Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

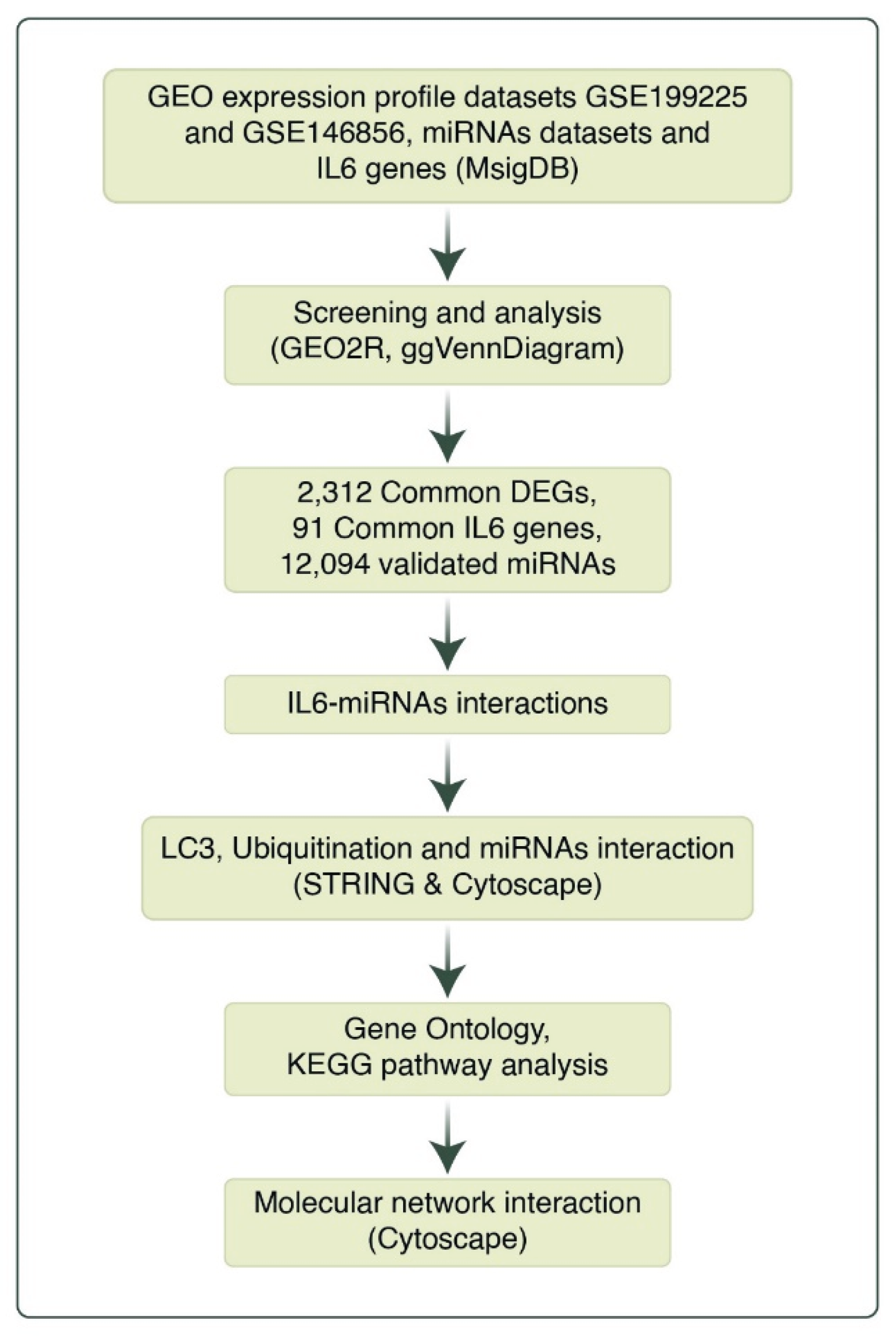

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Processing

2.2. Analysis of Microarray Datasets

2.3. Identification of miRNA-Target Interactions

2.4. Analysis of IL6 and miRNA Interactions

2.5. Analysis of miRNAs Interactions with LC3 and Ubiquitination

2.6. Network Construction of the LC3, Ubiquitination and miRNAs

2.7. Pathway Analysis of the LC3-Ubiquitination and miRNAs

2.8. qRT-PCR

2.9. Immunohistochemical Staining (IHC)

2.10. Statistical Analysis

2.11. Ethical Approval

3. Results

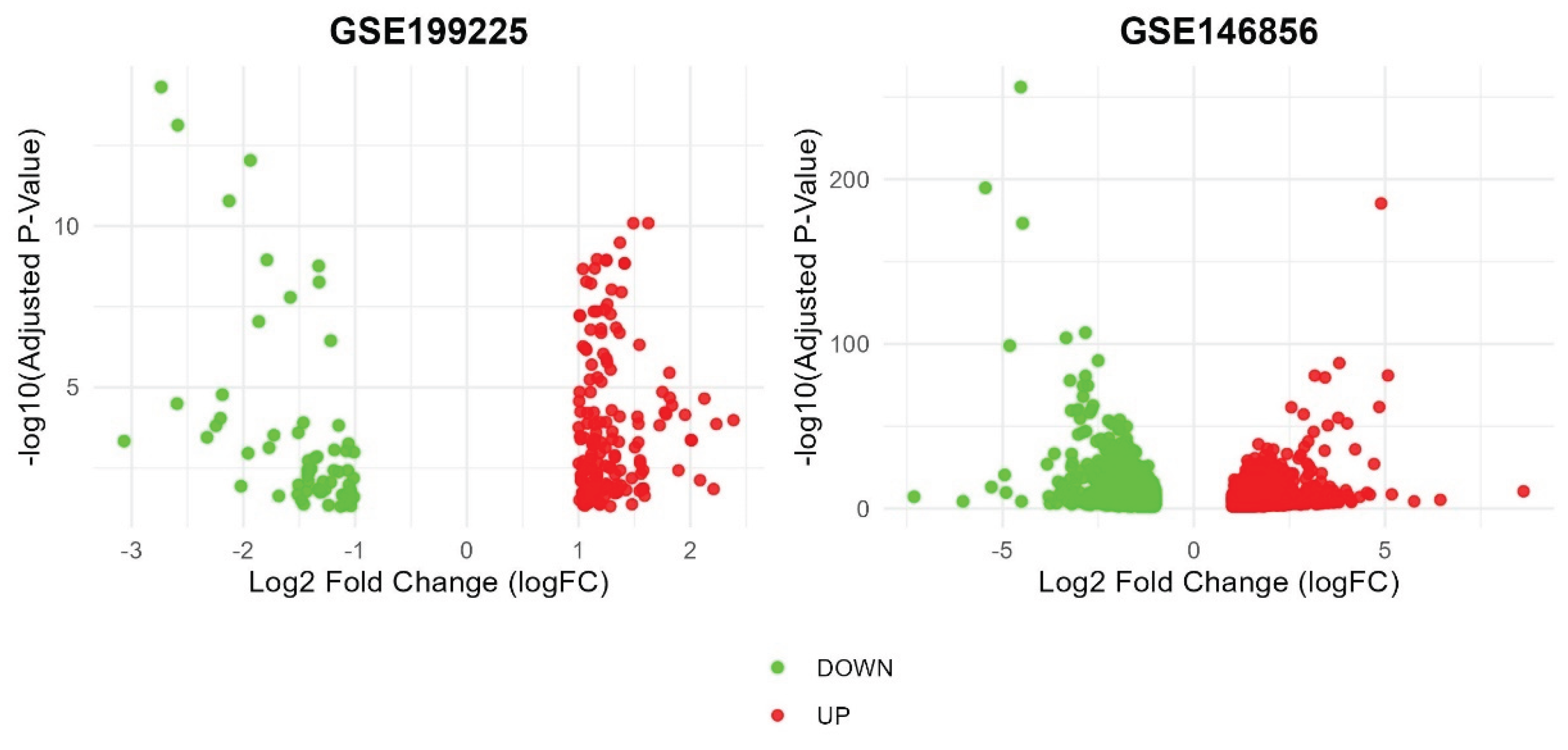

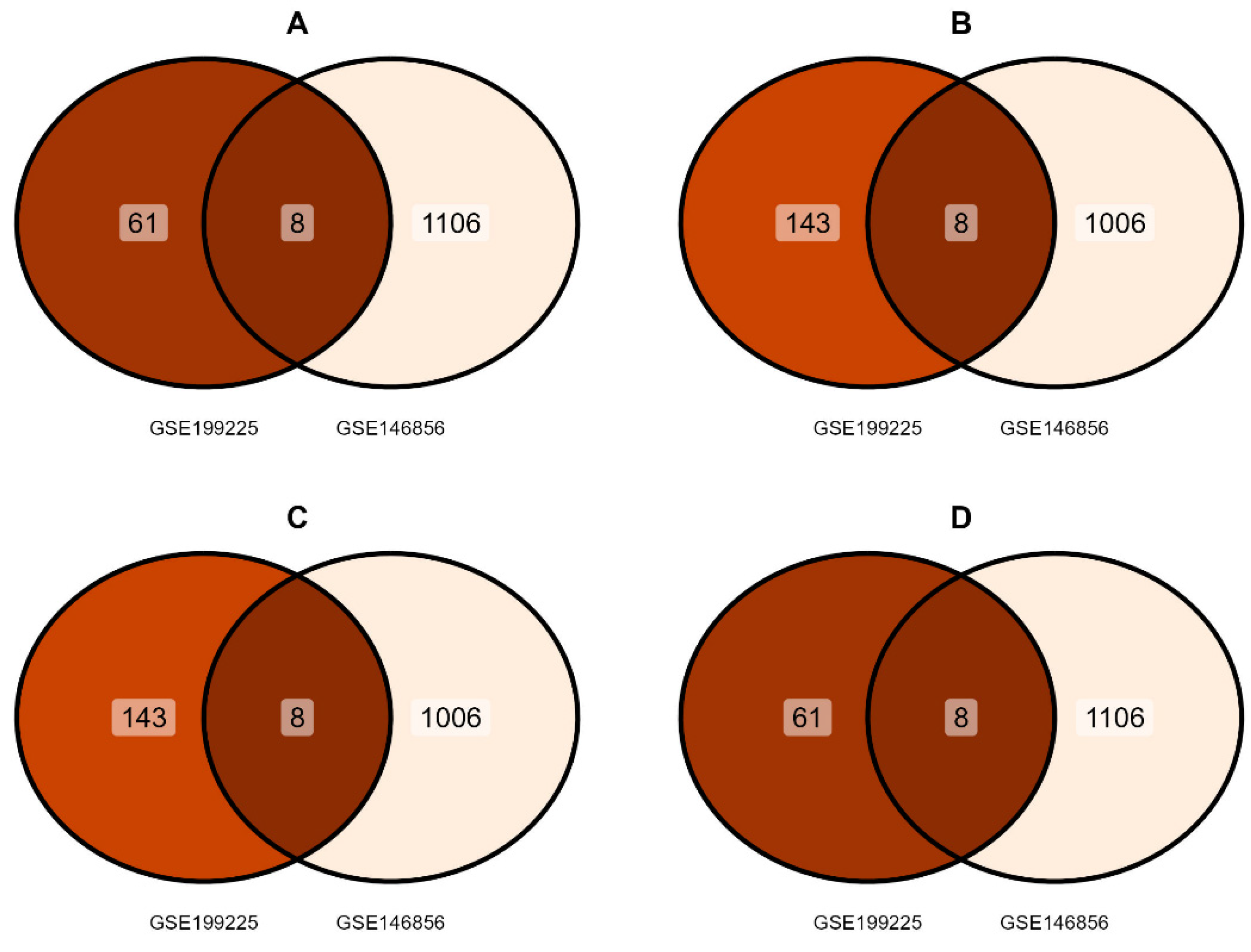

3.1. Identification of DEGs

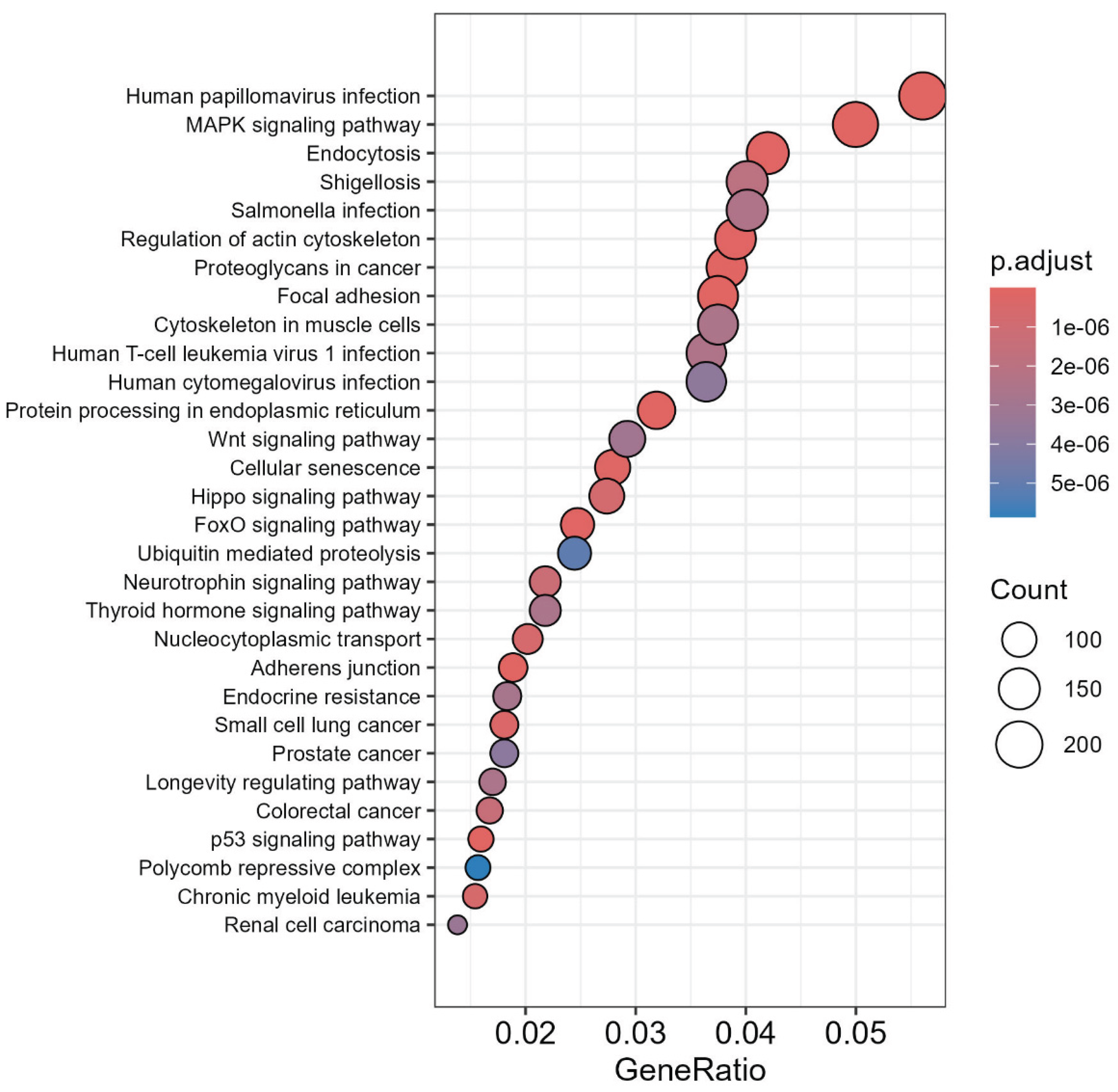

