Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

01 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

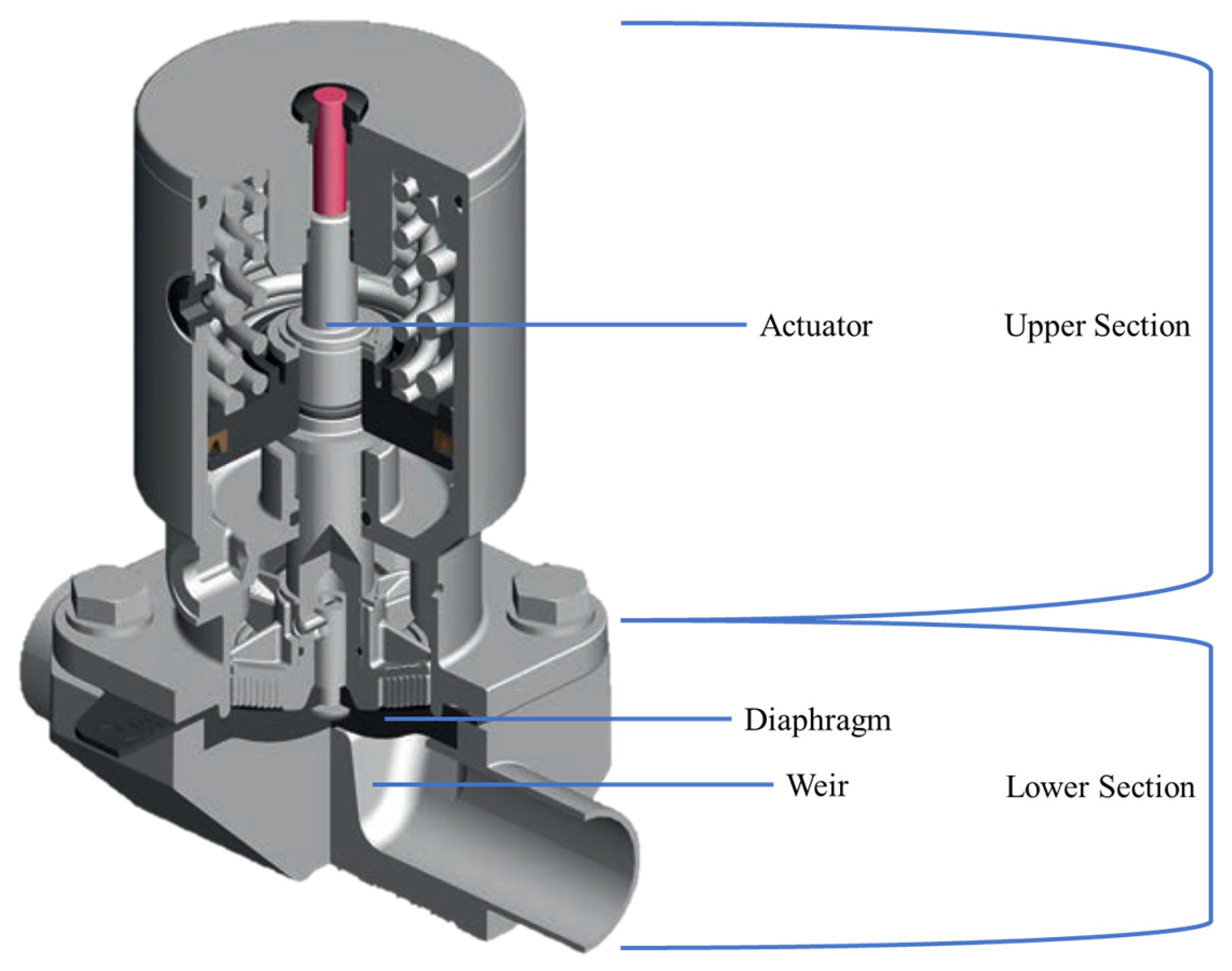

Diaphragm Valves

2. Related Work

2.1. Photometric Stereo with Multiple Lighting

2.2. Visual Inspection Methods for Industrial Surfaces

2.3. Optical Inspection of Rubber and Elastomer Surfaces

2.4. Characterization of EPDM and Detection of Visual Damage

3. Materials and Methods

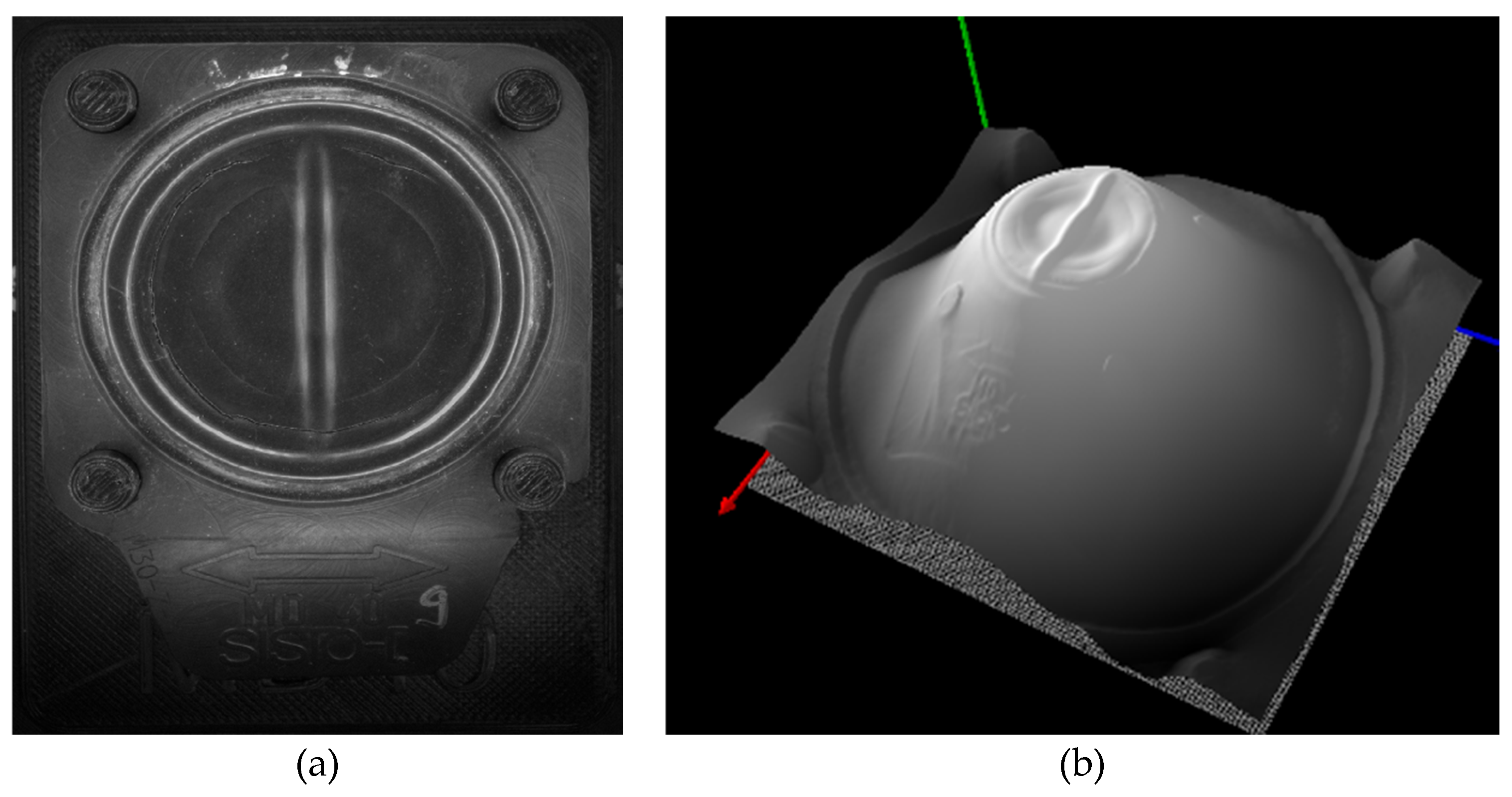

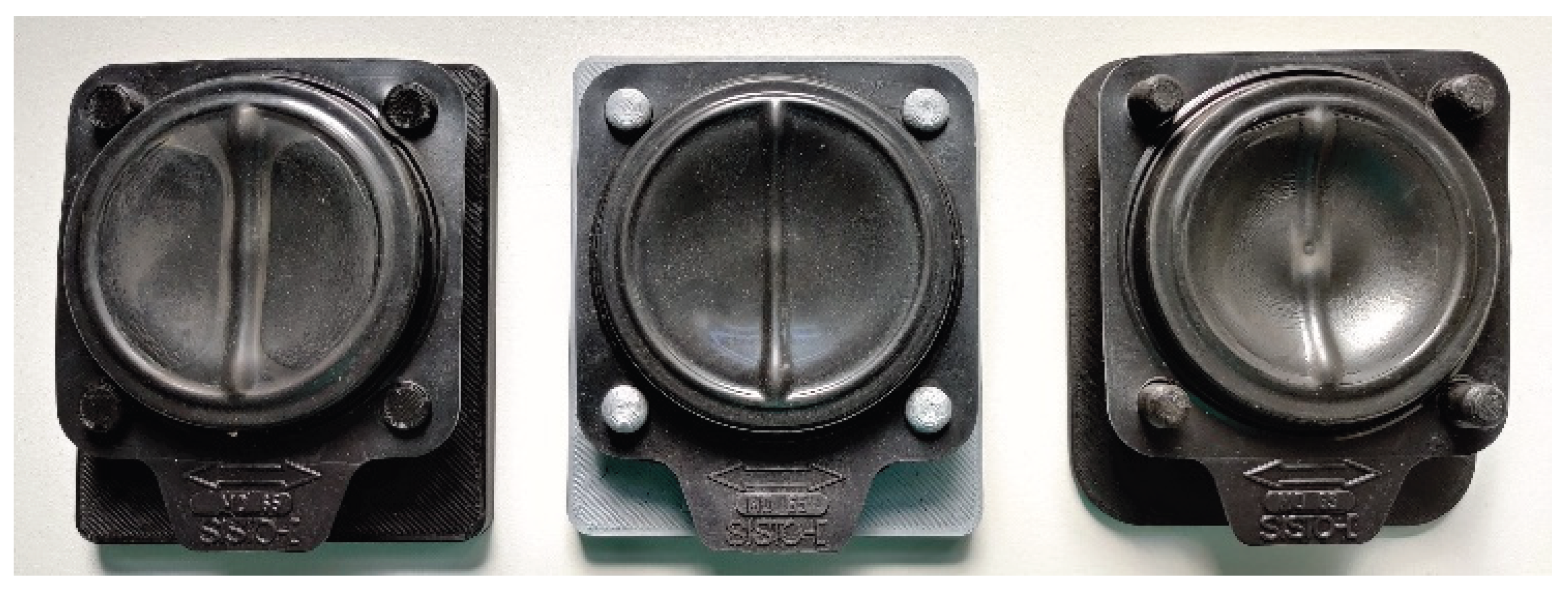

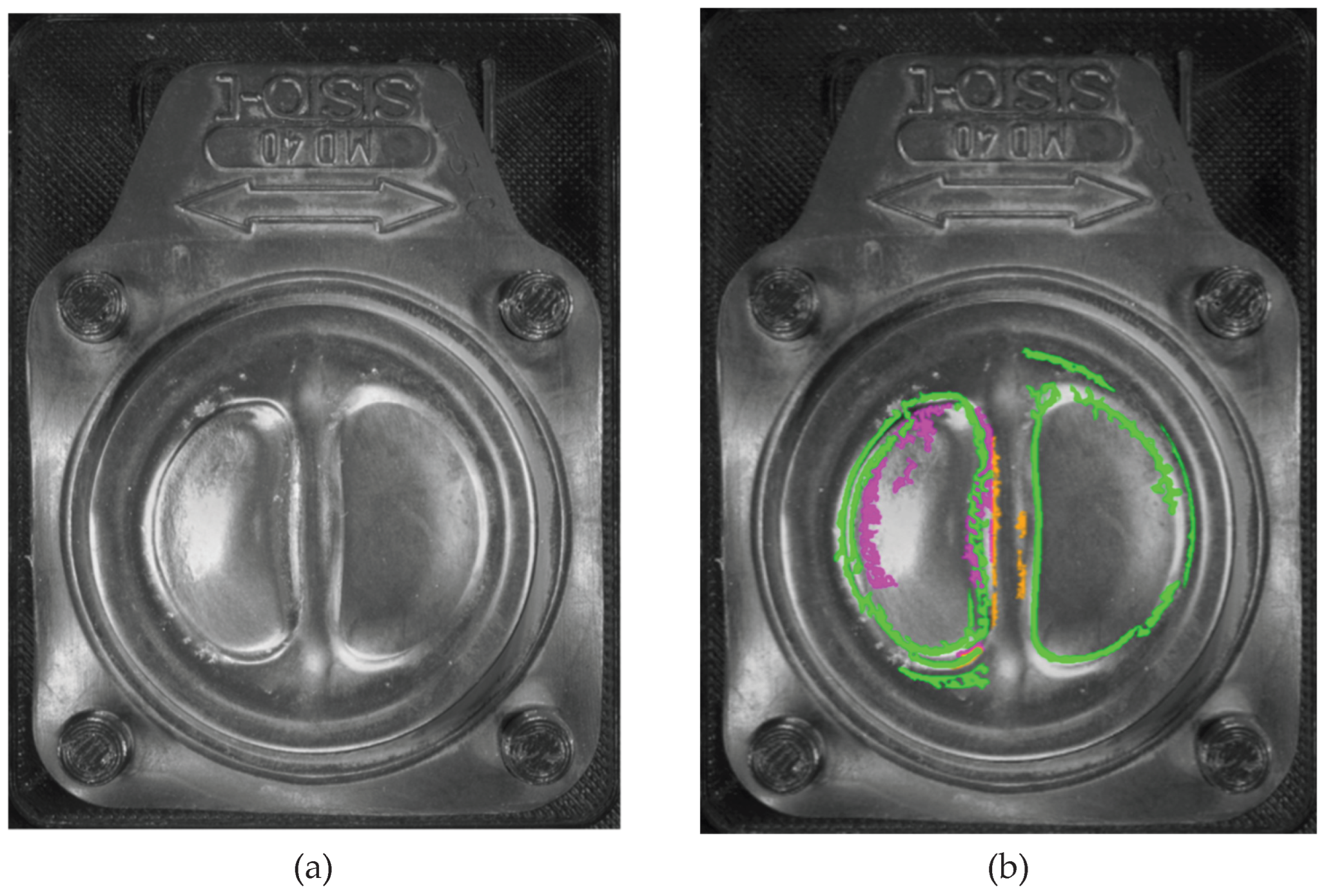

3.1. Object of Investigation: The Elastomer Diaphragm

3.2. Defect Classes

Cracks

Wrinkles

Kidneys

Permanent Deformations

3.3. Hardware Setup

3.3.1. Rationale: Why Four-Image PS Instead of Single-View 2D

3.3.2. Imaging System

- Camera: Basler acA2440-35uc, mounted normal to the diaphragm surface. Images were acquired at 2448 × 2048 px.

- Illumination: Four-segment ring light Falcon Illumination FLDR-i170-LA3-4 operated in darkfield geometry. Each acquisition cycle recorded four frames, each with exactly one active segment (45°, 135°, 225°, 315°). The segments are identical in type and nominal intensity and share a fixed elevation angle relative to the sample plane.

- Field of view and part sizes: The mechanical layout accommodates diaphragms from Ø 30 mm to Ø 92 mm without changing the camera pose.

- Sample fixturing: Dedicated diaphragm holders centered each diaphragm under the camera and placed it in a reproducible focal plane. This minimizes the focus drift and perspective variability between parts and reduces the need for geometric post-alignment.

