1. Introduction

The rapid progress of generative AI and large language models (LLMs) has redefined machine intelligence benchmarks, producing outputs often indistinguishable from those of humans. Transformer architectures and retrieval-augmented pipelines now provide contextual awareness and access to vast information sources, giving experts tools no single individual could fully master [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Yet, despite their utility, these systems remain fundamentally constrained: they operate through statistical correlations, lack persistent memory, and are guided by no intrinsic purpose or ethical framework [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. As a result, they cannot autonomously distinguish truth from falsehood, meaning from noise, or align their operations with system-level goals.

Agentic AI frameworks attempt to overcome these limits by wrapping LLMs with memory, planning, and feedback loops, enabling them to execute multi-step tasks [

11,

12]. While this increases utility, fragility persists. As the number of interacting agents grows, so does the risk of misalignment, error cascades, and uncontrolled feedback [

13]. The central question remains unresolved: who supervises and governs these agents? Without intrinsic oversight, agentic AI risks presenting the appearance of autonomy while depending heavily on human managers or orchestration software.

Biological systems suggest a different path. A multicellular organism is itself a society of agents—cells—that achieve coherent function through communication, feedback loops, and genomic instructions that encode shared purposes such as survival and reproduction. This intrinsic teleonomy prevents chaos and sustains resilience [

14,

15,

16]. For AI, the analogy is clear: a swarm of software agents is insufficient without system-wide memory, goals, and self-regulation. Intelligent machines, like biological systems, require a persistent blueprint to align local actions with global purpose.

Theoretical work in information science and computation provides foundations for such a blueprint. Burgin’s General Theory of Information (GTI) expands information beyond Shannon’s syntactic model to include both ontological (structural) and epistemic (knowledge-producing) aspects [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Building on GTI, the Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT) identifies a key limitation of the Turing paradigm—the separation of the computer from the computed [

23,

24]. BMT proposes structural machines, uniting runtime execution with knowledge structures to enable self-maintaining and adaptive computation. Deutsch’s epistemic thesis complements this by defining genuine knowledge as extendable, explainable, and discernible—criteria absent from today’s black-box AI [

25]. Finally, Fold Theory (Hill) emphasizes recursive coherence between observer and observed, reinforcing the idea that computation must integrate structure, meaning, and adaptation into a single evolving process [

26,

27,

28].

Together, these perspectives point to a post-Turing model of computation in which information, knowledge, and purpose are intrinsic to the act of computing. Building on this synthesis, we introduce Mindful Machines: distributed software systems that integrate autopoietic (self-regulating) and meta-cognitive (self-monitoring) behaviors. Their operation is guided by a Digital Genome—a persistent knowledge-centric code that encodes functional goals, policies, and ethical constraints [

29].

To operationalize this vision, we present the Autopoietic and Meta-Cognitive Operating System (AMOS). Unlike conventional orchestration platforms, AMOS provides:

Self-deployment, self-healing, and self-scaling via redundancy and replication across heterogeneous cloud infrastructures.

Semantic and episodic memory implemented in graph databases to preserve both rules/ontologies and event histories.

Cognizing Oracles that validate knowledge and regulate decision-making with transparency and explainability.

We evaluate this architecture through a case study: re-implementing the classic credit-default prediction task discussed in detail in Klosterman’s book [

30] as a distributed service network managed by AMOS. Whereas conventional ML pipelines process static datasets with limited adaptability, our implementation demonstrates resilience under failure, auditable decision provenance, and real-time adaptation to behavioral changes.

The contributions of this paper are fourfold:

We ground the design of Mindful Machines in a synthesis of GTI, BMT, Deutsch’s epistemic thesis, and Fold Theory.

We describe the architecture of AMOS and its integration of autopoietic and meta-cognitive behaviors.

We demonstrate feasibility by deploying a cloud-native loan default prediction system composed of containerized services.

We show how this paradigm advances transparency, adaptability, and resilience beyond conventional machine learning pipelines.

In doing so, this paper positions Mindful Machines as a pathway toward sustainable, knowledge-driven distributed software systems—bridging the gap between symbolic reasoning, statistical learning, and trustworthy autonomy.

In section 2, we describe the theory and in section 3, we discuss the system architecture and the implementation of the platform. In section 4, we describe the implementation of the loan default prediction application and in

Section 5, we discuss the results.

Section 6 concludes with our observations, comparison with traditional approaches and path for future applications.

2. Theories and Foundations of the Mindful Machines

The architecture of Mindful Machines rests on four interrelated theoretical pillars: the General Theory of Information (GTI), the Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT), Deutsch’s epistemic framework of knowledge, and Fold Theory. Each of these contributes a distinct but complementary perspective on the nature of information, computation, and knowledge, providing the conceptual grounding for a post-Turing computational paradigm.

2.1. General Theory of Information (GTI)

Burgin’s General Theory of Information broadens the scope of information beyond Shannon’s statistical and syntactic definitions. GTI frames information as a triadic relation among a carrier, a recipient, and the content conveyed. Crucially, it distinguishes between ontological information (the structures inherent in material systems) and epistemic information (the knowledge produced when signals are interpreted). This distinction highlights that computation is not merely symbol manipulation but a process where structure and meaning interact. For Mindful Machines, GTI provides the foundation for treating information as an active principle of organization, enabling systems to self-regulate through meaningful knowledge flows rather than passive data streams.

2.2. Burgin-Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT)

Building on GTI, the Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis identifies the core limitation of the Turing model: the strict separation of the computer (hardware/runtime) from the computed (symbols and processes). In Turing machines, computation is closed, context-free, and blind to semantics. BMT proposes structural machines, where the computer and the computed form a dynamically evolving unity. This shift enables autopoietic computation—systems that sustain and regenerate their own structure—and meta-cognitive capabilities, in which systems monitor and adapt their processes. Within Mindful Machines, BMT is realized through the Digital Genome, a persistent knowledge blueprint encoding structural rules, functional goals, and ethical constraints that guide system behavior and coherence.

