11, 1094. [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, A.; Bland, J.S.; Chandra, A.; Malani, S.S.; Smith, R.; Mendez, T.L.; Dwaraka, V.B. The Impact of a Polyphenol-Rich Supplement on Epigenetic and Cellular Markers of Immune Age: A Pilot Clinical Study. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Bergonzini, M.; Loreni, F.; Lio, A.; Russo, M.; Saitto, G.; Cammardella, A.; Irace, F.; Tramontin, C.; Chello, M.; Lusini, M.; et al. Panoramic on Epigenetics in Coronary Artery Disease and the Approach of Personalized Medicine. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2864. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Hou, L.; Luo, W.; Pan, L.-H.; Li, X.; Tan, H.-P.; Wu, R.-D.; Lu, H.; Yao, K.; Mu, M.-D.; et al. Myocardial Infarction Drives Trained Immunity of Monocytes, Accelerating Atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J 2024, 45, 669–684. [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, L.; Fabbri, E. Inflammageing: Chronic Inflammation in Ageing, Cardiovascular Disease, and Frailty. Nat Rev Cardiol 2018, 15, 505–522. [CrossRef]

- Marsit, C.J. Influence of Environmental Exposure on Human Epigenetic Regulation. Journal of Experimental Biology 2015, 218, 71–79. [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Mandhare, A.; Tryphena, K.P.; Srivastava, S.; Shaikh, M.F.; Singh, S.B.; Khatri, D.K. Epigenetics in Depression and Gut-Brain Axis: A Molecular Crosstalk. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Bai, G.; Pang, J.; Wu, M.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Xia, Y. Implications of Gut Microbiota-Mediated Epigenetic Modifications in Intestinal Diseases. Gut Microbes 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shao, J.; Liao, Y.-T.; Wang, L.-N.; Jia, Y.; Dong, P.; Liu, Z.; He, D.; Li, C.; Zhang, X. Regulation of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Immune System. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Khurana Hershey, G.K. Genetic and Epigenetic Influence on the Response to Environmental Particulate Matter. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2012, 129, 33–41. [CrossRef]

- Rubio, K.; Hernández-Cruz, E.Y.; Rogel-Ayala, D.G.; Sarvari, P.; Isidoro, C.; Barreto, G.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Nutriepigenomics in Environmental-Associated Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 771. [CrossRef]

- Erratum. ILAR Journal 2017, 58, 413–413. [CrossRef]

- Breton, C.V.; Landon, R.; Kahn, L.G.; Enlow, M.B.; Peterson, A.K.; Bastain, T.; Braun, J.; Comstock, S.S.; Duarte, C.S.; Hipwell, A.; et al. Exploring the Evidence for Epigenetic Regulation of Environmental Influences on Child Health across Generations. Commun Biol 2021, 4. [CrossRef]

- Alegría-Torres, J.A.; Baccarelli, A.; Bollati, V. Epigenetics and Lifestyle. Epigenomics 2011, 3, 267–277. [CrossRef]

- Barouki, R.; Melén, E.; Herceg, Z.; Beckers, J.; Chen, J.; Karagas, M.; Puga, A.; Xia, Y.; Chadwick, L.; Yan, W.; et al. Epigenetics as a Mechanism Linking Developmental Exposures to Long-Term Toxicity. Environment International 2018, 114, 77–86. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wu, H.; Zhong, M.; Chen, Y.; Su, W.; Li, P. Epigenetic Regulation by Naringenin and Naringin: A Literature Review Focused on the Mechanisms Underlying Its Pharmacological Effects. Fitoterapia 2025, 181, 106353. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Su, H.; Guo, Z.; Li, H.; Jiang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Li, C. Rubus Occidentalis and Its Bioactive Compounds against Cancer: From Molecular Mechanisms to Translational Advances. Phytomedicine 2024, 126, 155029. [CrossRef]

- Babar, Q.; Saeed, A.; Tabish, T.A.; Pricl, S.; Townley, H.; Thorat, N. Novel Epigenetic Therapeutic Strategies and Targets in Cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2022, 1868, 166552. [CrossRef]