3.3.3. Illumination Evaluation and Final Choice

3.3.4. Acquisition Protocol and Control

3.3.5. Geometric and Mechanical Considerations

3.3.6. Practical Limitations

3.4. Algorithm/Execution

Photometric Stereo (PS) According to Woodham

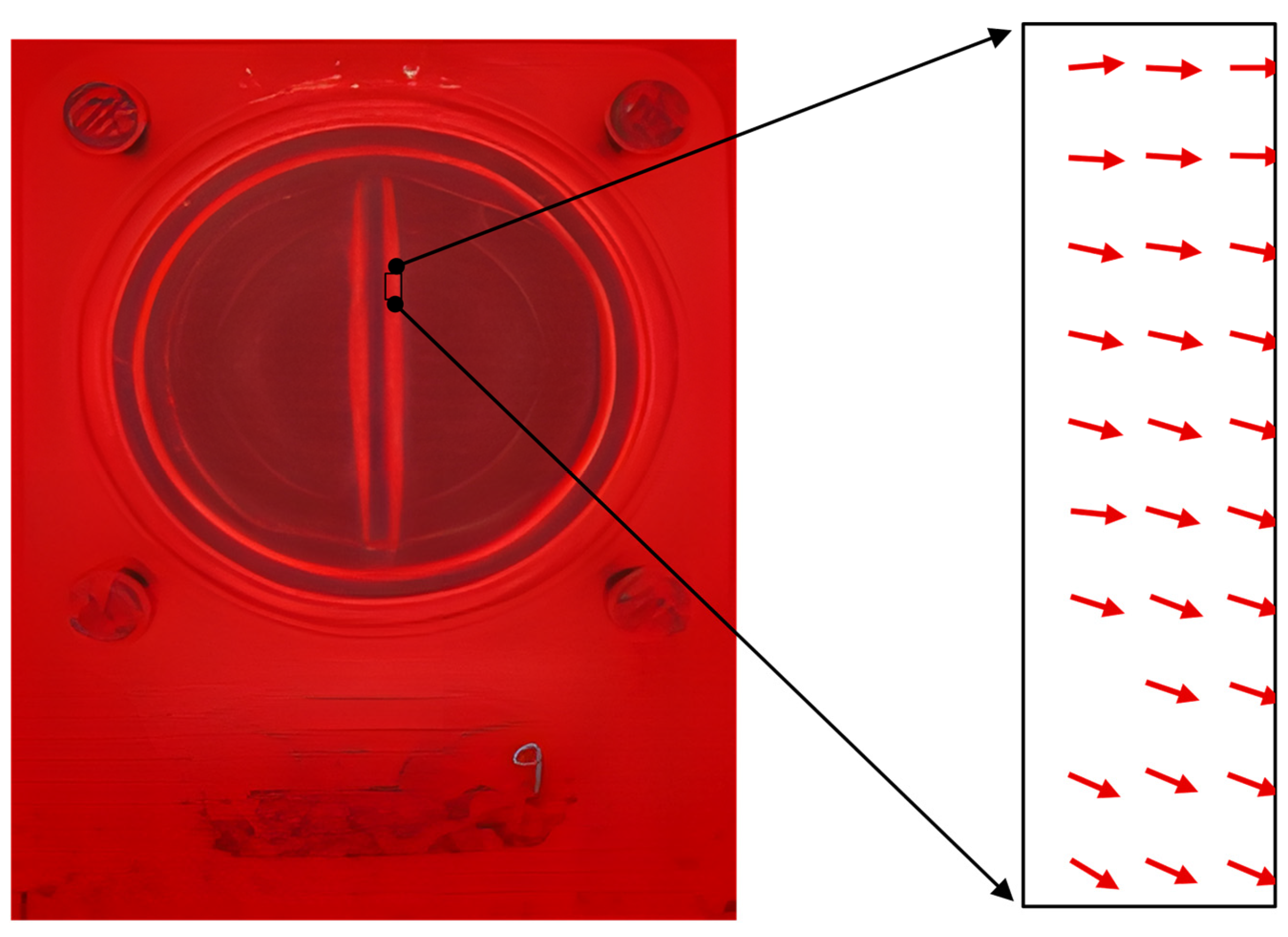

- albedo image: A two-dimensional (2D) representation of the diaphragm surface, known as the albedo image, was created. This image displays the reflection characteristics of the diaphragm and provides detailed information on how the surface reflects light. It also indicates local light absorption properties without the presence of shadows, thus offering a clear and unobstructed view of the diaphragm material properties and surface features.

- gradient image: This image captures the three-dimensional form of the diaphragm by calculating the local gradients across its surface, which are then stored within the gradient image. Although it is more challenging to interpret, at first glance, compared with the albedo image, the gradient image is crucial for generating other valuable results used in the damage recognition process. One such result is the height map, detailed below. The gradient image serves as an essential intermediary, facilitating the accurate depiction and analysis of the topography of the diaphragm.

- height map: By integrating the gradients captured in the gradient image, a height map is generated. In this image, each pixel value represents the relative height along the z-axis of the diaphragm’s three-dimensional surface. This precise depiction of surface elevations and depressions is crucial for identifying and evaluating damage patterns and offers a detailed view of the diaphragm’s topography.

