1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Against the backdrop of intensifying geopolitical conflicts, rising trade frictions and mounting global uncertainties, the threats of supply chain decoupling and the risks of disruption have been exacerbated, making supply chain restructuring imperative. In this process, how to diversify supply chain risks while remaining highly vigilant against “black swan” events and preventing “gray rhino” incidents has become core concerns [

1]. From the perspective of supply chain globalization, supply uncertainty induced by geopolitical conflicts and trade frictions, together with technological monopolies and technological sanctions, generates uncertain risks for producers’ supply chains (hereinafter referred to as “force majeure risks”), thereby triggering threats of decoupling and risks of disruption [

2]. To address this issue, this paper constructs a two-tier supply chain model consisting of upstream suppliers and downstream manufacturers, where the downstream manufacturers are the local leading firms, occupying the core positions of local supply chains and primarily engaging in deep processing, fine processing and refined processing activities, and so on. By contrast, the upstream suppliers are engaged in resource extraction and labor-intensive activities, and so on. Furthermore, as upstream suppliers whose behaviors directly affect the returns of leading firms provide raw materials and other essential inputs to leading firms, leading firms cannot fully control the actions of upstream suppliers. This interaction exhibits the essential feature in economics, namely, a principal agent relationship [

3,

4]. On this basis, on the one hand, this paper employs a principal agent model to analyze how leading firms renegotiate with their upstream suppliers in the context of supply chain restructuring. Within this framework, the restructuring process is evaluated by comparing the post-restructuring return of upstream suppliers, leading firms and the entire supply chain, thereby assessing the magnitude of risks inherent in supply chain restructuring [

5]. Concurrently, changes in the overall returns of all firms within the supply chain are used to evaluate the sharing principles of return and risk among enterprises. On the other hand, from the perspectives of firm and government, this paper examines the game of cooperation and competition within a supplier–leading firm model, in which the leading firm undertakes cluster-based supply chain restructuring across regions and across supply chains.

1.2. Literature Review

The international political economy has become increasingly complex and volatile. Great power rivalries, geopolitical conflicts, the Ukraine crisis and the global pandemic have collectively triggered energy and food crises worldwide, while intensified market competition has further exacerbated risks and uncertainties in supply chain. Moreover, the turbulent external environment significantly moderates the relationship between supply chain restructuring and transformation capacity [

6]. Meanwhile, the inherent nature of “duckweed economy” of global value chains may give rise to security and stability concerns in industrial and supply chains. Global value chains are evolving toward localization, regionalization and diversification [

7]. The traditional linear structure of supply chains exposes a structural tension between efficiency and security, making research on supply chain restructuring and multi-actor coordination mechanisms an emerging academic focus [

8,

9].

To address the above issues, Tang (2006) [

10] proposed that supply chains should be restructured against disruptions by promoting flexible sourcing and information visibility. Based on the capability–vulnerability framework, Pettit et al. (2010) [

11] further constructed a theoretical model of the supply chain resilience index. The shift from a traditional channel perspective of the top-down product distribution in a push-based supply chain to a pull-based supply chain perspective of the bottom-up product creation reflects a reverse integration process in which downstream distribution organizations act as leading firms while upstream manufacturers serve as node enterprises. This process identifies a restructuring direction through which traditional organizations can overcome the limitations of profit model to pursue innovation [

12]. To mitigate the negative impacts of global supply chain disruptions on domestic economies, governments worldwide have invested substantial resources to reduce overdependence on imported intermediate and final goods, with subsidies and financial support alleviating the adjustment costs pressure from industrial chain restructuring [

13]. More recent studies highlight that the entry, restructuring and exit of export-oriented supply chains constitute the underlying reason of uncertainty at the product level [

14]. The cultivation of leading firm with international competitiveness and discourse power enhances the risk resilience of critical supply chain nodes [

15]. Concurrently, advances in artificial intelligence (AI) are propelling supply chain platform reconstruction, ecosystem reshaping and advantage rebuilding [

16]. Emerging multi-level network recovery strategies and cross-industry data-driven early warning systems [

8] as well as the introduction of digital twins and blockchain are further enhancing adaptive capacity under extreme risks [

17]. Nevertheless, most of these studies remain focused on technological and structural dimensions, with insufficient attention paid to strategic interactions and incentive mechanisms among multiple actors.

The transmission and compounding effects of external shocks have imposed significant negative impacts on Chinese firms’ positions in the global division of labor in supply chains, which has disrupted the ecosystem of China’s manufacturing supply chains, causing distortions and disorder in global supply chain reconstruction. In response, Chinese scholars emphasize the establishment of autonomous and controllable supply chain strategies, the development of dual-cycle supply chain models and the strengthening of resilience and robustness of the supply chain [

18]. For instance, Japan views India as both a strategic partner for industrial transfer and a hub for overseas supply chain deployment, while India regards Japan as a cooperative partner in supply chain restructuring. For China, the deepening of Japan–India cooperation under the background of global supply chain restructuring could result in a dual squeeze dilemma. Thus, China must focus on upgrading its domestic industrial structure, consolidating trade ties with Japan and India and deeply integrating into global supply chain systems [

19]. Similarly, developed economies such as the United States and the European Union aim to safeguard national security and economic autonomy by redesigning so-called resilient and secure global supply chains. The future global supply chains will largely depend on the dynamic interplay between great power geopolitical competition, global free market forces, government intervention and firm’s responses [

20]. Against the backdrop of strategic competition between China and the United States, the supply chains and trade pathways of key industries such as integrated circuits and semiconductors, new energy vehicles and the photovoltaic sector are undergoing accelerated restructuring. China must adhere to the principle of mutual benefit and win–win cooperation, strengthen localization strategies, improve risk and return sharing mechanisms and encourage favorable firms to expand abroad in order to improve global deployment and mitigate supply chain risks [

21].

To provide a more precise assessment of the aforementioned issues, scholars have gradually applied principal agent theory to supply chain governance, particularly under asymmetric information. This framework has been widely employed to explain effort level games and risk sharing problems between leading firms and upstream suppliers. For example, Cachon and Lariviere (2005) [

22] established a basic supply chain contract model that explored how quantity incentives and return sharing mechanisms improve coordination efficiency. Partyka (2021) [

23] systematically reviewed applications of principal agent models in supply chains, noting that most remain static in nature and fail to account for effort costs, risk spillovers and strategic interactions in an integrated manner. More recently, Hall et al. (2024) [

24] introduced a model tailored to dynamic supply chain restructuring, which explores incentive optimization pathways for firms under cyclical shocks and extends the applicability of traditional models to uncertain environments.

Meanwhile, industrial cluster and collaboration mechanisms across supply chains are increasingly recognized as organizational forms that enhance supply chain security and resilience. Porter (1998) [

25] argued that cluster promotes innovation efficiency and resource sharing, thereby generating spatial competitive advantages. Buciuni and Pisano (2021) [

26] further emphasized the stabilizing role of governance capabilities in supply chain clusters under high risk shocks. Empirical research by Shi et al. (2023) [

27] revealed that cluster structures significantly improve adaptive capacity to supply chain disruptions, though the effect is moderated by supply chain concentration. However, current studies largely focus on intra-regional cluster linkages, with limited attention to collaboration mechanisms across regions and across supply chains, and few have developed systematic behavioral game-theoretic models.

Recent years have witnessed that game-theoretic theory and multi-agent decision models have been widely applied to supply chain disruption management, contract coordination and partner selection [

28]. Existing researches model the firms’ behavioral response paths through simulation and evolutionary game-theoretic approaches. Yet for supply chain restructuring, most studies exclude firms’ risk sharing mechanisms, effort incentives and cooperation probabilities, and they do not explore cluster-based cooperation and competition strategies within a supplier–leading firm model.

In summary, existing researches have yielded important insights into security and resilience of the supply chain, incentive contract design and industrial clusters. Nevertheless, systematic analysis of the following issues remains lacking: (1) under force majeure risks, with supply chain decoupling or breakage, how can the leading firm design incentive mechanisms that guide upstream suppliers to participate in supply chain restructuring? (2) within a supplier–leading firm model, how can upstream suppliers’ effort levels, risk sharing and cooperation willingness be incorporated in a game-theoretic model, and how can supply chain restructuring be analyzed from a return and risk perspective? (3) under force majeure risks, leading firms often cluster in regions where supply chains are relatively well-developed, together with related local firms, reconstruct new supply chain structures, resulting in cluster-based supply chain restructuring across regions and across supply chains. How can the evolutionary logic of cluster-based supply chains restructuring be explained from the perspective of collaboration across regions and across chains? Accordingly, taking a return and risk perspective and a supplier–leading firm model, the paper develops a game-theoretic model of supply chain restructuring that incorporates upstream supplier’s incentive constraints, effort level, cluster environment and cooperation probability against complex environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Formulation

Assume that the downstream manufacturer (hereafter “the leading firm,” denoted

) must purchase one unit of intermediate goods from an upstream supplier (denoted

) for every unit of the final product it produces. To ensure a stable supply of the intermediate goods, the leading firm has eatablished a long-term partnership with a single upstream supplier, who commits to continuous deliveries of intermediate goods at a fixed price (

). Let the market demand curve for the final product be

[

29]. If the leading firm’s marginal production cost is

, its profit will be

.