- Lagosz-Cwik, K.B.; Melnykova, M.; Nieboga, E.; Schuster, A.; Bysiek, A.; Dudek, S.; Lipska, W.; Kantorowicz, M.; Tyrakowski, M.; Darczuk, D.; et al. Mapping of DNA Methylation-Sensitive Cellular Processes in Gingival and Periodontal Ligament Fibroblasts in the Context of Periodontal Tissue Homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Nisar, A.; Jagtap, S.; Vyavahare, S.; Deshpande, M.; Harsulkar, A.; Ranjekar, P.; Prakash, O. Phytochemicals in the Treatment of Inflammation-Associated Diseases: The Journey from Preclinical Trials to Clinical Practice. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C.; Ahluwalia, N.; Brouns, F.; Buetler, T.; Clement, K.; Cunningham, K.; Esposito, K.; Jönsson, L.S.; Kolb, H.; Lansink, M.; et al. Dietary Factors and Low-Grade Inflammation in Relation to Overweight and Obesity. Br J Nutr 2011, 106, S1–S78. [CrossRef]

- González-Gallego, J.; García-Mediavilla, M.V.; Sánchez-Campos, S.; Tuñón, M.J. Fruit Polyphenols, Immunity and Inflammation. Br J Nutr 2010, 104, S15–S27. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Md.S.; Wazed, M.A.; Asha, S.; Amin, Md.R.; Shimul, I.M. Dietary Phytochemicals in Health and Disease: Mechanisms, Clinical Evidence, and Applications—A Comprehensive Review. Food Science & Nutrition 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Hasnat, H.; Shompa, S.A.; Islam, Md.M.; Alam, S.; Richi, F.T.; Emon, N.U.; Ashrafi, S.; Ahmed, N.U.; Chowdhury, Md.N.R.; Fatema, N.; et al. Flavonoids: A Treasure House of Prospective Pharmacological Potentials. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27533. [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, M.I.; Sadek, M.A.; Abdou, K.; El-Dessouki, A.M.; El-Shiekh, R.A.; Khalaf, S.S. Orientin: A Comprehensive Review of a Promising Bioactive Flavonoid. Inflammopharmacol 2025, 33, 1713–1728. [CrossRef]

- Caban, M.; Lewandowska, U. Polyphenols and the Potential Mechanisms of Their Therapeutic Benefits against Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Journal of Functional Foods 2022, 95, 105181. [CrossRef]

- Liga, S.; Paul, C.; Péter, F. Flavonoids: Overview of Biosynthesis, Biological Activity, and Current Extraction Techniques. Plants 2023, 12, 2732. [CrossRef]

- Masenga, S.K.; Kabwe, L.S.; Chakulya, M.; Kirabo, A. Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress in Metabolic Syndrome. IJMS 2023, 24, 7898. [CrossRef]

- Rebollo-Hernanz, M.; Zhang, Q.; Aguilera, Y.; Martín-Cabrejas, M.A.; Gonzalez De Mejia, E. Phenolic Compounds from Coffee By-Products Modulate Adipogenesis-Related Inflammation, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Insulin Resistance in Adipocytes, via Insulin/PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathways. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2019, 132, 110672. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Tanaka, Y.; Saitoh, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Miwa, N. Carcinostatic Effects of Platinum Nanocolloid Combined with Gamma Irradiation on Human Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Life Sciences 2015, 127, 106–114. [CrossRef]

- Panieri, E.; Pinho, S.A.; Afonso, G.J.M.; Oliveira, P.J.; Cunha-Oliveira, T.; Saso, L. NRF2 and Mitochondrial Function in Cancer and Cancer Stem Cells. Cells 2022, 11, 2401. [CrossRef]

- Eckschlager, T.; Plch, J.; Stiborova, M.; Hrabeta, J. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors as Anticancer Drugs. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, 1414. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Tapadar, S.; Ruan, Z.; Sun, C.Q.; Arnold, R.S.; Johnston, A.; Olugbami, J.O.; Arunsi, U.; Gaul, D.A.; Petros, J.A.; et al. A Novel Liver Cancer-Selective Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Is Effective Against Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Induces Durable Responses with Immunotherapy 2024.

