1. Introduction

1.1. How to Define Hard-to-Heal Wound in Children

Hard-to-heal wounds are commonly defined as those that, despite appropriate clinical management, fail to reduce in area by more than 30% within four weeks and do not achieve complete closure within 12 weeks.(1,2) These thresholds, however, are primarily derived from the adult population and are not fully standardized for pediatrics.(3–5) In adults, different etiologies are associated with variable parameters, such as: <50% reduction in diabetic foot lesions; <40% in venous lesions of the lower extremities; 20-40% in pressure ulcers. These criteria cannot be directly applied to children. In pediatric patients, particularly neonates and infants with immature skin and a developing immune system, the healing process is often different, and shared definitions of Hard-to-Heal wounds are still lacking.(5-8) This lack of unambiguous definitions underscores the importance of adopting an interdisciplinary and interprofessional approach (IIPT) to accurately identify and manage complex wounds.(1) Furthermore, growing evidence indicates that impaired or stalled healing in children is particularly associated with the presence of multidrug-resistant polymicrobial biofilms, responsible for 80% of chronic wounds. However, host factors, such as prematurity, malnutrition, and chronic diseases, also contribute to wound chronicity.(9)

The lack of specific pediatric criteria for defining Hard-to-Heal wounds highlights the need for personalized strategies and collaborative care models.

1.2. The Fragile, Immature Skin in Children

Neonatal and infant skin, although structurally similar to adult skin, is markedly immature, with a thinner stratum corneum and reduced dermo-epidermal cohesion, factors that increase susceptibility to trauma and infection. The epidermis and stratum corneum are thinner, with reduced cohesion at the dermal-epidermal junction, making the skin more susceptible to trauma and transepidermal water loss (TEWL). The dermis contains less organized collagen fibers and is characterized by reduced elastin synthesis, both factors that compromise resistance to friction and slippage. (10)

Wound repair in pediatric age proceeds according to the physiological process that includes the inflammatory, proliferative, and remodeling phases, but obviously with unique characteristics: the inflammatory response is attenuated, while fibroblast activity and collagen deposition can occur more rapidly.(11)

The immaturity of the skin barrier increases the risk of infections and fluid-electrolyte imbalance. Additional host-related factors such as nutritional deficiencies (proteins, vitamins A, C, D, iron, zinc, selenium), chronic diseases, and prematurity may further compromise the already fragile pediatric healing process.(12)

These unique structural and functional characteristics make children's skin more susceptible to injury and healing complications, underscoring the need for informed and specialized approaches.

Advanced dressings that maintain a balanced moist environment and support the extracellular matrix (ECM), such as Hyaluronic Acid (HA)-based formulations, can help preserve barrier function, promote cell proliferation, and reduce inflammation, thus optimizing the healing process in this fragile population.(10)

1.3. The Role and Properties of HA in Pediatric Skin

HA, the main glycosaminoglycan in the ECM, is a linear, unsulfured, and highly hydrophilic polysaccharide chain capable of binding large amounts of water due to its structure rich in carboxyl and acetylamine groups (hygroscopic properties). This characteristic gives the skin remarkable turgidity and elasticity and promotes the diffusion of nutrients, growth factors, and immune cells.

Under physiological conditions, HA is completely dissociated, negatively charged, and participates in numerous key biological processes, including cell proliferation and differentiation, tissue remodeling, and modulation of the inflammatory response.(13,14)

Unlike other glycosaminoglycans, HA is unsulfured and is synthesized directly at the plasma membrane by three isoforms of hyaluronan synthase (HAS1-3), which determine its different molecular weights. Its degradation is regulated by hyaluronidase isoforms, with a particularly rapid turnover in childhood, related to higher metabolic rates and skin growth and maturation processes. Children's skin, despite representing approximately 15% of body weight, contains more than half of the total HA present in the body: while an adult has an average of 10-15 g of HA, a 1-year-old child has approximately 2 g, a 5-year-old approximately 4 g, and a 10-year-old up to 6 g.(15,16)

The cutaneous distribution of HA varies between the epidermis and the dermis. In the dermis, HA, together with proteoglycans and collagen, contributes to maintaining hydration and biomechanical properties, forming a three-dimensional scaffold with marked viscoelasticity. In the epidermis, present mainly between the basal and spiny cells, HA is crucial for the organization of the stratum corneum and the formation of the lamellar structures that ensure the integrity of the skin barrier. Furthermore, by binding to specific receptors (including CD44, RHAMM, TLRs, and HARE), HA participates in cell signaling processes and exerts an antioxidant role, thus limiting damage from reactive oxygen species.(14–16)

These properties make HA an essential component in pediatric skin physiology, suggesting a potential therapeutic role in Hard-to-Heal wounds, where reduced skin maturity and increased tissue turnover can hinder spontaneous healing.(14)

1.4. Principal Aim of the Study

In light of these considerations, it is essential to investigate and further develop therapeutic strategies that combine essential HA and AA to promote healing in pediatric hard-to-heal wounds. This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility, clinical outcomes, and tolerability of an injectable HA+AA complex in a consecutive series of pediatric patients with chronic and persistent wounds.

