1. Introduction

Mediterranean-type ecosystems are globally recognized for their exceptional biodiversity and high levels of endemism, yet remain among the most threatened biomes due to increasing anthropogenic pressures [

1,

2,

3]. Characterized by a distinctive climate of rainy winters and warm, dry summers, these ecosystems are geographically restricted to five regions aligned across mid-latitudes: the Mediterranean Basin, southwestern Australia, the Cape Floristic Province of South Africa, California, and central Chile [

4,

5].

In the latter, sclerophyllous forests provide the structural and ecological backbone of the landscape, hosting a wide array of woody species whose reproductive strategies are closely shaped by seasonal climate dynamics. Among them, several produce recalcitrant seeds, particularly those belonging to the families Cardiopteridaceae, Lauraceae, and Myrtaceae [

6,

7,

8]. These seeds maintain elevated metabolic activity upon reaching maturity, rendering them highly vulnerable to progressive dehydration and associated subcellular damage, which rapidly compromises their viability [

9,

10]. Given these traits, they are especially susceptible to habitat fragmentation and climatic stressors, underscoring the critical need to address their conservation [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Handling of propagules is fundamental for preserving genetic resources and enabling plant cultivation for habitat restoration [

15,

16]. Numerous studies have explored ecological and phylogenetic patterns underlying seed behavior across plant species, advancing our ability to predict storage responses based on shared traits or evolutionary relationships [

17,

18,

19,

20]. However, the anatomical and physiological changes associated with viability loss over time remain comparatively underexplored, restricting progress toward evidence-based and effective postharvest practices [

21,

22].

The Chilean endemic tree commonly known as peumo (

Cryptocarya alba (Molina) Looser) is one of the dominant and most widely distributed species in sclerophyllous forests [

23,

24], yet the biological basis of its recalcitrant behavior has been insufficiently studied, hindering propagation efforts [

25]. Therefore, to inform better decision-making for their conservation, this study examined the temporal dynamics of structural and metabolic degradation in

C.

alba fruits under contrasting storage conditions.

2. Results

2.1. Fruit Characterization

At collection, fruits had a mean weight of 2.81 ± 0.44 g [1.88-3.67 g], a moisture content of 25 ± 4.0% [23-31%], a length of 1.98 ± 0.17 cm [1.63-2.43 cm] measured along the cotyledonary axis, and a width of 1.67 ± 0.18 cm [1.25-2.22 cm]. Their shape was accurately captured by an ellipse-based equation, which showed a strong fit with the projected area (log-log slope = 0.86, R2 = 0.78, p < 0.001), that averaged 2.64 ± 0.40 cm2 [1.79-3.85 cm2].

