1. Introduction

Oral cancer represents a major health burden worldwide and is among the leading causes of cancer-related death in Taiwan. Despite the implementation of nationwide oral cancer screening, the most comprehensive of their kind globally, Taiwan continues to face persistent challenges of tumor recurrence and metastasis [

1,

2]. These clinical realities highlight the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies that can effectively prevent relapse and improve long-term outcomes.

Stem cells possess unique abilities to self-renew and differentiate into various cell types, in both normal development and disease. In cancer, the self-renewal and differentiation of stem cells has been linked to therapy resistance and tumor progression. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) were first demonstrated in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), where a distinct subpopulation of cells was found to be capable of initiating leukemia in immunodeficient mice [

3,

4,

5]. Since then, similar “stem cell-like” subpopulations have been identified in solid tumors, including breast, colorectal, and brain cancers [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. CSCs exhibit the ability to self-renew, initiate tumor growth, and sustain progression, and are now recognized as key drivers of cancer initiation, maintenance, recurrence, and metastasis [

11,

12,

13]. Their identification and characterization hold great promise for advancing our understanding of tumor biology, as they may explain differential therapeutic responses and illuminate cell survival mechanisms in cancer [

12,

14,

15].

Because CSCs contribute to tumor heterogeneity and therapy resistance through their ability to self-renew and differentiate within a tumor, it is essential to study them in physiologically relevant contexts. Conventional two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures on polystyrene surfaces provide a simplified model that is easy to use but fails to capture the complex cell–cell interactions and microenvironment of tumors in vivo [

16,

17]. By contrast, three-dimensional (3D) culture systems, such as spheroid models, allow cancer cells to proliferate in all directions and form extracellular matrix components and cell junctions that better recapitulate in vivo conditions. This is particularly important for CSC research, as 3D models enable more accurate investigations of tumorigenesis, growth, metastasis, and recurrence [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Thus, 3D cell culture systems offer powerful tools for identifying CSCs and elucidating the mechanisms that drive tumor biology.

ENOX2, also known as tumor-associated NADH oxidase (tNOX) or COVA1, is a cancer cell surface protein with both NADH oxidase and protein disulfide–thiol exchange activities. It has been implicated in promoting proliferation, growth, migration, and invasion across multiple cancer types [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. By catalyzing the oxidation of NADH to NAD⁺, ENOX2 influences the activity of SIRT1, a member of the NAD⁺-dependent sirtuin family of deacetylases. SIRT1 critically regulates key cellular processes, including metabolism, differentiation, aging, and stem cell maintenance [

30,

31,

32,

33]. In this context, SIRT1 acts through the deacetylation of transcription factors, such as Oct4, Nanog, and SOX2, to balance self-renewal and differentiation and thereby sustain pluripotency [

34,

35,

36,

37]. Given these essential functions, the potential involvement of the ENOX2-SIRT1 axis in regulating stemness warrants deeper investigation.

In this study, we focused on oral cancer as a clinically urgent and regionally relevant disease model. Using 3D spheroid cultures, we examined the role of ENOX2 in maintaining stem-like properties in oral cancer cells. We further evaluated the impact of ENOX2 overexpression or knockdown on CSC characteristics in vitro and in vivo. Our results provide new insights into the therapeutic potential of targeting ENOX2 in CSC-directed cancer treatments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The following antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA, USA): anti-SIRT1, anti-Nanog, anti-SOX2, anti-Oct4, anti-ABCG2, anti-ABCB1, anti-ALDH1, anti-PKCδ, anti-CD44, anti-133, anti-c-Myc, and anti-GST. Rabbit anti-human CD133 (prominin-1) and mouse anti-rabbit IgG-FITC antibodies were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Burlington, MA, USA). Mouse anti-human CD44 conjugated with FITC was sourced from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The anti-β-actin antibody was from Millipore Corp. (Temecula, CA, USA). The antisera to ENOX2 used for immunoblotting were generated as previously described [

38]. Unless otherwise specified, anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies, along with other chemicals, were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Burlington, MA, USA).

2.2. Cell Culture and Transfection

SAS (human squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue) and HSC-3 (human tongue squamous cell carcinoma) cells were kindly provided by Dr. Yuen-Chun Li (Department of Biomedical Sciences, Chung Shan Medical University, Taiwan). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 50 µg/ml streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2, and the medium was refreshed every 2-3 days.

Cells were transiently transfected with GST-ENOX2 or GST (control) using the jetPEI transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Polyplus-transfection SA, Illkirch Cedex, France). ON-TARGETplus ENOX2 siRNA and non-targeting control siRNA were purchased from Thermo Scientific, Inc. (Grand Island, NY). For siRNA transfection, cells were seeded in 10-cm dishes, allowed to attach overnight, and then transfected with ENOX2 siRNA or control siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Reagent (Gibco/BRL Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Spheroid Formation Assay

When cell confluence reached around 80 %, cells were detached using 1× trypsin–EDTA. After removal of serum, the cells were suspended in DMEM supplemented with 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF) and 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2) (Trust Gene Biotech LTD., Taiwan). Cells were then seeded into ultra-low attachment 24-well plates (Corning, NY, USA) at a density of 1,000 cells per well and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (polyHEMA) (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was prepared at 60 mg/mL in 95% ethanol at 65 °C for 2-3 h. Culture dishes were coated with the polyHEMA solution and dried under UV for 45 min. Cells were then plated in polyHEMA-coated 12-well plates (Corning, NY, USA) at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well and incubated at 37 °C with 5 % CO2.

2.4. Real-Time Cell Proliferation Monitoring Using the xCELLigence System

For continuous monitoring of cell proliferation, Flag-vector, Flag-ENOX2, GST-vector, and GST-ENOX2 overexpressed cells (1×10

4 cells/well) were seeded into E-plates. After incubation for 30 min at room temperature to allow cell attachment, the plates were transferred to the xCELLigence System (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Cells were cultured for 4 days, and impedance was recorded every hour, as previously described [

39]. Cell impedance was expressed as the cell index (CI), calculated as CI = (Z

i − Z

0) [Ohm]/15[Ohm], where Z

0 represents background resistance and Z

i the resistance at a given time point. The normalized cell index was obtained by dividing the cell index at a given time point (CI

ti) by that at the designated normalization time (CI

nml_time).

2.5. Flow Cytometry Analysis of Cancer Stem Cell Surface Markers

Spherical cells obtained from the spheroid formation assay of SAS and HSC-3 cells were first verified for stem cell surface markers prior to subsequent experiments, to confirm enrichment of cancer stem cell populations after sphere culture. Tumor spheres were treated with 1:1 diluted 2.5% Trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen, Australia) for 5 min at 37 °C, washed, and dissociated by repeated pipetting. A total of 1 × 105 cells were then stained with rabbit anti-human CD133 (prominin-1) antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), and mouse anti-human CD44-FITC (Invitrogen, Australia). For CD133 staining, mouse anti-rabbit IgG-FITC (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the secondary antibody. After three washes with 1% PBS, cells were fixed in 1% PBS, and the fluorescence intensity was analyzed using a Beckman Coulter CytoFLEX LX flow cytometer (Brea, CA, USA).

2.6. Quantification of Intracellular NAD+/NADH Ratio

Intracellular levels of oxidized and reduced NAD were quantified using an NADH/NAD⁺ Quantification Kit (BioVision Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 2 × 106 cells were washed with cold PBS, pelleted, and extracted by two freeze–thaw cycles in 400 µL NADH/NAD⁺ extraction buffer. The extracts were vortexed and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 min. Supernatants (200 µL) containing NADH/NAD⁺ were transferred to microcentrifuge tubes, heated at 60 °C for 30 min to decompose NAD⁺ while preserving NADH, and immediately placed on ice. Samples were centrifuged again, and the supernatants were transferred to a 96-well plate. NAD⁺ standards and cycling mix were prepared following the manufacturer’s protocol. A 100-µL aliquot of reaction mix was added to each well containing NADH standards or samples and incubated at room temperature for 5 min to convert NAD⁺ to NADH. Subsequently, the NADH developer solution was added, and the reaction was incubated at room temperature for 15–30 min. Reactions were terminated with 10 µL Stop solution, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

2.7. Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis

For immunoprecipitation, protein extracts from cells grown in 100-mm dishes were incubated with 20 µL Protein G agarose beads (for rabbit antibodies) for 1 h at 4 °C with rotation to pre-clear nonspecific binding. GST, SOX2 antibody, or control IgG was then added to the beads in 500 µL lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 100 mM NaCl; 5 mM EDTA; 2 mM PMSF; 10 ng/mL leupeptin; 10 µg/mL aprotinin) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with rotation. The beads were collected by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 2 min at 4 °C, and 80 µL of supernatant was reserved as input lysate. Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, and bound proteins were eluted for subsequent Western blot analysis.