2.3. Deutsch’s Epistemic Thesis (DET)

David Deutsch advances an epistemic view of knowledge in which genuine knowledge must be extendable, explainable, and discernible. These properties allow knowledge to serve as a foundation for scientific and technological progress, since it can be improved, justified, and understood. Current machine learning models, while powerful, largely fail to meet these standards: they produce correlations and predictions but lack transparent explanations grounded in structure. Mindful Machines address this gap by embedding prior knowledge into persistent schemas and by enabling self-monitoring and revision. In doing so, they transform outputs into knowledge assets that evolve over time, embodying Deutsch’s epistemic principle within computation.

2.3. Fold Theory (FT)

Skye L. Hill’s Fold Theory provides a philosophical lens on how reality coheres through recursive interactions of the observer and the observed. It suggests that ontological structures (the world as it exists) and epistemic structures (the world as it is known) are folded together in shaping reality. This resonates strongly with both GTI and BMT: just as information and meaning are inseparable, and the computer and computed must be unified, so too must perception and knowledge co-create coherence. For Mindful Machines, Fold Theory supplies the metaphysical bridge, reinforcing that knowledge-centric computation is not external to systems but part of their lived process of adaptation and sense-making.

2.3. Towards Post-Turing Computation (PTC)

Taken together, these theories converge on a post-Turing model of computation. GTI articulates the ontological–epistemic duality of information; BMT overcomes the artificial separation of machine and meaning; Deutsch defines the criteria for valid and progressive knowledge; and Fold Theory situates computation in a recursive, participatory reality. Synthesized, these perspectives recast computation as a living process—guided by prior knowledge, shaped by feedback, and sustained through purposeful self-regulation.

Mindful Machines embody this vision by uniting hardware execution, knowledge representation, and adaptive regulation within a single evolving framework. Their theoretical grounding explains why they can exhibit autopoietic and meta-cognitive behaviors, and why the Digital Genome functions not merely as code, but as a structural and epistemic foundation for resilient, explainable, and sustainable distributed software systems.

3. System Architecture and the Autopoietic and Meta-Cognitive Operating System (AMOS)

The Autopoietic and Meta-Cognitive Operating System (AMOS) provides the execution environment for Mindful Machines. Unlike a monolithic operating system, AMOS functions as a distributed orchestration and regulation platform that instantiates, coordinates, and sustains services derived from the Digital Genome (DG).

The Digital Genome acts as a machine-readable blueprint of operational knowledge. It encodes functional goals, non-functional requirements, best-practice policies, and global constraints. This blueprint seeds a knowledge network that persists in a graph database, structured as both associative memory and event-driven history.

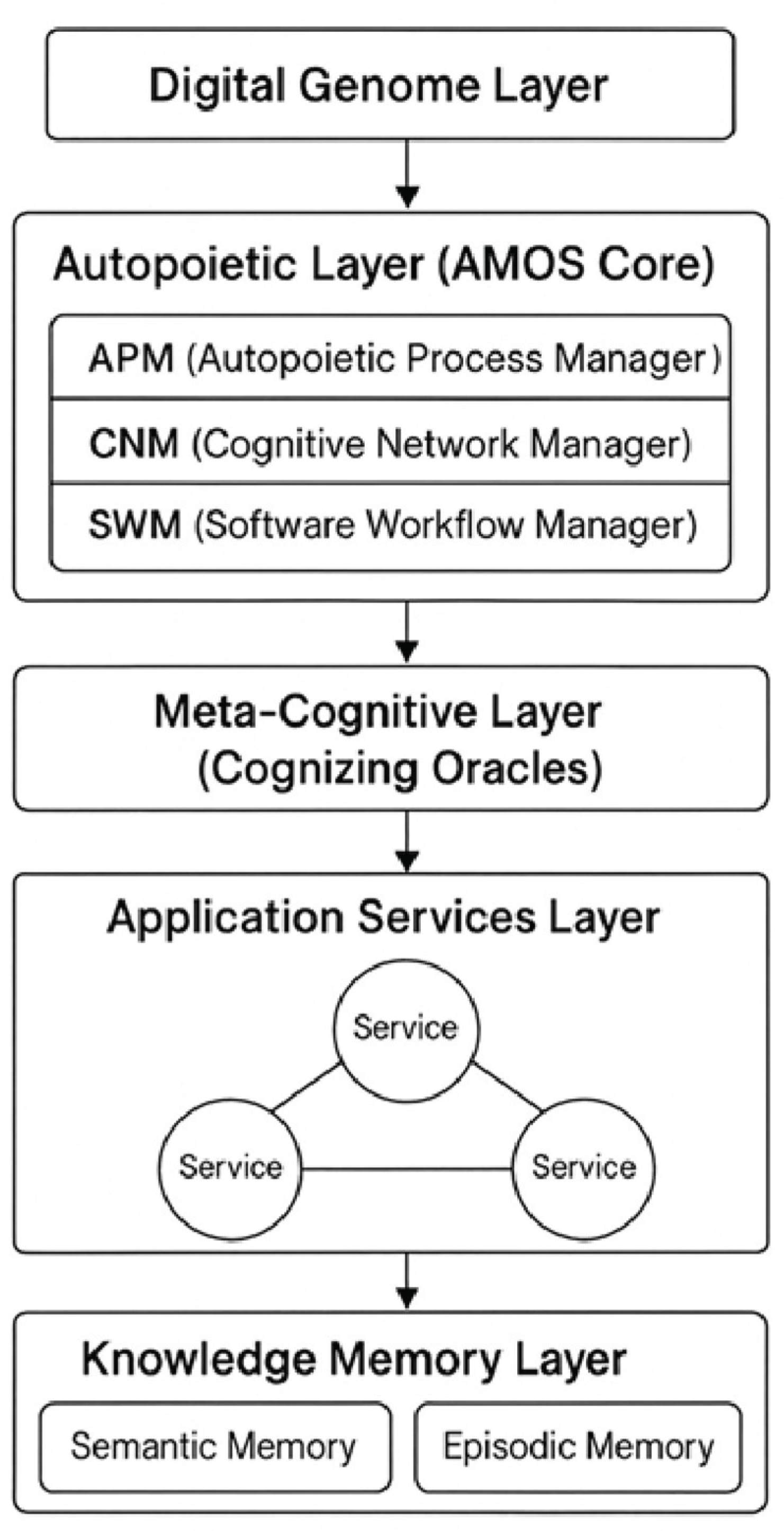

Figure 1 illustrates the layered architecture of AMOS:

Digital Genome Layer – Encodes goals, schemas, and policies, providing the prior knowledge blueprint for system behavior.