- Liu, Z.; Huang, M.; Hong, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Shan, S.; Ren, T. Isovalerylspiramycin I Suppresses Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Growth through ROS-Mediated Inhibition of PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 3714–3730. [CrossRef]

- Record, I.R.; Dreosti, I.E.; McInerney, J.K. The Antioxidant Activity of Genistein in Vitro. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 1995, 6, 481–485. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Jung, W.-S.; Kim, M.E.; Lee, H.-W.; Youn, H.-Y.; Seon, J.K.; Lee, H.-N.; Lee, J.S. Genistein Inhibits Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Human Mast Cell Activation through the Inhibition of the ERK Pathway. International Journal of Molecular Medicine 2014, 34, 1669–1674. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.-C. NF-κB Signaling in Inflammation. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2017, 2. [CrossRef]

- Tuli, H.S.; Tuorkey, M.J.; Thakral, F.; Sak, K.; Kumar, M.; Sharma, A.K.; Sharma, U.; Jain, A.; Aggarwal, V.; Bishayee, A. Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Genistein in Cancer: Recent Advances. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Shin, H.S.; Satsu, H.; Totsuka, M.; Shimizu, M. 5-Caffeoylquinic Acid and Caffeic Acid Down-Regulate the Oxidative Stress- and TNF-α-Induced Secretion of Interleukin-8 from Caco-2 Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 3863–3868. [CrossRef]

- Tyszka-Czochara, M.; Bukowska-Strakova, K.; Kocemba-Pilarczyk, K.A.; Majka, M. Caffeic Acid Targets AMPK Signaling and Regulates Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Anaplerosis While Metformin Downregulates HIF-1α-Induced Glycolytic Enzymes in Human Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma Lines. Nutrients 2018, 10, 841. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Zhu, G.; Peng, Q.; Li, X.; Zou, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, L.; Li, X.; Wu, P.; Luo, A.; et al. Natural Products Combating EGFR-TKIs Resistance in Cancer. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry Reports 2025, 13, 100251. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, J. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of p-Coumaric Acid in LPS-Stimulated RAW264.7 Cells: Involvement of NF-κB and MAPKs Pathways. Med chem (Los Angeles) 2016, 06. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Sun, C.; Han, X.; Ye, Y.; Qin, Y.; Liu, S. Sanyin Formula Enhances the Therapeutic Efficacy of Paclitaxel in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Metastases through the JAK/STAT3 Pathway in Mice. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 16, 9. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yue, P.; Dickinson, C.F.; Yang, J.K.; Datanagan, K.; Zhai, N.; Zhang, Y.; Miklossy, G.; Lopez-Tapia, F.; Tius, M.A.; et al. Natural Product Preferentially Targets Redox and Metabolic Adaptations and Aberrantly Active STAT3 to Inhibit Breast Tumor Growth in Vivo. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Bouyahya, A.; El Hachlafi, N.; Aanniz, T.; Bourais, I.; Mechchate, H.; Benali, T.; Shariati, M.A.; Burkov, P.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Wilairatana, P.; et al. Natural Bioactive Compounds Targeting Histone Deacetylases in Human Cancers: Recent Updates. Molecules 2022, 27, 2568. [CrossRef]

- Neelab; Zeb, A.; Jamil, M. Milk Thistle Protects against Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Induced by Dietary Thermally Oxidized Tallow. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31445. [CrossRef]

- Surai, P. Silymarin as a Natural Antioxidant: An Overview of the Current Evidence and Perspectives. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 204–247. [CrossRef]

- Sugihara, A.; Nguyen, L.C.; Shamim, H.M.; Iida, T.; Nakase, M.; Takegawa, K.; Senda, M.; Jida, S.; Ueno, M. Mutation in Fission Yeast Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinase Pik1 Is Synthetically Lethal with Defect in Telomere Protection Protein Pot1. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2018, 496, 1284–1290. [CrossRef]

- Baş, H.; Kalender, Y.; Pandir, D.; Kalender, S. Effects of Lead Nitrate and Sodium Selenite on DNA Damage and Oxidative Stress in Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Rat Erythrocytes and Leucocytes. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 2015, 39, 1019–1026. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Pan, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Qiu, Z.; Jiang, L. Allicin Decreases Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells through Suppression of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Activation of Nrf2. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017, 41, 2255–2267. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.; Ueberham, E.; Gebhardt, R. Influence of Organosulphur Compounds from Garlic on the Secretion of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitor TIMP-1 by Cultured HUVEC Cells. Cell Biol Toxicol 2004, 20, 253–260. [CrossRef]

