Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

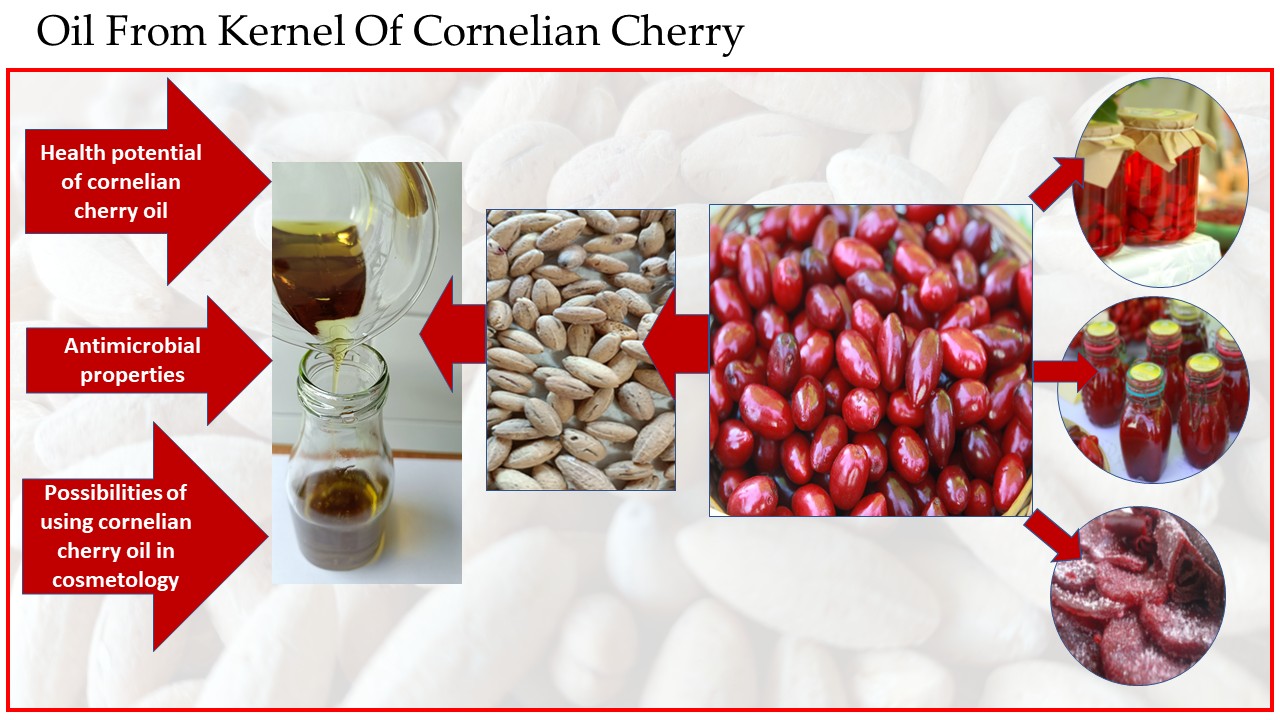

2.1. Cornelian Cherry as a Source of Oil

2.2. Characteristics of Cornelian Cherry Seed Oil

2.3. Health Potential of Cornelian Cherry Oil

2.4. Antimicrobial Properties

2.5. Possibilities of Using Cornelian Cherry Oil in Cosmetology

2.6. Other Uses of Cornelian Cherry Oil

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skender, A.; Ðurić, G.; Assouguem, A.; Ercisli, S.; Ilhan, G.; Lahlali, R.; Ullah, R.; Iqbal, Z.; Bari, A. Molecular Characterisation of Cornelian Cherry ( Cornus Mas L.) Genotypes. Folia Horticulturae 2024, 36, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, A.Z. Związki aktywne owoców derenia (Cornus mas L.); Monografie / [Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy we Wrocławiu]; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego: Wrocław, 2012; ISBN 978-83-7717-096-0. [Google Scholar]