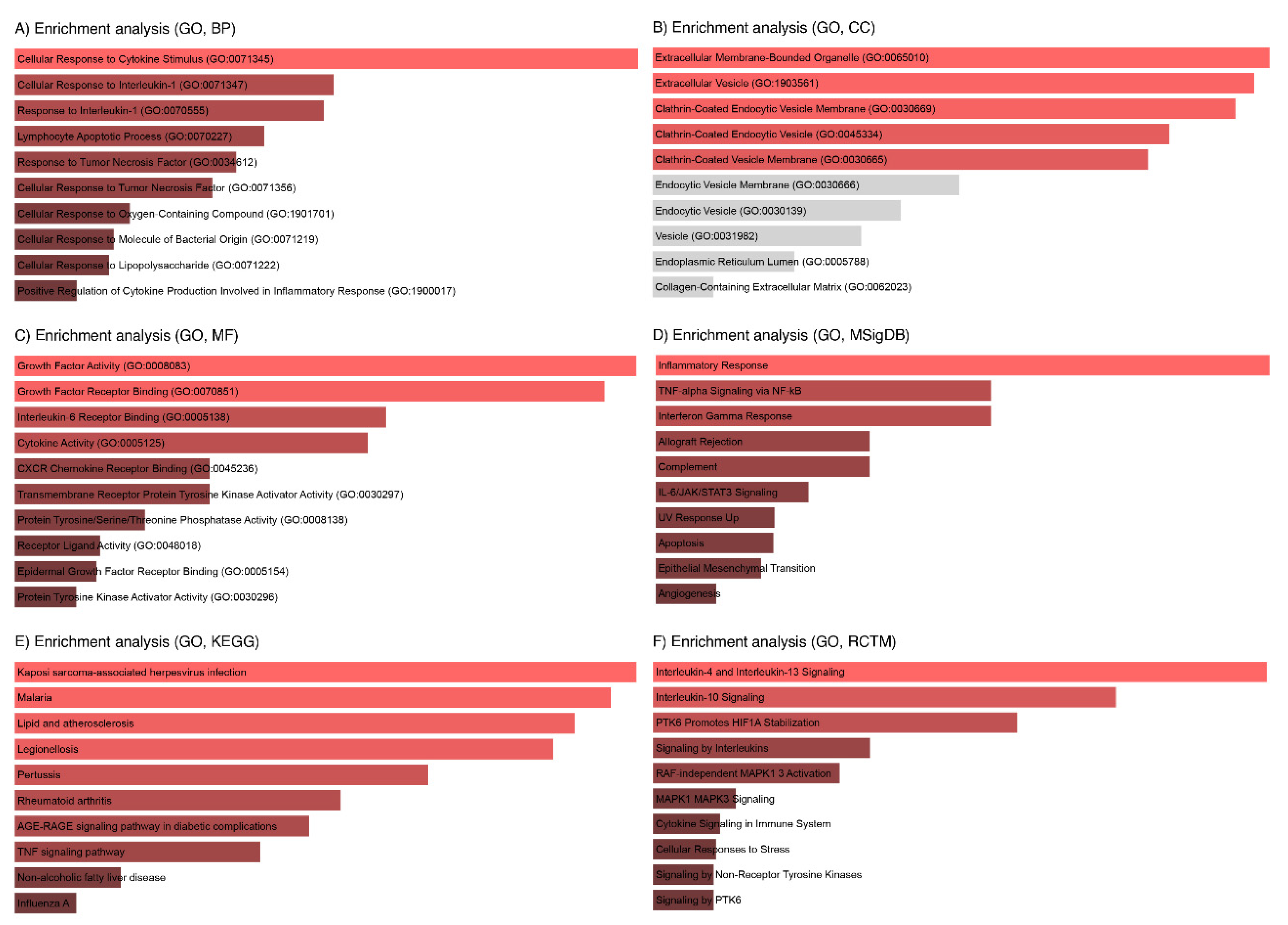

3.2. miRs Gene Target Pathway Analysis

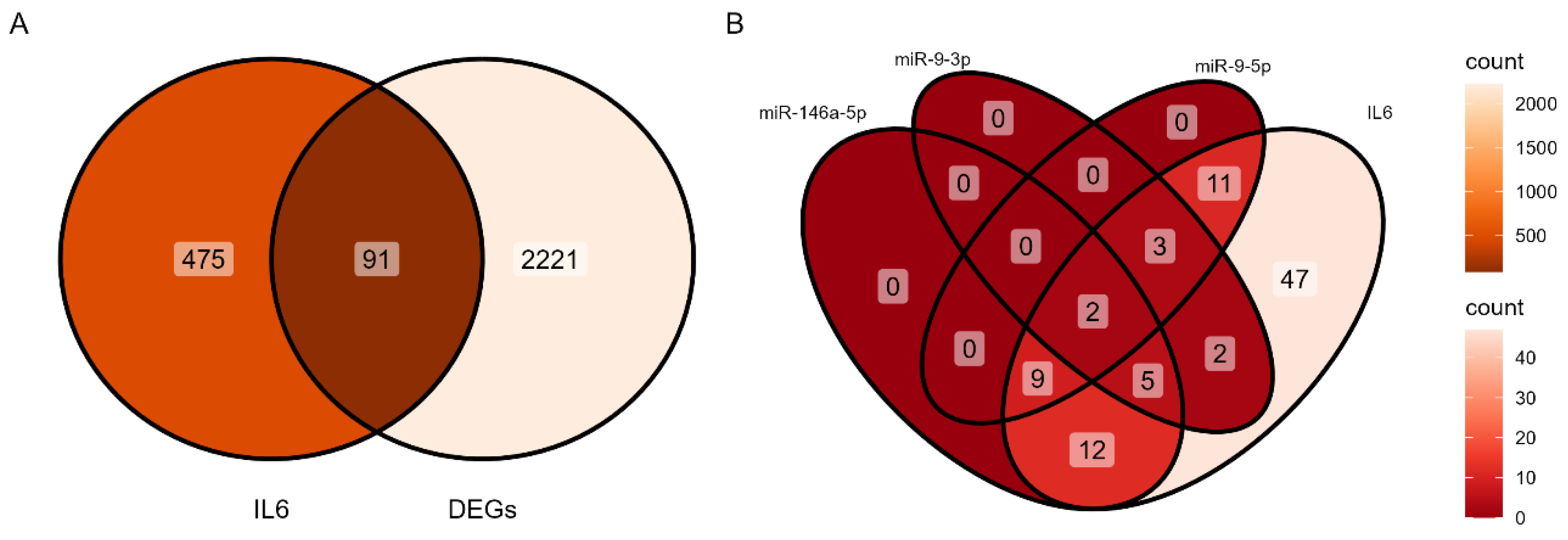

3.3. Identification of IL-6-miRNA Interactions

3.4. Enrichment Analysis of Key IL6 Genes

3.5. Identification of LC3 and Ubiquitination Interaction with miRNAs

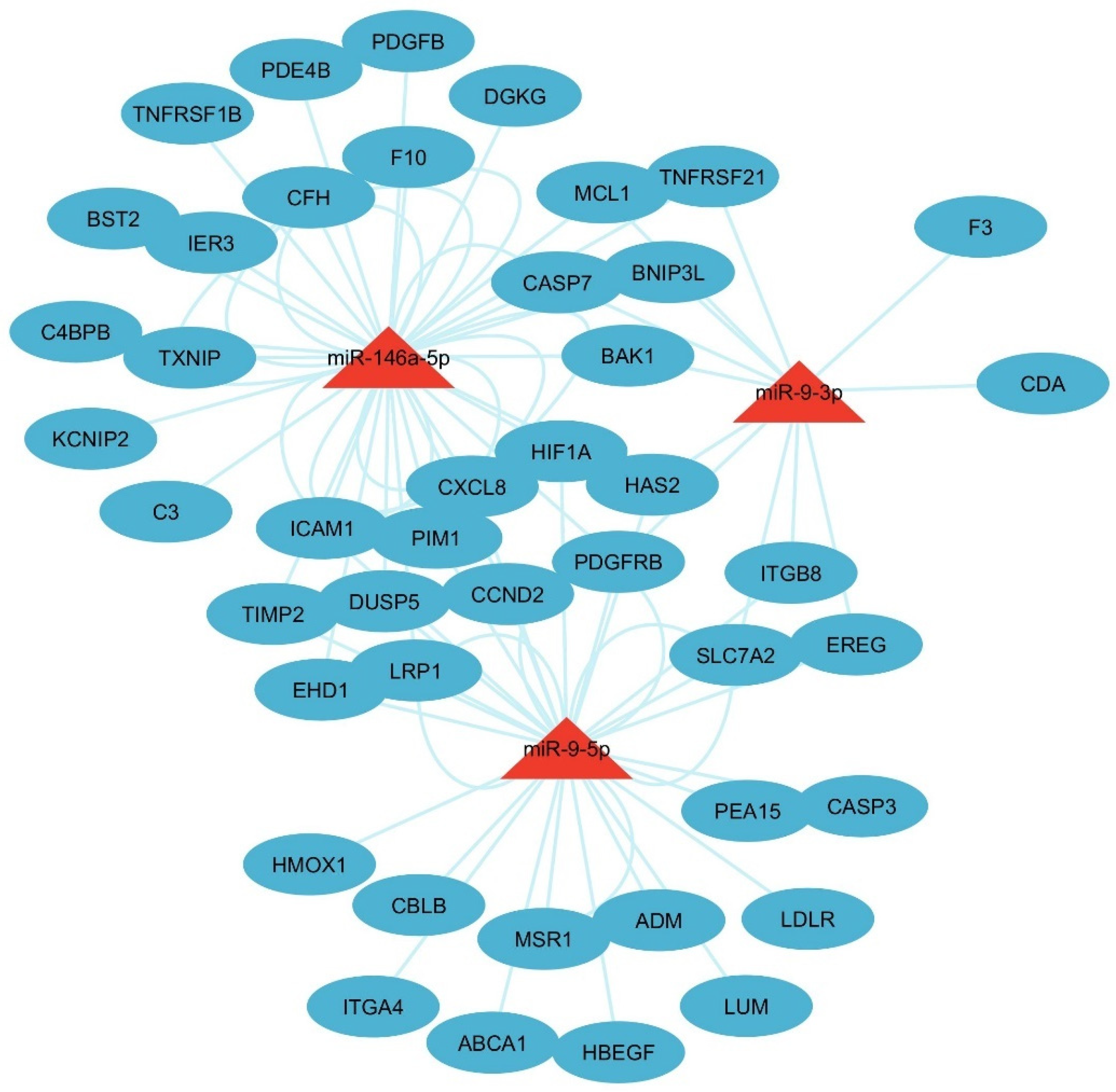

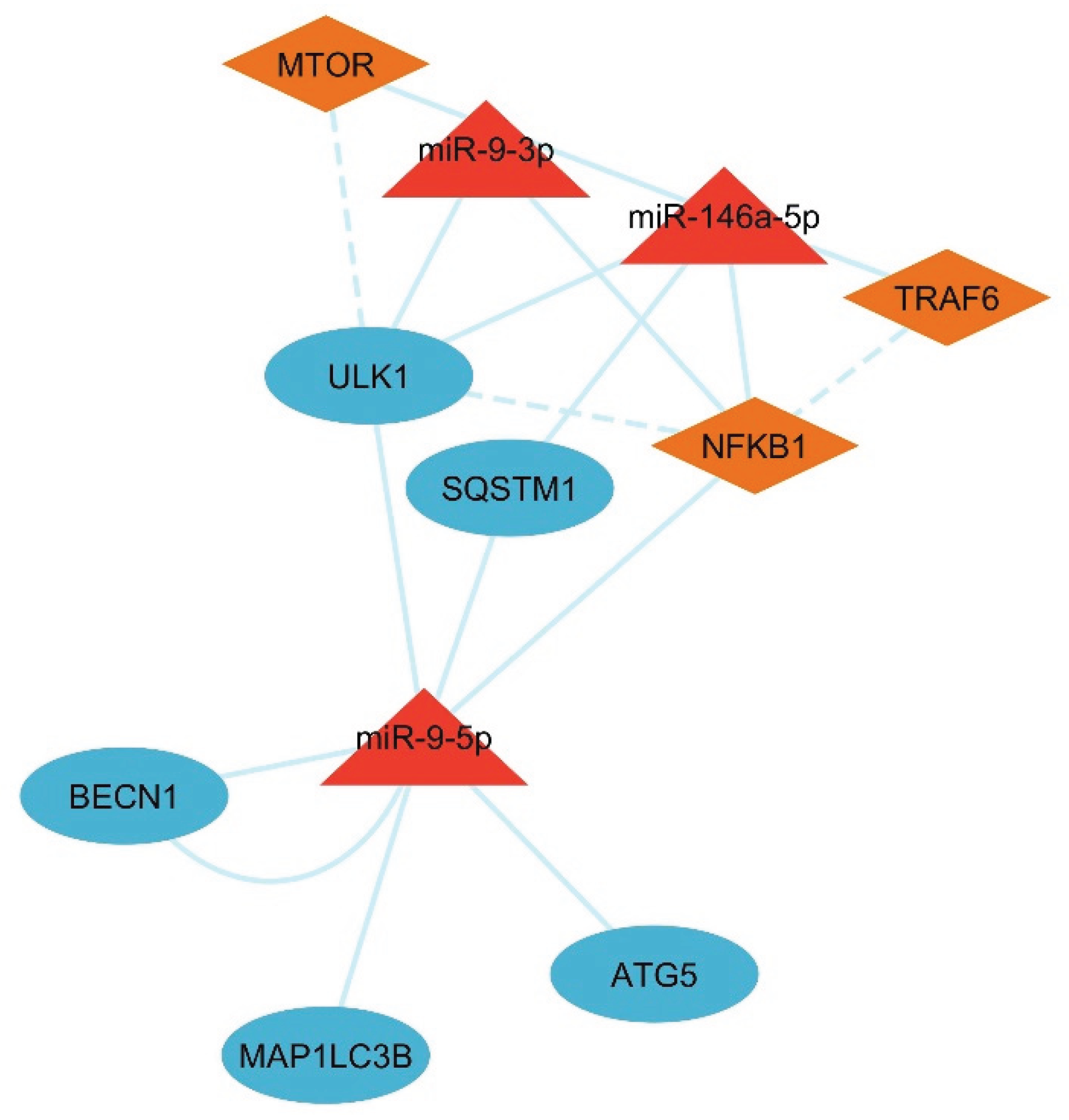

3.6. Network Analysis of the LC3-Ubiquitination and miRNAs

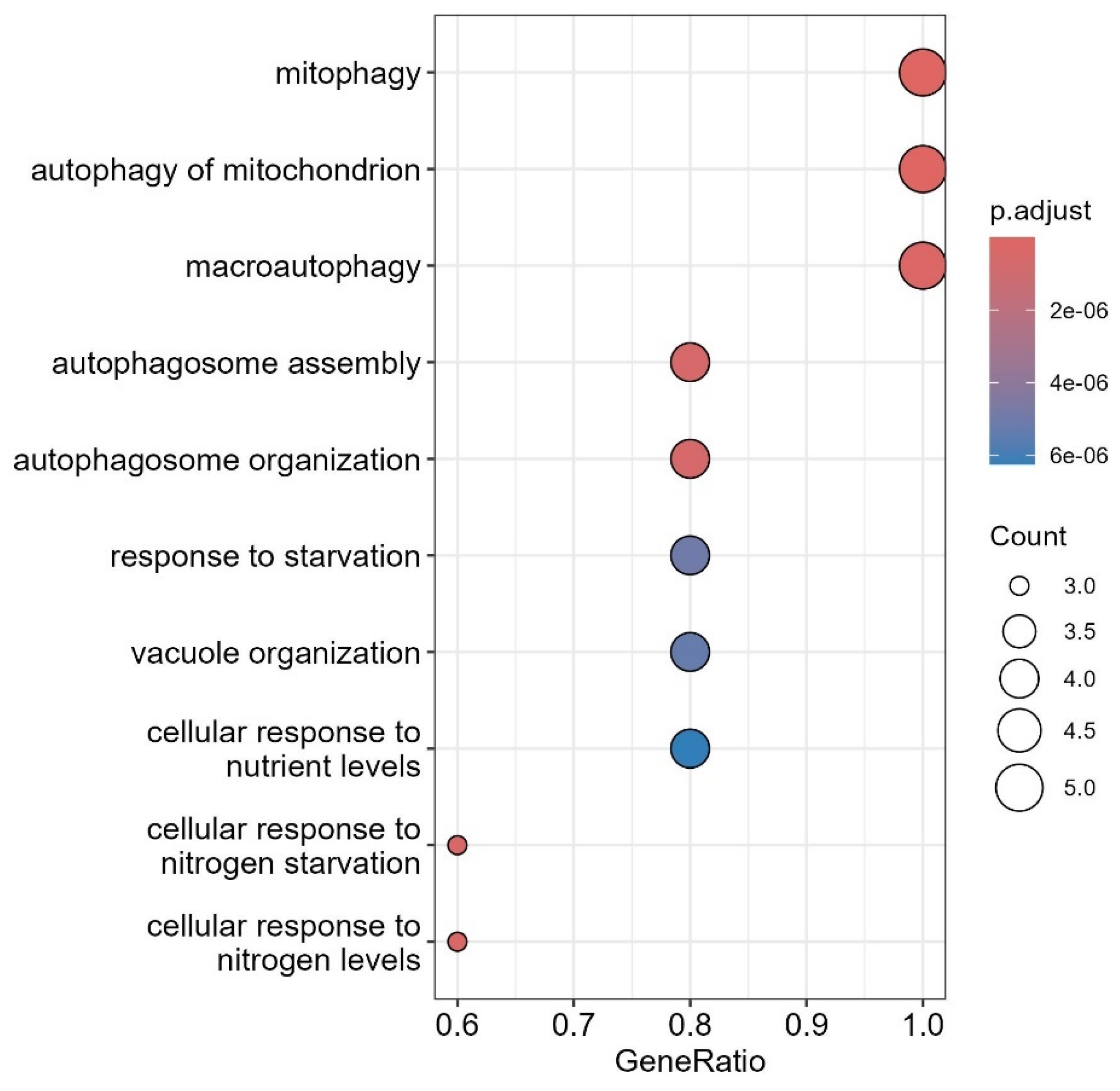

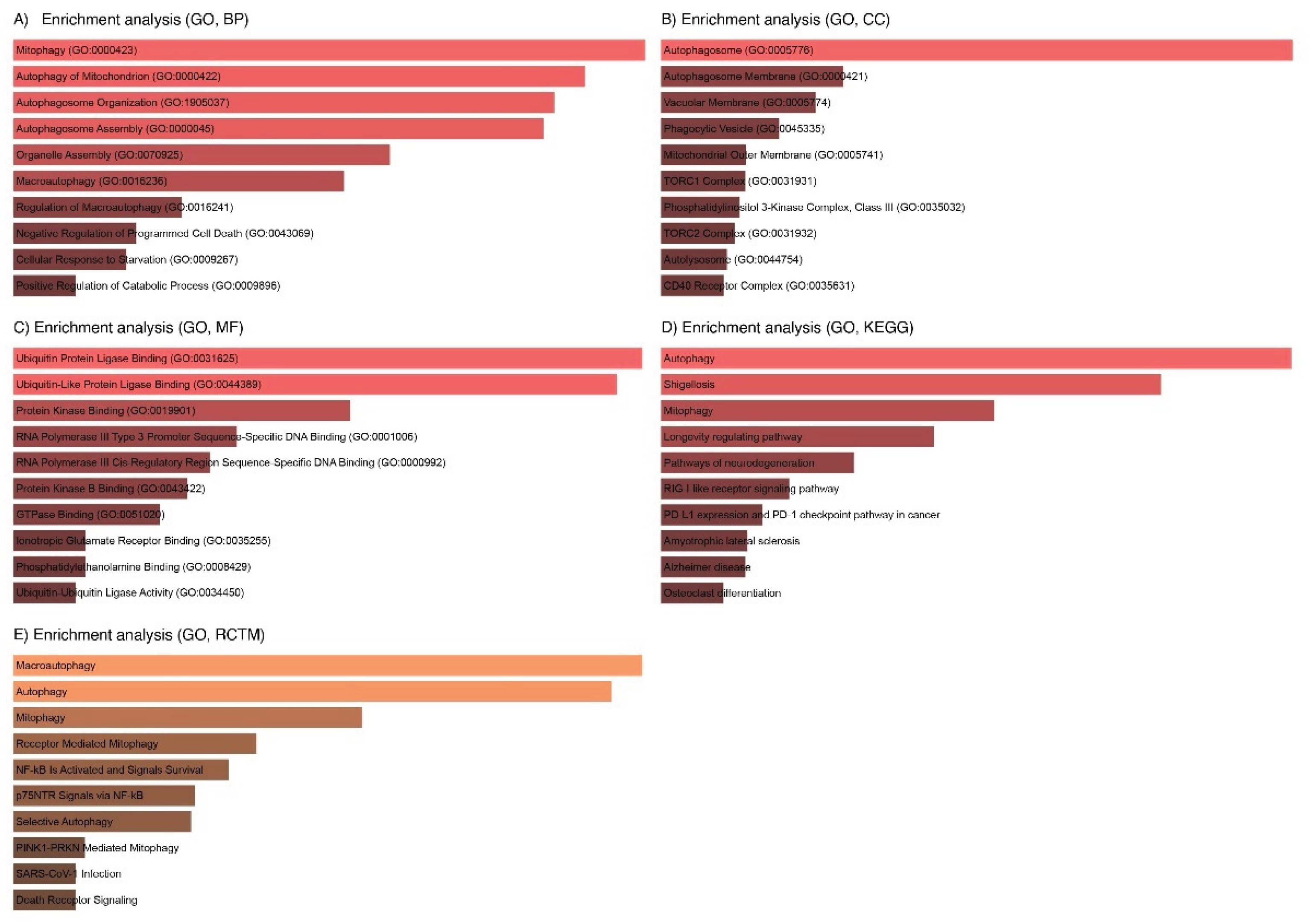

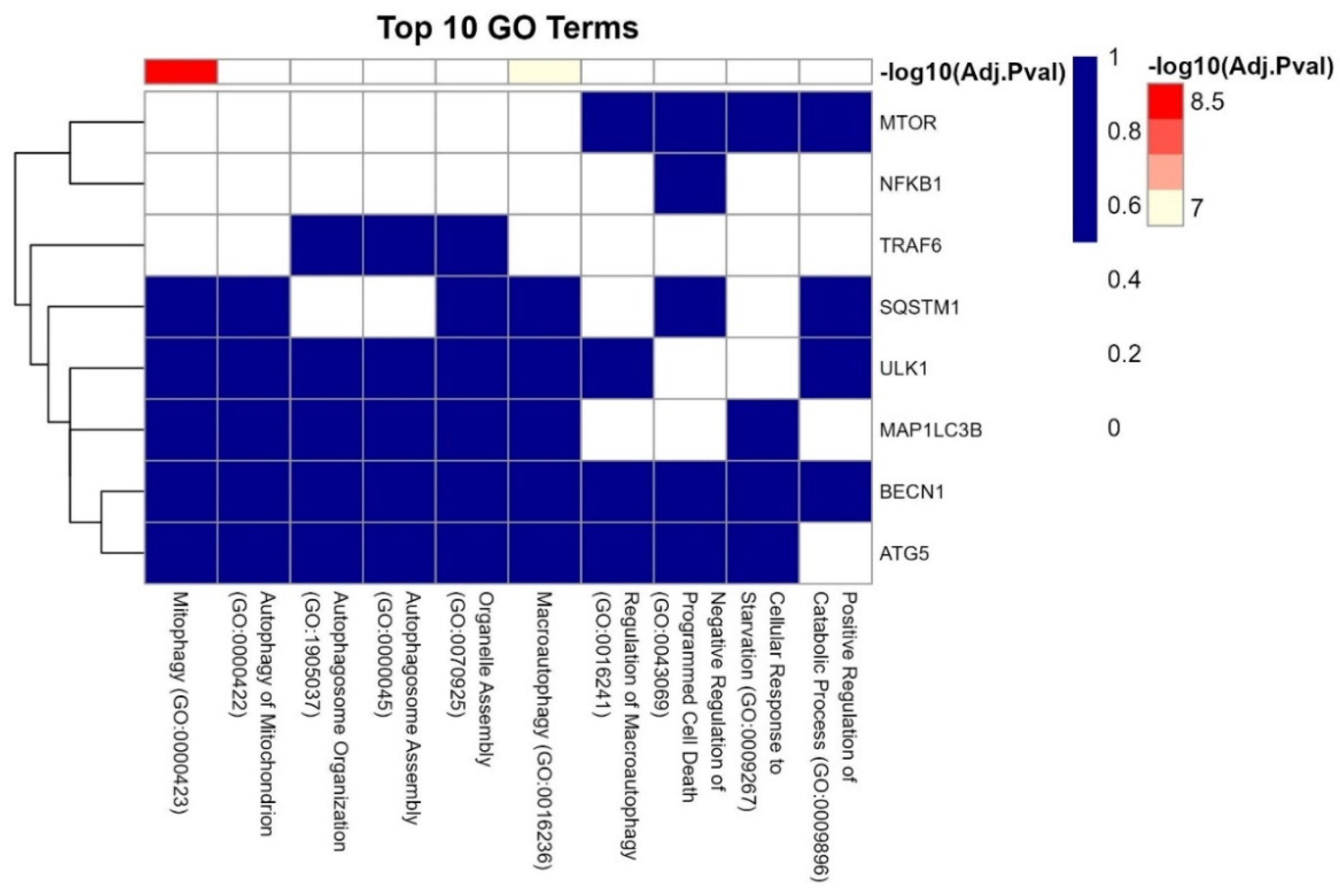

3.7. GO Analysis of the LC3-Ubiquitination and miRNAs

3.8. Interaction of LC3, IL6, and Ubiquitination Genes with Key Biological Processes