- Nian, H.; Delage, B.; Pinto, J.T.; Dashwood, R.H. Allyl Mercaptan, a Garlic-Derived Organosulfur Compound, Inhibits Histone Deacetylase and Enhances Sp3 Binding on the P21WAF1 Promoter. Carcinogenesis 2008, 29, 1816–1824. [CrossRef]

- Astrain-Redin, N.; Sanmartin, C.; Sharma, A.K.; Plano, D. From Natural Sources to Synthetic Derivatives: The Allyl Motif as a Powerful Tool for Fragment-Based Design in Cancer Treatment. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 3703–3731. [CrossRef]

- Addi, M.; Elbouzidi, A.; Abid, M.; Tungmunnithum, D.; Elamrani, A.; Hano, C. An Overview of Bioactive Flavonoids from Citrus Fruits. Applied Sciences 2021, 12, 29. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Gu, H.; Ye, Y.; Lin, B.; Sun, L.; Deng, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J. Protective Effects of Hesperidin against Oxidative Stress of Tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide in Human Hepatocytes. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2010, 48, 2980–2987. [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, A.H.; Babiker, A.Y.; Anwar, S. Hesperidin, a Bioflavonoid in Cancer Therapy: A Review for a Mechanism of Action through the Modulation of Cell Signaling Pathways. Molecules 2023, 28, 5152. [CrossRef]

- Tejada, S.; Pinya, S.; Martorell, M.; Capó, X.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A.; Sureda, A. Potential Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Hesperidin from the Genus Citrus. CMC 2019, 25, 4929–4945. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Schluesener, H. Health-Promoting Effects of the Citrus Flavanone Hesperidin. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2017, 57, 613–631. [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Buttari, B.; Panieri, E.; Profumo, E.; Saso, L. An Overview of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway and Its Role in Inflammation. Molecules 2020, 25, 5474. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bedmar, Z.; Anter, J.; Alonso-Moraga, A.; Martín De Las Mulas, J.; Millán-Ruiz, Y.; Guil-Luna, S. Demethylating and Anti-hepatocarcinogenic Potential of Hesperidin, a Natural Polyphenol of Citrus Juices. Molecular Carcinogenesis 2017, 56, 1653–1662. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Xia, T.; Liu, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Sun, C. Remodeling the Epigenetic Landscape of Cancer—Application Potential of Flavonoids in the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R. Genistein. Phytochemistry 2002, 60, 205–211. [CrossRef]

- Setchell, K.D.R.; Cassidy, A. Dietary Isoflavones: Biological Effects and Relevance to Human Health. The Journal of Nutrition 1999, 129, 758S-767S. [CrossRef]

- Goh, Y.X.; Jalil, J.; Lam, K.W.; Husain, K.; Premakumar, C.M. Genistein: A Review on Its Anti-Inflammatory Properties. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Valsecchi, A.E.; Franchi, S.; Panerai, A.E.; Rossi, A.; Sacerdote, P.; Colleoni, M. The Soy Isoflavone Genistein Reverses Oxidative and Inflammatory State, Neuropathic Pain, Neurotrophic and Vasculature Deficits in Diabetes Mouse Model. European Journal of Pharmacology 2011, 650, 694–702. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhao, X.; Hou, C.; Ma, W.; Yu, H.; Xiao, R. Genistein Antagonizes Inflammatory Damage Induced by β-Amyloid Peptide in Microglia through TLR4 and NF-κB. Nutrition 2014, 30, 90–95. [CrossRef]

- Smolińska, E.; Moskot, M.; Jakóbkiewicz-Banecka, J.; Węgrzyn, G.; Banecki, B.; Szczerkowska-Dobosz, A.; Purzycka-Bohdan, D.; Gabig-Cimińska, M. Molecular Action of Isoflavone Genistein in the Human Epithelial Cell Line HaCaT. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192297. [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen, M.; Nieminen, R.; Asmawi, M.; Vuorela, P.; Vapaatalo, H.; Moilanen, E. Effects of Flavonoids on Prostaglandin E2Production and on COX-2 and mPGES-1 Expressions in Activated Macrophages. Planta Med 2011, 77, 1504–1511. [CrossRef]