- Spychaj, R.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Szumny, A.; Przybylska, D.; Pejcz, E.; Piórecki, N. Potential Valorization of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Stones: Roasting and Extraction of Bioactive and Volatile Compounds. Food Chemistry 2021, 358, 129802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akalın, M.K.; Tekin, K.; Karagöz, S. Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Cornelian Cherry Stones for Bio-Oil Production. Bioresource Technology 2012, 110, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Guleria, S.; Kimta, N.; Nepovimova, E.; Dhalaria, R.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Sethi, N.; Alomar, S.Y.; Kuca, K. Selected Fruit Pomaces: Nutritional Profile, Health Benefits, and Applications in Functional Foods and Feeds. Current Research in Food Science 2024, 9, 100791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, E.; Simoes, A.; Domingues, M.R. Fruit Seeds and Their Oils as Promising Sources of Value-Added Lipids from Agro-Industrial Byproducts: Oil Content, Lipid Composition, Lipid Analysis, Biological Activity and Potential Biotechnological Applications. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2021, 61, 1305–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniasz, M.; Dziedzic, E.; Kaczmarczyk, E. The Effect of Storage and Processing on Vitamin C Content in Japanese Quince Fruit. Folia Horticulturae 2017, 29, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniek, A.; Bieniek, A.; Bielska, N. Variation in Fruit and Seed Morphology of Selected Biotypes and Cultivars of Elaeagnus Multiflora Thunb. in North-Eastern Europe. Agriculture 2023, 13, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniek, A.; Lachowicz-Wiśniewska, S.; Bojarska, J. The Bioactive Profile, Nutritional Value, Health Benefits and Agronomic Requirements of Cherry Silverberry (Elaeagnus Multiflora Thunb.): A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, A.; Bruschi, P.; Campeggi, S.; Egea, T.; Rivera, D.; Obón, C.; Lenzi, A. The Renaissance of Wild Food Plants: Insights from Tuscany (Italy). Foods 2022, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziedzic, E.; Błaszczyk, J.; Bieniasz, M.; Dziadek, K.; Kopeć, A. Effect of Modified (MAP) and Controlled Atmosphere (CA) Storage on the Quality and Bioactive Compounds of Blue Honeysuckle Fruits (Lonicera Caerulea L.). Scientia Horticulturae 2020, 265, 109226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa, T.; Klimek, K.; Zaraś-Januszkiewicz, E. Nutritional Values of Minikiwi Fruit (Actinidia Arguta) after Storage: Comparison between DCA New Technology and ULO and CA. Molecules 2022, 27, 4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Młynarczyk, K.; Walkowiak-Tomczak, D.; Staniek, H.; Kidoń, M.; Łysiak, G.P. The Content of Selected Minerals, Bioactive Compounds, and the Antioxidant Properties of the Flowers and Fruit of Selected Cultivars and Wildly Growing Plants of Sambucus Nigra L. Molecules 2020, 25, 876. Molecules 2020, 25, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyinska, A.; Klymenko, S. The New Earliest Cultivar of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.). Plant. Introd. 2023, 97–98, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniewska, E.; Dolatowski, J.; Hordowski, J.; Lib, D.; Piorecki, N.; Scelina, M.; Zurawel, R. Stare derenie jadalne (Cornus mas L.) w Łukowem w Bieszczadach. Rocznik Polskiego Towarzystwa Dendrologicznego 2018, 66, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Rop, R.; Mlcek, J.; Kramarova, D.; Jurikova, T. Selected Cultivars of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) as a New Food Source for Human Nutrition. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 9, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijelić, S.; Gološin, B.; Cerović, S.; Bogdanović, B. Pomological Characteristics of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Selections in Serbia and the Possibility of Growing in Intensive Organic Orchards. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendelianae Brun. 2015, 63, 1101–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjakovic, D.; Ognjanov, V.; Ljubojevic, M.; Barac, G.; Predojevic, M.; Mladenovic, E.; Cukanovic, J. Biodiversity of Wild Fruit Species of Serbia. Genetika 2012, 44, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ognjanov, V.; Cerović, S.; Ninić-Todorović, J.; Jaćimović, V.; Gološin, B.; Bijelić, S.; Vračević, B. Selection and Utilization of Table Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas l.). Acta Hortic. 2009, 814, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinović, A.; Cavoski, I. The Exploitation of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Cultivars and Genotypes from Montenegro as a Source of Natural Bioactive Compounds. Food Chem 2020, 318, 126549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercisli, S. A Short Review of the Fruit Germplasm Resources of Turkey. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2004, 51, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, B.; Sayinci, B.; Sümbül, A.; Yaman, M.; Yildiz, E.; Çetin, N.; Karakaya, O.; Ercişli, S. Bioactive Compounds and Physical Attributes of Cornus Mas Genotypes through Multivariate Approaches. Folia Horticulturae 2020, 32, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamedov, N.; Craker, L.E. Cornelian Cherry: A Prospective Source For Phytomedicine. Acta Hortic. 2004, 629, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, B.; Filip, A.; Clichici, S.; Suharoschi, R.; Bolfa, P.; David, L. Antioxidant Activity of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Fruits Extract and the in Vivo Evaluation of Its Anti-Inflammatory Effects. Journal of Functional Foods 2016, 26, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, B.; Abasi, M.; Abbasi, M.M.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, R. Anti-Proliferative Properties of Cornus Mass Fruit in Different Human Cancer Cells. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2015, 16, 5727–5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yigit, D. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Evaluation of Fruit Extract from Cornus Mas L. Aksaray University Journal of Science and Engineering 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarhosseini, F.; Sangouni, A.A.; Sangsefidi, Z.S.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Akhondi-Meybodi, M.; Ranjbar, A.; Fallahzadeh, H.; Mozaffari-Khosravi, H. Effect of Cornus Mas L. Fruit Extract on Blood Pressure, Anthropometric and Body Composition Indices in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 2023, 56, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szumny, D.; Sozański, T.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Dziewiszek, W.; Piórecki, N.; Magdalan, J.; Chlebda-Sieragowska, E.; Kupczynski, R.; Szeląg, A.; Szumny, A. Application of Cornelian Cherry Iridoid-Polyphenolic Fraction and Loganic Acid to Reduce Intraocular Pressure. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2015, 2015, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omelka, R.; Blahova, J.; Kovacova, V.; Babikova, M.; Mondockova, V.; Kalafova, A.; Capcarova, M.; Martiniakova, M. Cornelian Cherry Pulp Has Beneficial Impact on Dyslipidemia and Reduced Bone Quality in Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats. Animals 2020, 10, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spychaj, R.; Przybylska, D.; Szachniewicz, M.; Piórecki, N.; Kucharska, A.Z. Selection of Roasting Conditions in the Valorization Process of Cornelian Cherry Stones. Molecules 2025, 30, 2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipović, D.; Gašić, U.; Stevanović, N.; Dabić Zagorac, D.; Fotirić Akšić, M.; Natić, M. Carbon Stable Isotope Composition of Modern and Archaeological Cornelian Cherry Fruit Stones: A Pilot Study. Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies 2018, 54, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q. (Jenny); Manchester, S.R.; Thomas, D.T.; Zhang, W.; Fan, C. Phylogeny, Biogeography, and Molecular Dating of Cornelian Cherries (Cornus, Cornaceae): Tracking Tertiary Plant Migration. Evolution 2005, 59, 1685–1700. [CrossRef]

- Demir, F.; Hakki Kalyoncu, İ. Some Nutritional, Pomological and Physical Properties of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.). Journal of Food Engineering 2003, 60, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brindza, P.; Brindza, J.; Tóth, D.; Klimenko, S.V.; Grigorieva, O. Slovakian Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.): Potential for Cultivation. Acta Hortic. 2007, 760, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokoupil, L.; Řezníček, V. Production and Use of the Cornelian Cherry - Cornus Mas L. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendelianae Brun. 2013, 60, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljevic, M.; Moslavac, T. Supercritical CO2 Extraction of Oil from Rose Hips (Rosa Canina L.) and Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Seeds. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 10, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennajeh, M.; Ouledali, S. Supplement of a Commercial Mycorrhizal Product to Improve the Survival and Ecophysiological Performance of Olive Trees in an Arid Region. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2024, 23, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaib, S.E.; Riyapan, P.; Jumrat, S.; Pianroj, Y.; Muangprathub, J. Predictions of Oil Volume in Palm Fruit and Estimates of Their Ripeness: A Comparative Study of Machine Learning Algorithms. Acta Agro 2024, 77, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Sattar, M.; Al-Obeed, R.S.; Aboukarima, A.M.; Górnik, K.; El-Badan, G.E. An Evaluation Rule to Manage Productivity Properties Performance of Male Date Palms. Folia Horticulturae 2024, 36, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szot, I. CORNELIAN CHERRY (Cornus Mas L.); 1st ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego w Lublinie, 2024; ISBN 978-83-7259-427-3.

