Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods:

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Search Methodology

2.3. Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) Criteria

- Population: An eligible study should have at least five subjects with Gustilo-Anderson (GA) Type I, II, or III open extremity fractures.

-

Intervention: Any of the following acute systemic antimicrobial prophylaxis (ASAP) protocols.

- Cefazolin alone (Cef)

- Cefazolin + Gentamicin (Cef+Gent)

- Tobramycin + Cefazolin (Tobra+Cef)

- Piperacillin + Tazobactam (Pip+Tazo)

- Ampicillin + Sulbactam (Amp+Sulb)

- Cefazolin + Ciprofloxacin (Cef+Cipro)

- Flucloxacillin + Benzylpenicillin (Flu+Benz)

- Two doses of Cefazolin + Gentamicin (2Cef+Gent)

- Cefamandole + Gentamicin (Cefam+Gent)

- Ciprofloxacin (Cipro)

- Clindamycin (Clinda)

- Cloxacillin (Clox)

- Flucloxacillin (Flu)

- Cephradine (Ceph)

-

Comparison: Each intervention was compared to each other, and the following groups were specified:

-

Single dose of Cefazolin plus Gentamicin (Cef+Gent) versus:

- ➢

- Cefazolin alone (Cef)

- ➢

- Piperacillin plus Tazobactam (Pip+Tazo)

- ➢

- Ampicillin plus Sulbactam (Amp+Sulb)

- ➢

- Cefazolin plus Ciprofloxacin (Cef+Cipro)

- ➢

- Flucloxacillin plus Benzylpenicillin (Flu+Benz)

- ➢

- Two doses Cefazolin plus Gentamicin (2Cef+Gent)

- Cefazolin alone versus Piperacillin plus Tazobactam (Cef vs Pip+Tazo)

- Cefazolin plus Clindamycin versus Piperacillin plus Tazobactam (Cef/Clinda vs Pip+Tazo)

- Clindamycin versus Cloxacillin (Clinda vs Clox)

- Penicillin versus Cephradine (Pen vs Ceph)

- Cefamandole plus Gentamicin versus Ciprofloxacin (Cefa+Gent vs Cipro)

-

- Outcome: Outcome analyses of the included studies must report the post-fixation incidence of surgical site infection (SSI) and acute kidney injury (AKI). The length of hospital stay was considered as our secondary outcome.

2.5. Inclusion Criteria

2.6. Exclusion Criteria

2.7. Data Extraction

2.8. Quality Assessment of Included Studies (MINORS)

2.9. Risk of Bias Assessment of Randomized Controlled Trials

2.10. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search and Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Geographical Distribution of the Included Studies

3.4. Risk of Bias Assessment of Randomized Control Trials

3.5. Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies (MINORS)

3.6. Synthesis of Results

- 1.