Assuming that every upstream supplier operates with a constant marginal cost (), its profit can therefore be expressed as . Here, the subscript indexes individual supply chains, while n denotes the total number of supply chains in the region.

It is assumed that the upstream supplier’s effort level is represented as a linear variable (

). In the context of supply chain restructuring, the return function of the leading firm (

) [

30] induced by the interaction with upstream suppliers and arising from the supply chain restructuring can be formulated as Equation (

1).

where

is a

risk coefficient that aggregates the myriad risk factors embedded in the leading firm’s revenue stream and hence serves as a risk-discount factor, which implied that the greater the risk encountered during supply chain restructuring, the smaller the value of

[

31]. The term

is a stochastic disturbance with mean 0 and variance

, representing unpredictable risks which is independent of the supplier’s effort level (

).

It is assumed that the leading firm is risk-neutral, while the upstream supplier is risk-averse. The leading firm establishes a principal agent relationship with upstream supplier in the supply chain through written contracts, formal agreements or at least verbal authorization, and adopts the following form of linear incentive contract as shown in Equation (

2).

where

is a fixed payment of upstream supplier that is independent of

, and

is the

output-sharing coefficient. A value of

implies that the upstream supplier bears no risk, whereas

indicates that the upstream supplier bears all the risks.

Accordingly, the expected return of the leading firm in the supply chain is denoted in Equation (

3).

Assume that the utility function of the upstream supplier exhibits absolute risk aversion, that is

, where

denotes the coefficient of absolute risk aversion and

represents actual monetary income. Assume that the effort cost of the upstream supplier can be expressed equivalently as monetary income and specified as Equation (

4).

where

is a constant that parameterises the upstream supplier’s

effort cost coefficient, which essentially reflects the proportion of costs borne by the upstream supplier when engaging in supply chain restructuring together with the leading firm. Accordingly, the expected return of the upstream supplier can be expressed as Equation (

5).

Here, it is assumed that

represents the risk cost of the upstream supplier, and when

, the risk cost becomes zero.

Further assume that the upstream supplier faces a positive opportunity cost. If it declines the leading firm’s delegation, its reservation income is

(for instance, the remuneration from other work). Then, its individual rationality (IR) constraint can be expressed as Equation (

6).

3. Results

3.1. Game-Theoretic Analysis of Supply Chain Restructuring Under Individual Rationality

Assume that both the leading firm and the upstream supplier are regarded as fully rational individual during the supply chain restructuring process.

3.1.1. Game-Theoretic Analysis of Supply Chain Restructuring under Symmetric Information

Assume that information is symmetric between the leading firm and the upstream supplier. Specifically, the leading firm can observe the upstream supplier’s effort level, although it cannot directly monitor detailed information such as delivery speed or input quality, moral hazard arising from hidden information on the upstream supplier’s side persists. Accordingly, the leading firm can reward or punish the upstream supplier on the basis of the observable effort. No additional incentive contract is required and therefore it needs only to design an

optimal risk sharing contract. That is, the leading firm must ensure that the upstream supplier’s expected return is no less than its reservation income

(i.e., the remuneration from other work), which constitutes the individual rationality (IR) constraint. Only under this condition will the upstream supplier accept the leading firm’s delegation and cooperate in supply chain restructuring. The model is formulated as Equation (7).

Based on the expected return functions of the leading firm and upstream supplier specified in Equation (7), the Lagrangian function is constructed and optimized and the corresponding first-order necessary conditions are then derived as Equation (8).

By substituting the optimal effort level (

) obtained from Equation (8) and the optimal output sharing coefficient (

) into the individual rationality (IR) constraint in Equation (7), the upstream supplier’s expected return at the boundary of the constraint can be derived, and the corresponding fixed payment is obtained as Equation (9).

By substituting the optimal effort level (

) and sharing coefficient (

) from Equation (8) and the optimal fixed payment (

) from Equation (9) into the linear incentive contract Equation (

2), the leading firm’s optimal incentive contract is expressed as Equation (10).

Equation (10) implies that under symmetric information, the leading firm’s optimal risk-sharing contract is characterised by:

, implying that the upstream supplier bears no risk.

Fixed payment , which exactly equals the reservation income of upstream supplier plus the risk-discounted effort cost.

3.1.2. Game-Theoretic Analysis Under Asymmetric Information

Under symmetric information, the upstream supplier’s risk cost can be regarded as zero during supply chain restructuring. Consequently, the leading firm cannot preclude the upstream supplier from ascribing every problem encountered in the supply chain restructuring to the force majeure risks, thereby existing potential moral hazard. Therefore, under asymmetric information, it is imperative to induce the upstream supplier to choose actions favorable to the leading firm’s expectations through an incentive contract.

1. Incentive Contract Design of the Leading Firm

Under asymmetric information, when the leading firm cannot observe the upstream supplier’s effort level, it must impose an incentive-compatibility constraint

, which implies that the risk borne by the leading firm in supply chain restructuring, the upstream supplier’s return sharing rate and its effort level should be linked together and vary in the same direction, thereby enabling effective supervision of the upstream supplier and preventing moral hazard from hidden actions [

32]. It can be expressed as Equations (11–12).

By jointly considering Equations (11–12) and solving the corresponding optimization problem, the first-order necessary conditions can expressed as Equation (13) and Equation (14).

By substituting Equation (13) and Equation (14) into the linear contract as shown in Equation (

2), the leading firm’s optimal incentive contract for the upstream supplier is obtained as Equation (15).

Equation (15) indicates that under asymmetric information in supply chain restructuring, the upstream supplier must bear a certain degree of risk. Generally preferred:

The more risk-averse the upstream supplier is and the greater its output variance (), the more inclined it is to lower its effort level, thereby reducing its own risk.

If the upstream supplier is risk-neutral (), the optimal contract requires the upstream supplier to bear all risks ().

The risk discount factor (

) of the leading firm varies in the same direction as

, that is, by linking the upstream supplier’s return sharing rate with the risk faced by the leading firm in supply chain restructuring, effective supervision of the upstream supplier’s behavior can be achieved, thereby mitigating moral hazard [

33].

2. Risk Sharing between the Leading Firm and Upstream Supplier under Asymmetric Information

Under asymmetric information, the leading firm cannot directly observe the upstream supplier’s effort level and the upstream supplier’s risk is expressed as Equation (13). From Equation (13), the upstream supplier’s risk cost can be derived as Equation (16).

The incentive cost incurred by the leading firm to induce the upstream supplier to select the desired effort level is expressed as Equation (17). Derivation details are provided in

Appendix A.1.

When

, Equation (17) can be simplified as Equation (18).

whereas for

, Equation (17) can be simplified as Equation (19).

Equation (16)–Equation (19) demonstrate that the leading firm’s risk-discount factor (

) and the upstream supplier’s risk and incentive costs vary congruently, that is, an increase in

raises both

and

, and vice versa. Consequently, the incentive-compatibility mechanism tightly aligns the risk borne by leading firm with the upstream supplier’s agency costs and mitigate moral hazard [

34].

Under asymmetric information and incentive incompatibility, supply chain restructuring may induce moral hazard of upstream suppliers, thereby reducing the overall efficiency of the supply chain. As the risks of supply chain restructuring increase, both leading firms and upstream suppliers face rising input costs. However, if upstream suppliers excessively avoid risks and are unwilling to exert effort, their own risk may be reduced, but the returns of leading firms will also diminish, while the risk costs and incentive costs of upstream suppliers will decline.