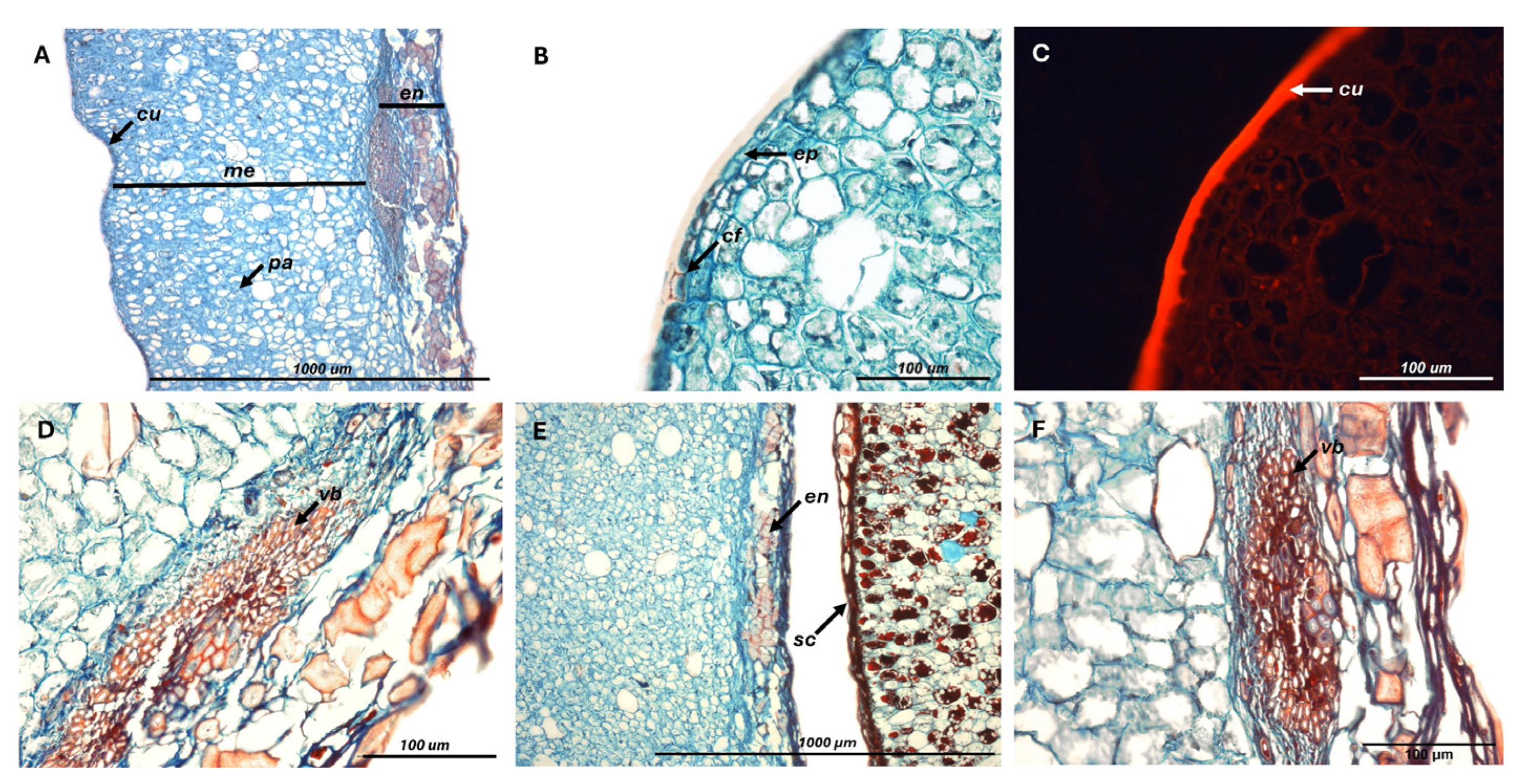

Fruit cuticle measured 9.3 ± 0.9 µm [8.7-10.3 µm], consisting of an outer layer characterized by epicuticular and intracuticular waxes, and an internal one composed of cutin and lignin, which often extended into epidermal cell walls. The mesocarp comprised abundant intercellular spaces surrounded by large parenchymatous cells, irrigated by vascular bundles located near its inner margin. Mesocarp thickness was the most variable among fruit layers (coefficient of variation = 25%), ranging from 795 to 1331 µm (1085 ± 271 µm), and accounting on average for 87% of pericarp thickness. The remaining portion consisted of an endocarp reaching 165 ± 22 µm [146-189 µm], which contributed to tissue rigidity through densely lignified cells oriented in multiple directions (

Figure 1). The cotyledons were composed of storage parenchyma densely packed with starch granules (344 ± 59 granules per 1000 µm

2), which were smooth-surfaced, spherical to slightly oval, and uniformly embedded within the cellular matrix.

2.2. Storage-Induced Breakdown

2.2.1. Weight Loss

There was a significant decline in fruit weight during storage (

p < 0.001), with a more pronounced rate under room temperature compared to refrigeration at 5°C (

p < 0.05). After 150 days, the latter exhibited 73% of the weight loss observed at 20°C, where fruits decreased to 1.76 ± 0.39 g. Including fruit-level variability through a mixed model significantly improved data fit (Δ AIC = 131, LRT

p < 0.001) (

Figure 2).