- Szot, I.; Łysiak, G.P.; Sosnowska, B. The Beneficial Effects of Anthocyanins from Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Fruits and Their Possible Uses: A Review. Agriculture 2023, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szot, I.; Łysiak, G.P.; Sosnowska, B.; Chojdak-Łukasiewicz, J. Health-Promoting Properties of Anthocyanins from Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Fruits. Molecules 2024, 29, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szot, I.; Lipa, T.; Sosnowska, B. EVALUATION OF YIELD AND FRUIT QUALITY OF SEVERAL ECOTYPES OF CORNELIAN CHERRY (Cornus Mas L.) IN POLISH CONDIOTIONS. asphc 2019, 18, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

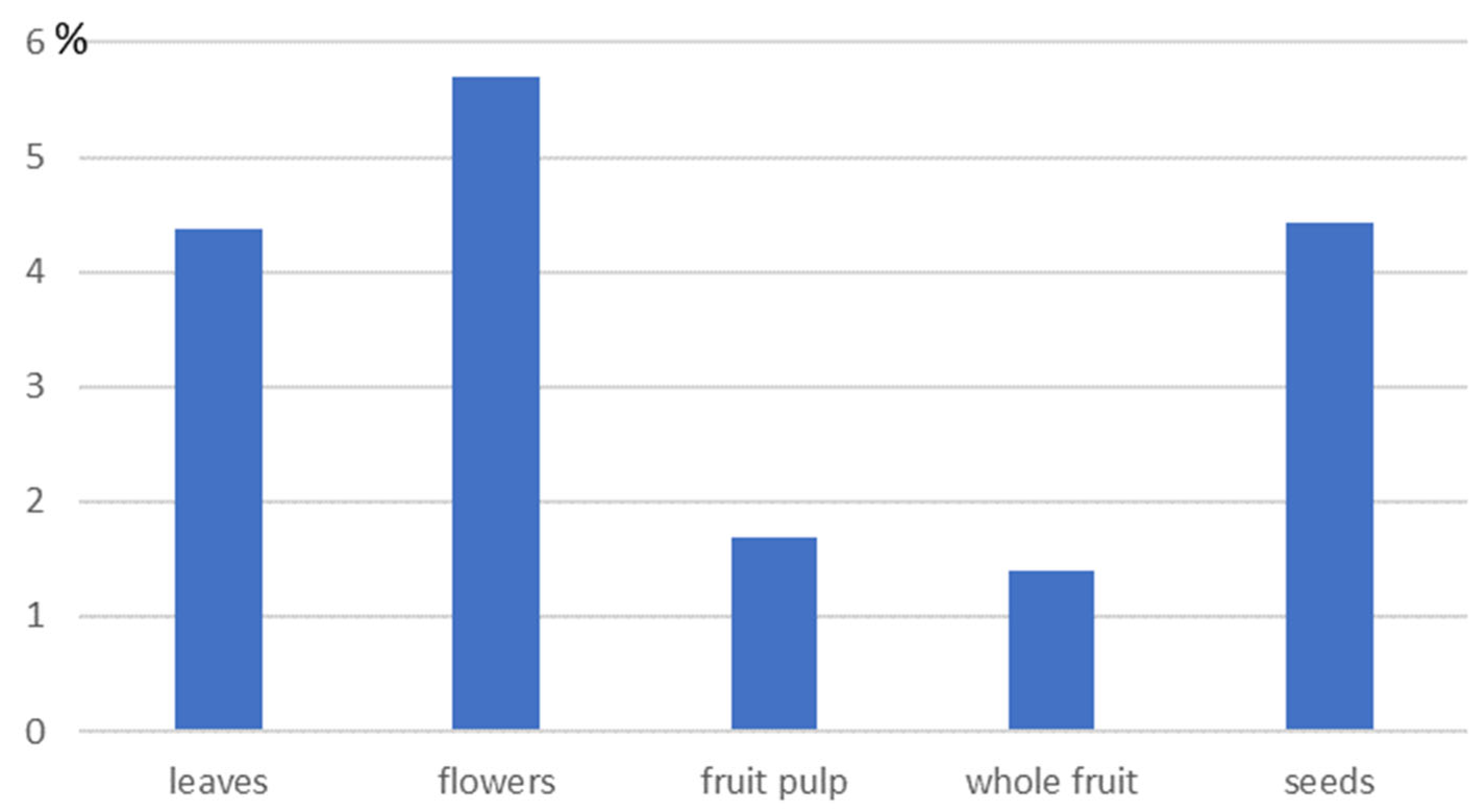

- Antoniewska-Krzeska, A.; Ivanišová, E.; Klymenko, S.; Bieniek, A.A.; Fatrcová-Šramková, K.; Brindza, J. Nutrients Content and Composition in Different Morphological Parts of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.). Agrobiodivers Improv Nutr Health Life Qual 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martysiak-Żurowska, D.; Orzołek, M. The Correlation between Nutritional and Health Potential and Antioxidant Properties of Raw Edible Oils from Cultivated and Wild Plants. Int J of Food Sci Tech 2023, 58, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniewska, A.; Brindza, J.; Klymenko, S.; Shelepova, O. Fatty Acid Composition of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.). 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