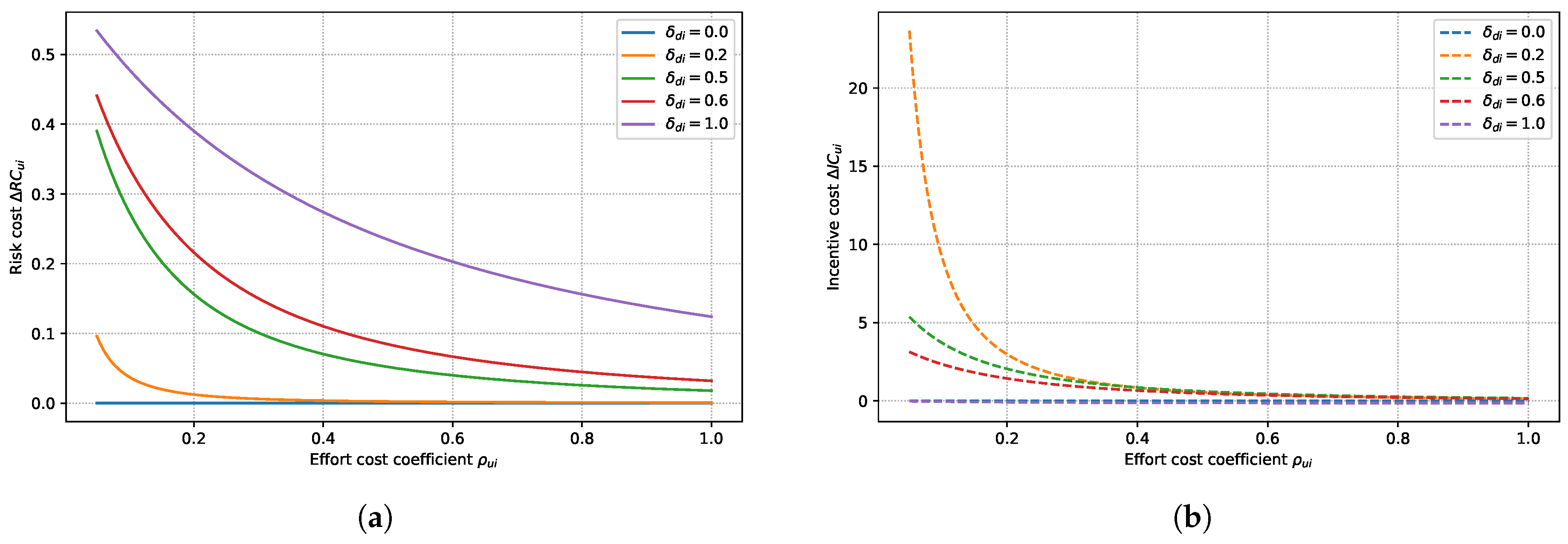

Parameter values used in

Figure 1 are as follows:

=

and 1, corresponding to no risk, low intensity risk, medium intensity risk, relatively high intensity risk and complete risk in supply chain restructuring, respectively. Based on simulations conducted by the

MATLAB, the game-theoretic outcomes between upstream suppliers and leading firms based on different levels of risk intensity (

) are illustrated in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the game trajectories between upstream suppliers and leading firms based on the different risk intensity. When the risk intensity reaches its maximum, both upstream suppliers and leading firms abandon their efforts, leaving no possibility for supply chain restructuring. The effort costs of upstream suppliers and the incentive costs of leading firms increase proportionally with the restructuring risk intensity, which indicates that higher restructuring risks leading to higher effort costs for upstream suppliers and higher incentive costs for leading firms. Therefore, by reasonably designing the parameters of effort costs and incentive mechanisms, leading firms can not only reduce risk costs but also suppress the moral hazard of upstream suppliers, thereby promoting the supply chain restructuring.

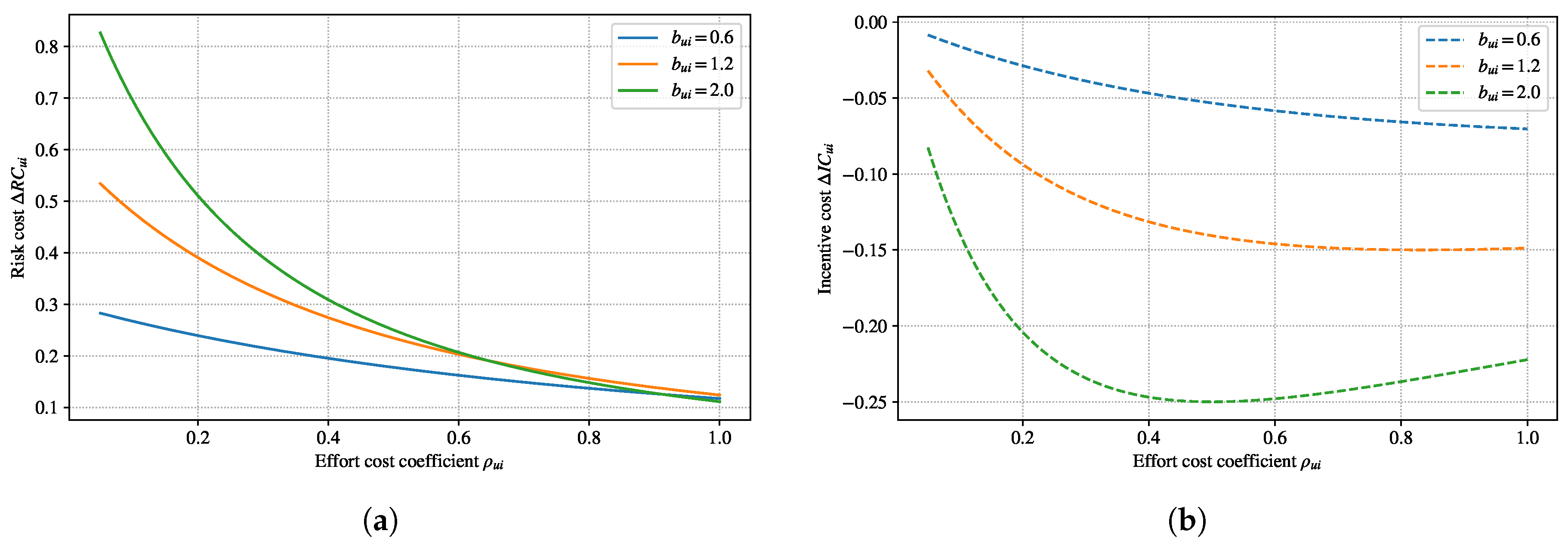

Parameter values used in

Figure 2 are as follows:

=

,

and 2, representing low, medium and high levels of absolute risk aversion for upstream suppliers, respectively. Based on simulations implemented by the

MATLAB, the game-theoretic results between upstream suppliers and leading firms based on different risk preferences (

) are presented in

Figure 2.

Figure 2 illustrates the game trajectories between upstream suppliers and leading firms based on different risk preferences of upstream suppliers. The effort costs of upstream suppliers increase positively with risk preferences. In other words, the greater the risk preferences of upstream suppliers, the higher their effort costs. In contrast, the incentive costs borne by leading firms are negatively related to the risk preferences of upstream suppliers, that is, the stronger the risk preferences of upstream suppliers, the lower the incentive costs for leading firms. Therefore, in the process of supply chain restructuring, it is essential to reasonably align the risk preferences of upstream suppliers with their effort levels to achieve a dynamic balance between risk sharing and incentive compatibility.

3.2. Game-Theoretic Analysis of Supply Chain Restructuring under Collective Rationality

The supply chain is, in nature, a relational network that enables the division of labour and collaboration within a same industry [

35]. Between the leading firm and its upstream supplier, there is a

co-competition relationship where the parties are mutually dependent, cooperation facilitates coordination and coordination, in turn, stimulates deeper collaboration [

36]. Concurrently, experimental evidence from behavioral economics indicates that, within game-theoretic model, once participants have been adequately trained to comprehend the rules, the extent of cooperation is predominantly governed by social preferences [

37]. Accordingly, in order to realize supply chain restructuring, the analysis must proceed from the perspective of collective rationality, giving priority to the overall returns of all firms in the supply chain and re-examining and optimizing the principles of return and risk sharing among them [

38].

As the leading firm and its upstream suppliers implement supply chain restructuring, the whole supply chain must realise return sharing and risk bearing. This requirement implies that all firms must synchronise actions, thereby incurring additional coordination costs. In certain instances, the leading firm may even need to provide subsidy to upstream supplier that face financial constraints or other hardships [

39]. This paper refers to such costs collectively as the extra costs of supply chain restructuring. From the perspective of the extent to which a firm bears the extra costs of supply chain restructuring, the risk bearing level by an individual firm can be evaluated, thereby further revealing the allocation of risk and return in the context of supply chain restructuring.

3.2.1. Returns When No Firm Bears the Restructuring Risk

When no firm is willing to assume restructuring risks (i.e. the extra costs remain unshared), the paper employs backward induction to analyse the outputs, prices and profits of both the upstream suppliers and the leading firm. The equilibrium results are summarised in

Table 1 and details are provided in

Appendix B.

Under these conditions, the total profit of the supply chain can be expressed as Equation (20).

3.2.2. Returns When the Leading Firm Bears Supply Chain Restructuring Risk

Assume that the leading firm pays the extra cost generated during restructuring and the payment equals the upstream supplier’s effort cost, expressed as , where denotes the effort cost coefficient and denotes the upstream supplier’s effort level. Because this subsidy motivates a higher effort level of upstream supplier, the leading firm’s unit production cost decreases.

To simplify the analysis, it is further assumed that the reduction in cost equals the upstream supplier’s effort level (). Then, the profit of the leading firm can be expressed as .

Regarding the issue discussed above, by Bayes’ rule we yield the following first-order necessary conditions as shown in Equation (21) and Equation (22) and derivation details are provided in

Appendix A.2.