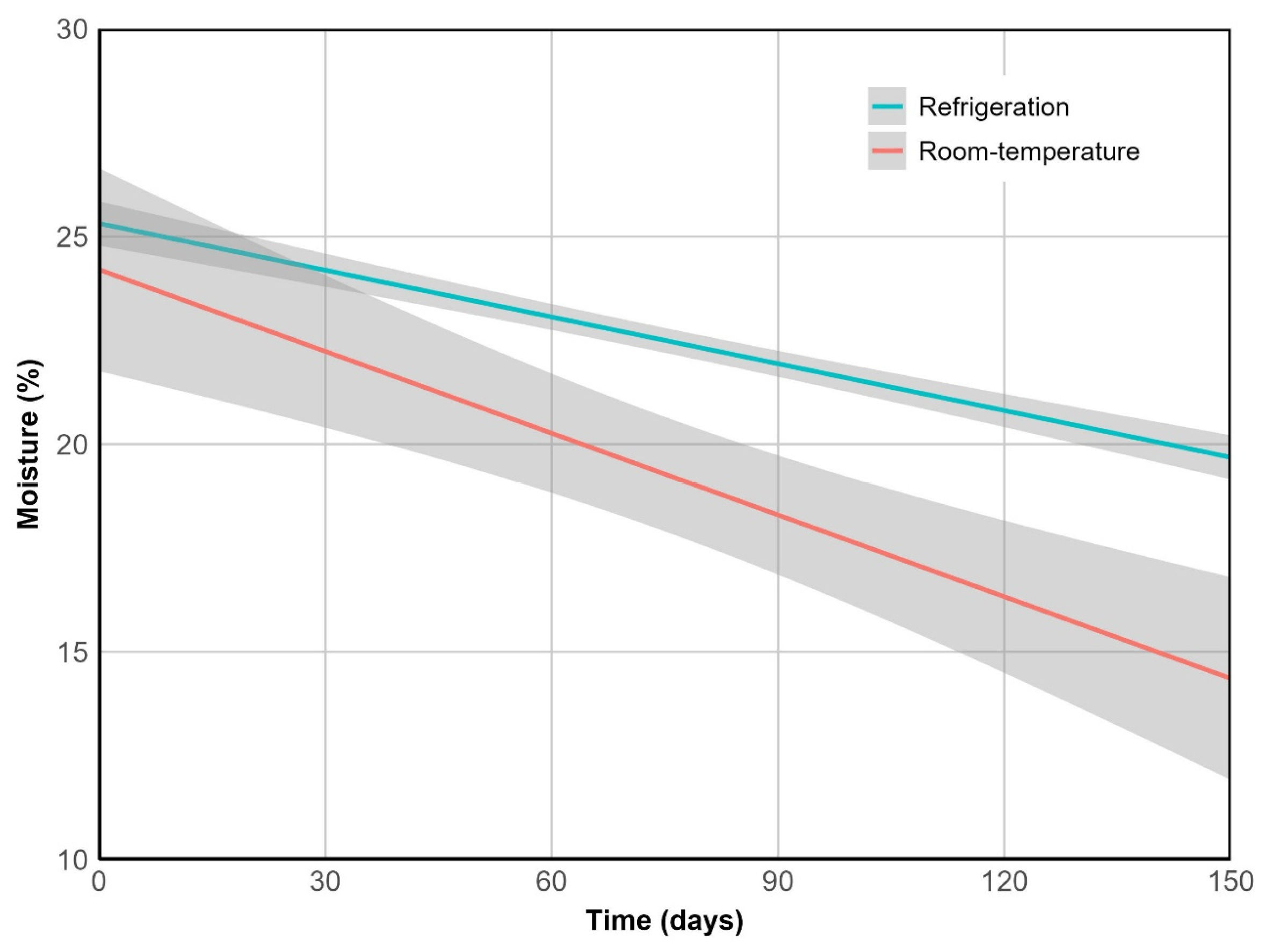

2.2.2. Desiccation

Moisture content was strongly correlated with weight (ρ = 0.96,

p < 0.001) and decreased significantly over time under both storage conditions (

p < 0.001), with a greater decline at 20°C (

p < 0.05). This difference was captured by a 1.75-fold steeper slope in the linear model (

Figure 3), and by a reduction in measured values from 25% to 14% at room temperature, compared to a final moisture content of 20% under refrigeration.

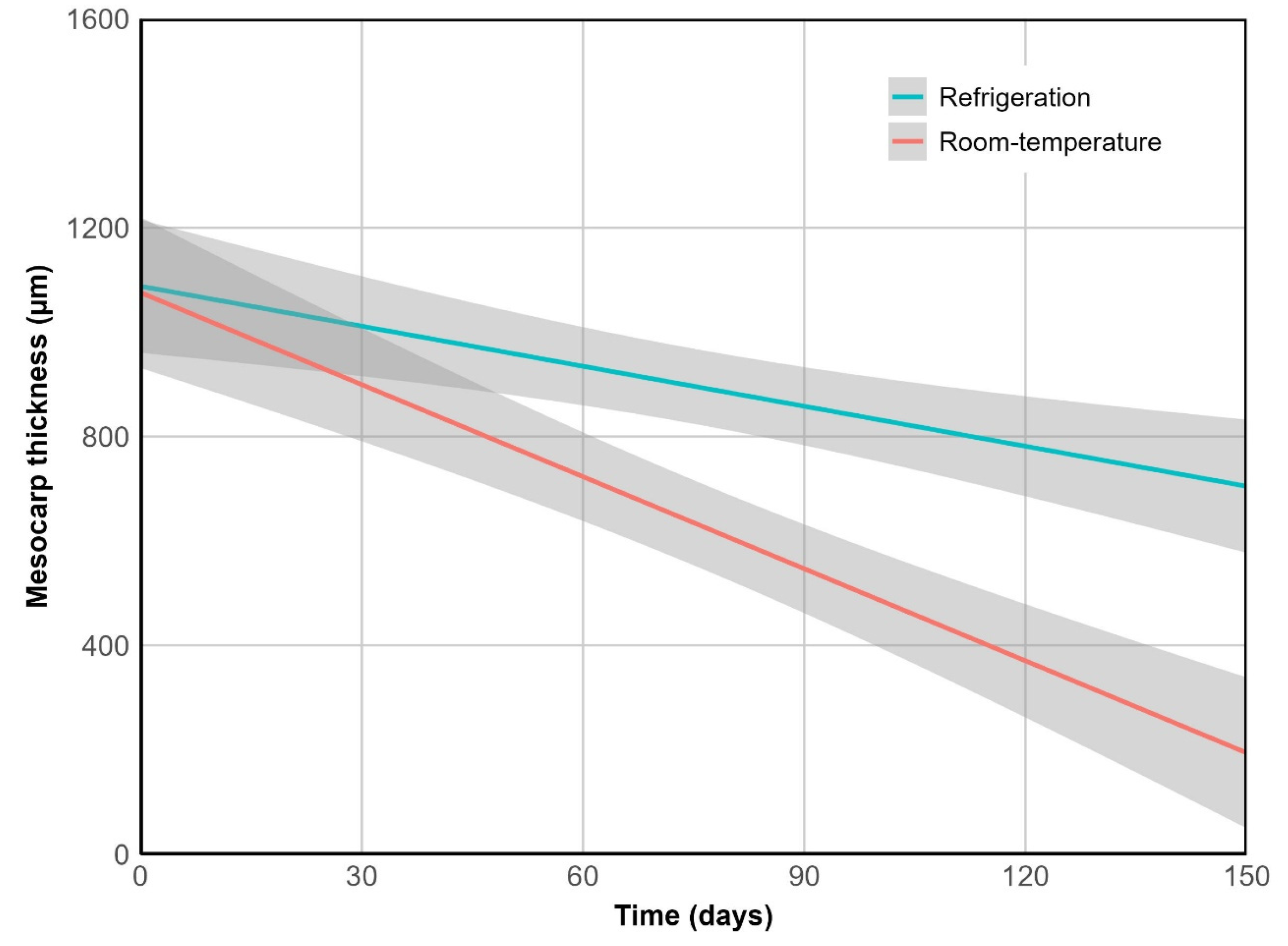

2.2.3. Tissue Degradation

Cuticle thickness remained unchanged over time across storage conditions (

p = 0.977). However, it showed greater disruption at room temperature, increasing mesocarp exposure to the environment. This was reflected in a significantly higher rate of its thinning under this treatment (

p < 0.01) (

Figure 4). After 150 days, mesocarp thickness decreased by 82% at room temperature (from 1085 µm to 193 µm), compared to only 37% under refrigeration.