For Western blotting, cell lysates were prepared using the same lysis buffer. Equal amounts of protein (40 µg) were resolved by SDS–PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH, USA). Membranes were blocked, washed, and incubated with the indicated primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.8. Xenograft Tumor Formation Assay in Mice

Specific pathogen-free (SPF) ASID mice were purchased from the National Labora-tory Animal Center (Taipei, Taiwan). All animal experiments were conducted under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National Chung Hsing University (NCHU IACUC: 109-153). For the gain-of-function study, mice were divided into three groups and subcutaneously inoculated with 100 µl PBS con-taining SAS cells transfected with vector or GST-ENOX2 at doses of 1 × 106 (N=3 per group), 2 × 104 (N=5 per group), or 1 × 104 (N=3 per group). For the loss-of-function study, mice were divided into two groups and subcutaneously inoculated with 100 µl PBS containing 1 × 106 SAS cells (N=3 per group) transfected with siRNA-control or siR-NA-ENOX2. Tumor size was measured every 2 days, and tumor volume was calculated using the formula: Volume = length × width2 × 0.5. Statistical significance of differences in tumor size was determined using one-way ANOVA.

2.9. Human Tissue Specimens

Two pairs of cancer tissues and their corresponding adjacent normal tissues were obtained from Changhua Christian Hospital, Taiwan (CCH IRB No. 130616). The diagnosis of oral cancer was confirmed by histological examination of hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. Immediately after surgical resection, patient specimens were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently used for Western blot analysis.

2.10. Statistics

All data are expressed as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. Group comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by appropriate post hoc tests (e.g., LSD or t-test). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Expression Levels of ENOX2, SIRT1, and SOX2 Are Upregulated in Patients with Oral Cancer

Oral cancer is associated with high morbidity and mortality worldwide. Previous studies showed that ENOX2 contributes to cancer progression by regulating SIRT1, thereby implicating it in tumor development [

25,

28,

29,

40,

41,

42,

43]. However, the expression of ENOX2 in oral cancer tissues relative to normal tissues has not been fully characterized. To address this, we conducted

in silico analyses using publicly available databases to assess ENOX2 expression in patient-derived oral cavity tumors. Databases providing high-throughput mRNA and protein data, including UALCAN, cBioPortal, and the Human Protein Atlas, were utilized to compare ENOX2 expression in tumor tissues versus matched normal counterparts. Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Pan-Cancer dataset revealed that ENOX2 transcript expression was significantly elevated in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) tissues compared with normal tissues, with correlations seen across different tumor stages and grades (

Figure 1A). Similarly, data from the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) indicated that ENOX2 protein levels were higher in HNSCC tumor tissues than in normal tissues, with observable but non-significant trends for correlation seen across tumor grades (

Figure 1B). In line with these findings, Human Protein Atlas (

https://www.proteinatlas.org) data demonstrated elevated ENOX2 expression in head and neck cancer cell lines such as HSC-3 (

Figure 1C). Furthermore, heatmap analysis of the Human Protein Atlas dataset showed that ENOX2 expression was upregulated across multiple malignancies, including head and neck cancer (

Figure 1D). These findings suggest that ENOX is upregulated in HNSCC and may contribute to their development and progression).

Similar to the results obtained for ENOX2, the transcript levels of SIRT1 and SOX2 were also elevated in HNSCC tumor tissues compared with normal tissues across different tumor grades (

Figure 2A).

Sex-determining region Y box 2 (SOX2) is a well-established transcription factor involved in stem cell maintenance and has been implicated in HNSCC stemness regulation [

44,

45]. To further evaluate the clinical relevance of these proteins in oral cancer, we analyzed paired patient specimens obtained from Changhua Christian Hospital in Taiwan. In one representative case, ENOX2 expression was higher in oral tumor tissues than in the adjacent non-tumor tissues (

Figure 2B). Consistent with the function of ENOX2 as an upstream regulator of SIRT1, increased protein levels of SIRT1 were observed in these tumor tissues (

Figure 2B). SOX2 was likewise upregulated in tumor tissues relative to non-tumor counterparts (

Figure 2B). Pearson correlation analysis of the patient data demonstrated positive correlations between ENOX2 and SIRT1, as well as between ENOX2 and SOX2 (

Figure 2C). Moreover, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis using a pan-cancer RNA-seq dataset (

https://www.kmplot.com/) showed that high-level expression of ENOX2 (all stages, female group), SIRT1 (stage III + IV, female group), and SOX2 (all stages, female group) was significantly associated with poor overall survival in female patients with head and neck cancer (

Figure 2D). These associations were not observed in the overall patient cohorts, suggesting that gender may influence survival outcomes. Collectively, these findings support the existence of an ENOX2–SIRT1–SOX2 regulatory axis that contributes to stemness and tumor progression in oral cancer.

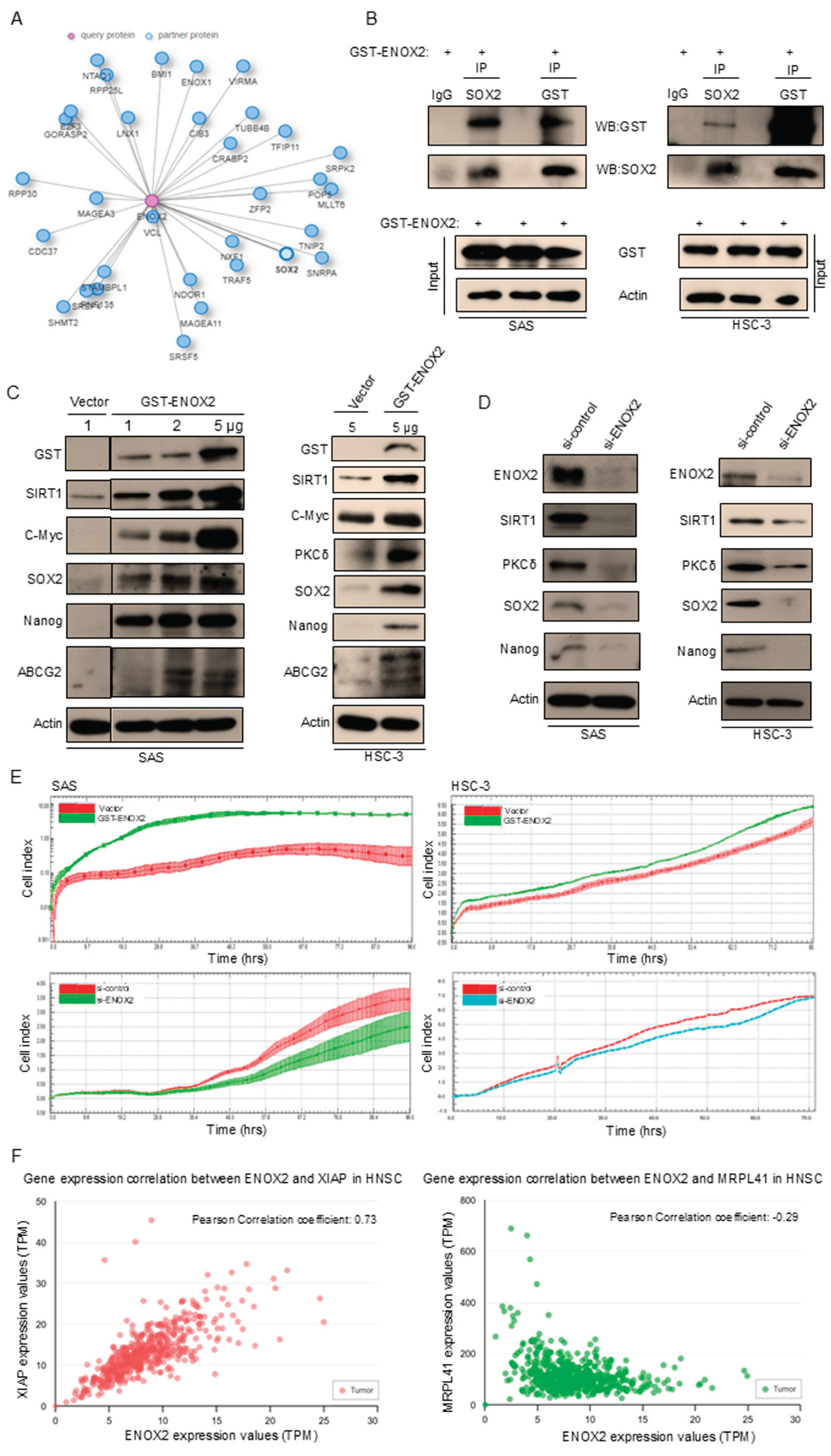

3.2. ENOX2 Stimulates Stemness and Cell Proliferation in Oral Cancer Cells

Given the positive correlation between ENOX2 and SOX2, we investigated the relationship between these two proteins in oral cancer. SOX2 is a transcription factor that is crucial for maintaining the self-renewal and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells, while ENOX2 is a growth-related protein that contributes to cancer regulation [