-

Autopoietic Layer (AMOS Core) – Implements resilience and adaptation through core managers:

- ○

APM (Autopoietic Process Manager): Deploys services, replicates them when demand rises, and guarantees recovery after failures.

- ○

CNM (Cognitive Network Manager): Manages inter-service connections, rewiring workflows dynamically.

- ○

SWM (Software Workflow Manager): Ensures execution integrity, detects bottlenecks, and coordinates reconfiguration.

- ○

Policy & Knowledge Managers: Interpret DG rules, enforce compliance, and ensure traceability.

Meta-Cognitive Layer – Cognizing Oracles oversee workflows, monitor inconsistencies, validate external knowledge, and enforce explainability.

Application Services Layer – A network of distributed services (cognitive “cells”) that collaborate hierarchically to execute domain-specific functions.

Knowledge Memory Layer – Maintains long-term learning context through:

Semantic Memory: Rules, ontologies, and encoded policies.

Episodic Memory: Event-driven histories that capture interactions and causal traces.

3.1. Service Behavior and Global Coordination

Each service in AMOS behaves like a cognitive cell with the following properties:

Inputs/Outputs: Services consume signals, events, or data, and produce results, insights, or state changes guided by DG knowledge.

Shared Knowledge: Services update semantic and episodic memory, ensuring global coherence, similar to biological signaling pathways.

Sub-networks: Services form functional clusters (e.g., billing or monitoring), analogous to specialized tissues.

Global Coordination: Sub-networks are orchestrated by AMOS managers to ensure system-wide goals are preserved.

Key properties of this design include:

Local Autonomy: Services act independently, improving resilience.

Global Coherence: Shared memory and DG constraints ensure alignment.

Evolutionary Learning: Services adapt to improve efficiency and workflows.

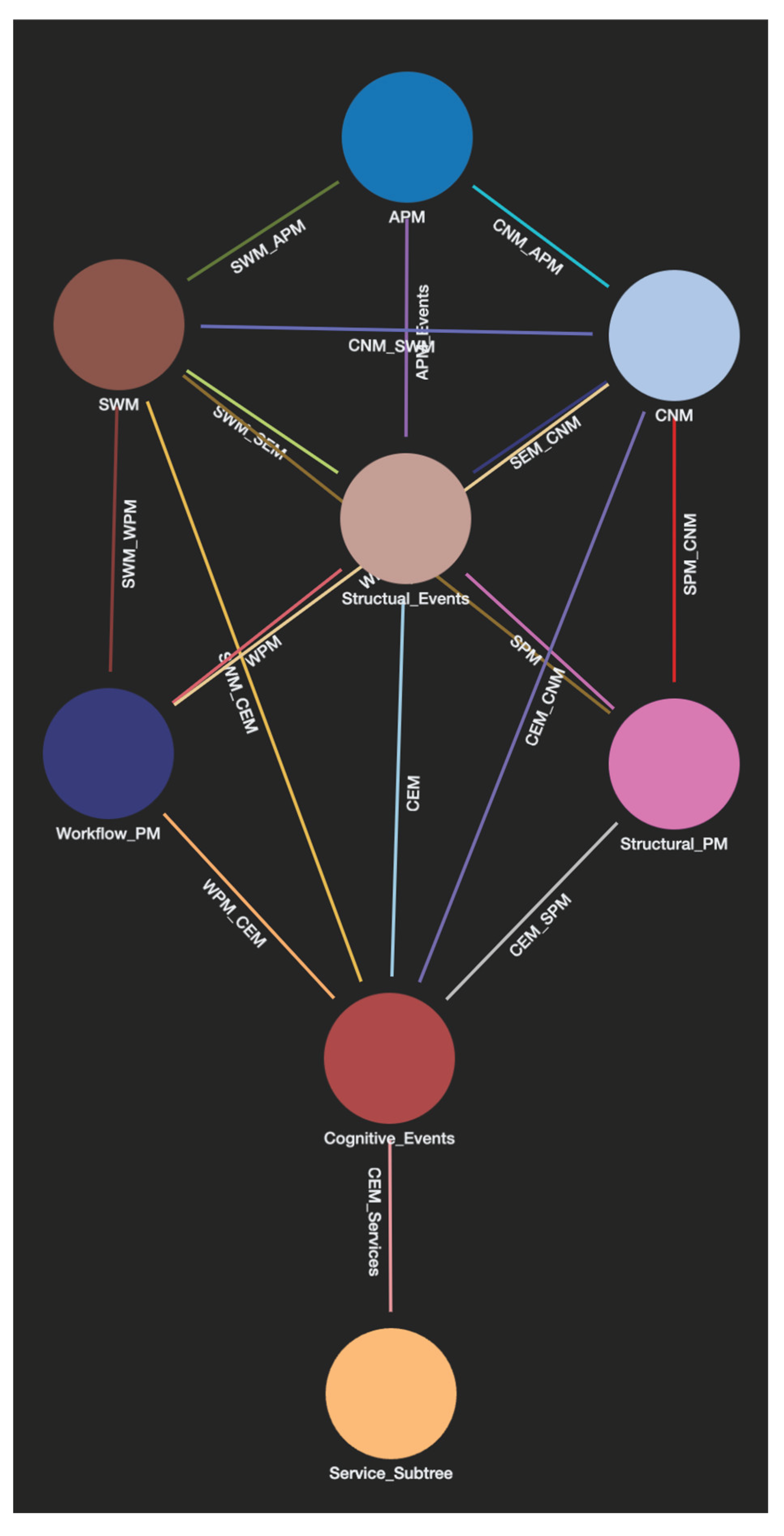

Collectively, these functions enable self-deployment, self-healing, self-scaling, knowledge-centric operation, and traceability, distinguishing AMOS from conventional orchestration systems (

Figure 2).