2. Materials and Methods

This descriptive observational study, of the prospective case series type, was conducted at an Italian center. All consecutive pediatric patients were screened for eligibility and enrolled if they met the predefined inclusion criteria. The study was conducted in Ambulatory Wound Health Care Setting during from November 2022 until August 2025, including the follow-up time (

Table 1).

Fifteen pediatric patients aged 4 to 16 years came to our attention with severe and painful lesions of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. All patients presented lesions attributable to ulcers of various types and staged according to the EPUAP 2025 guidelines for Pressure Ulcers (PUs)(17). They had numerous comorbidities, but the common feature was that they represented both congenital and acquired chronicity, and in many cases, psychomotor retardation. All patients were treated for delayed wound healing, which presented various etiologies and pathogenesis: in particular, these hard-to-heal lesions were diagnosed with delayed healing in all cases beyond 6 months and up to 12 months from the onset of the lesion itself. All lesions were primarily treated elsewhere and came to our attention due to delayed healing after following different protocols (from one to four different treatment schemes), severe stress among parents and caregivers, and pain that was sometimes mystified by comorbidities and classified according to age based on the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability scale (FLACC)(18), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)(19), and Échelle de Douleur et d’Inconfort de l’Enfant (INRS).(20)

All patients received a standardized wound hygiene protocol, which included gentle cleansing of the wound bed with non-ionic, no-rinse solutions, protection of the periwound skin, antisepsis with 2% chlorhexidine for the surrounding skin and polyhexanide (PHMB) solutions for the wound bed, and application of appropriate advanced wound dressings to maintain homeostasis of the wound environment.

In addition to injectable treatment with HA+AA, specific co-interventions were permitted according to predefined criteria: 1) osmotic/enzymatic autolytic debridement with HA+AA gel or cream performed in the presence of eschar, slough, or non-viable tissue; 2) hydrophobic dressings with Dialkyl Carbamoyl Chloride (DACC) technology were used when clinical signs of critical superficial colonization were identified according to IWII criteria (stages 1-2, Non-healing, Exudate, Red friable tissue, Debris, Smell – NERDS – and Size, Temperature, Os/bone, New breakdown, Exudate, Erythema/Edema, Smell – STONEES);(21) 3) Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) was used in cases of extensive wound loss.

All patients were informed of the type of treatment to be undertaken and, where possible, provided written or verbal consent from their parents/foster parents and caregivers.

The therapy consisted of a unique blend of hyaluronic acid and 6 amino acids (HA+6AA) (Vulnamin Inj®, Professional Dietetics, Milan, Italy), administered as an injectable preparation at the epidermis-dermis junction and deep subcutaneous tissue in all cases.

2.1. Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for HA+6AA Infiltration

Vulnamin® Inj is a sterile injectable CE Medical Device class III, containing the HA+6AA patented formula, a composition of low molecular-weight sodium hyaluronate (10 mg/mL; 150–280 kDa) plus a six-amino-acid cluster (L-leucine, glycine, L-valine, L-alanine, L-proline, L-lysine) formulated in proprietary, patent-protected ratios (individual percentages undisclosed).

For each session, a total volume of 2-4 mL was infiltrated, divided into 4-8 depots per wound, with injections spaced approximately 0.5-1 cm apart along the wound edges and the dermo-epidermal junction; in cases with deeper tissue loss, additional depots were delivered into the subcutaneous plane. Infiltration was performed using sterile 21-23 G needles under magnification to avoid vascular injury. The procedure followed a clockwise or counterclockwise mapping of the wound perimeter, ensuring complete coverage of poorly granulating or undermined areas.

Systemic or local anesthesia was not routinely required, as injections were generally well tolerated and did not cause burning sensations. All children received oral paracetamol (15 mg/kg) 30 minutes before the procedure. In selected cases, based on age, comorbidities, or behavioral issues (autism spectrum disorder, marked anxiety), topical lidocaine spray or cream was applied at the discretion of the team. Deep sedation or intranasal analgesia was considered only in exceptional situations. During each procedure, a parent or caregiver, a physician, and a nurse were always present, and no treatment sessions had to be interrupted due to pain or distress.

Adverse events were actively monitored at each session. Predefined safety endpoints included: procedural pain (assessed with age-appropriate scales: FLACC, VAS, INRS), local bleeding, injection-site infection, delayed healing, nodule formation, and systemic or local hypersensitivity reactions. No major adverse events were observed during the study period.