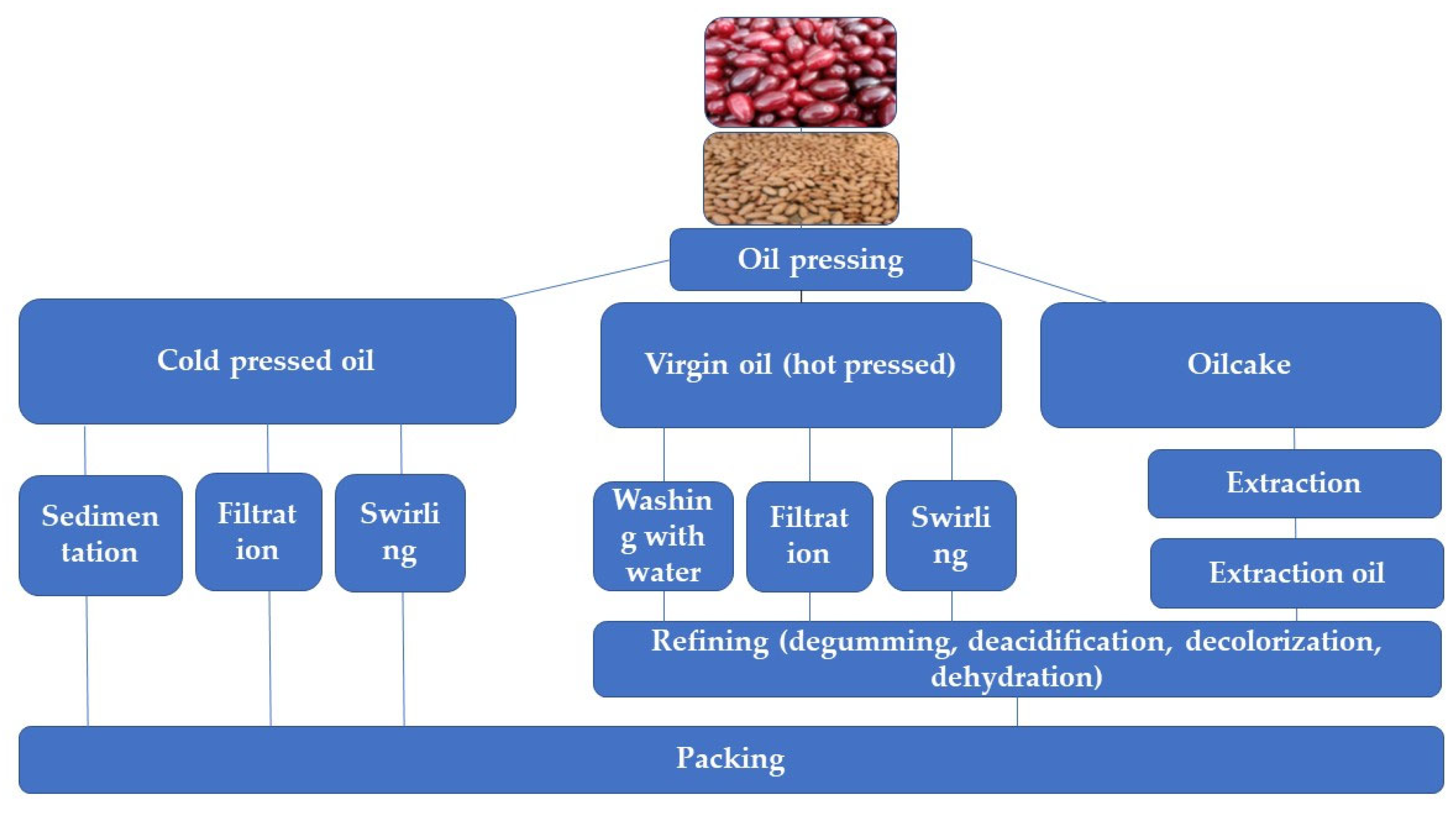

- Wandhekar, S.S.; Pawr, V.S.; Shind, S.T.; Gangakhedkar, P.S. Extraction of Oil from Oilseeds by Cold Pressing: A Review. Indian Food Industry Mag 4, 63–69.

- Wroniak, M.; Kwiatkowska, M.; Krygier, K. Charakterystyka Wybranych Olejów Tłoczonych Na Zimno. Żywność. Nauka, Technologia, Jakość 2006, 2, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu, M.; Ungureanu, N.; Biriş, S.S.; Voicu, G.; Dilea, M. Actual Methods Fo Obtaining Vegetable Oil From Oilseeds. Conference Paper 2013.

- Baümler, E.R.; Carrín, M.E.; Carelli, A.A. Extraction of Sunflower Oil Using Ethanol as Solvent. Journal of Food Engineering 2016, 178, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharby, S. Refining Vegetable Oils: Chemical and Physical Refining. The Scientific World Journal 2022, 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