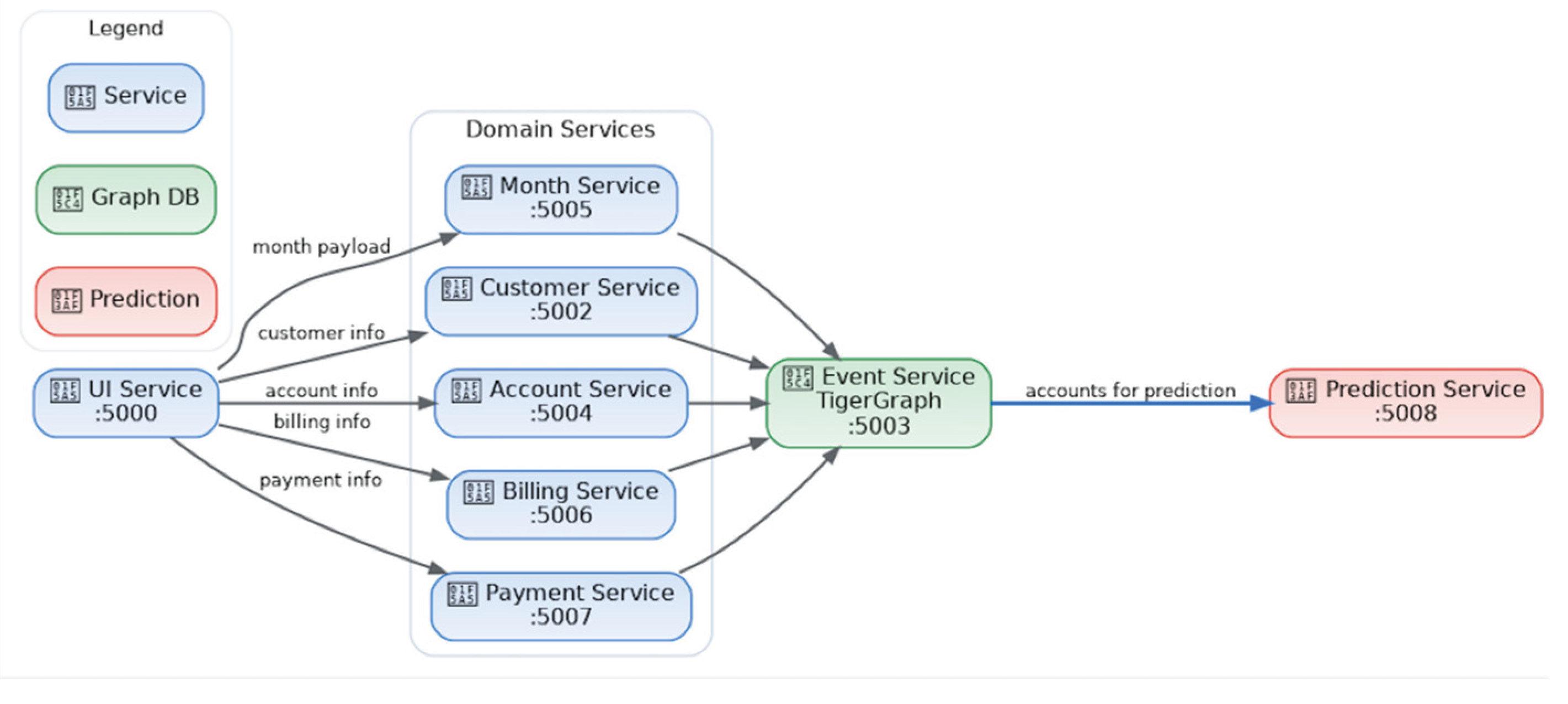

3.2. Implementation: Distributed Loan Default Prediction

To demonstrate feasibility, we re-implemented the loan default prediction problem (Klosterman, 2019) using AMOS. The original problem—predicting whether a customer will default based on demographics and six months of credit history—was approached conventionally via supervised machine learning on a static dataset of 30,000 customers.