Under these conditions, the total profits of the upstream supplier and the leading firm and the entire supply chain are shown in Equation (23) , Equation (24) and Equation (25), respectively.

From the results of Equation (23) and Equation (24), combined with the data in the third column (Firm Profit) of

Table 2 , it can be seen that when the leading firm undertakes part of the extra costs of supply chain restructuring, both the upstream supplier’s profit and the leading firm’s profit increase, reflecting a significant vertical spillover effect and indicating a potential free-riding tendency on the part of the upstream supplier. Moreover, because the value of

in Equation (25) exceeds that in Equation (20), bearing the supply chain restructuring risk enables the leading firm to enhance overall production capacity and to exploit latent capacity of supply chain, thereby lifting the total profit of the supply chain.

3.2.3. Return under Joint Risk Bearing

Under this conditions, all firms in the supply chain jointly bear the restructuring risk, that is, the leading firm and its upstream supplier share the extra costs required for supply chain restructuring. Supply chain profit is expressed as Equation (26).

By taking the partial derivatives of Equation (26) with respect to

and

and applying the first-order necessary condition, the paper yields Equation (27) and Equation (28). The derivation details are provided in

Appendix A.3.

Substituting Equation (27) and Equation (28) into Equation (26) gives the total supply-chain profit as shown in Equation (29).

From a collective-rationality perspective, once the all firms in the supply chain have assumed the restructuring risk, the resulting changes in supply-chain returns are presented in

Table 3.

In summary, when the leading firm actively assumes the extra costs and provides price subsidies to motivate upstream suppliers and jointly promote supply chain restructuring, the effort level of upstream suppliers increases significantly, the output of the leading firm’s final products rises, and the sum of profits of all firms in the supply chain expands accordingly. However, due to the vertical spillover effect of the extra costs borne by the leading firm, upstream suppliers may exhibit a “free-riding” behavior. Further analysis shows that the total profit obtained when both parties share the restructuring risk in Equation (29) exceeds the profit when only the leading firm bears the risk in Equation (25). Both values are markedly greater than the profit when no firm bears the risk in Equation (20). Risk sharing therefore enhances the stability of supply chain restructuring, strengthens resilience of the supply chain under uncertainty and achieves an efficient Pareto optimality in the supply chain system, thereby improving the allocation of social resources and raising overall social welfare.

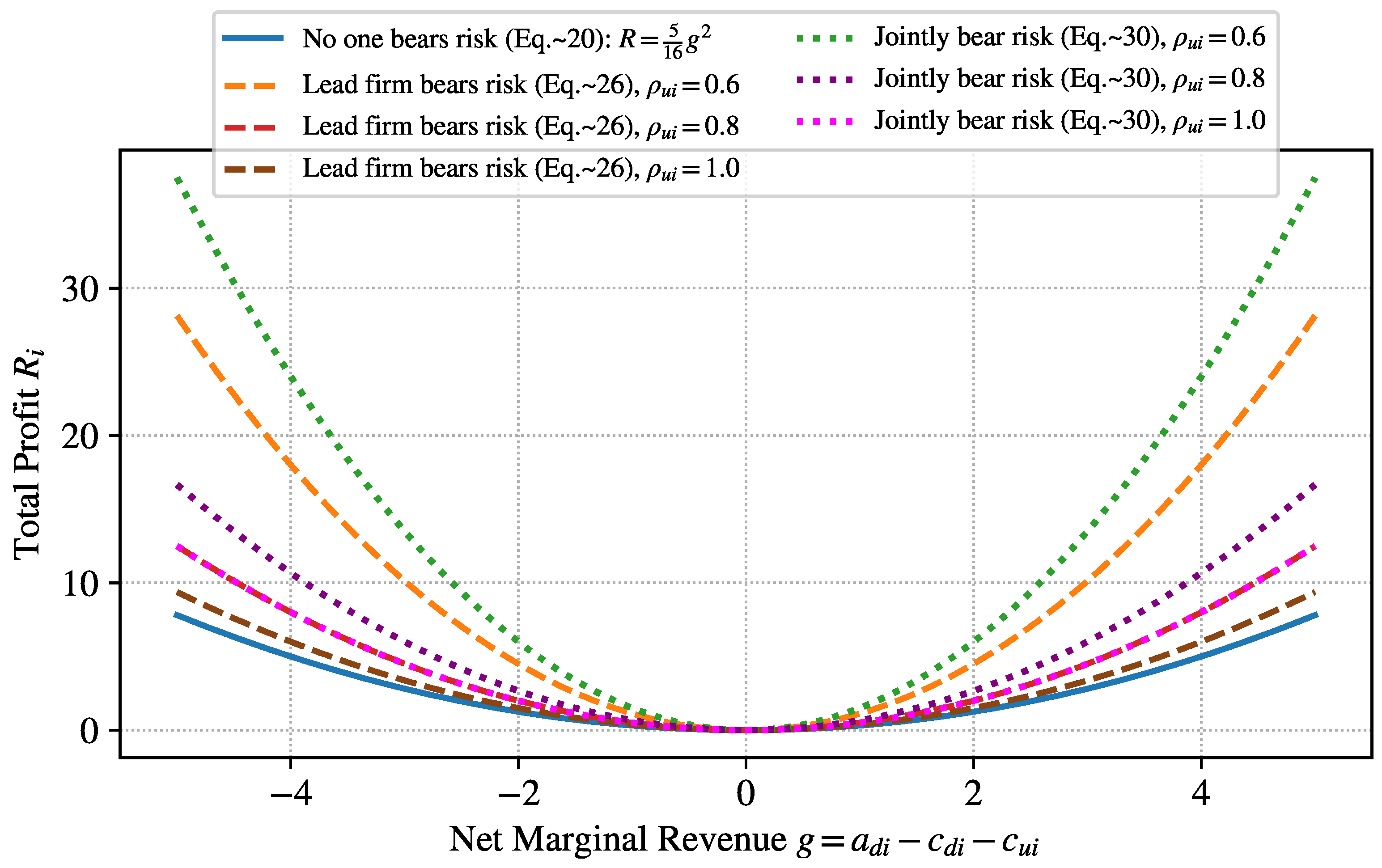

Parameter values used in

Figure 3 are as follows:

=

,

and 1, which correspond to relatively high, high and very high effort costs for upstream suppliers, respectively. Based on simulations conducted by the

MATLAB, based on different levels of upstream supplier’ effort costs, the game-theoretic results between upstream suppliers and leading firms are presented in

Figure 3 .

Figure 3 shows the game trajectories between upstream suppliers and leading firms based on different effort costs of upstream suppliers. When no firm is willing to bear the risk, the overall return of the supply chain is minimized. Conversely, when upstream suppliers have lower effort costs and jointly share risks with leading firms, the return of the supply chain reaches its maximum. The relationship between the effort costs of upstream suppliers and the return of the supply chain is negatively correlated, independent of which firm bears the risk. Given same effort costs for upstream suppliers, the return of the supply chain is greater when both upstream suppliers and leading firms jointly share risks than when the leading firms bear risks alone. Therefore, by reasonably configuring the effort cost coefficients and risk sharing mechanisms, leading firms can not only effectively enhance the effort levels of upstream suppliers but also promote supply chain restructuring.

3.3. Game-Theoretic Analysis of Clustered Supply Chain Restructuring

If force majeure risks lead to supply chain decoupling, leading firms often prefer to cluster in regions where supply chains are relatively mature and well-developed, and collaborate with local related enterprises to reconstruct new supply chain, which in turn leads to supply chain restructuring across regions and across supply chains. Meanwhile, the behavior of leading firms in the non-clustered industrial regions (the transferring region) choosing firms in the clustered industrial regions (the receiving region) for supply chain reconstruction is called cluster-based supply chain reconstruction. Suppose the leading firm in the region where the industry is not clustered (the transferring region) is Firm 1, and the firm in the area where the industry is clustered (the receiving region) is Firm 2.

3.3.1. Inter-firm Game within Clustered Supply Chain Restructuring

It is assumed that Firm 1 and Firm 2 face two strategic options when confronted with government policies in response to such risks: to participate in cluster-based supply chain restructuring or not to participate (i.e., to cooperate or not to cooperate). At the same time, both the enterprises involved in the game are regarded as rational economic individual.

Let firm be indexed by i, and parameter denotes the cooperation cost of firm i, where follows the cumulative distribution with strictly positive density and where and are independent. Accordingly, Firm 1 chooses to cooperate with probability , and not to cooperate with probability ; similarly, Firm 2 chooses to cooperate with probability , and not to cooperate with probability .

- (1)

Single firm cooperation. If only one firm cooperates (i.e. only Firm 1 or Firm 2 participates in supply chain restructuring when force majeure risks occur), the cooperating firm’s profit is , while the non-cooperating firm’s profit is zero.