- Bilir, B.; Sharma, N.V.; Lee, J.; Hammarstrom, B.; Svindland, A.; Kucuk, O.; Moreno, C.S. Effects of Genistein Supplementation on Genome-Wide DNA Methylation and Gene Expression in Patients with Localized Prostate Cancer. International Journal of Oncology 2017, 51, 223–234. [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.-P.; Kim, S.-W.; Ma, S.H.; Park, B.; Ahn, Y.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, M.H.; Kang, E.; Kim, L.S.; Jung, Y.; et al. Dietary Intake and Breast Cancer among Carriers and Noncarriers of BRCA Mutations in the Korean Hereditary Breast Cancer Study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2013, 98, 1493–1501. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Shi, J.-X.; Zhang, D.-M.; Wang, H.-D.; Hang, C.-H.; Chen, H.-L.; Yin, H.-X. Inhibition of Hemolysate-Induced iNOS and COX-2 Expression by Genistein through Suppression of NF-кB Activation in Primary Astrocytes. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2009, 278, 91–95. [CrossRef]

- Habtemariam, S. The Molecular Pharmacology of Phloretin: Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms of Action. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 143. [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Bai, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, M.X. Phloretin Attenuates Inflammation Induced by Subarachnoid Hemorrhage through Regulation of the TLR2/MyD88/NF-kB Pathway. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-W.; Lee, G.; Jo, J.-H.; Yang, Y.; Ahn, J.-H. Biosynthesis of Phloretin and Its C-Glycosides through Stepwise Culture of Escherichia Coli. Appl Biol Chem 2024, 67. [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-T.; Huang, W.-C.; Liou, C.-J. Evaluation of the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Phloretin and Phlorizin in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Mouse Macrophages. Food Chemistry 2012, 134, 972–979. [CrossRef]

- Mansuri, M.L.; Parihar, P.; Solanki, I.; Parihar, M.S. Flavonoids in Modulation of Cell Survival Signalling Pathways. Genes Nutr 2014, 9. [CrossRef]

- Bin-Jumah, M.N.; Nadeem, M.S.; Gilani, S.J.; Mubeen, B.; Ullah, I.; Alzarea, S.I.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Alshehri, S.; Al-Abbasi, F.A.; Kazmi, I. Lycopene: A Natural Arsenal in the War against Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 232. [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Ghorat, F.; Ul-Haq, I.; Ur-Rehman, H.; Aslam, F.; Heydari, M.; Shariati, M.A.; Okuskhanova, E.; Yessimbekov, Z.; Thiruvengadam, M.; et al. Lycopene as a Natural Antioxidant Used to Prevent Human Health Disorders. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 706. [CrossRef]

- Kulawik, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Czerny, B.; Kamiński, A.; Zalewski, P. The Relationship Between Lycopene and Metabolic Diseases. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3708. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Ahmed, S.; Elasbali, A.M.; Adnan, M.; Alam, S.; Hassan, Md.I.; Pasupuleti, V.R. Therapeutic Implications of Caffeic Acid in Cancer and Neurological Diseases. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Birková, A. Caffeic Acid: A Brief Overview of Its Presence, Metabolism, and Bioactivity. Bioactive Compounds in Health and Disease 2020, 3, 74. [CrossRef]

- Pavlíková, N. Caffeic Acid and Diseases—Mechanisms of Action. IJMS 2022, 24, 588. [CrossRef]

- Ku, H.-C.; Lee, S.-Y.; Yang, K.-C.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Su, M.-J. Modification of Caffeic Acid with Pyrrolidine Enhances Antioxidant Ability by Activating AKT/HO-1 Pathway in Heart. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148545. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Liu, Y.; Lin, H.; Shao, C.; Jin, X.; Peng, T.; Liu, Y. Caffeic Acid Activates Nrf2 Enzymes, Providing Protection against Oxidative Damage Induced by Ionizing Radiation. Brain Research Bulletin 2025, 224, 111325. [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, D.; Zieliński, H.; Laparra-Llopis, J.M.; Szawara-Nowak, D.; Honke, J.; Giménez-Bastida, J.A. Caffeic Acid Modulates Processes Associated with Intestinal Inflammation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 554. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Q. Caffeic Acid Hinders the Proliferation and Migration through Inhibition of IL-6 Mediated JAK-STAT-3 Signaling Axis in Human Prostate Cancer. OR 2024, 32, 1881–1890. [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.-M.; Kim, I.-T.; Park, Y.-M.; Ha, J.; Choi, J.-W.; Park, H.-J.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, K.-T. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Caffeic Acid Methyl Ester and Its Mode of Action through the Inhibition of Prostaglandin E2, Nitric Oxide and Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Production. Biochemical Pharmacology 2004, 68, 2327–2336. [CrossRef]