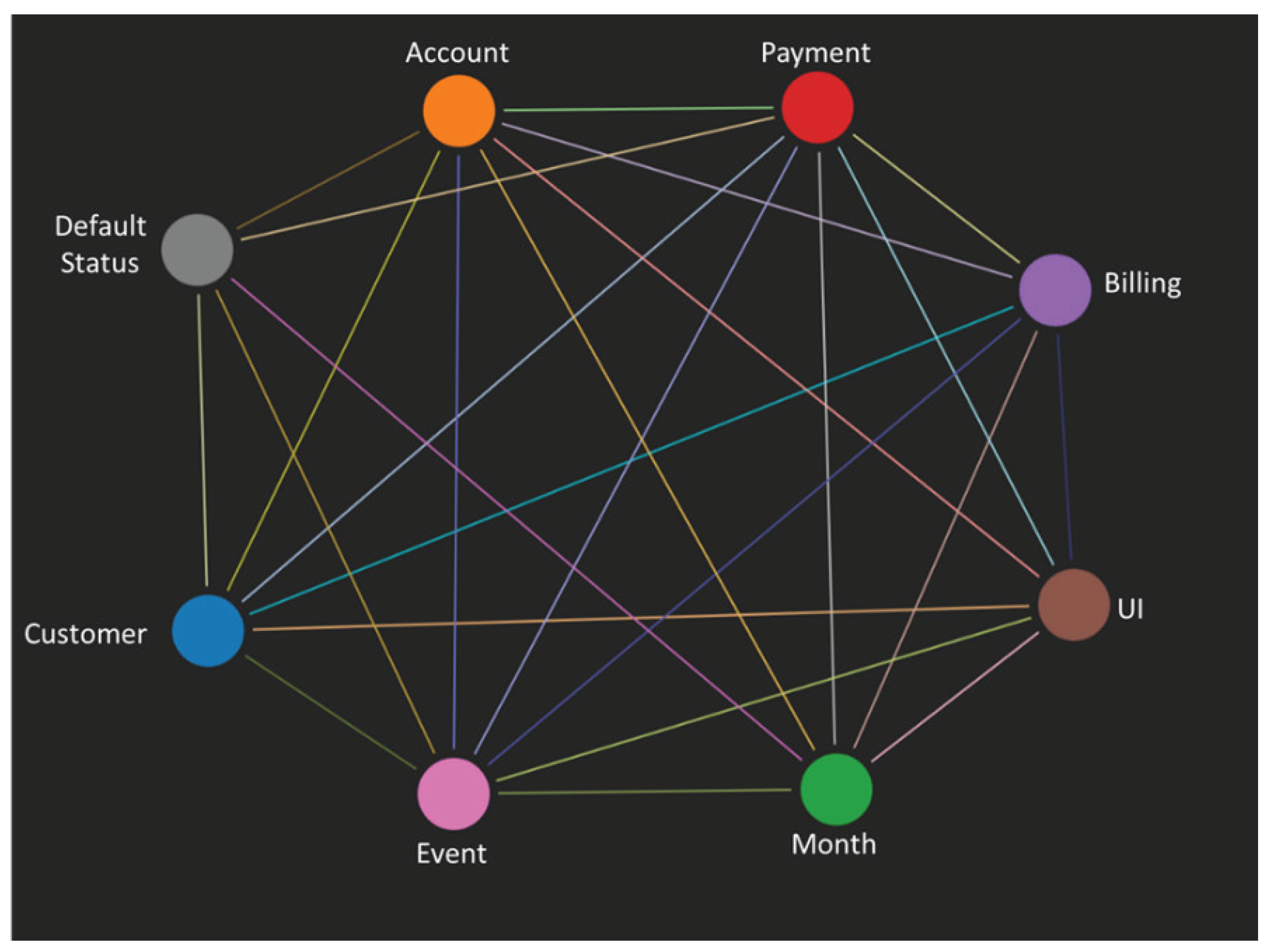

In contrast, AMOS decomposes the application into containerized microservices that communicate via HTTP and persist events in a graph database:

Cognitive Event Manager: Anchors the data plane, recording episodic and semantic memory.

Customer, Account, Month, Billing, and Payment Services: Model financial behaviors as event-driven processes.

UI Service: Ingests data and distributes workloads to domain services.

Default_Prediction Service: Computes next-month defaults using rule-based or learned models, providing auditable results.

This event-sourced design enables reproducibility, explainability, and controlled evolution. Every prediction can be traced back through causal chains (e.g., Bill issued in April → Payment received → Default risk computation).

3.3. Demonstration of Autopoietic and Meta-Cognitive Behaviors

The distributed system is implemented in Python with TigerGraph as the graph database. AMOS manages container deployment on cloud infrastructure (IaaS/PaaS) with autopoietic functions such as self-repair via health checks and policy-driven restarts.

The Cognitive Event Manager provides semantic and episodic memory that supports meta-cognition. At runtime, services:

Detect anomalies (e.g., distributional drift in repayment codes).

Adapt dynamically (e.g., switching from a rule-based baseline to logistic regression when model performance degrades).

Provide explanations through event provenance queries (e.g., why was a customer labeled at risk?).

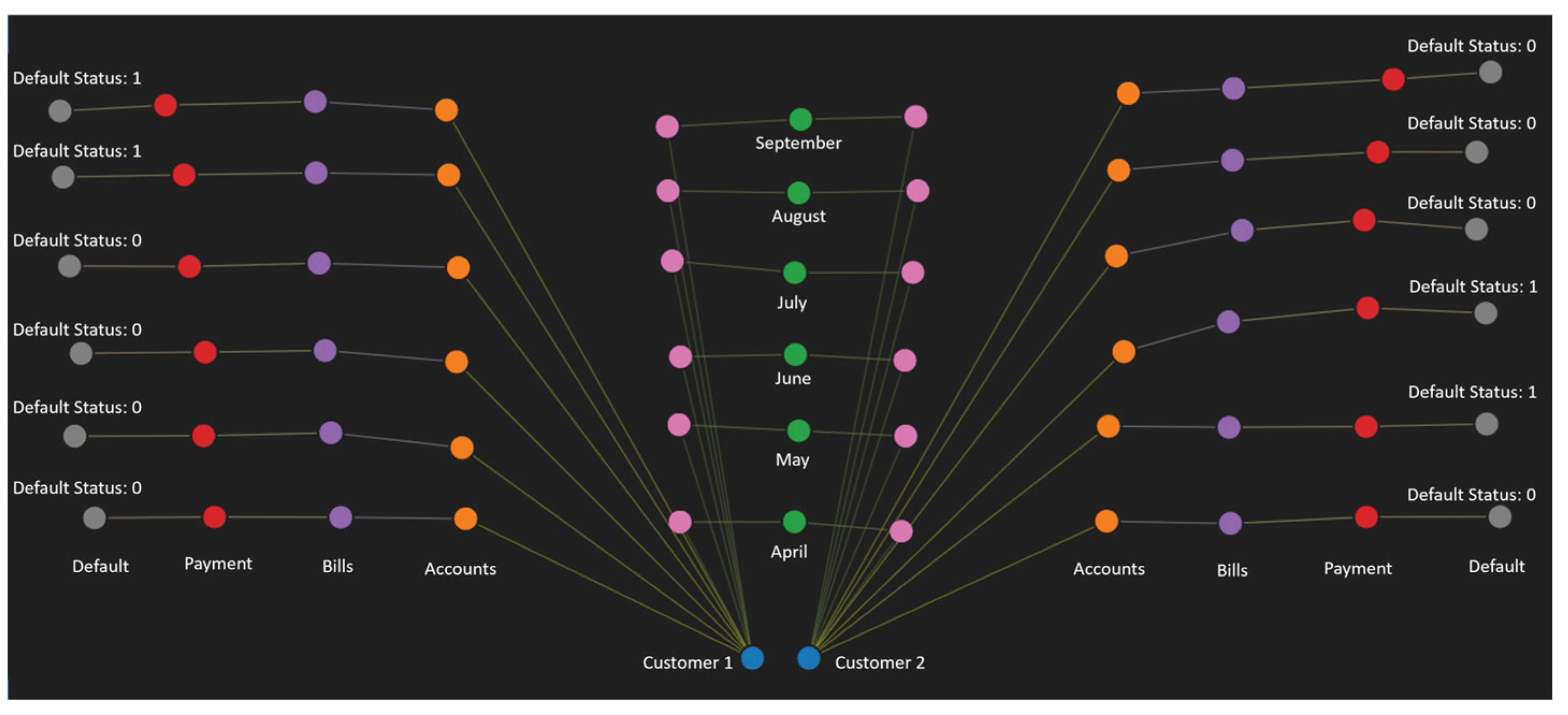

This transforms a conventional ML pipeline into a living system with introspection, transparency, and resilience (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