- (2)

Joint cooperation. If both Firm 1 and Firm 2 cooperate (both enterprises participate jointly), each cooperating firm earns .

- (3)

No cooperation. If neither Firm 1 nor Firm 2 participates in supply chain restructuring, both profits are zero and the parameters satisfy the condition, namely, .

On the basis of standard equilibrium theory, the corresponding return matrix under force majeure risks can be constructed and reported in

Table 4.

Against the backdrop of force majeure risks that necessitate supply chain restructuring through industrial transfer, Firm 1 and Firm 2 must both choose to cooperate (i.e., jointly participate in the restructuring) to achieve effective supply chain restructuring [

40]. According to the Bayes–Nash equilibrium rule, the condition for cooperation between Firm 1 and Firm 2 is expressed as Equation (30).

Meanwhile, when implementing cluster-based supply chain restructuring across regions, Firm 1 and Firm 2 are located in different regions. The local business environment directly affects the cost of firms to participate in supply chain restructuring, which implies that a favorable business environment can reduce the cost of participation, while an unfavorable one increases it. Accordingly, it is assumed that in regions with an optimized business environment, the cost of supply chain restructuring for leading firms is reduced by

, whereas

denotes the penalty imposed on leading firms that undermine the local business environment. If firms inflict relatively little damage on the local business environment, then

is relatively small. Otherwise, it is relatively large, with the constraint

being satisfied [

41].

Given these assumptions, the return matrix for supply chain restructuring across regions between Firm 1 and Firm 2 is presented in

Table 5.

According to game-theoretic theory, the expected return to Firm 1 from choosing cooperation and non-cooperation are expressed as Equation (31) and Equation (32), respectively.

According to Equation (31) and Equation (32), it follows that

. In this case, Firm 1 adopts the cooperation strategy. The expected return of Firm 2 are expressed as Equation (33) and Equation (34).

According to Equation (33) and Equation (34), it follows that . In this case, Firm 2 adopts the cooperation strategy.

To safeguard supply chain stability and security against force majeure risks and other external shocks and to achieve cluster-based supply chain restructuring across regions, both Firm 1 and Firm 2 must cooperate, that is, participate jointly in the restructuring. On the basis of the foregoing analysis, the threshold conditions under which Firm 1 and Firm 2 both choose cooperation can be expressed as Equation (35).

Equation (35) indicates that successful cluster-based restructuring requires the cooperation of both Firm 1 and Firm 2. Subject to each party’s cooperation cost constraint, it is theoretically possible to obtain a unique Bayesian–Nash equilibrium for cooperation in cluster-based supply chain restructuring across regions. Moreover, Equation (35) further implies that:

- (1)

The cooperation strategy of Firm 1 is influenced by the probability that Firm 2 chooses cooperation. Conversely, the cooperation decision of Firm 2 is also affected by the probability that Firm 1 chooses cooperation.

- (2)

The probability of mutual cooperation is positively correlated with the weighted average of the following factors, including equilibrium profits of supply chain restructuring (), the equilibrium profit of Firm 1 () and the equilibrium profit of Firm 2 ().

- (3)

The probability of the cooperation directly determines the level of cost sharing between the two parties in participating in cluster-based supply chain restructuring.

Whether Firm 1 or Firm 2, its cooperation probability is mainly influenced by the following three factors: (i) the cost of participation, (ii) the policy incentive concerning supply chain transfer and restructuring in both regions and (iii) the height of market barriers in both regions.

Information asymmetry between Firm 1 and Firm 2 may yield a lemons market phenomenon, generating mismatches between the two parties in supply chain restructuring. At the same time, driven by the objective of maximizing local interests, local governments often restrict the outward industry transfer under force majeure risks, leading to severe market segmentation across regions and particularly high market entry barriers at the inter-provincial level. Therefore, under force majeure risks, the economic recovery necessitates supply chain restructuring, so it is also necessary to conduct further game-theoretic analysis from the perspective of local government behavior in order to more comprehensively depict the mechanisms through which policy and market factors influence cluster-based supply chain restructuring.

3.3.2. Intergovernmental Game in Cluster-Based Supply Chain Restructuring

When confronted with force majeure risks, local governments in different regions may choose either to cooperate or not to cooperate. The return structure is defined as follows: if both governments choose to cooperate, each obtains a return of ; if one chooses to cooperate while the other does not, then the cooperating party receives a return of and the non-cooperating party receives a return of ; if both choose not to cooperate, i.e., they compete with each other, then each obtains a return of . Moreover, suppose the return satisfy , indicating that non-cooperation yields short-term advantages, whereas cooperation is conducive to long-term stable development.

1. Game-theoretic Analysis of Supply Chain Restructuring under Perfect Competition

(1) When the two local governments engage in a single round game When the two governments engage in a single round game, the return matrix is given in

Table 6.

As

Table 6 indicates, the single round game satisfies

. Hence, non-cooperation yields a higher short-term return. Accordingly, the government in the transferring region may, after the occurrence of force majeure events, sets up various policy barriers to protect local economic interests and thereby raise the cost of industrial transfer. Meanwhile, the government in the receiving region may, due to insufficient evaluation of or lack of incentives for incoming industries, fail to effectively attract industrial transfer. Such a non-cooperative tendency traps both governments in a “prisoner’s dilemma”, causing supply chain restructuring across regions to stall.

Moreover, the evident opportunistic behavior of local governments undermines the efficiency of resource allocation across regions, thereby hindering the optimization of national overall welfare. Therefore, it is necessary to incorporate repeated game theory to rectify local governments’ cognition regarding the long-term expected returns of industrial restructuring. In reality, the outcomes of supply chain restructuring can only be verified over time, and shocks from force majeure risks to supply chains typically exhibit time-lagged effects.

(2) Infinitely repeated game between governments Given the long-term coexistence of the two regions, the interactions between local governments are more appropriately modeled as

infinitely repeated game. If, in a given period, one local government chooses not to cooperate, it obtains a short-term return of

. However, such behavior will trigger a retaliatory strategy from the other local government in the next period, namely, also choosing not to cooperate. As a result, both parties will refrain from cooperation in all subsequent periods, that is, when force majeure risks occur, neither governments in the transferring region and the receiving region will participate in supply chain restructuring, and each will receive a return of

in every period. Parameter

denote the common discount factor that reflects how much each government values future return. When a local government persistently adopts a non-cooperative strategy, it reflects a stronger preference for short-term return, that is, a lower discount factor (

), thereby impeding supply chain restructuring. Accordingly, the expected return of the non-cooperative strategy is illustrated in Equation (36).

If both local governments persistently adopt cooperative strategies, that is, both actively promote supply chain restructuring under risk shocks, then each obtains a per-period return of

, and the expected return from the cooperative strategy is therefore illustrated in Equation (37).

Under force majeure risks, effective supply chain restructuring requires coordinated policy and cooperation between the governments in the transferring region and the receiving region, which requires

, yielding the critical discount factor as shown in Equation (38).

Equation (38) shows that, when governments in the transferring region and the receiving region allow an orderly industry transfer under force majeure risks and jointly adopt the cooperative strategy to participate in supply chain restructuring, a Pareto improvement will be achieved. Under these circumstances, the minimum discounted return () is optimised. The admissible range of is jointly determined by the two governments’ return under cooperation and non-cooperation. In other words, the higher the returns obtained under non-cooperation, the smaller the likelihood of a successful industrial transfer, and consequently, the fewer opportunities for supply chain restructuring across regions. Therefore, to achieve coordinated optimization of regional economic returns, all parties involved in industrial transfer should place greater emphasis on the benefits of cooperation. In particular, for the governments of both transferring and receiving regions, adopting coopertive strategies not only helps to reduce systemic barriers caused by risk shocks but also contributes to the long-term stability of regional economic development. Accordingly, it is essential to establish appropriate incentive mechanisms to guide and support both transferring and receiving governments to proactively engage in cooperation when facing major risks.