- Cortez, N.; Villegas, C.; Burgos, V.; Cabrera-Pardo, J.R.; Ortiz, L.; González-Chavarría, I.; Nchiozem-Ngnitedem, V.-A.; Paz, C. Adjuvant Properties of Caffeic Acid in Cancer Treatment. IJMS 2024, 25, 7631. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-Y.; Yasir, M.; Lee, H.; Han, E.-T.; Han, J.-H.; Park, W.; Kwon, Y.-S.; Chun, W. Caffeic Acid Methyl Ester Inhibits LPS-induced Inflammatory Response through Nrf2 Activation and NF-κB Inhibition in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Exp Ther Med 2023, 26. [CrossRef]

- Wan, F.; Zhong, R.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yi, B.; Hou, F.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, L.; et al. Caffeic Acid Supplement Alleviates Colonic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Potentially Through Improved Gut Microbiota Community in Mice. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Xu, Y.-M.; Lau, A.T.Y. The Epigenetic Effects of Coffee. Molecules 2023, 28, 1770. [CrossRef]

- Contardi, M.; Lenzuni, M.; Fiorentini, F.; Summa, M.; Bertorelli, R.; Suarato, G.; Athanassiou, A. Hydroxycinnamic Acids and Derivatives Formulations for Skin Damages and Disorders: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 999. [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Zhang, B.; Duan, W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M. Nutrients and Bioactive Components from Vinegar: A Fermented and Functional Food. Journal of Functional Foods 2020, 64, 103681. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.H.; Yang, H.J.; Li, W.; Oh, Y.-C.; Choi, J.-G. Immune-Enhancing Effects of Gwakhyangjeonggi-San in RAW 264.7 Macrophage Cells through the MAPK/NF-κB Signaling Pathways. IJMS 2024, 25, 9246. [CrossRef]

- Moustardas, P.; Aberdam, D.; Lagali, N. MAPK Pathways in Ocular Pathophysiology: Potential Therapeutic Drugs and Challenges. Cells 2023, 12, 617. [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.-R.; Yun, J.-M. P-Coumaric Acid Modulates Cholesterol Efflux and Lipid Accumulation and Inflammation in Foam Cells. Nutr Res Pract 2024, 18, 774. [CrossRef]

- Medeiros-Linard, C.F.B.; Andrade-da-Costa, B.L.D.S.; Augusto, R.L.; Sereniki, A.; Trevisan, M.T.S.; Perreira, R.D.C.R.; De Souza, F.T.C.; Braz, G.R.F.; Lagranha, C.J.; De Souza, I.A.; et al. Anacardic Acids from Cashew Nuts Prevent Behavioral Changes and Oxidative Stress Induced by Rotenone in a Rat Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurotox Res 2018, 34, 250–262. [CrossRef]

- Augusto, R.L.; Mendonça, I.P.; De Albuquerque Rego, G.N.; Pereira, D.D.; Da Penha Gonçalves, L.V.; Dos Santos, M.L.; De Souza, R.F.; Moreno, G.M.M.; Cardoso, P.R.G.; De Souza Andrade, D.; et al. Purified Anacardic Acids Exert Multiple Neuroprotective Effects in Pesticide Model of Parkinson’s Disease: In Vivo and in Silico Analysis. IUBMB Life 2020, 72, 1765–1779. [CrossRef]

- Tomasiak, P.; Janisiak, J.; Rogińska, D.; Perużyńska, M.; Machaliński, B.; Tarnowski, M. Garcinol and Anacardic Acid, Natural Inhibitors of Histone Acetyltransferases, Inhibit Rhabdomyosarcoma Growth and Proliferation. Molecules 2023, 28, 5292. [CrossRef]