24,

26,

46,

47]. Analysis using the Integrated Interaction Database (IID)(

https://iid.ophid.utoronto.ca/) suggested a potential association between ENOX2 and SOX2 (

Figure 3A). To test whether ENOX2 physically interacts with SOX2, we performed a co-immunoprecipitation assay. Our results showed that ENOX2 physically interacted with SOX2 in two oral cancer cell lines, SAS (wild-type p53) and HSC-3 (mutant p53), although the interaction appeared weaker in HSC-3 cells (

Figure 3B). Because SOX2 is implicated in HNSCC stemness regulation, we next investigated whether ENOX2 influences stemness-related characteristics in these oral cancer cell lines. Overexpression of ENOX2 markedly increased the expression levels of stemness markers, including SIRT1, c-Myc, SOX2, Nanog, and ABCG2, in both SAS and HSC-3 cells (

Figure 3C). Conversely, ENOX2 knockdown reduced the expression of SIRT1, SOX2, and Nanog (

Figure 3D), suggesting that ENOX2 may contribute to maintaining stemness in oral cancer cells. Consistent with previous reports in cancer models [

28,

39,

42], ENOX2 overexpression increased SIRT1 levels, whereas ENOX2 knockdown decreased SIRT1 expression. We also found that the expression of PKCδ, a serine/threonine kinase of the PKC family, was modulated by both ENOX2 overexpression (

Figure 3C) and knockdown (

Figure 3D). Given that ENOX2 can be phosphorylated by PKCδ and thereby modulate cell proliferation and migration [

48], it remains unclear how ENOX2 influences the translational regulation of PKCδ. In line with previous studies showing that ENOX2 regulates cancer cell growth and migration [

26,

27,

48,

49], we found that ENOX2 overexpression promoted cell proliferation, whereas ENOX2 depletion reversed this effect in both SAS and HSC-3 cells (

Figure 3E). Because ENOX2 is also linked to cell death regulation [

25,

40,

41,

43,

50,

51,

52], we next explored genes correlated with ENOX2 in HNSCC datasets. Notably, XIAP, an inhibitor of apoptosis, was positively correlated with ENOX2 expression, whereas MRPL41, an apoptosis inducer, was negatively correlated (

Figure 3F). These findings indicate that ENOX2 not only promotes cell proliferation and stemness but also contributes to cell fate determination by modulating the balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic pathways.

3.3. Sphere Formation and Stemness Characteristics in p-53 Functional SAS and p-53 Mutated HSC-3 Cells

Sphere formation, the aggregation of cells into 3D structures under non-adherent conditions, is an

in vitro method that is widely used to assess stem-like properties. Consistent with a previous report [

53], both p53-functional SAS and p53-mutant HSC-3 oral cancer cell lines formed spheres at varying seeding densities in our system (

Figure 4A). Compared with adherent monolayer cultures, spheroid cells exhibited elevated levels of expression of ENOX2, SIRT1, and the stemness-associated markers, SOX2, Nanog, and Oct4 (

Figure 4B). Notably, both the protein level and enzymatic activity of ENOX2, as reflected by the NAD⁺/NADH ratio, were markedly higher in spheroids than in adherent cells (

Figure 4B, C), supporting the idea that the spheroids were enriched with a stem-like subpopulation.

Under non-adherent, serum-free conditions, spheroid cultures provide a selective microenvironment that favors the survival and expansion of cells with stem-like characteristics [

54]. Within these cultures, a subpopulation of cancer cells with stem-like features emerges, often defined by increased expression of specific surface markers. To validate this, 7-day SAS (

Figure 5A) and HSC-3 (

Figure 5B) spheroids were dissociated into single cells and analyzed by flow cytometry for CD44, a well-recognized CSC marker, and CD138 (syndecan-1), which is associated with epithelial and tumorigenic properties. Both markers were significantly upregulated in spheroid cultures compared with adherent cells (

Figure 5), supporting the enrichment of a stem-like subpopulation.

3.4. ENOX2 Regulates Sphere Formation and Stemness in Oral Cancer Cells

We observed that both ENOX2 and SIRT1 were upregulated in spheroid cultures, a system that selectively enriches for cancer stem-like cells. This suggests that their elevated expression is functionally linked to sustaining CSC properties such as self-renewal and survival, rather than representing a downstream byproduct of spheroid growth or the initiation of stemness traits. To further investigate the function of ENOX2 in stem-like cancer cell populations, we transiently overexpressed ENOX2 in two oral cancer cell lines: SAS cells (p53-functional) and HSC-3 cells (p53-mutant). ENOX2 overexpression markedly enhanced sphere formation, which is a hallmark of CSC self-renewal (

Figure 6A, left panel), and increased the expression of SIRT1 and stemness-associated markers, SOX2, Nanog, and Oct4 (

Figure 6A, right panel). Conversely, RNAi-mediated knockdown of ENOX2 reduced sphere formation (

Figure 6B, left panel) and downregulated SIRT1, SOX2, Nanog, and Oct4 (

Figure 6B, right panel). These molecular changes were accompanied by signs of differentiation, supporting the notion that ENOX2 is required for the maintenance of stem-like traits. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that ENOX2 promotes CSC-like properties in oral cancer cells, at least in part through regulation of SIRT1 and stemness–associated transcription factors. Loss of ENOX2 disrupts these pathways and may shift cells toward differentiation, highlighting ENOX2 as a potential therapeutic target in oral cancer.