This layer emerged as the sole significant predictor of pericarp thinning (p < 0.001), exhibiting a strong relationship between both measurements (R2 = 0.97, p < 0.001). Hence, considering pericarp thickness as a macro-scale indicator of tissue breakdown, a comparable trend was observed: it declined over time (p < 0.01) and differed significantly between storage treatments (p < 0.01). At room temperature, pericarp thickness decreased by 73% (from 1250 µm to 343 µm), while under refrigeration the reduction was limited to 31%.

The Spearman test revealed high correlations of both fruit weight and moisture content with mesocarp (ρ ≥ 0.96,

p < 0.001) and pericarp thickness (ρ ≥ 0.90,

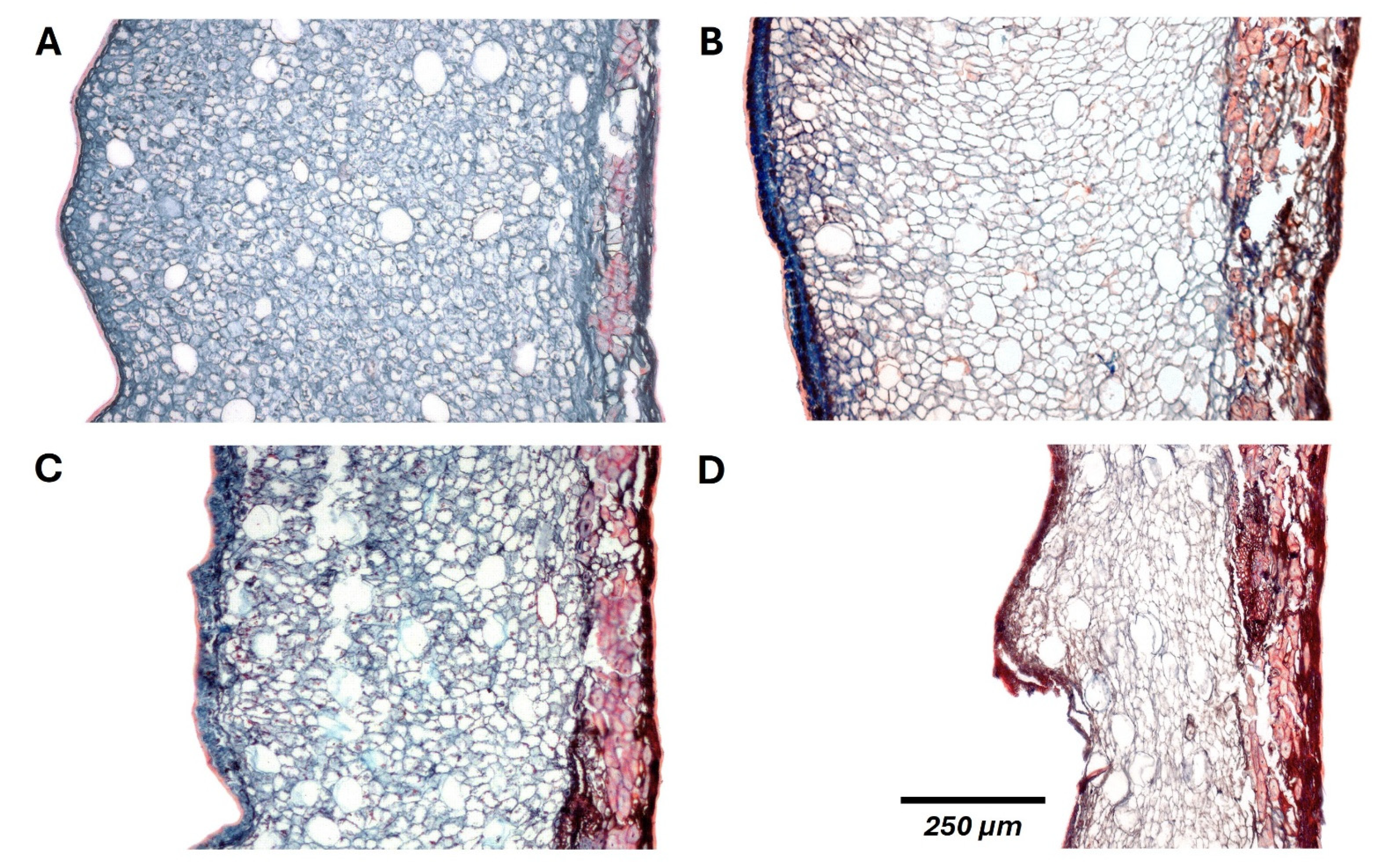

p < 0.001). Consistently, histological analysis showed a gradual loss of turgor and widespread cell collapse in the mesocarp during storage, accounting for the observed reduction in thickness (

Figure 5). These changes were further accompanied by tissue lignification, predominantly in the endocarp, which increased pericarp rigidity and ultimately caused the detachment of both the pericarp from the seed coat and the seed coat from the cotyledons at room temperature, marking irreversible alterations in fruit integrity (

Figure 6).

2.2.4. Reserve Depletion

Cotyledon starch granules decreased in abundance at a steady rate over time (

p < 0.05). Unlike the other variables, this trend did not vary significantly between storage conditions (

p = 0.370), with an overall reduction of 51% by the end of the experiment (

Figure 7). However, marked structural differences were observed. In refrigerated fruits, starch granules retained their morphology and remained embedded within an intact cellular matrix, whereas at room temperature they became irregularly distributed and exhibited surface roughness and fragmentation, consistent with more advanced enzymatic degradation (

Figure 8).