-

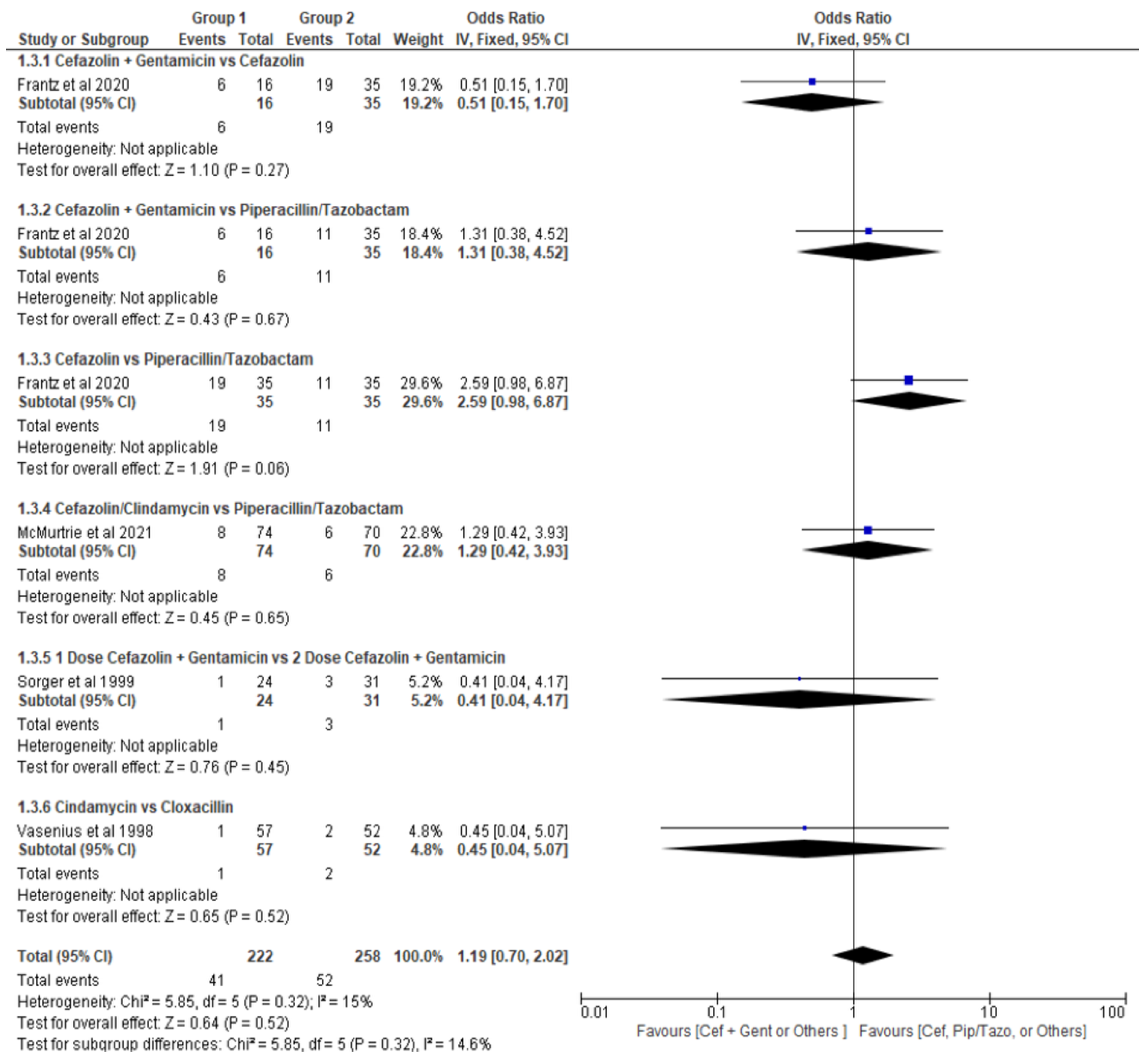

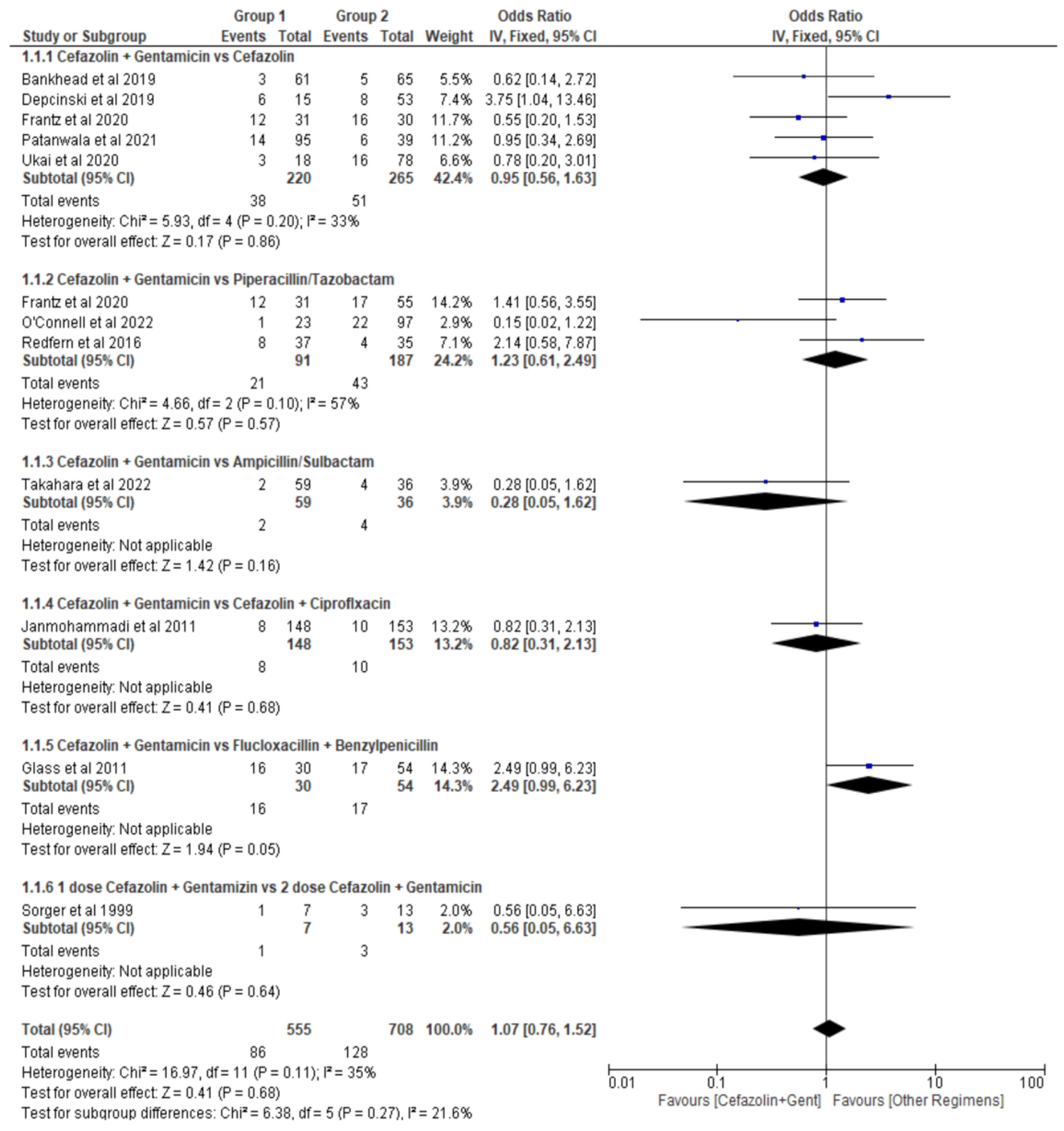

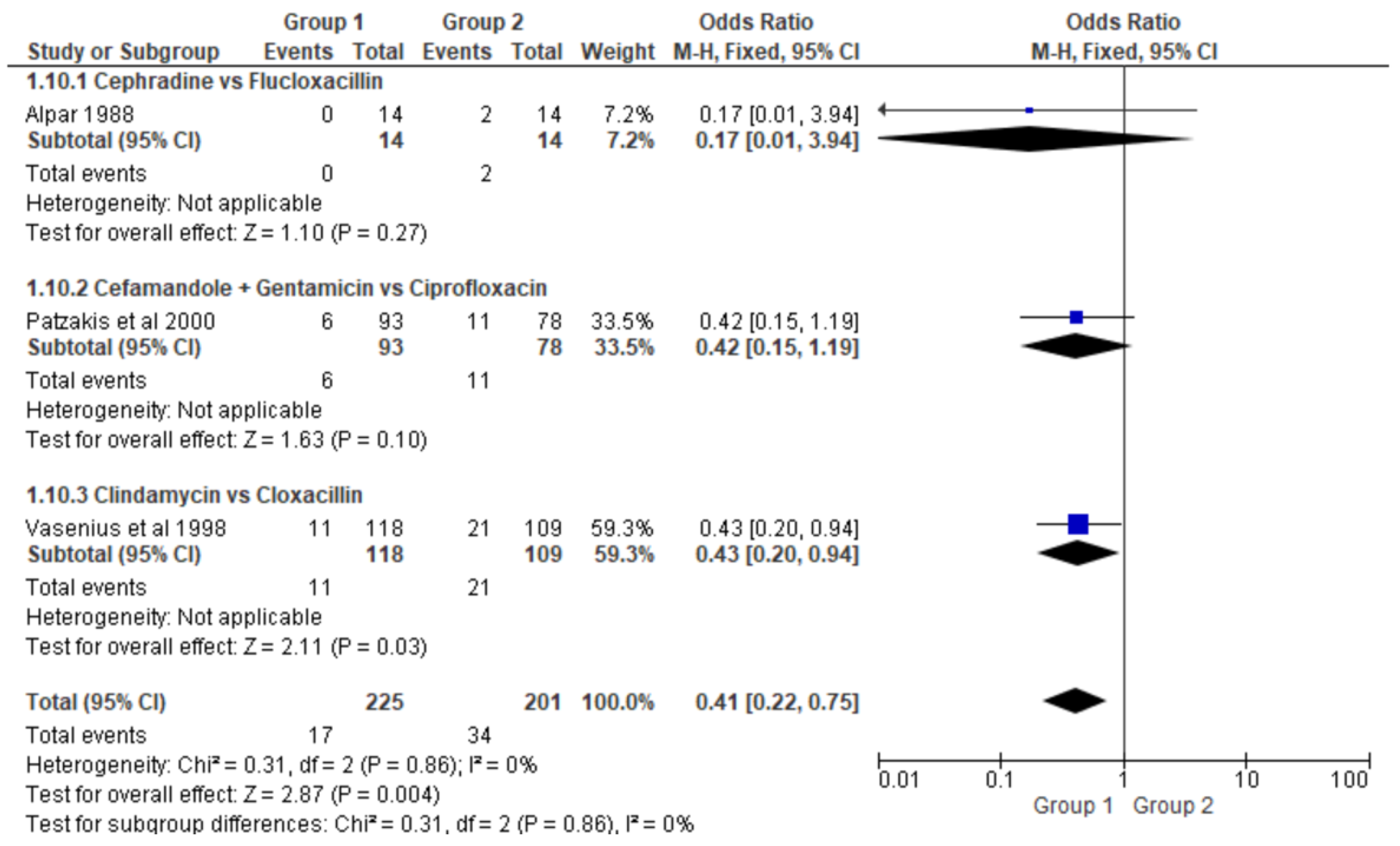

Surgical Site Infection (SSI)

- ➢

- Type I Gustilo-Anderson Open Fractures

- ➢

- Type II Gustilo-Anderson Open Fractures

- ➢

- Type III Gustilo-Anderson Open Fractures

- ➢

- Open fracture, regardless of the type.

- 2.