3.9. Experimental Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carson, S.A. and A.N. Kallen, Diagnosis and Management of Infertility: A Review. JAMA, 2021. 326(1): p. 65-76.

- Agarwal, A., S. Gupta, and R. Sharma, Oxidative stress and its implications in female infertility - a clinician's perspective. Reprod Biomed Online, 2005. 11(5): p. 641-50. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., et al., GnRH agonist treatment regulates IL-6 and IL-11 expression in endometrial stromal cells for patients with HRT regiment in frozen embryo transfer cycles. Reprod Biol, 2022. 22(2): p. 100608. [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka, E., et al., Chronic Low Grade Inflammation in Pathogenesis of PCOS. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(7). [CrossRef]

- Tan, B. and J. Wang, Role of IL-6 in Physiology and Pathology of the Ovary. CEOG, 2024. 51(9). [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S., L.G. Cooney, and A.K. Stanic, Immune Dysfunction in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Immunohorizons, 2023. 7(5): p. 323-332. [CrossRef]

- He, C., et al., Roles of noncoding RNA in reproduction. Frontiers in genetics, 2021. 12: p. 777510.

- Fabová, Z., et al., Does the miR-105–1-Kisspeptin Axis Promote Ovarian Cell Functions? Reproductive Sciences, 2024. 31(8): p. 2293-2308. [CrossRef]

- Sirotkin, A.V., et al., MicroRNAs control transcription factor NF-kB (p65) expression in human ovarian cells. Functional & Integrative Genomics, 2015. 15(3): p. 271-275. [CrossRef]