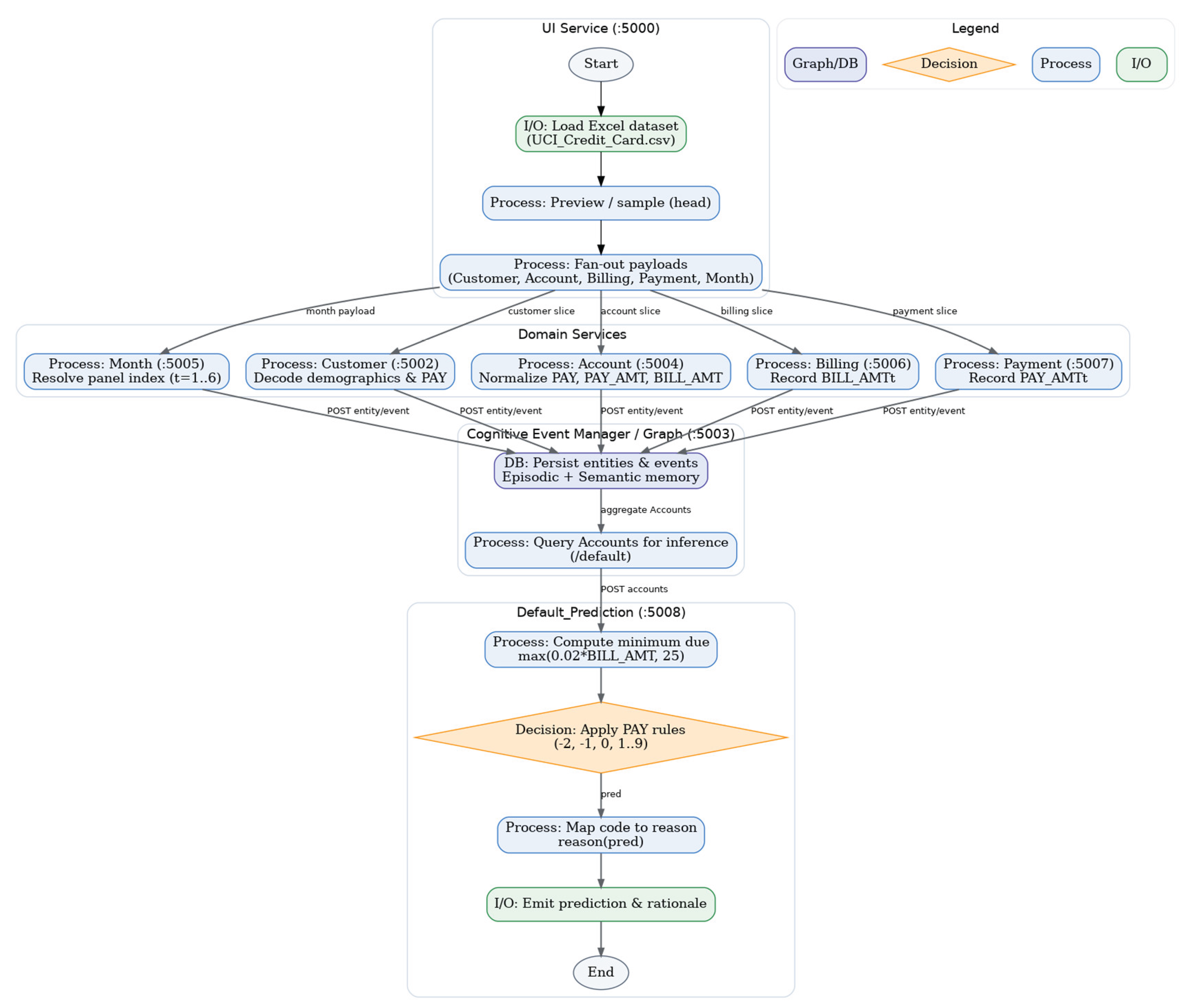

Figure 4: Workflow Diagram for GTI based credit default prediction implementation.

Figure 4 describes the workflow implementation for the distributed software applicating in the cloud. The numbers in the parentheses represent the port service for the URL to enable communication between interacting services.

Figure 4 Workflow diagram of the GTI/DG-based credit-default implementation on AMOS. Services (with ports) form the control/data plane; the Cognitive Event Manager persists events and entities to the graph, and Default_Prediction consumes the latest month to infer next-month outcomes.

4. What We Learned from the Implementation

In developing the loan default prediction application on the AMOS platform, we demonstrated how a conventional machine learning task can be restructured as a knowledge-centric, autopoietic system. The application was decomposed into modular and distributed services—including Customer, Account, Billing, Payment, and Event—each designed to perform a single, well-defined function. This modularization allowed the system to inherit the resilience and adaptability of distributed architectures.

Both functional requirements (e.g., prediction logic, data handling, feature generation) and non-functional requirements (e.g., performance, resilience, compliance, traceability) were encoded in the Digital Genome (DG). By doing so, the DG not only served as a design blueprint but also provided a persistent source of policies and constraints to regulate runtime behavior.

The system integrated two complementary forms of memory: associative memory, capturing patterns of past behavior, and event-driven history, recording temporal sequences of interactions. Together, these memory structures enabled continuous learning and made decision trails auditable over time.

Autopoietic and cognitive regulation were maintained through the AMOS core managers. The Autopoietic Process Manager (APM) ensured automatic deployment and elastic scaling of services; the Cognitive Network Manager (CNM) preserved inter-service connectivity under changing conditions; and the Software Workflow Manager (SWM) guaranteed logical process execution and recovery after disruption. These managers collectively provided the system with self-healing and self-sustaining properties.

Finally, large language models (LLMs) were leveraged during development, not as predictive engines, but as knowledge assistants. Their broad access to global knowledge was applied to schema design, service boundary discovery, functional requirement translation, and code/API generation. This highlights the complementary role of LLMs: they accelerate system design and prototyping, while AMOS ensures resilience, transparency, and adaptability in deployment.

Figure 5 depicts the state evolution of two customers with default prediction status shown.