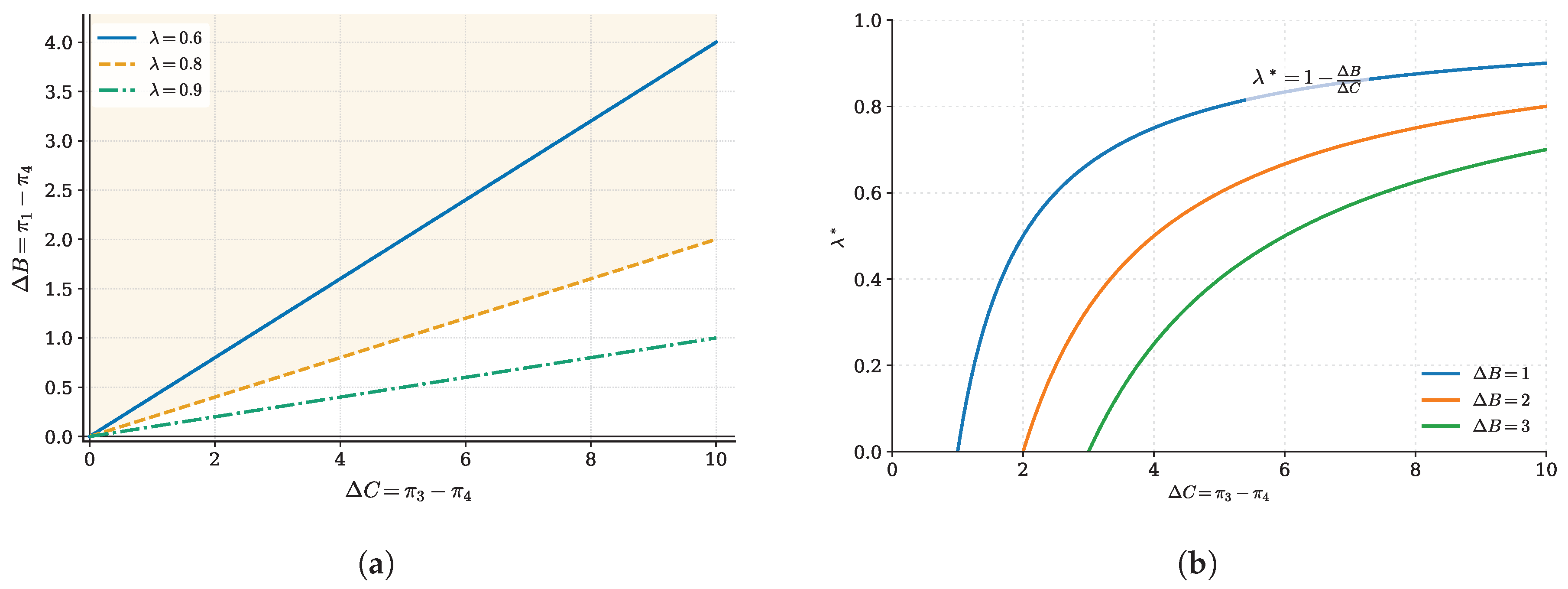

Parameter values used in the following

Figure 4 are as follows:

=

,

and

, which correspond to relatively high, high and very high degrees of government emphasis on future benefits, respectively. Parameter

= 1, 2 and 3, representing low, medium and high differences in supply chain return when the transferring and receiving governments both choose cooperation versus non-cooperation. Based on simulations conducted by the

MATLAB,

Figure 4 illustrates the game outcomes between upstream suppliers and leading firms, given different degrees of government emphasis on future return and varying return differentials arising from decisions of cooperative and non-cooperative supply chain restructuring by the transferring and receiving governments.

Figure 4 reveals the game trajectories between upstream suppliers and leading firms based on varying degrees of governmental emphasis on future return.

Figure 4a demonstrates that the larger the return differential between cooperation and non-cooperation for either the transferring or the receiving government, the greater the corresponding return differential when both governments simultaneously choose cooperation or non-cooperation. Moreover, the greater the weight the government places on future return, the more likely both governments in the transferring region and the receiving region are to cooperate in supply chain restructuring.

Figure 4b shows that with a larger return differential between cooperation and non-cooperation in supply chain restructuring, both governments in the transferring region and the receiving region are less likely to support supply chain restructuring simultaneously. Hence, a higher degree of cooperative willingness combined with smaller return differentials is more favorable for supply chain restructuring, which in turn improves synergistic effects and systemic efficiency of the supply chain restructuring.

2. Inter-governmental Game under a Central Government Intervention Mechanism

In order to guard against rent-seeking and corruption induced by policy opacity or information asymmetry during supply chain restructuring, it is necessary, under force majeure risks, to introduce the central government as a third party intervenor. By providing time-bounded incentives that encourage local governments to adopt cooperative strategies, the central government can promote the smooth and orderly industry transfer and thus realize collaborative supply chain restructuring across regions.

To strengthen the motivation for local governments to engage in mutually beneficial cooperation, it is assumed that the central government grants a reward ratio to those local governments that adopt supportive industrial transfer policies, whether in transferring or receiving regions, such that their cooperative return equals times the original return. Conversely, for local governments that restrict industrial transfer and thereby impede supply chain restructuring, the central government imposes punitive interventions, applying a penalty ratio, such that the return is reduced to times the original return, where .

Based on the foregoing assumptions,

Table 7 presents the return matrix of the game between local governments under the intervention mechanism.

As shown in

Table 7, when the reward coefficient and the penalty coefficient satisfy certain conditions, namely when condition

holds, cooperation becomes the dominant strategy for both the governments in the transferring region and the receiving region. This, in turn, induces benign interaction between the two parties within a finite period and helps to avoid the return disadvantages of non-cooperation. If a government opts for non-cooperation, then a higher original return (

) entails a higher penalty (

). Conversely, if a government chooses cooperation, then a higher original return (

) yields a greater reward (

).

Hence, by introducing a performance-based reward and penalty mechanism, the central government can effectively steer local governments towards cooperation during industrial transfer, thereby improving overall resource allocation efficiency and enhancing the digitalisation, resilience and sustainability of the supply chain restructuring.

In sum, the introduction of a central government–led incentive and constraint mechanism can effectively coordinate the competition and cooperation among local governments during the process of supply chain restructuring across regions, thereby maximizing overall system return. Once the reward or penalty coefficient reaches a critical threshold, the probability of local governments to adopt cooperative strategies within a finite period will substantially increase, thus providing institutional guarantees for effective supply chain restructuring.

3.3.3. Co-competition Game Analysis in Cluster-Based Supply Chain Restructuring

Assume the Parameter of market’s total demand is a constant

q and that the market clears completely. Under these assumptions, the market prices of the intermediate goods and final goods follow linear inverse demand functions as illustrated in Equation (39).

where

and

represent the substitution rates of intermediate goods and final goods, with

. Given the structural differences discussed above between the regions in which cluster-based and non-cluster supply chains operate, the unit cost is

for Firm 2 and

for Firm 1. Here,

denotes the general total cost of firms in the supply chain that are not affected by force majeure risks, while the parameters

and

represent, respectively, the

incremental impact coefficients of Firm 1 and Firm 2 under the force majeure risks. Given that such risks will raise firms’ production costs, it is assumed that

and

. Compared with Firm 1, clustering reduces the costs of firms in supply chain. Thus, assume that

, which implies that

. Under these conditions, the optimal output conditions for profit maximization of Firm 1 and Firm 2 are, respectively, illustrated in Equation (40).

Cooperation and competition across supply chains refer to the process whereby Firm 1 collaborate with Firm 2 to jointly confront competition from leading firms in heterogeneous supply chains, thereby giving rise to cooperation and competition across chains on a broader scale [

42]. This relationship between cooperation and competition is primarily manifested in the interactions between Firm 1 and Firm 2, encompassing both cooperation and competition, and constitutes a new form of industrial organization behavior under the coexistence of multiple supply chains.

In an environment characterized by high uncertainty and frequent unexpected risks, Firm 1 often choose to transfer to regions with industrial cluster advantages in order to enhance their resilience against external shocks. During the transfer process, these firms interact with Firm 2, which are spatially concentrated and closely industrial linked, thereby generating cooperation and competition across supply chains. Through such interactions across supply chains, different supply chains gradually establish a synergistic mechanism, thereby driving the structural restructuring of clustered supply chains.

Therefore, from the perspective of co-competition model across supply chains, the paper systematically analyses the restructuring mechanism of clustered supply chains within both cooperative and non-cooperative game frameworks so as to through comparison reveal that cooperation and competition across supply chains between Firm 1 and Firm 2 contributes to mitigating force majeure risks and other unexpected risks, thereby enhancing their risk resilience and strengthening the overall resilience of the supply chain.

1. Non-cooperative Game-theoretic Analysis of Cluster-based Supply Chain Restructuring

When Firm 2 fail to cooperate with Firm 1, structural restructuring of the supply chain cannot be achieved, so the two sides engage in a

Cournot-type non-cooperative game. In the game-theoretic model, substituting Equation (39) into Equation (40), differentiating each firm’s profit function and setting the first-order necessary conditions to zero and then solving the system simultaneously will yield the Nash-equilibrium profits of the two parties under non-cooperation, as illustrated in Equation (41).

2. Cooperative Game-theoretic Analysis in Cluster-based Supply Chain Restructuring

When Firm 1 and Firm 2 reach a cooperation agreement and jointly commit to supply chain restructuring across supply chains, the two parties enter into a cooperative game framework. The condition for the cooperative game [

43] can be expressed as Equation (42).

Equation (42) indicates that when Firm 1 and Firm 2 successfully reach a cooperation agreement, i.e., when the cooperation condition is satisfied, cross-chain integration can be achieved through resource synergy and complementarity. This, in turn, promotes supply chain restructuring and yields a Pareto improving optimal outcome, namely, at least one party’s return increases without reducing that of the other.