2.2. Outcomes

Study endpoints were defined as shown in

Table 2. The primary endpoint was time to complete healing, defined as 100% epithelial coverage, no exudate, and confirmed by two consecutive assessments performed at least 7-14 days apart. Secondary endpoints included quantitative measures of wound progression, clinical parameters of infection and exudate, analgesic requirements, and tolerability indicators.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All collected data were analyzed descriptively, considering the limited sample size and the observational design of the study. Continuous variables, such as age, wound duration, number of sessions, time to complete re-epithelialization, and follow-up length, were summarized as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical variables, including sex, wound etiology, wound location, stage, comorbidities, and the use of co-interventions such as NPWT or DACC dressings, were reported as absolute numbers and percentages.

The primary outcome, defined as time to complete re-epithelialization, was described by calculating median and IQR values, and healing trajectories were represented using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, with censoring of the patient who did not achieve healing during follow-up.

Secondary outcomes were analyzed descriptively. Pain was evaluated with age-appropriate validated scales (FLACC, INRS, and VAS), and changes over time were qualitatively summarized, highlighting an overall reduction in pain intensity after the first two weeks of treatment, except for two cases requiring additional analgesic support. Local infection and critical colonization were assessed according to the NERDS/STONES criteria and were managed with DACC dressings in three cases. Tolerability and adverse events were reported descriptively, showing good overall safety: no major complications were observed, procedural discomfort was minimal and manageable with paracetamol or topical anesthesia, and only two patients developed mild hypertrophic scarring, successfully treated with silicone gel sheeting.

Data capture and management were performed using the institutional instance of REDCap with role-based access control, audit trails, and pseudonymized study IDs. Datasets were exported from REDCap to comma-separated values (CSV) format for analysis. All analyses and figures were generated in R (version 4.5.1, released 13 June 2025) using base and stats functions for descriptive summaries, the survival package for Kaplan–Meier estimation (with censoring of the non-healed case), and ggplot2/survminer for graphical rendering and risk-table display. Scripted workflows ensured full reproducibility.

2.4. The Choice of Injectable HA+6AA Formulations

The management of skin wounds requires a personalized and dynamic approach that considers the specific characteristics of each wound and its stage in the healing process. Medical devices, such as the various Hyaluronic acid and 4 Amino acids (HA+4AA) formulations previously described, offer a versatile and adaptable solution, providing targeted responses to address the multiple clinical needs that may arise during wound treatment. (14,25) In addition to these previously described HA+4AA formulations, the present study specifically investigated the use of an injectable HA+6AA complex, which integrates six amino acids (glycine, L-proline, L-leucine, L-lysine, L-valine, and L-alanine) with sodium hyaluronate, thereby potentially enhancing the modulation of inflammation and the stimulation of collagen and elastin synthesis. (14)

This flexibility aligns with the TIMERS clinical evaluation criteria for assessment and intervention: tissue management, inflammation/infection, moisture balance, epithelial edge, regeneration and repair of tissues, and social factors.(6)

A fundamental aspect of HA+4AA formulations for managing skin lesions is their ability to adapt to the evolving needs of the healing process, supporting each phase in a specific and targeted manner.(25) In particular, the debridement phase is one of the most critical stages in wound treatment. This phase primarily aims to remove devitalized, necrotic, or non-functional tissue (tissue management), which acts as a barrier to healing, a potential substrate for bacterial proliferation, and an obstacle to the regeneration of healthy tissues. However, it is crucial for debridement to occur selectively, preserving the surrounding vital tissues to avoid compromising the repair process.(26) Advanced HA+4AA formulations play a key role in this phase by creating an optimal moist environment that facilitates the removal of cellular debris and damaged tissues while simultaneously stimulating cell migration and proliferation. Additionally, these devices promote granulation, an essential process for the regeneration of supportive tissue, preparing the wound bed for the subsequent phases of healing.(14,25)

Similarly, controlling inflammation and infection is a critical objective. The inflammatory infiltrate is a physiological initial response to injury, but if not properly managed, then it can become pathological, leading to chronic wounds and delayed healing. Formulations that include Gly, L-Pro, L-Leu, and L-Lys help modulate the inflammatory response.(14,25) These compounds support collagen synthesis, which is essential for tissue regeneration, while simultaneously reducing inflammatory mediators.(14,25)