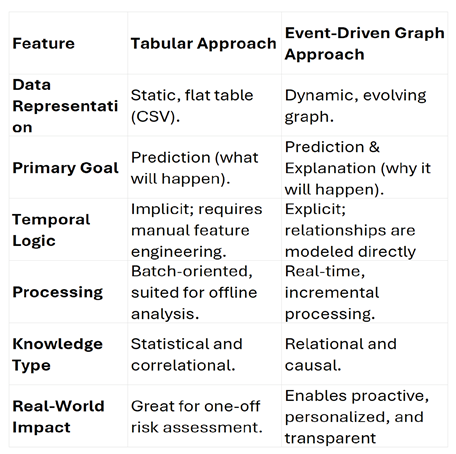

4.1. Comparison with Conventional Pipelines:

Unlike traditional machine learning pipelines, which treat credit-default prediction as a static process (data preprocessing → feature engineering → model training → evaluation), the AMOS implementation transforms the task into a living, knowledge-centric system. Conventional pipelines deliver one-shot predictions on fixed datasets, with limited adaptability, traceability, or resilience. In contrast, AMOS maintains event-sourced memory, autopoietic feedback loops, and explainable decision trails, enabling the system to adapt to changing behaviors in real time while preserving transparency. This shift marks the difference between data-driven computation and knowledge-driven orchestration, demonstrating the potential of Mindful Machines to extend beyond conventional AI workflows.

Table 1 shows the comparison between two methods.

5. Discussion and Comparison with Current State of Practice

The implementation of AMOS highlights a fundamental departure from conventional machine learning pipelines. In Data Science Projects with Python (Klosterman, 2019), the credit-default prediction problem is solved through a linear process of data preprocessing, feature engineering, model training, and evaluation. While effective for static datasets, this approach exhibits several limitations:

Lack of adaptability – the model must be retrained when data distributions shift.

Bias and brittleness – results are constrained by dataset composition, often underrepresenting rare but critical cases.

Limited explainability – outputs are tied to abstract model weights rather than transparent causal chains.

Fragile resilience – pipelines are vulnerable to disruptions in data flow or system execution.

In contrast, the AMOS-based implementation demonstrates how a knowledge-centric architecture overcomes these shortcomings. By encoding both functional and non-functional requirements in the Digital Genome, the system embeds resilience and compliance directly into its design. Autopoietic managers ensure continuity under failure or load changes, while semantic and episodic memory provide persistent context for explainability and adaptation. Cognizing oracles introduce transparency and governance, ensuring that system behavior remains aligned with global goals.

Beyond the loan default case, these findings generalize to a wide range of domains where AI must operate in dynamic, high-stakes environments such as finance, healthcare, cybersecurity, and supply chain management. Traditional pipelines, optimized for accuracy on static datasets, fall short in such contexts. Mindful Machines, by contrast, transform computation into a living process, where meaning, memory, and adaptation are intrinsic to the architecture.

Table 1 summarizes the differences between conventional ML approaches and AMOS. As the comparison indicates, the novelty lies not in replacing machine learning, but in integrating it into a broader autopoietic and meta-cognitive framework that ensures transparency, resilience, and sustainability.

6. Conclusions

This work introduces Mindful Machines as a post-Turing paradigm for distributed software systems, demonstrating their feasibility through the AMOS platform and a loan default prediction case study. Grounded in the General Theory of Information, the Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis, Deutsch’s epistemic framework, and Fold Theory, Mindful Machines unify the computer and the computed into a single self-regulating system.

The case study illustrates several benefits:

Transparency and Explainability – event-driven histories provide auditable decision trails.

Resilience and Scalability – autopoietic managers enable continuous operation under failures or demand fluctuations.

Real-Time Adaptation – workflows evolve with behavioral changes rather than requiring retraining.

Integration of Knowledge Sources – statistical learning is augmented with structured knowledge and global insights via LLMs.

Individual and Collective Intelligence – the system can detect anomalies at both single-user and group levels.

In short, the textbook pipeline predicts defaults in a static, one-shot manner, whereas the AMOS-based approach reimagines prediction as a knowledge-centric ecosystem capable of adaptation, self-regulation, and long-term learning. This shift suggests that Mindful Machines can serve as a general framework for building transparent, adaptive, and ethically aligned AI infrastructures.

Future work will extend these principles to larger-scale, real-world applications, testing the scalability of autopoietic and meta-cognitive mechanisms across domains such as healthcare diagnostics, enterprise resilience, and autonomous cyber-defense. By aligning computational evolution with the principles of knowledge, purpose, and adaptability, Mindful Machines represent a pathway toward trustworthy and sustainable AI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M; methodology, R.M, P.K.; software, P.K.; validation, R.M., P.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The Authors acknowledge Dr. Judith Lee, Director of the Center for Business Innovation for many discussions and continued encouragement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMOS |

Autopoietic and Meta-Cognitive Operating System |

| DG |

Digital Genome |

| APM |

Autopoietic Manager |

| CNM |

Cognitive Network Manager |

| SWM |

Software Workflow Manager |

| PM |

Policy Manager |

| SEM |

Structural Event Manager |

| CEM |

Cognitive Event Manager |

| SPT |

Single Point of Truth |

Appendix A. Credit Default Prediction

The presented implementation constitutes a rule-based prediction service designed to assess short-term credit repayment behavior. Developed in Python and deployed via the Flask web framework, the service provides a programmatic interface for evaluating account-level payment dynamics. Specifically, it exposes a RESTful endpoint (/default) that accepts structured JSON input containing billing, payment, and historical status information for one or more accounts. The output is a structured JSON response that details both the predicted repayment status for the subsequent period and the minimum required payment.

At the core of the system is the predict_next_pay function, which encodes a deterministic decision structure for repayment classification. The algorithm first computes a minimum required payment, determined as the greater of a fixed threshold or a percentage of the current billing amount. Based on the relationship between the actual payment amount, the billed amount, and the current repayment status, the function then categorizes accounts into discrete outcome states. These states include unused accounts with no outstanding balance, full repayment, partial repayment meeting minimum obligations, and delinquent accounts with payment delays ranging from one to nine months. Such categorization provides a standardized measure of repayment performance that is readily interpretable.

To support transparency and interpretability, a companion function (reason) maps the numerical prediction codes to descriptive textual explanations. This design choice facilitates the integration of model outputs into downstream decision-making processes, particularly in domains where interpretability and auditability are paramount, such as consumer credit risk management. The service further introduces a binary indicator, default_next_month, which flags accounts with two or more months of predicted delinquency as at risk of default in the subsequent billing cycle.