-

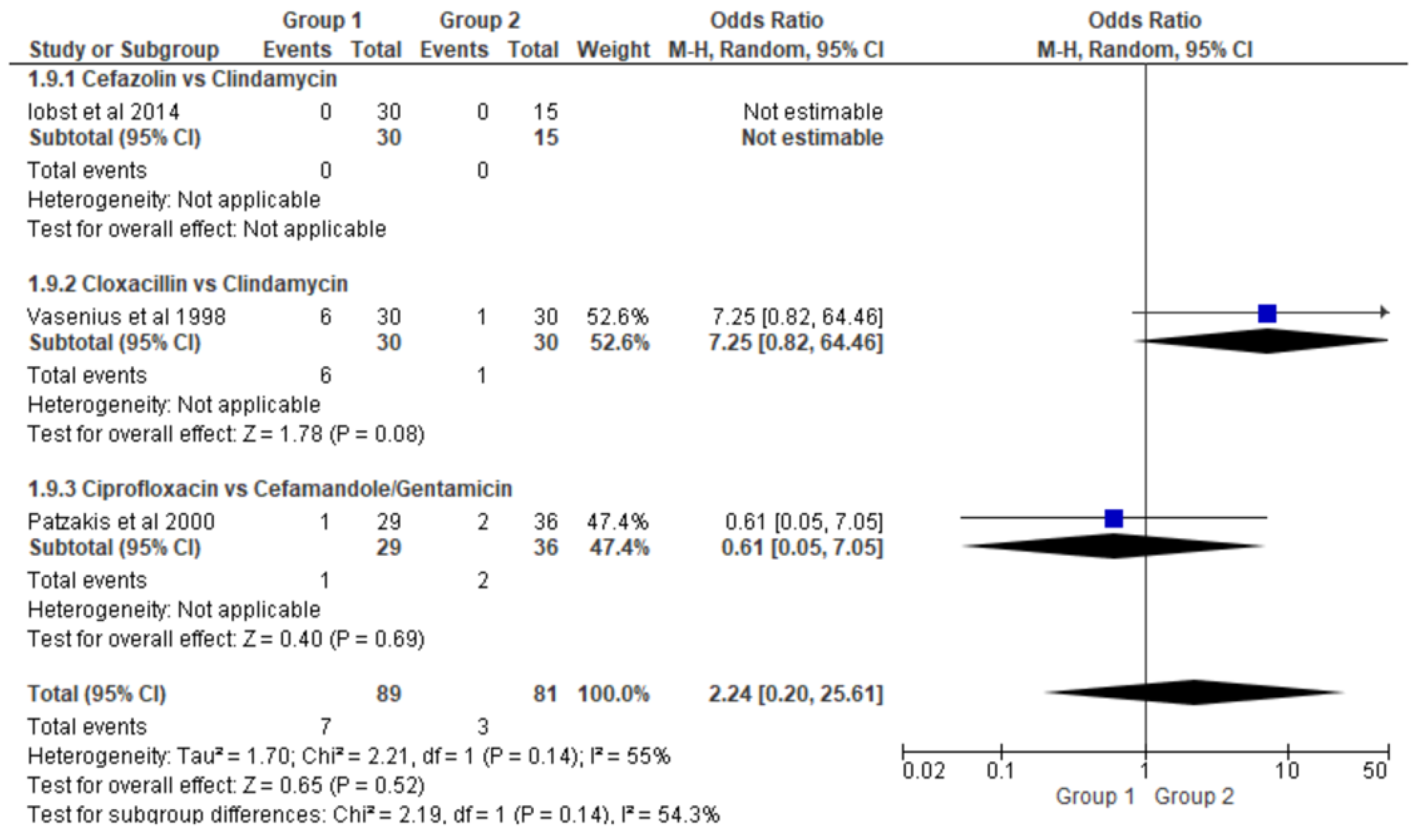

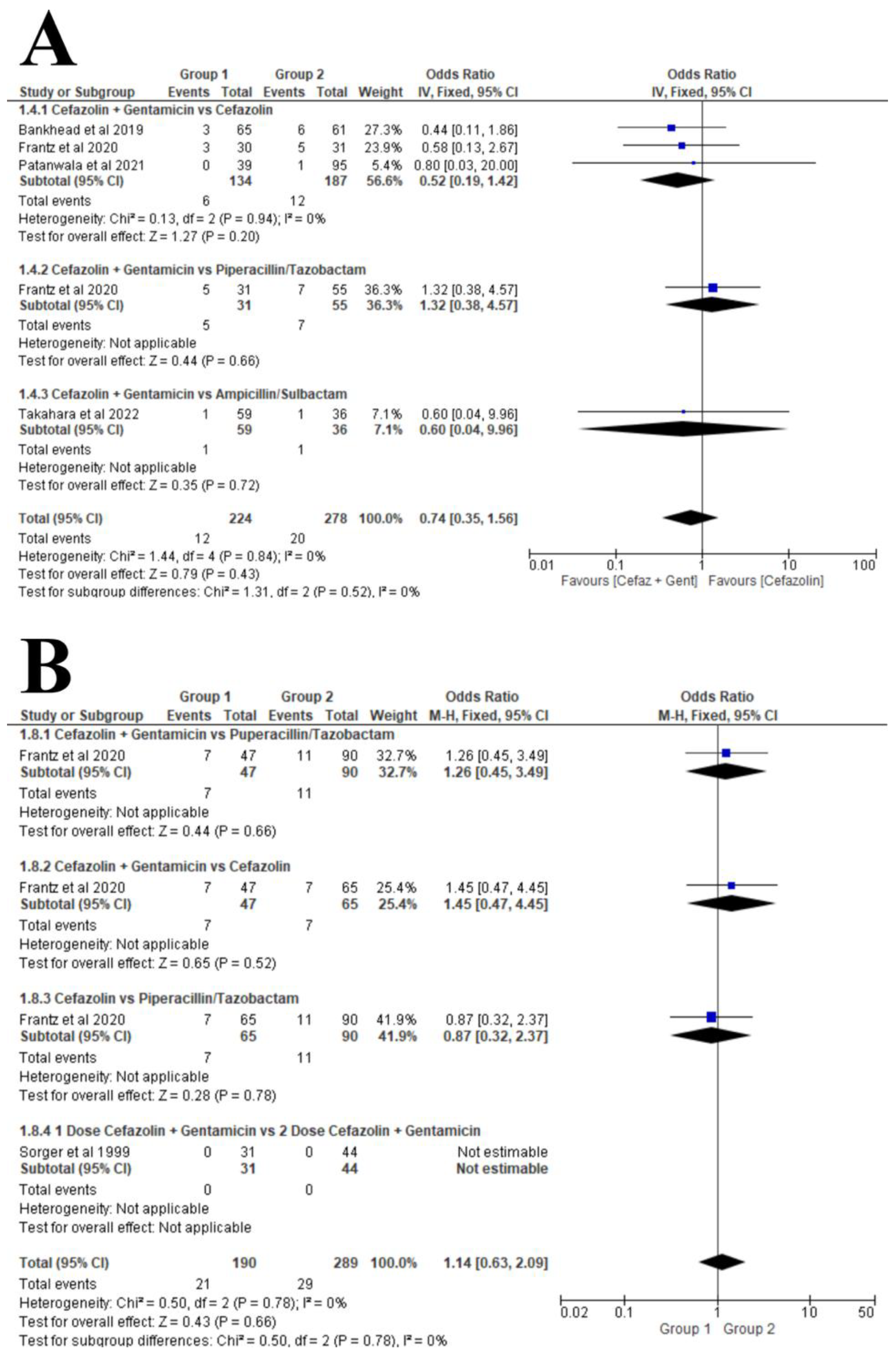

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI)

- ➢

- Type III Gustilo-Anderson Open Fractures

- ➢

- Type II & III Gustilo-Anderson Open Fractures

- 3.