Execution

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.2. Quantitative Results

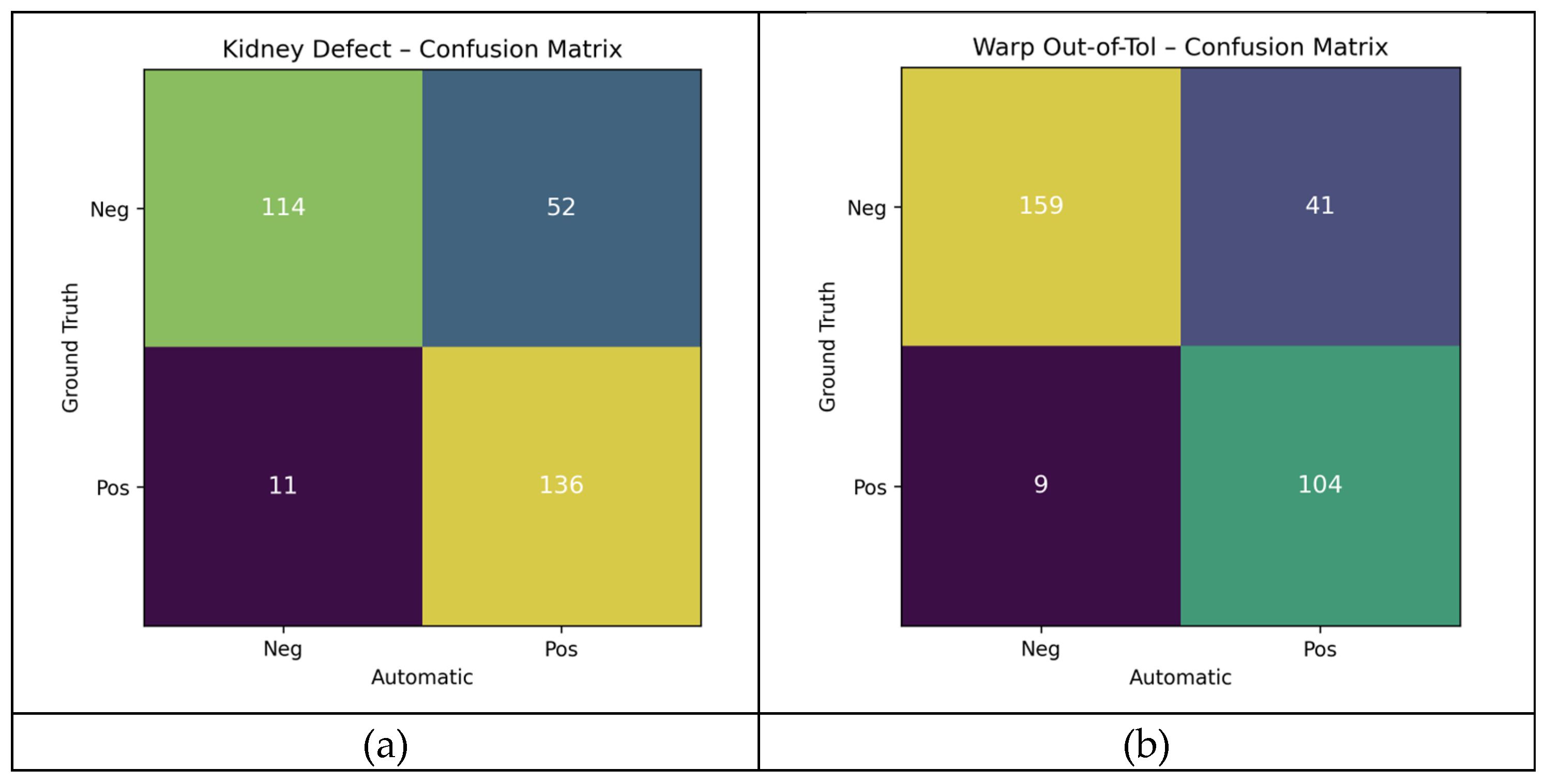