3. Discussion

Storage conditions had a pronounced effect on

C. alba fruit breakdown, with refrigeration at 5°C (RH 81%) substantially reducing degradation rates. This provides robust support for the long-standing literature recommendations and practices of the past sixty years advocating cold storage for this species [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Thus, previous knowledge is now corroborated by physical, histological and ultrastructural evidence, constituting a scientifically grounded basis to inform conservation strategies.

Fruit desiccation, known to begin during maturation [

32], proceeds at a constant rate driven by storage temperature, as reflected in changes in weight and moisture content. While earlier works identified the pericarp as a barrier against water loss [

33,

34,

35], our results reveal that this function is progressively undermined by structural breakdown, primarily caused by the loss of mesocarp integrity. Since this tissue consists mainly of water-rich parenchyma cells, storage conditions exert a marked influence on its desiccation, with higher temperatures accelerating the decline of cell turgor and the consequent collapse of the tissue.

By contrast, fruit lignification, reported to decline until ripening [

36], intensifies during storage, ultimately enhancing pericarp rigidity and detachment from the seed coat. This loss of structural continuity constitutes a pivotal stage of fruit breakdown, diminishing the protective function of the pericarp through the progressive exposure of the seed to the surrounding atmosphere, a process that was prevented even after 150 days of refrigeration.

Documented differences in pericarp thickness among

C. alba populations, and variation in fruit shape across provenances and years [

32,

37,

38], are expected to modulate breakdown rates through variable susceptibility to desiccation, driven both by the extent of the protective tissue and by changes in the surface-to-volume relationship. Consequently, additional handling measures should be implemented for fruits with thin pericarps or elongated shapes.

Alongside structural deterioration, seed breakdown is further caused by the persistence of metabolic activity after ripening. In line with previous findings that respiration persists through this stage in

C.

alba fruits [

32], seeds undergo continuous mobilization of carbon reserves during postharvest, gradually depleting their storage compounds, as reflected in the decline in starch granules recorded in our study. This pattern was partially unaffected by the evaluated storage conditions, reflecting the presence of an endogenous metabolic demand, as also reported for other recalcitrant species [

39,

40,

41]. Therefore, targeted interventions—such as modified atmospheres with reduced oxygen, hormonal regulators, or controlled hydration—should be explored as potential strategies to down-regulate reserve consumption and improve fruit storability.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

Fruits of

C. alba were collected in the Metropolitan Region of Chile (33° 24’ S, 70° 37’ W) in August 2023, at the Ca3 ripening stage according to the classification of Valdenegro et al. [

32]. They were disinfected using a 1% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite solution combined with 0.01% (v/v) Tween® 20 (polysorbate 20) for 15 minutes, followed by rinsing with distilled water and air-drying on paper towels.

Subsequently, 100 fruits were characterized by evaluating their individual weight, length, width, and projected longitudinal area (2D lateral view), using an analytical balance (±0.001 g precision) and the ImageJ software [

42]. The remaining fruits underwent two treatments over a 150-day period: (

i) refrigeration at 5.0 ± 0.6°C (relative humidity 81 ± 7.0%) and (

ii) room-temperature storage at 20.0 ± 2.8°C (RH 87 ± 9.3%). Their impact on fruit integrity was evaluated through multiscale analysis performed at 30-day intervals, as detailed in the following sections.

4.2. Physical Analysis

Weight was monitored in twenty individually labeled fruits per treatment at each interval, enabling repeated measurements over time. In parallel, moisture content was assessed destructively in four samples of five fruits each by placing them at 130°C for 2 hours in a WiseVen™ WOF-105 drying oven, in accordance with the International Seed Testing Association [

43].

4.3. Histological Analysis

To assess tissue degradation, three fruits per treatment were periodically fixed in a formalin-acetic acid-alcohol (FAA) solution. The samples were then dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, cleared with xylene, and embedded in Paraplast® paraffin, following standard protocols [

44,

45,

46]. Histological sections were obtained using a Thermo Scientific™ HM 325 rotary microtome set to a thickness of 10 μm. These were stained with safranin O (CI 50240) and fast green FCF (CI 42053) to selectively differentiate lignified and cellulose-rich tissues, respectively [

47,

48].

The resulting slides were examined under an Olympus® CX31 epifluorescence microscope equipped with a U-LH100H6 Hg lamp for safranin excitation (~540-550 nm). Images were captured with a MicroPublisher 3.3 RTV camera and processed using QCapture Pro 5.1 software (QImaging®).

The thickness of the cuticle and pericarp layers were measured in four equidistant regions per fruit (

Figure 9). Although the latter is theoretically composed of epicarp, mesocarp, and endocarp, the gradual transition between epidermal and parenchymatous mesocarp cells prevented clear distinction of the epicarp. Consequently, both tissues were measured together and reported as mesocarp.

4.4. Ultrastructural Analysis

Cotyledon starch reserves were monitored under vacuum using a Hitachi SU3500 scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with a backscattered electron (BSE) detector. For each treatment, three fruits were analyzed by quantifying starch granules in three randomly selected 11 750 µm2 regions from each.

4.5. Statistical Analysis

As starch and pericarp layer measurements were taken 3-4 times per fruit, values were averaged to yield a single value. Data normality, homoscedasticity, and residual autocorrelation were evaluated through the Shapiro-Wilk, Breusch-Pagan (or, exclusively for weight, Levene’s test), and Durbin-Watson tests, respectively.

Linear regression models with interaction terms were used to evaluate the effects of treatments on mean fruit moisture, total and layer-specific pericarp thickness, and starch granule count over time. Additional simple models were fitted to explore the relationship between the projected fruit area and that estimated from an ellipse-based equation (1), as well as between total pericarp thickness and its constituent layers.