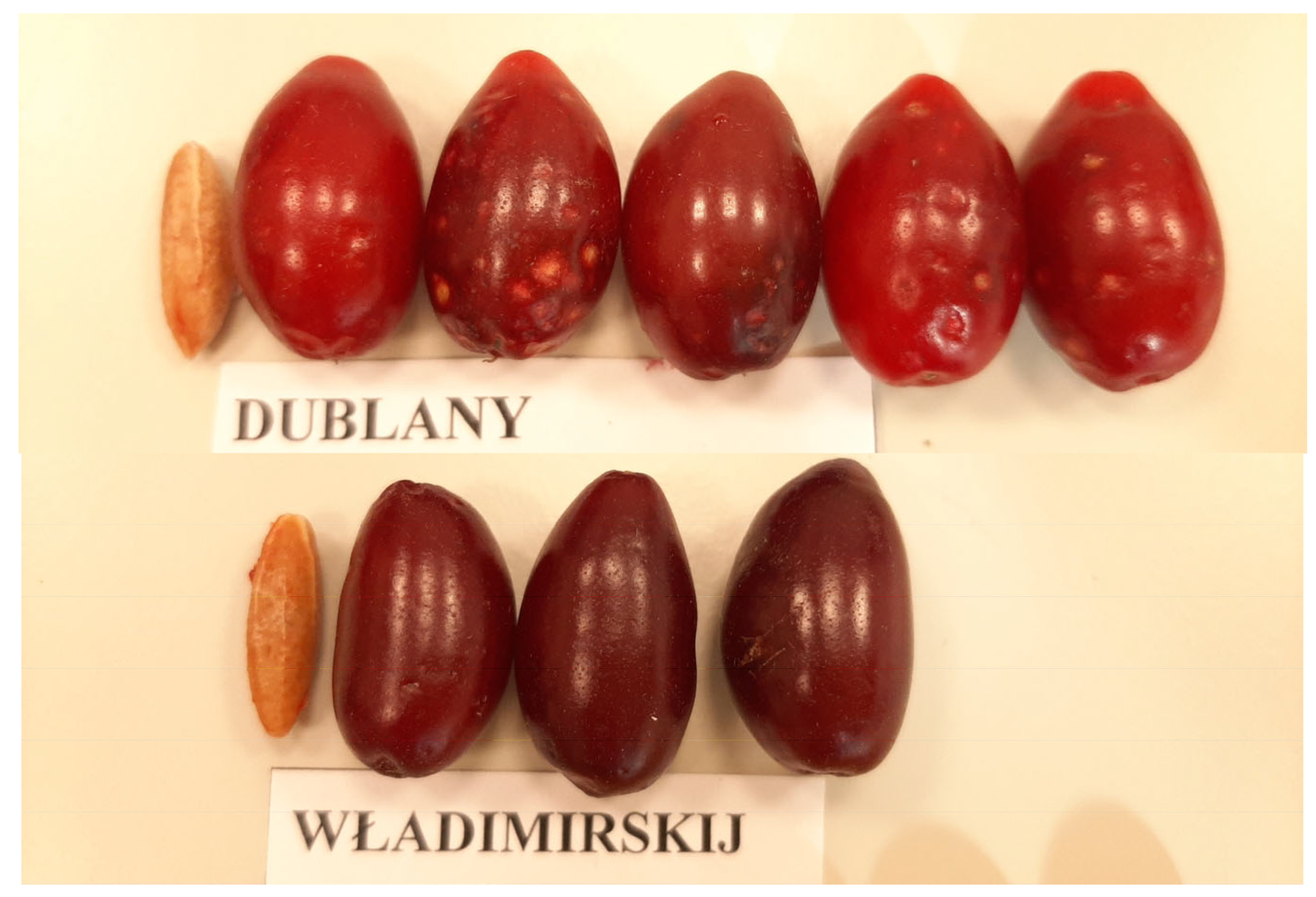

- Kucharska, A.Z.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Piórecki, N. MORPHOLOGICAL, PHYSICAL & CHEMICAL, AND ANTIOXIDANT PROFILES OF POLISH VARIETIES OF CORNELIAN CHERRY FRUIT (CORNUS MAS L.). ZNTJ 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levon, V.; Klymenko, S. Content of Anthocyanins and Flavonols in the Fruits of Cornus Spp. Agrobiodivers Improv Nutr health life Qual 2021, 5, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szot, I.; Szot, P.; Lipa, T.; Sosnowska, B.; Dobrzański, B. CHANGES IN PHYSICAL AND CHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF CORNELIAN CHERRY (CORNUS MAS L.) FRUITS IN DEPENDENCE ON DEGREE OF RIPENING AND ECOTYPES. asphc 2019, 18, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashirina, N.A.; Bagrikova, N.A.; Zhaldak, S.N.; Pashtetsky, V.S.; Drobotova, E.N. Morphological and Morphometric Characteristics of Cornelian Сherry (Cornus Mas L.) in Natural Conditions of the Crimean Peninsula. 2021, 726.7Kb. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, Y.; Khadivi, A.; Salehi-Arjmand, H. Morphological and Pomological Characterizations of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) to Select the Superior Accessions. Scientia Horticulturae 2019, 249, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borroto Fernández, E.G.; Mokhber, A.; Zeiser, M.; Laimer, M. Phenotypic Characterization of a Wild-Type Population of Cornelian Cherries (Cornus Mas L.) from Austria. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2022, 64, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercisli, S.; Yilmaz, S.O.; Gadze, J.; Dzubur, A.; Hadziabulic, S.; Aliman, J. Some Fruit Characteristics of Cornelian Cherries (Cornus Mas L.). Notulae Botanicae Horti AgrobotaniciCluj-Napoca 2011, 39, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmetović, M.; Trumić, E.; Bajraktarević, J.; Keran, H.; Šestan, I. Examination the Quality of Oil Obtained from Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Seeds as an Additive in the Production of Cosmetic Preparations and Food Supplements. Int. j. res. appl. sci. biotechnol. 2021, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczak, A.; Grys, A.; Buchwald, W.; Zieliński, J. Content of Oil and Main Fatty Acids in Hips of Rose Species Native in Poland. Dendrobiology 2011, 66, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Milala, J.; Sójka, M.; Król, K.; Buczek, M. Charakterystyka Składu Chemicznego Owoców Rosa Pomifera ’Karpatia. Żywność. Nauka. Technologia. Jakość 2013, 5, 154–167. [Google Scholar]

- Ibeabuchi, J.C.; Bede, N.C.; Kabuo, N.O.; Uzukwu, A.E.; Eluchie, C.N.; Ofoedu, C.E. Proximate Composition, Functional Properties and Oil Characterization of ‘Kpaakpa’ (Hildegardia Barteri) Seed. Integrity Research Journals 2020, 5, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milić, S.M.; Kostić, M.D.; Milić, P.S.; Vučić, V.M.; Arsić, A.Č.; Veljković, V.B.; Stamenković, O.S. Extraction of Oil from Rosehip Seed: Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Optimization. Chem Eng & Technol 2020, 43, 2373–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, T.; Ok, S.; Yılmaz, E. Comprehensive Characterization of Physicochemical, Thermal, Compositional, and Sensory Properties of Cold-Pressed Rosehip Seed Oil. Grasas aceites 2023, 74, e534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcan, N.; Demirel, E. Extraction Parameters and Analysis of Apricot Cernel Oils. Asian Journal of Chemistry 2012, 24, 1499–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Vaidya, D.; Gupta, A.; Kaushal, M. Formulation and Evaluation of Wild Apricot Kernel Oil Based Massage Cream. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2019, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Almasi, S.; Najafi, G.; Ghobadian, B.; Jalili, S. Biodiesel Production from Sour Cherry Kernel Oil as Novel Feedstock Using Potassium Hydroxide Catalyst: Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2021, 35, 102089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, V.-M.; Misca, C.; Bordean, D.; Raba, D.-N.; Stef, D.; Dumbrava, D. Characterization of Sour Cherries (Prunus Cerasus) Kernel Oil Cultivars from Banat. Journal of Agroalimentary Processes and Technologies 2011, 17, 398–401. [Google Scholar]