-

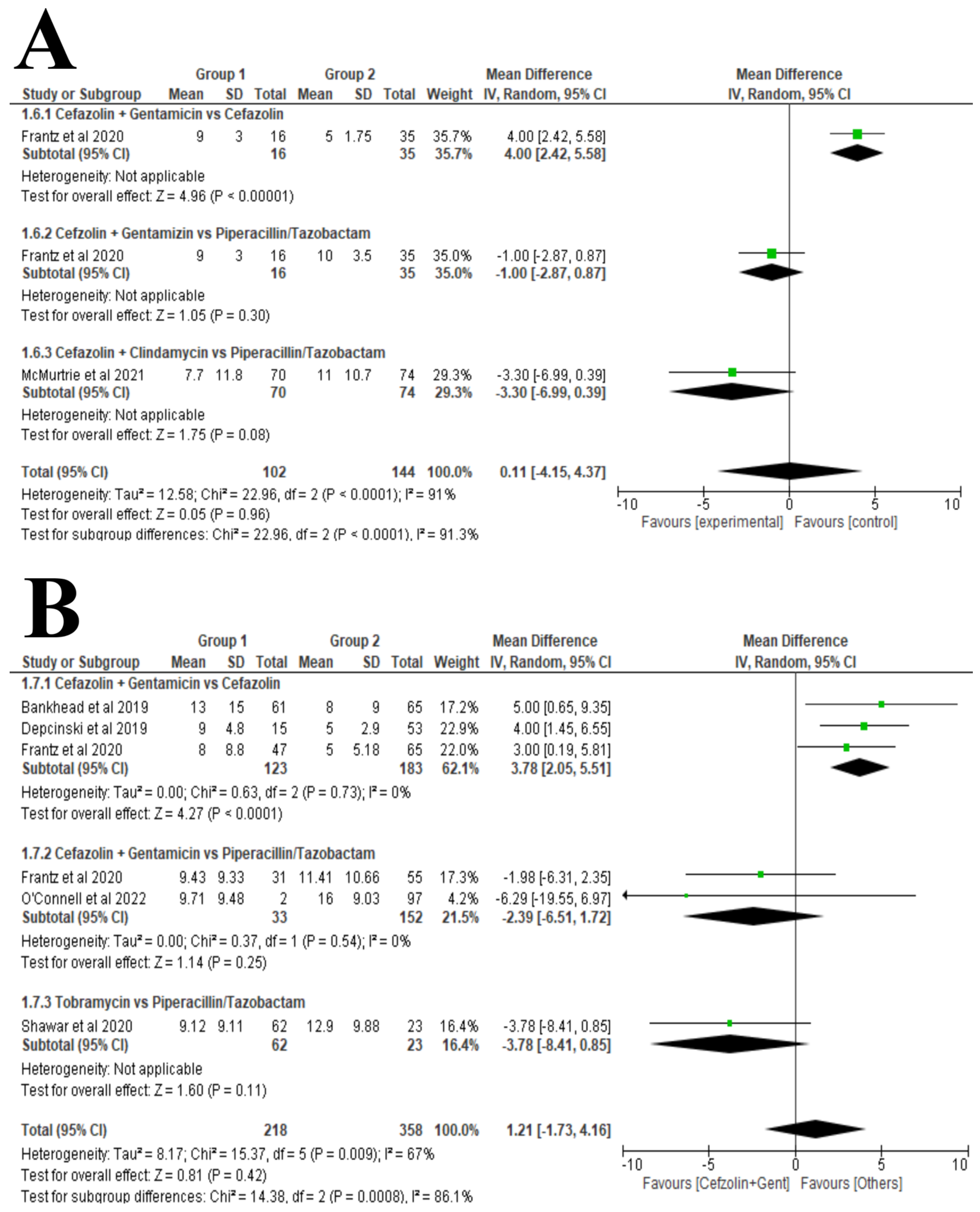

Length of Hospital Stay (LOHS)

- ➢

- Type II Gustilo-Anderson Open Fractures

- ➢

- Type III Gustilo-Anderson Open Fractures

4. Discussion

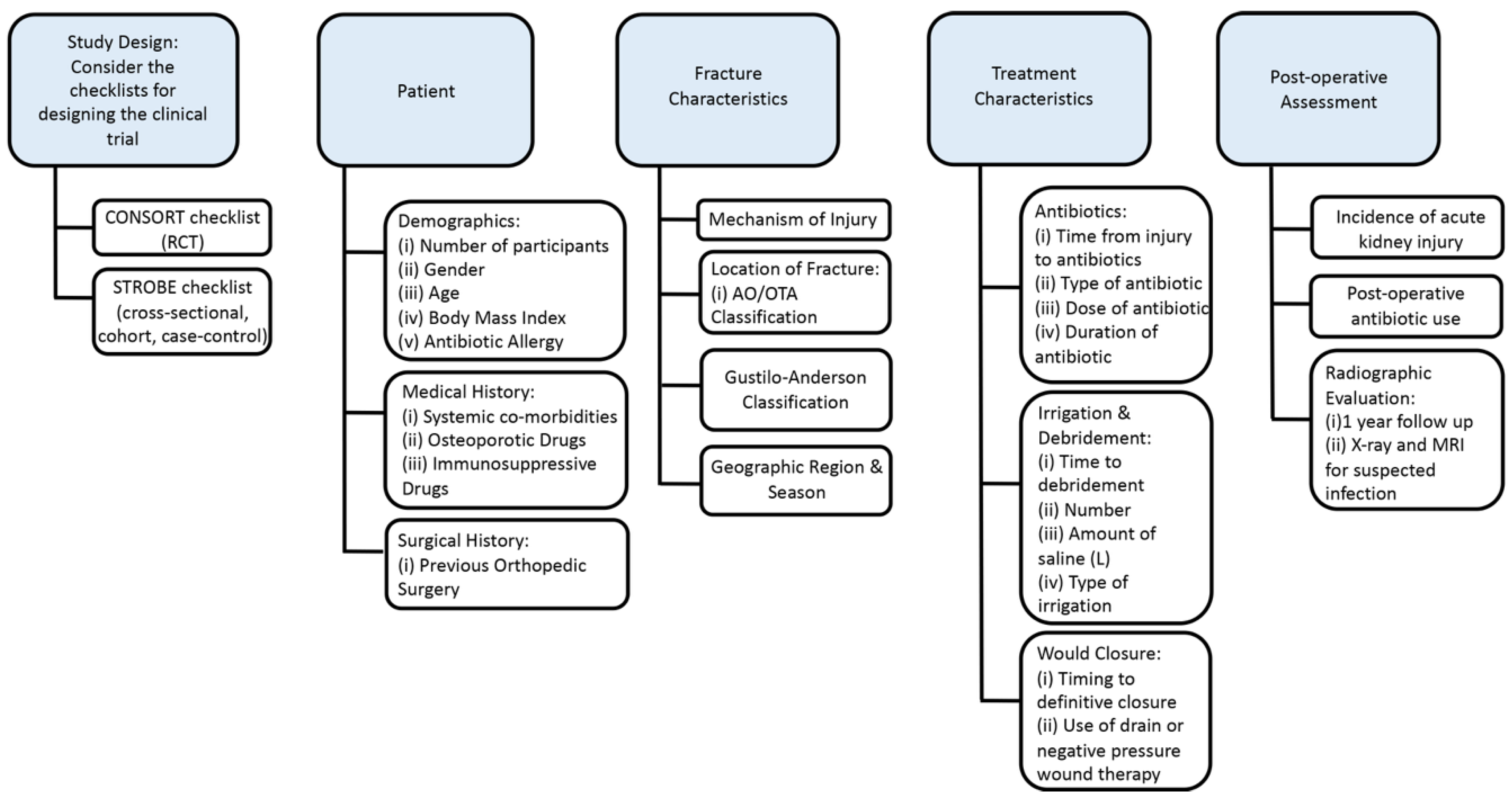

4.1. Recommendations and Guidelines for Future Trials

4.2. Study Design

4.3. Patient’s Characteristics

4.4. Fracture Characteristics

4.5. Treatment Characteristics

4.5.1. Antibiotics

4.5.2. Irrigation & Debridement

4.5.3. Would Closure

4.5.4. Post-operative Assessment

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Craig, J., et al., Systematic review and meta-analysis of the additional benefit of local prophylactic antibiotic therapy for infection rates in open tibia fractures treated with intramedullary nailing. Int Orthop, 2014. 38(5): p. 1025-30. [CrossRef]

- Lack, W.D., et al., Type III open tibia fractures: immediate antibiotic prophylaxis minimizes infection. J Orthop Trauma, 2015. 29(1): p. 1-6.