3. Comparative Static Analysis of Non-cooperative vs Cooperative Scenarios in Cluster-based Supply Chain Restructuring

Based on the assumptions of the relevant variables and parameters in the aforementioned model, the paper can prove that . It therefore reveals that , which implies that the equilibrium profit of Firm 2 is markedly higher than that of Firm 1 in Equation (41). Moreover, Equation (42) reveals that, during cooperative supply chain restructuring, the sum of cooperative equilibrium profits earned by Firm 1 and Firm 2 exceeds the sum of their respective profits under the non-cooperative scenario. Therefore, for each leading firm in the supply chains, the profit obtained under cooperation exceeds that achieved in the non-cooperative setting. Hence, supply chain restructuring across regions is a pronounced win–win cooperation, achieving a Pareto improvement, effectively promoting the shift of supply chains from competition-oriented to collaboration-oriented modes and facilitating the industry’s overall advancement to higher tiers.

In summary, the paper reveals that Firm 1, by participating in cluster-based supply chain restructuring across supply chains, can not only effectively mitigate external risks such as force majeure risks, but also achieve structural upgrading, value enhancement and improved risk resilience through cooperation, thereby laying the foundation for a more resilient, sustainable and digitalized supply chain system.

4. Discussion

This paper is conducted from a return and risk perspective and it employs principal agent theory and game-theoretic model to analyze the logic and mechanism design of supply chains restructuring under uncertainty. Building on the preceding analysis, several findings warrant further discussion:

First, the choice of risk sharing mechanism directly affects both the resilience of the supply chain and its overall profit level. The results indicate that when no party undertakes the risk, the supply chain is in the least favorable state. If the risk is borne solely by the leading firm, profits rise significantly. However, vertical spillovers in incentives and the “free-riding” phenomenon emerge. By contrast, when upstream supplier and downstream leading firm bear risks jointly, the supply chain achieves the highest profit level, approaching a Pareto-optimal outcome, which indicates that a well-designed risk sharing mechanism not only mitigates moral hazard but also strengthens long-term supply chain stability.

Second, differences in effort costs and risk aversion determine the effectiveness of incentive mechanisms. The results demonstrate that as the effort cost coefficient of upstream suppliers increases, both their risk sharing cost and the incentive cost of the leading firm decline significantly. However, the sensitivity to varying degrees of risk aversion differs, that is, firms with higher risk aversion rely more heavily on additional incentives to sustain cooperation. Therefore, regarding mechanism design, it is essential to incorporate both suppliers’ risk preferences and effort levels, so as to avoid incentive insufficiency or resource misallocation resulting from reliance on a single incentive mechanism.

Third, cluster-based supply chain restructuring constitutes an effective approach to enhancing system robustness. The paper demonstrates that cluster-based firm, when confronted with force majeure risks shock, can achieve significant win-win outcomes through collaboration and resource sharing across supply chains. Compared with non-clustered supply chains, cluster-based supply chains yield higher equilibrium profits and exhibit stronger risk resilience, which implies that, against the backdrop of global industrial chain restructuring, promoting regional cluster and cross-chain coordination of supply chains will become a key strategic direction for enhancing industrial competitiveness.

Fourth, the government plays a pivotal regulatory role in supply chain restructuring across regions. Further analysis indicates that when the central government intervenes in local government games through reward and penalty mechanism, it can effectively correct the short-term opportunism of local authorities and promote both the orderly transfer of industries across regions and the coordination of supply chains. Therefore, institutional design and policy instruments are not merely external constraints but also function as institutional safeguards for advancing the digitalization, resilience and sustainable development of supply chains.

In sum, this paper not only enriches the theoretical framework of supply chain restructuring but also offers the following practical implications. First, at the firm level, attention should be paid to designing risk sharing mechanism and incentive mechanism. Second, at the regional level, efforts should focus on promoting cluster and cross-chain collaboration. Third, at the policy level, institutional incentives should be employed to coordinate the behavior of local governments and firms. Future research could further incorporate empirical data to calibrate parameters and explore new mechanisms and models of supply chain restructuring in the context of digitalization and artificial intelligence.

5. Conclusions

Grounded in a return and risk perspective and a supplier–leading firm model, the paper constructs a game-theoretic model to systematically examine how leading firms can achieve effective game-theoretic strategies for supply chain restructuring when facing the decoupling or breakage of the supply chain triggered by force majeure risks. The findings suggest, First, under conditions of information asymmetry and incentive incompatibility, supply chain restructuring may give rise to moral hazard on the part of upstream supplier, thereby undermining the operational efficiency of the entire supply chain. Second, as the risks of supply chain restructuring increase, both leading firm and upstream supplier face rising costs. If upstream supplier chooses to avoid risks and reduces effort levels, the risks it bears and incentive costs decline accordingly. However, it also reduces the returns of leading firms and undermines overall collaborative performance of the supply chain. Third, when leading firms proactively adopt incentive mechanisms such as subsidies to enhance the effort level of upstream supplier, final product output and overall supply chain profits increase. However, because incentive mechanisms generate vertical spillover effects, “free-riding” behavior among upstream supplier may be induced, thereby undermining the stability of incentive effect. Fourth, when leading firms and upstream suppliers share the risks of supply chain restructuring, the total profit achieved is significantly higher than that when the risk is borne solely by the leading firm. This mechanism contributes to enhancing system robustness, brings the outcome closer to Pareto efficiency and effectively improves resource allocation efficiency and social welfare. Fifth, supply chain restructuring across supply chains represents a win–win mechanism that promotes the overall profit growth of both existing and new supply chains, achieves Pareto improvement, and facilitates the evolution of industrial value chains toward higher stages. Sixth, whether firms participate in cluster-based supply chain restructuring strategically depends on their perceived probability of other participants’ behaviors, and is also closely related to the quality of the business environment in the clustered region and the degree to which firms comply with institutional norms. Seventh, by imposing appropriate constraint mechanisms on participating firms, positive feedback can be generated to enhance the security and stability of supply chains, thereby fostering the construction of a more collaborative, resilient and sustainable supply chain system. In sum, grounded in Game Theory and incentives mechanism and leveraging the game interactions that arise when a leading firm and upstream suppliers restructe the supply chain, this paper reveals the internal mechanisms through which leading firms, when confronted with major risk shocks, can play a dominant role in driving supply chain restructuring. The findings provide strong theoretical support and practical insights for enhancing the resilience, coordination and sustainability of supply chain systems in the context of digitalization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Z.X.; H.H.T.; methodology, H.H.T.; validation, H.H.T.; W.W.J.; formal analysis, H.H.T.; investigation, H.H.T.; W.W.J.; S.D.W.; data curation, H.H.T.; S.D.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.H.T.; writing—review and editing, H.H.T.; W.W.J.; supervision, F.Z.X.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [National Key Research and Development Program of China] under the project “[Research, Development and Application of Cross-border Trade Collaborative Service Technology]” (grant number [2022YFF0903400]). The APC was funded by the first author, Huiting Hua.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| IR Constraint |

Individual Rationality Constraint |

Appendix A. Derivation of Equation

Appendix A.1. Derivation of Equation (17)

Appendix A.2. Derivation of Equation (21) and Equation (22)

Starting from

, the Equation (21) and Equation (22) can be derived as follows.

.

Substituting

into

yields Equation (1).

Differentiating Equation (1) with respect to

and setting it to zero yields Equation (2).

Differentiating Equation (1) with respect to

and setting it to zero yields Equation (3).

Substituting Equation (2) into Equation (3) yields Equation (4).

Assume the upstream supplier’s price for the intermediate goods is fixed. Substituting

into Equation (4) yields Equation (5).

Substituting Equation (5) into Equation (2) yields the following result.

Appendix A.3. Derivation of Equation (27) and Equation (28)

Differentiating

with respect to

and solving the first-order necessary condition, Equation (1) will be obtained.

Differentiating

with respect to

and solving the first-order necessary condition, Equation (2) will be obtained.

By jointly solving Equation (1) and Equation (2), the following result will be obtained.

Appendix B. Derivation of Table 1 Result

Assume that when a downstream manufacturer (the

leading firm indexed by

) needs to purchase one unit of intermediate goods from an upstream supplier (

) to produce one unit of the final product. To secure a stable supply of the intermediate goods, the leading firm establishes a long-term partnership with the upstream supplier, who commits to providing a long-term supply of intermediate goods at a fixed price (

) to it.The market demand curve for the final goods is

If the leading firm’s marginal production cost is

, its profit is

For analysis, assume the upstream supplier’s marginal cost is

, so its profit is

Here,

indexes any supply chain, and

n denotes the number of supply chains in the region.

Differentiating Equation (1) and setting the result to zero yields Equation (2).

Substituting Equation (2) into

yields Equation (3).

Differentiating Equation (3) and setting the result to zero yields Equation (4).