- Lazos, E.S. Compisition and Oil Characteristics of Apricot, Peach and Cherry Kernel. Cosejo Superior de Investstigaciones Cientificas Licencia Creative Commnos 3.0 Espana 1991, 42, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Shi, J.; Xue, S.; Kakuda, Y.; Wang, D.; Jiang, Y.; Ye, X.; Li, Y.; Subramanian, J. Essential Oil Extracted from Peach (Prunus Persica) Kernel and Its Physicochemical and Antioxidant Properties. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2011, 44, 2032–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, F.; Manzoor, M.; Bukhari, I.H.; Aladedunye, F. Physico-Chemical Attributes of Fruit Seed Oils from Different Varieties ofPeach and Plum. Journal of Advanced in Biology 4, 384–392.

- Savic, I.; Savic Gajic, I.; Gajic, D. Physico-Chemical Properties and Oxidative Stability of Fixed Oil from Plum Seeds (Prunus Domestica Linn.). Biomolecules 2020, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delinska, N.; Perifanova-Nemska, M. Study of Plum Kernel Oil for Use in Soap Production (Prunus Domestica L.). In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing: Prague, Czech Republic, 2023; Vol. 2928, p. 080018. [Google Scholar]

- Vidrih, R.; Čejić, Ž.; Hribar, J. Content of Certain Food Components in Flesh and Stones of the Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Genotypes. Croatian Journal of Food Science and Technology 2012, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Codex Alimentarius. Standard for Named Vegetable Oils-Codex Stan 210-1999 Standard for Named Vegetable Oils-Codex Stan 210- 1999. Codex Alimentarius. 1999. 1999.

- Markowski, J.; Zbrzeźniak, M.; Mieszczakowska-Frąc, M.; Rutkowski, K.; Popińska, W. Effect of Cultivar and Fruit Storage on Basic Composition of Clear and Cloudy Pear Juices. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2012, 49, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, N.; Kalyoncu, İ.H.; Çitil, Ö.B.; Yılmaz, S. Comparison of the Fatty Acid Compositions of Six Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Genotypes Selected From Anatolia. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2019, 61, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierski, M.; Reguła, J.; Molska, M. Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) – Characteristics, Nutritional and pro-Health Properties. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Technologia Alimentaria 2019, 18, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, R. Fatty Acids Composition in Fruits of Wild Rose Species. Acta Soc Bot Pol 2011, 74, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasić, D.; Paunović, D.; Špirović-Trifunović, B.; Miladinović, J.; Vujošević, L.; Đinović, D.; Popović-Đorđević, J. Fatty Acid Composition of Rosehip Seed Oil. Acta agriculturae Serbica 2020, 25, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylska, D.; Kucharska, A.; Cybulska, I.; Sozański, T.; Piórecki, N.; Fecka, I. Cornus Mas L. Stones: A Valuable By-Product as an Ellagitannin Source with High Antioxidant Potential. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosiak, E. Światowy Rynek Olejów Roślinnych. PRS 2017, 17, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.G.; Ford, N.A.; Hu, F.B.; Zelman, K.M.; Mozaffarian, D.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. A Healthy Approach to Dietary Fats: Understanding the Science and Taking Action to Reduce Consumer Confusion. Nutr J 2017, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, M.; Petersen, K.; Kris-Etherton, P. Saturated Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease: Replacements for Saturated Fat to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk. Healthcare 2017, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Cooper, J.A. Effect of Dietary Fatty Acid Composition on Substrate Utilization and Body Weight Maintenance in Humans. Eur J Nutr 2014, 53, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelińska, M. Kwasy Tłuszczowe - Czynniki Modyfikujące Procesy Nowotworowe. Biul. Wydz. Farm. AMW, 2005, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, M.; Aljewicz, M.; Mroczek, E.; Cichosz, G. Olej Palmowy–Tańsza i Zdrowsza Alternatywa. Bromat. Chem.Ttoksykol 2012, 45, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhlifi El Idrissi, Z.; El Guezzane, C.; Boujemaa, I.; El Bernoussi, S.; Sifou, A.; El Moudden, H.; Ullah, R.; Bari, A.; Goh, K.W.; Goh, B.H.; et al. Blending Cold-Pressed Peanut Oil with Omega-3 Fatty Acids from Walnut Oil: Analytical Profiling and Prediction of Nutritive Attributes and Oxidative Stability. Food Chemistry: X 2024, 22, 101453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Waseif, M.A.; Hashem, H.A. Utilization of Palm Oils in Improving Nutritional Value, Quality Properties and Shelf-Life of Infant Formula. Middle East Journal of Agriculture Research 2017, 6, 274–281. [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski, W. Funkcje i Przemiany Metaboliczne Wielonienasyconych Kwasów Tłuszczowych Omega-3 w Organizmie Człowieka. Bromat. Chem. Toksykol 2013, 46, 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Simopoulos, A. An Increase in the Omega-6/Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ratio Increases the Risk for Obesity. Nutrients 2016, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyerberg, J. Linolenate-Derived Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Prevention of Atherosclerosiss. Nutrition Review 44, 125–134.