Geometric Deformations (Kidney and Warp)

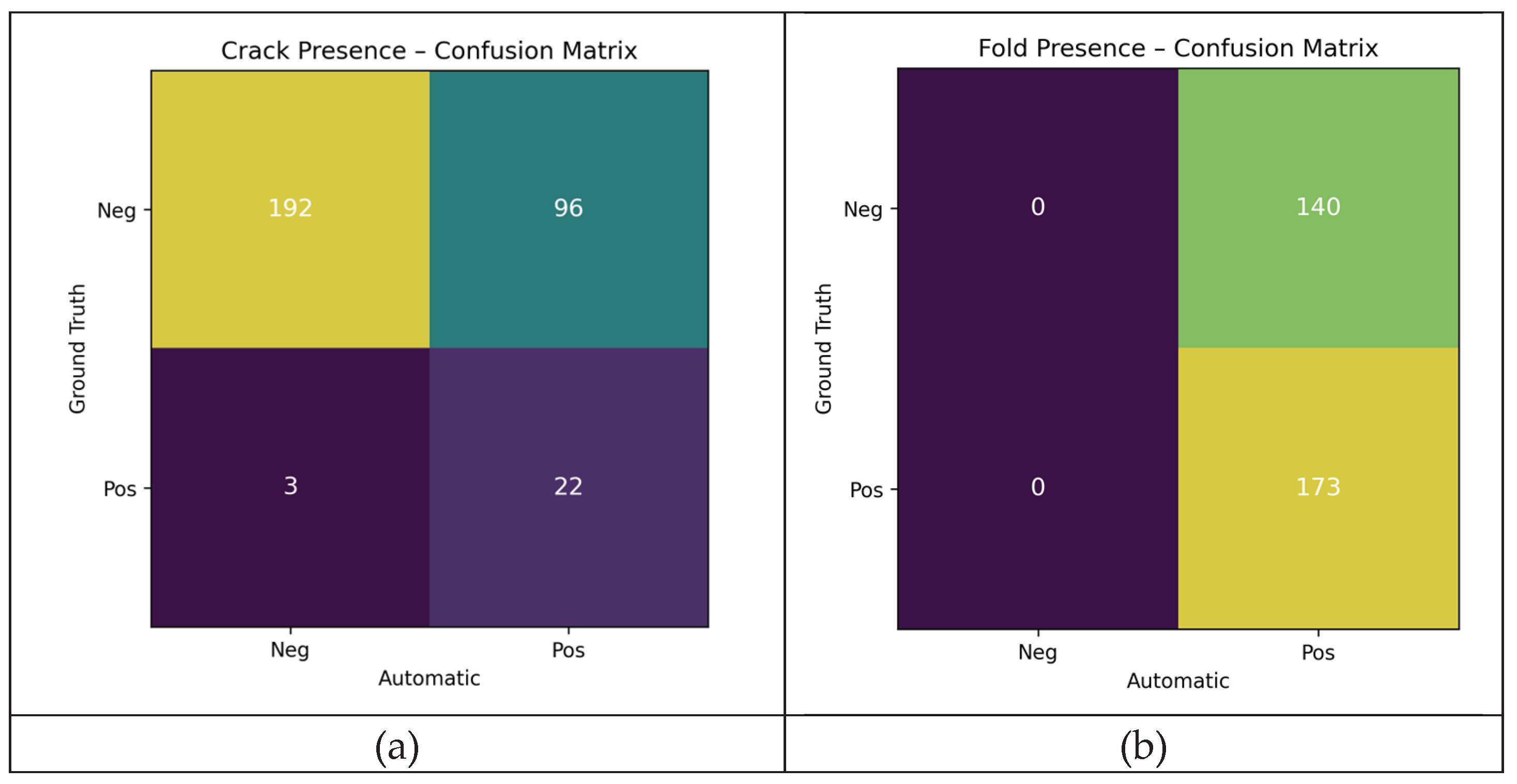

Surface Texture Anomalies (Cracks and Wrinkles)