- Gustilo, R.B., R.M. Mendoza, and D.N. Williams, Problems in the management of type III (severe) open fractures: a new classification of type III open fractures. J Trauma, 1984. 24(8): p. 742-6.

- Kortram, K., et al., Risk factors for infectious complications after open fractures; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Orthop, 2017. 41(10): p. 1965-1982. [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.L., et al., Fracture-related infection: current methods for prevention and treatment. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther, 2020. 18(4): p. 307-321. [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, O., A. Thahir, and M. Krkovic, How Much Does an Infected Fracture Cost? Arch Bone Jt Surg, 2022. 10(2): p. 135-140. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, I.A., et al., Where Are We in 2022? A Summary of 11,000 Open Tibia Fractures Over 4 Decades. J Orthop Trauma, 2023. 37(8): p. e326-e334. [CrossRef]

- Polmear, M., et al., Deep Infections After Open and Closed Fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2025. 107(Suppl 1): p. 71-79. [CrossRef]

- Agel, J., et al., The OTA open fracture classification: a study of reliability and agreement. J Orthop Trauma, 2013. 27(7): p. 379-84; discussion 384-5.

- Gustilo, R.B., The Management of Open Fractures. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 1990. 72-A(2): p. 299-304.

- Gustilo, R.B. and J.T. Anderson, JSBS classics. Prevention of infection in the treatment of one thousand and twenty-five open fractures of long bones. Retrospective and prospective analyses. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2002. 84(4): p. 682. [CrossRef]

- Gustilo, R.B. and J.T. Anderson, Prevention of infection in the treatment of one thousand and twenty-five open fractures of long bones: retrospective and prospective analyses. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1976. 58(4): p. 453-8.

- Gustilo, R.B., et al., Analysis of 511 Open Fractures. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®, 1969. 66. [CrossRef]

- Hoff, W.S., et al., East Practice Management Guidelines Work Group: update to practice management guidelines for prophylactic antibiotic use in open fractures. J Trauma, 2011. 70(3): p. 751-4. [CrossRef]

- Hauser, C.J., et al., Surgical Infection Society guideline: prophylactic antibiotic use in open fractures: an evidence-based guideline. Surg Infect (Larchmt), 2006. 7(4): p. 379-405.

- Moher, D., et al., Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ, 2009. 339: p. b2535.

- Higgins, J.P.T. and Cochrane Collaboration, Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Second edition. ed. Cochrane book series. 2020, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. pages cm.

- Slim, K., et al., Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg, 2003. 73(9): p. 712-6. [CrossRef]

- GraphPad Prism version www.graphpad.com [9.4.1] 2022.

- Hozo, S.P., B. Djulbegovic, and I. Hozo, Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 2005. 5(1): p. 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-5-13.

- Wan, X., et al., Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 2014. 14(1): p. 135. [CrossRef]

- Collagboration, T.C., Review Manager Web 2020.

- Alpar, E.K., Cephradine and flucloxacillin in the prophylaxis of infection in patients with open fractures. Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics, 1988. 13(2): p. 117-20. [CrossRef]

- Bankhead-Kendall, B., et al., Antibiotics and open fractures of the lower extremity: less is more. EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF TRAUMA AND EMERGENCY SURGERY, 2019. 45(1): p. 125-129. [CrossRef]

- Depcinski, S.C., K.H. Nguyen, and P.T. Ender, Cefazolin and an aminoglycoside compared with cefazolin alone for the antimicrobial prophylaxis of type III open orthopedic fractures. International journal of critical illness and injury science, 2019. 9(3): p. 127-131. [CrossRef]

- Frantz, T.L., et al., Early complications of antibiotic prophylaxis with cefazolin protocols versus piperacillin-tazobactam for open fractures: a retrospective comparative study. CURRENT ORTHOPAEDIC PRACTICE, 2020. 31(6): p. 549-555. [CrossRef]

- Glass, G.E., et al., The microbiological basis for a revised antibiotic regimen in high-energy tibial fractures: Preventing deep infections by nosocomial organisms. JOURNAL OF PLASTIC RECONSTRUCTIVE AND AESTHETIC SURGERY, 2011. 64(3): p. 375-380. [CrossRef]

- Iobst, C.A., et al., A protocol for the management of pediatric type I open fractures. JOURNAL OF CHILDRENS ORTHOPAEDICS, 2014. 8(1): p. 71-76. [CrossRef]

- Janmohammadi, N. and M.R. Hasanjani Roshan, Comparison the efficacy of cefazolin plus gentamicin with cefazolin plus ciprofloxacin in management of Type-IIIA open fractures. Iranian Red Crescent medical journal, 2011. 13(4): p. 239-242.

- McMurtrie, T., et al., Extended Antibiotic Coverage in the Management of Type II Open Fractures. SURGICAL INFECTIONS, 2021. 22(7): p. 662-667. [CrossRef]

- O'Connell, C.R., et al., Evaluation of Piperacillin-Tazobactam for Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Traumatic Grade III Open Fractures. Surgical infections, 2022. 23(1): p. 41-46. [CrossRef]

- Patanwala, A.E., et al., Cefazolin Monotherapy Versus Cefazolin Plus Aminoglycosides for Antimicrobial Prophylaxis of Type III Open Fractures. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF THERAPEUTICS, 2021. 28(3): p. E284-E291. [CrossRef]

- Patzakis, M.J., et al., Prospective, randomized, double-blind study comparing single-agent antibiotic therapy, ciprofloxacin, to combination antibiotic therapy in open fracture wounds. Journal of orthopaedic trauma, 2000. 14(8): p. 529-533. [CrossRef]

- Redfern, J., et al., Surgical Site Infections in Patients With Type 3 Open Fractures: Comparing Antibiotic Prophylaxis With Cefazolin Plus Gentamicin Versus Piperacillin/Tazobactam. JOURNAL OF ORTHOPAEDIC TRAUMA, 2016. 30(8): p. 415-419. [CrossRef]

- Shawar, S.K., et al., Piperacillin/Tazobactam versus Tobramycin-Based Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Type III Open Fractures. Surgical infections, 2020. 21(1): p. 23-28. [CrossRef]