- Cichosz, G.; Czeczot, H. Oxidative Stability of Edible Fats - Consequences to Human Health. Bromat. Chem. Toksykol. 2011, 1, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Xiao, H.; Lyu, X.; Chen, H.; Wei, F. Lipid Oxidation in Food Science and Nutritional Health: A Comprehensive Review. Oil Crop Science 2023, 8, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal-Eldin, A. Effect of Fatty Acids and Tocopherols on the Oxidative Stability of Vegetable Oils. Euro J Lipid Sci & Tech 2006, 108, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillani, F.; Raftani Amiri, Z.; Esmaeilzadeh Kenari, R. Assay of Antioxidant Activity and Bioactive Compounds of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Fruit Extracts Obtained by Green Extraction Methods: Ultrasound-Assisted, Supercritical Fluid, and Subcritical Water Extraction. Pharm Chem J 2022, 56, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, B.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M.; Dinda, S.; Zoumpourlis, V.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Velegraki, A.; Markopoulos, C.; Dinda, M. Cornus Mas L. (Cornelian Cherry), an Important European and Asian Traditional Food and Medicine: Ethnomedicine, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology for Its Commercial Utilization in Drug Industry. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2016, 193, 670–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grgurič, L.; Kraner Šumenjak, T.; Kristl, J. Cyanide Contents in Pits of Cherries, Gages and Plums Using a Modified Sensitive Picrate Method. Agricultura 2022, 19, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepaniak, O.; Stachowiak, B.; Jeleń, H.; Stuper-Szablewska, K.; Szambelan, K.; Kobus-Cisowska, J. The Contribution of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Alcoholic Beverages on the Sensory, Nutritional and Anti-Nutritional Characteristics—In Vitro and In Silico Approaches. Processes 2024, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.C.; Kamboj, P.; Lal Kaushal, B.B.; Vaidya, D. Utylization of Stone Fruit Kernels as a Source of Oil for Edible and Non-Edible Purposes. Acta Hortic. 2005, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenkovic-Andjelkovic, A.; Radovanovic, B.; Andjelkovic, M.; Radovanovic, A.; Nikolic, V.; Randjelovic, V. The Anthocyanin Content and Bioactivity of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas) and Wild Blackberry (Rubus Fruticosus): Fruit Extracts from the Vlasina Region. Adv techn 2015, 4, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyściak, P.; Krośniak, M.; Gąstoł, M.; Ochońska, D.; Krzyściak, W. Antimicrobial Activity of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.). Postępy Fitoterapii 2011, 4, 227–231. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın, B.; Yuca, H.; Öztürk, G.; Tekman, E.; Karakaya, S.; Göger, G.; Önal, M.; Demirci, B.; Güvenalp, Z.; Sytar, O. Fruitful Remedies: Analyzing Therapeutic Potencials in Essencial and Fatty Oil, and Aqueous Extracts from Prunus Cerasifera, and Cornus Mas, Using LC-MS and GC-MS Fruitful Remedies. Ankara Ecz. Fak. Derg. 2025, 49, 13–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.; Komarnytsky, S. Cottonseed Oil Composition and Its Application to Skin Health and Personal Care. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1559139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongratanaworakit, T.; Soontornmanokul, S.; Wongareesanti, P. Development of Aroma Massage Oil for Relieving Muscle Pain and Satisfaction Evaluation in Humans. japs 2018, 8, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 9–10% | 10.1–11% | 11.1–12% | 12.1–13% | 13.1–14% | Over 14% |

| Ekzotychnyj*, (syn.Ekzoticzeskiy) | Podolski | Yantarnyi (syn. Yellow) | Yulyush | Shafer | Bolestrashytskii |

| Grenadier | Alyosha, (syn. Alesha’ | ‘Kostia’ | Koralovyj | Dublany | Kresoviak |

|

Yeliena |

Bukovinsky yellow | ‘Samofertylnyj’ | Florianka | Pachoskii | |

| Yevgeniya | Elegantnyi (syn.’Elegant)’ | ‘Siemen’ (‘Semen’) | Kotula | ||

| Mriya Shaydarovoi | Koralovyj Marka | ‘Władimirskij’ (‘Volodymyrskyi’) |

Raciborski | ||

| Naspodevanyj | Lukyanivskyi | Svitlana | |||

| Nikolka | Nezhny | Slovianin | |||

| Oryginalnyj | Radist (syn. Siretski’) | ||||

| Pervenets | Starokyviskyi | ||||

| Priorskij | ‘Vavilovets’ | ||||

| ‘Svetlyachov | Vydubetsky, syn.’Red Star’) | ||||

| Vyshgorodskyi |

| Physical and Chemical Properties of Oil |

Cornelian Cherry [36,59] |

Wild Roses [60,61,62,63,64] |

Apricots [65,66] | Sour Cherry [67,68] |

Peach [69,70,71] |

Plum [71,72,73] |

| The share of the seed (%) | 3.6–12 | 24.4–25.6 | 5.6 | 7–15 | 7.5–12. | 2.3–6 |

| The share of the kernel in the seed (%) | No data | Not applicable | 50–25 | 23–28 | 5–8 | 5–26.7 |

| Content of oil in seed (%) | 1.77–7.94 | 3.27–9.0 | 37.9–47.4 | 17–40 | 30.5–45.8 | 25.5–49 |

| Iodine value [gI2·100 g−1] | 88.106–104.84 | 56.48–190 | 82.2–115 | 92.8–131 | 36.3–110 | 80–120 |

| Density [g·mL−1] | 9.47 | 8.70–9.16 | 8.49–9.36 | 8.81 | 8.7–9.20 | 5.0–11.0 |

| Peroxide number [mmol O2·kg−1] | 0.55–7.36 | 4.70–29.69 | 1.7–15 | 0.99–1.49 | 0.26–2.4 | 1.82–3.75 |

| Acid number [mgKOH·g−1] | 1.87 | 0.59–6.12 | 0.2–4 | 0.9–1.36 | 0.2–1.1 | 0.34–2.24 |

| Saponification number [mgKOH·g−1] | 146.45–256.41 | 175–210 | 161–195 | 184–194 | 101–201 | 150–198 |

| Free Fatty acid (%) | 0.94 | 0.59–1.61 | 1.0 | 0.1–0.93 | 0.81–0.99 |

| Macroelements | Microelements | Metals |

| Ca 2647-4154 | Fe 82 | Al. 2.6 |

| P 977-2615 | Zn 24 | Pb 1.51 |

| K 844-3270 | Cu 4–8 | Ni 0,39 |

| S 462 | Mn 2.3 | As < 0.3 |

| Mg 394-597 | Cr 0.47 | Cd < 0.01 |

| N 9 | Se < 0.2 | Hg 0.004 |

| Fatty Acid | Cornelian Cherry[44,77,78] | Wild Roses [60,79,80] | Apricots [66] |