4.3. Error Analysis

4.3.1. Industrial Reliability Requirements

4.3.2. Wrinkle Detection Sensitivity

4.3.3. Crack-Wrinkle Discrimination Challenge

- Optical Signature Convergence: Both the cracks and wrinkles generated similar gradient patterns in the captured images. While genuine cracks typically exhibit sharp-edged polarization changes at the fracture lips, wrinkles produce comparable gradient signatures without distinctive polarization characteristics. The current RGB-based acquisition method cannot distinguish between these polarization differences. This is precisely why the next iteration of this system will use a polarisation-based camera. Since crack edges and wrinkles reflect polarized light differently, we expect a significant improvement in selectivity that directly addresses this core problem.”

- Variable Reflective Properties: The reflective characteristics of wrinkles vary significantly depending on the surface orientation, material stress, and local geometry. This variability causes certain wrinkle formations to exhibit optical signatures that are nearly indistinguishable from genuine cracks, leading to a systematic misclassification. Although most wrinkles remain detectable through the PS approach, the overlapping reflective properties create ambiguous cases that challenge both algorithmic and human classification.

- Height map Resolution Limitations: The Photometric Stereo reconstruction process applies regularization that smooths micro-surface irregularities. This regularization has contrasting effects on the two defect types: fine cracks become artificially widened in the height map representation, whereas deep wrinkles are underestimated as their true depth falls within the regularization noise floor. Consequently, both defect types converge toward similar height map signatures, complicating the algorithmic discrimination.

- Scale-Dependent Detection Challenges: Very small cracks, particularly those less than 1mm in length, present additional complexity for current imaging resolution and analysis algorithms. Although such micro-cracks are detectable under certain favorable conditions, consistent identification across varying diaphragm surface conditions, lighting angles, and material states requires further algorithmic refinement. The variable success rate for sub-millimeter crack detection contributes to the overall precision limitations observed in the crack classification results.

- Traceability and Consistency Issues: The overlapping characteristics between cracks and wrinkles, combined with their scale-dependent visibility, create challenges in maintaining consistent detection criteria across the entire dataset. This variability in detection consistency partially explains the systematic error patterns revealed by the McNemar test results, in which certain surface features are consistently misinterpreted due to their ambiguous optical and geometric signatures.

4.3.4. Systematic Error Patterns

4.3.5. Implications for Industrial Deployment

5. Discussion

Areas for Improvement

Performance and Optimization

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, Q.; Shanben, C.; Tao, L. Inspection of weld shape based on the shape from shading. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2006, 27, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tsai, P.-S.; Cryer, J.E.; Shah, M. Shape-from-shading: a survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Machine Intell. 1999, 21, 690–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodham, R.J. A Cooperative Algorithm for Determining Surface Orientation from a Single View. In Proceedings of the 5th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Cambridge, MA, USA, August 22-25, 1977; Raj, Reddy, Ed.; William Kaufmann, 1977; pp. 635–641. [Google Scholar]