(1)

Both simple and mixed linear models were tested for weight, incorporating fixed and fruit-level random effects. Model selection was guided by comparisons of Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and likelihood ratio test (LRT) results. Lastly, Spearman’s rank correlation was used to explore associations among measured parameters.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that both structural degradation and persistent metabolic activity impose intrinsic limits on the storage of Cryptocarya alba fruits. By disentangling these processes, we provide a scientific foundation for developing evidence-based handling protocols and emphasize the need to complement environmental control with physiological regulation. These advances are critical to support conservation efforts and improve propagation strategies for this keystone recalcitrant species in Mediterranean forests.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.D., M.C., V.M. and P.P.; methodology, V.D. and J.S-C.; investigation, V.D., J.S-C., D.C., S.V. and M.P.; formal analysis, V.D. and J.S-C.; writing—original draft preparation, V.D. and J.S-C.; writing—review and editing, V.D., J.S-C. and P.P.; supervision, M.C., V.M. and P.P.; funding acquisition, M.C. and V.M. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by ISA Energía under project 503043-12.

Data Availability Statement

All supporting data are presented in the main text. Additional details can be requested from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lida Fuentes (CREAS) and Pía Campodónico for their valuable support and collaboration in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIC |

Akaike information criterion |

| BSE |

Backscattered electron |

| FAA |

Formalin-acetic acid-alcohol |

| LRT |

Likelihood ratio test |

| RH |

Relative humidity |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscopy |

References

- Underwood, E.C.; Viers, J.H.; Klausmeyer, K.R.; Cox, R.L.; Shaw, M.R. Threats and biodiversity in the mediterranean biome. Divers. Distrib. 2009, 15, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.; Altamirano, A.; Cayuela, L.; Lara, A.; González, M. Native forest loss in the Chilean biodiversity hotspot: revealing the evidence. Reg. Environ. Change 2017, 17, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillo-Robles, F.; Tapia-Gatica, J.; Díaz-Siefer, P.; Moya, H.; Youlton, C.; Celis-Diez, J.L.; Santa-Cruz, J.; Ginocchio, R.; Sauvé, S.; Brykov, V.A.; Neaman, A. Which soil Cu pool governs phytotoxicity in field-collected soils contaminated by copper smelting activities in central Chile? Chemosphere 2020, 242, 125176–10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, M.; Marquet, P.; Marticorena, C.; Cavieres, L.; Squeo, F.; Simonetti, J.; Rozzi, R.; Massardo, F. El hotspot chileno, prioridad mundial para la conservación. In Diversidad de Chile: patrimonios y desafíos; Comisión Nacional del Medio Ambiente, Ed.; 2006; pp. 94–97.

- Figueroa, J.A.; Jaksic, F.M. Latencia y banco de semillas en plantas de la región mediterránea de Chile central. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2004, 77, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, K.N.; Promis, Á.A.; Mancilla, G.; Magni, C.R. Leaf litter and irrigation can increase seed germination and early seedling survival of the recalcitrant-seeded tree Beilschmiedia miersii. Austral Ecol. 2019, 44, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magni, C.R.; Saavedra, N.; Espinoza, S.E.; Yáñez, M.A.; Quiroz, I.; Faúndez, Á.; Grez, I.; Martinez-Herrera, E. The recruitment of the recalcitrant-seeded Cryptocarya alba (Mol.) Looser, established via direct seeding is mainly affected by the seed source and forest cover. Plants 2022, 11, 2918–10.3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berjak, P.; Pammenter, N.W. Implications of the lack of desiccation tolerance in recalcitrant seeds. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 478–10.3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, C.; Berjak, P.; Pammenter, N.; Kennedy, K.; Raven, P. Preservation of recalcitrant seeds. Science 2013, 339, 915–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faúndez, Á.; Magni, C.R.; Martínez-Herrera, E.; Espinoza, S.; Vaswani, S.; Yañez, M.A.; Gréz, I.; Seguel, O.; Abarca-Rojas, B.; Quiroz, I. Effect of the soil matric potential on the germination capacity of Prosopis chilensis, Quillaja saponaria and Cryptocarya alba from contrasting geographical origins. Plants 2022, 11, 2963–10.3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyse, S.V.; Dickie, J.B.; Willis, K.J. Seed banking not an option for many threatened plants. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 848–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, H.W.; Sershen; Tsan, F.Y.; Wen, B.; Jaganathan, G.K.; Calvi, G.; Pence, V.C.; Mattana, E.; Ferraz, I.D.K.; Seal, C.E. Regeneration in recalcitrant-seeded species and risks from climate change. In Plant regeneration from seeds; Baskin, C.C., Baskin, J.M., Eds.; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 259–273. 10.1016/B978-0-12-823731-1.00014-7.