Sour Cherry [67] |

Peach [69,70] |

Plum [71,73] |

| C 8: 0 Caprylic acid | 0.0–0.07 | 0.06 | 0.01 | |||

| C10:0 Capric (Decanoate) acid | 0.0–0.02 | 0.07 | 0.02–0.03 | |||

| C12:0 Lauric acid | 0.0 | 0.11 | ||||

| C14:0 Myristic acid | 0.01–0.07 | 0.03–0.052 | 0.04–0.12 | 0.08 | 0.1–0.16 | 0.05 |

| C16:0 Palmitic acid | 3.5–8.05 | 2.0–7.91 | 3.0–10.0 | 6.54–13.3 | 5.63–9.29 | 3.0–7.5 |

| C17:0 Margaric (Heptadecanoic) acid | 0.11–0.83 | 0.05–0.12 | 0.05–0.08 | 0.13–0.17 | 0.02–0.08 | |

| C 18:0 Stearic acid | 1.37–2.90 | 1.04–5.79 | 0.5–4.0 | 2.3–4.0 | 1.18–3.57 | 1.5 |

| C 20:0 Arachidic acid | 0.02–1.8 | 0.29–26.52 | 0.08–0.20 | 0.75–0.98 | 0.03–0.31 | 0.1 |

| C 21:0 Heneicosylic | 0.01–0.02 | 4.66–19.02 | ||||

| C 22:0 Behenic acid | 3.19–13.36 | 0.02–0.1 | 0.05 | |||

| C 24:0 Lignoceric acid | 0.0–0.01 | 16.01 | 0.14 | 0.02 | ||

| ΣSFA (Saturated Fatty Acid) | 7.75–8.54 | 7.68–59.95 | 7.88–11.31 | 16.64–18.34 | 8.02–13.26 | |

| C 14:1 Myristoleic acid | 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | ||

| C16:1, n-7 Palmitoleic acid | 0.02–0.05 | 0.03–35.68 | 0.5- 1.5 | 0.5–0.8 | 0.25–0.56 | 1.4 |

| C17:1 cis Heptadecenoic acid | 0.0–0.02 | 0.1–0.15 | 0.1 | 0.11–0.20 | 0.1 | |

| C18:1 Oleic acid | 15.7–23.69 | 3.89–20.3 | 46.06–72 | 35.45–55.2 | 39.07–72.0 | 59.5–70.4 |

| C20:1, n-9 Eicosaenoic acid | 0.01–0.03 | 0.3–0.70 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.03–0.06 | 0.1 |

| C 22:1 Erucic acid | 0.0 0.01 | 0.32–6.70 | 0.03 | 0.05 | ||

| C 24:1 Nervonic acid | 0.0 | |||||

| ΣMUFA (Monounsaturated Fatty Acid) | 15.74–17.77 | 15.03–47.26 | 46.28–69.00 | 36.14–56.58 | 62.16–69.89 | |

| C 18:2, n-6 Linoleic acid (LA) | 60.17–75.0 | 24.53–55.70 | 20–41.57 | 23.3–42.34 | 13.06–48.4 | 18.8–27.1 |

| C 18:3 α-Linolenic acid (ALA) | 1.3–1.5 (14.70[77]) | 4.73–38.0 | 0.11–0.18 | 0.13 | 0.05–0.3 | 0.1 |

| C 20:2 Eicosadienoic acid | 0.0–0.01 | 0.13–0.16 | ||||

| C 20:4 Arachidonic acid | 0.0 | 7.01–16.02 | ||||

| C 20:5 Eicosapentaenoic acid | 0.0–0.01 | |||||

| C 22:4 Adrenic acid | 0.0–0.01 | |||||

| C 22:5 Osbond acid | 0.0 | |||||

| ΣPUFA (Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid) | 74.07–75.80 | 25.28–68.45 | 22.05–41.75 | 23.8–52.66 | 22.01–78.59 | |

| ΣUFA (Unsaturated Fatty Acid) | 91.46–92.25 | 40.65–92.32 | 78.77–88.8 | 52.68–92.10 |

| VegetableOil | C16:0 | C18:0 | C18:1 | C18:2 | C18:3 | C20:1 | C22:1 | Omega-6/Omega-3 |

| Palm oil | 44.3 | 4.7 | 39.2 | 10.1 | 0.3 | 54.3:1 | ||

| Soybean | 10.6 | 3.8 | 23.3 | 55.1 | 6.9 | 0.3 | No data | 7.4:1 |

| Rapeseed | 4.6 | 1.5 | 64.1 | 19.7 | 8.7 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 2.2:1 |

| Sunflower | 5.6 | 3.8 | 25.6 | 64.7 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 323:1 |

| Palm kernel oil | 7.8 | 2.4 | 15.0 | 4.9 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 17.5:1 | |

| Cottonseed oil | 24.7 | 3.1 | 15.4 | 53.9 | 7.2:1 | |||

| Peanut oil | 10 | 2.4 | 43 | 36 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 402:1 | |

| Coconut oil | 8.6 | 2.5 | 6.3 | 1.7 | 0 | 168:1 | ||

| Olive oil | 11.5 | 2.2 | 68.8 | 10.5 | 0.67 | 16:1 | ||

| Cornelian cherry kernels | 5.9 | 1.7 | 16.7 | 61.8 | 12.78 | 0.02 | 0.005 | 3.5:1 |

| Oil | The dominant fatty acid in the oil | Number of double bonds | Oxidation rate |

| Palm oil | C16:0 Palmitic acid | 0 | 1 |

| Olive oil, Rapeseed oil, Oils from apricot, sour cherry, peach and plum | C18:1 Oleic acid | 1 | 10 |

| Cornelian cherry kernel oil, Soybean oil, Sunflower oil | C 18:2, n-6 Linoleic acid | 2 | 100 |

| Seed wild roses oil | C 18:3 α-Linolenic acid | 3 | 250 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).