- Rais, N.; Ved, A.; Ahmad, R.; Kumar, M.; Deepak Barbhai, M.; Radha; Chandran, D.; Dey, A.; Dhumal, S.; Senapathy, M.; et al. S-Allyl-L-Cysteine — A Garlic Bioactive: Physicochemical Nature, Mechanism, Pharmacokinetics, and Health Promoting Activities. Journal of Functional Foods 2023, 107, 105657. [CrossRef]

- Arreola, R.; Quintero-Fabián, S.; López-Roa, R.I.; Flores-Gutiérrez, E.O.; Reyes-Grajeda, J.P.; Carrera-Quintanar, L.; Ortuño-Sahagún, D. Immunomodulation and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Garlic Compounds. Journal of Immunology Research 2015, 2015, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Sasi, M.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, M.; Thapa, S.; Prajapati, U.; Tak, Y.; Changan, S.; Saurabh, V.; Kumari, S.; Kumar, A.; et al. Garlic (Allium Sativum L.) Bioactives and Its Role in Alleviating Oral Pathologies. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1847. [CrossRef]

- Ansary, J.; Forbes-Hernández, T.Y.; Gil, E.; Cianciosi, D.; Zhang, J.; Elexpuru-Zabaleta, M.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Potential Health Benefit of Garlic Based on Human Intervention Studies: A Brief Overview. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 619. [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, K.; Pahwa, R.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, P.C.; Singh, G.; Verma, R.; Mittal, V.; Singh, I.; Kaushik, D.; et al. Mechanistic Insights into the Pharmacological Significance of Silymarin. Molecules 2022, 27, 5327. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Mendoza, N. Hepatoprotective Effect of Silymarin. WJH 2014, 6, 144. [CrossRef]

- Lovelace, E.S.; Wagoner, J.; MacDonald, J.; Bammler, T.; Bruckner, J.; Brownell, J.; Beyer, R.P.; Zink, E.M.; Kim, Y.-M.; Kyle, J.E.; et al. Silymarin Suppresses Cellular Inflammation By Inducing Reparative Stress Signaling. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 1990–2000. [CrossRef]

- Chittezhath, M.; Deep, G.; Singh, R.P.; Agarwal, C.; Agarwal, R. Silibinin Inhibits Cytokine-Induced Signaling Cascades and down-Regulates Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase in Human Lung Carcinoma A549 Cells. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2008, 7, 1817–1826. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Gong, T.; Liu, Z.; Yang, W.; Xiong, Y.; Xiao, D.; Cifuentes, A.; Ibáñez, E.; Lu, W. The Clinical Anti-Inflammatory Effects and Underlying Mechanisms of Silymarin. iScience 2024, 27, 111109. [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Schwartz, B. The Effect of Bioactive Aliment Compounds and Micronutrients on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 903. [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, M.M.; Motamed, N.; Ranji, N.; Majidi, M.; Falahi, F. Silibinin-Induced Apoptosis and Downregulation of MicroRNA-21 and MicroRNA-155 in MCF-7 Human Breast Cancer Cells. J Breast Cancer 2016, 19, 45. [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Shah, I.; Ali, N.; Adhikari, A.; Tahir, M.N.; Shah, S.W.A.; Ishtiaq, S.; Khan, J.; Khan, S.; Umer, M.N. Sesquiterpene Lactone! A Promising Antioxidant, Anticancer and Moderate Antinociceptive Agent from Artemisia Macrocephala Jacquem. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017, 17. [CrossRef]

- Taleghani, A.; Emami, S.A.; Tayarani-Najaran, Z. Artemisia: A Promising Plant for the Treatment of Cancer. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 28, 115180. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yi, H.; Yao, H.; Lu, L.; He, G.; Wu, M.; Zheng, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, L.; et al. Artemisinin Derivatives Inhibit Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells Through Induction of ROS-Dependent Apoptosis/Ferroptosis. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 4075–4085. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, B.; Wang, Q.; Kuang, H. Artesunate Exerts Organ- and Tissue-Protective Effects by Regulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Autophagy, Apoptosis, and Fibrosis: A Review of Evidence and Mechanisms. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 686. [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Santos, A.R.D.O.D.; Carvalho, A.C.A.D.; Bechara, M.D.; Guiguer, E.L.; Goulart, R.D.A.; Vargas Sinatora, R.; Araújo, A.C.; Barbalho, S.M. Phytochemicals and Regulation of NF-kB in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Overview of In Vitro and In Vivo Effects. Metabolites 2023, 13, 96. [CrossRef]