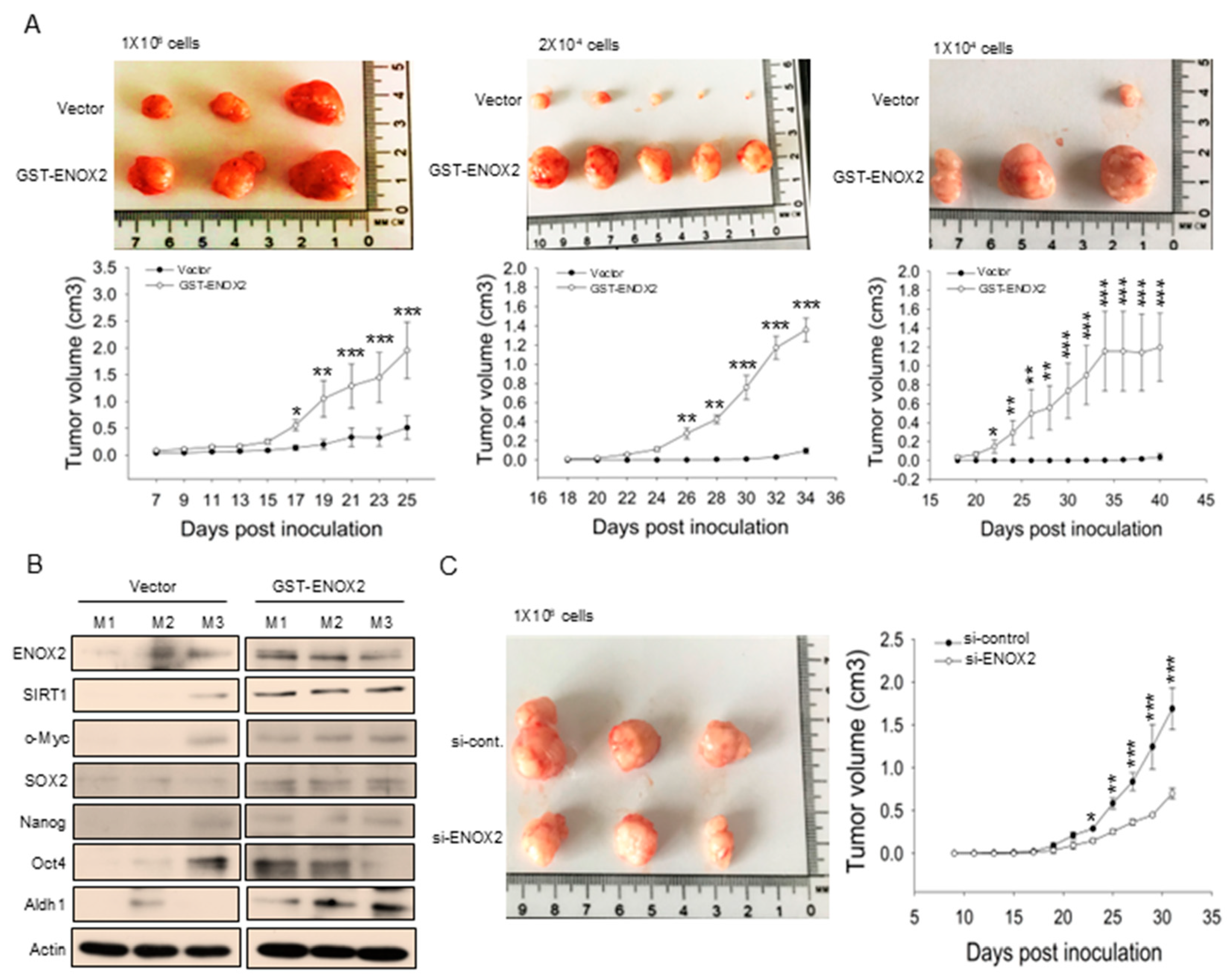

3.5. ENOX2 Drives Oral Cancer Stem Cell Formation In Vivo

Stem cells are increasingly being recognized as drivers of tumor development and progression. In a previous study, we showed that ENOX2 knockdown in melanoma cells significantly inhibited tumor formation [

29]. Building on this, we herein demonstrated that ENOX2 overexpression promotes stem-like properties, whereas ENOX2 silencing suppresses stemness in oral cancer cells

in vitro. To assess the role of ENOX2

in vivo, we employed xenograft mouse models. Spheroid-derived oral cancer cells transiently overexpressing ENOX2 exhibited markedly enhanced tumor-initiating capacity compared with vehicle control cells (

Figure 7A). Consistent with this increased tumor growth, tumors derived from ENOX2-overexpressing cells expressed significantly higher levels of stemness-associated markers, as determined by Western blot analysis (

Figure 7B). Conversely, mice inoculated with ENOX2-knockdown spheroid cells displayed substantially smaller tumor volumes relative to controls (

Figure 7C). Collectively, our findings indicate that ENOX2 enhances tumor initiation and stemness in oral cancer cells, while its depletion impairs these properties. These results support the notion that ENOX2 plays a critical role in maintaining cancer stem cell characteristics and promoting tumor progression

in vivo.

3.6. The ENOX2 Signaling Modulator, Capsaicin, Inhibits Sphere Formation and Downregulates Stemness Marker Expression in Oral Cancer Cells In Vitro

Having established that ENOX2 promotes oral cancer stemness and tumor growth both

in vitro and

in vivo, we next explored whether targeting this pathway could represent a therapeutic strategy. Capsaicin, a dietary bioactive compound from chili peppers, has been reported to exert anti-cancer effects, including the ability to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in cancer cells through the ENOX2–SIRT1 axis [

29,

50]. Beyond oncology, capsaicin has also emerged as an important molecule in stem cell research [

55]. For example, it reportedly inhibits the differentiation of bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) into adipocytes by inducing apoptosis, suppressing adipocyte-specific gene expression, and reducing BMSC proliferation [

56]. Based on these observations, we investigated whether capsaicin could suppress oral cancer stem-like properties by disrupting the ENOX2–SIRT1–SOX2 regulatory axis. Indeed, we found that the application of capsaicin at 200 µM and 400 µM significantly reduced sphere formation in SAS cells (

Figure 8A). Western blot analysis further revealed that capsaicin suppressed the expression levels of ENOX2, SIRT1, and the stemness-associated markers, SOX2, Nanog, and Oct4 (

Figure 8B). These findings suggest that inhibiting the ENOX2–SIRT1–SOX2 axis by capsaicin may impair cancer stem-like properties, highlighting a potential therapeutic strategy for head and neck cancer.

4. Discussion

Oral cancer remains a major health concern, particularly in Taiwan, where a nationwide screening program has been implemented, yet recurrence and metastasis remain formidable challenges [

1,

2]. These clinical realities underscore the need for therapeutic approaches that move beyond early detection to directly target mechanisms of relapse. The recognition of cancer stem cells (CSCs) has provided critical insight into this problem, as their intrinsic capacity for self-renewal and pluripotency underlies tumor persistence, therapy resistance, and disease recurrence [

57,

58]. Among the transcriptional regulators that orchestrate stemness, SOX2 plays a central role within a network of pluripotency factors (e.g., Oct4 and Nanog) to sustain an undifferentiated state and govern cell fate [

59,

60,

61,

62]. Our present findings identify ENOX2 as a novel upstream regulator of SOX2 in oral cancer cells. Gain-of-function experiments demonstrated that ENOX2 promotes a stem-like phenotype by enhancing SOX2 expression, at least in part through upregulation of SIRT1, which is an NAD⁺-dependent protein deacetylase that functions as a central regulator of embryonic and somatic stem cell function [

63,

64]. Importantly, SIRT1 is a versatile regulator of

SOX2, acting through both post-translational and transcriptional mechanisms to preserve SOX2 stability and sustain stemness [

35,

65]. In line with these observations, ENOX2 knockdown reduced the expression levels of SIRT1, SOX2, and pluripotency markers, and increased signs of differentiation.

In vivo, ENOX2 overexpression increased the expression levels of SIRT1 and SOX2 in tumors, further reinforcing the notion that ENOX2 contributes to maintaining CSC-like traits. The ENOX2-SIRT1 regulatory axis has also been implicated in multiple cancer-related processes, including proliferation, migration, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), apoptosis, and autophagy [

28,

29,

39,

40,

43,

66,

67]. Our data extend this functional repertoire by establishing a direct connection between ENOX2 and CSC maintenance through the regulation of SOX2. This highlights the ENOX2–SIRT1–SOX2 axis as not only a driver of oral cancer stemness but also as a potential therapeutic vulnerability. Given the central role of CSCs in recurrence, metastasis, and therapy resistance, targeting this pathway may represent a promising strategy to suppress stemness-associated phenotypes and improve clinical outcomes in oral cancer.

A previous work has shown that ENOX2 is phosphorylated by PKCδ and participates in cancer cell proliferation

[48]. PKCδ, a serine/threonine kinase of the PKC family, has been implicated in diverse cellular processes, including tumorigenesis and CSC regulation [

68,

69]. Together, the previous and present findings highlight the complexity of ENOX2 regulation and its potential role in cancer stemness and progression, underscoring the broader functional diversity of ENOX2 as a growth-related protein. Our mechanistic findings gain additional translational significance when framed in the context of capsaicin, which is a well-documented dietary bioactive with anticancer properties [

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75]. Several studies have shown that capsaicin directly engages with ENOX2, promoting its degradation via the ubiquitin–proteasome and autophagy–lysosome pathways, thereby inhibiting SIRT1

activity and leading to cancer cell death [

29,

50,

51]. Beyond this direct effect, capsaicin has been shown to suppress cancer stemness in diverse models: In hepatocarcinogenesis, it destabilizes SOX2 through the SIRT1–SOX2 axis, reducing hepatic progenitor cell activation and tumorigenesis [

76]; in osteosarcoma CSCs, capsaicin reduces sphere-forming ability and downregulates pluripotency markers such as SOX2 and EZH2

[77,78,79]. These data align with and bolster our results, collectively suggesting that targeting the ENOX2–SIRT1–SOX2 axis with capsaicin may offer a novel strategy for eradicating CSCs and mitigating recurrence in oral cancer. Nevertheless, limitations remain. Our analyses relied in part on publicly available proteomics datasets, which may be influenced by sample size, patient heterogeneity, and tumor microenvironmental context. Additional validation in larger and clinically diverse cohorts will be essential to establish the robustness and translational applicability of our findings.

Taken together, our findings identify ENOX2 as a central regulator of CSC-like traits in oral cancer, acting through the SIRT1-SOX2 axis. These insights not only expand the mechanistic repertoire of ENOX2 but also suggest a tractable therapeutic target for suppressing stemness-associated phenotypes. Future work should clarify the molecular regulation of ENOX2, evaluate its utility as a biomarker of stemness and therapeutic response, and explore the translational potential of targeting this pathway, alone or in combination with bioactive compounds such as capsaicin, to improve clinical outcomes in oral cancer.