Substituting Equation (4) into Equation (2) yields Equation (5).

Substituting Equation (5) into

gives Equation (6).

Substituting Equations (4)–(6) into

yields Equations (7).

Substituting Equation (4) and Equation (5) into

yields Equation (8).

References

- Li, J.; Gao, C.; He, Z. Exploring the Path of Industrial Chain Security under the New Development Pattern: A Perspective of Supply and Demand Risk Diversification [in Chinese]. China Industrial Economics 2023, 40, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J. Global Value Chain Restructuring: Opportunities and Choices Facing China [in Chinese]. People’s Tribune 2020, pp. 8–11. Issue No. 670; In Chinese.

- Zhang, W.Y. Game Theory and Information Economics [in Chinese]; Gezhi Chubanshe; Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe [in Chinese]: Shanghai, 2012. Reprinted in March 2019.

- Holmstrom, B.; Milgrom, P. Aggregation and Linearity in the Provision of Intertemporal Incentives. Econometrica 1987, 55, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y.; Rui, M.J. Value Network Reconstruction, Division of Labor Evolution, and Industrial Structure Optimization [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Gongye Jingji [China Industrial Economics] [in Chinese] 2012, 30, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.G.; Xu, Y.M.; Shen, H. The Impact of Supply Chain Dynamic Capabilities on the Implementation of Management Innovation under Turbulent Environments [in Chinese]. Guanli Xuebao [Journal of Management] [in Chinese] 2021, 18, 1714–1720. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.; Zhang, Y. Challenges, Opportunities, and Countermeasures Faced by China under the Trend of Global Value Chain Reconstruction [in Chinese]. China Economist [in Chinese] 2021, 16, 132–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Transformation of supply chain resilience research through the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Production Research 2024, 62, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, A.; Durach, C.F. Two perspectives on supply chain resilience. Journal of Business Logistics 2021, 42, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.S. Perspectives in supply chain risk management. International Journal of Production Economics 2006, 103, 451–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, T.J.; Fiksel, J.; Croxton, K.L. Ensuring supply chain resilience: Development of a conceptual framework. Journal of Business Logistics 2010, 31, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.J. Reconstruction of Circulation Organization in the Internet Era: A Reverse Supply Chain Integration Perspective [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Gongye Jingji [China Industrial Economics] [in Chinese] 2015, 33, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.H. Trends and Key Influencing Factors of Global Industrial Chain Reconstruction [in Chinese]. Renmin Luntan · Xueshu Qianyan [People’s Tribune · Academic Frontier] [in Chinese] 2022, pp. 32–40. In Chinese. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.Y.; Liu, H.J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.Y. Enterprise Digital Transformation and Export Supply Chain Uncertainty [in Chinese]. Shuliang Jingji Jishu Jingji Yanjiu [Journal of Quantitative and Technical Economics] [in Chinese] 2023, 40, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D. Strategic Choices for Achieving High-Level Opening-Up in China under the Background of Global Value Chain Reconstruction [in Chinese]. Jingjixuejia [The Economist] [in Chinese] 2023, pp. 15–24. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.X. AI-Driven Supply Chain Transformation: Platform Reconstruction, Ecosystem Reshaping, and Advantage Rebuilding [in Chinese]. Dangdai Jingji Guanli [Contemporary Economic Management] [in Chinese] 2023, 45, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Mak, S.; Minaricova, M.; Brintrup, A. On Implementing Autonomous Supply Chains: a Multi-Agent System Approach. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2310.09435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.P. Research on Mitigating Supply Chain Vulnerability and Strategies for Independent Control in China [in Chinese]. Dangdai Jingji Guanli [Contemporary Economic Management] [in Chinese] 2021, 43, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zhao, L. Prospects for Japan-India Economic Cooperation under the Background of Global Supply Chain Reconstruction [in Chinese]. Xiandai Riben Jingji [Modern Japanese Economy] [in Chinese] 2022, 41, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Z. Global Supply Chain Reconstruction from a Geopolitical Economy Perspective [in Chinese]. Shijie Jingji yu Zhengzhi Luntan [Forum of World Economics and Politics] [in Chinese] 2024, pp. 48–67.

- Li, S.C.; Ge, S.Q.; Li, C.C. China–US Competition and "Third Country" Trade: On the Reconstruction of Key Industry Chains of New Quality Productive Forces [in Chinese]. Guoji Maoyi [International Trade] [in Chinese] 2024, pp. 30–40. [CrossRef]

- Cachon, G.P.; Lariviere, M.A. Supply Chain Coordination with Revenue-Sharing Contracts: Strengths and Limitations. Management Science 2005, 51, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal Partyka, R. Supply chain management: an integrative review from the agency theory perspective. Revista de Gestão 2022, 29, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.; Guerrini, L.; Dörfler, F.; Liao-McPherson, D. Receding Horizon Games for Modeling Competitive Supply Chains. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.09853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Clusters and the New Economics of Competition. Harvard Business Review 1998, 76, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Buciuni, G.; Pisano, G. Knowledge Integrators and the Survival of Manufacturing Clusters. Journal of Economic Geography 2018, 18, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R. The Impact of Industrial Clusters on Supply Chain Resilience: The Moderating Role of Supply Chain Concentration. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences 2024, 95, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, M.; Chen, G.; Tilbury, D.M.; Shen, S.; Barton, K. A model-based multi-agent framework to enable an agile response to supply chain disruptions. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 18th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE). IEEE, 2022, pp. 235–241. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Li, Q.Q. Game Analysis of Innovation Alliances between Upstream and Downstream Industrial Chains [in Chinese]. Kexuexue yu Kexue Jishu Guanli [Science of Science and Management of S&T] [in Chinese] 2012, 33, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, R.L.; Ni, X.M. Research on Cooperation Models of Financial Institutions Based on the Principal–Agent Model [in Chinese]. Shanxi Daxue Xuebao (Zhexue Shehui Kexue Ban) [Journal of Shanxi University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition)] [in Chinese] 2018, 41, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C. Dynamic Incentives and Optimal Health Insurance Payment Methods [in Chinese]. Jingji Yanjiu [Economic Research Journal] [in Chinese] 2017, 52, 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, Y.S.; Chen, X.; Yang, T.J.; Lu, X.M. Relational Games, Reputation Accumulation, and the Transformation of Start-Ups: A New Perspective on the Economic Functions of Informal Finance [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Gongye Jingji [China Industrial Economics] [in Chinese] 2018, 36, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xie, Y.W.; Song, N.X.; Du, X.J. Research on Contract Coordination of Risk Sharing in Closed-Loop Supply Chains Based on Principal–Agent Theory [in Chinese]. Xitong Kexue Xuebao [Journal of Systems Science] [in Chinese] 2019, 27, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, H.H. Does Contract Incompleteness Necessarily Lead to Investment Inefficiency? A Hold-Up Model with Asymmetric Information [in Chinese]. Jingji Yanjiu [Economic Research Journal] [in Chinese] 2008, pp. 132–143.

- Wu, J.M.; Shao, C. Research on the Formation Mechanism of Industrial Chains: The "4+4+4" Model [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Gongye Jingji [China Industrial Economics] [in Chinese] 2006, pp. 36–43. [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, C.; Deng, C.; Geng, H.J. Innovation Response Strategies of Chain-Leading Enterprises to Policy Changes under Technological Pressure: A Longitudinal Case Study of BYD [in Chinese]. Guanli Shijie [Management World] [in Chinese] 2025, 41, 170–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Niu, X.; Wang, Y. Confusion cannot explain cooperative behavior in public goods games. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121, e2310109121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.L. The Distribution of Internal Power of Enterprises under the Framework of Cooperative Game [in Chinese]. Jingji Yanjiu [Economic Research Journal] [in Chinese] 2009, 44, 106–118. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, J.; Moeller, S. Chain liability in multi-tier supply chains? Responsibility attributions for unsustainable supplier behavior. Journal of Operations Management 2014, 32, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunford, M. Industrial Districts, Magic Circles, and the Restructuring of the Italian textiles and clothing chain. Economic Geography 2006, 82, 27–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.R.; Zhu, B.E. Demand Fluctuations, Business Environment, and Firms’ R&D Behavior: Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta [in Chinese]. Beijing Gongye Daxue Xuebao (Shehui Kexue Ban) [Journal of Beijing University of Technology (Social Sciences Edition)] [in Chinese] 2017, 17, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.S.; Ren, L. From County Competition to County Coopetition: Strategic Choices for High-Quality Development of County Economies [in Chinese]. Gaige [Reform] [in Chinese] 2022, pp. 88–98.

- Tang, X.L.; Li, J. Inter-Chain Cooperative Game Analysis of Cross-Chain Alliances in Supply Chain Clusters [in Chinese]. Keji Jinbu yu Duice [Science & Technology Progress and Policy] [in Chinese] 2008, pp. 90–92.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).