Overall, this system illustrates a lightweight and transparent approach to repayment prediction. Unlike complex machine learning models, which may introduce opacity and higher computational costs, the presented service emphasizes rule-based reasoning and interpretability. Its modular design and RESTful interface allow for seamless integration into broader financial risk assessment workflows, while its reliance on explicit rules enhances reproducibility and facilitates validation in operational contexts.

Appendix B. Workflow Chart of the Program

Figure A1.

The workflow diagram of the software.

Figure A1.

The workflow diagram of the software.

References

- He, R., Cao, J., & Tan, T. (2025). Generative artificial intelligence: A historical perspective. National Science Review, 12(5), nwaf050. [CrossRef]

- Dillion, D., Mondal, D., Tandon, N. et al. AI language model rivals expert ethicist in perceived moral expertise. Sci Rep 15, 4084 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Linkon, Ahmed & Shaima, Mujiba & Sarker, Md Shohail Uddin & Badruddowza, & Nabi, Norun & Rana, Md Nasir Uddin & Ghosh, Sandip & Esa, Hammed & Chowdhury, Faiaz Rahat & Rahman, Mohammad Anisur. (2024). Advancements and Applications of Generative Artificial Intelligence and Large Language Models on Business Management: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Computer Science and Technology Studies. 6. 225-232. 10.32996/jcsts.2024.6.1.26.

- Gupta, Priyanka & Ding, Bosheng & Guan, Chong & Ding, Ding. (2024). Generative AI: A systematic review using topic modelling techniques. Data and Information Management. 100066. 10.1016/j.dim.2024.100066.

- Ogunleye, B., Zakariyyah, K. I., Ajao, O., Olayinka, O., & Sharma, H. (2024). A Systematic Review of Generative AI for Teaching and Learning Practice. Education Sciences, 14(6), 636. [CrossRef]

- J. Hutson (2025). Ethical Considerations and Challenges. IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M. G., Pantanowitz, L., Jackson, B., Palmer, O., Visweswaran, S., Pantanowitz, J., Deebajah, M., & Rashidi, H. H. (2025). Ethical and bias considerations in artificial intelligence/machine learning. Modern Pathology, 38(3), Article 100686. [CrossRef]

- Afroogh, S., Akbari, A., Malone, E. et al. Trust in AI: progress, challenges, and future directions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1568 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Shangying Hua, Shuangci Jin, Shengyi Jiang; The Limitations and Ethical Considerations of ChatGPT. Data Intelligence 2024; 6 (1): 201–239. [CrossRef]

- John Banja (2020). How Might Artificial Intelligence Applications Impact Risk Management? AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(11):E945-951. [CrossRef]

- Nisa, U., Shirazi, M., Saip, M. A., & Mohd Pozi, M. S. (2025). Agentic AI: The age of reasoning—A review. Journal of Automation and Intelligence. [CrossRef]

- Zota, R. D., Bărbulescu, C., & Constantinescu, R. (2025). A Practical Approach to Defining a Framework for Developing an Agentic AIOps System. Electronics, 14(9), 1775. [CrossRef]

- Blackman, R. (2025, June 13). Organizations aren’t ready for the risks of agentic AI. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2025/06/organizations-arent-ready-for-the-risks-of-agentic-ai.

- The Society of Genes Yanai, I., & Lercher, M. J. (2016). The society of genes. Harvard University Press.

- Ramakrishnan, V. (2024). Why we die: The new science of aging and the quest for immortality. William Morrow.

- Ramakrishnan, V. (2018). Gene machine: The race to decipher the secrets of the ribosome. Basic Books.

- Burgin, M. Theory of Information: Fundamentality, Diversity, and Unification; World Scientific: Singapore, 2010. [Google Scholar].

- Burgin, M. Theory of Knowledge: Structures and Processes; World Scientific Books: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar].

- Burgin, M. Structural Reality; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar].

- Burgin, M. Triadic Automata and Machines as Information Transformers. Information 2020, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef].

- Burgin, M. The Rise and Fall of the Church-Turing Thesis. Manuscript. Available online: http://arxiv.org/ftp/cs/papers/0207/0207055.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Burgin, M.; Mikkilineni, R. From Data Processing to Knowledge Processing: Working with Operational Schemas by Autopoietic Machines. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2021, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef].

- Burgin, M.; Mikkilineni, R. On the Autopoietic and Cognitive Behavior. EasyChair Preprint No. 6261, Version 2. 2021. Available online: https://easychair.org/publications/preprint/tkjk.

- Mikkilineni R. A New Class of Autopoietic and Cognitive Machines. Information. 2022; 13(1):24. [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, D. (2011). The beginning of infinity: Explanations that transform the world (1st American ed.). Viking.

- Hill, S. L. (Year). Fold Theory: A Categorical Framework for Emergent Spacetime and Coherence. Retrieved from Academia.edu.

- Hill, S. L. (Year). Fold Theory II: Embedding Particle Physics in a Coherence Sheaf Framework. Retrieved from Academia.edu.

- Hill, S. L. (Year). Fold Theory III: Fractional Fold Theory, Curvature and the Mass Spectrum. Retrieved from Academia.edu.

- Mikkilineni, R. (2025). General Theory of Information and Mindful Machines. Proceedings, 126(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Klosterman, S. (2019). Data Science Projects with Python: A Case Study Approach to Successful Data Science Projects Using Python, Pandas, and Scikit-learn. Germany: Packt Publishing.

- Beer, S. (1985). Diagnosing the System for Organizations. United Kingdom: Wiley.

- Beer, S. (1984). The Viable System Model: Its Provenance, Development, Methodology and Pathology. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 35(1), 7–25. [CrossRef]

- F.G. Varela, H.R. Maturana, R. Uribe, Autopoiesis: The organization of living systems, its characterization and a model, Biosystems, Volume 5, Issue 4, 1974, Pages 187-196, ISSN 0303-2647. [CrossRef]

- Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1980). Autopoiesis and cognition: The realization of the living. D. Reidel Publishing Company.

- Mikkilineni, R. A New Class of Autopoietic and Cognitive Machines. Information 2022, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).