5. Conclusions

In summary, ENOX2 overexpression is a critical determinant of stem cell properties in oral cancer cells. By modulating SIRT1 expression and interacting with SOX2, ENOX2 sustains CSC populations and contributes to tumor persistence. Disrupting the ENOX2–SIRT1–SOX2 axis may therefore represent an effective therapeutic approach to eradicate CSCs and improve patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

For Conceptualization was carried out by C.W.W. and P.J.C.; methodology was developed by C.W.W., A.I., and Y.T.S.; validation was performed by C.W.W., A.I., and P.J.C.; investigation was undertaken by C.W.W. and Y.T.S.; resources were provided by Y.T.S., C.F.C., M.K.C., and P.J.C.; data curation was handled by C.W.W. and A.I.; the original draft was prepared by C.W.W., A.I., and P.J.C.; review and editing were performed by M.K.C. and P.J.C.; visualization was carried out by A.I. and P.J.C.; supervision was provided by M.K.C. and P.J.C.; project administration was managed by P.J.C.; and funding acquisition was secured by C.F.C., M.K.C. and P.J.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the National Science and Technology Council, ROC (Grant numbers NSC 102-2320-B005-008, MOST-109-2314-B-816-001-MY2, and MOST 109-2320-B-005-010), and by the National Chung Hsing University and Changhua Christian Hospital, Taiwan (Grant number NCHU-CCH-11105).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National Chung Hsing University (NCHU IACUC: 109-153). In addition, two pairs of cancer tissues and their corresponding adjacent normal tissues were obtained from Changhua Christian Hospital, Taiwan (CCH IRB No. 130616).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the National Science and Technology Council, ROC (Grant numbers NSC 102-2320-B005-008, MOST-109-2314-B-816-001-MY2, and MOST 109-2320-B-005-010), and by the National Chung Hsing University and Changhua Christian Hospital, Taiwan (Grant number NCHU-CCH-11105).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 2D |

two-dimensional |

3D

CSCs

ENOX2, tNOX

Sirtuin 1, SIRT1 |

three-dimensional

Cancer stem cells

Tumor-associated NADH oxidase

Silent information regulator 1 |

| SOX2 |

Sex-determining region Y box 2 |

TCGA

HNSCC

CPTAC |

The Cancer Genome Atlas

Neck squamous cell carcinoma

Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium |

References

- Tsai, E.T.; Walker, B.; Wu, S.C. Can oral cancer screening reduce late-stage diagnosis, treatment delay and mortality? A population-based study in Taiwan. Bmj Open 2024, 14, ARTN e086588. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.C.; Kung, P.T.; Wang, S.T.; Huang, K.H.; Liu, S.A. Beneficial impact of multidisciplinary team management on the survival in different stages of oral cavity cancer patients: results of a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Oral Oncol 2015, 51, 105-111. [CrossRef]

- Uckun, F.M.; Sather, H.; Reaman, G.; Shuster, J.; Land, V.; Trigg, M.; Gunther, R.; Chelstrom, L.; Bleyer, A.; Gaynon, P., et al. Leukemic-Cell Growth in Scid Mice as a Predictor of Relapse in High-Risk B-Lineage Acute Lymphoblastic-Leukemia. Blood 1995, 85, 873-878. [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, D.; Dick, J.E. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nature medicine 1997, 3, 730-737, doi:DOI 10.1038/nm0797-730.

- Lapidot, T.; Sirard, C.; Vormoor, J.; Murdoch, B.; Hoang, T.; Caceres-Cortes, J.; Minden, M.; Paterson, B.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Dick, J.E. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature 1994, 367, 645-648. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajj, M.; Wicha, M.S.; Benito-Hernandez, A.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 3983-3988. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C.A.; Pollett, A.; Gallinger, S.; Dick, J.E. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature 2007, 445, 106-110. [CrossRef]

- Ricci-Vitiani, L.; Lombardi, D.G.; Pilozzi, E.; Biffoni, M.; Todaro, M.; Peschle, C.; De Maria, R. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature 2007, 445, 111-115. [CrossRef]

- Dalerba, P.; Dylla, S.J.; Park, I.K.; Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Cho, R.W.; Hoey, T.; Gurney, A.; Huang, E.H.; Simeone, D.M., et al. Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 10158-10163. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Hawkins, C.; Clarke, I.D.; Squire, J.A.; Bayani, J.; Hide, T.; Henkelman, R.M.; Cusimano, M.D.; Dirks, P.B. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature 2004, 432, 396-401. [CrossRef]

- Dontu, G.; Al-Hajj, M.; Abdallah, W.M.; Clarke, M.F.; Wicha, M.S. Stem cells in normal breast development and breast cancer. Cell Prolif 2003, 36 Suppl 1, 59-72. [CrossRef]

- Batlle, E.; Clevers, H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nature medicine 2017, 23, 1124-1134. [CrossRef]

- Reya, T.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F.; Weissman, I.L. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 2001, 414, 105-111. [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Tian, W.; Ning, J.; Xiao, G.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhai, Z.; Tanzhu, G.; Yang, J.; Zhou, R. Cancer stem cells: advances in knowledge and implications for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 170. [CrossRef]

- Visvader, J.E.; Lindeman, G.J. Cancer stem cells: current status and evolving complexities. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10, 717-728. [CrossRef]

- Cody, N.A.; Ouellet, V.; Manderson, E.N.; Quinn, M.C.; Filali-Mouhim, A.; Tellis, P.; Zietarska, M.; Provencher, D.M.; Mes-Masson, A.M.; Chevrette, M., et al. Transfer of chromosome 3 fragments suppresses tumorigenicity of an ovarian cancer cell line monoallelic for chromosome 3p. Oncogene 2007, 26, 618-632. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.L.; Tian, T.; Nan, K.J.; Zhao, N.; Guo, Y.H.; Cui, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.G. Survival advantages of multicellular spheroids vs. monolayers of HepG2 cells in vitro. Oncol Rep 2008, 20, 1465-1471.

- Marotta, L.L.C.; Polyak, K. Cancer stem cells: a model in the making. Current opinion in genetics & development 2009, 19, 44-50. [CrossRef]

- Oskarsson, T.; Batlle, E.; Massague, J. Metastatic stem cells: sources, niches, and vital pathways. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 306-321. [CrossRef]

- Bielecka, Z.F.; Maliszewska-Olejniczak, K.; Safir, I.J.; Szczylik, C.; Czarnecka, A.M. Three-dimensional cell culture model utilization in cancer stem cell research. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2017, 92, 1505-1520. [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.; Hu, Z.; Lu, L.; Lu, H.; Xu, X. Three-dimensional cell culture: A powerful tool in tumor research and drug discovery. Oncology letters 2017, 14, 6999-7010. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, M.; Brightman, A.O.; Lawrence, J.; Werderitsh, D.; Morré, D.M.; Morré, D.J. Stimulation of NADH oxidase activity from rat liver plasma membranes by growth factors and hormones is decreased or absent with hepatoma plasma membranes. Biochem J 1992, 284 ( Pt 3), 625-628. [CrossRef]

- Chueh, P.J. Cell membrane redox systems and transformation. Antioxid Redox Signal 2000, 2, 177-187. [CrossRef]

- Chueh, P.J.; Kim, C.; Cho, N.; Morré, D.M.; Morré, D.J. Molecular cloning and characterization of a tumor-associated, growth-related, and time-keeping hydroquinone (NADH) oxidase (tNOX) of the HeLa cell surface. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 3732-3741. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Islam, A.; Yuan, T.M.; Chen, S.W.; Liu, P.F.; Chueh, P.J. Regulation of tNOX expression through the ROS-p53-POU3F2 axis contributes to cellular responses against oxaliplatin in human colon cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2018, 37, 161. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.C.; Yang, J.J.; Shao, K.N.; Chueh, P.J. RNA interference targeting tNOX attenuates cell migration via a mechanism that involves membrane association of Rac. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008, 365, 672-677. [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.C.; Hsieh, P.F.; Hsieh, M.K.; Zeng, Z.M.; Cheng, H.L.; Liao, J.W.; Chueh, P.J. Capsaicin-mediated tNOX (ENOX2) up-regulation enhances cell proliferation and migration in vitro and in vivo. J Agric Food Chem 2012, 60, 2758-2765. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Cheng, H.L.; Chen, H.Y.; Jhuang, F.H.; Chueh, P.J. Capsaicin Inhibits Multiple Bladder Cancer Cell Phenotypes by Inhibiting Tumor-Associated NADH Oxidase (tNOX) and Sirtuin1 (SIRT1). Molecules 2016, 21. [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Hsieh, P.F.; Liu, P.F.; Chou, J.C.; Liao, J.W.; Hsieh, M.K.; Chueh, P.J. Capsaicin exerts therapeutic effects by targeting tNOX-SIRT1 axis and augmenting ROS-dependent autophagy in melanoma cancer cells. Am J Cancer Res 2021, 11, 4199-4219.