- Landmann, M.; Heist, S.; Dietrich, P.; Speck, H.; Kühmstedt, P.; Tünnermann, A.; Notni, G. 3D shape measurement of objects with uncooperative surface by projection of aperiodic thermal patterns in simulation and experiment. Opt. Eng. 2020, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamet, F.; Cakar, S.; Kotan, M. Automatic Detection and Classification of Defective Areas on Metal Parts by Using Adaptive Fusion of Faster R-CNN and Shape From Shading. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 126030–126038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, X.; Yan, N.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, x. A Novel Image Registration-Based Dynamic Photometric Stereo Method for Online Defect Detection in Aluminum Alloy Castings. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, T.; Zhou, J. Adaptive Weighted Data Fusion for Line Structured Light and Photometric Stereo Measurement System. Sensors (Basel) 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.M.; Malhan, R.K.; Rajendran, P.; Shah, B.C.; Thakar, S.; Yoon, Y.J.; Gupta, S.K. Image-Based Surface Defect Detection Using Deep Learning: A Review. Journal of Computing and Information Science in Engineering 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Au, S.; Luo, S.; Yue, C. Automated Defect Inspection Systems by Pattern Recognition. International Journal of Signal Processing, Image Processing and Pattern Recognition 2009, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Srividhya, R.; Shanmugapriya, K.; Sindhu Priya, K. Automatic Detection of Surface Defects in Industrial Materials Based on Image Processing. IJET 2018, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Fukui, A. Defect Detection for Forged Metal Parts by Image Processing. IJFCC 2020, 9, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, X.V.; Wang, L.; Gao, L. A Review on Recent Advances in Vision-based Defect Recognition towards Industrial Intelligence. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2022, 62, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Q.; Hu, H.; Ahmad, A.; Wang, K. A Review of Metal Surface Defect Detection Technologies in Industrial Applications. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 48380–48400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Fang, F.; Yan, N.; Wu, Y. State of the Art in Defect Detection Based on Machine Vision. Int. J. of Precis. Eng. and Manuf.-Green Tech. 2022, 9, 661–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, M.; Liu, N.; Zhao, B.; Sun, H. Self-Supervised Learning for Industrial Image Anomaly Detection by Simulating Anomalous Samples. Int J Comput Intell Syst 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xie, G.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Wang, C.; Zheng, F.; Jin, Y. Deep Industrial Image Anomaly Detection: A Survey. Mach. Intell. Res. 2024, 21, 104–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, T.; Yang, C.; Cao, Y.; Xie, L.; Tian, H.; Li, X. Review of Wafer Surface Defect Detection Methods. Electronics 2023, 12, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Jiang, K.; Shi, H.; Yu, Y.; Hao, N. Application of Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network for Damage Detection of Conveyor Belt. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 7282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-C.; Su, E.; Li, P.-C.; Bolger, M.J.; Pan, H.-N. Machine Vision and Deep Learning Based Rubber Gasket Defect Detection. Adv. technol. innov. 2020, 5, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-H.; Nguyen, H.-L.; Bui, N.-T.; Bui, T.-H.; Vu, V.-B.; Duong, H.-N.; Hoang, H.-H. Vision-Based System for Black Rubber Roller Surface Inspection. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 8999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar Bharathi, S.; Radhakrishnan, N.; Priya, L. Surface Defect Detection of Rubber Oil Seals Based on Texture Analysis. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Signal and Image Processing 2012 (ICSIP 2012); Kumar, S.S., Ed.; Springer India: India, 2013; pp. 207–216. ISBN 978-81-322-0999-7. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, F.; Ren, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, T. Rubber hose surface defect detection system based on machine vision. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, F.; Liu, H.; Liu, H. Rolling Surface Defect Inspection for Drum-Shaped Rollers Based on Deep Learning. IEEE Sensors J. 2022, 22, 8693–8700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Tu, H.; Xin, Z.; Xu, H. Automatic recognition for cracks in aging rubber materials. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2025, 2961, 12002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.-M.; Markoni, H.; Lee, J.-D. BARNet: Boundary Aware Refinement Network for Crack Detection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 2022, 23, 7343–7358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Su, L.; Zhang, G. A Novel Detection Method for Pavement Crack with Encoder-Decoder Architecture. Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2023, 137, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Wang, K.C.P.; Fei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Yang, G.; Li, J.Q.; Yang, E.; Qiu, S. Automated Pixel-Level Pavement Crack Detection on 3D Asphalt Surfaces with a Recurrent Neural Network. Computer aided Civil Eng 2019, 34, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, W.; Burge, M.J. Digital Image Processing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; ISBN 978-3-031-05743-4. [Google Scholar]

| Mode | Strengths | Limitations on used diaphragms | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dome (diffuse) | Uniform shading; low specular glare | Flattens shape cues; weak sensitivity to shallow height changes; kidneys less pronounced | Good for near-flat parts; insufficient on warped parts |

| Coaxial (telecentric gloss rejection) | Enhances small albedo contrast; simple setup | Sensitive to tilt/warp; highlights move with curvature; crack cues unstable | Acceptable on flat samples; unstable with warping |

| Darkfield (segmented) | Emphasizes slopes/edges; robust shape cues; segments enable SFS | Requires careful geometry; segment balance critical | Selected: best trade-off and PS-compatible |

| Type of Defect | TN | FP | FN | TP | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 | Specificity | McNemar_p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney Defect | 114 | 52 | 11 | 136 | 0.799 | 0.723 | 0.925 | 0.812 | 0.687 | 4.67E-07 |

| Warp Out-of-Tol | 159 | 41 | 9 | 104 | 0.840 | 0.717 | 0.920 | 0.806 | 0.795 | 1.16E-05 |

| Crack Presence | 192 | 96 | 3 | 22 | 0.684 | 0.186 | 0.880 | 0.308 | 0.667 | 2.32E-20 |

| Wrinkle Presence | 0 | 140 | 0 | 173 | 0.553 | 0.553 | 1.000 | 0.712 | 0.000 | 7.26E-32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).