The maintenance of moisture balance represents a key principle in the management of skin lesions, as it is closely linked to the success of the healing process. An excessively dry environment, characterized by tissue dehydration, can significantly slow down the regenerative process. Dryness hinders cell migration, which is essential for the formation of new epithelial layers, and reduces the effectiveness of immune cells responsible for removing cellular debris and bacteria. Conversely, an excess of exudate, if not managed properly, can lead to maceration, compromising the integrity of the surrounding healthy tissues and creating an environment conducive to bacterial proliferation. For this reason, medical devices that maintain an optimal moisture balance offer a significant clinical advantage. (14,25)

The management of wound edges, undermining and fistulas tracts and the stimulation of cellular regeneration to repair tissue are essential elements to reverse the chronicization of the lesion. Well-defined edges are indicative of an ongoing healing process, as they reflect the proliferation and migration of cells from the surrounding epithelium. However, in many chronic wounds, the edges may become hardened, inflamed, or ischemic, hindering wound closure. (1,6) Medical devices that stimulate fibroblast activity and collagen synthesis, such HA+4AA formulations, play a fundamental role in promoting an effective transition from the edges to the center of the wound. (14,25) Finally, social factors, such as the patient’s quality of life and the ease of use of devices. In the context of pediatric wound care, formulations that combine practicality, simplicity, and clinical effectiveness enable better patient compliance and facilitate management even in home settings or by non-professional caregivers, reducing anxiety and stress.(27–30)

Having medical devices available that address the various phases and clinical conditions of wounds optimizes the healing process and ensures a more targeted and personalized treatment. This integrated approach enables effective management of the complexity of wound care, improving clinical outcomes and reducing complications. (14,25)

These clinical considerations support the introduction of a protocol to guide the administration of injectable HA+6AA, described in detail in the following section.

The protocol

2.5. Pretreatment and NPWT Bridge

Pretreatment and NPWT bridge. The lesion is pretreated with an HA+4AA gel or cream (as detailed in the SOP) to induce moisture-driven, osmotic gradient-mediated autolysis of necrotic and non-vital tissue while stimulating early neogranulation in viable tissue. After 4-5 days, if necessary, NPWT is applied to support autolytic debridement, exudate control, and granulation as a bridge therapy; otherwise, treatment continues with the cream. This step refines the wound bed and facilitates removal of non-vital tissue from walls, base, and undermining tracts, also thanks to the preliminary gel action. NPWT is leveraged to compact fragile neogranulation (microdeformation) and increase its consistency prior to infiltration.

2.6. Pre-Infiltration Mapping

The lesion is then examined with particular attention to pediatric tissue fragility and lesion complexity. All areas of tissue deficit and undermining are mapped-these define the injection depots to accelerate healing via matrix protein biosynthesis and collagen production, following spacing and depth parameters in the SOP.

2.7. Mechanistic Rationale

At the molecular level, injectable HA+AA has been associated with up-regulation of TGF-β1 and anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10), promoting resolution of chronic inflammation, fibroblast activation, and collagen/elastin synthesis. Concurrently, increased local VEGF supports neoangiogenesis and granulation, while endothelial eNOS-derived nitric oxide (NO) contributes to antimicrobial action and apoptosis of chronic inflammatory cells. (14) These converging pathways underpin the clinical effects observed-matrix deposition, granulation compaction, and accelerated re-epithelialization. (7,14,15,25)

2.8. Ten-Points Operating Checklist

Before proceeding with the injection there are 10 points that must be respected: 1) stressless; 2) clean cleanse; 3) disinfection; 4) syringe and needles; 5) accurate preparation; 6) body position; 7) moving the wound; 8) mapping; 9) avoid bleeding; 10) waiting time.

In full details:

1. Stressless. Minimize procedure-related stress and pain through caregiver/patient counseling and stepwise measures adopted by the clinical team: a) active distraction in all needle procedures; b) topical anesthesia (cream or flush dispersion) when needed; c) deep sedation only in selected cases (severe agitation, Autism Spectrum Disorder, complex comorbidities). Intranasal agents were used occasionally at the team’s discretion (21-24).

2. Clean cleanse. Gently cleanse the wound bed using non-ionic, no-rinse solutions (ozonated oils or surfactants), avoiding anionic or cationic products (25-26).

3. Disinfection. Disinfect periwound skin with 2% chlorhexidine and the wound and periwound edges with PHMB; maintain 10 min contact time. Apply with gentle, non-traumatic sponges (27).

4. Syringe and needles. Prepare two needles (19 G for aspiration; 21-23 G for inoculation). Keep needles out of the child’s sight; use distraction to reduce procedural discomfort.

5. Accurate preparation. Expose the lesion in full: assess it as a volume (ragged walls, thick base, possible fistulous tracts) rather than a simple area and perimeter.

6. Body position. Choose the most comfortable position close to a parent or caregiver (often in-arms). Use cartoons or music therapy; in newborns, soothing light or color stimulation can be considered.