- Sorger, J.I., et al., Once daily, high dose versus divided, low dose gentamicin for open fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1999(366): p. 197-204. [CrossRef]

- Takahara, S., et al., Ampicillin/sulbactam versus cefazolin plus aminoglycosides for antimicrobial prophylaxis in management of Gustilo type IIIA open fractures: A retrospective cohort study. INJURY-INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE CARE OF THE INJURED, 2022. 53(4): p. 1517-1522. [CrossRef]

- Ukai, T., et al., Retrospective analysis of risk factors for deep infection in lower limb Gustilo-Anderson type III fractures. JOURNAL OF ORTHOPAEDICS AND TRAUMATOLOGY, 2020. 21(1). [CrossRef]

- Vasenius, J., et al., Clindamycin versus cloxacillin in the treatment of 240 open fractures. A randomized prospective study. Annales chirurgiae et gynaecologiae, 1998. 87(3): p. 224-228.

- OʼToole, R.V., et al., Local Antibiotic Therapy to Reduce Infection After Operative Treatment of Fractures at High Risk of Infection: A Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled Trial (VANCO Study). J Orthop Trauma, 2017. 31 Suppl 1: p. S18-s24. [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, A.D., D.R. Osmon, and R. Patel, Local antibiotic delivery systems: where are we and where are we going? Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2005(437): p. 111-4.

- Burbank, K.M., et al., Early application of topical antibiotic powder in open-fracture wounds: A strategy to prevent biofilm formation and infections. OTA International, 2020. 3(4): p. e091.

- Sajid, M.I., et al., Efficacy of Topical Antibiotic Powder Application in the Emergency Department on Reducing Deep Fracture-Related Infection in Type III Open Lower Extremity Fractures: A Multicenter Study. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Prebianchi, S., et al., Type of antibiotic but not the duration of prophylaxis correlates with rates of fracture-related infection. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Q. Zhang, and B. Su, Clinical characteristics and risk factors of severe infections in hospitalized adult patients with primary nephrotic syndrome. The Journal of international medical research, 2017. 45(6): p. 2139-2145. [CrossRef]

- Szymski, D., et al., Evaluation of Comorbidities as Risk Factors for Fracture-Related Infection and Periprosthetic Joint Infection in Germany. Journal of clinical medicine, 2022. 11(17): p. 5042. [CrossRef]

- Sudduth, J.D., et al., Open Fractures: Are We Still Treating the Same Types of Infections? SURGICAL INFECTIONS, 2020. 21(9): p. 766-772. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.M., et al., The effect of an immunosuppressive therapy and its withdrawal on bone healing around titanium implants. A histometric study in rabbits. J Periodontol, 2001. 72(10): p. 1391-7. [CrossRef]

- Hegde, V., et al., Effect of osteoporosis medications on fracture healing. Osteoporos Int, 2016. 27(3): p. 861-871. [CrossRef]

- Sagi, H.C., et al., Institutional and seasonal variations in the incidence and causative organisms for posttraumatic infection following open fractures. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 2017. 31(2): p. 78-84. [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.F., The effective period of preventive antibiotic action in experimental incisions and dermal lesions. Surgery, 1961. 50: p. 161-8.

- Patzakis, M.J. and J. Wilkins, Factors influencing infection rate in open fracture wounds. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1989(243): p. 36-40. [CrossRef]

- Messner, J., et al., Duration of Administration of Antibiotic Agents for Open Fractures: Meta-Analysis of the Existing Evidence. Surg Infect (Larchmt), 2017. 18(8): p. 854-867. [CrossRef]

- Stennett, C.A., et al., Effect of Extended Prophylactic Antibiotic Duration in the Treatment of Open Fracture Wounds Differs by Level of Contamination. JOURNAL OF ORTHOPAEDIC TRAUMA, 2020. 34(3): p. 113-120. [CrossRef]

- Rozell, J.C., K.P. Connolly, and S. Mehta, Timing of Operative Debridement in Open Fractures. Orthop Clin North Am, 2017. 48(1): p. 25-34. [CrossRef]

- Weber, D., et al., Time to initial operative treatment following open fracture does not impact development of deep infection: a prospective cohort study of 736 subjects. J Orthop Trauma, 2014. 28(11): p. 613-9.

- A Trial of Wound Irrigation in the Initial Management of Open Fracture Wounds. New England Journal of Medicine, 2015. 373(27): p. 2629-2641.

- Kumaar, A., A.H. Shanthappa, and P. Ethiraj, A Comparative Study on Efficacy of Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Versus Standard Wound Therapy for Patients With Compound Fractures in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Cureus, 2022. 14(4): p. e23727-e23727. [CrossRef]

- Kafisheh, H., et al., Characterization of antimicrobial prophylaxis and definitive repair in traumatic open fractures. Critical Care Medicine, 2022. 50(1 SUPPL): p. 771. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.D. and J.L. Kehoe, Bone Nonunion, in StatPearls. 2022: Treasure Island (FL).

| Author Year |

Patient No | Antibiotic | Dose/Duration | Antibiotic | Dose/Frequency | Mean Duration |

Mean Age | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regimen 1 | Regimen 2 | (days) | ||||||||

|

Alpar 1988 |

60 | Cephradine | 1g IM q6h, then 500 mg BID for ten days | Flucloxacillin | 250 mg IM q6h for ten days or Oral 250mg QID | 10 | 30.5 | 15 | ||

|

Bankhead-Kendall 2019 |

126 | Cefazolin | N/A | Cefazolin + Aminoglycoside | N/A | 2.9 | 31.5 | 28 | ||

|

Depcinski 2019 |

68 | Cefazolin | N/A | Cefazolin + Aminoglycoside | 1.5 mg/kg q8h or 5 mg/kg q24h | 1 | 31.5 | 54 | ||

|

Frantz 2020 |

202 | Cefazolin | N/A | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | N/A | Cefazolin + Aminoglycoside | N/A | 3 | 43.5 | 56 |

|

Glass 2011 |

52 | Cephalosporin ± Gentamicin | N/A | Flucloxacillin ± Benzyl Penicillin | N/A | N/A | 40 | 11 | ||

|

Iobst 2014 |

45 | Cefazolin | 21.7 (range 11.9-45) mg/kg | Clindamycin | 12.1 (range 9.8-15.2) mg/kg | 1 | 10 | 9 | ||

|

Janmohammadi 2011 |

301 | Cefazolin + Gentamicin | 5g IV q8h + Gentamicin divided into 3 doses | Cefazolin + Ciprofloxacin | 1g IV q8h + 500 mg TID | 3 | 37 | 86 | ||

|

McMurtrie 2021 |

144 | Cefazolin or Clindamycin if allergy to cephalosporin | Upon arrival and a minimum of 24 h after I&D | Piperacillin/Tazobactam |