- Carletti, M.Z., S.D. Fiedler, and L.K. Christenson, MicroRNA 21 blocks apoptosis in mouse periovulatory granulosa cells. Biol Reprod, 2010. 83(2): p. 286-95. [CrossRef]

- Ashrafnezhad, Z., et al., Evaluating the Differential Expression of miR-146a, miR-222, and miR-9 in Matched Serum and Follicular Fluid of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Patients: Profiling and Predictive Value. Int J Mol Cell Med, 2022. 11(4): p. 320-333. [CrossRef]

- Heidarzadehpilehrood, R. and M. Pirhoushiaran, Biomarker potential of competing endogenous RNA networks in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Noncoding RNA Res, 2024. 9(2): p. 624-640. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, S.M., et al., Functional microRNA involved in endometriosis. Mol Endocrinol, 2011. 25(5): p. 821-32. [CrossRef]

- Faraji, M., et al., Elevated expression of microRNA-155, microRNA-383, and microRNA-9 in Iranian patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Biochem Biophys Rep, 2025. 42: p. 101997. [CrossRef]

- Kong, F., C. Du, and Y. Wang, MicroRNA-9 affects isolated ovarian granulosa cells proliferation and apoptosis via targeting vitamin D receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2019. 486: p. 18-24. [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.M.K., S.W. Ryter, and B. Levine, Autophagy in Human Health and Disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 2013. 368(7): p. 651-662.