7. Moving the wound. Gently tension the periwound to visualize undermining and areas of greater tissue loss or necrosis.

8. Mapping. Mark undermined and poorly granulating areas with a dermographic pencil to define depots (to spacing depth see SOP).

9. Avoid bleeding. Under magnification (microsurgical loupes), avoid vascular injury and fragile early granulation. Areas of tissue with less granulation are selected first, and if bleeding occurs, moderate compression is applied (sometimes gauze compresses can be soaked in hydrogen peroxide and left on for 15-20 seconds). Significant bleeding has never been observed.

10. Waiting time. Allow a few seconds between sequential depots; withdraw the needle fully and re-enter gently for each inoculation.

Analgesia and topical anesthesia. The entire procedure can be performed after taking oral paracetamol 30 minutes beforehand and using a topical lidocaine hydrochloride spray or cream, covering it with a polyurethane film and waiting at least 15-20 minutes.

Documentation and consent. Injections of HA+6AA formulations are administered clockwise or counterclockwise, and each injection must be well documented for subsequent applications, using photographs taken after obtaining written consent from the parents or caregivers (see Ethical considerations).

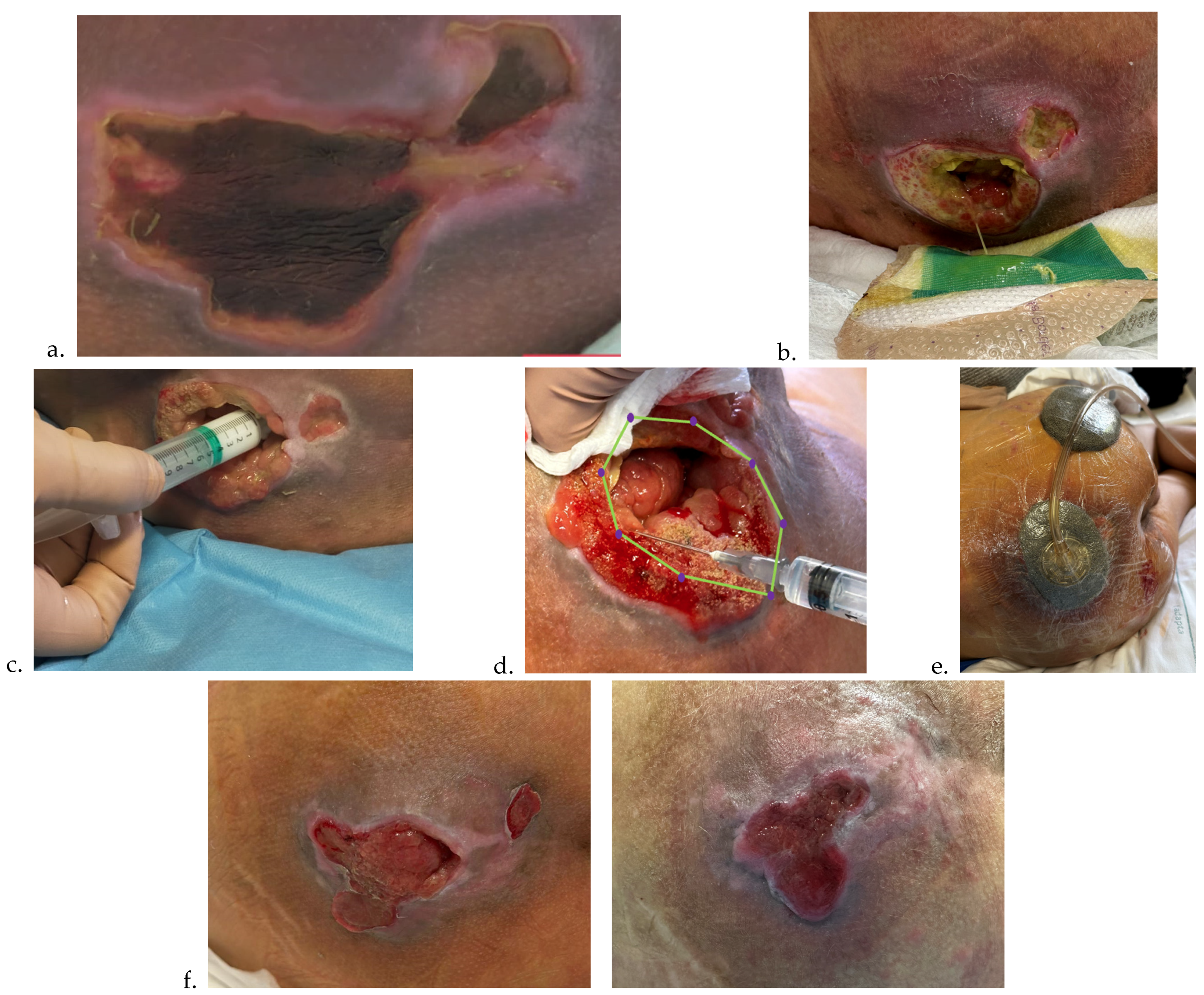

To facilitate reproducibility, the protocol was also schematized through illustrative diagrams, which summarize the sequence of pre-treatment, mapping, infiltration, and follow-up phases (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