- Efferth, T.; Oesch, F. The Immunosuppressive Activity of Artemisinin-type Drugs towards Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases. Medicinal Research Reviews 2021, 41, 3023–3061. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Woon, C.Y.-N.; Liu, C.-G.; Cheng, J.-T.; You, M.; Sethi, G.; Wong, A.L.-A.; Ho, P.C.-L.; Zhang, D.; Ong, P.; et al. Repurposing Artemisinin and Its Derivatives as Anticancer Drugs: A Chance or Challenge? Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Sagar, S.M.; Yance, D.; Wong, R.K. Natural Health Products That Inhibit Angiogenesis: A Potential Source for Investigational New Agents to Treat Cancer—Part 1. Current Oncology 2006, 13, 14–26. [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, S.T.B.; Fatima, H.; Naz, I.; Kanwal, N.; Haq, I. Pre-Clinical Studies Comparing the Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Artemisinic Compounds by Targeting NFκB/TNF-α/NLRP3 and Nrf2/TRX Pathways in Balb/C Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.D.S.E.; Marques, J.N.D.J.; Linhares, E.P.M.; Bonora, C.M.; Costa, É.T.; Saraiva, M.F. Review of Anticancer Activity of Monoterpenoids: Geraniol, Nerol, Geranial and Neral. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2022, 362, 109994. [CrossRef]

- Ben Ammar, R.; Mohamed, M.E.; Alfwuaires, M.; Abdulaziz Alamer, S.; Bani Ismail, M.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Sekar, A.K.; Ksouri, R.; Rajendran, P. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Geraniol Isolated from Lemon Grass on Ox-LDL-Stimulated Endothelial Cells by Upregulation of Heme Oxygenase-1 via PI3K/Akt and Nrf-2 Signaling Pathways. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4817. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Li, S.; Nilkhet, S.; Baek, S.J. Anti-Cancer Activity of Rose-Geranium Essential Oil and Its Bioactive Compound Geraniol in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Appl Biol Chem 2025, 68. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Dashwood, R.H. Epigenetic Regulation of NRF2/KEAP1 by Phytochemicals. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 865. [CrossRef]

- Nurkolis, F.; Taslim, N.A.; Syahputra, R.A.; Annette d’Arqom; Tjandrawinata, R.R.; Purba, A.K.R.; Mustika, A. Food Phytochemicals as Epigenetic Modulators in Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2025, 21, 101873. [CrossRef]

- Gowd, V.; Kanika; Jori, C.; Chaudhary, A.A.; Rudayni, H.A.; Rashid, S.; Khan, R. Resveratrol and Resveratrol Nano-Delivery Systems in the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2022, 109, 109101. [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L. Mechanism of Antioxidant Properties of Quercetin and Quercetin-DNA Complex. J Mol Model 2020, 26. [CrossRef]

- Olasehinde, T.A.; Olaokun, O.O. Apigenin and Inflammation in the Brain: Can Apigenin Inhibit Neuroinflammation in Preclinical Models? Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32, 3099–3108. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.; Cidade, H.; Pinto, M.; Tiritan, M.E. Chiral Flavonoids as Antitumor Agents. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14, 1267. [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Jiang, W.; Jia, H.; Lei, M. Synergistically Anti-Multiple Myeloma Effects: Flavonoid, Non-Flavonoid Polyphenols, and Bortezomib. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1647. [CrossRef]

- Iordache, M.P.; Buliman, A.; Costea-Firan, C.; Gligore, T.C.I.; Cazacu, I.S.; Stoian, M.; Teoibaș-Şerban, D.; Blendea, C.-D.; Protosevici, M.G.-I.; Tanase, C.; et al. Immunological and Inflammatory Biomarkers in the Prognosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Ischemic Stroke: A Review of a Decade of Advancement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7928. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).