- Delpiano, C.A.; Vargas, S.; Ovalle, J.F.; Cáceres, C.; Zorondo-Rodríguez, F.; Miranda, A.; Pohl, N.; Rojas, C.; Squeo, F.A. Unveiling emerging interdisciplinary research challenges in the highly threatened sclerophyllous forests of central Chile. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2024, 97, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, S.; Dixon, K.W. International principles and standards for native seeds in ecological restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; León-Lobos, P.; Contreras, S.; Ovalle, J.F.; Sershen; Van Der Walt, K.; Ballesteros, D. The potential impacts of climate change on ex situ conservation options for recalcitrant-seeded species. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1110431–10.3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Daws, M.I.; Stuppy, W.; Zhou, Z.-K.; Pritchard, H.W. Rates of water loss and uptake in recalcitrant fruits of Quercus species are determined by pericarp anatomy. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47368–10.1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyse, S.V.; Dickie, J.B. Taxonomic affinity, habitat and seed mass strongly predict seed desiccation response: a boosted regression trees analysis based on 17 539 species. Ann. Bot. 2018, 121, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, H.F.; Mazzottini-dos-Santos, H.C.; Dias, D.S.; Azevedo, A.M.; Lopes, P.S.N.; Nunes, Y.R.F.; Ribeiro, L.M. The dynamics of Mauritia flexuosa (Arecaceae) recalcitrant seed banks reveal control of their persistence in marsh environments. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 511, 120155–10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley-López, J.M.; Wawrzyniak, M.K.; Chacón-Madrigal, E.; Chmielarz, P. Seed traits and tropical arboreal species conservation: a case study of a highly diverse tropical humid forest region in Southern Costa Rica. Biodivers. Conserv. 2023, 32, 1573–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lah, N.H.C.; El Enshasy, H.A.; Mediani, A.; Azizan, K.A.; Aizat, W.M.; Tan, J.K.; Afzan, A.; Noor, N.M.; Rohani, E.R. An insight into the behaviour of recalcitrant seeds by understanding their molecular changes upon desiccation and low temperature. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2099–10.3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, C.; Rosa, C.P.D.; Pagel, G.D.O.; Aumonde, T.Z.; Tunes, L.V.M. Challenges for storing recalcitrant seeds. Colloq. Agrar. 2023, 19, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luebert, F.; Pliscoff, P. Sinopsis bioclimática y vegetacional de Chile, 2nd ed.; Editorial Universitaria: Santiago, Chile, 2018; 384 p.

- Gipoulou-Zúñiga, T.; Rojas-Badilla, M.; LeQuesne, C.; Rozas, V. Endemic threatened tree species in the Mediterranean forests of central Chile are highly sensitive to ENSO-driven water availability and drought. For. Ecosyst. 2025, 13, 100324–10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Caro, B. Criterios prácticos para la recolección y almacenamiento de semillas forestales en programas de conservación, restauración y mejoramiento genético. Cienc. Invest. For. 2025, 31, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, A. Reforestación por siembra directa con Quillay (Quillaja saponaria Mol.) y Peumo (Cryptocarya alba (Mol.) Looser). Tesis de Ingeniería Forestal, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 1966.

- Ramírez, B. Factores que afectan la germinación y la producción de plantas de Cryptocarya alba (Mol.) Looser. Tesis de Ingeniería Forestal, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 1997.

- Doll, U. Domesticación de especies nativas ornamentales de potencial uso industrial (FIA-PI-C-1996-1-F-007); Fundación para la Innovación Agraria: Talca, Chile, 2000; 207 p.

- Rodríguez, M.; Aguilera, M. Antecedentes silviculturales del peumo. In Recopilación de experiencias silvícolas en el “Bosque nativo Maulino”; Aguilera, M., Benavides, G., Eds.; Corporación Nacional Forestal, Santiago, Chile, 2005; pp. 121–127.

- Vogel, H.; Razmilic, I.; San Martín, J.; Doll, U.; González, B. Plantas medicinales chilenas: experiencias de domesticación y cultivo de boldo, matico, bailahuén, canelo, peumo y maqui, 2nd ed.; Universidad de Talca: Talca, Chile, 2008; 193 p.

- Rodríguez-Cerda, L.; Guedes, L.M.; Torres, S.; Gavilán, E.; Aguilera, N. Phenolic antioxidant protection in the initial growth of Cryptocarya alba: two different responses against two invasive Fabaceae. Plants 2023, 12, 3584–10.3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdenegro, M.; Bernales, M.; Knox, M.; Vinet, R.; Caballero, E.; Ayala-Raso, A.; Kučerová, D.; Kumar, R.; Viktorová, J.; Ruml, T.; Figueroa, C.R.; Fuentes, L. Characterization of fruit development, antioxidant capacity, and potential vasoprotective action of peumo (Cryptocarya alba), a native fruit of Chile. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1997–10.3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, R.O.; Walkowiak, A.; Henríquez, C.A.; Serey, I. Bird frugivory and the fate of seeds of Cryptocarya alba (Lauraceae) in the Chilean matorral. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 1996, 69, 357–363. [Google Scholar]

- Chacón, P. Efecto del tamaño de la semilla y del pericarpio sobre el reclutamiento y biomasa de plántulas en Cryptocarya alba (Mol.) Looser (Lauraceae) en un año lluvioso y en un año seco simulados experimentalmente. Tesis de Magíster en Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 1998.

- Chacón, P.; Bustamante, R.O. The effects of seed size and pericarp on seedling recruitment and biomass in Cryptocarya alba (Lauraceae) under two contrasting moisture regimes. Plant Ecol. 2001, 152, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, C.; Ríos, D.; Fuentes, L.; Valdenegro, M.; Martínez, J.P.; Franco, W.; Vinet, R.; Sáez, F.; Ayala, A.; Paredes, K.; Fernández, D.; Sanhueza, R.; Narváez, G. Caracterización del potencial saludable y agroalimentario de frutos de especies arbóreas nativas de la zona centro sur del país (Proyecto CONAF 064/2011); CONAF: 2012; 60 p.

- Benedetti, S. Monografía de peumo Cryptocarya alba (Mol.) Looser; Instituto Forestal: Santiago, Chile, 2012; 77 p.