- Kumariya, S., et al., Autophagy in ovary and polycystic ovary syndrome: role, dispute and future perspective. Autophagy, 2021. 17(10): p. 2706-2733. [CrossRef]

- Ji, R., et al., BOP1 contributes to the activation of autophagy in polycystic ovary syndrome via nucleolar stress response. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2024. 81(1): p. 101. [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N. and M. Komatsu, Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell, 2011. 147(4): p. 728-41. [CrossRef]

- Tsakiri, E.N. and I.P. Trougakos, The amazing ubiquitin-proteasome system: structural components and implication in aging. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol, 2015. 314: p. 171-237.

- Sun, L., et al., The E3 Ubiquitin Ligase SYVN1 Plays an Antiapoptotic Role in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome by Regulating Mitochondrial Fission. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2022. 2022: p. 3639302. [CrossRef]

- Levine, B. and G. Kroemer, Biological Functions of Autophagy Genes: A Disease Perspective. Cell, 2019. 176(1-2): p. 11-42. [CrossRef]

- McIlvenna, L.C., et al., Transforming growth factor beta1 impairs the transcriptomic response to contraction in myotubes from women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Physiol, 2022. 600(14): p. 3313-3330. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., et al., Novel PGK1 determines SKP2-dependent AR stability and reprograms granular cell glucose metabolism facilitating ovulation dysfunction. EBioMedicine, 2020. 61: p. 103058.

- Subramanian, A., et al., Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005. 102(43): p. 15545-50. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.K., et al., Differential Stability of miR-9-5p and miR-9-3p in the Brain Is Determined by Their Unique Cis- and Trans-Acting Elements. eNeuro, 2020. 7(3).

- Iacona, J.R. and C.S. Lutz, miR-146a-5p: Expression, regulation, and functions in cancer. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA, 2019. 10(4): p. e1533.

- Ru, Y., et al., The multiMiR R package and database: integration of microRNA-target interactions along with their disease and drug associations. Nucleic Acids Res, 2014. 42(17): p. e133. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, T., et al., NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets--update. Nucleic Acids Res, 2013. 41(Database issue): p. D991-5. [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R., M. Domrachev, and A.E. Lash, Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res, 2002. 30(1): p. 207-10. [CrossRef]

- Dusa, C.-H.G.a.A., ggVennDiagram: A 'ggplot2' Implement of Venn Diagram. 2024.

- Yu, G., et al., clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS, 2012. 16(5): p. 284-7. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P., et al., Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res, 2003. 13(11): p. 2498-504. [CrossRef]

- Kuleshov, M.V., et al., Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res, 2016. 44(W1): p. W90-7. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M. and S. Goto, KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res, 2000. 28(1): p. 27-30. [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D., et al., The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res, 2023. 51(D1): p. D638-D646. [CrossRef]

- Ham, J., W. Lim, and G. Song, Ethalfluralin impairs implantation by aggravation of mitochondrial viability and function during early pregnancy. Environ Pollut, 2022. 307: p. 119495. [CrossRef]

- Tuncdemir, M., et al., NFKB1 rs28362491 and pre-miRNA-146a rs2910164 SNPs on E-Cadherin expression in case of idiopathic oligospermia: A case-control study. Int J Reprod Biomed, 2018. 16(4): p. 247-254. [CrossRef]

- Virakul, S., et al., Basic FGF and PDGF-BB synergistically stimulate hyaluronan and IL-6 production by orbital fibroblasts. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2016. 433: p. 94-104. [CrossRef]

- Li, W. and Y. Zheng, MicroRNAs in Extracellular Vesicles of Alzheimer's Disease. Cells, 2023. 12(10). [CrossRef]

- Bros, M., et al., Differentially Tolerized Mouse Antigen Presenting Cells Share a Common miRNA Signature Including Enhanced mmu-miR-223-3p Expression Which Is Sufficient to Imprint a Protolerogenic State. Front Pharmacol, 2018. 9: p. 915. [CrossRef]

- Bonacini, M., et al., miR-146a and miR-146b regulate the expression of ICAM-1 in giant cell arteritis. J Autoimmun, 2024. 144: p. 103186. [CrossRef]

- Pakdaman Kolour, S.S., et al., Extracecellulr vesicles (EVs) microRNAs (miRNAs) derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in osteoarthritis (OA); detailed role in pathogenesis and possible therapeutics. Heliyon, 2025. 11(3): p. e42258. [CrossRef]

- Jia, W., et al., Immune-related gene methylation prognostic instrument for stratification and targeted treatment of ovarian cancer patients toward advanced 3PM approach. EPMA Journal, 2024. 15(2): p. 375-404. [CrossRef]

- Kraczkowska, W. and P.P. Jagodzinski, The Long Non-Coding RNA Landscape of Atherosclerotic Plaques. Mol Diagn Ther, 2019. 23(6): p. 735-749. [CrossRef]

- Faizal, A.M., et al., Unravelling the role of HAS2, GREM1, and PTGS2 gene expression in cumulus cells: implications for human oocyte development competency - a systematic review and integrated bioinformatic analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2024. 15: p. 1274376. [CrossRef]

- Broi, M.G.D., et al., Expression of PGR, HBEGF, ITGAV, ITGB3 and SPP1 genes in eutopic endometrium of infertile women with endometriosis during the implantation window: a pilot study. JBRA Assist Reprod, 2017. 21(3): p. 196-202.

- Liao, C., et al., Effect of Chitosan-assisted Combination of Laparoscope and Hysteroscope on the Levels of IFN-gamma and ICAM-1 in Treatment of Infertility Caused by Obstruction of Fallopian Tubes. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand), 2023. 69(4): p. 101-104. [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, R.A., et al., Autoimmune regulator (AIRE): Takes a hypoxia-inducing factor 1A (HIF1A) route to regulate FOXP3 expression in PCOS. Am J Reprod Immunol, 2023. 89(2): p. e13637. [CrossRef]

- Samare-Najaf, M., et al., The constructive and destructive impact of autophagy on both genders' reproducibility, a comprehensive review. Autophagy, 2023. 19(12): p. 3033-3061. [CrossRef]

- Jenabi, M., et al., Evaluation of expression CXCL8 chemokine and its relationship with oocyte maturation and embryo quality in the intracytoplasmic sperm injection method. Mol Biol Rep, 2022. 49(9): p. 8413-8427. [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.E., et al., Autophagy in Female Fertility: A Role in Oxidative Stress and Aging. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2020. 32(8): p. 550-568. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A., et al., An Update on the Study of the Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Autophagy during Bacterial Pathogenesis. Biomedicines, 2024. 12(8).

- Rahman, M.A., et al., Molecular Insights into the Multifunctional Role of Natural Compounds: Autophagy Modulation and Cancer Prevention. Biomedicines, 2020. 8(11).

- Popli, P. and R. Kommagani, Autophagy is required for stem-cell-mediated endometrial programming and the establishment of pregnancy. Autophagy, 2024. 20(4): p. 970-972. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A., et al., Therapeutic Aspects and Molecular Targets of Autophagy to Control Pancreatic Cancer Management. Biomedicines, 2022. 10(6).

- Rahman, M.A., et al., Autophagy Modulation in Aggresome Formation: Emerging Implications and Treatments of Alzheimer's Disease. Biomedicines, 2022. 10(5).

- Harrath, A.H., et al., Autophagy and Female Fertility: Mechanisms, Clinical Implications, and Emerging Therapies. Cells, 2024. 13(16). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D., et al., The Roles of Autophagy in the Genesis and Development of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Reprod Sci, 2023. 30(10): p. 2920-2931. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., et al., miR-146a-5p Plays an Oncogenic Role in NSCLC via Suppression of TRAF6. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2020. 8: p. 847. [CrossRef]

- Vergani, E., et al., miR-146a-5p impairs melanoma resistance to kinase inhibitors by targeting COX2 and regulating NFkB-mediated inflammatory mediators. Cell Commun Signal, 2020. 18(1): p. 156.