3. Results

Fifteen pediatric patients with hard-to-heal wounds were enrolled between (period,

Table 1). The median age was 11 years [IQR 4–16], and the median wound duration prior to enrollment was 8 months [IQR 6–12]. All lesions had been previously treated in other centers with one of four different citated and used therapeutic regimens as co-interventions, without achieving complete healing. At the time of inclusion, wounds were staged according to EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA guidelines 3

rd edition released in November 2019 and the new 2025 4

th edition (presented in the September EPUAP Annual Conference in Helsinki) and were characterized by chronicity, pain (assessed with age-appropriate scales: FLACC, VAS, INRS), frequent comorbidities, and in several cases psychomotor impairment (

Table 3).

All patients received the standardized wound hygiene protocol and HA+6AA injectable treatment, combined with specific co-interventions according to predefined criteria. Eleven patients (73.3%) required NPWT as bridge therapy (2-4 dressing changes), while 3 patients (20.0%) received DACC dressings for superficial critical colonization, and none required HA+AA gel or cream pretreatment. The percentage of patients receiving each co-intervention (NPWT, DACC, HA+AA gel/cream) and the timing of their use in relation to the injectable treatment are shown in

Table 4.

Eleven of 15 patients underwent continuous negative pressure therapy at a pressure of 75 mmHg on the first day, then increased from the second day onwards to 100 mmHg, using Solventum's Acti-VAC® device, 50% reduced-thickness macrofoam filler, and tailoring to adapt the device to the shape and size of the pediatric wounds. The primary indications for use were heavy exudate, severe pain at onset, stage IV, and stage III wounds with more extensive undermining. NPWT was used for a maximum of three consecutive changes every four days and applied 30 minutes after the injections, thus simultaneously. In three cases where slough, bad odor, and extensive undermining were present, we also used a DACC liner for the first two applications. The aim of this study was not to identify two groups of patients treated with HA+AA alone or in combination with NPWT: NPWT was used according to the criteria described above to avoid unnecessary antibiotic therapy in patients with repeated therapies performed elsewhere, poor venous status, neurosensory pain, and difficult conceiving, often with repeated refusals by parents who were very distressed by the long period of non-healing wounds.