- Xu, C.Y.; Wang, L.; Fozouni, P.; Evjen, G.; Chandra, V.; Jiang, J.; Lu, C.C.; Nicastri, M.; Bretz, C.; Winkler, J.D., et al. SIRT1 is downregulated by autophagy in senescence and ageing. Nature Cell Biology 2020, 22, 1170-+. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.J.; Defossez, P.A.; Guarente, L. Requirement of NAD and SIR2 for life-span extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 2000, 289, 2126-2128. [CrossRef]

- Leng, S.; Huang, W.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Feng, D.; Liu, W.; Gao, T.; Ren, Y.; Huo, M.; Zhang, J., et al. SIRT1 coordinates with the CRL4B complex to regulate pancreatic cancer stem cells to promote tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ 2021, 28, 3329-3343. [CrossRef]

- Michan, S.; Sinclair, D. Sirtuins in mammals: insights into their biological function. Biochemical Journal 2007, 404, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Cao, J.; Zhang, L.; Hu, X.; Wang, J. Role of SIRT1 and AMPK in mesenchymal stem cells differentiation. Ageing Res Rev 2014, 13, 55-64. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.M.; Liu, C.G.; Zhang, Q.Z.; Shen, J.J.; Zhang, H.; Shan, J.J.; Duan, G.J.; Guo, D.Y.; Chen, X.J.; Cheng, J.M., et al. SIRT1-mediated transcriptional regulation of SOX2 is important for self-renewal of liver cancer stem cells. Hepatology 2016, 64, 814-827. [CrossRef]

- de Castro, L.R.; de Oliveira, L.D.; Milan, T.M.; Eskenazi, A.P.E.; Bighetti-Trevisan, R.L.; de Almeida, O.G.G.; Amorim, M.L.M.; Squarize, C.H.; Castilho, R.M.; de Almeida, L.O. Up-regulation of TNF-alpha/NFkB/SIRT1 axis drives aggressiveness and cancer stem cells accumulation in chemoresistant oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Cell Physiol 2024, 239, e31164. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, G.; Liu, Y.; Ma, M.; Song, K.; Li, H.; Zhu, D.; Tang, X.; Kong, J.; Yuan, X. Targeting histone deacetylase SIRT1 selectively eradicates EGFR TKI-resistant cancer stem cells via regulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in lung adenocarcinoma. Neoplasia 2020, 22, 33-46. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Huang, S.; Liu, S.C.; Chueh, P.J. Effect of polyclonal antisera to recombinant tNOX protein on the growth of transformed cells. Biofactors 2006, 28, 119-133. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Chen, H.Y.; Su, L.J.; Chueh, P.J. Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) Deacetylase Activity and NAD(+)/NADH Ratio Are Imperative for Capsaicin-Mediated Programmed Cell Death. J Agric Food Chem 2015, 63, 7361-7370. [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Chang, Y.C.; Chen, X.C.; Weng, C.W.; Chen, C.Y.; Wang, C.W.; Chen, M.K.; Tikhomirov, A.S.; Shchekotikhin, A.E.; Chueh, P.J. Water-soluble 4-(dimethylaminomethyl)heliomycin exerts greater antitumor effects than parental heliomycin by targeting the tNOX-SIRT1 axis and apoptosis in oral cancer cells. Elife 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Luján-Méndez, F.; Roldán-Padrón, O.; Castro-Ruíz, J.E.; López-Martínez, J.; García-Gasca, T. Capsaicinoids and Their Effects on Cancer: The “Double-Edged Sword” Postulate from the Molecular Scale. Cells 2023, 12, doi:ARTN 2573 10.3390/cells12212573.

- Chen, H.Y.; Cheng, H.L.; Lee, Y.H.; Yuan, T.M.; Chen, S.W.; Lin, Y.Y.; Chueh, P.J. Tumor-associated NADH oxidase (tNOX)-NAD+-sirtuin 1 axis contributes to oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis of gastric cancer cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 15338-15348. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Islam, A.; Su, C.J.; Tikhomirov, A.S.; Shchekotikhin, A.E.; Chuang, S.M.; Chueh, P.J.; Chen, Y.L. Engagement with tNOX (ENOX2) to Inhibit SIRT1 and Activate p53-Dependent and -Independent Apoptotic Pathways by Novel 4,11-Diaminoanthra[2,3-b]furan-5,10-diones in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Oh, S.Y.; Do, S.I.; Lee, H.J.; Kang, H.J.; Rho, Y.S.; Bae, W.J.; Lim, Y.C. SOX2 regulates self-renewal and tumorigenicity of stem-like cells of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2014, 111, 2122-2130. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, H.; Ye, J.; Song, X.; Yang, J., et al. The Hippo effector TAZ promotes cancer stemness by transcriptional activation of SOX2 in head neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 603. [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, B.; Weston, N.; Kim, C.; Morré, D.M.; Morré, D.J. Cancer Site-Specific Isoforms of ENOX2 (tNOX), A Cancer-Specific Cell Surface Oxidase. Clinical Proteomics 2009, 5, 46-51. [CrossRef]

- Chueh, P.J.; Wu, L.Y.; Morre, D.M.; Morre, D.J. tNOX is both necessary and sufficient as a cellular target for the anticancer actions of capsaicin and the green tea catechin (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Biofactors 2004, 20, 235-249.

- Zeng, Z.M.; Chuang, S.M.; Chang, T.C.; Hong, C.W.; Chou, J.C.; Yang, J.J.; Chueh, P.J. Phosphorylation of serine-504 of tNOX (ENOX2) modulates cell proliferation and migration in cancer cells. Experimental cell research 2012, 318, 1759-1766. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.C.; Lin, Y.H.; Zeng, Z.M.; Shao, K.N.; Chueh, P.J. Chemotherapeutic agents enhance cell migration and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition through transient up-regulation of tNOX (ENOX2) protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1820, 1744-1752. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.F.; Islam, A.; Liu, P.F.; Zhan, J.H.; Chueh, P.J. Capsaicin acts through tNOX (ENOX2) to induce autophagic apoptosis in p53-mutated HSC-3 cells but autophagy in p53-functional SAS oral cancer cells. Am J Cancer Res 2020, 10, 3230-3247.

- Islam, A.; Su, A.J.; Zeng, Z.M.; Chueh, P.J.; Lin, M.H. Capsaicin Targets tNOX (ENOX2) to Inhibit G1 Cyclin/CDK Complex, as Assessed by the Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA). Cells 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.M.; Chuang, S.M.; Su, Y.C.; Li, Y.H.; Chueh, P.J. Down-regulation of tumor-associated NADH oxidase, tNOX (ENOX2), enhances capsaicin-induced inhibition of gastric cancer cell growth. Cell Biochem Biophys 2011, 61, 355-366. [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, Y.; Yasui, H.; Nozaki, M.; Nakajima, M. Molecularly-targeted therapy for the oral cancer stem cells. Jpn Dent Sci Rev 2018, 54, 88-103. [CrossRef]

- Mangani, S.; Kremmydas, S.; Karamanos, N.K. Mimicking the Complexity of Solid Tumors: How Spheroids Could Advance Cancer Preclinical Transformative Approaches. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y. Capsaicin on stem cell proliferation and fate determination - a novel perspective. Pharmacol Res 2021, 167, 105566. [CrossRef]

- Bethel, M.; Chitteti, B.R.; Srour, E.F.; Kacena, M.A. The changing balance between osteoblastogenesis and adipogenesis in aging and its impact on hematopoiesis. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2013, 11, 99-106. [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.E.; Sivanandan, R.; Kaczorowski, A.; Wolf, G.T.; Kaplan, M.J.; Dalerba, P.; Weissman, I.L.; Clarke, M.F.; Ailles, L.E. Identification of a subpopulation of cells with cancer stem cell properties in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 973-978. [CrossRef]

- Phi, L.T.H.; Sari, I.N.; Yang, Y.G.; Lee, S.H.; Jun, N.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, Y.K.; Kwon, H.Y. Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) in Drug Resistance and their Therapeutic Implications in Cancer Treatment. Stem Cells Int 2018, 2018, 5416923. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663-676. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, A.; Faiola, F.; Wang, J. Concise review: pursuing self-renewal and pluripotency with the stem cell factor Nanog. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 1227-1236. [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Jin, Y. Role of Oct4 in maintaining and regaining stem cell pluripotency. Stem Cell Res Ther 2010, 1, 39. [CrossRef]

- Heng, J.C.; Orlov, Y.L.; Ng, H.H. Transcription factors for the modulation of pluripotency and reprogramming. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2010, 75, 237-244. [CrossRef]