Upon arrival and a minimum of 24 h after I&D |

1 | 41 | 58 | ||

|

O’Connell 2022 |

120 | Cefazolin + Gentamicin | N/A | Piperacillin/Tazobactam | N/A | 5 | 46.3 | 37 | ||

|

Patanwala 2021 |

134 | Cefazolin | 2g IV q8h | Cefazolin + Aminoglycoside | 6 mg/kg QD or 2.5 mg/kg BID | 3 | 39 | 29 | ||

|

Patzakis 2000 |

163 | Ciprofloxacin | N/A | Cefamandole/Gentamicin | N/A | N/A | 30 | 29 | ||

|

Redfern 2016 |

72 | Cefazolin + Gentamicin | 1-2g every 8-12h + 1-2.5 mg/kg q8h or 7 mg/kg QD | Piperacillin/Tazobactam |

4.5g every 6-12h | 3.5 | 44.5 | 38 | ||

|

Shawar 2020 |

85 | Piperacillin/Tazobactam | 4.5 g q8h (1st dose over 30 minutes and later doses over 4h) | Tobramycin plus Cefazolin | 7 mg/kg plus 2g q8h |

1 | 41.1 | 26 | ||

|

Sorger 1999 |

71 | Twice Daily Dose of Cefazolin + Gentamicin | 5 mg/kg of body weight divided into two daily doses | Once Daily Dose of Cefazolin + Gentamicin | 6 mg/kg of body weight given once daily |

1 | 36 | 25 | ||

|

Takahara 2022 |

90 | Cefazolin plus Aminoglycoside (Amikacin or gentamicin) | 1-2 g q8h plus daily based on weight | Ampicillin/Sulbactam | 3g every 8 h | 1 | 50.65 | 30 | ||

|

Ukai 2020 |

110 | Cefazolin | 1g or 2g BID | Cefazolin + Gentamicin | Dosed based on therapeutic drug monitoring | 12.65 | 44.5 | 29 | ||

|

Vasenius 1998 |

227 | Clindamycin | 300-600 mg by patient weight q6h for 72 h | Cloxacillin | 2g IV every 6 h for 72 h | 3 | 38 | 80 | ||

| Author Year |

Country | Patient No | Mean Age | Female | Antibiotic | Antibiotic | Open Fracture Types | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regimen 1 | Regimen 2 | Type I | Type II | Type IIIA | Type IIIB | Type IIIC | ||||||||||

|

Alpar 1988 |

United Kingdom | 60 | 30.5 | 15 | Cephradine | Flucloxacillin | 12 | 20 | 28 | |||||||

|

Bankhead-Kendall 2019 |

Germany | 126 | 31.5 | 28 | Cefazolin | Cefazolin + Aminoglycoside | N/A | N/A | 126 | |||||||

|

Depcinski 2019 |

USA | 68 | 31.5 | 54 | Cefazolin | Cefazolin + Aminoglycoside | N/A | N/A | 68 | |||||||

|

Frantz 2020 |

USA | 202 | 43.5 | 56 | Cefazolin | N/A | Cefazolin + Aminoglycoside | N/A | 86 | 116 | ||||||

|

Glass 2011 |

USA | 52 | 40 | 11 | Cephalosporin ± Gentamicin | Flucloxacillin ± Benzyl Penicillin | N/A | N/A | N/A | 52 | N/A | |||||

|

Iobst 2014 |

USA | 45 | 10 | 9 | Cefazolin | Clindamycin | 45 | N/A | ||||||||

|

Janmohammadi 2011 |

Iran | 301 | 37 | 86 | Cefazolin + Gentamicin | Cefazolin + Ciprofloxacin | N/A | N/A | 301 | N/A | N/A | |||||

|

McMurtrie 2021 |

USA | 144 | 41 | 58 | Cefazolin or Clindamycin if allergy to cephalosporin | Piperacillin/tazobactam |

N/A | 144 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||||

|

O’Connell 2022 |

USA | 120 | 46.3 | 37 | Cefazolin + Gentamicin | Piperacillin/tazobactam | N/A | N/A | 120 | |||||||

|

Patanwala 2021 |

USA | 134 | 39 | 29 | Cefazolin | Cefazolin + Aminoglycoside | N/A | N/A | 134 | |||||||

|

Patzakis 2000 |

USA | 163 | 30 | 29 | Ciprofloxacin | Cefamandole/Gentamicin | 65 | 54 | 34 | 16 | 2 | |||||

|

Redfern 2016 |

USA | 72 | 44.5 | 38 | Cefazolin + Gentamicin | Piperacillin/tazobactam |

N/A | N/A | 72 | |||||||

|

Shawar 2020 |

USA | 85 | 41.1 | 26 | Piperacillin/tazobactam | Tobramycin plus Cefazolin | N/A | N/A | 85 | |||||||

|

Sorger 1999 |

USA | 71 | 36 | 25 | Twice Daily Dose of Cefazolin + Gentamicin | Once Daily Dose of Cefazolin + Gentamicin | N/A | 77 | 10 | 10 | 3 | |||||

|

Takahara 2022 |

Japan | 90 | 50.65 | 30 | Cefazolin plus Aminoglycoside (Amikacin or gentamicin) | Ampicillin/Sulbactam (ABPC/SBT) | N/A | N/A | 95 | N/A | N/A | |||||

|

Ukai 2020 |

Japan | 110 | 44.5 | 29 | Cefazolin | Cefazolin + Gentamicin | N/A | N/A | 77 | 37 | N/A | |||||

|

Vasenius 1998 |

Finland | 227 | 38 | 80 | Clindamycin | Cloxacillin | 60 | 109 | 33 | 15 | 10 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).