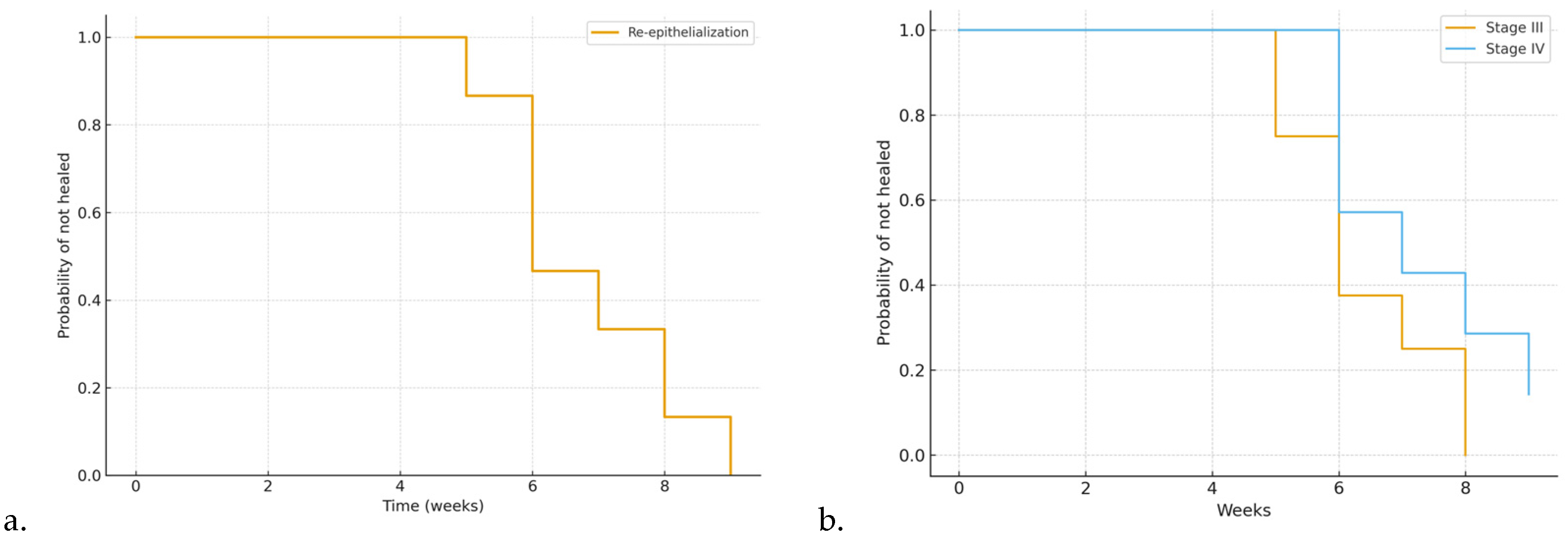

Complete healing was achieved in 14 out of 15 patients (93.3%). The median time to complete re-epithelialization was 6 weeks [IQR 5-12], as shown by the Kaplan-Meier survival curve (

Figure 1a). Kaplan-Meier time-to-event analysis confirmed a progressive increase in the cumulative probability of complete re-epithelialization, with 50% of patients healed by week 6 and over 90% by week 12, while one patient remained censored at the end of follow-up. The corresponding risk table, indicating the number of patients at risk per week, is presented in

Table 5. Stratification by wound stage demonstrated a slower healing trajectory in stage IV compared with stage III lesions (

Figure 1b).

Figure 3.

In

Figure 3a is reported the Kaplan-Meier curve for time to complete re-epithelialization in the overall cohort. In

Figure 3b, instead, is reported the Kaplan-Meier curves stratified by wound stage (III vs. IV).

Figure 3.

In

Figure 3a is reported the Kaplan-Meier curve for time to complete re-epithelialization in the overall cohort. In

Figure 3b, instead, is reported the Kaplan-Meier curves stratified by wound stage (III vs. IV).

Two cases showed a tendency to relapse during follow-up, one in a patient with myelomeningocele and the other in a boy with trisomy 21.

The interval between sessions was approximately 7 ± 2 days, with a median of 6 HA+6AA injection sessions [IQR 5-12]. The median follow-up period was 14 months [IQR 8-24]. This condition was effectively stabilized through an intensified prevention bundle that included the adoption of the Double Protection Strategy during rehoming, reassessment of wheelchair seating in orthopedic clinics, more consistent and thorough nursing by natural and social caregivers, and close liaison with local nursing staff. An additional cornerstone was the integration of occupational therapy with active and passive physiotherapy, which contributed to maintaining tissue stability without recurrences or perilesional damage.

Procedural tolerability was favorable: no significant pain was reported, as all children received oral paracetamol before infiltration and, when required, topical anesthesia. The FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability) scale, the VAS (Visual Analogue Scale), and the INRS (Individualized Numeric Rating Scale) were used according to patient age. In all patients, pain subsided after the first two weeks of therapy and therefore after the first two injections. The only exceptions were two cases, one with cerebral tuberculosis and one with severe autism, in whom pain persisted almost until the end of treatment, partly due to sensory hypersensitivity and difficulty in expressing needs. No major adverse events were observed during treatment or follow-up, and no sessions had to be interrupted due to distress or bleeding. In two cases, we found a mild hypertrophic scar: in the first, it was due to repeated treatments performed at other hospitals, which created intralesional scar tissue with almost no subcutaneous tissue (case 6 in the

Table 5). The second case was a post-traumatic, infected foot lesion (case no. 10), which was intensely painful upon admission and presented serious difficulties in applying dressings. The pain caused the dressings to dislodge and require reapplying, leading to the adoption of NPWT. These two cases benefited from CAP (Cold atmospheric plasma) therapy which resolved the cicatricial hypertrophy after 4 applications of 6 sessions each. The description of all 15 cases is reported in

Table 6.

4. Discussions

This prospective case series provides preliminary evidence that the use of an injectable HA+6AA, combined with standardized wound hygiene and selected co-interventions, may represent a potentially promising therapeutic option, although the descriptive case series design without a control group limits the strength of inference. In our cohort, 14 out of 15 patients (93.3%) achieved complete healing, with a median time to re-epithelialization of 6 weeks, despite having previously undergone multiple unsuccessful treatment regimens.

Of note, two patients showed a tendency to relapse, one with myelomeningocele and one with trisomy 21. In both cases, recurrence risk was influenced by underlying factors such as cicatricial adhesions, severe motor disability, nutritional impairment, and limited social support. These findings suggest that long-term stability requires not only wound closure but also preventive strategies including rehabilitation, physiotherapy, and tailored multidisciplinary follow-up. (31)

Importantly, the therapy was well tolerated, with only minimal procedural discomfort and no serious adverse events, even in a population characterized by young age, comorbidities, and fragile skin integrity. These results suggest the feasibility and apparent safety of HA+6AA injections in complex pediatric wounds, but further comparative studies are required to confirm these preliminary observations.