- Chung, P.; Gutiérrez, B.; Benedetti, S. Variabilidad morfológica de frutos de peumo (Cryptocarya alba (Mol.) Looser) de distintas localidades de la región del Bio Bio. Cienc. Invest. For. 2017, 23, 7–18.

- Bonjovani, M.R.; Barbedo, C.J. Respiration and deterioration of Inga vera ssp. affinis embryos stored at different temperatures. J. Seed Sci. 2019, 41, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tonetti, O.A.O.; Pereira, W.V.S.; José, A.C.; Faria, J.M.R. Physiological and cellular changes of stored Cryptocarya aschersoniana Mez. seeds. Floresta Ambient. 2021, 28, e20200067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzyniak, M.K.; Kalemba, E.M.; Wyka, T.P.; Chmielarz, P. Changes in reserve materials deposited in cotyledons of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L.) seeds during 18 months of storage. Forests 2022, 13, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Seed Testing Association (ISTA). International rules for seed testing; ISTA: Bassersdorf, Switzerland, 2016; 320 p.

- Johansen, D.A. Plant microtechnique; McGraw-Hill: New York, United States, 1940; 523 p.

- Singh, D.; Mathur, S.B. Histopathology of seed-borne infections; CRC Press: Florida, United States, 2004; 296 p.

- Santa Cruz, J.; Calbucheo, D.; Valdebenito, S.; Cáceres, C.; Castillo, P.; Aguilar, M.; Allendes, H.; Vidal, K.; Peñaloza, P. Crushed, squeezed, or pressed? How extraction methods influence sap analysis (pre-print). Research Square 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, J.A. Histological and histochemical methods: theory and practice, 5th ed.; Scion: 2015; 571 p.

- Criswell, S.; Gaylord, B.; Pitzer, C.R. Histological methods for plant tissues. J. Histotechnol. 2025, 48, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Pericarp structure of fresh C. alba fruits. Cuticular flanges (cf), cuticle (cu), endocarp (en), epidermal cells (ep), mesocarp (me), parenchyma cells (pa), seed coat (sc), vascular bundles (vb).

Figure 1.

Pericarp structure of fresh C. alba fruits. Cuticular flanges (cf), cuticle (cu), endocarp (en), epidermal cells (ep), mesocarp (me), parenchyma cells (pa), seed coat (sc), vascular bundles (vb).

Figure 2.

Weight loss over time. Thin lines represent individual fruit weight loss trajectories. Solid lines represent the fixed-effect predictions from the mixed model, summarizing the overall trend for each treatment. This component explained 36% of the variance (R2m = 0.36), while the full model—including random effects—accounted for nearly twice (R2c = 0.71).

Figure 2.

Weight loss over time. Thin lines represent individual fruit weight loss trajectories. Solid lines represent the fixed-effect predictions from the mixed model, summarizing the overall trend for each treatment. This component explained 36% of the variance (R2m = 0.36), while the full model—including random effects—accounted for nearly twice (R2c = 0.71).

Figure 3.

Moisture loss over time. Lines represent predicted values from the linear model with interaction terms, while shaded ribbons indicate the 95% confidence intervals. R2 = 0.93, p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Moisture loss over time. Lines represent predicted values from the linear model with interaction terms, while shaded ribbons indicate the 95% confidence intervals. R2 = 0.93, p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Mesocarp thinning over time. R2 = 0.94, p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Mesocarp thinning over time. R2 = 0.94, p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Histological changes in C. alba fruits after 30 days (A,B) and 150 days (C,D) of storage under refrigeration (A,C) or room temperature (B,D).

Figure 5.

Histological changes in C. alba fruits after 30 days (A,B) and 150 days (C,D) of storage under refrigeration (A,C) or room temperature (B,D).

Figure 6.

SEM views of fruit integrity. Before storage (A-B), and after 150 days of storage under refrigeration (C) and at room temperature (D). Cotyledons (co), cuticle (cu), endocarp (en), mesocarp (me), pericarp (pe), seed coat (sc).

Figure 6.

SEM views of fruit integrity. Before storage (A-B), and after 150 days of storage under refrigeration (C) and at room temperature (D). Cotyledons (co), cuticle (cu), endocarp (en), mesocarp (me), pericarp (pe), seed coat (sc).

Figure 7.

Cotyledon starch depletion over time. R2 = 0.68, p < 0.01.

Figure 7.

Cotyledon starch depletion over time. R2 = 0.68, p < 0.01.

Figure 8.

SEM views of cotyledon integrity. Before storage (A-B), and after 150 days of storage under refrigeration (C) and at room temperature (D). Cotyledons (co), pericarp (pe), seed coat (sc), starch granules (st).

Figure 8.

SEM views of cotyledon integrity. Before storage (A-B), and after 150 days of storage under refrigeration (C) and at room temperature (D). Cotyledons (co), pericarp (pe), seed coat (sc), starch granules (st).

Figure 9.

Longitudinal view of fresh C. alba fruits. Smooth, glossy pericarp (pe), enclosing a single seed with a light brown seed coat (sc), pale cream cotyledons (co) showing slight granular appearance, and a pink embryo (em) located at the distal end. Asterisks (∗) indicate the measurement regions of cuticle and pericarp thickness. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Figure 9.

Longitudinal view of fresh C. alba fruits. Smooth, glossy pericarp (pe), enclosing a single seed with a light brown seed coat (sc), pale cream cotyledons (co) showing slight granular appearance, and a pink embryo (em) located at the distal end. Asterisks (∗) indicate the measurement regions of cuticle and pericarp thickness. Scale bars = 1 mm.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).