- Han, M.K.; Song, E.K.; Guo, Y.; Ou, X.; Mantel, C.; Broxmeyer, H.E. SIRT1 regulates apoptosis and Nanog expression in mouse embryonic stem cells by controlling p53 subcellular localization. Cell Stem Cell 2008, 2, 241-251. [CrossRef]

- Prozorovski, T.; Schulze-Topphoff, U.; Glumm, R.; Baumgart, J.; Schroter, F.; Ninnemann, O.; Siegert, E.; Bendix, I.; Brustle, O.; Nitsch, R., et al. Sirt1 contributes critically to the redox-dependent fate of neural progenitors. Nat Cell Biol 2008, 10, 385-394. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.S.; Choi, Y.; Jang, Y.; Lee, M.; Choi, W.J.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.W. SIRT1 directly regulates SOX2 to maintain self-renewal and multipotency in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 3219-3231. [CrossRef]

- Tikhomirov, A.S.; Shchekotikhin, A.E.; Lee, Y.H.; Chen, Y.A.; Yeh, C.A.; Tatarskiy, V.V., Jr.; Dezhenkova, L.G.; Glazunova, V.A.; Balzarini, J.; Shtil, A.A., et al. Synthesis and Characterization of 4,11-Diaminoanthra[2,3-b]furan-5,10-diones: Tumor Cell Apoptosis through tNOX-Modulated NAD(+)/NADH Ratio and SIRT1. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2015, 58, 9522-9534. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.H.; Islam, A.; Liu, Y.H.; Weng, C.W.; Zhan, J.H.; Liang, R.H.; Tikhomirov, A.S.; Shchekotikhin, A.E.; Chueh, P.J. Antibiotic heliomycin and its water-soluble 4-aminomethylated derivative provoke cell death in T24 bladder cancer cells by targeting sirtuin 1 (SIRT1). Am J Cancer Res 2022, 12, 1042-1055.

- Chen, Z.; Forman, L.W.; Williams, R.M.; Faller, D.V. Protein kinase C-delta inactivation inhibits the proliferation and survival of cancer stem cells in culture and in vivo. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 90. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Oikawa, T.; Kizawa, R.; Motohashi, S.; Yoshida, S.; Kumamoto, T.; Saeki, C.; Nakagawa, C.; Shimoyama, Y.; Aoki, K., et al. Unconventional Secretion of PKCdelta Exerts Tumorigenic Function via Stimulation of ERK1/2 Signaling in Liver Cancer. Cancer Res 2021, 81, 414-425. [CrossRef]

- Morre, D.J.; Chueh, P.J.; Morre, D.M. Capsaicin inhibits preferentially the NADH oxidase and growth of transformed cells in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995, 92, 1831-1835. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.D.; Kim, J.M.; Pyo, J.O.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, B.S.; Yu, R.; Han, I.S. Capsaicin can alter the expression of tumor forming-related genes which might be followed by induction of apoptosis of a Korean stomach cancer cell line, SNU-1. Cancer Lett 1997, 120, 235-241. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.C.; Kim, J.H.; Prasad, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Regulation of survival, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis of tumor cells through modulation of inflammatory pathways by nutraceuticals. Cancer Metast Rev 2010, 29, 405-434. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.C.; Lee, H.; Choi, B.Y. An updated review on molecular mechanisms underlying the anticancer effects of capsaicin. Food Sci Biotechnol 2017, 26, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Li, M.; Wang, X. Capsaicin induces apoptosis and autophagy in human melanoma cells. Oncology letters 2019, 17, 4827-4834. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.P.; Wang, D.A.; Huang, J.Y.; Hu, Y.M.; Xu, Y.F. Application of capsaicin as a potential new therapeutic drug in human cancers. J Clin Pharm Ther 2020, 45, 16-28. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.Q.; Li, H.X.; Hou, X.J.; Huang, M.Y.; Zhu, Z.M.; Wei, L.X.; Tang, C.X. Capsaicin suppresses hepatocarcinogenesis by inhibiting the stemness of hepatic progenitor cells via SIRT1/SOX2 signaling pathway. Cancer Med 2022, 11, 4283-4296. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Y.; Huang, H.H.; Li, Q.C.; Zhan, F.B.; Wang, L.B.; He, T.; Yang, C.H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Quan, Z.X. Capsaicin Reduces Cancer Stemness and Inhibits Metastasis by Downregulating SOX2 and EZH2 in Osteosarcoma. Am J Chin Med 2023, 51, 1041-1066. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Yu, X.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, J.; Yang, X.; Shi, H. Capsaicin suppressed activity of prostate cancer stem cells by inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Phytother Res 2020, 34, 817-824. [CrossRef]

- Lo Iacono, M.; Gaggianesi, M.; Bianca, P.; Brancato, O.R.; Muratore, G.; Modica, C.; Roozafzay, N.; Shams, K.; Colarossi, L.; Colarossi, C., et al. Destroying the Shield of Cancer Stem Cells: Natural Compounds as Promising Players in Cancer Therapy. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Expression of ENOX2 in head and neck cancer

. (A, B). Differential expression of ENOX2 in HNSCC and adjacent normal tissues, analyzed from TCGA (A) and CPTAC (B) datasets using UALCAN (

https://ualcan.path.uab.edu). ENOX2 transcript levels were significantly higher in TCGA tumor samples compared with normal tissues (***

p < 0.001). (C). Analysis of data from the Human Protein Atlas (

https://www.proteinatlas.org) indicated that ENOX2 expression is higher in head and neck cancer cell lines (e.g., HSC-3). (D) Heatmap analysis of data from the Human Protein Atlas dataset demonstrated elevated ENOX2 mRNA expression

across multiple malignancies.

Figure 1.

Expression of ENOX2 in head and neck cancer

. (A, B). Differential expression of ENOX2 in HNSCC and adjacent normal tissues, analyzed from TCGA (A) and CPTAC (B) datasets using UALCAN (

https://ualcan.path.uab.edu). ENOX2 transcript levels were significantly higher in TCGA tumor samples compared with normal tissues (***

p < 0.001). (C). Analysis of data from the Human Protein Atlas (

https://www.proteinatlas.org) indicated that ENOX2 expression is higher in head and neck cancer cell lines (e.g., HSC-3). (D) Heatmap analysis of data from the Human Protein Atlas dataset demonstrated elevated ENOX2 mRNA expression

across multiple malignancies.

Figure 2.

Expression and clinical relevance of ENOX2, SIRT1, and SOX2 in oral cancer patient datasets. (A) TCGA analysis revealed significantly elevated SIRT1 and SOX2 transcript levels in HNSCC tumor tissues compared to normal tissues across all grades. *

p < 0.05, ***

p < 0.001. (B) Western blot analysis of paired patient specimens (representative case, patient 2) showed higher protein expression of ENOX2, SIRT1, and SOX2 in oral cancer tissues relative to adjacent non-tumor tissues. Tissue lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting, with β-actin used as a loading control. (C) Pearson correlation analysis demonstrated positive correlations between ENOX2 and SIRT1, as well as between ENOX2 and SOX2. (D) Kaplan–Meier plotter analysis (

https://www.kmplot.com/) indicated that high expression levels of ENOX2 (all stages, female group), SIRT1 (stage III + IV, female group), and SOX2 (all stages, female group) were significantly associated with poor overall survival in female patients with head and neck cancer.

Figure 2.

Expression and clinical relevance of ENOX2, SIRT1, and SOX2 in oral cancer patient datasets. (A) TCGA analysis revealed significantly elevated SIRT1 and SOX2 transcript levels in HNSCC tumor tissues compared to normal tissues across all grades. *

p < 0.05, ***

p < 0.001. (B) Western blot analysis of paired patient specimens (representative case, patient 2) showed higher protein expression of ENOX2, SIRT1, and SOX2 in oral cancer tissues relative to adjacent non-tumor tissues. Tissue lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting, with β-actin used as a loading control. (C) Pearson correlation analysis demonstrated positive correlations between ENOX2 and SIRT1, as well as between ENOX2 and SOX2. (D) Kaplan–Meier plotter analysis (

https://www.kmplot.com/) indicated that high expression levels of ENOX2 (all stages, female group), SIRT1 (stage III + IV, female group), and SOX2 (all stages, female group) were significantly associated with poor overall survival in female patients with head and neck cancer.

Figure 3.