- Chen, Z., Q. Gu, and R. Chen, miR-146a-5p regulates autophagy and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in epithelial barrier damage in the in vitro cell model of ulcerative colitis through the RNF8/Notch1/mTORC1 pathway. Immunobiology, 2023. 228(4): p. 152386. [CrossRef]

- Gozuacik, D., et al., Autophagy-Regulating microRNAs and Cancer. Front Oncol, 2017. 7: p. 65.

- Guan, X., et al., Mechanistic Insights into Selective Autophagy Subtypes in Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci, 2022. 23(7). [CrossRef]

- Deng, T., et al., TRAF6 autophagic degradation by avibirnavirus VP3 inhibits antiviral innate immunity via blocking NFKB/NF-kappaB activation. Autophagy, 2022. 18(12): p. 2781-2798. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T., et al., SQSTM1/p62 promotes mitochondrial ubiquitination independently of PINK1 and PRKN/parkin in mitophagy. Autophagy, 2019. 15(11): p. 2012-2018. [CrossRef]

- Dinsdale, N.L. and B.J. Crespi, Endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome are diametric disorders. Evolutionary applications, 2021. 14(7): p. 1693-1715. [CrossRef]

- Taganov, K.D., et al., NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2006. 103(33): p. 12481-6. [CrossRef]

- Harrath, A.H., et al., Autophagy and female fertility: mechanisms, clinical implications, and emerging therapies. Cells, 2024. 13(16): p. 1354. [CrossRef]

- Harrath, A.H., et al., Benzene exposure causes structural and functional damage in rat ovaries: occurrence of apoptosis and autophagy. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2022. 29(50): p. 76275-76285. [CrossRef]

- Jalouli, M., et al., Allethrin promotes apoptosis and autophagy associated with the oxidative stress-related PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in developing rat ovaries. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2022. 23(12): p. 6397. [CrossRef]

- Oală, I.E., et al., Endometriosis and the role of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in pathophysiology: a narrative review of the literature. Diagnostics, 2024. 14(3): p. 312. [CrossRef]

- Hannan, N.J., J. Evans, and L.A. Salamonsen, Alternate roles for immune regulators: establishing endometrial receptivity for implantation. Expert Rev Clin Immunol, 2011. 7(6): p. 789-802. [CrossRef]

- Kuessel, L., et al., Soluble VCAM-1/soluble ICAM-1 ratio is a promising biomarker for diagnosing endometriosis. Hum Reprod, 2017. 32(4): p. 770-779. [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C., R.L. Feinbaum, and V. Ambros, The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. cell, 1993. 75(5): p. 843-854. [CrossRef]

- Toloubeydokhti, T., et al., The expression and ovarian steroid regulation of endometrial micro-RNAs. Reproductive sciences, 2008. 15: p. 993-1001. [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson Teague, E.M.C., et al., MicroRNA-regulated pathways associated with endometriosis. Molecular endocrinology, 2009. 23(2): p. 265-275. [CrossRef]

- Filigheddu, N., et al., Differential expression of microRNAs between eutopic and ectopic endometrium in ovarian endometriosis. BioMed Research International, 2010. 2010(1): p. 369549. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z., et al., Long noncoding RNA SNHG16 targets miR-146a-5p/CCL5 to regulate LPS-induced WI-38 cell apoptosis and inflammation in acute pneumonia. Life sciences, 2019. 228: p. 189-197. [CrossRef]

- Yan, F., et al., MicroRNA miR-146a-5p inhibits the inflammatory response and injury of airway epithelial cells via targeting TNF receptor-associated factor 6. Bioengineered, 2021. 12(1): p. 1916-1926. [CrossRef]

- Yu, F., et al., Epigenetically-Regulated MicroRNA-9-5p Suppresses the Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells via TGFBR1 and TGFBR2. Cell Physiol Biochem, 2017. 43(6): p. 2242-2252. [CrossRef]

- Morita, Y., et al., Caspase-2 deficiency prevents programmed germ cell death resulting from cytokine insufficiency but not meiotic defects caused by loss of ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (Atm) gene function. Cell Death Differ, 2001. 8(6): p. 614-20. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J., et al., Decreased expression of HOXA10 may activate the autophagic process in ovarian endometriosis. Reproductive Sciences, 2018. 25(9): p. 1446-1454. [CrossRef]

- Allavena, G., et al., Autophagy is upregulated in ovarian endometriosis: a possible interplay with p53 and heme oxygenase-1. Fertility and sterility, 2015. 103(5): p. 1244-1251. e1. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-L., et al., Autophagy in endometriosis. American Journal of Translational Research, 2017. 9(11): p. 4707.

- Genovese, M.C., et al., Interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab reduces disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis with inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: the tocilizumab in combination with traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy study. Arthritis Rheum, 2008. 58(10): p. 2968-80. [CrossRef]

- Rottiers, V. and A.M. Naar, MicroRNAs in metabolism and metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2012. 13(4): p. 239-50.

- Kanehisa, M., et al., KEGG: integrating viruses and cellular organisms. Nucleic Acids Res, 2021. 49(D1): p. D545-D551. [CrossRef]

| Gene | Functional Role | Associated Reproductive Process | Reference |

| MAP1LC3B | Autophagosome membrane formation | Impaired oocyte maturation, embryo quality | [53] |

| ATG5 | Autophagosome elongation (ATG5-ATG12 complex) | Follicular atresia, granulosa cell apoptosis | [54] |

| BECN1 | Autophagy initiation (PI3K complex) | Dysregulated autophagy in endometrial cells | [55, 56] |

| SQSTM1 | Selective autophagy of ubiquitinated proteins | Protein aggregate clearance in ovarian cells | [53, 57] |

| ULK1 | Master kinase regulating autophagy initiation | Stress response in cumulus cells | [58, 59] |

| Term | p-Value | q-Value | Overlap Genes |

| Macroautophagy | 3.325892e-12 | 5.372732e-10 | BECN1, MAP1LC3B, ULK1, SQSTM1, MTOR, ATG5 |

| Autophagy | 6.105378e-12 | 5.372732e-10 | BECN1, MAP1LC3B, ULK1, SQSTM1, MTOR, ATG5 |

| Mitophagy | 8.588874e-10 | 5.038806e-08 | MAP1LC3B, ULK1, SQSTM1, ATG5 |

| Receptor-Mediated Mitophagy | 6.919482e-09 | 3.044572e-07 | MAP1LC3B, ULK1, ATG5 |

| NF-kB Is Activated and Signals Survival | 1.198939e-08 | 4.220264e-07 | TRAF6, SQSTM1, NFKB1 |

| p75NTR Signals via NF-kB | 2.346278e-08 | 6.359648e-07 | TRAF6, SQSTM1, NFKB1 |

| Selective Autophagy | 2.529405e-08 | 6.359648e-07 | MAP1LC3B, ULK1, SQSTM1, ATG5 |

| PINK1-PRKN Mediated Mitophagy | 2.071973e-07 | 4.393258e-06 | MAP1LC3B, SQSTM1, ATG5 |

| SARS-CoV-1 Infection | 2.496169e-07 | 4.393258e-06 | BECN1, MAP1LC3B, TRAF6, NFKB1 |

| Death Receptor Signaling | 2.496169e-07 | 4.393258e-06 | TRAF6, ULK1, SQSTM1, NFKB1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).