The clinical benefits observed are consistent with the established biological properties of HA and AA, including hydration, modulation of inflammation, fibroblast activation, and provision of substrates for collagen and elastin synthesis. These combined mechanisms may explain the favorable healing trajectories seen in our pediatric cohort. (14)

Fibroblasts, once activated, synthesize collagen (types I and III, with a subsequent shift toward type I and IV) and glycosaminoglycans, creating a robust extracellular scaffold that supports granulation tissue. HA further enhances this process by providing a hydrated, viscoelastic gel that maintains tissue turgor, protects cells, and creates microchannels for nutrient and oxygen diffusion. The resilience and elasticity conferred by HA are especially important in pediatric patients, where wounds often occur in areas subject to high mechanical stress, such as joints or pressure points. (14,32–34) Moreover, the role of AA in supporting elastin synthesis is particularly relevant in pediatrics, as the restoration of elastic fibers may reproduce some features of fetal scarless healing, where elastin deposition is abundant and organized, in contrast with the disorganized network typically seen in adults. (35)

The AA components of the HA+6AA complex (glycine, proline, lysine, leucine, valine, and alanine) complement HA’s biological activity by directly supplying the substrates required for protein synthesis. (14) Glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline are major constituents of collagen’s triple helix, while lysine is essential for collagen cross-linking, and leucine contributes to protein and elastin synthesis. (36) These AA also support fibroblast proliferation and modulate metabolic responses to injury, counteracting catabolic states that are common in pediatric patients with chronic wounds and comorbidities. (14,25,32,33) In addition, AA participate in antioxidant defense, reducing oxidative stress and preserving the integrity of the dermo-epidermal junction, which is particularly vulnerable in children due to structural immaturity. (14,25)

This metabolic support is crucial in pediatric patients with chronic wounds, who often present protein-energy malnutrition and increased catabolic demands; providing substrates for collagen and elastin biosynthesis may therefore counteract impaired healing and enhance tissue strength. (31,37,38)

Our therapeutic strategy also incorporated the principles of wound bed preparation and the TIMERS framework, emphasizing tissue debridement, infection and inflammation control, moisture balance, and edge advancement. (6) Pretreatment with HA+6AA gel or cream promoted selective autolysis of necrotic tissue while avoiding damage to viable structures. (14) NPWT, applied in 73.3% of cases, facilitated debridement and compaction of fragile granulation tissue (39), while DACC dressings were used effectively in cases of superficial critical colonization (40,41) according to IWII NERDS/STONES criteria. (21) This multimodal and dynamic approach allowed us to adapt treatment to the evolving wound environment, an essential requirement in pediatric patients whose skin is particularly fragile and whose healing process differs from adults.

In adult populations, randomized controlled trials have shown that topical HA accelerates re-epithelialization and improves scar quality in chronic ulcers and surgical wounds. (14,42) Pediatric evidence remains scarce, but small series have reported favorable outcomes with topical HA+AA gel in burns and PUs. (12,14) However, to our knowledge, no prior studies have evaluated the injectable HA+AA complex in children. Only one pilot trial in adults with venous leg ulcers suggested improved healing trajectories with intradermal HA injections compared to standard care. (36) Our study therefore provides the first prospective pediatric data suggesting feasibility of this approach, although larger comparative trials are required.

The outcomes of our series are consistent with previous evidence on HA-based dressings and topical HA+6AA formulations, which have been shown to accelerate re-epithelialization, improve scar quality, and reduce infection risk in both adult and pediatric populations. Our findings extend these observations to the use of injectable HA+6AA, suggesting that the direct delivery of HA and AA substrates into the wound bed may enhance tissue repair by simultaneously modulating inflammation, stimulating fibroblast and endothelial activity, and supporting collagen and elastin synthesis. This mechanism may contribute to restoring chronic or recalcitrant wounds to a more physiological healing trajectory. (14,25,32)

In conclusion, the use of an injectable HA+6AA complex, within a multidisciplinary and structured wound care protocol, appears to be a safe and feasible approach to promote healing in pediatric hard-to-heal wounds. By addressing key elements of wound repair – hydration, control of inflammation, stimulation of fibroblasts, and provision of essential substrates for ECM synthesis – this strategy may offer an innovative contribution to improving outcomes and quality of life for children with complex wounds and their families. Beyond biological plausibility, the favorable tolerability profile of HA+6AA injections suggests potential practical advantages, including reduced procedural pain, decreased hospitalization time, and alleviation of caregiver burden, aspects of particular relevance in the management of children with complex wounds.(27,28)