ENOX2 prompts stem-like properties and proliferation in oral cancer cells. (A) Interaction network of ENOX2 and associated proteins generated using the Integrated Interaction Database (IID). (B) Co-immunoprecipitation of GST-ENOX2-overexpressing cell lysates with non-immune IgG or antibodies against GST and SOX2, followed by Western blotting with anti-GST or anti-SOX2 antibodies. Whole-cell lysates were also immunoblotted with anti-ENOX2 and anti-SOX2 antibodies; β-actin served as a loading control. Representative images are shown. (C, D) Western blot analysis of stemness markers in cells transfected with GST or GST-ENOX2 for 72 h (C), or with si-control (scramble RNAi) or si-ENOX2 for 48 h (D). β-actin was used as the loading control. (E) Real-time monitoring of proliferation in SAS and HSC-3 cells transfected with GST, GST-ENOX2, si-control, or si-ENOX2. After overnight attachment, cells were seeded onto E-plates, and proliferation was continuously measured using the xCELLigence system. Cell index values are presented. (F) Pearson correlation analysis of ENOX2 with XIAP and MRPL41 in TCGA tumor tissues using UALCAN (

https://ualcan.path.uab.edu).

Figure 3.

ENOX2 prompts stem-like properties and proliferation in oral cancer cells. (A) Interaction network of ENOX2 and associated proteins generated using the Integrated Interaction Database (IID). (B) Co-immunoprecipitation of GST-ENOX2-overexpressing cell lysates with non-immune IgG or antibodies against GST and SOX2, followed by Western blotting with anti-GST or anti-SOX2 antibodies. Whole-cell lysates were also immunoblotted with anti-ENOX2 and anti-SOX2 antibodies; β-actin served as a loading control. Representative images are shown. (C, D) Western blot analysis of stemness markers in cells transfected with GST or GST-ENOX2 for 72 h (C), or with si-control (scramble RNAi) or si-ENOX2 for 48 h (D). β-actin was used as the loading control. (E) Real-time monitoring of proliferation in SAS and HSC-3 cells transfected with GST, GST-ENOX2, si-control, or si-ENOX2. After overnight attachment, cells were seeded onto E-plates, and proliferation was continuously measured using the xCELLigence system. Cell index values are presented. (F) Pearson correlation analysis of ENOX2 with XIAP and MRPL41 in TCGA tumor tissues using UALCAN (

https://ualcan.path.uab.edu).

Figure 4.

Sphere formation and stem-like properties of SAS and HSC-3 oral cancer cells. (A) Sphere-forming abilities of SAS and HSC-3 cells. Various cell densities of SAS cells (0.5 × 103, 1 × 103, 2 × 103, 3 × 103, 4 × 103, 5 × 103, and 1 × 104) and HSC-3 cells (1 × 104) were seeded into 96-well ultra-low attachment plates and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C. Representative images obtained at different time points are shown. (B) Western blot analysis of spheroid cells harvested at day 7, showing expression of ENOX2, SIRT1, and stemness-associated markers. β-Actin served as the loading control. (C) Comparison of the intracellular NAD⁺/NADH ratios between adherent and spheroid SAS cells, as measured using an NADH/NAD quantification kit. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (**p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Sphere formation and stem-like properties of SAS and HSC-3 oral cancer cells. (A) Sphere-forming abilities of SAS and HSC-3 cells. Various cell densities of SAS cells (0.5 × 103, 1 × 103, 2 × 103, 3 × 103, 4 × 103, 5 × 103, and 1 × 104) and HSC-3 cells (1 × 104) were seeded into 96-well ultra-low attachment plates and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C. Representative images obtained at different time points are shown. (B) Western blot analysis of spheroid cells harvested at day 7, showing expression of ENOX2, SIRT1, and stemness-associated markers. β-Actin served as the loading control. (C) Comparison of the intracellular NAD⁺/NADH ratios between adherent and spheroid SAS cells, as measured using an NADH/NAD quantification kit. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (**p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Expression of CD44 and CD138 in SAS and HSC-3 spheroid cells. (A, B) SAS and HSC-3 cells were cultured in poly-HEMA-coated 10-cm dishes under non-adherent conditions. After 7 days, spheroids were dissociated into single cells stained with FITC-conjugated antibodies against CD44 and CD138, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of positive cells were determined. Both markers were significantly increased in spheroid cultures compared with adherent controls. Data are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments (***p <0.001 vs. control).

Figure 5.

Expression of CD44 and CD138 in SAS and HSC-3 spheroid cells. (A, B) SAS and HSC-3 cells were cultured in poly-HEMA-coated 10-cm dishes under non-adherent conditions. After 7 days, spheroids were dissociated into single cells stained with FITC-conjugated antibodies against CD44 and CD138, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of positive cells were determined. Both markers were significantly increased in spheroid cultures compared with adherent controls. Data are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments (***p <0.001 vs. control).

Figure 6.

Role of ENOX2 in regulating stemness of oral cancer cells. (A) SAS and HSC-3 cells were transfected with GST or GST-ENOX2 for 72 h, seeded onto poly-HEMA-coated 6-well plates, and cultured under non-adherent conditions. After 7 days, spheroids were harvested, and protein levels of stemness-associated markers were analyzed by Western blotting. (B) SAS and HSC-3 cells were transfected with si-control or si-ENOX2 for 48 h, seeded onto poly-HEMA-coated 6-well plates, and cultured under non-adherent conditions. After 7 days, spheroids were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as the loading control.

Figure 6.

Role of ENOX2 in regulating stemness of oral cancer cells. (A) SAS and HSC-3 cells were transfected with GST or GST-ENOX2 for 72 h, seeded onto poly-HEMA-coated 6-well plates, and cultured under non-adherent conditions. After 7 days, spheroids were harvested, and protein levels of stemness-associated markers were analyzed by Western blotting. (B) SAS and HSC-3 cells were transfected with si-control or si-ENOX2 for 48 h, seeded onto poly-HEMA-coated 6-well plates, and cultured under non-adherent conditions. After 7 days, spheroids were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as the loading control.

Figure 7.

ENOX2 promotes the growth of oral cancer xenografts in ASID mice. (A) SAS cells were transiently transfected with GST or GST-ENOX2. After 72 h, cells were cultured in poly-HEMA–coated plates to form spheres. Following 7 days of sphere formation, spheroids were dissociated into single cells and subcutaneously inoculated into ASID mice at doses of 1 × 10⁶, 2×10⁴, or 1 × 10⁴. Tumor growth was assessed by measuring tumor volume. Representative tumor morphology and quantitative analyses are shown. Statistically significant differences between the GST and GST-ENOX2 groups were determined by one-way ANOVA with LSD post-hoc test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (B) Tumor tissues from both groups were homogenized and analyzed by Western blotting for stemness-associated markers. (C) Sphere-forming cells transfected with si-control or si-ENOX2 (1 × 10⁶) were subcutaneously inoculated into ASID mice. Tumor growth, measured by assessment of tumor volume, was significantly reduced in the si-ENOX2 group compared with controls (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Figure 7.

ENOX2 promotes the growth of oral cancer xenografts in ASID mice. (A) SAS cells were transiently transfected with GST or GST-ENOX2. After 72 h, cells were cultured in poly-HEMA–coated plates to form spheres. Following 7 days of sphere formation, spheroids were dissociated into single cells and subcutaneously inoculated into ASID mice at doses of 1 × 10⁶, 2×10⁴, or 1 × 10⁴. Tumor growth was assessed by measuring tumor volume. Representative tumor morphology and quantitative analyses are shown. Statistically significant differences between the GST and GST-ENOX2 groups were determined by one-way ANOVA with LSD post-hoc test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (B) Tumor tissues from both groups were homogenized and analyzed by Western blotting for stemness-associated markers. (C) Sphere-forming cells transfected with si-control or si-ENOX2 (1 × 10⁶) were subcutaneously inoculated into ASID mice. Tumor growth, measured by assessment of tumor volume, was significantly reduced in the si-ENOX2 group compared with controls (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Figure 8.

Capsaicin suppresses sphere formation and stemness marker expression in SAS cells. (A) SAS cells were cultured in ultra-low attachment plates for 48 h, and then treated with or without capsaicin for 5 days. Representative images of spheres at day 7 are shown. (B) Western blot analysis of SAS spheroids treated with or without capsaicin. Protein levels of ENOX2, SIRT1, and stemness-associated markers (SOX2, Nanog, Oct4) were assessed. β-Actin served as a loading control.

Figure 8.

Capsaicin suppresses sphere formation and stemness marker expression in SAS cells. (A) SAS cells were cultured in ultra-low attachment plates for 48 h, and then treated with or without capsaicin for 5 days. Representative images of spheres at day 7 are shown. (B) Western blot analysis of SAS spheroids treated with or without capsaicin. Protein levels of ENOX2, SIRT1, and stemness-associated markers (SOX2, Nanog, Oct4) were assessed. β-Actin served as a loading control.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).